Several tumor markers and biomarkers, both tissue-

and serum-based, are currently used in the management of patients

with breast cancer (1-4),

among which, carbohydrate antigen 15-3 (CA 15-3) is considered a

specific tumor marker for breast cancer. At present, the main

utility of CA 15-3 is monitoring therapy in patients with advanced

breast cancer, especially in women with non-evaluable disease. Most

expert panels advise against the routine use of CA 15-3 in the

surveillance of asymptomatic patients who have undergone surgery

for breast cancer (5).

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multi-system

autoimmune disorder characterized by autoantibody production,

endothelial damage with obliterative microvascular disease,

inflammation, and fibrosis affecting the skin and internal organs

(6,7). Cardiopulmonary involvement is a

common manifestation in SSc, which presents as either interstitial

lung disease (ILD) or pulmonary arterial hypertension (8), and is currently the leading cause of

disease-related morbidity and mortality in patients with

scleroderma (9). The most studied

and characterized biomarker for ILD is Krebs von den Lungen 6

(KL-6) (10,11). CA 15-3 is the shed or soluble form

of MUC-1 protein. MUC1 is strongly expressed by atypical and/or

regenerating type II pneumocytes in tissue sections obtained from

patients with ILDs (12-14).

Although CA 15-3 has been investigated as a biomarker in SSc-ILD,

its role remains unclear (15-17).

Herein, we report a case of coexisting SSc and recurrent breast

cancer who showed improvement in high CA 15-3 levels with

amelioration of ILD without any systemic cancer treatment.

A 60-year-old woman underwent mastectomy with

axillary lymph node dissection at JA Hiroshima General Hospital

(Hatsukaichi, Japan) in October 2014 after preoperative

chemotherapy (four cycles of docetaxel and trastuzumab, followed by

four cycles of cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil) for

estrogen receptor-negative, HER2-positive right breast invasive

ductal cancer, T2N1M0 stage IIB (18). Postoperative radiation therapy with

50 Gy in 25 fractions to the supraclavicular lymph nodes and chest

wall was performed, followed by 14 cycles of 3-weekly

trastuzumab.

At 63 years old, contrast-enhanced computed

tomography (CT) performed as postoperative follow-up indicated

brain metastasis in the right occipital lobe without liver, lung,

or bone metastasis. She underwent γ-knife radiosurgery (20 Gy)

followed by the administration of perutuzumab, trastuzumab, and

weekly paclitaxel. After four cycles of perutuzumab, trastuzumab,

and weekly paclitaxel, she experienced shortness of breath with

minimal exertion, so the fifth course was canceled. CT revealed

ground-glass opacities and linear shadows in the peripheral lower

lobes of both lungs (Fig. 1).

Although the development of lung involvement associated with breast

cancer such as carcinomatous lymphangitis was initially suspected,

because of the increase in CA 15-3, we investigated other possible

causes of ILD (Fig. 2). From only

CT image, the possibility of interstitial lung disease due to

trastuzumab or pertuzumab cannot be ruled out (19). Bilateral sclerodactyly and facial

skin thickness were found on clinical examination without a history

of Raynaud's phenomenon and the finding of nail fold bleeding. A

test for anti-nuclear antibodies with a nucleolar pattern was

positive, at a titer of 1:320. Anti-double stranded DNA antibody,

specific antibodies against centromere, SSA/SSB, Scl-70, RNP, and

RNA polymerase III were negative. Pulmonary function tests showed a

severely reduced %VC of 50.8%, indicating restrictive ventilatory

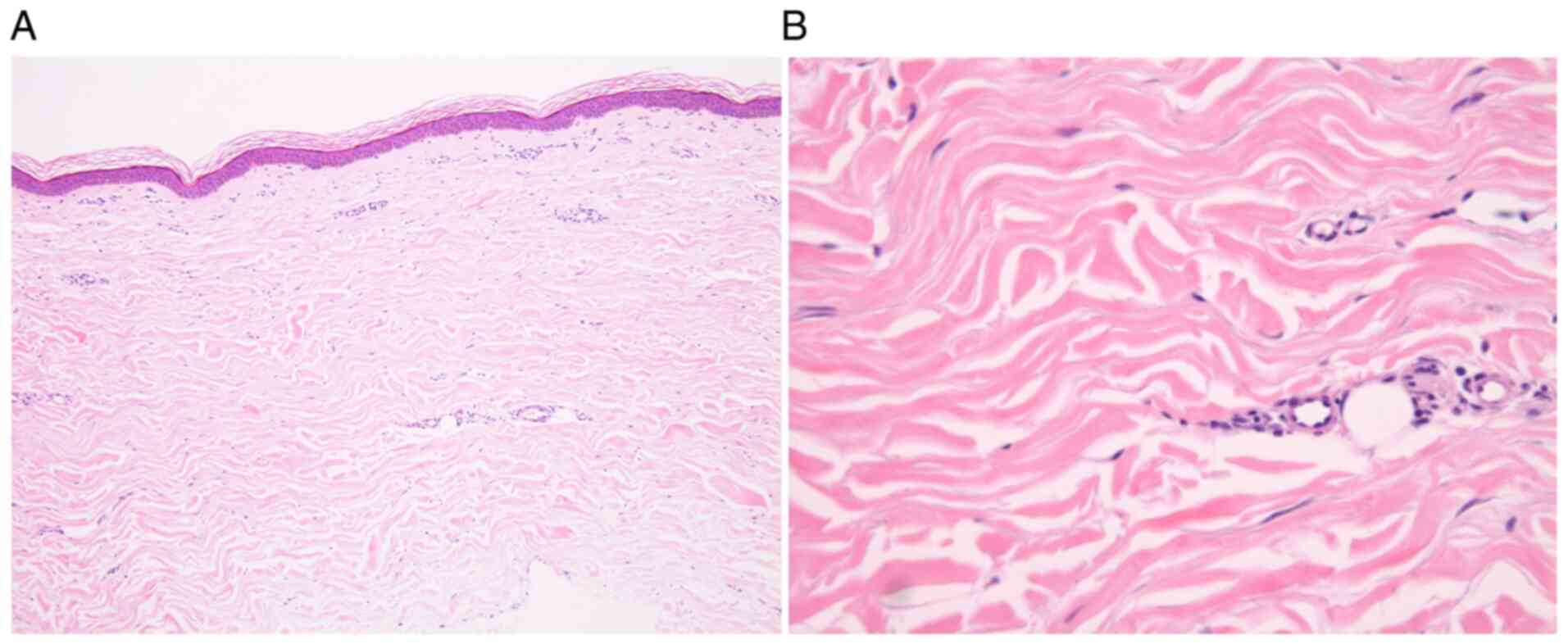

impairment. Skin biopsies taken from the left index finger base and

extension side of the left elbow demonstrated increased thickness

of the dermis composed of broad and sclerotic collagen bundles

extending to the underlying subcutis without inflammatory cell

infiltration in hematoxylin and eosin stained-samples. These

findings were consistent with the late stage of scleroderma

(Fig. 3). From these findings, the

diagnosis of SSc-ILD was made according to the diagnostic criteria

for SSc proposed by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of

Japan. The treatment for recurrent breast cancer was discontinued,

and combination prednisone (PSL) (15 mg/day) and intravenous

cyclophosphamide (IVCY) (500 mg/4 weeks) therapy was administered

for induction treatment of SSc-ILD. PSL was tapered and

discontinued at 1 year and IVCY was given five times in total. At 6

months after the start of treatment, her symptoms, including cough

and dyspnea, had improved. CA 15-3 and KL-6 levels decreased

simultaneously, reflecting the therapeutic effect (Fig. 2), and CT showed improvement in the

ground-glass opacities in the peripheral lower lobes of both lungs

as compared with those before treatment (Fig. 4). This patient is receiving

treatment for SSc-ILD. The patient's SSc-ILD has not worsening and

her breast cancer has not recurred despite not receiving treatment

for four years.

SSc is a devastating disease of unknown etiology

that is characterized by systemic, immunological, vascular, and

fibrotic abnormalities and a heterogeneous clinical course.

Fibrosis, the hallmark of the disease, can affect the skin and

internal organs, including lung (20). As is well known, pulmonary

involvement is one of the most important features of SSc and often

the leading cause of exitus. SSc-ILD is one of the most severe

complications and is the main cause of SSc-related deaths (9,21);

however, review of contemporary literature suggests improved

survival among patients with SSc-ILD due to more aggressive

monitoring and treatment (22,23).

In clinical trials of SSc-ILD, change in forced vital capacity

(FVC) is commonly used as a primary outcome measure, as low FVC

predicts morbidity and mortality (24). Two landmark clinical trials, SLS-I

(25) and SLS-II (26), established cyclophosphamide and

mycophenolate mofetil as disease modifying therapies for SSc

patients with active ILD.

Taxanes, as well as other antineoplastic agents,

have many toxic effects. Therefore, whether the etiology of the

present case is drug-induced remains unclear. Taxane-induced

scleroderma-like skin changes were first reported in 1995, and

clinical characteristics include preceding edema, absence of

Raynaud's phenomenon, and negative scleroderma-specific

autoantibodies (46-49).

The clinical course is refractory to treatment and commonly

progressive even after discontinuation of the trigger drugs

(50). However, unlike the present

study, previous reports showed mainly skin disorders without ILD.

In addition, the positivity of anti-nuclear antibodies with a

nucleolar pattern in this case, which suggested the existence of

SSc-specific antibodies against RNA polymerase III, Th/To, U3-RNP,

and PM-Scl, helped us determine the diagnosis of SSc regardless of

taxane exposure (51).

CA 15-3 is the shed or soluble form of MUC-1

protein. MUC1 is a transmembrane mucin with marked overexpression

in human breast cancers as compared with that in normal ductal

breast epithelial cells (52). On

the other hand, MUC1 is strongly expressed by atypical and/or

regenerating type II pneumocytes in tissue sections obtained from

patients with ILDs (12-14).

Serum levels of KL-6, an N-terminal subunit of MUC-1 protein,

increases in the acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary

fibrosis (IPF). Serum levels of KL-6 correlate with IPF severity

and prognosis (53). As both KL-6

and CA 15-3 exist in different positions of MUC1(54), CA 15-3 may retain significant

potential as an alternative biomarker for KL-6 in fibrotic lung

diseases (16-18,55).

In primary breast cancer, various studies have demonstrated that

elevated serum CA15-3 values at diagnosis are associated with

higher breast cancer stage, tumor size, positive axillary lymph

nodes, and worse overall survival and disease-free survival

(56-60).

In metastatic breast cancer, CA15-3 was measured serially in a

number of studies assessing their applications in early detection

of disease progression and monitoring therapy response (61-65).

On the other hand, CA15-3 was previously shown to be elevated in

serum of SSc-ILD patients and was associated with severe ILD

measured by fibrosis on HRCT, decreased FVC and DLCO and the

presence of dyspnoea (16,66). In a study performed by Celeste

et al on 221 SSc patients, among which 168 with ILD, CA15-3

serum levels were found to correlate with the extent of fibrosis

detected on HRCT as well as to be predictive for progression-free

survival, with progression being defined by a decline in either FVC

or DLCO (17). The present study

suggested that oncologists treating the patients with breast cancer

should know CA15-3 is also associated with the condition of ILD.

The concentration of some tumor-associated antigens (TAA) such as

CA19-9 and CA125 were reported to be elevated in the sera of

patients with SSc or systemic lupus erythematosus in comparison to

healthy subjects (67). Because of

public insurance coverage, the number of TAA for patients with

breast cancer that could be measured at one time is limited. CEA

could be measured for patients with breast cancer at the same time.

In this patient, CEA did not show outlier or abnormal changes.

Meanwhile, KL-6 has been reported as a tumor marker

in not only lung cancer, but also gastrointestinal, hepatic,

pancreatic, and breast cancers (68,69).

Kohno, the developer of KL-6 monoclonal antibody, noted that the

serum levels of KL-6 mucin were elevated in patients with

pulmonary, breast, and pancreatic adenocarcinomas (12). Elevation of KL-6 mucin in serum is

significantly associated with the behavior of breast cancer

(70) or lung cancer (68). Immunohistochemical analyses have

clarified KL-6 mucin's clinicopathological significance in

digestive organ cancer tissues. As the expression profile and

clinicopathological significance of KL-6 mucin differ among each

organ or disease, the biological role of KL-6 mucin might have a

different importance in each location and state (68). Thus, the nature of KL-6 mucin

remains unclear, and further investigations of KL-6 mucin in cancer

are expected in the future.

In conclusion, serum levels of CA 15-3 correlated

with the condition of SSc-ILD in a patient with recurrent breast

cancer. This case suggests the importance of considering a

differential diagnosis including ILD concurrently while screening

for the progression of recurrent breast cancer when encountering

patients with breast cancer and elevated levels of CA 15-3.

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Takamoto and

Mrs. Nishimoto (Nursing Department, Hiroshima General Hospital) for

their special help with breast cancer nursing care.

Funding: No funding was received.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

MO wrote the draft and critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. MO performed

surgical and post-operative treatment. MO, YK, TS and KK

contributed to the conception of the work, and interpreted and

revised the results of the CT included in this report. YY treated

the patient for SSc-ILD. YD diagnosed the disease pathologically.

YY, SM, AT, AO, IN, MS, KI, MW, and YD collected and analyzed both

the clinical laboratory and histopathological data. MO and YY

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying

images.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Sturgeon CM, Duffy MJ, Stenman UH, Lilja

H, Brünner N, Chan DW, Babaian R, Bast RC Jr, Dowell B, Esteva FJ,

et al: National academy of clinical biochemistry laboratory

medicine practice guidelines for use of tumor markers in

testicular, prostate, colorectal, breast, and ovarian cancers. Clin

Chem. 54:e11–e79. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Duffy MJ: Biochemical markers in breast

cancer: Which ones are clinically useful? Clin Biochem. 34:347–352.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Duffy MJ: Predictive markers in breast and

other cancers: A review. Clin Chem. 51:494–503. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Duffy MJ, Walsh S, McDermott EW and Crown

J: Biomarkers in breast cancer: Where Are we and where are we

going? Adv Clin Chem. 71:1–23. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Duffy MJ, Evoy D and McDermott EW: CA

15-3: Uses and limitation as a biomarker for breast cancer. Clin

Chim Acta. 411:1869–1874. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Silver RM: Clinical aspects of systemic

sclerosis (scleroderma). Ann Rheum Dis. 50 (Suppl 4):S854–S861.

1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Varga J and Abraham D: Systemic sclerosis:

A prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest.

117:557–567. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wells AU, Steen V and Valentini G:

Pulmonary complications: One of the most challenging complications

of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 48 (Suppl

3):iii40–iii44. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Steen VD and Medsger TA: Changes in causes

of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis.

66:940–944. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Prasse A and Müller-Quernheim J:

Non-invasive biomarkers in pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology.

14:788–795. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ishikawa N, Hattori N, Yokoyama A and

Kohno N: Utility of KL-6/MUC1 in the clinical management of

interstitial lung diseases. Respir Investig. 50:3–13.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kohno N, Akiyama M, Kyoizumi S, Hakoda M,

Kobuke K and Yamakido M: Detection of soluble tumor-associated

antigens in sera and effusions using novel monoclonal antibodies,

KL-3 and KL-6, against lung adenocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol.

18:203–216. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tanaka S, Hattori N, Ishikawa N, Shoda H,

Takano A, Nishino R, Okada M, Arihiro K, Inai K, Hamada H, et al:

Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) is a prognostic biomarker in patients

with surgically resected nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer.

130:377–387. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yamasaki H, Ikeda S, Okajima M, Miura Y,

Asahara T, Kohno N and Shimamoto F: Expression and localization of

MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and small intestinal mucin antigen in pancreatic

tumors. Int J Oncol. 24:107–113. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ricci A, Mariotta S, Bronzetti E, Bruno P,

Vismara L, De Dominicis C, Laganà B, Paone G, Mura M, Rogliani P,

et al: Serum CA 15-3 is increased in pulmonary fibrosis.

Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 26:54–63. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Valerio Marzano A, Morabito A, Berti E and

Caputo R: Elevated circulating CA 15.3 levels in a subset of

systemic sclerosis with severe lung involvement. Arch Dermatol.

134(645)1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Celeste S, Santaniello A, Caronni M,

Franchi J, Severino A, Scorza R and Beretta L: Carbohydrate antigen

15.3 as a serum biomarker of interstitial lung disease in systemic

sclerosis patients. Eur J Intern Med. 24:671–676. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Greene FL: Breast tumours. In: TNM

classification of malignant tumours. Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK and

Wittekind C (eds). 7th edition. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp181-193,

2009.

|

|

19

|

Hackshaw MD, Danysh HE, Singh J, Ritchey

ME, Ladner A, Taitt C, Camidge DR, Iwata H and Powell CA: Incidence

of pneumonitis/interstitial lung disease induced by HER2-targeting

therapy for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer

Res Treat. 183:23–39. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Varga J: Systemic sclerosis: An update.

Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 66:198–202. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, Airò P,

Cozzi F, Carreira PE, Bancel DF, Allanore Y, Müller-Ladner U,

Distler O, et al: Causes and risk factors for death in systemic

sclerosis: A study from the EULAR scleroderma trials and research

(EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis. 69:1809–1815. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Volkmann ER and Fischer A: Update on

morbidity and mortality in systemic sclerosis-related interstitial

lung disease. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 6:11–20. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Rubio-Rivas M, Royo C, Simeón CP, Corbella

X and Fonollosa V: Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum.

44:208–219. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Steen VD, Conte C, Owens GR and Medsger TA

Jr: Severe restrictive lung disease in systemic sclerosis.

Arthritis Rheum. 37:1283–1289. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ,

Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, Arriola E, Silver R, Strange C,

Bolster M, et al: Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma

lung disease. N Engl J Med. 354:2655–2666. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst

DE, Khanna D, Kleerup EC, Goldin J, Arriola E, Volkmann ER, Kafaja

S, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in

scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): A

randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet

Respir Med. 4:708–719. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Colaci M, Giuggioli D, Vacchi C, Lumetti

F, Iachetta F, Marcheselli L, Federico M and Ferri C: Breast cancer

in systemic sclerosis: Results of a cross-linkage of an Italian

rheumatologic center and a population-based cancer registry and

review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 13:132–137.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Abu-Shakra M, Guillemin F and Lee P:

Cancer in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 36:460–464.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Szekanecz É, Szamosi S, Horváth Á, Németh

Á, Juhász B, Szántó J, Szücs G and Szekanecz Z: Malignancies

associated with systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 11:852–855.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Scope A, Sadetzki S, Sidi Y, Barzilai A,

Trau H, Kaufman B, Catane R and Ehrenfeld M: Breast cancer and

scleroderma. Skinmed. 5:18–24. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hill CL, Nguyen AM, Roder D and

Roberts-Thomson P: Risk of cancer in patients with scleroderma: A

population based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 62:728–731.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Maria ATJ, Partouche L, Goulabchand R,

Rivière S, Rozier P, Bourgier C, Le Quellec A, Morel J, Noël D and

Guilpain P: Intriguing relationships between cancer and systemic

sclerosis: Role of the immune system and other contributors. Front

Immunol. 9(3112)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Straub RH, Zeuner M, Lock G, Schölmerich J

and Lang B: High prolactin and low dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate

serum levels in patients with severe systemic sclerosis. Br J

Rheumatol. 36:426–432. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wang M, Wu X, Chai F, Zhang Y and Jiang J:

Plasma prolactin and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep.

6(25998)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Li CI, Daling JR, Tang MT, Haugen KL,

Porter PL and Malone KE: Use of antihypertensive medications and

breast cancer risk among women aged 55 to 74 years. JAMA Intern

Med. 173:1629–1637. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gómez-Acebo I, Dierssen-Sotos T,

Palazuelos C, Pérez-Gómez B, Lope V, Tusquets I, Alonso MH, Moreno

V, Amiano P, Molina de la Torre AJ, et al: The use of

antihypertensive medication and the risk of breast cancer in a

case-control study in a spanish population: The MCC-spain study.

PLoS One. 11(e0159672)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bernal-Bello D, García de Tena J,

Simeón-Aznar C and Fonollosa-Pla V: Systemic sclerosis, breast

cancer and calcium channel blockers: A new player on the scene?

Autoimmun Rev. 13:880–881. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Brasky TM, Krok-Schoen JL, Liu J,

Chlebowski RT, Freudenheim JL, Lavasani S, Margolis KL, Qi L,

Reding KW, Shields PG, et al: Use of calcium channel blockers and

breast cancer risk in the women's health initiative. Cancer

Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 26:1345–1348. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Baltus JA, Boersma JW, Hartman AP and

Vandenbroucke JP: The occurrence of malignancies in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis treated with cyclophosphamide: A controlled

retrospective follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 42:368–373. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Gulamhusein A and Pope JE: Squamous cell

carcinomas in 2 patients with diffuse scleroderma treated with

mycophenolate mofetil. J Rheumatol. 36:460–462. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Okada K, Endo Y, Miyachi Y, Koike Y,

Kuwatsuka Y and Utani A: Glycosaminoglycan and versican deposits in

taxane-induced sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 173:1054–1058.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Hung CH, Chan SH, Chu PM and Tsai KL:

Docetaxel facilitates endothelial dysfunction through oxidative

stress via modulation of protein kinase C beta: The protective

effects of sotrastaurin. Toxicol Sci. 145:59–67. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Abu-Shakra M and Lee P: Exaggerated

fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma)

following radiation therapy. J Rheumatol. 20:1601–1603.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Darras-Joly C, Wechsler B, Blétry O and

Piette JC: De novo systemic sclerosis after radiotherapy: A report

of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 26:2265–2267. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Shah DJ, Hirpara R, Poelman CL, Woods A,

Hummers LK, Wigley FM, Wright JL, Parekh A, Steen VD, Domsic RT and

Shah AA: Impact of radiation therapy on scleroderma and cancer

outcomes in scleroderma patients with breast cancer. Arthritis Care

Res (Hoboken). 70:1517–1524. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Verhulst L, Noë E, Morren MA, Verslype C,

Van Cutsem E, Van den Oord JJ and De Haes P: Scleroderma-like

cutaneous lesions during treatment with paclitaxel and gemcitabine

in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Review of literature.

Int J Dermatol. 57:1075–1079. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Itoh M, Yanaba K, Kobayashi T and Nakagawa

H: Taxane-induced scleroderma. Br J Dermatol. 156:363–367.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Kłudkowska J,

Olszewska B, Seredyńska J, Biernat W, Błażewicz I,

Rustowska-Rogowska A and Nowicki RJ: The first case of drug-induced

pseudoscleroderma and eczema craquelé related to nab-paclitaxel

pancreatic adenocarcinoma treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol.

35:106–108. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Shibao K, Okiyama N, Maruyama H, Jun-Ichi

F and Fujimoto M: Scleroderma-like skin changes occurring after the

use of paclitaxel without any chemical solvents: A first case

report. Eur J Dermatol. 26:317–318. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Battafarano DF, Zimmerman GC, Older SA,

Keeling JH and Burris HA: Docetaxel (Taxotere) associated

scleroderma-like changes of the lower extremities. A report of

three cases. Cancer. 76:110–115. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Hamaguchi Y: Autoantibody profiles in

systemic sclerosis: Predictive value for clinical evaluation and

prognosis. J Dermatol. 37:42–53. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Kufe D, Inghirami G, Abe M, Hayes D,

Justi-Wheeler H and Schlom J: Differential reactivity of a novel

monoclonal antibody (DF3) with human malignant versus benign breast

tumors. Hybridoma. 3:223–232. 1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wakamatsu K, Nagata N, Kumazoe H, Oda K,

Ishimoto H, Yoshimi M, Takata S, Hamada M, Koreeda Y, Takakura K,

et al: Prognostic value of serial serum KL-6 measurements in

patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Investig.

55:16–23. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Baldus SE, Engelmann K and Hanisch FG:

MUC1 and the MUCs: A family of human mucins with impact in cancer

biology. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 41:189–231. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Kruit A, Gerritsen WB, Pot N, Grutters JC,

van den Bosch JM and Ruven HJ: CA 15-3 as an alternative marker for

KL-6 in fibrotic lung diseases. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis.

27:138–146. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Uehara M, Kinoshita T, Hojo T,

Akashi-Tanaka S, Iwamoto E and Fukutomi T: Long-term prognostic

study of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen

15-3 (CA 15-3) in breast cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 13:447–451.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Shering SG, Sherry F, McDermott EW,

O'Higgins NJ and Duffy MJ: Preoperative CA 15-3 concentrations

predict outcome of patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer.

83:2521–2527. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Shao Y, Sun X, He Y, Liu C and Liu H:

Elevated levels of serum tumor markers CEA and CA15-3 are

prognostic parameters for different molecular subtypes of breast

cancer. PLoS One. 10(e0133830)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Fu Y and Li H: Assessing clinical

significance of serum CA15-3 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

levels in breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit.

22:3154–3162. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Di Gioia D, Dresse M, Mayr D, Nagel D,

Heinemann V and Stieber P: Serum HER2 in combination with CA 15-3

as a parameter for prognosis in patients with early breast cancer.

Clin Chim Acta. 440:16–22. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Wojtacki J, Kruszewski WJ, Sliwińska M,

Kruszewska E, Hajdukiewicz W, Sliwiński W, Rolka-Stempniewicz G,

Góralczyk M and Leśniewski-Kmak K: Elevation of serum Ca 15-3

antigen: An early indicator of distant metastasis from breast

cancer. Retrospective analysis of 733 cases. Przegl Lek.

58:498–503. 2001.PubMed/NCBI(In Polish).

|

|

62

|

Tampellini M, Berruti A, Bitossi R,

Gorzegno G, Alabiso I, Bottini A, Farris A, Donadio M, Sarobba MG,

Manzin E, et al: Prognostic significance of changes in CA 15-3

serum levels during chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer

patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 98:241–248. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Chourin S, Veyret C, Chevrier A, Loeb A,

Gray C and Basuyau J: Routine use of serial plasmatic CA 15-3

determinations during the follow-up of patients treated for breast

cancer. Evaluation as factor of early diagnosis of recurrence. Ann

Biol Clin (Paris). 66:385–392. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In French).

|

|

64

|

Yang Y, Zhang H, Zhang M, Meng Q, Cai L

and Zhang Q: Elevation of serum CEA and CA15-3 levels during

antitumor therapy predicts poor therapeutic response in advanced

breast cancer patients. Oncol Lett. 14:7549–7556. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Kim HS, Park YH, Park MJ, Chang MH, Jun

HJ, Kim KH, Ahn JS, Kang WK, Park K and Im YH: Clinical

significance of a serum CA15-3 surge and the usefulness of CA15-3

kinetics in monitoring chemotherapy response in patients with

metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 118:89–97.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Wong RC, Brown S, Clarke BE, Klingberg S

and Zimmerman PV: Transient elevation of the tumor markers CA 15-3

and CASA as markers of interstitial lung disease rather than

underlying malignancy in dermatomyositis sine myositis. J Clin

Rheumatol. 8:204–207. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Inagaki Y, Xu H, Nakata M, Seyama Y,

Hasegawa K, Sugawara Y, Tang W and Kokudo N: Clinicopathology of

sialomucin: MUC1, particularly KL-6 mucin, in gastrointestinal,

hepatic and pancreatic cancers. Biosci Trends. 3:220–232.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Szekanecz E, Szucs G, Szekanecz Z, Tarr T,

Antal-Szalmás P, Szamosi S, Szántó J and Kiss E: Tumor-associated

antigens in systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus:

Associations with organ manifestations, immunolaboratory markers

and disease activity indices. J Autoimmun. 31:372–376.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Ogawa Y, Ishikawa T, Ikeda K, Nakata B,

Sawada T, Ogisawa K, Kato Y and Hirakawa K: Evaluation of serum

KL-6, a mucin-like glycoprotein, as a tumor marker for breast

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 6:4069–4072. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Kohno N: Serum marker KL-6/MUC1 for the

diagnosis and management of interstitial pneumonitis. J Med Invest.

46:151–158. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|