Introduction

Endometrial cancer accounts for approximately 4% of

all cancers in women and occurs predominantly after menopause. Some

of the highest incidence rates worldwide are found in the US and

European populations (1). Clinical

signs and symptoms associated with endometrial cancer include

postmenopausal bleeding and perimenopausal meno-metrorrhagia

(2). Women presenting with these

conditions undergo histological evaluation of the endometrium.

Typically, endometrial tissue sampling is combined with

hysteroscopy, i.e., the optical visualization of the endometrial

cavity via an endoscope (2–5).

Hysteroscopy is a highly accurate method and is useful in

diagnosing, rather than excluding endometrial cancer in women with

abnormal uterine bleeding (6).

This technique, however, flushes fluid and endometrial cells into

the abdomen via the fallopian tubes, thus potentially spreading

malignant cells. For example, in a prospective randomized study,

Nagele et al examined 30 women undergoing hysteroscopy and

concomitant laparoscopy for infertility. Endometrial cells were

present in the peritoneal fluid in 6% of patients before

hysteroscopy and in 25% after hysteroscopy (7). A number of studies have associated

hysteroscopy with an increased risk of positive peritoneal cytology

in women with endometrial cancer (8,9),

while certain studies have raised the possibility of an adverse

impact of hysteroscopy on prognosis in women with endometrial

cancer (10–13).

Despite these concerns, however, hysteroscopy is

considered a safe and acceptable procedure and is used extensively

for the evaluation of women with postmenopausal bleeding or

perimenopausal meno-metrorrhagia (14,15).

Whether or not the duration of hysteroscopy is a matter of concern

in women with suspected endometrial cancer is yet unknown. If

prolonged hysteroscopy increased the risk of positive peritoneal

cytology and disease recurrence, this would have clinical

implications regarding time restriction or avoidance of

hysteroscopy in women with suspected endometrial cancer.

To investigate this issue, we performed a

retrospective multi-centre study in a large series of women with

endometrial cancer who underwent pre-operative hysteroscopy. The

aim of our study was to investigate whether the duration of

hysteroscopy is associated with positive peritoneal cytology at

surgery and adverse prognosis in patients with endometrial

cancer.

Materials and methods

Five hundred and fifty-two patients with endometrial

cancer, treated at the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology of

the Medical University of Vienna, Austria (n=220), the Medical

University of Innsbruck, Austria (n=204), the Landeskrankenhaus

Klagenfurt, Austria (n=87), the Landeskrankenhaus Wiener Neustadt,

Austria (n=39) and the Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Royal

Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia (n=2), between February 1996

and July 2009, were included in the present study. Clinical and

laboratory data were extracted retrospectively from patient

files.

Diagnosis of endometrial cancer was established by

diagnostic hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage. Hysteroscopy

was performed with saline as the distension medium. Duration of

hysteroscopy was defined as the time between the start and the end

of the surgical procedure. The duration of hysteroscopy was noted

by the nursing staff on a surgical procedure documentation sheet.

Patients were surgically staged according to the International

Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)/American Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification system. Hysterectomy,

bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, cytological examination of

peritoneal fluid and biopsy of any suspicious intraperitoneal or

retroperitoneal lesions were performed. Pelvic and paraaortic

lymphadenectomy were performed, except for tumour stages FIGO Ia

and Ib (using the 1989 FIGO classification for endometrial cancer)

with histological grades 1 and 2 and endometrioid histology. In

patients with intermediate- or high-risk disease, adjuvant

radiotherapy was provided according to standardized treatment

protocols (16). A regimen of

adjuvant chemotherapy using carboplatin/ paclitaxel was used in

selected patients with advanced disease.

Three months after completion of primary therapy,

the first follow-up visit was scheduled. Patients had follow-up

visits at 3-month intervals for the following 2 years, including

inspection and vaginal-rectal palpation. In the third and fourth

year, visits were scheduled bi-annually and once a year from the

fifth year on. When patients did not present for the scheduled

follow-up visits, they were contacted by administrative personnel.

In the event of any clinically suspicious symptoms and/or elevation

of tumour markers, computed tomography was performed.

Values represent the means [standard deviation (SD)]

in the case of a normal distribution, or the medians (range) in the

case of a skewed distribution. T-tests and one-way ANOVA were used

to compare the duration of hysteroscopy and clinicopathological

parameters. Correlations are described by Spearman’s correlation

coefficient. Survival probabilities were calculated by the product

limit method of Kaplan and Meier. Differences between groups were

tested using the log-rank test. The results were analyzed for the

endpoint of disease-free survival. Events were defined as

recurrence, death or progression at the time of last follow-up.

Survival times of disease-free patients or patients with stable

disease were censored with the last follow-up date. Survival times

of patients who died due to other causes were censored with the

date of death. Univariate analysis and a multivariate Cox

regression model for disease-free survival were performed using

duration of hysteroscopy (≤15 vs. >15 min), FIGO tumour stage

(FIGO I vs. FIGO II–IV), histological grade (G1+G2 vs. G3) and

histological subtype (type I vs. type II). p-values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant. The statistical software SPSS

16.0 for Mac (SPSS 16.0.1; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used

for statistical analysis.

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Medical University of Vienna and the General

Hospital of Vienna.

Results

Patient characteristics are provided in Table I. Lymph node status was available

in 147/552 (27%) patients. Lymph node involvement was noted in

27/552 (5%) patients. Adjuvant radiotherapy was administered to

298/552 (54%) patients and 45/552 (8%) patients received adjuvant

chemotherapy.

| Table I.Patient characteristics. |

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Parameter | |

|---|

| Total no. of patients

enrolled | 552 |

| Age at diagnosis in

years, mean (SD) | 66.7 (10.9) |

| Histological type, n

(%) | |

| Type I | 520 (94.2) |

| Type II | 32 (5.8) |

| Tumour stage, n

(%) | |

| FIGO IA | 78 (14.1) |

| FIGO IB | 259 (46.9) |

| FIGO IC | 91 (16.5) |

| FIGO IIA | 24 (4.3) |

| FIGO IIB | 27 (4.9) |

| FIGO III | 59 (10.8) |

| FIGO IV | 14 (2.5) |

| Histological grade, n

(%) | |

| G1 | 236 (42.8) |

| G2 | 214 (38.8) |

| G3 | 102 (18.4) |

| Peritoneal cytology,

n (%) | |

| No. of patients

with positive peritoneal cytology | 109 (19.7) |

| Recurrence status, n

(%) | |

| No. of patients

with recurrent disease | 61 (11.1) |

| Time to recurrent

disease in months (SD) | 35.5 (28.9) |

| Status at last

observation, n (%) | |

| Alive with no

evidence of disease | 439 (79.5) |

| Progressive

disease | 23 (4.2) |

| Tumour-related

death | 38 (6.9) |

| Death due to other

causes | 52 (9.4) |

The mean (SD) duration of hysteroscopy in all

patients was 18.2 (10.5) min. The mean (SD) duration of

hysteroscopy in patients with positive (n=109) and negative

peritoneal cytology (n=443) was not statistically different [17.9

(10.1) min vs. 17.9 (10.2) min, respectively; p=0.9]. There were no

statistically significant correlations between duration of

hysteroscopy (as a continuous variable) and positive peritoneal

cytology (p=0.6; rho=−0.028), FIGO stage (p=0.2; rho=−0.080), lymph

node involvement (p=0.2; rho=0.106) and patient age (p=0.5;

rho=0.033). The associations between duration of hysteroscopy and

clinicopathological parameters are provided in Table II. Longer duration of hysteroscopy

was not associated with positive peritoneal cytology, advanced

tumour stage, histological grade, histological type, lymph node

involvement or advanced patient age.

| Table II.Relationship between

clinicopathological parameters and duration of hysteroscopy in 552

patients with endometrial cancer. |

Table II.

Relationship between

clinicopathological parameters and duration of hysteroscopy in 552

patients with endometrial cancer.

| HSC ≤15 min

(n=312) | HSC >15 min

(n=240) | p-valuea |

|---|

| Tumour stage | | | |

| FIGO I | 234 (75%) | 194 (81%) | 0.3 |

| FIGO II–IV | 78 (25%) | 46 (19%) | |

| Age at first

diagnosis | | | |

| ≤65 years | 154 (49%) | 107 (45%) | 0.4 |

| >65 years | 158 (51%) | 133 (55%) | |

| Peritoneal

cytology | | | |

| Yes | 62 (20%) | 47 (20%) | 0.8 |

| No | 208b (67%) | 170b (71%) | |

| Histological

grade | | | |

| G1+2 | 249 (80%) | 201 (84%) | 0.5 |

| G3 | 63 (20%) | 39 (16%) | |

| Histological

type | | | |

| Type I | 297 (95%) | 223 (93%) | 0.5 |

| Type II | 15 (5%) | 17 (7%) | |

| Lymph node

involvement | | | |

| Yes | 11 (4%) | 16 (7%) | 0.1 |

| No | 301c (96%) | 224c (93%) | |

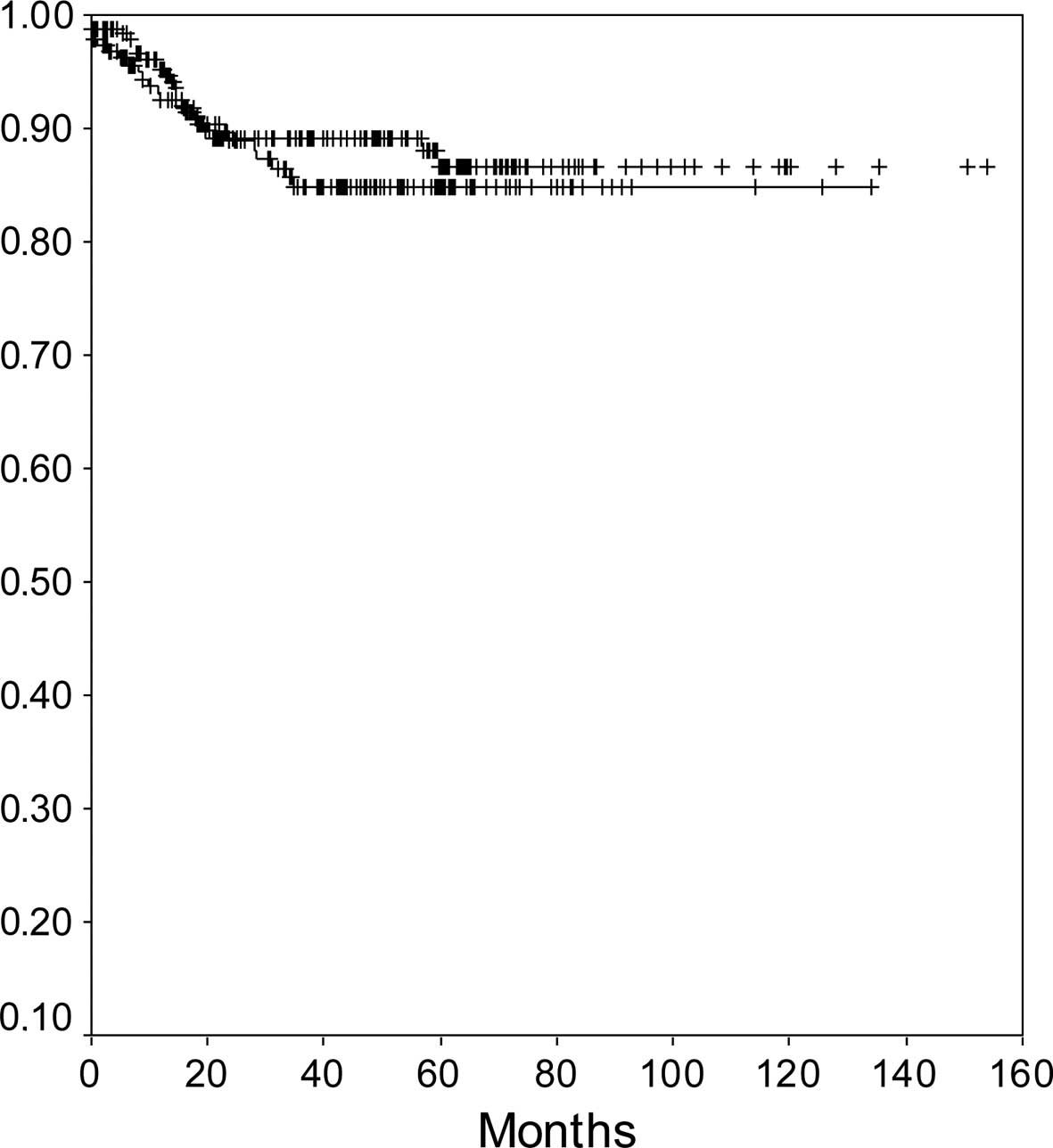

In a univariate analysis, tumour stage (FIGO I vs.

II–IV), histological grade (G1+G2 vs. G3), histological type (type

I vs. II), lymph node involvement (yes vs. no) and patient age (as

a continuous variable), but not duration of hysteroscopy (as a

continuous variable), were associated with disease-free survival.

In a multivariate analysis, tumour stage, histological grade,

histological subtype and lymph node involvement were associated

with disease-free survival. Results of the univariate and

multivariate Cox-regression models and log-rank tests with respect

to disease-free survival are shown in Table III. When patients were grouped

according to the duration of hysteroscopy, patients with a duration

of hysteroscopy ≤15 and >15 min had a 5-year recurrence-free

survival rate of 87 and 85%, respectively [p=0.4; hazard ratio

(HR)=1.2, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.7–2.2] (Fig. 1).

| Table III.Univariate Kaplan Meier analysis and

multivariate Cox regression model of prognostic covariates and

recurrence-free survival in 552 patients with endometrial

cancer. |

Table III.

Univariate Kaplan Meier analysis and

multivariate Cox regression model of prognostic covariates and

recurrence-free survival in 552 patients with endometrial

cancer.

| Univariatea

| Multivariateb

|

|---|

| p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|

| FIGO stage (I vs.

II–IV) | <0.00001 | 5.1 (2.5–10.2) | <0.0001 |

| Tumour grading (G1+2

vs. G3) | 0.05000 | 1.7 (0.9–3.3) | 0.0800 |

| Age (>65 vs. ≤65

years) | 0.00200 | 2.4 (1.3–4.2) | 0.0030 |

| Lymph node

involvement (yes vs. no) | 0.01000 | 3.2 (1.2–8.8) | 0.0200 |

| Histological type

(type I vs. II) | 0.10000 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.3000 |

| Duration of HSC (≤15

vs. >15 min) | 0.40000 | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 0.4000 |

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated whether a

prolonged duration of hysteroscopy leads to a higher risk of

positive peritoneal cytology and an increased risk of recurrence in

women with endometrial cancer. We found that the duration of

hysteroscopy was not associated with positive peritoneal cytology

nor was it a prognostic parameter for recurrence-free survival. We

conclude from these data that longer duration of hysteroscopy in

patients with endometrial cancer is oncologically safe. It does not

increase the risk of positive peritoneal cytology and does not

adversely impact prognosis.

A number of studies have demonstrated that

hysteroscopy increases the risk of positive peritoneal cytology and

upstaging among women with endometrial cancer. For example, in a

recent meta-analysis of 9 studies and 1,015 patients, Polyzos et

al reported a significantly higher rate of malignant peritoneal

cytology after hysteroscopy with an odds ratio of 1.78 (9). Thus, even though there is no clear

evidence of an adverse prognostic effect of hysteroscopy and

positive peritoneal cytology is no longer part of the FIGO staging

system (9–13), concerns remain. Since endometrial

cancer in general is associated with a favorable prognosis, subtle

effects may be difficult to detect. Also, relevant confounders,

such as the histological type of endometrial cancer or the duration

of hysteroscopy, may influence the effect of this procedure on

cancer cell spread and prognosis. These issues are of clinical

relevance, since the duration of hysteroscopy is a potential risk

factor under the control of the treating physician. Therefore, we

investigated the influence of the duration of hysteroscopy on the

risk of positive peritoneal cytology and recurrence-free survival

in a large retrospective cohort study using a multi-centre study

approach. We found that duration of hysteroscopy, both as a

continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable with an arbitrary

cutoff point of 15 min, was not associated with the rate of

positive peritoneal cytology at the time of surgery or with the

duration of disease-free survival. The results of our study have

clinical implications, since they demonstrate that hysteroscopy can

be used safely in women with suspected endometrial cancer even when

a prolonged procedure is necessary to obtain an optimal diagnostic

result. Also, these data support the new 2009 FIGO staging revision

which omits stage IIIA based on positive peritoneal cytology

only.

Our study has limitations which include the

retrospective study design and the inclusion of multiple surgeons

and centers. Thus, we cannot exclude selection and ascertainment

bias. For example, technical expertise and equipment standards may

vary among surgeons and centers as well as over time, and specific

patient populations may or may not preferentially choose the

centers included in this study. Also, hydrostatic pressure during

hysteroscopy was not assessed. On the other hand, hysteroscopy is a

relatively simple and well-standardized procedure, thus minimizing

these effects. The strength of our study is the large number of

patients allowing for an accurate estimate of the association

between duration of hysteroscopy and clinicopathological parameters

and prognosis.

In summary, our results demonstrate that prolonged

duration of hysteroscopy is not associated with an increased risk

of positive peritoneal cytology and it does not adversely affect

the extent of recurrence-free survival. Therefore, hysteroscopy may

be used safely in women with suspected endometrial cancer, even

when the procedure requires an extended duration due to technical

or other circumstances.

References

|

1.

|

Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L

and Thomas DB: Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. VIII. IARC

Press; Lyon: 2002

|

|

2.

|

Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P,

Beller U, Benedet JL, Heintz AP, Ngan HY, Sideri M and Pecorelli S:

Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. J Epid Biostat. 6:47–86.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Coulter A, Kelland A and Long A: The

management of menorrhagia. Effective Health Care Bull. 9:1–14.

1995.

|

|

4.

|

Spencer CP and Whitehead MI: Endometrial

assessment revisited. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 106:623–632. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Mencaglia L: Hysteroscopy and

adenocarcinoma. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 22:573–579.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Clark TJ, Voit D, Gupta JK, Hyde C, Song F

and Khan KS: Accuracy of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis of

endometrial cancer and hyperplasia: a systemic quantitative review.

JAMA. 288:1610–1621. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Nagele F, Wieser F, Deery A, Hart R and

Magos A: Endometrial cell dissemination at diagnostic hysteroscopy:

a prospective randomized cross-over comparison of normal saline and

carbon dioxide uterine distension. Hum Reprod. 14:2739–2742. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8.

|

Obermair A, Geramou M and Gucer F: Does

hysteroscopy facilitate tumor cell dissemination? Incidence of

peritoneal cytology from patients with early stage endometrial

carcinoma following dilatation and curettage versus hysteroscopy

and dilatation and curettage. Cancer. 88:139–143. 2000.

|

|

9.

|

Polyzos NP, Mauri D, Tsioras S, Messini

CI, Valachis A and Messinis IE: Intraperitoneal dissemination of

endometrial cancer cells after hysteroscopy: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 20:261–267. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Obermair A, Geramou M, Tripcony L, Nicklin

JL, Perrin L and Crandon AJ: Peritoneal cytology: impact on

disease-free survival in clinical stage I endometrioid

adenocarcinoma of the uterus. Cancer Lett. 164:105–110. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Selvaggi L, Cormio G, Ceci O, Loverro G,

Cazzolla A and Bettocchi S: Hysteroscopy does not increase the risk

of microscopic extrauterine spread in endometrial carcinoma. Int J

Gynecol Cancer. 13:223–227. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Cicinelli E, Tinelli R, Colafiglio G,

Fortunato F, Fusco A, Mastrolia S, Fucci AR and Lepera A: Risk of

long-term pelvic recurrences after fluid minihysteroscopy in women

with endome-trial carcinoma: a controlled randomized study.

Menopause. 17:511–515. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Ben-Arie A, Tamir S, Dubnik S, Gemer O,

Ben Shushan A, Dgani R, Peer G, Barnett-Griness O and Lavie O: Does

hysteroscopy affect prognosis in apparent early-stage endometrial

cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 18:813–819. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Serden SP: Diagnostic hysteroscopy to

evaluate the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol

Clin North Am. 27:277–286. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

O’Rogerson L and Duffy S: A national

survey of outpatient hysteroscopy. Gynecol Endosc. 10:343–348.

2001.

|

|

16.

|

Nag S, Erickson B, Parikh S, Gupta N,

Varia M and Glasgow G: The American Brachytherapy Society

recommendations for high-dose-rate brachytherapy for carcinoma of

the endometrium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 48:779–790. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|