Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent degenerative

disease of the joints affecting a large number of individuals

worldwide. It is estimated that 2/3 individuals older than 60 years

of age suffer from OA and the number of individuals suffering from

this disease is increasing (1).

Among the clinical manifestations of the disease, those including

joint pain are the most common. These manifestations appear with

functional limitation at different levels, reducing the quality of

life of affected patients. The pathological changes associated with

OA are subchondral bone remodeling, synovial inflammation and the

progressive degeneration of articular cartilage (2).

The cause of the cartilage damage involves the

destruction of the shift which maintains the balance between

chondrocyte anabolic and catabolic capacities. This balance, by

means of producing various types of proteins associated with the

matrix, enzymes, as well as cytokines, maintains the extracellular

matrix (2). OA is triggered by

the imbalance between chondrocyte catabolic and anabolic

activities. For most individuals, in spite the fact that the

etiology of OA has not yet been thoroughly elucidated, it is

acceptable to say that the production of excess inflammatory

cytokines is key to the development of OA (3). It has been demonstrated that

interleukin-1β (IL-1β), one of the cytokines with pro-inflammatory

effects, is of particular importance to the development of the

disease (4). By increasing the

production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), IL-1β facilitates

the degradation of the cartilage matrix (4). At the same time, it may induce the

expression of inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase (iNOS) and

cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [which contributes to the production of

higher levels of NO and prostaglandin E2

(PGE2)] (5). It has

been found that NO is capable of upregulating the production of

inflammatory cytokines and MMPs, as well as inducing chondrocyte

apoptosis. PGE plays a role in both joint pain and bone resorption.

PGE2 is also capable of mediating cartilage matrix

degradation by promoting the activity of MMPs and other

inflammatory cytokines (6).

To date, there is no available totally effective

therapy for OA as a multifactorial degenerative joint disorder.

Current treatment strategies for individuals suffering from this

disease aim at controlling joint swelling and pain, and delaying

the progression of the disease, as well as improving the quality of

life of patients (5). Primarily,

balneotherapy has been adopted as a treatment strategy. This

ancient treatment method is applied by immersion in water with

various chemical, thermal and mechanical properties (7). A previous study demonstrated that

for rats with chronic experimental arthritis, therapy using a

sulfur bath produced an anti-inflammatory result (8). This method has been adopted for the

treatment of a number of patients with OA and rheumatic diseases;

as previously demonstrated, patients spent 2–3 weeks being

subjected to sulphurous mud-bath therapy at a spa in Italy

(9). In addition, it has been

discovered by some recently conducted research that hydrogen

sulfide (H2S) is possibly a very important contributor

to the positive effects of sulfur baths (10).

It is now considered that H2S, carbon

monoxide (CO) and NO belong to the same group of endogenously

produced gas molecules. Nevertheless, studies on the biological

function of H2S are limited and fewer than those on CO

and NO. Emerging evidence indicates that H2S is crucial

for a number of pathological and physiological processes, such as

for example, in metabolic disorders including diabetes (11). Relevant studies have indicated

that 30–100 μM concentrations of physiological

H2S exert antinociceptive effects (12). In spite of the fact that relevant

data have provided information regarding the mechanisms of action

and precise sites of action of the inflammatory mediator,

H2S, these mechanisms and sites of action have not yet

been fully elucidated. It seems that the upregulation of, for

example, the production of CO, is capable of mediating some of the

anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of H2S.

This mediating process, by means of inflammatory stimuli, leads to

the inhibition of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway and the

downregulation of iNOS expression (13).

In terms of the potential role of H2S in

OA, to the best of our knowledge, there is no relevant information

currently available. According to our previous studies, the

concentrations of H2S contained in the synovial fluid

aspirated from the knee joints of patients with OA are higher than

those in the synovial fluid from individuals without OA

(unpublished data). Analogously, other studies have demonstrated

that human cartilage cells have the capacity to synthesize

H2S. This is observed as part of an acute response to

the so-called pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, tumor

necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). It has been

suggested that cytokine-induced H2S synthesis may be

used to prevent oxidative injury to joint cells (14,15). According to previous findings,

both the decrease in leukocyte velocity and synovial leukocyte

adherence (independent of the dose used) may be caused by

H2S (16), indicating

the anti-inflammatory effects of H2S in OA. However, the

anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action and effects of

H2S on chondrocyte inflammatory responses induced by

IL-1β have not yet been fully clarified. In the process, NF-κB as

an inducible transcription factor is important for the control of

the transcription of inflammatory response genes (17,18). It is known that mitogen-activated

protein kinases (MAPKs) function as upstream activators of NF-κB.

It is evident that as regards NF-κB activity, extracellular

signal-regulated kinase (ERK) is an important temporal regulator.

When ERK1/2 is depleted using inhibitors, NF-κB activation is

reduced, inhibiting NF-κB-dependent gene transcription (19). Therefore, based on these findings,

the present study was conducted to determine the following: i) the

effects of H2S on the IL-1β-induced expression of

chondrocyte catabolic factors and ii) whether H2S

protects chondrocytes from damage through the ERK-NF-κB channel in

OA. To better conduct the evaluation of the chondroprotective

effects of H2S and to offer an advanced basis for the

clinical treatment of OA in the future, further knowledge of the

underlying mechanisms may be required.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), recombinant human IL-1β,

collagenase type II, PD98058 (an inhibitor of ERK), Toluidine blue,

Safranin O, and hematoxylin and eosin were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO,USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s

Medium (DMEM), penicillin and streptomycin, fetal bovine serum

(FBS), and 0.25% trypsin were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Grand

Island, NY, USA). The cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased

from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). The Griess reagent

assay kit was obtained from the Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology

(Haimen, China). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit

was provided by Boster Bio-Engineering Limited Company (Wuhan,

China). TRIzol Reagent and the One-Step qPCR kit were purchased

from Tiangen Biotech Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Antibodies against

ERK1/2/phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), IκBα/phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36)

and NF-κB p65/phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) and β-actin were purchased

from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). The NF-κB

(p65) transcription factor assay kit was purchased from Active

Motif (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated.

Chondrocyte isolation and culture

The purpose and nature of the study were clearly

explained to the patients and written informed consent was obtained

from all patients, and the study was approved by the Institutional

Ethics Review Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao

University, Qingdao, China. Our obtained human cartilage samples

were selected from OA sufferers who had undergone total knee

arthroplasty. OA was diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and

Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism

Association. Patients with the same grade of OA were included in

our study. Patients who had received an intra-articular injection

of steroids were excluded from our study.

After the cartilage was subjected to 30 min of

digestion with 0.25% trypsin, it was then digested with 2 mg/ml

collagenase II in DMEM for 6 h. The cells were suspended in DMEM

with 15% FBS and antibiotics and then seeded in tissue culture

flasks. Confluent cells were split at 1:3. An inverted phase

contrast microscope (Olympus CK40, Germany) was used to observe the

morphology of the chondrocytes cultured in vitro. The

chondrocytic phenotype was confirmed by microscopic evaluation, by

staining for glycosaminoglycan production (hematoxylin and eosin,

Toluidine blue and Safranin O staining). Cells between passages 3

and 4 were used in the experiments.

H2S donor

NaHS is universally adopted and in this regard, it

functions as an H2S donor. NaHS is used to obtain

H2S, as well as to define the H2S

concentration in a solution. Compared with the defining method of

measuring bubbling H2S gas, this method is not only more

reproductive, but also more accurate. Immediately prior to use from

a solution of 200 mM NaHS stock, the solution containing NaHS was

prepared. NaHS is dissociated to HS− and Na+

(in solution) at first. It is then dissociated to HS−

and binds to H+; H2S is then formed. Under

certain conditions, 18.5% of H2S/HS− exists

(in a non-dissociated form). Without knowing the active form of

H2S, as regards the total number of the forms of

H2S, we used the terminology ‘H2S’.

Therefore, a solution of H2S with a concentration at the

level of approximately 1/3 of the NaHS original concentration was

provided, as previously described (20).

Cell viability assay

We detected cell viability using the CCK-8 assay and

cultured the chondrocytes in the exponential phase at

1x104 cells/ml concentration in 96-well plates. Each

group contained 4 duplicate wells. As soon as the cells reached

70–80% confluence, the cells were treated using conditioned medium,

which contained various concentrations of H2S.

Subsequently, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution were

added to each well and the cells were placed in an incubator for

incubation. The incubation period lasted for 4 h. We performed

measurements for absorbance at 450 nm, with the help of a

microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and

calculated the percentage cell viability in 4 wells, calculating

the optical density (OD) value in specific groups.

The calculation was realized based on a relevant

formula: cell viability percentage = (OD treatment group - OD blank

group)/(OD control group - OD blank group) x100. The experiment was

carried out in triplicate.

Measurement of MMP-13, PGE2

and NO production in culture supernatants

We cultured the human OA chondrocytes

(1×106 cells/ml) in 6-well plates in complete DMEM with

10% FBS. The human OA chondrocytes (>85% confluent) were

serum-starved before being treated with various doses of NaHS

(0.06, 0.15, 0.3, 0.6 and 1.5 mM) for 30 min followed by

stimulation with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Twenty-four

hours after the addition of IL-1β, we collected the cell

conditioned medium and then stored it at −80°C until analysis. The

concentration of PGE2 and MMP-13 was quantified using

MMP-13- and PGE2-specific ELISA kits in accordance with

the instructions of the manufacturer (Boster Bio-Engineering

Limited Company). The plates were read at 450 nm. In order to

measure NO production, we measured the nitrite concentration in the

culture supernatants using Griess reagent. The absorbance was read

at 540 nm.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) for MMP-13, iNOS and COX-2

Based on the instructions of Tiangen Biotech Co.,

Ltd. (Beijing, China) we used TRIzol reagent to extract the total

RNA (1 μg), which was reverse transcribed into cDNA. We used

the One-Step qPCR kit from the same company during amplification.

We also used SYBR-Green detection to determine the mRNA expression

of COX-2, iNOS and MMP-13 following the normalization of the

values. During the performing of PCR, the 7300 sequence detection

system was used. The primers used for PCR were as follows: MMP-13

forward, 5'-CGCCAGAAGAATCTGT CTAA-3' and reverse,

5'-CCAAATTATGGAGGAGATGC-3'; iNOS forward,

5'-CCTTACGAGGCGAAGAAGGACAG-3' and reverse,

5'-CAGTTTGAGAGAGGAGGCTCCG-3'; COX-2 forward,

5'-TTCAAATGAGATTGTGGGAAAA TTGCT-3' and reverse,

5'-AGATCATCTCTGCCTGAGTAT CTT-3'; and GAPDH forward

5'-GGTATCGTCGAAGGA CTCATGAC-3' and reverse, 5'-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCG

TTCAGC-3'. The thermal cycling conditions for quantitative PCR were

95°C for 2 min followed by 45 cycles (at different temperatures and

for different periods of time). We used the temperature of 68°C for

data collection. Glyceraldehyde 3- phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)

was used as an internal control. We quantified the quantitative PCR

data using the ΔCT method with the formula: n=2−(ΔCT targeted

gene - ΔCT GAPDH).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to determine the

effects of NaHS on IL-1β-dependent ERK1/2-phosphorylation,

IκBα-phosphorylation, IκBα degradation, NF-κB p65 translocation and

NF-κB p65 activity. Whole cell lysates, the chondrocyte monolayer

nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were washed with Hanks’ solution 3

times and whole cell proteins were extracted using lysis buffer on

ice for half an hour. Centrifugation (700 × g) was performed to

remove the cell debris. The supernatants were stored at −80°C until

use. We measured the total protein concentration in the

cytoplasmic, nuclear and whole cell extracts using the BCA protein

assay kit (Uptima; Interchim, Montlucon, France). During the

process, BSA was used as a standard. When the adjustments for equal

amounts of total protein were made, we separated the proteins under

reducing conditions. The separated proteins were then transferred

onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were then blocked for 30 min at

room temperature in fresh blocking buffer [0.1% Tween-20 in

Tris-buffered saline (TBS-T) containing 5% fat-free milk] and then

incubated with either anti-ERK1/2 (1:1,000 dilution), anti-p-ERK1/2

(1:1,000 dilution), anti-IκBα (1:1,000 dilution),anti-p-IκBα

(1:1,000 dilution), anti-NF-κB p65 (1:1,000 dilution), anti-p-NF-κB

p65 (1:1,000 dilution), or anti-β-actin antibodies (1:5,000

dilution) in freshly prepared TBS-T with 3% skimmed milk overnight

with gentle agitation at 4°C. Following 3 washes with TBS-T, the

membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

secondary antibody (1:3,000 dilution; Kangchen Biotech, Shanghai,

China) in TBS-T with 3% skimmed milk for 1.5 h at room temperature.

The membranes were rinsed 3 times with TBS-T, developed in ECL

solution and visualized using X-ray film. All the experiments were

repeated for no less than 3 times. ImageJ 1.47 software was used to

analyze and scan the films for quantification.

NF-κB activity assay

Based on relevant instructions provided by the

manufacturer (Active Motif), the TransAM™ NF-κB p65 transcription

factor assay kit was used to analyze the DNA-binding activity of

NF-κB. In brief, the kit with an ELISA format as its basis is used

to perform the anlaysis in a 96-well plate. During this process, in

the wells, the oligonucleotide which contained the NF-κB

consensus-binding sequence (5′-GGGACTTTCC-3′) was immobilized. We

incubated the nuclear extracts in the wells and then used a primary

antibody to perform the detection of bound NF-κB p65. We then

utilized an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for the detection of

the bound primary antibody. The HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

also laid the foundation for colorimetric quantification. Using a

microplate reader (Molecular Devices), we took measurements for the

enzymatic product at 450 nm. For the purpose of monitoring the

specificity of the assay, we added (mutated) competitive control

into the wells with the wild-type (mutated) NF-κB consensus

oligonucleotide before adding the nuclear extracts.

Statistical analysis

All experiments reported in this study were

performed independently at least 3 times and the data are expressed

as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 13.0 software. Differences

were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Chondrocyte morphology and cytochemical

characteristics

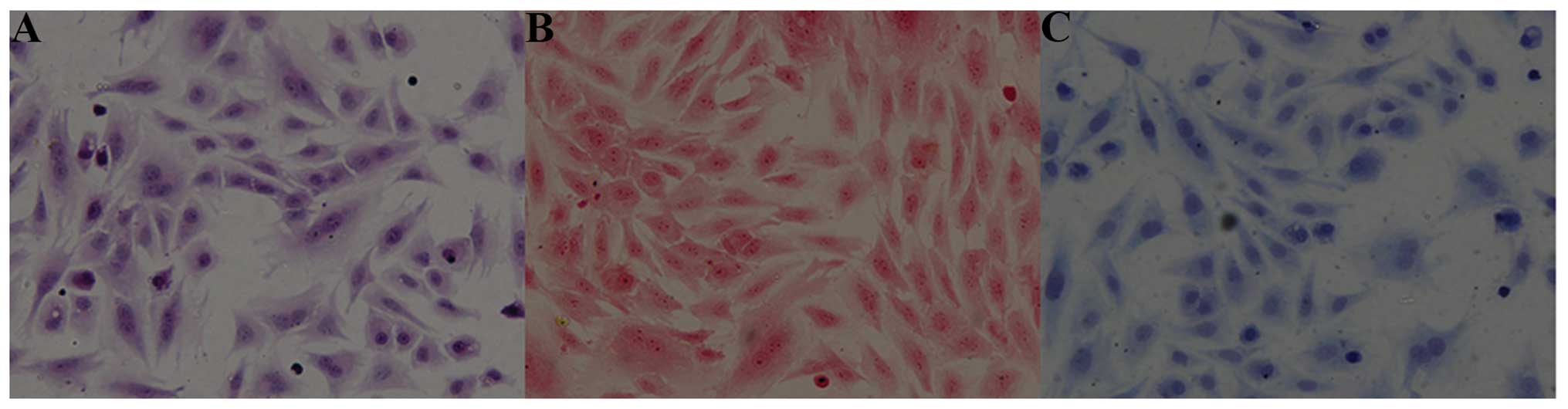

The chondrocytes were allowed to adhere to the

bottom of dishes for 4 to 12 h. In all monolayer cultures, the

chondrocytes were typically flattened and elongated in shape.

Images which were obtained following staining with hematoxylin and

eosin revealed that the nuclei were stained an amethyst color and

that the cytoplasm was stained pink (Fig. 1A). We used both Safranin O and

Toluidine blue staining for the purpose of identifying the

chondrocytes. It was found that the nuclei were stained a crimson

color (Fig. 1B), or dark blue

(Fig. 1C). Under the influence of

chondroitin and glycosaminoglycan staining, the cellular cytoplasm

was stained light blue or light red. Therefore, as shown by these

results, the OA chondrocytic phenotype was evident.

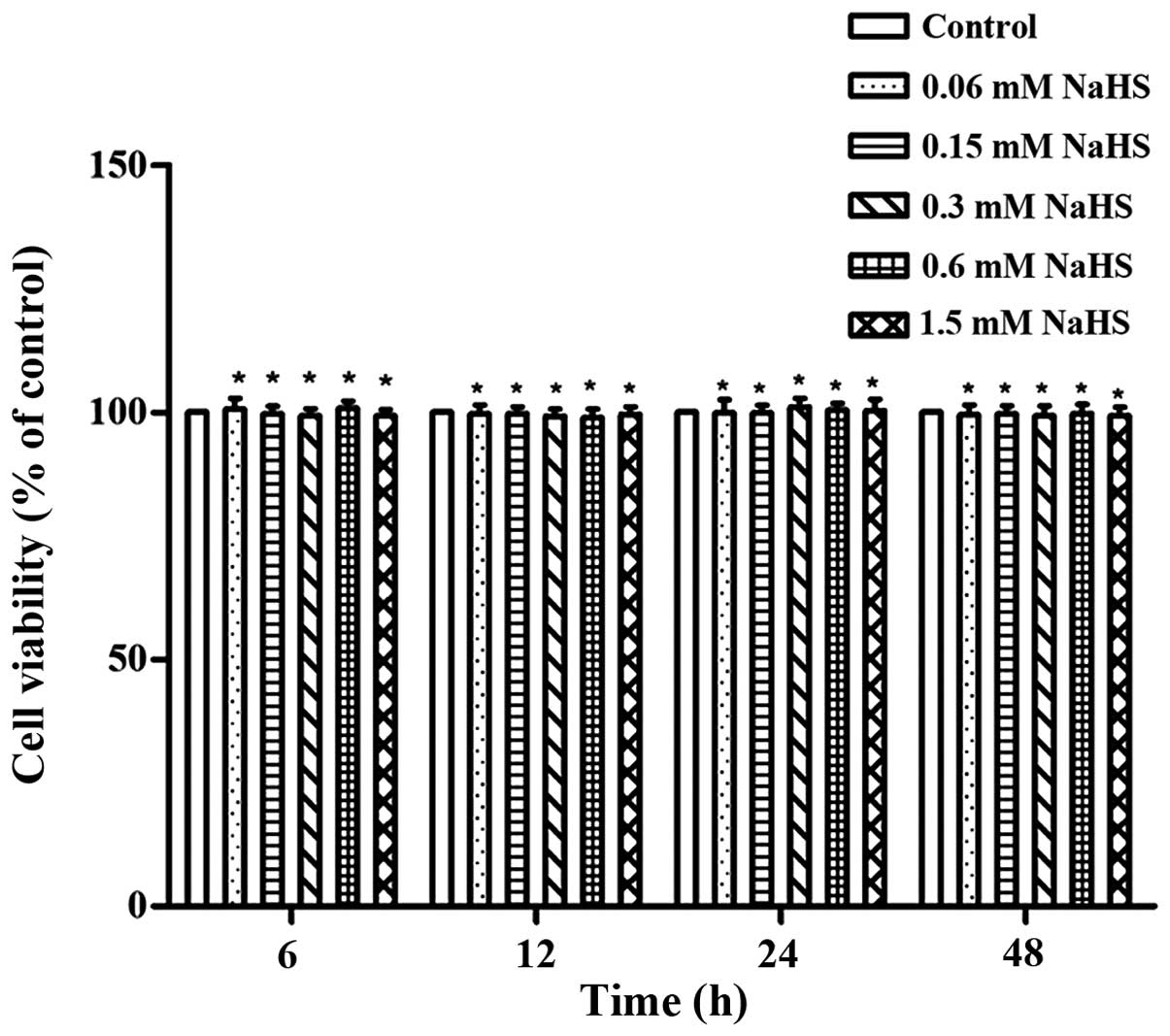

Effects of H2S on articular

chondrocyte viability

From the various H2S concentrations we

used in this study, no major cytotoxic effects on the OA

chondrocytes were observed. This was demonstrated by the assessment

of cell viability using CCK-8 assay (P>0.05; Fig. 2).

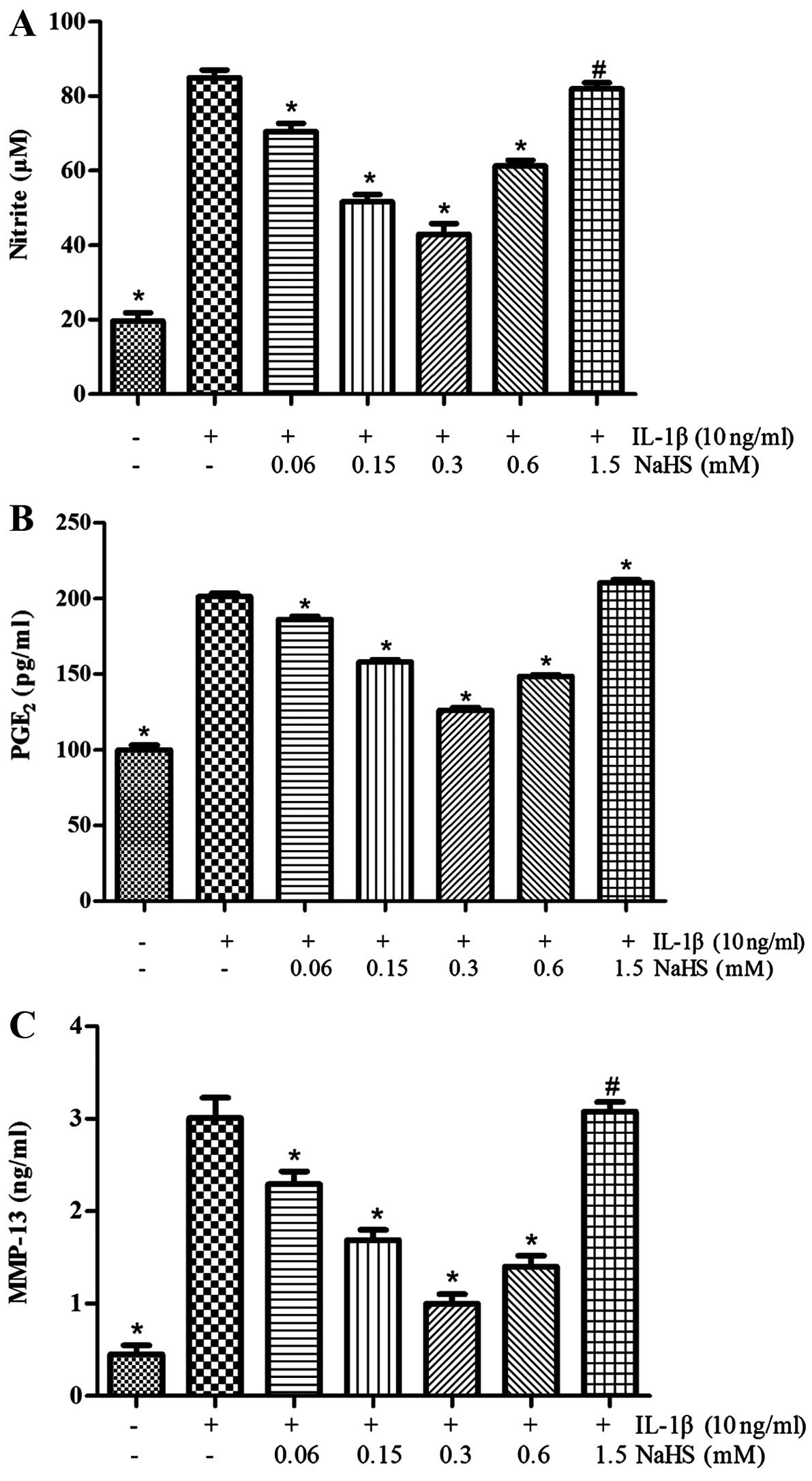

H2S suppresses the

IL-1β-induced secretion of NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 by OA

chondrocytes

As shown in Fig.

3, we determined the effects of H2S on the

generation of MMP-13, PGE2 and NO induced by IL-1β.

Various concentrations of NaHS (0, 0.06, 0.15, 0.3, 0.6 or 1.5 mM)

were used to treat the human OA chondrocytes for 30 min prior to

stimulation for 24 h with IL-1β (10 ng/ml). It was observed that

stimulation with IL-1β, compared with the unstimulated controls,

markedly promoted the production of PGE2, NO, and MMP-13

(P<0.05). However, treament of the OA chondrocytes with NaHS

(0.06, 0.15, 0.3 or 0.6 mM) prior to stimulation with IL-1β led to

a significant decrease in the production of MMP-13, PGE2

and NO (P<0.05), with the most prominent effects being observed

with the dose of 0.3 mM NaHS. CCK-8 assay revealed that cell

viability was not affected by H2S; the inhibitory

effects of H2S did not actually result in reduced cell

viability, even though the IL-1β-induced production of NO,

PGE2 and MMP-13 in the chondrocytes was not inhibited by

treatment with NaHS at the dose of 1.5 mM (P>0.05).

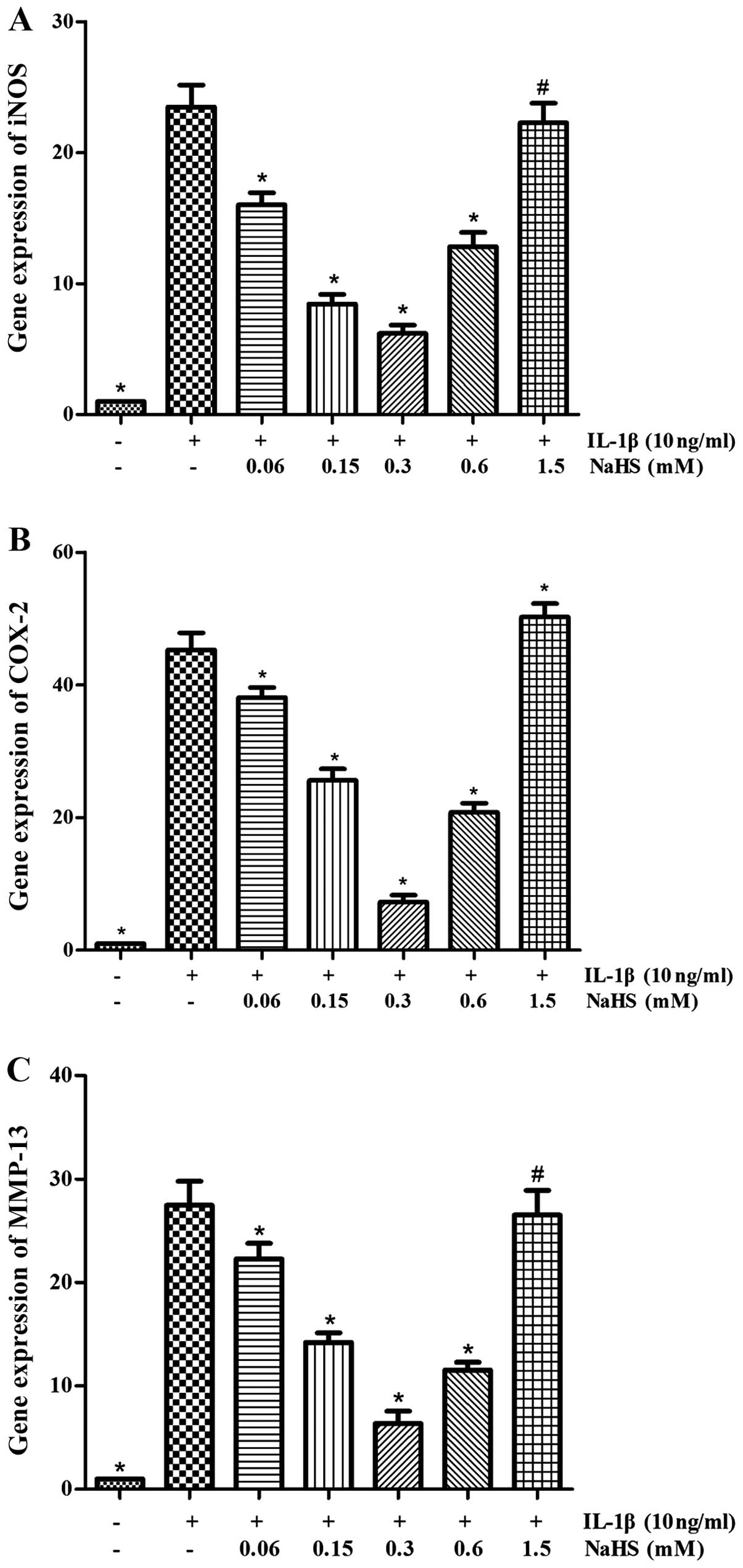

The induction of the expression of COX-2,

MMP-13 and iNOS by IL-1β in OA chondrocytes is attenuated by

H2S

The expression and production of COX-2, MMP-13 and

iNOS is crucial to the degradation of cartilage and human OA

chondrocytes (stimulated with IL-1β). We used RT-qPCR to determine

the effects of H2S on the gene expression levels of

COX-2, MMP-13 and iNOS induced by IL-1β. The results revealed that

the mRNA expression of COX-2, MMP-13 and iNOS was markedly

inhibited by NaHS (0.06, 0.15, 0.3 and 0.6 mM) (P<0.05; Fig. 4). The maximum response was

observed at the dose of 0.3 mM NaHS, in spite the fact that no

obvious inhibitory effect on the mRNA expression levels was

observed at the dose of 1.5 mM NaHS (P>0.05).

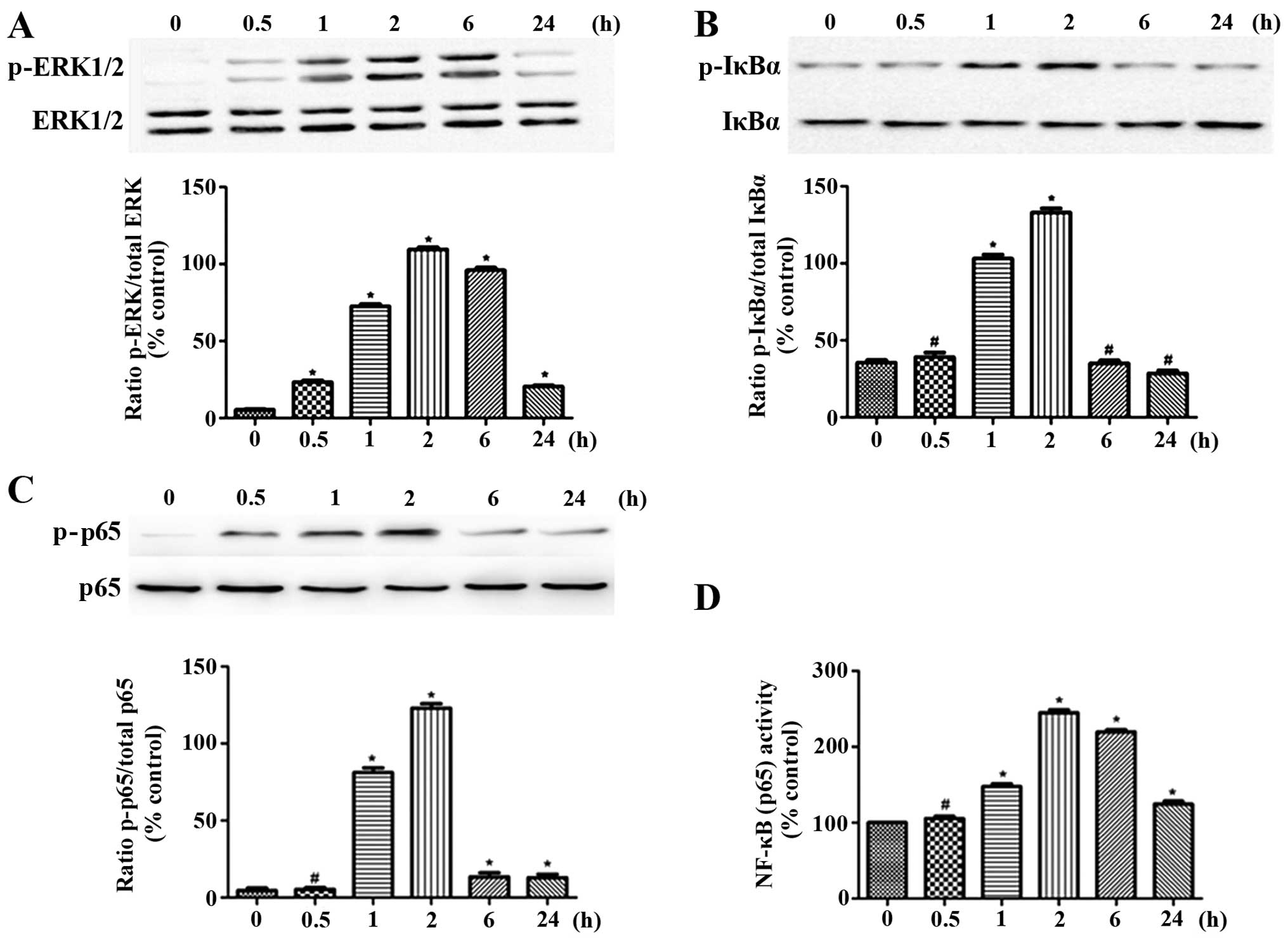

Effect of IL-1β on NF-κB signaling and

ERK1/2 activation

The activation the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways

induced by IL-1β is of great importance to the regulation cytokine

expression. We investigated the effects of IL-1β on the

phosphorylation of ERK1/2, IκBα and NF-κB p65, as well as on the

NF-κB binding activity in the OA chondrocytes at different time

points. In the control (unstimulated) OA chondrocytes, no

detectable phosphorylation of ERK1/2, IκBα and NF-κB p65 was

observed. The phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, ERK1/2 and IκBα in the

OA chondrocytes was markedly induced by stimulation with IL-1β

within a very short period of time (following treatment for 0.5, 1

and 2 h). The phosphorylation levels reached peak levels at 2 h and

then decreased to normal levels. However, stimulation with IL-1β

for longer periods of time (6 or 24 h) did not increase the

phosphorylation levels of of ERK1/2, IκBα and NF-κB p65 (Fig. 5A–C). Moreover, as regards the

NF-κB binding activity, which was in accordance with the changes

occurring during ERK1/2 activation, even though an increase was

observed within a short period of time, the activity was reduced as

time progressed (Fig. 5D). Based

on the time course, the 2 h time period was selected for use in the

subsequent experiments.

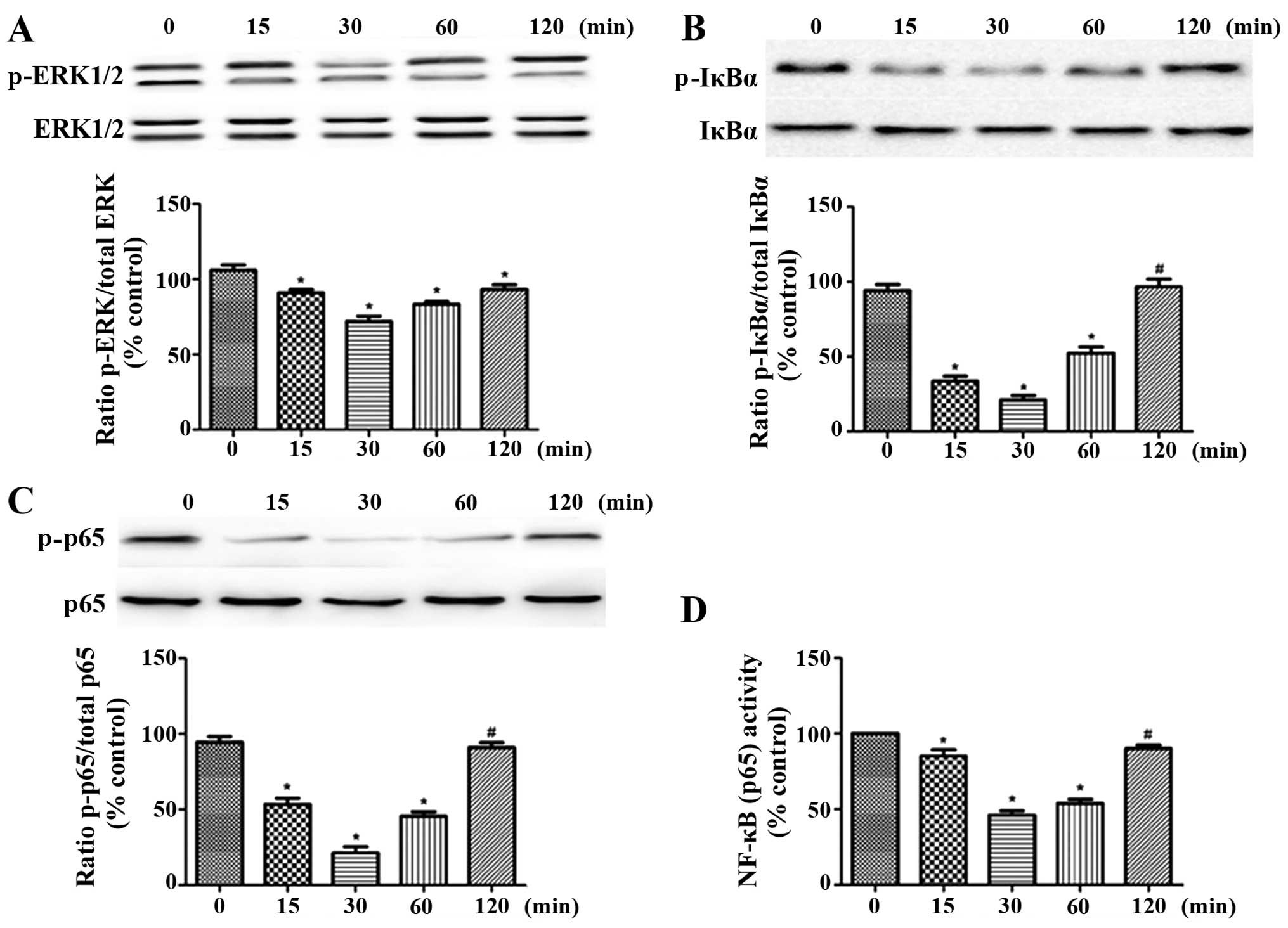

Effect of exposure time of OA

chondrocytes to H2S on ERK1/2 and NF-κB signaling

Without the involvement of IL-1β, we performed

120-min time-course experiments using 0.3 mM NaHS, and then

conducted another 2-h stimulation process with IL-1β (10 ng/ml).

The cells were lysed, and the phosphorylation levels of NF-κB p65,

IκBα and ERK1/2 were determined by western blot analysis. The NF-κB

binding activity was determined with the use of an NF-κB p65

transcription assay kit. The brief exposure of the OA chondrocytes

to NaHS led to the inhibition of the activation of NF-κB and ERK1/2

signaling induced by IL-1β (Fig.

6). The most prominent inhibitory effect of H2S was

observed in the cells pre-treated with H2S for half an

hour. Thus, pre-treatment for 30 min was used in the subsequent

experiments.

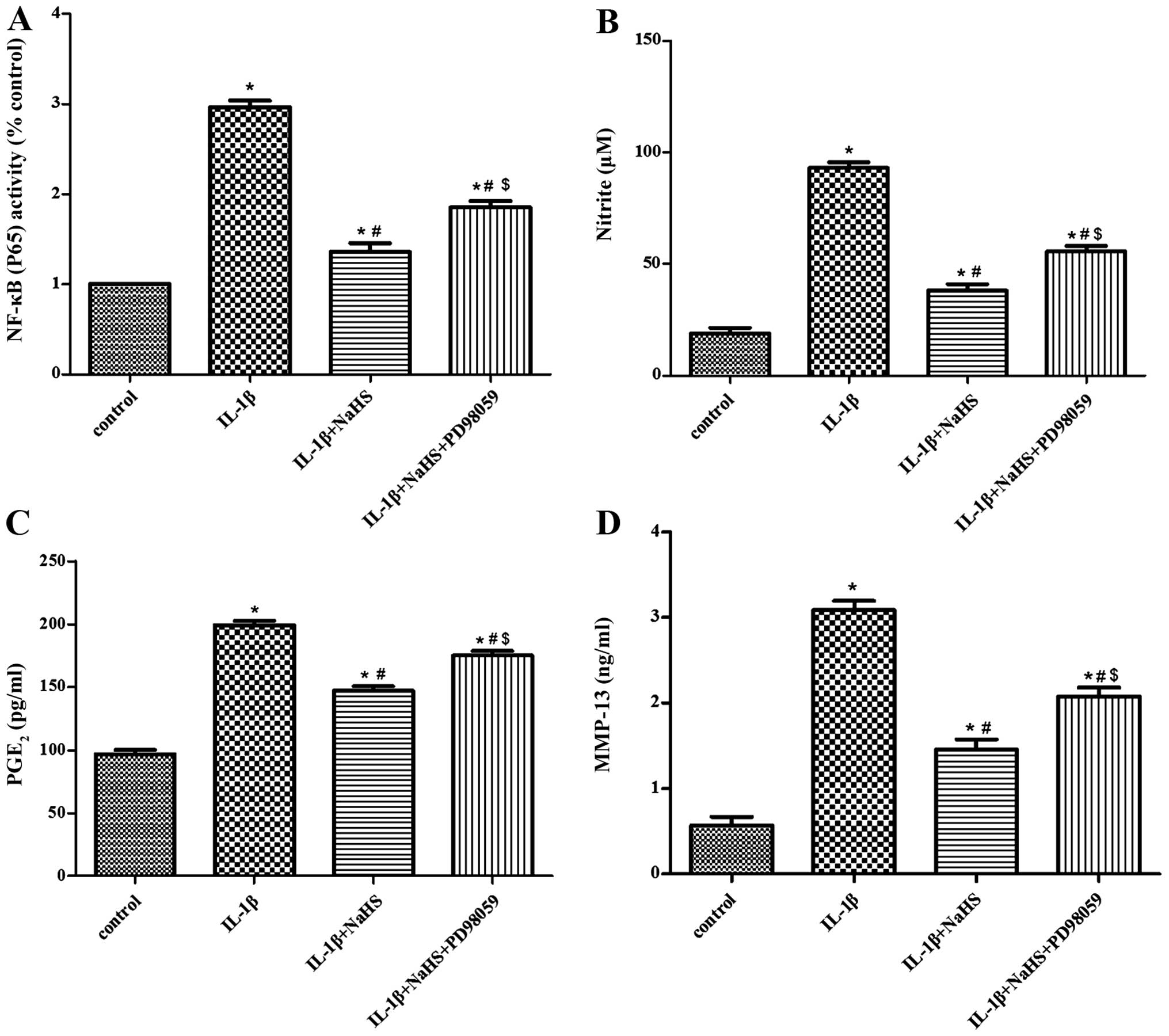

Effect of PD98059 (as an ERK pathway

inhibitor) on the suppressive effects of H2S on the

IL-1β-induced activation of NF-κB signaling

PD98059, as one of the effective inhibitors of ERK

was used by us in an effort to determine the involvement of ERK in

the suppressive effects of H2S on the IL-1β-induced

activation of NF-κB signaling. The cells were pre-incubated with

PD98059 (50 μM) for 1 h. The cells were then treated for

half an hour with NaHS (0.1 mM). Subsequently, the cells were

stimulated for 2 h with IL-1β (10 ng/ml). Following the collection

of the cell conditioned medium, the NF-κB p65 transcription assay

kit was used to perform NF-κB activity assay. In addition, the

levels of PGE2 and MMP-13 generated in the culture

medium were quantified with the use of specific ELISA kits. We also

used Griess reagent to measure the NO production. The inhibitory

effects of H2S on the IL-1β-induced activation of NF-κB

signaling were suppressed by PD98059 (Fig. 7A). The inhibitory effects of

H2S on the secretion of PGE2, MMP-13 and NO

(induced by IL-1β) were also abolished by PD98059 (Fig. 7B–D).

Discussion

Although the molecular biology of cartilage damage

in OA has been extensivey investigated (21–23), no single causative factor for

joint damage in OA has been identified to date. Generally speaking,

when the development of OA begins, synovium-produced inflammatory

mediators and cytokines are released. After being activated,

chondrocytes produce PGE2, MMPs, TNF-α and NO. Those

molecules facilitate catabolic activity and cause cartilage

structural changes (24). IL-1β

is not only important in the pathogenesis of OA, but also acts as a

powerful mediator of catabolic processes in articular chondrocytes

(25). This study used IL-1β to

mimic the pathophysiology of OA. As we had hypothesized, in

response to stimulation with IL-1β, an increase in the production

of NO, MMP-13 and PGE2 and in the expression of COX-2

and iNOS was observed. Our data demonstrate the effects of IL-1β on

the progression of OA.

A recent study demonstrated that pro-inflammatory

cytokines induce CSE (one of the H2S synthesizing

enzymes) expression and its activation through

p38-ERK-NF-κB-dependent pathways in chondrocytes, thus increasing

H2S synthesis (14).

Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no investigation on the

effects of H2S on human OA chondrocytes has been

conducted to date. Therefore, this study has a huge significance in

this regard. We demonstrated that exogenous H2S at the

doses used in this study attenuated the IL-1β-induced inflammatory

responses in vitro. Our results demonstrate that

H2S exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting

iNOS/NO and COX-2/PGE2 expression (or production), as

well as MMP-13 production by suppressing ERK1/2 and NF-κB

signaling.

Although H2S tissue production and the

levels of H2S in the blood have been the subject of much

controversy, certain studies have identified generous basal plasma

H2S levels in the 50–150 μM range according to

the spectrophotometric approach based on the indicator dye,

methylene blue (26). The

H2S concentration range in this study was decided

according to the H2S physiological level in the human

body. A previous study also revealed the cytoprotective effects of

H2S at micromolar concentrations (27). Certain cellular effects are linked

with the modulation of kinase pathways or intracellular caspases.

It was proven in this study that NaHS at the dose of 0.3 mM had the

most prominent cytoprotective effects. Previous data indicated that

exposure to H2S (millimolar) at higher concentrations

may be cytotoxic to cells. This is caused by many factors, such as

the generation of free radicals (28). According to our data, at the

concentration of 1.5 mM NaHS, H2S loses its

cytoprotective effects. It should be noted that we did not observe

any cytotoxic effects of H2S. The reason for this

difference in results between our study and other studies may be

due to the different inflammatory models used, or different

H2S donor doses used.

Among the pro-inflammatory factors, NO is a major

toxic substance with a rapid, as well as spontaneous reaction

[reacts with a superoxide anion (O2−)]. Through this

reaction, it forms both peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH; the conjugate

acid of peroxynitrite) and a peroxynitrite anion. Currently 3

isoformsof NOS have been identified. Among these isoforms, iNOS is

capable of inducing high levels of NO production, apart from its

being synthesized for response to inflammatory stimuli (29). In our study, we demonstrated that

H2S is capable of preventing the production of NO

induced by IL-1β, as well as the expression of iNOS at the mRNA

level in OA chondrocytes. Our results revealed that the inhibitory

effects of H2S on the IL-1β-induced iNOS protein

expression were mediated through the inhibition of NO production.

Our results were concurrent with those of Hu et al (30). According to their findings,

H2S is capable of inhibiting inflammation in microglia

stimulated with LPS, due to the fact that exogenous H2S

and endogenous H2S markedly suppress NO production. The

suppression of iNOS following stimulation with LPS is involved in

the mechanisms behind the anti-inflammatory effects of

H2S. H2S-NO interactions seem to be more and

more possible. Another study revealed that H2S, by

certain means, promotes both iNOS expression and NO production

(31). H2S

biosynthesis in LPS-induced endotoxemia has been shown to be

reduced by nitro-flurbiprofen-provided NO. The reason for this may

lie in transduction inhibition through the NF-κB pathway (31). It is possible that NO is capable

of controlling endogenous H2S biosynthesis and

regulating CSE expression in a positive manner. It seems that

gaseous mediator interactions are crucial; thus further studies are

warranted to investigate these interactions.

Although joint pain is one of the symptoms of OA,

information regarding the mechanisms responsible for OA-induced

pain is limited. It has been demonstrated that knee nociceptors may

be sensitized by peripheral pro-inflammatory mediators, such as

PGE2 and COX-2 (32).

IL-1β stimulates the production of COX-2 as a major inducer of pain

inflammation and a mediator in osteoarthritic joints, rather than

that of COX-1. In addition, PGE2 exerts catabolic

effects on chondrocytes (33,34). In our study, in spite of the fact

that only traces of COX-2 and PGE2 expression were

observed in the unstimulated human chondrocytes, the expression of

PGE2 and COX-2 was enhanced following stimulation with

IL-1β. We demonstrated that the addition of H2S

suppressed PGE2 production and elevated COX-2 gene

expression in the IL-1β-stimulated cells. Therefore, it is possible

that H2S exerts an anti-nociceptive effect, similar to

that of NSAIDs. This effect, by means of suppressing COX-2 and

PGE2 expression, seems to ameliorate OA symptoms. In the

study by Distrutti et al, H2S was shown to be a

promising analgesic. The systemic administration of different

H2S donors led to the opening of K+(ATP)

channels, inhibiting visceral nociception (35). Nevertheless, it was demonstrated

by Kawabata et al that either endogenous or exogenous

H2S has a peripheral activity that may promote pain. It

seems that the mechanisms of H2S-induced hyperalgesia

rely on the adjustment of T-type Ca2+ channel activity,

but are not dependent on K+(ATP) channels (36). Apart from H2S, CO and

NO also show nociceptive-related ambiguous activity (23).

MMPs are synthesized in articular joints by synovial

cells and chondrocytes. MMP-13 is considered a main cause for the

degradation of collagens and aggrecan in cartilage. It is

considered that OA chondrocytes express MMP-13 (37). Thus, MMP-13 has become a

therapeutic target with the most potential. In the present study,

we wished to determine whether H2S exerts

chondroprotective effects through the suppression of MMP-13 in

chondrocytes. Our results revealed that H2S inhibited

MMP-13 expression induced by IL-1β. This inhibition occurred at the

protein and mRNA level and was independent of the dose used in

human OA chondrocytes. The results obtained in the study by Vacek

et al were also similar. Their study demonstrated that

H2S inhibited collagen helix destruction and MMP

activation by suppressing oxidative stress (38).

The underlying cellular targets of the protective

effects of H2S on IL-1β-induced OA remain to be

elucidated. In this study, we analyzed the potential molecular

mechanisms responsible for the inhibitory effects of H2S

on inflammatory mediators in response to IL-1β in chondrocytes.

Among the downstream effects of IL-1β stimulation, many of these

effects are regulated by the activation of NF-κB signaling

(39,40). NF-κB is retained in the cytoplasm

with IκBα in an inactive state. IL-1β has the capacity to activate

NF-κB, resulting in the change of the position of NF-κB p65 so as

to regulate gene expression (17). Our results revealed that IL-1β

induced IκBα and NF-κB p65 phosphorylation, which was reduced by an

exogenous H2S donor (NaHS) at the concentration of 0.3

mM in short-term treatment (15–30 min). However, the

phosphorylation of IκBα and NF-κB p65 was not further inhibited by

long-term H2S treatment (60–120 min) following

stimulation with IL-1β. This reveals that the effects of

H2S may be produced rapidly, a fact having been

confirmed in a previous study, which demonstrated that the

inhibitory effects of H2S are not determined by the

release rate (41). Our results

are consistent with the findings of a previous study on the

protective role of GYY4137 (13).

On the whole, we found new evidence to support the hypothesis that

the NO-, PGE2- and MMP-13-mediated inflammation and

cytotoxicity are regulated by the activation of NF-κB and that

H2S protests against inflammation induced by IL-1β by

inhibiting NF-κB signaling.

It has also been suggested by previous findings that

the regulatory role of H2S on MAPK phosphorylation may

exist and that the regulation contributes to different types of

pathological and physiological roles in all types of tissues and

cells (42,43). The fact that the IL-1β-induced

phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was decreased in fibroblast-like

synoviocytes (FLS) of OA was also previously demonstrated (42,44). Since it is known that ERK1/2 is an

upstream activator of NF-κB signaling, we conducted investigations

on the relevant functions of ERK1/2. Therefore, we used the PD98059

inhitibor to block the activation of ERK1/2. The inhibition of

ERK1/2 by pre-treatment with PD98059 abolished the inhibitory

effects of H2S on cytokines following stimulation with

IL-1β, while attenuating its inhibitory effects on the activation

of NF-κB signaling induced by IL-1β. These findings, in a

straightforward manner, indicate that the cytoprotective effects of

H2S in OA may involve the ERK-NF-κB signaling pathway.

Nevertheless, attention should be paid to the fact that

pre-treatment with PD98059 did not completely abolish the

cytoprotective effects of H2S. This means that

H2S may regulate the activation of NF-κB signaling

through mediators apart from ERK1/2. According to previous

research, the inhibitory effects of H2S on inflammation

are exerted by suppressing the channels for p38 and NF-κB signaling

and by upregulating HO-1 expression (45). It is possible that the different

stimuli and different types of cells used may attribute to the

different results obtained by different studies. Nevertheless, the

regulatory mechanisms of H2S in chondrocyte inflammation

remain to be fully elucidated. Further studies are warranted to

determine the precise channels of signaling involved in this

process.

In conclusion, this study proves that a

cytoprotective effect against OA induced by IL-1β is conferred by

H2S, and that the process is realized by suppressing the

channel for ERK-NF-κB signaling in chondrocytes, which is activated

by IL-1β. This study has provided new insight into the

cytoprotective effects H2S in OA. The data from our

study also suggest that H2S may prove to be a potential

therapeutic agent for the treatment of OA.

Acknowledgments

The completion of this study was possible due to the

assistance and support of the Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant NSFC 81141078 to K.S.).

References

|

1

|

Arden NK and Leyland KM: Osteoarthritis

year 2013 in review: clinical. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

21:1409–1413. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sulzbacher I: Osteoarthritis: histology

and pathogenesis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 163:212–219. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Berenbaum F: Osteoarthritis as an

inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!).

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 21:16–21. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wojdasiewicz P, Poniatowski LA and

Szukiewicz D: The role of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory

cytokines in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm.

2014:5614592014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Balaganur V, Pathak NN, Lingaraju MC, et

al: Chondroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of

S-methylisothiourea, an inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor

in cartilage and synovial explants model of osteoarthritis. J Pharm

Pharmacol. 66:1021–1031. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Goldring MB, Otero M, Plumb DA, et al:

Roles of inflammatory and anabolic cytokines in cartilage

metabolism: signals and multiple effectors converge upon MMP-13

regulation in osteoarthritis. Eur Cell Mater. 21:202–220.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Boers M,

et al: Balneotherapy for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 4:CD0068642007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ekundi-Valentim E, Santos KT, Camargo EA,

Denadai-Souza A, Teixeira SA, Zanoni CI, Grant AD, Wallace J,

Muscará MN and Costa SK: Differing effects of exogenous and

endogenous hydrogen sulphide in carrageenan-induced knee joint

synovitis in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 159:1463–1474. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Costantino M, Filippelli A, Quenau P,

Nicolas JP and Coiro V: Sulphur mineral water and SPA therapy in

osteoarthritis. Therapie. 67:43–48. 2012.In French. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kloesch B, Liszt M and Broell J:

H2S transiently blocks IL-6 expression in rheumatoid

arthritic fibroblast-like synoviocytes and deactivates p44/42

mitogen-activated protein kinase. Cell Biol Int. 34:477–484. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang R: Hydrogen sulfide: the third

gasotransmitter in biology and medicine. Antioxid Redox Signal.

12:1061–1064. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lowicka E and Beltowski J: Hydrogen

sulfide (H2S) - the third gas of interest for

pharmacologists. Pharmacol Rep. 59:4–24. 2007.

|

|

13

|

Li L, Fox B, Keeble J, et al: The complex

effects of the slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor GYY4137 in a

model of acute joint inflammation and in human cartilage cells. J

Cell Mol Med. 17:365–376. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fox B, Schantz JT, Haigh R, et al:

Inducible hydrogen sulfide synthesis in chondrocytes and

mesenchymal progenitor cells: is H S a novel cytoprotective

mediator in the inflamed joint? J Cell Mol Med. 16:896–910. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Whiteman M, Haigh R, Tarr JM, Gooding KM,

Shore AC and Winyard PG: Detection of hydrogen sulfide in plasma

and knee-joint synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis patients:

relation to clinical and laboratory measures of inflammation. Ann

NY Acad Sci. 1203:146–150. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Andruski B, McCafferty DM, Ignacy T,

Millen B and McDougall JJ: Leukocyte trafficking and pain

behavioral responses to a hydrogen sulfide donor in acute

monoarthritis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol.

295:R814–R820. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rigoglou S and Papavassiliou AG: The NF-κB

signalling pathway in osteoarthritis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

45:2580–2584. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kloesch B, Liszt M, Krehan D, Broell J,

Kiener H and Steiner G: High concentrations of hydrogen sulphide

elevate the expression of a series of pro-inflammatory genes in

fibroblast-like synoviocytes derived from rheumatoid and

osteoarthritis patients. Immunol Lett. 141:197–203. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jiang B, Xu S, Hou X, Pimentel DR, Brecher

P and Cohen RA: Temporal control of NF-kappaB activation by ERK

differentially regulates interleukin-1beta-induced gene expression.

J Biol Chem. 279:1323–1329. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhi L, Ang AD, Zhang H, Moore PK and

Bhatia M: Hydrogen sulfide induces the synthesis of proinflammatory

cytokines in human monocyte cell line U937 via the ERK-NF-kappaB

pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 81:1322–1332. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Stolz M, Gottardi R, Raiteri R, et al:

Early detection of aging cartilage and osteoarthritis in mice and

patient samples using atomic force microscopy. Nat Nanotechnol.

4:186–192. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gossan N, Zeef L, Hensman J, et al: The

circadian clock in murine chondrocytes regulates genes controlling

key aspects of cartilage homeostasis. Arthritis Rheum.

65:2334–2345. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tsubota M and Kawabata A: Role of hydrogen

sulfide, a gasotransmitter, in colonic pain and inflammation.

Yakugaku Zasshi. 134:1245–1252. 2014.In Japanese. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Houard X, Goldring MB and Berenbaum F:

Homeostatic mechanisms in articular cartilage and role of

inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 15:3752013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang X, Li F, Fan C, Wang C and Ruan H:

Effects and relationship of ERK1 and ERK2 in interleukin-1β-induced

alterations in MMP3, MMP13, type II collagen and aggrecan

expression in human chondrocytes. Int J Mol Med. 27:583–589.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Szabo C: Hydrogen sulphide and its

therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 6:917–935. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kimura H: The physiological role of

hydrogen sulfide and beyond. Nitric Oxide. 41:4–10. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ang SF, Moochhala SM, MacAry PA and Bhatia

M: Hydrogen sulfide and neurogenic inflammation in polymicrobial

sepsis: involvement of substance P and ERK-NF-κB signaling. PLoS

One. 6:e245352011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bentz M, Zaouter C, Shi Q, et al:

Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase prevents lipid

peroxidation in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem.

113:2256–2267. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hu LF, Wong PT, Moore PK and Bian JS:

Hydrogen sulfide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation

by inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in microglia.

J Neurochem. 100:1121–1128. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jeong SO, Pae HO, Oh GS, et al: Hydrogen

sulfide potentiates interleukin-1beta-induced nitric oxide

production via enhancement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase

activation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 345:938–944. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang RX, Ren K and Dubner R:

Osteoarthritis pain mechanisms: basic studies in animal models.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 21:1308–1315. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

de Boer TN, Huisman AM, Polak AA, et al:

The chondroprotective effect of selective COX-2 inhibition in

osteoarthritis: ex vivo evaluation of human cartilage tissue after

in vivo treatment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 17:482–488. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li X, Ellman M, Muddasani P, et al:

Prostaglandin E2 and its cognate EP receptors control human adult

articular cartilage homeostasis and are linked to the

pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 60:513–523.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Distrutti E, Sediari L, Mencarelli A, et

al: Evidence that hydrogen sulfide exerts antinociceptive effects

in the gastrointestinal tract by activating KATP channels. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 316:325–335. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kawabata A, Ishiki T, Nagasawa K, et al:

Hydrogen sulfide as a novel nociceptive messenger. Pain. 132:74–81.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Rosa SC, Rufino AT, Judas FM, Tenreiro CM,

Lopes MC and Mendes AF: Role of glucose as a modulator of anabolic

and catabolic gene expression in normal and osteoarthritic human

chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 112:2813–2824. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vacek TP, Qipshidze N and Tyagi SC:

Hydrogen sulfide and sodium nitroprusside compete to

activate/deactivate MMPs in bone tissue homogenates. Vasc Health

Risk Manag. 9:117–123. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shakibaei M, Csaki C, Nebrich S and

Mobasheri A: Resveratrol suppresses interleukin-1beta-induced

inflammatory signaling and apoptosis in human articular

chondrocytes: potential for use as a novel nutraceutical for the

treatment of osteoarthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 76:1426–1439. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ding QH, Cheng Y, Chen WP, Zhong HM and

Wang XH: Celastrol, an inhibitor of heat shock protein 90β potently

suppresses the expression of matrix metalloproteinases, inducible

nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in primary human

osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 708:1–7. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Perry MM, Hui CK, Whiteman M, et al:

Hydrogen sulfide inhibits proliferation and release of IL-8 from

human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

45:746–752. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kloesch B, Liszt M, Steiner G and Broll J:

Inhibitors of p38 and ERK1/2 MAPkinase and hydrogen sulphide block

constitutive and IL-1β-induced IL-6 and IL-8 expression in the

human chondrocyte cell line C-28/I2. Rheumatol Int. 32:729–736.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang H, Moochhala SM and Bhatia M:

Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulates inflammatory response by

activating the ERK pathway in polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol.

181:4320–4331. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sieghart D, Kiener HP, Kloesch B and

Steiner G: A9.3 Hydrogen sulfide and MEK1 inhibition reduce

IL-1beta-induced activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Ann

Rheum Dis. 73:A932014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Oh GS, Pae HO, Lee BS, et al: Hydrogen

sulfide inhibits nitric oxide production and nuclear factor-kappaB

via heme oxygenase-1 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated

with lipopolysaccharide. Free Radic Biol Med. 41:106–119. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|