Introduction

Tumor invasion and metastasis are the main

characteristics of various types of aggressive human cancer,

including breast cancer (1). Cell

invasion is one of the initiation steps for the metastatic cascade,

during which cancer cells migrate through the extracellular matrix

from the primary tumor, which is associated with the upregulated

expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (2–4).

Therefore, it is important to elucidate the mechanisms underlying

cancer invasion.

Histone acetylation status regulated by histone

acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) is

important in the regulation of gene expression by affecting

chromatin structure and accessibility (5,6).

HDACs are recruited to DNA-bound transcription factors resulting in

the removal of acetyl groups from nucleosomal histones or directly

interact with transcription factors to modulate gene expression

(7–10). HDAC inhibition leads to the

accumulation of acetylation in histones and transcription factors,

and specifically programmed gene expression patterns (11,12).

In humans, the reduction of histone acetylation is

significantly associated with tumor progression and invasion

(13). Emerging evidence indicates

that histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) induce growth

inhibition, cell cycle arrest and programmed cell death in diverse

cancer cells (14,15). HDACi treatment upregulates the

expression of suppressors of metastasis and downregulates

invasion-promoting genes, resulting in the repression of cancer

cell invasion and metastasis (16). HDAC inhibition is emerging as a

potential strategy for cancer therapy and several HDACi have been

developed for clinical trials in patients with solid malignancies

(17). Trichostatin A (TSA), a

non-competitive reversible inhibitor of HDAC activity, has been

reported to inhibit cancer invasion and metastasis in vivo

and in vitro (18–20). HDACi modulate cancer progression

through affecting the acetylation of histone and non-histone

proteins to reactivate the transcription of differential target

genes. It has been proposed that TSA upregulates RECK to suppress

MMP2 activation and cancer cell invasion (21). Therefore, it is important to

investigate the targets of HDACi in order to elucidate the

molecular mechanisms underlying HDACi elicited phenotypes.

In the present study, TSA was observed to inhibit

cell invasion in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Furthermore, the

expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 2/3 (TIMP2/3)

was upregulated and the expression of MMP2/9 was decreased by TSA

treatment. Notably, TIMP2/3 and MMP2/9 have been revealed as

targets of TET1 in prostate and breast cancer invasion (22). Additionally, tumor development is

associated with a decrease in TET expression and 5-methylcytosine

hydroxylation (23). TIMP2 and

TET1 consistently demonstrated downregulation during breast cancer

progression in vivo. Our hypothesis was that TET1 may be one

of the targets of HDACi in breast cancer invasion. As expected,

TET1 was upregulated by TSA stimulation and TET1 knockdown

facilitated breast cancer cell invasion. Importantly, TET1

depletion impaired TSA induced suppression of cell invasion,

suggesting that TET1 may act as one of the HDACi targets partially

mediating TSA elicited anti-cancer activity.

Materials and methods

Patient samples and cell culture

The present study was approved by the ethics

committee of Shanghai Tongren Hospital (Shanghai, China), and

written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior

to the study. A total of 61 cancer specimens from breast cancer

patients from stages I to IV were collected and the conditions of

these patients are summarized in Table

I. Samples were individually fresh-frozen in TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All patients

were histologically examined at Shanghai Tongren Hospital

(Shanghai, China) and written informed consent was obtained from

all study participants. Breast cancer MCF-7 cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with

10% fetal calf serum at 37°C and 5% CO2. TSA dissolved

in DMSO was applied in the present study with the indicated

concentrations.

| Table ICharacteristics of breast cancer

patients. |

Table I

Characteristics of breast cancer

patients.

| Age (years) |

|---|

|

|

|---|

| Phase | 40–49 | 50+ |

|---|

| I | 5 | 7 |

| II | 12 | 14 |

| III | 7 | 9 |

| IV | 3 | 4 |

Wound-healing assay

Wound healing was performed as previously described

in 12-well plates (24). Briefly,

after MCF-7 cells grew to >90% confluence, a wound was

introduced using a 200 μl pipette tip. Subsequently, the cells were

washed once with PBS and then incubated at 37°C and 5%

CO2. Wound closure was monitored over an indicated time

period and images were captured at the four intersecting edges of

the cross. Wound width at 0 and 24 or 36 h was measured and the

difference plotted as the percentage of wound closure.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from MCF-7 cells or cancer

tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies). For

each sample, 2.5 or 5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using

the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

The cDNA product was then quantified by SYBR-Green real-time PCR

master mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The primers used were as

follows: TET1, forward 5′-GAGCCTGTTCCTCGATGTGG-3′ and reverse

5′-CAAACCCACCTGAGGCTGTT-3′; GAPDH, forward

5′-GTGTTCCTACCCCCAATGTGT-3′ and reverse

5′-ATTGTCATACCAGGAAATGAGCTT-3′; TIMP2, forward

5′-GGGTCTCGCTGGACATTG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGATGTTCTTCTCCGTGACC-3′;

TIMP3, forward 5′-CATGTGCAGTACATCCATACGG-3′ and reverse

5′-CATCATAGACGCGACCTGTCA-3′; MMP2, forward

5′-AAGGCCAAGTGGTCCGTGTGAA-3′ and reverse

5′-AACAGTGGACATGGCGGTCTCAG-3′; MMP9, forward

5′-CACGTCCACCCCTCAGAGC-3′ and reverse

5′-GCCACTTGTCGGCGATAAGC-3′.

Western blot analysis

MCF-7 cells were lysed with two-fold loading buffer

[20 mM of Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2 mM of EDTA and 1% Triton X-100] and

the supernatant was subjected to western blot analysis, which was

performed as previously described (25). GAPDH was used as the loading

control. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-TET1

(Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:500), anti-MMP2 (Abcam; 1:400), anti-TIMP2

(Abcam; 1:500) and anti-GAPDH (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA;

1:10,000).

shRNA and transfection

Chemically synthesized TET1 shRNA and scramble shRNA

(control) were annealed and cloned into a short interfering RNA

expressing vector named pSUPER (Oligoengine, Seattle, WA, USA).

Control or TET1 shRNA targeted sequences were: control shRNA

5′-GCTACGAAGCACCTCTCTTAG-3′ and TET1 shRNA

5′-CGATGCAAGCCATCCTTTCGA-3′. Plasmids purified by the Qiagen

purification kit were transfected into MCF-7 cells at 40–60%

confluency with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistic analysis

SPSS 11.0 software was used for statistical analysis

in the present study. The values are presented as the mean ± SD and

one-way ANOVA was applied for group differences. All tests were

two-sided and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

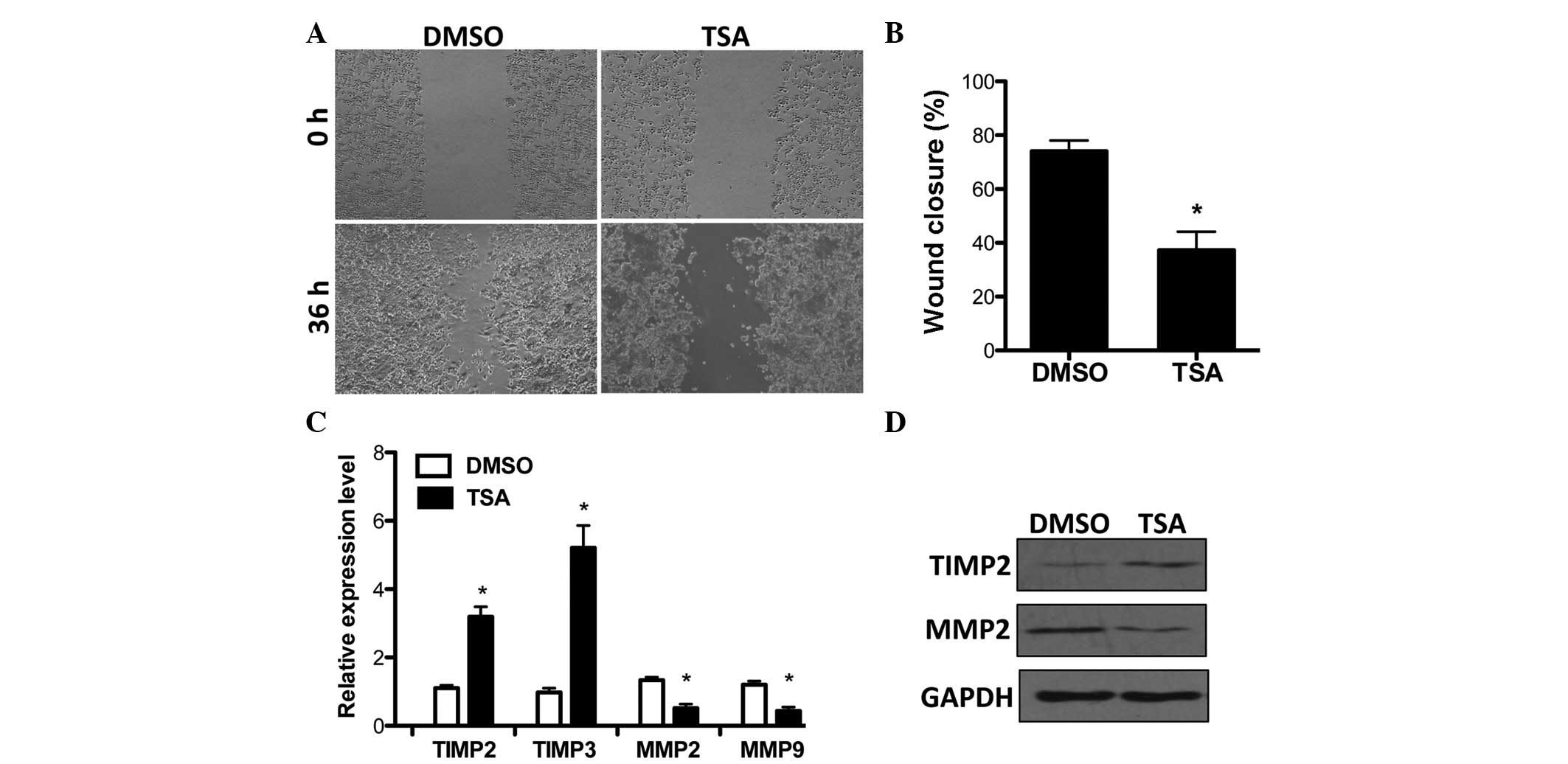

HDACi suppresses breast cancer cell

invasion and regulates TIMP2/3 and MMP2/9 expression

Previously, HDACi were reported to inhibit breast

cancer cell invasion (18,26). Prior to examining the mechanisms of

HDAC in cancer invasion, the effects of TSA on cell invasion were

examined by a wound-healing assay in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Consistent with previous findings, TSA significantly suppressed

cell invasion (Fig. 1A and B).

TIMP2 and 3, the important suppressors of cancer cell invasion

(27,28), were upregulated under the

stimulation of TSA. By contrast, the expression of MMP2/9, which

was correlated with clinicopathological disease variables in breast

cancer (29,30), was increased by HDAC inhibition

(Fig. 1C). Furthermore, TSA

affected MMP2 and TIMP2 expression and this was verified at the

protein level (Fig. 1D). In

addition, MMP2/9 and TIMP2/3 mRNA levels were not affected when TSA

was administered to cells within 2 h (data not shown). This

demonstrates that TIMP2/3 and MMP2/9 expression may be indirectly

modulated by HDAC in breast cancer.

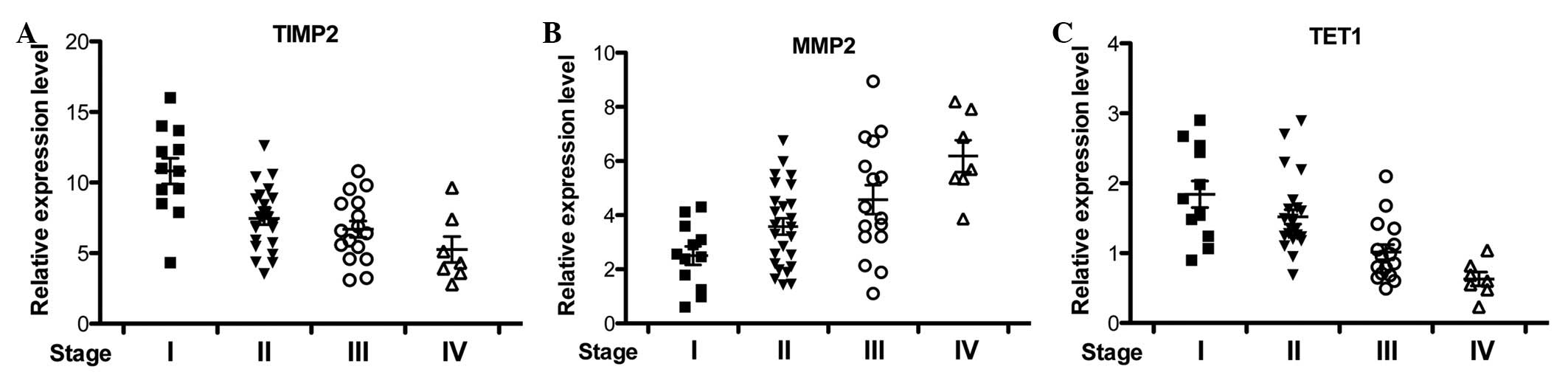

TIMP2, MMP2 and TET1 expression during

breast cancer development

Coincidently, TIMPs and MMPs were revealed as

downstream targets of TET1 and TET1 suppresses invasion partly

through TIMP activation and MMP inhibition in prostate and breast

cancer (22). In order to

investigate the correlation between TIMP2, MMP2 and TET1 in

vivo, the expression of these genes in multiple breast cancer

patients at different stages was examined by qRT-PCR. TIMP2 and

MMP2 expression was progressively downregulated and upregulated

with breast cancer development, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). Consistently, TET1 mRNA

level was reduced in breast cancer tissues (Fig. 2C), which corrrelated with TIMP2

expression changes (23).

Collectively, TIMP2 and TET1 downregulation and MMP2 upregulation

were correlated with breast cancer progression.

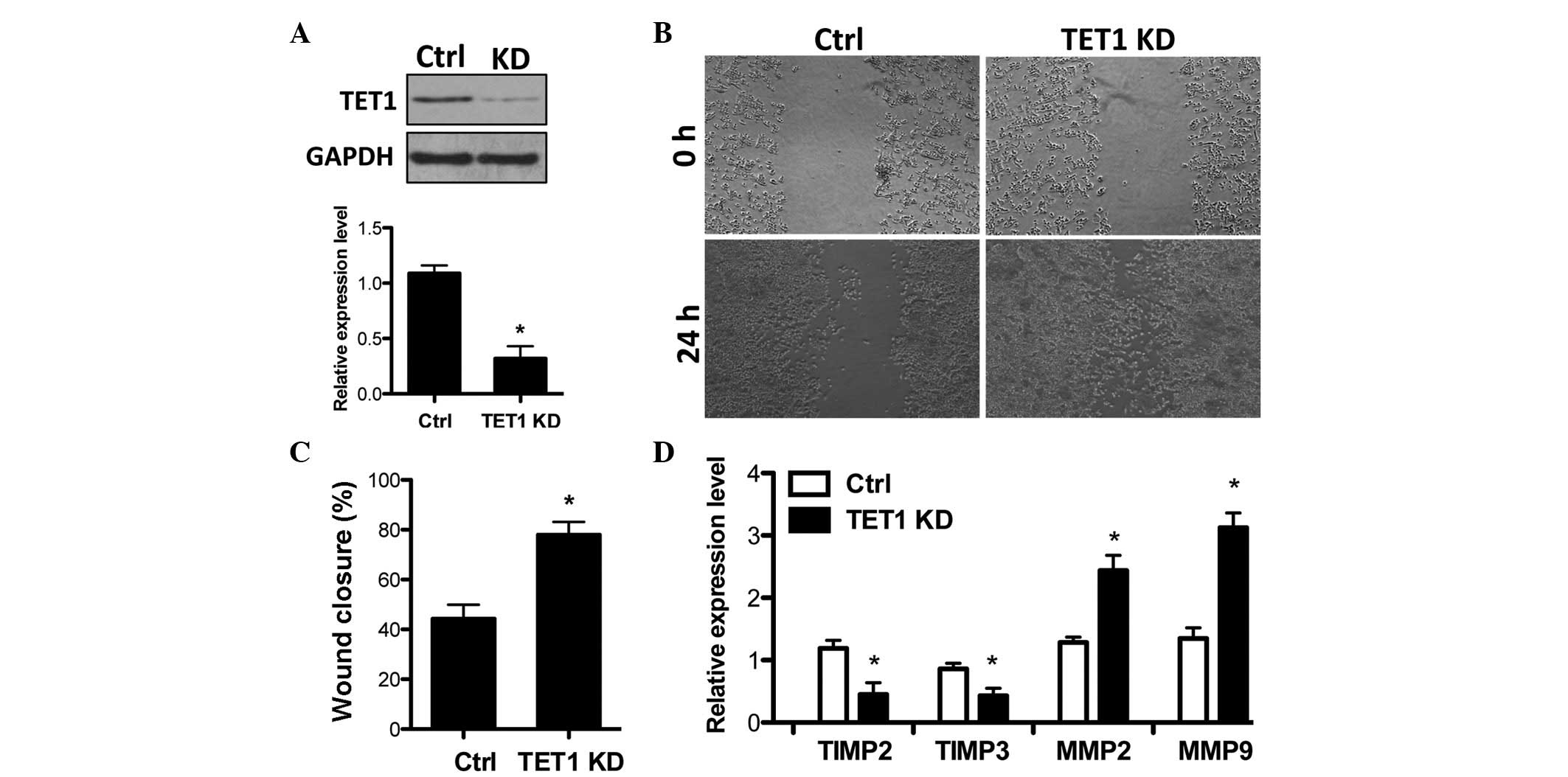

TET1 knockdown facilitates breast cancer

cell invasion

Subsequently, the present study examined whether the

reduction of TET1 is functionally involved in breast cancer cell

invasion. TET1 shRNA was delivered into MCF-7 cells to efficiently

knockdown TET1 expression (Fig.

3A). Then the effects of TET1 knockdown on cell invasion were

analyzed and the results demonstrated that TET1 depletion by TET1

shRNA increased the cell invasion capacity (Fig. 3B and C). Notably, TET1 knockdown

resulted in a decrease in TIMP2/3 and the upregulation of MMP2/9

expression (Fig. 3D), which is

opposite to the effects of TSA in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1A). This indicates that TET1

suppresses breast cancer cell invasion.

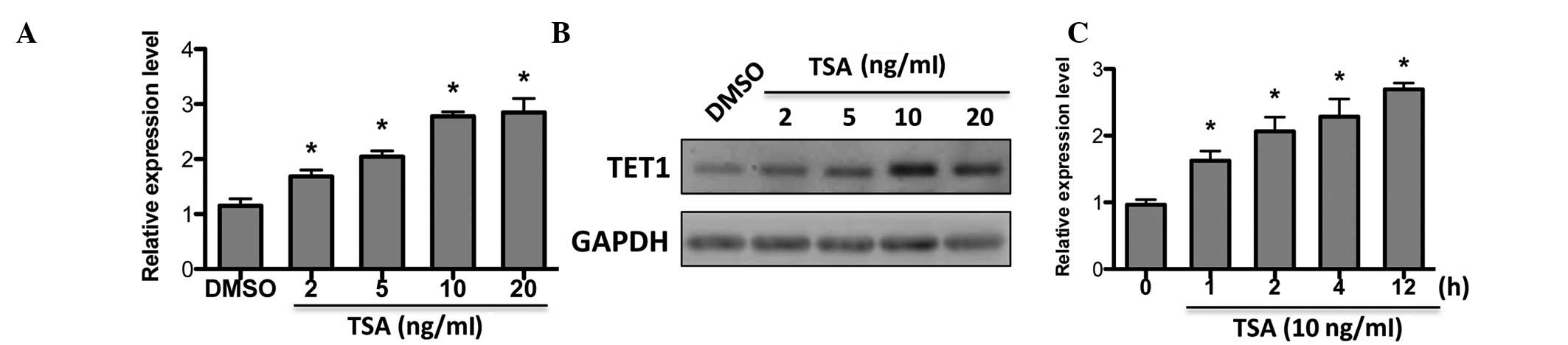

TSA upregulates TET1 expression in MCF-7

cells

Given that the expression of TIMPs and MMPs was

affected by HDAC inhibition and TET1, our hypothesis was that TET1

may be regulated by HDACi. As expected, TET1 expression was

upregulated by TSA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A), which was confirmed by western

blot analysis (Fig. 4B).

Additionally, TET1 was responsive to short-term TSA treatment

(Fig. 4C). This suggests that TET1

may be a target of TSA in breast cancer.

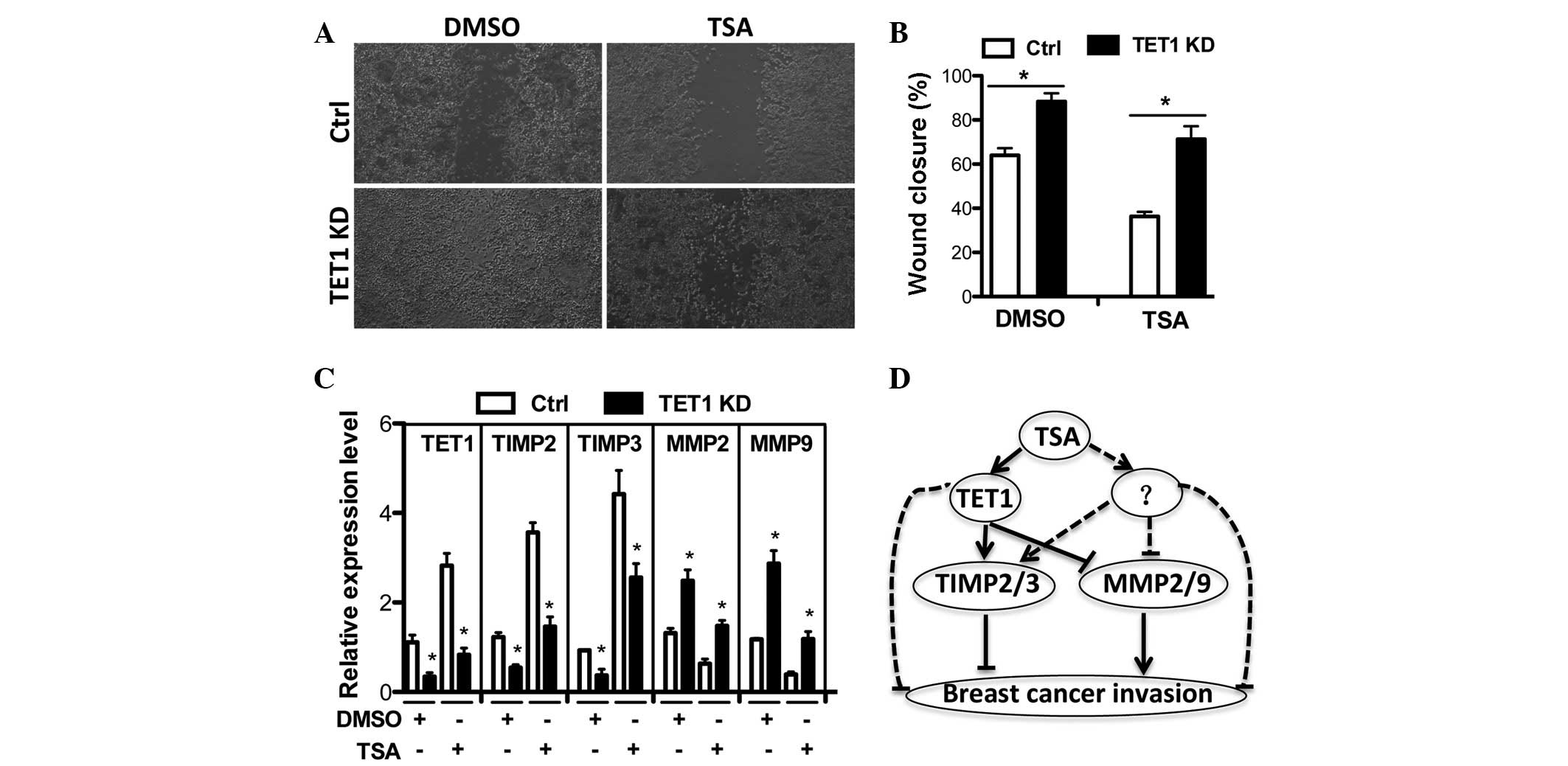

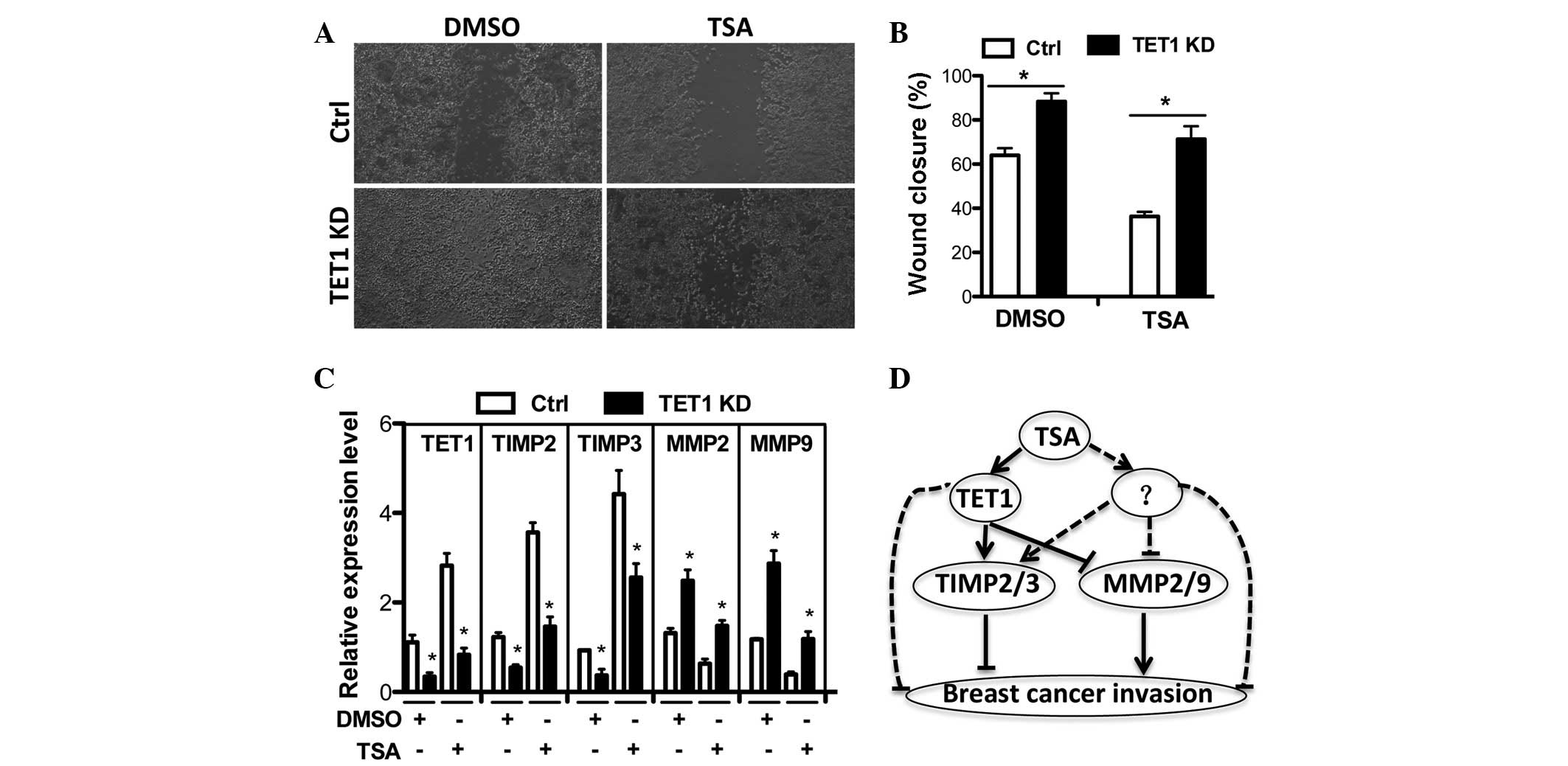

TET1 knockdown impairs TSA-induced

suppression of breast cancer cell invasion

Since TET1 expression was found to be regulated by

HDAC inhibition, the functional association between TSA and TET1

needed to be elucidated. In order to examine whether TET1 is able

to mediate TSA induced suppression of breast cancer cells, TSA was

subjected to TET1-knockdown and cell invasion was examined. It was

revealed that the inhibitory effect of TSA on breast cancer cell

invasion was impaired in TET1-knockdown cells when compared with

control shRNA expressing cells (Fig.

5A and B). Correspondingly, TSA upregulated TIMP2/3 and

downregulated MMP2/9 expression, which were also impaired in

TET1-knockdown cells. This indicates that TET1 partially mediates

TSA induced repression of breast cancer cell invasion.

| Figure 5TET1 partially mediates TSA-induced

suppression of breast cancer cell invasion. (A–B) Ctrl or TET1 KD

expressing MCF-7 cells were treated with DMSO or 10 ng/ml of TSA

for 36 h after wounding. (A) Wound closure was monitored and (B)

quantified. (C) Expression levels of TET1, TIMP2, TIMP3, MMP2 and

MMP9 were measured by qRT-PCR in Ctrl or TET1 KD MCF-7 cells under

the condition in (A). (D) Hypothetical model for the action

mechanism of TSA in the suppression of breast cancer cell invasion.

Briefly, TSA regulates TET1 expression or other unknown factors to

promote TIMP2/3 expression and inhibit MMP2/9 transcription leading

to the suppression of breast cancer cell invasion.

*P<0.05 vs. CTRL. TSA, trichostatin A; Ctrl, control

shRNA; KD, knockdown shRNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR;

TIMP, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase; MMP, matrix

metalloproteinase. |

Discussion

Breast cancer is one of the most common types of

cancer and has a high risk of mortality among females all over the

world (31). Therefore there is a

great need for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying

cancer progression and for the development of more effective

therapeutic strategies for breast cancer. Carcinogenesis is able to

be regulated by genetic and epigenetic alterations and epigenetic

alterations are a reversible process, which makes epigenetic

modifications preferable for clinical therapy (32,33).

DNA methylation and histone modifications are the

most important epigenetic mediators of transcriptional regulation

and multiple HDACi are in clinical development for hematological

and solid tumor treatment (34,35).

HDACi result in the accumulation of acetylation in histones and

non-histone proteins to modulate target gene expression in

cancerous cells, which reactivates the expression of tumor

suppressors (35). In the present

study (Fig. 1) and previous

studies (18,36), the non-competitive reversible HDACi

TSA has been demonstrated to suppress breast cancer cell invasion.

The limitations of HDAC inhibition in cancer therapy is the

non-specificity and toxicity of the chemical inhibitors. It is

important to understand the molecular mechanisms in HDACi

treatment. The HDACi valproic acid (VPA) induces ERα expression in

its anti-tumor effects (37) and

TSA enhances the acetylation and stability of the ERα and p300

proteins that may contribute to breast cancer treatment (38). TSA also directly upregulates p53

and RECK, which are important in tumor suppression (21,39).

The present study found that TIMP2/3 were increased

and that MMP2/9 were decreased when treated with TSA (Fig. 1). It has been proposed that TET1

suppresses breast cancer invasion through the activation of TIMPs

and the inhibition of MMPs (22).

Additionally, TET1 and TIMP2/3 reduction was inversely correlated

with MMP2/9 upregulation during breast cancer progression (Fig. 2) (23). Notably, TET1 demonstrated similar

functions in MCF-7 breast cancer cell invasion (Fig. 3) (22). It is reasonable to postulate that

TSA may inhibit breast cancer invasion through the regulation of

TET1 expression. Notably, TSA promoted TET1 expression in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4) and

TET1 partially mediated TSA elicited suppression of cell invasion

(Fig. 5), which was in accordance

with our hypothesis. TET1 expression may be negatively controlled

by a specific HDAC and TSA treatment releases the HDAC inhibition

on TET1 expression. TET1 was found to be associated with TIMPs

genes and promoter regions to regulate their DNA methylation status

and transcription levels (22,40).

Our hypothesis is that TSA may indirectly affect 5-methylcytosine

hydroxylation of TIMP gene promoters through the regulation of TET1

expression, which will be investigated in our future study. There

is a possibility that VPA enhances the global 5-methylcytosine

level in nuclear DNA (41).

Furthermore, the alteration in DNA methylation

status is another important epigenetic modification and DNA

methyltransferases (DNMTs) have become an epigenetic therapy target

in various types of cancer (42).

5-azacytidine, a global DNMT inhibitor, has been approved for

clinical trials against solid tumors (43). Currently, synergistic treatment

with DNMT and HDACi has been applied for producing optimal effects

(41).

As summarized in Fig.

5D, the HDACi TSA may upregulate the expression of TET1, which

results in the activation of TIMPs and the inhibition of MMPs,

thus, leading to the suppression of breast cancer cell invasion.

The present study provides a novel molecular mechanism for HDAC

inhibition in tumor suppression. This may provide insights into the

role of HDACs in cancer development and epigenetic therapy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shanghai Xuhai Biological

Technology Co., Ltd for the experimental support.

References

|

1

|

Steeg PS: Metastasis suppressors alter the

signal transduction of cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:55–63. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mohanam S, Sawaya R, McCutcheon I,

Ali-Osman F, Boyd D and Rao JS: Modulation of in vitro invasion of

human glioblastoma cells by urokinase-type plasminogen activator

receptor antibody. Cancer Res. 53:4143–4147. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rao JS: Molecular mechanisms of glioma

invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:489–501.

2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Davies B, Waxman J, Wasan H, Abel P,

Williams G, Krausz T, Neal D, Thomas D, Hanby A and Balkwill F:

Levels of matrix metalloproteases in bladder cancer correlate with

tumor grade and invasion. Cancer Res. 53:5365–5369. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Horikoshi M: Histone acetylation: from

code to web and router via intrinsically disordered regions. Curr

Pharm Des. 19:5019–5042. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gräff J and Tsai LH: Histone acetylation:

molecular mnemonics on the chromatin. Nat Rev Neurosci. 14:97–111.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mayo MW, Denlinger CE, Broad RM, Yeung F,

Reilly ET, Shi Y and Jones DR: Ineffectiveness of histone

deacetylase inhibitors to induce apoptosis involves the

transcriptional activation of NF-kappa B through the Akt pathway. J

Biol Chem. 278:18980–18989. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Brochier C, Dennis G, Rivieccio MA,

McLaughlin K, Coppola G, Ratan RR and Langley B: Specific

acetylation of p53 by HDAC inhibition prevents DNA damage-induced

apoptosis in neurons. J Neurosci. 33:8621–8632. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sachweh MC, Drummond CJ, Higgins M,

Campbell J and Laín S: Incompatible effects of p53 and HDAC

inhibition on p21 expression and cell cycle progression. Cell Death

Dis. 4:e5332013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cheung WL, Briggs SD and Allis CD:

Acetylation and chromosomal functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol.

12:326–333. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Van Lint C, Emiliani S and Verdin E: The

expression of a small fraction of cellular genes is changed in

response to histone hyperacetylation. Gene Expr. 5:245–253.

1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ,

et al: Transcriptional signature of histone deacetylase inhibition

in multiple myeloma: biological and clinical implications. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:540–545. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Song J, Noh JH, Lee JH, et al: Increased

expression of histone deacetylase 2 is found in human gastric

cancer. APMIS. 113:264–268. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shao Y, Gao Z, Marks PA and Jiang X:

Apoptotic and autophagic cell death induced by histone deacetylase

inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:18030–18035. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Marks PA, Richon VM, Miller T and Kelly

WK: Histone deacetylase inhibitors. Adv Cancer Res. 91:137–168.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

McGarry LC, Winnie JN and Ozanne BW:

Invasion of v-Fos(FBR)-transformed cells is dependent upon histone

deacetylase activity and suppression of histone deacetylase

regulated genes. Oncogene. 23:5284–5292. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Marks PA, Richon VM, Kelly WK, Chiao JH

and Miller T: Histone deacetylase inhibitors: development as cancer

therapy. Novartis Found Symp. 259:269–281. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Vigushin DM, Ali S, Pace PE, et al:

Trichostatin A is a histone deacetylase inhibitor with potent

antitumor activity against breast cancer in vivo. Clin Cancer Res.

7:971–976. 2001.

|

|

19

|

Tarasenko N, Nudelman A, Tarasenko I, et

al: Histone deacetylase inhibitors: the anticancer, antimetastatic

and antiangiogenic activities of AN-7 are superior to those of the

clinically tested AN-9 (Pivanex). Clin Exp Metastasis. 25:703–716.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bolden JE, Peart MJ and Johnstone RW:

Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev

Drug Discov. 5:769–784. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu LT, Chang HC, Chiang LC and Hung WC:

Histone deacetylase inhibitor up-regulates RECK to inhibit MMP-2

activation and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res. 63:3069–3072.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hsu CH, Peng KL, Kang ML, et al: TET1

suppresses cancer invasion by activating the tissue inhibitors of

metalloproteinases. Cell Rep. 2:568–579. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang H, Liu Y, Bai F, et al: Tumor

development is associated with decrease of TET gene expression and

5-methylcytosine hydroxylation. Oncogene. 32:663–669. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Asrani K, Keri RA, Galisteo R, et al: The

HER2- and heregulin beta1 (HRG)-inducible TNFR superfamily member

Fn14 promotes HRG-driven breast cancer cell migration, invasion,

and MMP9 expression. Mol Cancer Res. 11:393–404. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Brown SA, Ghosh A and Winkles JA:

Full-length, membrane-anchored TWEAK can function as a juxtacrine

signaling molecule and activate the NF-kappaB pathway. J Biol Chem.

285:17432–17441. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Grimaldi C, Pisanti S, Laezza C, et al:

Anandamide inhibits adhesion and migration of breast cancer cells.

Exp Cell Res. 312:363–373. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Albini A, Melchiori A, Santi L, Liotta LA,

Brown PD and Stetler-Stevenson WG: Tumor cell invasion inhibited by

TIMP-2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 83:775–779. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Baker AH, George SJ, Zaltsman AB, Murphy G

and Newby AC: Inhibition of invasion and induction of apoptotic

cell death of cancer cell lines by overexpression of TIMP-3. Br J

Cancer. 79:1347–1355. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jinga D, Stefanescu M, Blidaru A, Condrea

I, Pistol G and Matache C: Serum levels of matrix

metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 and their tissue natural

inhibitors in breast tumors. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol.

63:141–158. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sier CF, Kubben FJ, Ganesh S, et al:

Tissue levels of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 are

related to the overall survival of patients with gastric carcinoma.

Br J Cancer. 74:413–417. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al: Cancer

statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 58:71–96. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Taby R and Issa JP: Cancer epigenetics. CA

Cancer J Clin. 60:376–392. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cai FF, Kohler C, Zhang B, Wang MH, Chen

WJ and Zhong XY: Epigenetic therapy for breast cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 12:4465–4487. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Namdar M, Perez G, Ngo L and Marks PA:

Selective inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) induces DNA

damage and sensitizes transformed cells to anticancer agents. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:20003–20008. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu T, Kuljaca S, Tee A and Marshall GM:

Histone deacetylase inhibitors: multifunctional anticancer agents.

Cancer Treat Rev. 32:157–165. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yang X, Phillips DL, Ferguson AT, Nelson

WG, Herman JG and Davidson NE: Synergistic activation of functional

estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha by DNA methyltransferase and histone

deacetylase inhibition in human ER-alpha-negative breast cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 61:7025–7029. 2001.

|

|

37

|

Travaglini L, Vian L, Billi M, Grignani F

and Nervi C: Epigenetic reprogramming of breast cancer cells by

valproic acid occurs regardless of estrogen receptor status. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 41:225–234. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim SH, Kang HJ, Na H and Lee MO:

Trichostatin A enhances acetylation as well as protein stability of

ERalpha through induction of p300 protein. Breast Cancer Res.

12:R222010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Henderson C, Mizzau M, Paroni G, Maestro

R, Schneider C and Brancolini C: Role of caspases, Bid, and p53 in

the apoptotic response triggered by histone deacetylase inhibitors

trichostatin-A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). J

Biol Chem. 278:12579–12589. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, et

al: TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA

methylation fidelity. Nature. 473:343–348. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kristensen LS, Nielsen HM and Hansen LL:

Epigenetics and cancer treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 625:131–142.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hatziapostolou M and Iliopoulos D:

Epigenetic aberrations during oncogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci.

68:1681–1702. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chik F and Szyf M: Effects of specific

DNMT gene depletion on cancer cell transformation and breast cancer

cell invasion; toward selective DNMT inhibitors. Carcinogenesis.

32:224–232. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|