Introduction

Diseases resulting from the degeneration of the

intervertebral discs have become increasing threats to quality of

life due to a rapidly aging society (1). The abnormal apoptosis or

age-associated apoptosis of nucleus pulposus (NP) cells is

suggested to serve a key role in the development of degenerative

disc diseases (2–4). High levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β)

are present in degenerating intervertebral discs and there is a

positive response of intervertebral disc cells to IL-1β inhibition

(5,6). This indicates that the inflammatory

process, in particular the IL-1β-induced degradation of

proteoglycans and type II collagen, results in damage to and

accelerates the apoptosis of NP cells and annulus fibrosus cells,

thereby leading to the development of degenerative disc diseases

(5,7–10).

Reducing inflammation and the deleterious impact of apoptosis is

therefore critical for the treatment of degenerative disc

diseases.

Due to their numerous advantages, including their

abundance, high activity, low immunogenicity, marked proliferation,

differentiation potential and nutrient secretion, mesenchymal stem

cells (MSCs) have been widely used in general transplantation

research, with positive effects (11–13).

MSC transplantation, which exhibits beneficial effects in the

treatment of degenerative disc diseases, including the inhibition

of intervertebral disc degeneration (IVDD), has been reported to

increase the number of cells in intervertebral discs and results in

the partial recovery of intervertebral disc height (14–16).

However, the specific effects and mechanisms of MSCs on NP cells

remain to be fully elucidated. Although certain previous studies

have used green fluorescent protein (GFP)-transfected cells as a

means of distinguishing between cell types, it remains challenging

to accurately separate transfected cells when assessing

intercellular interactions (17).

The complication of in vivo studies is whether the observed

therapeutic effect arises from in situ cells being

'nourished' by BMSCs (12,18,19),

or is instead an artifact of BMSCs, which exhibit high activity and

differentiation potential (13).

In vivo studies are therefore, inherently limited. In order

to further investigate the mechanisms underlying MSC therapy at the

cellular level, the present study used a Transwell assay involving

non-contacting and contacting co-culture systems to simulate the

in vivo paracrine interactions between cells and directed

migration (20,21). Unlike previous studies, the

anti-apoptotic and migratory capabilities, in addition to

mitochondrial transfer through tunneling nanotube (TnT) formation

of BMSCs were directly assessed in vitro. The present study

was able to measure specific alterations in NP cells via paracrine

mechanisms and mitochondrial transfer resulting from MSCs.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The male Sprague-Dawley rats (age, 3 months; weight,

250–300 g) used in the current study were provided by the Second

Military Medical University Laboratory Animal Center (Shanghai,

China). The rats were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle at

constant temperature (25°C) and humidity, with ad libitum

access to food and water. All experiments were approved by the

Animal Ethical Committee of the Second Military Medical University

(no. 13071002114).

Isolation and culture of BMSCs and NP

cells from Sprague-Dawley rats

Primary BMSCs were isolated and cultured, as

described previously (16). The

harvested cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C and

then resuspended in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

(DMEM)/F-12 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/ml

streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin (all purchased from Gibco Life

Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells at passage 3 were subjected

to flow cytometric analysis (Cytomics FC500; Beckman Coulter, Brea,

CA, USA) to assess the expression of the surface markers, cluster

of differentiation 29 (CD29), CD90, CD31 and CD45. The osteogenic

and adipogenic differentiation potentials of the cells were also

assessed by Alizarin red staining (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Haimen, China) and Oil Red O staining (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology).

The rat NP cells were isolated, as described

previously (22). The NP cells

were seeded into 60 mm tissue culture dishes and grown in complete

culture medium at 37°C with 5% CO2. The culture medium

was replaced every 2–3 days. The cells were passaged by digestion

with 0.25% trypsin (Gibco Life Technologies) once they reached

80–90% confluence. The NP cells at passage 3 in culture medium were

used for subsequent experiments.

Establishment of a co-culture system and

cell treatment

In order to construct the co-culture system, NP

cells were plated at a constant density of 2×104

cells/cm2 into certain culture plates and were

subsequently divided into different groups based on specific

treatments. Two steps were included and each lasted 24 h. In the

first step, serum-free medium with or without IL-1β (PeproTech,

Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was used for stimulation and

subsequently, complete medium with or without BMSCs (the ratio was

1:2 to the NP cells) was used for co-culture intervention. The

groups used were as follows: i) Control group, the cells were

treated with serum-free medium, which was then replaced with

complete medium; ii) No-culture group, the cells were subjected to

intervention treatment with IL-1β (20 ng/ml), which was then

replaced with complete medium; iii) Indirect co-culture group,

following stimulation with IL-1β (20 ng/ml), the BMSCs were

co-cultured using a Transwell (pore size 0.4 µm; EMD

Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) in complete medium; iv) direct

co-culture group, following stimulation with IL-1β (20 ng/ml), an

identical quanitity of GFP BMSCs were directly added to the NP

cells with complete medium.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The total RNA was isolated from the NP cells using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

and the RNA concentration was measured photometrically (NanoDrop

2000/2000c; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA).

Synthesis of the cDNA was performed using the RevertAid First

Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA,

USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR analysis

was performed using gene-specific primers (Table I) for GAPDH, a disintegrin and

metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 4 (ADAMTS-4),

ADAMTS-5, matrix metallopro-teinase 13 (MMP-13), tissue inhibitor

of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) and caspase-3 (Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd., Shanghai, China). RT-qPCR was performed using a MyiQ™

Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA)

with SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka,

Japan). Amplification of the target cDNA was normalized against the

expression of GAPDH. The relative levels of the target mRNA

expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method

(23).

| Table IPrimer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

Table I

Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer name | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| GAPDH | GAPDH-F |

CCATCAACGACCCCTTCATT |

| GAPDH-R |

ATTCTCAGCCTTGACTGTGC |

| ADAMTS-4 | ADAMTS-F |

ACAATGGCTATGGACACTGCCTCT |

| ADAMTS-R |

TGTGGACAATGGCTTGAGTCAGGA |

| ADAMTS-5 | ADAMTS-F |

GTCCAAATGCACTTCAGCCACGAT |

| ADAMTS-R |

AATGTCAAGTTGCACTGCTGGGTG |

| MMP-13 | MMP-13-F |

CCCTGGAGCCCTGATGTTT |

| MMP-13-R |

CTCTGGTGTTTTGGGGTGCT |

| TIMP-1 | TIMP-F |

ATAGTGCTGGCTGTGGGGTGTG |

| TIMP-R |

TGATCGCTCTGGTAGCCCTTCTC |

| Caspase-3 | Caspase-3-F |

ACAGAGCTGGACTGCGGTAT |

| Caspase-3-R |

TGCGGTAGAGTAAGCATACAGG |

Terminal deoxynucleotide transferase dUTP

nick end labeling (TUNEL) apoptosis analysis

Following fixation in freshly prepared 4%

paraformaldehyde (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) for 1 h at

4°C, the cells were incubated with 3% H2O2

and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min and washed three times with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at each step. The cells were

stained using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche

Diagnostics) and counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Apoptotic alterations were measured by fluorescence

microscopy (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Caspase-3 activity assay

Caspase-3 activity was determined using a Caspase-3

Activity kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), which is based

on the caspase-3-mediated conversion of acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp

p-nitroanilide into the yellow formazan product, p-nitroaniline,

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The activity of

caspase-3 was quantified on a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek

Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) at 405 nm. Caspase-3 activity

was expressed as the fold-change in enzyme activity compared with

that of synchronized cells.

Detection of apoptotic incidence by flow

cytometry

Apoptotic incidence was detected using the Annexin

V-Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) [Phycoerythrin (PE) for direct

co-culture]/propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection kit I (BD

Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The samples were analyzed on a fluorescence activated

cell sorter (Cytomics FC500; Beckman Coulter) within 1 h. Apoptotic

cells, including annexin-positive/PI-negative in addition to

double-positive cells, were counted and represented as a percentage

of the total cell count.

Detection of migration of BMSCs

The migratory ability of BMSCs was assessed using

Transwell plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), which were 6.5

mm in diameter with 8 µm pore filters. The BMSCs were

harvested and equal numbers of cells were added to each group of

Transwell plates. Following incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the cells

that had not migrated from the upper side of the filter were

scraped off with a cotton swab and the filters were stained with

Coomassie Blue (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The number of

cells that had migrated to the lower side of the filter were

counted under a light microscope at a magnification of ×400 in five

randomly selected fields.

Staining cells and confocal

microscopy

To trace inter-cellular exchange of mitochondria,

GFP BMSCs were separately labeled with MitoTracker® Deep

Red (Invitrogen Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Briefly, the cells were resuspended in pre-warmed

(37°C) staining solution, containing the MitoTracker®

probe (50 nM) for 30 min in complete medium. Following staining,

the cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in fresh

pre-warmed medium and were directly added into IL-1β stimulated NP

cells on glass slides for 24 h. Following the addition of the

cells, the glass slides with two types of cells were washed with

PBS and were labeled with DAPI (10 µg/ml, 5 min; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Images were captured by confocal

microscopy (TCS SP5; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) for

1 h and were subsequently analyzed by Leica LAS AF Lite_2.5.0_7266

software.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in

triplicate. All data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Differences between the groups were analyzed by one way analysis of

variance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01) using

GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La

Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Identification of isolated BMSCs

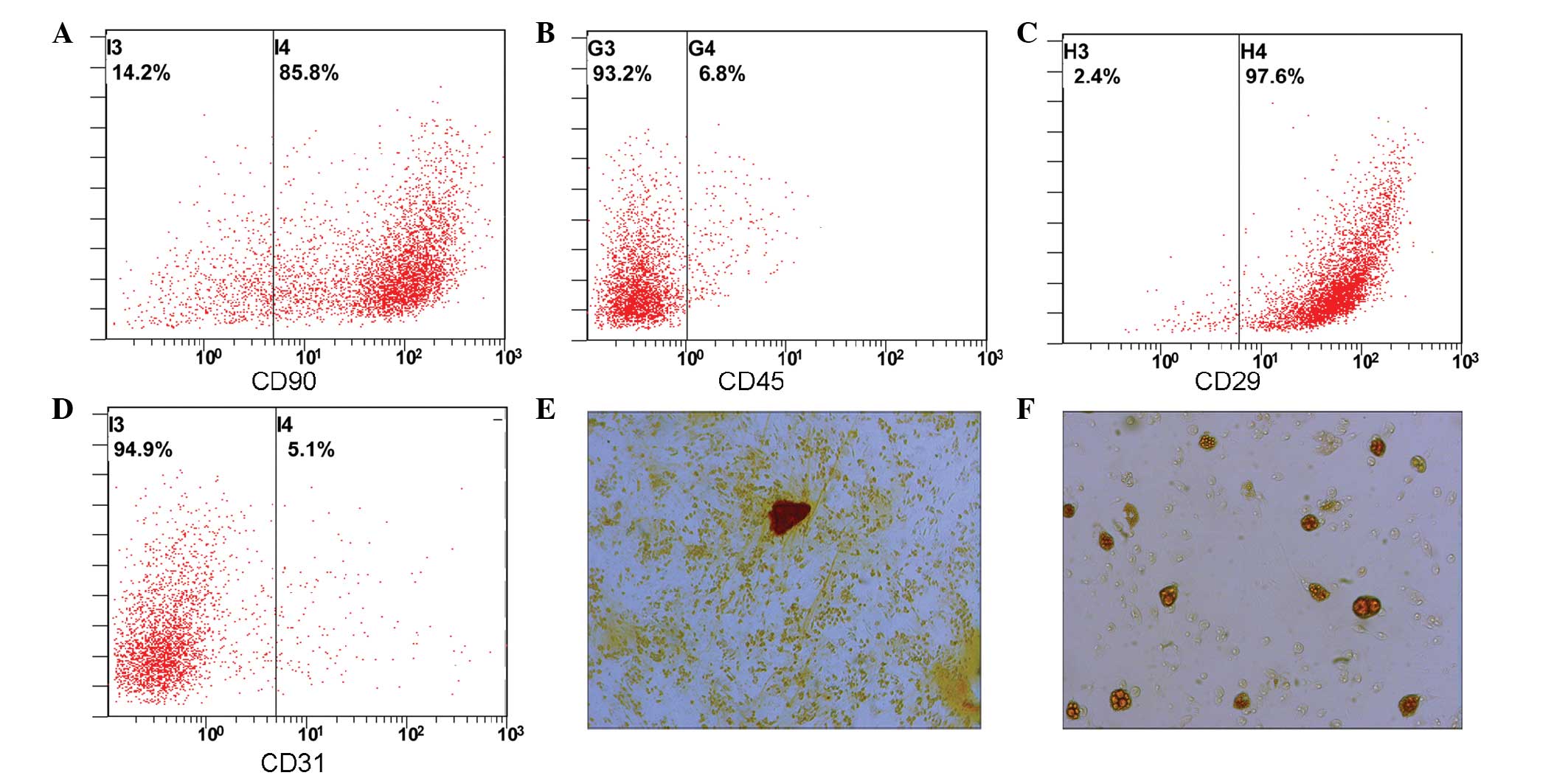

Flow cytometric analysis was used to detect CD90

(Fig. 1A), CD45 (Fig. 1B), CD29 (Fig. 1C) and CD90 (Fig. 1D) expression. BMSCs (>85%) were

positive for CD31 and CD45, whereas <0.1% of BMSCs were positive

for CD31 and CD45. Following 2 weeks of induced differentiation,

osteogenic differentiation was examined by Alizarin red staining

(Fig. 1E), and adipogenic

differentiation was assessed by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 1F). The results suggest that cells

cultured in this manner can be induced to differntiate into both

osteogenic and adipogenic cells.

Co-culture of BMSCs with IL-1β-stimulated

NP cells reduces degenerative enzyme gene expression

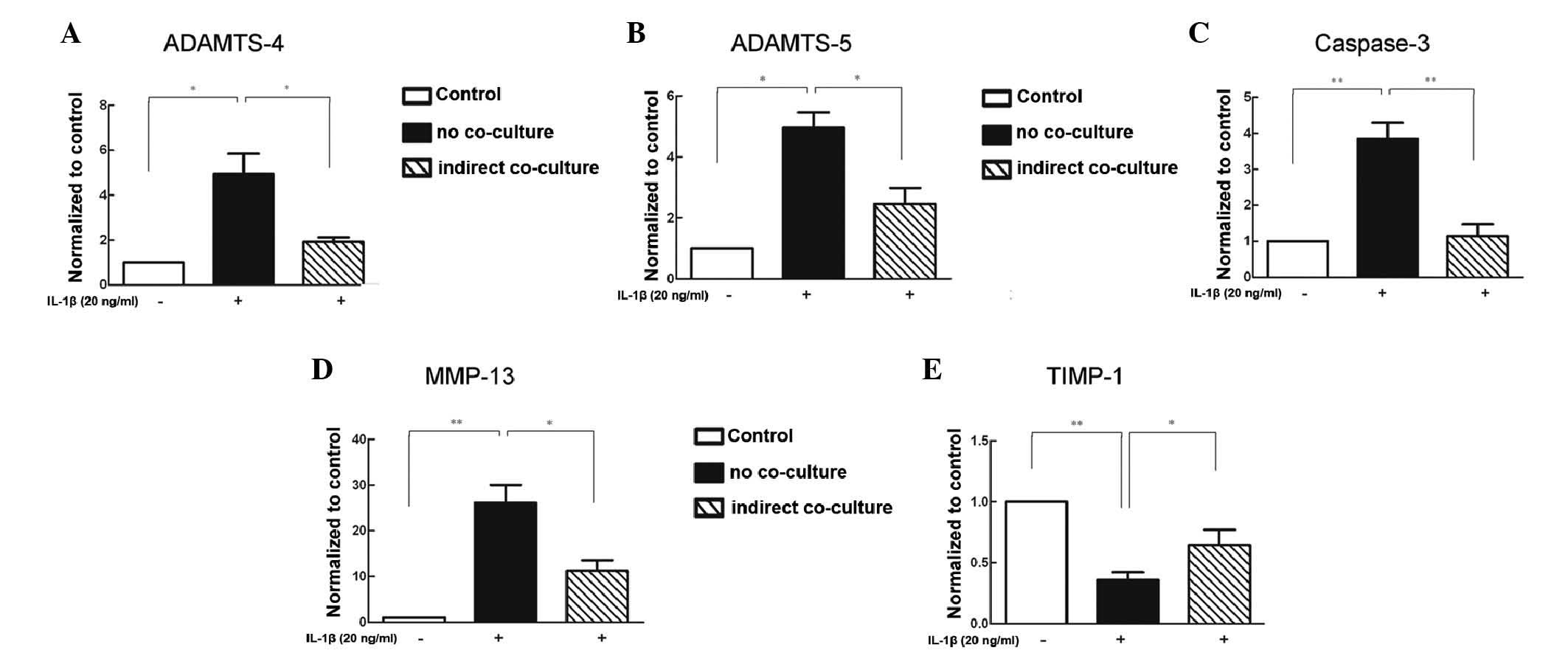

Compared with the unstimulated NP cells, the NP

cells in the no co-culture groups exhibited markedly higher

expression levels of ADAMTS-4, ADAMTS-5, caspase-3 and MMP-13

following inflammatory stimulation (Fig. 2A–D), whereas the expression of

TIMP-1 was reduced (Fig. 2E).

Compared with the no co-culture group, various indexes were

significantly reduced in the co-culture group. In addition, the

expression of TIMP-1 was increased.

Co-culture of BMSCs with IL-1β-stimulated

NP cells reduces the number of TUNEL-stained cells

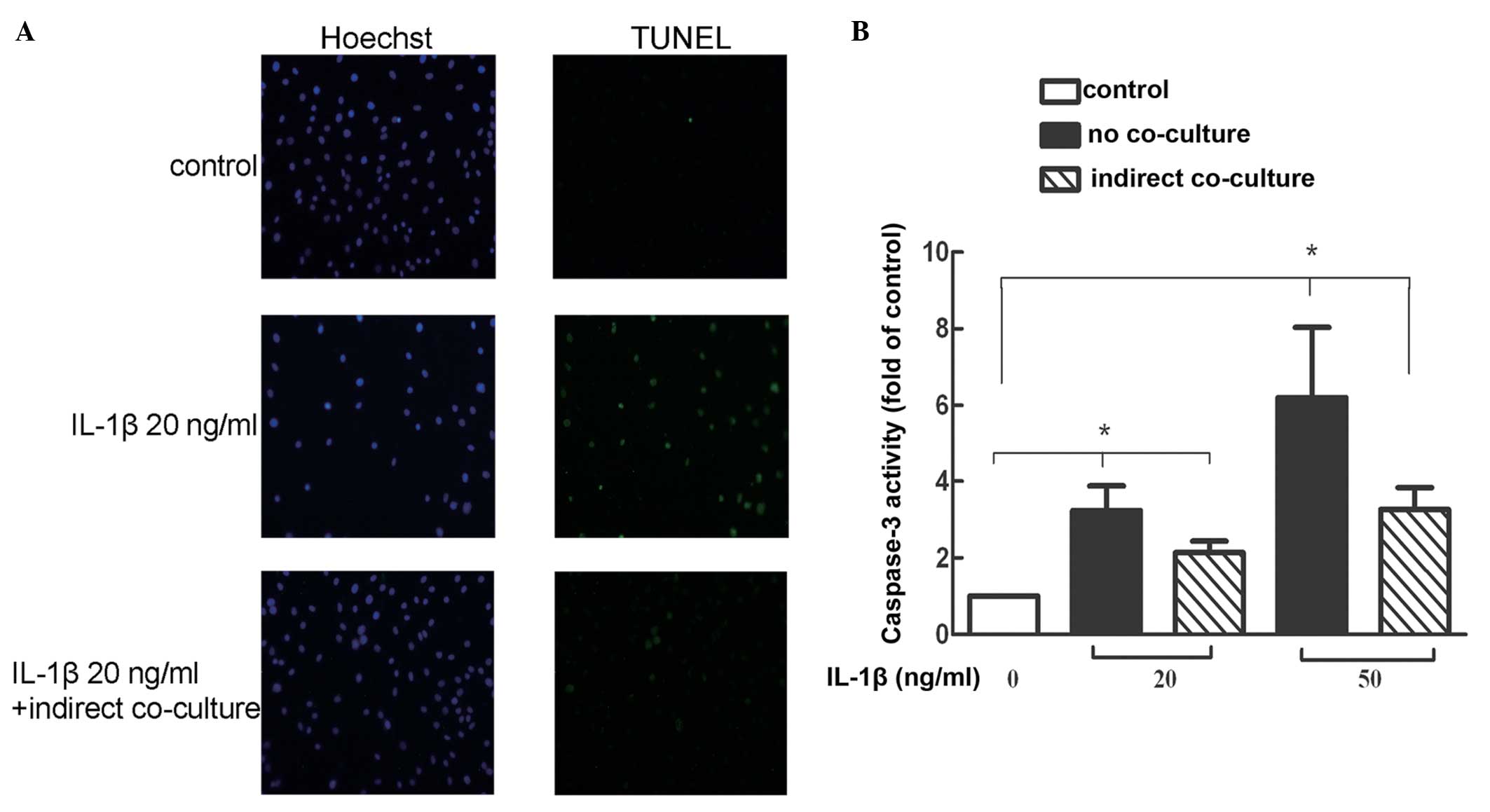

TUNEL staining allows for the detection and

quantification of apoptosis at the cellular level. The number of

TUNEL-positive cells increased with inflammatory factors (20

ng/ml), whereas the number of TUNEL-positive cells was reduced in

the co-culture group (Fig.

3A).

Co-culture of BMSCs with IL-1β-stimulated

NP cells reduces the activity of caspase-3

The results of the caspase-3 activity assay

demonstrated that compared with the normal group, the caspase-3

activities in the 20 and 50 ng/ml inflammatory factor treatment

groups were significantly increased. In each indirect co-culture

group, the caspase-3 activity was marginally lower compared with

the no co-culture group (Fig.

3B).

Co-culture of BMSCs with IL-1β-stimulated

NP cells reduces the apoptotic incidence

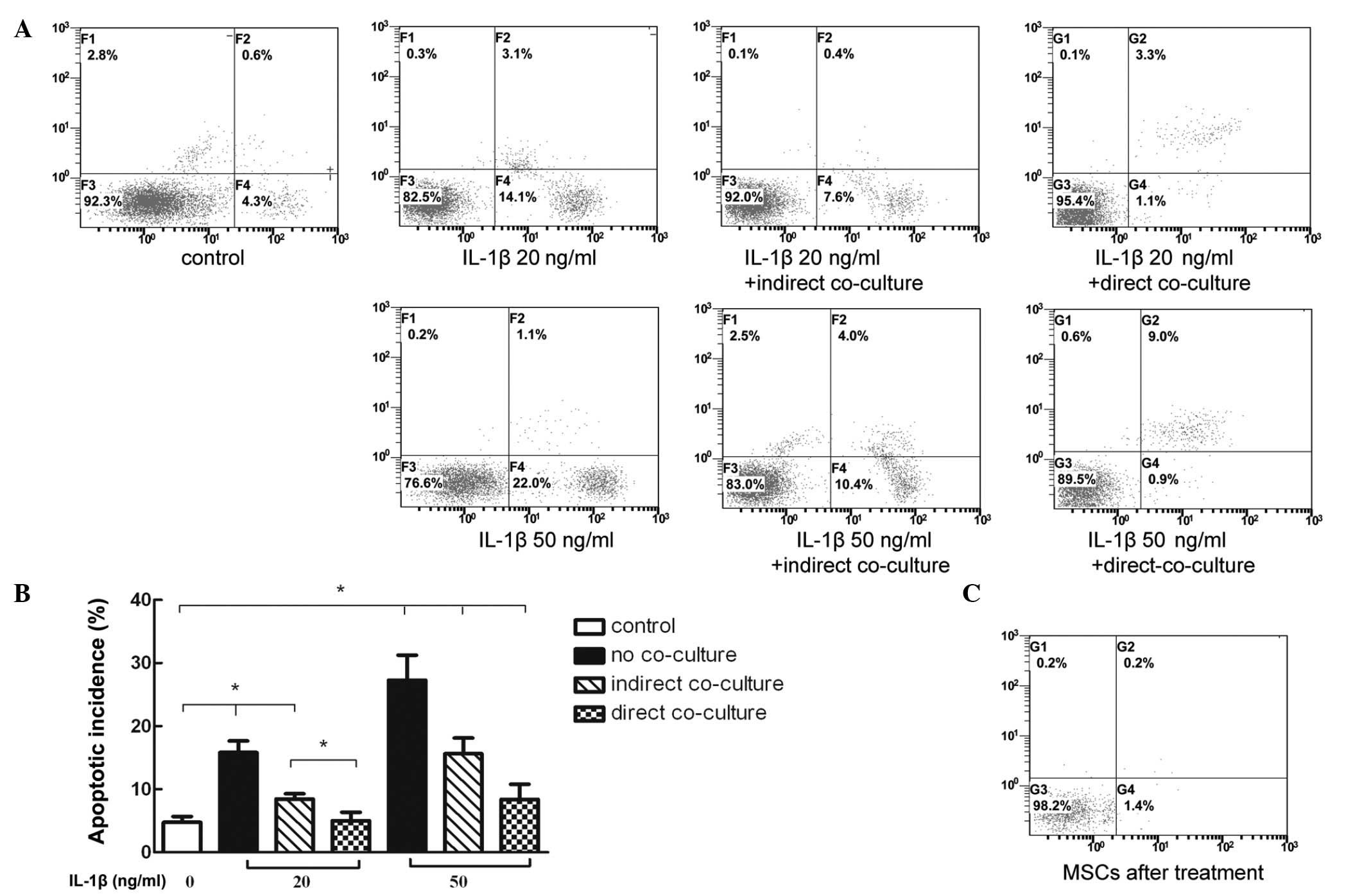

Flow cytometric analysis of annexin V-FITC PE/PI

staining demonstrated that the level of apoptosis was significantly

increased in the NP cells stimulated with inflammatory factors. In

addition, the apoptotic rate increased in line with the increase in

inflammatory factor concentration. These results indicated that

co-culturing NP cells with BMSCs significantly reduced the

apoptotic rate of different levels of IL-1β. This suggested that

direct co-culture may have improved the anti-apoptotic effects

compared with the indirect co-culture (Fig. 4A and B). Notably, the apoptotic

rate of the added BMSCs in the direct co-culture group was markedly

low (Fig. 4C).

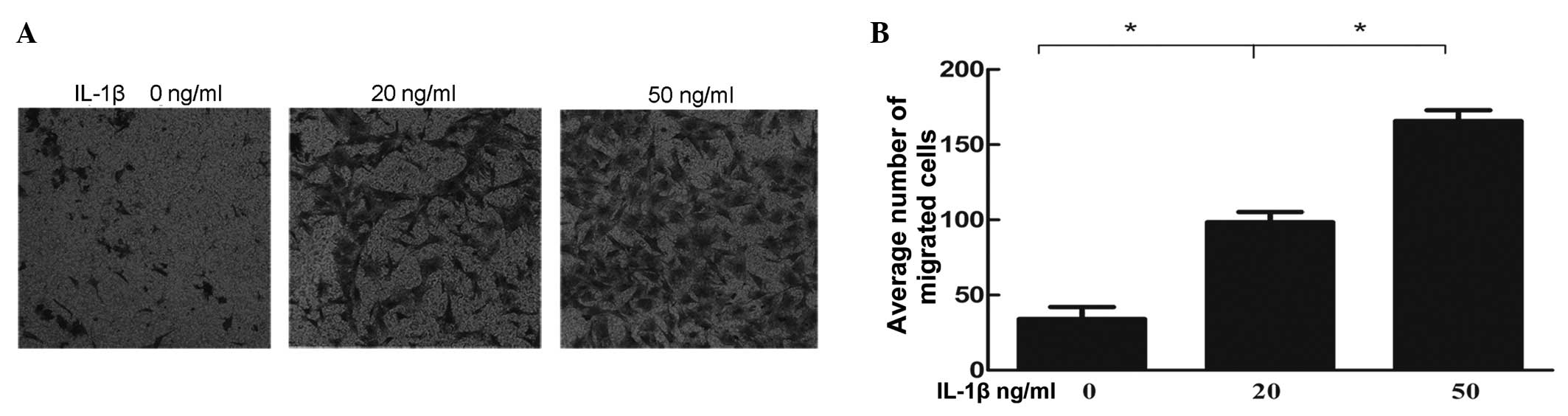

IL-1β stimulation of NP cells increases

the migratory ability of the BMSCs

The number of cells, which migrated through the

pores were counted under 10 random high power fields for each group

(Fig. 5A), which were then

compared (Fig. 5B). Amongst all

the groups, the differences between the negative control and IL-1β

pre-induced groups were statistically significant. Cell damage

resulting from IL-1β enhanced the migratory ability of BMSCs in a

dose-dependent manner.

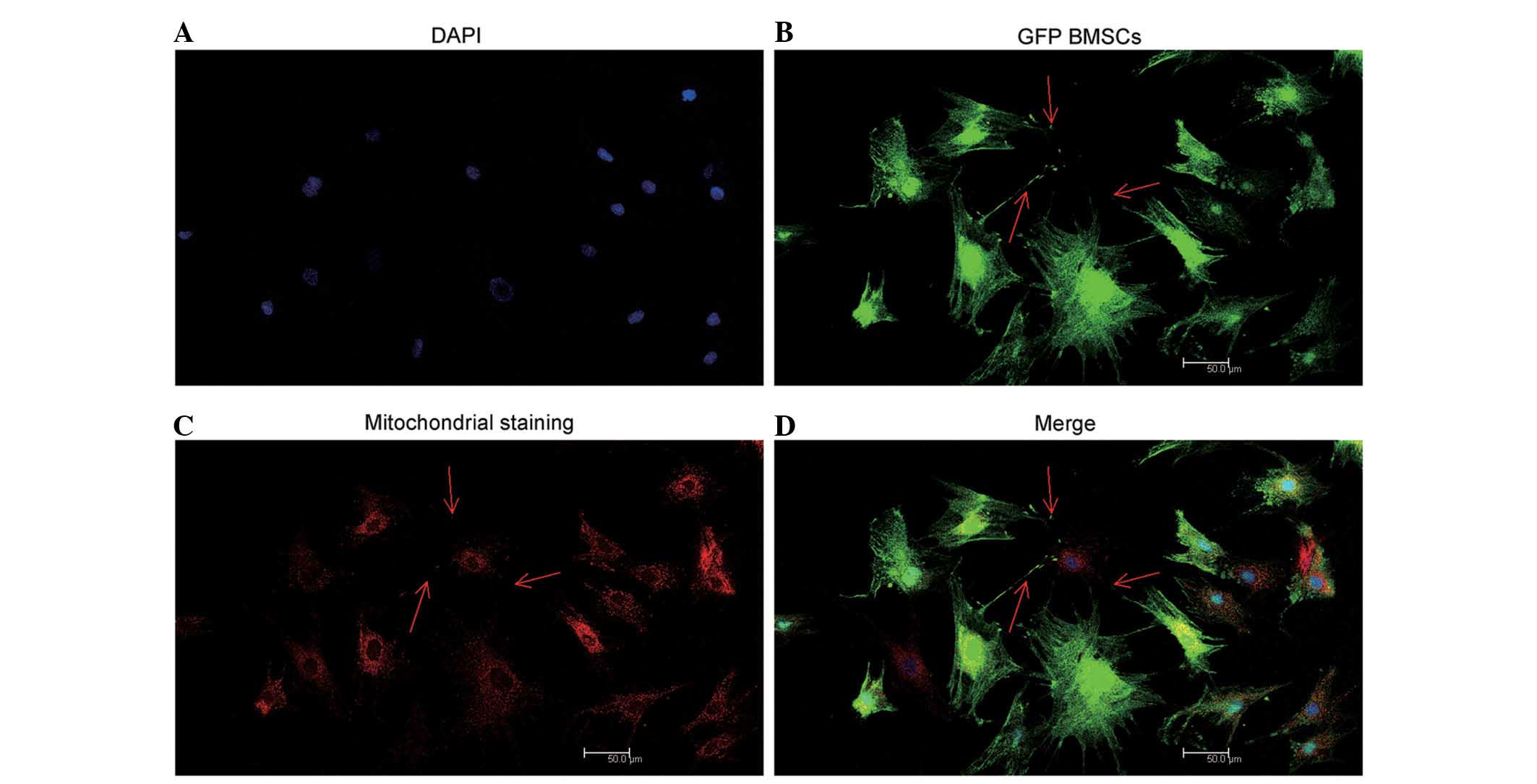

Mitochondrial transfer occurs between

direct co-cultured NP cells and BMSCs

The arrows in Fig.

6 indicate that TnT-like structures were observed between BMSCs

and NP cells by confocal microscopy. Mitochondria were clearly

observed in the red fluorescence channel, transferring from

relabeled GFP BMSCs to stimulated NP cells via TnTs (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In the present study, a novel model of BMSC

intervention was established in IVDD and the anti-apoptotic ability

of BMSCs in stimulated NP cells was observed to act via a paracrine

mechanism. In addition, the migration driven by IL-1β stimulation

and directed mitochondrial transfer was observed.

IL-1β has been used to induce inflammatory responses

in NP cells (6,9,24).

Following stimulation with IL-1β for 24 h, the majority of

degeneration indexes were increased and apoptosis was induced. To

simulate in vivo MSC-mediated damage repair processes

following inflammatory stimulation, Transwell chambers were used to

physically separate the two cell types. The use of a Transwell

chamber with a 0.4 µm pore size ensured that only secreted

factors were easily passed through the pores, while preventing

BMSCs from migrating through the pores via amoeboid-like formations

(20). Previous in vivo

studies have reported that these intercellular interactions involve

the indirect effects of cytokines, in addition to the influence of

cell migration and direct cell to cell contacts (25,26).

Through a series of experiments, the present study successfully

simulated and confirmed the directional migration of BMSCs toward

the inflammatory factor-stimulated cells. However, the model for

BMSC migration failed to completely mimic MSC action in vivo

and was only suitable to separately investigate the effects of

BMSCs on damaged cells.

In addition to paracrine effects and migration,

direct cell to cell communication must be addressed. The

observation of TnTs between MSCs and other cell types has been

reported by numerous previous studies (27,28).

MSCs are capable of transferring mitochondria to cells with

severely compromised mitochondrial function via TnTs (29). In the present study, only GFP BMSCs

were pre-labeled with MitoTracker® Red following 24 h

direct co-culture, however, the pre-simulated NP cells were labeled

red. Due to the fact that mitochondrial transfer by TnTs was

commonly observed in the present study between GFP BMSCs and NP

cells, which had suffered cellular damage (identified by DAPI), it

was suggested that migration of BMSCs may be directed and BMSCs may

transfer mitochondria into cells with severe damage. Unfortunately,

quantifying this is challenging and further investigation is

required.

The co-culture model established in the present

study demonstrated that BMSCs exert beneficial anti-apoptotic

effects on inflammatory factor-stimulated NP cells via paracrine

mechanisms. The anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic capacities of

MSCs, in addition to their mechanisms of action, have been reported

in other fields. MSCs co-cultured in inflammatory medium have been

reported to inhibit the activation of nuclear factor κ-B and

thereby control a series of inflammatory reactions (30). It has been reported that MSCs

secrete factors, including transforming growth factor-β and

prostaglandin E2, which can inhibit the activation of lymphocytes,

thereby also contributing to the suppression of inflammation

(31–33). The paracrine-mediated

anti-apoptotic effects are likely to be based on the activity of

growth factors produced by MSCs, which are able to prevent

oxidative stress by increasing the activity of antioxidants and

normalizing mitochondrial function (34). Previous studies have demonstrated

with in vivo and in vitro models that protein kinase

B (Akt) was significantly increased in cells treated with MSCs and

MSC culture medium, and that Akt exerts an anti-apoptotic effect

through the phosphorylation of the BLC-associated cell death

promoter protein (12,35,36).

In addition, serum may function as a positive factor, whcih reduces

the overall inflammatory and apoptotic indexes (9). Significant differences were detected

between the co-culture experiments with BMSCs and the monoculture

experiments lacking BMSCs. Through paracrine mechanisms, BMSCs were

suggested to exert an anti-apoptotic effect on the damaged cells,

migrating to the damaged cells and communicating with them via

TnTs. Therefore, in models of IVDD, MSC transplantation has been

reported to exert a significant therapeutic effect (15,17).

In conclusion, BMSCs actively migrate towards

inflammatory NP cells and effectively reduce the apoptotic rate in

NP cells following inflammatory stimulation via paracrine effects

and mitochondrial transfer through direct TnTs connections. The

in vitro model established in the present study simulates,

to a certain extent, these paracrine anti-apoptotic effects, in

addition to the migratory behavior of BMSCs. This model provided a

simple and accurate means to investigate the mechanisms underlying

the potentially beneficial therapeutic effects of BMSCs.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the Shanghai

Science and Technology Committee Project of International

Cooperation (grant no. 13430721000) and the Joint Research Project

on Major Diseases of Shanghai Health System (grant no.

2013ZYJB0502).

References

|

1

|

Waddell G: Low back pain: A twentieth

century health care enigma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 21:2820–2825.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ariga K, Miyamoto S, Nakase T, Okuda S,

Meng W, Yonenobu K and Yoshikawa H: The relationship between

apoptosis of endplate chondrocytes and aging and degeneration of

the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 26:2414–2420. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lotz JC, Colliou OK, Chin JR, Duncan NA

and Liebenberg E: Compression-induced degeneration of the

intervertebral disc: An in vivo mouse model and finite-element

study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 23:2493–2506. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yamada K, Sudo H, Iwasaki K, Sasaki N,

Higashi H, Kameda Y, Ito M, Takahata M, Abumi K, Minami A, et al:

Caspase 3 silencing inhibits biomechanical overload-induced

intervertebral disk degeneration. Am J Pathol. 184:753–764. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Le Maitre CL, Freemont AJ and Hoyland JA:

The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of human

intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis Res Ther. 7:R732–R745.

2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tian Y, Yuan W, Fujita N, Wang J, Wang H,

Shapiro IM and Risbud MV: Inflammatory cytokines associated with

degenerative disc disease control aggrecanase-1 (ADAMTS-4)

expression in nucleus pulposus cells through MAPK and NF- κB. Am J

Pathol. 182:2310–2321. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Roberts S, Caterson B, Menage J, Evans EH,

Jaffray DC and Eisenstein SM: Matrix metalloproteinases and

aggrecanase: Their role in disorders of the human intervertebral

disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 25:3005–3013. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang CC, Zhou JS, Hu JG, Wang X, Zhou XS,

Sun BA, Shao C and Lin Q: Effects of IGF-1 on IL-1β-induced

apoptosis in rabbit nucleus pulposus cells in vitro. Mol Med Rep.

7:441–444. 2013.

|

|

9

|

Zhao CQ, Liu D, Li H, Jiang LS and Dai LY:

Interleukin-1beta enhances the effect of serum deprivation on rat

annular cell apoptosis. Apoptosis. 12:2155–2161. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Takahashi H, Suguro T, Okazima Y, Motegi

M, Okada Y and Kakiuchi T: Inflammatory cytokines in the herniated

disc of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 21:218–224. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal

RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S and

Marshak DR: Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem

cells. Science. 284:143–147. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Morigi M, Rota C, Montemurro T,

Montelatici E, Lo Cicero V, Imberti B, Abbate M, Zoja C, Cassis P,

Longaretti L, et al: Life-sparing effect of human cord

blood-mesenchymal stem cells in experimental acute kidney injury.

Stem Cells. 28:513–522. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Richardson SM, Walker RV, Parker S, Rhodes

NP, Hunt JA, Freemont AJ and Hoyland JA: Intervertebral disc

cell-mediated mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells.

24:707–716. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sakai D, Mochida J, Yamamoto Y, Nomura T,

Okuma M, Nishimura K, Nakai T, Ando K and Hotta T: Transplantation

of mesenchymal stem cells embedded in Atelocollagen gel to the

intervertebral disc: A potential therapeutic model for disc

degeneration. Biomaterials. 24:3531–3541. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hiyama A, Mochida J, Iwashina T, Omi H,

Watanabe T, Serigano K, Tamura F and Sakai D: Transplantation of

mesenchymal stem cells in a canine disc degeneration model. J

Orthop Res. 26:589–600. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Crevensten G, Walsh AJ, Ananthakrishnan D,

Page P, Wahba GM, Lotz JC and Berven S: Intervertebral disc cell

therapy for regeneration: Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in rat

intervertebral discs. Ann Biomed Eng. 32:430–434. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sakai D, Mochida J, Iwashina T, Watanabe

T, Nakai T, Ando K and Hotta T: Differentiation of mesenchymal stem

cells transplanted to a rabbit degenerative disc model: Potential

and limitations for stem cell therapy in disc regeneration. Spine

(Phila Pa 1976). 30:2379–2387. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Strassburg S, Richardson SM, Freemont AJ

and Hoyland JA: Co-culture induces mesenchymal stem cell

differentiation and modulation of the degenerate human nucleus

pulposus cell phenotype. Regen Med. 5:701–711. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bi B, Schmitt R, Israilova M, Nishio H and

Cantley LG: Stromal cells protect against acute tubular injury via

an endocrine effect. J Am Soc Nephrol. 18:2486–2496. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang SH, Wu CC, Shih TT, Sun YH and Lin

FH: In vitro study on interaction between human nucleus pulposus

cells and mesenchymal stem cells through paracrine stimulation.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 33:1951–1957. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Li X, Zhang Y, Yeung SC, Liang Y, Liang X,

Ding Y, Ip MS, Tse HF, Mak JC and Lian Q: Mitochondrial transfer of

induced pluripotent stem cells-derived mesenchymal stem cells to

airway epithelial cells attenuates cigarette Smoke-induced damage.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 51:455–465. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Risbud MV, Guttapalli A, Stokes DG,

Hawkins D, Danielson KG, Schaer TP, Albert TJ and Shapiro IM:

Nucleus pulposus cells express HIF-1 alpha under normoxic culture

conditions: A metabolic adaptation to the intervertebral disc

microenvironment. J Cell Biochem. 98:152–159. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Karaliotas GI, Mavridis K, Scorilas A and

Babis GC: Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression levels of

BCL2 and BAX genes in human osteoarthritis and normal articular

cartilage: An investigation into their differential expression. Mol

Med Rep. 12:4514–4521. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Smith LJ, Chiaro JA, Nerurkar NL, Cortes

DH, Horava SD, Hebela NM, Mauck RL, Dodge GR and Elliott DM:

Nucleus pulposus cells synthesize a functional extracellular matrix

and respond to inflammatory cytokine challenge following long-term

agarose culture. Eur Cell Mater. 22:291–301. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang Z, Wang Y, Gutkind JS, Wang Z, Wang

F, Lu J, Niu G, Teng G and Chen X: Engineered mesenchymal stem

cells with enhanced tropism and paracrine secretion of cytokines

and growth factors to treat traumatic brain injury. Stem Cells.

32:456–467. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kawai T, Katagiri W, Osugi M, Sugimura Y,

Hibi H and Ueda M: Secretomes from bone marrow-derived mesencyhmal

stromal cells enhance periodontal tissue regeneration. Cytotherapy.

17:369–381. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Figeac F, Lesault PF, Le Coz O, Damy T,

Souktani R, Trébeau C, Schmitt A, Ribot J, Mounier R, Guguin A, et

al: Nanotubular crosstalk with distressed cardiomyocytes stimulates

the paracrine repair function of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem

Cells. 32:216–230. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vallabhaneni KC, Haller H and Dumler I:

Vascular smooth muscle cells initiate proliferation of mesenchymal

stem cells by mitochondrial transfer via tunneling nanotubes. Stem

Cells Dev. 21:3104–3113. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gerdes HH, Bukoreshtliev NV and Barroso

JF: Tunneling nanotubes: A new route for the exchange of components

between animal cells. FEBS Lett. 581:2194–2201. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yagi H, Soto-Gutierrez A, Navarro-Alvarez

N, Nahmias Y, Goldwasser Y, Kitagawa Y, Tilles AW, Tompkins RG,

Parekkadan B and Yarmush Ml: Reactive bone marrow stromal cells

attenuate systemic inflammation via sTNFR1. Mol Ther. 18:1857–1864.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Aggarwal S and Pittenger MF: Human

mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses.

Blood. 105:1815–1822. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Groh ME, Maitra B, Szekely E and Koç ON:

Human mesenchymal stem cells require monocyte-mediated activation

to suppress alloreactive T cells. Exp Hematol. 33:928–934. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ulivi V, Tasso R, Cancedda R and Descalzi

F: Mesenchymal stem cell paracrine activity is modulated by

platelet lysate: Induction of an inflammatory response and

secretion of factors maintaining macrophages in a proinflammatory

phenotype. Stem Cells Dev. 23:1858–1869. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

García-Fernández M, Delgado G, Puche JE,

González-Barón S and Castilla Cortázar I: Low doses of insulin-like

growth factor I improve insulin resistance, lipid metabolism and

oxidative damage in aging rats. Endocrinology. 149:2433–2442. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Eliopoulos N, Zhao J, Bouchentouf M,

Forner K, Birman E, Yuan S, Boivin MN and Martineau D: Human

marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells decrease cisplatin

renotoxicity in vitro and in vivo and enhance survival of mice

post-intraperitoneal injection. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

299:F1288–F1298. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kuwana H, Terada Y, Kobayashi T, Okado T,

Penninger JM, Irie-Sasaki J, Sasaki T and Sasaki S: The

phosphoinositide-3 kinase gamma-Akt pathway mediates renal tubular

injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 73:430–445. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|