Introduction

Wilms' tumors, also known as the embryonic tumors of

the kidneys, are one of the most common malignant, solid

retroperitoneal tumors observed in children, accounting for 5.5% of

all solid tumors in children (1) and

>80% of genitourinary tumors in children <15 years of age.

Although early diagnosis is important for deciding treatment

methods and ensuring satisfactory outcomes, the early symptoms of

Wilms' tumors are not clear. Therefore, the identification of

diagnostic biomarkers is crucial.

Proteomics can rapidly detect protein expression at

different stages of disease occurrence using high-throughput

screening to detect specific protein-labeled molecules. These

highly-expressed, specific proteins are useful in clinical

practice, as they can assist in early diagnosis and may become

targets for disease treatment. In previous years, a number of

methods, including surface-enhanced laser

desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

(SELDI-TOF-MS) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time

of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) technologies (2,3), have been

demonstrated to successfully detect specific markers for various

types of cancer, including ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, colon and

breast cancer (4–8).

Post-traumatic stress disorder is complex in nature,

encompassing changes in the neuroendocrine system, and in metabolic

and immune function, together with altered cytokine levels, which

culminate to provoke and accelerate tumor development (9). Since stress-related factors may produce

proteins that interfere with the identification of specific

proteins in the serum of patients with Wilms' tumors, the aim of

the present study was to investigate these post-traumatic

stress-related serum factors. Not only can traumatic stress-related

factors be found to exclude interference for later screening and

identification, the occurrence and development of tumors can also

be understood from the aspect of inflammation. To analyze the

effect of post-traumatic stress-related inflammatory factors on the

development of Wilms' tumors and to identify putative biomarkers,

SELDI-TOF-MS, MALDI-TOF-MS, solid-phase extraction (SPE), SDS-PAGE

and high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

(LC-MS) were used in tandem to detect proteins in the sera of

children with Wilms' tumors and compare them with sera isolated

from children with post-traumatic stress disorder and normal

children to identify post-traumatic stress-related factors. Using

this approach, highly-expressed specific proteins were screened and

identified in the sera of children with Wilms' tumors and those

with post-traumatic stress disorder. The specific protein marker of

post-traumatic stress disorder can be distinguished from the

specific marker that we had obtained from the serum of patients

with Wilms' tumors in our previous study (10), and may be used as a reference for

excluding the interfering effects of traumatic factors.

Materials and methods

Collection and treatment of the serum

samples

The study protocol was approved by the ethics review

committee of Zhengzhou University (Zhengzhou, China). Written

informed consent was obtained from each patient or their guardian.

All serum samples used in the current study were provided by the

Department of Pediatric Surgery of The First Affiliated Hospital of

Zhengzhou University and included 61 pre-operative serum samples

from children with Wilms' tumors, of which 28 presented with stage

I tumors, 18 with stage II tumors, 12 with stage III tumors and 3

with stage IV tumors. A total of 34 serum samples were obtained

from children with post-traumatic stress disorder (with sera

collected within 1–3 days of injury sustained during incidents,

including car accidents), and 60 serum samples were obtained from

normal children who underwent routine medical examinations. Whole

blood samples were harvested from the peripheral veins in the

morning prior to breakfast in all participants. After 1–2 h at 4°C,

the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3,000 × g. The sera were

collected, placed in numbered tubes and preserved separately at

−80°C.

Screening of differentially-expressed

serum proteins

The serum was gradually thawed in an ice bath for

30–60 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

Serum (5 µl) was added to 10 µl U9 serum solution, and was mixed

together at 4°C on a vibrating shaker (600 × g; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min. The serum treated

with U9 was diluted with binding buffer (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ,

USA) to 200 µl, mixed at 4°C on a vibrating shaker (600 × g) for 2

min, and loaded onto a WCX2 protein chip (Ciphergen Biosystems,

Fremont, CA, USA).

Firstly, the standard chip was used with proteins of

known molecular weight to adjust for errors of molecular weight in

the SELDI-TOF-MS system (Ciphergen Biosystems), to reach an error

level of <0.1%. Next, the chip was placed together with the

serum proteins into the mass spectrometer for detection. The

original data were collected using Proteinchip Software version 3.2

(Ciphergen Biosystems) with the laser intensity set to 185, the

detection sensitivity set to 7 and the upper limit of detection set

at 100,000 mass/charge (m/z). The range of optimized collected data

was 2,000–20,000 m/z. Certain factors were excluded based on

previous studies (11,12). To exclude these factors, recombinant

proteins were added to each group to screen for the differential

peak. If the differential peak corresponded to the peak value of a

certain factor to be excluded (the same m/z), this was screened out

and no further purification and identification were performed. The

differential peaks of post-traumatic specific factors were

identified.

Data processing

Correction of the original data was performed using

Biomarker Wizard software version 3.1 (Ciphergen Biosystems) to

homogenize the total ionic strength and molecular weight. The

Biomarker Wizard software and protein chip data analysis system

were used to remove the noise and subtract the baseline with the

discrete wavelet. The peak of each sample was obtained using a

method of finding the local extreme, and peaks with signal-to-noise

ratios of >2 were filtered out. The minimum threshold of the

cluster analysis was set to 10%, and the peaks with <0.3% m/z

were categorized. Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed for the

initially screened m/z peaks to obtain P-values and subsequently

evaluate the ability of each peak in differentiating various

groups. Mass spectrometric data of each sample were further

analyzed using the non-linear support vector machine (SVM)

(13) to screen and identify

differentially-expressed proteins. The radial basis function was

used for SVM, the γ parameter was set to 0.6 and the penalty

function was set to 19.

Statistical analysis

Subsequent to the noise being filtered, the original

mass spectrometric data were treated by cluster analysis, and

Student's t-tests were performed for the mass spectrometric data of

each group. P<0.05 was considered to indiciate a statistically

significant difference. Differentially-expressed proteins between

the groups were identified.

Isolation of serum proteins

Subsequent to the serum proteins being separated

into different groups with organic phase concentrations of 30, 50,

70 and 100% using SPE (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), they were packed

in an Eppendorf® tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), marked clearly

and then divided according to hydrophilicity. Each sample was dried

to 10 µl in a vacuum drying device (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), subsequent to which, 5 µl sample buffer was added, the

samples were boiled for 15 min and centrifuged at 5,000 × g, and

the supernatant was collected. The sample was next separated by gel

electrophoresis, and the gel was cut into several pieces based on

the corresponding molecular weight axis, placed in different

Eppendorf® tubes, washed, decolorized, dried and incubated with

trypsin for 15 h.

Identification of

differentially-expressed proteins

Proteins (1.5 µl) separated by SPE and

electrophoresis were mixed with 1.5 µl α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic

acid (CHCA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), placed on the target

plate and dried. Sample calibration was performed using cytochrome

c (molecular weight, 12,361.96; (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

plus CHCA and insulin (molecular weight, 5,734.51; (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) plus CHCA. The target plate was placed in the

MALDI-TOF-MS device (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) for

detection. The target protein peak was tracked, and serum samples

with a protein peak m/z of 5,816 were identified.

Identification of specific

proteins

Trypsin-digested serum proteins were identified by

peptide mass fingerprinting using LC-MS followed by Swiss-Prot

database analysis using the Mascot search engine.

MS data processing and database

searching

The MS data processing software used was Launchpad

version 2.4 (Shimadzu, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan). A spectrum search

was performed using the Mascot search engine of mouse and human

protein sequences, and the number of maximum allowable restriction

enzyme cutting sites was set to 1. The fixed modification was

cysteine iodoacetyl, and the variable modification was methionine

oxidation. Furthermore, the peptide mass tolerance was set to ±0.3

Da.

Verification of post-traumatic

stress-related protein markers using western blot analysis

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred

to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membranes were incubated

with primary polyclonal rabbit anti-human thioredoxin 1 (Trx1; cat.

no. bs-0458R; 1:1,000; Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd., Beijing, China) or GAPDH (cat. no. bs-0459R; 1:1,000; Beijing

Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) antibodies for 2 h at 37°C.

The membranes were washed three times with Tris-Buffered Saline and

Tween 20 (Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), followed

by incubation with horseradish peroxidase conjugated-goat

anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (cat. no. ZDR-5306; 1:5,000;

Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China)

for 2 h at 37°C. Bands were visualized using enhanced

chemiluminescence followed by image development and fixing. GAPDH

was used as an internal control. The negatives were scanned, and

the gray values of the protein bands in each negative were measured

using the ImagePro plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda,

MD, USA). The gray values were divided by group, and SPSS 13.0

software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to compare the

gray values in the different groups.

Results

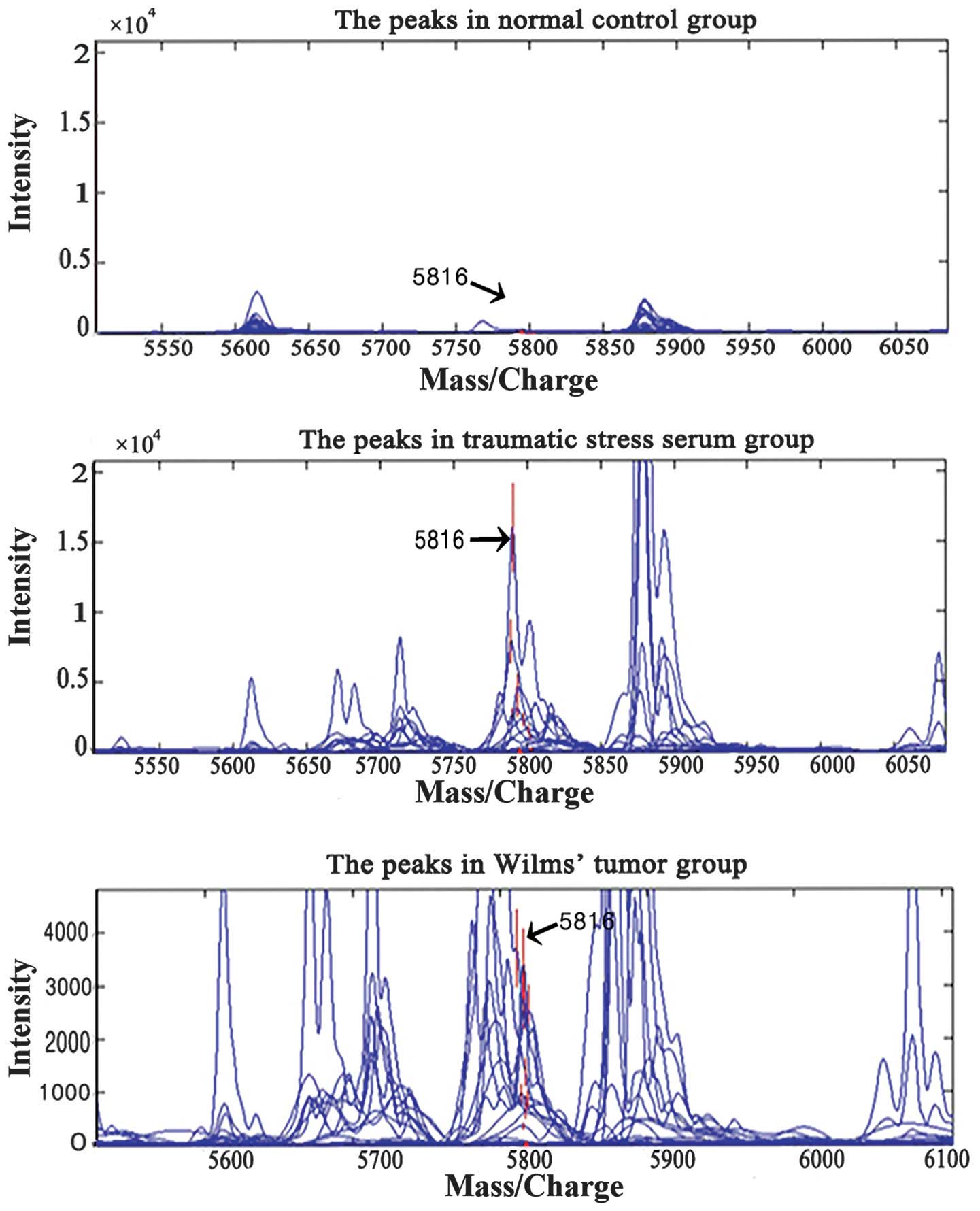

SELDI-TOF-MS analysis

SELDI-TOF-MS was used to screen sera from patients

in the tumor, trauma and normal control groups to identify specific

proteins with an m/z of 5,816. Subsequent to the initial screening

and statistical analysis of the mass spectra data from the tumor

and normal control groups, peaks of 15 m/z were obtained

(P<0.05; Fig. 1). SVM was used to

screen out models with the highest Youden's indices (i.e., the

difference between the true and false positive rates) of the

predictive value. Significantly higher expression of proteins with

an m/z of 5,816 was observed in the tumor group (mean,

2,128.3±137.2; 652.6±134.2 in stage I tumors, 1,152.6±423.1 in

stage II tumors, 1,652.6±523.1 in stage III tumors and

2,252.6±723.1 in stage IV tumors) as compared with children in the

control group (30.4±7.8) (P<0.05; Table I). When the potential markers were

taken as the input values, leave-one-out cross-validation proved

that the specificity of differentiating the combination model of

this marker on the test set was 100.0% and the sensitivity was

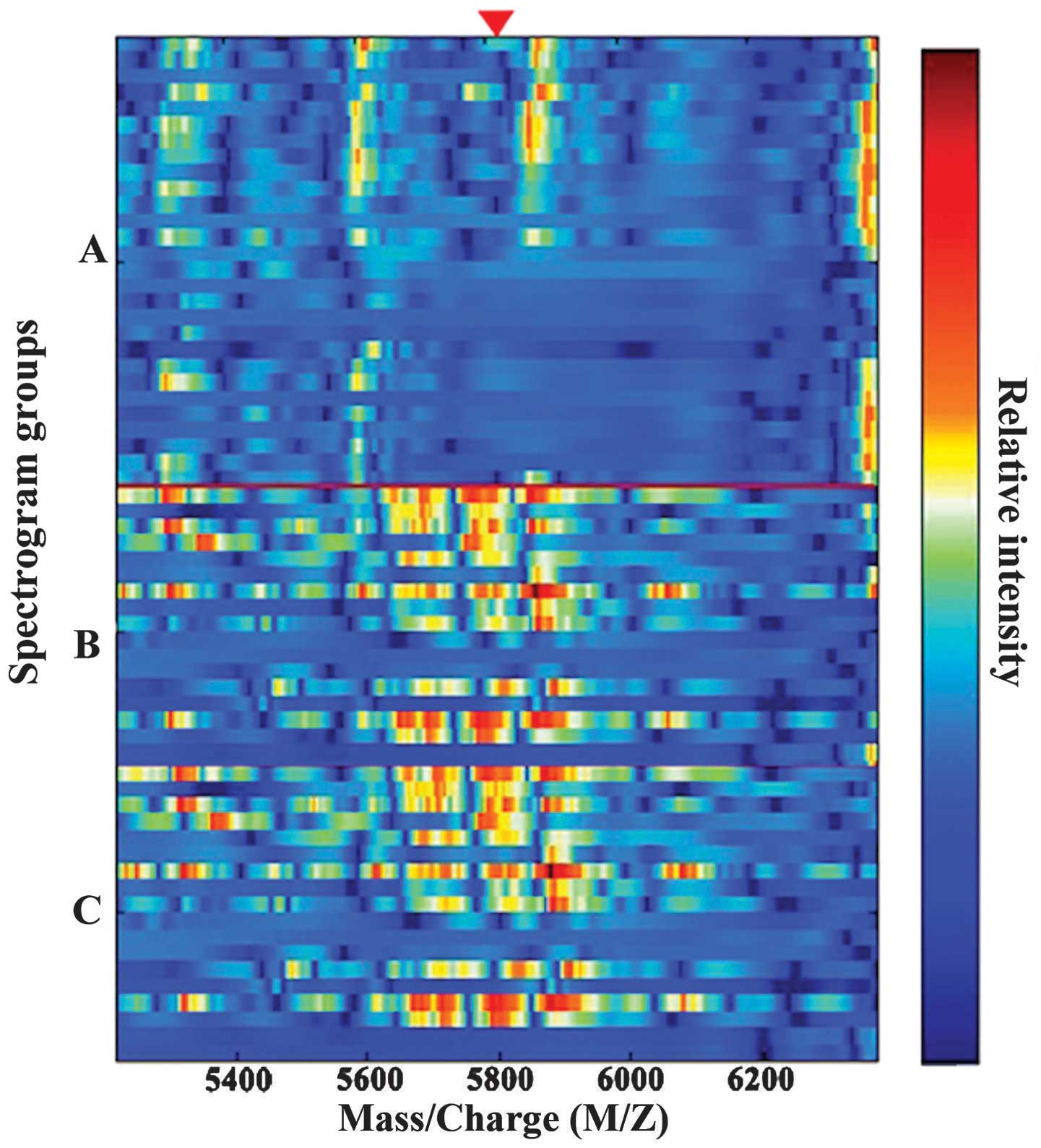

100.0%. Fig. 2 shows the simulated

protein electrophoresis between the tumor, normal and trauma

groups. Significantly greater levels of proteins with an m/z of

5,816 were also noted in the serum of the trauma group

(3,674.6±255.7) as compared with the normal group (30.4±7.8)

(P<0.05; Fig. 1; Table I).

| Table I.Expression level of proteins with a

mass/charge of 5,816 Da. |

Table I.

Expression level of proteins with a

mass/charge of 5,816 Da.

| Groups | Cases, n | Mean expression

±SD |

|---|

| Trauma | 34 | 3,674.6±255.7 |

| Tumor | 61 | 2,128.3±137.2 |

| Normal | 60 | 30.4±7.8 |

Identification of the putative

biomarker

Subsequent to the target protein being isolated and

purified using SPE and SDS-PAGE, the target peptide produced by

trypsin digestion was identified using high performance LC-MS

(Fig. 3). A Swiss-Prot protein

sequence database query via the Mascot search engine revealed that

the protein with an m/z of 5,816 may be thioredoxin 1 (Trx1). In

addition, the matching rate of the detected peptide amino acid

sequence and the human Trx1 sequence in the database was 46%

(Table II).

| Table II.Protein fragments with a mass/charge

of 5,816. |

Table II.

Protein fragments with a mass/charge

of 5,816.

| Mass/charge | Protein | Peptide sequence | Rate of coverage,

% | Score |

|---|

| 5,816 | Thioredoxin 1 |

MIKPFFHSLSEKVGEFSGANKE | 46.00 | 65.00a |

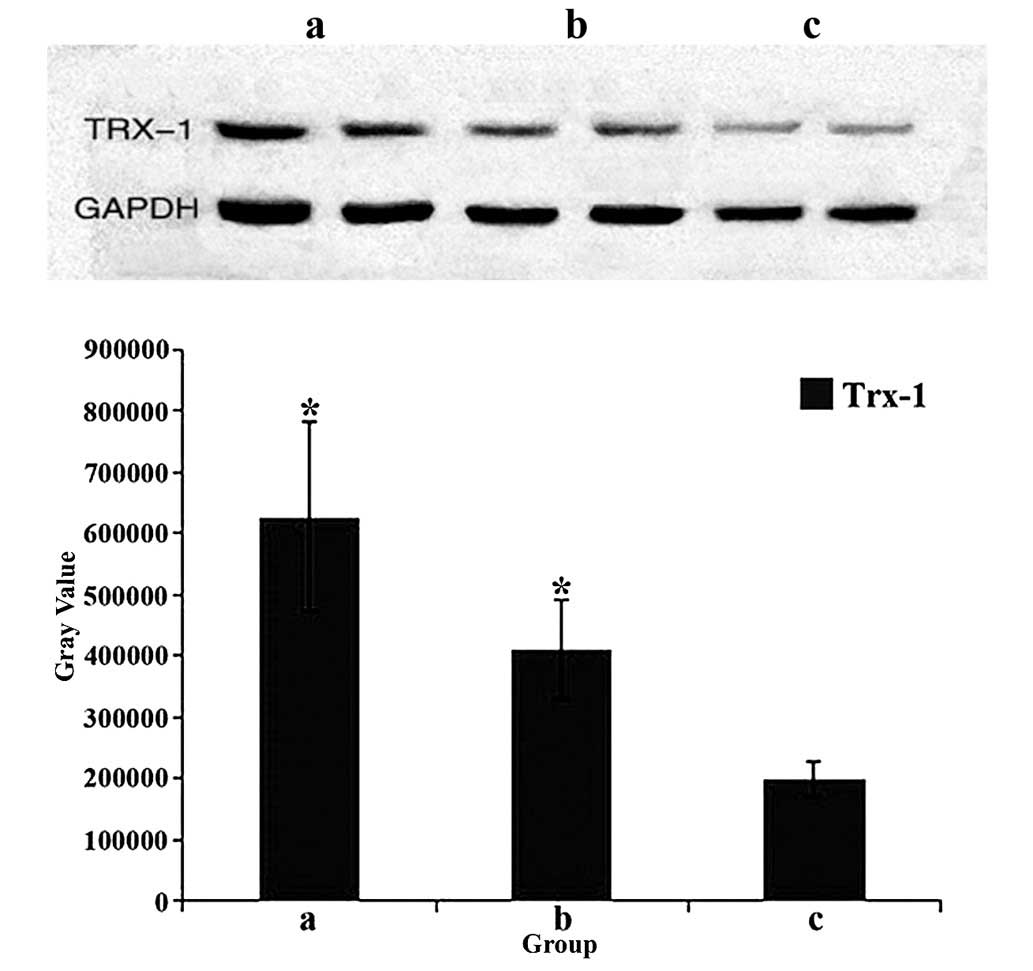

Verification of the target protein was performed

using western blot analysis of 30 randomly selected blood samples

(n=10 per group) to assess Trx1 expression, which was normalized to

GAPDH. For each experiment, two cases from each group were

selected. As shown in Fig. 4, the

highest levels of Trx1 were observed in the trauma group

(P<0.05), and the lowest levels were found in the normal control

group (P<0.05). In addition, significantly higher Trx1 levels

were detected in the tumor group as compared with the control group

(P<0.05).

Discussion

In the current study, SELDI-TOF-MS was used to

screen the sera of patients in the tumor, trauma and control

groups. Protein with an m/z of 5,816 was isolated and purified

using SPE and SDS-PAGE, and was identified as Trx1. Finally, the

presence of significantly increased Trx1 levels in the tumor group

was verified by western blot analysis.

At present, Wilms' tumors cannot be cured

completely, and the treatment is mainly targeted at patients with

mid- to late-stage tumors, and includes surgery and chemotherapy.

The main reason for the poor prognosis of patients with Wilms'

tumors is the delay in early diagnosis and consequently, treatment

initiation. Thus, it is critical to find a simple but accurate

method for the early detection of Wilms' tumors.

Reiche et al (14) reported a positive correlation between

stress and tumor development. Stress affects tumor development

mostly by regulating the neuroendocrine-immune network (15). Stress-induced changes in the circadian

rhythm of the body also play a significant role, and these changes

are mediated by changes in endocrine mediators (e.g.

glucocorticoids, thyrotrophin, growth hormone and luteinizing

hormone), metabolic disorders (changes in body temperature,

proteins and enzymes) and immune dysfunction, to finally induce and

accelerate tumor development and escape of tumor cells from immune

surveillance (9).

In children with Wilms' tumors, tumor compression

and bleeding may induce the release of post-traumatic

stress-related factors, thereby affecting the sensitivity and

accuracy of Wilms' tumor-specific proteins. Furthermore, certain

small molecular weight proteins cannot be easily detected due to

their own characteristics and low concentrations. Therefore, it is

important to identify a factor with a molecular weight similar to

that of the factor obtained in our previous studies, which is

specific to Wilms' tumors alone (10). In the present study, a protein with an

m/z of 5,816 was identified as Trx1, with a coverage of 46%,

suggesting that trauma-related factors exist in the serum of

children with Wilms' tumors. However, their direct or indirect

roles in pediatric tumor initiation or progression should be

verified by further studies.

Trx1, with a molecular weight of 12 kDa, exists in

almost every organism, and exhibits key functions in a number of

important biological activities, including redox signaling; it is

also a critical factor in tumor development (16). Specifically, Trx1 can directly inhibit

the activity of apoptosis signal-regulated kinase-1 to reduce the

rate of tumor cell death and enhance tumor cell growth factor

expression, thereby accelerating tumor cell growth (17,18). Trx1

can also induce the synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor

to promote angiogenesis and the extension of tumor blood vessels.

In addition, it can antagonize the cancer suppressor protein in the

advanced stage of cancer, promoting tumor metastasis (19). Trx1 is also overexpressed in colon

cancer, significantly accelerating tumor invasion and metastasis

(20).

The current study applied SELDI-TOF-MS technology

along with SVM to screen out post-traumatic stress-related protein

markers with an m/z of 5,816. The specificity and sensitivity of

the identified marker, Trx1, were each 100%, and the intensity of

its expression may be associated with factors such as the

individual differences in the serum samples, experiment process and

errors. Together with inflammatory markers and those biomarkers

described in previous studies (e.g. serum amyloid A and

apolipoprotein CIII) (21,22), Trx1 forms an ideal diagnostic marker,

as its levels were significantly higher in the sera of children

with Wilms' tumor and in those patients with post-traumatic stress

disorder in the present study. The relatively high expression level

in the serum of children with tumors is in accordance with its high

expression level in adult tumors, which suggests that it is a

post-traumatic stress-related serum factor of Wilms' tumors.

Combined with the results of our previous study (10), the current study demonstrated that the

post-traumatic stress-related specific protein that was screened

out was Trx1. The post-traumatic stress-related factor Trx1 was

expressed in the serum of children with Wilms' tumors. The results

shown in this study present the novel idea that enzymes indicative

of oxidative stress may be used as markers for the serological

diagnosis, malignancy grading and prognostic evaluation of Wilms'

tumor, and may form the basis of future studies with larger

cohorts.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81071782).

References

|

1

|

Kaatsch P: Epidemiology of childhood

cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 36:277–285. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Maurya P, Meleady P, Dowling P and Clynes

M: Proteomic approaches for serum biomarker discovery in cancer.

Anticancer Res. 27:1247–1255. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Diamandis EP: Mass spectrometry as a

diagnostic and a cancer biomarker discovery tool: opportunities and

potential limitations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 3:367–378. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang J, Zhang X, Ge X, Guo H, et al:

Proteomic studies of early-stage and advanced ovarian cancer

patients. Gynecol Oncol. 111:111–119. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Skytt A, Thysell E, Stattin P, Stenman UH,

Antti H and Wikstrom P: SELDI-TOF MS versus prostate specific

antigen analysis of prospective plasma samples in a nested

case-control study of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 121:615–620.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu D, Cao L, Yu J, et al: Diagnosis of

pancreatic adenocarcinoma using protein chip technology.

Pancreatology. 9:127–135. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hundt S, Haug U and Brenner H: Blood

markers for early detection of colorectal cancer: a systematic

review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 16:1935–1953. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gonçalves A, Bertucci F, Birnbaum D and

Borg JP: Proteic profiling SELDI-TOF and breast cancer: clinical

potential applications. Med Sci (Paris). 23:23–26. 2007.(In

French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cao WG: Mechanism of tumor development

affecting traumatic stress. Yi Xue Zong Shu. 6:830–832. 2012.(In

Chinese).

|

|

10

|

Wang J, Wang L, Zhang D, et al:

Identification of potential serum biomarkers for Wilms tumor after

excluding confounding effects of common systemic inflammatory

factors. Mol Biol Rep. 39:5095–5104. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chechlinska M, Kowalewska M and Nowak R:

Systemic inflammation as a confounding factor in cancer biomarker

discovery and validation. Nat Rev Cancer. 10:2–3. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hou JM, Zhao X, Tian L, et al:

Immunotherapy of tumors with recombinant adenovirus encoding

macrophage inflammatory protein 3beta induces tumor-specific immune

response in immunocompetent tumor-bearing mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

30:355–363. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu Y: Active learning with support vector

machine applied to gene expression data for cancer classification.

Chem Inf Comput Sci. 44:1936–1941. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Reiche EM, Nunes SO and Morimto HK:

Stress, depression, the immune system and cancer. Lancet Oncol.

5:617–625. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shastri A, Bonifati DM and Kishore U:

Innate immunity and neuroinflammation. Mediators Inflamm.

2013:3429312013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kodama A, Watanabe H, Tanaka R, et al: A

human serum albumin-thioredoxin fusion protein prevents

experimental contrast-induced nephropathy. Kidney Int. 83:446–454.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

de Oliveira Navakoski K, Andermark V, von

Grafenstein S, et al: Butyltin (IV) benzoates: inhibition of

thioredoxin reductase, tumor cell growth inhibition and

interactions with proteins. Chem Med Chem. 8:256–264. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lu A, Wangpu X, Han D, et al: TXNDC9

expression in colorectal cancer cells and its influence on

colorectal cancer prognosis. Cancer Invest. 30:721–726. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kakolyris S, Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis

M, et al: Thioredoxin expression is associated with lymph node

status and prognosis in early operable non-small cell lung cancer.

Clin Cancer Res. 7:3087–3091. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lincoln DT, Alyatama F, Mohammed FM, et

al: Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase expression in thyroid

cancer depends on tumour aggressiveness. Anticancer Res.

30:767–775. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang J, Guo F, Wang L, Zhao W, Zhang D,

Yang H, Yu J, Niu L, Yang F, Zheng S and Wang J: Identification of

apolipoprotein C-I as a potential Wilms' tumor marker after

excluding inflammatory factors. Int J Mol Sci. 15:16186–16195.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang Q, Wang J, Dong R, Yang S and Zheng

S: Identification of novel serum biomarkers in child nephroblastoma

using proteomics technology. Mol Biol Rep. 38:631–638. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|