Introduction

Telomerase is a special type of RNA nuclear protease

that maintains the function of the telomere and has an important

role in the immortalization of cells, as well as the genesis and

progression of cancer (1,2). Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA

polymerase that synthesizes telomeric DNA sequences, which provide

tandem GT-rich repeats (TTAGGG) that compensate telomere shortening

and have an important role in cellular aging and carcinogenesis.

Human telomerase usually consists of three subunits: human

telomerase RNA (hTR), human telomerase associated protein 1 (TEP1)

and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT). The hTERT gene

is the most important regulator of telomerase activity (3).

Previous studies have demonstrated that telomerase

activity is absent from most normal human somatic cells, but

present in >90% of tumor cells and immortalized cells (4–6).

Numerous studies have shown that antisense gene therapy directed

against telomerase RNA or hTERT components may effectively inhibit

telomerase activity and induce apoptosis in gastric cancer,

malignant gliomas, colon cancer and ovarian cancer (7–10).

Previous studies have also demonstrated that the growth of tumor

cells may be inhibited by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ASODNs)

that are targeted to the hTERT gene in a wide variety of tumor

types (11,12). The positive rate of telomerase

expression has been found to be ≤90.48% in esophageal carcinoma

tissue, whereas telomerase is not expressed in normal esophageal

tissue and leiomyoma of the esophagus (13).

In the present study, a phosphorothioate antisense

oligodeoxynucleotide (PS-ASODN) against hTERT was used to treat the

human Eca-109 esophageal cancer cell line. The inhibitory effect

and the mechanism of the PS-ASODN were investigated in the

esophageal cancer cells in order to explore novel strategies for

esophageal cancer gene therapy.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human esophageal cancer cells (Eca-109) were

obtained from the Cancer Institute and Hospital (Chinese Academy of

Medical Sciences, Beijing, China). RPMI-1640 medium was purchased

from Gibco-BRL (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and MTT was obtained from

Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Based on the sequencing of hTERT gene

cDNA, an antisense sequence was designed that was complementary to

the original code sequence and was 15 base pairs in length

(5′-GGAGCGCGCGGCATC-3′). The original code sequence is absent from

all known human genes other than hTERT. In addition, a control

N-ASODN was designed (5′-ACCTGGCACCGGCGG-3′). The hTERT-targeted

antisense oligodexynucleotide (PS-ASODN) and N-ASODN (all

phosphorothioate modified) were provided by Shanghai Biotechnology

Corporation (Shanghai, China). Liposomes (Lipofectin) were

purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

The semi-quantitative telomerase detection kit was obtained from

the Department of Genetics of Shandong University (Jinan, China),

the microplate reader model 550 was purchased from Bio-Rad

(Hercules, CA, USA) and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) thermal

cycler was obtained from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA). The image

scanning and analysis system was obtained from AlphaInnotech

Corporation (San Leandro, CA, USA).

Cell culture and transfection

Eca-109 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

(5×104 cells/ml, 37°C, 5% CO2 and under

saturated humidity). The medium was changed every other day. Cells

in the logarithmic growth phase were used for transfection.

MTT colorimetric assay

Eca-109 cells were seeded in 96-well plates with 100

μl cell-culture medium in each well at a cell concentration of

5×104/ml. Cells were cultured to the logarithmic growth

phase and PS-ASODN was then added to the experimental group with

final concentrations of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 μmol/l, while N-ASODN was

added to the control group at a concentration of 5 μmol/l.

RPMI-1640 cell culture medium was added to the blank control group.

The cells were then cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 and

saturated humidity. Cells were cultured for various times (1, 5, 10

and 15 days). The cell survival rate was measured using the MTT

colorimetric assay.

The absorbance (A value) was measured at a

wavelength of 570 nm by a microplate reader, with the A value at a

wavelength of 620 nm used as a reference, and the inhibition rate

of the cells was calculated as follows: Inhibition rate (%) = A

value (control group) - A value (test group)/A value (control

group) - A value (blank group) ×100.

Morphological observation

Eca-109 cells were treated with PS-ASODN (1–5

μmol/l) and N-ASODN (5 μmol/l) under culture conditions and the

growth status and morphologic changes of the cells were then

observed using an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Giemsa staining

Initially, 100 μl of conventional trypsin digestion

cells were extracted onto a slide glass and dried up naturally.

Next, Giemsa solution was added diluted by phosphate buffer

solution and stored at room temperature for 3–5 min; The rear side

of the glass was rinsed and after natural drying, the glass was

sealed with resin and covered with coverslips. Finally, it was

observed using an optical microscope (TMS phase contrast

microscope; Nikon Corporation).

Telomeric repeat amplification protocol

(TRAP)-silver staining

Cells were collected following treatment under

various conditions, and the number of living cells was counted

using Trypan blue staining. Approximately 1×104 cells

were obtained and washed using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The

cells were centrifuged and the supernatant was discarded. CHAPS

lysis buffer (10 μl) was then added and telomerase was extracted

for the TRAP reaction. The procedure was as follows: the

supernatant (1 μl) was added to a reaction liquid containing the

forward primer (25 μl) and the reaction mixture was incubated at

30°C for 30 min in order to complete the process of telomere

extension mediated by telomerase. Primers (1 μl), Taq enzyme (1 μl)

and proline (20 μl) were then added. A PCR reaction was then

performed under the following conditions: 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for

30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec for a total of 30 cycles. The forward

primer (TS) sequence was 5′-GGAGCGCGCGGCATC-3′, and the reverse

primer (CX) sequence was 5′-ACCTGGCACCGGCGG-3′. Following PAGE gel

casting, electrophoresis buffer (1X Tris-borate-EDTA) was placed in

the electrophoresis tank. The TRAP amplification reaction products

and loading buffer (containing bromophenol blue and xylenocyanol)

were combined and electrophoresed at 200 V until the bromophenol

blue reached the bottom of the gel and xylenocyanol was ~2 cm from

the bottom. The gel was removed and subjected to dyeing for 10 min

with 0.2% silver nitrite, fixing with alcohol for 5 min and rinsing

with double-distilled water. Images were then captured for data

analysis. The strength of the telomerase activity was indicated by

the number of 6-bp spaced bands and the gray strength of the bands.

The results from the electrophoresis were scanned and stored using

SmartView (Oracle, Redwood City, CA, United States), a biological

electrophoresis image analysis system. The telomerase activity of

the control group was taken as 100, and the relative telomerase

activity was calculated for each of the other groups. The

associations of the concentration and treatment time of the

PS-ASODN with the telomerase activity of the Eca-109 cells were

then analyzed.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using SPSS software, version

11.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Variance analysis, t-tests and

linear correlation were used for the analysis. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of PS-ASODN on Eca-109 cell

growth

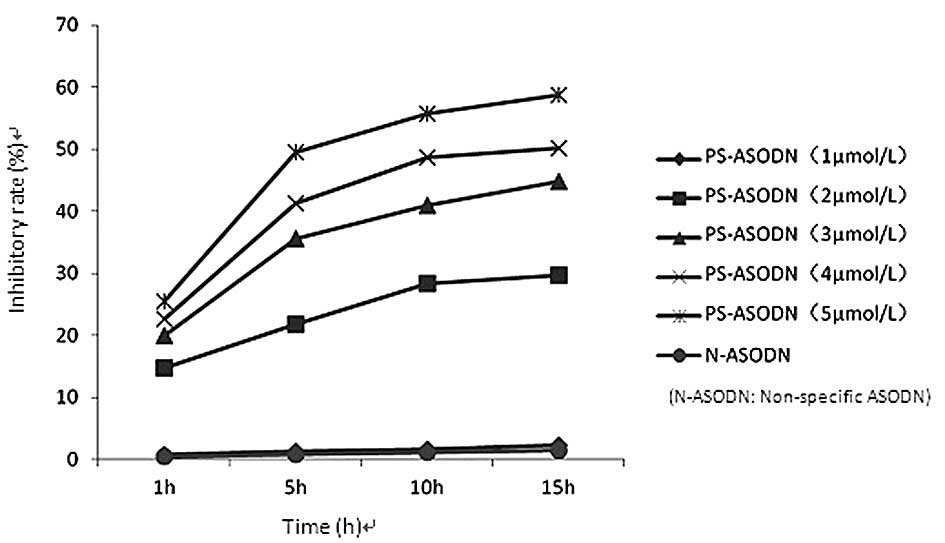

The proliferation of Eca-109 cells was found to be

inhibited following treatment with PS-ASODN (1–5 μmol/l). The

difference in the inhibition rate between the PS-ASODN group and

the blank control group was statistically significant (P<0.05)

when the concentration of PS-ASODN was ≥2 μmol/l, whereas no

significant difference was observed between the N-ASODN group and

blank control group (Table I,

Fig. 1). The inhibition rate

increased with time and as the concentration of PS-ASODN increased,

which indicates that PS-ASODN inhibited the growth of Eca-109 cells

in a concentration-, time- and sequence-specific manner.

| Table IEffect of a hTERT-targeted PS-ASODN on

Eca-109 cell growth (inhibition ratio, %). |

Table I

Effect of a hTERT-targeted PS-ASODN on

Eca-109 cell growth (inhibition ratio, %).

| Group | Concentration

(μmol/l) | Time (days) |

|---|

|

|---|

| 1 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

|---|

| B | 5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| C (N-ASODN) | 5 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| T1 (PS-ASODN) | 1 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| T2 (PS-ASODN) | 2 | 14.7a | 21.7a | 28.3a | 29.6a |

| T3 (PS-ASODN) | 3 | 20.0a | 35.6a | 40.9a | 44.8a |

| T4 (PS-ASODN) | 4 | 22.7a | 41.3a | 48.7a | 50.2a |

| T5 (PS-ASODN) | 5 | 25.4a | 49.5a | 55.8a | 58.8a |

Morphological changes of the cells

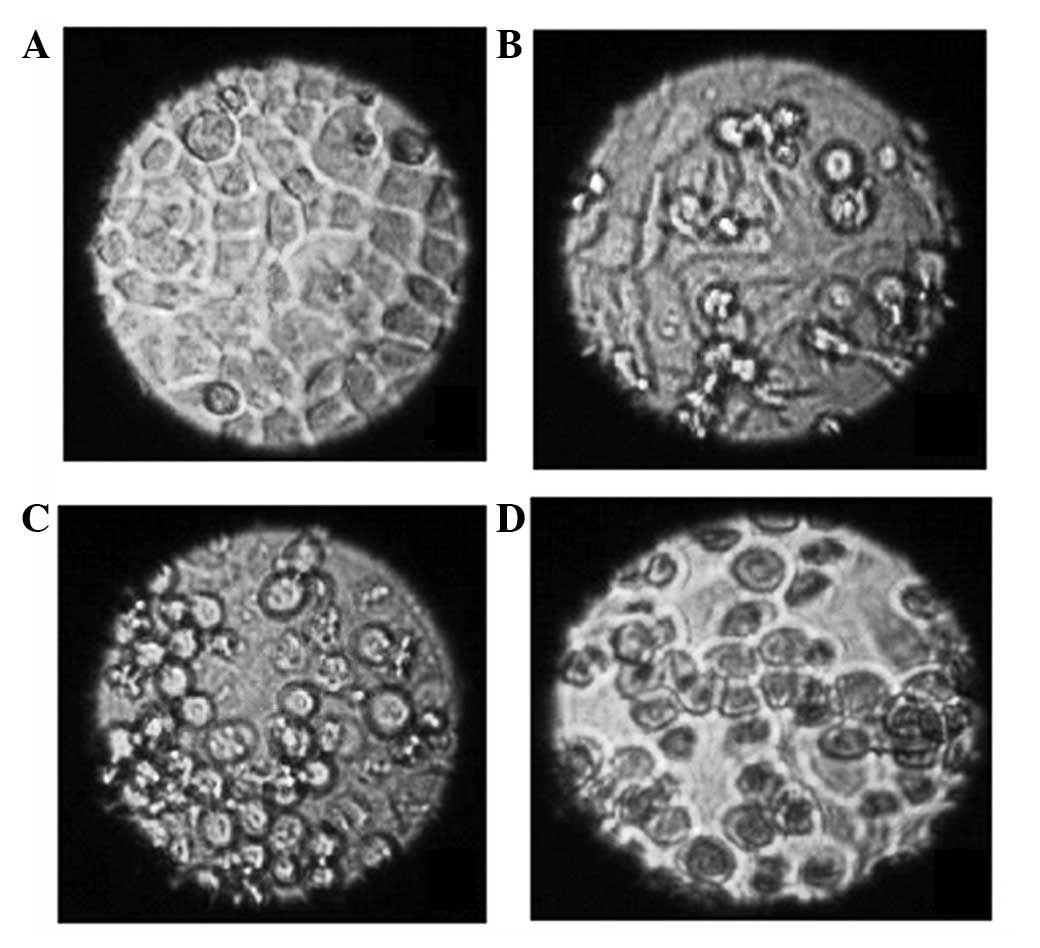

Living cells were observed using an inverted

microscope and it was found that cells treated with N-ASODN and

cells in the blank control group were all epithelial and adhered to

the well, the cell outlines were clear, the cells were close

together and proliferation was rapid (Fig. 2A). There was no significant

difference between the treatment group (2 μmol/l PS-ASODN, 24 h)

and control group in morphology; however, cell growth was slower in

the PS-ASODN group (Fig. 2B).

After 10 days, the cells treated with PS-ASODN gradually became

round and began to float in the medium and the number of floating

cells gradually increased with time. Furthermore, certain cells

were reduced in size, chromatin condensation was observed, the

density increased and an increased number of granules was observed

in the cells (Fig. 2C). These

morphological changes were more marked when the concentration of

PS-ASODN was increased to 5 μmol/l, and as the time of treatment

was extended (Fig. 2D).

Time-dependent effect of telomerase

regulation by PS-ASODN in Eca-109 cells

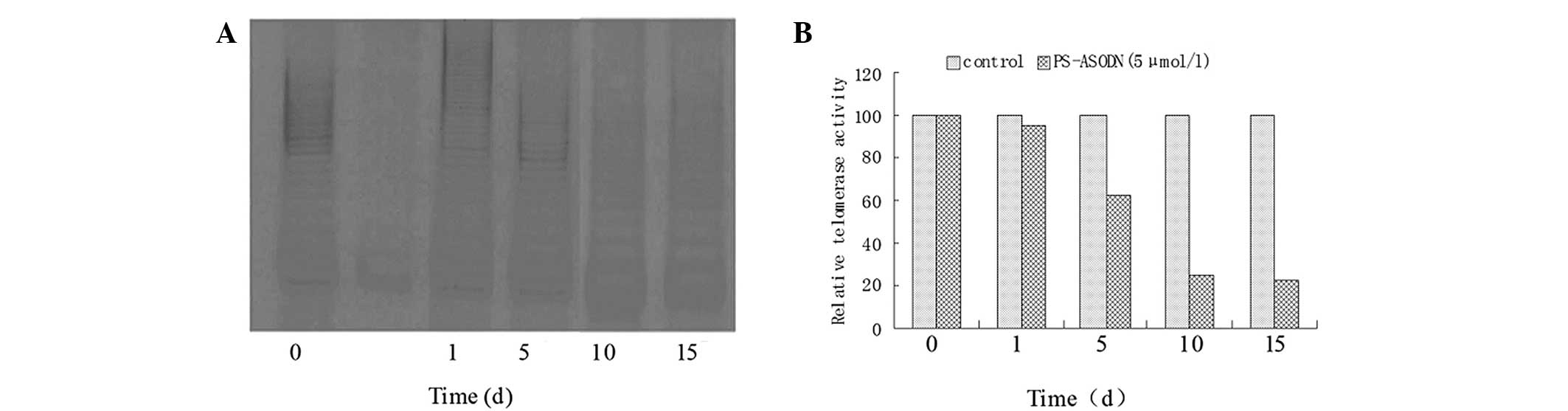

The telomerase activity decreased slightly after 24

h of treatment with 5 μmol/l PS-ASODN and the relative telomerase

activity was 95 (vs. 100 at 0 h). After 5 days, the telomerase

activity decreased sharply and the relative telomerase activity was

63 (37% decrease), which was significantly lower compared with the

control group (P<0.05). After 10 and 15 days, the relative

telomerase activity was 25 and 22, respectively (Fig. 3). By contrast, no reduction in the

telomerase activity was observed in cells following treatment with

5 μmol/l N-ASODN (data not shown).

Dose-effect association of telomerase

regulation by PS-ASODN in Eca-109 cells

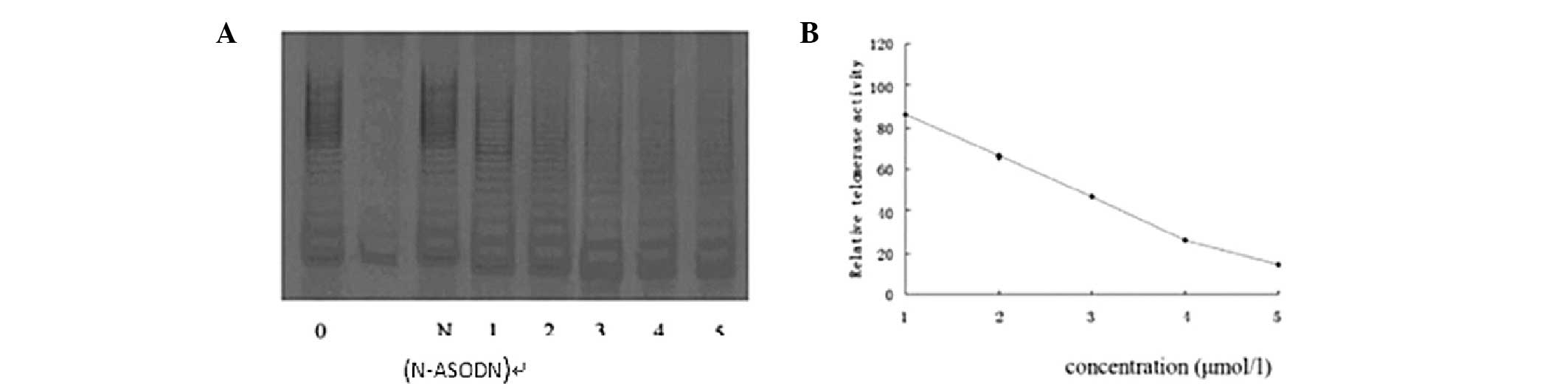

After 10 days, the relative telomerase activity was

86, 66, 47, 26 and 14, respectively, when Eca-109 cells were

treated with 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 μmol/l PS-ASODN. The telomerase

activity declined by 14, 34, 53, 74 and 86% accordingly. This

indicates that as the concentration of PS-ASODN increased, the

inhibitory effect on Eca-109 cells increased, which indicates that

PS-ASODN acts in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4).

Discussion

High telomerase activity has been observed in

malignant tumors; however, in the majority of normal tissues (with

the exception of germ cells, hematopoietic cells and certain stem

cells that have proliferation potential) and benign tumors,

telomerase activity has been found to be low (14). The activation of telomerase is

thought to be a final shared pathway for cell malignant

transformation or immortalization; therefore, telomerase is

considered to be an ideal target for gene therapy. Telomerase

consists of 3 subunits, hTR, hTERT and TEP1. hTERT is a single copy

gene that has recently been cloned and whose gene group contains a

unique, highly conserved sequence. Previous studies have

demonstrated that hTERT mRNA is only expressed in malignant tumors,

tumor cells or certain highly potential auto-regenerated tissues

(for example, the endometrium), and the expression of hTERT mRNA

has been found to be correlated with telomerase activity. hTERT has

been demonstrated to be specifically expressed in cancers and it

has been shown to regulate the rate of telomerase activity

(15). ASODNs have gained an

increasing amount of attention recently due to their high

specificity and targeting and low toxicity, and may potentially be

used for gene therapy. ASODN gene therapy is based on the

Watson-Crick principle of complementary base pairing. Artificial or

biologically compounded DNA or a section of DNA is synthesized

comprising a short chain of ~15–27 nucleotides that is chemically

treated and complementary to the target sequence. The ASODN then

targets the gene or mRNA, forming a double chain structure that

inhibits transfixion or translation, thereby inhibiting the

production of the protein encoded by the gene. The mechanism of

ASODN treatment is as follows: i) Combination with the target DNA

sequence and establishment of a tri-chain structure (U-type

complementation), prohibiting the replication or transfixion of the

target gene; ii) combination with the particular sequence of mRNA

to form a double chain structure that prevents the ribosome from

binding to the target mRNA, resulting in the inhibition of the

expression of mRNA or activation of RNase H, which degrades the

target mRNA by degrading the unusual double chain structure of the

hetero-molecules; iii) complementing to the end coding sequence or

the bottom sequence of mRNA5’ to inhibit the translation. It is

essential to ensure that the ASODN is stabilized prior to its use

for inhibition of the target gene. In order to do this, chemically

treated oligodeoxynucleotides are introduced into the ASODN,

including modifications to the phosphate backbone and pentose units

(primarily at the 2-hydroxy group of ribose). Among these

chemically treated derivatives, PS-ASODNs have a greatly increased

resistance to degradation of the oligodeoxynucleotide by nuclease.

In addition, PS-ASODNs have a good aqueous solubility, are stable

and may be rapidly prepared in large quantities, and so can meet

the clinical need (16,17).

A number of previous studies have used hTR as target

and used ASODNs to affect the cell cultures of ovarian cancer and

prostate cancer in vitro, and demonstrated that ASODNs

inhibit telomerase activity and induce cell apoptosis (18,19).

However, whether antisense hTR decreases the activity of telomerase

and inhibits tumor growth in all types of cancer (for example,

esophageal cancer) requires further investigation. The telomerase

activity is high in the Eca-109 esophageal carcinoma cell line;

however, studies concerning the effects of telomerase-targeting

ASODNs in esophageal carcinoma cell lines are rare. In a previous

study, we designed a PS-ASODN against hTR and applied it to Eca-109

cell cultures, and the results demonstrated that the PS-ASODN

inhibited the activity of telomerase and inhibited tumor growth

(20). However, hTR is widely

expressed in normal tissues; therefore, adverse reactions may occur

in normal cells and tissues if hTR is used as a target for

antisense therapy. Previous studies have demonstrated that hTERT is

the catalytic subunit of telomerase and also regulates telomerase

activity. In addition, the expression of hTERT in cells and tissues

has been found to be associated with telomerase activity (15,21,22).

Therefore, this suggests that hTERT may be a more suitable target

than hTR for antisense therapy.

Shammas et al (16) demonstrated that GRN163L, an

antisense oligonucleotide targeting telomerase RNA, inhibited

telomerase activity in bone marrow cells and induced cell death.

Telomerase activity has been found to be associated with cell

proliferation; therefore, the inhibition of telomerase activity may

inhibit cell proliferation (23).

Another study demonstrated that an antisense oligonucleotide

specifically targeted against hTERT in human prostate cancer cells

reduced telomerase activity, decreased proliferation and,

eventually, induced cell death, indicating that hTERT is directly

associated with the growth and proliferation of tumor cells

(11). The interference of RNA

with the expression of hTERT in cancer cells may effectively

inhibit telomerase activity and strengthen the sensitivity of the

cancer cells to ionizing radiation and chemotherapy (24).

In the present study, an 15-base ASODN was

synthesized, which was then liposome-encapsulated and used to

target hTERT in Eca-109 cells following phosphorothioate

modification. The PS-ASODN was demonstrated to have an inhibitory

effect on cell growth in a concentration- and time-dependent

manner. However, N-ASODN had no inhibitory effect on the growth of

Eca-109 cells, indicting that the inhibitory effect of PS-ASODN on

cell growth was sequence specific. The results from the TRAP-silver

staining assay used to detect the telomerase activity demonstrated

that the telomerase activity was negatively correlated with

concentration and time, and the inhibitory effect was dose- and

time-dependent. Treatment with the ASODN caused the cells to decay

and induced morphological changes. Using an inverted phase-contrast

microscope, cells of the N-ASODN and blank groups grew well, close

to the well wall and close together. The outlines of the cells were

clear and spindle shapes were observed. Particles within the

cytoplasm were rare and the nucleus was visible, which indicated

that the cells were growing rapidly. However, in the PS-ASODN

group, a number of cells were round and floating, the cells were

loosely associated with vague outlines, an increasing number of

particles was observed and proliferation was slow. Following Giemsa

staining, the N-ASODN and blank group cells looked full, with

evenly stained, clear nuclei. However, in the antisense group, the

cytoplasms were condensed and rounded, and the nuclei were stained

unevenly and new-moon-shaped or bulky, and contained large amounts

of decayed materials.

The results from the present study demonstrate that

the ASODN targeted against hTERT induced the death of esophageal

neoplasm cells, and inhibited the activity of telomerase, resulting

in the inhibition of cancer cell growth. The results indicate that

this ASODN effectively inhibits the growth of cancer cells and may

provide an experimental foundation for an anti-telomerase tumor

therapy. The ASODN was designed in accordance with the target-gene

sequences and base pairing; therefore, it only acted on the target

gene and had no effect on other genes within the cells. There are

numerous advantages to ASODNs, including high pertinence, high

specificity and small size. ASODNs enter the nucleus completely and

have strong anti-ribozyme activity when modified by

phosphorothioates. Therefore, this technology may have broad

applications.

References

|

1

|

Nittis T, Guittat L and Stewart SA:

Alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) and chromatin: is there

a connection? Biochimie. 90:5–12. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rao YK, Kao TY, Wu MF, Ko JL and Tzeng YM:

Identification of small molecule inhibitors of telomerase activity

through transcriptional regulation of hTERT and calcium induction

pathway in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Bioorg Med Chem.

18:6987–6994. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hiyama E and Hiyama K: Telomerase as tumor

marker. Cancer Lett. 194:221–233. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhang RG, Wang XW, Yuan JH, et al: Human

hepatoma cell telomerase activity inhibition and cell cycle

modulation by its RNA component antisense

oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 21:742–746.

2000.

|

|

5

|

Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, et al:

Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal

cells and cancer. Science. 266:2011–2015. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bellon M and Nicot C: Regulation of

telomerase and telomeres: human tumor viruses take control. J Natl

Cancer Inst. 100:98–108. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Naka K, Yokozaki H, Yasui W, Tahara H and

Tahara E and Tahara E: Effect of antisense human telomerase RNA

transfection on the growth of human gastric cancer cell lines.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 255:753–758. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mukai S, Kondo Y, Koga S, Komata T, Barna

BP and Kondo S: 2–5A antisense telomerase RNA therapy for

intracranial malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 60:4461–4467. 2000.

|

|

9

|

Jiang YA, Luo HS, Fan LF, Jiang CQ and

Chen WJ: Effect of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide of telomerase RNA

on telomerase activity and cell apoptosis in human colon cancer.

World J Gastroenterol. 10:443–445. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yuan Z and Mei HD: Inhibition of

telomerase activity with hTERT antisense increases the effect of

CDDP-induced apoptosis in myeloid leukemia. Hematol J. 3:201–205.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Folini M, Brambilla C, Villa R, et al:

Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated inhibition of hTERT, but not

hTERC, induces rapid cell growth decline and apoptosis in the

absence of telomere shortening in human prostate cancer cells. Eur

J Cancer. 41:624–634. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kraemer K, Fuessel S, Schmidt U, et al:

Antisense-mediated hTERT inhibition specifically reduces the growth

of human bladder cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 9:3794–3800.

2003.

|

|

13

|

Yu HP, Xu SQ, Lu WH, et al: Telomerase

activity and expression of telomerase genes in squamous dysplasia

and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Surg Oncol.

86:99–104. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, et al:

Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal

cells and cancer. Science. 266:2011–2015. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sekaran VG, Soares J and Jarstfer MB:

Structures of telomerase subunits provide functional insights.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1804:1190–1201. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shammas MA, Koley H, Bertheau RC, et al:

Telomerase inhibitor GRN163L inhibits myeloma cell growth in vitro

and in vivo. Leukemia. 22:1410–1418. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen Z, Koeneman KS and Corey DR:

Consequences of telomerase inhibition and combination treatments

for the proliferation of cancer cells. Cancer Res. 63:5917–5925.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kushner DM, Paranjape JM, Bandyopadhyay B,

et al: 2–5A antisense directed against telomerase RNA produces

apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 76:183–192.

2000.

|

|

19

|

Kondo Y, Koga S, Komata T and Kondo S:

Treatment of prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo with

2–5A-anti-telomerase RNA component. Oncogene. 19:2205–2211.

2000.

|

|

20

|

Fan Xang-kui, Yan Rui-Hua and Li Yi:

Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides of human telomerase inhibits

esophagus carcinoma cell Eca-109 proliferation. China Oncology.

15:88–89. 2005.

|

|

21

|

Donate LE and Blasco MA: Telomeres in

cancer and ageing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 366:76–84.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zvereva MI, Shcherbakova DM and Dontsova

OA: Telomerase: structure, functions, and activity regulation.

Biochemistry (Mosc). 75:1563–1583. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nakamura M, Masutomi K, Kyo S, et al:

Efficient inhibition of human telomerase reverse transcriptase

expression by RNA interference sensitizes cancer cells to ionizing

radiation and chemotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 16:859–868. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|