Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic metabolic disorder,

which is characterized by the formation and accumulation of lipid

plaques in the arteries and by inflammatory responses (1–4). The

main lipid-laden cells are known as foam cells and are a key

attribute of atherosclerotic lesions (2–4). In

atherosclerotic lesions, macrophages that express scavenger

receptors on their plasma membranes uptake low-density lipoprotein

(LDL) deposited into blood vessel walls, and are converted into

foam cells. Foam cells can secrete various inflammatory cytokines

and promote the development of atherosclerosis (5). Therefore, preventing foam cell

formation by decreasing cholesterol influx and increasing

cholesterol efflux may be a potential treatment strategy for

atherogenesis.

Macrophage-specific reverse cholesterol transport

(RCT) is one of the most important high density lipoprotein

(HDL)-mediated cardioprotective mechanisms (6). RCT is a process during which

cholesterol in peripheral cells is effluxed into circulating HDL

and transported back into the liver for excretion in bile and feces

(7). The cholesterol efflux from

cells to HDL is a rate-limiting step of RCT (8). The family of ATP-binding cassette (ABC)

transporters, including ABCA1 and ABCG1, has been demonstrated to

serve a critical role in the RCT pathway by promoting the

translocation of cholesterol across cellular bilayer membranes

(9,10). ABCA1 enhances the cholesterol efflux

to lipid-poor apolipoproteins, such as apolipoprotein A-I (apoAI),

while ABCG1 increases the cholesterol efflux to HDL (11). The expression levels of ABCA1 and

ABCG1 are regulated, to a certain extent, by the peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and liver X receptor α

(LXRα) (12).

Interleukin-32 (IL-32) was originally identified as

natural killer (NK) 5 transcript 4, induced by IL-18 in NK cells

(13). Due to its cytokine-like

characteristics and its critical role in inflammation, it was

renamed as IL-32 (13). IL-32 is

promoted by interferon-γ, IL-18 and IL-12 in various cell types,

such as epithelial cells. In addition, it induces the production of

various pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis

factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-8, IL-1β and IL-6, as well as of numerous

chemokines in monocytes and macrophages (13). There are six isoforms of IL-32 by

alternative splicing, namely IL-32α, IL-32β, IL32γ, IL-32δ, IL-32ε,

and IL-32ζ (13), with IL-32α being

the most abundant transcript (14).

As IL-32 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine, its effects on various

inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and

inflammatory bowel disease, have been explored (15). However, the role of IL-32 on

cholesterol efflux remains unknown. In the present study, IL-32α

was used to treat oxidized LDL (ox-LDL)-stimulated THP-1

macrophages in order to investigate the effects of IL-32α on

cholesterol efflux.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human monocyte THP-1 cell line was purchased

from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10%

(v/v) fetal calf serum, 0.1% nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C

in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. THP-1 cells were

treated with 160 nmol/l phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for

72 h and fully differentiated into macrophages. The differentiated

THP-1 macrophages were then washed extensively with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and cells were incubated in

serum-free medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 50

µg/ml human ox-LDL (Anhui Yiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Anhui,

China) for a further 48 h. All reagents for cell culture were

obtained from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham,

MA, USA). PMA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany). Recombinant human IL-32α was obtained from

R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Morphological examination

THP-1 macrophages were incubated in chamber slides

in serum-free medium (containing 0.1% BSA) with or without IL-32α

(20, 50, and 100 ng/ml) for 6 h, and then exposed to 50 µg/ml

ox-LDL for 24 h. Cells were washed with PBS for three times, fixed

with 5% formalin solution in PBS for 30 min, and stained with Oil

Red O for a further 30 min. Subsequently, cells were counterstained

with hematoxylin for 5 min. Finally, images of the stained cells

were captured using a Leica optical microscope (Leica Microsystems

GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). The number of stained cells was counted in

five random fields (magnification, ×100) for each group.

Plasmid construction

The pcDNA3.1-PPAR-γ plasmid was constructed by

inserting the human PPAR-γ cDNA (Genbank no., NM_138711.3) into a

pcDNA3.1 mammalian expression vector. The full-length cDNA sequence

was amplified using Takara Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Bio, Inc.,

Otsu, Japan), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers

used were as follows: PPAR-γ forward, 5′-GGGGGTACCATGACCATGGTTG-3′

and reverse, 5′-GGGCTCGAGCTAGTACAAGTCC-3′. Thermocycling conditions

were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed

by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 59°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 45

sec. All constructs were sequenced to ensure accuracy.

Cell transfection

THP-1 macrophages (2×106 cells/well) were seeded in

6-well plates and incubated overnight prior to transfection.

pcDNA3.1-PPAR-γ or pcDNA3.1 vector was added to each well at a

final concentration of 50 nM and was incubated with Lipofectamine

2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room

temperature for 30 min. The pcDNA3.1-transfected group served as a

negative control.

Cholesterol efflux

THP-1 macrophages were assigned to the following

groups: Untreated control, ox-LDL, ox-LDL+IL-32α, ox-LDL+15d-PGJ2,

ox-LDL+DMSO, ox-LDL+IL-32α+15d-PGJ2, and ox-LDL+IL-32α+DMSO. THP-1

macrophages were cultured until they reached 60% confluence, and

were then labeled with 0.2 µCi/ml [3H] cholesterol

(PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for 24 h. Fresh serum-free

medium with 0.1% BSA containing the PPARγ agonist 15d-PGJ2 (5 µM;

Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) or 0.1%

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added to

THP-1 macrophages for 1 h, followed by exposure to IL-32α (50

ng/ml) for a further 6 h. Ox-LDL was then added to cells and

incubated for another 24 h. Equilibrated [3H]

cholesterol-labeled cells were washed with PBS and incubated in

efflux medium [RPMI 1640 medium and 0.1% BSA with 25 µg/ml human

apoA-I (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)] for 4 h. Cells were centrifuged

at 14,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatants were then collected.

Single layer cells were dissolved in isopropanol. Medium and

cell-associated [3H] cholesterol was examined by liquid

scintillation counting. The percentage of apoA-I-mediated

cholesterol efflux was calculated as follows: Cholesterol efflux

(%)=(total media counts)/(total cellular counts + total media

counts) ×100%.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 2 µg total RNA

was used as the template for reverse transcription using a

PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) cDNA was

used as template for qPCR on the Light Cycler system (Roche

Diagnostics, Shanghai China) using SYBR-Green I Master mixture

(Roche Diagnostics). Cycling conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, then 35 cycles of denaturation at

95°C for 20 sec, annealing at 58°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C

for 50 sec. The primers used for qPCR in the present study were

synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and are listed in

Table I. β-actin was used as the

housekeeping gene control for qPCR. The threshold cycle (Cq) values

were used to calculate the fold change in transcript levels using

the 2−ΔΔCq method (16),

as follows: Fold change=2-[(Cq target-Cq β-actin) of

siRNA]-[(Cq target-Cq β-actin) of control].

| Table I.Primers for quantitative polymerase

chain reaction analysis. |

Table I.

Primers for quantitative polymerase

chain reaction analysis.

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|

| ABCA1 | Forward:

5′-AACAGTTTGTGGCCCTTTTG-3′ |

|

| Reverse:

5′-AGTTCCAGGCTGGGGTACTT-3′ |

| ABCG1 | Forward:

5′-GGTTCTTCGTCAGCTTCGAC-3′ |

|

| Reverse:

5′-GTTTCCTGGCATTCAGGTGT-3′ |

| PPARγ | Forward:

5′-GGCAATTGAATGTCGTGTCTGTGGAGATAA-3′ |

|

| Reverse:

5′-AGCTCCAGGGCTTGTAGCAGGTTGTCTTGA-3′ |

| LXRα | Forward:

5′-GCGAGGGCTGCAAGGGATTCT-3′ |

|

| Reverse:

5′-ATGGGCCAAGGCGTGACTCG-3′ |

| β-actin | Forward:

5′-TCATGAAGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGT-3′ |

|

| Reverse:

5′-CTTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGCACGATG-3′ |

Western blot assay

Ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages were washed with

PBS for three times and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 300 mM

NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 1% Triton X-100)

containing 2% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Total protein

concentrations were measured with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, 20 µg cell lysates

were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and

proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (EMD

Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5%

non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature and probed with antibodies

against ABCA1 (sc-81779; 1:500 dilution), ABCG1 (sc-20795; 1:500

dilution), PPARγ (sc-6285; 1:500 dilution), LXRα (sc-1202; 1:500

dilution) and anti-human β-actin (sc-47778; 1:1,000 dilution; all

from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in

antibody dilution buffer [5% non-fat milk in 1X Tris-buffered

saline/0.1% Tween-20 (TBST)] at 4°C overnight. Next, the membranes

were washed with TBST for three times and then incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (sc-2004;

1:2,000 dilution) or goat anti-mouse IgG (sc-2005; 1:1,000

dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at room temperature for 1

h. After washing with TBST, the membranes were subjected to an

enhanced chemiluminescence advanced system (GE Healthcare Life

Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA). β-actin was used as a loading control.

The protein bands were analyzed using Quantity One software

(version 4.6.2; Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

SPSS software version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA) was used to perform statistical analysis. Data are presented

as the means ± standard deviation of three experiments, or are

representative of experiments repeated at least three times.

Comparisons were conducted with a one-way analysis of variance and

post-hoc Tukey's tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

IL-32α induces lipid deposition in

THP-1 macrophages

The effect of IL-32α on lipid deposition in THP-1

macrophages was evaluated using Oil Red O staining. As shown in

Fig. 1, ox-LDL exposure

significantly induced lipid accumulation in THP-1 macrophages,

compared with the untreated control (P<0.05). Notably, addition

of recombinant IL-32α protein significantly induced lipid

deposition in ox-LDL-induced THP-1 macrophages in a

concentration-dependent fashion.

IL-32α reduces cholesterol efflux

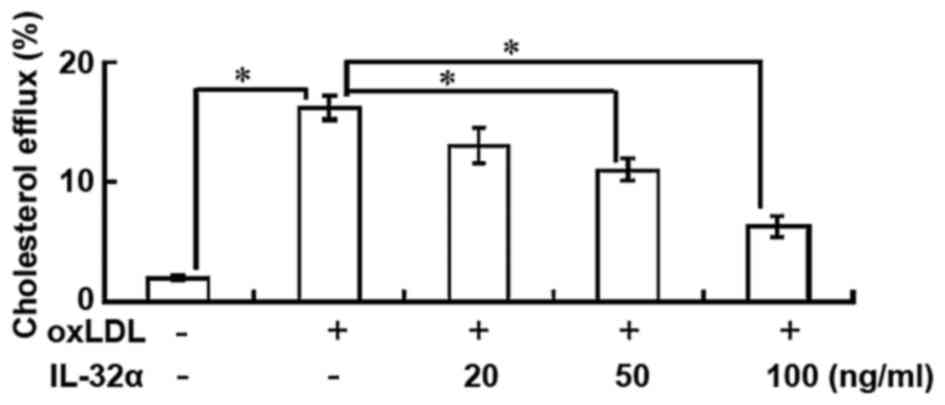

The results indicated that the percentage of

cholesterol efflux was significantly increased following ox-LDL

exposure in THP-1 macrophages (P<0.05; Fig. 2). However, IL-32α treatment

attenuated the apoA-I-mediated cholesterol efflux in a

dose-dependent manner in ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages, with

a significant effect observed for the 50 and 100 ng/ml IL-32α doses

(P<0.05; Fig. 2). This suggests

that IL-32α increased intracellular lipid accumulation by

decreasing the apoA-I-mediated cholesterol efflux.

IL-32α reduces the expression levels

of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ

The importance of ABCA1, ABCG1, LXRα and PPARγ in

apoA-I-mediated cholesterol efflux has previously been established

(13). Therefore, the present study

next analyzed the effects of IL-32α on the mRNA levels of these

molecules by RT-qPCR in ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages. The

results demonstrated that ox-LDL treatment significantly raised the

mRNA levels of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ, compared with untreated

controls (P<0.05; Fig. 3A). The

addition of 100 ng/ml IL-32α significantly decreased the mRNA

expression levels of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ by 59, 52.9 and 61.1%,

respectively, compared with the ox-LDL alone group (P<0.05;

Fig. 3A). However, the level of

ABCG1 was not affected. Subsequently, the study explored whether

the IL-32α-mediated inhibition of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ mRNA

expression led to decreased expression of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ

protein using western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 3B, IL-32α also suppressed the

expression of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ at the protein level.

| Figure 3.Effects of IL-32α on the (A) mRNA and

(B) protein expression levels of ABCA1, ABCG1, LXRα and PPARγ in

ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages, as determined by quantitative

polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis, respectively.

THP-1 macrophages were pretreated with different concentrations of

(20, 50 and 100 ng/ml) of IL-32α for 6 h, followed by incubation

with ox-LDL for 72 h. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation (n=3). *P<0.05. IL-32α, interleukin-32α; ox-LDL,

oxidized low-density lipoprotein; ABC, ATP-binding cassette

transporter; LXRα, liver X receptor α; PPARγ, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ. |

Overexpression of PPARγ rescued

IL-32α-mediated inhibition of cholesterol efflux

To evaluate the effects of PPARγ on IL-32α-mediated

inhibition of cholesterol efflux, the PPARγ agonist 15d-PGJ2 was

used to treat cells (Fig. 4A and B)

or pcDNA3.1-PPARγ (Fig. 4C and D)

was transfected to THP-1 macrophages. The 15d-PGJ2 treatment or

overexpression of PPARγ significantly enhanced cholesterol efflux

(Fig. 4A and C) and increased the

expression levels of ABCA1 and LXRα (Fig. 4B and D) in ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1

cells.

Discussion

In the present study, the effects of treatment with

IL-32α, the most abundant transcript of the pro-inflammatory

cytokine IL-32, were investigated in ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 cells.

The results revealed that IL-32α increased lipid deposition and

dose-dependently decreased the cholesterol efflux from

ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages. In addition, IL-32α attenuated

the expression levels of ABCA1, LXRα and PPARγ. To determine the

mechanism of IL-32α-mediated inhibition of cholesterol efflux,

PPARγ overexpression was performed in THP-1 macrophages by

transfection. PPARγ overexpression abrogated the IL-32α-mediated

inhibition of cholesterol efflux and reversed the IL-32α-mediated

downregulation of ABCA1 and LXRα. Thus, it was demonstrated that

IL-32α inhibits the cholesterol efflux from ox-LDL-exposed THP-1

macrophages by regulating the PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway.

IL-32 was identified as NK cell transcript 4 (NK4),

since it was selectively expressed in activated T cells or NK cells

(17). The biological role of IL-32

remained unclear until 2005, when Kim et al (13) demonstrated that recombinant NK4 was

able to induce several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α

and IL-8. Therefore, NK4 was renamed to IL-32. The IL-32 gene has

six splice variants, including IL-32α, IL-32β, IL32γ, IL-32δ,

IL-32ε, and IL-32ζ (18), with

IL-32α being the most abundant transcript (14). IL-32 can induce a range of

pro-inflammatory mediators and contribute to autoimmune diseases,

such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease

(19). Inflammation serves an

important role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis

and immune disease (20). A range of

immune cells, such as macrophages and T-lymphocytes, orchestrate

the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis through the action of

various cytokines (21). However,

the effects of IL-32α as an inflammatory cytokine in

atherosclerosis remain unknown. The present study investigated the

effects of IL-32α on lipid deposition and cholesterol efflux. As

expected, IL-32α enhanced lipid deposition and inhibited

cholesterol efflux in ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages, which

simulated a foam cell formation model.

ABCA1 and ABCG1 are integral participants in

cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport (21). To investigate the mechanism of the

IL-32α-mediated negative effects on cholesterol efflux, western

blot analysis was conducted in the present study to explore the

protein expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1. The results showed that

IL-32α inhibited the expression of ABCA1, but did not affect the

expression of ABCG1, indicating that IL-32α inhibits cholesterol

efflux through the ABCA1 signaling pathway. PPARγ and LXRα are

nuclear receptors that serve a pivotal role in macrophage

cholesterol homeostasis and inflammation (22). Western blot analysis in the current

study demonstrated that IL-32α attenuated the expression levels of

PPARγ and LXRα. These results indicate that IL-32α may inhibit

cholesterol efflux through the PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 signaling

pathway.

Inflammatory cytokines are involved in all stages of

atherosclerosis and have a profound influence on the pathogenesis

of atherosclerosis, including cholesterol efflux. IL-6 and TNF-α

inhibit cholesterol efflux by suppressing ABCA1 expression

(23). IL-1β has been demonstrated

to promote lipid accumulation and inhibit cholesterol efflux in

human mesangial cells by dysregulating the expression of

lipoprotein receptors, thus inhibiting cholesterol efflux through

the PPAR-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway (24).

Furthermore, PPARγ agonists protect mesangial cells from

IL-1β-induced intracellular lipid accumulation by activating the

ABCA1 cholesterol efflux pathway (24). To further investigate the role of

PPARγ on IL-32α-meidated inhibition of cholesterol efflux, the

present study demonstrated that the PPARγ agonist 15d-PGJ2 and

PPARγ overexpression through transfection enhanced cholesterol

efflux in ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages. These findings

indicate that inhibition of PPARγ serves an important role in

IL-32α-mediated suppression of cholesterol efflux.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

IL-32α promotes lipid deposition and inhibits cholesterol efflux

through the suppression of PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 signaling pathway in

ox-LDL-stimulated THP-1 macrophages. However, the role of other

isoforms exclusive of IL-32α in cholesterol efflux remains unknown.

Therefore, more studies are required to determine the function of

each IL-32 isoform in lipid accumulation and cholesterol

efflux.

References

|

1

|

Detmers PA, Hernandez M, Mudgett J,

Hassing H, Burton C, Mundt S, Chun S, Fletcher D, Card DJ, Lisnock

J, et al: Deficiency in inducible nitric oxide synthase results in

reduced atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J

Immunol. 165:3430–3435. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Schmitz G, Kaminski WE, Porsch-Ozcürümez

M, Klucken J, Orsó E, Bodzioch M, Büchler C and Drobnik W:

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) in macrophages: A dual

function in inflammation and lipid metabolism? Pathobiology.

67:236–240. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bodzioch M, Orsó E, Klucken J, Langmann T,

Böttcher A, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Barlage S, Büchler C,

Porsch-Ozcürümez M, et al: The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette

transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat Genet. 22:347–351.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Glass CK and Witztum JL: Atherosclerosis.

The road ahead. Cell. 104:503–516. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yu XH, Fu YC, Zhang DW, Yin K and Tang CK:

Foam cells in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 424:245–252. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Favari E, Zimetti F, Bortnick AE, Adorni

MP, Zanotti I, Canavesi M and Bernini F: Impaired ATP-binding

cassette transporter A1-mediated sterol efflux from oxidized

LDL-loaded macrophages. FEBS Lett. 579:6537–6542. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Berrougui H, Ikhlef S and Khalil A: Extra

virgin olive oil polyphenols promote cholesterol efflux and improve

HDL functionality. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2015:2080622015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Escolà-Gil JC, Llaverias G, Julve J,

Jauhiainen M, Méndez-González J and Blanco-Vaca F: The cholesterol

content of Western diets plays a major role in the paradoxical

increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and upregulates

the macrophage reverse cholesterol transport pathway. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 31:2493–2499. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhao GJ, Yin K, Fu YC and Tang CK: The

interaction of ApoA-I and ABCA1 triggers signal transduction

pathways to mediate efflux of cellular lipids. Mol Med. 18:149–158.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lee JY, Karwatsky J, Ma L and Zha X: ABCA1

increases extracellular ATP to mediate cholesterol efflux to

ApoA-I. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 301:C886–C894. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ji A, Wroblewski JM, Cai L, de Beer MC,

Webb NR and van der Westhuyzen DR: Nascent HDL formation in

hepatocytes and role of ABCA1, ABCG1, and SR-BI. J Lipid Res.

53:446–455. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chawla A, Boisvert WA, Lee CH, Laffitte

BA, Barak Y, Joseph SB, Liao D, Nagy L, Edwards PA, Curtiss LK, et

al: A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in

cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 7:161–171. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kim SH, Han SY, Azam T, Yoon DY and

Dinarello CA: Interleukin-32: A cytokine and inducer of TNFalpha.

Immunity. 22:131–142. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Choi JD, Bae SY, Hong JW, Azam T,

Dinarello CA, Her E, Choi WS, Kim BK, Lee CK, Yoon DY, et al:

Identification of the most active interleukin-32 isoform.

Immunology. 126:535–542. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cheon S, Lee JH, Park S, Bang SI, Lee WJ,

Yoon DY, Yoon SS, Kim T, Min H, Cho BJ, et al: Overexpression of

IL-32alpha increases natural killer cell-mediated killing through

up-regulation of Fas and UL16-binding protein 2 (ULBP2) expression

in human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem.

286:12049–12055. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Goda C, Kanaji T, Kanaji S, Tanaka G,

Arima K, Ohno S and Izuhara K: Involvement of IL-32 in

activation-induced cell death in T cells. Int Immunol. 18:233–240.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim S: interleukin-32 in inflammatory

autoimmune diseases. Immune Netw. 14:123–127. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Conti P and Shaik-Dasthagirisaeb Y:

Atherosclerosis: A chronic inflammatory disease mediated by mast

cells. Cent Eur J Immunol. 40:380–386. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Buckley ML and Ramji DP: The influence of

dysfunctional signaling and lipid homeostasis in mediating the

inflammatory responses during atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1852:1498–1510. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Majdalawieh A and Ro HS: PPARgamma1 and

LXRalpha face a new regulator of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis

and inflammatory responsiveness, AEBP1. Nucl Recept Signal.

8:e0042010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ramji DP and Davies TS: Cytokines in

atherosclerosis: Key players in all stages of disease and promising

therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 26:673–685. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang N, Lei J, Lei H, Ruan X, Liu Q, Chen

Y and Huang W: MicroRNA-101 overexpression by IL-6 and TNF-α

inhibits cholesterol efflux by suppressing ATP-binding cassette

transporter A1 expression. Exp Cell Res. 336:33–42. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ruan XZ, Moorhead JF, Fernando R, Wheeler

DC, Powis SH and Varghese Z: PPAR agonists protect mesangial cells

from interleukin 1beta-induced intracellular lipid accumulation by

activating the ABCA1 cholesterol efflux pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol.

14:593–600. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|