Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased

risk of ischemic cardiovascular diseases, including coronary heart

disease and stroke, which seriously jeopardize human health

(1). The mechanism of this

association is complicated. Vascular injury, occlusion or

degradation caused by endothelial dysfunction in hyperglycemia may

serve an important role. Accumulating evidence suggests that

circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) can promote

reendothelialization and restore endothelial function (2,3).

Nevertheless, the number of EPCs is decreased in type I and type II

diabetes (4,5). In addition, EPC functions, such as

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis, are severely suppressed

in diabetes (6,7). Therefore, ameliorating the impaired

functions of EPCs is urgent and critical for EPC-based cell

therapy, particularly with regard to ischemic cardiovascular

disease associated with diabetes.

Thymosin β4 (Tβ4) is a pleiotropic peptide serving

various roles in cell migration (8,9),

angiogenesis (10), apoptosis

(11) and inflammation (12). Recent studies have suggested that Tβ4

can exert cardiovascular protective effects by enhancing the

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of a variety of stem or

progenitor cells (9,13–15).

Previous studies by the authors of the present study demonstrated

that Tβ4 could promote EPC migration, prevent EPCs from serum

deprivation-induced apoptosis and reduce the senescence of EPCs

in vitro (11,16,17).

However, whether Tβ4 can improve glucose-impaired EPC function, and

the underlying mechanism associated with this, remain unclear. In

there present study, the effect of Tβ4 on glucose-impaired EPC

function is investigated, and the potential signaling pathway

involved is discussed.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Mononuclear cells were isolated from the peripheral

blood of healthy donors by density-gradient centrifugation using

Ficoll separating solution (Cedarlane Laboratories, Ltd., Hornby,

Canada). Then, 1×107 mononuclear cells were plated on

fibronectin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA)-coated plates and

incubated with endothelial growth medium-2 (EGM-2 MV; Clonetics,

Walkersville, MD, USA). After 3 days of culturing, non-adherent

cells were removed by washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS;

0.2 M, pH 7.4) and new medium was applied. A number of cells grew

into EPCs which exhibited a ‘cobblestone’ shape after 3–4 weeks.

The EPCs were detached by trypsin and collected for the following

experiments.

EPC migration assay

EPC migration was assessed using a transwell

migration assay (3422; Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). A total of

5×104 cells were re-suspended in 100 µl serum-free

endothelial basal medium-2 (EBM-2; Clonetics) and placed in the

upper chambers of 24-well transwell plates with 8 µm-pore

membranes. Then, 600 µl EGM-2 supplemented with 10% bovine serum

albumin (Amresco LLC, Solon, OH, USA) was placed in lower chambers.

After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, the upper side of membrane was

wiped gently with cotton swabs to remove the cells that had not

migrated. The migrated cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and

stained using 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Roche Applied Science,

Indianapolis, IN, USA). Migrated cells were counted with a

fluorescence microscope at ×400 magnification and 5 random fields

were picked for counting. The average cell number of these 5 fields

was considered as the cell migration number for each group.

EPC tube formation assay

Tube formation was performed with Matrigel matrix

basement membrane (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to

evaluate the ability of EPC angiogenesis. Matrigel solution was

thawed at 4°C overnight, diluted with EBM-2 and added in a 96-well

plate at 37°C for 1 h to solidify. EPCs were collected with trypsin

and re-suspended with EGM-2 MV medium, then 2×104 EPCs

were placed on the matrix for further incubation at 37°C for 6–8 h.

Tube formation was observed with a light microscope (magnification,

×100) and 5 random fields were chosen for each assay. The average

tube formation counted by branch point numbers was compared in

different groups by Image Pro Plus version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics,

Warrendale, PA, USA).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

siRNA against Akt and eNOS were synthesized by

GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and a nonsense sequence was

designed as a negative control. The effective Akt siRNA sequence

was as follows: Sense, 5′-GCACUUUCGGCAAGGUGAUTT-3′ and antisense,

5′-AUCACCUUGCCGAAAGUGCTT-3′. The effective eNOS siRNA sequence was

as follows: Sense, 5′-CAGUACUACAGCUCCAUUATT-3′ and antisense,

5′-UAAUGGAGCUGUAGUACUGTT-3′. Then, 4×105 EPCs were

placed in 6-well plates, and when cells reached 60–80% confluence,

they were transfected with Akt and eNOS siRNA and cultured for 24

h, then incubated with a high concentration of glucose (25 mM) for

4 days (except for the control group), and with or without Tβ4

(ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene, Ltd., Rehovot, Israel) for the last 24 h.

The effectiveness of Akt and eNOS knock-down was determined by

western blotting.

Western blots analysis and measurement

of nitric oxide (NO)

Total protein from EPCs was extracted with

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Protein concentration was measured

using a BCA assay kit (P0012; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Equal quantities of protein (20 µg) were run on a 10% tris-glycine

gradient gel, then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride

membranes and blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered

solution containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at 25°C. Membranes

were then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight and

with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1–2 h. Membranes

were washed three times with TBST for 15 min before and after the

incubations. Finally, proteins were visualized with enhanced

chemiluminescence reagent (Lianke Biotechnology, Hangzhou, China)

and exposed to Image Quant LAS-4000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Grayscale of the bands were measured by Multi-Gauge 3.0 image

analysis software (Fujifilm). Antibodies including

anti-phospho-Akt-Ser473 (1:1,000; 3787), anti-Akt

(1:1,000; 9272), anti-phospho-endothelial nitric oxide synthase

(eNOS)-Ser1177 (1:1,000; 9571), anti-eNOS (1:1,000;

9572) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

(1:5,000; 7074) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

(Beverly, MA, USA). After incubation of EPCs with or without Tβ4 in

glucose for 4 days, the conditioned medium was examined for NO

using Griess regent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed for at least three

individual experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using

SPSS version 19.0 software (IBM SPSS, Amronk, NY, USA), using

one-way analysis of variance nad post-hoc least standard difference

analysis. Results are presented as the mean ± standard error.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

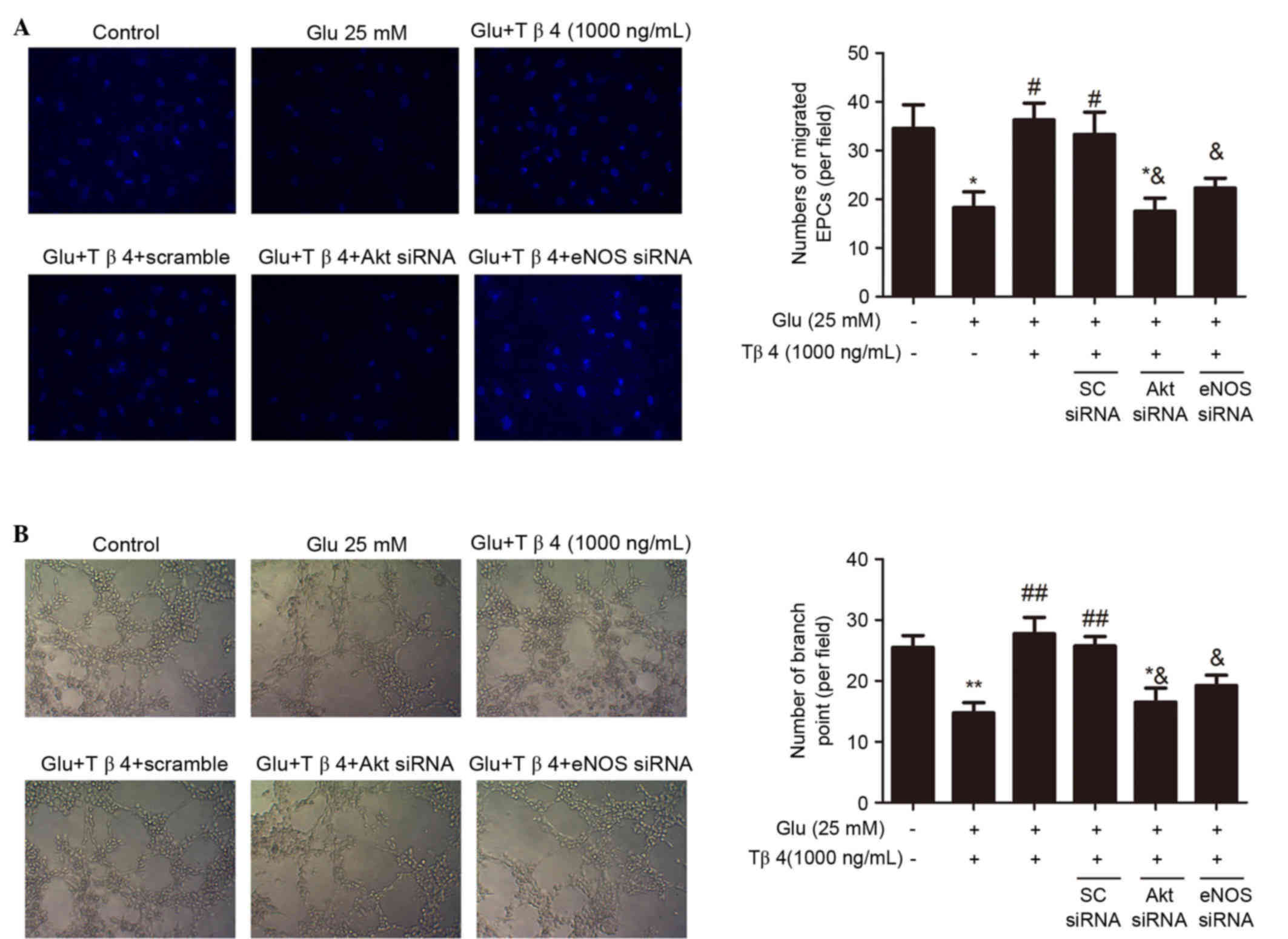

Tβ4 ameliorates glucose-impaired EPC

migration and angiogenesis

It was investigated whether the administration of

Tβ4 could improve glucose-impaired EPC functions. As shown in

Fig. 1A, incubation of EPCs with

medium with a high concentration of glucose (25 mM) for 4 days

could significantly suppress EPC migration (P<0.01 vs. the

control group). However, treatment with Tβ4 for 24 h after the

exposure of EPCs to high glucose conditions could improve

glucose-suppressed EPC migration in a concentration-dependent

manner; the maximal pro-migratory dose was observed at 1,000 ng/ml

(P<0.01 vs. the glucose group; Fig.

1A). In addition, high concentrations of glucose significantly

impaired EPC tube formation ability (P<0.01 vs. the control

group; Fig. 1B). Treatment with Tβ4

for 24 h after glucose exposure ameliorated glucose-suppressed EPC

tube formation ability in a concentration-dependent manner; the

maximal pro-angiogenic dose was observed at 1,000 ng/ml (P<0.01

vs. the glucose group; Fig. 1B).

Tβ4 restores glucose-inhibited

Akt/eNOS phosphorylation and NO production

High concentrations of glucose can inhibit Akt and

eNOS activation and reduce NO production in EPCs (18). A previous study indicated that Tβ4

may activate the phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS (16,17).

Therefore, the effects of Tβ4 on glucose-exposed EPCs were

investigated in order to determine whether Tβ4 can restore

glucose-inhibited Akt and eNOS phosphorylation in EPCs. As shown in

Fig. 2A, high concentrations of

glucose (25 mM) dramatically down-regulated the phosphorylation of

Akt at Ser473 and eNOS at Ser1177 in EPCs,

while there was no significant change in total Akt and eNOS

expression. The inhibition of eNOS phosphorylation led to reduced

NO production of EPCs (Fig. 2B).

However, administration of Tβ4 in the glucose medium for 24 h

concentration-dependently upregulated the phosphorylation of Akt

and eNOS, and augmented NO production (Fig. 2).

Akt/eNOS signaling pathway is involved

in the amelioration of glucose-impaired EPC functions by Tβ4

To identify the role of the Akt/eNOS signaling

pathway in the beneficial effect of Tβ4 on glucose-impaired EPC

functions, EPCs were transfected with Akt siRNA and eNOS siRNA to

decrease Akt and eNOS activity, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, administration of Akt and eNOS siRNA

(50 nM) markedly inhibited the benefit of Tβ4 in improving EPC

migration and tube formation, suggesting that the Akt/eNOS pathway

accounts for Tβ4-induced improvement of glucose-suppressed EPC

functions.

Discussion

Previous studies performed by the authors of the

present study have demonstrated that Tβ4 may exert an important

role in enhancing EPC functions, including promoting migration,

inhibiting apoptosis and senescence (11,16,17).

However, the capacity of Tβ4 to reverse impaired EPC functions in

some pathological conditions remains unclear. The present study

demonstrated that Tβ4 could reverse glucose-impaired EPC functions

in a dose-dependent manner and elucidated that the beneficial

effect of Tβ4 may be associated with the Akt/eNOS signaling pathway

and NO-related mechanisms.

At present, diabetes mellitus has become a common

diseases worldwide, which is associated with poor clinical outcomes

and premature morality due to its cardiovascular complications

(19,20). Several studies have suggested that

the imbalance between endothelial injury and repair is a key

process of diabetes-associated cardiovascular complications

(21,22). Endothelial function is impaired in

diabetes and the complication of vascular occlusion in diabetic

patients has been attributed to compromised collateral vessel

formation due to diminished capacity of mature endothelial cells

(1). EPCs have proliferating

potential, differentiating into endothelial cells and promoting

regeneration and angiogenesis of endothelial cells, which serves an

important role in maintaining endothelial function and integrity,

as well as post-natal neovascularization (23). Interestingly, emerging evidence has

showed that post-natal neovascularization in adults may be involved

with EPCs directly (24). Hence,

EPCs could be a potential method for cardiovascular therapy.

However, it has been revealed that the number and function of EPCs

may be reduced by several cardiovascular risk factors, such as

hypertension, hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia (25). Reduced numbers and suppressed

function of EPCs can be associated with endothelial dysfunction,

impaired angiogenesis and decreased compensational

collateralization in occlusive vascular diseases (26). Type I and type II diabetes are both

associated with decreased numbers and impaired function of EPCs.

Therefore, strategies to improve the suppressed functions of EPCs

is critical and beneficial for EPC-based cell therapy, particularly

in treating diabetic patients.

In our present study, the functions of circulating

EPCs is suppressed in high concentrations of glucose, and Tβ4 was

demonstrated to reverse the dysfunction of EPCs. Tβ4 is a

polypeptide originally isolated from calf thymus (27). Previous studies have observed that

Tβ4 can modulate various physiological and pathological process,

such as tissue development, wound healing, cell survival and vessel

formation (10,28–30).

Previous studies by the authors of the present study have

demonstrated that Tβ4 was able to enhance EPC migration, inhibit

EPC apoptosis and senescence in vitro (11,16). In

addition, Tβ4 has been reported to enhance the angiogenesis of

endothelial cells (31).

Furthermore, Tβ4 exerts excellent therapeutic effects against

glucose damage. Tβ4 is able to abolish glucose-suppressed

capillary-like tube formation of endothelial cells and promote the

recovery of neurological function in diabetic peripheral neuropathy

(32). Kim and Kwon found that Tβ4

could ameliorate glucose-injured high-glucose-injured human

umbilical vein endothelial cell function through the insulin-like

growth factor-1 signaling pathway (33). According to the evidence above, the

present study further revealed the beneficial effects of Tβ4 on

human EPCs in high concentrations of glucose, which may provide

novel insights into its potential application for cardiovascular

protection and therapy in clinical cases.

The Akt/eNOS signaling pathway has been reported to

be a critical pathway that regulates cell migration and

angiogenesis (34). As for EPCs,

previous research has demonstrated that exercise and some

medications, such as statins, could increase EPC number,

proliferation and migration through the activation of the Akt

protein (35). The stimulation of

Akt protein kinase can further activate eNOS (36), which is essential and pivotal for the

mobilization of stem and progenitor cells (37). A number of studies documented that

hyperglycemia could affect various functions of different kinds of

cells through the Akt/eNOS signaling pathway. Sun et al

(38) identified that vaspin, a type

of adipose factor, could alleviate EPC dysfunction caused by high

concentrations of glucose via the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway.

Chen et al (18) indicated

that high concentrations of glucose impaired EPC proliferation,

migration and angiogenesis by down-regulating the phosphorylation

Akt and eNOS, and NO production (18). The authors of the present study have

previously revealed that Tβ4 promotes EPC migration and inhibits

EPC apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway (11,16),

therefore, it was postulated that this pathway may account for the

Tβ4-mediated improvement of glucose-suppressed EPC functions.

In present study, it was demonstrated that treatment

with Tβ4 could provoke Akt and eNOS activity, and enhance the

migration and tube formation of EPCs in high concentrations of

glucose. These beneficial effects were blocked by the siRNA of Akt

and eNOS. These findings suggest that Tβ4 can ameliorate

glucose-impaired EPC functions through the Akt/eNOS signaling

pathway. According the findings above, Tβ4 may be beneficial for

maintaining EPC functions in high concentrations of glucose, which

is helpful for understanding the therapeutic potential of Tβ4 for

patients with diabetes and cardiovascular complications.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Special Major

Projects of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2010C13027) and the

National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant nos. 81200112

and 81200114).

References

|

1

|

Abaci A, Oğuzhan A, Kahraman S, Eryol NK,

Unal S, Arinç H and Ergin A: Effect of diabetes mellitus on

formation of coronary collateral vessels. Circulation.

99:2239–2242. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fujiyama S, Amano K, Uehira K, Yoshida M,

Nishiwaki Y, Nozawa Y, Jin D, Takai S, Miyazaki M, Egashira K, et

al: Bone marrow monocyte lineage cells adhere on injured

endothelium in a monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-dependent

manner and accelerate reendothelialization as endothelial

progenitor cells. Circ Res. 93:980–989. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Werner N, Priller J, Laufs U, Endres M,

Böhm M, Dirnagl U and Nickenig G: Bone marrow-derived progenitor

cells modulate vascular reendothelialization and neointimal

formation: Effect of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a

reductase inhibition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 22:1567–1572.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Loomans CJ, de Koning EJ, Staal FJ,

Rookmaaker MB, Verseyden C, de Boer HC, Verhaar MC, Braam B,

Rabelink TJ and van Zonneveld AJ: Endothelial progenitor cell

dysfunction: A novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular

complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 53:195–199. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fadini GP, Miorin M, Facco M, Bonamico S,

Baesso I, Grego F, Menegolo M, de Kreutzenberg SV, Tiengo A,

Agostini C and Avogaro A: Circulating endothelial progenitor cells

are reduced in peripheral vascular complications of type 2 diabetes

mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 45:1449–1457. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ingram DA, Lien IZ, Mead LE, Estes M,

Prater DN, Derr-Yellin E, DiMeglio LA and Haneline LS: In vitro

hyperglycemia or a diabetic intrauterine environment reduces

neonatal endothelial colony-forming cell numbers and function.

Diabetes. 57:724–731. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM, Kalka C,

Gagne PJ, Jacobowitz GR, Levine JP and Gurtner GC: Human

endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit

impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular

structures. Circulation. 106:2781–2786. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Malinda KM, Goldstein AL and Kleinman HK:

Thymosin beta 4 stimulates directional migration of human umbilical

vein endothelial cells. FASEB J. 11:474–481. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Smart N, Risebro CA, Melville AA, Moses K,

Schwartz RJ, Chien KR and Riley PR: Thymosin beta4 induces adult

epicardial progenitor mobilization and neovascularization. Nature.

445:177–182. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Grant DS, Rose W, Yaen C, Goldstein A,

Martinez J and Kleinman H: Thymosin beta4 enhances endothelial cell

differentiation and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 3:125–135. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao Y, Qiu F, Xu S, Yu L and Fu G:

Thymosin β4 activates integrin-linked kinase and decreases

endothelial progenitor cells apoptosis under serum deprivation. J

Cell Physiol. 226:2798–2806. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sosne G, Szliter EA, Barrett R, Kernacki

KA, Kleinman H and Hazlett LD: Thymosin beta 4 promotes corneal

wound healing and decreases inflammation in vivo following alkali

injury. Exp Eye Res. 74:293–299. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Riley PR and Smart N: Thymosin beta4

induces epicardium-derived neovascularization in the adult heart.

Biochem Soc Trans. 37:1218–1220. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bock-Marquette I, Saxena A, White MD,

Dimaio JM and Srivastava D: Thymosin beta4 activates

integrin-linked kinase and promotes cardiac cell migration,

survival and cardiac repair. Nature. 432:466–472. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bock-Marquette I, Shrivastava S, Pipes GC,

Thatcher JE, Blystone A, Shelton JM, Galindo CL, Melegh B,

Srivastava D, Olson EN and DiMaio JM: Thymosin beta4 mediated PKC

activation is essential to initiate the embryonic coronary

developmental program and epicardial progenitor cell activation in

adult mice in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 46:728–738. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Qiu FY, Song XX, Zheng H, Zhao YB and Fu

GS: Thymosin beta4 induces endothelial progenitor cell migration

via PI3K/Akt/eNOS signal transduction pathway. J Cardiovasc

Pharmacol. 53:209–214. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li J, Yu L, Zhao Y, Fu G and Zhou B:

Thymosin β4 reduces senescence of endothelial progenitor cells via

the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signal transduction pathway. Mol Med Rep.

7:598–602. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen YH, Lin SJ, Lin FY, Wu TC, Tsao CR,

Huang PH, Liu PL, Chen YL and Chen JW: High glucose impairs early

and late endothelial progenitor cells by modifying nitric

oxide-related but not oxidative stress-mediated mechanisms.

Diabetes. 56:1559–1568. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bitzur R: Diabetes and cardiovascular

disease: When it comes to lipids, statins are all you need.

Diabetes Care. 34 Suppl 2:S380–S382. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bloomgarden ZT: Diabetes and

cardiovascular disease. Diabetes care. 34:e24–e30. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tabit CE, Chung WB, Hamburg NM and Vita

JA: Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: Molecular

mechanisms and clinical implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord.

11:61–74. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH,

Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA and Finkel T: Circulating endothelial

progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N

Engl J Med. 348:593–600. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rafii S and Lyden D: Therapeutic stem and

progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and

regeneration. Nat Med. 9:702–712. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver

M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G and Isner JM:

Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for

angiogenesis. Science. 275:964–967. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, Adler

K, Urbich C, Martin H, Zeiher AM and Dimmeler S: Number and

migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells

inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease.

Circ Res. 89:E1–E7. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Landmesser U, Engberding N, Bahlmann FH,

Schaefer A, Wiencke A, Heineke A, Spiekermann S, Hilfiker-Kleiner

D, Templin C, Kotlarz D, et al: Statin-induced improvement of

endothelial progenitor cell mobilization, myocardial

neovascularization, left ventricular function, and survival after

experimental myocardial infarction requires endothelial nitric

oxide synthase. Circulation. 110:1933–1939. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Klein JJ, Goldstein AL and White A:

Enhancement of in vivo incorporation of labeled precursors into DNA

and Total protein of mouse lymph nodes after administration of

thymic extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 53:812–817. 1965.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Rossdeutsch A, Smart N, Dube KN, Turner M

and Riley PR: Essential role for thymosin beta4 in regulating

vascular smooth muscle cell development and vessel wall stability.

Circ Res. 111:e89–e102. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kaur H and Mutus B: Platelet function and

thymosin beta 4. Biol Chem. 393:595–598. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Malinda KM, Sidhu GS, Mani H, Banaudha K,

Maheshwari RK, Goldstein AL and Kleinman HK: Thymosin beta 4

accelerates wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 113:364–368. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lv S, Cheng G, Zhou Y and Xu G: Thymosin

beta4 induces angiogenesis through Notch signaling in endothelial

cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 381:283–290. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang L, Chopp M, Szalad A, Liu Z, Lu M,

Zhang L, Zhang J, Zhang RL, Morris D and Zhang ZG: Thymosin beta4

promotes the recovery of peripheral neuropathy in type II diabetic

mice. Neurobiol Dis. 48:546–555. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kim S and Kwon J: Effect of thymosin beta

4 in the presence of up-regulation of the insulin-like growth

factor-1 signaling pathway on high-glucose-exposed vascular

endothelial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 401:238–247. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Everaert BR, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Hoymans

VY, Haine SE, Van Nassauw L, Conraads VM, Timmermans JP and Vrints

CJ: Current perspective of pathophysiological and interventional

effects on endothelial progenitor cell biology: Focus on

PI3K/AKT/eNOS pathway. Int J Cardiol. 144:350–366. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, Mildner-Rihm

C, Adler K, Tiemann M, Rütten H, Fichtlscherer S, Martin H and

Zeiher AM: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase

endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J

Clin Invest. 108:391–397. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana

J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A and Sessa WC:

Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the

protein kinase Akt. Nature. 399:597–601. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Aicher A, Heeschen C, Mildner-Rihm C,

Urbich C, Ihling C, Technau-Ihling K, Zeiher AM and Dimmeler S:

Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for

mobilization of stem and progenitor cells. Nat Med. 9:1370–1376.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sun N, Wang H and Wang L: Vaspin

alleviates dysfunction of endothelial progenitor cells induced by

high glucose via pi3k/Akt/eNOS pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol.

8:482–489. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|