Introduction

Although endobronchial metastasis is rare, colon,

kidney and breast cancer are three of the malignancies that can

develop endobronchial metastasis (1,2). A

range of conditions, including non-malignant tumors, primary lung

carcinoma and endobronchial metastasis of carcinoma from

extra-pulmonary organs, may form part of the differential diagnosis

of endobronchial lesions in the clinic (3–8).

Superficial-type endobronchial metastasis arising from

extrathoracic tumors is extremely rare and thus, the incidence

remains unknown. To prevent bleeding and airway obstruction caused

by endobronchial metastasis, irradiation and photodynamic therapy

have been proposed, however, a standard therapy has not yet been

established due to its rarity and the outcome of this type of

endobronchial metastasis from colorectal cancer has not been

previously reported. The present study reports the case of a

patient with superficial-type endobronchial metastases in the

bronchi, which were unexpectedly found by bronchoscopic

examination. Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient.

Case report

A 76-year-old male was referred to the Mito Medical

Center (Mito, Japan) due to a two-month history of vomiting and a

loss of body weight. Eight years previously, the patient had

undergone a surgical resection for colon cancer. Upon admission,

the laboratory examination revealed a hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dl

(normal range, 13–16 g/dl), a hematocrit level of 36.2% (normal

range, 40–52%) and a C-reactive protein count of 1.11 g/dl (normal

range, ≤0.5 m/dl). The serum level of carcinoembryonic antigen was

elevated to 35.1 ng/ml (normal range, ≤5.0 ng/ml). A physical

examination revealed right subclavian lymph node swelling, which

was pathologically proven to be lymph node metastasis from colon

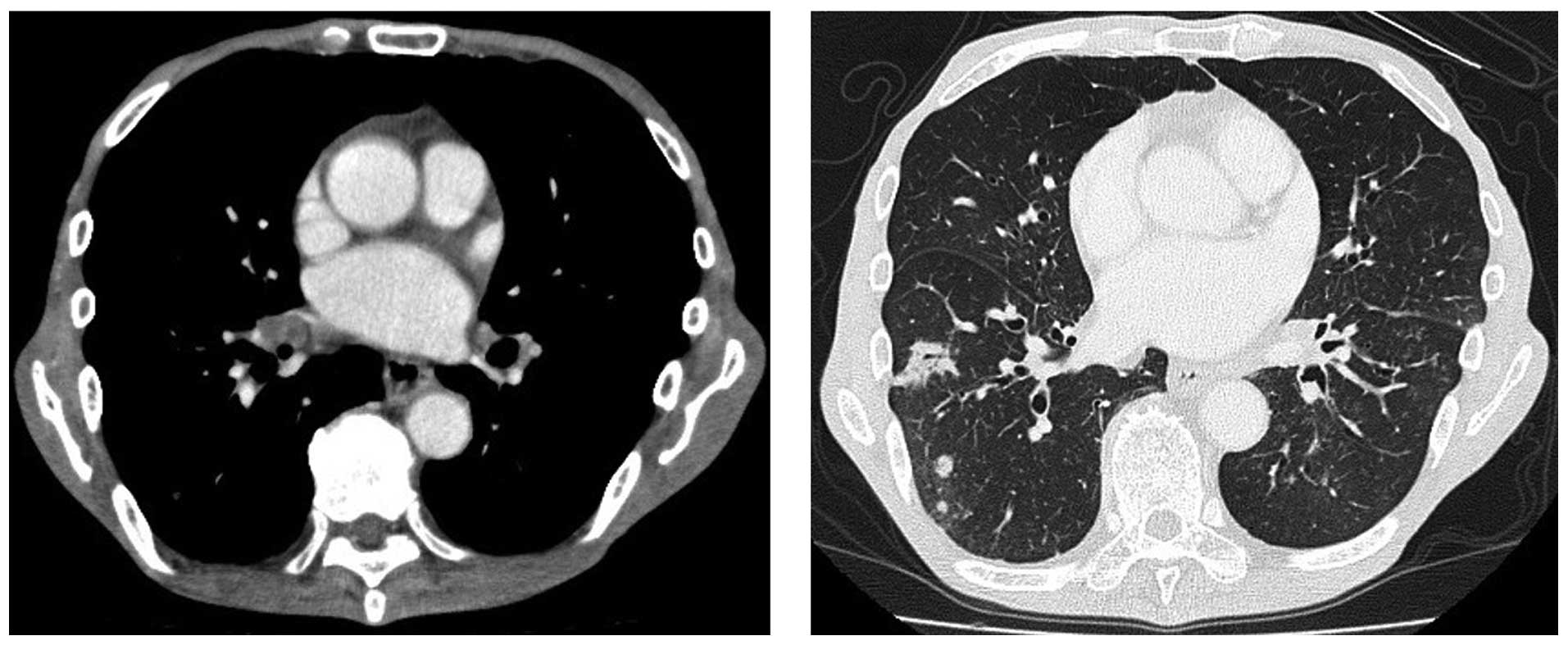

cancer. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed multiple

metastatic tumors in the liver. X-ray and CT of the chest revealed

small masses in the lungs, with bilateral hilar lymph node swelling

(Fig. 1). As these pulmonary

lesions were observed, bronchoscopy was performed to obtain

pathological specimens and to confirm that these lesions were

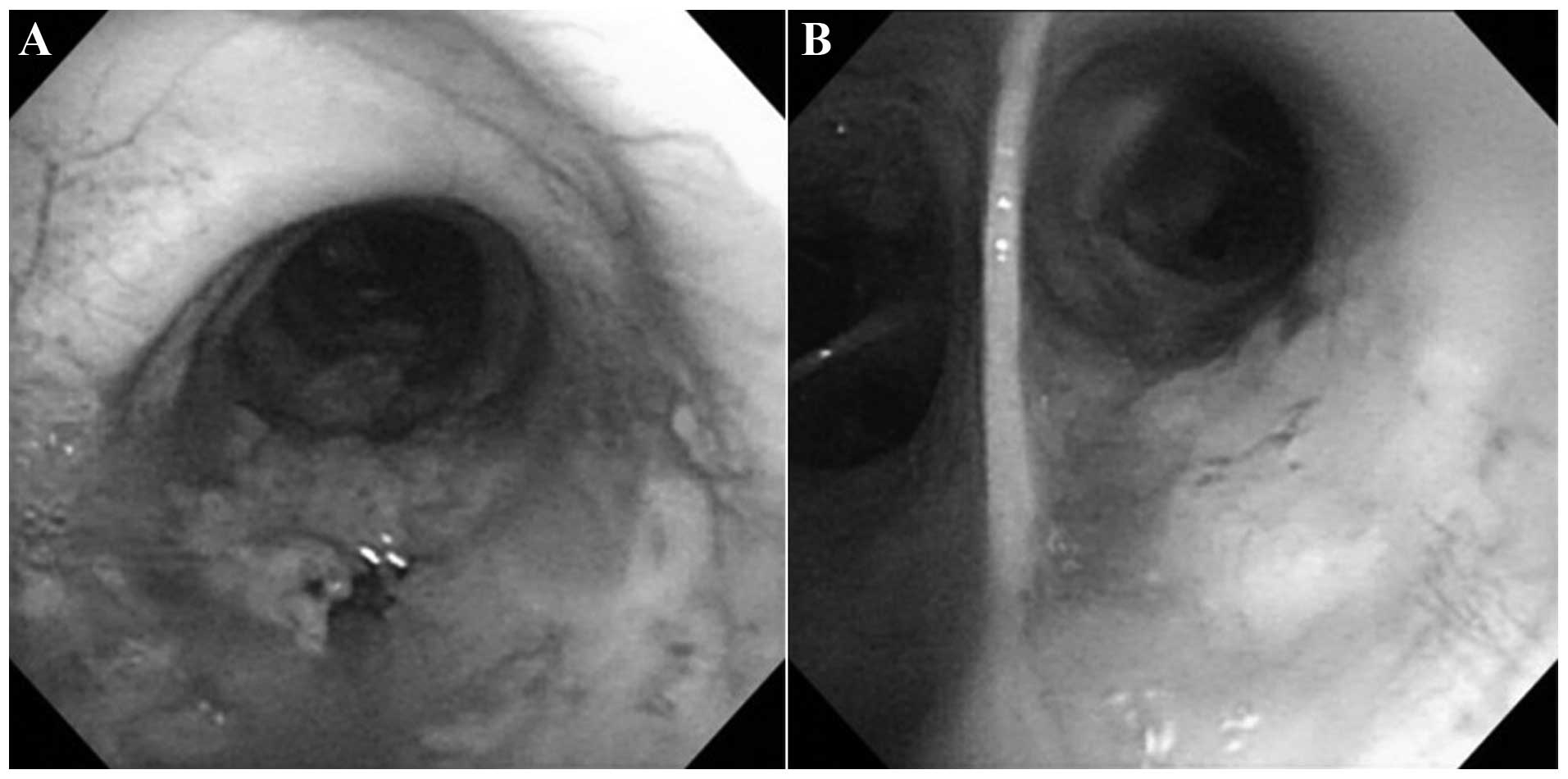

metastatic tumors from colon cancer. Bronchoscopy revealed

unexpected superficial endobronchial tumors in the two bronchi

(Fig. 2), which were white and

marginally elevated flat lesions with irregular margins. No

necrotic tissue was identified, however, the development of small

blood vessels surrounding the lesions was observed.

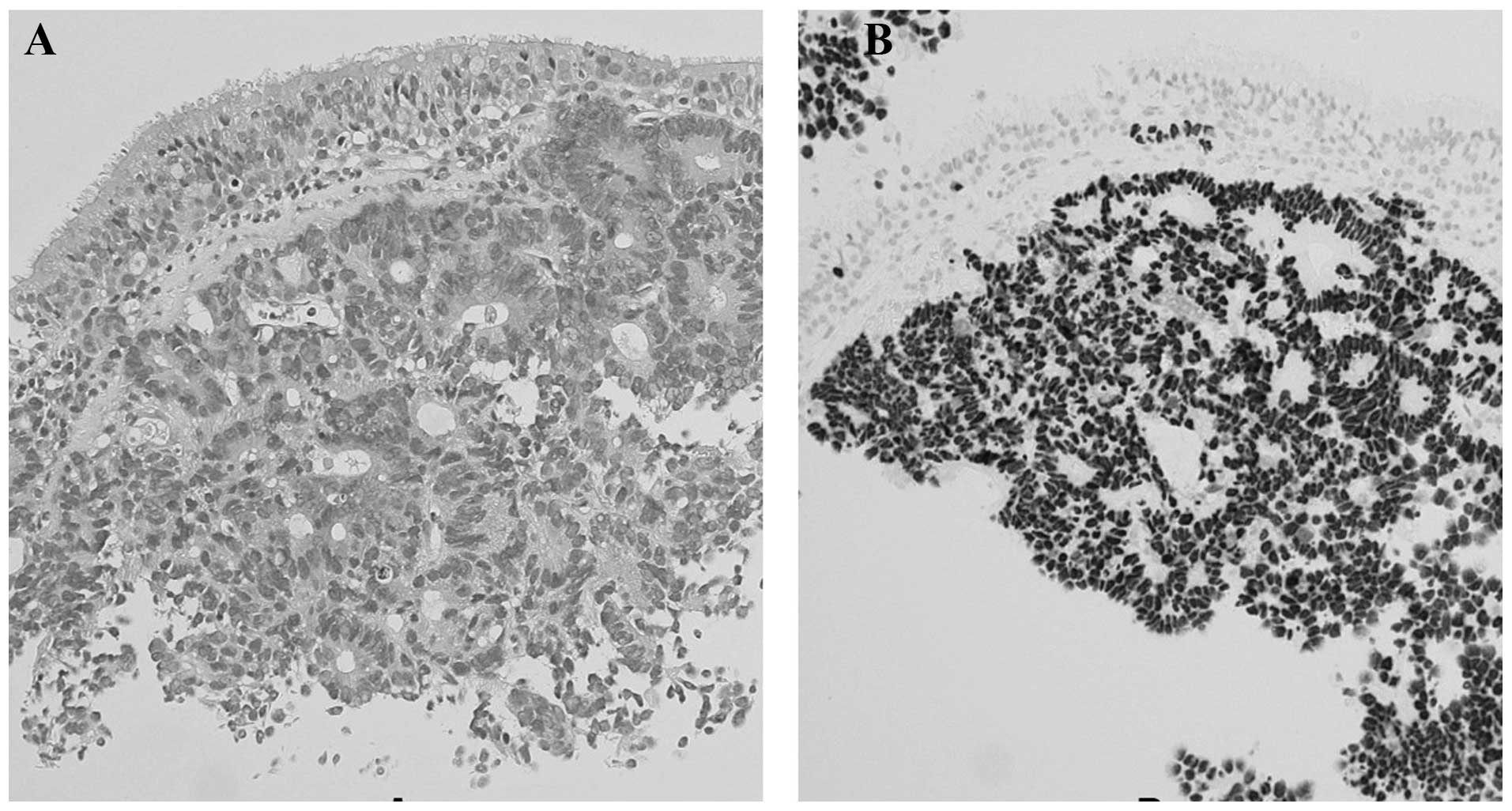

Pathological examination of the tumors obtained from

the left main bronchus revealed well-differentiated adenocarcinoma

with a cribriform pattern, which was consistent with the findings

of a resected adrenocortical carcinoma (Fig. 3A). Positive immunochemical staining

with caudal-type homeobox transcription factor 2 was confirmed

(Fig. 3B). The patient was treated

with two courses of TS-1 (80 mg/day for two weeks), but developed

multiple brain metastases. One month subsequent to the initiation

of the chemotherapy, the patient succumbed to colon cancer. An

autopsy was not permitted.

Discussion

The lung is one of the most common metastatic sites

of extra-thoracic tumors, the majority of which are found in the

pulmonary parenchyma. Although extremely rare, patients with

endobronchial metastasis do occur. The most common symptoms of

endobronchial metastasis are coughing and hemoptysis, followed by

dyspnea and wheezing. If one or more of these symptoms are present

in patients with extra-thoracic tumors, it is possible that such

symptoms may be being caused by endobronchial metastasis. However,

endobronchial metastasis can also be found in asymptomatic

patients. Three of the most common tumors that develop

endobronchial metastases are breast, colon and renal tumors

(1,2,5–7).

The differential diagnosis of an endobronchial mass

lesion includes non-malignant tumors, endobronchial metastasis of

carcinoma from extrapulmonary organs and primary lung carcinoma

(3–8). Endobronchial lesions can be examined

by fiberoptic bronchoscopy, since the majority of lesions are

within the view and grasp of the bronchoscopic field. Non-malignant

endobronchial tumors usually possess a smooth surface with a

uniform color (9). Endoscopic

manifestations of an endobronchial metastatic lesion are

considerably variable, but polypoid tumors with necrotic material

and nodular tumors are commonly observed. Among the primary lung

cancer types, squamous cell carcinoma is the most prevalent

histological type that is centrally located and exhibits

endobronchial extension (4).

Polypoid lesions with a necrotic material-covered rough surface are

the most frequently occurring tumors in squamous cell carcinoma

(10,11). Certain patients with squamous cell

or mucoepidermoid lung cancer exhibit superficial or nodular

endobronchial tumors (12,13). In addition, although extremely rare,

multifocal primary squamous cell carcinomas can develop in each of

the bronchi, as observed in the present case (12). The mass-like endobronchial plug

(14), which possibly represents an

endobronchial infectious process, including mucus plugs distal to a

centrally obstructing lesion due to fungus or tuberculosis, also

simulates an endobronchial mass on endobronchial examination. In

general, it is accepted that without pathological confirmation, the

bronchoscopic findings of endobronchial metastasis are not clearly

distinct from those of primary lung carcinoma and non-malignant

tumors (15,16). In certain cases, the benefits of

bronchoscopic examination may be diminished due to the presence of

necrotic material interfering with the opportunity to obtain a

proper diagnostic specimen (17–19).

Therefore, in order to form a proper diagnosis, it is essential to

combine the pathological diagnosis with immunohistochemical

examination using appropriate specimens obtained by bronchoscopic

biopsy.

In primary lung cancer, the endobronchial types have

been defined as superficial, nodular and submucosal (20). By contrast, however, there has been

no such classification for endobronchial metastatic lesions. If the

primary lung cancer classification was to be applied to the present

case, the tumor may be classed as of superficial or submucosal

type. The endobronchial lesions in the present patient may be the

early stage of endobronchial metastasis. These lesions may become

enlarged to form nodular lesions, which are usually classified as

nodular-type lung cancer.

Endobronchial lesions may form either by invasion

from the surrounding tissues, including the lung parenchyma or

hilar and/or mediastinal lymph nodes, or by direct seeding within

the bronchial wall (1,2). The endobronchial metastasis type in

the present patient may be due to direct metastasis to the bronchus

or endobronchial invasion of mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy.

Although endobronchial metastasis is an extremely rare tumor

presentation, the possibility that colon cancer can develop

superficial endobronchial tumors in each of the bronchi should be

considered.

References

|

1

|

Akoglu S, Uçan ES, Celik G, et al:

Endobronchial metastases from extrathoracic malignancies. Clin Exp

Metastasis. 22:587–591. 2005.

|

|

2

|

Kiryu T, Hoshi H, Matsui E, et al:

Endotracheal/endobronchial metastases: clinicopathologic study with

special reference to developmental modes. Chest. 119:768–775.

2001.

|

|

3

|

Unger M: Endobronchial therapy of

neoplasms. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 13:129–147. 2003.

|

|

4

|

Koss MN, Hochholzer L and Frommelt RA:

Carcinosarcomas of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of 66

patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 23:1514–1526. 1999.

|

|

5

|

Katsimbri PP, Bamias AT, Froudarakis ME,

et al: Endobronchial metastases secondary to solid tumors: report

cases and review of the literature. Lung Cancer. 28:163–170.

2000.

|

|

6

|

Braman SS and Whitcomb ME: Endobronchial

metastasis. Arch Intern Med. 135:543–547. 1975.

|

|

7

|

Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, et al: Atypical

pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings.

Radiographics. 21:403–417. 2001.

|

|

8

|

Shah H, Garbe L, Nussbaum E, et al: Benign

tumors of the tracheobronchial tree. Endoscopic characteristics and

role of laser resection. Chest. 107:1744–1751. 1995.

|

|

9

|

Oshikawa K, Ohno S, Ishii Y and Kitamura

S: Evaluation of bronchoscopic findings in patients with metastatic

pulmonary tumor. Intern Med. 37:349–353. 1998.

|

|

10

|

Lam B, Wong MP, Fung SL, et al: The

clinical value of autofluorescence bronchoscopy for the diagnosis

of lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 28:915–919. 2006.

|

|

11

|

Shulman L and Ost D: Advances in

bronchoscopic diagnosis of lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med.

13:271–277. 2007.

|

|

12

|

Yasufuku K: Early diagnosis of lung

cancer. Clin Chest Med. 31:39–47. 2010.

|

|

13

|

Wildbrett P, Horras N, Lode H, Warzok R,

Heidecke CD and Barthlen W: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the lung in

a 6-year-old boy. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 9:159–162. 2012.

|

|

14

|

Itoi S, Ohara G, Kagohashi K, Kawaguchi M,

Kurishima K and Satoh H: Tracheobronchial mucoid pseudotumor. Cent

Eur J Med. 7:385–387. 2012.

|

|

15

|

Murakami S, Watanabe Y, Saitoh H, et al:

Treatment of multiple primary squamous cell carcinomas of the lung.

Ann Thorac Surg. 60:964–969. 1995.

|

|

16

|

Saida Y, Kujiraoka Y, Akaogi E, et al:

Early squamous cell carcinoma of the lung: CT and pathologic

correlation. Radiology. 201:61–65. 1996.

|

|

17

|

Lau KY: Endobronchial actinomycosis

mimicking pulmonary neoplasm. Thorax. 47:664–665. 1992.

|

|

18

|

Kim JS, Rhee Y, Kang SM, et al: A case of

endobronchial aspergilloma. Yonsei Med J. 41:422–425. 2000.

|

|

19

|

Van den Brande P, Lambrechts M, Tack J and

Demedts M: Endobronchial tuberculosis mimicking lung cancer in

elderly patients. Respir Med. 85:107–109. 1991.

|

|

20

|

The Japan Lung Cancer Society. General

Rule for Clinical and Pathological Record of Lung Cancer. 7th

edition. Kanehara Shuppan; Tokyo, Japan: 2010

|