Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disease in

humans. A review on population studies reported that OSA may be

found in both men and women with the highest prevalence rate of 37

and 50%, respectively (1). It is

also known that OSA is related to five major cardiovascular

diseases, including hypertension, heart failure, atrial

fibrillation, coronary artery disease and stroke (2-5).

A sleep cohort study, conducted in the USA, found that untreated

patients with severe sleep disordered breathing presented with

coronary artery disease or heart failure 2.6 times more often

compared with those without OSA (95% CI, 1.1-6.1) (6). The first line treatment for OSA is the

usage of a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine, as

it is cost effective with 15,915 USD per quality-adjusted life year

gained (7,8).

Other than the improvement in the quality of life,

CPAP therapy, for at least 4 h per night in patients with OSA,

reduces the risks of acute coronary artery disease or heart attack

by 83% (95% CI, 0.03-0.81) (9).

Despite the benefits of CPAP therapy, not all patients with OSA

purchase the machine for personal use. The CPAP purchasing rate in

patients with OSA varies between 33 and 77% (10,11).

There are several predictors for CPAP purchasing in patients with

OSA, such as income, socioeconomic status and health insurance

(9-11).

A study from Mexico (12) found

that patients with OSA and public health insurance had a 1.71 times

higher chance of purchasing a CPAP machine compared with those

without insurance (95% CI, 1.04-2.83), whereas other studies

reported that predictors for CPAP purchasing were age and OSA

severity (11,13). An increase in age, by one year,

showed a 7% higher chance of CPAP purchasing (13). Additionally, a previous study found

that marketing strategies may be valid predictors for CPAP

purchasing (10). Those who

purchased a CPAP machine preferred to have the option of several

CPAP models than those who did not purchase a CPAP machine (3.79

vs. 3.36/5 by Likert scale; P=0.092). As there are several and

inconsistent predictors of CPAP purchasing, the present study aimed

to summarize and identify predictors of CPAP purchasing using

meta-analysis. Furthermore, there is a lack of meta-analyses and

systematic reviews of predictors of CPAP purchasing in patients

with OSA in the literature.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present meta-analysis included factors

associated with the purchase of a CPAP machine in patients with

OSA. The types of studies conducted in adult patients with OSA

included: Randomized controlled trials, observational studies or

descriptive studies comparing factors between those who purchased

CPAP and those who did not. The diagnosis of OSA was made using

polysomnography upon evidence of an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) or a

respiratory disturbance index (RDI) of five or more events/h. After

being diagnosed with OSA, CPAP trial or CPAP titration was

initiated either in a sleep laboratory or at home. CPAP titration

is performed with the aim of identifying the appropriate CPAP

pressure for each patient. A decision to purchase a CPAP machine is

made after CPAP titration. Studies conducted in adult patients with

OSA that had received CPAP titration either in a sleep laboratory

or at home were included.

Literature search and data

extraction

In the present meta-analysis, five databases were

searched: PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), Central database

(www.cochranelibrary.com/central), Scopus (www.scopus.com), CINAHL Plus (https://web.s.ebscohost.com/) and Web of Science

(www.webofknowledge.com). The search

terms used were ‘obstructive sleep apnea’, ‘sleep apnea syndrome’,

‘predict*’, ‘independent’, ‘factor*’,

‘variable*’, ‘purchase*’, ‘buy’, ‘bought’,

‘pay’, ‘paid’, ‘expend*’ and ‘spend*’, where

‘*’ was used to search for all terms which began with

the preceding letters. The full list of search terms is shown in

Table SI, Table SII, Table SIII, Table SIV and Table V. The final search was performed on

February 8, 2021. After the duplicates were removed, initial

screening was performed for non-relevant articles. Studies were

considered relevant if they had been conducted to evaluate

different factors between patients who purchased a CPAP machine and

those who did not. Data extraction and full text reports were

reviewed by two independent authors (BS and KS). Of these, the

articles that met the study criteria were included in the final

analysis (14).

Studied variables and outcomes

The studied variables included both marketing and

clinical factors. The definitions of the studied variables were as

follows: Average to high income determined in each study, which may

vary among countries; health insurance covering CPAP machine costs,

which indicated cost reimbursement by the insurer; and Epworth

Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, which is a subjective sleepiness

evaluation method with a value range of 0-24(15). The primary outcome assessed were

factors that varied between patients who purchased a CPAP machine

and those who did not. At least two studies were required to

calculate the differences of the studied variables between the two

groups. The mean differences were calculated between the two groups

with a 95% CI for numerical factors and the odds ratio with 95% CI

for categorical outcomes. Heterogeneity was computed and reported

as I squared (I2). A forest plot of each comparison was

created based on I2. If I2 was ≤75%, fixed

effect was used. For factors displaying an I2 value of

>75%, the random effect was used.

Evaluation of the study quality

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, adapted for

cross-sectional studies, was used to evaluate the study quality of

observational studies (16). The

scale comprised three categories: Selection process, comparability

and outcome measurement, with a score of 5, 2 and 3 points,

respectively. The total score was 10 points and classified as very

good (9-10 points), good (7-8 points), satisfactory (5-6 points)

and non-satisfactory (0-4 points). Study quality was evaluated

independently by two authors (BS and CN). Disagreements between

these two authors were discussed and a final decision was made by a

third reviewer (KS). All analyses were performed using Review

Manager 5.4 (Copenhagen, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane

Collaboration, Denmark).

Results

Study inclusion

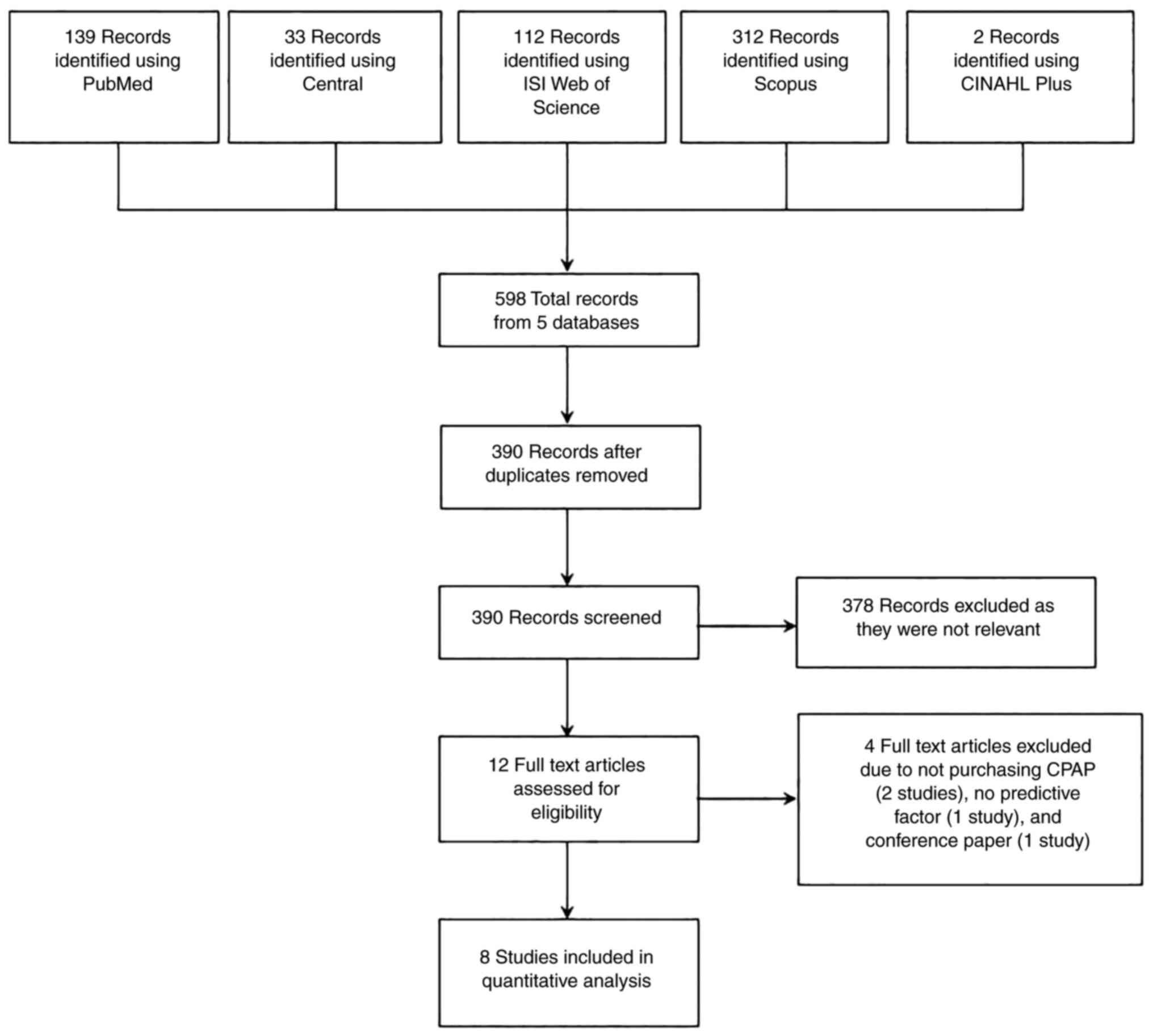

There were 598 articles from five databases, which

met the search criteria (Fig. 1).

After duplicate article removal, 390 articles were included in the

screening process. There were 12 articles found to be eligible for

full text evaluation. A total of four studies were excluded: Two

studies were excluded as CPAP compliance was evaluated, not

purchasing of CPAP machines; one study was excluded as the rate of

CPAP purchasing did not include variable evaluation; and one study

was excluded as only the abstract was available, which was from a

conference. In total, there were eight eligible studies involving

1,605 patients from four countries (6-10,17):

Five studies from Israel (11,16-20),

one from Mexico (12), one from

Poland (17) and one from Thailand

(10). The most recent study was

published in 2018 by Sawunyavisuth (10) from Thailand (Table I).

| Table IEligible studies for meta-analysis of

patients who purchased a CPAP machine and those who did not. |

Table I

Eligible studies for meta-analysis of

patients who purchased a CPAP machine and those who did not.

| First author/s,

year | Country | Study design | Diagnosis of

OSA | Duration of CPAP

trial | Data | Total cases, n | Purchased, n

(%) | Did not purchase,n

(%) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Torre Bouscoulet

et al, 2007 | Mexico | NA | AHI >5/h or

desaturation index >15/h | NA | Telephone

contact | 304 | 169 (55.6) | 135 (44.4) | (12) |

| Brin et al,

2005a | Israel |

Cross-sectional | RDI >20/h or RDI

<20/h with EDS and ESS >9 | 2 weeks | Self-administered

questionnaire | 400 | 128(32) | 272(68) | (18) |

| | | | | | | 183b |

128(70)b | 55(30)b | |

| Byśkiniewicz,

2006 | Poland | NA | NA | NA | NA | 184 | 116(63) | 68(37) | (17) |

| Sawunyavisuth,

2018 | Thailand |

Cross-sectional |

Polysomnography | 3 nights | Self-reported

questionnaire | 53 | 41 (77.36) | 12 (22.64) | (10) |

| Shahrabani et

al, 2014a | Israel | NA | NA | Varied | Phone

interview | 194 | 100(52) | 94(48) | (19) |

| Simon-Tuval et

al, 2009a | Israel |

Cross-sectional | NA | 2 weeks | Questionnaire | 162 | 65(40) | 97(60) | (13) |

| Tarasiuk et

al, 2012c,d | Israel | Longitudinal

interventional | AHI >30/h or

>15/h with ESS >10 | 2 weeks | Questionnaire,

telephone survey | 121 (control

group) | 40 (33.1) | 81 (66.9) | (11) |

| | | | (moderate to

severe) | | | 137 (incentive

group) | 65 (47.4) | 72 (52.6) | |

| Tzischinsky et

al, 2011 | Israel | NA | NA | NA | Questionnaire,

telephone interview | 50 | 24(48) | 26(52) | (20) |

Details of the included studies

The most common study design was cross-sectional and

was used in three of the studies (10,13,18).

The diagnosis of OSA was made using polysomnography; however, the

inclusion criteria for OSA were variable, with the highest AHI of

30 events/h (11). The duration of

CPAP titration or trial, prior to CPAP purchase, was a maximum of 2

weeks (11,13,18).

Not all patients with OSA, in three of the studies, underwent CPAP

titration [Brin et al (18),

183/400 patients; Shahrabani et al (19), 150/194 patients; Simon-Tuval et

al (13), 132/162 patients]. In

these three studies, data for analysis were obtained from the total

population in the study. Most studies used self-administered

questionnaires or telephone interviews to record patient

information. The numbers of participating patients varied between

50(20) and 400(18), with an average CPAP purchasing rate

of 49.8%. Only one study evaluated marketing strategies on CPAP

purchasing (10).

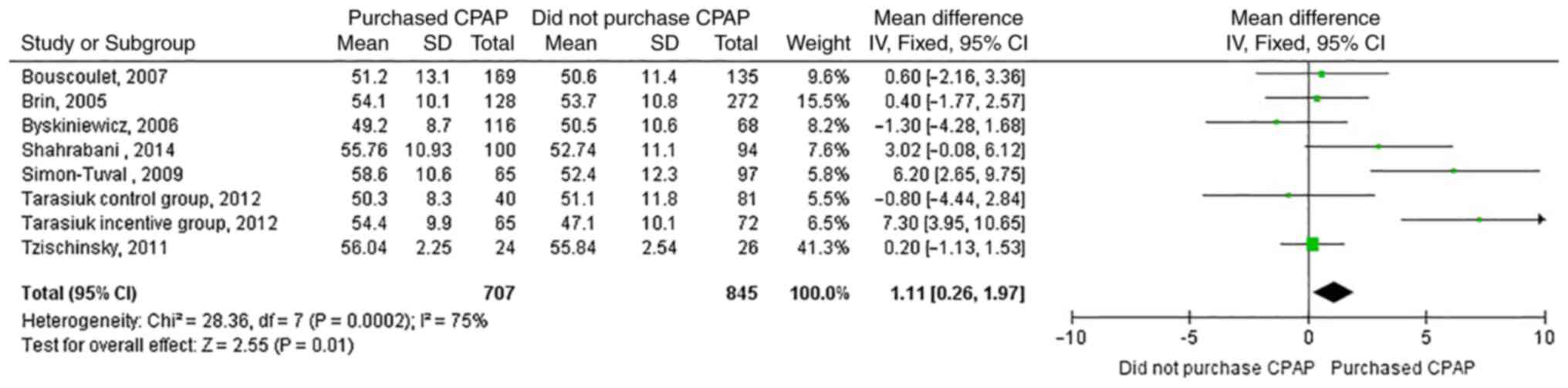

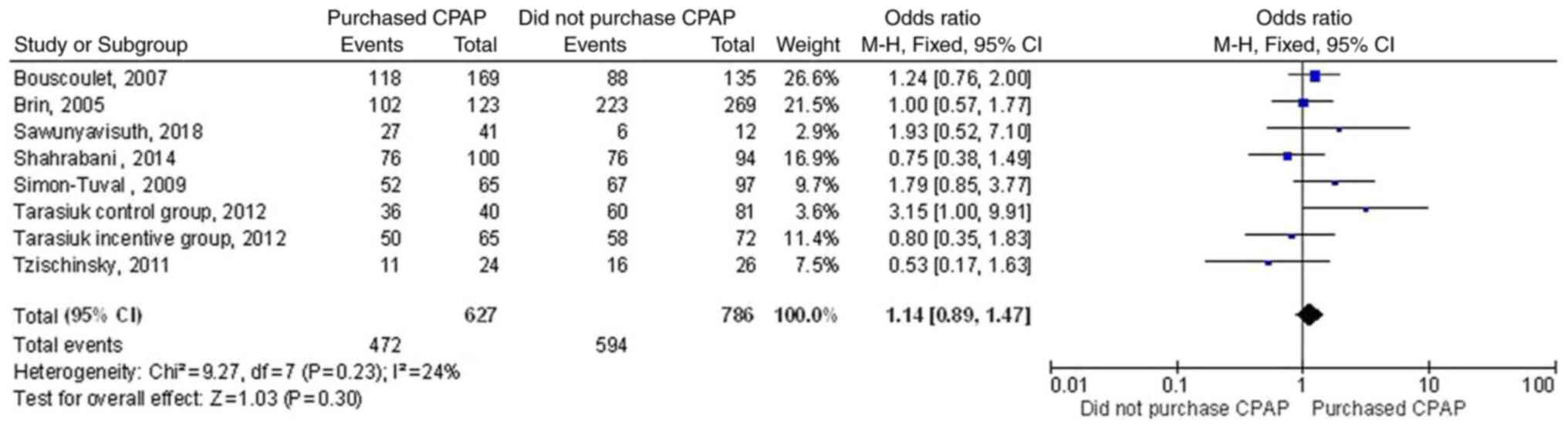

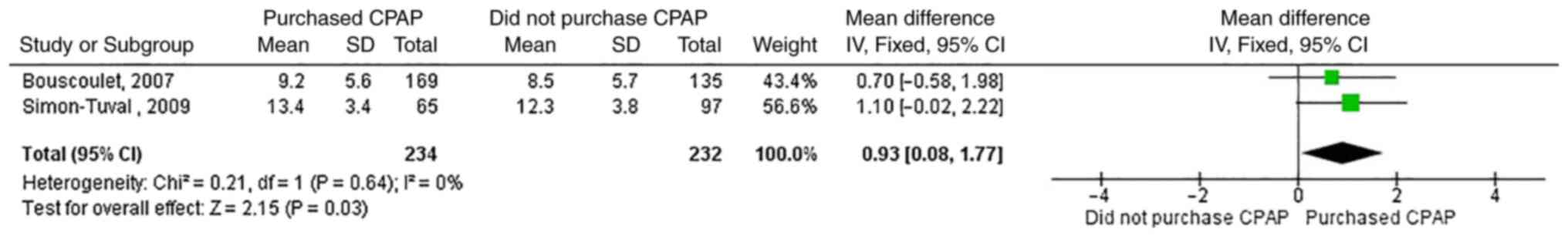

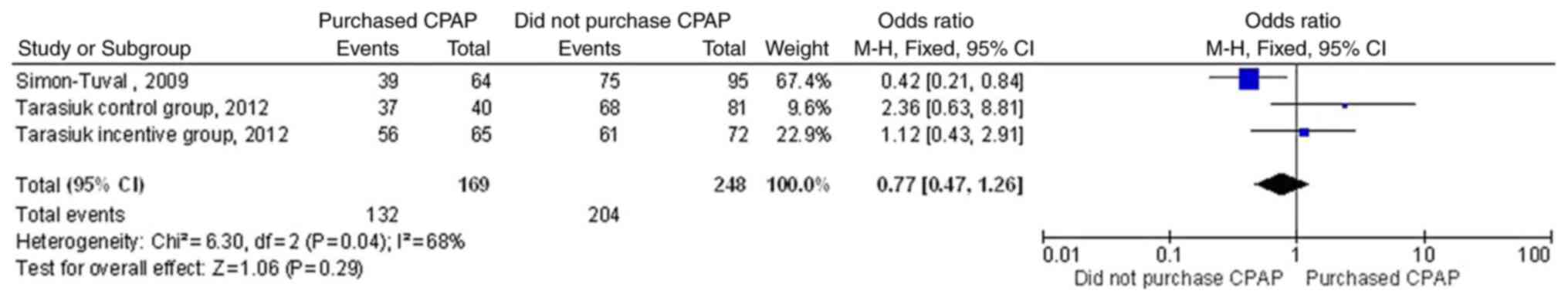

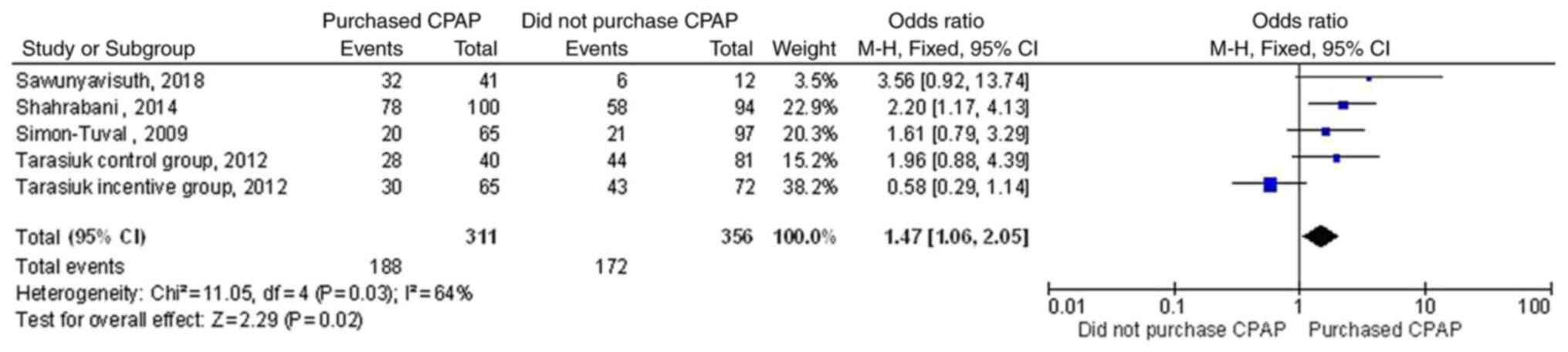

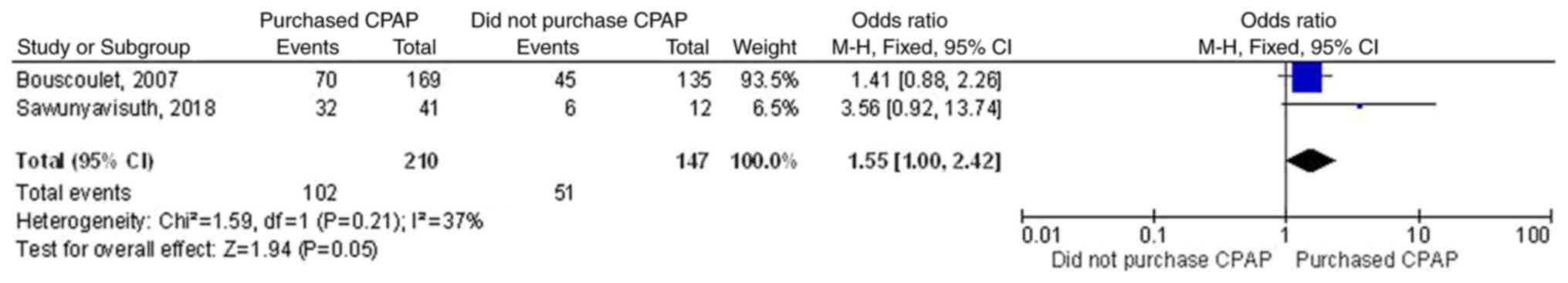

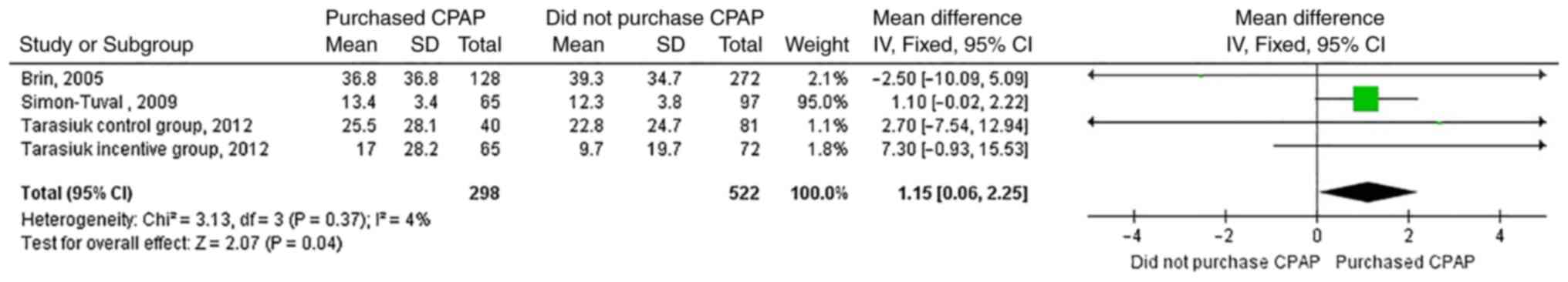

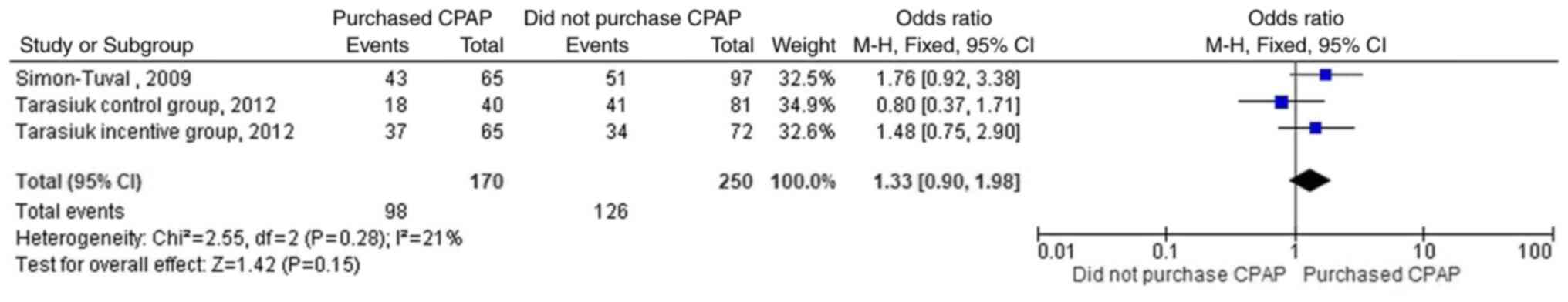

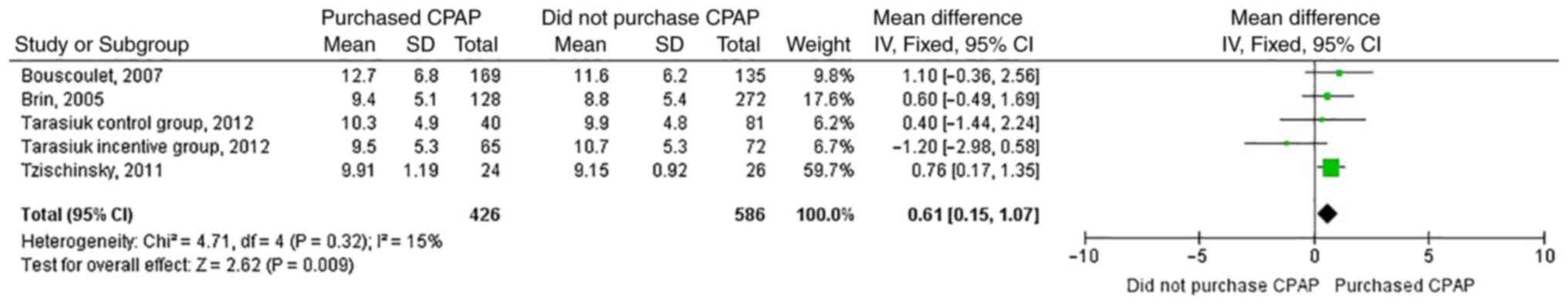

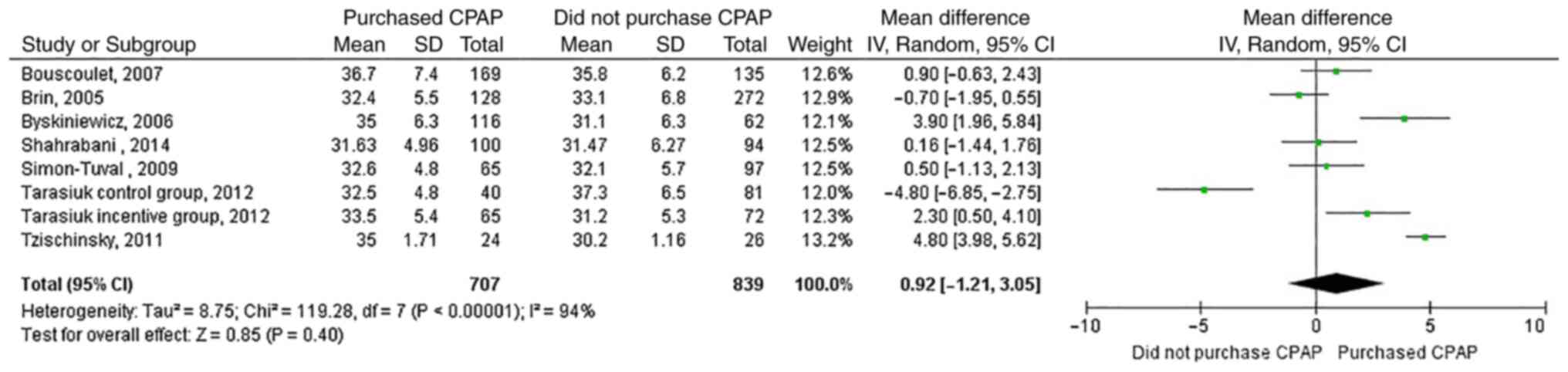

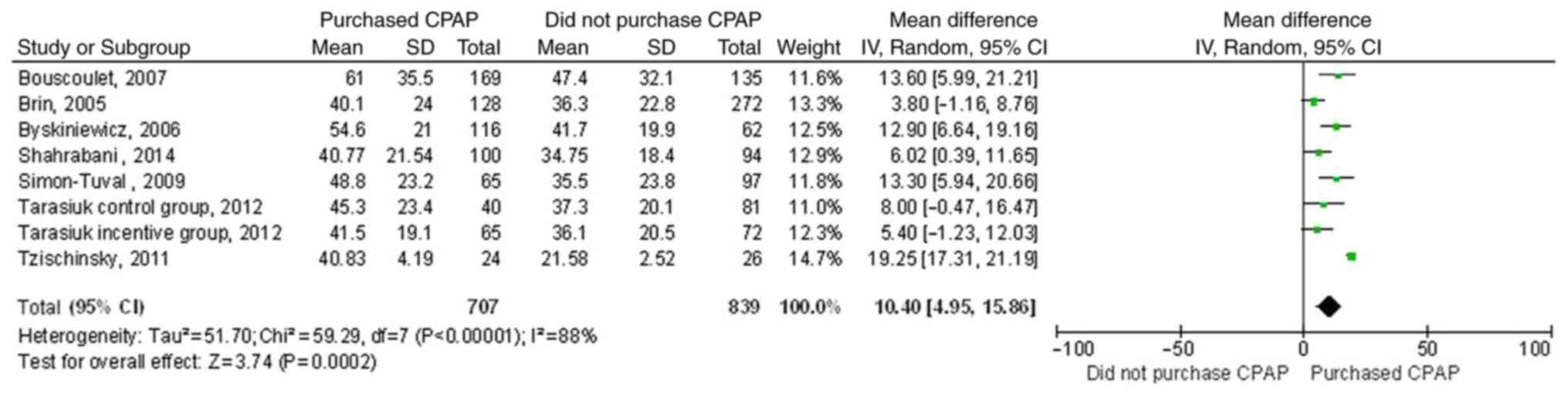

Study outcomes

There were 11 variables available for comparison

between patients who purchased a CPAP machine and those who did not

(Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig.

4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig.

7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig.

10, Fig. 11 and Fig. 12). These factors were age (Fig. 2), sex (Fig. 3), years of education (Fig. 4), living with a partner (Fig. 5), income (Fig. 6), insurance (Fig. 7), smoking (Fig. 8), hypertension/cardiovascular

disease (Fig. 9), ESS (Fig. 10), body mass index (Fig. 11) and AHI/RDI (Fig. 12). A total of six factors were

found to be significantly different between both groups: Age

(Fig. 2), years of education

(Fig. 4), income (Fig. 6), smoking (Fig. 8), ESS (Fig. 10) and AHI/RDI (Fig. 12). AHI/RDI was significantly

different between the two groups with the highest mean difference

of 10.40 events/h (95% CI, 4.95-15.86) as shown in Fig. 12. Patients who purchased a CPAP

machine were older (by 1.11 years), had more years of education

(0.93 years more), were smoking more (by 1.15 pack/year), and had

higher ESS (by 0.61) and AHI/RDI (by 10.40) scores than those who

did not purchase a CPAP machine, as shown in Figs. 2, 4,

8, 10 and 12, respectively. Additionally, those who

purchased a CPAP machine had a 1.47 times higher income than those

who did not (Fig. 6). The quality

of most of the studies was evaluated as satisfactory, except for

the longitudinal study by Tarasiuk et al (11), which was considered as good, with a

score of 7/10 (Table II).

Furthermore, the study by Byśkiniewicz (17) was not scored as it was published in

Polish.

| Table IIStudy quality evaluation using the

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies of the

included studies. |

Table II

Study quality evaluation using the

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies of the

included studies.

| First author/s,

year | Study design | Selection process

(5) | Comparability

(2) | Outcome measures

(3) | Total (10) | Interpretation | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Torre Bouscoulet

et al, 2007 | NA | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Satisfactory | (12) |

| Brin et al,

2005 |

Cross-sectional | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Satisfactory | (18) |

| Byśkiniewicz,

2006 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA due to

non-English article | (17) |

| Sawunyavisuth,

2018 |

Cross-sectional | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Satisfactory | (10) |

| Shahrabani et

al, 2014 | NA | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Satisfactory | (19) |

| Simon-Tuval et

al, 2009 |

Cross-sectional | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Satisfactory | (13) |

| Tarasiuk et

al, 2012 | Longitudinal | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | Good | (11) |

| Tzischinsky et

al, 2011 | NA | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Satisfactory | (20) |

Discussion

The six significant factors that were compared

between patients with OSA who did or did not purchase a CPAP

machine can be categorized into two groups: Customer-related and

clinical factors. The personal customer factors included age, years

of education and income, while the clinical factors were age,

smoking, ESS and AHI/RDI. In addition, age was included in both

groups as it can be classified as both a personal customer factor

and clinical factor.

There are several customer behavior models, such as

the Nicosia model, Howard Sheth model, or Engel, Blackwell and

Minard model (21,22). The significant factors in the

present study are personal customer factors, which is one factor of

several customer behaviors in the black box consumer behavior model

(23). Additionally, a previous

study from China found that these personal factors are related to

higher chances of purchasing healthcare devices; however, the

purchase of a CPAP machine was not included in the study (24). Patients with OSA who purchased a

CPAP machine were 1.11 years older, had 0.93 years longer education

and, on average, a 1.47 times higher income than those who did not

purchase a CPAP machine. The previous Chinese study found that

older age, higher education (Junior college degree) and higher

income had odds ratios of 6.65, 4.02 and 7.88, respectively

(24). Both studies identified

similar trends for these predictors, but different magnitudes as

this study was more specific to the use of CPAP machines by

summation of several studies. Furthermore, differences in defining

what constitutes high income among countries and currency

differences require a cautious interpretation of CPAP purchase. Of

note, the present meta-analysis indicated that patients with OSA

and health insurance coverage had a 1.55 times higher chance of

purchasing a CPAP machine than those without such coverage (95% CI,

1.00-2.42), as shown in Fig. 7. It

should be noted that insurance almost reached statistical

significance in the present study. The aforementioned coverage

reduces the machine's cost, making it more affordable.

The four clinical factors, which were found to

change significantly between the two groups, were related to

severity of OSA. Older age, smoking and daytime sleepiness are

indicators of severe OSA (25-27).

Older age has been reported to be related to increased severity of

OSA, with a correlation coefficient of 0.331 (P<0.01) (25), whereas smoking was associated with

moderate/severe OSA by 4.4 times (95% CI, 1.5-13) (26). A high ESS score of >10 was found

more often in severe OSA, as compared with mild or moderate OSA

(40.2 vs. 26.7 and 29.6%, respectively; P<0.001) (27). As a result, more patients with more

severe OSA tended to purchase a CPAP machine more often than those

with less severe OSA. In the present study, patients with OSA who

purchased a CPAP machine had a higher AHI by 10.40 events/h than

those who did not purchase a CPAP machine (Fig. 12). Of note, this AHI/RDI mean

difference displayed the highest value among the studied variables.

As previously reported, patients with severe OSA had higher chances

of sudden death or developing cardiovascular diseases, including

coronary artery heart disease, heart failure, left ventricular

hypertrophy, hypertension or atrial fibrillation (28-30).

Those patients with OSA with an AHI score of >20 events/h are

likely to have sudden cardiac death (29). Therefore, patients with severe OSA

may have several cardiovascular diseases, as well as being more

symptomatic, leading to higher chances of purchasing a CPAP

machine.

There are some limitations in the present study.

First, most studies conducted in Israel may have different cultures

or purchasing habits from other countries. Second, some patients

did not undergo a CPAP trial prior to CPAP purchase (8-10).

In addition, the duration of a CPAP titration prior to a decision

of purchasing a CPAP machine varied (Table I). Third, some studied variables,

such as body mass index and AHI, bore high heterogeneity. Fourth,

CPAP compliance or other related conditions of OSA such as CPAP

intervention, exercise intervention, cognitive function, or asthma

were not studied (31-38).

Finally, marketing strategies which may be related to CPAP purchase

were investigated in only one study (10). Therefore, further studies regarding

the roles of marketing strategies in CPAP purchase may be

required.

In conclusion, personal customer factors and

clinical factors were related to the decision of patients with OSA

to purchase a CPAP device.

Supplementary Material

Search strategy for PubMed (retrieved

on February 7, 2021).

Search strategy for Central (retrieved

on February 7, 2021).

Search strategy for ISI Web of science

(retrieved on February 7, 2021).

Search strategy for Scopus (retrieved

on February 8, 2021).

Search strategy for CINAHL Plus

(retrieved on February 8, 2021).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Research and

International Affair, Faculty of Medicine (grant no. SY65101), Khon

Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

BS designed the study, extracted the data, evaluated

study quality, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted

data, and wrote the manuscript. CN performed the searches,

evaluated study quality, performed the statistical analysis,

interpreted the data, and reviewed the manuscript. KS evaluated

study quality, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the

data, and reviewed the manuscript. BS and KS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Franklin KA and Lindberg E: Obstructive

sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the

epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 7:1311–1322.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C,

Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, et

al: 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention

in clinical practice: The sixth joint task force of the European

society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease

prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of

10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special

contribution of the European association for cardiovascular

prevention & rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 37:2315–2381.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Khamsai S, Chootrakool A, Limpawattana P,

Chindaprasirt J, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Chotmongkol V, Silaruks S,

Senthong V, Sittichanbuncha Y, Sawunyavisuth B and Sawanyawisuth K:

Hypertensive crisis in patients with obstructive sleep

apnea-induced hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord.

21(310)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Khamsai S, Mahawarakorn P, Limpawattana P,

Chindaprasirt J, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Silaruks S, Senthong V,

Sawunyavisuth B and Sawanyawisuth K: Prevalence and factors

correlated with hypertension secondary from obstructive sleep

apnea. Multidiscip Respir Med. 16(777)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Khamsai S, Kachenchart S, Sawunyavisuth B,

Limpawattana P, Chindaprasirt J, Senthong V, Chotmongkol V,

Pongkulkiat P and Sawanyawisuth K: Prevalence and risk factors of

obstructive sleep apnea in hypertensive emergency. J Emerg Trauma

Shock. 14:104–107. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hla KM, Young T, Hagen EW, Stein JH, Finn

LA, Nieto FJ and Peppard PE: Coronary heart disease incidence in

sleep disordered breathing: The Wisconsin sleep cohort study.

Sleep. 38:677–684. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pietzsch JB, Garner A, Cipriano LE and

Linehan JH: An integrated health-economic analysis of diagnostic

and therapeutic strategies in the treatment of moderate-to-severe

obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 34:695–709. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tietjens JR, Claman D, Kezirian EJ, De

Marco T, Mirzayan A, Sadroonri B, Goldberg AN, Long C, Gerstenfeld

EP and Yeghiazarians Y: Obstructive sleep apnea in cardiovascular

disease: A review of the literature and proposed multidisciplinary

clinical management strategy. J Am Heart Assoc.

8(e010440)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Peker Y, Thunström E, Glantz H and

Eulenburg C: Effect of obstructive sleep apnea and CPAP treatment

on cardiovascular outcomes in acute coronary syndrome in the

RICCADSA trial. J Clin Med. 9(4051)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sawunyavisuth B: What are predictors for a

continuous positive airway pressure machine purchasing in

obstructive sleep apnea patients? Asia Pac J Sci Technol.

23(APST-23-03-10)2018.

|

|

11

|

Tarasiuk A, Reznor G, Greenberg-Dotan S

and Reuveni H: Financial incentive increases CPAP acceptance in

patients from low socioeconomic background. PLoS One.

7(e33178)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Torre Bouscoulet L, López Escárcega E,

Castorena Maldonado A, Vázquez García JC, Meza Vargas MS and

Pérez-Padilla R: Continuous positive airway pressure used by adults

with obstructive sleep apneas after prescription in a public

referral hospital in Mexico City. Arch Bronconeumol. 43:16–21.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Spanish).

|

|

13

|

Simon-Tuval T, Reuveni H, Greenberg-Dotan

S, Oksenberg A, Tal A and Tarasiuk A: Low socioeconomic status is a

risk factor for CPAP acceptance among adult OSAS patients requiring

treatment. Sleep. 32:545–552. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J,

Welch VA, Higgins JP and Thomas J: Updated guidance for trusted

systematic reviews: A new edition of the cochrane handbook for

systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

10(ED000142)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Johns MW: A new method for measuring

daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep.

14:540–545. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sisay M, Mengistu G and Edessa D:

Epidemiology of self-medication in Ethiopia: A systematic review

and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol.

19(56)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Byśkiniewicz K: Factors determining the

decision to initiate nCPAP therapy in patients with obstructive

sleep apnea (OSA). Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 74:45–50. 2006.PubMed/NCBI(In Polish).

|

|

18

|

Brin YS, Reuveni H, Greenberg S, Tal A and

Tarasiuk A: Determinants affecting initiation of continuous

positive airway pressure treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 7:13–18.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shahrabani S, Tzischinsky O, Givati G and

Dagan Y: Factors affecting the intention and decision to be treated

for obstructive sleep apnea disorder. Sleep Breath. 18:857–868.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Tzischinsky O, Shahrabani S and Peled R:

Factors affecting the decision to be treated with continuous

positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Isr

Med Assoc J. 13:413–419. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Goodhope O and Pcon A: Major classic

consumer buying behaviour models: Implications for marketing

decision-making. J Econ Sustain Dev. 4:164–172. 2013.

|

|

22

|

Waykole NH and Bhangale AI: A study of

influence of digital marketing on buying behaviour of mobile phone

consumers. J Inf Comput Sci. 10:411–429. 2020.

|

|

23

|

Schlesinger M, Kanouse DE, Martino SC,

Shaller D and Rybowski L: Complexity, public reporting, and choice

of doctors: A look inside the blackest box of consumer behavior.

Med Care Res Rev. 71 (Suppl 5):38S–64S. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang D, Liu S, Wu J and Lin Q: Purchase

and use of home healthcare devices for the elderly: A pilot study

in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 20(615)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hongyo K, Ito N, Yamamoto K, Yasunobe Y,

Takeda M, Oguro R, Takami Y, Takeya Y, Sugimoto K and Rakugi H:

Factors associated with the severity of obstructive sleep apnea in

older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 17:614–621. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Krishnan V, Dixon-Williams S and Thornton

JD: Where there is smoke…there is sleep apnea: Exploring the

relationship between smoking and sleep apnea. Chest. 146:1673–1680.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kapur VK, Baldwin CM, Resnick HE, Gottlieb

DJ and Nieto FJ: Sleepiness in patients with moderate to severe

sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 28:472–477. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Soontornrungsun B, Khamsai S,

Sawunyavisuth B, Limpawattana P, Chindaprasirt J, Senthong V,

Chotmongkol V and Sawanyawisuth K: Obstructive sleep apnea in

patients with diabetes less than 40 years of age. Diabetes Metab

Syndr. 14:1859–1863. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gami AS, Olson EJ, Shen WK, Wright RS,

Ballman KV, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Howard DE and Somers VK:

Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of sudden cardiac death: A

longitudinal study of 10,701 adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 62:610–616.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sanlung T, Sawanyawisuth K, Silaruks S,

Khamsai S, Limpawattana P, Chindaprasirt J, Senthong V, Kongbunkiat

K, Timinkul A, Phitsanuwong C, Sawunyavisuth B and Chattakul P:

Clinical characteristics and complications of obstructive sleep

apnea in srinagarind hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 103(36)2020.

|

|

31

|

Sawunyavisuth B: What personal experiences

of CPAP use affect CPAP adherence and duration of CPAP use in OSA

patients? J Med Assoc Thai. 101:S245–S249. 2018.

|

|

32

|

Kaewkes C, Sawanyawisuth K and

Sawunyavisuth B: Are symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea related

to good continuous positive airway pressure compliance? ERJ Open

Res. 6:00169–2019. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Jeerasuwannakul B, Sawunyavisuth B,

Khamsai S and Sawanyawisuth K: Prevalence and risk factors of

proteinuria in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Asia Pac J

Sci Technol. 26(APST-26-04-02)2021.

|

|

34

|

Leethong-in M, Piyawattanapong S,

Sommongkol S, Thiengtham S, Subindee S, Komniyom N, Chotchaisthit P

and Chuen-arom C: The impact of a brain exercise program on

cognitive functions among rural thai older adults: A

quasi-experimental study. Asia Pac J Sci Technol.

26(APST-26-02-08)2021.

|

|

35

|

Sangjumrus N, Chaiear N, Saikaew K,

So-ngern A and Burge PS: Developing a web application to provide

information on common work-related asthma causative agents. Asia

Pac J Sci Technol. 26(APST-26-04-13)2021.

|

|

36

|

Sawunyavisuth B, Ngamjarus C and

Sawanyawisuth K: Any effective intervention to improve CPAP

adherence in children with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic

review. Glob Pediatr Health. 8(2333794X211019884)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Hlaing SS, Puntumetakul R, Wanpen S and

Saiklang P: Updates on core stabilization exercise and

strengthening exercise: A review article. Asia Pac J Sci Technol.

26(APST-26-04-12)2021.

|

|

38

|

Manasirisuk P, Chainirun N, Tiamkao S,

Lertsinudom S, Phunikhom K, Sawunyavisuth B and Sawanyawisuth K:

Efficacy of generic atorvastatin in a real-world setting. Clin

Pharmacol. 13:45–51. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|