Introduction

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia (NOMI) refers to

irreversible intestinal ischemia and necrosis in the absence of

organic obstruction of the mesenteric blood vessels. In cases of

delayed diagnosis, the prognosis is poor and the mortality rate is

58-70%, being the highest among those with acute mesenteric

ischaemia (AMI) (1). The risk

factors for this condition include heart disease, sepsis and the

use of catecholamines and digitalis (2). The onset mechanism of NOMI involves a

reduction in intestinal blood flow due to factors such as decreased

cardiac output, reduced circulating blood volume, mesenteric

contraction, mesenteric vasospasm caused by sepsis or the use of

vasoconstrictive therapeutic agents. This pathological condition

leads to diminished intestinal blood flow, ultimately resulting in

intestinal ischaemia (3,4). In the early stages of onset, 20-30% of

the patients do not complain of abdominal pain. When abdominal pain

does occur, its location and severity can vary widely. However, as

ischaemia progresses, patients typically develop persistent

abdominal pain, melena and flatulence. With further disease

progression, symptoms of peritoneal irritation, such as muscular

guarding and Blumberg's sign, become evident (2,5).

Treatment with vasodilators is considered useful if there is no

intestinal necrosis; however, surgery is required if the intestinal

tract has reached an irreversible ischaemic state (2,5,6).

Therefore, early diagnosis of intestinal necrosis, which indicates

the need for surgery, is crucial. NOMI can manifest as a shock and

can be fatal, requiring immediate surgical treatment (2). The current study reported a case in

which early diagnosis of NOMI allowed for emergency surgery,

ultimately saving the patient's life.

Case report

The patient first presented at Toyama University

Hospital (Toyama, Japan) in January 2022 with the chief complaint

of a painful tumour in the right cheek without an ulcer. The tumour

was elastic, firm and immobile, measuring 65x50 mm. Right maxillary

carcinoma (cT4bN1M0) was confirmed according to imaging and

histopathological examinations. The patient's medical history

included cerebral haemorrhage (left paresis), early gastric cancer,

colon polyps, hypertension and dementia. Since the tumour was

deemed unresectable, paclitaxel, carboplatin and cetuximab (PCE)

was administered as induction drug therapy. Although drug therapy

was successful and CT revealed the lesion was observed to shrink

after the first course of PCE therapy, the patient visited the

emergency department of our hospital with chief complaints of

melena and abdominal pain 4 days after day 1 of the second course

of PCE therapy. Upon transportation to our hospital, the patient's

Glasgow Coma Scale level of consciousness was E4V4M6 (Score: 14,

mild) (7), oxygen saturation was

90% (normal range, 96-99% under room air), blood pressure was 92/52

mmHg (normal value, 140/90 mmHg) and the heart rate was 111 bpm

(normal range, 60-100 bpm); furthermore, the patient experienced a

peripheral cold sensation. In addition, the abdomen was flat,

elastic and soft with no tenderness, and blood gas analysis

revealed pH of 7.385 (normal range, 7.35-7.45) and lactic acid

level of 4.8 mmol/l (normal range, 0.5-1.6 mmol/l). Based on these

findings, the patient was diagnosed with circulatory failure due to

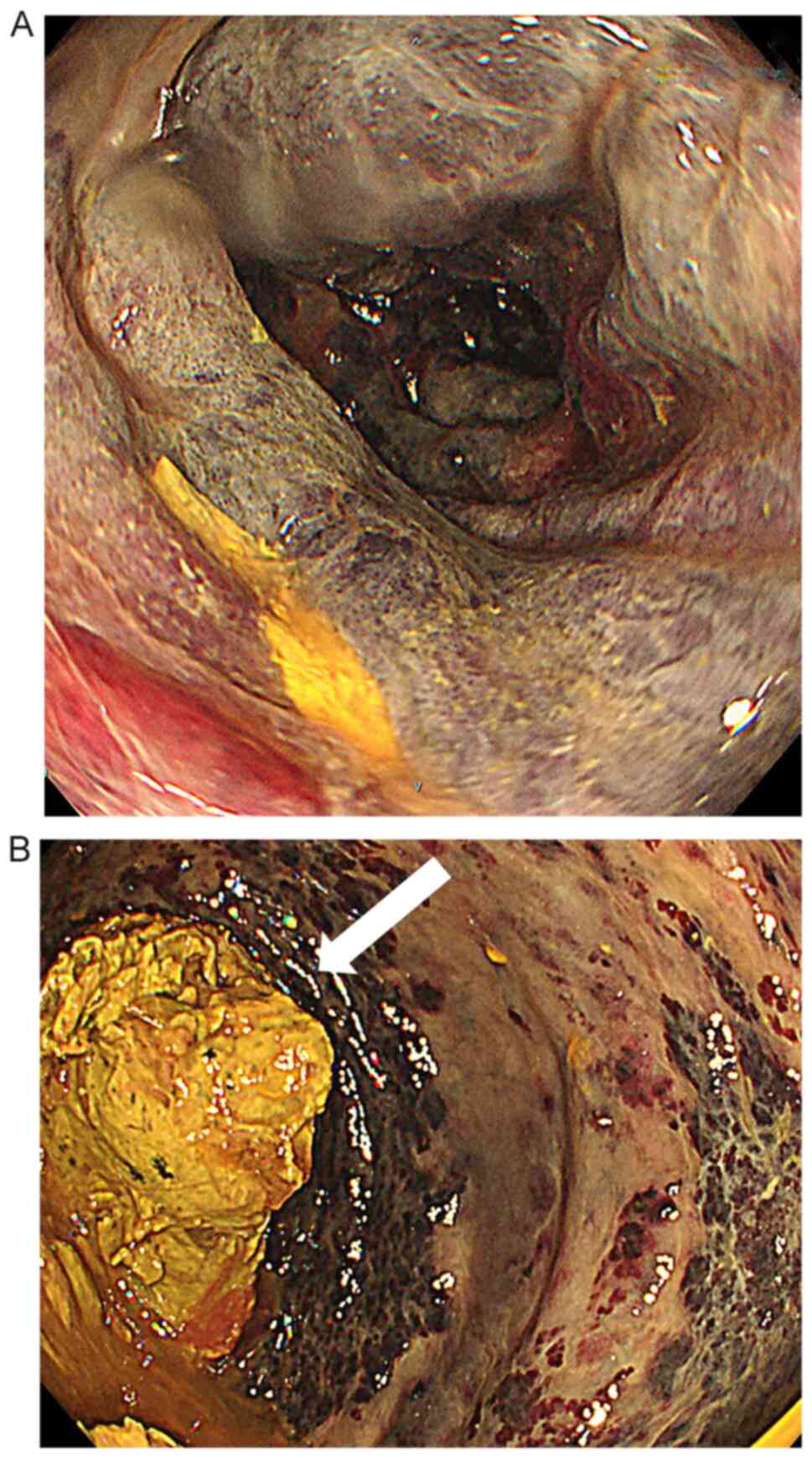

bleeding. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, performed to

investigate the bleeding points, revealed oedema and dark purple

discoloration of the intestinal mucosa, as well as a large amount

of faeces in the rectum (Fig. 1).

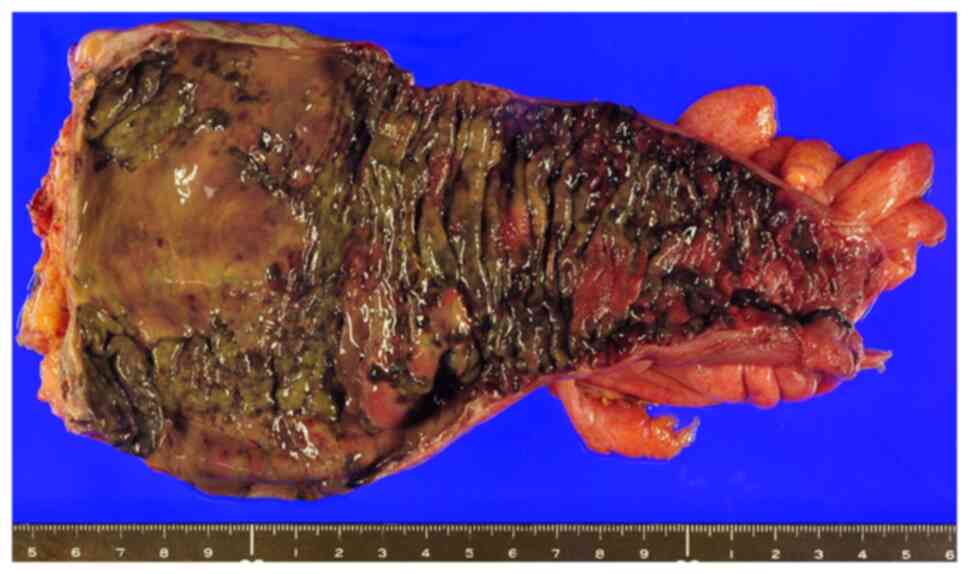

Acute intestinal ischaemia was diagnosed and contrast-enhanced CT

was performed to check for arterial occlusion due to the thrombus.

Although the images showed ischaemia from the transverse to

descending colon (Fig. 2), no

thrombus was found in the superior mesenteric artery. At that time,

the abdomen was slightly hard and tender. Based on these findings,

the patient was diagnosed with NOMI. Emergency surgery, including

colectomy (from the sigmoid colon to the sigmoid rectum) and

colostomy augmentation, was performed on the same day. The resected

specimen showed full-thickness necrosis of the sigmoid rectum

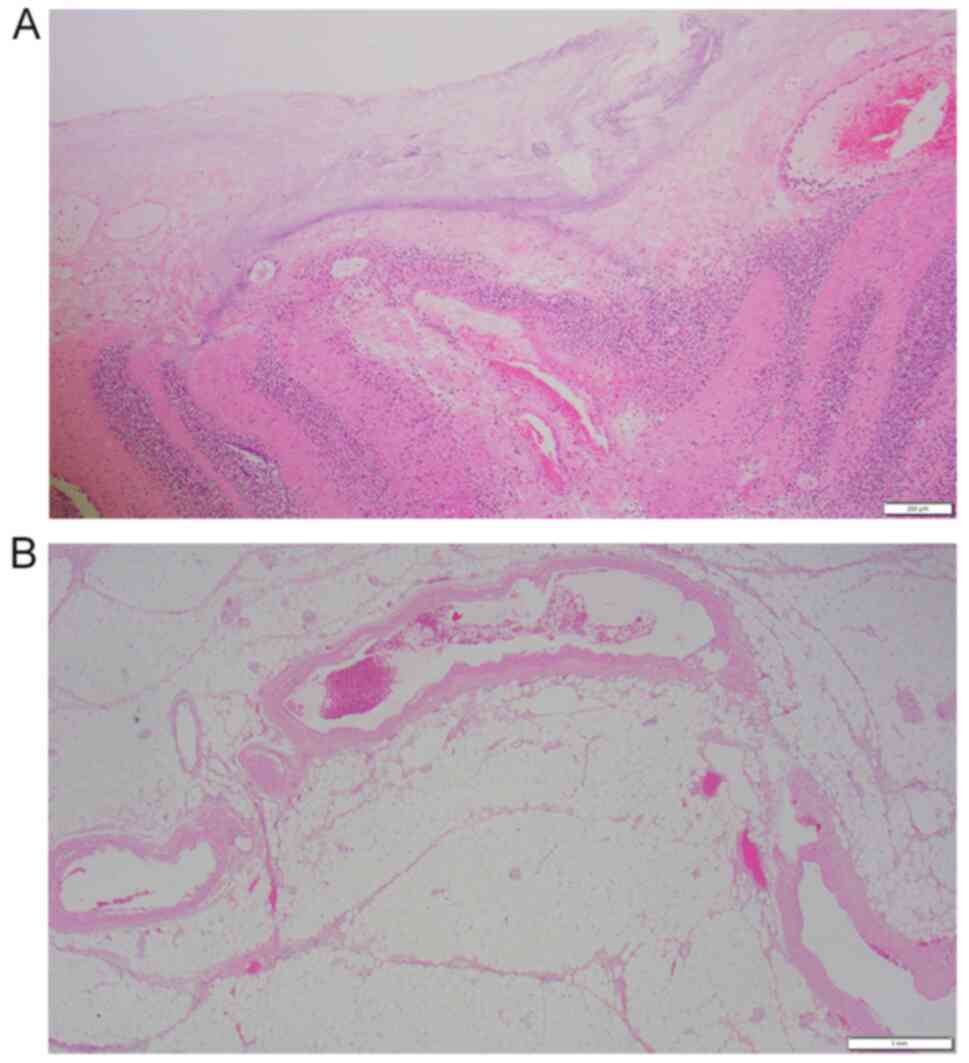

(Fig. 3). Histopathological

examination performed according to standard procedures showed

massive necrosis of the colon and proliferation of neutrophils. No

thrombi were observed in the blood vessels directly beneath the

necrotic mucosa, and the lumen remained patent (Fig. 4). Thereafter, the patient's general

condition improved and no further increase of the lesion in the

right maxillary region was observed. However, owing to a decline in

cognitive function and the presence of aspiration pneumonia, the

patient's performance status (8)

decreased from 2 to 3 and he was transferred to a recuperation

facility for palliative care. The patient's subsequent progress is

unknown.

Discussion

NOMI was first reported in 1958 by Ende (9) in a patient with intestinal necrosis

and heart failure. NOMI is known to cause ischaemia or necrosis of

the intestinal tract, despite the absence of organic obstruction of

the main mesenteric blood vessels. Heer et al (10) defined NOMI as follows: i) No

obstruction in the mesenteric arteries and veins in areas of

intestinal necrosis; ii) discontinuous necrosis and ischaemic

changes in the intestinal tract; and iii) histopathological

findings showing the presence of bleeding and necrosis. However, it

is defined by the lack of fibrin thrombus in the venules (10). The onset mechanism of NOMI involves

a reduction in intestinal blood flow due to factors such as

decreased cardiac output, reduced circulating blood volume,

mesenteric contraction and mesenteric vasospasm caused by sepsis or

the use of vasoconstrictive therapeutic agents. This pathological

condition leads to diminished intestinal blood flow, ultimately

resulting in intestinal ischaemia (3,4).

Furthermore, rapid acceleration of intestinal peristalsis and an

increase in intestinal pressure caused by faecal impaction or enema

has been reported to cause intestinal ischaemia (11). The risk factors for NOMI include

cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, sepsis, arrhythmia

and the use of catecholamines or digitalis (2). A search in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and J-stage

(https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp) for the

search terms (NOMI and chemotherapy) retrieved reports of only 15

cases of NOMI due to chemotherapy (Table I) (5,12-21).

The reason why most of the reported cases are Japanese is unclear

and further investigation is needed. Docetaxel was used in six

cases, paclitaxel in three cases and taxane-based anticancer drugs

were used in nine cases. The onset of NOMI after chemotherapy has

been linked to several factors: Mucosal damage due to the

inhibition of epithelial cell division and proliferation, a

pharmacological effect of taxane-based anticancer drugs (22); and vascular system damage resulting

from the inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation

and migration and neointimal accumulation (23). The intestinal mucosa repeatedly

regenerates every 3rd to 4th day and intestinal mucosal damage

appears after the 3rd to 4th day of administration due to the

suppression of intestinal epithelial cell division and

proliferation by taxane-based anticancer drugs. The increased

intestinal pressure caused by chemotherapy-induced constipation

contributes to the onset of NOMI (5). Taxane-based anticancer drugs have been

approved for use against a wide range of malignant tumours,

including ovarian, breast and head and neck cancers. Intestinal

disorders such as gastrointestinal necrosis, perforation, bleeding,

ulcers and severe enteritis have been reported, although at a low

incidence (<0.1%) (24).

However, in the case of ischaemic colitis due to taxane-based

anticancer drugs, drug discontinuation has been found to ameliorate

the symptoms; in such cases, the causative drug should not be

re-administered (25). Seewaldt

et al (26) reported that

paclitaxel-induced intestinal necrosis is caused not only by

toxicity to the intestinal epithelium, but also by a history of

laparotomy, cancer progression, intraperitoneal radiotherapy and

chemotherapy. Intestinal necrosis occurs because of the effects of

paclitaxel on the intestinal epithelium in the intestinal tract,

where mucosal damage occurs. In the present case, the patient had a

history of surgery for colonic polyps and the necrotic segment of

the colon that was resected was the same segment previously

containing the polyps. Therefore, intestinal mucosal damage had

already occurred. In this case, the administration of anticancer

drugs was thought to be the cause of intestinal necrosis.

Furthermore, lower gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a large

amount of stool, and increased intestinal pressure owing to

constipation was considered a contributing factor to the onset of

NOMI. In cases of delayed diagnosis, the prognosis is poor, with a

mortality rate of 58-70%, being the highest for those with AMI

(1). The underlying reason for this

is the lack of distinctive clinical symptoms, leading to a delayed

diagnosis (27). In the early

stages of onset, 20-30% of the patients do not complain of

abdominal pain. When abdominal pain does occur, its location and

severity can vary widely. However, as ischaemia progresses,

patients typically develop persistent abdominal pain, melena and

flatulence. With further disease progression, symptoms of

peritoneal irritation, such as muscular guarding and Blumberg's

sign, become evident (2,5). Blood tests show elevated levels of

C-reactive protein, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine

aminotransferase, creatine phosphokinase, lactate dehydrogenase and

lactate, as well as metabolic acidosis, but these are not specific

to the diagnosis of NOMI (2). The

usefulness of CT in the diagnosis of NOMI has been reported

(29). In the past, diagnosis with

CT was considered difficult, but in recent years, advances in

multidetector-CT have improved the ability to visualise blood flow

in the blood vessels, intestines and mesentery, thereby improving

the diagnostic performance. Contrast-enhanced CT is essential for

diagnosis, and findings, such as decreased or absent contrast

effects on the intestinal wall, which are signs of intestinal

ischaemia, can be observed. In the present case, NOMI was suspected

and additional contrast-enhanced CT revealed ischaemia from the

transverse colon to the descending colon. Treatment with

vasodilators is considered useful if there is no intestinal

necrosis; however, surgery is required if the intestinal tract has

reached an irreversible ischaemic state (2,5,6).

Therefore, early diagnosis of intestinal necrosis, which indicates

the need for surgery, is crucial. NOMI can manifest as a shock and

can be fatal, requiring immediate surgical treatment (2). If abdominal symptoms such as abdominal

pain and vomiting occur during drug therapy, intestinal ischaemia

should be suspected and discontinuation of anticancer drugs should

be considered.

| Table IPreviously reported cases of

non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia during drug therapy. |

Table I

Previously reported cases of

non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia during drug therapy.

| Author(s), year | Age, years/sex | Cancer type | Drug therapy

regimen | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pearson et al,

2008 | 53/female | Metastatic liver

cancer | CDDP, ADM MMC | Survival | (12) |

| Yoshida et al,

2020 | 63/female | Oropharyngeal

cancer | DOC, CDDP, 5-FU | Death | (5) |

| Yoshida et al,

2020 | 71/male | Oropharyngeal

cancer | DOC, CDDP, 5-FU | Death | (5) |

| Tanaka et al,

2018 | 74/male | Oropharyngeal

cancer | DOC, CDDP, 5-FU | Survival | (13) |

| Wada et al,

2017 | 79/male | Prostate cancer | DOC | Survival | (14) |

| Wada et al,

2017 | 74/male | Oropharynx

cancer | DOC, CDDP, 5-FU | Survival | (14) |

| Ikeda et al,

2007 | 84/female | Breast cancer | PTX | Survival | (15) |

| Awano et al,

2013 | 80/female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | Gefitinib | Death | (16) |

| Matsuzawa et

al, 2015 | 74/female | Melanoma | PTX, CBDCA | Survival | (17) |

| Yamane et al,

2015 | 68/male | Small cell lung

cancer | CDDP, ETP | Survival | (18) |

| Nagano et al,

2021 | 74/male | Oropharyngeal

cancer | S-1 (+

radiation) | Death | (19) |

| Nagano et al,

2021 | 69/male | Oropharyngeal

cancer | DOC, CDDP, 5-FU | Death | (19) |

| Kuwayama et

al, 2022 | 58/male | Hodgkin lymphoma | Nivolumab | Survival | (20) |

| Oikawa et al,

2022 | 76/male | Glioblastoma | Bevacizumab | Death | (21) |

| Present case,

2024 | 85/male | Maxillary cancer | PTX, CBDCA, Cmab | Survival | - |

In conclusion, if a patient has a history of

abdominal surgery or evidence of intestinal mucosal disorders (such

as constipation), early imaging examinations (including

contrast-enhanced CT) and consultation with a gastroenterologist

should be considered to rule out NOMI.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their great appreciation to

Professor Kenichi Hirabayashi (Department of Diagnostic Pathology,

Faculty of Medicine, University of Toyama, Toyoma, Japan) and Dr

Takashi Minamisaka (Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Toyama

University Hospital, Toyoma, Japan) for histopathological

analysis.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AI, RI, KS, DT, MT and SY treated the patient with

PCE. AI, KS and KF performed the follow-up. AI, SY, RI and MN

drafted the manuscript. AI, RI, SY and MN prepared the figures and

table. AI, SY and MN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of this case report and the

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mazzei MA, Guerrini S, Cioffi Squitieri N,

Vindigni C, Imbriaco G, Gentli F, Berritto D, Mazzei FG, Grassi R

and Volterrani L: Reperfusion in non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia

(NOMI): Effectiveness of CT in an emergency setting. Br J Radiol.

89(20150956)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Suzuki S, Kondo H, Furukawa A, Kawai K,

Yamamoto M and Hirata K: The treatment and diagnosis of

non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI). J Abdom Emerg Med.

35:177–185. 2015.

|

|

3

|

Wiesner W, Khurana B, Ji H and Ros PR: CT

of acute bowel ischemia. Radiology. 226:635–650. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Furukawa A, Kanasaki S, Kono N, Wakamiya

M, Tanaka T, Takahashi M and Murata K: CT diagnosis of acute

mesenteric ischemia from various causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

192:408–416. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yoshida M, Kobayashi T and Hyodo M: Two

cases of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia after chemotherapy for

head and neck cancer. Pract Oto-Rinno-Laryngol. 113:175–181.

2020.

|

|

6

|

Yukaya T, Kajiyama K, Koga C, Abe T,

Harimoto N, Miyazaki M, Yamashita T, Kai M, Shirabe K and Nagaie T:

Study of predictive factors for the prognosis in patients with non

occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI). J Abdom Emerg Med.

31:1009–1014. 2011.

|

|

7

|

Teasdale G and Jennett B: Assessment of

coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet.

2:81–84. 1974.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ende N: Infarction of the bowel in cardiac

failure. N Engl J Med. 258:879–881. 1958.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Heer FE, Silen W and French SW: Intestinal

gangrene without apparent vascular occlusion. Am J Surg.

110:231–238. 1965.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yamakoshi H, Kanai T, Kurihara H, Ishikawa

T, Ozawa K and Ueno H: Clinical study on forty-six cases of

ischemic colitis. J Jpn Soc Coloproctol. 55:307–312. 2002.

|

|

12

|

Pearson AC, Steinberg S, Shah MH and

Bloomston M: The complicated management of a patient following

transarterial chemoembolization for metastatic carcinoid. World J

Surg Oncol. 6(125)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tanaka H, Tsukahara K, Okamoto I, Kojima

R, Hirasawa K and Sato H: A case of septicemia due to nonocclusive

mesenteric ischemia occurring in induction chemotherapy. Case Rep

Otolaryngol. 2018(7426819)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wada T, Katsumata K, Kuwahara H, Matsudo

T, Murakoshi Y, Shigoka M, Enomoto M, Ishizaki T, Kasuya K and

Tsuchida A: Two cases of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia that

developed after chemotherapy. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 44:1396–1398.

2017.PubMed/NCBI(In Japanese).

|

|

15

|

Ikeda K, Hanba H, Nagano k, Shimizu S,

Nakazawa K, Nishiguchi Y, Ogawa Y and Inoue K: Paclitaxel (Taxol)

associated bowels necrosis in the patient with local progressive

breast cancer. J Jpn Coll Surg. 32:638–642. 2007.

|

|

16

|

Awano N, Kondoh K, Andoh T, Ikushima S,

Kumasaka T and Takemura T: Three cases of lung carcinoma

complicated by gastrointestinal necrosis and perforation. Jpn J

Lung Cancer. 53:809–814. 2013.

|

|

17

|

Matsuzawa M, Harada K, Hosomura N, Amemiya

H, Ando N, Inozume T, Kawamura T, Shibasaki N and Shimada S:

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia after chemotherapy for metastatic

melanoma. J Dermatol. 42:105–106. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Yamane H, Fukuda N, Nishino K, Yoshida K,

Ochi N, Yamagishi T, Honda Y, Kawamoto H, Monobe Y, Mimura H, et

al: Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia after splenic metastasectomy

for small-cell lung cancer. Intern Med. 54:743–747. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nagano H, Fujiwara Y, Matsuzaki H,

Umakoshi M, Ohori J and Kurono Y: Three cases of non-occlusive

mesenteric ischemia that developed after head and neck cancer

therapy. Auris Nasus Larynx. 48:1193–1198. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kuwayama N, Hoshino I, Gunji H, Kurosaki

T, Nabeya Y and Takayama W: A case of NOMI during treatment with

nivolumab for recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma. J Jpn Surg Assoc.

83:92–97. 2022.

|

|

21

|

Oikawa N, Kinoshita M, Yamamura M, Uno T,

Ichinose T, Sabit H, Hayashi T, Inoue D, Harada K and Nakada M:

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia during bevacizumab treatment for

glioblastoma: A case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 164:2767–2771.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Klauber N, Parangi S, Flynn E, Hamel E and

D'Amato RJ: Inhibition of angiogenesis and breast cancer in mice by

the microtubule inhibitors 2-methoxyestradiol and taxol. Cancer

Res. 57:81–86. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Britt LG and Cheek RC: Nonocclusive

mesenteric vascular disease: Clinical and experimental

observations. Ann Surg. 169:704–711. 1969.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kikuchi O, Saito D, Ikezaki O, Mitsui T,

Miura M, Sakuraba A, Yamada Y, Hayashida M, koyama G, et al: A case

of Ischemic colitis occurring in chemotherapy for ovarian cancer.

Prog Dig Endosc. 88:69–72, 61. 2016.

|

|

25

|

Nakamura S, Nogami K, Hida N, Iimuro M,

Yokoyama Y, Kamikozuru K, Nakamura M, Kawai M, Fukunaga K, et al:

Two cases of ischemic colitis associated with paclitaxel-based

chemotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer. 48:1785–1790.

2013.

|

|

26

|

Seewaldt VL, Cain JM, Goff BA, Tamimi H,

Greer B and Figge D: A retrospective review of

paclitaxel-associated gastrointestinal necrosis in patients with

epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 67:137–140.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Al-Diery H, Phillips A, Evennett N,

Pandanaboyana S, Gilham M and Windsor JA: The pathogenesis of

nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia: Implications for research and

clinical practice. J Intensive Care Med. 34:771–781.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mitsuyoshi A, Obama K, Shinkura N, Ito T

and Zaima M: Survival in nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia: Early

diagnosis by multidetector row computed tomography and early

treatment with continuous intravenous high-dose prostaglandin E(1).

Ann Sur. 246:229–235. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Woodhams R, Nishimaki H, Fujii K, Kakita S

and Hayakawa K: Usefulness of multidetector-row CT (MDCT) for the

diagnosis of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI): Assessment

of morphology and diameter of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA)

on multi-planar reconstructed (MPR) images. Eur J of Radio.

76:96–102. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|