Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), either alone or

in combination, increase survival of patients with several types of

malignant tumor and are currently being studied in the context of

neoadjuvant and adjuvant care for multiple diseases. However, these

monoclonal antibodies, targeting programmed cell death (PD)-1, PD-1

ligand (PDL-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA)-4, are

associated with a unique spectrum of adverse consequences that can

affect virtually every organ in the body. These include autoimmune

inflammation in the digestive tract, lung, skin, endocrine glands

and peripheral and central nervous systems (1,2). ICIs

have been shown to increase survival of patients with metastatic

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without activating genetic

alteration in EGFR, ALK or reactive oxygen species and are now

standard of care for these patients (3,4).

ICI-related pneumonitis (ICI-P) affects 3-5% of

patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors (5,6). It

appears to be more prevalent in patients with NSCLC than in those

with other types of cancer (6,7).

Similarly, it is more common in patients treated with PD-1/PDL-1

inhibitors than in those treated with CTLA-4 inhibitors alone

(6). The frequency of ICI-P is

higher when anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 are administered

concomitantly (6,7). Despite the low fatality rate of ~1%,

pneumonitis is one of the leading causes of ICI-associated

morbidity (8).

Treatment of ICI-P depends on its severity: The

majority of patients experience only mild to moderate pneumonitis

and improve with withdrawal of immunotherapy and/or a course of

corticosteroids (9,10). However, certain patients worsen

during treatment of pneumonitis and require additional

immunosuppressive therapy, such as infliximab, mycophenolate

mofetil (9,10) or immunomodulatory agents, such as

intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (11). The clinical course may be further

complicated by opportunistic infection, secondary to prolonged

treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants (12,13).

The clinical course of cytomegalovirus (CMV)

pneumonia is typically indolent but fulminant disease may be

observed in immunocompromised patients and carries a mortality risk

mortality >30% (14). CMV

pneumonia has been infrequently described in patients receiving

cancer immunotherapy. Here, we describe a patient that developed

fatal CMV pulmonary infection following treatment for pneumonitis

induced by the anti PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab.

Case report

A 63-year-old man with a medical history of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus

was diagnosed with metastatic squamous cell lung carcinoma in May

2017 (Fig. 1). Tumor cells stained

positively for PDL-1 with a count >50%, and the patient started

treatment with pembrolizumab in June 2017.

In February 2019, a PET-CT scan showed no

pathological uptake and the patient was in complete remission. The

only side effect noted at that time was hypothyroidism, which was

treated with levothyroxine.

In June 2019, the patient was admitted to Galilee

Medical Center (Nahariya, Israel) due to respiratory distress and

pulmonary infiltrates. He was treated with prednisone (1 mg/kg) and

levofloxacin and discharged following improvement with a

recommendation to taper the dose of prednisone. While receiving 10

mg prednisone, he experienced worsening dyspnea and was

re-admitted.

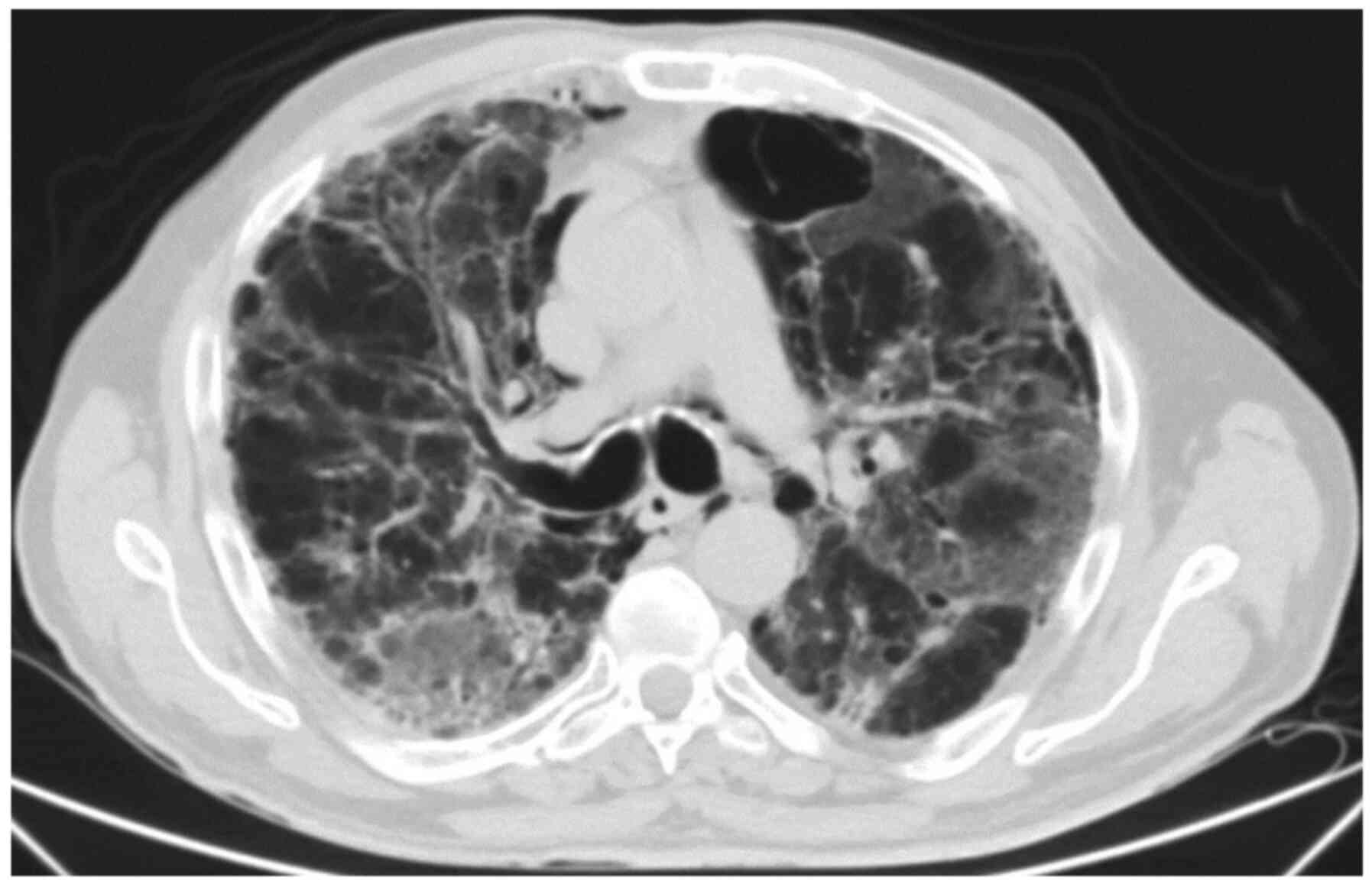

On admission, the patient was tachypneic, but other

vital signs were within the normal range. Blood oxygen saturation

was 82% on ambient air. CT angiography demonstrated bilateral

reticular opacities (Fig. 2).

The clinical course and imaging studies were

consistent with grade 4 autoimmune pneumonitis secondary to ICIs in

a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The patient

was treated with Prednisone 2 at a dose of 2 mg/kg, mycophenolate

mofetil, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Despite these measures, his

condition worsened and the patient was intubated and mechanically

ventilated due to respiratory failure.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit

and IVIG was added to his treatment regimen. While intubated, he

underwent bronchoscopy and lavage, which was analyzed for potential

infectious agents. Following PCR analysis, CMV DNA was detected in

the lavage fluid and CMV IgM was detected in the serum. Both tests

supported the diagnosis of CMV pneumonia. Additionally, workup for

Pneumocystis carinii (PCP), Ziehl-Neelsen staining and

bacterial and fungal cultures were negative, and anti-viral

treatment with Ganciclovir was added to his treatment regimen.

The patient was weaned off mechanical ventilation

after two weeks and admitted to the Department of Oncology with

high flow oxygen support and continued antiviral therapy,

prednisone (slowly tapered to 0.5 mg/kg) and prophylactic

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, despite these measures, his

condition continued to deteriorate. After discussion with the

patient and his family, the decision was made to avoid repeat

intubation. The patient died 3 weeks later.

Discussion

We describe a patient that suffered from ICI-P

complicated by CMV pneumonia, diagnosed by serology and a positive

PCR test using pulmonary lavage. An autopsy with pathology review

of lung tissue would constitute a definitive diagnostic test to

support CMV pneumonia diagnosis, however the family declined this

procedure. The clinical course, consisting of an initial

improvement with steroids and subsequent deterioration and

unresponsiveness to aggressive immune suppression, together with

positive serological and PCR tests, support the diagnosis of CMV

pneumonia in this patient. To the best of our knowledge, this is

the first published report of CMV pneumonia complicating ICI-P.

Although the majority of patients with pneumonitis

secondary to ICIs recover with corticosteroid treatment, fatalities

may occur. It is important to recognize factors that may complicate

the clinical course in these patients so they can be diagnosed and

promptly treated. The clinical and radiological findings suggestive

of CMV pneumonia are non-specific, overlapping with those of

immune-mediated pneumonitis (15-17).

Thus, a high degree of clinical suspicion is needed for early

diagnosis. The present patient was treated with steroids for

several weeks before diagnosis of CMV pneumonia, and doses were

tapered, as aforementioned, suggesting that this complication can

occur even after a relatively short course of steroids.

The range of clinical diseases due to CMV in

immunocompromised patients is broad and includes hepatitis,

retinitis, encephalitis, esophagitis and colitis (18). Our case demonstrates that workup for

CMV infection should be administered in patients failing to improve

with steroids for immune-mediated toxicity.

We report a case of fatal CMV pneumonia complicating

ICI-P. A high degree of clinical suspicion and prompt evaluation

for CMV infection is recommended in cases that do not improve with

steroids for treatment of immunotherapy-associated adverse effects

and in patients that relapse following initial improvement.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AS was responsible for conception of the work, data

acquisition and analysis, revising and finalizing the manuscript.

OB was responsible for data acquisition and analysis, drafting and

revising the manuscript. AO was responsible for acquisition and

analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

De Velasco G, Je Y, Bossé D, Awad MM, Ott

PA, Moreira RB, Schutz F, Bellmunt V, Sonpavde GP, Hodi FS and

Choueiri TK: Comprehensive meta-analysis of key immune-related

adverse events from CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in cancer

patients. Cancer Immunol Res. 5:312–318. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Postow MA, Sidlow R and Hellmann MD:

Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint

blockade. N Engl J Med. 378:158–168. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S,

Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, Domine M, Clingan P, Hochmair MJ,

Powell SF, et al: Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic

non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 378:2078–2092.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yuan M, Huang LL, Chen JH, Wu J and Xu Q:

The emerging treatment landscape of targeted therapy in

non-small-cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

4(61)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wang H, Guo X, Zhou J, Li Y, Duan L, Si X

and Zhang L, Liu X, Wang M, Shi J and Zhang L: Clinical diagnosis

and treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated

pneumonitis. Thorac Cancer. 11:191–197. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cadranel J, Canellas A, Matton L, Darrason

M, Parrot A, Jean-Marc N, Lavolé A, Anne-Marie R and Fallet V:

Pulmonary complication for immune checkpoint inhibitors in patient

with nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir Revc.

28(190058)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ma K, Lu Y, Jiang S, Tang J, Li X and

Zhang Y: The relative risk and incidence of immune checkpoint

inhibitors related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: A

meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 9(1430)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR,

Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD,

Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al: Safety, activity, and immune

correlates of anti-pd-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med.

366:2443–2454. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC,

Schindler K, Lacouture ME, Postow MA and Wolchok JD: Toxicities of

the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Annals

of Oncology. Ann Oncol. 26:2375–2391. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ,

Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, Chau I, Ernstoff MS, Gardner

JM, Thompson JA, et al: Management of immune-related adverse events

in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy:

American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline.

J Clin Oncol. 36:1714–1768. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Petri CR, Patell R, Batalini F, Rangachari

D and Hallowell RW: Severe pulmonary toxicity from immune

checkpoint inhibitor treated successfully with intravenous

immunoglobulin: Case report and review of the literature. Respir

Med Case Rep. 27(100834)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Stuck AE, Minder CE and Frey FJ: Risk of

infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids.

Rev Infect Dis. 11:954–963. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Fishman JA: Opportunistic

infections-coming to the limits of immunosuppression. Cold Spring

Harb Perspect Med. 3(a015669)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Konoplev S, Champlin RE, Giralt S, Ueno

NT, Khouri I, Raad I and Whimbey E: Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in

adult autologous blood and marrow transplant recipients. Bone

Marrow Transplantationc. 27:877–881. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Travi G and Pergam SA: Cytomegalovirus

pneumonia in hematopoietic stem cell recipients. J Intensive Care

Med. 29:200–212. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Franquet T, Lee KS and Müller NL:

Thin-section CT findings in 32 immunocompromised patients with

Cytomegalovirus pneumonia who do not have AIDS. Am J Roentgenol.

181:1059–1063. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kang EY, Patz EF Jr and Müller NL:

Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in transplant patients: CT findings. J

Comput Assist Tomogr. 20:295–299. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, Josephson

F, Lundgren J, Nichols G, Pikis A, Razonable RR, Miller V and

Griffiths PD: Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease

in transplant patients for use in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis.

64:87–91. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|