Introduction

All orbital tissues, including extra-ocular muscles,

can be affected by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) (1). However, <10% of all patients with

VZV infections present with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Notably,

there is a great variability as regards orbital involvement,

affecting 20-70% of individuals with herpes zoster ophthalmicus

(2). Usually, ophthalmic

complications of herpes zoster opthalmicus occur between 5 and 14

days following cutaneous lesions (3).

The present study reports the case of a middle-aged

male patient presenting with orbital myositis due to herpes zoster

ophthalmicus prior to the appearance of vesicular lesions. To the

authors' knowledge, there are only four cases reported in the

literature of herpes zoster ophthalmicus with orbital myositis

prior to the appearance of vesicular lesions (4-7).

Case report

A 56-year-old male patient with a prior medical

history of hyperlipidemia, and who was not on pharmacotherapy,

arrived at the Emergency Department of Cooper University Hospital,

Camden, NJ, USA with an acute intractable right-sided headache. His

headache began 3 days prior to his presentation and was described

as primarily right-sided with radiation to the neck, along with

associated fevers, blurred vision and photophobia. He stated he was

cleaning out an old farm devoid of animals during the onset of the

headache. Of note, the patient had no prior history of headaches,

and his only medication has been testosterone cypionate by

intramuscular route once every 4 weeks over the past 6 months. He

had no previous surgical history and no pertinent family history of

neuropsychiatric disorders.

In the emergency department, an examination of his

vital signs revealed a temperature of 98.5 F, a blood pressure of

141/67 mmHg, a heart rate of 88 beats per minute and an oxygen

saturation of 96% in room air. A cardiopulmonary examination did

not reveal any notable findings. A head examination revealed

normocephalic and atraumatic findings, with normal bilateral

external ear canals. His neurological examination yielded normal

results. His sensory and motor examination revealed no focal

deficits and his coordination was normal. There was no evidence of

skin changes. In consideration of a differential inclusive of

intracranial hemorrhage vs. meningitis vs. venous thrombosis

secondary to anabolic abuse, a thorough workup was performed,

including a cranial computed tomography (CT) scan, cranial

CT-venogram and a lumbar puncture.

The cranial CT and CT venogram scans did not reveal

any notable findings. The lumbar puncture demonstrated a protein

level of 38 mg/dl, glucose level of 65 mg/dl and an acellular fluid

analysis. However, polymerase chain reaction of the cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) revealed a positive result for VZV. The patient was

thus commenced on intravenous treatment with acyclovir at 10 mg/kg

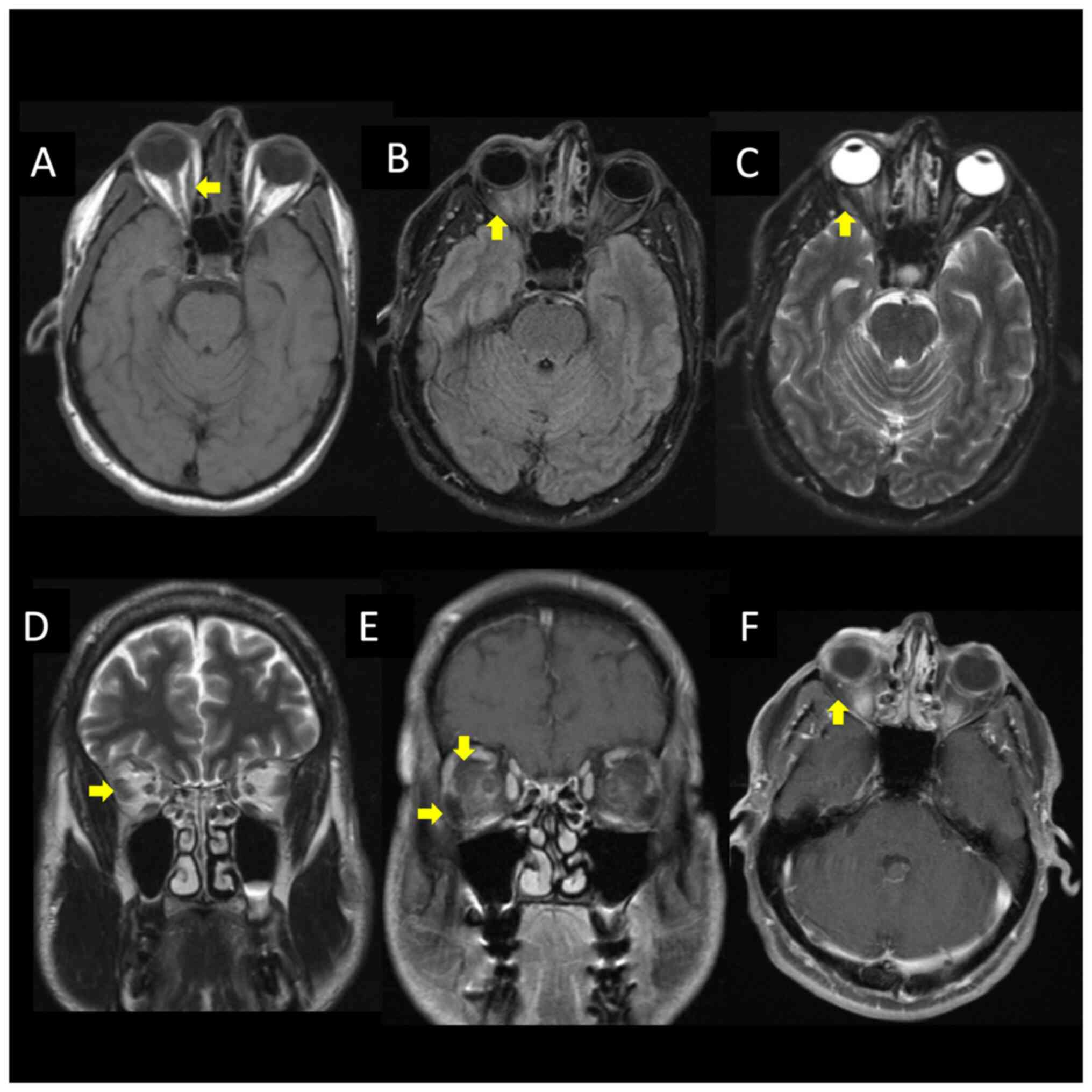

every 8 h, and a follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging was

performed, revealing bilateral intraorbital intraconal enhancement

consistent with herpes zoster ophthalmicus with myositis (Fig. 1). An infectious disease consult was

pursued, and a course of intravenous acyclovir was continued

throughout his hospitalization period. The results of the complete

assessment of all the laboratory tests performed are presented in

Table I.

| Table ILaboratory tests performed for the

patent in the present study. |

Table I

Laboratory tests performed for the

patent in the present study.

| Laboratory tests | Results |

|---|

| Complete blood cell

count | White blood cells

(5.41; 10x3/µl), red blood cells (5.7 10x6/µl), hemoglobin (16.9

g/dl), hematocrit (49.50%), mean corpuscular volume (86.8 fl), mean

corpuscular hemoglobin (29.6 pg), mean corpuscular hemoglobin

concentration (34.1 g/dl), red cell distribution width (12.80%),

platelet count (212; 10x3/µl), basophils (0.40%), eosinophils

(1.50%), granulocytes (53.50%), lymphocytes (29.20%) and monocytes

(14.8%) |

| Basic metabolic

panel | Glucose (83 mg/dl),

blood urea nitrogen (12 mg/dl), creatinine (1.32 mg/dl), sodium

(141 mmol/l), potassium (5.1 mmol/l), chloride (105 mmol/l),

CO2 (24 mmol/l), calcium (9.2 mg/dl), eGFR [63

ml/min/(1.73_m2)] |

| HIV antibody | Non-reactive |

| HIV p24 antigen | Non-reactive |

| COVID-19 PCR | Negative |

| Influenza A | Negative |

| Influenza B | Negative |

| Lyme antibody | Negative |

| Cerebrospinal fluid

analysis | Appearance (clear and

colorless), protein (38 mg/dl), corrected nucleated cells (2/µl),

red blood cells (<1/µl), glucose (65 mg/dl), cryptococcal

antigen (negative) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid

polymerase chain reaction | Escherichia

coli (negative), Neisseria meningitidis (negative),

Haemophilus influenzae (negative), Listeria

monocytogenes (negative), Group B streptococcus

(negative), Streptococcus pneumoniae (negative),

Cryptococcus neoformans (negative),

Cytomegalovirus (negative), Herpes simplex virus 1

and 2 (negative), Enterovirus (negative), varicella zoster

virus (positive) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid

cultures | Acid-fast bacteria

(no growth), cerebrospinal fluid fungal (no growth), cerebrospinal

fluid (no growth) |

During his admission, the symptoms of the patient

evolved into a shock-like pain over the scalp associated with pain

in ocular movements. His clinical course was further complicated by

a follicular reaction on the palpebral conjunctiva, which was

determined to be a viral follicular conjunctivitis likely secondary

to the VZV. On the 2nd day of admission, he developed new vesicular

lesions found on the right-side cranial nerve V1 dermatome

(Fig. 2). On the 4th day of

admission, he began to experience relief from his headache and

ocular disturbances. By the 6th day of admission, he had

experienced the complete resolution of his symptoms, and his

physical examination revealed the resolution of the dermatologic

manifestations of the VZV. The culture of his CSF remained

negative. The patient was stable for outpatient follow-up with

ophthalmology and was discharged on an oral valacyclovir (1 g, 2

tablets every 6 h) course for 7 days.

Discussion

Orbital myositis is characterized by worsening pain

with eye movements. Other common features in individuals with

orbital myositis are proptosis, swollen eyelids and hyperemic

conjunctiva. Common causes of orbital myositis are thyroid disease,

syphilis and auto-immune diseases, which were not observed in the

patient described herein. His ocular pain related to eye movements

significantly improved after treatment with acyclovir was

commenced, and he fully recovered within 1 week of therapy.

The patient was treated with acyclovir intravenously

when he was hospitalized and his treatment regiment was then

changed to oral valacyclovir for a period of 7 days. As clinical

signs and symptoms associated with VZV, the CNS infection improved

and the patient was able to take oral medications; therapy was thus

completed with oral treatment. Acyclovir and valacyclovir are both

effective against VZV CNS infections. Notably, acyclovir, compared

to valacyclovir, has some drawbacks, including dosing at multiple

times per day, poor oral bioavailability and inadequate CNS

penetration/levels, which render oral acyclovir a suboptimal option

for such cases (8).

A previous study by Marsh and Cooper (9), using a large cohort, assessed 1,356

patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. That study found that

extraocular muscle involvement was associated with the appearance

of skin lesions and that the severity of the rash was related to

recurrence and postherpetic neuralgia. However, that study did not

describe neuroimaging analyses (9).

In addition, to date, to the best of our knowledge, there are no

radiological and histopathological studies available associating

orbital myositis with herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

In 1948, Parkinson (10) described a case of herpes zoster

ophthalmicus followed by ptosis on the same side. He reported that

idiopathic cases of myositis should be reserved only after the

availability of negative serological and immunological results for

herpes zoster (10). Of note, 10

years later, Lewis (11) reported a

syndrome known as ‘ophthalmic zoster sine herpete’, characterized

by orbital pain, extraocular palsy and periorbital skin swelling

without skin rashes.

In the case in the present study, the patient

developed a significant headache with concern from vascular

etiology. Following initial neuroimaging, the CSF was analyzed, and

the VZV infection was noticed. A possible explanation for the

headache could be related to prodromal symptoms or myositis

affecting the extraocular muscles. Ophthalmic complications

following herpes zoster ophthalmicus may result from inflammatory

changes, nerve damage, or secondary tissue scarring.

The authors searched six databases to locate studies

describing the appearance of myositis prior to skin manifestations

in individuals with herpes zoster ophthalmicus published from 1991

to January, 2024 in electronic form. The Excerpta Medica (Embase),

Google Scholar, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences

Literature (Lilacs), Medline, Scientific Electronic Library Online

(SciELO), and ScienceDirect databases were searched. Publications

in the English language were included in the search (Table II).

| Table IICases reported in the literature of

orbital myositis preceding skin symptoms in patients with varicella

zoster infection. |

Table II

Cases reported in the literature of

orbital myositis preceding skin symptoms in patients with varicella

zoster infection.

| Author(s), year of

publication | Age (years)/sex | Comorbidities | Timea (days) | Neurologic

manifestations | Management and

outcomes | Comments | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Volpe and Shore,

1991 | 45/M | Colitis | 3 | Proptosis | Initially, oral

prednisone for idiopathic orbital inflammation was prescribed.

After the skin lesion appeared, oral acyclovir and prednisone for

three days were prescribed. After three days, the symptoms

returned, and he received seven days of the same therapy. A

complete imaging resolution was observed within seven weeks. | First report. Only a

cranial CT scan was performed. | (4) |

| Kawasaki and Borruat,

2003 | 47/F | NA | 4 | Proptosis and pain

worsen with ocular movements | IV and topical

acyclovir, and. prednisone | First report with.

brain MRI | (5) |

| Tseng, 2008 | 54/M | Liver cirrhosis | 7 | Proptosis and pain

worsen with ocular movements | 7 Days of IV

acyclovir. treatment and discharged. After 7 days, he returned with

the same symptoms, and he received 7 days of valacyclovir. A

complete imaging resolution was observed within 3 months. PHN was

observed at the follow-up | Visual evoked

potential was normal. Hutchinson's sign. | (6) |

| Bak et al,

2018 | 59/F | Healthy | 8 | Proptosis | IV dexamethasone 10

mg once a day for 2 days and oral famciclovir 750 mg once a day for

10 days were administered. Oral prednisolone 10 mg once a day for

10 days was prescribed. | Dacryoadenitis. | (7) |

| Rissardo et

al | 56/M | Hyperlipidemia | 5 | Pain worsening with

ocular movements | IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg

every 8 h for 6 days, followed by oral valacyclovir course for 7

days. | | Present study |

To the authors' knowledge, Volpe and Shore (4) described the first case of orbital

myositis appearing before skin manifestations in individuals with

herpes zoster ophthalmicus. They reported the enlargement of

extraocular muscles with tendon sparing on a cranial computed

tomography scan, which appeared one day before the appearance of

the skin rashes.

Oh et al (12)

reported a patient presenting with eyelid swelling and headache;

that study is not included in Table

II. They described it as rare, as they considered only

vesicular rashes as a skin manifestation (12). Nevertheless, that case illustrates a

common presentation of individuals with herpes zoster with skin

lesions appearing prior to orbital myositis (8). In addition, Park and Lee (13), Chiang et al (14), Bae and An (15) and Pereira et al (16) and the first patient reported by Bak

et al (7) developed

periorbital erythematous edema at presentation; these studies are

not included in Table II.

The general rule is that the optimal time for

initiating antiviral medication is within 72 h following the onset

of the vesicular rash. However, the role of systemic steroid

therapy in acute orbital syndromes caused by herpes zoster

ophthalmicus needs to be further investigated. In the case

described herein, this class of medication was not prescribed.

However, corticosteroids can attenuate the pain, and may also

influence the course of the viral infection by inflammatory

pathways.

A possible differential diagnosis for the case in

the present study is testosterone-induced myositis. The patient had

used testosterone for the past 6 months due to low testosterone

levels and symptoms of sexual dysfunction, mood disorder and

generalized weakness. Notably, testosterone-induced orbital

myositis is uncommonly observed in humans, although it is a common

finding in rat models (17).

However, myositis secondary to testosterone was considered unlikely

in the patient in the present study, as the patient had used

testosterone for a long period of tims and had VZV found in the

CSF.

In conclusion, patients with orbital pain who have a

significant headache should be further investigated. Herpes zoster

virus serology needs to be investigated before a final diagnosis of

idiopathic orbital myositis is made. The case described in the

present study favors management with oral antivirals following a

course of at least 5 days with intravenous medications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

All authors (JPR, ALFC and PP) contributed to the

diagnosis and treatment of the patient, and to the conception of

the study. JPR was a major contributor to the writing of the

manuscript. JPR and PP confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study followed international and

national regulations and was performed in agreement with the

Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical principles. The patient signed

an informed consent form.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of any data and/or accompanying images. Patients

have a right to anonymity and privacy, and authors have a legal and

ethical responsibility to respect this right.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gurwood AS, Savochka J and Sirgany BJ:

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Optometry. 73:295–302. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

McCrary ML, Severson J and Tyring SK:

Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 41:1–14.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Vardy SJ and Rose GE: Orbital disease in

herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Eye (Lond). 8:577–579. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Volpe NJ and Shore JW: Orbital myositis

associated with herpes zoster. Arch Ophthalmol. 109:471–472.

1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kawasaki A and Borruat FX: An unusual

presentation of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: Orbital myositis

preceding vesicular eruption. Am J Ophthalmol. 136:574–575.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tseng YH: Acute orbital myositis heralding

herpes zoster ophthalmicus: Report of a case. Acta Neurol Taiwan.

17:47–49. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bak E, Kim N, Khwarg SI and Choung HK:

Case series: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with acute orbital

inflammation. Optom Vis Sci. 95:405–410. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Cunha BA and Baron J: The pharmacokinetic

basis of oral valacyclovir treatment of herpes simplex virus (HSV)

or varicella zoster virus (VZV) meningitis, meningoencephalitis or

encephalitis in adults. J Chemother. 29:122–125. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Marsh RJ and Cooper M: Ophthalmic herpes

zoster. Eye (Lond). 7:350–370. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Parkinson T: Rarer manifestations of

herpes zoster; a report on three cases. BMJ. 1:8–10.

1948.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lewis GW: Zoster sine herpete. BMJ.

2:418–421. 1958.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Oh HY, Cho SW and Kim SH: Herpes zoster

ophthalmicus presenting as acute orbital myositis preceding a skin

rash: A case report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 66:213–216. 2012.

|

|

13

|

Park JH and Lee JE: An Unusual case of

orbital inflammation preceding herpes zoster ophthalmicus. J Korean

Ophthalmol Soc. 58:1099–1105. 2017.

|

|

14

|

Chiang E, Bajric J and Harris GJ: Herpes

zoster ophthalmicus with orbital findings preceding skin rash.

Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 34:e113–e115. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bae DW and An JY: Herpes zoster

ophthalmicus presenting as acute orbital inflammation preceding the

vesicular rash. J Neurosonology Neuroimaging. 12:91–94. 2020.

|

|

16

|

Pereira A, Zhang A, Maralani PJ and

Sundaram AN: Acute orbital myositis preceding vesicular rash

eruption in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Can J Ophthalmol.

55:e107–e109. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Bai X, Zhang X and Zhou Q: Effect of

testosterone on TRPV1 expression in a model of orofacial myositis

pain in the rat. J Mol Neurosci. 64:93–101. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|