Introduction

The budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae,

has been used to make bread and beer for thousands of years. As a

single-cell organism, budding yeast has been extensively

investigated in genetics and physiology as a model system for

eukaryotes, due to its well-annotated genome and short life cycle

(1). Completion of the budding yeast

genome sequencing project helped to determine a total of 6,275

genes on 16 chromosomes (12 million base pairs). Yeast possesses

23% homologous genes to humans; therefore, it is considered as a

useful model for gene function studies (2). Although yeast and human diverged from a

common ancestor ~1 billion years ago, lines of evidence demonstrate

the strong conservation of gene function between yeast and humans

(3).

The advancement of cDNA array technology and its low

cost make genome-wide gene expression analysis possible. There are

many transcriptome data of budding yeast in public databases,

including gene expression data from different nutritional

conditions, growth stages and gene knock-out models (4). A task for bioinformaticians is to

reanalyze these large-scale microarray data and next-generation

sequencing data, and identifying the hidden information within

these databases. Systems biology studies use high-throughput data

and mathematical models to construct yeast transcriptional, gene

regulation and protein interaction networks (5,6). The current

study used the Google Scholar search engine (https://scholar.google.com/) and, to the best of our

knowledge, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) has

not been applied to budding yeast. Using WGCNA to construct a yeast

gene co-expression network has many advantages. Firstly, individual

experiments may lose meaningful biological information due to

relatively small sample sizes and different statistical methods.

Pooling datasets from studies helps to strengthen statistical

power. Secondly, the gene co-expression analysis reduces

high-dimensional genome-wide gene expression to only tens of

modules, which simplifies the depiction of yeast biology functions.

Thirdly, functionally unknown genes are inferred from co-expressed

gene modules by the principle of guilt by association (7). Finally, the current analysis may provide

a paradigm for single-cell microorganism.

The aim of the present study was to construct a

budding yeast gene co-expression network and identify functional

modules that may represent different aspects of yeast biological

function. It is hypothesized that certain highly connected genes

may be involved in module function. The conservation of these

modules is further validated in human tumor cells, some of which

may differentiate the survival times of separate patients into long

and short.

Materials and methods

Microarray data processing

Yeast microarray data were downloaded from Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) (8). Detailed information of the 218 gene

expression datasets used in the current study are available at

Online Resource 1 (http://bioinformatics.fafu.edu.cn/Downloads.html).

To simplify the data analysis procedure and to enhance

reproducibility, only 2,814 budding samples from experiments run on

Affymetrix Yeast Genome 2.0 Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

Waltham, MA, USA) were included. Datasets from fission yeast was

excluded. Expression Console (version 1.2) (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa

Clara, CA, USA) was used to process raw data. Probe level

expression data were extracted using the MAS5.0 method and

normalized using the DNAMR package (http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~cabrera/DNAMR).

Weighted gene co-expression network

construction and module detection

Signed network was constructed according to WGCNA

protocols (9–11). The WGCNA R function was implemented

using the following parameters: power=12, minModuleSize=30,

deepSplit=4, networkType=‘signed’. Briefly, Pearson correlation

coefficients were calculated for all pair-wise comparisons of the

probes across all samples. The resulting correlation matrix was

converted into a matrix of connection strengths (that is, an

adjacency matrix) using the power function αij =

[0.5+0.5 × cor(xi,

xj)]β where xi and

xj are the i th and j th probe

expression, which resulted in a weighted network. Then topological

overlap measure (TOM) was calculated as follows:

TOM=Σu≠i,jaiuauj+aijmin(k.totali,k.totalj)+1–aij

Calculation of 1-TOM was performed as a biologically

meaningful measure of node similarity, representing how close the

neighbors of probe 1 were to the neighbors of probe 2. Probes were

hierarchically clustered using 1-TOM as the distance and modules

were determined by choosing a height cutoff of 0.995 for the

resulting dendrogram. Highly similar modules were identified by

clustering and merged together using a dynamic tree-cutting

algorithm (7). The module eigengene

(ME) corresponds to the first principal component of a given module

and is calculated as follows: ME =

princomp(xil(q)), where i corresponds

to module probes and l represents microarray samples in module q.

This may be considered as the most representative probe expression

in a module. Module membership (MM or kME) for each

probe in each module refers to the Pearson correlation between the

expression level of the probe and ME (7). MM was calculated by

Kcor,i(q) =

cor(xi,E(q)), where

xi is the profile of node i and

E(q) is the ME of module q. Hub genes were

defined as corresponding probes that have high module membership

values within a module (11). The

stability of each module was evaluated by sampling 1,407 samples

from all 2,814 samples 1,000 times. Correlation between

connectivity calculated from the sampled samples and the original

samples was represented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway

enrichment analysis

GO enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes pathway analysis for network modules were performed using

the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

(DAVID 6.7, https://david-d.ncifcrf.gov) with the background list

of all genes on the array (12–14). In

DAVID, the overrepresentation of a term is defined as a modified

Fisher's exact P-value with an adjustment for multiple tests using

the Benjamini-Hochberg method (15).

Survival analysis

A human breast cancer dataset, GSE31448, colorectal

cancer dataset, GSE17536, and sarcoma dataset, GSE21050 were

downloaded from the NCBI GEO database. Raw files were processed

using the Affymetrix Expression Console. The yeast module genes

were mapped to human genes using the NCBI HomoloGene system

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene). To obtain

the module expression value MEs, the three disease gene expression

datasets were projected to yeast modules according to homologous

genes. Patients were then separated into two groups with high and

low MEs. Survival analysis was conducted to compare the survival

time difference in R using the survival package. P-values for

survival curves were determined from the Kaplan-Meier survival

curves by use of the log-rank test.

Results

WGCNA

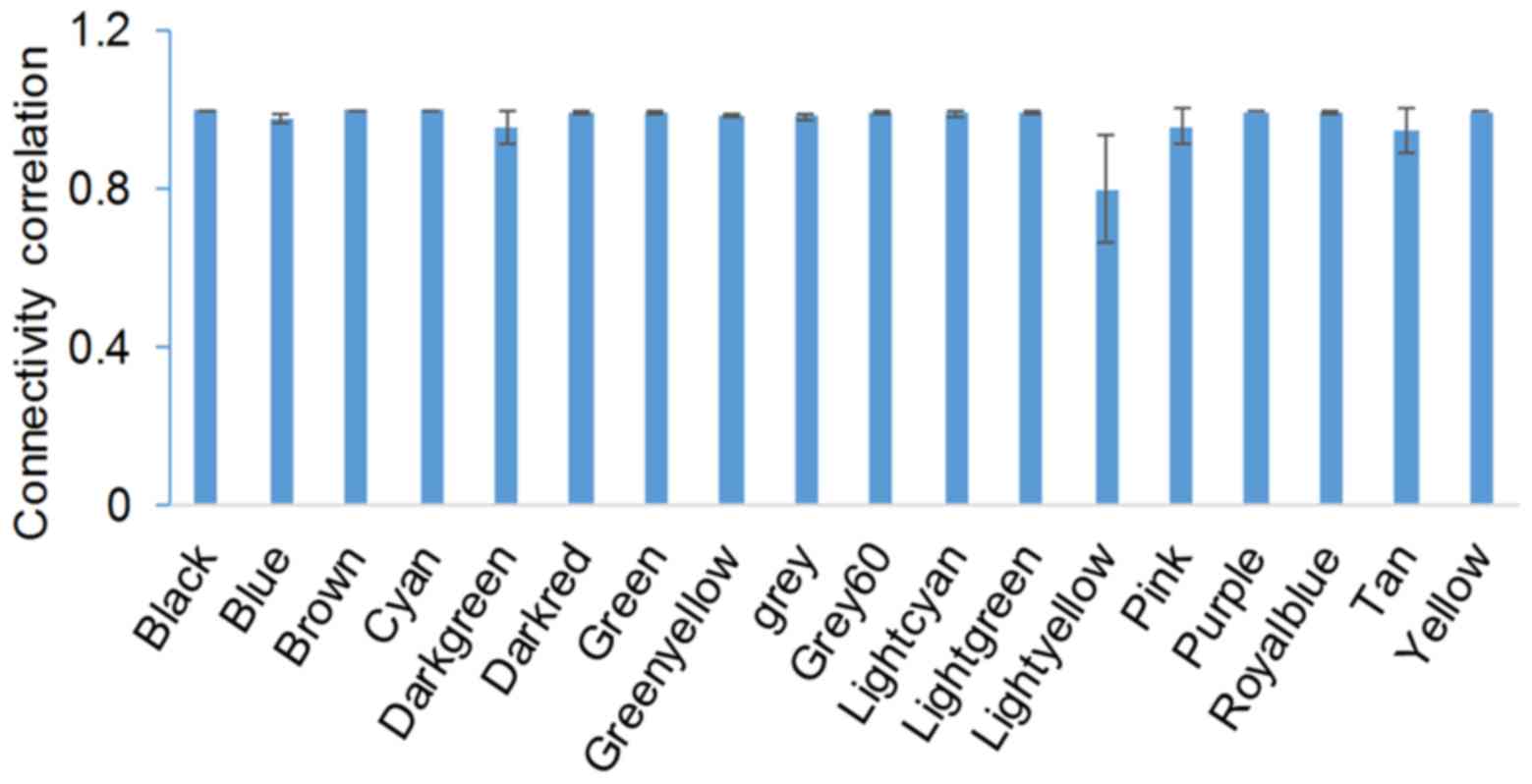

A large budding yeast gene co-expression network was

constructed in the present study, to the best of our knowledge, for

the first time. WGCNA identified 17 modules, which contained genes

with similar expression patterns. To evaluate the stability of

modules, gene connectivity was correlated before and after sampling

(Fig. 1). Module stability was

expressed as the correlation of intramodule connectivity between

the original and sampled module. The average correlation was

>0.8. Module Cyan was the most stable module, and module

Lightyellow was the least stable (Fig.

1). All gene modules and corresponding connectivity data are

provided in Online Resource 2 (http://bioinformatics.fafu.edu.cn/Downloads.html).

Modules are involved in different

functions

To identify modular features, DAVID was used to

characterize module genes (Table I).

All the modules were associated with distinct biological functions,

representing aspects of yeast cell function. Module yellow is

enriched with genes associated with ncRNA processing, which

predominantly localize in the nucleolus. Both modules cyan and

green-yellow were associated with mitochondria, while module cyan

encodes proteins involved with oxidative phosphorylation on

mitochondrial membranes, and module green-yellow encodes

mitochondrial ribosome proteins.

| Table I.GO and KEGG annotation of the

identified 17 gene co-expression modules in Saccharomyces

cerevisiae. |

Table I.

GO and KEGG annotation of the

identified 17 gene co-expression modules in Saccharomyces

cerevisiae.

|

| GO term

(Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Module (no.

genes) | Biological

process | Cellular

component | Molecule

function | KEGG

(Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value) |

|---|

| Black (277) | Response to heat

(1E-45) | Plasma membrane

(6E-11) | Aldehyde reductase

activity (9E-4) | Sucrose metabolism

(7E-7) |

| Blue (935) | Cell cycle phase

(8E-10) | Chromosome

(1E-8) | Protein kinase

activity (5E-2) | Cell cycle

(4E-12) |

| Brown (796) | Regulation of

translation (4E-27) | Cytosolic ribosome

(1E-80) | Structural

constituent of ribosome (5E-39) | Ribosome (5E-66) |

| Cyan (111) | Oxidative

phosphorylation (2E-38) | Mitochondrial

(4E-41) | Hydrogen ion

transmembrane transporter activity(4E-29) | Oxidative

phosphorylation (4E-31) |

| Dark green (37) | M phase of meiotic

cell cycle (2E-22) | Condensed nuclear

chromosome (3E-10) | Structure-specific

DNA binding (1E-04) | Meiosis (7E-7) |

| Dark red (49) | Amino acid

biosynthesis (2E-23) | Glycine cleavage

complex (7E-3) | Oxidoreductase

activity, acting on the CH-NH2 group of donors, disulfide as

acceptor (3E-2) | Arginine and proline

metabolism (3E-3) |

| Green (736) | Autophagy

(1E-19) | Vacuole (5E-4) | Transcription

regulator activity (9E-4) |

|

| Green yellow

(135) | Mitochondrial

translation (7E-98) | Mitochondrial

ribosome (7-E101) | Structural

constituent of ribosome (8E-69) | Aminoacyl-tRNA

biosynthesis (8E-7) |

| Grey 60 (84) | Steroid metabolism

(1E-5) | Intrinsic to

membrane (5E-7) | O-acyltransferase

activity (1E-3) |

|

| Light cyan

(85) | Ubiquitin-dependent

protein metabolism (1E-38) | Proteasome

(2E-58) | Threonine-type

endopeptidase activity (3E-21) | Proteasome

(2E-50) |

| Light green

(187) | Protein amino acid

glycosylation (2E-13) | Intrinsic to

membrane (4E-34) | Mannosyltransferase

activity(1E-3) | N-Glycan

biosynthesis (5E-9) |

| Light yellow

(57) | Oligosaccharide

metabolic process (3E-4) |

|

|

|

| Pink (194) | Sporulation

(5E-4) |

|

|

|

| Purple (143) | Organic acid

catabolic process (4E-11) | Microbody

(3E-17) | Ligase activity,

forming carbon-sulfur bonds (2E-2) | Glyoxylate and

dicarboxylate metabolism (5E-6) |

| Royal blue

(52) | Sulfur metabolism

(2E-25) |

| Sulfur amino acid

transmembrane transporter activity (6E-5) | Sulfur metabolism

(5E-10) |

| Tan (1851) | Monosaccharide

catabolic process (3E-2) | Cytosolic ribosome

(2E-10) | Structural

constituent of ribosome (9E-5) | Ribosome

(3E-10) |

| Yellow (666) | ncRNA processing

(1E-100) | Nucleolus

(2E-128) | DNA-directed RNA

polymerase activity (2E-14) | Pyrimidine

metabolism (9E-16) |

Functions of module hub genes

In a network biology, genes do not contribute

equally to a module. Those genes with higher connectivity may exert

more significant roles in a module. To establish the functional

annotation of those genes, the top hub genes were screened to

examine their functions (16). For

example, module blue was enriched in cell cycle-associated genes.

The top hub gene of the module was YDR506C, which contributes to

nuclear division and genome integrity (17,18). The

results are presented in Table

II.

| Table II.Hub genes and their encoding proteins

of the gene co-expression modules in Saccharomyces

cerevisiae. |

Table II.

Hub genes and their encoding proteins

of the gene co-expression modules in Saccharomyces

cerevisiae.

| Module | Gene | Encoding

protein |

|---|

| Black | DCS2 | Protein DCS2 |

| Blue | YDR506C | Putative

multicopper oxidase YDR506C |

| Brown | RPL22A | 60S ribosomal

protein L22-A |

| Cyan | SDH2 | Succinate

dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur subunit, mitochondrial |

| Dark green | IME2 | Meiosis induction

protein kinase IME2/SME1 |

| Dark red | ARG7 | Arginine

biosynthesis bifunctional protein ARG7, mitochondrial |

| Green | GPX1 | Glutathione

peroxidase 1 |

| Green yellow | MRPL49 | 54S ribosomal

protein L49, mitochondrial |

| Grey 60 | PAU5 | Seripauperin-5;

Seripauperin-7 |

| Light cyan | RPT4 | 26S protease

subunit RPT4 |

| Light green | ALG8 | Dolichyl

pyrophosphate Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 alpha-1,3-glucosyltransferase |

| Light yellow | PRP39 | Pre-mRNA-processing

factor 39 |

| Pink | MER1 | Meiotic

recombination 1 protein |

| Purple | FOX2 | Peroxisomal

hydratase-dehydrogenase-epimerase |

| Royal blue | MET16 |

Phosphoadenosinephosphosulfate

reductase |

| Tan | SPBC947.09 | Uncharacterized

protein C947.09 |

| Yellow | RPF2 | Ribosome biogenesis

protein RPF2 |

Module conservation in human cancer

cell lines

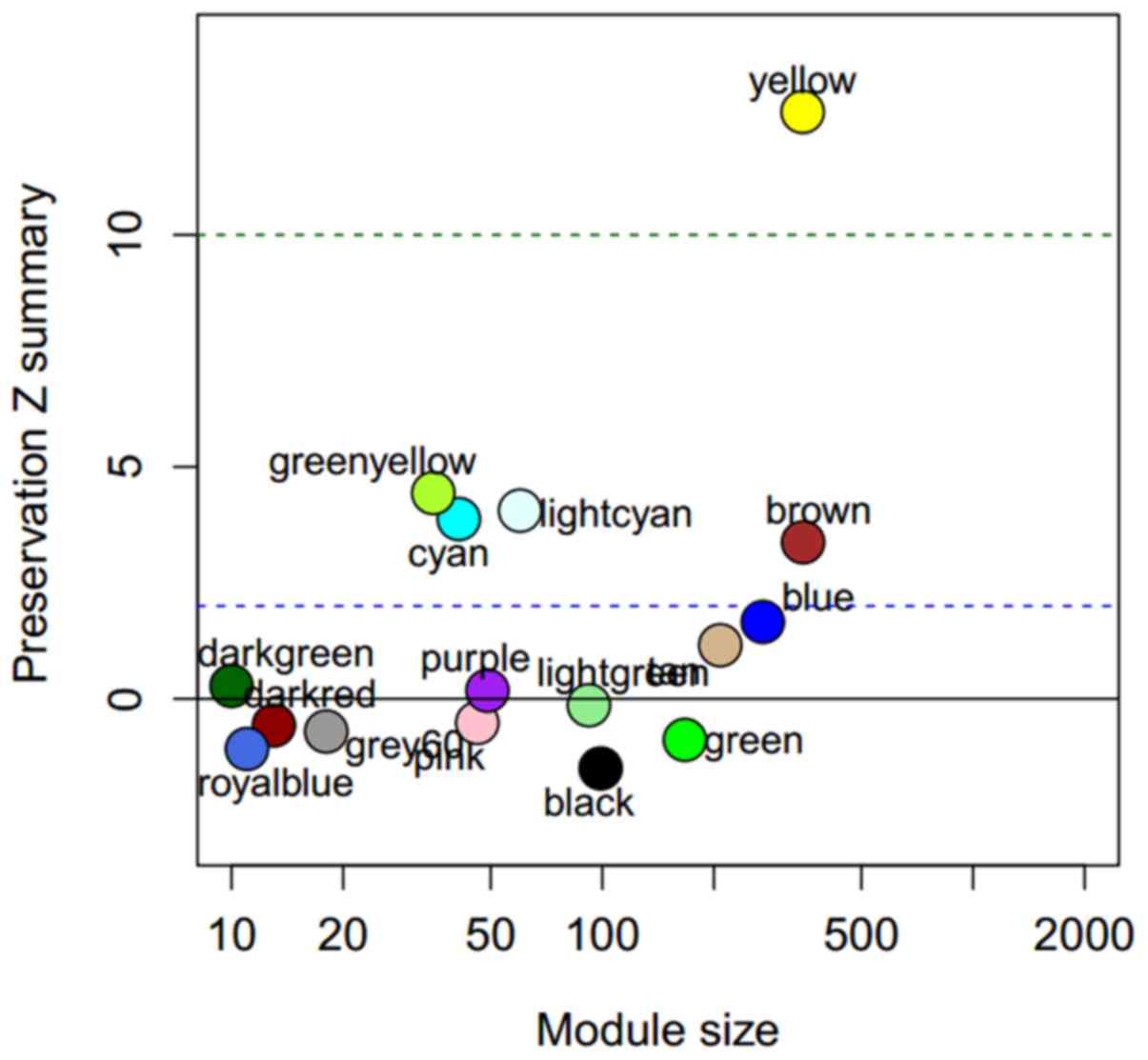

WGCNA ModulePreservation function was used to

evaluate the preservation of the 17 yeast modules in the human

cancer cell lines dataset, GSE36133 (Fig.

2). Five modules, yellow, green-yellow, light cyan, cyan and

brown were identified to be well preserved from high to low in

human cancer cell lines. They are associated with ncRNA processing,

mitochondrial translation, ubiquitin-dependent protein metabolism,

oxidative phosphorylation and regulation of translation.

Co-expression modules differentiate

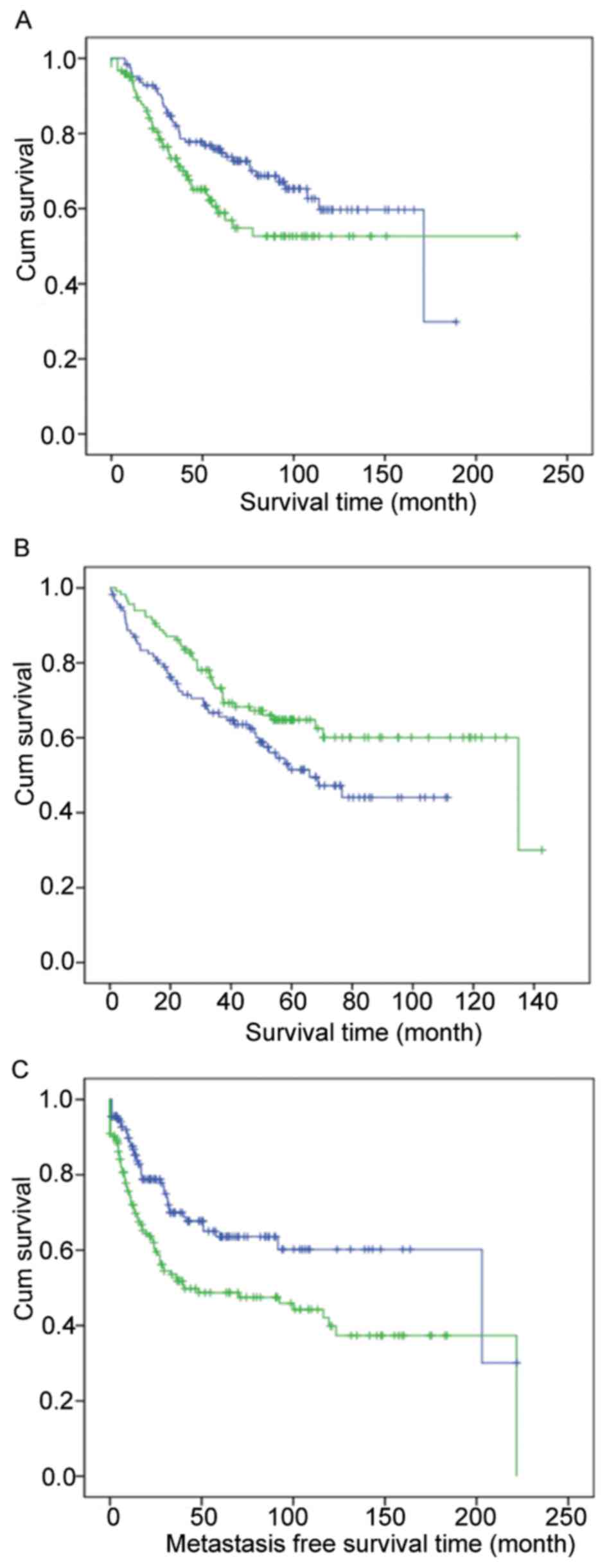

between patients with different survival times

To further validate the importance of these modules,

human breast cancer, colorectal cancer and sarcoma microarray

datasets were used to plot survival curves. For example, module

blue differentiates between breast cancer patients (Fig. 3A); module royal blue separates

colorectal cancer patients (Fig. 3B);

and module light green distinguishes sarcoma patients (Fig. 3C).

Discussion

WGCNA has been extensively applied to gene

co-expression network construction and analysis in various species.

For example, in human brain transcriptome analysis, Oldham et

al (10) identified the gene

co-expression corresponding to different brain regions. In plants,

Zhan et al (19) identified

cell-type specific gene co-expression modules, and observed

regulatory modules that were associated with endosperm cell

differentiation. WGCNA was previously used to depict functional

gene co-expression modules in mouse liver and human cancer cell

lines (20,21). In the present study, a gene network of

budding yeast was successfully constructed using WGCNA analysis.

All of the identified 17 modules were associated with specific

functional categories. As a single cell organism, the results are

easier to interpret. Therefore, WGCNA has an advantage over

differential gene expression analysis or ANOVA, which compare two

or more experimental groups. When there are many different

biological groups, it is more complicated to analyze these data.

WGCNA surmount these disadvantages, as it simplifies thousands of

genes into tens of functional modules. Finally, the method does not

require prior knowledge, so novel gene functions may be identified.

WGCNA has previously been used as a gene annotation method

(22).

The 17 identified modules represent different

aspects of budding yeast functions, including substance and energy

metabolism, cell proliferation and stimulus response (Table I). Module black contains genes

associated with heat response, which is an important trait of yeast

function (23). Recent studies

indicate that yeast has an adaptation for environmental stress,

such as high temperature (24).

Substance metabolism modules, include amino acid metabolism (dark

red), steroid metabolism (grey 60), organic acid metabolism

(purple) and sulfur metabolism (royal blue). Each module has a

distinct function, indicating the robustness of WGCNA.

Only 1,944 module genes were projected to human

homologous genes due to the limited number of yeast genes on

microarray. Thus, there is no definitive conclusion that modules

with a low preservation Z summary value are not preserved within

humans as a result of fewer genes in these modules (Fig. 2). However, the five preserved modules

identified in the present study are consistent with a previous

study that demonstrated that genes within these modules are

replaceable (3).

The significance of cancer cell line gene

co-expression modules in tumors has previously been reported

(21). In the current study, yeast

modules were observed in various human cancer datasets. For

example, certain modules differentiate between patients with long

and short survival times, indicating their importance from yeast to

humans. Those modules may be crucial in cancer biology and provide

information for human tumor research within yeast cells.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31270454

and 81502091), and of Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. LQ14H030001) and a Ningbo Natural Science

Foundation Grant (grant no. 2013A610232).

References

|

1

|

Botstein D, Chervitz SA and Cherry JM:

Yeast as a model organism. Science. 277:1259–1260. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jiang Q, Lin L and Wang T: A new model for

apoptosis research: Yeast. Prog Biochem Biophys. 35:3612008.

|

|

3

|

Kachroo AH, Laurent JM, Yellman CM, Meyer

AG, Wilke CO and Marcotte EM: Evolution. Systematic humanization of

yeast genes reveals conserved functions and genetic modularity.

Science. 348:921–925. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P,

Rudnev D, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Soboleva A, Tomashevsky M and

Edgar R: NCBI GEO: Mining tens of millions of expression profiles -

database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 35(Database):

D760–D765. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhu J, Zhang B, Smith EN, Drees B, Brem

RB, Kruglyak L, Bumgarner RE and Schadt EE: Integrating large-scale

functional genomic data to dissect the complexity of yeast

regulatory networks. Nat Genet. 40:854–861. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Guelzim N, Bottani S, Bourgine P and Képès

F: Topological and causal structure of the yeast transcriptional

regulatory network. Nat Genet. 31:60–63. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang B and Horvath S: A general framework

for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat Appl Genet

Mol Biol. 4:: 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P,

Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH,

Sherman PM, et al: NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data

sets − 10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(Database): D1005–D1010.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Miller JA, Horvath S and Geschwind DH:

Divergence of human and mouse brain transcriptome highlights

Alzheimer disease pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:12698–12703. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Oldham MC, Konopka G, Iwamoto K,

Langfelder P, Kato T, Horvath S and Geschwind DH: Functional

organization of the transcriptome in human brain. Nat Neurosci.

11:1271–1282. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Langfelder P and Horvath S: WGCNA: An R

package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC

Bioinformatics. 9:5592008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Huang W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID

bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 4:44–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Huang W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive

functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res.

37:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein

D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT,

et al: The Gene Ontology Consortium: Gene ontology: Tool for the

unification of biology. Nat Genet. 25:25–29. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y: Controlling

the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to

multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 57:289–300. 1995.

|

|

16

|

Langfelder P, Mischel PS and Horvath S:

When is hub gene selection better than standard meta-analysis? PLoS

One. 8:e615052013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gallina I, Colding C, Henriksen P, Beli P,

Nakamura K, Offman J, Mathiasen DP, Silva S, Hoffmann E, Groth A,

et al: Cmr1/WDR76 defines a nuclear genotoxic stress body linking

genome integrity and protein quality control. Nat Commun.

6:65332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Brar GA, Yassour M, Friedman N, Regev A,

Ingolia NT and Weissman JS: High-resolution view of the yeast

meiotic program revealed by ribosome profiling. Science.

335:552–557. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhan J, Thakare D, Ma C, Lloyd A, Nixon

NM, Arakaki AM, Burnett WJ, Logan KO, Wang D, Wang X, et al: RNA

sequencing of laser-capture microdissected compartments of the

maize kernel identifies regulatory modules associated with

endosperm cell differentiation. Plant Cell. 27:513–531. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu W and Ye H: Co-expression network

analysis identifies transcriptional modules in the mouse liver. Mol

Genet Genomics. 289:847–853. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu W, Li L and Li W: Gene co-expression

analysis identifies common modules related to prognosis and drug

resistance in cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 135:2795–2803. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Childs KL, Davidson RM and Buell CR: Gene

coexpression network analysis as a source of functional annotation

for rice genes. PLoS One. 6:e221962011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Novick P and Botstein D: Phenotypic

analysis of temperature-sensitive yeast actin mutants. Cell.

40:405–416. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li C, Qian W, Maclean CJ and Zhang J: The

fitness landscape of a tRNA gene. Science. 352:837–840. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|