1. Introduction

The co-occurrence of psychiatric disorders with

epilepsy has been long known and debated, as the relationship

between the two pathologies is complex and bidirectional (1,2). The

recent International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) guidelines

recommend early and continued screening, diagnosis and management

for all epilepsy-associated comorbidities in every patient with

epilepsy (3). However, the

prevalence of specific psychiatric comorbidities and correlation

with other clinical characteristics of epilepsy is still a matter

of debate, reflecting different methodologies in research studies

and clinical practice (4,5) and the changing diagnostic criteria for

both epilepsy (6) and psychiatric

disorders (7).

As far as we are aware, to date there are only a few

systematic reviews concerning psychiatric disorders associated with

epilepsy. We were not able to find recent reviews that address the

prevalence of most common psychiatric disorders in patients with

epilepsy. A systematic review published in 2016 addressed the risk

factors for depression in community treated epilepsy cases (based

on research results published between 2000 and 2013) and found that

sociodemographic variables (such as patient age and sex) played the

most important role (8). Another

older systematic review focused on psychosocial predictors of

depression and anxiety in epilepsy patients (9), while more recent reviews assessed

mainly screening and/or diagnostic methods for depression (10) or anxiety (11).

The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence

of specific interictal psychiatric disorders (depressive disorders,

anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders and personality disorders)

in patients with epilepsy and to compare this to the prevalence of

psychiatric disorders in the general population and to assess

possible associations between psychiatric disorders and other

sociodemographic or clinical characteristics of epilepsy

patients.

2. Methods

This review was performed according to the

recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic

Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (12).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search using two electronic

databases, namely MEDLINE and ScienceDirect was conducted in

February 2021. The databases were searched using a combination of

keywords: Depression, anxiety, affective disorder, psychotic

disorder, psychosis, personality, traits, epilepsy and seizures.

The search was limited to original research conducted in humans,

published in English language between January 2015 and February

2021. We applied additional filters for age (adults, older than 18

years).

Study inclusion criteria

Only controlled studies (randomized, cohort,

cross-sectional or case-control) were included in this analysis.

Studies were selected if conducted in patients diagnosed with

epilepsy/unprovoked single seizure, if the diagnostic methods used

for epilepsy and psychiatric disorders were reported, if the

characterization of both epilepsy and psychiatric comorbidities was

considered adequate, and if methodology (including statistical

analysis) was clearly described.

Study exclusion criteria

We excluded studies assessing only ictal/peri-ictal

psychiatric manifestations, treatment response or adverse effects.

We also excluded studies assessing psychogenic non-epileptic

seizures that did not report data of psychogenic non-epileptic

seizure patient groups separately, studies using for diagnosis

questionnaires administered online/remotely, studies that evaluated

psychiatric disorders only with self-administered screening tools

and studies that did not include comparative groups. Articles that

did not meet the primary inclusion criteria were also excluded

(e.g.: Case reports, case series, reviews, abstracts, book

chapters, patents, and conference papers) due to the lack of data

for assessment and comparison.

Data extraction

The data extracted from the eligible studies

included: Study setting (including year of publication, type of

research facility and country where the study was conducted), study

type, study objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, total

number of subjects included, mean/median age of patients included,

information on each comparative group (description, number of

patients, mean/median age of patients), information on epilepsy

(diagnosis criteria used, epilepsy syndrome, duration of epilepsy,

current seizure frequency), information on antiepileptic and

psychiatric drugs used by patients at the time of inclusion in the

study, information on psychiatric disorders observed (screening

tools used, confirmation tests applied, raters' qualification,

diagnosis code as per Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

IV/Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders-5th

edition (DSM-5, 2013), statistical methods, results (prevalence of

psychiatric disorders, statistically significant associations with

other clinical or paraclinical features of epilepsy) and

limitations of each study.

Study quality assessment

The risk of bias for the articles selected for this

review was assessed with the following quality checking

instruments: The RoB 2.0 tool for randomized trials (13), Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for

Cohort and Case-Control Studies, respectively (14), Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)

Critical Appraisal Checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies

(15) and Crombie's Items for

purely descriptive cross-sectional studies.

3. Results

Results of the search

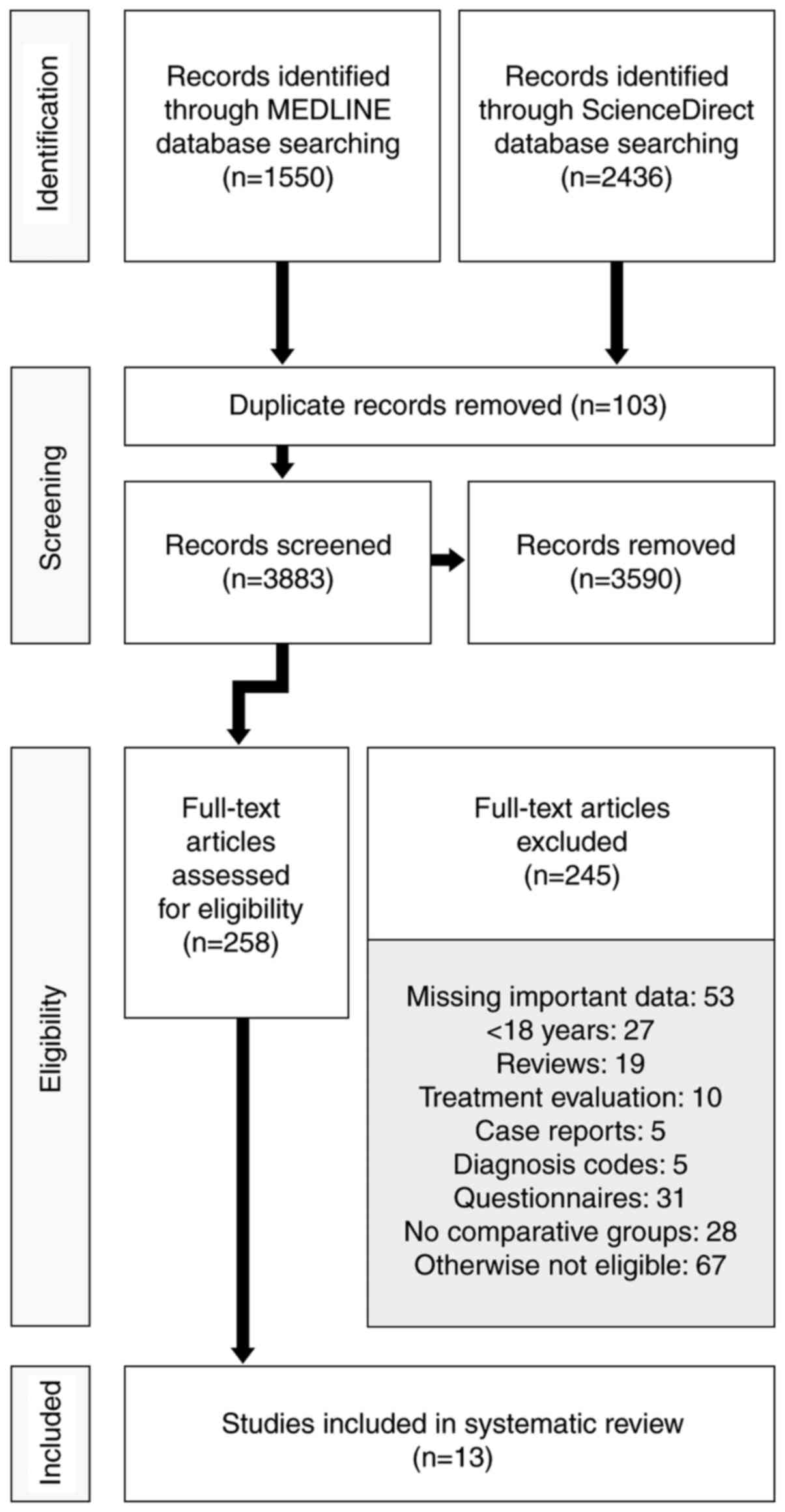

Using the search criteria described above we

identified 3,986 original articles (1,550 articles in MEDLINE

database and 2,436 articles in ScienceDirect database). We assessed

258 full articles for eligibility. Finally, we included in this

analysis 13 articles. The flowchart shown in Fig. 1 details this process.

Description of the studies. This analysis

includes 13 research studies, conducted in 7 countries (Australia,

one study; Brazil, three studies; China, two studies; Germany, two

studies; Japan, one study; Spain, one study; and USA, three

studies).

We included data obtained from one randomized controlled

trial (assessing depression and anxiety improvement in epilepsy

patients when multidisciplinary management was applied) because the

severity of the psychiatric disorders in the control group was

assessed after 12 months (16), two

cohort studies [one designed to detect depression disorders and

anxiety disorders in adult patients with childhood onset epilepsy

(17) and the other one analyzing

psychotic disorders in idiopathic focal epilepsy (18)], one case-control study that

evaluated specifically the psychiatric outcome in drug-resistant

epilepsy patients who underwent surgery vs. patients that were

considered non-eligible for the procedure (because baseline data on

psychiatric disorders diagnosed was solid and because the patients

in the control group were re-assessed by psychiatrist at 6 months,

thus providing information about the time evolution of psychiatric

disorders in people with epilepsy) (19), four studies with a cross sectional

design [first assessing interictal personality in patients with

juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and in patients with mesial

temporal lobe epilepsy related to hippocampal sclerosis (MTLE/HS)]

(20), second one analyzing

interictal dysphoric disorder and interictal personality in

drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (21), the third one evaluating depressive

symptoms and executive functions in patients with TLE (22) and the last one on white matter

changes in patients with TLE and depression (23). We selected for this analysis five

studies that assessed the relation between interictal dysphoric

disorder and other psychiatric disorders in patients with epilepsy

(24), the association between

childhood trauma and psychiatric comorbidities in epilepsy

(25), social adjustment

determinants in JME (26), possible

phenotypes of depression in epilepsy (27) and brainstem sonographic changes in

patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) (28). Importantly, we identified two

studies having the same first author (24,25)

and two studies performed by the same research team (22,23)

that had different research questions, but used a shared sample

population of epilepsy patients that was compared with a different

control group in the first case and with the same control group

(but fewer subjects) in the second case.

In total, 2,192 epilepsy patients were analyzed

(1,252 as sample cases and 940 in some of the control groups). Most

studies (nine) included patients investigated or followed up in

dedicated epilepsy units (of which at least six were tertiary

referral centres, as per authors' descriptions), while only four

studies included patients from general hospitals/practice. A

summary of the selected studies is shown in Table I.

| Table ISummary of the selected studies. |

Table I

Summary of the selected studies.

| Study

information | Sample | Control |

|---|

| Authors, year

(country) (ref.) | Design | Setting | Total size (N) | Subgroups | Age, years/months

mean (SD), median (IQR) [Range] | Description | Size (N) |

|---|

| Alonso et

al, 2019 (Brazil) (20) |

Cross-sectional | Outpatients,

Epilepsy centre | 200 | MTLE/HS 100 | 40.0 (11.46)

years | Healthy

volunteers | 100 |

| | | | | JME 100 | 30.9 (9.33)

years | | |

| Baldin et

al, 2015 (USA) (17) | Cohort | Outpatients | 257 | NA | 22.5 (3.5)

years | Siblings | 134 |

| | | | | | | External database

(randomly sampled by age at a ratio of 3:1) | 771 |

| de Araújo Filho

et al, 2017 (Brazil) (21) |

Cross-sectional | Outpatients,

Tertiary epilepsy centre | 95 | NA | 40.3 (14.6)

years | Healthy individuals

(community) | 50 |

| Galioto et

al, 2017 (USA) (22) | Cross-sectional,

prospective | Outpatients,

Neurology practice | 51 | TLE without

depression (TLE) 29 TLE with depression (TLE+DEP) 22 | 41.44 (12.18)

[22-63] years 41.32 (8.71) [27-60] years | Depression (DEP)

(hospital-based outpatient psychiatry clinics, community

advertisements) | 31 |

| Kavanaugh et

al, 2017 (USA) (23) |

Cross-sectional | Outpatients,

Neurology practice | 20 | TLE without

depression (TLE) 11 TLE with depression (TLE+DEP) 9 | 37.00 (11.79) years

46.56 (9.14) years | Depression (DEP)

(hospital-based outpatient psychiatry clinics, community

advertisements) | 11 |

| Konishi and

Kanemoto, 2020 (Japan) (18) | Cohort | Adult epilepsy

unit, Late onset PWE | 98 | NA | 66.2 (64.0-68.4)

years | Adult epilepsy

unit, early onset PWE | 775 |

| Labudda et

al, 2018 (Germany) (24) | Not specified | Epilepsy centre

(tertiary referral), PWE | 120 | NA | 35.42 (13.86)

years | Epilepsy centre

(tertiary referral), PNES | 28 |

| Labudda et

al, 2017 (Germany) (25) | Not specified | Epilepsy centre

(tertiary referral) | 120 | NA | 35.42 (13.86)

years | External (age-,

gender- and education-matched, random 1:1 selection) | 120 |

| Paiva et al,

2020 (Brazil) (26) | Not specified | Outpatients,

Epilepsy centre ambulatory (tertiary centre) | 112 | NA | 27.18 (±8.82)

years | Healthy controls

(patient acquaintances, hospital staff members, students) | 61 |

| Ramos-Perdigués

et al, 2016 (Spain) (19) | Prospective

case-control | Epilepsy centre for

presurgical evaluation, Surgical PWE | 85 | NA | 37.97 (12.307)

years | Epilepsy centre for

presurgical evaluation, Non-surgical PWE chronologically paired

with the immediately preceding surgical patient | 68 |

| Rayner et

al, 2016 (Australia) (27) | Not specified | Inpatients,

Comprehensive epilepsy programme | 91 | NA | 40.850 (12.602)

years | Healthy controls

(patient families, broader community) | 77 |

| Shen et al,

2020 (China) (28) | Not specified | Outpatients,

Department of neurology | 46 | NA | 31 (7.13)

years | Healthy subjects

(age- and gender-matched) | 45 |

| Zheng et al,

2019 (China) (16) | Randomized

controlled trial | Outpatients,

Hospital (tertiary referral centre) | 97 | NA | 28 (23.3, 38.8)

years | Outpatients,

hospital (tertiary referral centre), PWE | 97 |

The best represented epilepsy type was TLE (eight

studies included patients with this type of epilepsy), followed by

focal extratemporal lobe epilepsy (ETLE) and IGE (five studies

each). Two articles mentioned the inclusion of patients with

generalized seizures (without any reference to the actual epilepsy

diagnosis in these patients) and another three studies included

patients with other (not mentioned) types of epilepsy or presenting

unspecified or unclassifiable epilepsy/seizures.

Duration of epilepsy (mean/median) was less than 10

years in three studies (16,18,28),

between 10 and 20 years in six studies (18,20,24-27)

and longer than 20 years in three studies (20-22).

Three research articles did not contain clear information on

epilepsy duration.

Seizure frequency and antiepileptic drugs used for

treatment are difficult to summarize, because different reporting

measures were used. A summary of the epilepsy characteristics in

the selected studies is shown in Table

II.

| Table IISummary of the epilepsy

characteristics. |

Table II

Summary of the epilepsy

characteristics.

| | Epilepsy

characteristics |

|---|

| Study information

Authors, year (country) (ref.) | Diagnosis | Duration: Mean

(SD), median (IQR), [Range] years/months | Seizure

frequency | AED |

|---|

| Alonso et

al, 2019 (Brazil) (20) | Diagnosis criteria:

ILAE Post-surgical MTLE/HS, JME | 27.0 (11.29) years,

MTLE/HS 17.1 (9.50) years, JME | MTLE/HS Controlled

35 (35%); uncontrolled 65 (65%) JME Controlled 61 (61%);

uncontrolled 39 (39%) | Not specified |

| Baldin et

al, 2015 (USA) (17) | Diagnosis criteria:

Not specified Neurotypical cases of childhood-onset epilepsy

(normal clinical and imaging examination) recruited for other

research between 1993-1997, who attained the age of majority

Epilepsy type (n, %): BECTS+ 38 (14.8%); CAE 42 (16.3%); JA/ME 19

(7.4%); Other 158 (61.5%) | Not specified (at

least 15 years after diagnosis) | Not specified | Proportion in

5-year remission, n (%): On medication 15 (23.4); off medication

181 (94.3) |

| de Araújo Filho

et al, 2017 (Brazil) (21) | Diagnosis criteria:

Not specified Pharmacoresistant TLE-MTS | 25.3 (7.4)

years | Not specified | Most frequently

used AED, n (%): Carbamazepine: 58 (61.0); phenobarbital: 41

(43.1); clonazepam: 25 (26.3); Lamotrigine: 21 (22.1), clobazam: 18

(18.9) Number of AED used, n (%): One AED 5 (5.1); two AED: 79

(83.4); three AED 11 (11.5) |

| Galioto et

al, 2017 (USA) (22) | Diagnosis criteria:

Video-EEG monitoring TLE (HS/normal imaging) Lateralization, %: TLE

group right 10.0%; left 56.7%; bilateral 13.3% Lateralization, %:

TLE+DEP group right 20.0%; left 48%; bilateral 29.2% | 20.03 (13.10)

years, TLE 25.73 (15.43) years, TLE+DEP | No. of seizures in

the past month (mean, SD): 0.90 (0.94), TLE No. of seizures in the

past month (mean, SD): 1.00 (1.23), TLE+DEP | Polytherapy: 58.6%,

TLE Polytherapy: 59.1%, TLE+DEP |

| Kavanaugh et

al, 2017 (USA) (23) | Diagnosis criteria:

video-EEG monitoring, MRI Non-lesional TLE Lateralization n/N: Left

only-8/11 and 5/9; right only-0/11 and 1/9; bilateral-3/11 and

3/9 | Not specified Age

at seizure onset, years (mean): 15.64 (15.95) for TLE 13.22 (11.23)

for (TLE+DEP) | No. of seizure in

the past month (0, 1 or 2-n): 0-5, 1-3, 2-3 (TLE) No. of seizure in

the past month (0, 1 or 2-n): 0-7/, 1-1, 2-1 (TLE+DEP) | Current AE

treatment (n): 10, TLE Current AE treatment (n): 8, TLE+DEP |

| Konishi and

Kanemoto, 2020 (Japan) (18) | Diagnosis criteria:

Ictal symptoms, interictal EEG Idiopathic focal epilepsy TLE/ETLE:

Late onset PWE 32/66; control 227/548 | 13.6 (12.4-14.8)

years, early onset PWE 3.35 (2.25-4.45) years, late onset PWE | Not specified | Not specified |

| Labudda et

al, 2018 (Germany) (24) | Diagnosis criteria:

Not specified Epilepsy type, n: Focal (TLE 34, ETLE 66);

generalized 12; unclassifiable: 8 | 18.44 (14.35)

years | Seizure frequency,

% (n): Daily 21.7(26); weekly 34.2(41); monthly 21.7(26); yearly

16.7(20); none within the last year 5.8(7) | Mean number of AED

(mean, SD): 2.19 (0.98) |

| Labudda et

al, 2017 (Germany) (25) | Diagnosis criteria:

History, MRI, seizure semiology Epilepsy Type, n: Focal (TLE 34,

ETLE 23, multi-lobar 26, unknown 17); IGE 12, unclassifiable 8 | 18.44 (14.35)

years | Seizure frequency,

% (n): Daily 21.7(26); weekly 34.2(41); monthly 21.7(26); yearly

16.7(20); none within the last year 5.8(7) | Not specified |

| Paiva et al,

2020 (Brazil) (26) | Diagnosis:

Avignon's consensus JME | 12.72 (8.84)

years | GTC seizures %, n:

None 2.7% (3); good (<1 seizure per year) 74.1% (83); moderate

(1-4 seizures per year) 11.6% (13); or poor (>4 seizures per

year) 0.9% (1) Myoclonic seizures %, n: Good (<5 single seizures

or clusters per month, rare seizures, or occasional seizures)

69.64% (78); moderate (5-14 single seizures or clusters per month,

several seizures, or frequent seizures) 16.1% (18); poor (>15

single seizures or clusters per month or daily seizures) 3.6% (4)

Absence of seizures: None 59.82(67), good (<5 seizures per

month, rare seizures, or occasional seizures) 33.92% (38); moderate

(5-14 seizures per month, several seizures, or frequent seizures)

3.57% (4); poor (>15 seizures per month, frequent seizures, or

daily seizures) 2.67% (3) | Monotherapy, % (n):

84.8% (95); polytherapy, % (n): 14.3% (16) Drug response % (n):

Hard-to-control 17.9(20); easy to control: 69.59(78) |

| Ramos-Perdigués

et al, 2016 (Spain) (19) | Diagnosis Criteria:

Local presurgical protocol Pharmacoresistant epilepsy Idiopathic

aetiology: 66.3% Type of seizures, %: Tonic-clonic 17.6; Partial

complex 70.6 Lateralization: Right 57%; left 35.4%; bilateral 7.6%;

unknown 0 Locus: Temporal 65.4%; extratemporal 28.4%; unestablished

6.2% | Not specified Age

of epilepsy onset, 192.38 (172.08) months for all PWE | Baseline

seizures/month (mean, SD): 16.12 (20.99) | Baseline no. of AED

(mean, SD): Whole study population 2.24 (0.81) |

| Rayner et

al, 2016 (Australia) (27) | Diagnosis criteria:

Not specified Focal epilepsy Locus, %: TLE 76 (46% left hemisphere,

60% lesion-positive); ETLE 24 (32% left hemisphere, 73%

lesion-positive). | 19.150 (12.859)

[2-52] years | Monthly seizure

frequency, mean (SD) [Range] 22.680 (52.166) [1-400] Seizure

frequency (interval, n, %): ≤1/month 21 (23%); fortnightly

(2-7-3/month) 14 (15%); weekly (4-15/month) 36 (40%); more days

than not (≥16/month) 20 (22%) | Polytherapy, n (%):

70 (77%) No. of antiepileptic drugs, mean (SD) [range]: 2.24

(0.993) [1-6] |

| Shen et al,

2020 (China) (28) | Diagnosis criteria:

ILAE guidelines IGE-TCS | 7.70 (5.72)

years | Seizures/month,

mean (SD): 1.81 (2.13) | Not specified |

| Zheng et al,

2019 (China) (16) | Diagnosis criteria:

ILAE, 2001 Seizure type (baseline), n (%): Generalized [control 11

(12.0), intervention 14 (15.2)]; Focal [control 73 (79.3),

intervention 75 (81.5)]; unclassified [control 8 (8.7),

intervention 3 (3.3)] | 78 (36, 156)

months, control 84 (36, 168) months, intervention | Control group,

Baseline seizure frequency, n (%): Low 50 (54.3); high 42 (45.7)

Intervention group, Baseline seizure frequency, n (%): Low 41

(44.6); high 51 (55.4) | Control group,

baseline, n (%): Monotherapy 43 (46.7); polytherapy 49 (53.3)

Intervention group, baseline, n (%): Monotherapy 33 (35.9);

polytherapy 59 (64.1) Control group, baseline treatment regimen, n

(%): ≤2 times daily 78 (84.8); ≥3 times daily 14 (15.2)

Intervention group, baseline treatment regimen, n (%): ≤2 times

daily 83 (90.2); ≥3 times daily 9 (9.8) |

Psychiatric disorders

The self-assessment tools used for the screening or

quantification of psychiatric symptoms in the studies we analyzed

were: Neurobehavior Inventory (NBI), Revised Personality Inventory

(NEO-PI-R) (both tools assess personality traits), Interictal

Dysphoric Disorder Inventory (IDDI) (evaluates interictal dysphoric

disorder symptoms over the last 12 months), Neurological Depression

Disorder Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) (created to detect current

depression symptoms in epilepsy patients), Beck Depression

Inventory (BDI) and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (for

symptoms of depression), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

(HADS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Patient Health

Questionnaire-Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Items (PHQ-GAD-7) and

Beck Depression Inventory (BAI) (the last three tools rate current

anxiety symptoms).

Psychiatric disorders were confirmed according to

the DSM IV criteria in eight studies, using different structured or

semi-structured clinical interviews such as Structured Clinical

Interview for DSM IV Axis I disorders (SCID I) (two studies)

(20,27), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM

IV Axis II disorders (SCID II) (one study) (20), SCID for DSM-IV Clinician Version

(SCID CV) (one study) (19), MINI

International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) (two studies)

(22,23), Mini International Neuropsychiatric

Interview Plus (M.I.N.I.-Plus) (two studies) (24,25),

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (without further

details, one study) (28). DSM

IV-TR criteria were used for diagnosis in two studies: In one study

Diagnostic Interview Survey (DIS-IV) was applied by phone in

subjects and in one control group, while the Composite

International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was used for the second

control group (17); in the second

study SCID for Axis I and II was applied (26). Finally, DSM-5 criteria for diagnosis

were utilized in one study only (the method used for diagnosis was

standard psychiatric assessment, without a formal standardized

interview) (21). Diagnosis

criteria employed by the psychiatrist who confirmed the psychiatric

diagnoses were not specified at all in two studies (16,18).

The professional confirming the psychiatric diagnosis was a

psychiatrist in two studies (19,20)

and psychologist in two studies (22,23).

The remaining seven articles did not clearly specify the

qualifications of the person(s) who conducted the psychiatric

interview (17,21,24-28).

The prevalence of any psychiatric disorder was high

for all epilepsy types: 43 and 51%, respectively, in two

populations with JME (20,26), 33% in patients with MTLE/HS that

underwent surgery (20), 43.1% in

patients with pharmacoresistant TLE-MTS (21) and 43.3% in a sample of patients with

epilepsy from a tertiary referral centre (24,25). A

summary of the psychiatric disorders characteristics is shown in

Table III.

| Table IIISummary of the characteristics of the

psychiatric disorders. |

Table III

Summary of the characteristics of the

psychiatric disorders.

| | Psychiatric

disorders |

|---|

| Study designation

Authors, year (country) (ref.) |

Screening/Self-assessment tests | Confirmation of

diagnosis | DSM version | Training and number

of professionals confirming the diagnosis | Lifetime

current | Diagnosis | Prevalence of

diagnosis (%, n) | Statistical

significance |

|---|

| Alonso et

al, 2019 (Brazil) (20) | NBI | SCID-I | DSM-IV | Psychiatrist

(2) | Not specified | Any psychiatric

diagnosis | | Not reported |

| | NEO-PI-R | SCID-II | | | | JME | 43% | |

| | | | | | | MTLE-HS | 33% | |

| | | | | | | Depression

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | JME | 16% | |

| | | | | | | MTLE-HS | 26% | |

| | | | | | | Anxiety

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | JME | 19% | |

| | | | | | | MTLE-HS | 7% | |

| | | | | | | Personality

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | JME | 8% | |

| | | | | | | MTLE-HS | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Psychiatric

treatment in the past | | |

| | | | | | | Controls | 6% | |

| Baldin et

al, 2015 (USA) (17) | Not applied | DIS-IV (cases,

siblings) | DSM-IV-TR | Two interviewers

with one week DIS training, by phone | NA | DIS Lifetime mood

disorder (major depressive episode, major depressive disorder

single episode, major depressive disorder recurrent, depressive

episode with melancholic features, bipolar I disorder, bipolar II

disorder, bipolar I disorder single manic episode, dysthymic

disorder, manic episode, mixed episode, hypomanic episode) | | |

| | | CIDI (external

controls) | DSM-IV-TR | Not specified | | Adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy | 20.60% | NS |

| | | DISC-IV | DSM-IV (American

Psychiatric Association) | Two interviewers

with one week DIS training, by phone | | Siblings | 23.10% | |

| | | | | | | External

controls | 23.90% | |

| | | | | | | DIS Lifetime

anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with

and without agoraphobia, agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic

disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia) | | |

| | | | | | | Adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy | 15.60% | NS |

| | | | | | | Siblings | 20.20% | |

| | | | | | | External

controls | 27.80% | Unmatched adjusted

OR 0.5 (0.3-0.7), P=0.0003 |

| | | | | | | DIS Current mood

disorder (previous year: Major depressive episode, dysthymic

disorder, manic episode, hypomanic episode) | | |

| | | | | | | Adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy | 12.80% | NS |

| | | | | | | Siblings | 11.90% | |

| | | | | | | External

controls | 13.50% | |

| | | | | | | DIS Current anxiety

disorder (previous year: Anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or

without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, social

phobia) | | |

| | | | | | | Adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy | 6.30% | NS |

| | | | | | | Siblings | 8.40% | |

| | | | | | | External

controls | 14.50% | Unmatched adjusted

OR 0.4 (0.2-0.7),P=0.002 |

| | | | | | | DISC Suicide

ideation | | |

| | | | | | | Adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy | 16% | NS |

| | | | | | | Siblings | 13.40% | |

| | | | | | | External

controls | 13.10% | |

| | | | | | | DISC Suicide

attempt | | |

| | | | | | | Adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy | 5.10% | NS |

| | | | | | | Siblings | 2.20% | |

| | | | | | | External

controls | 3.60% | |

| de Araújo Filho

et al, 2017 (Brazil) (21) | IDDI | Standard

psychiatric assessment | DSM-5 | Not specified | Not specified | Axis I psychiatric

disorders | | |

| | NBI | | | | | | | |

| | | ILAE Diagnosis

Criteria for Interictal Personality | | Not specified | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 43.1% (41) | | |

| | | ILAE Diagnosis

Criteria for Interictal Dysphoric Disorder | Not specified | Major depressive

disorder | | | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 21 | P=0.001 |

| | | | | | | Controls | 6 | |

| | | | | | | Generalized anxiety

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 15 | P=0.001 |

| | | | | | | Controls | 5 | |

| | | | | | | Conversion

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 9 | P=0.001 |

| | | | | | | Controls | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Interictal

psychosis | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 5 | NS |

| | | | | | | Controls | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Interictal

dysphoric disorder (IDDI) | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 18.4% (18) | P=0.001 |

| | | | | | | Controls | 8% (4) | |

| | | | | | | Interictal

personality (NBI) | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

TLE-MTS | 37.9% (36) | P=0.001 |

| | | | | | | Controls | 8% (4) | |

| Galioto et

al, 2017 (USA) (22) | Not applied | M.I.N.I. | DSM-IV | Neuropsychologist

(1, blinded to other procedures) | Not specified | Major depressive

disorder | Not specified | Not assessed |

| | | HAM-D | | Neuropsychologist

(1, blinded to other procedures) | Not specified | Dysthymic

disorder | Not specified | |

| | | | | | Current | Current major

depressive episode | | |

| | | | | | | TLE (HS/normal

imaging) with depression | 18.20% | |

| | | | | | | Depression | 22.60% | |

| Kavanaugh et

al, 2017 (USA) (23) | Not applied | M.I.N.I. | DSM-IV | Neuropsychologist

(1, blinded to other procedures) | Not specified | Major depressive

disorder | Not specified | Not assessed |

| | | HAM-D | Neuropsychologist

(1, blinded to other procedures) | Not specified | Dysthymic

disorder | | | |

| Konishi and

Kanemoto, 2020 (Japan) (18) | Not applied | Interview: Clinical

criteria for psychosis (no differentiation between

ictal/interictal) | Not specified | Psychiatrist,

number not specified | Lifetime | History of

psychosis (first visit) | | |

| | | | | | | PWE screened

(2568) | 2.5% (54) | NA |

| | | | | | | Focal idiopathic

epilepsy | 4.3% (38) | |

| | | | | | | Early onset focal

idiopathic epilepsy | 38.77% (38) | P=0.016 |

| | | | | | | Late onset focal

idiopathic epilepsy | 0 | |

| | | | | | | TLE | 8.50% | NA |

| | | | | | | Type of

psychosis | | |

| | | | | | | Interictal | 32 | |

| | | | | | | Predominantly

postictal | 6 | |

| | | | | | | Both, interictal

and postictal | 2 | |

| Labudda et

al, 2018 (Germany) (24) | IDDI | M.I.N.I.-Plus | DSM-IV | The interviews were

carried out by 2 authors (affiliated to a Psychology Department),

videotaped and re-evaluated by at least 1/2 further interviewers

experienced in this procedure when diagnostic uncertainty | Current | At least 1 current

axis I psychiatric disorder | | |

| | NDDI-E | | | | | | | |

| | STAI | | | | | | | |

| | SCL-90-R | | | | | | | |

| | | PDS | | The interviews were

carried out by 2 authors (affiliated to a Psychology Department),

videotaped and re-evaluated by at least 1/2 further interviewers

experienced in this procedure when diagnostic uncertainty | | PWE | 43.3% (52) | (χ2

>5.47, |

| | | | | | | PNES | 67.9 % (19) | P<0.022) |

| | | | | | | At least 1

affective disorder | | NS |

| | | | | | | PWE | 21.7% (26) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 28.6% (8) | |

| | | | | | | Major depressive

episode | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 5% (6) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 17.9% (5) | |

| | | | | | | Recurrent

depressive disorder (with recent episode) | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 9.2% (11) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 10.7% (3) | |

| | | | | | | Dysthymia | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 7.5% (9) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Bipolar

disorder | 0 | |

| | | | | | | At least 1 anxiety

disorder | | (χ2

>5.47, |

| | | | | | | PWE | 30.8% (37) | P<0.022) |

| | | | | | | PNES | 64.3% (18) | |

| | | | | | | Social phobia | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 9.2% (11) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 10.7% (3) | |

| | | | | | | Specific

phobia | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 2.5% (3) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 7.1% (2) | |

| | | | | | | Panic disorder

alone | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 0.8% (1) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Agoraphobia

alone | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 5% (6) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 14.3% (4) | |

| | | | | | | Panic disorder with

agoraphobia | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 3.3% (4) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 21.4% (6) | |

| | | | | | | Generalized anxiety

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 4.2% (5) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 10.7% (3) | |

| | | | | | |

Obsessive-compulsive disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 2.5% (3) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 3.6% (1) | |

| | | | | | | Adjustment

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 5.8% (8) | |

| | | | | | | PNES | 3.6% (1) | |

| | | | | | | Substance

dependence | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 1.7% (2) | Not reported |

| | | | | | | PNES | 3.6% (1) | |

| | | | | | | Eating

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 0.8% (1) | Not reported |

| | | | | | | PNES | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Psychotic

episode | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 3.3% (4) | Not reported |

| | | | | | | PNES | 0 | |

| | | | | | | Posttraumatic

stress disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 9.2% (11) | Not reported |

| | | | | | | PNES | 32.1% (9) | |

| | | | | | | Interictal

dysphoric disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 35% (42) | NS |

| | | | | | | PNES | 39% (11) | |

| | | | | | | Interictal

dysphoric disorder + other current psychiatric disorder | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 27.5% (33) | Not assessed |

| Labudda et

al, 2017 (Germany) (25) | CTQ | M.I.N.I.-Plus

(Mini, version 5.0.0) | DSM IV | Interviews were

carried out by 4 authors with experience and training in clinical

interviews (affiliated to a Psychology department), videotaped and

re-evaluated by at least 1 further interviewer experienced in this

procedure when diagnostic uncertainty | Current | At least 1

diagnosis | | |

| | FBS | | | | | | | |

| | | PDS | | Interviews were

carried out by 4 authors with experience and training in clinical

interviews (affiliated to a Psychology department), videotaped and

re-evaluated by at least 1 further interviewer experienced in this

procedure when diagnostic uncertainty | | PWE | 43.3% (52) | Not assessed |

| | | The Epilepsy

Addendum for Psychiatric Assessment | Interviews were

carried out by 4 authors with experience and training in clinical

interviews (affiliated to a Psychology department), videotaped and

re-evaluated by at least 1 further interviewer experienced in this

procedure when diagnostic uncertainty | | At least 1

affective disorder | | | |

| | | | | | | PWE | 21.7% (26) | Not assessed |

| | | | | | | At least 1 anxiety

disorder | 30.8% (37) | |

| | | | | | | PWE | | Not assessed |

| Paiva et al,

2020 (Brazil) (26) | STAI | SCID for Axis I and

II (89.3% of PWE) | DSM-IV-TR | Not specified (all

authors affiliated to a Psychiatry department) | Not specified | Psychiatric

disorders | | Not assessed |

| | SAS | | | | | ME | 51% | |

| | | | | | | Anxiety

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | ME | 31% | |

| | | | | | | Personality

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | JME | 11% | |

| | | | | | | Depressive

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | JME | 9% | |

| | | | | | | Overlap | | |

| | | | | | | ME | 8% (3 patients with

an anxiety disorder and substance abuse; 2 patients with depressive

disorder and substance abuse; and 3 patients with depressive

disorder and personality disorder) | |

| Ramos-Perdigués

et al, 2016 (Spain) (19) | HADS | SCID-CV | DSM-IV | Psychiatrist

(1) | Not specified | Baseline affective

disorder (major depressive episodes, recurrent depression,

dysthymic disorder, affective disorder due to a medical condition

or substance disorder, adjustment disorder and bipolar

disorder) | | |

| | SCL-90-R | | | | | | | |

| | | | | ILAE Classification

Proposal for Interictal Dysphoric Disorder and Interictal

Personality | | Pharmacoresistant

epilepsy | 22% | NS |

| | | | | | | Surgical group | 23.20% | |

| | | | | | | Non-surgical

group | 20.60% | |

| | | | | | | Baseline psychotic

disorder (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and other

psychosis) | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

epilepsy | 4% | NS |

| | | | | | | Surgical group | 4.90% | |

| | | | | | | Non-surgical

group | 2.90% | |

| | | | | | | Baseline anxiety

disorder (panic disorder, phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder,

posttraumatic stress disorder, and other anxiety disorders) | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

epilepsy | 15.30% | NS |

| | | | | | | Surgical group | 15.90% | |

| | | | | | | Non-surgical

group | 14.70% | |

| | | | | | | Baseline eating

disorder | 0 | NA |

| | | | | | | Baseline drug

use | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

epilepsy | 2% | NS |

| | | | | | | Surgical group | 1.20% | |

| | | | | | | Non-surgical

group | 2.90% | |

| | | | | | | Baseline conduct

disorder | 0 | NA |

| | | | | | | Interictal

dysphoric disorder | | |

| | | | | | | Pharmacoresistant

epilepsy | 27.10% | NS |

| | | | | | | Surgical group | 22.80% | |

| | | | | | | Non-surgical

group | 25% | |

| | | | | | | Interictal

psychotic disorder | 0 | NS |

| Rayner et

al, 2016 (Australia) (27) | NDDI- E | SCID-I | DSM-IV | Not specified | Lifetime | Lifetime history of

depressive disorder | | |

| | PHQ-GAD-7 | | | | | | | |

| | ESI-55 | | | | | Focal epilepsy | 40% (36) | Not assessed |

| | FACES-IV | | | | | | | |

| | AMI | | | | Current | Current major

depressive episode or Depressive disorder not otherwise

specified | | |

| | | | | | | Focal epilepsy | 23% (21) | Not assessed |

| | | | | | | Current major

depressive disorder | | |

| | | | | | | Focal epilepsy | 10 | Not assessed |

| | | | | | | Current dysthymic

disorder | | |

| | | | | | | Focal epilepsy | 4 | Not assessed |

| | | | | | | Current minor

depressive disorder | | |

| | | | | | | Focal epilepsy | 7 | Not assessed |

| Shen et al,

2020 (China) (28) | NDDI-E | SCID | DSM-IV | Not specified | Not specified | Depression | | |

| | BDI-II | | | | | I GE-TCS | 34.78% (16) | NA |

| | | | | | | Without

depression | | |

| | | | | | | IGE-TCS | 65.21% (30) | NA |

| Zheng et al,

2019 (China) (16) | BDI | Not Specified | Not specified | Psychiatrist | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| | BAI | | | | | | | |

Mood/affective disorders

Prevalence of current mood disorders (major

depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, manic episode, hypomanic

episode during the previous year) was 12.8% in adults with

neurotypical childhood onset epilepsy (comparison with both control

groups-siblings and external controls-was not statistically

significant) (17). Current major

depressive episode was present in 18.2% of the patients from a

population with TLE and depression (22). In a general population of epilepsy

patients from a third referral centre, 21.7% were diagnosed with at

least one affective disorder (24,25)

(5% presented major depressive episode, 9.2% recurrent depressive

disorder and 7.5% dysthymia, while none of these patients was

diagnosed with bipolar disorder), without statistical significance

when prevalence was compared with psychogenic non-epileptic

seizures patients in the control group (24). In focal epilepsy (mostly

pharmacoresistant) current major depressive episode or other

depressive disorders (major depressive disorder, minor depressive

disorder, dysthymia) had a prevalence of 23% (27).

Lifetime mood disorders (major depressive episode,

major depressive disorder single episode, major depressive disorder

recurrent, depressive episode with melancholic features, bipolar I

disorder, bipolar II disorder, bipolar I disorder single manic

episode, dysthymic disorder, manic episode, mixed episode,

hypomanic episode) had a prevalence of 20.6% in adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy, statistically not significant when

compared with the prevalence of lifetime mood disorders in both

control groups (sibling and external controls) (17). The prevalence of lifetime history of

depression in focal epilepsy (mostly pharmacoresistant) was 40%

(27).

Prevalence of depressive disorder (not specified if

lifetime/current) was 16 and 9%, respectively, in two populations

of patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (20,26)

and 26% in patients with MTLE/HS, late post-surgically (20). Prevalence of major depressive

disorder was 22.1% in patients with pharmacoresistant TLE-MTS,

significantly higher than in healthy individuals from the community

(21). Prevalence of affective

disorders (including major depressive episodes, recurrent

depression, dysthymic disorder, affective disorder due to a medical

condition or substance disorder, adjustment disorder and bipolar

disorder, but not specified if lifetime/current) was 22% in

pharmacoresistant epilepsy patients assessed for epilepsy surgery

(19). Finally, the incidence of

depression (no further details regarding the exact DSM IV diagnosis

or if current/lifetime) was 34.78% in patients with idiopathic

generalized epilepsy (with tonic-clonic seizures) (IGE TCS)

(28).

Suicidal risk and suicidal attempt, evaluated by

Diagnostic Interview Survey for Children (DISC-IV), in adults with

childhood-onset epilepsy had a prevalence of 16 and 5.1%,

respectively, and statistical analysis (including comparison with

siblings and external controls) showed no relation between suicidal

thoughts and behaviors and epilepsy (17).

In a study that examined the relationship between

white matter integrity [assessed by Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI)]

and depression in a small group of patients with TLE and depression

(major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder, as per DSM-IV

criteria) (23), the severity of

the depression [The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(HAM-D) score] was significantly and negatively correlated with the

matter integrity in non-fronto-temporo-limbic areas

[non-fronto-temporo-limbic fractional anisotropy (non-FTL-FA)

composite score, P<0.05] and showed a similar trend for

fronto-temporo-limbic areas (P=0.06), while in the control group

(patients with depression, without epilepsy) the correlation was

not statistically significant.

When the contribution of depression (major

depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder) to executive functioning

was assessed in TLE patients, it was observed that epilepsy

patients with depression (not specified if current or lifetime)

performed worse than epilepsy patients without depression in verbal

fluency test for category switching (P=0.04) (22).

One study investigated two possible symptom-based

phenotypes of depression (named by authors cognitive and somatic,

respectively) in focal epilepsy (27). For the cognitive depression group,

the authors described higher rates of parasuicidal or suicidal

thoughts, feelings of worthlessness, delusions of guilt, dysphoric

mood than in the somatic depression (but the intergroup comparison

showed no statistical significance for these DSM-IV symptoms). When

these patients were compared with non-depressed epilepsy patients;

they were more likely to have a left-lateralized seizure focus

(P=0.034), but there were no other differences in any other

epileptological variables or in anticonvulsant or psychotropic

pharmacotherapy. Compared with healthy subjects, patients with

cognitive depression exhibited significantly reduced semantic and

episodic autobiographic memory across all life periods (including

significantly worse overall semantic and episodic recollection) and

significantly reduced delayed recall across auditory-verbal

(P=0.032) and visual domains (P=0.002) on the Wechsler Memory

Scale-IV (WMS-IV) subtests, in the context of intact immediate

learning (P>0.050). Instead, somatic depression patients

presented significant higher rates of somatic symptoms (appetite

changes, sleep changes) and anhedonia (for all P<0.01) and there

were no differences when compared with epilepsy patients without

depression in any other epileptological variables or in

anticonvulsant or psychotropic pharmacotherapy. Somatic depression

patients had more seizures and greater variability in seizure

frequency than the cognitive phenotype (monthly average seizure

frequency 17.5 and 4, respectively) and performed worse than

healthy subjects in childhood episodic, early adulthood semantic,

overall episodic, and delayed visual recall, but these inter-group

differences were not statistically significant. Odds ratio (OR)

analysis suggested that, compared with patients with somatic

depression, depressed patients with the cognitive phenotype were

more likely to have semantic autobiographic memory deficit (i.e.,

Autobiographical Memory Interview (AMI) subscale score b 50; 95%

CI=0.162-81.705), episodic autobiographic memory deficit (i.e., AMI

subscale score b 16; 95% CI=0.316-16.512) and impaired immediate

verbal learning (i.e., WMS-IV score ≤8; 95%). Psychosocial and

demographic features of the two phenotypes of depression [age,

relationship status, level of depressive symptoms (NDDI-E), level

of family satisfaction (The Family Adaptability and Cohesion

Scale-Fourth edition (FACES-IV), symptoms of anxiety (PHQ-GAD-7),

quality of life (The Epilepsy Surgery Inventory-55 Items (ESI-55)

or psychotropic medications] were not significantly different

between groups (P>0.05 for all comparisons) (27).

In a study assessing brainstem echogenicity in

depressed patients with IGE-TCS there was no significant difference

in third ventricle width between epilepsy patients with and without

depression (P=0.293), but more epilepsy patients with depression

exhibited hypoechogenic brainstem raphe (P=0.000) (28).

Interictal dysphoric disorder is a psychiatric

disorder assumed to be specific for epilepsy patients. Prevalence

of interictal dysphoric disorder was 35% in a general population of

epilepsy patients (associated in 27% of the total cases with mood

disorder, anxiety disorder, both mood and anxiety disorder,

substance abuse), 39% in a population with psychogenic

non-epileptic seizure (both epilepsy patients and psychogenic

non-epileptic seizure patients were assessed in a tertiary centre

and comparison between the two groups did not show a statistical

difference) (24), 18.4% in

resistant TLE-MTS (significantly higher than in healthy subjects

from the control group) (21) and

27.1% in a group of patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy (also

significantly higher than in the control group) (19). In a study of prevalence of

interictal dysphoric disorder in epilepsy patients it was

demonstrated that epilepsy patients with interictal dysphoric

disorder had more frequently than epilepsy patients without

interictal dysphoric disorder at least one current psychiatric

disorder (χ2=32.68, P<0.001), at least one current

affective disorder [major depressive episode, recurrent depressive

disorder, dysthymia (χ2=25.64, P<0.001)] and at least

one current anxiety disorder [social phobia, specific phobia, panic

disorder alone, agoraphobia alone, panic disorder with agoraphobia,

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder,

adjustment disorder (χ2=17.35, P<0.001)], and that

66% of epilepsy patients without a current psychiatric comorbidity

had a diagnosis of a past psychiatric disorder (recurrent

depressive disorder currently remitted and substance addiction)

(24). Also, epilepsy patients with

interictal dysphoric disorder and other psychiatric disorders had

similar symptoms with epilepsy patients with interictal dysphoric

disorder alone (euphoria, Fisher's exact test: P=1.0; irritability,

Fisher's exact test: P=0.698) (24). In patients with drug-resistant

epilepsy assessed for surgery, the presence of interictal dysphoric

disorder was correlated with epilepsy location: 33.3% of patients

had no loci established, 8.3% had extratemporal loci, and 58.3% had

temporal loci (P=0.002) (19).

Analysis of the diagnostic superposition between interictal

dysphoric disorder and DSM Axis I psychiatric disorders in patients

with TLE-MTS showed that none of the interictal dysphoric disorder

patients and none of the healthy subjects in the control group had

a DSM Axis I psychiatric disorder (21). Multivariate logistic regression

analysis revealed that the significant risk factors for interictal

dysphoric disorder in patients with pharmacoresistant TLE-MTS were

the presence of left-sided mesial temporal sclerosis (OR=3.22;

P=0.008), previous psychiatric treatment (OR=4.29; P=0.007) and the

use of more than one antiepileptic drug (OR=2.73; P=0.02) (21).

Anxiety disorders

Current anxiety disorders (anxiety disorder, panic

disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic

disorder, social phobia during the previous year) had a prevalence

of 6.3% among adult patients with childhood onset epilepsy. In this

case the prevalence of current anxiety disorders was not

statistically significant different between cases and siblings, but

when cases were compared with external controls, current anxiety

disorders were associated with a significantly decreased odds of

epilepsy (17). At least one

anxiety disorder was present in 30.8% of a sample of epilepsy

patients from a tertiary referral centre (social phobia in 9.2%,

specific phobia in 2.5%, panic disorder alone in 0.8%, agoraphobia

alone in 5%, panic disorder with agoraphobia in 3.3%, GAD in 4.2%

and adjustment disorder in 5.8%). The overall comparison with a

group of patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures showed

that for all disorders mentioned above (except adjustment

disorder), the prevalence was higher in the psychogenic

non-epileptic seizures group (24).

Lifetime anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety

disorder, panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, agoraphobia,

agoraphobia without panic disorder, social phobia, and specific

phobia) were present in 15.6% of adults with childhood onset

epilepsy. As in the case of current anxiety disorders, in this

study the prevalence of lifetime anxiety disorders was not

significantly different between cases and siblings, but was

significantly higher in the external controls than in epilepsy

patients (17).

Where lifetime or current was not specified, anxiety

disorder was present in 19 and 31%, respectively in two populations

of patients with JME (20, 26), in 7% of the post-surgical patients

with MTLE/HS (20) and in 15.3% of

patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy (diagnosed with panic

disorder, phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic

stress disorder, and other anxiety disorders) (19). Prevalence of generalized anxiety

disorder in pharmacoresistant TLE-MTS was 15.78% (significantly

higher than in healthy controls, P=0.001) (21).

In patients with JME, the presence of anxiety

disorder (not specified if current or lifetime) was moderately

correlated with a higher frequency of generalized tonico-clonic

seizures (GTCS) (τ=-0.320; P=0.008) and with worse familiar

relationship adjustment [Social Adjustment Scale (SAS) family

score, (τ=0.241; P=0.025)]. There was no other significant

correlation between the presence of anxiety disorder and other

social adjustment domains (SAS scores for work, leisure/social,

economic or total) (26).

Psychotic disorders

Only four studies reported the prevalence of

psychotic disorders in epilepsy patients. The prevalence of

lifetime psychosis (ictal or interictal), as reported historically

by patients during their first psychiatric assessment in epilepsy

centre was 2.5% in a general epilepsy patient population (2,568

epilepsy patients screened), 4.3% in focal idiopathic epilepsy and

even higher in TLE (8.5%). In this specific study, interictal

psychosis was retrospectively diagnosed in 4.12% of the focal

idiopathic epilepsy cases (18).

When DSM criteria were used, 3.3% of the epilepsy

patients from a tertiary epilepsy centre were diagnosed with

current psychotic episode (24).

Psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other

psychosis) had a prevalence of 4% in pharmacoresistant epilepsy

(19) and interictal psychosis had

a prevalence of 5% in pharmacoresistant TLE-MTS (not significant in

comparison with controls) (21).

Interictal psychotic disorder (as per ILAE proposed criteria) was

not diagnosed in any of the patients with drug resistant epilepsy

assessed for surgery eligibility (19).

The only study that specifically investigated the

presence of psychosis in focal epilepsy without central nervous

system diseases found a significant difference between the

prevalence of psychosis (predominantly interictal, but also

peri-ictal) between patients with late-onset epilepsy (at >49

years) and patients with early onset epilepsy (at <49 years),

basically with no cases in the old-onset group (P=0.016).

Significant determinants associated with psychosis in this study

were duration of illness (P=0.000001) and presence of temporal lobe

epilepsy (P=0.000343), while sex and age at examination were not

contributory to psychosis (18).

Personality disorders

Personality disorders (assessed using DSM criteria)

were present in 8% and respectively 11% of the JME patients

assessed in two studies (20,26)

and in none of the post-surgical MTLE/HS cases assessed in one

study (20).

A study that specifically investigated personality

profile in JME and post-surgical MTLE/HS patients using NBI and

NEO-PI-R found a positive correlation between the neuroticism

domain of NEO-PI-R and psychiatric symptoms in both MTLE/HS

(r=0.201; P=0.003) and JME (r=0.145; P=0.010) groups. Also,

post-surgical MTLE-HS patients with psychiatric diagnoses

(depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and personality

disorders), had higher total NBI scores than those with no

psychiatric symptoms (P<0.001) and JME patients with psychiatric

diagnoses and uncontrolled GTCS had higher total NBI scores than

those with no psychiatric symptoms/controlled GTCS (P=0.001 and

P=0.032, respectively). In patients with psychiatric symptoms,

13/20 NBI traits (65%) were higher in the MTLE/HS group than in the

JME group (9/20, 45%) (P=0.05) (20).

Interictal personality, a behavioral condition that

could be associated with epilepsy (assessed with NBI) had a

prevalence of 37.9% in pharmacoresistant TLE (significantly higher

than in controls) (21). When

analysis of the diagnostic superposition between interictal

personality and DSM Axis I psychiatric disorders was conducted, 15

(41.6%) of the epilepsy patients with interictal personality had a

DSM Axis I psychiatric disorder (major depressive disorder 66.6%,

interictal psychosis 18.7%, conversion disorder 13.4%), while none

of the subjects in the control group with DSM Axis I psychiatric

disorders demonstrated superposition with interictal personality.

Multivariate logistic regression models showed that significant

risk factors for interictal personality are the presence of

bilateral mesial temporal sclerosis (OR=3.27; P=0.008), longer

disease duration (OR=3.39; P=0.006) and the presence of major

depressive disorder (21).

Other important associations

In a study assessing the prevalence of interictal

dysphoric disorder and interictal personality, significantly more

patients with drug-resistant TLE-MTS had a history of previous

psychiatric treatment (P=0.001), family history of epilepsy

(P=0.001), and family history of psychiatric disorders (P=0.001)

(21).

Current psychiatric disorders in a general

population of epilepsy patients are associated with childhood

maltreatment experiences (25).

Patients with current psychiatric disorders [major depressive

episode, recurrent depressive disorder, dysthymia, social phobia,

specific phobia, panic disorder alone, agoraphobia alone, panic

disorder with agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder,

obsessive-compulsive disorder, adjustment disorder, substance

dependence, eating disorder, psychotic episode-diagnosed as per DSM

IV criteria or posttraumatic stress disorders-diagnosed with

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS)] had suffered significantly

more childhood maltreatment experiences [higher Childhood Trauma

Questionnaire (CTQ) scores-total score (t=3.41, P=0.001), emotional

abuse (t=2.83, P=0.006) and emotional neglect (t=3.47, P=0.001)];

had higher Fragebogen zu Belastenden Sozialerfahrungen (FBS) scores

(t=3.75, P<0.001) and significantly more reported severe

emotional abuse (χ2=13.72, P≤0.001), emotional neglect

(χ2=12.28, P≤0.001), and physical abuse

(χ2=3.98, P=0.046). Age at epilepsy onset, epilepsy

duration, number of different seizure types and number of patients

in each seizure frequency category did not differ between epilepsy

patients with psychiatric disorders and epilepsy patients without

psychiatric disorders. Direct logistic regression showed that CTQ

total score, FBS score and epilepsy-related variables, i.e., age of

epilepsy onset, epilepsy duration, number of seizure types and

seizure frequency, were all predictors for a current psychiatric

disorder [χ2 (9, 120)=27.13, P<0.001, Nagelkerke

R2=0.28) (25).

In a prospective case-control study, designed to

evaluate the psychiatric outcome in drug-resistant epilepsy

patients that underwent surgery, compared with those who did not,

existing differences in baseline affective disorders (major

depressive episodes, recurrent depression, dysthymic disorder,

affective disorder due to a medical condition or substance

disorder, adjustment disorder and bipolar disorder), psychotic

disorders (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and other

psychosis), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, phobia, obsessive

compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other

anxiety disorders), eating disorder, drug use, conduct disorder

(diagnosed as per DSM-IV, not specified if current or lifetime),

interictal dysphoric disorder and interictal psychotic disorder

(diagnosed as per ILAE Classification Proposal) did not depended on

the presence vs. absence of complex partial seizures (CPS), the

cerebral hemisphere involved (left vs. right), and seizure

localization (temporal vs. extratemporal vs. unestablished). Paired

comparisons between baseline and 6 months after surgery showed no

statistical change in all psychiatric disorders mentioned above in

any group (19).

4. Discussion and limitations

This systematic review examined whether current

literature provides quality information on the prevalence and risk

factors for psychiatric disorders in epilepsy patients. In order to

properly treat epilepsy patients with psychiatric comorbidities, it

is very important to have an accurate psychiatric diagnosis, in

patients who are usually attended by neurologists or

epileptologists. Although in recent years numerous screening tools

have been developed and validated for the screening of anxiety

disorders (29) and depressive

disorders (30-33),

in epilepsy patients, these instruments cannot replace a formal

psychiatric assessment (34).

Unfortunately, most recent studies reporting data on psychiatric

comorbidities in epilepsy used these type of instruments and, as a

result, only psychiatric symptoms associated with epilepsy were

reported and analyzed.

The overall reported prevalence of mood/affective

disorders was 12.8 to 34.78%, while the prevalence of specific

diagnoses as per DSM-IV is difficult to assess. In general, a

higher prevalence of mood/affective disorders was reported when the

temporal characteristics (lifetime vs. current) were not specified.

Current and lifetime mood disorders appear to be less frequently

encountered in IGE and more prevalent in focal drug-resistant

epilepsy (mainly TLE). In TLE, the severity of depression was found

to be associated with white matter anomalies in

non-fronto-temporo-limbic areas and with cognitive impairment

(executive function). In focal epilepsies, cognitive depression was

found to be associated with a left-lateralized seizure focus (no

other associations were found between depression and

epileptological variables, antiepileptic drugs or psychotropic

treatments in epilepsy patients with or without depression) and

with cognitive impairment (semantic and autobiographic memory,

delayed auditory-verbal and visual recall). In IGE, depression was

associated with hypoechogenic brainstem raphe (without any

difference on third ventricle width between epilepsy patients with

or without depression).

Suicidal risk was reported only for adults with

childhood onset epilepsy and in this population, it beared no

significant relation with epilepsy. This risk was lower than

previously reported (35), but the

childhood onset epilepsies often have a more favorable course, with

remission in adulthood.

Interictal dysphoric disorder is a highly

controversial epilepsy-specific psychiatric disorder, that is not

recognized by DSM but has specific diagnosis criteria developed by

epileptologists (36). Its

prevalence ranged between 18.4% in resistant TLE-MTS to 35% in a

general population of patients with epilepsy. The results of two

studies are contrasting: In a general sample of epilepsy patients,

interictal dysphoric disorder was more frequently present when

other psychiatric disorders were present and interictal dysphoric

disorder symptoms frequencies were similar in patients with or

without interictal dysphoric disorder, while in resistant TLE-MTS

none of the patients with interictal dysphoric disorders had an DSM

Axis I psychiatric disorder (21,24).

In drug-resistant TLE, the risk factors for interictal dysphoric

disorder were left-sided MTS, previous psychiatric treatment and

the use of more than one antiepileptic drug. In drug-resistant

epilepsies assessed for surgery, the prevalence of interictal

dysphoric disorder was higher in TLE patients as well.

Prevalence of anxiety disorders was between 5.6% in

adults with childhood onset epilepsy and 30.8% in a sample from a

general population of epilepsy patients. As in the case of

mood/affective disorders, the prevalence of specific diagnoses and

temporal characteristics were hard to systemize, but current

anxiety disorders appeared to have a higher prevalence. We

speculate that this trend is related to the long duration of

epilepsy and to the higher severity of seizures in selected

studies. In JME, the presence of anxiety disorders was correlated

with a higher frequency of GTCS and with worse familial adjustment

(no other correlations were found between the presence of anxiety

disorder and other social adjustments domains such as work,

leisure/social or economic).

Psychotic disorders were found to have a low

prevalence across all epilepsy types (2.5-5%), but only four

studies reported data on this psychiatric disorder (18,19,21,24).

Prevalence of psychosis (ictal, interictal) was significantly

higher in patients with early-onset focal epilepsy and its presence

was corelated with longer disease duration and presence of TLE (sex

and age at examination were not contributory to psychosis).

Prevalence of personality disorders was assessed in

three studies (20,21,26).

Personality disorders, under these circumstances, appear to be a

characteristic of JME (but only one study assessed patients with

post-surgical MTLE/HS). When JME, MTLE/HS and control patients were

compared, no significant differences were found regarding normal

personality traits or supposed interictal personality

characteristics between groups.

Interictal personality (also known as

Gastaut-Geschwind Syndrome) (37),

another disorder described only by epileptologists, had a high

prevalence in pharmacoresistant TLE (37.9%), but was not confirmed

when DSM-IV criteria were used. Instead significant correlations

were found between presence of interictal personality and presence

of bilateral MTS, longer disease duration and presence of major

depressive disorder.

Another interesting correlation that was made in

epilepsy patients is the association between childhood maltreatment

experiences, age at epilepsy onset, epilepsy duration, seizure

types, seizure frequency and the presence of any current DSM Axis I

psychiatric disorder. Another study showed that the presence of DSM

Axis I psychiatric disorders, interictal dysphoric disorder and

interictal psychotic disorder in pharmaco-resistant epilepsy do not

depend on the presence vs. absence of complex partial seizures,

lateralization or localization of seizures.

The last study was the only study that assessed the

presence of psychiatric disorders diagnosed per DSM-IV in

pharmacoresistant epilepsies that did not undergo surgery at

baseline and at six months and found that there were no significant

diagnosis changes over a period of 6 months (19).

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in our

analysis resemble to some extent the prevalence reported in a

non-systematic review of literature published in 2004(38), but direct comparison is not possible

because both epilepsy and psychiatric disorder classifications have

changed since its publication.

Our analysis is subject to many limitations. Some

important gaps are present in recent literature. We were not able

to find eligible studies on psychiatric disorders in patients with

single unprovoked seizures or in patients with a recent diagnosis

of epilepsy. Methodology used in the studies selected for this

analysis was highly heterogenous and this did not allow us to

perform a meta-analysis. Most studies included small samples of

epilepsy patients and were conducted in epilepsy units, thus

introducing biases such as exclusion of patients with severe

neurological pathologies, over-representation of TLE,

over-representation of pharmacoresistant epilepsy and exclusion of

patients with less severe epilepsy. Control groups were smaller

than patient samples in eight studies and six studies used control

groups with other pathologies. Formal psychiatric assessment was

not performed in controls in 7 studies. In almost 40% of the

studies, the epilepsy diagnosis was not formulated very clearly.

Epilepsy duration was not specified in three articles, seizure

frequency was not specified in three articles and antiepileptic

drug treatment was not specified in four articles. Even if most

studies included epileptic subtypes in their general sample, the

authors did not stratify the results by subtype. Only four studies

report that psychiatric assessment was performed by qualified

professionals. Three versions of the DSM and nine versions of

structured or semi-structured clinical interviews were used to

diagnose the psychiatric disorders. Finally, in eight studies we

are not sure if the psychiatric disorders reported are current or

lifetime disorders. Specific psychiatric disorder diagnoses are not

mentioned in five studies (only DSM broader category is provided).

As is the case for epilepsy subtypes, even when specific

psychiatric disorders are reported, the authors did not stratify

results by subtype in many cases.

5. Conclusions

The studies included in our analysis are

heterogenous. Objectives, methodology and result reporting were

found to be different in all studies. Psychiatric disorders are

present in a high proportion of epilepsy patients, at least at some

time point in the disease evolution.

Prevalence of any psychiatric disorder observed was

up to 51% in IGE, up to 43.1% in TLE, up to 43.3% in a general

population of patients with epilepsy. The most frequent psychiatric

comorbidities of epilepsy are mood/affective disorders (up to 40%

for lifetime occurrence and up to 23% for current occurrence),

anxiety disorders (up to 30.8% for lifetime occurrence and up to

15.6% for current occurrence), personality disorders (up to 11% in

JME) and psychotic disorders (up to 4% of patients with epilepsy).

Personality disorders and anxiety disorders are more frequently

described (and studied) in IGE patients, while depressive disorders

and psychotic disorders are more frequently described in focal

epilepsy (mainly TLE) and pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Evidence

regarding the presence and prevalence of interictal dysphoric

disorder and interictal personality is contradictory.

Depressive disorders might be associated with

specific brain imaging findings and with cognitive impairment in

focal epilepsy. Anxiety disorders are associated with higher

frequency of generalized tonico-clonic seizures and with worse

social functioning. Psychotic disorders are associated with longer

duration of epilepsy. Childhood maltreatment experiences are a

powerful predictor for the occurrence of psychiatric comorbidities

in epilepsy patients, while data regarding association of other

epilepsy characteristics (age at epilepsy onset, epilepsy duration,

seizure type, seizure localization and lateralization, seizure

frequency) with the presence of psychiatric disorders are

conflicting.

Future research in this area should assess the

presence of psychiatric disorders in newly diagnosed epilepsy/after

a single unprovoked seizure, should include a detailed

sociodemographic description for all patients/controls, should use

standardized assessment tools (including standardized epilepsy and

seizure classification, standardized reporting for seizure

frequency-as recommended by ILAE for clinical practice,

standardized structured clinical interview for diagnosis of

psychiatric disorders) and should stratify data according to the

specific epilepsy and psychiatric diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All information provided in this review is

documented by relevant references.

Authors' contributions

RSG conceived the research protocol (including

search strategy and study inclusion/exclusion criteria),

cross-checked all full articles reviewed and selected by RID,

cross-checked data extracted from the selected studies, performed

the quality assessment of studies included, prepared the manuscript

and modified the manuscript as per the feedback received from AMC

and CAP. AMC reviewed the methodology and the manuscript, provided

feedback, submitted the manuscript and the cover letter. RID

searched the databases, screened title and abstracts, identified

and excluded duplicate titles, assessed the full text articles for

eligibility, excluded articles that did not meet inclusion criteria

or meet the exclusion criteria and extracted relevant data from

selected studies. CAP reviewed the methodology and the manuscript

and provided feedback. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Adela Magdalena Ciobanu: ORCID: ID

0000-0003-2520-5486.

References

|

1

|

World Health Organization (WHO): The

ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical

descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization,

1992.

|

|

2

|

Salpekar JA and Mula M: Common psychiatric

comorbidities in epilepsy: How big of a problem is it? Epilepsy

Behav. 98:293–297. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Michaelis R, Tang V, Goldstein LH, Reuber

M, LaFrance WC Jr, Lundgren T, Modi AC and Wagner JL: Psychological

treatments for adults and children with epilepsy: Evidence-based

recommendations by the international league against epilepsy

psychology task force. Epilepsia. 59:1282–1302. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Vogt VL, Äikiä M, Del Barrio A, Boon P,

Borbély C, Bran E, Braun K, Carette E, Clark M, Cross JH, et al:

Current standards of neuropsychological assessment in epilepsy

surgery centers across Europe. Epilepsia. 58:343–355.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wilson SJ, Baxendale S, Barr W, Hamed S,

Langfitt J, Samson S, Watanabe M, Baker GA, Helmstaedter C, Hermann

BP and Smith ML: Indications and expectations for

neuropsychological assessment in routine epilepsy care: Report of

the ILAE neuropsychology task force, diagnostic methods commission,

2013-2017. Epilepsia. 56:674–681. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G,

Connolly MB, French J, Guilhoto L, Hirsch E, Jain S, Mathern GW,

Moshé SL, et al: ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position

paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology.

Epilepsia. 58:512–521. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Fabiano F and Haslam N: Diagnostic

inflation in the DSM: A meta-analysis of changes in the stringency

of psychiatric diagnosis from DSM-III to DSM-5. Clin Psychol Rev.

80(101889)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lacey CJ, Salzberg MR and D'Souza WJ: Risk

factors for depression in community-treated epilepsy: Systematic

review. Epilepsy Behav. 43:1–7. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Gandy M, Sharpe L and Perry KN:

Psychosocial predictors of depression and anxiety in patients with

epilepsy: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 140:222–232.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Mula M: Developments in depression in

epilepsy: Screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Expert Rev