Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic vascular inflammatory

disease resulting from the buildup of cholesterol-rich fatty

deposits (plaques) in the artery walls and is a major contributor

to cardiovascular mortality (1).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the principal surface membrane component

in the majority of Gram-negative bacteria, is known to cause

vascular inflammation (2). The

endothelial inflammatory response promotes leukocyte adhesion and

increases vascular permeability by increasing the expression levels

of several cell adhesion molecules, including vascular cell

adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1

(ICAM-1), and E-selectin, and via the release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin

(IL)-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)

(3-5).

The activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a critical step in

the inflammatory response, as it regulates the expression of

various inflammatory mediators including cytokines and chemokines,

which promotes cell adhesion and increases endothelial permeability

(4,6,7).

Thus, medications or nutraceuticals that downregulate the

expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and adhesion

molecules, and inhibit the NF-κB pathway, are promising candidates

for the treatment and prevention of atherosclerotic diseases.

Anti-inflammatory drugs are not equally effective in all patients

and are associated with adverse effects that limit their use.

Phytochemicals such as flavonoids, phenylpropanoids,

isothiocyanates, sulforaphanes, indole alkaloids, and sterol

glucosides can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines

and subsequently their signaling pathways (8). Therefore, dietary agents with potent

anti-inflammatory activity and with few or no adverse effects are

promising for treating inflammatory diseases (9).

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) is a

green leafy vegetable that a is rich source of vitamins, minerals,

phenolic compounds, and carotenoids. Its nutrient and phytochemical

contents are associated with a wide range of bioactivities,

including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective,

anti-cancer, anti-obesity, and hypolipidemic activity (10,11).

Vitamin K is naturally found in green leafy vegetables as

phylloquinone (vitamin K1), while menaquinones (vitamin

K2; MK-s, where s represents the number of

isoprenyl side-chain units) are produced by micro-organisms

including intestinal bacteria (12). Furthermore, higher concentrations

of vitamin K1 have been reported in spinach compared

with other foods and beverages (13). Vitamin K is a class of fat-soluble

vitamins and plays important roles in the coagulation cascade,

anti-inflammatory pathways, and in the regulation of serum calcium

levels and bone metabolism, all of which have an effect on

cardiovascular health (14).

Compared with vitamin K1, vitamin K2 has more

physiological benefits as it increases the regulation of

transcription factors that participate in steroid hormone

synthesis, and is associated with increased bone metabolism,

inhibition of vascular calcification, reduction of cholesterol, and

suppression of peripheral inflammation (15-17).

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as starter cultures,

probiotics, and producers of vitamins are vital components of

various food fermentation processes (18). Among LAB, Lactococcus lactis

are natural producers of vitamin K2 (19). Vitamin K2 production has

been observed in various bacteria that are involved in established

food fermentation processes, and the exact mechanism of vitamin

K2 production has been elucidated (20). However, earlier studies mainly

focused on the vitamin K2 levels in fermented dairy

products, with only a few studies focusing on vitamin K2

production by LAB itself (21-23).

Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there are no available

reports on the fermentation of green vegetables such as spinach by

L. lactis.

In this study, it was hypothesized that

biotransformation of vitamin K1 to K2 in

spinach juice (S.juice) during L. lactis-mediated

fermentation can improve its health benefits. Therefore, the

objective the present work was to determine the anti-inflammatory

effects of fermented S.juice including rich vitamin K2

against the LPS-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells

(HUVECs) and to elucidate the potential anti-vascular inflammatory

mechanism.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Antibodies against VCAM-1 (cat. no. 13662), ICAM-1

(cat. no. 4915), and phospho-NF-κB p65 (cat. no. 3033), NF-κB p65

(cat. no. 8242), phospho-IκB-α (cat. no. 2859), IκB-α (cat. no.

9242), β-actin (cat. no. 4967) (all dilution, 1:1,000), and

goat-anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP)

secondary antibodies (dilution, 1:5,000; cat. no. 7074) were

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for MCP-1 (Human MCP-1 ELISA Set;

cat. no. 555179) and IL-6 (Human IL-6 ELISA Set; cat. no. 555220)

were purchased from BD Bioscience. LPS was purchased from Sigma

Chemical Co. The NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents

kit (cat. no. 78833; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used.

Triton X-100 and 10% formalin solution were obtained from

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Additionally,

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and Alexa Fluor dyes (488 and

555) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Isolation and identification of L.

lactis

A strain of L. lactis (KCCM12759P) was

isolated from sediment collected from the fish-farm tank at the

National Institute of Fisheries Science (Pohang, Republic of

Korea). The sediment sample was serially diluted, plated on De Man,

Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) Agar with

bromocresol purple, and incubated anaerobically at 30̊C for 24 h.

For 16s rDNA gene sequencing analysis, the isolated yellow colonies

were transferred to MRS broth, cultured, and DNA was subsequently

extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega

Corporation) following to the manufacturer's method. The 16s rDNA

gene was amplified using 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R

(5'-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') primers. PCR was performed using the

AccPower PCR Premix kit (Bioneer Corporation) on a Takara PCR

Thermal Cycler Dice Gradient system (Takara Bio, Inc). The PCR

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 5 min,

30 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 30 sec, annealing at 55˚C for

30 sec and extension at 72˚C for 90 sec and final extension at 72˚C

for 5 min. The PCR product was analyzed using 1% agarose gel

electrophoresis, purified with a NucleoSpin Gel and PCR clean-up

kit (cat. no. 740609.50; Macherey Nagel, Inc.), and sequenced using

an ABI 3730 sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Homology search was

performed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)

program from the NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The 16s

rDNA of a selected isolate showed 99% similarity with L.

lactis (acc. no. MG754653.1). The L. lactis used in this

study was deposited at the Korean Culture Center of Microorganisms

(KCCM12759P) and stored in vials of MRS broth with 50% (v/v)

glycerol at -70˚C until use.

Preparation of fermented spinach juice

samples

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) was obtained

in April 2020 from an herbal medicine cooperative situated in

Gyeongsang Province, Republic of Korea. The isolated L.

lactis strain (1x108 CFU/ml) was inoculated into 200

ml sterile S.juice and into MRS medium as control, and incubated

anaerobically at 26˚C with agitation for 48 h. S.juice was obtained

by pressing fresh spinach, lyophilized, and 5% (w/v) of S.juice was

calculated as the weight of the dried product, corresponding to the

volume of the juice for fermentation. After fermentation, the

culture solution including the pellet and the residues of spinach

were evaporated three times at 50˚C for 1 h using a rotary

evaporator (N-1000; Eyela); the cell pellet was subsequently washed

with 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4). Vitamin K2 (menaquinone), a

fat-soluble vitamin, is produced during fermentation by bacteria

such as lactic acid bacteria (20). Vitamin K2 is commonly

recovered from microbial cells by liquid-liquid extraction or

supercritical fluid extraction and stored at -70˚C until in

experiments for vitamin K analysis (22,23).

Quantitative analysis of vitamin K in

L. lactis

The vitamin K analysis was performed according to

Liu et al (21) and

Berenjian et al (24) with

minor modifications. Briefly, the cell pellet was added to 6 ml of

resuspension solution (10 mM PBS containing 1% lysozyme) and

incubated at 37˚C for 1 h. Subsequently, 24 ml of extraction buffer

(n-hexane-isopropanol=2:1, v/v; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

was added, vortexed twice at 25˚C for 30 sec, and centrifugation at

3,000 x g for 10 min. Next, the lower phase was collected, an equal

volume of n-hexane was added, then evaporated at 25˚C for 30

min. Subsequently, the dried pellet was dissolved by adding 2 ml

isopropanol; the sample was then filtered with a 0.45 µm syringe

filter (MilliporeSigma) for high-performance liquid chromatography

(HPLC) analysis using an Agilent C18 column (4.6x250 mm; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.), maintained at a temperature of 40˚C during the

analysis. The flow rate, injection volume, and detection wavelength

were 0.4 ml/min, 50 µl, and 254 nm, respectively. Reagent-grade

vitamin K1 and K2 (Sigma Chemical Co.),

dissolved in methanol (0.5% w/v), were used as reference standards.

The mobile phase was a mixture of methanol, isopropanol, and

n-hexane (25:37.5:37.5; v:v:v). The calibration curve was

obtained by plotting the peak area vs. concentration. The slope,

intercept, and correlation coefficients for the calibration curve

were then determined. The analysis was performed in triplicate

(25).

Cell culture and treatment

HUVECs were purchased from Lonza Group, Ltd. and

cultured in EBM-2 basal medium (cat. no. CC-3156; Lonza Group,

Ltd.) supplemented with EGM-2 SingleQuots supplement pack (cat. no.

CC-4176; Lonza Group, Ltd.). HUVECs were incubated at 37˚C with 5%

CO2, and the medium was replaced every 48 h.

Cytotoxicity assays

The cytotoxicity of S.juice and fermented S.juice

was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (CCK-8; Dojindo

Molecular Technologies, Inc.). HUVECs were cultured in 48-well

plates (1x105 cells/well) and pretreated with S.juice or

fermented S.juice at 2 concentrations (200 and 400 µg/ml) for 1 h

at 37˚C, followed by stimulation with LPS (10 µg/ml) for an

incubation of 18 h at 37˚C. Subsequently, 400 µl of CCK-8 working

solution was added to each well and incubated at 37˚C for 1.5 h.

Cell viability was subsequently measured using CCK-8 solution and a

microplate reader set at a detection wavelength of 450 nm (Tecan

Group, Ltd.).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

HUVECs were seeded in 24-well plates

(1x105 cells/well) and treated with LPS in the presence

or absence of S.juice and fermented S.juice at 200 or 400 µg/ml for

18 h. The cell-free supernatant fractions were collected, and the

levels of MCP-1 and IL-6 released into the culture supernatant were

measured using the Quantikine ELISA kits according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

The whole cell proteins were isolated using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis (cat. no. MB-030-0050;

Rockland Immunochemicals Inc.) containing a 1x protease/phosphatase

inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. 5872; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.). The protein quantification was performed using the Bio-Rad

Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Then, 30 µg of proteins

were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane.

The membrane was blocked with EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (cat. no.

12010020; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature,

then incubated with 1:1,000 diluted primary antibodies: VCAM-1,

ICAM-1, phospho-NF-κB, NF-κB, phospho-IκB-α, IκB-α, and β-actin at

4˚C overnight. Following washing with TBST, the membrane was then

incubated with 1:5,000 diluted goat-anti-rabbit IgG-HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The bands were

detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit; Clarity

Max western ECL substrate (cat.no. 1705062; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) and were analyzed using the ImageJ software (version 1.52;

National Institutes of Health).

Nuclear and cytosolic

fractionation

An NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent

kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to extract nuclear

and cytoplasmic proteins. After treatment with S.juice and

fermented S.juice, the HUVEC were homogenized in Cytoplasmic

Extraction Reagent I buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor

cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After homogenization,

the cells were isolated by centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 5 min

at 4˚C in the presence of Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent Ⅱ (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The supernatant of cytoplasmic extract

and left pellet were homogenized in Nuclear Extraction Reagent

buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The cells were subsequently isolated by

centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C; the protein content

of the supernatant (representing the nuclear extract) was

quantified using Pierce™ Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Assay kit (cat.

no. 23236; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Immunofluorescence

After treatment with S.juice and fermented S.juice,

HUVECs were fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min at room temperature

and immersed in 0.1% Triton X-100 (cat. no. T8787; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently,

the cells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (cat. no.

7906; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature

and incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary antibody (NF-κB p65;

dilution, 1:200; cat. no. 8242; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

For fluorescence detection, the cells were incubated for 1 h at 4˚C

in the dark with secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 555 and

488 antibody (dilution 1:500; cat. no. 4413; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 antibody

(dilution 1:200; cat. no. 4412; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

Next, the cells were stained with DAPI solution for the imaging of

the cell nuclei through fluorescence microscopy (IX71; Olympus

Corporation) at the same gain and exposure time.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed at least three

times and all graph bar data are presented as mean ± standard error

of the mean (SEM). The mean values of different groups were

compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by

Tukey's tests (GraphPad Prism 8; GraphPad Software, Inc.). For all

data, statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

Effect of L. lactis fermentation on

vitamin K contents of S.juice

Table I shows the

respective vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 contents

of S.juice and fermented S.juice. Single-strain L.

lactis starters were used to ferment S.juice for 48 h at 26˚C.

The initial LAB cell count was ~1x108 CFU/ml. After 48 h

of fermentation with the L. lactis strains, the LAB cell

count in fermented S.juice was 3.58x1010 CFU/ml. The

vitamin K1 and K2 levels of fermented S.juice

as determined using HPLC were 1.77 and 1.89 µg/ml, respectively

(Table I). The vitamin

K2 content of fermented S.juice was approximately

47-fold higher than in S.juice. There were no significant

differences between the vitamin K1 contents of S.juice

and fermented S.juice.

| Table IVitamin K1 and

K2 contents of S.juice and Lactococcus

lactis-fermented S.juice. |

Table I

Vitamin K1 and

K2 contents of S.juice and Lactococcus

lactis-fermented S.juice.

| | LAB counts

(CFU/ml) | |

|---|

| Sample | Initial | Final | Vitamin

K1 content (µg/ml) | Vitamin

K2 content (µg/ml) |

|---|

| S.juice | - | - | 1.75 | 0.04 |

| Fermented

S.juice |

1x108 |

3.58x1010 | 1.77 | 1.89 |

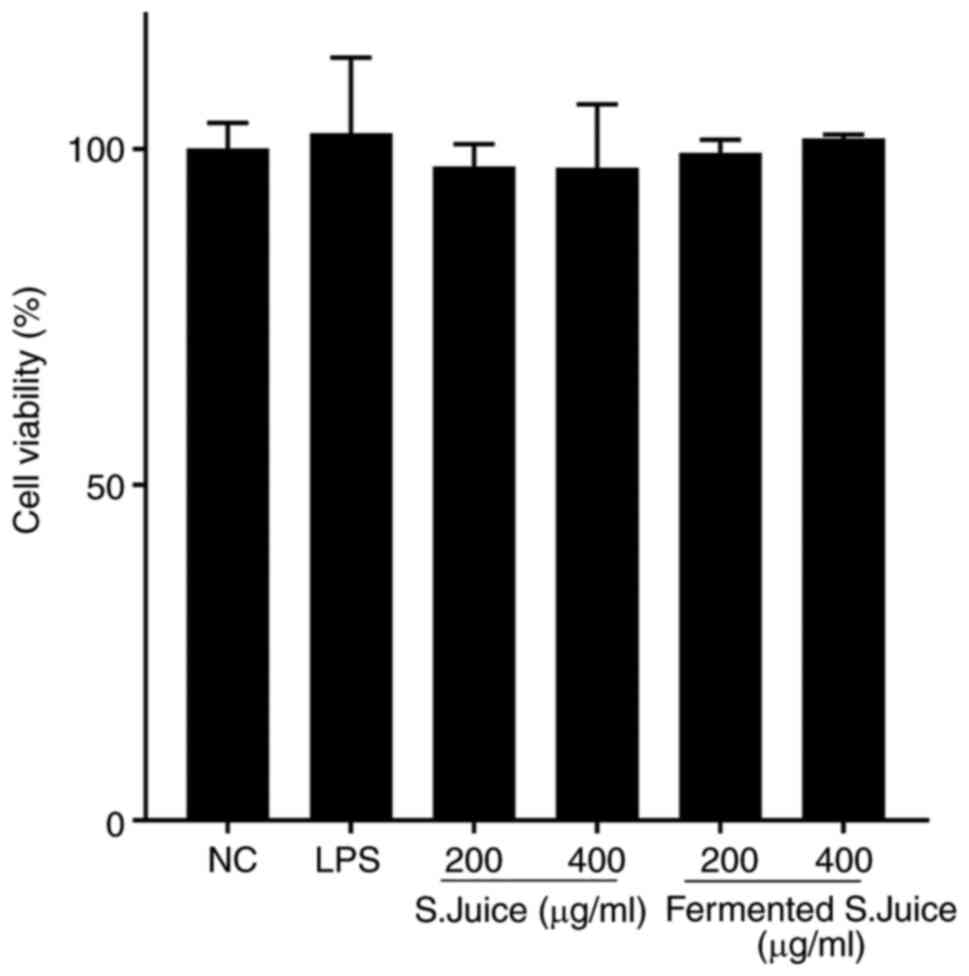

Cytotoxic effects of S.juice and

fermented S.juice in HUVECs

The potential cytotoxic effect of S.juice and

fermented S.juice against HUVECs was evaluated using CCK-8 assays

(Fig. 1). The cell viability was

not affected by S.juice and fermented S.juice at either of the test

concentrations (200 and 400 µg/ml), indicating no toxicity against

HUVECs at these concentrations.

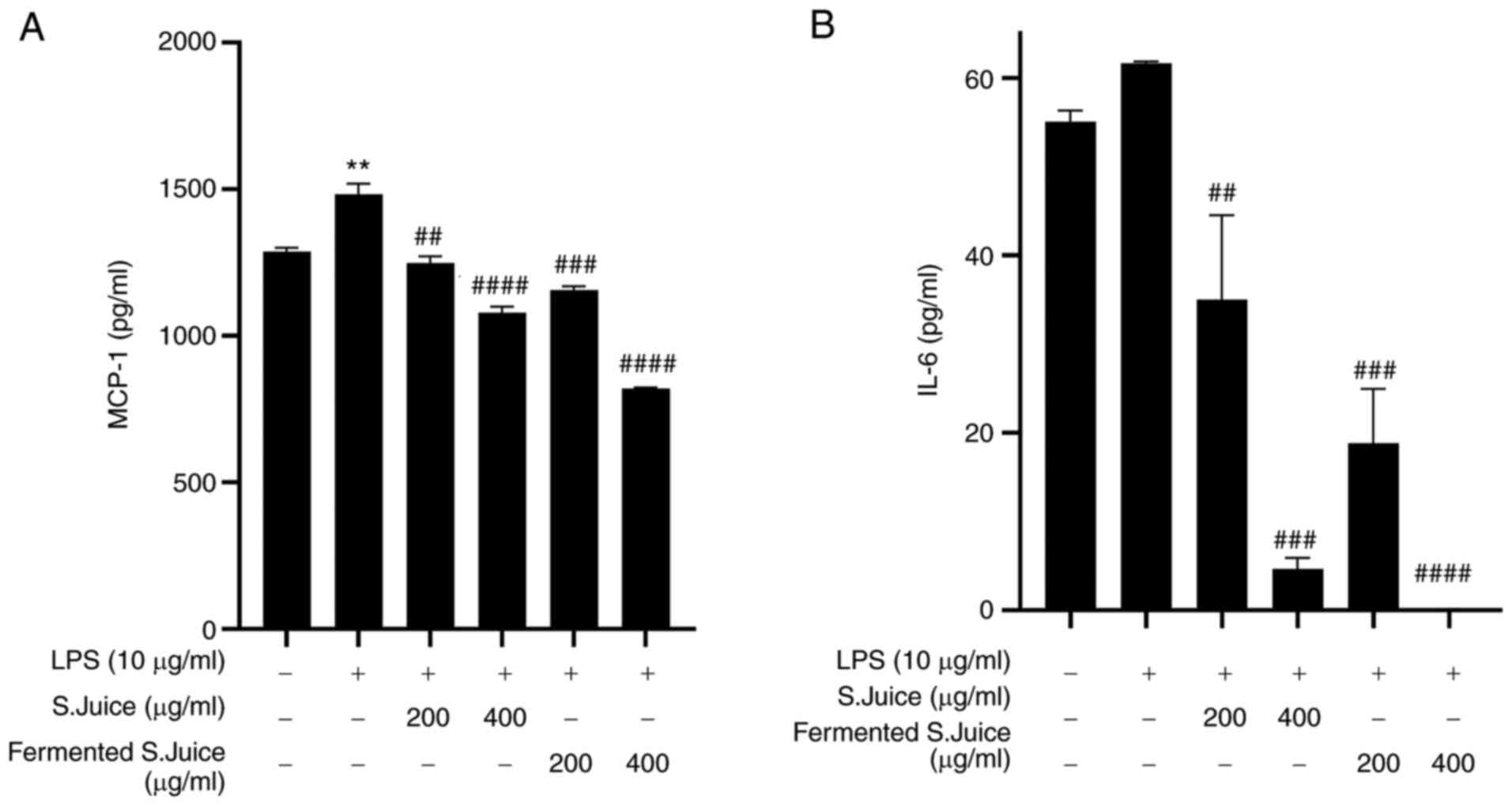

S.juice and fermented S.juice suppress

the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in

LPS-stimulated HUVECs

Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as MCP-1

and IL-6, play critical roles in inflammation (26). Therefore, to investigate the

potential anti-inflammatory effects of LPS-stimulated HUVECs, the

levels of MCP-1 and IL-6 were determined. Stimulation with LPS

significantly increased the production of inflammatory cytokines

such as MCP-1 and IL-6 in HUVECs (Fig.

2). However, the treatment with fermented S.juice of 400 µg/ml

markedly inhibited the levels of MCP-1 and IL-6 compared with the

treatment with S.juice, in a dose-dependent manner.

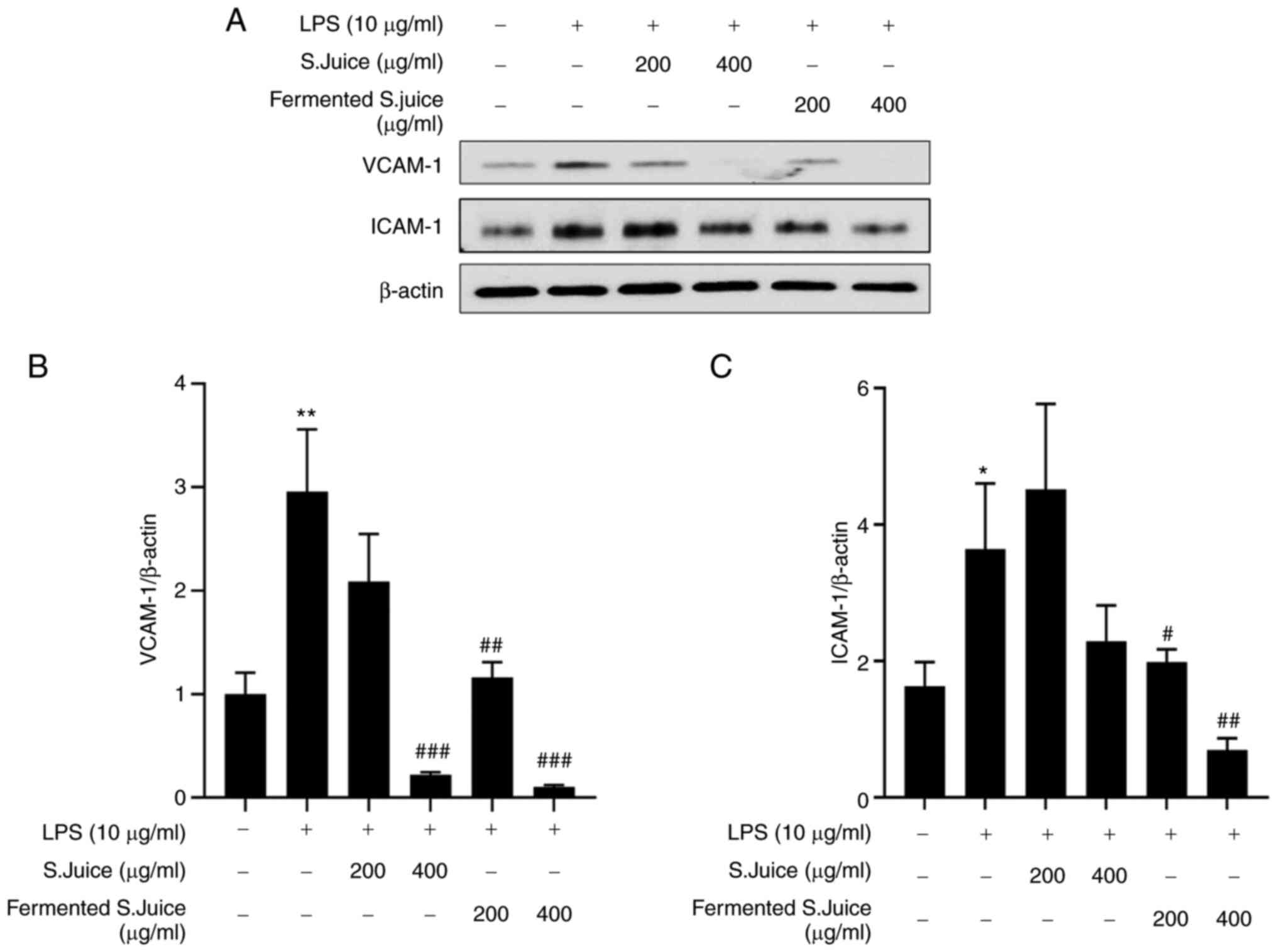

S.juice and fermented S.juice

downregulate the expression of adhesion molecules in LPS-stimulated

HUVECs

Adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 play

major roles in the initial adhesion and subsequent

trans-endothelial migration of leukocytes into inflamed vessels

(26). In this study, the effects

of S.juice and fermented S.juice on the expression VCAM-1 and

ICAM-1 following LPS treatment were determined by western blotting.

The expression of both VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in LPS treatment was

significantly increased compared with the control (Fig. 3A and 3B). However, the increase in the VCAM-1

and ICAM-1 levels following LPS treatment was attenuated both by

S.juice and fermented S.juice in a dose-dependent manner, with the

fermented S.juice exerting a greater effect.

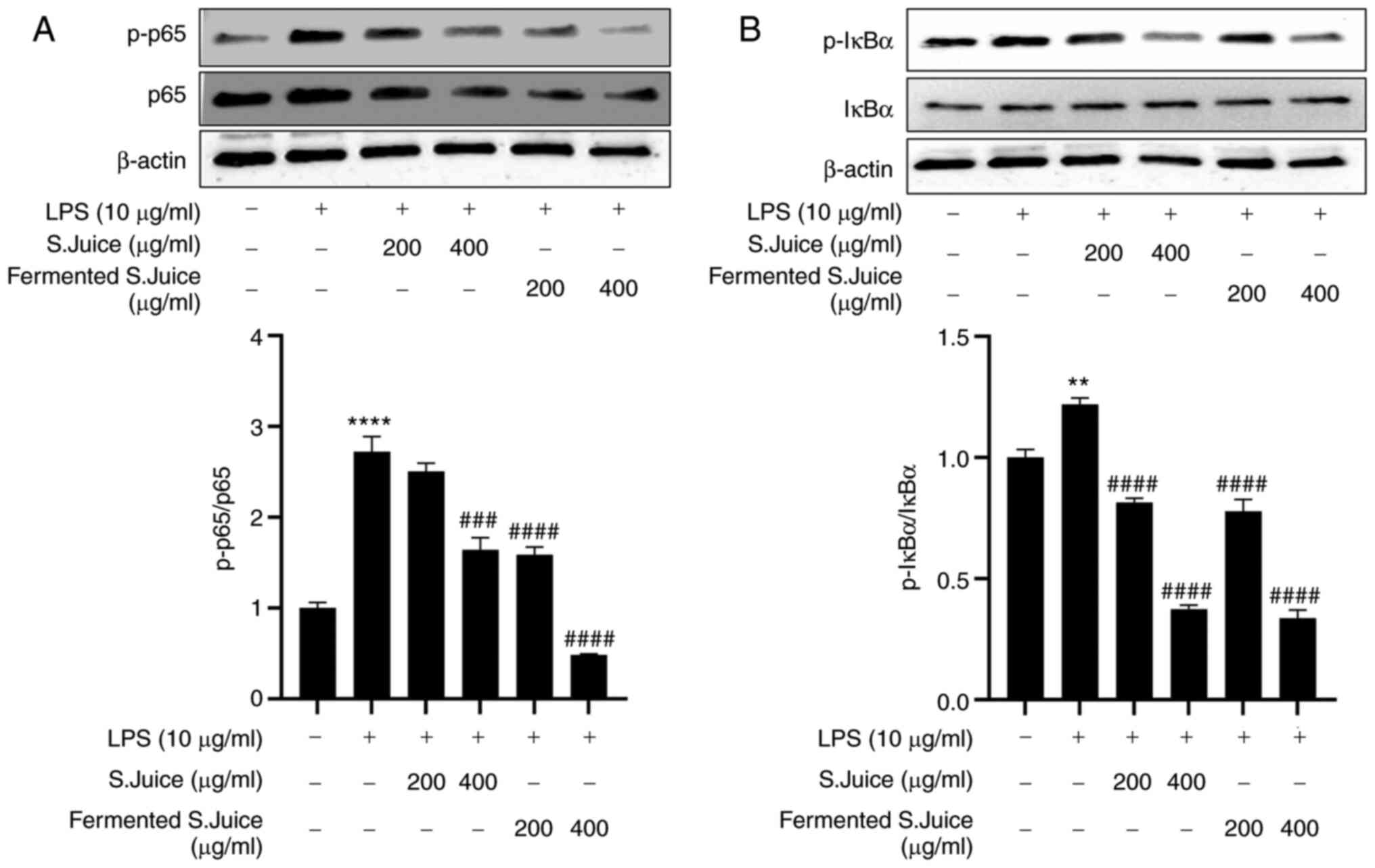

S.juice and fermented S.juice suppress

the LPS-induced activation of NF-κB

NF-κB plays an important role in regulating the

production of inflammatory mediators (27). Cytokines promote inflammation by

promoting NF-κB phosphorylation and IκB-α degradation (28). In this study, the effects of the

S.juice and fermented S.juice on NF-κB activation following LPS

treatment were investigated. The levels of NF-κB activation and

IκB-α degradation were greater following LPS treatment, compared

with the control (Fig. 4).

However, the pre-treatment with S.juice and fermented S.juice

significantly inhibited the activation of NF-κB (Fig. 4A) as well as the degradation of

IκB-α (Fig. 4B) induced by LPS in

a concentration-dependent manner.

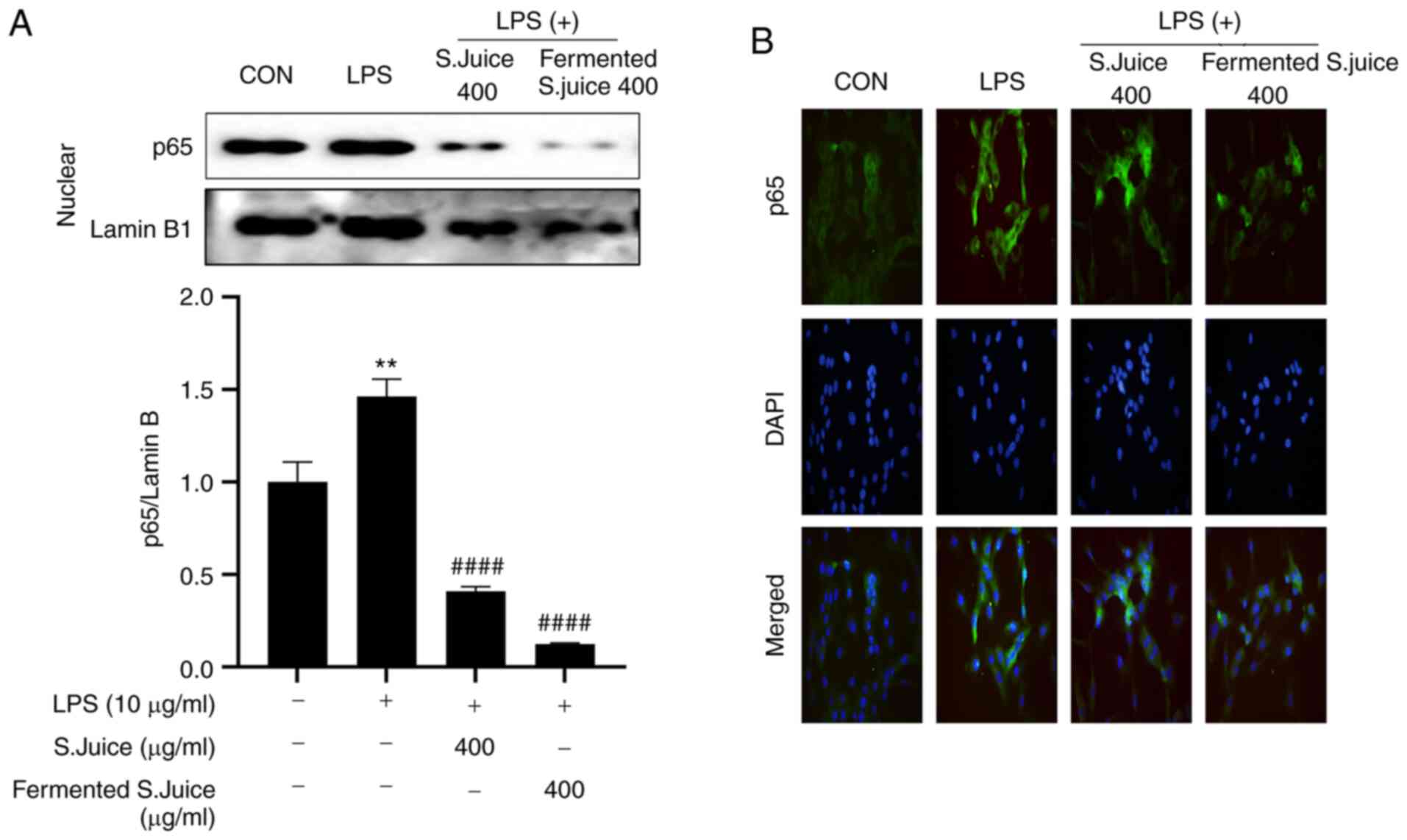

S.juice and fermented S.juice suppress

the NF-κB p65 signaling pathway in HUVECs

Once activated, the NF-κB p65 subunit is

translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and regulates the

expression of target genes (28).

The effect of S.juice and fermented S.juice on LPS-induced nuclear

translocation of NF-κB p65 was investigated. Immunofluorescence

assays demonstrated that the LPS-induced nuclear translocation of

NF-κB p65 was inhibited by both S.juice and fermented S.juice

(Fig. 5). Overall, this indicated

that S.juice and fermented S.juice inhibited the production of

inflammatory factors by suppressing the NF-κB pathway. Furthermore,

fermented S.juice attenuated the LPS-induced expression of NF-κB

p65 to a greater extent than S.juice.

Discussion

The present study is, to the best of our knowledge,

the first characterization of the mechanism involved in the

anti-inflammatory effects of fermented S.juice in HUVECs. Although

spinach has been reported to have strong protective effects against

vascular inflammation, the anti-inflammatory activity of fermented

spinach products remains unclear (10). Fermentation of spinach by L.

lactis may synthesize into bioactive forms such as vitamin

K2, MK4, MK7, MK9 and to more forms (20). First, it has been demonstrated that

vitamin K2, a major bioactive component of the fermented

S.juice, inhibits the endothelial inflammatory response induced by

LPS (16,27). The anti-inflammatory effects

include the suppression of the secretion of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and chemokines and the downregulation of molecules that

facilitate adhesion to endothelial cells (10). Our mechanistic analysis revealed

that the anti-inflammatory effect of fermented S.juice was possibly

mediated via the suppression of NF-κB activation. Thus, to the best

of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that fermented

S.juice attenuates HUVECs-associated inflammatory responses

possibly via the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Spinach is a rich source of vitamins, minerals,

phenolic compounds, and carotenoids that are responsible for its

various bioactivities (10). The

main vitamin in spinach is vitamin K1, which is used for

the microbial biosynthesis of vitamin K2, including that

in intestinal bacteria (12,13).

An in silico study of LAB genome revealed that the genes

encoding enzymes of the vitamin K2 biosynthesis pathway

are different and vary depending on the strain (22,29).

LAB play vital roles in food fermentation processes including

vitamin K2 production (30); among the LAB, L. lactis is

associated with particularly high levels of vitamin K2

production (19,31). Our results indicate that the

vitamin K2 levels in S.juice increase during

fermentation by L. lactis. The fat-soluble vitamin K class,

including vitamin K1 and K2, regulates

vascular calcification, bone metabolism, and inflammation, all of

which may affect cardiovascular health (32). A previous study reported that the

intake of vitamin K2, but not vitamin K1,

reduced the risk of coronary heart disease mortality, all-cause

mortality, as well as severe aortic calcifications (33). The typical recommended dietary

intake of vitamin K in North America varies from 50 to >600

µg/day for vitamin K1, and from 5 to 600 µg/day for

vitamin K2 (34).

Kawashima et al (35)

reported anti-atherosclerotic effects in hypercholesterolemic

rabbits treated with vitamin K2 (MK-7; 1 to 10 mg/kg

body weight/day) including reduced intimal thickening and

ester-cholesterol deposition in the aorta, as well as a slower

progression of atherosclerotic plaques. Vitamin K2

(MK-4) decreased the levels of inflammatory markers such as IL-6,

MCP-1, and TNF-α in the liver (36); this might be attributed to the

anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin K2. Vitamin

K2 (MK-4; 0.1-10 µM) reduced the levels of IL-6, IL-1β,

and TNFα in LPS-induced MG6 mouse microglia-derived cells (37). Excess vitamin K attenuated the

general plasma inflammatory index (38). The overall expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines decreased in this study;

therefore, vitamin K2 might directly suppress the

vascular NF-κB pathway; this is in line with a previous report

(37). In the present study, the

treatment levels of fermented S.juice were 200 and 400 µg/ml; 400

µg/ml fermented S.juice contained approximately 211 µg of vitamin

K2 (MK-4).

Vascular inflammatory responses contribute to the

pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (39), and endothelial cells play an

important role in vascular inflammation (40). Pro-inflammatory stimuli such as LPS

activate the endothelial inflammatory response, resulting in the

secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to the

pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (41). Endothelial inflammatory responses

are characterized by the overproduction of inflammatory mediators,

including pro-inflammatory chemokines (e.g., MCP-1), cytokines

(e.g., IL-6), and adhesion molecules (e.g., VCAM-1 and ICAM-1). In

the present study, LPS significantly upregulated the expression of

MCP-1, IL-6, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1; however, this pro-inflammatory

effect of LPS was significantly inhibited by pretreatment of HUVECs

with S.juice and in particular fermented S.juice.

The inhibitory effect of fermented S.juice on the

expression of inflammatory mediators was similar to that of vitamin

K2, an inhibitor of the NF-κB signaling pathway

(37). These findings indicated

that the LPS-induced secretion of MCP-1, IL-6, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1

in HUVECs was mediated via the NF-κB signaling pathway. In

addition, the inhibitory effect of fermented S.juice on

inflammatory mediators was likely mediated via inhibition of the

NF-κB pathway.

NF-κB is involved in the LPS-induced inflammation

response (42). LPS induces the

phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, as well as the

phosphorylation, release, and nuclear translocation of NF-κB to

activate target gene expression (43,44).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study characterized for

the first time the effects of S.juice and fermented S.juice on the

LPS-induced activation of NF-κB.

These results are not direct evidence that the NF-κB

pathway is suppressed by vitamin K2 to exert a

protective effect against vascular inflammation; however, previous

data that demonstrated the role of vitamin K2 in

suppressing LPS-induced microglial inflammation (36), combined with our results, suggest

that vitamin K2-enriched fermented S.juice may inhibit

LPS-induced inflammation by suppressing the NF-κB signaling

pathway.

In conclusion, this is, to the best of our

knowledge, the first report of the inhibitory effect of fermented

S.juice against LPS-induced inflammation via suppression of NF-κB

signaling and downregulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, IL-6, and MCP-1 in

HUVECs. Our present findings indicate that fermented S.juice might

be a potential novel anti-inflammatory agent against vascular

inflammation or cardiovascular disease induced by inflammation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Yumi Kim (Korea Food Research

Institute, Iseo-myeon, South Korea) for helping with the

immunofluorescence assay.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Korea Food

Research Institute (grant no. E0210102) and the Korea Institute of

Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and

Forestry (grants no. GA119027 and GA121047).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

SMH and SHL conceived and designed the study. ARH

performed the experiments. MJS and BMK performed the data analysis.

SHL wrote the original draft. SHL, SMH and MJS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors discussed the results

and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Awan Z and Genest J: Inflammation

modulation and cardiovascular disease prevention. Eur J Prev

Cardiol. 22:719–733. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Doherty TM, Shah PK and Arditi M:

Lipopolysaccharide, toll-like receptors, and the immune

contribution to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

25(e38)2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Liang J, Yuan S, Wang X, Lei Y, Zhang X,

Huang M and Ouyang H: Attenuation of pristimerin on TNF-α-induced

endothelial inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol.

82(106326)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Huang W, Huang M, Ouyang H, Peng J and

Liang J: Oridonin inhibits vascular inflammation by blocking NF-κB

and MAPK activation. Eur J Pharmacol. 826:133–139. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang L and Wang F, Zhang Q, Kiang Q, Wang

S, Xian M and Wang F: Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects

of Stybenpropol A on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J

Mol Sci. 20(5383)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gao J, Zhao WX, Zhou LJ, Zeng BX, Yao SL,

Liu D and Chen ZQ: Protective effects of propofol on

lipopolysaccharide-activated endothelial cell barrier dysfunction.

Inflamm Res. 55:385–392. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rao C, Liu B, Huang D, Chen R, Huang K, Ki

F and Dong N: Nucleophosmin contributes to vascular inflammation

and endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis progression. J Thora

Cardiovasc Surg. 161:e377–e393. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C

and Jiménez L: Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am J

Clin Nutr. 79:727–747. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Patil KR, Mahajan UB, Unger BS, Goyal SN,

Belemkar S, Surana SJ, Ojha S and Patil CR: Animal models of

inflammation for screening of anti-inflammatory drugs: Implications

for the discovery and development of phytopharmaceuticals. Int J

Mol Sci. 20(4367)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ishii M, Nakahara T, Araho D, Murakami J

and Nishimura M: Glycolipids from spinach suppress LPS-induced

vascular inflammation through eNOS and NK-κB signaling. Biomed

Pharmacother. 91:111–120. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Roberts JL and Moreau R: Functional

properties of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) phytochemicals

and bioactives. Food Funct. 7:3337–3353. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Shearer MJ and Newman P: Metabolism and

cell biology of vitamin K. Thromb Haemost. 100:530–547.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Booth SL, Davidson KW and Sadowski JA:

Evaluation of an HPLC method for the determination of phylloquinine

(vitamin K1) in various food matrixes. J Agric Food Chem.

42:295–300. 1994.

|

|

14

|

McCann JC and Ames BN: Vitamin K, an

example of triage theory: Is micronutrient inadequacy linked to

diseases of aging? Am J Clin Nutr. 90:889–907. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ichikawa T, Horie-Inoue K, Ikeda K,

Blumberg B and Inoue S: Steroid and xenobiotic receptor SXR

mediates vitamin K2-activated transcription of extracellular

matrix-related genes and collagen accumulation in osteoblastic

cells. J Biol Chem. 281:16927–16934. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ohsaki Y, Shirakawa H, Miura A, Giriwono

PE, Sato S, Ohashi A, Iribe M, Goto T and Komai M: Vitamin K

suppresses the lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of

inflammatory cytokines in cultured macrophage-like cells via the

inhibition of the activation of nuclear factor κB through the

repression of IKKα/β phosphorylation. J Nutr Biochem. 21:1120–1126.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yokoyama T, Miyazawa K, Naito M, Toyotake

J, Tauchi T, Itoh M, You A, Hayashi Y, Georgescu MM, Kondo Y, et

al: Vitamin K2 induces autophagy and apoptosis simultaneously in

leukemia cells. Autophagy. 4:629–640. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bintsis T: Lactic acid bacteria as starter

cultures: An update in their metabolism and genetics. AIMS

Microbiol. 4:665–684. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bøe CA and Holo H: Engineering

Lactococcus lactis for increased vitamin K2 production.

Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 8(191)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang Z, Liu L, Liu C, Sun Y and Zhang D:

New aspects of micrbial vitamin K2 production by expanding the

product spectrum. Microb Cell Fact. 20:84–96. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Liu Y, van Bennekom EO, Zhang Y, Abee T

and Smid EJ: Long-chain vitamin K2 production in Lactococcus

lactis is influenced by temperature, carbon source, aeration

and mode of energy metabolism. Micro Cell Fact.

18(129)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chollet M, Guggisberg D, Portmann R, Risse

MC and Walther B: Determination of menaquinone production by

Lactococcus spp. and propionibacteria in cheese. Int Dairy J.

75:1–9. 2017.

|

|

23

|

Morishita T, Tamura N, Makino T and Kudo

S: Production of menaquinones by lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci.

82:1897–1903. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Berenjian A, Mahanama R, Talbot A, Biffin

R, Regtop H, Valtchev P, Kavanagh J and Dehghani F: Efficient media

for high menaquinone-7 production: Response surface methodology

approach. N Biotechnol. 28:665–672. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Irvan Atsuta Y, Saeki T, Daimon H and

Fujie K: Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of ubiquinones and

menaquinones from activated sludge. J Chromatogr A. 1113:14–19.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Bhaskar S, Sudhakaran PR and Helen A:

Quercetin attenuates atherosclerotic inflammation and adhesion

molecule expression by modulating TLR-NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell

Immunol. 310:131–140. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Li X, Tang Y, Ma B, Wang Z, Jiang J, Hou

S, Wang S, Zhang J, Deng M, Duan Z, et al: The peptide lycosin-I

attenuates TNF-α-induced inflammation in human umbilical vein

endothelial cells via IκB/NF-κB signaling pathway. Inflamm Res.

67:455–466. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Han BH, Song CH, Yoon JJ, Kim HY, Seo CS,

Kang DG, Lee YJ and Lee HS: Anti-vascular inflammatory effect of

ethanol extract from Securinega suffruticosa in human umbilical

vein endothelial cells. Nutrients. 12(3448)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Watthanasakphuban N, Virginia LJ, Haltrich

D and Peterbauer C: Analysis and reconstitution of the menaquinone

biosynthesis pathway in lactiplantibacillus plantarum and

lentilactibacillus buchneri. Microorganisms. 9(1476)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liu Y, Charamis N, Boeren S, Blok J, Lewis

AG, Smid EJ and Abee T: Physiological roles of short-chain and

long-chain menaquinones (vitamin K2) in Lactococcus cremoris. Front

Microbiol. 13(823623)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Garrigues C and Pederson MB:

Lactococcus lactis strain with high vitamin K2 production.

US Patent 8765118B2. Filed August 11,. 2011, issued March 15,

2012.

|

|

32

|

Fusaro M, Gallieni M, Rizzo MA, Stucchi A,

Delanaye P, Cavalier E, Moysés RMA, Jorgetti V, Iervasi G, Giannini

S, et al: Vitamin K plasma levels determination in human health.

Clin Chem Lab Med. 55:789–799. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Geleijnse JM, Vermeer C, Grobbee DE,

Schurgers LJ, Knapen MH, van der Meer IM, Hofman A and Witteman JC:

Dietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of

coronary heart disease: The Rotterdam study. J Nutr. 134:3100–3105.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Marles RJ, Roe AL and Oketch-Rabah HA: US

pharmacopeial convention safety evaluation of menaquinone-7, a form

of vitamin K. Nutr Rev. 75:553–578. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kawashima H, Nakajima Y, Matubara Y,

Nakanowatari J, Fukuta T, Mizuno S, Takahashi S, Tajima T and

Nakamura T: Effects of vitamin K2 (menatetrenone) on

atherosclerosis and blood coagulation in hypercholesterolemic

rabbits. Jpn J Pharmacol. 75:135–143. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Weisell J, Ruotsalainen AK, Näpänkangas J,

Jauhiainen M and Rysä J: Menaquinone 4 increases plasma lipid

levels in hypercholesterolemic mice. Sci Rep.

11(3014)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Saputra WD, Aoyama N, Komai M and

Shirakawa H: Menaquinone-4 suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced

inflammation in MG6 mouse microglia-derived cells by inhibiting the

NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 20(2317)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Shea MK, Booth SL, Massaro JM, Jacques PF,

D'Agostino RB Sr, Dawson-Hughes B, Ordovas JM, O'Donnell CJ,

Kathiresan S, Keaney JF Jr, et al: Vitamin K and vitamin D status:

Associations with inflammatory markers in the Framingham offspring

study. Am J Epidemiol. 167:313–320. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chistiakov DA, Sobenin IA and Orekhov AN:

Regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis and strategies to induce the

endogenous atheroprotective immune response. Immunol Lett.

151:10–22. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Makó V, Czúcz J, Weiszhár Z, Herczenik E,

Matkó J, Prohászka Z and Cervenak L: Proinflammatory activation

pattern of human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced by IL-1β,

TNF-α, and LPS. Cytometry A. 77:962–970. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Xiao L, Liu Y and Wang N: New paradigms in

inflammatory signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol

Heart Circ Physiol. 306:H317–H325. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Fu Y, Wei Z, Zhou E, Zhang N and Yang Z:

Cyanidin-3-O-β-glucoside inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced

inflammatory response in mouse mastitis model. J Lipid Res.

55:1111–1119. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Baker RG, Hayden MS and Ghosh S: NF- κB,

inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 13:11–22.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Khakpour S, Wilhelmsen K and Hellman J:

Vascular endothelial cell Toll-like receptor pathway in sepsis.

Innate Immun. 21:827–846. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|