Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematological malignancy

characterized by the clonal proliferation of plasma cells within

the bone marrow, leading to disruption of normal hematopoiesis and

immune regulation (1,2). This dysregulation results in a wide

range of systemic complications, including anemia,

immunosuppression, osteolytic lesions, hypercalcemia and renal

dysfunction (3). Although MM

primarily involves the bone marrow, extramedullary manifestations

occur in ~4% of cases, with cutaneous involvement being

exceptionally rare and affecting <1% of patients (4).

Cutaneous features of MM are diverse and often

non-specific, including conditions such as light chain amyloidosis,

cryoglobulinemia, xanthomatosis, polyneuropathy, organomegaly,

endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy and skin changes syndrome,

and sclerodermoid changes (5,6).

Among these, follicular spicules of MM (FSMM) represent an uncommon

but highly specific dermatological finding. Clinically, FSMM

presents as fine, keratotic, spiny projections emerging from hair

follicles, predominantly distributed over the nasal and facial

regions (7). Histopathological

examination typically reveals eosinophilic keratinous material

within the follicles, frequently containing monoclonal

immunoglobulin deposits that correspond to circulating paraproteins

(8).

The precise pathogenesis of FSMM remains poorly

defined (9). Recent studies have

emphasized that abnormal deposition of monoclonal proteins within

the follicular epithelium may contribute to the development of

hyperkeratotic changes (10-12).

Furthermore, a recent case report in patients with advanced chronic

kidney disease (CKD) highlighted the diagnostic challenge in

distinguishing FSMM from other CKD-associated skin changes

(12). Differential diagnoses

include other hyperkeratotic conditions such as vitamin A

deficiency, CKD-related dermatoses, HIV/acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome and paraneoplastic syndromes; however, FSMM can be

reliably distinguished through histological and immunofluorescence

analysis demonstrating MM-specific monoclonal protein deposition

(13).

The present report describes a clinically and

histologically confirmed case of FSMM in a 59-year-old man with

newly diagnosed MM and end-stage renal disease undergoing

hemodialysis. The case details, including dermatological,

hematological, as well as histopathological findings, underscore

the diagnostic value of FSMM as an early cutaneous marker of MM.

The present case contributes to the limited literature on FSMM,

emphasizing the importance of dermatological vigilance and

suggesting that prompt recognition of this rare phenotype may

facilitate earlier diagnostic workup and improved patient

management.

Case report

Patient information and clinical

evaluation

The present report describes the case of a

59-year-old male patient diagnosed with MM and stage 5 CKD.

Clinical data, including medical history, symptoms and physical

examination findings, were collected at the time of hospital

admission in February 2024 at The First Affiliated Hospital of

Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College (Chongqing, China).

The patient underwent a comprehensive assessment involving

hematological analysis, biochemical tests, karyotype analysis,

immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) and bone marrow biopsy. The

serum vitamin A levels of the patient were within the normal range.

Additionally, the patient tested negative for HIV via both

serological and molecular methods.

Laboratory tests

Venous blood samples were collected in

EDTA-containing tubes. The samples were allowed to clot at room

temperature for 30 min and then centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 10 min

at 4˚C. The resulting supernatant (serum) was carefully extracted

and used for biochemical and immunoassay analyses. Complete blood

count was performed using an automated hematology analyzer (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.). Serum calcium, creatinine, globulin, total protein

and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were measured using a

biochemical analyzer (Roche Cobas 8000; Roche Diagnostics). Serum

protein electrophoresis (SPE) and IFE were conducted using an

agarose gel electrophoresis system (Sebia). Thyroid function tests,

IL-6 and calcitonin levels were measured using

electrochemiluminescence immunoassay kits (cat. no. 07027838 for

IL-6 and cat. no. 05109342 for calcitonin; Roche Elecsys; Roche

Diagnostics), and assays were performed on a Cobas e801 analyzer in

accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. Serum ferritin and

folate levels were determined using chemiluminescence immunoassay

kits (cat. no. 7K61 for ferritin and cat. no. 8K41 for folate;

Abbott Architect) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Serum

albumin was measured using the same biochemical analyzer (Roche

Cobas 8000; Roche Diagnostics) following the manufacturer's

guidelines.

Karyotype analysis

Peripheral blood samples were collected in

heparinized tubes and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% phytohemagglutinin-M

(cat. no. L8754; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA;) for 72 h at 37˚C in a

5% CO2 incubator. After incubation, colchicine (cat. no.

C9754; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added at a final

concentration of 0.1 µg/ml and the cells were incubated for an

additional 2 h at 37˚C. Following colchicine treatment, lymphocytes

were harvested by centrifugation (1,000 x g for 10 min) and

hypotonic treatment using 0.075 M KCl for 20 min at 37˚C. Cells

were then fixed with freshly prepared in methanol:acetic acid (3:1)

fixative at room temperature for 30 min (three changes). Metaphase

chromosome spreads were prepared and subjected to G-banding using

standard trypsin-Giemsa staining. Chromosomal abnormalities were

analyzed under a light microscope (Olympus BX53; Olympus

Corporation) and described in accordance with the International

System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN 2020) (14).

SPE and IFE

SPE was performed using a semi-automated agarose gel

electrophoresis system (Hydrasys 2 Scan; Sebia) according to the

manufacturer's protocol, to detect the presence of monoclonal

M-spike bands in the γ region. IFE was conducted using antisera

specific for IgG, IgA, IgM, and κ and λ light chains (Hydragel IF

kit; cat. no. 4460; Sebia) following the manufacturer's

instructions. After electrophoresis and fixation, the gels were

stained and imaged using a gel documentation and analysis system

(Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Bone marrow biopsy and

histopathological examination

A bone marrow biopsy was performed under local

anesthesia using 2% lidocaine hydrochloride (5 ml; Hubei Tianyao

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.). The procedure was conducted using an

11-gauge Jamshidi needle (Cardinal Health Canada, Inc.). The biopsy

specimen was immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin

(Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature

(20-25˚C) for 24 h, followed by decalcification in 10% EDTA

solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) for 48 h. Samples

were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 4-µm

slices using a microtome. The sections were rehydrated in

descending alcohol series (100, 95, 85 and 75% ethanol) and rinsed

with PBS (pH 7.4). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was

performed using Mayer's hematoxylin (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 5 min at room temperature, followed by eosin (1%)

staining for 2 min at room temperature (20-25˚C). Slides were

washed and mounted for microscopic observation under a light

microscope (BX53, Olympus Corporation).

For immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis,

paraffin-embedded sections underwent antigen retrieval in citrate

buffer (pH 6.0; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 95˚C for

20 min using a water bath. After cooling and washing with PBS,

endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen

peroxide for 10 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding was

blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 20 min at room temperature. No permeabilization step was

applied, as all antibodies targeted surface or membrane-associated

antigens. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4˚C,

including: CD138 (cat. no. ab34164; dilution 1:100; Abcam), CD56

(cat. no. ab75813; dilution 1:200; Abcam), κ light chain (cat. no.

ZM-0317; dilution 1:150; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) and λ light

chain (cat. no. ZM-0318; dilution 1:150; Origene Technologies,

Inc.). After cooling, sections were washed with phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS, pH 7.4). After washing, HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies (goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG; cat. no. PV-6000; dilution

1:200; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were

applied for 30 min at room temperature. Visualization was achieved

using 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (cat. no. ZLI-9018; Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) as the chromogenic substrate,

followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. Slides were observed

under a light microscope (Olympus BX53; Olympus Corporation).

Appropriate positive and negative controls were included for each

staining run. IHC procedures were performed using the automated

BenchMark ULTRA staining system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) according

to manufacturer protocols where applicable.

Findings. Basic information

The patient was a 59-year-old man with a medical

history significant for stage 5 CKD, who was receiving maintenance

hemodialysis. The patient presented in February 2024 with

complaints of generalized weakness persisting for 2 days. Over the

previous month, the patient had been hospitalized in the Department

of Gastroenterology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing

Medical and Pharmaceutical College for symptoms including cough,

sputum production and melena. Laboratory findings during that

hospitalization revealed impaired renal function and anemia,

ultimately leading to the diagnosis of stage 5 CKD. The patient had

been undergoing regular hemodialysis three times per week, with

hemoglobin levels consistently maintained at ~60 g/l (normal range,

120-160 g/l), indicating persistent moderate-to-severe anemia.

Clinical observations included notable anemia,

hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia and general malaise. Additionally,

the patient experienced an intermittent cough with hemoptysis,

melena of unspecified quantity and progressive abdominal

distension. Despite these symptoms, urination remained normal, and

the patient had a significant unintentional weight loss of ~9 kg.

Prior to the onset of these symptoms, the patient had been

generally healthy, and had no history of hypertension, coronary

artery disease or diabetes mellitus.

At the time of admission in February 2024, the

patient reported a prior diagnosis of hypothyroidism and had been

taking levothyroxine sodium at a dose of 50 µg per day for the past

2 months. They had no known history of dysentery, malaria, viral

hepatitis, tuberculosis or other infectious diseases, nor any known

exposure to hepatitis or tuberculosis. The patient denied any

history of trauma, blood transfusions, drug allergies or food

allergies.

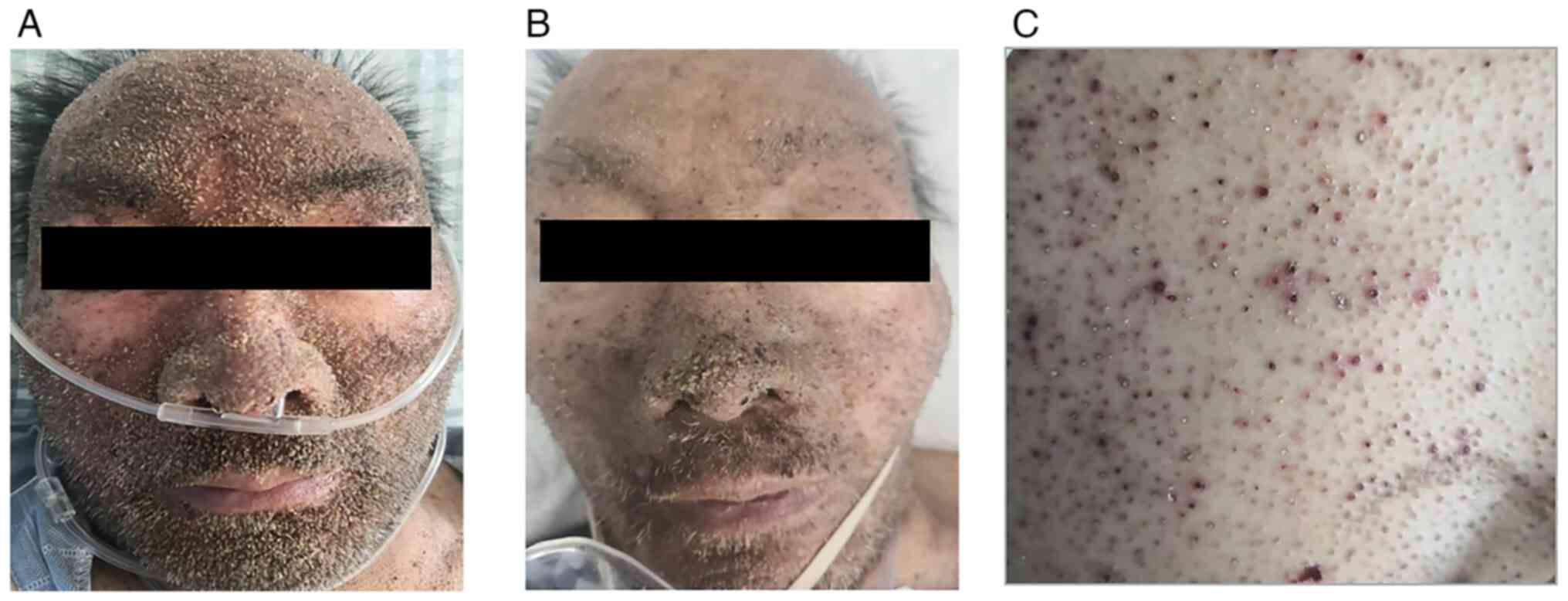

Physical examination. On presentation, the

patient was alert and oriented, with a dusky complexion.

Dermatological examination revealed numerous dense, pinpoint, brown

keratotic papules on the facial skin, consistent with the cutaneous

manifestations of MM.

The vital signs of the patient were as follows: Body

temperature, 36.4˚C (normal, 36.1-37.2˚C); pulse rate, 106 beats

per min (normal, 60-100 bpm); respiratory rate, 20 breaths per min

(normal, 12-20 breaths per min); and blood pressure, 115/78 mmHg

(normal, 90/60-120/80 mmHg). Respiratory system findings included

the following: Auscultation revealed slightly coarse breath sounds

bilaterally, with no evidence of dry or wet rales. Cardiovascular

system findings included the following: The heart rate was regular,

and no murmurs were detected in any of the cardiac valve regions.

In addition, the abdomen was flat, with periumbilical pigmentation;

it was soft, non-tender and exhibited no rebound tenderness or

muscle rigidity. Murphy's sign was negative and no mobile turbidity

was detected. In addition, bowel sounds were normal. In the lower

extremities, no edema was observed in either lower limb. Additional

findings included a 3-cm surgical scar on the left wrist. A

palpable tremor (thrill) was identified at the site of a previously

constructed arteriovenous fistula (AVF) for hemodialysis, located

on the left forearm. A continuous vascular murmur (bruit) was also

audible upon auscultation, consistent with a functioning AVF.

Inspection results. The physical examination

indicators of the patient are shown in Table I. Regarding the hematological

analysis, the patient exhibited anemia with a reduced red blood

cell count (1.54x1012/l), hemoglobin level (46 g/l) and

blood platelet count (75x109/l), which were all below

the reference ranges. The white blood cell count was within normal

limits. CRP levels were elevated at 13.09 mg/l (reference value,

≤10 mg/l) suggesting an inflammatory state. Notably high levels of

calcitonin (3.77 ng/ml; reference value, <0.15 ng/ml) and IL-6

(6,124.5 pg/ml; reference value, <6.6 pg/ml) were detected,

indicating an immune and inflammatory response associated with the

disease. The liver and kidney function test results were as

follows: Serum calcium was elevated at 2.96 mmol/l (reference

value, 2.25-2.75 mmol/l) and creatinine was markedly raised (566.53

µmol/l; reference value, 53-106 µmol/l), indicating renal

impairment. Protein markers, such as globulin (64.73 g/l; reference

value, 20-40 g/l) and total protein (102.86 g/l; reference value,

63-82 g/l), were also elevated.

| Table IPhysical examination indicators of

the patient. |

Table I

Physical examination indicators of

the patient.

| Variable | Inspection

results | Reference

value |

|---|

| Hematological

analysis | | |

|

White blood

cell count, x109/l | 4.63 | 3.50-9.50 |

|

Red blood

cell count, x1012/l | 1.54 | 4.0-5.50 |

|

Hemoglobin,

g/l | 46.00 | 120-160 |

|

Blood

platelet count, x109/l | 75.00 | 100-300 |

| C-reactive protein,

mg/l | 13.09 | ≤10.0 |

| Calcitonin,

ng/ml | 3.77 | <0.15 |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 6,124.50 | <6.60 |

| Liver and kidney

function analysis | | |

|

Serum

calcium, mmol/l | 2.96 | 2.25-2.75 |

|

Creatinine,

µmol/l | 566.53 | 53-106 |

|

Globulin,

g/l | 64.73 | 20-40 |

|

Total

protein, g/l | 102.86 | 63-82 |

| Serum protein

electrophoresis results | | |

|

Albumin,

g/l | 46.00 | 35-55 |

|

α1 globulin,

g/l | 3.10 | 0.01-0.03 |

|

M protein,

% | 36.70 | - |

|

Globulin,

g/l | 49.53 | 20-40 |

|

Serum κ

light chain, g/l | 3.87 | 6.29-13.50 |

|

Serum λ

light chain, g/l | 52.00 | 3.13-7.23 |

|

Immunoglobulin

A, g/l | 12.2 | 0.80-4.53 |

|

Immunoglobulin

G, g/l | 4.87 | 7.51-15.60 |

|

Immunoglobulin

M, g/l | 0.14 | 0.46-3.04 |

| Hepatitis B virus

surface antibody, mIU/ml | 909.71 | 0-10 |

| Hepatitis B virus

core antibody, IU/ml | 0.62 | <0.35 |

| Hepatitis B Virus e

antibody, IU/ml | <0.100 | <0.15 |

| Hepatitis B virus e

antigen, IU/ml | <0.050 | <0.10 |

| Thyroid function

tests | | |

|

Triiodothyronine,

nmol/l | 0.93 | 1.6-3.0 |

|

Thyrotropin,

mIU/l | 0.59 | 0.4-5.0 |

| Anemia tests | | |

|

Ferritin,

ng/ml | >3,000 | 25-350 |

|

Folate,

ng/ml | 3.03 | 5.21-20 |

SPE results indicated that the M protein percentage

was 36.7%, characteristic of monoclonal gammopathy. Other

immunoglobulin abnormalities included elevated IgA (12.2 g/l;

reference value, 0.71-3.35 g/l) and an increased λ light chain

(52.0 g/l; reference value, 3.13-7.23 g/l), further indicating a

monoclonal protein spike. Furthermore, the patient had a high level

of hepatitis B virus surface antibody (909.71 mIU/ml; reference

value, 0-10 mIU/ml), with normal levels for other hepatitis

markers. Thyroid function tests demonstrated a reduced

triiodothyronine level (0.93 nmol/l; below the normal range),

whereas thyrotropin (0.59 mIU/l) was within the reference range.

The results of the anemia test revealed that ferritin levels were

high (>3,000 ng/ml; reference value, 25-350 ng/ml), suggesting

chronic disease-related anemia, whereas folate levels were low

(3.03 ng/ml; reference value, 5.21-20 ng/ml), which could

contribute to anemia. These results indicated a comprehensive

systemic involvement in the patient, which supported the diagnosis

and informed the clinical management of MM with associated

complications, including anemia, renal insufficiency and immune

dysregulation.

Karyotype analysis results. The karyotype

analysis of the patient revealed extensive chromosomal

abnormalities consistent with MM and indicative of notable genetic

instability. The ISCN results were as follows:

‘83-85<4n>,XXY,-Y,+1,+1,dic(1;10)(p13;q26),psu idic(1)(p21),add(7)(q32),add(8)(p23) x2,?add(17)(q22)x2,-19,-19,-20,-21,-21,-22,+1-2mar,inc[cp4]/46,

XY[16]’.

The key findings in the present study included: i)

Hyperdiploidy with tetraploid cells (83-85 chromosomes), the

presence of tetraploid cells (83-85 chromosomes) indicates

hyperdiploidy, which is often associated with advanced disease. ii)

extra X chromosome (XXY), the additional X chromosome is an unusual

finding and may reflect somatic changes linked to malignancy. iii)

loss of Y chromosome (-Y), the absence of the Y chromosome is

frequently observed in hematological malignancies and is considered

a marker of disease progression in MM. iv) polysomy of chromosome 1

(+1,+1), the addition of two extra copies of chromosome 1 suggests

high-level polysomy, which is commonly associated with aggressive

forms of myeloma and may indicate a poorer prognosis. v) dicentric

chromosome [dic(1;10)(p13;q26)], the presence of a dicentric

chromosome formed by the fusion of chromosomes 1 and 10 suggests

structural chromosomal instability, which can serve a role in

tumorigenesis. vi) pseudo-isodicentric chromosome [psu

idic(1)(p21)], this abnormality in

chromosome 1, featuring duplication and inversion, reflects further

chromosomal rearrangement, indicative of genomic instability. vii)

additional material on chromosomes 7, 8, and 17: Specifically noted

in the ISCN as add(7)(q32),

add(8)(p23)x2, and ?add(17)(q22)x2, the term ‘add’ indicates the

presence of unidentified extra chromosomal material at these loci.

These changes may represent gene amplifications or rearrangements

involved in disease progression. viii) losses of chromosomes 19,

20, 21 and 22 (-19,-20,-21,-22), the deletion of these chromosomes

further supports the presence of extensive genomic instability,

often seen in advanced stages of MM. ix) marker chromosomes (mar),

the presence of 1-2 marker chromosomes signifies structurally

abnormal, unidentifiable chromosomes, which are frequently observed

in hematological malignancies and represent complex karyotypic

alterations. x) mosaicism (inc[cp4]/46,XY[16]), the karyotype

exhibits mosaicism, with four abnormal cell clones (cp4) and 16

cells with a normal male karyotype (46,XY). This mosaic pattern

suggests clonal evolution within the disease (Fig. 1).

![Karyotype analysis revealing complex

chromosomal abnormalities in advanced MM. Conventional karyotyping

revealed multiple numerical and structural abnormalities (red

arrows) characteristic of high-risk MM: i) Hyperdiploidy with

tetraploid cells (83-85<4n>,XXY), including an additional X

chromosome. ii) Loss of Y chromosome (-Y), a common finding in

hematological malignancies. iii) High-level polysomy of chromosome

1 (+1,+1), totaling four copies, indicating aggressive disease. iv)

Dicentric chromosome [dic(1;10)(p13;q26)], suggesting genomic

instability. v) Pseudo-isodicentric chromosome [psu idic(1)(p21)], reflecting complex chromosomal

rearrangement. vi) Additional material on chromosomes 7 and 8

[add(7)(q32),add(8)(p23)x2]. vii) Possible unidentified

material on chromosome 17 [?add(17)(q22)x2]. ix) Monosomy of chromosomes

19, 20, 21 and 22 (green arrows). xi) One to two marker chromosomes

(+1-2mar). xii) Mosaic karyotype: Four abnormal clones with complex

karyotype and 16 normal male karyotypes (46,XY), consistent with

clonal evolution. MM, multiple myeloma.](/article_images/etm/30/3/etm-30-03-12930-g00.jpg) | Figure 1Karyotype analysis revealing complex

chromosomal abnormalities in advanced MM. Conventional karyotyping

revealed multiple numerical and structural abnormalities (red

arrows) characteristic of high-risk MM: i) Hyperdiploidy with

tetraploid cells (83-85<4n>,XXY), including an additional X

chromosome. ii) Loss of Y chromosome (-Y), a common finding in

hematological malignancies. iii) High-level polysomy of chromosome

1 (+1,+1), totaling four copies, indicating aggressive disease. iv)

Dicentric chromosome [dic(1;10)(p13;q26)], suggesting genomic

instability. v) Pseudo-isodicentric chromosome [psu idic(1)(p21)], reflecting complex chromosomal

rearrangement. vi) Additional material on chromosomes 7 and 8

[add(7)(q32),add(8)(p23)x2]. vii) Possible unidentified

material on chromosome 17 [?add(17)(q22)x2]. ix) Monosomy of chromosomes

19, 20, 21 and 22 (green arrows). xi) One to two marker chromosomes

(+1-2mar). xii) Mosaic karyotype: Four abnormal clones with complex

karyotype and 16 normal male karyotypes (46,XY), consistent with

clonal evolution. MM, multiple myeloma. |

In summary, these findings collectively indicated a

high degree of chromosomal complexity and genetic instability,

typical of advanced MM (12). The

chromosomal abnormalities, including polysomy, structural

rearrangements, marker chromosomes and loss of specific

chromosomes, are associated with disease progression and a poor

prognosis.

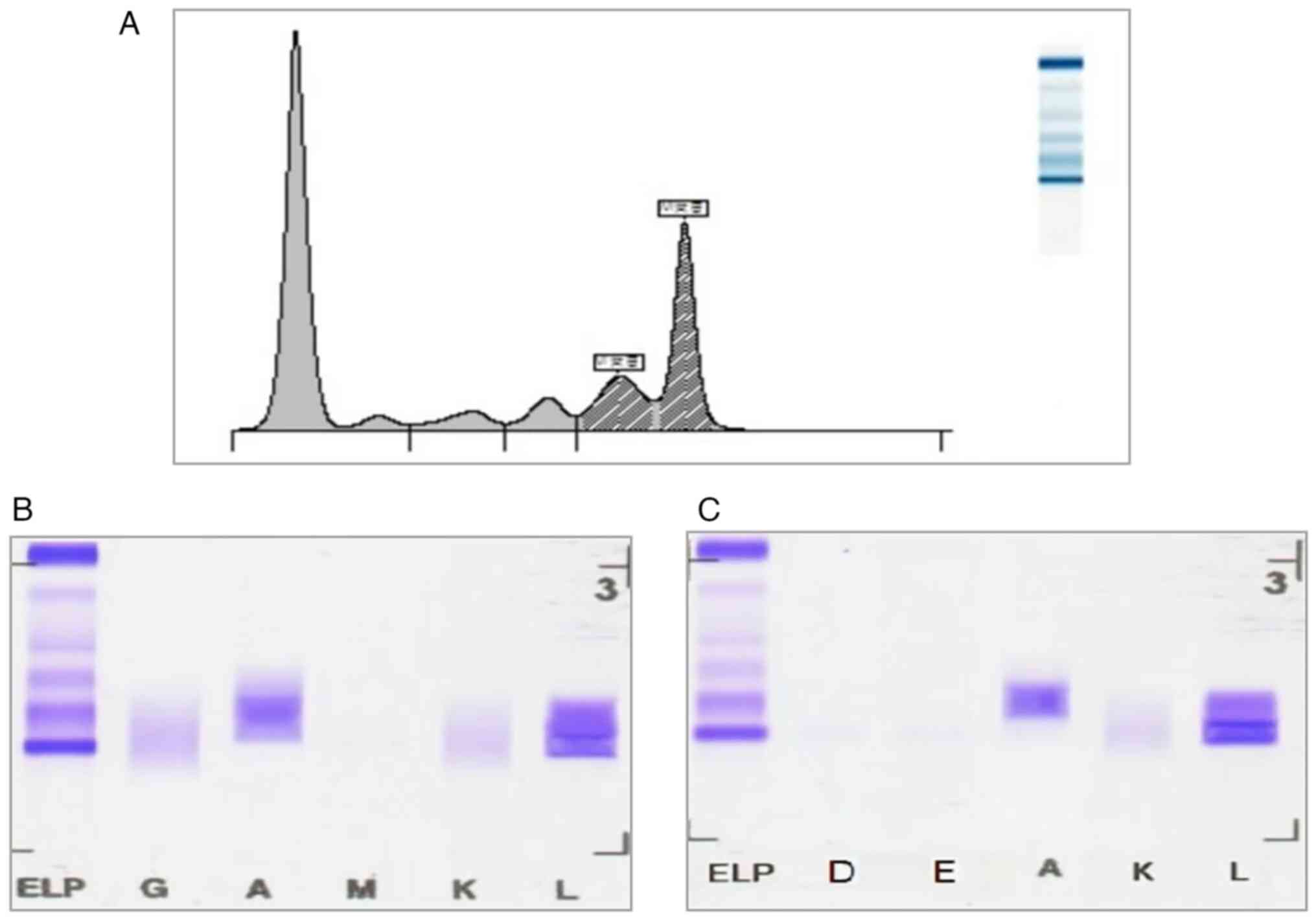

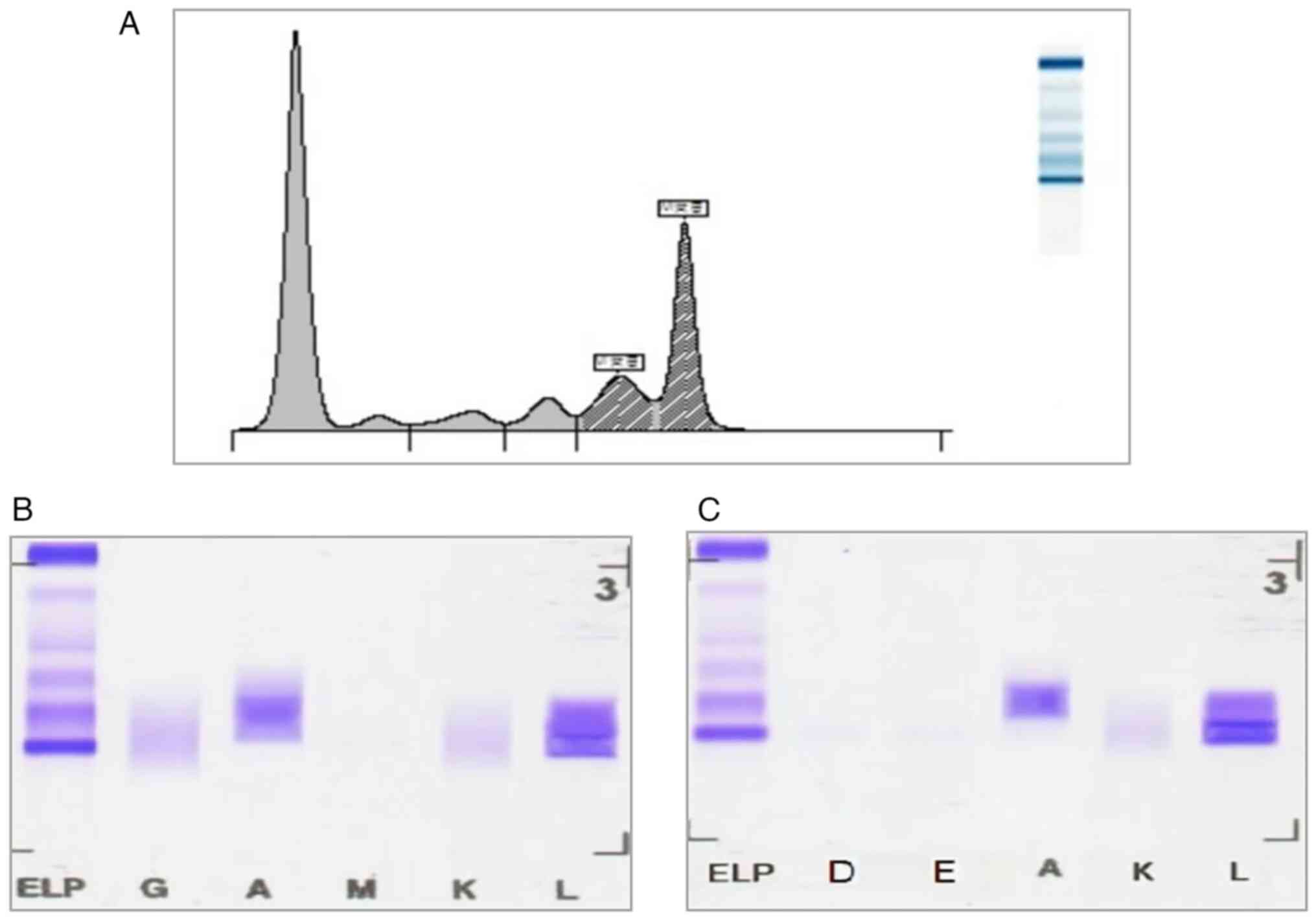

IFE analysis results. SPE revealed a

prominent M-spike in the γ region, consistent with the presence of

monoclonal protein (Fig. 2A). IFE

demonstrated specific staining for IgA and λ light chains,

confirming a monoclonal IgA λ component (Fig. 2B). A second IFE analysis was

performed on a follow-up serum sample, which consistently showed

the same IgA λ monoclonal pattern (Fig. 2C). This repeat testing served as a

confirmatory step to exclude false positivity and to strengthen

diagnostic reliability. These findings provided crucial diagnostic

evidence for the presence of monoclonal gammopathy, a hallmark

feature of MM.

| Figure 2SPE and immunofixation confirming

monoclonal gammopathy. (A) SPE demonstrating an M-spike in the γ

region. (B) Immunofixation electrophoresis revealing a monoclonal

IgA λ pattern, confirming the presence of IgA-λ type multiple

myeloma. (C) Immunofixation electrophoresis further confirming the

monoclonal IgA λ pattern. AU, arbitrary units; SPE, serum protein

electrophoresis. ELP, electrophoresis reference; G, IgG; A, IgA; M,

IgM; K, κ light chain; L, λ light chain; D, IgD; E, IgE. |

Bone marrow biopsy results. Bone marrow

biopsy revealed markedly active hematopoietic tissue proliferation,

occupying >90% of the marrow volume, with a corresponding

reduction in adipose tissue. Plasma cell hyperplasia was evident,

characterized by medium-sized cytoplasm, abundant cytosol, nuclear

eccentricity and patchy distribution. Additionally, areas of

fibrous tissue proliferation were observed, as shown by

representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the bone

marrow biopsy.

The IHC findings are summarized in Table II, and provide critical insights

into the cellular and molecular characteristics of the bone marrow

biopsy. Weak positive staining was observed for both CD3 and CD20,

indicating limited involvement of T cells (CD3) and B cells (CD20).

For CD56, patchy positive staining was noted. For CD56, patchy and

heterogeneous positive staining was noted across the biopsy sample.

CD56, a neural cell adhesion molecule, is frequently expressed in

plasma cell dyscrasias, including MM (15). The non-uniform distribution and

limited number of CD56-positive cells suggested partial expression

in this case. For CD138, patchy positive staining was also present,

confirming the presence of plasma cells. Regarding κ and λ light

chains, κ light chain staining was negative, whereas λ light chains

exhibited fragmented positive staining. This pattern indicates a

monoclonal plasma cell population with λ light chain restriction,

consistent with the diagnosis of MM. For multiple myeloma oncogene

1 (MUM-1), fragmented positive staining was detected,

characteristic of late-stage B-cell differentiation and plasma

cells, a hallmark feature in MM cases. The immunohistochemical

profile, including the expression of CD138, CD56, MUM-1 and the λ

light chain restriction, strongly supported the diagnosis of MM

with a monoclonal λ light chain profile (16).

| Table IIImmunohistochemistry findings for the

patient. |

Table II

Immunohistochemistry findings for the

patient.

| Variable | Result |

|---|

| CD3 | Weakly positive

staining |

| CD20 | Weakly positive

staining |

| CD56 | Patchy positive

staining |

| CD138 | Patchy positive

staining |

| κ light chain | Negative

staining |

| λ light chain | Fragmented positive

staining |

| Multiple myeloma

oncogene 1 | Fragmented positive

staining |

The bone marrow biopsy findings demonstrated notable

proliferation of monoclonal plasma cells, accounting for ~70% of

the marrow composition. These results are consistent with a

diagnosis of plasma cell myeloma (PCM) (17).

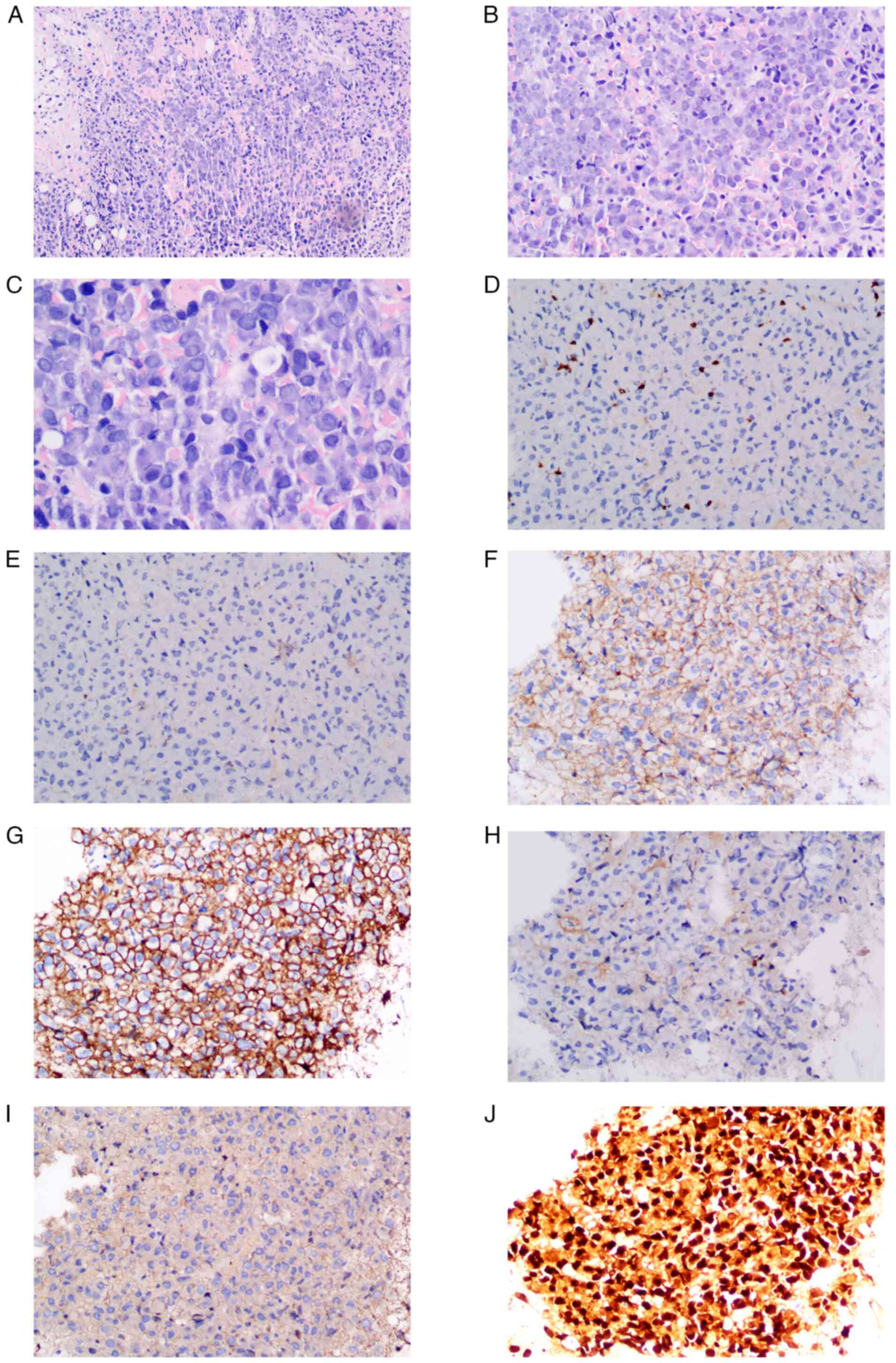

Histopathological and immunohistochemical

findings. A skin punch biopsy was obtained from the facial

keratotic papules to characterize the follicular spicules. H&E

staining revealed marked follicular plugging with compact

orthokeratosis and keratinous debris occupying dilated follicular

infundibula. The surrounding dermis exhibited mild perivascular

lymphocytic infiltration without evidence of epidermal atypia.

Congo red staining, performed on both skin and bone marrow

specimens, revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits in the dermis

and marrow. Under polarized light, these deposits exhibited classic

apple-green birefringence, confirming amyloid deposition (Fig. 3A).

To further evaluate the bone marrow biopsy, IHC

staining was conducted to identify cellular components and assess

clonality of infiltrating plasma cells. Scattered CD3-positive T

cells and CD20-positive B cells were detected, indicating minimal

lymphoid infiltration (Fig. 3B and

C). CD56 staining showed diffuse

membranous positivity (Fig. 3D),

suggesting aberrant expression in neoplastic plasma cells or

natural killer (NK) cell involvement. CD138 was diffusely and

strongly expressed on infiltrating plasma cells (Fig. 3E), confirming their plasma cell

phenotype. Light chain restriction analysis showed complete absence

of κ light chain expression (Fig.

3F) and intense diffuse positivity for λ light chains (Fig. 3G), indicating monoclonal λ light

chain restriction. MUM-1 staining demonstrated diffuse nuclear

positivity in plasma cells (Fig.

3H), supporting their plasmacytic differentiation.

Additionally, H&E staining of the bone marrow revealed diffuse

infiltration by atypical plasma cells with irregular nuclear

morphology (Fig. 3I), consistent

with plasma cell myeloma (PCM). Positive staining for amyloid

deposits in bone marrow biopsy further confirmed amyloid

deposition, with strong eosinophilic characteristics and brown

staining (Fig. 3J).

Together, the histopathological and immunophenotypic

findings from the cutaneous tissue and bone marrow biopsy confirmed

the diagnosis of systemic amyloid light-chain amyloidosis secondary

to monoclonal PCM, presenting with rare cutaneous involvement in

the form of follicular spicules (18).

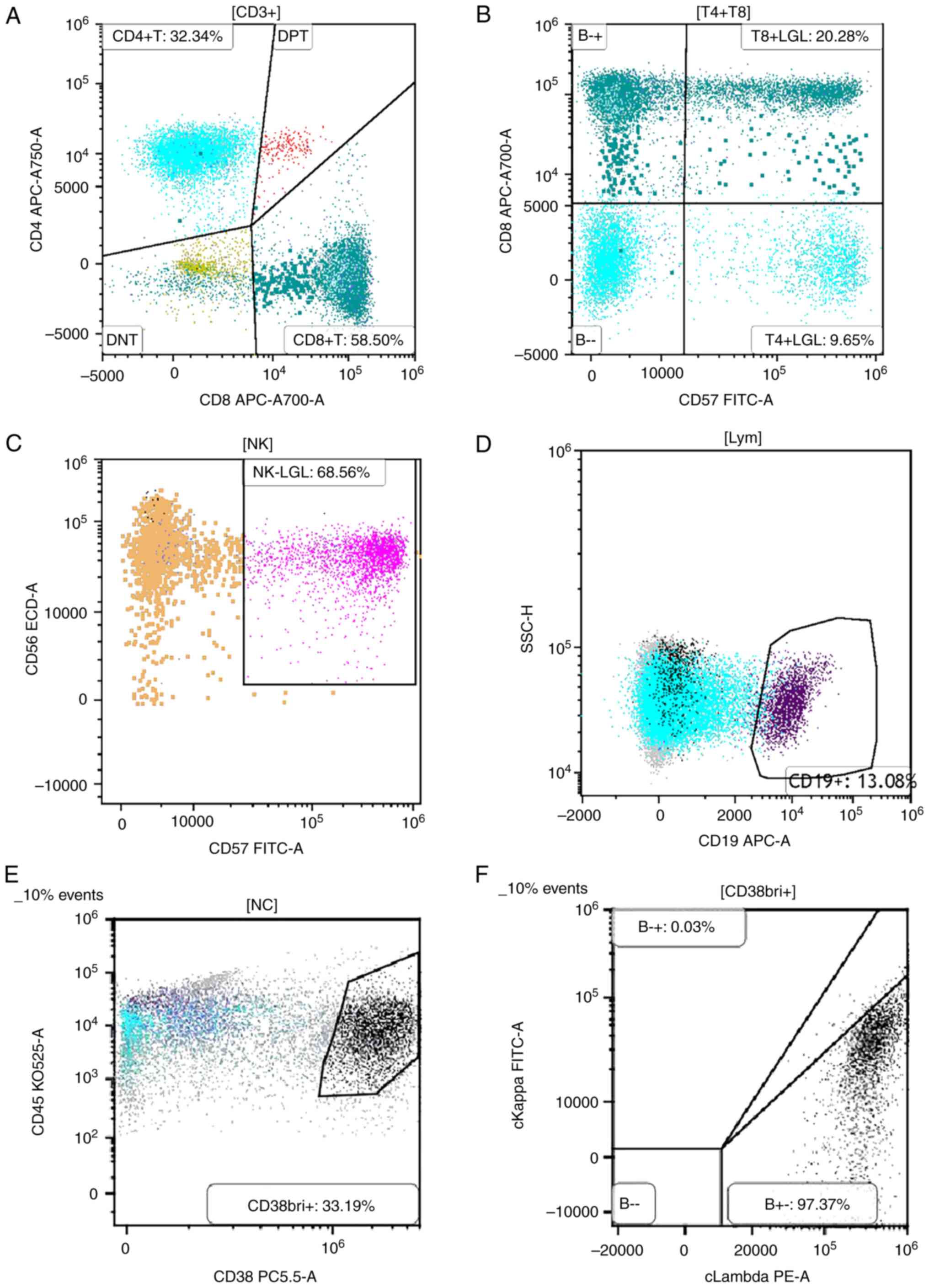

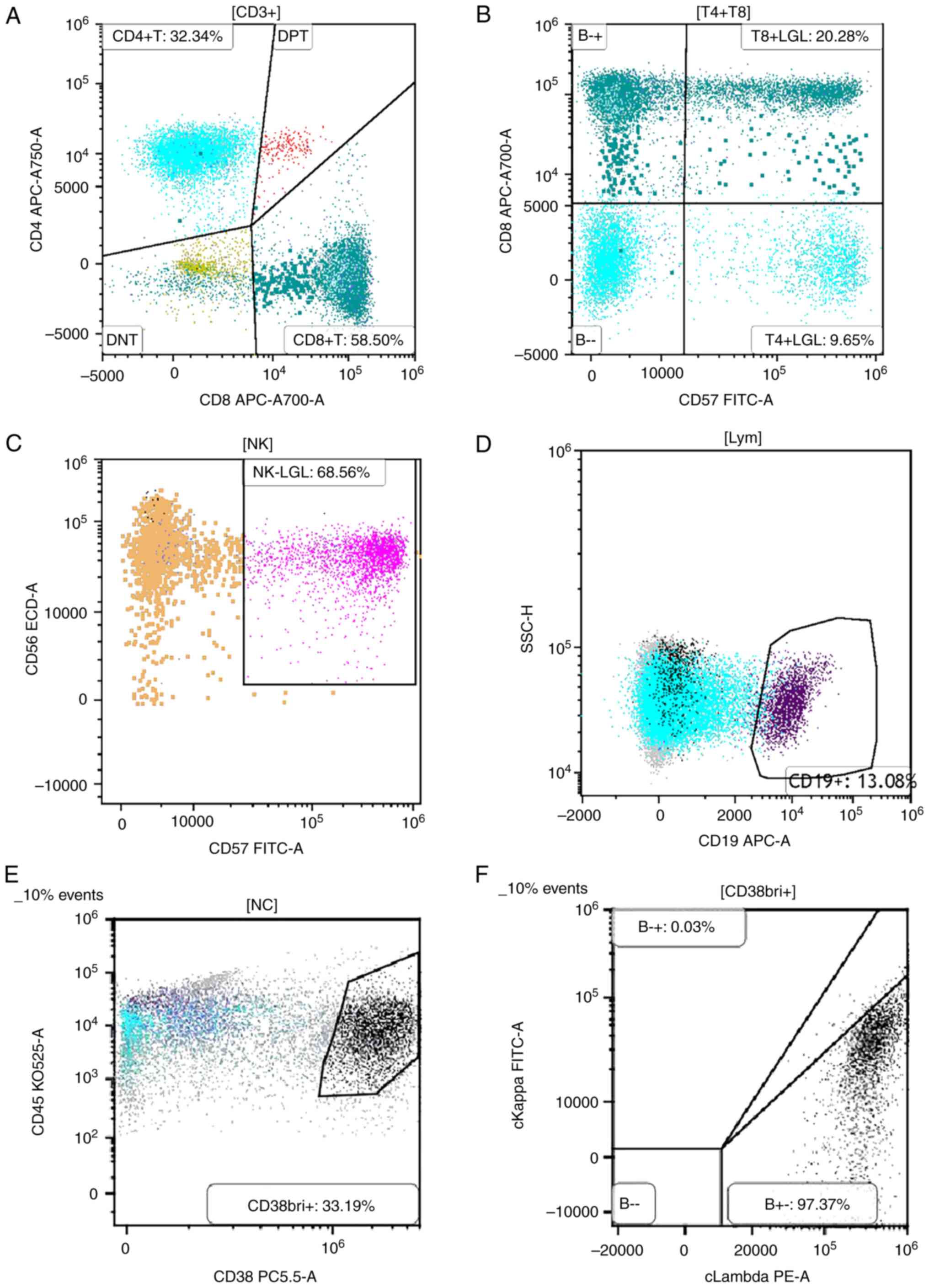

Flow cytometric immunophenotyping for hematologic

tumor classification. Multiparameter flow cytometry was

performed on fresh bone marrow aspirate samples collected in

EDTA-containing tubes to characterize the immunophenotypic profiles

of hematopoietic cell populations. Sample acquisition was conducted

on a BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Data analysis was performed using FlowJo™ software,

version 10.8.1 (BD Biosciences). Gating strategies were applied to

total nucleated cells (NCs) using CD45 and side scatter profiles.

As shown in Fig. 4A, lymphocytes

accounted for 27.76% of total NCs. The CD4/CD8 ratio was decreased,

indicating a shift in T-cell subset balance, which may reflect

immune dysregulation associated with plasma cell disorders.

CD57+ large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) were detected

within the normal reference range (2-15% of total lymphocytes)

(Fig. 4B and C), suggesting no evidence of LGL

expansion or chronic LGL leukemia. CD19+ B lymphocytes

constituted 13.08% of the lymphocyte population, with normal

distributions of precursor and mature subsets, indicating no

disruption in B-cell maturation. Notably, a substantial expansion

of plasma cells was observed (Fig.

4D). As shown in Fig. 4E,

gating on CD38 and CD45 expression revealed a distinct

CD38bright+(CD38bri+) population, accounting

for 33.19% of total NCs. These cells exhibited low CD45 expression

and high CD38 expression, a typical immunophenotypic hallmark of

malignant plasma cells. The markedly increased proportion of

CD38bri+ cells indicated significant plasma cell

infiltration within the bone marrow.

| Figure 4Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of

bone marrow cells from a patient with PCM. (A) Lymphocyte analysis

showing a decreased CD4/CD8 ratio. (B and C) Quantification of

CD57⁺ LGLs, demonstrating a normal proportion of this subset. (D)

Marked expansion of plasma cells detected within the bone marrow

aspirate. (E) Dual-parameter plot of CD38 and CD45 expression

revealing a distinct CD38bright+/CD45dim+

population, accounting for 33.19% of total nucleated cells,

consistent with malignant plasma cell infiltration. (F)

Intracellular immunoglobulin light chain staining within the

CD38bright+ population indicating prominent λ light

chain restriction (97.37%) with minimal κ expression (0.03%),

confirming clonal proliferation and supporting the diagnosis of

PCM. LGLs, large granular lymphocytes; NC, nucleated cell; PCM,

plasma cell myeloma; A, allophycocyanin-Alexa Fluor 700; APC,

allophycocyanin; CD38bri+, CD38 bright positive; DNT,

double negative T cells; DPT, dual-parameter plot; ECD,

energy-coupled dye; H, height parameter; KO525, Krome Orange 525;

Lym, lymphocytes; NK, natural killer cells; PC5.5,

phycoerythrin-cyanine 5.5; PE, phycoerythrin; SSC, side

scatter. |

Further immunophenotypic analysis of the

CD38bri+ gated population was conducted to assess light

chain restriction. As demonstrated in Fig. 4F, intracellular staining for

cytoplasmic immunoglobulin light chains revealed predominant

expression of λ light chains in 97.37% of the gated plasma cells,

with minimal κ expression (0.03%). This pronounced λ light chain

restriction confirms the presence of a clonal plasma cell

population and supports the diagnosis of PCM. Collectively, these

flow cytometry findings demonstrated substantial clonal

proliferation of λ-restricted malignant plasma cells within the

bone marrow, consistent with a diagnosis of MM.

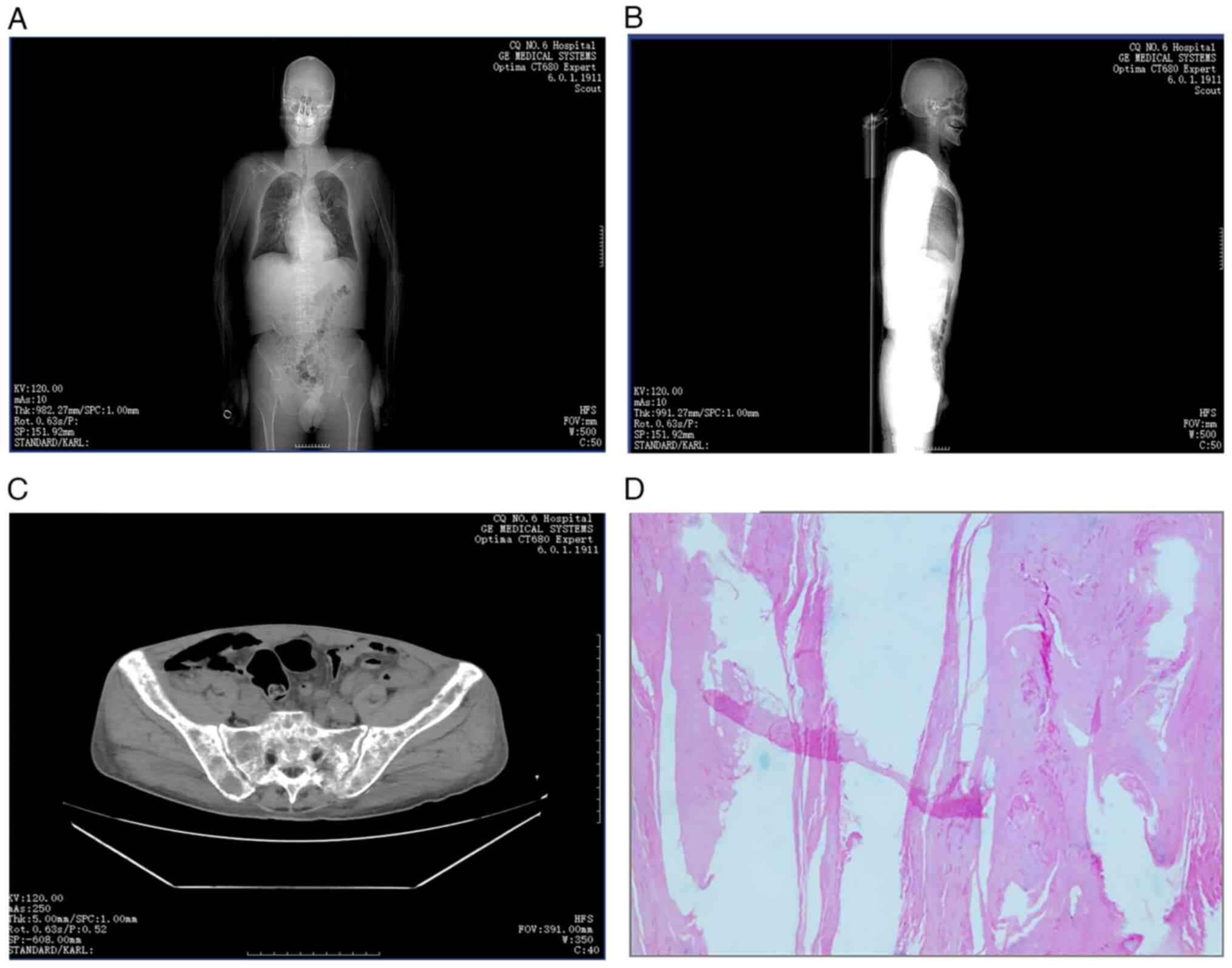

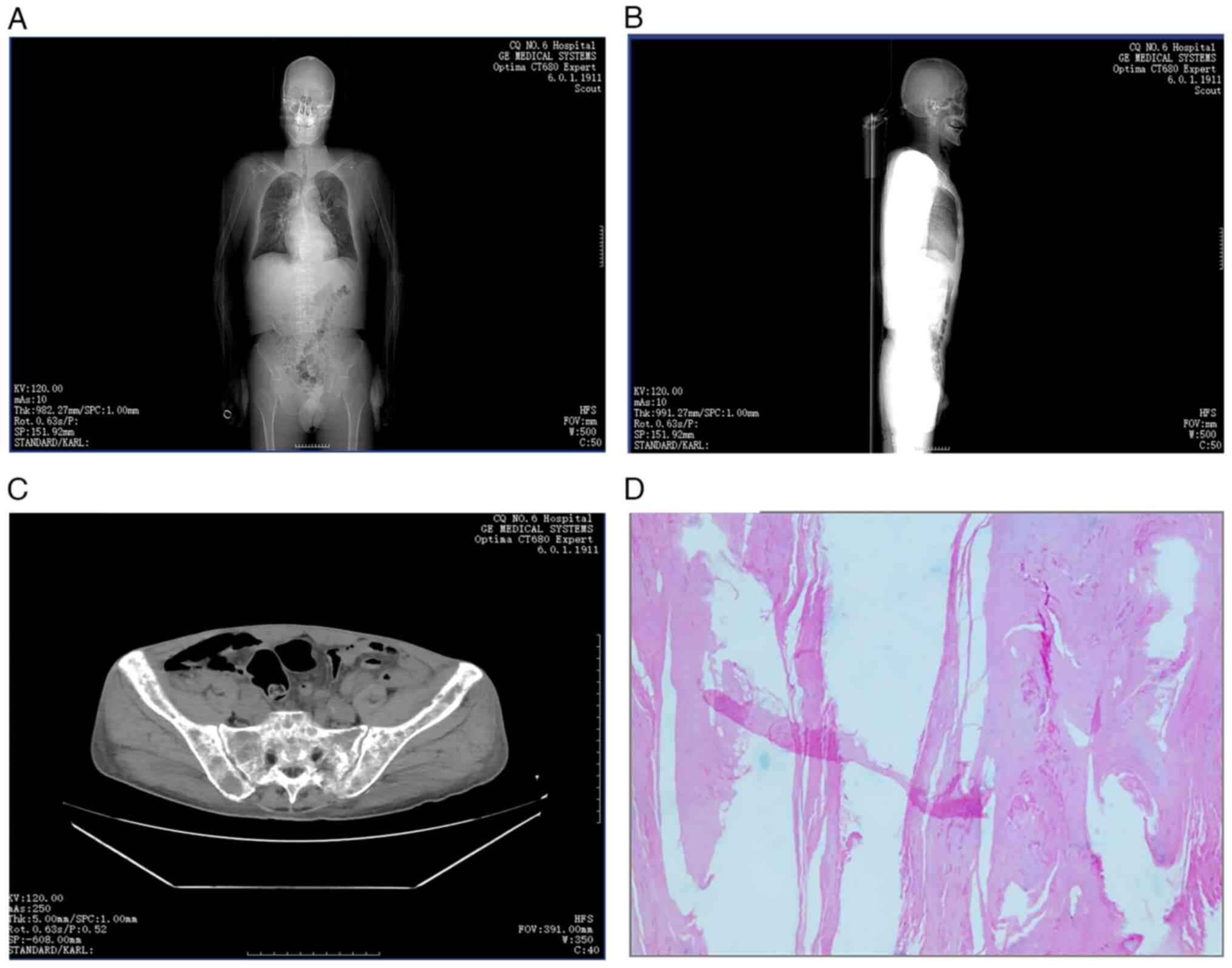

Imaging and histopathological findings. A

thorough imaging evaluation was conducted, including CT scans of

the pelvis, cervical spine and head. The key findings are

summarized as follows: i) Cranial findings, head CT revealed no

abnormalities in the brain parenchyma. Sinus findings revealed

evidence of bilateral maxillary and ethmoid sinusitis. ii) Skeletal

lesions, multiple hypodense lesions were identified in the skull,

several vertebrae, bilateral ribs, scapulae and pelvic bones, which

are findings consistent with lytic lesions of MM. iii) Fractures

and spinal changes, bilateral pathological rib fractures,

compression of the T12 vertebral body and a suspected

intravertebral lesion in T1 were observed, along with degenerative

changes in the spine. iv) Pulmonary findings, bilateral lung

infections, pleural thickening and small bilateral pleural

effusions were evident (Fig.

5A-C). v) Renal findings, CT revealed small calculi in the

right kidney. vi) Abdominal findings, increased soft tissue density

surrounding the abdominal aorta was detected. vii) Pelvic findings,

small pelvic effusions were observed. viii) Histopathological

findings, dermatopathological analysis revealed squamous epithelium

with areas of hyperkeratosis (Fig.

5D). Furthermore, Fig. 6

presents a detailed histopathological view, showing an area of

extensive infiltration of malignant plasma cells in the dermal

layer, consistent with cutaneous involvement in MM. These findings

collectively indicated advanced MM with extensive skeletal

involvement and associated systemic complications.

| Figure 5Comprehensive imaging and

histopathological evaluation. (A) An anterior scout image from CT

demonstrated diffuse skeletal involvement, including multiple

hypodense lesions in the skull, ribs, spine, scapulae and pelvis,

consistent with lytic lesions seen in multiple myeloma. Bilateral

pulmonary infections and pleural thickening were also visible. (B)

A lateral scout image further illustrated spinal abnormalities,

including compression of the T12 vertebral body and suspected

Hsu-Mo nodule at T1, as well as degenerative spinal changes. (C) An

axial pelvic CT revealed lytic bone lesions, bilateral pathological

rib fractures and pelvic effusion. (D) Histopathological

examination of a skin lesion showed squamous epithelium with marked

hyperkeratosis (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original

magnification, x100), supporting dermatopathological

involvement. |

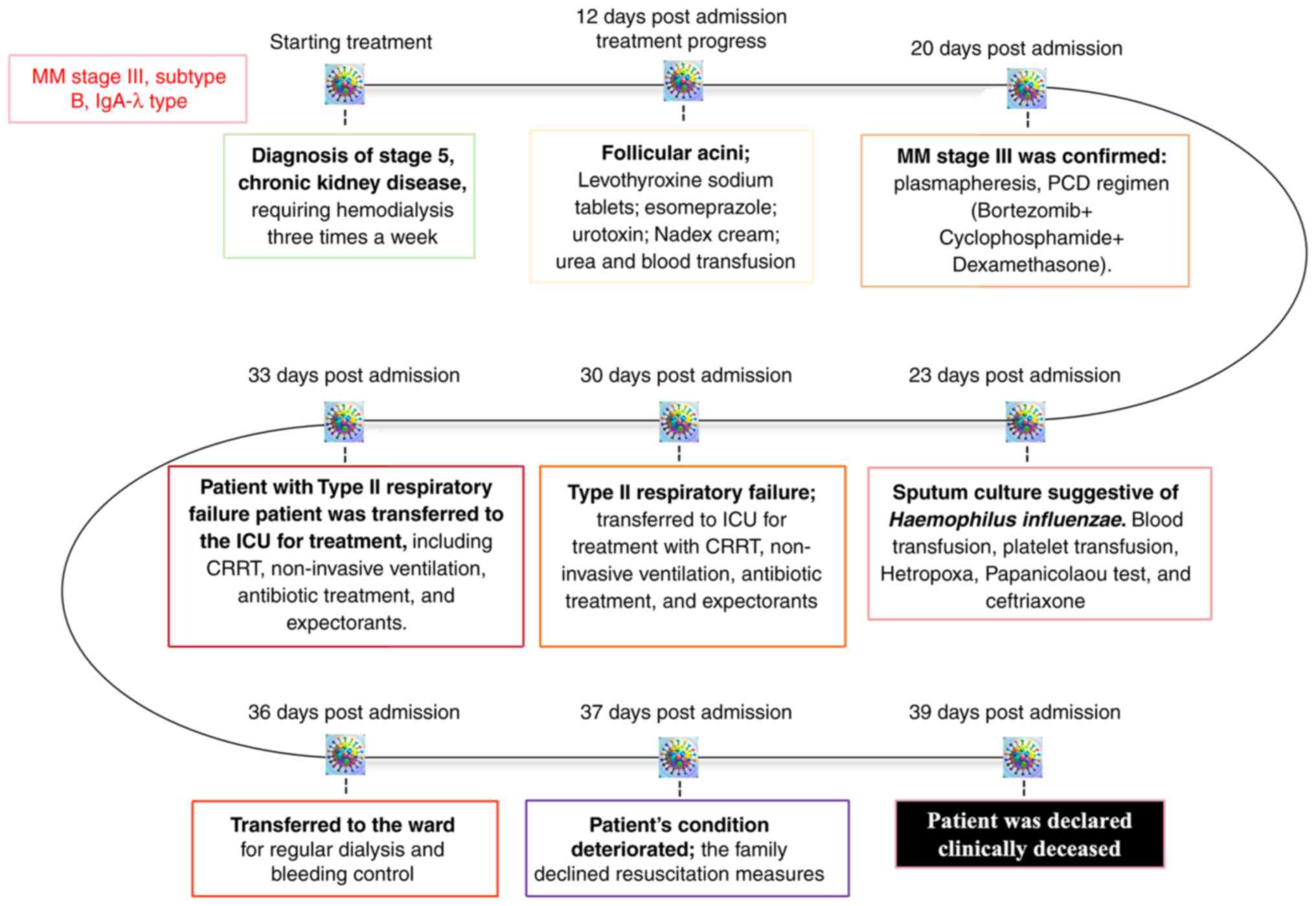

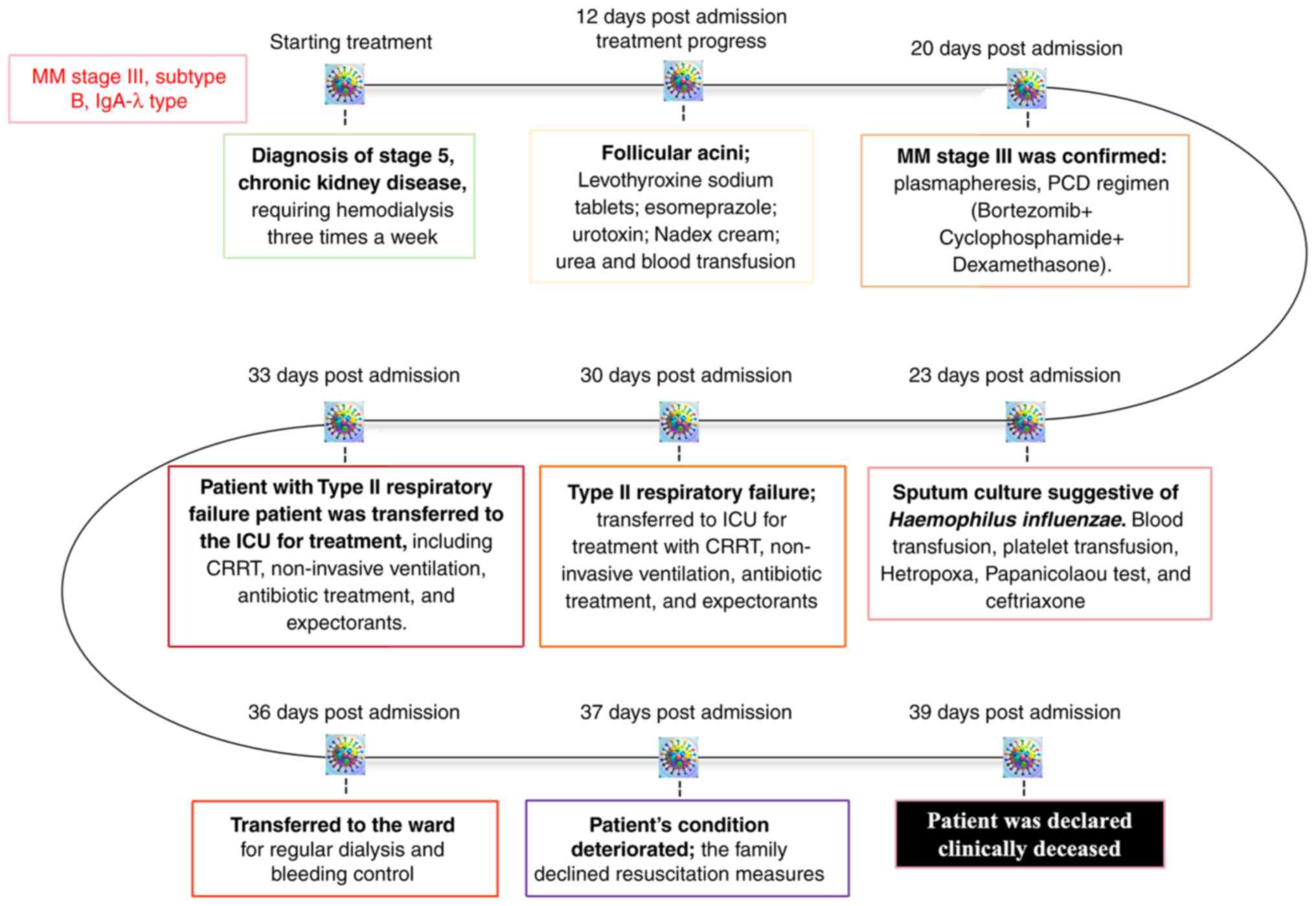

Treatment timeline and clinical

course. Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with MM, stage III,

subtype B, IgA-λ type in February 2024. Concomitantly, the patient

had stage 5 CKD, for which maintenance hemodialysis (three sessions

per week) was initiated as supportive therapy.

Disease progression and therapeutic

interventions. The clinical course and major therapeutic

milestones are summarized in Fig.

7. The condition of the patient exhibited episodic

deterioration with corresponding escalation in supportive care.

Notably, data from March 2024 revealed critical insights into

disease progression.

| Figure 7Timeline of clinical course and

interventions in a patient with IgA-λ type MM. The patient was

diagnosed with stage III MM (subtype B, IgA-λ type) and regular

hemodialysis was initiated. In March 2024, follicular acanthosis

was noted; treatment included levothyroxine, esomeprazole,

urotropine, urea cream, nadifloxacin cream and blood transfusion.

In April 2024, the patient developed type II expiratory failure and

was admitted to the ICU for CRRT, non-invasive ventilator support,

and symptomatic management. Despite intensive care, the patient

succumbed to disease-related complications. CRRT, continuous renal

replacement therapy; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; MM, multiple

myeloma. |

i) 12 days post-admission: The patient was

prescribed a supportive pharmacological regimen, which included the

following treatments: i) Levothyroxine sodium (50 µg, oral, daily)

to treat hypothyroidism, which was diagnosed based on thyroid

function tests; ii) esomeprazole (40 mg, oral, daily), prescribed

for gastroesophageal reflux disease and to prevent gastric ulcers,

a common side effect of other medications used in the patient's

treatment.; iii) urotoxin (5 ml, topical, applied twice daily) to

treat localized urinary tract infection symptoms, primarily urinary

discomfort; iv) Nadex cream (1% strength, topical, applied twice

daily), applied to manage dermatological symptoms related to skin

irritation and hyperkeratosis associated with the patient's

condition; v) urea preparations (10%, topical, applied as needed),

for moisturizing and treating dry, flaky skin, a complication

arising from systemic treatment and disease progression; and vi)

blood transfusions (two units of packed red blood cells,

intravenous infusion) administered for symptomatic anemia, which

was necessary due to the patient's worsening hematological

parameters. These treatments were provided in conjunction with

ongoing monitoring and adjustments to the supportive care plan

based on the patient's clinical response.

ii) 20 days post-admission: The patient presented

with cutaneous manifestations characterized by the emergence of

follicular spicules, suggestive of a dermatological response

possibly associated with the underlying hematological or renal

pathology. The patient received the same treatment as

aforementioned, namely, levothyroxine sodium tablets (for

hypothyroidism), esomeprazole (proton pump inhibitor for gastric

protection), urotoxin (for renal support), nadex cream (for

dermatological lesions) and urea cream (for skin hydration). In

addition, blood transfusion was provided to address persistent

anemia.

iii) 23 days post-admission: Microbiological testing

was conducted on a sputum sample using standard bacteriological

culture techniques. The specimen was cultured on chocolate agar and

incubated under 5% CO2 at 37˚C for 24-48 h. Bacterial

identification was performed using Gram staining and confirmed with

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass

spectrometry. Haemophilus influenzae was isolated,

indicating a lower respiratory tract infection. The patient was

treated with ceftriaxone (2 g/day, intravenous infusion, for 5

days) targeting the identified pathogen. Blood and platelet

transfusions were also administered to manage anemia and

thrombocytopenia. Additionally, a sputum cytology specimen was

processed and stained using Hetropoxa-Papanicolaou staining was

performed at room temperature (20-25˚C) for 15 min for cytological

evaluation. The result revealed numerous neutrophils and

degenerating epithelial cells, consistent with an active infectious

process.

iv) 30 to 33 days post-admission: The patient

developed type II respiratory failure, characterized by hypercapnia

and hypoxemia, necessitating transfer to the Intensive Care Unit.

Treatment included continuous renal replacement therapy for

metabolic stabilization, and non-invasive mechanical ventilation

(BiPAP mode, FiO2 40-60%) to support respiratory

function. Pharmacological management comprised of the following: i)

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, including piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5

g IV every 8 h) to empirically cover gram-negative and anaerobic

pathogens pending culture results; ii) moxifloxacin (400 mg IV once

daily) to provide additional coverage for atypical respiratory

organisms; and iii) mucolytic therapy, including acetylcysteine

(600 mg oral, three times daily), to reduce mucus viscosity and

improve airway clearance. Despite these interventions, the

patient's respiratory compromise persisted, with ongoing oxygen

dependence and elevated arterial CO2 levels, indicating

progressive ventilatory failure.

v) 36 days post admission: Following partial

stabilization, the patient was transferred back to the general

ward, and continued on regular hemodialysis and received care for

recurrent bleeding episodes.

vi) 37 days post admission: The clinical status of

the patient deteriorated again. After a discussion with the family,

a do-not-resuscitate order was established and aggressive

life-sustaining interventions were withheld.

vii) 39 days post admission: The patient was

pronounced clinically deceased.

Discussion

The diagnosis of FSMM necessitates the exclusion of

other dermatoses that can present with similar follicular

hyperkeratotic features. Conditions such as vitamin A deficiency

may lead to follicular hyperkeratosis, but they are often

accompanied by xerosis and ocular findings such as Bitot's spots

(19). In the present case, the

serum vitamin A levels of the patient were normal and no ocular

signs were present. HIV-associated follicular hyperkeratosis,

particularly in cases of advanced immunosuppression, can clinically

mimic FSMM; however, the patient tested negative for HIV via both

serological and molecular methods, and exhibited no signs of

immunodeficiency (20,21).

Skin manifestations related to chronic renal

failure, such as prurigo nodularis and perforating dermatoses, may

involve follicular lesions; however, these lack the distinct

histopathological characteristics of FSMM, including

intrafollicular monoclonal protein deposition (22). Additionally, disorders such as

acanthosis nigricans and lichen spinulosus can present with spiny

papules but do not exhibit the immunoglobulin deposition typical of

FSMM (23). Thus, the definitive

diagnosis in the present case was supported by the presence of

monoclonal immunoglobulin λ light chain deposition in the

follicular epithelium, along with plasma cell-rich dermal

infiltrates, consistent with the known PCM of the patient.

The pathophysiology of FSMM remains incompletely

understood. Current evidence suggests that monoclonal

immunoglobulins, particularly light chains secreted by clonal

plasma cells, are deposited within follicular structures, leading

to epithelial disruption and reactive hyperkeratosis. These

deposits may also undergo conformational changes, promoting

amyloidogenesis and contributing to the formation of follicular

spicules (24,25).

Notably, not all patients with MM develop FSMM.

According to a previous study, follicular spicules associated with

FSMM occur in <1% of patients with MM, highlighting its rarity

and the likelihood that additional host or environmental factors,

such as serum paraprotein concentration, the structural properties

of light chains or the local skin microenvironment, may influence

susceptibility (26). In the

current case, skin biopsy revealed follicular hyperkeratosis with

prominent λ light chain deposition, consistent with this

hypothesized mechanism. The absence of cryoglobulinemia was

confirmed by both negative cryoglobulin screening in serum at 4˚C

and a lack of clinical symptoms typically associated with

cryoglobulinemia, indicating that cold-precipitable immunoglobulins

are not essential for FSMM development.

In the present case report, the comorbid end-stage

CKD and long-term hemodialysis introduced additional diagnostic

complexity. CKD is associated with a broad spectrum of

dermatological manifestations, including uremic pruritus,

perforating dermatoses and calciphylaxis. However, these

CKD-related dermatoses differ significantly from FSMM in both

clinical manifestations and histopathological features (27).

Calciphylaxis typically manifests with painful,

ulcerative lesions in areas of adiposity and vascular

calcification, whereas uremic pruritus lacks follicular-based

histological findings. Notably, monoclonal immunoglobulin

deposition is rarely observed in CKD-related dermatoses (28). Therefore, the presence of

immunoglobulin light chains within follicular structures in the

present case strongly supports the diagnosis of FSMM over other

CKD-related skin disorders (29).

The present case illustrates the clinical value of

recognizing FSMM as a cutaneous marker of plasma cell dyscrasia.

FSMM may precede systemic symptoms, serve as a sign of disease

relapse or reflect a poor prognosis. Recognition of its

characteristic morphology, together with timely histological and

immunofluorescence evaluation, can enable early diagnosis and guide

therapeutic decisions.

Novel learning points from the present case include:

i) FSMM may occur independently of cryoglobulinemia, challenging

earlier assumptions (30); ii)

immunoglobulin light chain deposition can be a key distinguishing

factor in patients with comorbid renal disease; and iii) FSMM

serves as a potential non-invasive biomarker for disease activity

in MM. Had the condition of the patient stabilized, long-term

management could have included systemic anti-myeloma therapy

adapted for renal impairment, topical keratolytics or retinoids for

symptom control, and regular dermatological monitoring to assess

treatment response. Nutritional support and optimization of

dialysis care may also contribute to maintaining skin integrity

(31).

In conclusion, FSMM should be considered in patients

with unexplained follicular hyperkeratosis and suspected or

confirmed plasma cell neoplasms. Dermatological manifestations in

such patients warrant thorough evaluation, including biopsy and

immunoglobulin profiling. Further research is needed to clarify the

mechanisms underlying FSMM, and to establish standardized

diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere

gratitude to the late Dr Junling Tang (Department of Occupational

Disease and Poisoning Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of

Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College, Chongqing, China) for

their early involvement in the clinical evaluation and patient

management in this case. These contributions laid the foundation

for the development of this report. The authors would also like to

thank Mr. Zhenjun Xi and Ms. Qianqian Liu (Department of

Occupational Disease and Poisoning Medicine, The First Affiliated

Hospital of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College,

Chongqing, China) for their invaluable contributions to the data

collection and experimental process; their meticulous efforts

ensured the accuracy and reliability of our research findings.

Additionally, the authors are grateful to Mrs. Li Yan and Mr. Lvsu

Ye (Department of Occupational Disease and Poisoning Medicine, The

First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical

College, Chongqing, China) for their assistance in data analysis

and interpretation, which greatly enhanced the depth and quality of

the research outcomes.

Funding

Funding: The authors declare that financial support was received

for the research, authorship and publication of this article. The

work was funded by the Chongqing Medical Scientific Research

Project (Joint Project of Chongqing Health Commission and Science

and Technology Bureau) (grant nos. 2023GGXM006, 2024ZDXM026 and

2024ZDXM026), the Key Research Project from Chongqing Medical and

Pharmaceutical Vocational Education Group (grant no. CQZJ202329),

the Chongqing Key Municipal Public Health Specialty Construction

Project, 2024 Scientific Research Project of Chongqing Medical and

Pharmaceutical College (grant no. ygzrc2024101), the Chongqing

Education Commission Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

KJQN202402821), the Chongqing Shapingba District Science and

Technology Bureau Project (grant no. 2024071), the 2024 Chongqing

Medical and Pharmaceutical College Innovation Research Group

Project (grant no. ygz2024401), and the Chongqing Science and

Health Joint Medical Research Project (grant no.

2024SQKWLHMS051).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XiL and XuL designed the study and coordinated the

clinical evaluation. QinL, QiaL and XuL participated in the

diagnosis and treatment of the patient. XiL, QiaL and QinL were

responsible for data collection, clinical interpretation and

histological assessments. YL, LZ and LW contributed to the analysis

and interpretation of the laboratory and imaging data, and

supervised the study. All authors participated in the writing of

the original draft and figure preparation. YL, LZ and LW critically

reviewed and revised the manuscript. XiL and YL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of clinical details and any

accompanying images. The patient was fully informed about the

purpose of the publication and explicitly consented to the use of

facial photographs and other potentially identifiable data. The

consent included acknowledgment that the images may be published in

scientific journals and disseminated online in an academic context.

Efforts have been made to ensure patient anonymity where possible,

while recognizing that complete anonymity cannot be guaranteed in

cases involving facial features.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rudnicka L, Chrostowska S, Kamiński M,

Waśkiel-Burnat A, Michalczyk A, Rakowska A and Olszewska M: The

role of trichoscopy beyond hair and scalp diseases. A review. J Eur

Acad Dermatol Venereol: Mar 15, 2023 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

2

|

Michael A, Fuller T, Brogan S and Murphy

MC: An intrathecal pump misadventure in two acts: An unrecognized

partial pocket fill followed by an unusual withdrawal syndrome two

months later. J Palliat Med: Jan 30, 2025 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

3

|

Chang YC, Peng CY, Chi KY, Song J, Chang Y

and Chiang CH, Gao W and Chiang CH: Cardiovascular outcomes and

mortality in diabetic multiple myeloma patients initiated on

proteasome inhibitors according to prior use of glucagon-like

peptide 1 agonists. Eur J Prev Cardiol: Jan 29, 2025 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

4

|

Jia J, Yin J, Geng C and Liu A:

Characteristics and outcomes of secondary acute lymphoblastic

leukemia (sALL) after multiple myeloma (MM): SEER data analysis in

a single-center institution. Cancer Pathog Ther. 3:76–80.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rapparini L, Pileri A, Robuffo S,

Agostinelli C and La Placa M: Cutaneous involvement in multiple

myeloma. A rare entity. Clin Case Rep. 13(e9476)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Růžičková T, Vlachová M, Pečinka L,

Brychtová M, Večeřa M, Radová L and Ševčíková S, Jarošová M, Havel

J, Pour L and Ševčíková S: Detection of early relapse in multiple

myeloma patients. Cell Div. 20(4)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yang J, Hu Q, Lu J, Wang J, Wu D, Fei X,

Wang L, Yu X and Tang Y: DRESS is not a rare complication during

the initial treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: The

experience of two medical institutes. Acta Haematol: Jan 27, 2025

(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

8

|

Wildes TM: First relapse in older adults

with multiple myeloma: Creating new pathways in uncharted

territory. Br J Haematol. 206:1523–1525. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xue W, Li Y, Ma Y and Zhang F:

GDF15-mediated enhancement of the Warburg effect sustains multiple

myeloma growth via TGFβ signaling pathway. Cancer Metab.

13(3)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sampath VS: Isatuximab-based therapy for

multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 392:518–519. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Oymanns M, Baltaci M, Bellm A and Assaf C:

Paraneoplastic filiform hyperkeratosis and

immunoglobulin-associated vasculitis in myeloma progression: A case

report. Case Rep Dermatol. 13:563–567. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang Y, Cao J, Gu W, Shi M, Lan J, Yan Z,

Jin L, Xia J, Ma S, Liu Y, et al: Long-term follow-up of

combination of B-cell maturation antigen and CD19 chimeric antigen

receptor T cells in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 40:2246–2256.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Mettias S, ElSayed A, Moore J and Berenson

JR: Multiple myeloma: Improved outcomes resulting from a rapidly

expanding number of therapeutic options. Target Oncol. 20:247–267.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Liehr T: International system for human

cytogenetic or cytogenomic nomenclature (ISCN): Some thoughts.

Cytogenet Genome Res. 161:223–224. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Giorgetti G, Maroto-Martin E, Soncini D,

Fenoglio D, Becherini P, Benzi A, Ravera S, Traverso I, Ladisa F,

Lai F, et al: CD56 expression modulates NAD+ metabolic landscape

and predicts sensitivity to anti-CD38 therapies in multiple

myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 15(83)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

L B Andrade C, Ferreira MV, M Alencar B, S

B Filho JL, A Guimaraes M, Porto Cruz Moraes I, S Lopes TJ, S Dos

Santos A, M Dos Santos M, C S E Silva MI, et al: PCMMD: A novel

dataset of plasma cells to support the diagnosis of multiple

myeloma. Sci Data. 12(161)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Penfield JG: Multiple myeloma in end-stage

renal disease. Semin Dial. 19:329–334. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bou Zerdan M, Nasr L, Khalid F, Allam S,

Bouferraa Y, Batool S, Tayyeb M, Adroja S, Mammadii M, Anwer F, et

al: Systemic AL amyloidosis: current approach and future direction.

Oncotarget. 14:384–394. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jhaveri KD, Meena P, Bharati J and Bathini

S: Recent updates in the diagnosis and management of kidney

diseases in multiple myeloma. Indian J Nephrol. 35:8–20.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Utsu Y, Isono Y, Masuda SI, Arai H,

Shimoji S, Matsumoto R, Tsushima T, Tanaka K, Matsuo K, Kimeda C,

et al: Time-dependent recovery of renal impairment in patients with

newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 104:573–579.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Dhakal B, Hari P, Chhabra S, Szabo A, Lum

LG, Glass DD, Park JH, Donato M, Siegel DS, Felizardo TC and Fowler

DH: Rapamycin-resistant polyclonal Th1/Tc1 cell therapy (RAPA-201)

safely induces disease remissions in relapsed, refractory multiple

myeloma. J Immunother Cancer. 13(e010649)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Abdi J and Redegeld F: Toll-like receptor

1/2 activation reduces immunoglobulin free light chain production

by multiple myeloma cells in the context of bone marrow stromal

cells and fibronectin. PLoS One. 20(e0310395)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Martins Rodrigues F, Jasielec J, Perpich

M, Kim A, Moma L, Li Y, Storrs E, Wendl MC, Jayasinghe RG, Fiala M,

et al: Germline predisposition in multiple myeloma. iScience.

28(111620)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yoon IC, Do N, Vazquez T, Elder DE, Steele

KT and Rosenbach M: Injection site reaction to teclistamab in a

patient with multiple myeloma. JAAD Case Rep. 56:48–50.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jimeno Sandoval JC, Cantatore M, Meakin L,

Menghini T, Owen L, Doran I, Erskine M and Rossanese M: Treatment,

prognosis, and outcome of dogs treated for rectal plasmacytoma: A

multicentric retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 263:1–8.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Fotiou D and Katodritou E: From biology to

clinical practice: The bone marrow microenvironment in multiple

myeloma. J Clin Med. 14(327)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Li Y, Kuang L, Huang B, Liu J, Chen M, Li

X, Gu J, Yu T and Li J: Early identification of the

non-transplanted functional high-risk multiple myeloma: Insights

from a predictive nomogram. Biomedicines. 13(145)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bahrani E, Perkins IU and North JP:

Diagnosing calciphylaxis: A review with emphasis on histopathology.

Am J Dermatopathol. 42:471–480. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhou Y, Chen Y, Yin G and Xie Q:

Calciphylaxis and its co-occurrence with connective tissue

diseases. Int Wound J. 20:1316–1327. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hosler GA, Weibel L and Wang RC: The cause

of follicular spicules in multiple myeloma. JAMA Dermatol.

151:457–458. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Satta R, Casu G, Dore F, Longinotti M and

Cottoni F: Follicular spicules and multiple ulcers: Cutaneous

manifestations of multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 49:736–740.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

![Karyotype analysis revealing complex

chromosomal abnormalities in advanced MM. Conventional karyotyping

revealed multiple numerical and structural abnormalities (red

arrows) characteristic of high-risk MM: i) Hyperdiploidy with

tetraploid cells (83-85<4n>,XXY), including an additional X

chromosome. ii) Loss of Y chromosome (-Y), a common finding in

hematological malignancies. iii) High-level polysomy of chromosome

1 (+1,+1), totaling four copies, indicating aggressive disease. iv)

Dicentric chromosome [dic(1;10)(p13;q26)], suggesting genomic

instability. v) Pseudo-isodicentric chromosome [psu idic(1)(p21)], reflecting complex chromosomal

rearrangement. vi) Additional material on chromosomes 7 and 8

[add(7)(q32),add(8)(p23)x2]. vii) Possible unidentified

material on chromosome 17 [?add(17)(q22)x2]. ix) Monosomy of chromosomes

19, 20, 21 and 22 (green arrows). xi) One to two marker chromosomes

(+1-2mar). xii) Mosaic karyotype: Four abnormal clones with complex

karyotype and 16 normal male karyotypes (46,XY), consistent with

clonal evolution. MM, multiple myeloma.](/article_images/etm/30/3/etm-30-03-12930-g00.jpg)