Introduction

Stroke is a devastating neurological condition that

is one of the leading causes of long-term disability worldwide,

imposing substantial physical, emotional, and socioeconomic burdens

on survivors and their families (1). Despite significant advancements in

acute stroke care, which have contributed to reducing mortality

rates, the management of chronic stroke remains a critical and

unresolved challenge in clinical practice (1-3).

Historically, the prevailing assumption that functional recovery

plateaus within the first few months post-stroke has limited the

focus on rehabilitation efforts to the acute and subacute phases

(4). However, emerging evidence

challenges this notion by demonstrating that targeted

rehabilitation interventions can yield meaningful improvements in

functional outcomes even during the chronic phase of stroke

recovery (5,6). This potential paradigm shift

underscores the need for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms

underlying chronic stroke recovery and the development of

innovative therapeutic strategies to address the persistent unmet

needs of this patient population (7).

The triage process in stroke rehabilitation is

crucial for balancing patient outcomes and cost control (5). It involves screening patients,

establishing assessment criteria and considering stroke severity to

determine appropriate care settings (8). Although significant progress has been

made in acute stroke care, disparities remain during the later

phases of recovery (9). It has

been suggested that severely affected patients with stroke can have

the potential for benefiting from rehabilitation, albeit at a

slower pace (10). Healthcare

professionals however frequently lack awareness of the improvement

potential of patients during the chronic recovery phases (9). To address these challenges, there is

a need for improved outcome measures and carefully focused

interventions for patients with chronic stroke (10).

Neuroimaging serves a crucial role in predicting

outcomes and guiding rehabilitation strategies for patients with

stroke (11). MRI techniques,

including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional

neuroimaging, have shown promise in providing prognostic

information for individual patients during the early stages of

recovery (12). These advanced

imaging methods, when combined with clinical and neurophysiological

assessments, can be applied to tailor rehabilitation approaches

based on a patient's capacity for neural reorganization (12,13).

MRI techniques have the potential to provide comprehensive

assessments in chronic stroke, guiding treatment decisions for

optimal clinical outcomes. As neuroimaging technology continues to

advance, it is expected to serve an increasingly important role in

stroke recovery prediction and personalized rehabilitation planning

(14).

Advancements in MRI-compatible robotic devices have

enabled simultaneous neuroimaging and rehabilitation for patients

with stroke over the past decade. These devices, including soft

wearable gloves (15) and

hand-induced robotic systems (16-18),

allow for the monitoring of brain activity during rehabilitation

exercises. Previous studies have shown that training with such

devices can increase sensorimotor cortical activation, indicating

functional plasticity in patients with chronic stroke (19-21).

The combination of MRI and robotic-assisted therapy demonstrates

the potential of enhancing the understanding of brain plasticity

and improving stroke recovery outcomes (20-22).

Despite the promising advancements in neuroimaging

and robotic-assisted rehabilitation for patients with chronic

stroke, to the best of our knowledge, a comprehensive assessment

integrating functional MRI (fMRI) and DTI for triaging and

predicting motor improvement potential in this patient population

remains lacking. Current approaches are frequently ineffective at

systematically evaluating neural mechanisms underlying recovery or

identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from robotic

rehabilitation interventions. This knowledge gap limits the ability

to personalize rehabilitation strategies and optimize outcomes for

chronic stroke survivors.

Therefore, the present study aims to address this

need by leveraging a combined functional and structural brain

assessment to triage patients with chronic stroke and evaluate

their potential for motor improvement following robotic device

training. By integrating advanced neuroimaging with robotic

rehabilitation, the present study seeks to provide a deeper

understanding of brain plasticity during chronic stroke and

establish a framework for tailored, evidence-based therapeutic

interventions.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with chronic stroke were identified only by

using the Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, USA) stroke

survivor registries. The patients had been admitted between July

2006 and May 2019, and the registries were accessed by the authors

between January 2019 and December 2023 for this study. Eligible

participants were right-handed [per the revised Edinburgh

Handedness Inventory EIH-8(23)]

adults who had sustained a first-ever left middle cerebral artery

ischemic stroke ≥6 months prior to enrollment and those who

exhibited persistent right-hand weakness [Medical Research Council

scale (24) <4 for ≥48 h]. To

minimize heterogeneity and ensure reliable task performance during

fMRI and robotic training, individuals with significant cognitive

or sensory impairments were excluded. These impairments were

defined as the inability to understand and comply with the fMRI

task instructions. Additional exclusion criteria comprised any

contraindications to MRI (such as metallic implants and severe

claustrophobia), a history of other neurological (for example

multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease) or major psychiatric

disorders (for example schizophrenia and bipolar disorder), and any

orthopedic or systemic conditions affecting motor function of the

stroke-affected hand (for example, severe arthritis and peripheral

neuropathy). All participants provided informed consent in writing,

to a study that was approved by the Central Institutional review

board serving Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and

Women's Hospital Institutional review board (Partners Human

Research Committee, approval no. 2005P000570).

Rehabilitation protocol

Patients underwent a supervised home-based

rehabilitation program using the third-generation Magnetic

Resonance Compatible Hand-Induced RObotic Device (MR_CHIROD), an

in-house-developed system, paired with an interactive game

(25). The training regime

consisted of 45-min sessions conducted three times per week for 10

weeks. Motor performance assessments were conducted at the

following time points: i) Before training (baseline); ii) monthly

during training; and iii) 1-month post-training. Evaluations

applied included the Fugl-Meyer assessment for upper extremity

(FMA-UE) scale for sensorimotor impairment that are comprised of

subscales for wrist, hand, coordination, sensation, passive joint

motion, joint pain and total motor function. These subscales enable

the comprehensive evaluation of upper extremity impairment

(26). Functional hand use was

assessed using the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) (27), with subcategories for grasp, grip,

pinch, gross movement and total performance. Spasticity severity

was quantified using the modified Ashworth scale for the elbow,

wrist, fingers and thumb (28).

Hand grip strength (Force) was measured using a dynamometer (Jamar

Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer 12-0600; Fabrication Enterprises, Inc.),

whereas manual dexterity was evaluated using the Box and Blocks

Test (BBT) (29). These

assessments were selected to capture multiple dimensions of motor

impairment, functional recovery and spasticity, offering a detailed

understanding of the progress of each patient.

Imaging protocol

All imaging was performed using a 3T Siemens Skyra

scanner equipped with a 32-channel phased-array coil (Siemens

Healthineers). The imaging protocol included several sequences.

T1-weighted anatomical imaging was conducted using a sagittal

magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence [repetition

time (TR)/echo time (TE)/inversion time (TI), 2,300/2.53/900 msec;

field of view (FOV), 256 mm; resolution, 1x1x1 mm3;

parallel acquisition technique (PAT) factor, 2; acquisition time,

5.5 min]. Field mapping utilized a double-echo fast gradient-echo

sequence (TR, 650 msec; TE1/TE2, 4.92/7.38 msec; FOV, 220 mm;

resolution, 2x2x2 mm3). fMRI data were acquired using

echo-planar imaging (TR/TE, 3,000/30 msec; FOV, 220 mm; resolution,

2x2x2 mm3; PAT factor, 2; 100 dynamics). DTI was

performed with an axial spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence

(b-values 0/1,000 sec/mm2; TR/TE, 12,200/104 msec; 30

directions; resolution, 2x2x2 mm3). Additionally, a 3D

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence was included for

clinical evaluation (TR/TE/TI, 5,000/386/1,800 msec; resolution,

0.5x0.5x0.9 mm3).

Motor paradigm

During fMRI, participants performed a motor task

using the MR_CHIROD device with their right hand in a ‘boxcar’

paradigm (30), alternating

between 21-sec rest and action blocks. During action blocks,

participants synchronized grip compression and release with a

visual metronome set at 0.52 Hz. During rest blocks, participants

fixated on a stationary cross at the center of the screen, serving

as a low-level baseline condition. In total, three fMRI scans were

conducted per imaging session, each with a resistive force

(resistive level) adjusted to 60, 40 or 20% of the pre-scanned

maximum grip strength. To minimize motion artifacts, foam padding

and straps were used, where mirror movements in the non-active hand

were closely monitored.

Image processing

fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzed using

‘SPM12’ (30) in MATLAB 9.10

(MathWorks, Inc.). Preprocessing procedures included slice timing

correction, realignment to correct head motion, co-registration of

functional to T1-weighted anatomical images, normalization to the

Montreal Neurological Institute template (30) (2x2x2 mm3 resolution) and

smoothing with an 8-mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. Intra-subject analysis

used a general linear model, with the motor task modeled as a

boxcar function convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response

function, including action/rest regressors and motion parameters as

nuisance variables. Contrasts compared action with rest, using

statistical maps thresholded at P<0.05 (family-wise

error-corrected). A region of interest analysis was conducted on

the thresholded SPM_T maps using the Human Motor Area Template

Atlas (31). For each defined

region of interest, statistical measures, including maximum

activation (max), cluster size (size) and mean activation (mean),

were calculated separately for the left (L) and right (R)

hemispheres. The analysis focused on key motor-related regions,

such as the cerebellum (Cer), primary motor cortex (M1), ventral

premotor cortex (PMv), dorsal premotor cortex (PMd), primary

somatosensory cortex (S1) and supplementary motor area (SMA).

DTI data were processed using FMRIB Software

Library, version 6.0 (Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging,

University of Oxford). Pre-processing included correction for eddy

currents and head motion, followed by brain extraction. Diffusion

tensors were fitted to generate maps of fractional anisotropy (FA)

and mean diffusivity (MD). For region-of-interest analysis, the JHU

white matter tract atlas (32) was

used to define motor-related tracts in the stroke-affected

hemisphere. Mean FA and MD values were extracted for the following

motor related tracts of the lesioned left hemisphere: Corticospinal

tract, cerebral peduncle, posterior limb of the internal capsule

and posterior corona radiata.

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were employed

to analyze the repeated measures data structure arising from five

experimental sessions and three resistive levels. This modeling

approach is suited for datasets involving multiple observations

from the same participants under different conditions, since it

accounts for the non-independence of repeated measurements

(33). Both fixed effects and

random effects were included in the models. Fixed effects consisted

of session (ordinal variable with values 1,2,3,4,5), Resistive

level, sex, age and relevant clinical measures, providing estimates

of the overall influence of these variables across the entire

sample. Random intercepts were incorporated to account for

individual differences and to accurately model within-subject

variability, thereby improving the precision of effect estimates.

To address potential violations of standard model assumptions, such

as non-normality and heteroscedasticity, robust covariance

estimates (sandwich estimators) were applied using SPSS. This

method adjusts the estimated standard errors of fixed effects to

provide valid statistical inference despite deviations from

standard assumptions (34).

Maximum likelihood estimation was used to accommodate missing data

and to handle outcome variables that did not follow a normal

distribution, ensuring that the hierarchical structure of the

dataset was appropriately modeled and that all available data were

utilized.

The statistical analysis consisted of two primary

components. The first component (motor assessment) evaluated the

association between clinical scale scores and neuroimaging

measurements across all five sessions using GLMM, thereby assessing

the relationship between brain plasticity and motor performance

throughout the intervention period. The second component (motor

prediction) focused on identifying early neuroimaging predictors of

motor improvement using GLMM by examining whether imaging

measurements from the first two sessions could predict changes in

motor performance, as measured by the difference in clinical scale

scores between the final session and the initial sessions.

Among the clinical outcome measures, particular

emphasis was placed on the ARAT Grip scores, given their direct

relevance to both the fMRI task and the rehabilitation exercises.

Additional dependent variables included the FMA_UE scale, the BBT

and Force. In all models, session, resistive level, sex and age

were included as covariates to control for potential confounding

effects. Model performance was assessed using the-2 log-likelihood

(-2LL) criterion, facilitating comparison of model fit. All

statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (IBM

Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a significance for the

estimated regression coefficients.

Results

Baseline data

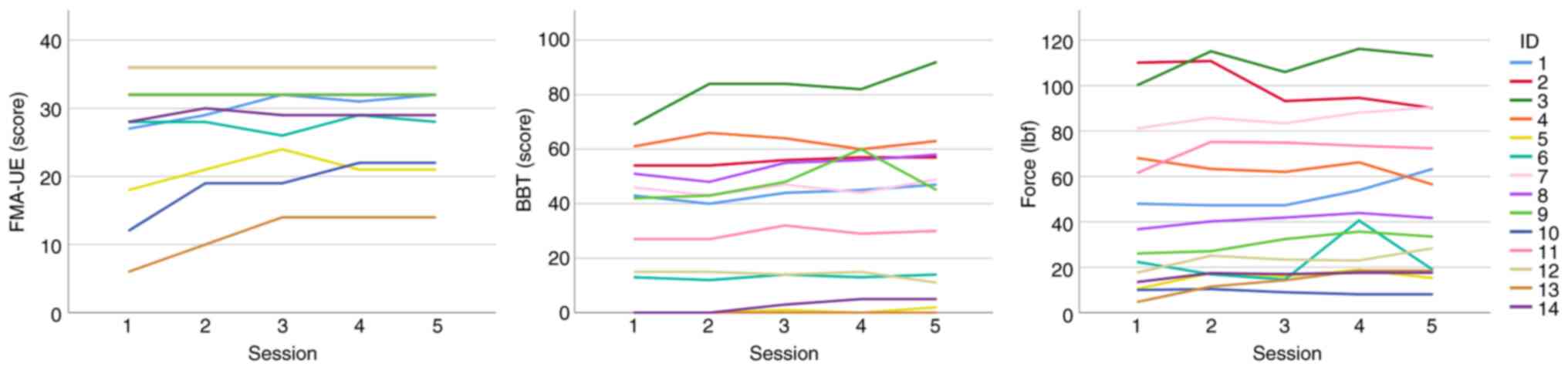

In total, 14 chronic patients with left middle

cerebral artery ischemic stroke (sex, 8 females, 6 males; age,

55.2±12.2 years) completed 210 MRI sessions (5 timepoints x3

resistive levels) during the present study. The Modified Ashworth

Scale was assessed in all patients and found to be 0, indicating

the absence of muscle spasticity, and thus spasticity was not

included as a variable in the statistical analyses. Table I displays their clinical

characteristics before rehabilitation, showing that according to

the FMA-UE scale, six patients presented with severe disability in

the range 0-28, and eight with moderate disability in the range

29-42(35). A total of three

patients achieved the >4-point motor improvement threshold for

clinically important difference according to the FMA-UE scale

(Fig. 1 and Table I) (36). Only two patients achieved the

corresponding improvement threshold in the BBT and seven patients

in Force scale (Table I) (37). ARAT-Grip was not analyzed, because

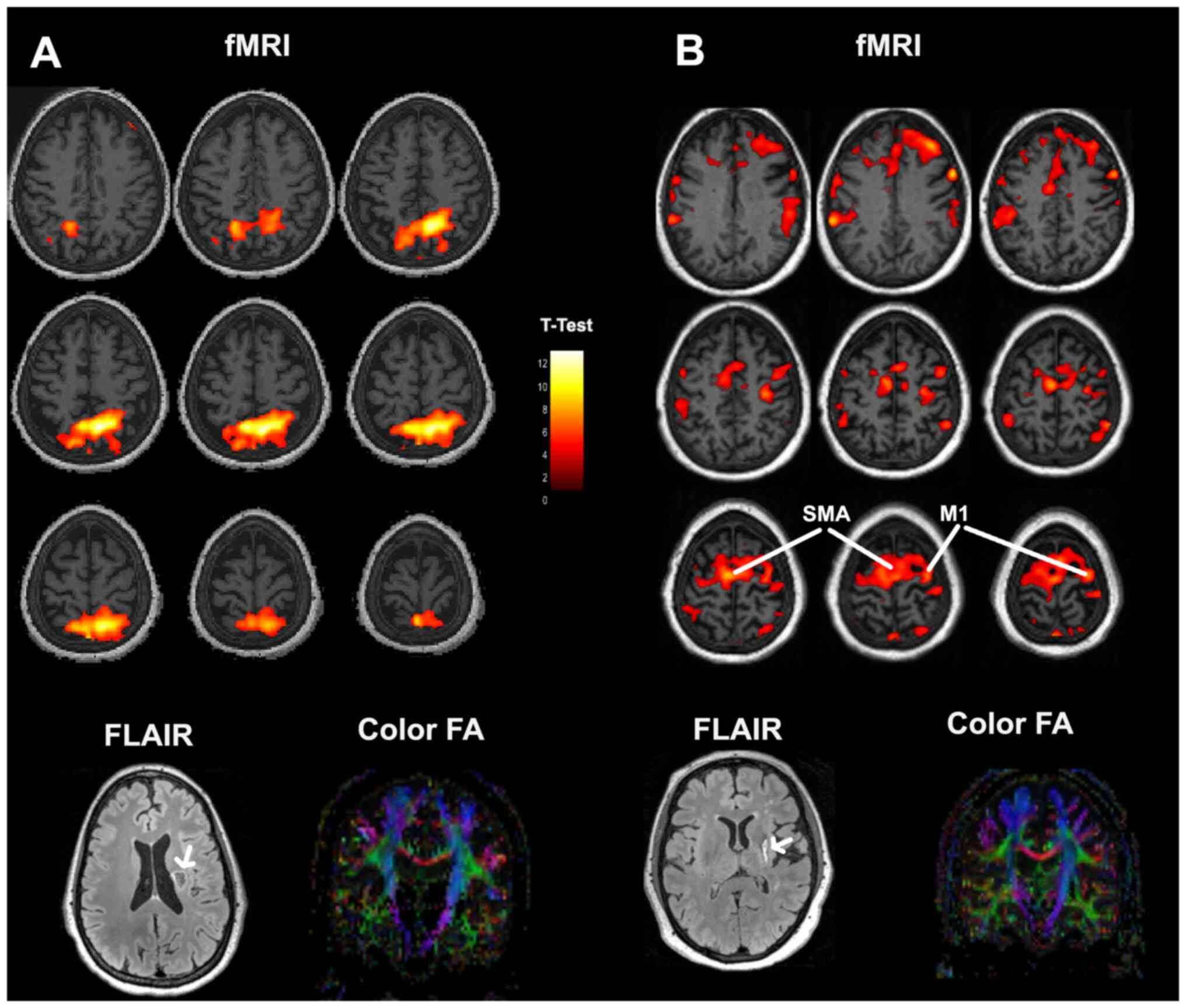

no changes were detected during the training sessions. Fig. 2 depicts a comparison between

baseline images of a patient (no. 14 in Table I) who failed to show significant

motor improvement and a patient (no. 13 in Table I) who succeeded. FLAIR images

reveal the site and extent of the stroke lesions. Colored brain

activation maps superimposed on T1 anatomical images illustrate

different activation patterns. Absence of progress is related to an

abnormal activation pattern with focal intense activation posterior

to the motor cortex. By contrast, normal left M1 and bilateral SMA

activation was observed in the patient who achieved motor gains

after rehabilitation. Coronal colored FA images indicate an intact

corticospinal tract at the lesioned hemisphere in both cases.

| Table IClinical characteristics of patients

with chronic stroke, motor scores at baseline and differences with

the last session. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic stroke, motor scores at baseline and differences with

the last session.

| Patients no. | Sex | Age, years | FMA-UE | Δ(FMA_UE) | BBT | Δ(BBT) | Force,

pound-force | Δ(Force),

pound-force |

|---|

| 1 | F | 39.1 | 27 | 5 | 43 | 4 | 56.4 | 15.3 |

| 2 | M | 64.2 | 36 | 0 | 54 | 3 | 105.7 | -20 |

| 3 | M | 50.2 | 36 | 0 | 69 | 23 | 103.8 | 12.9 |

| 4 | F | 47.3 | 36 | 0 | 61 | 2 | 72.7 | -11.7 |

| 5 | F | 60.5 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 51.5 | 4.8 |

| 6 | F | 46.5 | 28 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 45.8 | -3.5 |

| 7 | M | 41.0 | 32 | 0 | 46 | 3 | 81.1 | 9.3 |

| 8 | F | 34.0 | 32 | 0 | 51 | 7 | 39.9 | 5 |

| 9 | F | 70.0 | 32 | 0 | 42 | 3 | 30.8 | 7.4 |

| 10 | M | 58.5 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 71.5 | -1.9 |

| 11 | M | 71.4 | 36 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 53.7 | 10.9 |

| 12 | M | 67.9 | 36 | 0 | 15 | -4 | 52.3 | 10.8 |

| 13 | F | 64.5 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 41.9 | 13.8 |

| 14 | F | 57.1 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 64.8 | 4.1 |

Motor assessment

Analysis revealed distinct patterns linking

neuroimaging markers to motor outcomes (Table II). In the ipsilesional

hemisphere, activation in M1 and SMA showed robust positive

associations with motor performance. The mean activation in left M1

is positively associated with both the BBT (B=7.57 and P<0.001)

and Force (B=8.65 and P<0.001) measures, suggesting that

stronger, more focused recruitment of the core motor areas supports

superior motor performance. By contrast, activation in left

premotor regions is characterized by negative associations.

Specifically, increased activity in the left PMv (max_PMv_L,

B=-0.91 and P=0.001) and PMd (mean_PMd_L, B=-1.70 and P=0.023 for

FMA-UE; B=-11.84 and P<0.001 for Force) appeared to associate

with poorer motor outcomes, which indicate that diffuse or

excessive recruitment in these secondary regions may reflect

compensatory mechanisms that are less efficient. A similar trend is

observed in the left S1 (max_S1_L, B=-0.54 and P=0.014), where

overactivation is negatively associated with motor performance.

| Table IIGeneralized linear mixed model

results for motor function outcomes: Associations with age, sex,

session progression (ordinal variable with values 1-5) and imaging

measurements. |

Table II

Generalized linear mixed model

results for motor function outcomes: Associations with age, sex,

session progression (ordinal variable with values 1-5) and imaging

measurements.

| A, Fugl-Meyer

assessment for upper extremity |

|---|

| Parameter | B | SE | P-value |

|---|

| Session=1 | 49.85 | 35.69 | 0.166 |

| Session=2 | 49.90 | 35.89 | 0.168 |

| Session=3 | 51.55 | 35.79 | 0.153 |

| Session=4 | 51.42 | 35.76 | 0.154 |

| Session=5 | 50.89 | 35.67 | 0.157 |

| Resistive

level=60% | -0.26 | 0.29 | 0.370 |

| Resistive

level=20% | -0.40 | 0.24 | 0.102 |

| Sex=Female | 8.54 | 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.452 |

| Max_Cer_L | -0.41 | 0.24 | 0.090 |

| Size_Cer_L |

-3.32x10-4 |

9.35x10-5 | 0.001 |

| Mean_Cer_L | 4.03 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Max_M1_L | 1.19 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Size_M1_L, (8

mm3) |

-1.61x10-3 |

8.47x10-4 | 0.061 |

| Mean_M1_L | -1.32 | 0.77 | 0.089 |

| Max_PMv_L | -0.91 | 0.26 | 0.001 |

| Size_PMv_L, (8

mm3) |

9.76x10-5 |

3.13x10-4 | 0.756 |

| Mean_PMv_L | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.339 |

| Max_PMd_L | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.670 |

| Size_PMd_L, (8

mm3) |

8.06x10-4 |

4.24x10-4 | 0.060 |

| Mean_PMd_L | -1.70 | 0.74 | 0.023 |

| Max_S1_L | -0.54 | 0.21 | 0.014 |

| Size_S1_L, (8

mm3) |

2.65x10-3 |

9.14x10-4 | 0.005 |

| Mean_S1_L | -0.76 | 0.47 | 0.108 |

| Max_SMA_L | 0.86 | 0.31 | 0.006 |

| Size_SMA_L, (8

mm3) |

-3.38x10-3 |

7.32x10-4 | <0.001 |

| Mean_SMA_L | 3.38 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| Max_Cer_R | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.298 |

| Size_Cer_R, (8

mm3) |

2.75x10-4 |

1.20x10-4 | 0.024 |

| Mean_Cer_R | -2.13 | 1.06 | 0.046 |

| Max_M1_R | -0.06 | 0.28 | 0.826 |

| Size_M1_R, (8

mm3) |

-3.82x10-4 |

3.02x10-4 | 0.208 |

| Mean_M1_R | 1.35 | 0.67 | 0.046 |

| Max_PMv_R | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.062 |

| Size_PMv_R, (8

mm3) |

-8.89x10-6 |

4.90x10-4 | 0.986 |

| Mean_PMv_R | -3.27 | 1.19 | 0.007 |

| Max_PMd_R | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.432 |

| Size_PMd_R, (8

mm3) |

-8.43x10-4 |

4.94x10-4 | 0.091 |

| Mean_PMd_R | 1.50 | 1.01 | 0.141 |

| Max_S1_R | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.169 |

| Size_S1_R, (8

mm3) |

5.63x10-4 |

4.34x10-4 | 0.198 |

| Mean_S1_R | -0.30 | 0.45 | 0.503 |

| Max_SMA_R | -1.79 | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Size_SMA_R, (8

mm3) |

2.50x10-3 |

6.12x10-4 | <0.001 |

| Mean_SMA_R | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.907 |

| FA Corticospinal

tract | 34.88 | 5.50 | <0.001 |

| FA Cerebral

peduncle | 0.68 | 9.15 | 0.941 |

| FA Posterior limb

of internal capsule | 133.10 | 13.05 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior corona

radiata | -283.94 | 37.85 | <0.001 |

| MD Corticospinal

tract (10-6 mm2/s) | -57,624.69 | 8909.14 | <0.001 |

| MD Cerebral

peduncle (10-6 mm2/s) | 1,850.91 | 20582.64 | 0.929 |

| MD Posterior limb

of internal capsule (10-6 mm2/s) | 89,988.54 | 21056.94 | <0.001 |

| MD Posterior corona

radiata (10-6 mm2/s) | -52,670.76 | 26162.98 | 0.047 |

| B, Box and block

test |

| Parameter | B | SE | P-value |

| Session=1 | 665.00 | 73.44 | <0.001 |

| Session=2 | 665.97 | 74.01 | <0.001 |

| Session=3 | 669.93 | 73.86 | <0.001 |

| Session=4 | 669.98 | 73.86 | <0.001 |

| Session=5 | 672.63 | 73.79 | <0.001 |

| Force=60% | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.665 |

| Force=20% | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.290 |

| Sex=Female | 29.01 | 2.26 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | -1.98 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Max_Cer_L | -1.17 | 0.50 | 0.021 |

| Size_Cer_L, (8

mm3) |

3.3x10-5 |

2.04x10-6 | 0.872 |

| Mean_Cer_L | 2.46 | 1.91 | 0.200 |

| Max_M1_L | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.857 |

| Size_M1_L, (8

mm3) |

-2.15x10-3 |

1.60x10-3 | 0.183 |

| Mean_M1_L | 7.57 | 1.93 | <0.001 |

| Max_PMv_L | -0.29 | 0.53 | 0.580 |

| Size_PMv_L, (8

mm3) |

-9.77x10-4 |

8.26x10-4 | 0.240 |

| Mean_PMv_L | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.875 |

| Max_PMd_L | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.103 |

| Size_PMd_L, (8

mm3) |

1.04x10-3 |

1.13x10-3 | 0.358 |

| Mean_PMd_L | -8.52 | 1.48 | <0.001 |

| Max_S1_L | -0.69 | 0.46 | 0.133 |

| Size_S1_L, (8

mm3) |

2.97x10-3 |

1.89x10-3 | 0.120 |

| Mean_S1_L | -2.52 | 0.95 | 0.009 |

| Max_SMA_L | -0.51 | 0.66 | 0.447 |

| Size_SMA_L, (8

mm3) |

-4.60x10-3 |

1.69x10-3 | 0.008 |

| Mean_SMA_L | 7.16 | 1.88 | <0.001 |

| Max_Cer_R | -0.23 | 0.57 | 0.692 |

| Size_Cer_R, (8

mm3) |

-1.10x10-4 |

2.76x10-4 | 0.692 |

| Mean_Cer_R | 1.65 | 2.45 | 0.503 |

| Max_M1_R | -3.16 | 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Size_M1_R, (8

mm3) |

5.41x10-4 |

8.65x10-4 | 0.533 |

| Mean_M1_R | -2.07 | 1.72 | 0.232 |

| Max_PMv_R | -2.89 | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Size_PMv_R, (8

mm3) |

-4.97x10-4 |

9.98x10-4 | 0.619 |

| Mean_PMv_R | -0.76 | 2.63 | 0.774 |

| Max_PMd_R | 2.66 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Size_PMd_R, (8

mm3) |

5.97x10-4 |

1.25x10-3 | 0.634 |

| Mean_PMd_R | -3.37 | 2.32 | 0.149 |

| Max_S1_R | 0.79 | 0.50 | 0.113 |

| Size_S1_R, (8

mm3) |

-5.65x10-4 |

1.04x10-3 | 0.589 |

| Mean_S1_R | 3.38 | 1.12 | 0.003 |

| Max_SMA_R | -0.15 | 0.68 | 0.827 |

| Size_SMA_R, (8

mm3) |

3.16x10-3 |

1.45x10-3 | 0.031 |

| Mean_SMA_R | 0.64 | 1.34 | 0.636 |

| FA Corticospinal

tract | -20.01 | 11.20 | 0.077 |

| FA Cerebral

peduncle | 203.93 | 19.31 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior limb

of internal capsule | 493.18 | 26.26 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior corona

radiata | -1,409.10 | 76.95 | <0.001 |

| MD Corticospinal

tract (10-6 mm2/s) | -25,075.34 | 18,703.06 | 0.183 |

| MD Cerebral

peduncle (10-6 mm2/s) | -322,732.16 | 42,539.39 | <0.001 |

| MD Posterior limb

of internal capsule (10-6 mm2/s) | 551,343.22 | 41,706.80 | <0.001 |

| MD Posterior corona

radiata (10-6 mm2/s) | -567,911.91 | 52,335.33 | <0.001 |

| C, Force |

| Parameter | B | SE | P-value |

| Session=1 | 400.67 | 110.93 | <0.001 |

| Session=2 | 405.02 | 111.68 | <0.001 |

| Session=3 | 403.23 | 111.31 | <0.001 |

| Session=4 | 407.88 | 111.42 | <0.001 |

| Session=5 | 407.23 | 111.39 | <0.001 |

| Force=60% | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.348 |

| Force=20% | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.484 |

| Sex=Female | -26.43 | 3.81 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | -0.88 | 0.40 | 0.031 |

| Max_Cer_L | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.412 |

| Size_Cer_L, (8

mm3) |

-4.16x10-4 |

2.43x10-4 | 0.090 |

| Mean_Cer_L | -6.50 | 2.02 | 0.002 |

| Max_M1_L | -0.91 | 0.48 | 0.060 |

| Size_M1_L, (8

mm3) |

-4.93x10-3 |

1.73x10-3 | 0.005 |

| Mean_M1_L | 8.65 | 2.04 | <0.001 |

| Max_PMv_L | -1.14 | 0.62 | 0.068 |

| Size_PMv_L, (8

mm3) |

3.15x10-3 |

1.50x10-3 | 0.039 |

| Mean_PMv_L | 1.59 | 1.32 | 0.229 |

| Max_PMd_L | 1.93 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Size_PMd_L, (8

mm3) |

-3.42x10-3 |

1.58x10-3 | 0.033 |

| Mean_PMd_L | -11.84 | 2.18 | <0.001 |

| Max_S1_L | -1.64 | 0.61 | 0.009 |

| Size_S1_L, (8

mm3) |

3.16x10-3 |

2.30x10-3 | 0.172 |

| Mean_S1_L | -0.05 | 1.16 | 0.967 |

| Max_SMA_L | 0.36 | 0.97 | 0.710 |

| Size_SMA_L, (8

mm3) |

1.10x10-3 |

2.51x10-3 | 0.663 |

| Mean_SMA_L | 10.73 | 1.88 | <0.001 |

| Max_Cer_R | 0.45 | 0.85 | 0.596 |

| Size_Cer_R, (8

mm3) |

3.19x10-4 |

3.14x10-4 | 0.312 |

| Mean_Cer_R | 6.85 | 3.11 | 0.030 |

| Max_M1_R | -5.64 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Size_M1_R, (8

mm3) |

2.79x10-4 |

9.01x10-4 | 0.757 |

| Mean_M1_R | -0.40 | 2.06 | 0.848 |

| Max_PMv_R | -3.05 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Size_PMv_R, (8

mm3) |

-2.90x10-3 |

1.20x10-3 | 0.018 |

| Mean_PMv_R | 1.99 | 3.20 | 0.536 |

| Max_PMd_R | 3.35 | 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Size_PMd_R, (8

mm3) |

1.26x10-3 |

1.49x10-3 | 0.397 |

| Mean_PMd_R | -3.81 | 3.18 | 0.234 |

| Max_S1_R | 1.79 | 0.75 | 0.018 |

| Size_S1_R, (8

mm3) |

-1.33x10-3 |

1.10x10-3 | 0.233 |

| Mean_S1_R | 3.28 | 1.23 | 0.009 |

| Max_SMA_R | -2.22 | 0.88 | 0.013 |

| Size_SMA_R, (8

mm3) | 0.01 |

1.73x10-3 | 0.004 |

| Mean_SMA_R | -0.46 | 1.10 | 0.677 |

| FA Corticospinal

tract | -55.34 | 17.05 | 0.002 |

| FA Cerebral

peduncle | -97.80 | 36.37 | 0.008 |

| FA Posterior limb

of internal capsule | 172.38 | 34.05 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior corona

radiata | -256.99 | 122.14 | 0.038 |

| MD Corticospinal

tract (10-6 mm2/s) | 21,981.23 | 28,434.79 | 0.441 |

| MD Cerebral

peduncle (10-6 mm2/s) | 63,281.49 | 72,490.82 | 0.385 |

| MD Posterior limb

of internal capsule (10-6 mm2/s) | -24,991.11 | 74,130.48 | 0.737 |

| MD Posterior corona

radiata (10-6 mm2/s) | -284,152.48 | 81,310.86 | 0.001 |

In the contralesional hemisphere, the relationships

were found to be more nuanced. Activation in right M1 (max_M1_R,

B=-3.16 and P<0.001 for BBT; B=-5.64 and P<0.001 for Force)

and right PMv (max_PMv_R, B=-2.89 and P<0.001 for BBT) exhibited

negative associations with motor scales, implying that excessive

recruitment in these regions may be maladaptive. However, right PMd

showed a positive association (max_PMd_R: B=2.66 and P<0.001 for

BBT; B=3.35 and P<0.001 for Force), which may suggest that

selective engagement of this region can serve a compensatory

function when the ipsilesional network is compromised. In addition,

right S1 activation is positively associated with motor performance

(mean_S1_R, B=3.38 and P=0.003 for BBT; mean_S1_R, B=3.28 and

P=0.009 for Force), indicating that contralesional sensory

processing may serve a beneficial role. By contrast, right SMA

activation (max_SMA_R, B=-1.79 and P<0.001 for FMA-UE) was

negatively associated with motor function, further supporting the

notion that not all contralesional recruitment contributes equally

to recovery.

DTI metrics add a complementary perspective, by

reflecting white matter integrity. Higher FA values in the

corticospinal tract (B=34.88 and P<0.001 for FMA-UE) and

posterior limb of the internal capsule (B=133.10 and P<0.001 for

FMA-UE; B=493.18 and P<0.001 for BBT) associated positively with

motor scales, supporting the importance of intact descending

pathways for functional recovery. By contrast, increased FA in the

posterior corona radiata (B=-283.94 and P<0.001 for FMA-UE;

B=-1,409.10 and P<0.001 for BBT) was negatively associated with

motor performance. MD measurements also aligned with this

interpretation. Specifically, elevated MD in posterior corona

radiata (B=-567,911.91 and P<0.001 for BBT; B=-284,152.48 and

P=0.001 for Force) tended to associate with inferior motor

outcomes, suggesting that tissue damage and subsequent structural

disorganization adversely affect recovery.

Motor prediction

Changes in the ipsilesional cortex (left hemisphere)

demonstrate a mixed pattern of positive and negative associations

between peak or mean activation and rehabilitation-induced motor

gains (Table III). Maximum

activation in left M1 (max_M1_L, B=0.67 and P=0.002) and cluster

size in left M1 (size_M1_L, B=2.81x10-3 and P=0.001)

both show positive relationships with Δ(FMA-UE), whilst mean

activation in left M1 (mean_M1_L, B=-3.44 and P=0.001) is

negatively associated with Δ(FMA-UE). Similarly, left PMv exhibited

a positive association with Δ(FMA-UE) (mean_PMv_L, B=2.95 and

P=0.012), whereas left PMd associated negatively (mean_PMd_L,

B=-2.18 and P=0.010). In the left somatosensory cortex, activation

cluster size showed an inverse relationship with Δ(FMA-UE)

(size_S1_L: B=-2.32x10-3 and P=0.029) but a positive one

with Δ(BBT) (size_S1_L: B=0.02 and P=0.002), whereas mean

activation is positively associated with Δ(FMA-UE) (mean_S1_L,

B=2.27 and P=0.021). Finally, negative associations in left SMA

maximum (max_SMA_L, B=-1.46 and P=0.044) and mean activations

(mean_SMA_L, B=-2.84 and P=0.004) suggest that heightened

activation in this region may not necessarily translate into

improved upper-limb function.

| Table IIIResults of generalized linear mixed

model analysis: Rehabilitation induced motor scores' changes

predicted by demographics and imaging measurements from the first

two sessions (session values 1 and 2). |

Table III

Results of generalized linear mixed

model analysis: Rehabilitation induced motor scores' changes

predicted by demographics and imaging measurements from the first

two sessions (session values 1 and 2).

| A, Δ(Fugl-Meyer

assessment for upper extremity) |

|---|

| Parameter | B | SE | P-value |

|---|

| Session=1 | -8.34 | 28.98 | 0.777 |

| Session=2 | -9.18 | 28.84 | 0.754 |

| Resistive

level=60% | -0.11 | 0.33 | 0.753 |

| Resistive

level=40% | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.281 |

| Sex=Female | -9.71 | 2.24 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.026 |

| Max_Cer_L | -0.87 | 0.3 | 0.009 |

| Size_Cer_L, (8

mm3) |

1.31x10-4 |

2.41x10-4 | 0.595 |

| Mean_Cer_L | -0.3 | 1.24 | 0.812 |

| Max_M1_L | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.002 |

| Size_M1_L, (8

mm3) |

2.81x10-3 |

6.62x10-4 | 0.001 |

| Mean_M1_L | -3.44 | 0.84 | 0.001 |

| Max_PMv_L | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.721 |

| Size_PMv_L, (8

mm3) |

2.89x10-4 |

3.84x10-4 | 0.462 |

| Mean_PMv_L | 2.95 | 1.05 | 0.012 |

| Max_PMd_L | -0.13 | 0.36 | 0.724 |

| Size_PMd_L, (8

mm3) |

-1.04x10-4 |

5.27x10-4 | 0.846 |

| Mean_PMd_L | -2.18 | 0.76 | 0.01 |

| Max_S1_L | -0.15 | 0.32 | 0.644 |

| Size_S1_L, (8

mm3) |

-2.32x10-3 |

9.75x10-4 | 0.029 |

| Mean_S1_L | 2.27 | 0.89 | 0.021 |

| Max_SMA_L | -1.46 | 0.67 | 0.044 |

| Size_SMA_L, (8

mm3) |

-1.02x10-3 |

5.59x10-4 | 0.086 |

| Mean_SMA_L | -2.84 | 0.86 | 0.004 |

| Max_Cer_R | 0.85 | 0.31 | 0.016 |

| Size_Cer_R, (8

mm3) |

-2.37x10-4 |

1.55x10-4 | 0.145 |

| Mean_Cer_R | 1.45 | 0.76 | 0.073 |

| Max_M1_R | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.77 |

| Size_M1_R, (8

mm3) |

1.59x10-4 |

4.84x10-4 | 0.747 |

| Mean_M1_R | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.611 |

| Max_PMv_R | -0.81 | 0.31 | 0.019 |

| Size_PMv_R, (8

mm3) |

9.32x10-4 |

5.03x10-4 | 0.081 |

| Mean_PMv_R | -0.66 | 1.16 | 0.579 |

| Max_PMd_R | -0.78 | 0.4 | 0.066 |

| Size_PMd_R, (8

mm3) |

-1.37x10-3 |

5.87x10-4 | 0.032 |

| Mean_PMd_R | 3.43 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Max_S1_R | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.383 |

| Size_S1_R, (8

mm3) |

1.98x10-4 |

6.88x10-4 | 0.777 |

| Mean_S1_R | -0.51 | 0.76 | 0.514 |

| Max_SMA_R | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.011 |

| Size_SMA_R, (8

mm3) |

-9.67x10-4 |

6.21x10-4 | 0.138 |

| Mean_SMA_R | 5.27 | 1.05 | <0.001 |

| FA Corticospinal

tract | 0.35 | 2.92 | 0.906 |

| FA Cerebral

peduncle | -57.84 | 13.54 | 0.001 |

| FA Posterior limb

of internal capsule | -102.86 | 24 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior corona

radiate | 164.28 | 42.06 | 0.001 |

| MD Corticospinal

tract (10-6 mm2/s) | 5,347.84 | 6,443.77 | 0.418 |

| MD Cerebral

peduncle (10-6 mm2/s) | 83,833.91 | 21,245.93 | 0.001 |

| MD Posterior limb

of internal capsule (10-6 mm2/s) | -132,136.83 | 26,796.45 | <0.001 |

| MD Posterior corona

radiata (10-6 mm2/s) | 67,404.04 | 20,132.5 | 0.004 |

| B, Δ(Box and block

test) |

| Parameter | B | SE | P-value |

| Session=1 | 548.91 | 132.81 | 0.001 |

| Session=2 | 547.51 | 132.31 | 0.001 |

| Force=60% | -0.2 | 1.32 | 0.879 |

| Force=40% | 0.29 | 0.96 | 0.766 |

| Sex=female | 15.45 | 6.66 | 0.033 |

| Age, years | -3.07 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Max_Cer_L | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.43 |

| Size_Cer_L, (8

mm3) |

-4.33x10-4 |

6.72x10-4 | 0.528 |

| Mean_Cer_L | 0.84 | 4.14 | 0.841 |

| Max_M1_L | -1.24 | 0.71 | 0.1 |

| Size_M1_L, (8

mm3) |

-1.54x10-3 |

2.38x10-3 | 0.526 |

| Mean_M1_L | 4.82 | 2.66 | 0.087 |

| Max_PMv_L | 2.58 | 1.31 | 0.066 |

| Size_PMv_L, (8

mm3) |

-3.63x10-3 |

1.69x10-3 | 0.046 |

| Mean_PMv_L | -3.85 | 3.17 | 0.242 |

| Max_PMd_L | 1.11 | 1.35 | 0.421 |

| Size_PMd_L, (8

mm3) |

-1.53x10-3 |

1.67x10-3 | 0.373 |

| Mean_PMd_L | 0.77 | 2.43 | 0.754 |

| Max_S1_L | 0.12 | 0.92 | 0.899 |

| Size_S1_L, (8

mm3) | 0.02 |

4.47x10-3 | 0.002 |

| Mean_S1_L | -4.61 | 3.55 | 0.212 |

| Max_SMA_L | -0.99 | 1.63 | 0.552 |

| Size_SMA_L, (8

mm3) |

-9.01x10-4 |

2.14x10-3 | 0.679 |

| Mean_SMA_L | 0.81 | 4.1 | 0.846 |

| Max_Cer_R | -0.36 | 1.29 | 0.787 |

| Size_Cer_R, (8

mm3) |

3.71x10-4 |

4.98x10-4 | 0.466 |

| Mean_Cer_R | -3.68 | 2.61 | 0.176 |

| Max_M1_R | -0.17 | 0.89 | 0.849 |

| Size_M1_R, (8

mm3) |

-1.84x10-4 |

1.26x10-3 | 0.885 |

| Mean_M1_R | 2.41 | 2.65 | 0.376 |

| Max_PMv_R | 0.99 | 1.12 | 0.387 |

| Size_PMv_R, (8

mm3) |

3.96x10-3 |

1.93x10-3 | 0.056 |

| Mean_PMv_R | 2.03 | 2.61 | 0.448 |

| Max_PMd_R | -0.42 | 1.33 | 0.754 |

| Size_PMd_R, (8

mm3) |

4.39x10-3 |

1.70x10-3 | 0.019 |

| Mean_PMd_R | -1.56 | 3.02 | 0.613 |

| Max_S1_R | 1.96 | 0.51 | 0.001 |

| Size_S1_R, (8

mm3) |

-3.98x10-3 |

1.95x10-3 | 0.057 |

| Mean_S1_R | -4.82 | 2.95 | 0.121 |

| Max_SMA_R | -0.76 | 1 | 0.456 |

| Size_SMA_R, (8

mm3) |

-1.98x10-3 |

2.13x10-3 | 0.366 |

| Mean_SMA_R | -2.68 | 3.71 | 0.48 |

| FA Corticospinal

tract | -73.6 | 16.25 | <0.001 |

| FA Cerebral

peduncle | 230.56 | 42.29 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior limb

of internal capsule | 137.27 | 60.69 | 0.037 |

| FA Posterior corona

radiate | -556.04 | 126.08 | <0.001 |

| MD Corticospinal

tract (10-6 mm2/s) | 145,126.61 | 32,423.39 | <0.001 |

| MD Cerebral

peduncle (10-6 mm2/s) | -494,726.62 | 87,353.51 | <0.001 |

| MD Posterior limb

of internal capsule (10-6 mm2/s) | 485,377.99 | 89,218.61 | <0.001 |

| MD Posterior corona

radiata (10-6 mm2/s) | -461,455.03 | 87,259.39 | <0.001 |

| C, Δ(Force) |

| Parameter | B | SE | P-value |

| Session=1 | 690.63 | 118.59 | <0.001 |

| Session=2 | 686.6 | 118.22 | <0.001 |

| Resistive

level=60% | 1.58 | 1.04 | 0.145 |

| Resistive

level=40% | 1.76 | 0.93 | 0.075 |

| Sex=female | -29.42 | 5.52 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | -2.16 | 0.55 | 0.001 |

| Max_Cer_L | 0.72 | 1.12 | 0.526 |

| Size_Cer_L, (8

mm3) |

1.15x10-3 |

7.90x10-4 | 0.164 |

| Mean_Cer_L | -23.16 | 5.08 | <0.001 |

| Max_M1_L | 1.11 | 0.96 | 0.263 |

| Size_M1_L, (8

mm3) |

4.13x10-3 |

2.51x10-3 | 0.118 |

| Mean_M1_L | -7.19 | 3.84 | 0.079 |

| Max_PMv_L | 4.61 | 1.45 | 0.006 |

| Size_PMv_L, (8

mm3) |

1.51x10-4 |

2.45x10-3 | 0.952 |

| Mean_PMv_L | 1.46 | 3.6 | 0.69 |

| Max_PMd_L | -1.47 | 1.63 | 0.381 |

| Size_PMd_L, (8

mm3) |

-3.85x10-3 |

2.45x10-3 | 0.135 |

| Mean_PMd_L | -2.6 | 2.65 | 0.339 |

| Max_S1_L | -1.44 | 1.2 | 0.246 |

| Size_S1_L, (8

mm3) |

2.96x10-3 |

4.81x10-3 | 0.546 |

| Mean_S1_L | 6.97 | 4.18 | 0.114 |

| Max_SMA_L | -3.08 | 2.39 | 0.214 |

| Size_SMA_L, (8

mm3) |

2.57x10-3 |

2.32x10-3 | 0.283 |

| Mean_SMA_L | -0.54 | 4.26 | 0.901 |

| Max_Cer_R | 1.9 | 1.61 | 0.254 |

| Size_Cer_R, (8

mm3) |

-5.92x10-4 |

6.65x10-4 | 0.386 |

| Mean_Cer_R | 10.64 | 2.86 | 0.002 |

| Max_M1_R | 0.39 | 1.17 | 0.746 |

| Size_M1_R, (8

mm3) |

-6.09x10-4 |

1.29x10-3 | 0.644 |

| Mean_M1_R | 7.67 | 2.6 | 0.009 |

| Max_PMv_R | 0.37 | 1.47 | 0.803 |

| Size_PMv_R, (8

mm3) |

5.82x10-3 |

2.52x10-3 | 0.034 |

| Mean_PMv_R | 0.81 | 4.06 | 0.845 |

| Max_PMd_R | -0.85 | 1.23 | 0.503 |

| Size_PMd_R, (8

mm3) | 0.01 |

2.00x10-3 | 0.014 |

| Mean_PMd_R | -0.69 | 3.73 | 0.855 |

| Max_S1_R | -0.56 | 0.69 | 0.428 |

| Size_S1_R, (8

mm3) |

-1.41x10-3 |

3.23x10-3 | 0.669 |

| Mean_S1_R | -8.28 | 4.18 | 0.064 |

| Max_SMA_R | 0.71 | 1.22 | 0.572 |

| Size_SMA_R, (8

mm3) |

-6.46x10-3 |

2.88x10-3 | 0.038 |

| Mean_SMA_R | 0.98 | 3.81 | 0.8 |

| FA Corticospinal

tract | 27.6 | 20.53 | 0.196 |

| FA Cerebral

peduncle | 5.48 | 61.34 | 0.93 |

| FA Posterior limb

of internal capsule | -334.48 | 58.89 | <0.001 |

| FA Posterior corona

radiata | -182.63 | 121.68 | 0.152 |

| MD Corticospinal

tract (10-6 mm2/s) | 105,826.78 | 37,490.28 | 0.012 |

| MD Cerebral

peduncle (10-6 mm2/s) | -173259.08 | 106,242.82 | 0.121 |

| MD Posterior limb

of internal capsule (10-6 mm2/s) | 34,301.53 | 110,648.92 | 0.76 |

| MD Posterior corona

radiata (10-6 mm2/s) | -279,777.8 | 84,242.02 | 0.004 |

In the contralesional hemisphere, fewer significant

patterns emerged for motor improvement. Maximum activation in right

Cer showed a positive association with Δ(FMA-UE) (max_Cer_R, B=0.85

and P=0.016), whereas maximum activation in right PMv yielded a

negative association for the same outcome (max_PMv_R, B=-0.81 and

P=0.019). Right PMd is positively associated with Δ(FMA-UE)

(mean_PMd_R, B=3.43 and P<0.001), whilst its cluster size

exhibited a negative association with Δ(FMA-UE) (size_PMd_R,

B=-1.37x10-3 and P=0.032) and a positive association for

the other two scales [Δ(BBT): Size_PMd_R, B=4.39x10-3

and P=0.019; Δ(Force): Size_PMd_R, B=0.01 and P=0.014]. Right

somatosensory cortex yielded a positive association with changes in

BBT (max_S1_R, B=1.96 and P=0.001), whereas right SMA shows

consistent positive association with Δ(FMA-UE) (mean_SMA_R, B=5.27

and P<0.001).

Diffusion metrics revealed additional insights.

Negative associations between FA in the cerebral peduncle (FA

Cerebral peduncle, B=-57.84 and P=0.001) or posterior limb of the

internal capsule (FA Posterior limb of internal capsule, B=-102.86

and P<0.001) and Δ(FMA-UE), coupled with positive associations

for BBT (FA Cerebral peduncle, B=230.56 and P<0.001; FA

Posterior limb of internal capsule, B=137.27 and P=0.037), suggest

that microstructural changes in specific descending pathways may

differentially influence upper-limb function compared with gross

dexterity. FA in the posterior corona radiata exhibited an opposite

pattern [positive for Δ(FMA-UE), B=164.28 and P=0.001; negative for

Δ(BBT), B=-556.04 and P<0.001), indicating that microstructural

integrity in more diffuse white matter regions may favor certain

motor outcomes but not others. MD metrics reinforced this

distinction, with some regions (such as the corticospinal tract)

associating positively with Δ(BBT) (MD Corticospinal tract,

B=145,126.61 and P<0.001), whereas others (such as the cerebral

peduncle) appear to associate negatively to BBT (MD Cerebral

peduncle, B=-494,726.62 and P<0.001). Taken together, these

patterns reflect a complex interplay among focal ipsilesional

reactivation, contralesional compensatory mechanisms and white

matter tract integrity in determining changes in motor

outcomes.

Model comparison

Model fit comparisons for the three motor

assessments are presented in Table

IV. For prediction models, the -2LL values were substantially

lower overall because they used a smaller dataset. Within each

model type (assessment vs. prediction), the FMA-UE consistently

outperformed the BBT and Force, suggesting the greater sensitivity

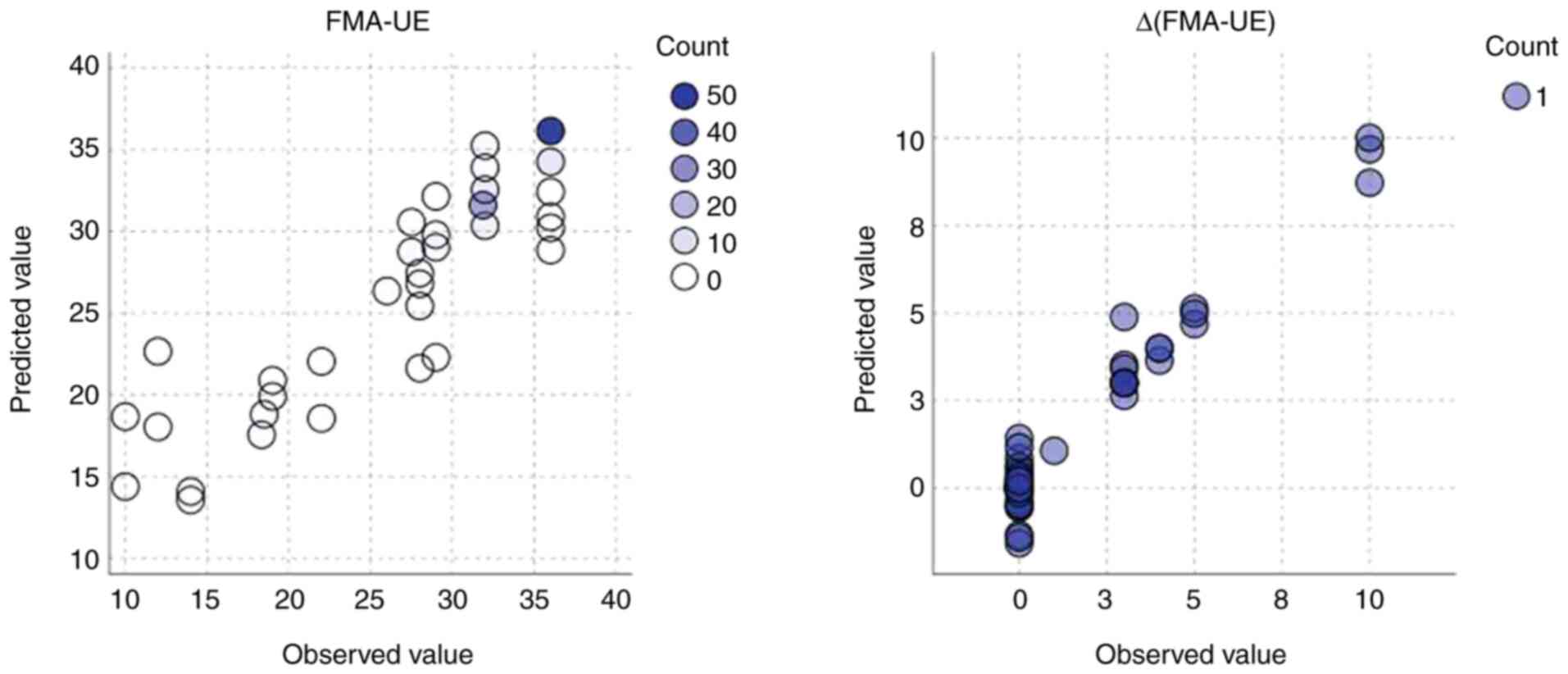

of neuroimaging data to FMA_UE changes. Fig. 3 illustrates the performance of GLMM

in predicting FMA-UE and its change [Δ(FMA-UE)] using circular

scatter plots displaying observed vs. predicted values, where

circle color indicates frequency. The clustering of the majority of

circles along the diagonal line of perfect prediction (observed

value=predicted value) in both plots indicates a strong agreement

between the model's estimates and the actual observed data. This

close alignment, observed for both absolute and change scores,

suggests that the FMA-UE is a reliable score for the assessment and

prediction of motor recovery, as evidenced by the model's ability

to accurately estimate both static and dynamic aspects of upper

extremity function.

| Table IVComparison of model fit across motor

assessments using-2 log likelihood values. |

Table IV

Comparison of model fit across motor

assessments using-2 log likelihood values.

| Motor | Fugl-Meyer

assessment for upper extremity | Box and blocks

test | Force |

|---|

| Assessment

model | 652.998 | 790.758 | 880.792 |

| Prediction

model | 210.889 | 251.080 | 257.632 |

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that although motor

performance improvement is feasible in patients with chronic

stroke, it is not universally achievable. Among the 14

participants, only three attained clinically meaningful gains in

the FMA-UE scale, whilst two showed improvements in gross dexterity

(BBT) and seven in grip strength (Force). This variability in

outcomes aligns with prior evidence suggesting that chronic stroke

recovery is contingent on the interplay among residual brain

plasticity, lesion characteristics, and rehabilitation intensity

(4,38,39).

The motor scales used capture distinct facets of

recovery, each associated with specific neural parameters. The

FMA-UE, which evaluates sensorimotor coordination and selective

movement, primarily reflects the integrity of the ipsilesional

corticospinal tract and functional reorganization within the

primary motor and premotor cortices (40-42).

These regions are critical for precision and voluntary control. By

contrast, the BBT, assessing gross manual dexterity and speed,

mainly engages cerebellar-thalamocortical circuits and bilateral

premotor areas, which support rhythmic, goal-directed movements

(43). Finally, grip strength

(Force), a measure of maximal voluntary contraction, relies heavily

on corticospinal tract integrity and motor unit recruitment, which

is primarily modulated by the M1 and spinal cord pathways (41,44).

These theoretical distinctions highlight why the detected recovery

trajectories diverged across scales, since each metric taps into

unique neuroanatomical and functional systems.

The observed lateralization patterns in motor

assessment analysis suggest the task-specific recruitment of motor

networks during the chronic stroke phase. The preservation of

ipsilesional left M1 and cerebellar activation in FMA-UE aligns

with functional reorganization within the spared peri-lesional

circuits, a hallmark of successful motor recovery (45,46).

Conversely, the negative relationship between contralesional PMv/M1

activation and BBT or Force may reflect inefficient recruitment of

non-primary motor regions, consistent with previous studies finding

maladaptive overactivation in contralesional areas during simple

motor tasks (47-49).

The divergent positive association of PMd with both BBT and Force

may point to a region that, when appropriately engaged, supports

motor function. These results emphasize that not all contralesional

activations are equal, whereby the functional role of a region

(such as planning compared with execution) is key to understanding

its impact on motor performance.

Cluster size associations further illuminate neural

efficiency mechanisms. Smaller, focused activations in ipsilesional

SMA and M1 were found to be associated with superior FMA-UE and

Force, suggesting that functional recovery relies on streamlined,

instead of diffuse, engagement of primary motor regions. Ward et

al (50) previously

demonstrated that motor recovery was correlated with

renormalization of activity toward ipsilesional M1 and reduced

diffuse recruitment of non-primary regions, suggesting a shift from

compensatory to more efficient processing. By contrast, larger

clusters in the ipsilesional Cer and contralesional SMA were

associated with poorer performance, potentially reflecting

compensatory efforts or reduced network specificity. Consistent

with the present findings, previous studies also noted that

cerebellar overactivation may reflect attempts to compensate for

impaired corticocortical or corticostrial connectivity (50-53),

whilst contralesional SMA hyperactivity was associated with poor

motor outcomes in patients with chronic stroke (54). By contrast, the positive role of

ipsilesional SMA suggests activation across motor scales

underscores its importance in motor planning and execution,

corroborating its known involvement in internally guided movements

(55,56).

Diffusion metric findings highlight structural

underpinnings of these functional patterns. Higher FA in

corticospinal tracts and posterior limb of the internal capsule,

markers of white matter integrity, likely facilitate efficient

signal transmission, supporting motor performance (57). However, increased FA in posterior

corona radiata, a region integrating sensorimotor fibers, may

disrupt feedback loops critical for motor control or it could

reflect maladaptive tissue reorganization, such as gliosis scarring

(58). These results extend

current models, by integrating functional reorganization with

structural connectivity, proposing that both focused ipsilesional

activation and preserved white matter integrity are pivotal for

optimal motor function.

The overall pattern of associations underscores the

importance of lateralized, focused recruitment within the

ipsilesional hemisphere for achieving improvements in upper-limb

function. Positive association of left M1 with Δ(FMA-UE) suggest

that re-engagement of the primary motor area on the stroke-affected

side can facilitate fine motor control, consistent with motor

assessment evidence that normalization of ipsilesional activity is

beneficial (59). In addition, the

mixture of positive and negative associations within ipsilesional

premotor and sensory cortices indicates that excessive or diffuse

engagement of these secondary areas may not always be adaptive.

These findings collectively suggest that whilst SMA overactivation

may reflect inefficient compensation, as previously observed in

studies linking diffuse recruitment during poorly performed tasks

to maladaptive neural resource allocation (60,61),

PMv engagement represents a more targeted adaptive mechanism for

motor recovery. This aligns with its role in higher-order motor

planning and bilateral coordination, demonstrated in previous

studies where preserved PMv activity supported grasp posture

encoding and compensated for compromised primary motor pathways

(62).

Contralesional recruitment emerged as variably

supportive. Although positive association in the right PMd aligned

with prior reports of an ancillary contribution from premotor

regions in the unaffected hemisphere (63,64),

negative association in right PMv and positive ones in right SMA

suggest that each contralesional region may differentially

influence distinct facets of motor recovery. The fact that right

somatosensory cortex activation is positively associated with

changes in gross dexterity suggests that contralesional sensory

processing can aid performance when ipsilesional pathways are

compromised, but such recruitment may be less crucial for fine

motor tasks (65,66).

White matter diffusion metrics corroborated these

aforementioned functional observations, showing that the structural

integrity of critical descending pathways (corticospinal tract,

internal capsule) may have different impact on fine compared with

gross motor recovery. Negative associations of FA in the cerebral

peduncle and posterior limb of the internal capsule with Δ(FMA-UE),

and a negative association of FA in the posterior limb of the

internal capsule with Δ(Force), but positive ones for Δ(BBT),

suggest that microstructural reorganization in these tracts may

support certain compensatory strategies (such as improved motor

speed or gross upper-limb function) at the expense of refined

upper-limb coordination (67). By

contrast, the positive association of FA in the posterior corona

radiata with Δ(FMA-UE), a measure of fine motor recovery, suggests

that diffuse connectivity changes in this region may selectively

enhance sensorimotor integration, which is critical for tasks

requiring refined coordination (including finger individuation or

selective movement) (68). This

aligns with the posterior corona radiata's role in integrating

corticopontine and associative fibers that facilitate cross-modal

connectivity between sensory feedback and motor planning (69). However, the negative associations

of posterior corona radiata FA with Δ(BBT) and Δ(Force), which are

measures of gross dexterity and strength, indicate that diffuse

reorganization here may divert resources from task-specific

corticospinal pathways, which are more directly involved in force

generation and rhythmic movements (70). Therefore, the inverse associations

of FA in the posterior corona radiata with Δ(FMA-UE) compared with

Δ(BBT) may seem contradictory. However, this likely reflects the

dual role of this region in integrating sensory and motor signals.

Higher FA in this area may facilitate fine motor coordination (such

as finger individuation), supporting improvements in FMA-UE, whilst

potentially disrupting the streamlined corticospinal output

necessary for gross dexterity tasks, such as the BBT. These

findings underscore the importance of interpreting diffusion

metrics within the specific motor domains they influence.

Taken together, these findings highlight a dynamic

interplay between lateralized, focused activation of ipsilesional

motor regions and selective recruitment of contralesional premotor

and sensory areas, all modulated by the structural state of

relevant white matter tracts. Although contralesional engagement

can provide some compensatory support, particularly in sensory

processing or force production, sustained gains in upper-limb

function appear most strongly associated with ipsilesional

reactivation. Future rehabilitation strategies may therefore focus

on facilitating the targeted activation of ipsilesional M1 and

optimizing microstructural integrity in key motor pathways, whilst

also tailoring contralesional involvement to each patient's

specific deficit profile.

The present study has limitations that warrant

consideration. The small sample size limited statistical power and

generalizability, particularly for outcomes, such as grip strength,

where only a few patients demonstrated measurable improvements.

However, the use of GLMM enhanced statistical robustness by

accounting for repeated measures and within-subject variability. By

excluding individuals with significant cognitive or sensory

impairments, where conditions that can affect ≤50% of chronic

stroke survivors and frequently co-occur with motor deficits, the

present cohort does not fully represent the broader stroke

population observed in clinical practice. Future trials should

include participants with mild to moderate sensory and cognitive

comorbidities to assess the generalizability of the present

neuroimaging biomarkers in real-world settings. The present study

also focused exclusively on patients with left middle cerebral

artery infarcts, which limits the generalizability to other stroke

subtypes and lesion locations. Additionally, the observational

design and absence of a control group constrain causal inference.

Whilst including healthy or mildly impaired controls can introduce

ceiling effects and minimal variability, future studies should

consider matched chronic stroke control groups receiving standard

care as a more appropriate comparator. Finally, neuroimaging data

were acquired at a single institution using a specific robotic and

imaging protocol, which may limit reproducibility across settings.

To address these limitations, future research should recruit larger

and more clinically heterogeneous cohorts, encompass diverse lesion

sites and functional baselines, whilst integrating peripheral

physiological markers (such as electromyography or kinematic

analysis) to refine predictive models and enhance

applicability.

The present study builds upon prior knowledge by

identifying neuroimaging signatures (such as ipsilesional M1

cluster size and posterior corona radiata FA/MD) as potential

biomarkers for predicting response to MRI-compatible robotic

training, offering a bridge between neuroplasticity theories and

device-based rehabilitation outcomes. It refines the understanding

of contralesional contributions, revealing region-specific effects

(adaptive right PMd compared with maladaptive PMv/M1 activation)

that nuance earlier dichotomous interpretations of compensatory

mechanisms (47,49,62).

By mapping motor scales, such as FMA-UE, BBT and Force, to distinct

neural circuits, the present study provides a framework for

interpreting heterogeneous recovery patterns, whilst the inverse

relationship between posterior corona radiata FA and outcomes

challenges assumptions regarding diffuse white matter

reorganization. Methodologically, the integration of real-time

neuroimaging during robotic training and a predictive GLMM

framework offered preliminary tools for patient stratification,

distinguishing efficient, focused ipsilesional reorganization from

maladaptive compensatory recruitment. Although modest in scale,

these findings highlight interactions between structural

connectivity and task-specific functional activation, advancing

precision in post-stroke rehabilitation targeting. They also

indicate that the integration of fMRI and DTI with robotic

rehabilitation provides a novel framework for identifying neural

correlates and predictors of recovery, emphasizing the potential

for personalized therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

The present study was conducted at the Athinoula A.

Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, (Charlestown, USA). The

authors would like to sincerely thank Dr Bruce R. Rosen, Director

of the Athinoula A. Martinos Center, for providing access to the

center, and the center's staff, for their technical assistance with

scanning procedures. The authors are also especially grateful to Dr

Mark P. Ottensmeyer, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General

Research Institute (Boston, USA) for his invaluable contributions

in developing and maintaining the robotic device throughout the

study.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by a grant from the

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant no.

1R01NS105875-01A1) of the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MM and LGA analyzed the data and prepared the

manuscript. SE selected and trained the patients, collected and

curated the data. AAT designed the study. SE and AAT confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Institutional review board approval of the study was

granted by the Partners Human Research Committee (approval no.

2005P000570) serving Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, USA)

and all participants provided informed consent for participation in

the study, including data collection, anonymized data analysis, and

publication of the results.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Baricich A and Carda S: Chronic stroke: An

oxymoron or a challenge for rehabilitation? Funct Neurol.

33:123–124. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Herpich F and Rincon F: Management of

acute ischemic stroke. Crit Care Med. 48:1654–1663. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Solomonow-Avnon D and Mawase F: The dose

and intensity matter for chronic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 90:1187–1188. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Carson RG: The physiology of stroke

neurorehabilitation. J Physiol. 603:611–615. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Teasell RW, Murie Fernandez M, McIntyre A

and Mehta S: Rethinking the continuum of stroke rehabilitation.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 95:595–596. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Paolucci T, Agostini F, Mussomeli E,

Cazzolla S, Conti M, Sarno F, Bernetti A, Paoloni M and Mangone M:

A rehabilitative approach beyond the acute stroke event: A scoping

review about functional recovery perspectives in the chronic

hemiplegic patient. Front Neurol. 14(1234205)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Campos B, Choi H, DeMarco AT,

Seydell-Greenwald A, Hussain SJ, Joy MT, Turkeltaub PE and Zeiger

W: Rethinking remapping: Circuit mechanisms of recovery after

stroke. J Neurosci. 43:7489–7500. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Garraway WM, Akhtar AJ, Smith DL and Smith

ME: The triage of stroke rehabilitation. J Epidemiol Community

Health. 35:39–44. 1981.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Miller EL, Murray L, Richards L, Zorowitz

RD, Bakas T, Clark P and Billinger SA: American Heart Association

Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and the Stroke Council.

Comprehensive overview of nursing and interdisciplinary

rehabilitation care of the stroke patient: A scientific statement

from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 41:2402–2448.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sackley CM and Gladman JRF: The evidence

for rehabilitation after severely disabling stroke. Phys Ther Rev.

3:19–29. 1998.

|

|

11

|

Włodarczyk L, Cichon N, Saluk-Bijak J,

Bijak M, Majos A and Miller E: Neuroimaging techniques as potential

tools for assessment of angiogenesis and neuroplasticity processes

after stroke and their clinical implications for rehabilitation and

stroke recovery prognosis. J Clin Med. 11(2473)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Stinear CM and Ward NS: How useful is

imaging in predicting outcomes in stroke rehabilitation? Int J

Stroke. 8:33–37. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gale SD and Pearson CM: Neuroimaging

predictors of stroke outcome: Implications for neurorehabilitation.

NeuroRehabilitation. 31:331–344. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gaviria E and Eltayeb Hamid AH:

Neuroimaging biomarkers for predicting stroke outcomes: A

systematic review. Health Sci Rep. 7(e2221)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hong KY, Kamaldin N, Jeong HL, Nasrallah

FA, Goh JCH and Chen-Hua Y: A magnetic resonance compatible soft

wearable robotic glove for hand rehabilitation and brain imaging.

IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 25:782–793. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Khanicheh A, Mintzopoulos D, Weinberg B,

Tzika AA and Mavroidis C: MR_CHIROD v.2: Magnetic resonance

compatible smart hand rehabilitation device for brain imaging. IEEE

Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 16:91–98. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Khanicheh A, Muto A, Triantafyllou C,

Weinberg B, Astrakas L, Tzika A and Mavroidis C: fMRI-compatible

rehabilitation hand device. J Neuroeng Rehabil.

3(24)2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sharini H, Riyahi Alam N, Khabiri H,

Arabalibeik H, Hashemi H, Azimi AR and Masjoodi S: Novel

FMRI-Compatible wrist robotic device for brain activation

assessment during rehabilitation exercise. Med Eng Phys.

83:112–122. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Astrakas LG, Naqvi SHA, Kateb B and Tzika

AA: Functional MRI using robotic MRI compatible devices for

monitoring rehabilitation from chronic stroke in the molecular

medicine era (Review). Int J Mol Med. 29:963–973. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mintzopoulos D, Khanicheh A, Konstas AA,

Astrakas LG, Singhal AB, Moskowitz MA, Rosen BR and Tzika AA:

Functional MRI of rehabilitation in chronic stroke patients using

novel MR-Compatible hand robots. Open Neuroimag J. 2:94–101.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Jo S, Song Y, Lee Y, Heo SH, Jang SJ, Kim

Y, Shin JH, Jeong J and Park HS: Functional MRI assessment of brain

activity during hand rehabilitation with an MR-Compatible soft

glove in chronic stroke patients: A preliminary study. IEEE Int

Conf Rehabil Robot. 2023:1–6. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Mintzopoulos D, Astrakas LG, Khanicheh A,

Konstas AA, Singhal A, Moskowitz MA, Rosen BR and Tzika AA:

Connectivity alterations assessed by combining fMRI and

MR-compatible hand robots in chronic stroke. NeuroImage. 47 (Suppl

2):T90–T97. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Oldfield RC: The assessment and analysis

of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 9:97–113.

1971.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

London Medical Research Council: Aids to

the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System. Her Majesty's

Stationery Office, London, 1976.

|

|

25

|

Astrakas LG, De Novi G, Ottensmeyer MP,

Pusatere C, Li S, Moskowitz MA and Tzika AA: Improving motor

function after chronic stroke by interactive gaming with a

redesigned MR-compatible hand training device. Exp Ther Med.

21(245)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, Leyman I, Olsson

S and Steglind S: The Post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method

for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med.

7:13–31. 1975.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lyle RC: A performance test for assessment

of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and

research. Int J Rehabil Res. 4:483–492. 1981.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bohannon RW and Smith MB: Interrater

reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys

Ther. 67:206–207. 1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mathiowetz V, Volland G, Kashman N and

Weber K: Adult norms for the box and block test of manual

dexterity. Am J Occup Ther. 39:386–391. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, Fox P,

Lancaster J, Zilles K, Woods R, Paus T, Simpson G, Pike B, et al: A

probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain:

International consortium for brain mapping (ICBM). Philos Trans R

Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 356:1293–1322. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Mayka MA, Corcos DM, Leurgans SE and

Vaillancourt DE: Three-dimensional locations and boundaries of

motor and premotor cortices as defined by functional brain imaging:

A meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 31:1453–1474. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wakana MS, Nagae-Poetscher LM, van Zijl

PCM and Crain B: MRI Atlas of Human White Matter. 1st edition.

Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005.

|

|

33

|

Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, Geange SW,

Poulsen JR, Stevens MHH and White J-SS: Generalized linear mixed

models: A practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol

Evol. 24:127–135. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

White H: A Heteroskedasticity-consistent

covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for

heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 48:817–838. 1980.

|

|

35

|

Woytowicz EJ, Rietschel JC, Goodman RN,

Conroy SS, Sorkin JD, Whitall J and Waller SM: Determining levels

of upper extremity movement impairment by applying a cluster

analysis to the Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity in

Chronic Stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 98:456–462. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Page SJ, Fulk GD and Boyne P: Clinically

important differences for the Upper-extremity Fugl-meyer scale in

people with minimal to moderate impairment due to chronic stroke.

Phys Ther. 92:791–798. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Chen HM, Chen CC, Hsueh IP, Huang SL and

Hsieh CL: Test-retest reproducibility and smallest real difference

of 5 hand function tests in patients with stroke. Neurorehabil

Neural Repair. 23:435–440. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Teasell R, Bayona N, Salter K, Hellings C

and Bitensky J: Progress in clinical neurosciences: Stroke recovery

and rehabilitation. Can J Neurol Sci. 33:357–364. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Miltner WHR: Plasticity and reorganization

in the rehabilitation of stroke. Zeitschrift für Psychologie.

224:91–101. 2016.

|

|

40

|

Fan Y, Lin K, Liu H, Chen Y and Wu C:

Changes in structural integrity are correlated with motor and

functional recovery after post-stroke rehabilitation. Restor Neurol

Neurosci. 33:835–844. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Schulz R, Park CH, Boudrias MH, Gerloff C,

Hummel FC and Ward NS: Assessing the integrity of corticospinal

pathways from primary and secondary cortical motor areas after

stroke. Stroke. 43:2248–2251. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Saini M, Singh N, Kumar N, Srivastava MVP

and Mehndiratta A: A novel perspective of associativity of upper

limb motor impairment and cortical excitability in sub-acute and

chronic stroke. Front Neurosci. 16(832121)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Debaere F, Wenderoth N, Sunaert S, Van

Hecke P and Swinnen SP: Cerebellar and premotor function in

bimanual coordination: Parametric neural responses to

spatiotemporal complexity and cycling frequency. Neuroimage.

21:1416–1427. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ward NS, Newton JM, Swayne OB, Lee L,

Frackowiak RS, Thompson AJ, Greenwood RJ and Rothwell JC: The

relationship between brain activity and peak grip force is

modulated by corticospinal system integrity after subcortical

stroke. Eur J Neurosci. 25:1865–1873. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Favre I, Zeffiro TA, Detante O, Krainik A,

Hommel M and Jaillard A: Upper limb recovery after stroke is

associated with ipsilesional primary motor cortical activity.

Stroke. 45:1077–1083. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Dong Y, Winstein CJ, Albistegui-DuBois R

and Dobkin BH: Evolution of FMRI activation in the perilesional

primary motor cortex and cerebellum with rehabilitation

training-related motor gains after stroke: A pilot study.

Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 21:412–428. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ and

Frackowiak RSJ: The influence of time after stroke on brain

activations during a motor task. Ann Neurol. 55:829–834.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Calautti C, Naccarato M, Jones PS, Sharma

N, Day DD, Carpenter AT, Bullmore ET, Warburton EA and Baron JC:

The relationship between motor deficit and hemisphere activation

balance after stroke: A 3T fMRI study. Neuroimage. 34:322–331.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Braaß H, Feldheim J, Chu Y, Tinnermann A,

Finsterbusch J, Büchel C, Schulz R and Gerloff C: Association

between activity in the ventral premotor cortex and spinal cord

activation during force generation-A combined cortico-spinal fMRI

study. Hum Brain Mapp. 44:6471–6483. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ and

Frackowiak RSJ: Neural correlates of motor recovery after stroke: A

longitudinal fMRI study. Brain. 126:2476–2496. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Calautti C and Baron JC: Functional

neuroimaging studies of motor recovery after stroke in adults: A

review. Stroke. 34:1553–1566. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Feydy A, Carlier R, Roby-Brami A, Bussel

B, Cazalis F, Pierot L, Burnod Y and Maier MA: Longitudinal study

of motor recovery after stroke: Recruitment and focusing of brain

activation. Stroke. 33:1610–1617. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang Z and Wang L, Gao F, Dai Y, Liu C, Wu

J, Wang M, Yan Q, Chen Y, Wang C and Wang L: Exploring cerebellar

transcranial magnetic stimulation in Post-stroke limb dysfunction

rehabilitation: A narrative review. Front Neurosci.

19(1405637)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Wong WW, Chan ST, Tang KW, Meng F and Tong

KY: Neural correlates of motor impairment during motor imagery and

motor execution in Sub-cortical stroke. Brain Injury. 27:651–663.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Loubinoux I, Carel C, Pariente J,

Dechaumont S, Albucher JF, Marque P, Manelfe C and Chollet F:

Correlation between cerebral reorganization and motor recovery