Introduction

The most common arrhythmia is atrial fibrillation

(AF), which can increase certain morbidities, such as heart failure

and stroke, and also increase mortality rates, due to stroke and

other cardiovascular diseases (1,2). The

incidence and prevalence of AF in the elderly has increased

significantly from 2004-2016. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation

was 0.95%, and the incidence of AF ranges between 0.21 and 0.41 per

1,000 person/years in the elderly over 70 years or older (3,4). As

common triggers of AF have been observed to be originated from

pulmonary veins, and pulmonary vein (PV) isolation (PVI) with

catheter ablation has been established as an effective treatment

for AF and is recommended by current guidelines (1,3).

With the aging of the general population, more

elderly people need to receive catheter ablation for AF. The

elderly population are more likely to be diagnosed with coronary

artery disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke, a higher

risk of thrombo-embolic events, renal insufficiency and other

chronic diseases, which can greatly increase the incidence of

intraoperative complications (4).

Additionally, catheter ablation for AF and long operation and

sedation time increases the incidence of intraoperative

complications in the elderly (5).

The relatively simple learning curve of cryoballoon ablation and

short intraoperative operation time associated with this treatment,

may be more suitable for the treatment of AF in the elderly.

Studies have confirmed that cryoballoon ablation had

comparable efficacy compared with catheter ablation (4,5). The

success rate of catheter ablation in elderly patients with AF has

been revealed to be promising in several studies (6,7).

Although there have been some studies on cryoballoon

ablation in elderly patients with AF, most studies lacked

controlled studies with young people and the number of included

cases was small (8,9), to the best of the authors' knowledge,

there has been no systematic review or meta-analysis on this

subject. Therefore, it was decided to perform a systematic review

and meta-analysis on this important subject.

Materials and methods

Protocol

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

and Meta-Analyses guidelines were used in conducting the review

(10).

Data sources and literature

search

A total of four databases (PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, Embase

https://www.embase.com/, Cochrane Library

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/ and Web

of Science https://www.webofscience.com/) were searched until

February 2023. A comprehensive search was performed to identify

published articles or studies on the efficacy and safety of

cryoballoon ablation in elderly patients with AF (such as procedure

time, fluoroscopy time, success rate and complications). Medical

Subject Heading terms were used in PubMed, EMTREE terms in Embase,

and keyword search terms for cryoballoon ablation, elderly and

atrial fibrillation were used in all four databases with the use of

following search terms as single or complex terms in titles,

abstracts and keywords: (aged OR elderly OR aged 80 and over OR

oldest old OR centenarian OR supercentenarian OR

semi-supercentenarians OR octogenarian OR nonagenarian) AND

(cryoablation OR cryoballoon OR cryosurgery) AND (atrial

fibrillation OR auricular fibrillation OR persistent Atrial

Fibrillation OR familial Atrial Fibrillation OR paroxysmal Atrial

Fibrillation). No language limitations were applied.

Study selection and inclusion

criteria

All articles were screened independently by two

reviewers according to the following inclusion criteria: i)

Full-text and relevant data could be acquired; ii) controlled

clinical trials involving cryoballoon ablation; iii) comparing

efficacy and safety of cryoballoon ablation in the elderly and the

young population; iv) minimum follow-up time of 12 months.

Articles such as reviews, abstracts or summaries

presented in meetings were excluded. Disagreements between

reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment and data

extraction

Data of study characteristics such as sample size,

follow-up period, age and sex were independently extracted by the

two reviewers according to the predefined protocol. The quality of

the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

(NOS) for observational studies (7). Studies were scored according to

selection of study groups (four points), comparability of groups

(two points), and ascertainment of exposure and outcomes (three

points) for case-control and cohort studies.

Statistical analysis

Stata (version 14.0; StataCorp LLC) was used to

perform the primary statistical analyses. Data are presented as the

mean difference and were pooled using the inverse variance for

continuous outcome measures. For dichotomous outcomes, data are

presented as the odds ratio (OR) and were pooled using the

Mantel-Haenszel random effects model. The 95% CI was used to

express procedural and long-term outcomes of the two groups,

respectively. Heterogeneity was quantified using I2.

Random effect models were applied to assess the

studies regardless of the heterogeneity (I2). P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Search results

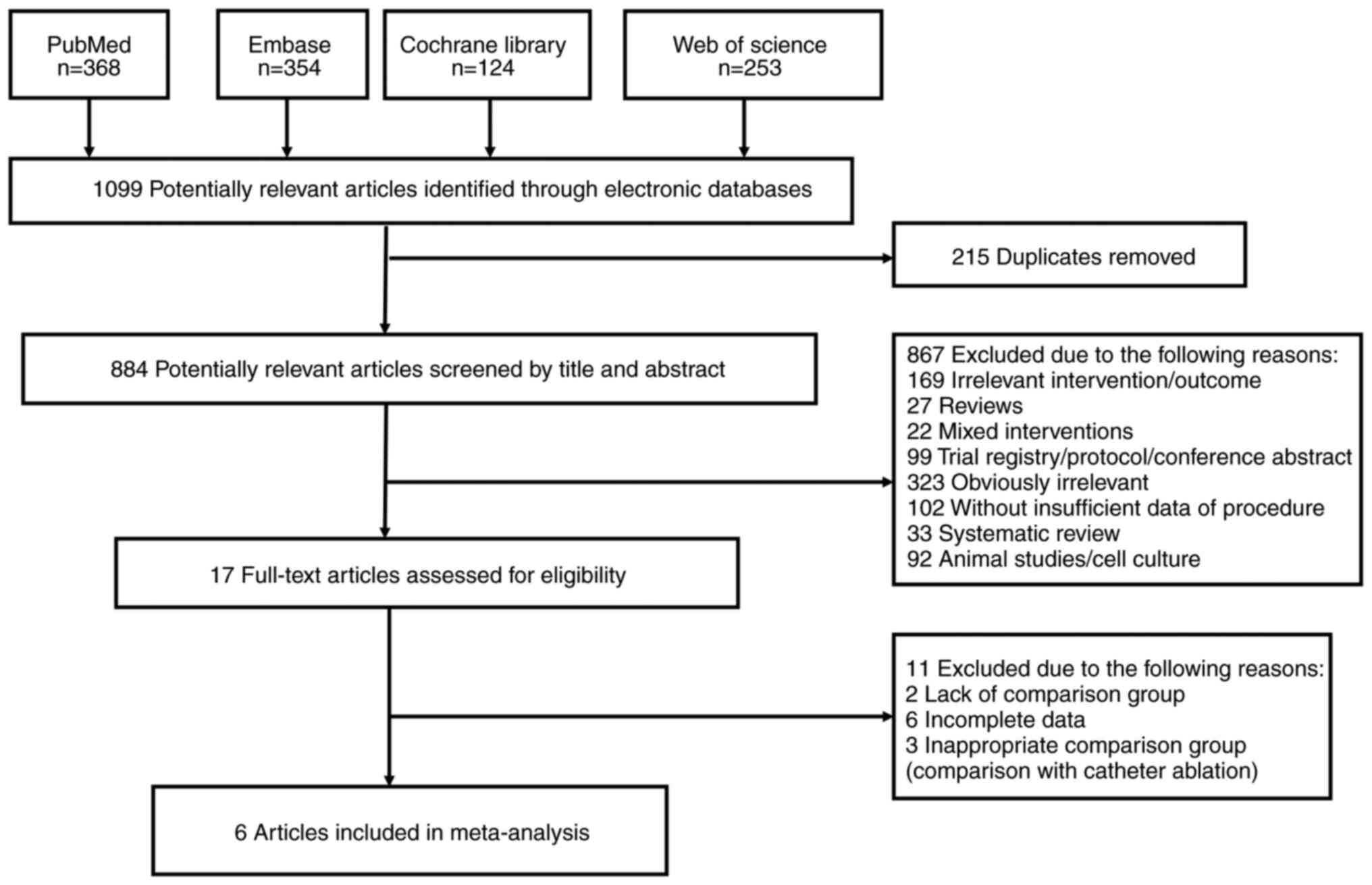

Based on the search strategy, 1,099 studies were

identified in the Cochrane library, Embase, PubMed and Web of

Science databases. Finally, six studies (8-13)

that met the inclusion criteria were identified (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included

studies and quality assessment

The characteristics of the included studies are

shown in Table I. Studies were

performed in Germany (n=3), Italy (n=1), China (n=1), Belgium (n=1)

and Japan (n=1). Most trials were single-center studies (n=4) and

all the included trials (n=6) were of high quality (NOS score of

8-9). Of the six studies, five (12-16)

included elderly patients ≥75 years old, but one (17) included elderly patients ≥80 years

old. The follow-up time was 12 months for five studies and 11.8±5.4

months for one study. Two studies included patients with paroxysmal

AF only (Table I).

| Table ICharacteristics of trials included in

the meta-analysis. |

Table I

Characteristics of trials included in

the meta-analysis.

| | Sample size | |

|---|

| First author/s,

year | Country | Type | Age of elderly

group, years | Elderly group,

n | Control group,

n | Follow-up,

months | PAF, n (%) | NOS score | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Abdin et al,

2019 | Germany | Single-center,

controlled | ≥75 | 55 | 183 | 11.8±5.4 | 91 (38.2) | 8 | (16) |

| Abugattas et

al, 2017 | Belgium and

Italy | Two-center,

controlled | ≥75 | 53 | 106 | 12 | 159(100) | 8 | (15) |

| Heeger et

al, 2019 | Germany | Multi-center,

controlled | ≥75 | 104 | 104 | 12 | 119 (57.2) | 9 | (14) |

| Kanda et al,

2019 | Japan | Single-center,

controlled | ≥80 | 49 | 241 | 12 | 290(100) | 8 | (17) |

| Tscholl et

al, 2018 | Germany | Single-center,

controlled | ≥75 | 40 | 40 | 12 | 37 (46.25) | 9 | (12) |

| Zhang et al,

2019 | China | Single-center,

controlled | ≥75 | 127 | 550 | 12 | 603 (89.1) | 8 | (14) |

A total of 1,652 patients (936 male patients;

56.66%) were enrolled in the studies (428 patients in the elderly

group and 1,224 patients in the control group), with a mean age of

66.61 years. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 60.4%

(Table II). The left atrial size

was not significantly different between the two groups (42 mm in

the elderly group compared with 41 mm in the young group;

P=0.58).

| Table IIBaseline characteristics of the

included studies. |

Table II

Baseline characteristics of the

included studies.

| | Age, years | P-value | Male patients,

n | P-value | LVEF, % | P-value | CHA2DS2-vasc | P-value | HASBLED | P-value | LA diameter,

mm | P-value | |

|---|

| First author/s,

year | Elderly | Control | <0.01 | Elderly | Control | <0.01 | Elderly | Control | 0<0.01 | Elderly | Control | 0<0.01 | Elderly | Control | <0.01 | Elderly | Control | 0.58 | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Abdin et al,

2019 | 78± 2.8 | 60.8± 9.5 | <0.01 | 25 | 120 | <0.01 | 51.6± 8.3 | 52.5± 8.0 | 0.47 | 4.0± 1.3 | 2.0± 1.3 | <0.01 | 2.2± 0.89 | 1.2± 0.97 | <0.01 | 40.9± 5.5 | 40.8± 6.6 | 0.92 | (16) |

| Abugattas et

al, 2017 | 78.19± 2.7 | 58.97± 8.5 | <0.01 | 24 | 62 | 0.12 | 59.2± 5.2 | 59.9± 6.4 | 0.49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 41.4± 7.2 | 40.9± 6.6 | 0.66 | (15) |

| Heeger et

al, 2019 | 77.5± 3.7 | 63± 13.3 | <0.01 | 52 | 54 | 0.78 | NA | NA | NA | 3.8± 1.1 | 2.1± 1.3 | <0.01 | NA | NA | NA | 44.5± 5.6 | 44.5± 5.6 | >0.99 | (14) |

| Kanda et al,

2019 | 84±3 | 66±10 | <0.01 | 24 | 145 | 0.15 | 66±10 | 65±10 | 0.52 | 3.8±0.9 | 2.2±1.4 | <0.01 | NA | NA | NA | 40±6 | 38±6 | 0.03 | (17) |

| Tscholl et

al, 2018 | 77.0± 2.2 | 65.5± 9.4 | <0.01 | 20 | 26 | 0.17 | 63±4.4 | 65±7.4 | 0.15 | 4±0.74 | 2±1.48 | <0.01 | 2±0.74 | 2±1.48 | >0.99 | NA | NA | | (12) |

| Zhang et al,

2019 | 79.2± 3.1 | 63.8± 7.6 | <0.01 | 57 | 327 | <0.01 | 58.7± 9.0 | 61.5± 6.5 | 0 | 4.8±1.6 | 2.6± 1.7 | <0.01 | 2.0±0.8 | 1.8±0.8 | 0.01 | 41.0± 5.3 | 41.3± 5.6 | 0.58 | (13) |

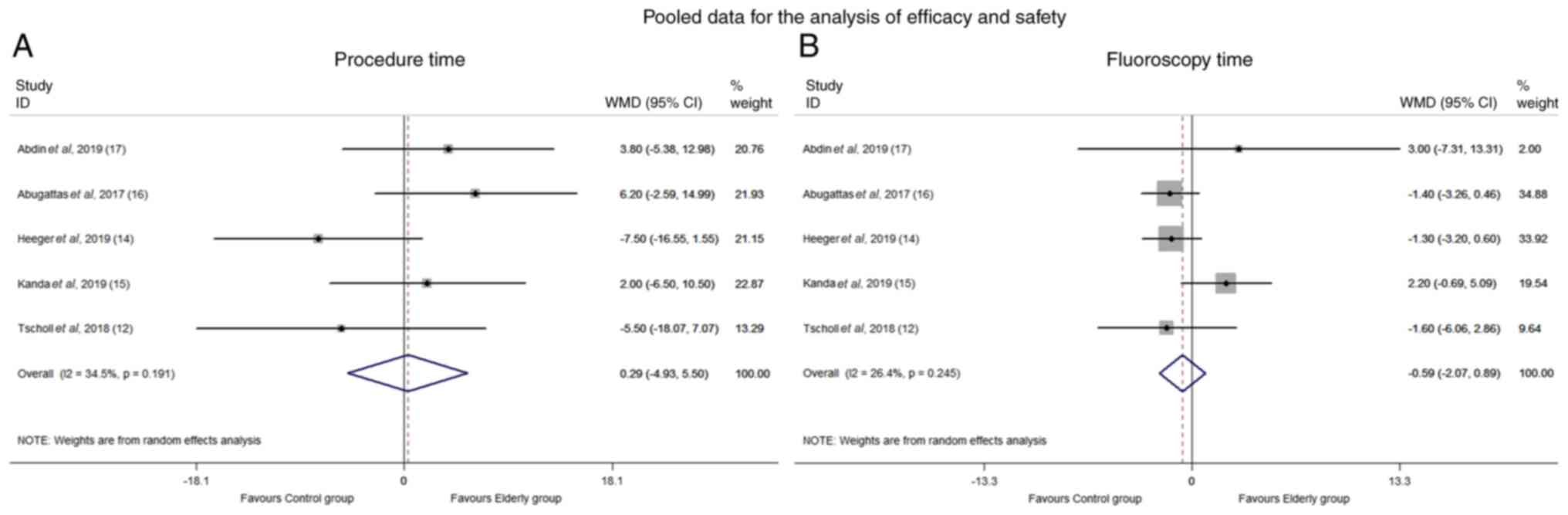

Procedural time

The procedural time was reported in five studies.

The heterogeneity was moderate (I2=34.5%). The

difference in procedural time between the two groups was not

significant (mean difference, 0.29; 95% CI, -4.93 to 5.50; P=0.91;

Fig. 2A).

Fluoroscopy time

The fluoroscopy time was systematically reported in

five studies. There was moderate heterogeneity among these trials

(I2=26.4%). The fluoroscopy time in the elderly group

was not significantly different compared with the younger group

(mean difference, -0.59; 95% CI, -2.07 to 0.89; P=0.43; Fig. 2B).

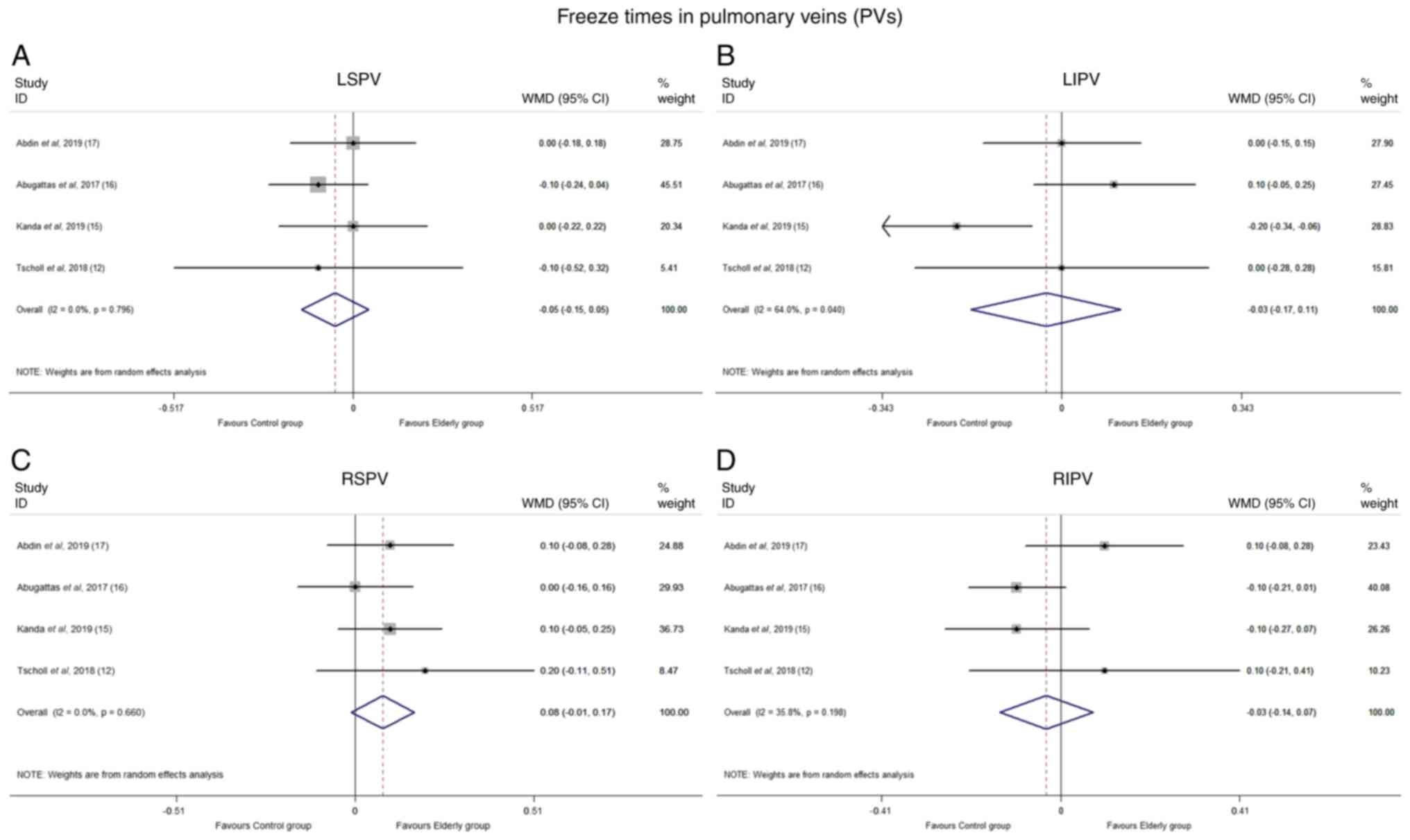

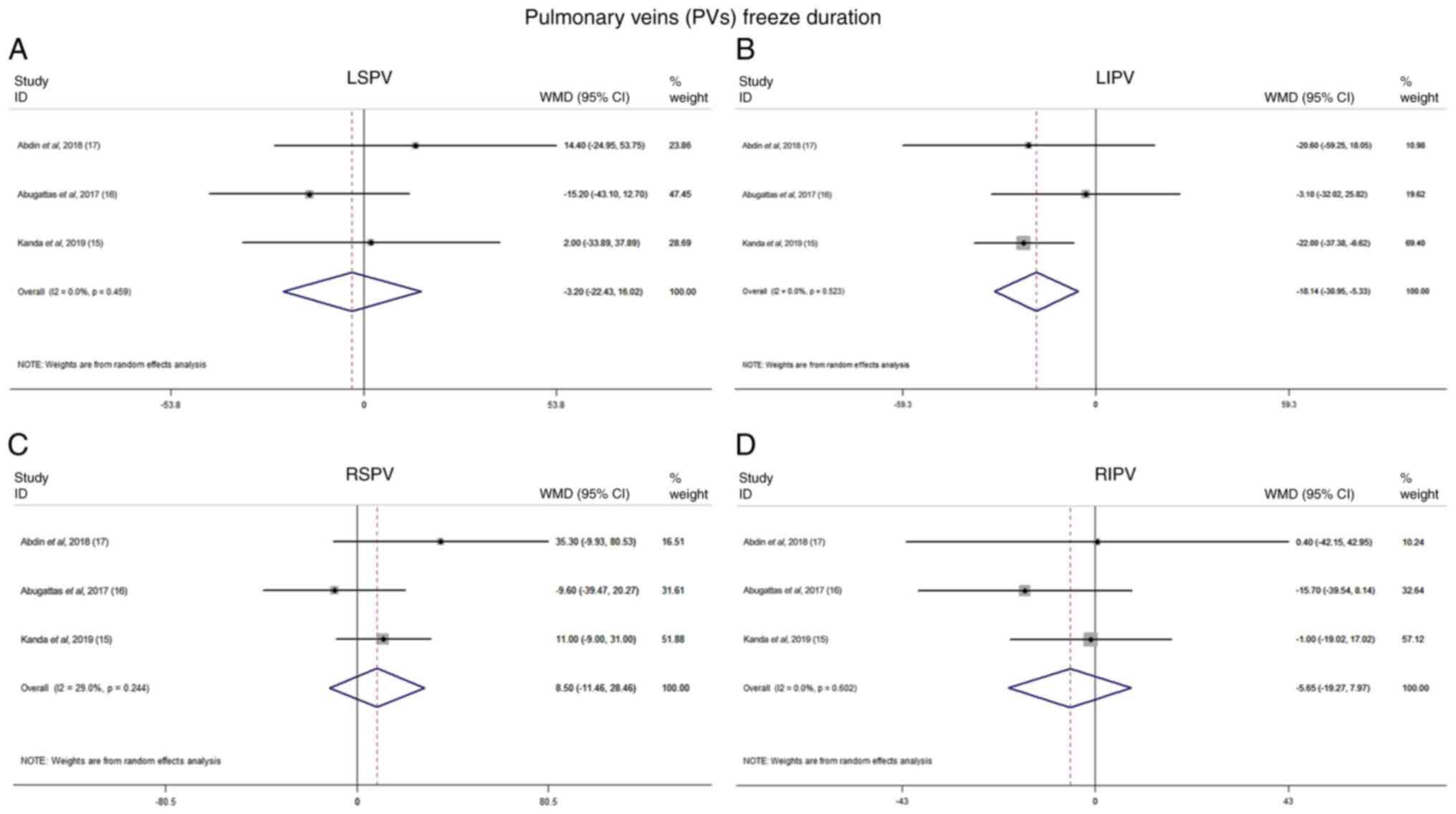

Freeze times in PVs

Data for freeze times in four PVs were available for

four studies (12,15-17).

The I2 index for left superior PVs (LSPVs), left

inferior PVs (LIPVs), right superior PVs (RSPVs) and right inferior

PVs (RIPVs) was 0.0, 64.0, 0.0 and 35.8%, respectively. There was

no significant difference between the elderly and control group in

terms of freeze times of LSPVs (mean difference, -0.051; 95% CI,

-0.148 to 0.046; P=0.303), LIPVs (mean difference, -0.03; 95% CI,

-0.17 to 0.11; P=0.36), RSPVs (mean difference, 0.079; 95% CI,

-0.012 to 0.169; P=0.088) and RIPVs (mean difference, -0.033; 95%

CI, -0.14 to 0.07; P=0.55; Fig.

3). When a sensitivity test was performed, the removal of any

individual study did not affect the point estimate or confidence

interval of the results (data not shown).

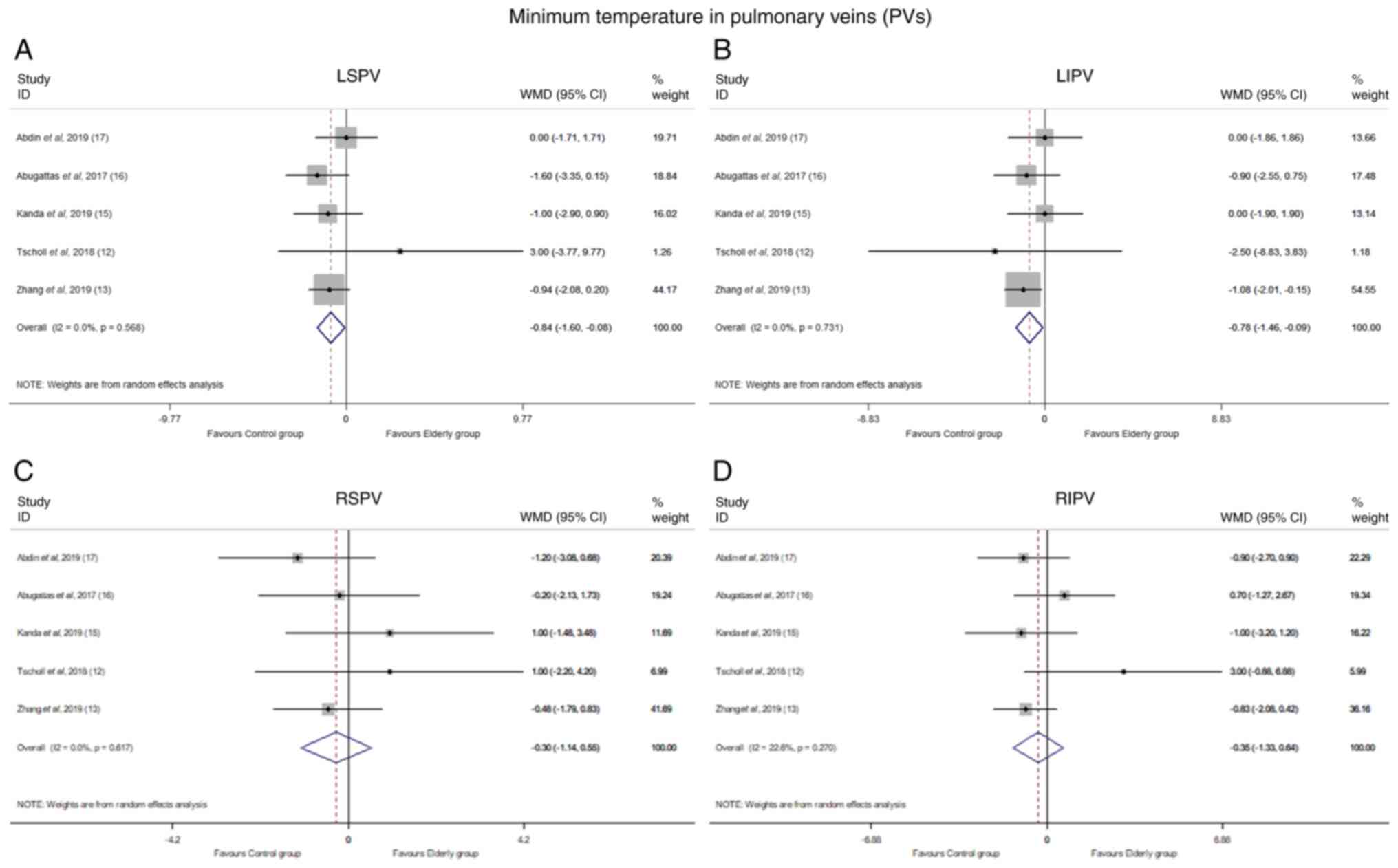

Minimum temperature in PVs

A total of five trials reported the minimum

temperature in PVs during the procedure. Cryoballoon freezing was

associated with a significantly lower temperature in the elderly

compared with the control group during the ablation of LSPVs (mean

difference, -0.84; 95% CI, -1.60 to -0.08; P=0.03) and LIPVs (mean

difference, -0.78; 95% CI, -1.46 to -0.09; P=0.03). In addition,

there was no heterogeneity (I2=0.0%).

There was no significant difference between the two

groups during the cryoablation process of the RSPVs (mean

difference, -0.30; 95% CI, -1.14 to 0.55; P=0.49) and RIPVs (mean

difference, -0.35; 95% CI, -1.33 to 0.64; P=0.49). In addition,

there was no heterogeneity for RSPVs (I2=0.0%) and low

heterogeneity for RIPVs (I2=22.6%) (Fig. 4).

PV freeze duration

Data on PV freeze duration were available for three

studies. There were no significant differences in freeze durations

of LSPVs, RSPVs and RIPVs between the two groups. However, LIPV of

the elderly group was characterized by longer freeze duration (mean

difference, -18.14; 95% CI, -30.95 to -5.33; P=0.006). There was no

heterogeneity between the two groups (I2=0.0%; Fig. 5).

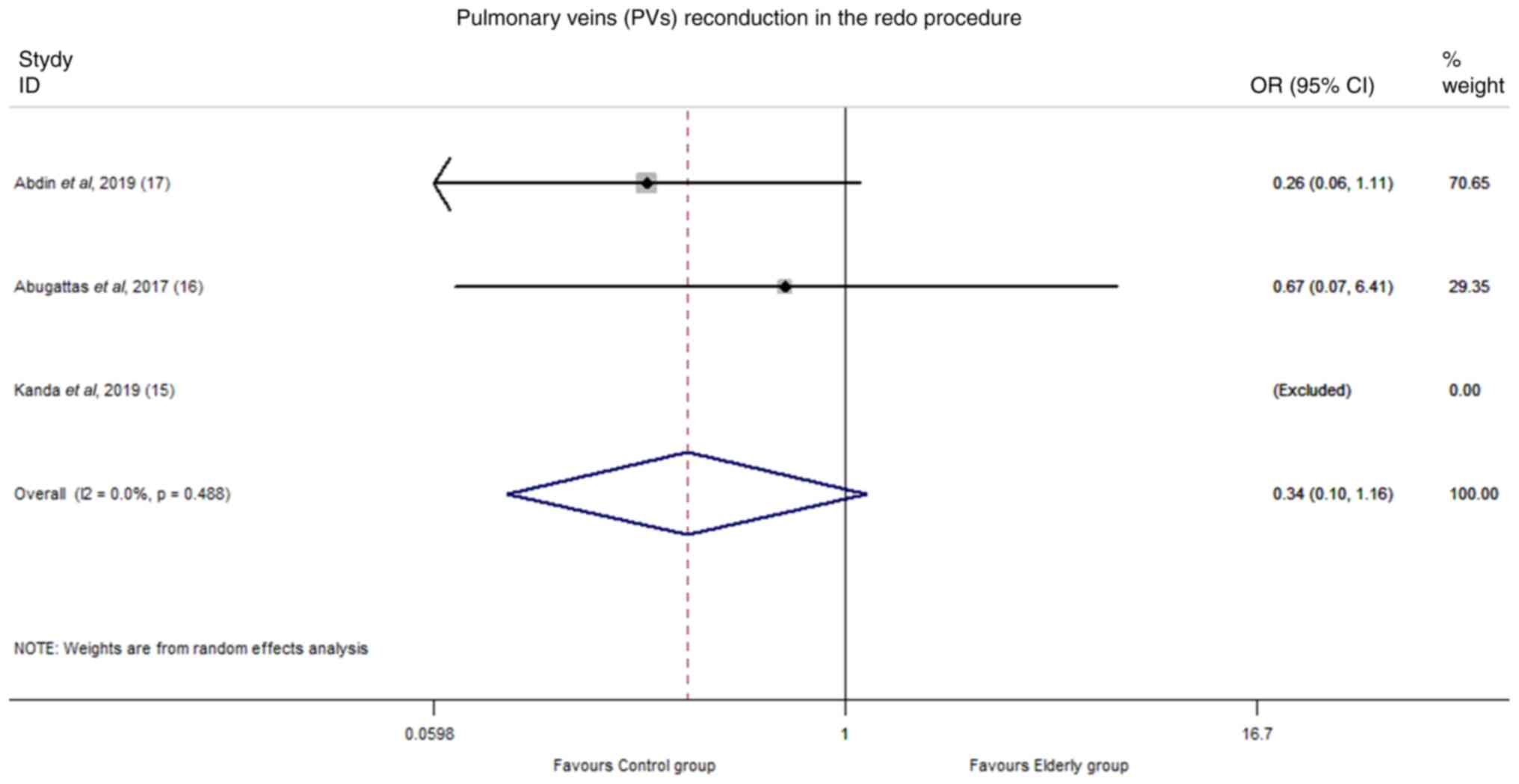

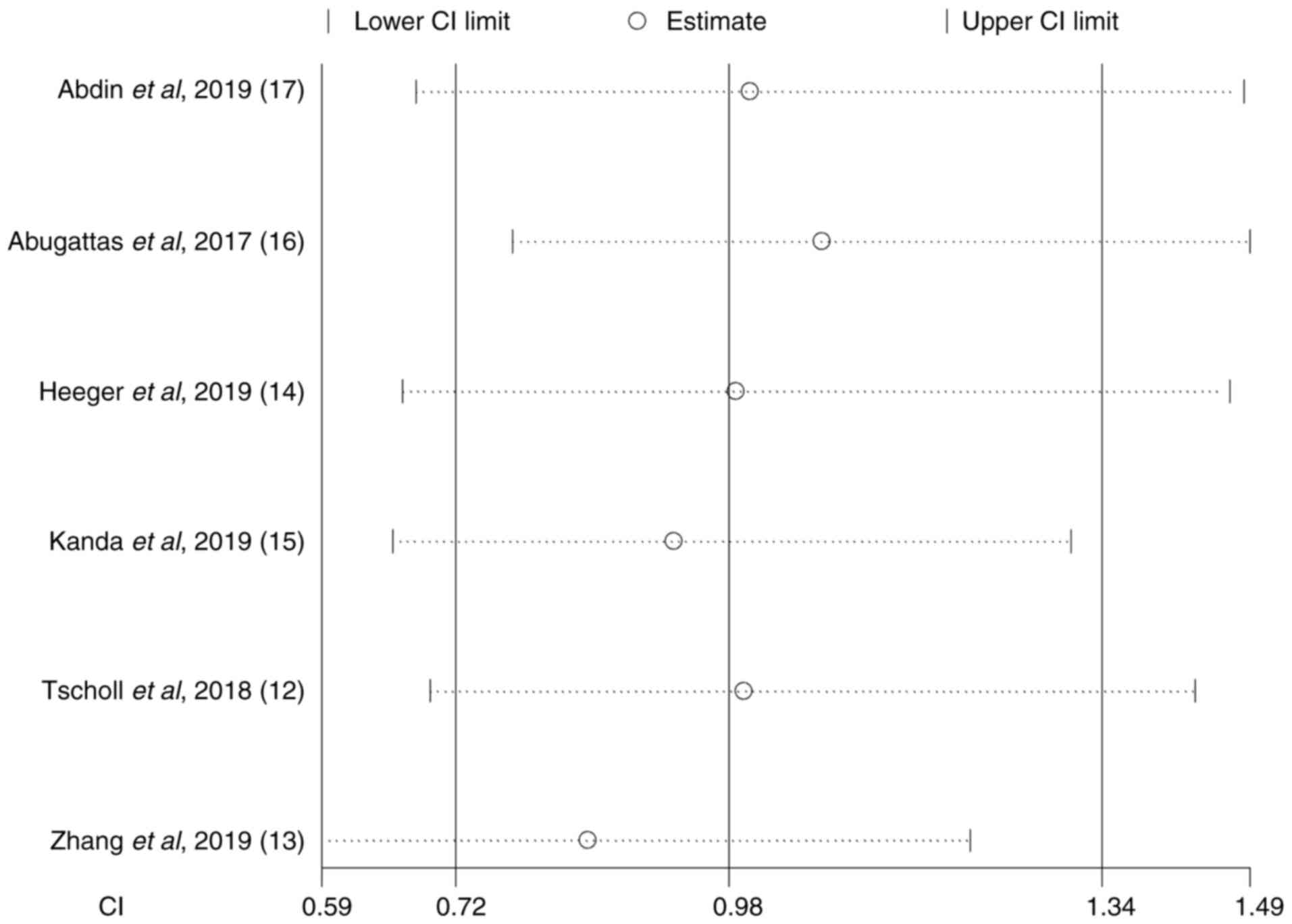

Success rate

All the included studies systematically reported the

success rate. The heterogeneity in both groups was low

(I2=2.1%). There was no difference in the success rate

between the elderly and younger individuals (OR, 0.981; 95% CI,

0.72 to 1.34; P=0.903; Fig.

S1).

In addition, three trials reported the PV

reconduction in the redo procedure. There was no significant

heterogeneity (I2=0.0%). The difference in PV

reconduction between the elderly and control group was not

significant (OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.10 to 1.16; P=0.08; Fig. 6).

Transient phrenic nerve palsy

(tPNP)

The results of tPNP were reported in all included

studies. However, one study (17)

reported tPNP in all patients, and was not included in the

analysis. The heterogeneity was low (I2=0.0%). There was

no difference in the rate of tPNP between the two groups (mean

difference, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.45 to 2.02; P=0.90; Fig. S2). Other complications of the

procedure are shown in Table

III. There was no significant difference between the two

groups.

| Table IIIComplications in the included

studies. |

Table III

Complications in the included

studies.

| | Persistent PNP,

n | Atrio-esophageal

fistula, n | Groin

complications, n | Tamponade, n | Mortality, n | MI, n | Stroke/TIA, n | Pericardial

effusion, n | |

|---|

| First author/s,

year | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | Elderly | Control | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Abdin et al,

2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (16) |

| Abugattas et

al, 2017 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | (15) |

| Heeger et

al, 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | (14) |

| Kanda et al,

2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (17) |

| Tscholl et

al, 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | (12) |

| Zhang et al,

2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | (13) |

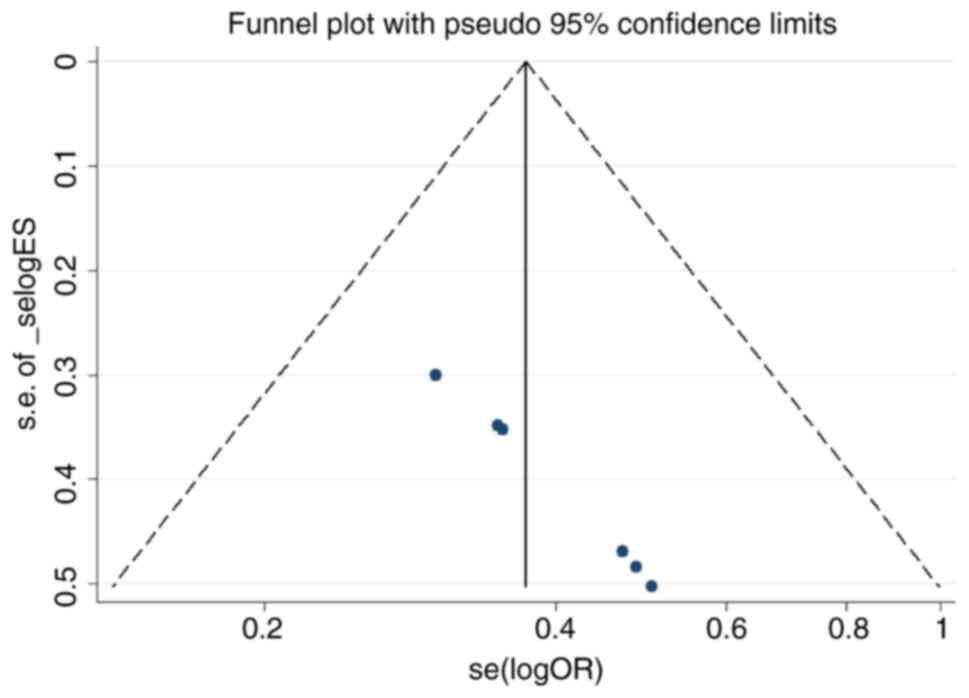

Risk of bias and sensitivity

analysis

All trials included were nonrandomized controlled

studies. A funnel plot of studies including procedural time was

highly symmetrical, six dots were contained in the large triangle

and no evidence of publication bias was identified (Fig. 7). A sensitive analysis showed that

the direction and magnitude of combined estimates of fluoroscopy

time did not vary markedly with the removal of any study,

indicating that the meta-analysis had good reliability and the

results were not overly influenced by each individual study

(Fig. 8). However, it should be

noted that the elderly patients were >80 years old in the study

by Kanda et al (17), while

the patients were >75 years old in the other five studies, which

might be a source of bias.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first meta-analysis to systematically evaluate the efficacy and

safety of the cryoballoon ablation procedure in elderly patients

with AF. The main finding of the present study was that the

cryoballoon ablation procedure was as effective and safe in the

elderly as in the younger patients with AF. Cryoballoon freezing

was associated with a significantly lower temperature in the

elderly compared with the control group during the ablation of

LSPVs.

Since the study by Haïssaguerre et al

(18) reported that triggers from

the PVs initiated AF, PVI has been recommended as the cornerstone

of ablation approaches for the treatment of AF (19). The efficacy and safety have been

uniformly demonstrated in multiple trials (20,21).

At present, it has been shown that cryoablation can have a similar

effect to radiofrequency ablation (4,5). A

number of studies have established that the prognosis of AF is

worse in patients aged ≥75 years, and the rates of mortality and

major adverse cardiac events are higher (22-25).

As the remodeling and fibrosis of the atrium increase with aging,

the success rate of PVI is supposed to be lower in the elderly

population (15). Therefore, a

number of clinical trials, such as the STOP-AF and RAAFT-2 trials,

did not include elderly patients (26,27).

However, some non-randomized clinical trials have reported that the

results of catheter ablation in elderly patients with AF are

promising (28,29). Furthermore, the risk of surgery is

higher due to the poor physical conditions and more complications

in the elderly. Compared with radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation

has a shorter left atrial operation time, which seems to be more

suitable for elderly patients (4,5).

The present meta-analysis focused on a comparison of

cryoablation between older and young adults. The results were

consistent with the observations from the aforementioned studies

(12-17).

In the present study, the procedural data and success rate for the

efficacy analysis were pooled. No significant difference was

observed between the procedural time (mean difference, 0.29; 95%

CI, -4.93 to 5.50; P=0.91; Fig.

2A) and fluoroscopy time (mean difference, -0.59; 95% CI, -2.07

to 0.89; P=0.43; Fig. 2B). No

significant difference was observed for the success rate (OR,

0.981; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.34; P=0.903; Fig. S1).

Generally, it has been assumed that the elderly

cannot endure long operations as can the young, which may affect

the efficacy of the procedure (8,9).

However, there was no difference between the two groups in the

efficacy of the procedure. The cryoballoon ablation procedure takes

a short time, which might be a possible explanation. Freeze times

of PVs could be performed safely in the elderly as with the young.

However, it should be noted that freezing energy could produce a

lower temperature on LSPV and LIPV in the elderly compared with the

control group in the present study. Nevertheless, in the present

study, there was no significant difference between the left

pulmonary veins and right pulmonary veins, although the mechanism

is unclear. In addition, the LIPV freezing time was longer in the

elderly. Therefore, it also suggested that doctors should be more

careful in the process of LPV freezing in the elderly. The

complication rates of the catheter ablation procedure in elderly

patients with AF reported in some trials are inconsistent (30,31).

A number of studies have indicated that the rate of complication of

catheter ablation was higher in elderly patients with AF compared

with the young population (32,33).

Compared with catheter ablation, some studies have reported that

there were fewer serious complications for the cryoballoon ablation

procedure (34,35).

In addition to complications such as pericardial

effusions or tamponades, PV stenosis may occur in rare instances

(36). Phrenic nerve palsy is the

most common complication for the cryoballoon procedure, and can be

prevented by phrenic nerve pacing in the procedure (35). tPNP results were reported by all

the included trials and it was identified that there was no

significant difference in the rate of tPNP between the two groups

(mean difference, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.45 to 2.02; P=0.90) and the

heterogeneity was low. There was no significant difference for

other complications such as atrio-esophageal fistula, tamponade and

mortality (Table III).

Therefore, the incidence of complications of the

cryoballoon procedure in the elderly was similar to that in the

young. The data of some recurrent cases were also analyzed in the

present study. It was found that there was no significant

difference in PV reconduction between the two groups, which further

verified that the effect of cryoablation in the elderly was not

inferior to that in the young.

The trials included in the present meta-analysis

were non-randomized trials, which might cause bias and yield

limited meaningful results. Additionally, more high-quality

randomized controlled trials are required to analyze the efficacy

and safety of cryoballoon ablation in the elderly. Patients aged

>80 years old were included in the Tscholl et al

(12) trial, while patients were

>75 years old in other trials. This could be a source of

heterogeneity. The heterogeneity was low or moderate in the present

study.

In conclusion, cryoballoon ablation was as safe and

effective in elderly patients with AF as in young patients. The

cryoballoon operation of the left pulmonary veins in the elderly

requires more attention.

Supplementary Material

Success rate.

Transient phrenic nerve palsy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by a grant from the

Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no.

ZR2022MH253).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XL and QZ conceived and designed the study. LY, JG

and HBT performed the statistical analysis of the data. XL and JG

drafted and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and edited the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson

A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener HC, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks

J, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial

fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace.

18:1609–1678. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A,

Kronmal R and Hart RG: Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of

patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch

Intern Med. 155:469–473. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y,

Henault LE, Selby JV and Singer DE: Prevalence of diagnosed atrial

fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management

and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and risk factors in

atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA. 285:2370–2375.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zoni-Berisso M, Lercari F, Carazza T and

Domenicucci S: Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: European

perspective. Clin Epidemiol. 6:213–220. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kuck KH, Brugada J, Fürnkranz A, Metzner

A, Ouyang F, Chun KR, Elvan A, Arentz T, Bestehorn K, Pocock SJ, et

al: Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial

fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 374:2235–2245. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lioni L, Letsas KP, Efremidis M, Vlachos

K, Giannopoulos G, Kareliotis V, Deftereos S and Sideris A:

Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in the elderly. J Geriatr

Cardiol. 11:291–295. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kawamura I, Aikawa T, Yokoyama Y, Takagi H

and Kuno T: Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in elderly

patients: Systematic review and a meta-analysis. Pacing Clin

Electrophysiol. 45:59–71. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ikenouchi T, Nitta J, Nitta G, Kato S,

Iwasaki T, Murata K, Junji M, Hirao T, Kanoh M, Takamiya T, et al:

Propensity-matched comparison of cryoballoon and radiofrequency

ablation for atrial fibrillation in elderly patients. Heart Rhythm.

16:838–845. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xing Y, Xu B, Sheng X, Xu C, Peng F, Sun

Y, Wang S and Guo H: Efficacy and safety of uninterrupted

low-intensity warfarin for cryoballoon ablation of atrial

fibrillation in the elderly: A pilot study. J Clin Pharm Ther.

43:401–407. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J and Altman

DG: PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews

and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol.

62:1006–1012. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lo CK, Mertz D and Loeb M:

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing reviewers' to authors'

assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 14(45)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tscholl V, Lin T, Lsharaf AK, Bellmann B,

Nagel P, Lenz K, Landmesser U, Roser M and Rillig A: Cryoballoon

ablation in the elderly: One year outcome and safety of the

second-generation 28 mm cryoballoon in patients over 75 years old.

Europace. 20:772–777. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang J, Ren Z, Wang S, Zhang J, Yang H,

Zheng Y, Meng W, Zhao D and Xu Y: Efficacy and safety of

cryoballoon ablation for Chinese patients over 75 years old: A

comparison with a younger cohort. Journal Of Cardiovascular

Electrophysiology. 30:2734–2742. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Heeger CH, Bellmann B, Fink T, Bohnen JE,

Wissner E, Wohlmuth P, Rottner L, Sohns C, Tilz RR, Mathew S, et

al: Efficacy and safety of cryoballoon ablation in the elderly: A

multicenter study. Int J Cardiol. 278:108–113. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Abugattas JP, Iacopino S, Moran D, De

Regibus V, Takarada K, Mugnai G, Ströker E, Coutiño-Moreno HE,

Choudhury R, Storti C, et al: Efficacy and safety of the second

generation cryoballoon ablation for the treatment of paroxysmal

atrial fibrillation in patients over 75 years: A comparison with a

younger cohort. Europace. 19:1798–1803. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Abdin A, Yalin K, Lyan E, Sawan N, Liosis

S, Meyer-Saraei R, Elsner C, Lange SA, Heeger CH, Eitel C, et al:

Safety and efficacy of cryoballoon ablation for the treatment of

atrial fibrillation in elderly patients. Clin Res Cardiol.

108:167–174. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kanda T, Masuda M, Kurata N, Asai M, Iida

O, Okamoto S, Ishihara T, Nanto K, Tsujimura T, Okuno S, et al:

Efficacy and safety of the cryoballoon-based atrial fibrillation

ablation in patients aged ≥80 years. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.

30:2242–2247. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi

A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Métayer P and

Clémenty J: Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by

ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med.

339:659–666. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, Brugada J,

Camm AJ, Chen SA, Crijns HJ, Damiano RJ Jr, Davies DW, DiMarco J,

et al: 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter

and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: Recommendations for

patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and

follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: A

report of the heart rhythm society (HRS) task force on catheter and

surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Developed in partnership

with the European heart rhythm association (EHRA), a registered

branch of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and the European

cardiac arrhythmia society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the

American college of cardiology (ACC), American heart association

(AHA), the Asia pacific heart rhythm society (APHRS), and the

society of thoracic surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing

bodies of the American college of cardiology foundation, the

American heart association, the European cardiac arrhythmia

society, the European heart rhythm association, the society of

thoracic surgeons, the Asia pacific heart rhythm society, and the

heart rhythm society. Heart Rhythm. 9:632–696.e21. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Jaïs P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, Daoud E,

Khairy P, Subbiah R, Hocini M, Extramiana F, Sacher F, Bordachar P,

et al: Catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial

fibrillation: The A4 study. Circulation. 118:2498–2505.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, De Paola

A, Marchlinski F, Natale A, Macle L, Daoud EG, Calkins H, Hall B,

et al: Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency

catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation:

A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 303:333–340. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, Martin DO, Verma

A, Bhargava M, Saliba W, Bash D, Schweikert R, Brachmann J, Gunther

J, et al: Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as

first-line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: A

randomized trial. JAMA. 293:2634–2640. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hiasa KI, Kaku H, Inoue H, Yamashita T,

Akao M, Atarashi H, Koretsune Y, Okumura K, Shimizu W, Ikeda T, et

al: Age-related differences in the clinical characteristics and

treatment of elderly patients with atrial fibrillation in

Japan-insight from the ANAFIE (All Nippon AF In Elderly) registry.

Circ J. 84:388–396. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shao XH, Yang YM, Zhu J, Zhang H, Liu Y,

Gao X, Yu LT, Liu LS, Zhao L, Yu PF, et al: Comparison of the

clinical features and outcomes in two age-groups of elderly

patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin Interv Aging. 9:1335–1342.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zakeri R, Chamberlain AM, Roger VL and

Redfield MM: Temporal relationship and prognostic significance of

atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients with preserved

ejection fraction: A community-based study. Circulation.

128:1085–1093. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Packer DL, Kowal RC, Wheelan KR, Irwin JM,

Champagne J, Guerra PG, Dubuc M, Reddy V, Nelson L, Holcomb RG, et

al: Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for paroxysmal atrial

fibrillation: First results of the North American arctic front

(STOP AF) pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 61:1713–1723.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Morillo CA, Verma A, Connolly SJ, Kuck KH,

Nair GM, Champagne J, Sterns LD, Beresh H, Healey JS and Natale A:

RAAFT-2 Investigators. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic

drugs as first-line treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

(RAAFT-2): A randomized trial. JAMA. 311:692–700. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Corrado A, Patel D, Riedlbauchova L, Fahmy

TS, Themistoclakis S, Bonso A, Rossillo A, Hao S, Schweikert RA,

Cummings JE, et al: Efficacy, safety, and outcome of atrial

fibrillation ablation in septuagenarians. J Cardiovasc

Electrophysiol. 19:807–811. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zado E, Callans DJ, Riley M, Hutchinson M,

Garcia F, Bala R, Lin D, Cooper J, Verdino R, Russo AM, et al:

Long-term clinical efficacy and risk of catheter ablation for

atrial fibrillation in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.

19:621–626. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Haegeli LM, Duru F, Lockwood EE, Lüscher

TF, Sterns LD, Novak PG and Leather RA: Ablation of atrial

fibrillation after the retirement age: Considerations on safety and

outcome. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 28:193–197. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Baman TS, Jongnarangsin K, Chugh A,

Suwanagool A, Guiot A, Madenci A, Walsh S, Ilg KJ, Gupta SK,

Latchamsetty R, et al: Prevalence and predictors of complications

of radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J

Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 22:626–631. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Deshmukh A, Patel NJ, Pant S, Shah N,

Chothani A, Mehta K, Grover P, Singh V, Vallurupalli S, Savani GT,

et al: In-hospital complications associated with catheter ablation

of atrial fibrillation in the United States between 2000 and 2010:

Analysis of 93 801 procedures. Circulation. 128:2104–2112.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, Davies W,

Iesaka Y, Kalman J, Kim YH, Klein G, Natale A, Packer D, et al:

Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of

catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm

Electrophysiol. 3:32–38. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Thomas D, Katus HA and Voss F:

Asymptomatic pulmonary vein stenosis after cryoballoon catheter

ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Electrocardiol.

44:473–476. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Rottner L, Fink T, Heeger CH, Schlüter M,

Goldmann B, Lemes C, Maurer T, Reißmann B, Rexha E, Riedl J, et al:

Is less more? Impact of different ablation protocols on

periprocedural complications in second-generation cryoballoon based

pulmonary vein isolation. Europace. 20:1459–1467. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tokutake K, Tokuda M, Ogawa T, Matsuo S,

Yoshimura M and Yamane T: Pulmonary vein stenosis after

second-generation cryoballoon ablation for atrial fibrillation.

HeartRhythm Case Rep. 3:36–39. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|