Introduction

Waldenström's macroglobulinemia (WM), also

recognized as lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), represents a rare

mature B-cell proliferative disorder, accounting for <2% of all

non-Hodgkin lymphomas (1,2). WM is composed of small B lymphocytes,

plasma cell-like lymphocytes and plasma cells, which produce a

large amount of monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) in the bone

marrow, leading to increased blood viscosity and potentially

causing various symptoms and complications (3,4). The

diagnosis of WM usually requires a combination of clinical

symptoms, hematological tests and bone marrow biochemical analysis

(5,6). The common symptoms of WM are anemia,

thrombocytopenia, elevated serum IgM levels and increased blood

viscosity. The treatment options for WM include chimeric antigen

receptor-T cell therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy [such as

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, BCL-2 inhibitors],

immunomodulators and monoclonal antibodies (7-9).

The common therapeutic drugs for WM are chemotherapy drugs (such as

bortezomib, cyclophosphamide), immunomodulators (such as rituximab)

and proteasome inhibitors (such as thalidomide) (10). The median age at diagnosis for WM

is ~71 years with the median survival associated with this disease

being >10 years (11,12). Patients diagnosed with WM have a

heightened risk of developing amyloidosis, including the light

chain amyloidosis (AL) type driven by light chain proteins and the

transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) type precipitated by abnormal

transthyretin protein synthesis (13,14).

Notably, 10% of amyloidosis cases associated with WM present as the

AL type, implicating multiple organ systems and leading to

significant morbidity (13). This

comprehensive study explores and reviews the diagnosis and

treatment methods for a patient with cardiac AL amyloidosis

secondary to WM.

Case report

Basic information

A 67-year-old male patient presented to Luohu

People's Hospital of Shenzhen (Shenzhen, China) in August 2021 with

the chief complaints of chest tightness, nocturnal dyspnea and a

paroxysmal cough persisting for half a month. The patient had no

family history of hematologic disorders or amyloidosis. Past

medical history included hypertension (controlled) and no

psychosocial risk factors. Between January 2019 and July 2021, the

patient had sought medical attention at an external hospital

(Shenzhen People's Hospital, Shenzhen, China) due to chest

tightness and nocturnal dyspnea and was diagnosed with ‘chronic

heart failure’. Prior interventions for heart failure in 2019

included diuretics, spironolactone tablets, furosemide tablets and

sacubitril valsartan sodium tablets for 2 years, which provided

transient symptom relief but no improvement in cardiac function.

The patient suffered from the symptoms of chest tightness and

orthopnoea at night, accompanied by paroxysmal cough, as well as

numbness in the toes.

The patient also had symptoms such as difficulty

breathing, edema, fatigue and atrial fibrillation in chronic heart

failure. However, the patient's symptoms of chronic heart failure

were different from those caused by traditional coronary heart

disease and hypertension. The patient presented with the following:

i) Postural hypotension and diastolic dysfunction; ii) special

cardiac signs: a) Thickened ventricular wall but relatively

preserved systolic function (ultrasound showed ‘granular’

myocardial echoes); b) low voltage on electrocardiogram (related to

myocardial amyloid infiltration); iii) multiple systemic

involvement manifestations (systemic deposition of amyloid

protein): Peripheral neuropathy; numbness and pain in hands and

feet; renal dysfunction and elevated creatinine levels; iv) poor

response to traditional heart failure treatment: According to

disease feedback, diuretics have limited efficacy in treating

current patients Beta blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors are also not suitable as they can exacerbate

hypotension. The main pathological manifestation of traditional

chronic heart failure is myocardial systolic and diastolic

dysfunction (13). Cardiac

amyloidosis is an infiltrative cardiomyopathy and mainly

characterized by amyloid deposition leading to myocardial stiffness

and affecting diastolic function (14). Therefore, examinations for cardiac

amyloidosis were necessary.

Laboratory tests

The blood routine examination indicated a white

blood cell count of 5.68x109/l, platelet count of

184x109/l and hemoglobin concentration of 136 g/l, all

within normal ranges. Cardiac enzyme tests revealed cardiac stress

with a creatine kinase level of 48 U/l and an N-terminal pro-brain

natriuretic peptide II level of 8,288 pg/ml. Cardiac infarction

markers indicated myocardial injury with a troponin T level of

0.154 ng/ml and a myoglobin level of 96 ng/ml. The renal function

panel showed a creatinine level of 256 µmol/l, a uric acid level of

521 µmol/l and a β2-microglobulin concentration of 14.7 mg/l,

indicating impaired renal function. The Ig profile showed abnormal

levels with results of IgG 19.5 g/l, IgA 0.60 g/l and IgM 9.98 g/l

(Table I). Serum protein

electrophoresis (Fig. S1;

Data SI; Table SI) revealed albumin (ALB) at

49.2%, β1 globulin (β1G) decreased to 4.5% and β2G at 19.2%.

Immunofixation electrophoresis (Data

SI; Table SII) showed

positive IgM-λ type M protein, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of

59.0 mm/h, negative Bence Jones protein and a free light chain

ratio (κ/λ ratio) of 0.26, with free κ and λ light chains at 132

and 507 mg/l, respectively. The urine analysis showed no protein

and the 24-h urine protein measurement was 93.6 mg, which was

within the normal range. The electrocardiogram showed low voltage

in the limb leads, suggesting cardiac abnormalities (Fig. S2). Genetic mutation detection

(Fig. S3; Data S1; Table SIII) was tested by droplet digital

polymerase chain reaction based on droplet separation and

single-molecule amplification techniques, which identified the

presence of MYD88 innate immune signal transduction adaptor (MYD88)

with positive L265P mutation with a mutation frequency of 2.89%.

Noteworthy abnormalities included cardiac stress, myocardial

injury, impaired renal function, abnormal Ig levels, positive IgM-λ

type M protein, significant proteinuria and low voltage in the limb

leads.

| Table ILaboratory test results of the

patient. |

Table I

Laboratory test results of the

patient.

| Examination

items | Test values | Normal range |

|---|

| Blood cell count,

x109/l | 5.68 | 3.5-9.5 |

| Platelet count,

x109/l | 184 | 125-350 |

| Hemoglobin

concentration, g/l | 136 | 130-175 |

| N-terminal

pro-brain natriuretic peptide II, pg/ml | 8,288 | <125 |

| Troponin T level,

ng/ml | 0.154 | <0.014 |

| Myoglobin level,

ng/ml | 96 | 28-72 |

| Creatinine level,

µmol/l | 256 | 57-111 |

| Uric acid level,

µmol/l | 521 | 208-428 |

| Creatine kinase

level, U/l | 48 | 50-310 |

| β2-microglobulin

concentration, mg/l | 14.7 | 0.8-2.2 |

| Immunoglobulin IgG,

g/l | 19.5 | 8.6-17.4 |

| Immunoglobulin IgA,

g/l | 0.60 | 1.0-4.2 |

| Immunoglobulin IgM,

g/l | 9.98 | 0.3-2.2 |

| Erythrocyte

sedimentation rate, mm/h | 59.0 | <43.5 |

| Serum light chain

ratio (κ/λ) | 0.26 | 0.31-1.56 |

| Serum light chains

κ, mg/l | 132 | 6.7-22.4 |

| Serum light chains

λ, mg/l | 507 | 8.3-27.0 |

| 24-h urine protein,

mg | 93.6 | <150 |

Pathological examination

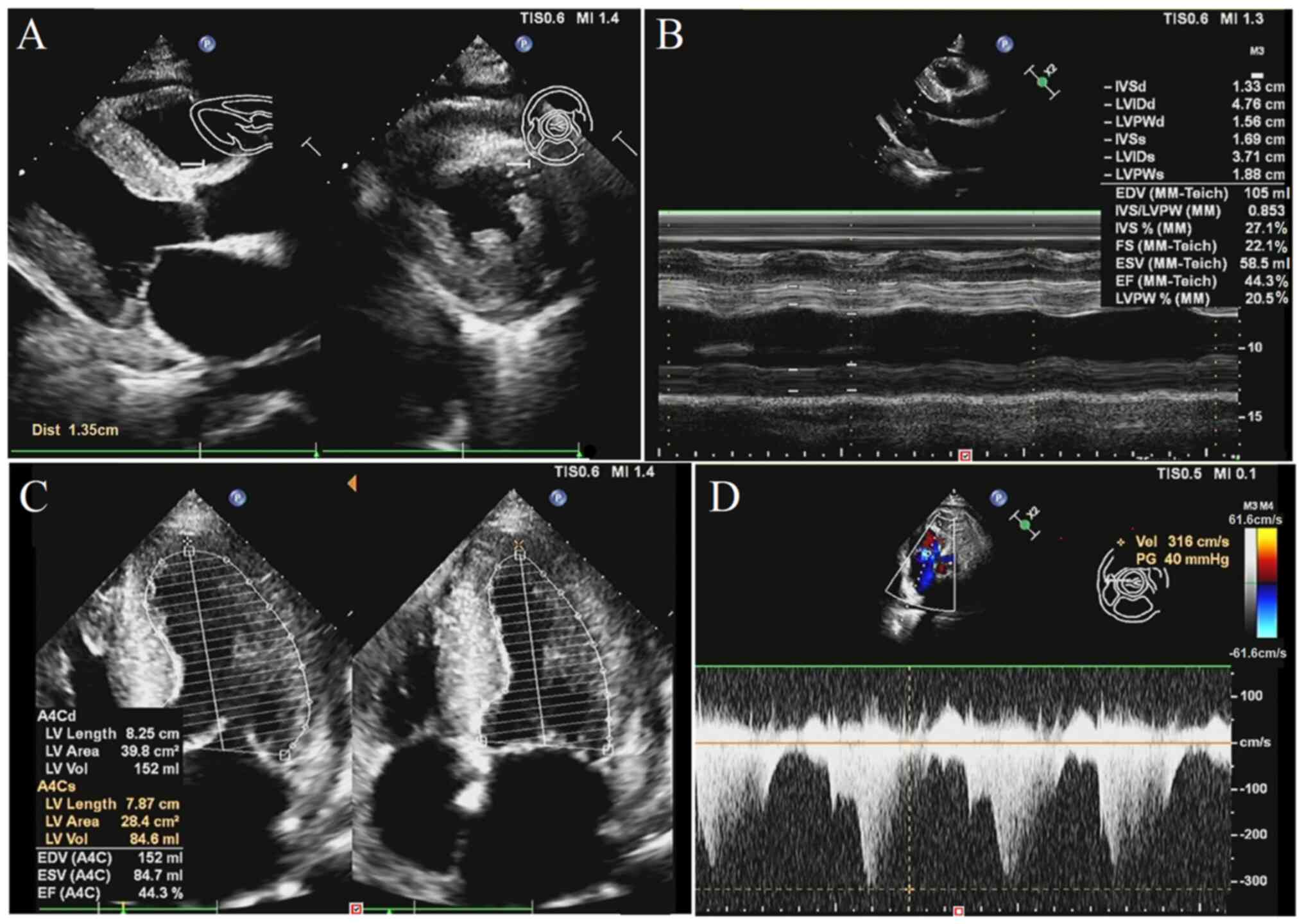

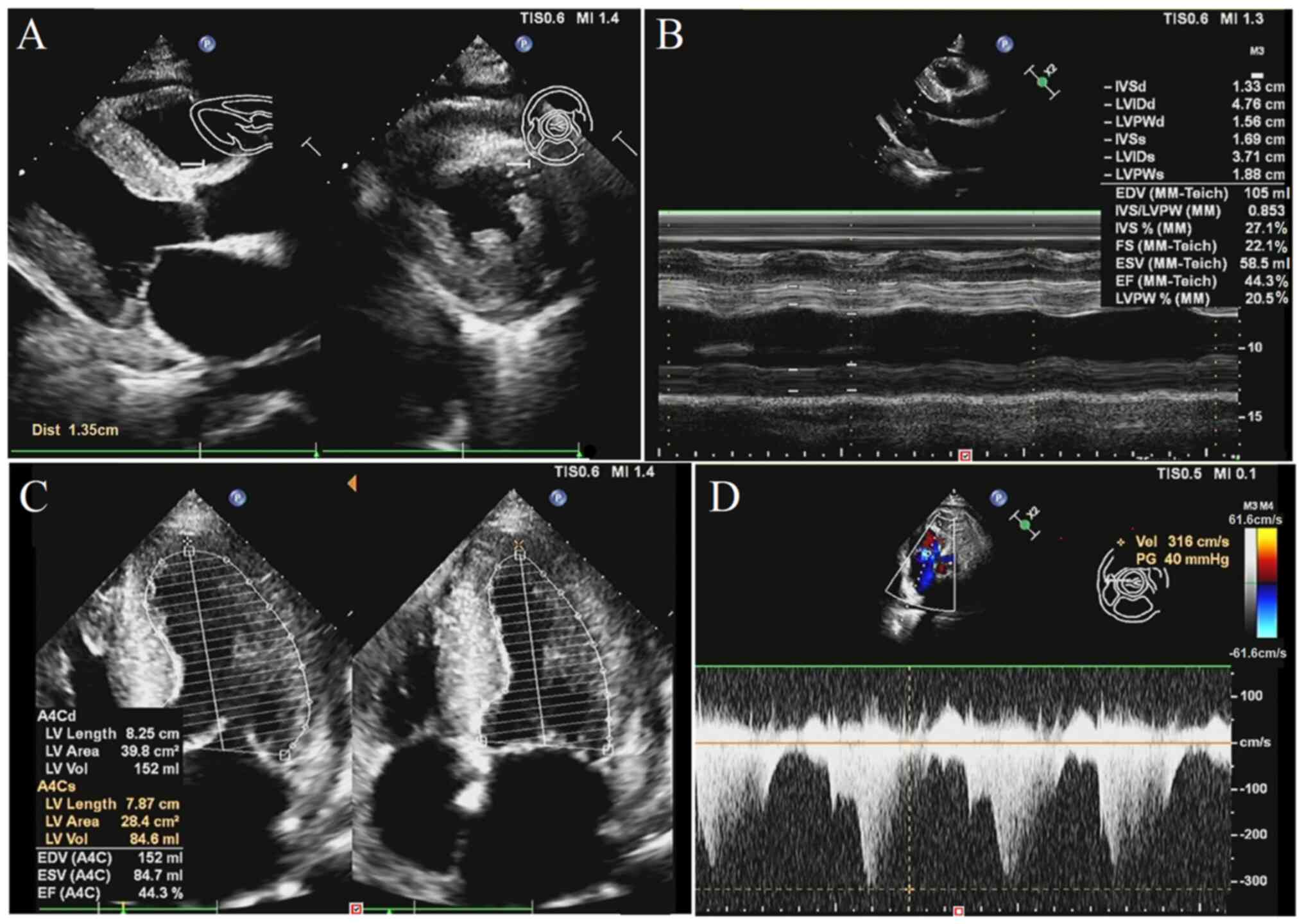

The echocardiography images (Fig. 1A and B) revealed left ventricular posterior

wall hypertrophy with a thickness of 15.6 mm and interventricular

septum of bilateral atrial enlargement with a thickness of 13.3 mm,

which were both higher than normal values (both <12 mm). The

thickened myocardium exhibited scattered sparkling granular echoes

and a small amount of pericardial effusion. The heart valves were

thick and rough and regurgitated. Fig.

1B shows that the left ventricular fractional shortening ratio

was 22%, which is lower than the normal value (25-35%). The

broadened main pulmonary artery diameter resulted in high pulmonary

artery pressure. Fig. 1C shows

that the left ventricular ejection fraction value of cardiac

function was 44.3%, which is lower than the normal value (>50%).

Fig. 1D shows that the left

ventricular wall motion amplitude was slightly lower than normal,

with a peak value of 61.6 cm/sec (normal range, 67-109 cm/sec). The

aforementioned findings suggested that the left ventricular

diastolic and systolic function were reduced, resulting in mild

heart failure.

| Figure 1Echocardiography images. (A) LV (left

ventricular) posterior wall hypertrophy and thickened bilateral

atrial. (B) Various cardiac parameters with ultrasonography

measurements. (C) Low LV ejection fraction value with decreasing

blood-pumping function. (D) Decrease of LV systolic function.

Cardiac echocardiography demonstrating LV hypertrophy (16 mm),

sparkling granular echoes (amyloid deposition) and pericardial

effusion. LV, left ventricle; IVSd, interventricular septum

thickness in diastole; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter in

diastole; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall thickness in

diastole; IVSs, interventricular septum thickness in systole;

LVIDs, left ventricular internal diameter in systole; LVPWs, left

ventricular posterior wall thickness in systole; EDV, end-diastolic

volume; MM-Teich, M-mode Teichholz formula; IVS, interventricular

septum thickness; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall thickness;

FS, fractional shortening; ESV, end-systolic volume; EF, ejection

fraction; LV, left ventricular; A4C, apical four-chamber view;

A4Cd/A4Cs, apical four-chamber view in diastole/systole; Vol,

volume; TIS, thermal index for soft tissue; MI, mechanical index;

Dist, distance. |

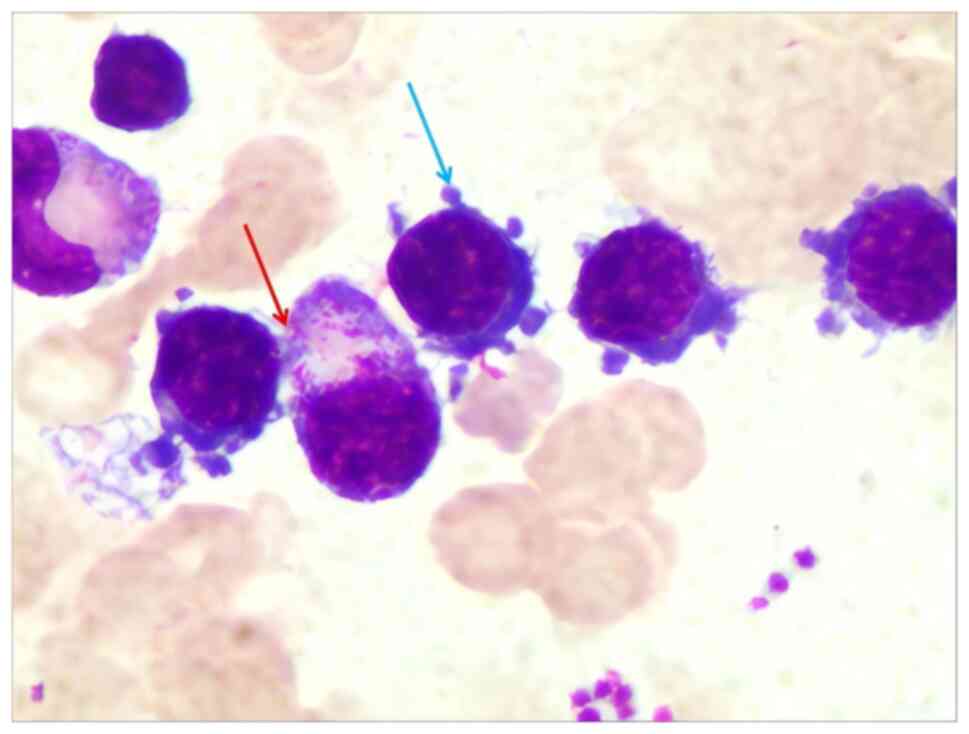

The bone marrow morphology (Data SI; Table SIV) revealed active proliferation

with an increased proportion of lymphocytes, as shown in Fig. 2. Certain lymphocytes exhibited

plasma-like differentiation, while lymphocytes and plasma-like

lymphocytes exhibited focal aggregation. The lymphocytes were

predominantly mature, with ~10% identified as abnormal lymphocytes.

The abnormal lymphocytes had a small size, dense nuclear chromatin

and a small cell mass, and part of the cell cytoplasm exhibited

blue, foam-like, plasma cell-like changes or irregular cytoplasm

edges with burrs. The proportion and morphology of erythrocytes

were normal. Platelets were distributed in single or small clusters

and were easily visible with a small number of abnormal platelets.

The proportion of plasma cells was about 4%, which were mature

plasma cells.

The flow cytometry of bone marrow (Data SI; Table SV) results showed that lymphocytes

constituted 13.72% of nucleated cells (normal range, 10-20%), with

T lymphocytes comprising 49.69% (normal range, 60-80%). The

CD4+/CD8+ ratio was 0.37 (normal range, 1.4-2.0), reflecting a

decreased ratio, yet no discernible phenotypic abnormalities were

apparent. Among the lymphocytes, the proportion of CD19+ B cells

was 32.78% (normal range, 5-15%; Fig.

S4), exhibiting a phenotype characterized by CD19+, CD20+,

Lambda++, Kappa-, CD5-, CD10-, CD3-, GD4-, CD8-, CD2- and CD7-.

Granulocytes accounted for 68.96% (normal range, 50-60%), with a

proportion within the normal range, and no notable abnormalities

were observed in the proportion and phenotype of granulocytes at

various stages. The CD34+ and CD117+ marrow cells had a low

proportion of 0.47% (normal value, <1%), and no apparent

phenotypic abnormalities were observed. Notably, abnormal mature B

cells, displaying immunophenotypic abnormalities, made up ~4.94%

(normal value, 0%) of nucleated cells. B-cell lymphoma excluding

CD5- and CD10-could not be conclusively ruled out, necessitating

further investigation to establish a definitive diagnosis.

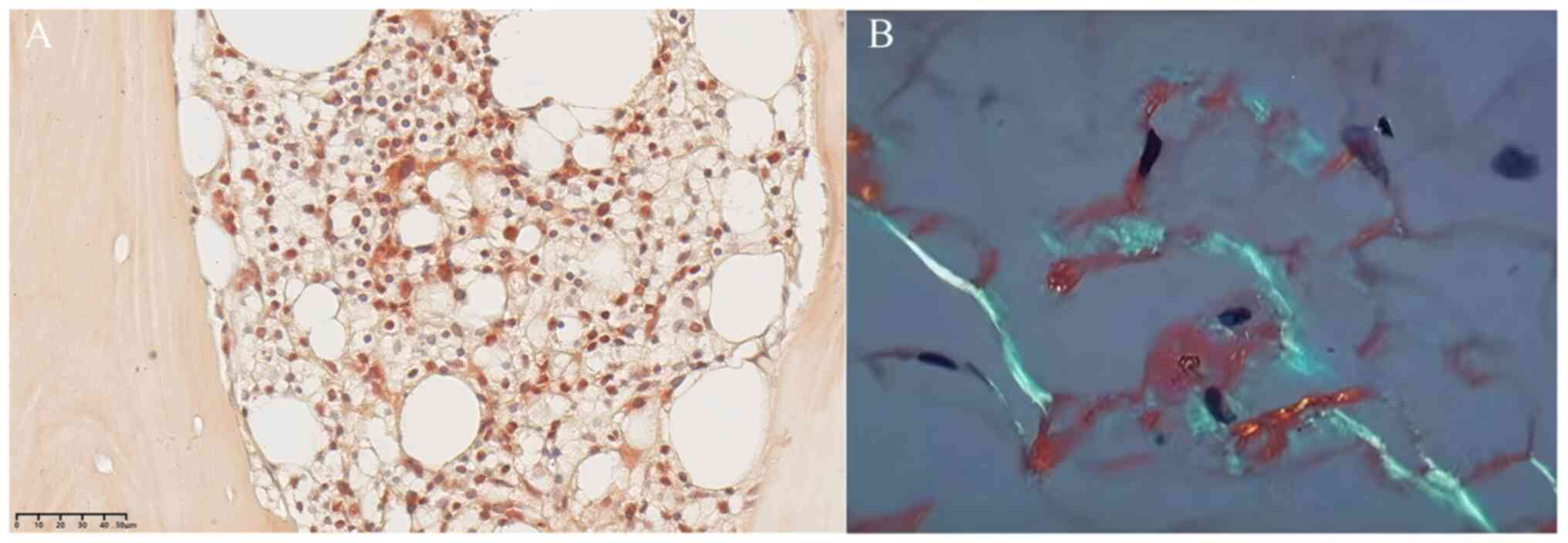

Fig. 3A shows the

bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemistry and Congo red staining

(Data S1), which was completed

through biopsy of the posterior superior iliac spine. The results

indicate that the proportion of red bone marrow decreased, the

proportion of granulocytes, red cells and megakaryocytes in the red

pulp was normal, and the morphology of each cell was relatively

mature, with a few scattered plasma cells. In typical amyloidosis

cases, amyloid substance is an amorphous extracellular eosinophilic

substance, which is commonly identified by the normal Congo red

staining method because with other staining, it is difficult to

distinguish colors. The Congo red staining was positive, displaying

in orange red, which indicated the existence of amyloid substance.

Amyloid protein mass spectrometry was performed on abdominal fat

biopsy (Congo red-positive) with 84% sensitivity (15), which is a recommendation surrogate

biopsy tissue for most patients, and confirming AL type with

predominant Ig λ C2 spectra (12%). Cardiac tissue biopsy was not

feasible due to the patient's unstable condition. Fig. 3B shows the biopsy of abdominal wall

fat tissue with Congo red staining; an apple green color

originating from amyloid substance with double refraction was

visible under a polarized light microscope, which was transformed

through the amyloid substance. Therefore, the Congo red staining

with orange red and apple green color transformation both confirmed

cardiac amyloidosis in this case.

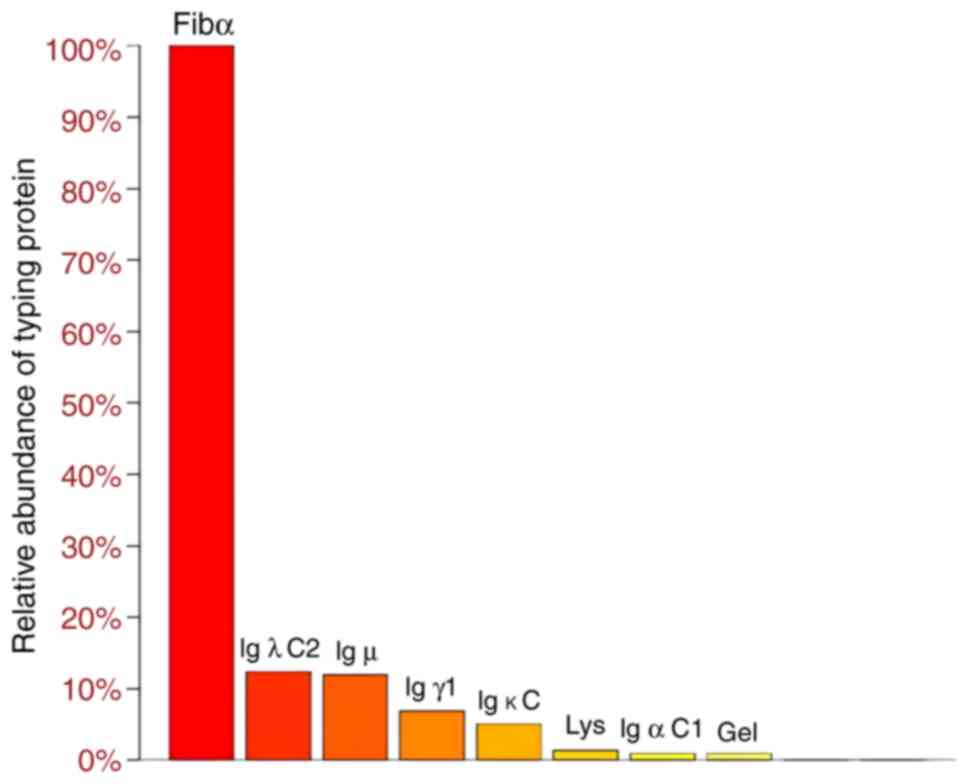

The amyloid protein mass spectrometry spectrum of

abdominal adipose tissue was used to determine the amyloidosis type

(Data S1), as shown in Fig. 4. Fibrinogen α chain (Fibα), the Ig

light chain constant (Igλ C2), the Ig heavy chains Igµ, Igγ1 and

Igα C1, Ig light chain κ C, lysozyme (lys) and gelsolin (gel) were

detected. Among the currently known sub-typing proteins in Fig. 4, Fibα has the highest relative

abundance in spectra, but Fibα<β+γ indicates that Fibα comes

from blood contamination (α 218, β 294, γ 188) and is not a

sedimentary protein (16).

Compared with heavy chains, light chains (especially λ type) are

more likely to form amyloid fibrils due to their genetic sequence

and high secretion characteristics (13). Thus, light chains are more prone to

deposit in the cardiac position, leading to cardiac amyloidosis.

Excluding Fibα, among other typing proteins, Igλ C2 had the highest

relative abundance in the spectrum, κ and λ values are

significantly higher than the normal range (Table I), indicating that the main type is

AL amyloidosis. Therefore, based on the positive Congo red staining

and abdominal adipose tissue mass spectrometry analysis, the

diagnosis was cardiac amyloidosis of the AL type.

Diagnosis and treatment process

Based on the comprehensive characteristics of the

case and auxiliary examination results, the diagnosis aligns with

the criteria for LPL/WM, IgM-λ type, high-risk, accompanied by

cardiac AL amyloidosis. The patient's prior diagnosis of chronic

heart failure made in 2019 was attributed to non-specific causes,

and no amyloidosis or hematologic malignancy was suspected until

2021, which highlights the importance of considering amyloidosis in

refractory heart failure. The diagnosis of WM was confirmed through

abnormal IgM (9.98 g/l) levels, λ-free light chains (507 mg/l), the

existence of small B lymphocytes, plasma cell-like lymphocytes,

plasma cells, M protein and MYD88 with L265P mutation. The cardiac

amyloidosis was identified through cardiac biomarkers (N-terminal

pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: 8,288 pg/ml), cardiac

echocardiography (sparkling echoes), positive Congo red staining of

bone marrow and apple green color transformation of abdominal fat

biopsy, and mass spectrometry peaks of Ig λ C2 and µ heavy chain as

the dominant amyloid protein with AL type.

In August 2021, the patient initiated the BR

regimen, which consisted of Bendamustine (0.15 g intravenously on

days 2-3) and Rituximab (0.6 g intravenously on day 1), following a

28-day chemotherapy cycle. A second course of the BR regimen was

administered in September 2021, maintaining the same regimen and

dosage as the initial course. The disease was subsequently

evaluated as stable disease. In October 2021, the patient underwent

a third-line treatment with the BRD regimen. This regimen included

subcutaneous injections of 2 mg bortezomib on days 1, 8, 15 and 22,

intravenous infusion of 0.5 g rituximab on the same days, and

intravenous infusion of 10 mg dexamethasone on days 1, 8, 15 and

22, with treatments administered once a week within a 28-day

chemotherapy cycle. After the treatment, the patient was determined

to show a partial response (PR). The patient adhered to treatment

with no adverse events and at the six-month follow-up, the patient

showed sustained hematological PR but progressive diastolic

dysfunction on echocardiography. The patient voluntarily left the

hospital due to economic difficulties. The PR was mainly based on

hematological criteria: >50% reduction in serum IgM (from 9.98

to 4.79 g/l), >50% reduction in the difference of serum free

light chain (dFLC) and a decrease of cardiac injury markers

(troponin T: 0.119 ng/ml). Cardiac function (ejection faction: 50%)

remained stable but did not improve due to irreversible amyloid

deposition. The follow-up was terminated as the patient did not

return to the hospital for treatment after discharge.

Discussion

Cardiac AL amyloidosis secondary to WM presents

diverse clinical manifestations and treatment complexities.

According to the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology, the

‘Diagnosis and Treatment of LPL/WM Chinese Expert Consensus (2022

version)’ outlines the diagnostic criteria for WM (17). The diagnostic markers of WM are

small B lymphocytes, plasma cell-like lymphocytes and plasma cells,

as well as high concentrations of IgM. The diagnostic markers of

amyloidosis are positive Congo red staining of the fat tissue

biopsy and apple green color transformation. The diagnosis requires

exclusion of other lymphomas and the presence of the MYD88 with

L265P mutation, found in >90% of WM cases (18). Herein, the genetic mutation

detection of this case identified the presence of MYD88 with

positive L265P mutation type.

At present, the specific mechanisms of WM are not

fully understood, but studies have confirmed that genetic

alterations may occur. García-Sanz et al (19) studied the clonality of tumor

populations in WM and how clonal complexity can evolve and impact

disease progression. Single-cell transcriptomics analysis also

indicated that MYD88 could be an early event in tumorigenesis

(20). In addition, X-box binding

protein 1 (XBP1)-endoplasmic reticulum to nucleus signaling 1α

(ERN1α) may play a role in the pathogenesis of WM because about 80%

of patients have high XBP1 splicing mRNA expression, with 80%

showing high mRNA ERN1α expression (21). The WM tumor progression is closely

related to the bone marrow microenvironment and cytokines (22).

A study that included 20 years of data (1988 to

2007) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)

program showed that the median age at diagnosis for WM was 73

years, with an overall age-adjusted incidence rate of 0.38/100,000

per year, increasing to 2.85 among patients older than 80 years

(23). Risk factors for WM

prognosis include age (>65 years), elevated β-2 microglobulin,

organomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia, low ALB, high serum

monoclonal protein and high serum free light chain concentration.

Recent research indicates that the median age at diagnosis for WM

is ~71 years (12). Previous

studies indicated that the median survival of patients with WM

under the age of 70 is in excess of 10 years, that of patients aged

70-79 years is ~7 years and the median survival of patients aged 80

years or above is nearly 4 years (8,12).

The incidence rate of WM is ~24,000 individuals every year

globally, and the male-to-female ratio is 3.2:1. One study based on

5,784 patients with WM in the SEER database indicated that the

median overall survival (OS) improved from 6 to 8 years from 1991

to 2010(24). Another study

determined that the median survival after treatment initiation was

87 months among 587 patients with WM (25).

The median diagnostic age of cardiac amyloidosis was

determined to be >60 years (26). The median survival of cardiac ATTR

and AL amyloidosis was determined to be 2-5 years and the OS at 2

years was 63% for AL and 98% for ATTR from diagnosis, indicating

that the prognosis of cardiac ATTR amyloidosis is better than that

of cardiac AL amyloidosis (27).

The median survival of patients with AL amyloidosis associated with

WM was reported to be in the range of 49-78 months, which was not

significantly different compared with patients without IgM, as

survival is independently affected by cardiac involvement (28-30).

WM may lead to various complications, including

cardiac amyloidosis, and the heart is easily affected by

amyloidosis secondary to WM. Among patients with WM in SEER

database, most subjects were found to present with symptoms related

to tumor burden, while only ~10% of patients concurrently suffer

from AL amyloidosis (12,13). Cardiac amyloidosis is an uncommon

cardiopathy and characterized by the deposition of insoluble

amyloid proteins within cardiac tissues. The mechanism of

amyloidosis secondary to WM is that abnormal production and

deposition of monoclonal IgM may cause cardiac amyloidosis,

affecting cardiac structure and function and resulting in heart

failure (13). The definition, the

diagnostic criteria, criteria for initiation of therapy and a new

classification scheme of amyloidosis and WM were established in

2004(31). A study of 50 patients

with serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy showed that 53% of the

patients died of cardiac amyloidosis, while 32, 14 and 10% of

patients also had renal, liver and lung amyloidosis, respectively

(32). IgM-related amyloidosis

accounts for only 6-10% in patients with various Ig-related

amyloidoses, and 54% of cases among them were associated with

underlying non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, including WM (33,34).

A test of the MYD88 mutation status is necessary for the evaluation

of IgM-related AL, as these mutations are distinct features of WM

(35). Gustine et al

(36) studied consecutive patients

from 2006 to 2022; all patients were diagnosed with WM-AL

amyloidosis through the criteria of the presence of IgM

paraprotein, bone marrow infiltration by lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

and positive Congo red staining of a biopsy specimen. The median OS

was 7.3 years in 49 patients with WM-AL amyloidosis. Patients with

WM with cardiac amyloidosis may be misdiagnosed as either AL or

ATTR amyloidosis by immunohistochemistry and can be correctly

identified by mass spectrometry (37). The reported patients with WM-ATTR

amyloidosis had a lower dFLC than patients with AL. In the case of

the present study, a delay in diagnosis occurred due to overlapping

symptoms with heart failure and the rarity of WM-associated AL

amyloidosis.

WM secondary to cardiac amyloidosis is controlled

and treated through chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted

therapy, and a high level of autologous stem cell transplantation.

The management of cardiac symptoms requires specific interventions

for heart failure, arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities.

First-line treatment options for symptomatic patients with WM

include Rituximab-chemotherapy and BTK inhibitors, such as

ibrutinib, either alone or combined with rituximab and zanubrutinib

(13,36). For patients with WM-AL amyloidosis,

the most common salvage therapy method is a bortezomib- and/or

bendamustine-based regimen (36).

BR is preferred for rapid tumor reduction or high tumor burden,

showing potential for longer progression-free survival. The choice

of BTK inhibitors should consider the MYD88 L265P mutation, as the

wild-type shows the best response and the mutated type has a poor

response and may benefit from added rituximab (38). The patient of the present study

carried the MYD88 L265P mutation, which was treated with the BR and

BRD regimen rather than BTK inhibitors. Compared with Bendamustine,

proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib are not first-line

medications but may be used in resistant cases to target and kill

tumor cells. The Bendamustine is more expensive than bortezomib,

and thus, the patient preferred the BRD regimen; however, both the

BR and BRD regimens failed to achieve the expected effect with only

a PR. AL amyloidosis is one of the most dangerous disorders related

to the M protein, which is better treated before irreversible organ

impairment has occurred (28,39).

In the present study, the patient with WM-AL amyloidosis failed to

respond to the BR and BRD regimens, presumably because he was

diagnosed with chronic heart failure at an external hospital in

2019, but was diagnosed as WM accompanied by cardiac AL amyloidosis

in 2021. The irreversible organ impairment caused by WM-AL

amyloidosis may have occurred before therapy at our hospital.

Numerous specific cases of WM accompanied by cardiac

amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. A 70-year-old

male was diagnosed as WM with AL amyloidosis, was then started on

bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone and rituximab, and

after three cycles of therapy, IgM had decreased to 1,500 mg/dl

with improved performance status (13). A 52-year-old male was diagnosed

with WM accompanied by AL amyloidosis and the rituximab and

bortezomib-based chemotherapy was ineffective (40). A 76-year-old African American male

with chronic kidney disease was diagnosed with WM accompanied by

ATTR amyloidosis, and after 12 months of tafamidis-based

chemotherapy, cardiac and hematological conditions were stable

(41). An 80-year-old female

hospitalized for chronic dyspnea and cough was diagnosed with λ

light chain and µ heavy chain type amyloidosis; the patient was not

suited for chemotherapy or immunotherapy due to severe heart

failure and hypotension (42). The

previous study demonstrated that WM-AL amyloidosis can also be

treated with the standard WM regimens, such as bortezomib,

dexamethasone and rituximab or bendamustine and rituximab (36). High-dose melphalan and stem cell

transplantation (HDM/SCT) should be a new option for patients with

WM-AL amyloidosis, as HDM/SCT-based therapy can prolong survival to

>20 years in typical AL amyloidosis (43).

In conclusion, a case was diagnosed with WM

accompanied by cardiac AL amyloidosis based on the presence of

abnormal IgM paraprotein levels and the high Ig λ C2 spectrum in

the amyloid protein mass spectrometry. The novelty of this case

lies in the rare cardiac AL amyloidosis secondary to WM,

particularly the diagnostic challenges and the limited treatment

response due to irreversible cardiac damage. The BR and BRD-based

therapy only yielded a PR and the symptom of chronic heart failure

due to irreversible organ impairment had occurred before treatment

at our hospital. This result indicates that WM secondary to cardiac

amyloidosis needs to be diagnosed and treated as early as possible

by inspecting IgM levels, amyloid protein mass spectrometry,

genetic mutation analysis and pathological examination of tissues

before the irreversible organ impairment at the site of the heart.

In addition, the mechanisms, treatment methods and survival of WM,

ATTR or AL amyloidosis and WM-AL amyloidosis were reviewed in this

paper. The complexities of WM and its secondary complications such

as cardiac amyloidosis highlight the need for ongoing research and

collaboration. Integrating advanced diagnostic techniques and

personalized treatment strategies will improve the management of

this disease and increase patient quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods

Test result of serum protein

electrophoresis. The peak on the left represents ALB protein and

the peak on the right represents γ globulin. The appearance of

steep ‘peaks’ in the right elecrophoretic bands indicates the

presence of abnormally increased immunoglobulin. Ref. Conc.,

reference concentration΄ ALB, albumin.

Low voltage in the limb leads in the

electrocardiogram.

Gene mutation detection by droplet

digital polymerase chain reaction. The blue dots represent the

MYD88 mutant type. The green dots represent MYD88 wild-type (no

mutation). Orange dots represent a mixed state of mutant and

wild-type (such as chimeric mutations or low abundance mutations).

The black dots represent the background noise.

Flow cytometry results. The antibody

labeling method is the five color method. The antibodies include

CD19-PC5.5 for recognizing B cells, and CD20-APC for recognizing

mature B cells. The gated area includes CD19+ and CD20+ cells (pink

area), representing a subset of B cells that simultaneously express

CD19 and CD20. The green area on the left represents CD19 low

expression or negative cells. The 4.94% is the proportion of CD19+

and CD20+ in the total lymphocytes based on upstream lymphocyte

gating. The 32.78% represents the proportion of CD19+ and CD20+ in

CD19+ cells in this case.

Test results of serum protein

electrophoresis.

Test results of immunofixation

electrophoresis.

Test results of genetic mutation

detection.

Test results of bone marrow histology

morphology.

Test results of bone marrow histology

morphology.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Miss Shuaiyang Wang

(technologist-in-charge) and Miss Hongmei Mo (associate senior

technologist) of the Clinical Laboratory of Luohu People's Hospital

of Shenzhen (Shenzhen, China), and Miss Huizhi Guo (attending

physician) of the Department of Ultrasound of Luohu People's

Hospital of Shenzhen for providing the examination reports of the

current patient.

Funding

Funding: This research was funded by Sanming Project of Medicine

in Shenzhen (grant no. SZSM202301035).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FD was responsible for the case diagnosis and

treatment, as well as writing and analysis of the manuscript. AG

contributed to the data analysis and collection. LZ analyzed

patient data, DL provided treatment advice, JC collected image

data, HX collected pathological data, WL collected ultrasound data,

JL collected flow cytometry of bone marrow data and YL collected

the amyloid protein mass spectrometry spectrum data. HC was

responsible for study conception and revisions to the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. FD and HC

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study received approval from the Shenzhen Luohu

People's Hospital Research Ethics Committee (grant no.

2024-LHQRMYY-KYLL-26). The protocol and informed consent form were

reviewed and approved on May 12, 2024, with a subsequent simplified

review conducted on May 23, 2024. The study adheres to ethical

standards as outlined by the committee. The patient provided

written informed consent for participation.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

publication of their data, including case information and

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris

NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz

AD and Jaffe ES: The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization

classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 127:2375–2390.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Olszewski AJ, Treon SP and Castillo JJ:

Evolution of management and outcomes in Waldenström

macroglobulinemia: A population-based analysis. Oncologist.

21:1377–1386. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Vijay A and Gertz MA: Waldenström

macroglobulinemia. Blood. 109:5096–5103. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zheng L, Zeng Z, Lin J and Chen J: IgM

multiple myeloma presenting with bleeding tendency: A case report

with immunophenotype analysis. Oncol Lett. 2:55–57. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wang Q, Liu Q, Liang H and Gao W: Biclonal

lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia associated

with POEMS syndrome: A case report and literature review. Oncol

Lett. 25(97)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Dimopoulos MA, Kyle RA, Anagnostopoulos A

and Treon SP: Diagnosis and management of Waldenstrom's

macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol. 23:1564–1577. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Dimopoulos MA, Merlini G, Leblond V,

Anagnostopoulos A and Alexanian R: How we treat Waldenstrom's

macroglobulinemia. Haematologica. 90:117–125. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Oza A and Rajkumar SV: Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia: Prognosis and management. Blood Cancer J.

5(e391)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Grunenberg A and Buske C: How to manage

waldenström's macroglobulinemia in 2024. Cancer Treat Rev.

125(102715)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Castillo JJ and Treon SP: What is new in

the treatment of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia? Leukemia.

33:2555–2562. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hodge LS and Ansell SM: Waldenström's

macroglobulinemia: Treatment approaches for newly diagnosed and

relapsed disease. Transfus Apher Sci. 49:19–23. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gertz MA: Waldenström macroglobulinemia:

2023 Update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J

Hematol. 98:348–358. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lu R and Richards T: A focus on

Waldenström macroglobulinemia and AL amyloidosis. J Adv Pract

Oncol. 13 (Suppl 4):S45–S56. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Merlini G, Sarosiek S, Benevolo G, Cao X,

Dimopoulos M, Garcia-Sanz R, Gatt ME, Fernandez de Larrea C,

San-Miguel J, Treon SP and Minnema MC: Report of consensus panel 6

from the 11 th international workshop on Waldenström's

macroglobulinemia on management of Waldenström's macroglobulinemia

related amyloidosis. Semin Hematol. 60:113–117. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Rubin J and Maurer MS: Cardiac

amyloidosis: Overlooked, underappreciated, and treatable. Annu Rev

Med. 71:203–219. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sethi S, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Leung N,

Sethi A, Nasr SH, Fervenza FC, Cornell LD, Fidler ME and Dogan A:

Laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomics aids

the diagnosis and typing of renal amyloidosis. Kidney Int.

82:226–234. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yi S and Li J: Chinese expert consensus on

diagnosis and treatment of lymphatic plasma cell

lymphoma/fahrenheit megaglobulinemia (2022 edition). Chin J

Hematol. 43:624–630. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

18

|

Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, Zhou Y, Liu X, Cao

Y, Sheehy P, Manning RJ, Patterson CJ, Tripsas C, et al: MYD88

L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J

Med. 367:826–833. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

García-Sanz R, García-Álvarez M, Medina A,

Askari E, González-Calle V, Casanova M, de la Torre-Loizaga I,

Escalante-Barrigón F, Bastos-Boente M, Bárez A, et al: Clonal

architecture and evolutionary history of Waldenström's

macroglobulinemia at the single-cell level. Dis Model Mech.

16(dmm050227)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Qiu Y, Wang XS, Yao Y, Si YM, Wang XZ, Jia

MN, Zhou DB, Yu J, Cao XX and Li J: Single-cell transcriptome

analysis reveals stem cell-like subsets in the progression of

Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. Exp Hematol Oncol.

12(18)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Leleu X, Hunter ZR, Xu L, Roccaro AM,

Moreau AS, Santos DD, Hatjiharissi E, Bakthavachalam V, Adamia S,

Ho AW, et al: Expression of regulatory genes for lymphoplasmacytic

cell differentiation in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Br J

Haematol. 145:59–63. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Boutilier AJ, Huang L and Elsawa SF:

Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mechanisms of disease progression

and current therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 23(11145)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wang H, Chen Y, Li F, Delasalle K, Wang J,

Alexanian R, Kwak L, Rustveld L, Du XL and Wang M: Temporal and

geographic variations of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia incidence: A

large population-based study. Cancer. 118:3793–3800.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Castillo JJ, Olszewski AJ, Kanan S, Meid

K, Hunter ZR and Treon SP: Overall survival and competing risks of

death in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinaemia: An analysis

of the surveillance, epidemiology and end results database. Br J

Haematol. 169:81–89. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Morel P, Duhamel A, Gobbi P, Dimopoulos

MA, Dhodapkar MV, McCoy J, Crowley J, Ocio EM, Garcia-Sanz R, Treon

SP, et al: International prognostic scoring system for Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia. Blood. 113:4163–4170. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Aimo A, Merlo M, Porcari A, Georgiopoulos

G, Pagura L, Vergaro G, Sinagra G, Emdin M and Rapezz C: Redefining

the epidemiology of cardiac amyloidosis. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of screening studies. Eur J Heart Fail. 24:2342–2351.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Rapezzi C, Merlini G, Quarta CC, Riva L,

Longhi S, Leone O, Salvi F, Ciliberti P, Pastorelli F, Biagini E,

et al: Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: Disease profiles and clinical

courses of the 3 main types. Circulation. 120:1203–1212.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Palladini G and Merlini G: Diagnostic

challenges of amyloidosis in Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 13:244–246. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wechalekar AD, Lachmann HJ, Goodman HJ,

Bradwell A, Hawkins PN and Gillmore JD: AL amyloidosis associated

with IgM paraproteinemia: Clinical profile and treatment outcome.

Blood. 112:4009–4016. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Palladini G, Russo P, Bosoni T, Sarais G,

Lavatelli F, Foli A, Bragotti LZ, Perfetti V, Obici L, Bergesio F,

et al: AL amyloidosis associated with IgM monoclonal protein: A

distinct clinical entity. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 9:80–83.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Gertz MA, Merlini G and Treon SP:

Amyloidosis and Waldenström's Macroglobulinemia. Hematology Am Soc

Hematol Educ Program. 2004:257–282. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Gertz MA, Kyle RA and Noel P: Primary

systemic amyloidosis: A rare complication of immunoglobulin M

monoclonal gammopathies and Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. J Clin

Oncol. 11:914–920. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Bou Zerdan M, Valent J, Diacovo MJ, Theil

K and Chaulagain CP: Utility of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors

in light chain amyloidosis caused by lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

(Waldenström's macroglobulinemia). Adv Adv Hematol.

2022(1182384)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zanwar S, Abeykoon JP, Ansell SM, Gertz

MA, Dispenzieri A, Muchtar E, Sidana S, Tandon N, Rajkumar SV,

Dingli D, et al: Primary systemic amyloidosis in patients with

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Leukemia. 33:790–794.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sidana S, Larson DP, Greipp PT, He R,

McPhail ED, Dispenzieri A, Murray DL, Dasari S, Ansell SM, Muchtar

E, et al: IgM AL amyloidosis: Delineating disease biology and

outcomes with clinical, genomic and bone marrow morphological

features. Leukemia. 34:1373–1382. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gustine JN, Szalat RE, Staron A, Joshi T,

Mendelson L, Sloan JM and Sanchorawala V: Light chain amyloidosis

associated with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: Treatment and

survival outcomes. Haematologica. 108:1680–1684. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Singh A, Geller HI, Alexander KM, Padera

RF, Mitchell RN, Dorbala S, Castillo JJ and Falk RH: True, true

unrelated? Coexistence of Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cardiac

transthyretin amyloidosis. Haematologica. 103:e374–e376.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN). Waldenström macroglobulinemia/lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

Version 1.2022, 2024.

|

|

39

|

Merlini G and Palladini G: Amyloidosis: Is

a cure possible? Ann Oncol. 19 (Suppl 4):iv63–iv66. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Charles Lobo A, Bhat V, Anandram S, Devi A

M S, Rao SS, Vinister GV, Lobo V and Reuben Ross C: Rare

complication of a rare malignancy: Case report of cardiac

amyloidosis secondary to waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Qatar Med

J. 2022(7)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Qian X, Bakhshi H, Biswas R, Gattani R and

Kennedy JL: Concurrent waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and mutant

transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. J Community Hosp Intern Med

Perspect. 12:95–99. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ho VV, O'Sullivan JW, Collins WJ, Ozdalga

E, Bell CF, Shah ND, Krishnam MS, Ozawa MG and Witteles RM:

Constrictive pericarditis revealing rare case of ALH amyloidosis

with underlying lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia). JACC Case Rep. 4:271–275. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Gustine JN, Staron A, Szalat RE, Mendelson

LM, Joshi T, Ruberg FL, Siddiqi O, Gopal DM, Edwards CV, Havasi A,

et al: Predictors of hematologic response and survival with stem

cell transplantation in AL amyloidosis: A 25-year longitudinal

study. Am J Hematol. 97:1189–1199. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|