Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a leading cause of mortality

worldwide, the third most common cancer and the second leading

cause of cancer-associated mortality, with increasing rates of

morbidity and mortality in recent years (1,2). In

2025 cancer statistics, colorectal cancer accounted for almost

one-half (48%) of all cancer cases in men. For women, colorectal

cancer accounts for 51% of all new diagnoses (3). Postoperative intestinal complications

are critical determinants of patient prognosis. Among these

complications, anastomotic leakage (AL) is considered the most

severe due to its association with increased morbidity and

mortality rates, adverse effects on both functional and oncological

outcomes, and substantial strain on healthcare resources (4).

Systemic opioid analgesics have long been used to

manage severe trauma-related pain; however, their use is associated

with significant risks, including respiratory depression, opioid

use disorder and potentially fatal overdose (5,6). The

higher the dose and the longer the duration of opioid use, the

greater the risk of developing both physical and psychological

dependence. In recent years, multimodal analgesia has been

increasingly advocated for various types of surgery, including

gastrointestinal procedures (7).

To minimize opioid consumption and its associated adverse effects,

multimodal analgesia incorporates alternative analgesic strategies,

such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), regional

nerve blocks and other adjuncts.

NSAIDs are recommended for the management of

perioperative pain in a variety of surgical procedures, including

colorectal surgery, to reduce the perioperative use of opioid use

and accelerate postoperative recovery (8,9).

However, the use of high doses of NSAIDs has been linked to an

elevated risk of developing intestinal complications, rendering

their use in colorectal cancer surgery a subject of ongoing debate

(10,11). Notably, a large study reported that

diclofenac treatment could increase the incidence of AL following

colorectal surgery (12).

Flurbiprofen axetil, a non-selective cyclooxygenase

(COX) inhibitor, is commonly used in clinical practice as an

antipyretic and analgesic (13).

When combined with oxycodone in patient-controlled intravenous

analgesia, flurbiprofen axetil effectively reduces pain intensity,

particularly visceral pain, and may help counteract the

immunosuppressive state during the radical resection of colorectal

cancer (14). However, despite its

widespread use, the association between flurbiprofen axetil and

intestinal complications remains poorly understood. The present

study thus aimed to investigate the association between the

perioperative use of flurbiprofen axetil and the incidence of

intestinal complications following colorectal surgery through a

retrospective analysis.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

This single-center retrospective study was conducted

at Peking University People's Hospital (Beijing, China) on data

retrieved from patients who underwent their first radical

colorectal surgery between January 1, 2018, and March 31, 2022. The

study was performed in accordance with the principles of the

Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval was obtained from the

Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University People's Hospital

(approval no. 2022PHB131-001).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥18 years who underwent elective

radical colorectal resection were included in the present study.

Inclusion criteria required an American Society of

Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade (15) of I to III and the performance of

radical colorectal surgery. Exclusion criteria included patients

who underwent a second surgery or more during the same hospital

admission, those admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) prior to

surgery, those with missing or incomplete prognostic records and

those who received intraspinal analgesia due to concerns about

interference with the administration of flurbiprofen axetil. In

addition, patients with severe liver, kidney and coagulation

dysfunction, for which the use of flurbiprofen axetil is

prohibited, were excluded from the study.

Patient characteristics

Comprehensive patient data were collected, including

age, sex, body mass index, ASA classification and medical history

(for example, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and

pulmonary, hepatic, renal, immune and coagulation disorders).

Additionally, medication history, such as use of antiplatelet or

anticoagulant therapy, preoperative chemotherapy, anti-hypertensive

drugs and steroid hormones, was documented. Laboratory evaluations

included the assessments of preoperative albumin levels, hemoglobin

(Hb) levels and sodium levels, which were recorded from the last

preoperative laboratory report prior to surgery. The cut-off point

of the Hb level was defined as Hb <80 g/l, which was the

criterion for blood transfusion in the operating room.

In addition to the patient characteristics, detailed

data on surgical and anesthetic procedures were collected. These

data included the duration of surgery, the use of laparoscopy,

regional block techniques, intraoperative fluid infusion volume,

blood loss, blood transfusion, the use of vasopressor agents, the

administration of flurbiprofen axetil, the intraoperative

consumption of opioids, the maximum diameter of the tumor, the

presence of lymph node metastasis, detection of an intravascular

tumor thrombus and postoperative transfer to the ward or ICU.

Anesthetic procedure

All patients received general anesthesia, induced

with intravenous propofol (1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg), sufentanil (0.3

µg/kg) and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). Anesthesia was maintained with

the inhalation of sevoflurane or desflurane, supplemented with the

continuous infusion of propofol (100-300 µg/kg/min) and

remifentanil (0.05-0.2 µg/kg/min) to maintain a bispectral index

between 40 and 60. Flurbiprofen axetil was the only NSAID used

during the perioperative period, with its use determined by the

attending anesthesiologist and surgeon. Postoperatively, the

patients were extubated in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit or

Operating Room or transferred to the ICU with endotracheal

intubation, if necessary. Extubation criteria included the recovery

of consciousness, respiratory and circulatory stability, muscle

strength, and patients would then be returned to the ward.

Postoperative analgesia was managed (patient-controlled analgesia)

with opioids (sufentanil patient-controlled analgesia) (3 µg each,

with locking time 15 min).

Vasopressor agents such as phenylephrine (with a

dose of 50 µg) were used empirically during surgery by the

anesthesiologist, based on the initial and intraoperative blood

pressure of the patient. Between the flurbiprofen axetil group

(FBP) group and non-flurbiprofen axetil group (N-FBP), there was no

significant difference in the proportion of colon/rectal surgeries

(P=0.601) or anastomosis method (data not shown). Surgeons

determined whether to use the end-to-end or end-to-side anastomosis

method based on surgical site, with both groups operated on by the

same surgical team, eliminating potential operator bias.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of

postoperative intestinal complications within 30 days of surgery.

These complications included AL, ileus and celiac fistula. AL was

defined according to a modified Reisinger criterion, which includes

the extraluminal presence of contrast fluid, leakage with evidence

of bowel content extravasation, intraabdominal collection, or gas

on contrast-enhanced CT scan or radiographic enema, upon

re-laparotomy or during endoscopy, requiring reintervention or

treatment (16).

Ileus was defined as bowel occlusion or paralysis

preventing the forward passage of intestinal contents, leading to

accumulation proximal to the blockage site. The diagnosis was

determined by gastrointestinal surgeons in combination with imaging

examinations and clinical symptoms, which included bloating, cramps

and the retention of stool and flatus (17). Chylous ascites was defined as the

non-infectious extravasation of milky or creamy peritoneal fluid in

the drain tubes at a volume of ≥200 ml/day and a triglyceride level

≥110 mg/dl (18,19). All complications were diagnosed by

gastrointestinal surgeons through the comprehensive evaluation of

clinical symptoms, CT scans and other imaging techniques.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0

software (IBM Corp.). Continuous variables are presented as the

median (interquartile range) and compared using non-parametric

tests, specifically the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables

are expressed as percentages and analyzed using the χ2

test or Fisher's exact test. In the present study, the subjects

were divided into the FBP group and N-FBP group. Univariable

analysis was performed for the initial screening of risk factors.

Factors with P<0.1 in the univariable analysis and factors

associated with outcomes in clinical experience were included in

the multivariable analysis. The results are reported as odds ratios

(ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient demographic and baseline

characteristics

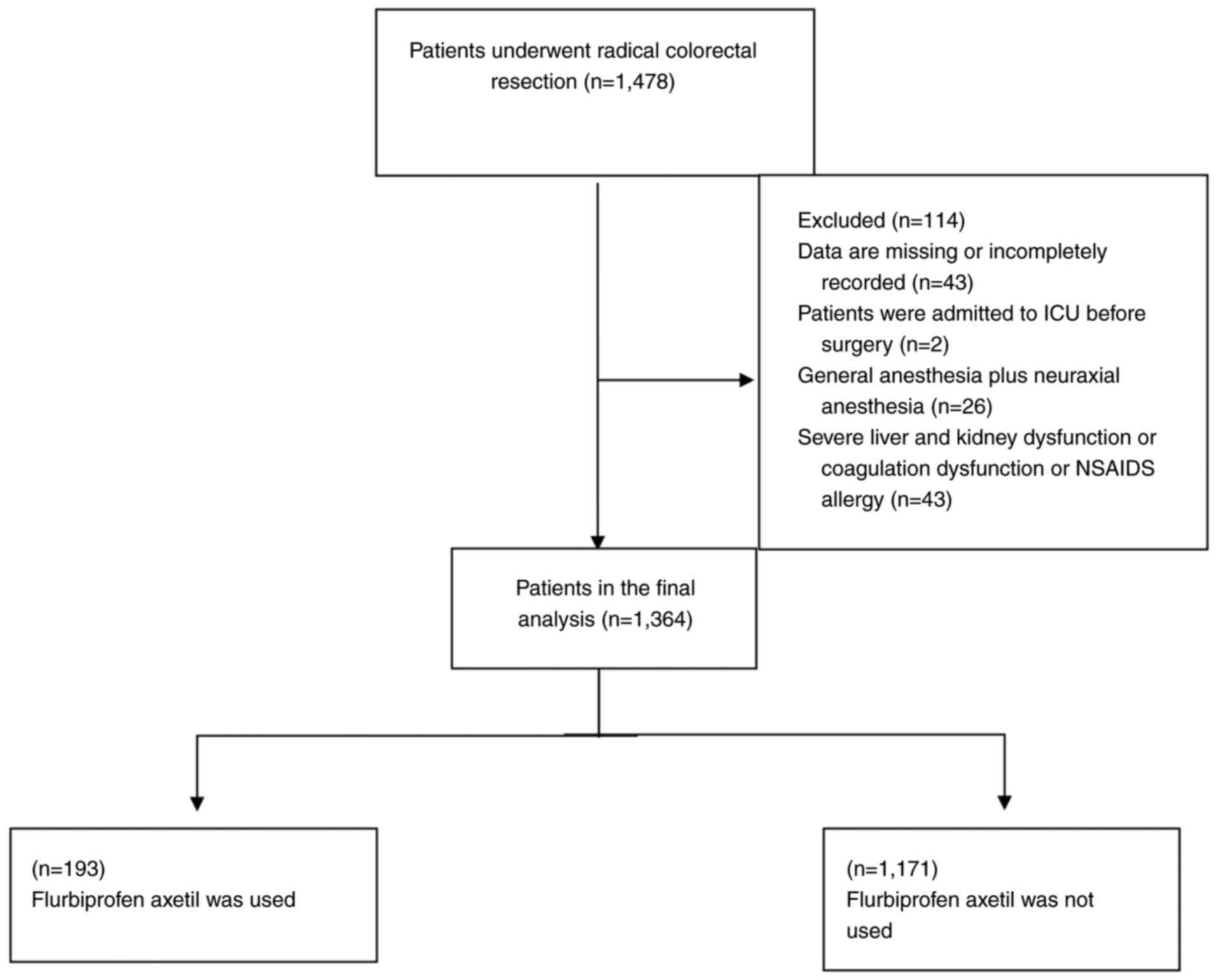

A total of 1,478 patients were included in the

study. According to the screening criteria, 114 patients were

excluded, including 43 patients with incomplete records, 2 patients

who were admitted to the ICU before the operation, 26 patients who

received general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia, and

43 patients with severe liver, kidney function or coagulation

dysfunction. Finally, a total of 1,364 patients were enrolled,

comprising 804 men and 560 women (Fig.

1). The patients were divided into two groups as follows: The

FBP group, consisting of 193 patients (14.1%) who received

flurbiprofen axetil perioperatively, and the N-FBP group, which

included 1,171 patients (85.9%) who did not receive the drug. Among

the 193 patients in the FBP group, 112 (58.0%) received

flurbiprofen axetil intraoperatively, 68 (35.2%) received it

postoperatively, and 13 (6.7%) were administered the drug during

both the intraoperative and postoperative periods. The administered

dose of flurbiprofen axetil was typically 50-100 mg during surgery

and/or 50 mg twice daily postoperatively. A comparison of the

baseline characteristics of the patients revealed no statistically

significant differences between the FBP and N-FBP groups, apart

from the difference in surgical method (P=0.007) (Table I).

| Table IComparison of patient demographics and

intraoperative findings between groups. |

Table I

Comparison of patient demographics and

intraoperative findings between groups.

| Patient data | FBP (n=193) | N-FBP (n=1,171) | P-value |

|---|

| Patient

characteristics | | | |

|

Age,

yearsa | 66 (57-76) | 66 (58-74) | 0.972 |

|

Male, n

(%) | 112 (58.0) | 692 (59.1) | 0.781 |

|

BMI, n

(%) | | | 0.188 |

|

>28

kg/m2 | 27 (14.0) | 126 (10.8) | |

|

≤28

kg/m2 | 166 (86.0) | 1,045 (89.2) | |

|

ASA

classification, n (%) | | | 0.618 |

|

Grade

III | 47 (24.4) | 305 (26.0) | |

|

Less

than grade III | 146 (75.6) | 866 (74.0) | |

| Previous history, n

(%) | | | |

|

Hypertension | 77 (39.9) | 476 (40.6) | 0.844 |

|

Diabetes | 45 (23.3) | 230 (19.6) | 0.238 |

|

Coronary

heart disease | 24 (12.4) | 131 (11.2) | 0.613 |

|

Chronic lung

disease | 4 (2.1) | 18 (1.5) | 0.811 |

|

Two or more

comorbidities | 36 (18.7) | 210 (17.9) | 0.810 |

|

Albumina | 38.8

(36.2-41.6) | 39.2

(36.7-41.5) | 0.704 |

|

Hb<80

g/l | 4 (2.1) | 32 (2.7) | 0.596 |

|

Na+a | 141.2

(139.4-143) | 141.4

(139.7-143) | 0.447 |

|

Preoperative

medication, n (%) | | | |

|

Antiplatelet

or anticoagulant therapy | 24 (12.4) | 149 (12.7) | 0.911 |

|

Chemotherapy | 27 (14.0) | 175 (14.9) | 0.729 |

|

ACEIs/ARBs | 20 (10.4) | 171 (14.6) | 0.116 |

|

Statins | 22 (11.4) | 134 (11.4) | 0.986 |

|

Other

antihypertensive drugs | 49 (25.4) | 377 (32.2) | 0.059 |

|

Diuretics | 5 (2.6) | 35 (3.0) | 0.761 |

|

Steroid

hormones | 18 (9.3) | 90 (7.7) | 0.434 |

| Surgery and

anesthesia | | | |

|

Duration, n

(%) | | | 0.506 |

|

>3

h | 122 (63.2) | 769 (65.7) | |

|

≤3

h | 71 (36.8) | 402 (34.3) | |

|

Surgical

method, n (%) | | | 0.007 |

|

Laparoscopy | 143 (74.1) | 964 (82.3) | |

|

Open

abdomen | 50 (25.9) | 207 (17.7) | |

|

Intraoperative

use of vasopressors, n (%) | 137 (71.0) | 786 (67.1) | 0.288 |

|

Intraoperative

blood transfusion, n (%) | 20 (10.4) | 87 (7.4) | 0.160 |

|

Intraoperative

fluid infusion volumea | 2.6 (2.1-3.4) | 2.6 (2.1-3.1) | 0.600 |

|

Intraoperative

blood loss, n (%) | | | 0.090 |

|

<100

ml | 102 (52.8) | 695 (59.4) | |

|

≥100

ml | 91 (47.2) | 476 (40.7) | |

|

Use regional

block, n (%) | 30 (15.5) | 173 (14.8) | 0.781 |

|

Postoperative

return, n (%) | | | 0.380 |

|

The

ward | 140 (72.5) | 885 (75.6) | |

|

ICU | 53 (27.5) | 287 (24.5) | |

|

Lymph node

metastasis, n (%) | 52 (26.9) | 355 (30.3) | 0.343 |

|

Tumor emboli

in blood vessels, n (%) | 35 (18.1) | 200 (17.1) | 0.719 |

|

Maximum

diameter of tumor, n (%) | | | 0.181 |

|

<5

cm | 117 (60.6) | 768 (65.6) | |

|

≥5

cm | 76 (39.4) | 403 (34.4) | |

|

Intraoperative

opioid consumptiona | 35 (30-40) | 35 (30-45) | 0.143 |

Intestinal complications

Postoperative intestinal complications were observed

in 89 patients, accounting for 6.5% of the study population. These

complications included ileus (45 patients; 3.3%), AL (40 patients;

2.9%) and celiac fistula (9 patients; 0.7%) (Table II).

| Table IIPostoperative intestinal-related

complications. |

Table II

Postoperative intestinal-related

complications.

| Postoperative

complications | Total, n (%) | FBP, n (%) | N-FBP, n (%) |

|---|

| Ileus | 45 (3.3) | 10 (5.2) | 35 (3.0) |

| AL | 40 (2.9) | 11 (5.7) | 29 (2.5) |

| Celiac fistula | 9 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (0.8) |

Ileus

Ileus was identified in 45 patients (3.3% of the

study population), including 10 patients (5.2%) in the FBP group

and 35 patients (3.0%) in the N-FBP group.

AL

AL was observed in 40 patients (2.9% of the study

cohort), with 11 patients in the FBP group (5.7%) and 29 patients

(2.5%) in the N-FBP group.

Celiac fistula

A total of 9 patients (0.7%) developed celiac

fistula, and none of them had received flurbiprofen axetil during

or following surgery.

Univariate analysis identified several relevant

factors, including age (P=0.030), male sex (P=0.033), preoperative

use of steroid hormones (P=0.016), perioperative use of

flurbiprofen axetil (P=0.008), duration of surgery >3 h

(P=0.003), intraoperative use of vasopressors (P=0.040), and

intraoperative opioid consumption (P=0.038). Based on the results,

a multivariate analysis was then performed. Logistic regression was

mainly used in multivariate analysis; it identified age (OR, 1.022;

95% CI, 1.002-1.042; P=0.028), perioperative use of flurbiprofen

axetil (OR, 2.072; 95% CI, 1.223-3.508; P=0.007), duration of the

surgery >3 h (OR, 2.032; 95% CI, 1.181-3.496; P=0.010) and

intraoperative consumption of opioids (OR, 1.012; 95% CI,

1.003-1.022; P=0.009) as significant risk factors for the

development of postoperative intestinal complications (Table III).

| Table IIIUnivariate and multivariate analysis

of intestinal complications. |

Table III

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of intestinal complications.

| | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| | | | 95% CI | |

|---|

| Patient data | Intestinal

complications (n=89) | No complications

(n=1,275) | Univariate

P-value | OR | Lower | Upper | P-value |

|---|

| Patient

characteristics | | | | | | | |

|

Age,

yearsa | 69 (64-76) | 66 (57-74) | 0.030 | 1.022 | 1.002 | 1.042 | 0.028 |

|

Males, n

(%) | 62 (69.7) | 742 (58.2) | 0.033 | 1.513 | 0.941 | 2.435 | 0.088 |

|

BMI, n

(%) | | | 0.733 | | | | |

|

>28

kg/m2 | 9 (10.1) | 144 (11.3) | | | | | |

|

≤28

kg/m2 | 80 (89.9) | 1,131 (88.7) | | | | | |

|

ASA, n

(%) | | | 0.796 | | | | |

|

Grade

III | 24 (27.0) | 328 (25.7) | | | | | |

|

Less

than grade III | 65 (73.0) | 947 (74.3) | | | | | |

| Previous history, n

(%) | | | | | | | |

|

Hypertension | 35 (39.3) | 518 (40.6) | 0.809 | | | | |

|

Diabetes | 18 (20.2) | 257 (20.2) | 0.988 | | | | |

|

Coronary

heart disease | 8 (9.0) | 147 (11.5) | 0.465 | | | | |

|

Chronic lung

disease | 2 (2.2) | 20 (1.6) | 0.955 | | | | |

|

Two or more

comorbidities | 15 (16.9) | 231 (18.1) | 0.764 | | | | |

|

Albumina | 39.1

(36.4-41.8) | 39.2

(36.7-41.5) | 0.776 | | | | |

|

Hb <80

g/l | 0 (0.0) | 36 (2.8) | 0.206 | | | | |

|

Na+a | 141.4

(139.2-142.8) | 141.4

(139.7-143) | 0.689 | | | | |

|

Preoperative

medication, n (%) | | | | | | | |

|

Antiplatelet

or anticoagulant therapy | 11 (12.4) | 162 (12.7) | 0.924 | | | | |

|

Chemotherapy | 18 (20.2) | 184 (14.4) | 0.137 | | | | |

|

ACEIs/ARBs | 14 (15.7) | 177 (13.9) | 0.627 | | | | |

|

Statins | 13 (14.6) | 143 (11.2) | 0.331 | | | | |

|

Other

anti-hypertensive drugs | 29 (32.6) | 397 (31.1) | 0.776 | | | | |

|

Diuretics | 4 (4.5) | 36 (2.8) | 0.563 | | | | |

|

Steroid

hormones | 13 (14.6) | 95 (7.5) | 0.016 | 1.888 | 1.000 | 3.565 | 0.050 |

| Surgery and

anesthesia, n (%) | | | | | | | |

|

Perioperative

use of flurbiprofen axetil | 21 (23.6) | 172 (13.5) | 0.008 | 2.072 | 1.223 | 3.508 | 0.007 |

|

Duration | | | 0.003 | 2.032 | 1.181 | 3.496 | 0.010 |

|

>3

h | 71 (79.8) | | | | | | |

|

≤3

h | 18 (20.2) | 455 (35.7) | | | | | |

|

Surgical

method | | | 0.829 | | | | |

|

Laparoscopy | 73 (82.0) | 1,034 (81.1) | | | | | |

|

Open

abdomen | 16 (18.0) | 241 (18.9) | | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

use of vasopressors | 69 (77.5) | 854 (67.0) | 0.040 | 1.534 | 0.907 | 2.594 | 0.111 |

|

Intraoperative

blood transfusion | 5 (5.6) | 102 (8.0) | 0.419 | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

fluid infusion volumea | 2.6 (2.3-3.1) | 2.6 (2.1-3.1) | 0.905 | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

blood loss | | | 0.657 | | | | |

|

<100

ml | 54 (60.7) | 743 (58.3) | | | | | |

|

≥100

ml | 35 (39.3) | 532 (41.7) | | | | | |

|

Use regional

block during operation | 8 (9.0) | 195 (15.3) | 0.106 | | | | |

|

Postoperative

return | | | 0.764 | | | | |

|

The

ward | 68 (76.4) | 956 (75.0) | | | | | |

|

ICU | 21 (23.6) | 319 (25.0) | | | | | |

| Surgery and

anesthesia, n (%) | | | | | | | |

|

Lymph node

metastasis | 21 (23.6) | 386 (30.3) | 0.183 | | | | |

|

Tumor emboli

in blood vessels | 17 (19.1) | 218 (17.1) | 0.629 | | | | |

|

Maximum

diameter of tumor | | | 0.328 | | | | |

|

<5

cm | 62 (69.7) | 823 (64.5) | | | | | |

|

≥5

cm | 27 (30.3) | 452 (35.5) | | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

opioid consumption | 40 (30-50) | 35 (30-45) | 0.038 | 1.012 | 1.003 | 1.022 | 0.009 |

Discussion

In the present study, all four statistically

significant factors exhibited an OR >1, indicating that an

advanced age, perioperative flurbiprofen axetil use, a prolonged

duration of surgery and increased opioid consumption were

identified as potential risk factors for postoperative intestinal

complications. The present study investigated the incidence of

intestinal complications, including AL, ileus and chylous fistula,

which affect the prognosis of patients undergoing colorectal

surgery. These findings revealed that age (P=0.028), the

perioperative use of flurbiprofen axetil (P=0.007), duration of the

surgery >3 h (P=0.010) and intraoperative opioid consumption

(P=0.009) are significant risk factors for the development of these

complications. Among these, the perioperative use of flurbiprofen

axetil is an influencing factor that has not been previously

mentioned, at least to the best of our knowledge.

NSAIDs are among the most widely used medications

globally, both via prescription and over-the-counter, for treating

fever, acute or chronic pain, and inflammatory conditions such as

rheumatic diseases. It is estimated that >30 million individuals

use NSAIDs daily (20). These

drugs inhibit COXs, key enzymes involved in the synthesis of

prostaglandins from arachidonic acid. Traditional NSAIDs inhibit

both COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms, while selective NSAIDs primarily

inhibit COX-2, and low-dose aspirin specifically inhibits

COX-1(21).

In colorectal surgery, NSAIDs are often utilized for

their opioid-sparing effects. Numerous epidemiological studies have

demonstrated that the long-term use of NSAIDs is associated with a

significant reduction in cancer incidence and can delay the

progression of malignant disease. Additionally, NSAID use has been

linked to a reduced risk of cancer-related mortality and distant

metastasis (22,23). As a non-selective COX inhibitor,

flurbiprofen axetil is commonly used in postoperative analgesia.

However, studies on the impact of NSAIDs on bowel function recovery

have indicated that these drugs may not be entirely safe for

patients undergoing radical colorectal surgery (24-26).

Specifically, the early postoperative use of NSAIDs has been

significantly associated with AL in patients undergoing colorectal

cancer surgery at high-volume tertiary care centers (27). Similar findings have been reported

in a meta-analysis (28). Another

study examined the prophylactic use of flurbiprofen to prevent

mesenteric traction syndrome during abdominal surgery. It reported

an increased risk of postoperative leakage or bleeding in patients

who did not develop mesenteric traction syndrome but received

flurbiprofen axetil prophylactically (29).

The results of the present study align with these

findings, indicating that the perioperative use of flurbiprofen

axetil is associated with an increased risk of intestinal

complications following radical colorectal surgery. Flurbiprofen

axetil may impair the intestinal healing process by suppressing

COX-2 expression, thereby increasing the risk of intestinal

complications. Another proposed mechanism is that NSAID treatment

may reduce collagen production and impair angiogenesis, further

contributing to these complications (30). However, with regard to its safety

in patients, particularly in those undergoing gastrointestinal

surgery, studies have demonstrated differential results. A

retrospective cohort study investigated the short-term

postoperative use of flurbiprofen in patients undergoing elective

gastrointestinal surgery for cancer resection. The study found no

significant increase in AL rates among patients who received

flurbiprofen compared with that in patients who did not (1.62% vs.

1.46%; P=0.70) (31). However,

only postoperative use was included in the study, and flurbiprofen

axetil is often used intraoperatively, when patients have not yet

left the operating room. Moreover, AL is not the only related

complication that raises concern.

Furthermore, the present study suggests that older

patients, a prolonged surgical duration and the increased use of

opioids during the surgery may lead to an increased risk of

developing intestinal complications following colorectal surgery.

These observations are consistent with the findings of previous

studies (32,33). An advanced age has long been

recognized as an independent risk factor for postoperative

complications across various surgical procedures. Elderly patients

typically present with more preoperative comorbidities, decreased

physiological resilience to anesthesia and surgical stress, and

slower postoperative recovery compared with younger individuals. As

a result, they are more susceptible to postoperative complications,

often related to underlying health conditions or infections

(34). In the present study, the

findings suggest that advanced age may contribute to the risk of

postoperative intestinal complications. This may possibly be due to

impaired baseline bowel function and delayed gastrointestinal

recovery in older patients.

In addition to age, a prolonged surgical duration

(>3 h) and excessive perioperative opioid use were also

identified as significant contributors to postoperative intestinal

complications. Unlike NSAIDs, whose administration generally

follows a standardized protocol, opioid consumption tends to

increase with the length and complexity of surgery. Notably,

collinearity diagnostics indicated no significant multicollinearity

between operative time and opioid use, suggesting these variables

likely exert independent effects or interact with distinct

confounding factors. Therefore, the multivariate analysis performed

herein incorporated a comprehensive set of covariates to improve

the robustness and interpretability of the model.

Surgical duration plays a crucial role in

determining postoperative outcomes. Even with intraoperative fluid

management, extended operative times often indicate greater

surgical complexity and are associated with increased fluid loss,

more extensive tissue trauma and slower postoperative recovery

(35). At the same time, opioid

use contributes to gastrointestinal side-effects, such as nausea

and vomiting, and inhibits bowel motility, thereby delaying the

return of normal gastrointestinal function (36).

It is important to acknowledge the potential

limitations of the present single-center study. Although real-world

data were used to explore the association between flurbiprofen

axetil and intestinal complications, the design of the study may

introduce certain biases. Flurbiprofen axetil was the only NSAID

included in the present study, and it was administered

intraoperatively or postoperatively in single or intermittent doses

ranging from 50 to 100 mg. The lack of a standardized dosage

regimen for all patients complicates the interpretation of whether

dosage directly affects the incidence or severity of postoperative

complications. Therefore, further research is required to provide

more robust evidence on the association between NSAIDs and

intestinal complications.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

the perioperative use of flurbiprofen axetil may increase the risk

of developing postoperative intestinal complications in patients

undergoing radical colorectal resection. Further studies are

warranted in order to establish standardized protocols for the use

of NSAIDs in this patient population to minimize these risks.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Key

Research and Development Program of China (grant no.

2018YFC2001905) and the Jie-ping Wu Fund (grant no. 2016-Z-24).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YF and XT were responsible for the overall content

as the guarantors. YF proposed the research conception and designed

the study. WD drafted the manuscript and collected the data. XT

performed the data analysis and revised the manuscript. KS

contributed to the diagnosis of the complications described in the

study. WR provided advice on the study design and statistical

analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

WD and XT confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of Peking University People's Hospital (Beijing, China;

approval no. 2022PHB131-001). All methods were performed according

to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM

and Wallace MB: Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 394:1467–1480.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kijima S, Sasaki T, Nagata K, Utano K,

Lefor AT and Sugimoto H: Preoperative evaluation of colorectal

cancer using CT colonography, MRI, and PET/CT. World J

Gastroenterol. 20:16964–16975. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung

H and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 75:10–45.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Chadi SA, Fingerhut A, Berho M, DeMeester

SR, Fleshman JW, Hyman NH, Margolin DA, Martz JE, McLemore EC,

Molena D, et al: Emerging trends in the etiology, prevention, and

treatment of gastrointestinal anastomotic leakage. J Gastrointest

Surg. 20:2035–2051. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cunningham DJ, LaRose M, Zhang G, Patel P,

Paniagua A, Gadsden J and Gage MJ: Regional anesthesia associated

with decreased inpatient and outpatient opioid demand in tibial

plateau fracture surgery. Anesth Analg. 134:1072–1081.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Abdel Shaheed C, Hayes C, Maher CG,

Ballantyne JC, Underwood M, McLachlan AJ, Martin JH, Narayan SW and

Sidhom MA: Opioid analgesics for nociceptive cancer pain: A

comprehensive review. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:286–313. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Parfait M, Rohrs E, Joussellin V, Mayaux

J, Decavèle M, Reynolds S, Similowski T, Demoule A and Dres M: An

initial investigation of diaphragm neurostimulation in patients

with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology.

140:483–494. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Halvey EJ, Haslam N and Mariano ER:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the perioperative period.

BJA Educ. 23:440–447. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren

J, Demartines N, Francis N, Rockall TA, Young-Fadok TM, Hill AG,

Soop M, et al: Guidelines for perioperative care in elective

colorectal surgery: Enhanced recovery after surgery

(ERAS®) society recommendations: 2018. World J Surg.

43:659–695. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Rutegård J and Rutegård M: Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs in colorectal surgery: A risk factor for

anastomotic complications? World J Gastrointest Surg. 4:278–280.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang H, Liu T, Li Q, Cui R, Fan X, Tong Y,

Ma S, Liu C and Zhang J: NSAID treatment before and on the early

onset of acute kidney injury had an opposite effect on the outcome

of patients With AKI. Front Pharmacol. 13(843210)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Klein M, Gögenur I and Rosenberg J:

Postoperative use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in

patients with anastomotic leakage requiring reoperation after

colorectal resection: Cohort study based on prospective data. BMJ.

345(e6166)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kumpulainen E, Välitalo P, Kokki M,

Lehtonen M, Hooker A, Ranta VP and Kokki H: Plasma and

cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of flurbiprofen in children.

Br J Clin Pharmacol. 70:557–566. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wan Z, Chu C, Zhou R and Que B: Effects of

oxycodone combined with flurbiprofen axetil on postoperative

analgesia and immune function in patients undergoing radical

resection of colorectal cancer. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev.

10:251–259. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Keats AS: The ASA classification of

physical status-a recapitulation. Anesthesiology. 49:233–236.

1978.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Reisinger KW, Poeze M, Hulsewé KW, van

Acker BA, van Bijnen AA, Hoofwijk AG, Stoot JH and Derikx JP:

Accurate prediction of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery

using plasma markers for intestinal damage and inflammation. J Am

Coll Surg. 219:744–751. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Vilz TO, Stoffels B, Strassburg C, Schild

HH and Kalff JC: Ileus in adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 114:508–518.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Besselink MG, van Rijssen LB, Bassi C,

Dervenis C, Montorsi M, Adham M, Asbun HJ, Bockhorn M, Strobel O,

Büchler MW, et al: Definition and classification of chyle leak

after pancreatic operation: A consensus statement by the

international study group on pancreatic surgery. Surgery.

161:365–372. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Baek SJ, Kim SH, Kwak JM and Kim J:

Incidence and risk factors of chylous ascites after colorectal

cancer surgery. Am J Surg. 206:555–559. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Singh G and Triadafilopoulos G:

Epidemiology of NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications. J

Rheumatol Suppl. 56:18–24. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Smith WL, DeWitt DL and Garavito RM:

Cyclooxygenases: Structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu

Rev Biochem. 69:145–182. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gurpinar E, Grizzle WE and Piazza GA:

NSAIDs inhibit tumorigenesis, but how? Clin Cancer Res.

20:1104–1113. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Schack A, Fransgaard T, Klein MF and

Gögenur I: Perioperative use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs decreases the risk of recurrence of cancer after colorectal

resection: A cohort study based on prospective data. Ann Surg

Oncol. 26:3826–3837. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

García-Rayado G, Navarro M and Lanas A:

NSAID induced gastrointestinal damage and designing GI-sparing

NSAIDs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 11:1031–1043. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hakkarainen TW, Steele SR, Bastaworous A,

Dellinger EP, Farrokhi E, Farjah F, Florence M, Helton S, Horton M,

Pietro M, et al: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk

for anastomotic failure: A report from Washington State's surgical

care and outcomes assessment program (SCOAP). JAMA Surg.

150:223–228. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Haddad NN, Bruns BR, Enniss TM, Turay D,

Sakran JV, Fathalizadeh A, Arnold K, Murry JS, Carrick MM,

Hernandez MC, et al: Perioperative use of nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of anastomotic failure in

emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 83:657–661.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ju JW, Lee HJ, Kim MJ, Ryoo SB, Kim WH,

Jeong SY, Park KJ and Park JW: Postoperative NSAIDs use and the

risk of anastomotic leakage after restorative resection for

colorectal cancer. Asian J Surg. 46:4749–4754. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bhangu A, Singh P, Fitzgerald JE, Slesser

A and Tekkis P: Postoperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

and risk of anastomotic leak: Meta-analysis of clinical and

experimental studies. World J Surg. 38:2247–2257. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Suzuki M, Shibata J, Mochizuki T and Bito

H: Contribution of prophylactic administration of flurbiprofen for

mesenteric traction syndrome to postoperative leakage or bleeding

in gastrointestinal surgery: A retrospective observational study.

Langenbecks Arch Surg. 408(337)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Klein M, Krarup PM, Kongsbak MB, Agren MS,

Gögenur I, Jorgensen LN and Rosenberg J: Effect of postoperative

diclofenac on anastomotic healing, skin wounds and subcutaneous

collagen accumulation: A randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled,

experimental study. Eur Surg Res. 48:73–78. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Nie H, Hao Y, Feng X, Ma L, Ma Y, Zhang Z,

Han X, Zhang JZ, Zhang P, Zhao Q and Dong H: Postoperative

short-term use of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

flurbiprofen did not increase the anastomotic leakage rate in

patients undergoing elective gastrointestinal surgery-a

retrospective cohort study. Perioper Med (Lond).

11(38)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Liu XR, Liu F, Li ZW, Liu XY, Zhang W and

Peng D: The risk of postoperative complications is higher in stage

I-III colorectal cancer patients with previous abdominal surgery: A

propensity score matching analysis. Clin Transl Oncol.

25:3471–3478. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kang T, Kim HO, Kim H, Chun HK, Han WK and

Jung KU: Age over 80 is a possible risk factor for postoperative

morbidity after a laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer. Ann

Coloproctol. 31:228–234. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Johnson AG, Quinn DI and Day RO:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Med J Aust. 163:155–158.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Scott CF Jr: Length of operation and

morbidity: Is there a relationships? Plast Reconstr Surg.

69:1017–1021. 1982.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Akbarali HI and Dewey WL: Gastrointestinal

motility, dysbiosis and opioid-induced tolerance: Is there a link?

Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:323–324. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|