Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common clinical

condition that is characterized by a rapid decline in renal

function (1). AKI can lead to

incomplete renal repair, persistent chronic inflammation and

progressive fibrosis, all of which can lead to chronic kidney

disease and end-stage renal disease (2). Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) is a major

pathogenic factor for AKI (3).

However, the mechanism of tissue damage and repair during AKI is

still unclear and the immune inflammatory response mediating tissue

damage and fibrosis has become an interest in research worldwide

(4,5).

The bioactive alkaloid tetramethylpyrazine (TMP) is

found in the Chinese herbal medicine Chuanxiong and has been proven

to possess several pharmacological properties in previous studies

(6). TMP has been shown to have

physiological properties, including antioxidative,

anti-inflammatory, anti-calcium antagonism and anti-apoptotic

effects. Furthermore TMP has been implicated in autophagy

regulation, vasodilation, angiogenesis regulation, mitochondrial

damage suppression, endothelial protection, reduction of the

proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells, and

neuroprotection (6-8).

Clinically, TMP is used to treat cardiovascular, cerebrovascular

and chronic kidney diseases due to its ability to enhance blood

flow and microcirculation (9-11);

however, its therapeutic molecular target is not clear. Previous

studies from our group have shown that TMP ameliorates AKI to a

certain extent by inducing autophagy, which can downregulate

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein

2-mediated inflammation; TMP may also attenuate AKI by inhibiting

nucleotide-oligomerization domain-like receptor 3 inflammasome

(12,13). Furthermore, previous studies have

demonstrated that TMP can inhibit the proliferation and

infiltration of cancer cells by blocking the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway (14,15).

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a signaling

pathway, that has been relatively well preserved throughout

evolution, which is essential for the growth and development of the

body (16). The abnormal

activation of this signaling pathway can lead to a variety of

diseases, including kidney and cardiovascular diseases and tumors

(17,18). Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway has been shown to be involved in kidney injury

caused by AKI, glomerular disease, diabetic nephropathy, renal

fibrosis and cystic kidney disease (19-21).

In AKI, the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway has a

dual effect. Moderate activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway is beneficial to the regeneration of renal tubular

epithelial cells; however, excessive activation can promote the

progression of renal injury to chronic fibrosis (22,23).

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is controlled by

a number of proteins, including dickkopf-1 (DKK1) (16). Secretion of the glycoprotein DKK1

inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activity by binding to

cell membrane receptors, such as low-density lipoprotein

receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) and Kremen 1, and mediates

endocytosis (24,25). Chronic kidney disease is associated

with DKK1 as it promotes accumulation of mesangial cell matrix and

renal dysfunction in response to hyperglycemia (26). In lupus nephritis, increased renal

Wnt activity is accompanied by elevated DKK1 levels, and DKK1

elevation contributes to renal injury by promoting apoptosis and

increasing the extracellular immunogenic chromatin load (27). Furthermore, DKK1 notably inhibits

fibrosis in chronic kidney injury, suggesting that this protein

might be a therapeutic target for fibrosis (28,29).

However, the role of DKK1 in AKI has not yet been discovered.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first to focus on the regulatory effect of the traditional

Chinese medicine derivative TMP on DKK1 and the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway, and to investigate its effect on preventing AKI.

In the present study, a rat model was used to determine the

regulatory effect of TMP on DKK1 and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway using cell biology and molecular immunology techniques,

with the aim of revealing the mechanism of TMP in alleviating AKI

and promoting the regeneration and recovery of renal cells.

Materials and methods

Animal studies

Animal experiments were conducted in compliance with

the guidelines outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide

for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (30) and was approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Binzhou Medical University

(Yantai, China; approval no. 2020-07). A total of 18 male

Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (weight, 260-300 g; age, 8 weeks) were

purchased from the Animal Experimental Center of Shandong

University (Jinan, China). All animals were housed at a constant

temperature of 24˚C with a humidity of 55%, under a 12-h light/dark

cycle, and had unrestricted access to water and food. I/R models

were established using rats anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium

(40 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally (31). Subsequently, the I/R injury model

was established in SD rats by clamping the bilateral renal pedicle

with non-traumatic microvascular clamps as previously described

(12); serum creatinine (SCr),

blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels and morphological examinations

were used to assess the success of the model establishment. The

rats were randomly divided into the following groups (n=6/group):

Sham, kidney I/R and kidney I/R with TMP treatment (I/R + TMP). The

sample sizes for the study were determined based on the resource

equation method (32). In the sham

group, the renal artery was isolated without ischemic treatment. In

the I/R + TMP group, TMP hydrochloride (40 mg/kg body weight;

Harbin Medisan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was administered by

intraperitoneal injection immediately following reperfusion, at 6 h

intervals (12,13). Following completion of the

treatment for 24 h, all rats were deeply anesthetized by

intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg) and

subsequently sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

The following criteria were used to define the

humane endpoints for the present study: i) Lack of movement or

unresponsiveness to gentle stimuli; ii) respiratory distress

(typical symptoms include drooling from the mouth or nose and/or

cyanosis); iii) diarrhea or urinary incontinence; iv) weight loss

of >20% compared with the pre-experiment body weight; v)

inability to eat or drink; vi) persistent seizures or stereotyped

behavior (in the absence of external stimuli, rats exhibited

spontaneous rotation, digging, jumping and grooming behaviors); and

vii) skin lesions covering >30% of the body or signs of purulent

infection. The surgical procedure was uneventful, with no rats

sacrificed early due to reaching humane endpoints.

Death was verified by loss of corneal reflex, a lack

of response to a firm toe pinch, and observation of cardiac and

respiratory arrest. Subsequently, kidney tissues and blood samples

from the heart were collected. Parts of the kidney tissues were

stored at -80˚C for protein detection, whereas others were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde at 4˚C for 24 h, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned at 4-µm thickness for morphological detection. The blood

samples were used for the detection of the biochemical indicators

of renal injury.

Morphological examinations

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was

conducted on paraffin-embedded 4-µm kidney tissue sections.

Sections were dewaxed in xylene, stained with hematoxylin for 5 min

at room temperature, and then placed in distilled water for 10-30

sec. Following this, the tissue sections were incubated in 1%

hydrochloric acid alcohol for 3 sec then washed with running water

for 10 min. Finally, the sections were stained with eosin for 10

min at room temperature then dehydrated and sealed with neutral

gum. Tubular injury of the cortex or the outer medulla was based on

epithelial necrosis, vacuolization or tubular dilatation and was

scored as follows: 0, none; 1, 1-10%; 2, 11-25%; 3, 26-45%; 4,

46-75%; 5, >75%. For each section, ≥10 fields were examined

under magnification x200. The histological scoring was performed

blindly. Visualization was performed using a Leica DM 6000 B light

microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc.).

Renal function test

Blood was collected from the heart of the animals

after euthanasia and the samples were allowed to stand for 30 min.

Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 4˚C at 1,000 x g for

10 min and the serum was separated. An automatic biochemical

analyzer was used to detect SCr and BUN.

Immunohistochemical (IHC)

staining

IHC staining was performed on paraffin-embedded 4-µm

kidney tissue sections. Sections were dewaxed and placed in citrate

buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval; briefly, samples

were placed in a microwave, boiled on high heat for 4 min then

allowed to stand for 5 min, this was followed by a further 1 min at

medium heat then allowed to stand for 5 min. Subsequently, the

samples were cooled to room temperature and washed three times with

PBS (5 min each). The sections were then incubated with 3%

H2O2 at room temperature for 20 min to remove

endogenous peroxidase activity and washed three times with PBS (5

min each). The sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 1 h and incubated with the following primary

antibodies at 4˚C overnight: DKK1 (cat. no. ab109416; 1:250;

Abcam), Wnt1 (cat. no. ab15251; 1:100; Abcam), β-catenin (cat. no.

WL0962a; 1:200; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), caspase-3 (cat. no. WL04004;

1:200; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), Bax (cat. no. ER0907; 1:200; HUABIO)

and Bcl-2 (cat. no. ET1702-53; 1:200; HUABIO). The following day,

the slides were rewarmed for 45 min at room temperature and washed

three times with PBS (3 min each) to remove unbound primary

antibodies. The sections were then incubated with a horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or mouse secondary

antibody (undiluted; cat. no. PV-6000; OriGene Technologies, Inc.)

for 2 h at room temperature, and washed three times with PBS (3 min

each) to wash off the unbound secondary antibody. Subsequently,

3,3'-diaminobenzidine staining was performed at room temperature in

accordance with the kit's instructions (cat. no. ZLI-9018; OriGene

Technologies, Inc.). Tap water was used to terminate the reaction

and hematoxylin staining was used to stain the cellular nuclei at

room temperature for 5 min followed by rinsing in tap water.

Sections were differentiated in 1% hydrochloric acid-alcohol for

1-3 sec, rinsed in tap water for 10 min to achieve bluing,

dehydrated and cleared in xylene. The sections were sealed with

neutral gum and visualized using a Leica DM 6000 B light microscope

(Leica Microsystems, Inc.). ImageJ software (version 1.8.0;

National Institutes of Health) was used for

semi-quantification.

TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was carried out on paraffin-embedded

4-µm kidney tissue sections. According to the instructions of the

TUNEL kit (Roche Diagnostics), the sections were dewaxed, 20 µg/ml

DNase-free proteinase K was added dropwise, and sections were

incubated at 37˚C for 15-30 min, and then washed with PBS three

times. Subsequently the samples were incubated with 3%

H2O2 at room temperature for 20 min to

inactivate the endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by washing

with PBS three times. Following this, 50 µl TdT and 450 µl

fluorescein-labeled dUTP was mixed as biotin labeling solution and

added to the sections at 37˚C for 1 h in a dark box. Cellular

nuclei were stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (cat. no.

C1006; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature for

5 min. After washing with PBS, slides were incubated with

anti-fluorescence quenching reagent to seal the slides. A

fluorescence microscope was used to observe the samples.

Western blot analysis

The renal cortex was homogenized in ice-cold

radioimmunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing 1 mM

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The total amount of protein extracted was

determined with the BCA Protein Assay kit (cat. no. P0010; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). In each lane, 40 µg extracted protein

was loaded, separated by 8-10% sodium dodecyl sulfate

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto

polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (MilliporeSigma). The membranes

were blocked using 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h.

Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies

overnight at 4˚C, washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. SA00001-1; 1:5,000; ProteinTech Group,

Inc.) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. SA00001-2;

1:5,000; ProteinTech Group, Inc.) at room temperature for 2 h. The

protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence

detection system (Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.) and

Millipore Immobilon ECL (MilliporeSigma). Western blot bands were

semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health). The following primary antibodies were used

in the present study: DKK1 (cat. no. ab109416; 1:1,000; Abcam),

Wnt1 (cat. no. ab15251; 1:1,000; Abcam), β-catenin (cat. no.

WL0962a; 1:1,000; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), caspase-3 (cat. no.

WL04004; 1:1,000; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), cleaved caspase-3 (cat. no.

WL01992; 1:1,000; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.), Bcl-2 (cat. no. ET1603-11;

1:1,000; HUABIO) and β-actin (cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; 1:5,000;

ProteinTech Group, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

The renal tubular pathological injury score data are

presented as the median (IQR), and were analyzed using

Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's post hoc test. The other data are

presented as the mean ± SEM, and the significance of differences in

among the groups was examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan's

or Tukey's post hoc test. GraphPad Prism 9 (Dotmatics) was used for

statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

TMP protects against AKI by

alleviating renal tubular pathological injury and improving renal

function following I/R in a rat model

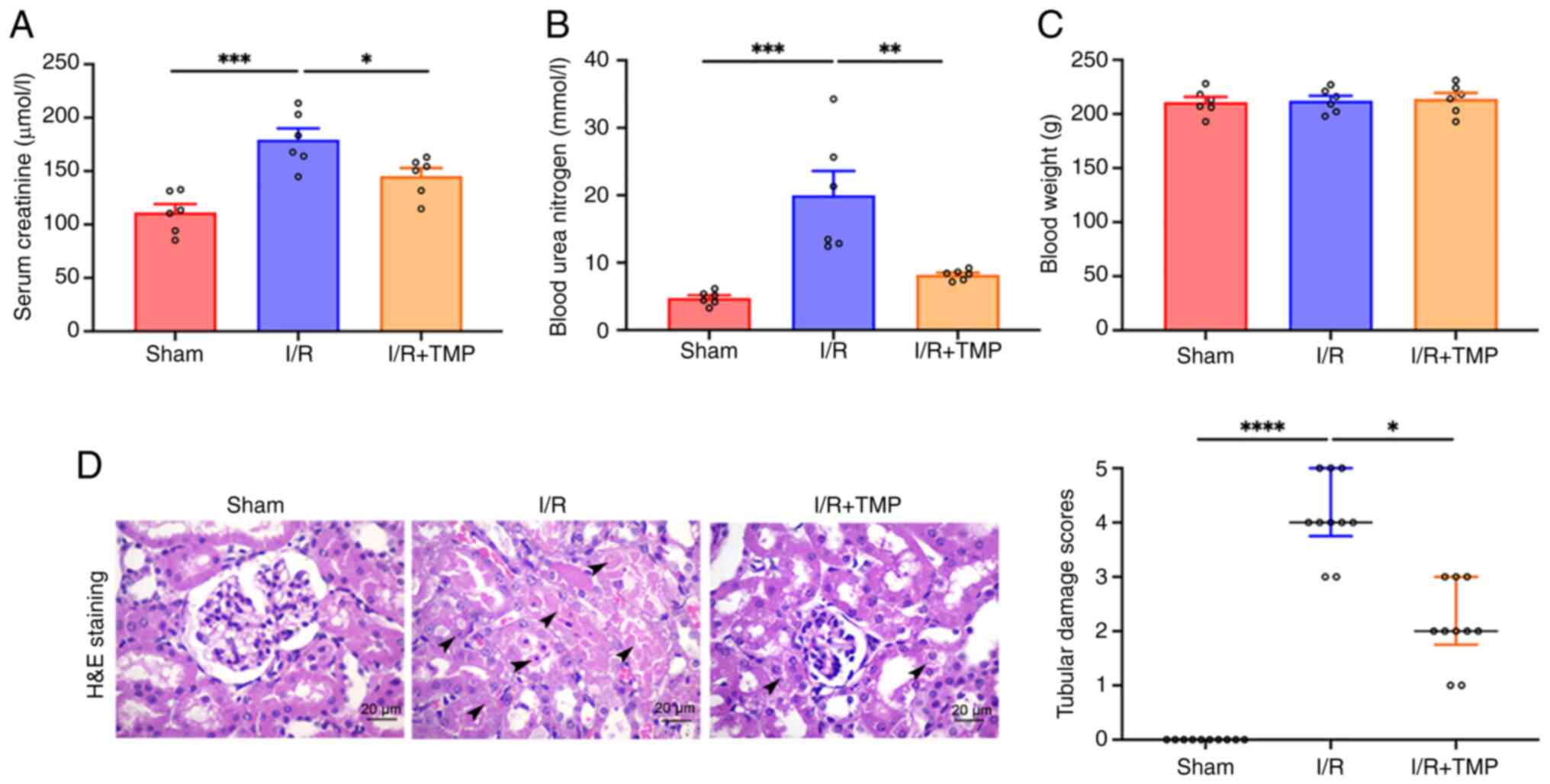

The results of SCr and BUN quantification indicated

that compared with in the sham group, the SCr and BUN levels of the

rats in the I/R group were significantly increased (Fig. 1A and B). By contrast, the SCr and BUN levels of

the rats in the I/R + TMP group were significantly decreased

compared with the levels in the I/R group, indicating that TMP

treatment could reduce I/R kidney injury. No significant difference

was noted in the body weight of rats in the I/R and the I/R + TMP

groups compared with that in the sham group (Fig. 1C). H&E staining indicated that

the glomeruli and renal tubules in the sham operation group were

intact without apparent morphological abnormalities, whereas

H&E staining in the I/R group indicated swelling, vacuolar

degeneration, necrosis and shedding, and cast formation in tubular

lumen (Fig. 1D). In the I/R + TMP

group, the aforementioned pathological changes were alleviated, and

the course of the disease was decelerated. Double-blind analysis of

renal tubular pathological injury scores by pathologists revealed

that TMP could significantly alleviate I/R renal injury in

rats.

TMP promotes the expression of DKK1 in

the renal tissues of rats following I/R

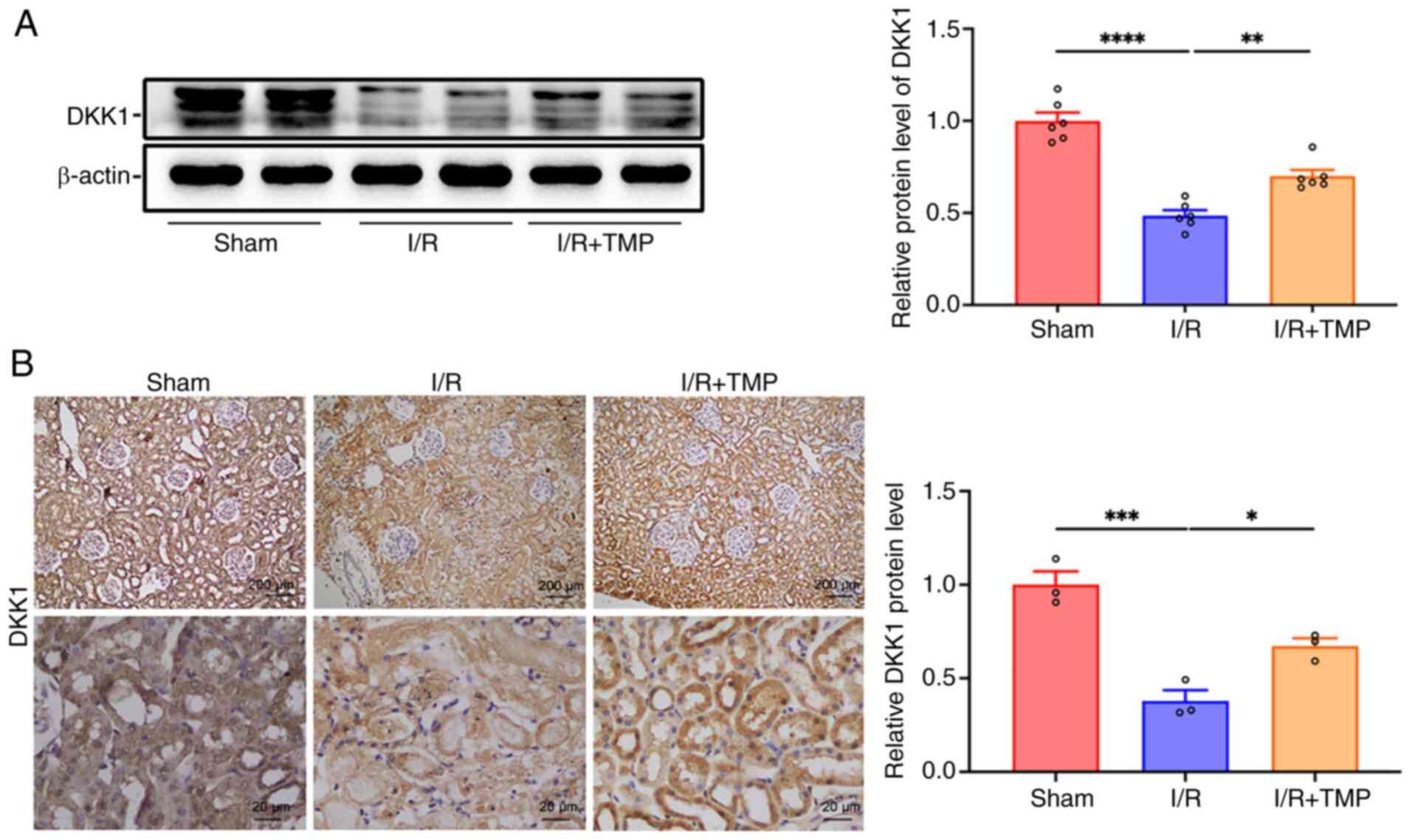

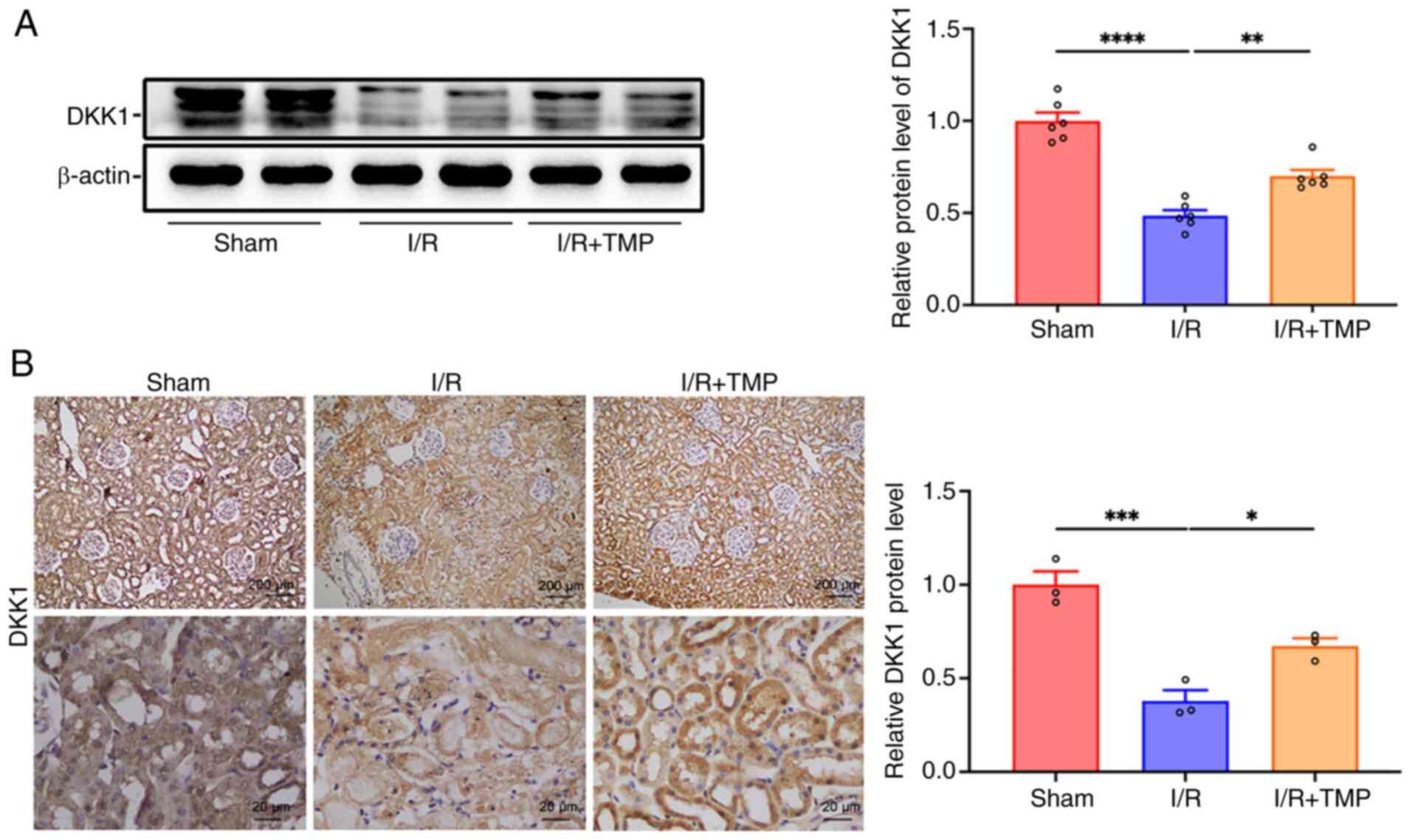

Western blot analysis revealed that the protein

expression levels of DKK1 in the I/R group were significantly lower

than those in the sham group, whereas they were significantly

increased following treatment with TMP compared with those in the

I/R group (Fig. 2A). Furthermore,

IHC analysis indicated that the expression levels of DKK1 in the

I/R group were significantly lower than those in the sham group,

whereas the expression levels of DKK1 were significantly increased

following treatment with TMP compared with the expression levels in

the I/R group (Fig. 2B). The

results of the IHC analysis were consistent with the results of the

western blot analysis. TMP significantly increased the expression

levels of DKK1 in the kidney tissues of rats following I/R.

| Figure 2TMP promotes the expression of DKK1

in the renal tissue of rats following I/R. (A) Representative

western blots and semi-quantified data showing the expression of

DKK1 in the renal tissue of rats in the sham, I/R and I/R + TMP

groups. n=6. (B) Representative IHC images of DKK1 in the renal

tissue of rats in the sham, I/R and I/R + TMP groups, and

semi-quantification. n=3. IHC images: Top row, scale bars, 200 µm,

magnification, x40; bottom row, scale bars, 20 µm, magnification,

x400. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. I/R,

ischemia-reperfusion; TMP, tetramethylpyrazine; DKK1, dickkopf-1;

IHC, immunohistochemistry. |

TMP activates the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway in the kidney tissues of rats following I/R

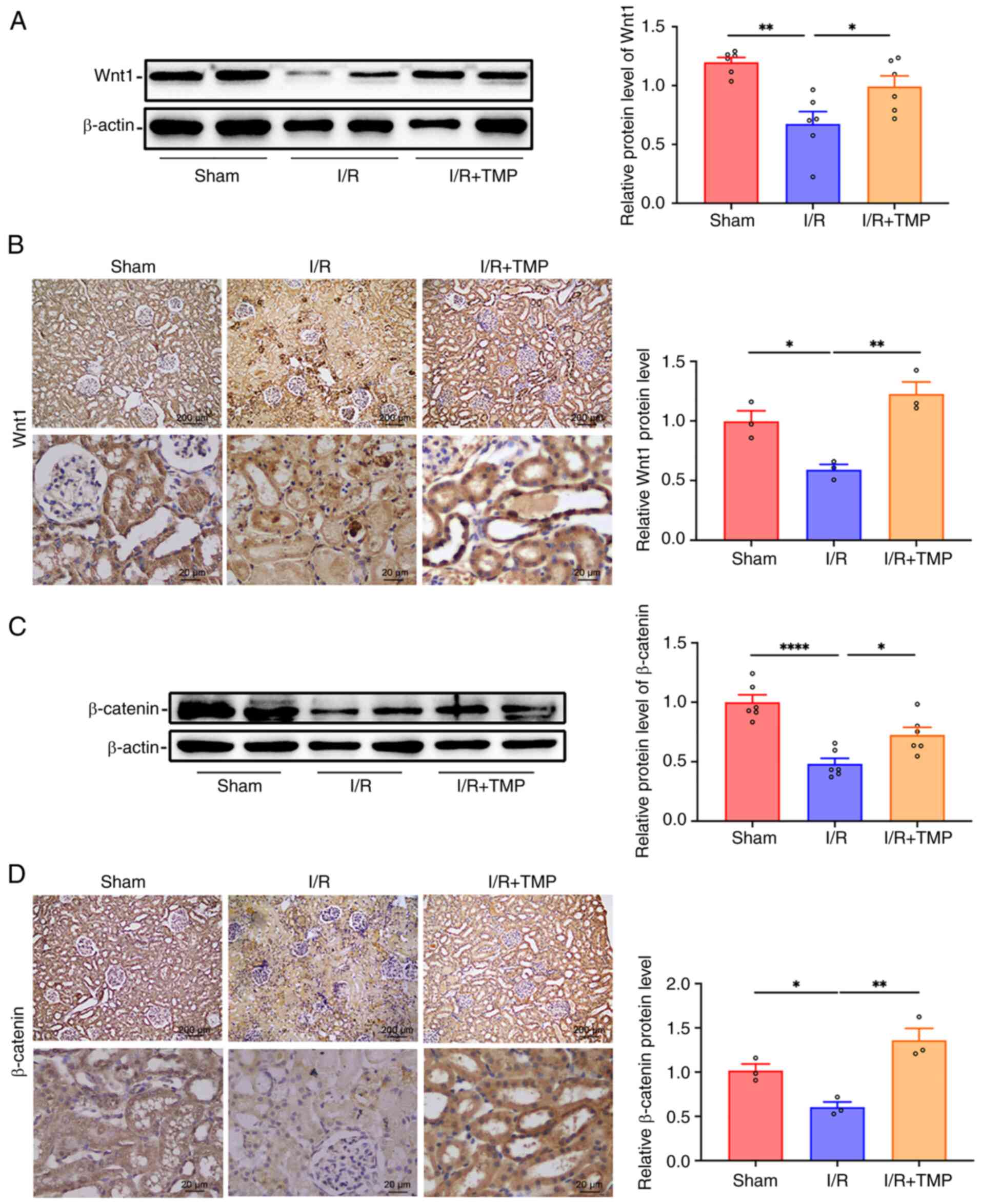

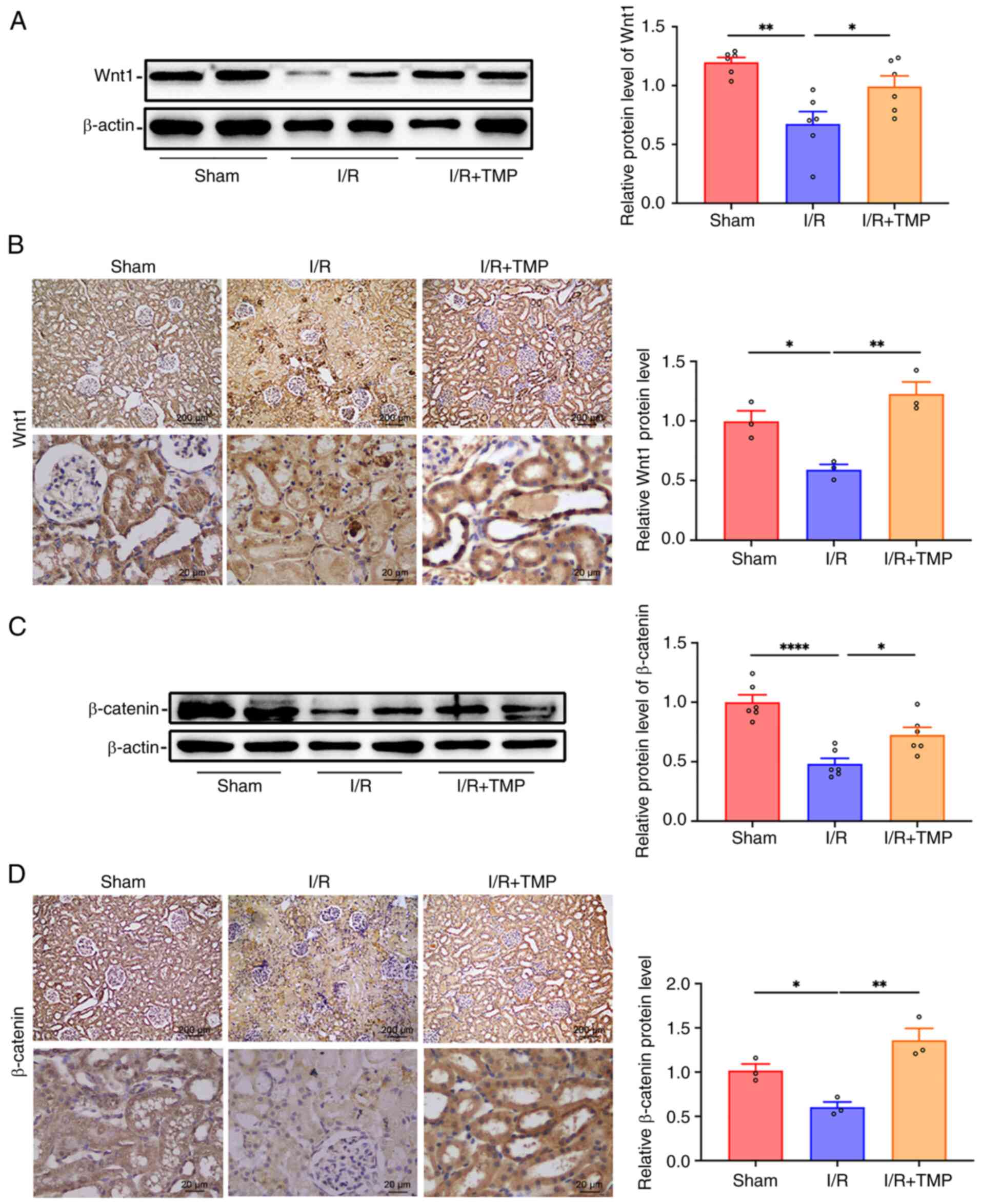

Western blot analysis of Wnt1 expression in the

renal tissues of each group indicated that compared with in the

sham group, the protein expression levels of Wnt1 were

significantly decreased in the renal tissues of the I/R group;

however, following treatment with TMP, the protein expression

levels of Wnt1 in the renal tissues of the I/R + TMP group were

significantly increased compared with those in the I/R group

(Fig. 3A). The results of the IHC

analysis indicated that the expression levels of Wnt1 in the renal

tissues were significantly decreased following renal I/R injury in

rats, whereas the expression levels of Wnt1 were significantly

increased following treatment with TMP compared with those in the

I/R group (Fig. 3B). Furthermore,

western blot analysis indicated that the protein expression levels

of β-catenin were significantly lower in the renal tissues of the

I/R group compared with those in the sham group; by contrast, the

protein expression levels of β-catenin were significantly increased

in the renal tissues following TMP treatment compared with those in

the I/R group (Fig. 3C). In

addition, IHC analysis indicated that the expression levels of

β-catenin were significantly reduced in the renal tissues following

I/R injury in rats; however, the protein expression levels of

β-catenin were significantly increased following TMP treatment

compared with those in the I/R group (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results

suggested that TMP activated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway.

| Figure 3TMP activates the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway in the kidney of rats following I/R. (A)

Representative western blots and semi-quantified protein levels

showing the expression levels of Wnt1 in the renal tissue of rats

in different groups. n=6. (B) Representative IHC images and protein

semi-quantification of Wnt1 in the renal tissue of rats in the

sham, I/R and I/R + TMP groups. n=3. (C) Representative western

blots and semi-quantified protein levels showing the expression

levels of β-catenin in the renal tissue of rats in different

groups. n=6. (D) Representative IHC images and protein

semi-quantification of β-catenin in the renal tissue of rats in the

sham, I/R and I/R + TMP groups. n=3. IHC images: Top row, scale

bars, 200 µm, magnification, x40; bottom row, scale bars, 20 µm,

magnification, x400. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

****P<0.0001. I/R, ischemia-reperfusion; TMP,

tetramethylpyrazine; IHC, immunohistochemistry. |

TMP ameliorates renal cell apoptosis

following I/R in rats

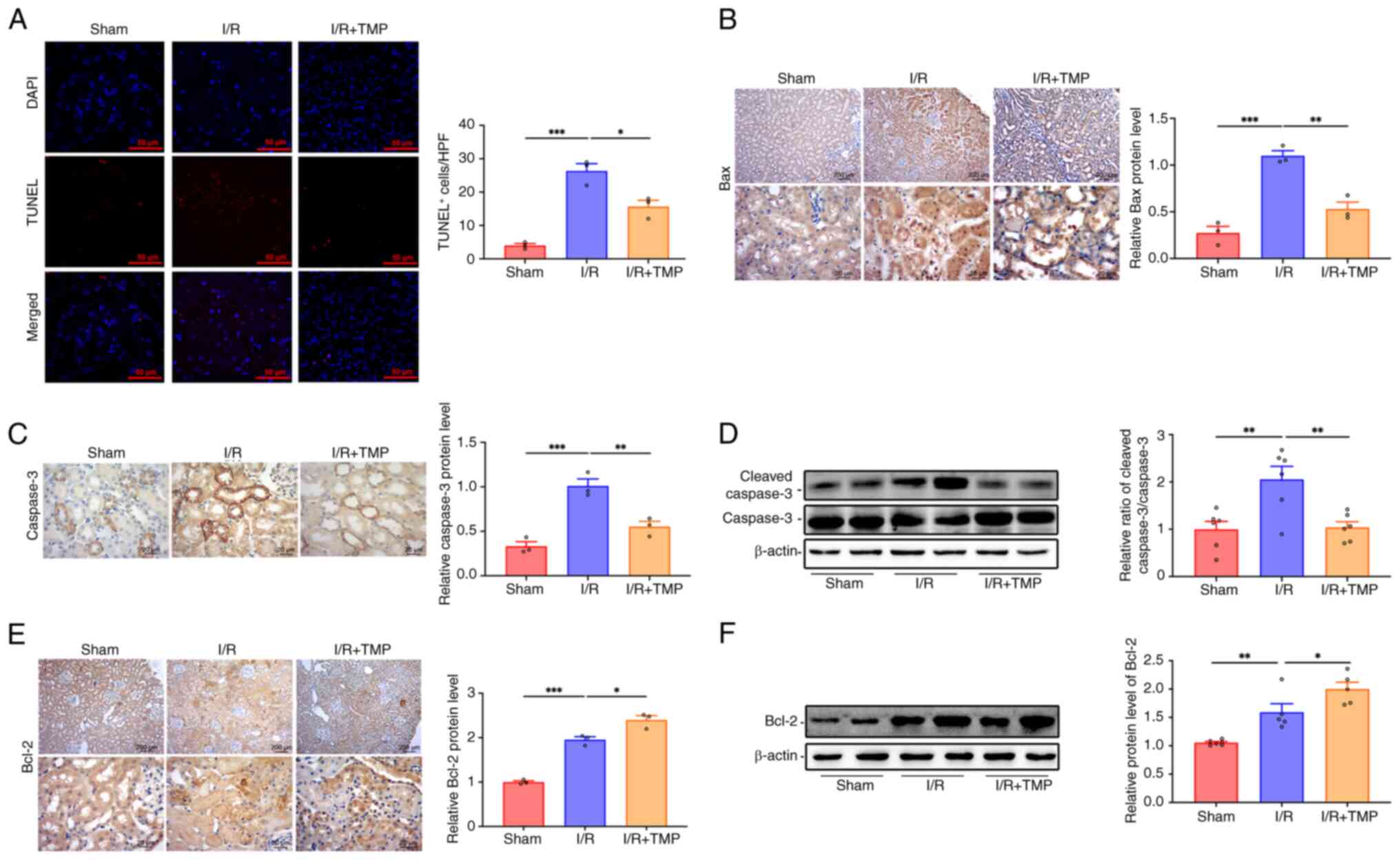

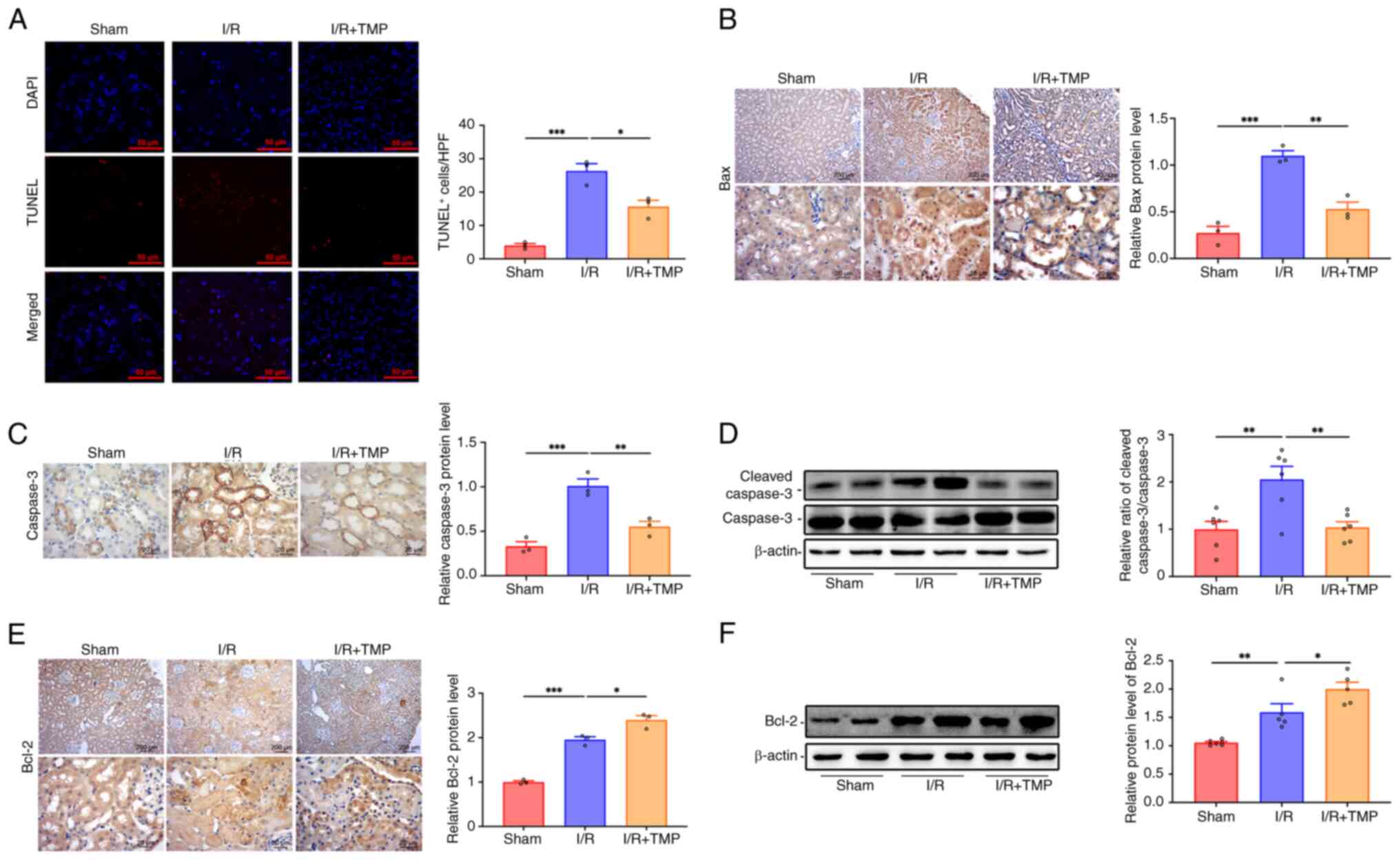

TUNEL staining indicated that, compared with that in

the sham group, the number of apoptotic renal tubular epithelial

cells in the I/R group was significantly increased, whereas the

number of apoptotic renal tubular epithelial cells was

significantly decreased following treatment with TMP compared with

that in the I/R group (Fig. 4A).

In addition, the apoptotic proteins caspase-3 and Bax, as well as

the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, were detected in the renal

tissues of rats (Fig. 4B-F). IHC

analysis indicated that rats in the I/R group expressed

significantly higher levels of the apoptotic protein Bax in renal

tissues as compared with rats in the sham group, whereas Bax

expression levels decreased significantly following treatment with

TMP compared with in the I/R group (Fig. 4B). IHC analysis also indicated that

rats in the I/R group expressed significantly higher levels of the

apoptotic protein caspase-3 in renal tissues as compared with rats

in the sham group, whereas caspase-3 expression levels decreased

significantly following treatment with TMP compared with in the I/R

group (Fig. 4C). Western blot

analysis indicated that the relative ratio of cleaved

caspase-3/caspase-3 in the renal tissues of the I/R group was

significantly higher than that in the sham group, which was

significantly decreased in the renal tissues following TMP

treatment compared with in the I/R group (Fig. 4D). IHC analysis indicated that

compared with those in the sham group, the expression levels of the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 were significantly increased in the

renal tissues of the I/R group (Fig.

4E). However, the expression levels of Bcl-2 were further

increased following treatment with TMP compared with in the I/R

group. Western blot analysis also indicated that the protein

expression levels of Bcl-2 in the renal tissues of the I/R group

were significantly higher than those in the sham group, and the

protein expression levels of Bcl-2 were further increased in the

renal tissues following TMP treatment compared with those in the

I/R group (Fig. 4F). These results

suggested that TMP could alleviate the apoptosis of renal tissue

following I/R by inhibiting the cleavage of caspase-3 and the

expression of Bax, and increasing the expression of the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2.

| Figure 4TMP ameliorates renal cell apoptosis

after I/R in rats. (A) TUNEL staining showing the renal cell

apoptosis levels in different groups. Scale bars, 50 µm. n=3.

Representative IHC images and protein semi-quantification of (B)

Bax and (C) caspase-3 in renal tissue of rats in different groups.

n=3. (D) Relative ratio of cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 determined

by western blotting. n=6. (E) Representative images and protein

semi-quantification of Bcl-2 in the renal tissue of rats in

different groups. n=3. (F) Representative western blots and

semi-quantified protein levels showing the expression levels of

Bcl-2 in the renal tissue of rats in different groups. n=6. IHC

images: Top row, scale bars, 200 µm, magnification, x40; bottom

row, scale bars, 20 µm, magnification, x400. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. I/R,

ischemia-reperfusion; TMP, tetramethylpyrazine; IHC,

immunohistochemistry. |

Discussion

The pathological mechanism of AKI is complex,

including inflammation, ischemia and nephrotoxic injury (33). To the best of our knowledge, the

present study was the first to discover the regulatory effect of

TMP on DKK1 and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in AKI renal

tissues, revealing that TMP attenuated AKI by activating the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling independent of DKK1. AKI is a group of

clinical syndromes in which renal function suddenly declines

sharply in a short period of time, and may result in chronic kidney

disease, end-stage renal disease or death (1). Notably, AKI is a common clinical

critical illness; it affects 10-15% of hospitalized patients, and

>50% of patients in the intensive care unit (34). The pathological changes of AKI are

mainly apparent in the renal tubular morphology, including loss of

renal tubular epithelial cell polarity, swelling, vacuolar

degeneration, necrosis, brush border shedding, cast formation in

the tubular lumen and inflammatory cell infiltration in the

interstitium. The main pathological mechanisms of AKI include

generation of free radicals, intracellular calcium overload

(35), inflammatory reactions and

apoptosis (36).

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a common

developmental signaling pathway that plays a crucial role in

embryonic development, morphogenesis and organogenesis, tissue

regeneration, and the pathogenesis of various diseases (17). A number of studies have indicated

that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in multiple

organ I/R injuries, such as cardiac, cerebral and renal I/R

injuries (37-40).

Studies have shown that in AKI transient activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is beneficial in reducing the

development of this disease, and promoting kidney repair and

regeneration, whereas sustained activation of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway promotes the progression of AKI to chronic kidney

disease (41). It is currently

considered that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway promotes renal

fibrosis in chronic kidney disease (18,42).

Inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway may maintain the

integrity of podocytes, reduce proteinuria and attenuate kidney

injury (43). Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway serves as a regulatory network that promotes or

inhibits apoptosis/autophagy under certain circumstances (44-46).

Therefore, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway could

attenuate AKI caused by I/R (47).

Recent studies have demonstrated that TMP can block the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and inhibit the proliferation and

infiltration of cancer cells (14,15).

The findings of the present study differ from those

of previous studies (19,48) and indicated that the expression

levels of Wnt1 and β-catenin were significantly decreased in rats

following I/R, while the expression levels of Wnt1 and β-catenin

were significantly increased following treatment with TMP. Western

blotting results showed that Wnt1 and β-catenin expression in the

I/R + TMP group exceeded the expression observed in the I/R group,

which was consistent with the results of IHC analysis. The IHC

analysis results showed increased protein expression in the I/R +

TMP group to a greater extent than that in the western blotting

results; however, there was no direct comparison between western

blotting and IHC analysis results. This may be due to the fact

that, compared with western blotting, IHC analysis may produce a

certain non-specific staining. In addition, following I/R, the

necrotic renal tissue had a higher background of non-specific

staining than non-necrotic tissue, which may have further

exacerbated the discrepancy between IHC analysis and western

blotting results. Therefore, there are limitations in relying on a

single experimental method to verify experimental conclusions.

Since IHC analysis has the advantages of observing morphology and

cell localization, both western blotting and IHC analysis were used

to verify the conclusions. Taken together, the results of the

present study suggested that TMP may promote the regeneration and

repair of renal cells by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway.

The DKK family includes the following four members:

DKK1, 2, 3 and 4. DKK1 is one of the classic inhibitors of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which functions by blocking the

binding of Wnt to LRP5/6 co-receptors to form dimers (49,50).

Studies have shown that DKK1 is involved in the occurrence and

development of chronic kidney disease (29,51);

however, whether it promotes the progression or alleviation of

chronic kidney disease has not been clearly determined and its

effects on AKI have not been reported. The histone demethylase

inhibitor GSK-J4 has been reported to reduce the expression levels

of DKK1, thereby attenuating renal dysfunction, glomerulosclerosis,

inflammation and fibrosis in diabetic mice (52). In addition, DKK1 has been shown to

aggravate cardiac I/R injury by weakening the effect of

pifithrin-α, which alleviates acute cerebral I/R injury via the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway (53). DKK1

exacerbates ischemic heart injury mainly by inducing LRP5/6

endocytosis and degradation (54).

Although insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 (IGFBP-4) and

DKK1 are inhibitors of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, IGFBP-4 inhibits

β-catenin to protect the ischemic heart, whereas DKK1 aggravates

ischemic heart injury mainly by inducing LRP5/6 endocytosis and

degradation (54). Furthermore,

DKK1 can decelerate vascular calcification by promoting the

degradation of phospholipase D1, thereby reducing the high

morbidity and mortality caused by vascular calcification in

atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease and diabetes (55). However, an accumulating number of

studies has shown that DKK1 can participate in cellular activities

independently of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. For example,

DKK1 could suppress JNK-mediated apoptosis and activate the

NF-κB-dependent cell survival mechanisms, independently of the

canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (56). In lupus nephritis, renal Wnt

signaling activity is increased, accompanied by an increase in

renal and serum levels of DKK1(27). In the present study, it was shown

that TMP treatment increased the expression of DKK1, which is

inconsistent with the proposed function of DKK1 as an inhibitor of

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Therefore, it was considered that

the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by TMP was

independent of DKK1.

Since the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway by TMP was independent of DKK1, the signaling pathways or

specific molecular interactions of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway activated by TMP need to be explored. Known regulators of

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway include: R-spondins, Norrin, TSPAN12,

secreted frizzled-related protein, Wnt inhibitory factor, glycogen

synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), axis inhibition protein 1, adenomatous

polyposis coli protein (APC), disheveled 1, sclerostin, ring finger

protein 43, zinc and ring finger 3, Cerberus, Klotho, IGFBP, Shisa,

APC down-regulated 1 and Tiki1 (57-65).

Among them, it has been reported that an analog of TMP could

inhibit the phosphorylation of GSK3β and participate in the

regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (57). Therefore, our future studies will

focus on testing whether TMP can regulate the activation of

Wnt/β-catenin pathway by regulating GSK3β phosphorylation.

Previous studies have shown that TMP has

cardiovascular protection, anti-platelet, anti-ischemic,

anti-Alzheimer's disease, neuroprotective and anticancer effects

(66). TMP has been used in the

treatment of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, nervous, digestive

system and kidney diseases, as well as in cancer (6). For example, a previous study has

shown that TMP protects against congestive heart failure induced by

myocardial infarction by downregulating the TGF-β1/Smad signaling

pathway, suppressing the activation of the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, inhibiting the synthesis of

pro-inflammatory factors and reducing oxidative stress (67). It has also been suggested that TMP

reduces cell apoptosis and inflammation caused by cerebral I/R

injury by targeting the circ_0008146/microRNA-709/Cx3cr1 axis

(68). Other studies have

suggested that TMP may alleviate diabetic nephropathy in rats

(69,70). Avila-Carrasco et al

(71) reported that TMP can

increase the expression of natural inhibitors of TGF-β, hepatocyte

growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein-7 and other natural

inhibitors, and reduce the risk of renal interstitial fibrosis.

TMP exhibits anti-apoptosis effects. Liu et

al (72) indicated that TMP

may ameliorate the apoptosis of H9C2 cardiomyoblasts by negatively

regulating hypoxia inducible factor-1α-induced Bcl-2 interacting

protein 3 expression, thereby reversing the hypoxic effects induced

by hyperglycemia. A previous study has shown that TMP can alleviate

cognitive impairment by suppressing oxidative stress,

neuroinflammation and apoptosis in type 2 diabetic rats (73). Another study has also shown that

TMP alleviates neural apoptosis in the injured spinal cord via the

downregulation of miR-214-3p (74). However, there have been limited

studies assessing the effect of TMP on apoptosis in AKI. Our

previous research showed the anti-apoptosis effect of TMP in AKI

(12,13); however, at the time there were less

data available on the effect of TMP on apoptosis-related molecules.

In the present study, multiple experiments, including detection of

the number of apoptotic cells by TUNEL staining, assessment of the

expression levels of cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 by western

blotting, and analysis of the expression levels of

apoptosis-related molecules Bcl-2 and Bax by western blotting and

IHC staining, were performed to prove that TMP could reduce renal

cell apoptosis in AKI. The present study demonstrated that the

renal cell apoptosis in rats following I/R was significantly

reduced after TMP treatment, which was in accordance with the

results of the other study conducted by our group (13). Combined with the results that both

DKK1 upregulation and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation by

TMP could alleviate AKI renal injury, the protective effect was

most likely through the regulation of apoptosis.

The clinical value of TMP in AKI is supported by the

high incidence of AKI, its poor prognosis and the absence of

approved specific medical therapies other than general supportive

care (75). Several preclinical

studies have shown that TMP has therapeutic potential for AKI

(76,77). If possible, clinical trials

combining TMP with the current standard of care could be conducted

to further confirm the efficacy of TMP in human AKI.

The limitations of the present study include the

lack of in vitro cell experiments for mechanistic

investigation and the absence of direct molecular targets involving

TMP. To verify whether DKK1 and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway were

involved in the protective effect of TMP, the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway and DKK1 expression need to be verified in in

vitro experiments. The relevant mechanistic studies that should

be conducted in future include animal experiments and cell

experiments using Wnt inhibitors, such as small interfering

(si)RNA-Wnt and/or siRNA-DKK1. Molecular docking between TMP and

regulators or key molecules of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway should

also be conducted to preliminarily screen possible direct targets

of TMP and for experimental validation. The mechanism in which DKK1

and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway affects apoptosis should also be a

point of focus. Furthermore, the sample size was not determined

through power analysis; it was determined based on the resource

equation method (32). The present

animal experiment was an exploratory study. When designing

experiments, more consideration should be given to other elements

that can be tested rather than sample size estimation to ensure the

quality of scientific research (78).

Currently, the only effective treatment strategy for

AKI is renal replacement therapy. Therefore, it is imperative to

develop more effective treatment strategies. The research results

of the in vivo rat model of AKI treated with TMP

demonstrated in the present study suggested that TMP targets DKK1

and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, and therefore could

effectively treat AKI.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the Shandong Natural

Science Fund of Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2020MH080); the

Projects of Medical and Health Technology Development Program in

Shandong Province (grant nos. 202003050666 and 2019WS310); the

Projects of Technological Innovation Development Program in Yantai

City (grant no. 2022YD071); the Traditional Chinese Medicine

Science and Technology Project of Shandong Province (grant no.

M-2023017); and the Clinical +X project of Binzhou Medical

University (grant no. BY2021LCX24).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XW, XC and DY were involved in conceptualization,

conducted the experiments, and were involved in visualization and

writing of the original draft. LZ, ZG, XS and AL helped to conduct

the experiments, data analysis and draft writing. YN and PD were

involved in conceptualization, funding acquisition, project

administration, supervision, review and editing. XW and PD confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal

Care and Use Committee of Binzhou Medical University (approval no.

2020-07; Yantai, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Levey AS and James MT: Acute kidney

injury. Ann Intern Med. 167:ITC66–ITC80. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Niculae A, Gherghina ME, Peride I, Tiglis

M, Nechita AM and Checherita IA: Pathway from acute kidney injury

to chronic kidney disease: Molecules involved in renal fibrosis.

Int J Mol Sci. 24(14019)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Deng Y, Zeng L, Liu H, Zuo A, Zhou J, Yang

Y, You Y, Zhou X, Peng B, Lu H, et al: Silibinin attenuates

ferroptosis in acute kidney injury by targeting FTH1. Redox Biol.

77(103360)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gonçalves GM, Castoldi A, Braga TT and

Câmara NO: New roles for innate immune response in acute and

chronic kidney injuries. Scand J Immunol. 73:428–435.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhou M, Tang W, Fu Y, Xu X, Wang Z, Lu Y,

Liu F, Yang X, Wei X, Zhang Y, et al: Progranulin protects against

renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney Int. 87:918–929.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lin J, Wang Q, Zhou S, Xu S and Yao K:

Tetramethylpyrazine: A review on its mechanisms and functions.

Biomed Pharmacother. 150(113005)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chen HY, Xu DP, Tan GL, Cai W, Zhang GX,

Cui W, Wang JZ, Long C, Sun YW, Yu P, et al: A Potent

multi-functional neuroprotective derivative of tetramethylpyrazine.

J Mol Neurosci. 56:977–987. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Bai XY, Wang XF, Zhang LS, Du PC, Cao Z

and Hou Y: Tetramethylpyrazine ameliorates experimental autoimmune

encephalomyelitis by modulating the inflammatory response. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 503:1968–1972. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang B, Ni Q, Wang X and Lin L:

Meta-analysis of the clinical effect of ligustrazine on diabetic

nephropathy. Am J Chin Med. 40:25–37. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shao H, Zhao L, Chen F, Zeng S, Liu S and

Li J: Efficacy of ligustrazine injection as adjunctive therapy for

angina pectoris: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Sci

Monit. 21:3704–3715. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ni X, Ni X, Liu S and Guo X: Medium- and

long-term efficacy of ligustrazine plus conventional medication on

ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Tradit

Chin Med. 33:715–720. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jiang G, Xin R, Yuan W, Zhang L, Meng X,

Sun W, Han H, Hou Y, Wang L and Du P: Ligustrazine ameliorates

acute kidney injury through downregulation of NOD2-mediated

inflammation. Int J Mol Med. 45:731–742. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sun W, Li A, Wang Z, Sun X, Dong M, Qi F,

Wang L, Zhang Y and Du P: Tetramethylpyrazine alleviates acute

kidney injury by inhibiting NLRP3/HIF-1α and apoptosis. Mol Med

Rep. 22:2655–2664. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wang M, Zhang L, Huang X and Sun Q:

Ligustrazine promotes hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated trophoblast

cell proliferation and migration by regulating the

microRNA-27a-3p/ATF3 axis. Arch Biochem Biophys.

737(109522)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Jung YY, Mohan CD, Eng H, Narula AS,

Namjoshi OA, Blough BE, Rangappa KS, Sethi G, Kumar AP and Ahn KS:

2,3,5,6-Tetramethylpyrazine targets epithelial-mesenchymal

transition by abrogating manganese superoxide dismutase expression

and TGFβ-driven signaling cascades in colon cancer cells.

Biomolecules. 12(891)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Steinhart Z and Angers S: Wnt signaling in

development and tissue homeostasis. Development.

145(dev146589)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang

X, Zhou Z, Shu G and Yin G: Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function,

biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7(3)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Schunk SJ, Floege J, Fliser D and Speer T:

WNT-β-catenin signalling-a versatile player in kidney injury and

repair. Nat Rev Nephrol. 17:172–184. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Huffstater T, Merryman WD and Gewin LS:

Wnt/β-catenin in acute kidney injury and progression to chronic

kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 40:126–137. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kawakami T, Ren S and Duffield JS: Wnt

signalling in kidney diseases: Dual roles in renal injury and

repair. J Pathol. 229:221–231. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Tan RJ, Zhou D, Zhou L and Liu Y:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling and kidney fibrosis. Kidney Int Suppl

(2011). 4:84–90. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Aggarwal S, Wang Z, Rincon Fernandez

Pacheco D, Rinaldi A, Rajewski A, Callemeyn J, Van Loon E,

Lamarthée B, Covarrubias AE, Hou J, et al: SOX9 switch links

regeneration to fibrosis at the single-cell level in mammalian

kidneys. Science. 383(eadd6371)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ming WH, Luan ZL, Yao Y, Liu HC, Hu SY, Du

CX, Zhang C, Zhao YH, Huang YZ, Sun XW, et al: Pregnane X receptor

activation alleviates renal fibrosis in mice via interacting with

p53 and inhibiting the Wnt7a/β-catenin signaling. Acta Pharmacol

Sin. 44:2075–2090. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Niehrs C: Function and biological roles of

the dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene. 25:7469–7481.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ng LF, Kaur P, Bunnag N, Suresh J, Sung

ICH, Tan QH, Gruber J and Tolwinski NS: WNT signaling in disease.

Cells. 8(826)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lin CL, Wang JY, Ko JY, Huang YT, Kuo YH

and Wang FS: Dickkopf-1 promotes hyperglycemia-induced accumulation

of mesangial matrix and renal dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol.

21:124–135. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tveita AA and Rekvig OP: Alterations in

Wnt pathway activity in mouse serum and kidneys during lupus

development. Arthritis Rheum. 63:513–522. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Klavdianou K, Liossis SN and Daoussis D:

Dkk1: A key molecule in joint remodelling and fibrosis. Mediterr J

Rheumatol. 28:174–182. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Hsu YC, Chang CC, Hsieh CC, Huang YT, Shih

YH, Chang HC, Chang PJ and Lin CL: Dickkopf-1 acts as a profibrotic

mediator in progressive chronic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci.

24(7679)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

National Research Council (US) Committee

for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th

edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2011.

|

|

31

|

Office of the Institutional Animal Care

and Use Committee, The University of Iowa: Anesthesia (Guideline).

https://animal.research.uiowa.edu/iacuc-guidelines-anesthesia.

Accessed August 21, 2025.

|

|

32

|

Charan J and Kantharia ND: How to

calculate sample size in animal studies? J Pharmacol Pharmacother.

4:303–306. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Pickkers P, Darmon M, Hoste E, Joannidis

M, Legrand M, Ostermann M, Prowle JR, Schneider A and Schetz M:

Acute kidney injury in the critically ill: An updated review on

pathophysiology and management. Intensive Care Med. 47:835–850.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ostermann M, Lumlertgul N, Jeong R, See E,

Joannidis M and James M: Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 405:241–256.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Mehrotra P, Sturek M, Neyra JA and Basile

DP: Calcium channel Orai1 promotes lymphocyte IL-17 expression and

progressive kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 129:4951–4961.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kar F, Hacioglu C, Senturk H, Donmez DB

and Kanbak G: The role of oxidative stress, renal inflammation, and

apoptosis in post ischemic reperfusion injury of kidney tissue: The

protective effect of dose-dependent boric acid administration. Biol

Trace Elem Res. 195:150–158. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Chi F, Feng L, Li Y, Zhao S, Yuan W, Jiang

Y and Cheng L: MiR-30b-5p promotes myocardial cell apoptosis in

rats with myocardial infarction through regulating Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway. Minerva Med. 114:476–484. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sun JD, Li XM, Liu JL, Li J and Zhou H:

Effects of miR-150-5p on cerebral infarction rats by regulating the

Wnt signaling pathway via p53. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

24:3882–3891. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chen X, Tan H, Xu J, Tian Y, Yuan Q, Zuo

Y, Chen Q, Hong X, Fu H, Hou FF, et al: Klotho-derived peptide 6

ameliorates diabetic kidney disease by targeting Wnt/β-catenin

signaling. Kidney Int. 102:506–520. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Al-Salam S, Jagadeesh GS, Sudhadevi M and

Yasin J: Galectin-3 and autophagy in renal acute tubular necrosis.

Int J Mol Sci. 25(3604)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Meng P, Zhu M, Ling X and Zhou L: Wnt

signaling in kidney: The initiator or terminator? J Mol Med (Berl).

98:1511–1523. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Li SS, Sun Q, Hua MR, Suo P, Chen JR, Yu

XY and Zhao YY: Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway as a

potential therapeutic strategy in renal tubulointerstitial

fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 12(719880)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhou L and Liu Y: Wnt/β-catenin signalling

and podocyte dysfunction in proteinuric kidney disease. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 11:535–545. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Tao H, Chen F, Liu H, Hu Y, Wang Y and Li

H: Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation reverses gemcitabine

resistance by attenuating Beclin1-mediated autophagy in the MG63

human osteosarcoma cell line. Mol Med Rep. 16:1701–1706.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Menon NA, Kumar CD, Ramachandran P, Blaize

B, Gautam M, Cordani M and Kumar LD: Small-molecule inhibitors of

WNT signalling in cancer therapy and their links to autophagy and

apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 986(177137)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Ma Q, Yu J, Zhang X, Wu X and Deng G:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway-a versatile player in apoptosis and

autophagy. Biochimie. 211:57–67. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Chen X, Wang CC, Song SM, Wei SY, Li JS,

Zhao SL and Li B: The administration of erythropoietin attenuates

kidney injury induced by ischemia/reperfusion with increased

activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J Formos Med Assoc.

114:430–437. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Xiao L, Zhou D, Tan RJ, Fu H, Zhou L, Hou

FF and Liu Y: Sustained activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling

drives AKI to CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 27:1727–1740.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Baetta R and Banfi C: Dkk (dickkopf)

proteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 39:1330–1342.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Liang L, He H, Lv R, Zhang M, Huang H, An

Z and Li S: Preliminary mechanism on the methylation modification

of Dkk-1 and Dkk-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol.

36:1245–1250. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Li YH, Cheng YC, Wu J and Lee IT: Plasma

dickkopf-1 levels are associated with chronic kidney disease.

Metabolites. 15(300)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Hung PH, Hsu YC, Chen TH, Ho C and Lin CL:

The histone demethylase inhibitor GSK-J4 Is a therapeutic target

for the kidney fibrosis of diabetic kidney disease via DKK1

modulation. Int J Mol Sci. 23(9407)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang H, Du D, Gao X, Tian X, Xu Y, Wang

B, Yang S, Liu P and Li Z: PFT-α protects the blood-brain barrier

through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway after acute ischemic stroke.

Funct Integr Genomics. 23(314)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Wo D, Peng J, Ren DN, Qiu L, Chen J, Zhu

Y, Yan Y, Yan H, Wu J, Ma E, et al: Opposing roles of Wnt

inhibitors IGFBP-4 and Dkk1 in cardiac ischemia by differential

targeting of LRP5/6 and β-catenin. Circulation. 134:1991–2007.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Li X, Liu XL, Li X, Zhao YC, Wang QQ,

Zhong HY, Liu DD, Yuan C, Zheng TF and Zhang M: Dickkopf1 (Dkk1)

alleviates vascular calcification by regulating the degradation of

phospholipase D1 (PLD1). J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 15:1327–1339.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Yuan S, Hoggard NK, Kantake N, Hildreth BE

III and Rosol TJ: Effects of dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) on prostate cancer

growth and bone metastasis. Cells. 12(2695)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Zou Y, Zhao D, Yan C, Ji Y, Liu J, Xu J,

Lai Y, Tian J, Zhang Y and Huang Z: Novel ligustrazine-based

analogs of piperlongumine potently suppress proliferation and

metastasis of colorectal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Med

Chem. 61:1821–1832. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Albrecht LV, Tejeda-Muñoz N and De

Robertis EM: Cell biology of canonical Wnt signaling. Annu Rev Cell

Dev Biol. 37:369–389. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Gao C and Chen YG: Dishevelled: The hub of

Wnt signaling. Cell Signal. 22:717–727. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Cruciat CM and Niehrs C: Secreted and

transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 5(a015081)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Farnhammer F, Colozza G and Kim J: RNF43

and ZNRF3 in Wnt signaling-A master regulator at the membrane. Int

J Stem Cells. 16:376–384. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Gao Y, Chen N, Fu Z and Zhang Q: Progress

of Wnt signaling pathway in osteoporosis. Biomolecules.

13(483)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Fetisov TI, Lesovaya EA, Yakubovskaya MG,

Kirsanov KI and Belitsky GA: Alterations in WNT signaling in

leukemias. Biochemistry (Mosc). 83:1448–1458. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Ho HYH: The tale of capturing Norrin.

Elife. 13(e98933)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Raslan AA and Yoon JK: R-spondins:

Multi-mode WNT signaling regulators in adult stem cells. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 106:26–34. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Zou J, Gao P, Hao X, Xu H, Zhan P and Liu

X: Recent progress in the structural modification and

pharmacological activities of ligustrazine derivatives. Eur J Med

Chem. 147:150–162. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Chen Q, Zhang D, Bi Y, Zhang W, Zhang Y,

Meng Q, Li Y and Bian H: The protective effects of liguzinediol on

congestive heart failure induced by myocardial infarction and its

relative mechanism. Chin Med. 15(63)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Li L, Zhang D, Yao W, Wu Z, Cheng J, Ji Y,

Dong L, Zhao C and Wang H: Ligustrazine exerts neuroprotective

effects via circ_0008146/miR-709/Cx3cr1 axis to inhibit cell

apoptosis and inflammation after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion

injury. Brain Res Bull. 190:244–255. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Rai U, Kosuru R, Prakash S, Tiwari V and

Singh S: Tetramethylpyrazine alleviates diabetic nephropathy

through the activation of Akt signalling pathway in rats. Eur J

Pharmacol. 865(172763)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Yang QH, Liang Y, Xu Q, Zhang Y, Xiao L

and Si LY: Protective effect of tetramethylpyrazine isolated from

Ligusticum chuanxiong on nephropathy in rats with

streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Phytomedicine. 18:1148–1152.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Avila-Carrasco L, Majano P, Sánchez-Toméro

JA, Selgas R, López-Cabrera M, Aguilera A and González Mateo G:

Natural plants compounds as modulators of epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition. Front Pharmacol. 10(715)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Liu SP, Shibu MA, Tsai FJ, Hsu YM, Tsai

CH, Chung JG, Yang JS, Tang CH, Wang S, Li Q and Huang CY:

Tetramethylpyrazine reverses high-glucose induced hypoxic effects

by negatively regulating HIF-1α induced BNIP3 expression to

ameliorate H9c2 cardiomyoblast apoptosis. Nutr Metab (Lond).

17(12)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Dhaliwal J, Dhaliwal N, Akhtar A, Kuhad A

and Chopra K: Tetramethylpyrazine attenuates cognitive impairment

via suppressing oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis

in type 2 diabetic rats. Neurochem Res. 47:2431–2444.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Fan Y and Wu Y: Tetramethylpyrazine

alleviates neural apoptosis in injured spinal cord via the

downregulation of miR-214-3p. Biomed Pharmacother. 94:827–833.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Matuszkiewicz-Rowińska J and Małyszko J:

Acute kidney injury, its definition, and treatment in adults:

Guidelines and reality. Pol Arch Intern Med. 130:1074–1080.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Li J and Gong X: Tetramethylpyrazine: An

active ingredient of Chinese herbal medicine with therapeutic

potential in acute kidney injury and renal fibrosis. Front

Pharmacol. 13(820071)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Li J, Li T, Li Z, Song Z and Gong X:

Potential therapeutic effects of Chinese meteria medica in

mitigating drug-induced acute kidney injury. Front Pharmacol.

14(1153297)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Ko MJ and Lim CY: General considerations

for sample size estimation in animal study. Korean J Anesthesiol.

74:23–29. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|