Introduction

With the relaxation of birth policies in China it is

possible to have a second or even a third child, and combined with

the high rates of cesarean section surgeries, the proportion of

scar pregnancies in China has significantly increased compared with

rates before this policy change (1-3).

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) refers to a rare ectopic pregnancy,

where a previous pregnancy is delivered by cesarean section but

then an embryo implants in the scar site of the previous cesarean

section (4). Owing to the thin

muscle layer and poor elasticity of the scar tissue at the site of

cesarean section, various serious complications, such as uterine

perforation, blood loss and endangerment of life for the mother,

can occur as gestational age increases (5). With the widespread application of

transvaginal ultrasound examination and increasing awareness of

CSP, its diagnosis and treatment with surgery and medication have

greatly improved (6). However, in

real-world clinical settings, pregnant and postpartum women remain

frequently misdiagnosed with scarred uterine pregnancies that are

mistakenly regarded as intrauterine pregnancy or cervical

pregnancy, especially in underdeveloped areas of less developed

countries, where the misdiagnosis rate may be even higher (7). If patients are initially

misdiagnosed, they incur a particular risk of mistreatment,

hysterectomy, or even fatality due to bleeding or uterine rupture.

This risk is typically associated with both the diagnostic and

treatment capabilities of obstetricians and gynecologists, in

addition to the cognitive level of ultrasound clinicians.

Therefore, this requires the attention of clinicians and monitoring

physicians. In the present study, the clinical data of patients

with CSP who experienced misdiagnosis and mistreatment during the

initial diagnosis were retrospectively analyzed, whilst also

exploring the contributing factors and potential treatment

strategies.

Patients and methods

A retrospective review of medical record data from

January 2018 to October 2024 identified 42 cases of CSP at the

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 940th Hospital of the

Joint Logistics Support Force of the Chinese People's Liberation

Army (Gansu, China).

The inclusion criteria for CSP diagnosis and

treatment (8,9) were based on a comprehensive

evaluation of clinical, imaging and laboratory examinations: i)

Clinical history, with a previous history of one or more cesarean

section (transverse incision in the lower segment of the uterus),

amenorrhea (for 5-12 weeks), presence or absence of early pregnancy

symptoms (such as vaginal bleeding and lower abdominal pain) and

the absence of serious complications (such as infection or

coagulation dysfunction); ii) transvaginal/abdominal ultrasound

features meeting at least two of the stated criteria [the absence

of gestational sac in the uterine cavity and cervical canal;

presence of the gestational sac at the scar site of the cesarean

section in the lower anterior wall of the uterus; thinning

(thickness ≤3 mm) or disruption of the muscle layer at the scar

site; and absence of uterine muscle layer between the gestational

sac and bladder is missing or presence of abundant blood flow (if

Doppler shows low impedance blood-flow signals)]; and iii)

laboratory examination showing positive blood β-human chorionic

gonadotropin, with further ultrasound imaging needed to determine

whether pregnancy had occurred.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Cervical

pregnancy, where the gestational sac is located inside the cervical

canal, the cervix is enlarged and the uterine cavity is empty; ii)

intrauterine pregnancy miscarriage, where the gestational sac

detached into the cervical canal; and iii) evidence of other

ectopic pregnancy, including tubal and cornual pregnancy.

All relevant patient data were collected from the

electronic medical record system of the 940th Hospital of the Joint

Logistics Support Force of the Chinese People's Liberation Army.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the 940th

Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of the Chinese

People's Liberation Army (approval no. 2024KYLL002). Written

informed consent for participation and publication was obtained

from all patients included in the present study.

Results

Of the 42 cases of CSP, 7 were identified as

misdiagnosis and mistreatment, with a misdiagnosis and mistreatment

rate of 16.67%. For the seven cases included in the present study,

the age range was 28-35 years, with a mean age of 31.86±2.67 years.

Hematological examination of the patients upon admission showed no

abnormalities (Table I). The

patients had amenorrhea for 40-94 days, whereas all had a history

of 1-2 cesarean sections. The interval between cesarean section

surgery and the current pregnancy ranged between 11-120 months. In

total, three patients had a history of 1-2 induced abortions after

cesarean section (cases 1, 5 and 7). All patients were diagnosed

with intrauterine pregnancy by ultrasound. A total of three

patients (cases 1, 4 and 6) had a small amount (<50 ml) of

irregular vaginal bleeding after 50 days of amenorrhea and were

diagnosed with threatened miscarriage (Table II).

| Table IInitial hematological examination

indicators for the patients misdiagnosed with cesarean scar

pregnancy. |

Table I

Initial hematological examination

indicators for the patients misdiagnosed with cesarean scar

pregnancy.

| Case | Medical file

number | White blood cell

count (x109/l) | Red blood cell count

(x1012/l) | Hemoglobin (g/l) | Platelet

(x109/l) | Activated partial

thromboplastin time (sec) | Prothrombin time

(sec) | Human chorionic

gonadotropin (IU/l) |

|---|

| Ref. range | - | 3.5-9.5 | 3.68-5.13 | 113-151 | 101-320 | 23-32 | 9-14 | 0-10 |

|---|

| 1 | ZX0388383 | 12.12 | 4.43 | 133 | 278 | 26.8 | 11.2 | 106.7 |

| 2 | 15069188 | 7.59 | 4.47 | 144 | 215 | 26.3 | 11.9 | 321.1 |

| 3 | 15097476 | 8.29 | 4.54 | 136 | 206 | 28.1 | 11.8 | 6,371.9 |

| 4 | 79042441 | 8.63 | 3.38 | 99 | 219 | 22.1 | 9.6 | 1,352.7 |

| 5 | ZX0493131 | 8.5 | 4.46 | 137 | 232 | 21.7 | 11.1 | 2,414.3 |

| 6 | ZX0360820 | 5.65 | 3.63 | 108 | 188 | 25.6 | 11 | 91.2 |

| 7 | ZX0400103 | 4.59 | 3.91 | 125 | 172 | 23.5 | 11.1 | 3,5470.3 |

| Table IIBasic characteristics and treatment

status of the seven patients misdiagnosed with cesarean scar

pregnancies. |

Table II

Basic characteristics and treatment

status of the seven patients misdiagnosed with cesarean scar

pregnancies.

| Case | Case no. | Age (years) | Days of

amenorrhea | Time since last

cesarean section (months) | Misdiagnosis | Pre-treatment | Bleeding volume

(ml) | Surgery |

|---|

| 1 | ZX0388383 | 33 | 71 | 36 | Embryo arrest | Medical

abortion | 1,200 | Interventional

embolization + laparoscopic scar resection and uterine repair |

| 2 | 15069188 | 30 | 51 | 14 | Threatened

miscarriages | Ultrasound guided

curettage surgery | 300 | Interventional

surgery embolization + curettage |

| 3 | 15097476 | 30 | 40 | 11 | Threatened

miscarriages | Medical

abortion | 150 | Palace cleaning

surgery + conservative treatment with medication |

| 4 | 79042441 | 32 | 85 | 60 | Threatened

miscarriages | Ultrasound guided

curettage surgery | 600 | Interventional

embolization + curettage surgery |

| 5 | ZX0493131 | 35 | 45 | 120 | Embryo arrest | Medical

abortion | 200 | Interventional

embolization + curettage surgery |

| 6 | ZX0360820 | 28 | 94 | 36 | Embryo arrest | Medical

abortion | 1,400 | Interventional

embolization + laparoscopic scar resection and uterine repair |

| 7 | ZX0400103 | 35 | 45 | 36 | Embryo arrest | Medical

abortion | 100 | Palace cleaning

surgery + conservative treatment with medication |

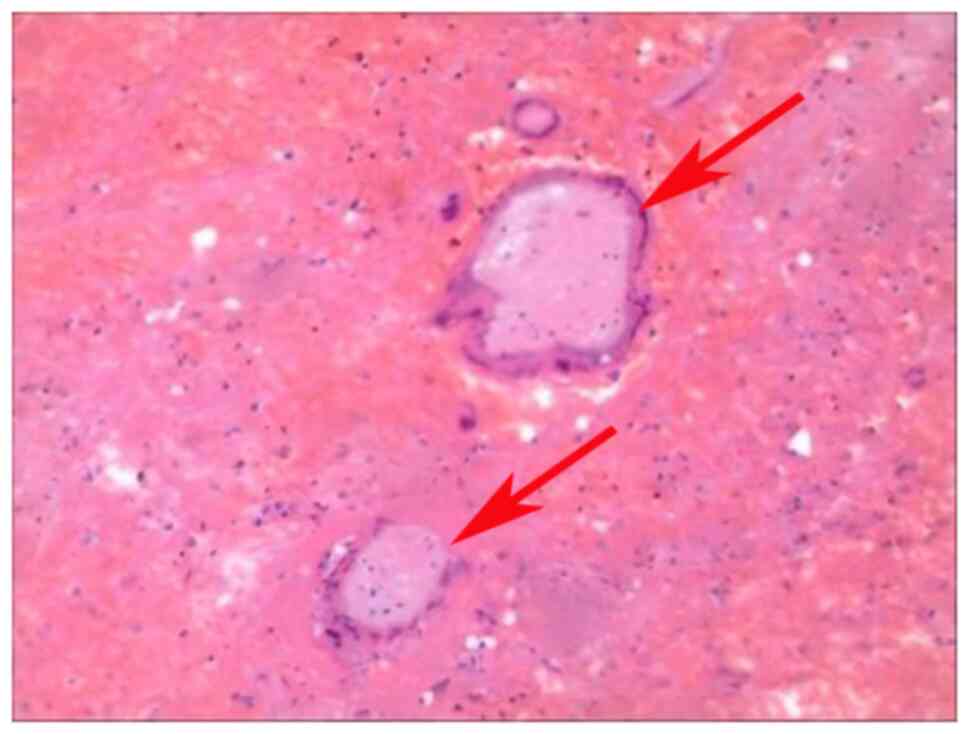

Of the three cases (cases 2, 3 and 4) misdiagnosed

with threatened miscarriage, two cases underwent abortion under

anesthesia for a curettage procedure (cases 2 and 4) and one case

required a medical drug-induced abortion (case 3). In total, 3 days

after surgery, these three patients' ultrasound examinations

revealed an incomplete abortion, resulting in uterine curettage

being performed under ultrasound guidance in these three patients.

During surgery, clear endometrial lines were observed and abnormal

echoes were located at the scar site of the original cesarean

section in the lower segment of the uterus (Fig. 1). CSP was therefore considered for

the diagnosis. Two patients had minimal bleeding (<50 ml) and

were administered a single intramuscular injection of methotrexate

(50 mg/m2) and an oral administration of 50 mg

mifepristone once every 12 h for three doses (cases 2 and 3). In

one case (case 4) the intraoperative bleeding volume reached 800

ml. After emergency bilateral uterine artery embolization, uterine

bleeding ceased. For case 3 requiring a medical abortion, a mass

with a diameter of ~4 cm was observed on the right side of the

lower segment of the uterus, where the intraoperative bleeding

volume reached 600 ml. A total of 2 days after blood transfusion,

fluid replacement and anti-shock treatment, laparoscopic uterine

CSP resection and uterine repair surgery were performed, where

postoperative pathological specimens showed villous tissue and

trophoblast cells in case 3 (Fig.

2).

In total, four of the seven patients were

misdiagnosed as having embryonic arrest and underwent medical

abortions that included intramuscular injection of methotrexate (50

mg/m2) and an oral administration of 50 mg mifepristone

once every 12 h for three doses (cases 1, 5, 6 and 7). In these

four cases, after methotrexate and mifepristone administration,

vaginal bleeding occurred and the ‘pregnancy product’ was

discharged, which were visually confirmed by the gynecologist. The

uterus contracted well, but a moderate quantity (100-300 ml) of

blood flowed out of the uterine cavity. Bleeding gradually stopped

after local compression and intramuscular injection of oxytocin (10

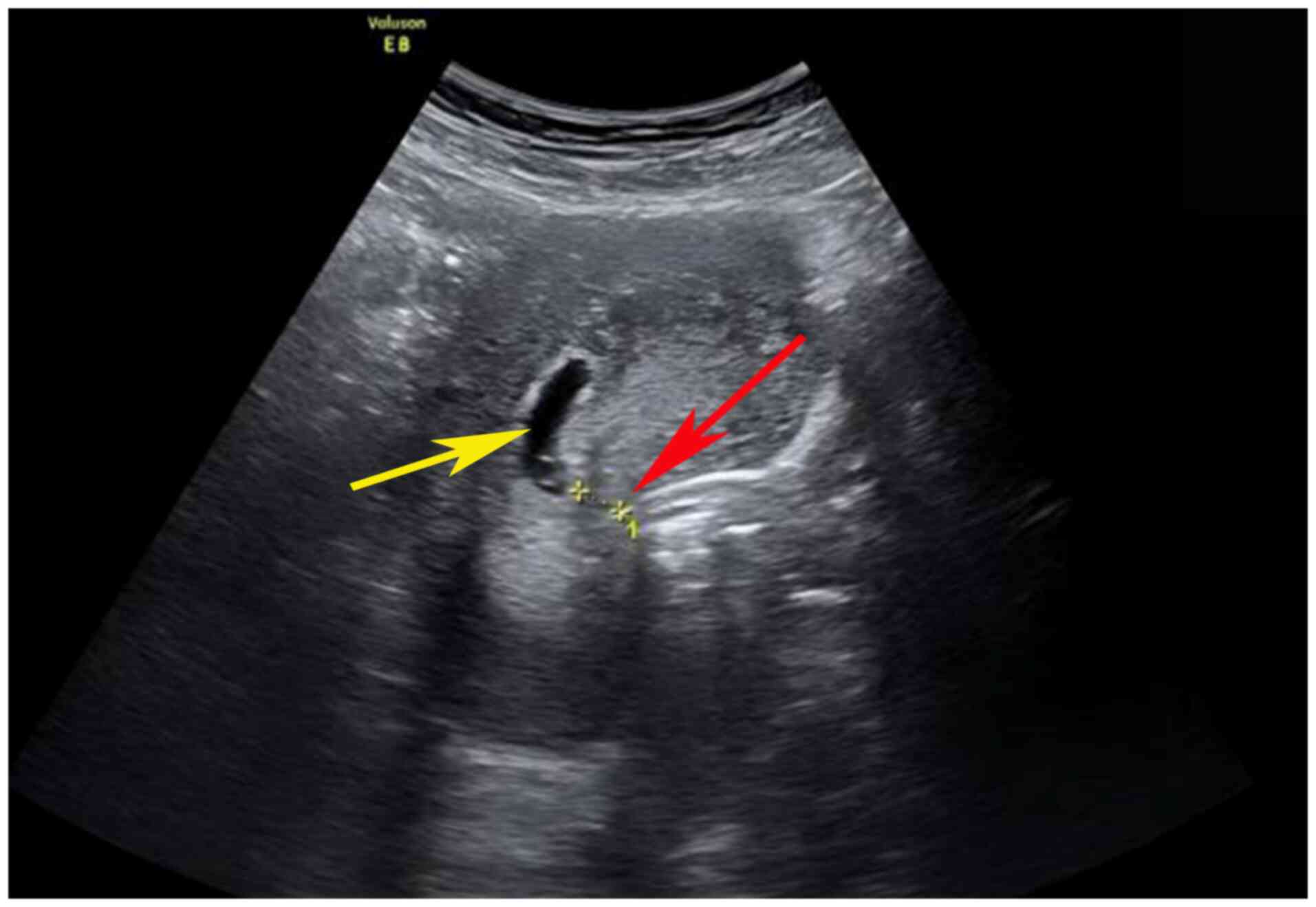

U) in all four cases. A total of 10 days after surgery, one patient

(case 6) returned to the hospital for a follow-up ultrasound

examination, where abnormal echoes in the uterine cavity were

noted. Therefore, curettage was performed under ultrasound guidance

(Fig. 3). During the procedure,

clear endometrial lines were observed and a small blood clot (15

ml) and decidual tissue were cleared. However, there was a

considerable amount of uterine bleeding, with a cumulative blood

loss of 1,400 ml during the operation. A mixed mass protruding

outward from the lower part of the anterior wall of the uterus was

noted, where the lower uterine muscle layer was thin. Therefore,

CSP was considered. Immediate uterine artery intervention

embolization was performed and bleeding ceased. Blood transfusions

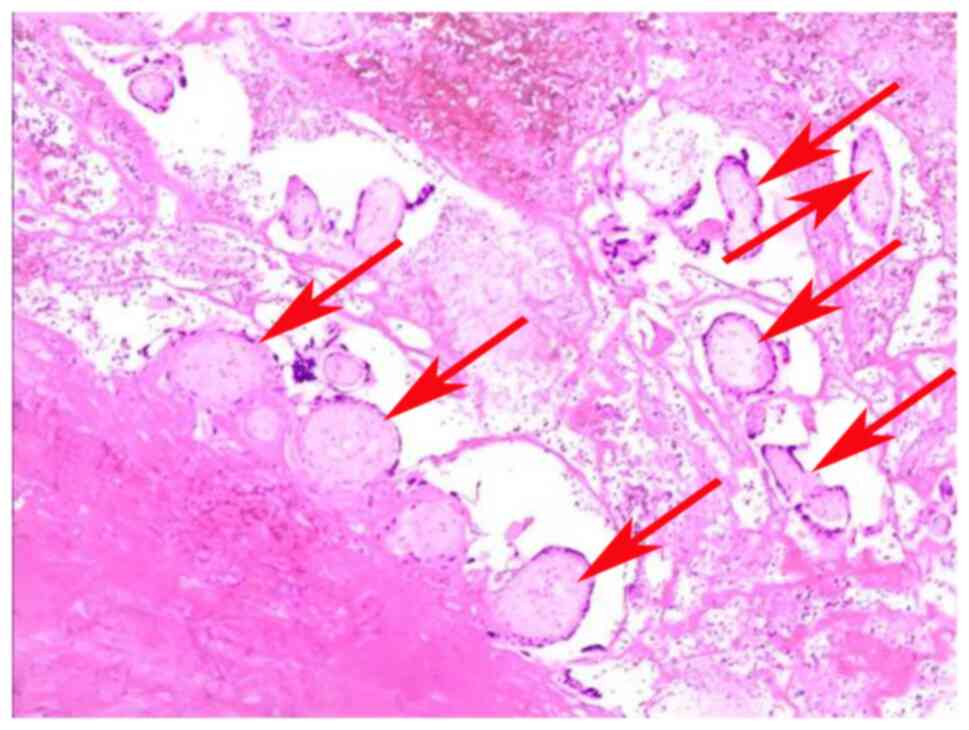

were then administered. Laparoscopic scar pregnancy resection was

performed 3 days later, where postoperative pathological specimens

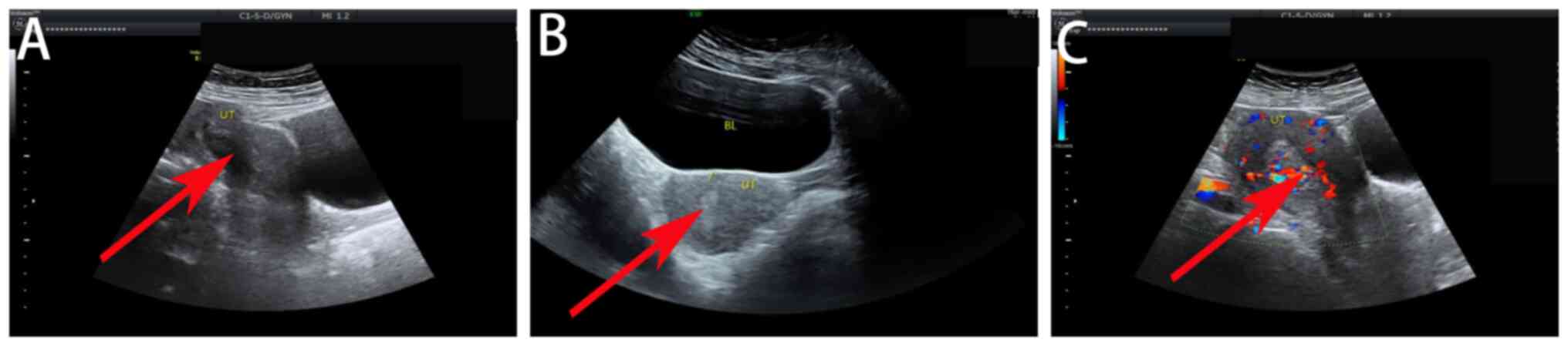

revealed chorionic tissue and trophoblast cells in case 6 (Fig. 4). The other three patients

misdiagnosed with embryonic arrest had intermittent vaginal

bleeding, and ultrasound examination 7-10 days after surgery

revealed abnormal echoes in the lower part of the uterus,

indicating CSP (Fig. 5). A single

deep intramuscular injection of methotrexate (50 mg/m2)

was administered and bilateral uterine artery embolization was

performed, followed by uterine curettage under ultrasound guidance.

All the patients recovered and were discharged after surgery.

Discussion

Scar pregnancy after cesarean section is a unique

type of ectopic pregnancy, but the cause remains unclear and has

been proposed to be associated with a defect in the decidua at the

scar site (10). Trophoblasts

directly invade the uterine muscle layer, where the villi adhere

to, implant into or even penetrate the uterine wall. The early

clinical symptoms and manifestations of CSP are atypical and can be

easily misdiagnosed as threatened miscarriage (11,12).

In the present study, three patients with early pregnancy were

diagnosed with miscarriage due to a short duration of amenorrhea.

During the first pelvic ultrasound examination, only the presence

of a gestational sac in the uterus was examined, but the position

of the gestational sac was not examined. The relationship between

the location of the gestational sac and previous cesarean section

uterine scarring were not carefully examined. During the process of

medical abortion and curettage, there was marked vaginal bleeding,

which was considered an incomplete abortion. In total, four

patients had amenorrhea for >70 days and experienced minor

vaginal bleeding. Ultrasound examination revealed no original

heartbeats in cases of intrauterine pregnancy, before only

considering it as embryonic arrest and did not carefully observe

the position of the gestational sac and its relationship with

uterine scars and the bladder, leading to the incorrect original

judgment.

CSP can be classified into types I, II and III based

on the depth, growth direction and local muscle layer thickness of

the gestational sac implanted at the scar site of the cesarean

section during ultrasound examination (13,14).

The gestational sac in type I and type II CSP can grow into the

uterine cavity. If the relationship between the gestational sac

implantation site and the cesarean scar is not considered during

the ultrasound examination, it can be easily misdiagnosed as an

intrauterine pregnancy (15). As

gestational age increases, the section of the gestational sac

protruding into the uterine cavity gradually increases, such that

its relationship with the cesarean scar becomes increasingly

unclear, with indistinguishable boundaries observed by ultrasound.

Therefore, misjudgments are prone to occur during ultrasound

examinations.

Using the sonographic reporting system for CSP in

early gestation, it is possible to reduce the misdiagnosis rate at

ultrasound examination (16). In

cases where CSP is difficult to diagnose using ultrasound,

transvaginal three-dimensional (3D) color ultrasound or MRI should

be combined to ensure timely diagnosis (17). Transvaginal ultrasonography is

considered to be the optimal imaging technique for diagnosing CSPs

due to its capabilities for soft tissue characterization, whilst

MRI can also be used to inform the decision-making process

(18). Therefore, MRI is

considered a useful complementary tool alongside transvaginal

ultrasonography for correctly diagnosing and categorizing CSPs to

inform the subsequent therapeutic approach more accurately

(19). As the gestational age

increases, not only does the difficulty of diagnosing CSP increase,

but the risk of poor treatment outcomes also increases drastically

(5,10). Termination of a midterm pregnancy

can cause severe bleeding, uterine rupture and even endanger the

life of the mother (20,21). If the patient chooses to continue

the pregnancy, the risk of serious complications, such as placental

implantation, placenta previa, uterine rupture and postpartum

hemorrhage, are increased during the middle and late stages of

pregnancy, endangering the lives of both the mother and fetus

(22,23). For patients with a history of

cesarean section who have terminated their pregnancy, a detailed

understanding of their previous pregnancy and childbirth history

should be obtained. Irregular vaginal bleeding should not be

generalized as a sign of miscarriage, whereby attention should be

paid to the source of blood supply to the gestational sac. If there

is heavy vaginal bleeding or a small amount of continuous

hemorrhage, then the operation should be suspended to avoid serious

consequences.

Performing transvaginal ultrasound examination

during early pregnancy for mothers with high-risk factors, such as

a history of pathological placenta, ectopic pregnancy and multiple

cesarean sections, can significantly improve prognosis and reduce

the occurrence of emergency surgeries (24). At present, pregnancy termination is

recommended after a clear diagnosis of scar pregnancy after

cesarean section, mainly to ensure the integrity and fertility of

the uterus, reduce the risk of major bleeding and ensure the safety

of the mother (6,10,15).

Inappropriate treatment after a misdiagnosis of CSP can lead to

hemorrhagic anemia, which can in turn render patients less tolerant

to subsequent treatment and blood coagulation (25). Mistreatment can cause CSP to evolve

into a more complex type III lump-type CSP, resulting in a more

complex and fragile local tissue structure in the cesarean scar

(25,26). When re-treated, these lump-type

masses are more likely to rupture, causing severe hemorrhage

(25,26). Therefore, remedial treatment after

misdiagnosis is frequently passive and difficult. Comprehensive

individualized considerations should be made based on the patient's

general condition, classification and previous treatment status.

Uterine artery embolization is typically the first choice of

emergency rescue treatment for hemorrhage, but caution should be

exercised regarding the possibility of disseminated intravascular

coagulation (27,28). Hysterectomy is only used as a last

resort to save the patient's life. For patients in good general

condition, such as a history of little vaginal bleeding and low

blood levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, oral mifepristone and

intramuscular injection of methotrexate can be effective (29,30).

If necessary, scar pregnancy lesion resection surgery can be

performed. However, sufficient rescue measures, such as uterine

artery embolization, surgical resection and compression hemostasis,

should be performed for heavy intraoperative bleeding.

Notably, the misdiagnosis rate of CSP varies among

different hospitals. Yu et al (31) previously reported 100 cases of CSP,

with 7 being misdiagnosed (two cases of fetal arrest, one case of

incomplete miscarriage, two cases of early pregnancy, one case of

mid-pregnancy and one case of hydatidiform mole). In another study,

Yin et al (32) reported 42

cases of CSP, amongst whom the initial symptoms varied and 14 cases

were misdiagnosed at primary hospitals (33%) before being

eventually diagnosed in Peking University First Hospital (Beijing,

China). After treatment, all patients achieved favorable

therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, in hospitals of different levels,

due to the different experience levels of obstetricians,

gynecologists and ultrasound physicians, with different symptom

manifestations, misdiagnosis rates can vary. The 940th Hospital of

the Joint Logistics Support Force of the Chinese People's

Liberation Army is located in the Gansu Province in western China,

where patients frequently face economic challenges. Amongst the 42

patients, 7 cases (16.67%) were found to be misdiagnosed. Notably,

Peking University First Hospital is a top hospital for obstetrics

and gynecology, where patients were eventually sent to this

hospital from less-specialized hospitals to confirm the diagnosis.

This highlights a gap between less-specialized and top hospitals,

implying the need for medical staff to exercise caution when making

conclusions based on lesions identified using ultrasound in this

patient population.

Misdiagnosis may be due to a number of factors. The

operator may lack experience and be unfamiliar with the ultrasound

characteristics of CSP, such as the positional relationship between

the gestational sac and scar and muscle layer thinning. These

symptoms can be confused with cervical or cornual pregnancy. This

may also be compounded by a failure to comprehensively analyze the

patient's medical history, including identifying a history of

cesarean section. In addition, low-resolution ultrasound may not be

able to clearly identify the subtle structures of gestational sacs

and scars, such as muscle layer thickness and blood flow signals,

especially during early pregnancy. Scar morphology is also

typically complex, such as scar diverticulum (defined as depression

at the incision site), which may be mistaken for a gestational sac

or conceal the true location of pregnancy. Poor scar healing,

hematoma or inflammation may further interfere with imaging.

Furthermore, excessive forward or backward bending of the uterus

may affect the probe angle and result in unclear imaging. In early

pregnancy, the gestational sac is small and has not yet been

clearly embedded in the scar tissue, which can also lead to

misdiagnosis as intrauterine pregnancy. After multiple pregnancies

or the use of assisted reproductive technology, the implantation

site of the embryo is likely to exhibit complex characteristics,

further complicating diagnosis. Additionally, it is difficult to

distinguish between cervical pregnancy and cornual pregnancy.

Obesity or intestinal gas interference, poor-quality transabdominal

ultrasound images and a lack of combined transvaginal ultrasound

examination can also contribute to missed diagnosis. The blood flow

signal around the gestational sac may not have been evaluated,

which is important given that CSP frequently presents with rich and

low obstruction of blood flow (6,10,15).

In particularly complex cases, 3D ultrasound or MRI should be

applied to clarify the spatial relationships between the

gestational sac and scar tissue.

In conclusion, in pregnant women with a history of

cesarean section, a transvaginal ultrasound examination should be

performed as soon as possible to exclude CSP. Difficulties in

diagnosis can be resolved using transvaginal 3D ultrasonography or

pelvic MRI. An accurate ultrasound investigation is necessary to

correctly diagnose CSP and select appropriate treatment plans. If

the diagnosis remains unclear, blind curettage should be avoided,

particularly when unexpected heavy bleeding occurs with

insufficient preparation, which may lead to irreversible outcomes.

The difficulty and risk of CSP remedial treatment are greater than

those of the initial treatment, where individualized comprehensive

selection should be made according to the specific situation of

each patient. The present study is limited by its retrospective

nature and limited sample size, which should be addressed in future

studies to enable suitable statistical analysis and promote the

generalizability of the findings.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Hexi University

14th Science and Technology Innovation Project (grant no. 164), the

Youth Research Project provided by the President's Fund of Hexi

University (grant no. QN2024024) and the Gansu Province University

Teacher Innovation Fund Project (grant no. 2025A-181).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XLX, WYC and YRH contributed to the drafting of the

manuscript and the design of the study. KLW, XP, RRM, QS and JXY

contributed substantially to the conceptualization and collected

data for patient cases. XLX aided with completion of the surgery.

QS and JXY approved the final version of the manuscript for

publication. XLX and JXY confirm the authenticity of all raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of

the Chinese People's Liberation Army Hospital (approval no.

2024KYLL002; Lanzhou, China) and was performed in accordance with

local legislative guidelines and the 2024 Revision of the

Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for participation

and publication was obtained from all patients included in the

present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for participation and

publication was obtained from all patients included in the present

study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Tang D, Laporte A, Gao X and Coyte PC: The

effect of the Two-child policy on cesarean section in China:

Identification using difference-in-differences techniques.

Midwifery. 107(103260)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Yin S, Zhou Y, Yuan P, Wei Y, Chen L, Guo

X, Li H, Lu J, Ge L, Shi H, et al: Hospital variations in caesarean

delivery rates: An analysis of national data in China, 2016-2020. J

Glob Health. 13(04029)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Long Q, Kingdon C, Yang F, Renecle MD,

Jahanfar S, Bohren MA and Betran AP: Prevalence of and reasons for

women's, family members', and health professionals' preferences for

cesarean section in China: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS

Med. 15(e1002672)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Armstrong F, Mulligan K, Dermott RM,

Bartels HC, Carroll S, Robson M, Corcoran S, Parland PM, Brien DO,

Brophy D and Brennan DJ: Cesarean scar niche: An evolving concern

in clinical practice. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 161:356–366.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yang XJ and Sun SS: Comparison of maternal

and fetal complications in elective and emergency cesarean section:

A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet.

296:503–512. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Silva B, Pinto VP and Costa MA: Cesarean

scar pregnancy: A systematic review on expectant management. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 288:36–43. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yan Y, Xing C, Chen J, Zheng Y, Li X, Liu

Y, Wang Z and Gong K: Provincial maternal and child information

system in Inner Mongolia, China: Descriptive implementation study.

JMIR Pediatr Parent. 7(e46813)2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM.

Electronic address: Pubs@smfm.org). Miller R, Timor-Tritsch IE and

Gyamfi-Bannerman C: Society for Maternal-fetal medicine (SMFM)

Consult Series #49: Cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

222:B2–B14. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Verberkt C, Jordans IPM, van den Bosch T,

Timmerman D, Bourne T, de Leeuw RA and Huirne JAF: How to perform

standardized sonographic examination of Cesarean scar pregnancy in

the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 64:412–418.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Alameddine S, Lucidi A, Jurkovic D,

Timor-Tritsch I, Coutinho CM, Ranucci L, Buca D, Khalil A, Jauniaux

E, Mappa I, et al: Treatments for cesarean scar pregnancy: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.

37(2327569)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Timor-Tritsch IE, Horwitz G, D'antonio F,

Monteagudo A, Bornstein E, Chervenak J, Messina L, Morlando M and

Cali G: Recurrent cesarean scar pregnancy: Case series and

literature review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 58:121–126.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Calì G,

D'Antonio F and Agten AK: Cesarean scar pregnancy: Diagnosis and

pathogenesis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 46:797–811.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lin Y, Xiong C, Dong C and Yu J:

Approaches in the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy and risk

factors for intraoperative hemorrhage: A retrospective study. Front

Med (Lausanne). 8(682368)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Du Q, Liu G and Zhao W: A novel method for

typing of cesarean scar pregnancy based on size of cesarean scar

diverticulum and its significance in clinical Decision-making. J

Obstet Gynaecol Res. 46:707–714. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gonzalez N and Tulandi T: Cesarean scar

pregnancy: A systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.

24:731–738. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Jordans IPM, Verberkt C, De Leeuw RA,

Tritsch IT, Coutinho CM, Ranucci L, Buca D, Khalil A, Jauniaux E,

Mappa I, et al: Definition and sonographic reporting system for

cesarean scar pregnancy in early gestation: Modified Delphi method.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 59:437–449. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Guo S, Wang H, Yu X, Yu Y and Wang C: The

diagnostic value of 3.0T MRI in cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J

Transl Res. 13:6229–6235. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Han X and Zhang B: Comparison of the value

of transvaginal ultrasonography and MRI in the diagnosis of

cesarean scar pregnancy: A Meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal

Med. 38(2445661)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Comune R, Liguori C, Tamburrini S, Arienzo

F, Gallo L, Dell'Aversana F, Pezzullo F, Tamburro F, Affinito P and

Scaglione M: MRI assessment of cesarean scar pregnancies: A Case

Series. J Clin Med. 12(7241)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Tanos V and Toney ZA: Uterine scar

Rupture-prediction, prevention, diagnosis, and management. Best

Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 59:115–131. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Calì G, Timor-Tritsch IE,

Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Monteaugudo A, Buca D, Forlani F, Familiari

A, Scambia G, Acharya G and D'Antonio F: Outcome of Cesarean scar

pregnancy managed expectantly: Systematic review and Meta-analysis.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 51:169–175. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Fu L, Luo Y and Huang J: Cesarean scar

pregnancy with expectant management. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.

48:1683–1690. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kennedy A, Debbink M, Griffith A, Kaiser J

and Woodward P: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: A do-not-miss

diagnosis. RadioGraphics. 44(e230199)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shi L, Huang L, Liu L, Yang X, Yao D, Chen

D, Xiong J and Duan J: Diagnostic value of transvaginal

three-dimensional ultrasound combined with color Doppler ultrasound

for early cesarean scar pregnancy. Ann Palliat Med. 10:10486–10494.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sun H, Wang J, Fu P, Zhou T and Liu R:

Systematic evaluation of the efficacy of treatments for cesarean

scar pregnancy. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 22(84)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ma R, Chen S, Xu W, Zhang R, Zheng Y, Wang

J, Zhang L and Chen R: Surgical treatment of cesarean scar

pregnancy based on the Three-category system: A retrospective

analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 24(687)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang B, Jiang ZB, Huang MS, Guan SH, Zhu

KS, Qian JS, Zhou B, Li MA and Shan H: Uterine artery embolization

combined with methotrexate in the treatment of cesarean scar

pregnancy: Results of a case series and review of the literature. J

Vasc Interv Radiol. 23:1582–1588. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

He Y, Wu X, Zhu Q, Wu X, Feng L, Wu X,

Zhao A and Di W: Combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy vs. Uterine

curettage in the uterine artery embolization-based management of

cesarean scar pregnancy: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Womens

Health. 14(116)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Stabile G, Vona L, Carlucci S, Zullo F,

Laganà AS, Etrusco A, Restaino S and Nappi L: Conservative

treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy with the combination of

methotrexate and mifepristone: A systematic review. Womens Health

(Lond). 20(17455057241290424)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Masten M and Alston M: Treatment of

recurrent Cesarean scar pregnancy with oral mifepristone, systemic

methotrexate, and ultrasound-guided suction dilation and curettage.

Cureus. 15(e36200)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Yu XL, Zhang N and Zuo WL: Cesarean scar

pregnancy: An analysis of 100 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi.

91:3186–3189. 2011.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Yin L, Tao X, Zhu YC, Yu XL, Zou YH and

Yang HX: Cesarean scar pregnancy analysis of 42 cases. Zhonghua Fu

Chan Ke Za Zhi. 44:566–569. 2009.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|