Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is an autoimmune

disorder in which pancreatic β-cells are destroyed, leading to low

insulin production and chronic hyperglycemia. Although T1DM only

accounts for 5-10% of all cases of diabetes, it still places a

heavy burden on healthcare systems because of its progressive

course and various complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis,

retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and cardiovascular disease

(1). Achieving tight glycemic

control remains challenging because intensive insulin therapy is

limited by hypoglycemia risk and glycemic variability despite

frequent monitoring (2). Achieving

tight glycemic control remains challenging, and patients with T1DM

are susceptible to microvascular and macrovascular complications

(such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and cardiovascular

disease) (3,4). As the global incidence rate of T1DM

continues to rise, ~8.4 million individuals were living with T1DM

in 2021, with 510,000 incident cases and 175,000 deaths annually

(5).

Dyslipidemia, usually characterized by an increase

in the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and a decrease in

the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, increases the

cardiovascular risk in T1DM (6-8).

These lipid changes are also associated with poor insulin signaling

and oxidative stress (9,10). Therefore, treatments that normalize

the lipid profile may help reduce the overall burden of T1DM.

Leucine (Leu), a branched-chain amino acid, is known to support

muscle health, glucose control and insulin sensitivity (11). Mechanistically, Leu activates the

mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and stimulates AMPK

signaling (e.g., via the SIRT1-AMPK axis), which promotes

fatty-acid oxidation and glucose uptake (12,13).

Leu supplementation has been shown to improve lipid handling and

relieve dyslipidemia in several animal and human studies (14-16).

However, its exact effect on T1DM-associated lipid changes,

especially on HDL and LDL, is yet to be elucidated.

Therefore, to fill the aforementioned gap in the

knowledge, the present study used a metabolomics approach with a

mouse model of T1DM. The present study investigated whether Leu

supplementation could adjust the HDL/LDL levels and the associated

downstream metabolic pathways. Male C57BL/6J mice were placed into

four groups, namely Normal, Normal with Leu supplementation

(Normal-Leu), T1DM and T1DM with Leu supplementation (T1DM-Leu).

T1DM was induced using streptozotocin (STZ) administered

intraperitoneally at 50 mg/kg/day for 5 consecutive days, and Leu

(1.5%) was provided in drinking water for 6 weeks. Plasma samples

were then used in liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

(LC-MS/MS) for metabolomic profiling and biochemical assays of

plasma triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol (LDL-C).

Materials and methods

Materials

Leu and STZ were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA. Isoflurane, acetonitrile and methanol were obtained from

Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Assay kits for

plasma glucose [Glucose (GOD-POD) Assay Kit], triglycerides

[Triglyceride (GPO-PAP) Assay Kit], total cholesterol [Total

Cholesterol (CHOD-PAP) Assay Kit], HDL-C [Direct HDL-C Assay Kit],

LDL-C [Direct LDL-C Assay Kit], and whole-blood glycated hemoglobin

(HbA1c) [Boronate-affinity HbA1c Assay Kit] were from Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., and were used

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Animals

A total of 40 male C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old; 20-24

g at study start) were used. Mice were obtained from Shanghai SLAC

Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. and acclimatized for 1 week. Animals

were randomly assigned to four groups (n=10/group): Normal,

Normal-Leu, T1DM and T1DM-Leu. All procedures conformed to the

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition)

(17) and the ARRIVE guidelines

2.0(18), and were approved by the

IACUC of Xiamen University (approval no. 20210305042). Mice were

housed in an SPF facility under 22±2˚C, 50±10% relative humidity, a

12:12 h light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to standard

chow and water; 4-5 mice per cage with corncob bedding and

environmental enrichment. Anesthesia was induced using 4-5%

isoflurane in 1 l/min oxygen via an induction chamber and

maintained at 1.5-2% using a nose cone during blood collection.

Euthanasia was carried out using ≥5% isoflurane to for ≥3 min.

Death was confirmed by the absence of respiration, heartbeat and

corneal reflex. Every effort was made to minimize the discomfort to

the animals. Humane endpoints were predefined as ≥20% body-weight

loss, severe dehydration/ketonuria with prostration, persistent

hypothermia/recumbency or inability to eat/drink; animals reaching

any endpoint would be euthanized by isoflurane overdose. No animals

reached a humane endpoint prior to planned study termination.

Induction of T1DM

STZ (50 mg/kg/day) was freshly dissolved in cold 0.1

M sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) at 5 mg/ml. A volume of 10 ml/kg

(0.20-0.25 ml per 20-25 g mouse) was administered intraperitoneally

once daily for five consecutive days (17); control groups received equal-volume

citrate buffer i.p. Additionally, the Normal-Leu and T1DM-Leu

groups received 1.5% Leu in their drinking water, while the Normal

and T1DM groups received drinking water without additions (18). Diabetes was confirmed 7 days after

the last STZ injection when fasting blood glucose ≥12 mmol/l was

recorded from tail-vein blood (~5 µl) using a handheld glucometer

after a 6 h fast (water ad libitum); one sample per mouse

was taken for confirmation.

Plasma preparation

On week 6 following STZ-induced T1DM, mice were

anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized. Blood (0.8-1.0 ml per

mouse) was collected by cardiac puncture into pre-chilled K2-EDTA

microtubes and the entire volume was centrifuged at 2,000 x g for

10 min at 4˚C to obtain plasma, which was stored at -20˚C. Plasma

from six randomly selected mice per group was used for LC-MS/MS,

and plasma from all animals was used for biochemical assays.

Metabolomics analysis

Plasma samples (100 µl) were mixed with 400 µl

methanol, vortexed and sonicated to precipitate proteins. After

centrifugation (15,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C), the supernatants

were dried under nitrogen (35˚C; nebuliser pressure 15 psi),

reconstituted in 100 µl acetonitrile and centrifuged again at

15,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C. A 2 µl aliquot was injected into a

UPLC-QTOF-MS system (Waters Xevo G2-XS QTOF with an ACQUITY BEH C18

1.8 µm 2.1x50 mm column; Waters Corporation), using electrospray

ionization in positive mode. The mobile phase consisted of 0.01%

formic acid in water (solvent A) or acetonitrile (solvent B) with a

flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The gradient elution used was 0-1 min with

10% solvent B, 1-7.5 min with 10-65% solvent B, 7.5-10.5 min with

65-100% solvent B and 10.5-12 min with 100-10% solvent B.

Leucine-enkephalin (m/z 556.2771) was infused for lock-mass

calibration. A pooled quality control (QC) sample was prepared by

combining 10 µl aliquots of each extract. Five QC injections were

used at the start to condition the system; one QC was injected

every eight study samples; and three QC injections were run at the

end. All injections were randomized and interleaved with blank

samples.

Raw data were processed using Progenesis QI (version

2.4; Nonlinear Dynamics; Waters Corporation). After alignment to

the third QC injection, ion features were extracted, normalized

with the total ion current and corrected for drift using QC-based

locally estimated scatterplot smoothing. Features with a relative

SD of >30% in QCs or present in <80% of QC samples were

excluded. All detected ion features have been deposited in the

MassIVE repository (accession no. MSV000099368). Multivariate and

pathway analyses were conducted using MetaboAnalyst version 5.0

(https://www.metaboanalyst.ca). Principal

component (PC) analysis was used for visualization. For metabolite

set enrichment analysis (MSEA), differential ions were first

selected using the volcano plot criteria (a fold change of more

than two; P<0.05) and mapped to pathways in the Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (https://www.kegg.jp). Pathways with a P-value of

<0.05 and more than or equal to two matched metabolites were

considered significant. Metabolite annotation was based on accurate

m/z and MS/MS spectrum matches against the Human Metabolome

Database (https://hmdb.ca).

Biochemical measurements

Plasma glucose, TG, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL

were quantified in plasma samples, whereas HbA1c was determined

from whole blood (erythrocyte hemolysates), using the respective

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. kits according

to the manufacturer's protocols.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out using SPSS version 16.0

(SPSS, Inc.). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was

used for multiple-group comparisons. Data are presented as mean ±

SD or as box-and-whisker plots (median, interquartile range and

10-90th percentiles) as specified in the figure legends. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Biochemical outcomes (glucose, TG, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and

HbA1c) were measured in 10 mice per group (biological replicates);

each assay was run in duplicate and the mean was used for

statistics. Untargeted metabolomics used plasma from 6 mice per

group.

Results

Metabolite profiling and pathway

analysis

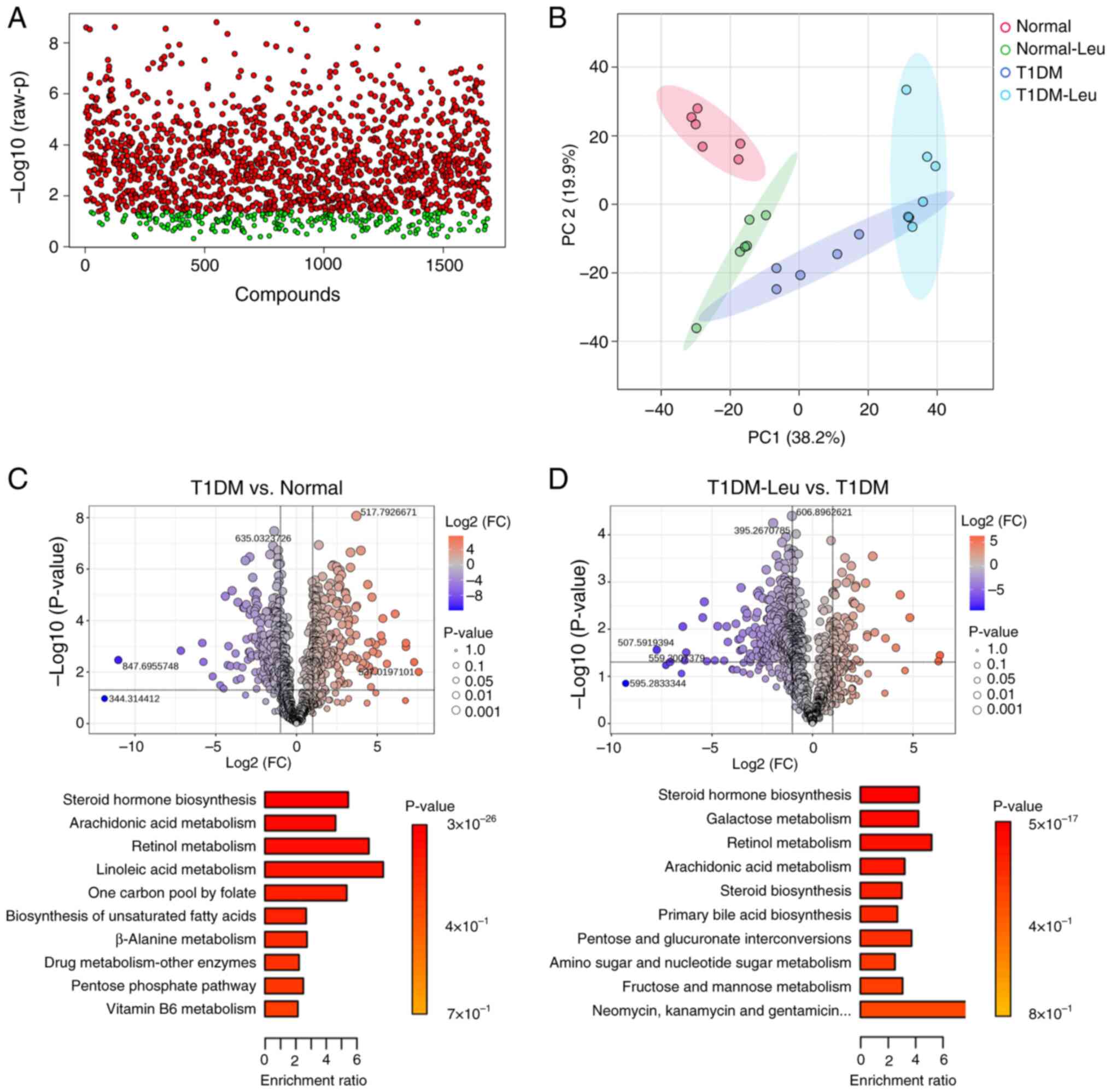

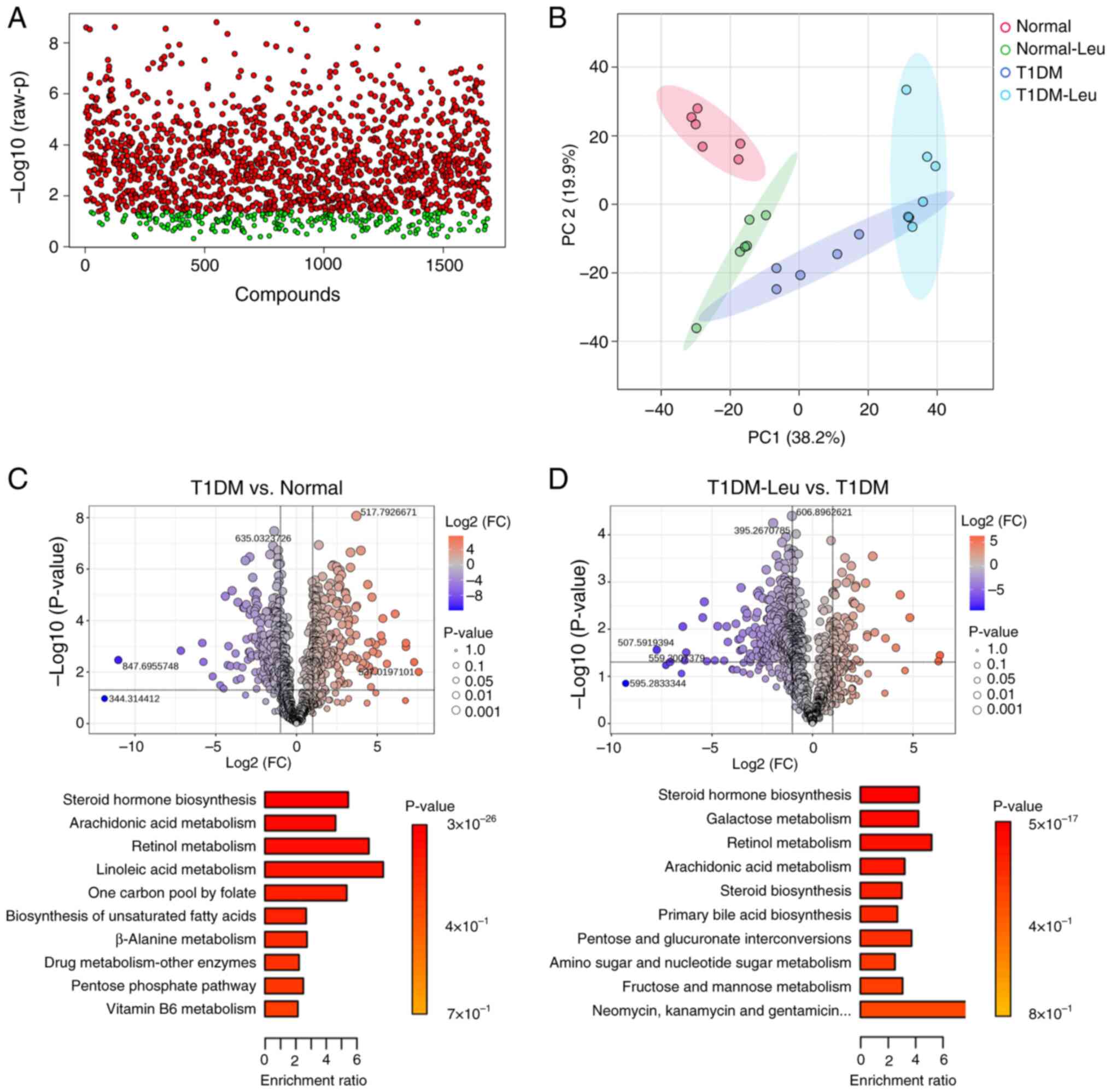

Untargeted LC-MS/MS detected 1,692 ion features in

the plasma of mice. After excluding peaks with a QC relative SD

>30% in QCs (Fig. 1A) and

applying an interquartile range filter, 888 features remained for

statistical evaluation. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc

test identified ions with significant differences among the four

groups (FDR-adjusted P<0.05; full list provided in the public

MassIVE dataset) (Fig. 1A). PC

analysis further revealed a clear metabolic separation between the

Normal, Normal-Leu, T1DM and T1DM-Leu group clusters. Where PC1 and

PC2 accounted for 38.2 and 19.9% of the total variance,

respectively (Fig. 1B).

| Figure 1Metabolomic overview of plasma

samples. (A) One-way ANOVA of 1,692 detected ion features after

quality-control filtering (relative SD >30%), followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. Red dots represent ions with P-values of

<0.05; green dots represent non-significant ions. (B) PC

analysis scores plot illustrating the separation of the Normal,

Normal-Leu, T1DM and T1DM-Leu groups. PC1 and PC2 explain 38.2 and

19.9% of the variance, respectively. (C) The top panel shows a

volcano plot of the differential features in the T1DM vs. Normal

group comparison (FC, >2; P<0.05). The bottom panel shows the

KEGG MSEA of the top 10 pathways altered in the mice in the T1DM

group compared with those in the Normal group. (D) The top panel

shows a volcano plot of the differential features in the T1DM-Leu

vs. T1DM group comparison (FC, >2; P<0.05). The bottom panel

shows the KEGG MSEA of the top 10 pathways modulated by Leu

supplementation in mice with T1DM. Leu, leucine; Normal-Leu, Normal

with 1.5% Leu supplementation; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus;

T1DM-Leu, T1DM with 1.5% Leu supplementation; PC, principal

component; FC, fold-change; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes; MSEA, metabolite-set enrichment analysis. |

Pairwise analyses were then carried out. In the T1DM

vs. Normal comparison, 227 features were higher in T1DM

(upregulated) and 186 were lower in T1DM (downregulated) relative

to Normal (Fig. 1C). KEGG-based

MSEA (using a criteria of P<0.05 and more than or equal to two

hits) pointed to marked disturbances in steroid-hormone

biosynthesis, arachidonic-acid metabolism, retinol metabolism,

linoleic-acid metabolism and a number of lipid-related pathways

(Fig. 1C). Compared with mice in

the untreated T1DM group, Leu supplementation in the T1DM-Leu group

resulted in an increase in 75 features and a decrease in 251

features (Fig. 1D). Enrichment

analysis indicated that Leu modulated steroid-hormone biosynthesis,

arachidonic-acid metabolism, galactose metabolism,

pentose-and-glucuronate interconversions and primary bile-acid

biosynthesis (Fig. 1D). In

summary, these results indicated that Leu treatment may partially

reverse the metabolic disruptions of untreated T1DM, especially

within pathways associated with lipid and bile-acid metabolism.

Key metabolites affected by Leu

supplementation

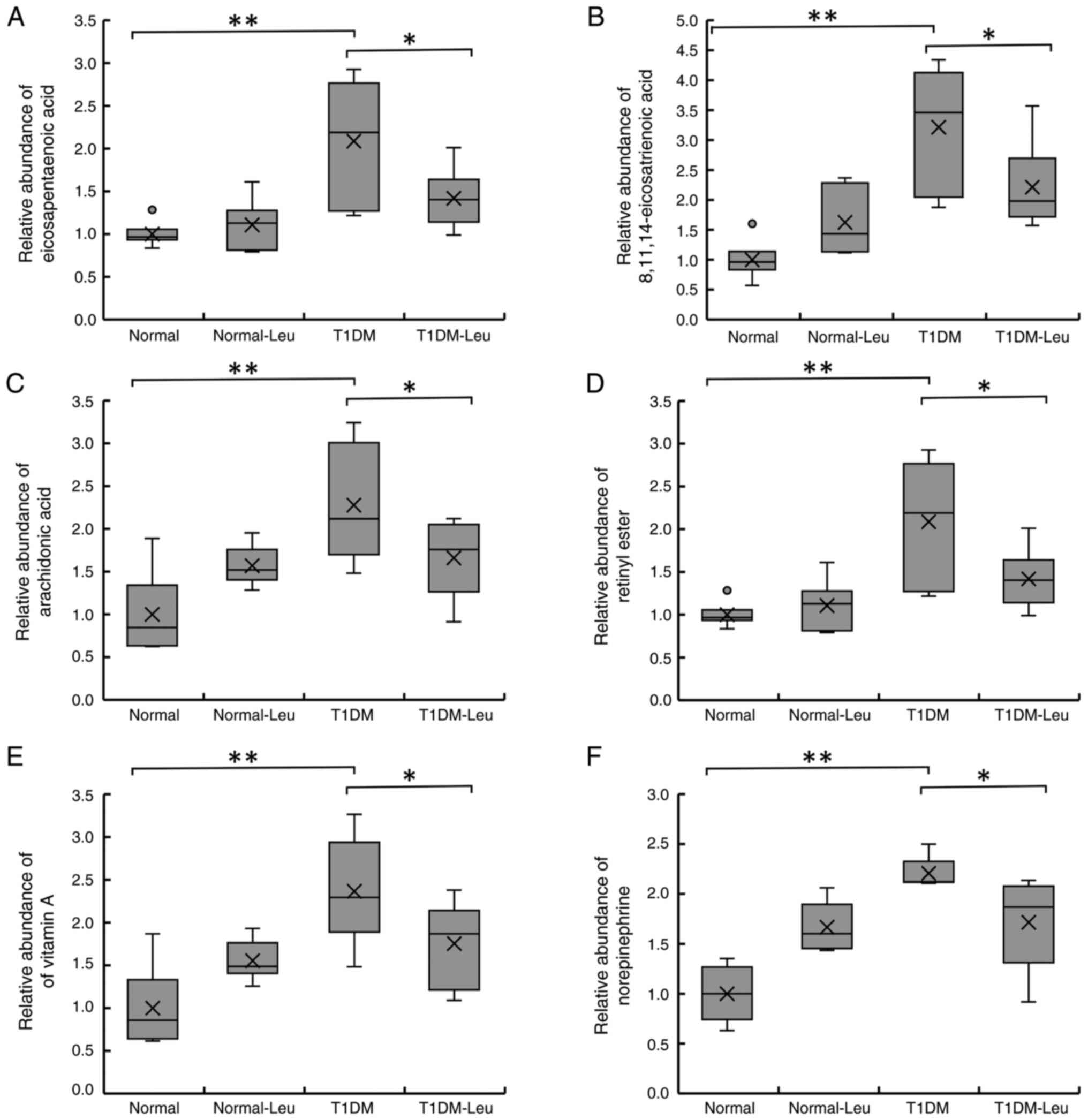

Fig. 2 indicates

that eicosapentaenoic acid, 8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid,

arachidonic acid, retinyl ester, vitamin A and norepinephrine

levels were significantly higher in the T1DM group compared with

the Normal control group, and Leu supplementation (T1DM-Leu)

reduced these metabolites toward control levels. After 6 weeks of

treatment with 1.5% Leu, there was a significant decrease in each

of these metabolites in the mice in the T1DM-Leu group. Across all

six metabolites (eicosapentaenoic acid, 8,11,14-eicosatrienoic

acid, arachidonic acid, retinyl ester, vitamin A and

norepinephrine), levels in the T1DM group were higher than those in

the Normal group (P<0.01), whereas leucine supplementation

lowered these levels in the T1DM-Leu group compared with T1DM

(one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; P<0.05). In most

cases, T1DM-Leu values were intermediate between T1DM and

Normal/Normal-Leu, and Leu alone did not differ from Normal. These

changes indicated that Leu may potentially oppose the

lipid-inflammatory and retinoid disturbances associated with

early-stage T1DM.

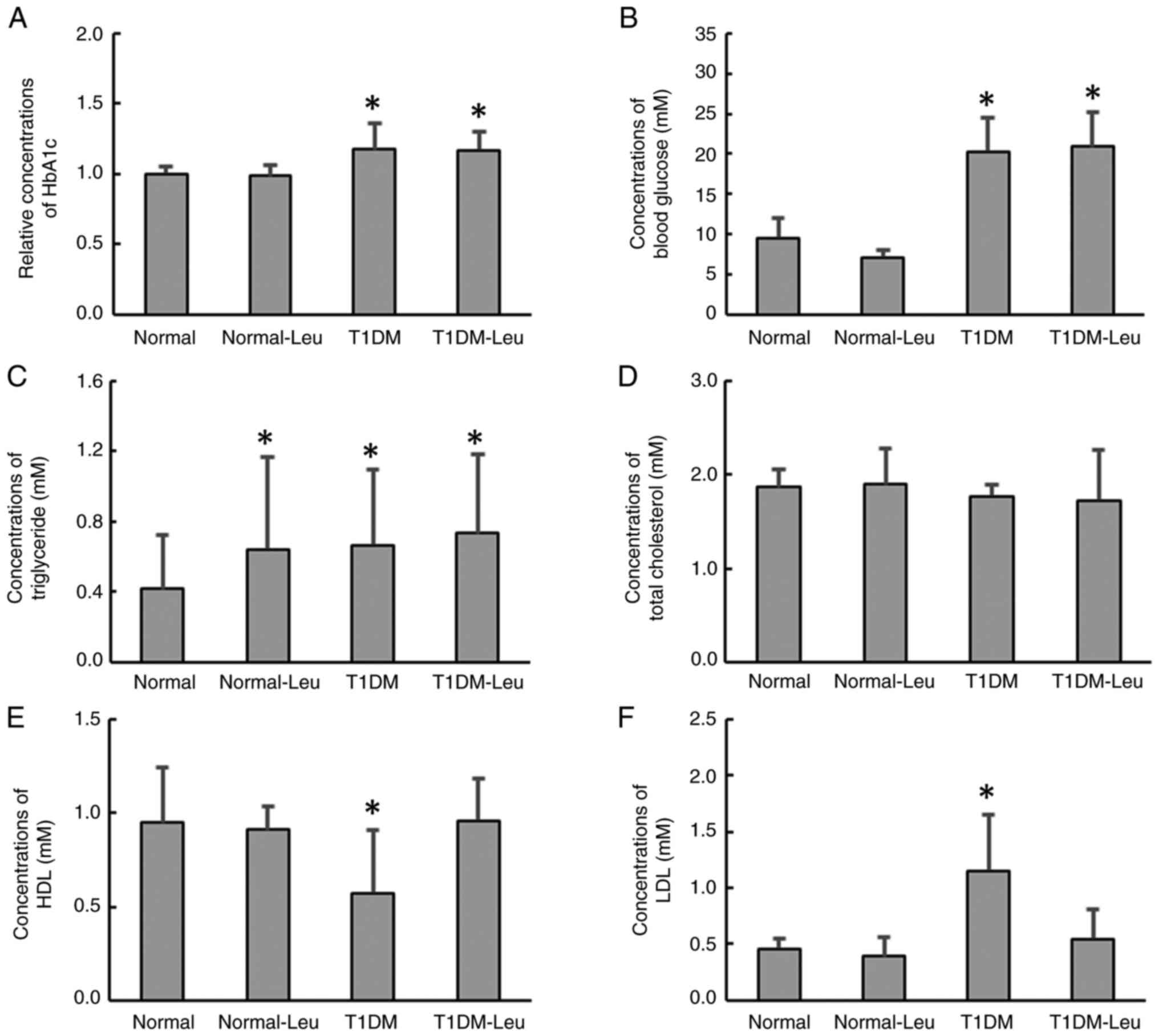

Biochemical analyses

HbA1c and fasting blood glucose were significantly

higher in the T1DM group compared with the Normal group. In the

T1DM-Leu group, both indices remained elevated and were not

significantly different from the T1DM group (Fig. 3A and B). TG levels were significantly higher

than in the Normal group in all three intervention groups; however,

there were no significant differences among the intervention groups

(Fig. 3C). There were no

significant differences in the total cholesterol levels between the

Normal and the treatment groups (Fig.

3D). HDL levels were significantly reduced in the T1DM group

compared with the Normal group; however, in the T1DM-Leu group, the

HDL levels were similar to the levels in the Normal group (Fig. 3E). By contrast, LDL levels were

significantly increased in the T1DM group compared with the Normal

group, whereas the LDL levels in the T1DM-Leu group were similar to

the levels in the Normal and Normal-Leu groups (Fig. 3F).

Discussion

The findings of the present study suggested that Leu

supplementation may mitigate the metabolic disturbances in T1DM,

particularly in lipid metabolism. In the plasma metabolomics data,

eicosapentaenoic acid, 8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid, arachidonic

acid, retinyl ester, vitamin A and norepinephrine were lower in

T1DM-Leu than in T1DM mice. Taken together with the

pathway-enrichment results (MetaboAnalyst/KEGG), these findings

suggest a partial amelioration of lipid-related pathways, including

arachidonic-acid metabolism (KEGG map00590), linoleic-acid

metabolism (map00591), and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids

(map01040), as well as retinol metabolism (map00830).

Altered levels of arachidonic acid and associated

lipid metabolites are implicated in inflammation and insulin

resistance, and their dysregulation contributes to diabetic

complications such as cardiovascular disease and nephropathy

(19,20). Reduced levels of retinyl ester and

vitamin A are observed in mice with diabetes and may exacerbate

oxidative stress-for example, mitochondrial ROS overproduction,

NADPH oxidase/AGE-RAGE-driven lipid peroxidation- and weaken

antioxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and

glutathione peroxidase (21).

Therefore, the Leu-mediated reduction of these metabolites in the

mice with T1DM may potentially represent a protective metabolic

shift. Additionally, norepinephrine dysregulation is associated

with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular issues in patients

with diabetes (22). This suggests

that the reduction of the norepinephrine levels in the mice with

T1DM following Leu supplementation may be of clinical

importance.

The results of the present study revealed that Leu

supplementation also helped restore the HDL and LDL levels in mice

with T1DM, which potentially suggested a favorable effect on

lipoprotein profiles. HDL-cholesterol is well known to have

protective cardiovascular effects by promoting reverse cholesterol

transport, reducing inflammation and improving endothelial

function. However, elevated LDL-cholesterol levels accelerates

atherogenesis, which notably increases the risk of cardiovascular

complications in diabetes (23).

Therefore, restoring the balance of HDL and LDL with Leu

supplementation may potentially offer cardiovascular benefits in

the management of T1DM. The findings of the present study align

with those of previous studies that demonstrate beneficial effects

of Leu on glucose and lipid metabolism (18,24,25).

Mechanistically, Leu may benefit T1DM via the activation of mTOR

and AMPK, which are pathways that regulate metabolic processes

(26-31).

For example, AMPK activation inhibits lipogenesis, promotes fatty

acid oxidation and improves lipid homeostasis, processes that are

often impaired in diabetes (32).

Furthermore, mTOR activation by Leu modulates lipid metabolism

through the regulation of lipid synthesis genes and mitochondrial

function (12). These previously

identified mechanisms align with the findings of the present study,

which indicated that Leu supplementation corrected T1DM-induced

metabolic dysregulation of lipid pathways. In addition, enrichment

analysis showed shifts in galactose metabolism and primary

bile-acid biosynthesis, which suggested that Leu may also influence

carbohydrate metabolism and bile-acid signaling in mice with T1DM,

both of which can influence lipid homeostasis. Therefore, these

secondary pathways may warrant further follow-up experiments in the

future.

However, not all metabolites investigated in the

present study exhibited identical degrees of modulation. For

example, after Leu supplementation, the levels of arachidonic acid,

8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid (20:3 n-6) and eicosapentaenoic acid

(20:5 n-3) were significantly reduced in T1DM-Leu vs. T1DM mice,

although the magnitude of change varied across metabolites,

indicating a possible selective modulation of inflammatory and

lipid pathways. Furthermore, vitamin A levels were partially, but

significantly, restored. These differential responses may reflect

distinct underlying regulatory mechanisms or pathway-specific

sensitivities to Leu intervention.

In the present study, although supplementary Leu did

not significantly lower blood glucose or HbA1c levels compared with

those in the T1DM-only group, the selective improvement in lipid

parameters suggested the potential utility of Leu in addressing

dyslipidemia in T1DM. These results align with previous findings in

which Leu supplementation is associated with improved lipid

metabolism and cardiovascular health (7,15,33-35).

However, there were limitations of the present

study. For example, the present study only focused on early-stage

T1DM without examining advanced disease settings. Additionally, the

present study did not fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms

through which Leu exerted its effects. Therefore, future studies

are needed for a more comprehensive evaluation. Finally, the safety

and potential adverse effects of chronic Leu use are yet to be

assessed. Overall, the findings of the present study supported the

hypothesis that Leu supplementation may offer therapeutic benefits

in T1DM by correcting imbalances in key lipids (for example,

arachidonic acid, 8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid, eicosapentaenoic

acid, retinyl ester/vitamin A and HDL/LDL) and by modulating

metabolic pathways highlighted by our analysis, including

arachidonic/linoleic-acid and retinol metabolism, steroid-hormone

biosynthesis, galactose metabolism and primary bile-acid

biosynthesis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Fujian Province, China (grant no. 2022D024) and the

Xiamen Municipal Health Commission Guiding Project (grant no.

3502Z20244ZD1151).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the MassIVE database under accession number MSV000099368 or at

the following URL: https://doi.org/10.25345/C5MG7G83D.

Authors' contributions

JY contributed to the conception and design of the

present study. DT, CF, GX, TY and RZ contributed to the data

collection, analysis and interpretation of results. DT and CF

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data generated and analyzed

in this study. JY prepared the draft of the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal procedures were performed in accordance

with the guidelines and regulations approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Xiamen University (Xiamen, China;

approval no. 20210305042).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS and Michels AW:

Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 383:69–82. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Maahs DM, West NA, Lawrence JM and

Mayer-Davis EJ: Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab

Clin North Am. 39:481–497. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

de Ferranti SD, de Boer IH, Fonseca V, Fox

CS, Golden SH, Lavie CJ, Magge SN, Marx N, McGuire DK, Orchard TJ,

et al: Type 1 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: A

scientific statement from the American heart association and

American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 37:2843–2863.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Forbes JM and Cooper ME: Mechanisms of

diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 93:137–188. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Gregory GA, Robinson TIG, Linklater SE,

Wang F, Colagiuri S, de Beaufort C and Donaghue KC: International

Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas Type 1 Diabetes in Adults

Special Interest Group. Magliano DJ, Maniam J, et al: Global

incidence, prevalence, and mortality of type 1 diabetes in 2021

with projection to 2040: A modelling study. Lancet Diabetes

Endocrinol. 10:741–760. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tell S, Nadeau KJ and Eckel RH: Lipid

management for cardiovascular risk reduction in type 1 diabetes.

Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 27:207–214. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wang X, Pei J, Zheng K and Hu X:

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are associated with

major adverse cardiovascular events in male but not female patients

with hypertension. Clin Cardiol. 44:723–730. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH,

Monroe HM, McQueen MJ, de Graaf J and Furberg CD: A meta-analysis

of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density

lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of

cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 4:337–345.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wu X and Xiao B: TDAG51 attenuates

impaired lipid metabolism and insulin resistance in gestational

diabetes mellitus through SREBP-1/ANGPTL8 pathway. Balkan Med J.

40:175–181. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Marques CL, Beretta MV, Prates RE, de

Almeida JC and da Costa Rodrigues T: Body adiposity markers and

insulin resistance in patients with type 1 diabetes. Arch

Endocrinol Metab. 67:401–407. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mero A: Leucine supplementation and

intensive training. Sports Med. 27:347–358. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Laplante M and Sabatini DM: mTOR signaling

in growth control and disease. Cell. 149:274–293. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Horman S, Browne G, Krause U, Patel J,

Vertommen D, Bertrand L, Lavoinne A, Hue L, Proud C and Rider M:

Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase leads to the

phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 and an inhibition of protein

synthesis. Curr Biol. 12:1419–1423. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhang Y, Guo K, LeBlanc RE, Loh D,

Schwartz GJ and Yu YH: Increasing dietary leucine intake reduces

diet-induced obesity and improves glucose and cholesterol

metabolism in mice via multimechanisms. Diabetes. 56:1647–1654.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang L, Li F, Guo Q, Duan Y, Wang W,

Zhong Y, Yang Y and Yin Y: Leucine supplementation: A novel

strategy for modulating lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis.

Nutrients. 12(1299)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Bishop CA, Schulze MB, Klaus S and

Weitkunat K: The branched-chain amino acids valine and leucine have

differential effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. FASEB J.

34:9727–9739. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chaudhry ZZ, Morris DL, Moss DR, Sims EK,

Chiong Y, Kono T and Evans-Molina C: Streptozotocin is equally

diabetogenic whether administered to fed or fasted mice. Lab Anim.

47:257–265. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Jiao J, Han SF, Zhang W, Xu JY, Tong X,

Yin XB, Yuan LX and Qin LQ: Chronic leucine supplementation

improves lipid metabolism in C57BL/6J mice fed with a

high-fat/cholesterol diet. Food Nutr Res. 60(31304)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang T, Fu X, Chen Q, Patra JK, Wang D,

Wang Z and Gai Z: Arachidonic acid metabolism and kidney

inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 20(3683)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sears B and Perry M: The role of fatty

acids in insulin resistance. Lipids Health Dis.

14(121)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Brun PJ, Yang KJZ, Lee SA, Yuen JJ and

Blaner WS: Retinoids: Potent regulators of metabolism. Biofactors.

39:151–163. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tentolouris N, Argyrakopoulou G and

Katsilambros N: Perturbed autonomic nervous system function in

metabolic syndrome. Neuromolecular Med. 10:169–178. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Vergès B: Pathophysiology of diabetic

dyslipidaemia: Where are we? Diabetologia. 58:886–899.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rivera ME, Lyon ES, Johnson MA and Vaughan

RA: Leucine increases mitochondrial metabolism and lipid content

without altering insulin signaling in myotubes. Biochimie.

168:124–133. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Fu L, Li F, Bruckbauer A, Cao Q, Cui X, Wu

R, Shi H, Xue B and Zemel MB: Interaction between leucine and

phosphodiesterase 5 inhibition in modulating insulin sensitivity

and lipid metabolism. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 8:227–239.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Holowaty MNH, Lees MJ, Abou Sawan S,

Paulussen KJM, Jäger R, Purpura M, Paluska SA, Burd NA, Hodson N

and Moore DR: Leucine ingestion promotes mTOR translocation to the

periphery and enhances total and peripheral RPS6 phosphorylation in

human skeletal muscle. Amino Acids. 55:253–261. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Azzout-Marniche D: New insight into the

understanding of muscle glycolysis: Sestrins, key pivotal proteins

integrating glucose and leucine to control mTOR activation. J Nutr.

153:915–916. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Cui C, Wu C, Wang J, Zheng X, Ma Z, Zhu P,

Guan W, Zhang S and Chen F: Leucine supplementation during late

gestation globally alters placental metabolism and nutrient

transport via modulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in

sows. Food Funct. 13:2083–2097. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang MM, Guo HX, Huang YY, Liu WB, Wang X,

Xiao K, Xiong W, Hua HK, Li XF and Jiang GZ: Dietary leucine

supplementation improves muscle fiber growth and development by

activating AMPK/Sirt1 pathway in blunt snout bream (megalobrama

amblycephala). Aquac Nutr. 2022(7285851)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Martin SB, Reiche WS, Fifelski NA, Schultz

AJ, Stanford SJ, Martin AA, Nack DL, Radlwimmer B, Boyer MP and

Ananieva EA: Leucine and branched-chain amino acid metabolism

contribute to the growth of bone sarcomas by regulating AMPK and

mTORC1 signaling. Biochem J. 477:1579–1599. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Chen X, Xiang L, Jia G, Liu G, Zhao H and

Huang Z: Leucine regulates slow-twitch muscle fibers expression and

mitochondrial function by Sirt1/AMPK signaling in porcine skeletal

muscle satellite cells. Anim Sci J. 90:255–263. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Herzig S and Shaw RJ: AMPK: Guardian of

metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

19:121–135. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yun SY, Rim JH, Kang H, Lee SG and Lim JB:

Associations of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and

apolipoprotein B with cardiovascular disease occurrence in adults:

Korean genome and epidemiology study. Ann Lab Med. 43:237–243.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lynch CJ and Adams SH: Branched-chain

amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 10:723–736. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

McCormack SE, Shaham O, McCarthy MA, Deik

AA, Wang TJ, Gerszten RE, Clish CB, Mootha VK, Grinspoon SK and

Fleischman A: Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations

are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in

children and adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 8:52–61. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|