Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most prevalent

type of head and neck cancer globally, accounting for ~120,434 new

cases and 73,482 deaths annually (1). The highest age-standardized incidence

rates (ASIRs) are observed in East and Southeast Asia, including

Singapore, the Maldives and Indonesia (ASIRs ~7); Malaysia and

Vietnam (~6); and China (~3) (2).

In Vietnam, NPC ranks among the top 10 cancers, with 5,613 new

cases (3.1% of all cancers) and 3,453 deaths (2.9%) annually. The

current 5-year incidence rate is 16,007 individuals (3).

Radiotherapy is the main treatment for NPC. While

early-stage cases may be effectively managed with radiotherapy

alone, intermediate- and late-stage diagnoses often require

concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy (2). A main concern during treatment is

malnutrition, driven by both the disease and its treatment side

effects. Radiation therapy, in particular, is associated with high

malnutrition rates, with hypoproteinemia-related symptoms including

weight loss, lower limb edema and cachexia (4,5).

Malnutrition weakens the immune system, prolongs the period of

hospitalization, aggravates the side-effects of radiotherapy,

interrupts treatment schedules, and worsens the prognosis and

quality of life (QOL) of patients (6,7).

Malnutrition often begins early in the course of

treatment and worsens over time (8). Studies have reported that 20.2% of

patients lose >10% of their body weight during chemoradiotherapy

(9), and malnutrition prevalence

can rise from 16.8% pre-treatment to 91.2% post-treatment (10). Wei et al (11) reported a severe malnutrition rate

of 80.7% during radiotherapy, while Zhuang et al (12) found that 69.0% of patients were

malnourished upon the completion of treatment.

Can Tho Oncology Hospital (Can Tho, Vietnam), a

grade I facility serving as a specialized center in the Mekong

Delta region of Vietnam, is the only hospital in Can Tho City

equipped with a radiotherapy machine. Of note, >100 patients

with NPC from across the region are treated annually at this

hospital. However, nutritional neglect during treatment often leads

to delayed and prolonged periods of hospitalization.

To address this issue, a nutritional assessment

program has been initiated to detect malnutrition early and guide

timely interventions to improve the overall QOL of patients. The

present study aimed to assess the nutritional status and QOL of

patients with NPC at Can Tho Oncology Hospital in 2024, using the

Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) and the

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality

of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). The PG-SGA is used to assess

nutritional status, helping to identify malnutrition early for

timely intervention. The EORTC QLQ-C30 evaluates the QOL, guiding

improvements in patient care and overall well-being.

Patients and methods

Study population

The present study included patients with NPC treated

at Can Tho Oncology Hospital from February, 1 to December, 31,

2024. The eligibility criteria included an age ≥18 years and a

histopathological diagnosis of primary NPC. Patients with severe

dementia or mental disorders precluding cooperation were excluded.

All patients were fully informed and voluntarily consented to

participate in the study. Ethics approval was first obtained from

Can Tho Oncology Hospital on February 1, 2024 according to Decision

no. 02/HĐĐĐ-BVUBCT (Cantho, Vietnam). The present study was also

then approved by the Ethics Committee of Hanoi Medical University

(Hanoi, Vietnam) under Decision no. NCS2024/ GCN-HMUIRB, dated May

15, 2024. It is understood that the study team provided the

potential participants with study-related information on the

contents and objectives of the study and sought their consent to

participate by signing the consent form.

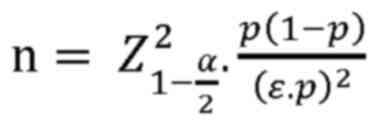

Study design

The present study was a descriptive cross-sectional

study using convenience sampling. The sampling technique used was

non-probability sampling. As regards sample size and sample

selection, the sample size was calculated according to the formula

for calculating the estimated sample size of 1 mean with the

population sample size, as follows:

where ‘α’ represents the type 1 error, α=0.05;

=1.96 (equivalent to 95% confidence

level); and ‘ε’ represents the relative estimation error, ε=0.1.

According to the study by Wei et al (11), 80.7% of patients wth NPC received

chemoradiotherapy. Substituting into the formula, the sample size

was n=92. In fact, the present study collected data from 129

patients.

The present study investigated patients diagnosed

with NPC who received various treatment modalities, including

chemotherapy (specifically cisplatin, carboplatin, gemcitabine, or

5-fluorouracil), radiotherapy alone, or a combination of

chemoradiotherapy (utilizing cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil). Medical

records provided the number, location, stage and size of primary

tumors; the type of the most recent primary tumor; the number and

types of treatments; and the start and end dates of each

treatment.

Nutritional assessments and interventions are not

standard practice for NPC in a research location. Nutritional

therapy, encompassing both enteral and parenteral nutrition, was

administered to patients at risk of malnutrition based on physician

discretion rather than nutritionists. The records only indicated

whether patients received nutritional therapy, without specifying

the types of therapies prescribed or their adequacy for addressing

malnutrition.

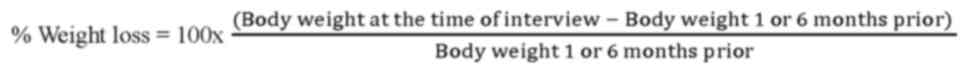

Assessment of nutritional status

Data were collected through structured

questionnaires covering demographics, the PG-SGA-based nutritional

assessment tool, and anthropometric and biochemical measurements.

Body weight (kg) and height (cm) were recorded, and percentage

weight loss was calculated as follows:

The PG-SGA evaluates weight loss history, dietary

intake, gastrointestinal symptoms, functional status and physical

signs (e.g., fat/muscle wasting, edema) (13,14).

Scoring thresholds were as follows: 0-1, well-nourished; 2-3,

moderate or suspected malnutrition, warranting patient and family

education; 4-8, severe malnutrition requiring intervention; and ≥9,

critical malnutrition necessitating urgent nutritional support.

Assessment of QOL

QOL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30, a

well-validated cancer-specific tool (15), and has been validated in Vietnamese

cancer populations (16). The

questionnaire comprises 30 items covering five functional domains

(physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), symptom scales

(e.g., fatigue, pain) and a global health/QOL scale (17,18).

Scores were calculated and linearly transformed (range 0-100), with

higher functional/global scores indicating an improved QOL and

higher symptom scores indicating worse symptoms (16).

Data collection

Self-report questionnaires collected demographic

data (age, sex, education level, etc.) and disease-related

information (cancer stage, treatment, etc.). All eligible patients

who consented were asked to complete the self-report questionnaire,

PG-SGA and QLQ-C30 upon their initial admission to the inpatient

chemotherapy and radiotherapy department. The investigators

assisted patients who had difficulty answering the questions,

ensuring that all questions were fully answered within 10-15 min.

Clinical staff completed the clinician-assessed PG-SGA section

immediately upon receiving the questionnaires from the

patients.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered using Epidata 3.1 and analyzed

using SPSS 22 software (IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics were

reported as frequencies, percentages, and the mean ± standard

deviation (SD). Differences in age groups, sex, education levels,

cancer stages, treatment types (chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

chemoradiotherapy, or others), and nutritional status (malnourished

vs. well-nourished patients) were analyzed using the Chi-squared

test. However, in the case that >20% of the cells had expected

frequencies <5, Fisher's exact test was applied instead. The

Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare PG-SGA scores and QOL

scores due to non-normal distribution. The association between

malnutrition and QOL was analyzed using linear regression analyses.

In linear regression analyses using the enter method, the PG-SGA

score, sex (male vs. female), age (years), feeding route (oral vs.

tube) and disease stage (I-IV) were included as predictors. A value

of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

The present study included 129 patients with NPC

with a mean age of 52.4±12.5 years; 75.2% of the patients were

<60 years of age. The male-to-female ratio was 2.91:1, and

approximately half of the patients had a primary school education.

The majority of the patients were diagnosed at stage III-IV disease

(82.9%) and were undergoing chemotherapy (60.5%). Severe

malnutrition (PG-SGA ≥9) was observed in 74.4% of the patients,

with a mean PG-SGA score of 15.98±9.3. Patients experienced an

average weight loss of 2.9 kg in 1 month, and 31.8% of the patients

lost >5% of their body weight (Table I).

| Table IDemographic and clinical

characteristics of the patients with NPC (n=129). |

Table I

Demographic and clinical

characteristics of the patients with NPC (n=129).

| Characteristic | Count, n (%) |

|---|

| Age, years | |

|

<60 | 97 (75.2) |

|

≥60 | 32 (24.8) |

|

Mean ±

SD | 52.4±12.5 |

| Sex | |

|

Male | 96 (74.4) |

|

Female | 33 (25,6) |

| Education

level | |

|

Illiteracy | 8 (6.2) |

|

Primary

school | 56 (43.4) |

|

Middle

school | 42 (32.6) |

|

High

school | 17 (13.2) |

|

Post-high

school | 6 (4.7) |

| Stage | |

|

I-II | 22 (17.1) |

|

III-IV | 107 (82.9) |

| Treatment | |

|

Chemotherapy | 78 (60.5) |

|

Radiotherary | 11 (8.5) |

|

Chemo-radiotherary | 28 (21.7) |

|

Other | 12 (9.3) |

| Feeding route | |

|

Oral

feeding | 112 (78.7) |

|

Tube

feeding | 17 (21.3) |

| PG-SGA | |

|

≤1 | 2 (1.6) |

|

2-3 | 3 (2.3) |

|

4-8 | 28 (21.7) |

|

≥9 | 96 (74.4) |

| Weight loss in 1

month | |

|

<5% | 88 (68.2) |

|

≥5% | 41 (31.8) |

The anthropometric and biochemical characteristics

of the patients are presented in Table II. The mean weight and height of

the patients were 55.2±10.3 kg and 161.3±7.7 cm, respectively (body

mass index, 21.1±3.3 kg/m²). The mean PG-SGA score was 15.98±9.3.

Patients lost an average of 2.9 kg in 1 month and 7.6 kg over a

period of 6 months. The mean white blood cell and lymphocyte counts

were 8.8x109/l and 1.7x109/l, respectively.

The mean hemoglobin level was 115.8 g/l.

| Table IIAnthropometric and biochemical

characteristics of nutrition. |

Table II

Anthropometric and biochemical

characteristics of nutrition.

| Parameter | Mean ± SD |

|---|

| Weight (kg) | 55.2±10.3 |

| Height (cm) | 161.3±7.7 |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 21.1±3.3 |

| PG-SGA | 15.98±9.3 |

| Weight loss in 1

month (kg) | 2.9±5.3 |

| Weight loss in 6

months (kg) | 7.6±8.4 |

| WBC count,

109/l | 8.8±9.3 |

| Lymphocyte count,

109/l | 1.7±2.7 |

| Hemoglobin,

g/l | 115.8±19.4 |

No significant differences were found in age, sex,

treatments, education, or tumor stage (I/II vs. III/IV) between the

malnourished and well-nourished patients (P>0.05). However, a

significant association was found between the nutritional status

(PG-SGA) and feeding route (P<0.05), with all patients with NPC

using feeding tubes being malnourished. The analysis of the

biochemical nutrition characteristics (white blood cell count,

lymphocyte count and hemoglobin) did not reveal any no significant

associations between these factors, nutritional status and QOL

(P>0.05) (Table III).

| Table IIINutritional status according to

PG-SGA and some related factors. |

Table III

Nutritional status according to

PG-SGA and some related factors.

| Characteristic | Well-nourished

patients (n=33), (%) | Malnourished

patients (n=96), (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | | | |

|

<60 | 28 (28.9) | 69 (71.1) | 0.17a |

|

≥60 | 5 (15.6) | 27 (84.4) | |

| Sex | | | |

|

Male | 27 (28.1) | 69 (71.9) | 0.36a |

|

Female | 6 (18.2) | 27 (81.8) | |

| Education

level | | | |

|

Illiteracy | 0 (0) | 8(100) | 0.21a |

|

Primary

school | 14(25) | 42(75) | |

|

Middle

school | 13(31) | 29(69) | |

|

High

school | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) | |

|

Post-high

school | 3(50) | 3(50) | |

| Stage | | | |

|

I-II | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | 0.999a |

|

III-IV | 27 (25.2) | 80 (74.8) | |

| Treatment | | | |

|

Chemotherapy | 26 (33.3) | 52 (66.7) | 0.09b |

|

Radiotherary | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | |

|

Chemo-radiotherary | 5 (17.9) | 23 (82.1) | |

|

Other | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Feeding route | | | |

|

Oral

feeding | 33 (29.5) | 79 (70.5) |

0.01b |

|

Tube

feeding | 0 (0) | 17(100) | |

| Weight loss in 1

month | | | |

|

<5% | 32 (36.4) | 56 (63.6) |

0.001b |

|

≥5% | 1 (2.4) | 40 (97.6) | |

| WBC count,

109/l | | | |

|

<4 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | 0.78b |

|

≥4 | 29 (26.4) | 81 (73.6) | |

| Lymphocyte count,

109/l | | | |

|

<1 | 11 (21.2) | 41 (78.8) | 0.41a |

|

≥1 | 22 (28.6) | 55 (71.4) | |

| Hemoglobin,

g/l | | | |

|

<120 | 16 (21.6) | 58 (78.4) | 0.31a |

|

≥120 | 17 (30.9) | 38 (69.1) | |

The univariate association between nutritional

status (PG-SGA scores) and QOL is presented in Table IV. The average scores for general

health, physical, role-based, social, cognitive and emotional

functioning decreased with malnutrition. Conversely, the average

score of fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, appetite loss and

constipation increased in the malnourished patients vs. the

well-nourished patients (P<0.05).

| Table IVAssociation between nutritional

status according to PG-SGA and quality of life. |

Table IV

Association between nutritional

status according to PG-SGA and quality of life.

| | Well-nourished

patients (n=33) | Malnourished

patients (n=96) | |

|---|

| Characteristic | Median | IQR | Median | IQR |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Global quality of

life | 77.8 | 50.0; 75.0 | 62.1 | 66.7; 95.8 | 0.001 |

| Functioning

scales | | | | | |

|

Physical | 97.2 | 80.0; 100 | 82.2 | 100; 100 | 0.001 |

|

Role | 91.9 | 50.0; 100 | 68.9 | 91.7; 100 | 0.001 |

|

Emotional | 87.6 | 66.7; 91.7 | 78.2 | 75.0; 100 | 0.009 |

|

Cognitive | 97.5 | 83.3; 100 | 86.8 | 100; 100 | 0.001 |

|

Social | 86.4 | 33.3; 100 | 63.7 | 66.7; 100 | 0.001 |

| Symptom

scale/items | | | | | |

|

Fatigue | 5.7 | 11.1; 44.4 | 31.4 | 0.0; 5.6 | 0.001 |

|

Nausea and

vomiting | 1.0 | 0.0; 33.3 | 16.7 | 0.0; 0.0 | 0.001 |

|

Pain | 8.1 | 0.0; 0.0 | 31.6 | 0.0; 0.50 | 0.001 |

|

Dyspnea | 2.0 | 0.0; 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.0; 0.0 | 0.500 |

|

Sleep

disturbance | 20.2 | 0.0; 33.3 | 28.8 | 0.0; 33.3 | 0.200 |

|

Appetite

loss | 9.1 | 33.3; 33.3 | 37.5 | 0.0; 16.7 | 0.001 |

|

Constipation | 1.0 | 0.0; 0.0 | 9.8 | 0.0; 0.0 | 0.023 |

|

Diarrhea | 2.0 | 0.0; 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0; 0.0 | 0.401 |

|

Financial

impact | 28.3 | 0.0; 50.0 | 39.2 | 0.0; 66.7 | 0.178 |

To investigate the factors influencing the QOL of

patients, a multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted.

Independent variables included demographic characteristics,

clinical features and nutritional status assessments that exhibited

statistically significant associations in prior analyses (e.g.,

feeding route, age, disease stage, percentage weight loss over 1

month and PG-SGA score). All QOL scale scores were used as

dependent variables. The PG-SGA score significantly predicted

overall QOL, explaining 39% of the variance (adjusted R²=0.39,

F=15.95, P=0.001). The PG-SGA score also significantly affected

different areas of QOL, including physical (37%), role (32%),

emotional (17%), cognitive (17%), social (31%), fatigue (56%),

nausea/vomiting (29%) and appetite loss (53%). Furthermore, the

PG-SGA score and age significantly predicted pain symptoms (40%

variance, adjusted R²=0.40, F=42.24, P=0.001), while PG-SGA score,

age and feeding route predicted constipation symptoms (31%

variance, adjusted R²=0.31, F=18.84, P=0.001) (see Table III for detailed data) (Table V).

| Table VResults of multivariate linear

regression analysis (enter) to predict scores on EORTC QLQ-C30

scales. |

Table V

Results of multivariate linear

regression analysis (enter) to predict scores on EORTC QLQ-C30

scales.

| | Unstandardized

coefficients | |

|---|

| Dependent

variable | Independent

variable | R2 | Adjusted

R2 | F | P-value | b | SE b | t | P-value |

|---|

| Global quality of

life | Model | 0.63 | 0.39 | 15.95 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | 0.01 | -1.18 | 0.24 | -4.98 | 0.01 |

| Physical | Model | 0.61 | 0.37 | 14.66 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | -1.31 | 0.28 | -4.64 | 0.01 |

| Role | Model | 0.56 | 0.32 | 11.32 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | 0.01 | -1.96 | 0.40 | -4.96 | 0.01 |

| Emotional | Model | 0.41 | 0.17 | 4.93 | 0.01 | | | | 0.01 |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | -0.96 | 0.28 | -3.38 | 0.01 |

| Cognitive | Model | 0.41 | 0.17 | 5.09 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | -1.01 | 0.27 | -3.77 | 0.01 |

| Social | Model | 0.56 | 0.31 | 11.14 | 0.01 | | | | 0.01 |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | -1.73 | 0.42 | -4.13 | 0.01 |

| Fatigue | Model | 0.75 | 0.56 | 31.35 | 0.01 | | | | 0.01 |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | 2.11 | 0.27 | 7.75 | 0.01 |

| Nausea and

vomiting | Model | 0.54 | 0.29 | 10.16 | 0.01 | | | | 0.01 |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | 1.83 | 0.30 | 6.15 | 0.01 |

| Pain | Model | 0.63 | 0.40 | 43.24 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | 1.98 | 0.22 | 9.13 | 0.01 |

| | Age | | | | | -0.41 | 0.16 | -2.57 | 0.01 |

| Appetite loss | Model | 0.73 | 0.53 | 27.46 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | 2.45 | 0.29 | 8.54 | 0.01 |

| Constipation | Model | 0.56 | 0.31 | 18.84 | 0.01 | | | | |

| | PG-SGA | | | | | 1.27 | 0.17 | 7.35 | 0.01 |

| | Age | | | | | -0.27 | 0.12 | -2.30 | 0.02 |

| | Feeding route | | | | | -14.90 | 4.70 | -3.17 | 0.01 |

Discussion

Malnutrition is common in patients with cancer, with

a prevalence ranging from 20 to 70% depending on the cancer type,

stage and clinical setting. This is often detected through

screening tools and results primarily from inadequate food intake

due to nutrition impact symptoms caused by the tumor itself, cancer

treatments, or disease-related complications (18-20).

The present cross-sectional study identified a high prevalence of

malnutrition among NPC patients at Can Tho Oncology Hospital. The

majority of the participants in the present study were experiencing

moderate to severe malnutrition and were in need of nutritional

assistance. Only 1.6% of the patients were well-nourished, while

74% of the patients had severe malnutrition (PG-SGA ≥9). These

results align with those of previous longitudinal studies by Wei

et al (11) (80.7% with

PG-SGA ≥9) and Miao et al (22) (82% requiring nutritional

intervention when weight loss ≥5%), although the present study

observed a lower intervention rate in the patients with NPC. This

discrepancy likely stems from the cross-sectional design pf the

present study, which captured patients at varying treatment stages,

unlike the studies by Wei et al (11) and Miao et al (22), which followed patients from the

beginning to the end of radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy.

Consequently, the present study sample likely included newly

treated patients with an improved nutritional status compared to

those nearing the end of treatment. Consistent with this, the study

by Wei et al (11)

demonstrated a significant increase in moderate to severe

malnutrition post-treatment (PG-SGA ≥9: 0.7% pre-treatment vs.

80.7% post-treatment). Likewise, herein, the mean cross-sectional

PG-SGA score (15.98±9.3) was higher than that of untreated patients

(7.50±5.97), but lower than that of patients receiving prolonged

radiotherapy for 4 weeks (17.75±5.56) and 6 weeks (20.50±6.76), as

reported in the study by Ding et al (23).

Malnutrition and weight loss are widespread in

patients with cancer, with reported weight loss in 20-80% of cases

and up to 60% in patients with NPC (23,24).

Excessive weight loss, often related to tumor characteristics and

treatment-related side-effects, exacerbates chemotherapy toxicity,

causes treatment interruption and is associated with poorer

treatment outcomes (25,26). Previous research has demonstrated

that severe weight loss affects the progression and recurrence of

NPC, and excessive weight loss can be considered a factor related

to survival (28). In the present

study, to minimize recall bias, patient weight data were

re-recorded from medical records documented 1 month prior. For

weight 6 months prior, recall was aided by using suggestive

questioning, cross-checking information via repetition and family

input and linking times to events. If the patient still could not

recall, their usual pre-illness weight was recorded. This approach

improves the accuracy of reported weight changes. The result was

that >30% of patients experienced ≥5% weight loss in 1 month,

with an average weight loss of 2.9±5.3 kg. In northern China, 56%

of patients experience similar weight loss at diagnosis, and the

average weight loss post-treatment is 6.9 kg (26). Benkhaled et al (29) found that 86% of patients with NPC

lost >10% of body weight by week 7 of treatment with

intensity-modulated radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

Such weight loss is linked to increased treatment toxicity,

interruptions and worse outcomes. Despite its clinical importance,

weight loss often goes undetected. Routine monitoring of weight and

nutritional status should be integrated into NPC management

pathways.

Timely nutritional support is crucial for patients

with NPC undergoing radiation therapy who are at risk of developing

malnutrition (6,18). Early nutritional intervention can

maintain nutritional status and improve treatment tolerance

(30). Diet and nutritional

education are continuous, emphasizing healthy cooking and small,

frequent meals. Oral nutritional supplements are used when diet and

education are insufficient (31).

In the case that oral nutritional supplements are inadequate,

enteral nutrition is initiated, and parenteral nutrition is

considered if enteral nutrition fails to meet nutritional needs

(32). The study Wang et al

(33) on the association of

nutritional counseling with the severity of radiation-induced oral

mucositis in patients with NPC demonstrated that nutritional

counseling was beneficial in reducing severe radiation-induced oral

mucositis and PG-SGA ≥4. On the other hand, radiotherapy or

chemo-radiotherapy lead to severe swallowing impairment in 50-70%

of patients, necessitating enteral nutrition during or immediately

post-treatment (34). In addition,

the present study also found an association between nutritional

status and feeding route (100% of patients with NPC need

nutritional intervention when feeding through a tube; P<0.05;

Table III). Enteral nutrition is

indicated in patients who have nutritional issues (unable to

tolerate at least 60% of their energy and protein needs orally for

7-14 days, even with education, medication and supplements)

(20,35) combined with dietary habits,

finances and inadequate nutritional knowledge that can further

complicate nutritional management. The truth is that at the

authors' research site, a common option for nasogastric tube

feeding is diluted white porridge, favored for its easy pump,

particularly among patients with NPC and other types of cancer.

However, its low nutritional content and the limited inclusion of

energy-dense foods often result in an inadequate daily energy

intake, heightening the risk of malnutrition. This highlights the

critical need for improved nutritional strategies, such as

integrating energy-rich foods into tube feeds and enhancing

nutritional education for both patients and caregivers, and

choosing locally available food sources to reduce costs. These

measures are essential for preventing malnutrition and promoting

improved health outcomes in patients with NPC.

The present study found that malnutrition

significantly reduced global and functional QOL scores, while

increasing symptom burden, particularly fatigue, nausea and

vomiting, pain, appetite loss and constipation (P<0.05), which

is similar to findings from previous studies (36,37).

Social and role function were found to be most affected by

radiotherapy, likely due to physical changes (e.g., ulcerated skin

and fatigue), emotional distress and body image concerns (38), resulting in social withdrawal

during the treatment. Symptoms of pain (mainly caused by

mucositis), fatigue, dry mouth and abnormal taste changes increased

during radiotherapy, which markedly affects the appetite and eating

habits of patients (30,31). In addition, almost all patients

experienced abnormal taste, decreased salivation and dry mouth,

which may be the main reasons for loss of appetite in patients with

NPC undergoing radiotherapy (37).

Fatigue is a common and distressing symptom experienced by patients

with cancer. The combination of anorexia and early satiety in

patients with cancer is associated with poorer overall health

perception, role function and increased fatigue. These prevalent

appetite disorders significantly impair the nutritional status and

QOL of patients, particularly when occurring in conjunction. This

can have profound effects on QOL and physical functioning (41,42).

Fatigue is further exacerbated by concurrent chemotherapy and

radiotherapy (43). In addition to

sociodemographic and tumor-related factors and disease-specific

symptoms, during treatment, tube feeding also has an impact on

weight, nutritional status and QOL. It has been demonstrated that

dietary counseling helps avoid weight loss and improves QOL.

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with head and neck

cancer who received nutritional counseling during radiation therapy

had a lower likelihood of weight loss, as well as a lower

likelihood of deterioration in symptoms, functional scores and

overall QOL (44,45). Early nutritional monitoring may

prevent malnutrition and improve the QOL of patients with cancer,

as suggested by a study on 312 patients that found an association

between early monitoring and improved outcomes (46). Therefore, nutritional monitoring

could be implemented during the early stages for NPC to improve its

outcomes.

Convenience sampling and study samples being

collected solely from one research center may bias results,

limiting generalizability to all NPC. In the present study, the

inclusion of all patients undergoing treatment limited the

evaluation of how individual treatment-related side-effects affect

nutrition and QOL. Future research is thus require to focus on

single chemotherapy or radiotherapy regimens for more specific

results. The present cross-sectional study cannot definitively

prove causality between nutritional status and quality of life.

Cross-sectional data limits our ability to determine if nutrition

affects quality of life, or vice versa, or if other factors

influence both. Future large cohort studies are warranted to

confirm associations and the direction of influence.

In conclusion, malnutrition is highly prevalent

among patients with NPC and is associated with significant weight

loss, symptom burden and a reduced QOL. The present study

highlights the need for early nutritional screening (e.g., PG-SGA),

individualized dietary counseling and optimized enteral feeding

using energy-dense, locally available foods. Enhancing caregiver

education and initiating timely interventions can prevent

nutritional decline, improve treatment tolerance, and ultimately

enhance the clinical outcomes and QOL of patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the

research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

All authors (KVV, HTTP, HTL, KND and ALTN)

contributed to the conception and design of the study. HTTP, HTL

and KND carried out the statistical analysis of the data. The

study's investigators included HTTP, HTL, KND, ALTN and KVV. HTTP

and HLT worked together to interpret the data. HTTP, ALTN and KND

contributed to the initial draft of the text. HTTP, HTL, ALTN and

KVV helped write, evaluate and revise the manuscript. HTTP and HTL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Hanoi Medical University (Hanoi, Vietnam) under

Decision no. NCS2024/GCN-HMUIRB, dated May 15, 2024. It is

understood that the study team provided the potential participants

with study-related information on the contents and objectives of

the study and sought their consent to participate by signing the

consent form.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bossi P, Chan AT, Licitra L, Trama A,

Orlandi E, Hui EP, Halámková J, Mattheis S, Baujat B, Hardillo J,

et al: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice

guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

32:452–465. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC): Global Cancer Observatory. IARC, Lyon, 2024.

https://gco.iarc.fr/. Accessed April 17,

2024.

|

|

4

|

Miao J, Xiao W, Wang L, Han F, Wu H, Deng

X, Guo X and Zhao C: The value of the prognostic nutritional index

(PNI) in predicting outcomes and guiding the treatment strategy of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients receiving

intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with or without

chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 143:1263–1273.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Deng J, He Y, Sun XS, Li JM, Xin MZ, Li

WQ, Li ZX, Nie S, Wang C, Li YZ, et al: Construction of a

comprehensive nutritional index and its correlation with quality of

life and survival in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma

undergoing IMRT: A prospective study. Oral Oncol. 98:62–68.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bischoff SC, Austin P, Boeykens K,

Chourdakis M, Cuerda C, Jonkers-Schuitema C, Lichota M, Nyulasi I,

Schneider SM, Stanga Z and Pironi L: ESPEN guideline on home

enteral nutrition. Clin Nutr. 39:5–22. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ji J, Jiang DD, Xu Z, Yang YQ, Qian KY and

Zhang MX: Continuous quality improvement of nutrition management

during radiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nurs

Open. 8:3261–3270. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Shu Z, Zeng Z, Yu B, Huang S, Hua Y, Jin

T, Tao C, Wang L, Cao C, Xu Z, et al: Nutritional status and its

association with radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with

nasopharyngeal carcinoma during radiotherapy: A prospective study.

Front Oncol. 10(594687)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hong JS, Wu LH, Su L, Zhang HR, Lv WL,

Zhang WJ and Tian J: Effect of chemoradiotherapy on nutrition

status of patients with nasopharyngeal cancer. Nutr Cancer.

68:63–69. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wan M, Zhang L, Chen C, Zhao D, Zheng B,

Xiao S, Liu W, Xu X, Wang Y, Zhuang B, et al: GLIM criteria-defined

malnutrition informs on survival of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

patients undergoing radiotherapy. Nutr Cancer. 74:2920–2929.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xueyan W, Ying L and Desheng H:

Nutritional status and its influencing factors of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma patients during chemoradiotherapy. Zhongliu Fangzhi

Yanjiu. 47:524–530. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

12

|

Zhuang B, Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhang T, Jin

SL, Gong L, Fang Y, Xiao S, Zheng B, Lu Q and Sun Y: Malnutrition

and its relationship with nutrition impact symptoms and quality of

life at the end of radiotherapy in patients with head and neck

cancer. Chinese Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 28:207–213.

2020.

|

|

13

|

Teixeira AC, Mariani MGC, Toniato TS,

Valente KP, Petarli GB, Pereira TSS and Guandalini VR: Scored

Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment: risk identification

and need for nutritional intervention in cancer patients at

hospital admission. Nutrición Clínica y Dietética Hospitalaria.

38:95–102. 2018.

|

|

14

|

Singh S, Raj E and Santhosh G:

Patient-generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA) as a

nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. IP Journal of

Nutrition, Metabolism and Health Science. 7:60–67. 2024.

|

|

15

|

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B,

Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman

SB and de Haes JC: The European Organization for Research and

treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use

in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst.

85:365–376. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

EORTC-Quality of Life: EORTC Quality of

Life Group. Giving a voice to patients. https://qol.eortc.org/.

|

|

17

|

Bauer J, Capra S and Ferguson M: Use of

the scored patient-generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA)

as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin

Nutr. 56:779–785. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Rogers SN, Semple C, Babb M and Humphris

G: Quality of life considerations in head and neck cancer: United

Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 130

(Suppl 2):S49–S52. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Arends J: Malnutrition in cancer patients:

Causes, consequences and treatment options. Eur J Surg Oncol.

50(107074)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V,

Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Fearon K, Hütterer E, Isenring

E, Kaasa S, et al: ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer

patients. Clin Nutr. 36:11–48. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Marshall KM, Loeliger J, Nolte L, Kelaart

A and Kiss NK: Prevalence of malnutrition and impact on clinical

outcomes in cancer services: A comparison of two time points. Clin

Nutr. 38:644–651. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Miao J, Wang L, Ong EHW, Hu C, Lin S, Chen

X, Chen Y, Zhong Y, Jin F, Lin Q, et al: Effects of induction

chemotherapy on nutrition status in locally advanced nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: A multicentre prospective study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia

Muscle. 14:815–825. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ding H, Dou S, Ling Y, Zhu G, Wang Q, Wu Y

and Qian Y: Longitudinal body composition changes and the

importance of fat-free mass index in locally advanced

nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients undergoing concurrent

chemoradiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 17:1125–1131.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Bozzetti F, Gavazzi C, Miceli R, Rossi N,

Mariani L, Cozzaglio L, Bonfanti G and Piacenza :

Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in malnourished,

gastrointestinal cancer patients: A randomized, clinical trial. J

Parenter Enteral Nutr. 24:7–14. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Langius JAE, van Dijk AM, Doornaert P,

Kruizenga HM, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Weijs PJ and Verdonck-de

Leeuw IM: More than 10% weight loss in head and neck cancer

patients during radiotherapy is independently associated with

deterioration in quality of life. Nutr Cancer. 65:76–83.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Qiu C, Yang N, Tian G and Liu H: Weight

loss during radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A

prospective study from Northern China. Nutr Cancer. 63:873–879.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ng K, Leung SK, Johnson PJ and Woo J:

Nutritional consequences of radiotherapy in nasopharynx cancer

patients. Nutr Cancer. 49:156–161. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ou Q, Cui C, Zeng X, Dong A, Wei X, Chen

M, Liu L, Zhao Y, Li H and Lin W: Grading and prognosis of weight

loss before and after treatment with optimal cutoff values in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nutrition. 78(110943)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Benkhaled S, Dragan T, Beauvois S, De

Caluwé A and Van Gestel D: Weight loss in nasopharyngeal cancer is

mainly associated with pre-treatment dental extraction, a European

Single-Center Experience. J Cancer Sci Ther. 11(3)2019.

|

|

30

|

Meng L, Wei J, Ji R, Wang B, Xu X, Xin Y

and Jiang X: Effect of early nutrition intervention on advanced

nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients receiving chemoradiotherapy. J

Cancer. 10:3650–3656. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Langius JAE, Zandbergen MC, Eerenstein

SEJ, van Tulder MW, Leemans CR, Kramer MHH and Weijs PJ: Effect of

nutritional interventions on nutritional status, quality of life

and mortality in patients with head and neck cancer receiving

(chemo)radiotherapy: A systematic review. Clin Nutr. 32:671–678.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Fan X, Cui H and Liu S: Summary of the

best evidence for nutritional support programs in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma patients undergoing radiotherapy. Front Nutr.

11(1413117)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang SA, Zhu YH, Liu WJ, Haq IU, Gu JY, Qi

L, Yang M and Yang J: Association of nutritional counselling with

the severity of radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with

nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study. Nutrition Clinique

et Métabolisme. 38:244–250. 2024.

|

|

34

|

Karmakar-Mangaj S, Laskar SG and Talapatra

K: Choosing optimal feeding method in head-neck cancer patients

receiving radiation: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus

nasogastric tube-is it pertinent? J Curr Oncol. 6:57–60. 2023.

|

|

35

|

Bechtold ML, Brown PM, Escuro A, Grenda B,

Johnston T, Kozeniecki M, Limketkai BN, Nelson KK, Powers J, Ronan

A, et al: When is enteral nutrition indicated? JPEN J Parenter

Enteral Nutr. 46:1470–1496. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Löser A, Avanesov M, Thieme A, Gargioni E,

Baehr A, Hintelmann K, Tribius S, Krüll A and Petersen C:

Nutritional status impacts quality of life in head and neck cancer

patients undergoing (Chemo)Radiotherapy: Results from the

prospective HEADNUT trial. Nutr Cancer. 74:2887–2895.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kan Y, Yang S, Wu X, Wang S, Li X, Zhang

F, Wang P and Zhao J: The quality of life in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma radiotherapy: A longitudinal study. Asia Pac J Oncol

Nurs. 10(100251)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Li JB, Guo SS, Tang LQ, Guo L, Mo HY, Chen

QY and Mai HQ: Longitudinal trend of health-related quality of life

during concurrent chemoradiotherapy and survival in patients with

stage II-IVb nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Front Oncol.

10(579292)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hua X, Chen LM, Zhu Q, Hu W, Lin C, Long

ZQ, Wen W, Sun XQ, Lu ZJ, Chen QY, et al: Efficacy of

controlled-release oxycodone for reducing pain due to oral

mucositis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with

concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A prospective clinical trial. Support

Care Cancer. 27:3759–3767. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chan YW, Chow VLY and Wei WI: Quality of

life of patients after salvage nasopharyngectomy for recurrent

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 118:3710–3718. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Stone P, Candelmi DE, Kandola K, Montero

L, Smetham D, Suleman S, Fernando A and Rojí R: Management of

fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol.

24:93–107. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Galindo DE, Vidal-Casariego A,

Calleja-Fernández A, Hernández-Moreno A, Pintor de la Maza B,

Pedraza-Lorenzo M, Rodríguez-García MA, Ávila-Turcios DM,

Alejo-Ramos M, Villar-Taibo R, et al: Appetite disorders in cancer

patients: Impact on nutritional status and quality of life.

Appetite. 114:23–27. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chen LM, Yang QL, Duan YY, Huan XZ, He Y,

Wang C, Fan YY, Cai YC, Li JM, Chen LP and Qin HY: Multidimensional

fatigue in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma receiving

concurrent chemoradiotherapy: Incidence, severity, and risk

factors. Support Care Cancer. 29:5009–5019. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Vidal PM and

Camilo ME: Impact of nutrition on outcome: A prospective randomized

controlled trial in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing

radiotherapy. Head Neck. 27:659–668. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Isenring EA, Capra S and Bauer JD:

Nutrition intervention is beneficial in oncology outpatients

receiving radiotherapy to the gastrointestinal or head and neck

area. Br J Cancer. 91:447–452. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhang YH, Xie FY, Chen YW, Wang HX, Tian

WX, Sun WG and Wu J: Evaluating the nutritional status of oncology

patients and its association with quality of life. Biomed Environ

Sci. 31:637–644. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|