Gynecological cancers are common, and ovarian cancer

(OC) is the deadliest due to difficulties diagnosing this disease

in the early stages. Specifically, 70–90% of patients with OC are

diagnosed at an advanced stage, indicating that the cancer has

already spread (1). In 2018,

there were ~300,000 reported cases of OC worldwide, with ~18,000

fatalities (2). Epithelial

ovarian tumors have the highest incidence, whereas germ cell and

sex cord-stromal OC account for ~5% of cases (3). At present, ovarian epithelial tumors

are classified into four subtypes with identical pathologies:

Serous, endometrioid, mucinous and clear cell (3). These tumors can be classified as

either type I or II based on the malignancy. Type II tumors are

more aggressive and have poorer survival outcomes compared with

type I (4). High-grade serous

cancers, a subtype of type II, are the most frequent and account

for 80% of OC-related deaths (5,6).

Platinum-based chemotherapy and cytoreductive surgery are the

primary clinical treatments for OC. However, this treatment

strategy is less effective for advanced OC as the lesions are

difficult to remove completely, and advanced OC tends to be

drug-resistant. Therefore, early diagnosis and targeted medicine

are crucial for the effective treatment of OC.

At present, tissue biopsy is the most common method

for cancer diagnosis, but it is invasive and time-consuming.

Additionally, biopsies carry risks such as tumor implantation and

metastasis, making them unsuitable for long-term monitoring

(7,8). Thus, novel and sensitive biomarkers

are needed for the early and quick diagnosis of cancer. All cell

types secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly exosomes,

which transport various cargoes such as lipids, proteins, DNA and

most non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including circular RNA (circRNA),

long ncRNA (lncRNA) and microRNA (miRNA). Exosomes can exchange

signals and materials between different cells by carrying and

transporting these cargoes (9).

Given that exosomes collect, transport and release cargo, they can

be considered new targets in OC diagnosis and treatment.

Cancer is a genetic disease primarily caused by

mutations in the non-coding genome (10). Previous genomic studies have

indicated that the non-coding regions of RNA are extensively

transcribed (11). The Human

Genome Project has demonstrated that 1.5% of the human genome

consists of genes that encode proteins; the rest are transcribed

without translation into proteins (12,13). The two subtypes of ncRNAs are

distinguished based on their size: lncRNA and small ncRNA (sncRNA).

sncRNAs can be further classified into miRNA, transfer RNA,

PIWI-interacting RNA and small nucleolar RNA (14). Particularly, miRNAs inhibit

protein translation and promote messenger RNA (mRNA) cleavage to

suppress gene expression (15).

Furthermore, miRNAs can migrate into biological fluids (16) and ~10% of circulating miRNAs are

secreted via exosomes (17,18). lncRNAs, which are transcripts of

>200 nucleotides with potential non-coding functions, exhibit

tissue- or cancer-type specificity (19). Serving as readouts of running

cellular programs or signals of certain cellular states, lncRNAs

can be used to distinguish various cellular pathologies, provide a

predictive value or even used to choose appropriate therapeutics

for patients with cancer (20).

For instance, the circulating lncRNA-GC1, derived from EVs, serves

as an early indicator of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (neoCT)

effectiveness and is correlated with improved survival outcomes in

patients with gastric cancer undergoing neoCT treatment (21). Serum exosomal lncRNA-UCA1,

initially discovered in human bladder cancer, can serve as a

potential non-invasive biomarker for the diagnosis of bladder

cancer. circRNAs are closed RNAs without 5′ or 3′ ends and are

classified into natural or synthetic circRNAs (22). In a number of tissues, endogenous

circRNAs are involved in various biological functions such as gene

transcription, protein translation, cell division, immune system

dysregulation and tumorigenesis (23).

In summary, ncRNAs in exosomes are involved in

numerous biological functions, including gene expression and

disease development, making them valuable diagnostic tools in

clinical settings. The present review summarizes the features,

isolation techniques, functions and mechanisms of exosomes and

exosomal ncRNAs and predicts their potential in diagnosing and

prognosing OC.

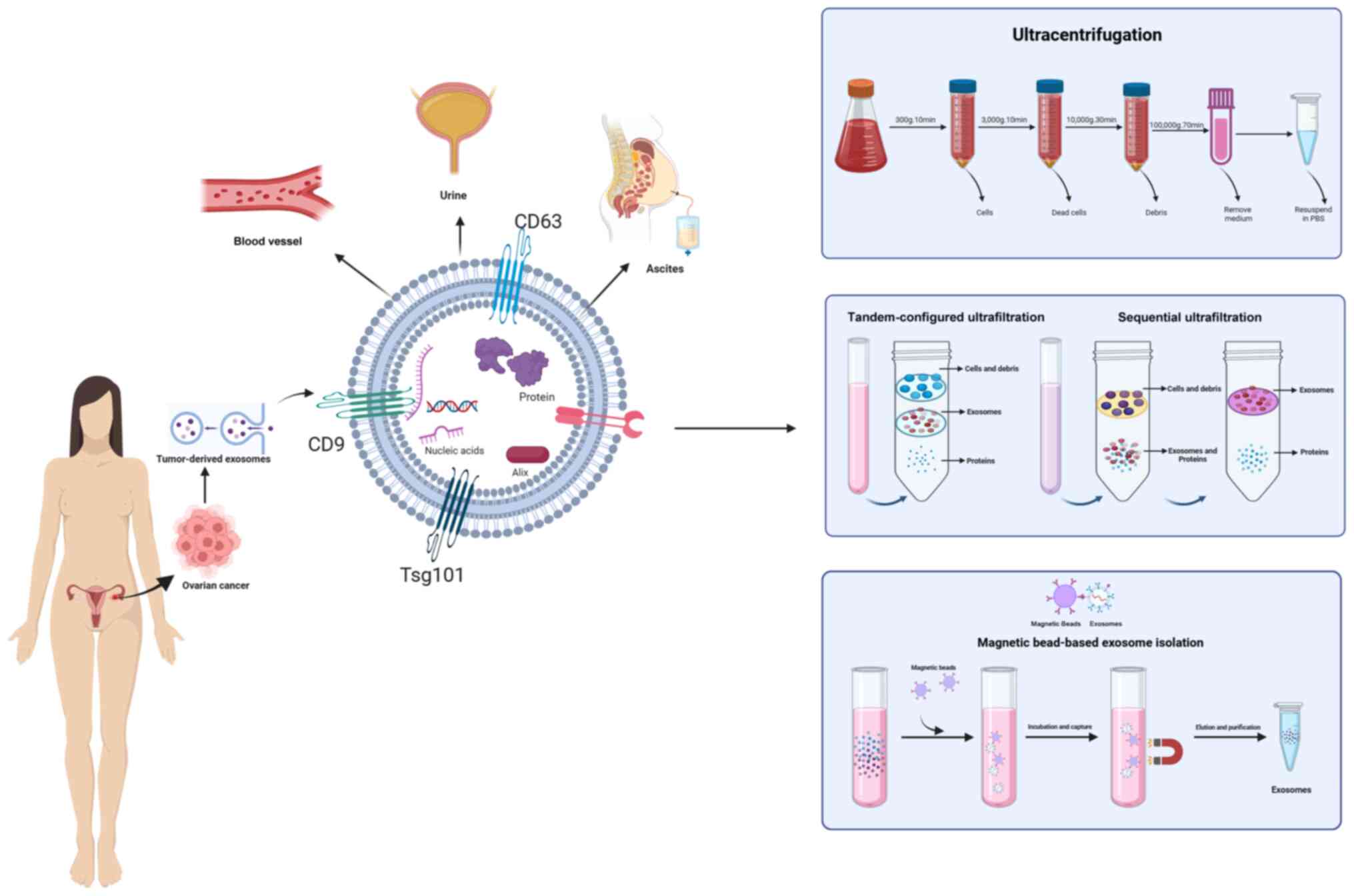

Exosomes can be isolated using several methods, such

as ultrafiltration, size exclusion chromatography and density

gradient ultracentrifugation. Most cells secrete EVs, first

reported in 1985 (24). Exosomes

are nanoparticles that facilitate cellular waste disposal into the

extracellular environment. Increasing evidence suggests that

exosomes participate in various physiological and disease-related

processes, serving as biomarkers for several diseases (25–27). Extracting exosomes is crucial for

understanding their characteristics and functions. Numerous

techniques have been developed to separate exosomes based on their

main features, such as surface proteins, size, shape and density

(Fig. 1 and Table I).

Tissue biopsy is currently the gold standard for

cancer diagnosis, but it has limitations. First, tissue biopsy only

provides a snapshot of the tumor tissue, possibly neglecting tumor

heterogeneity and the different processes and changes that occur

during interactions with the immune system and other systems.

Additionally, tissue biopsy requires time to detect cancer, thus

delaying further therapeutic decisions. Tissue biopsy also cannot

show whether a patient responds favorably to current treatment and

is impractical for frequent sample collection (28). With the development of science and

technology, liquid biopsy is regarded as a non-invasive, real-time,

tumor-specific method that can track the advancement and recurrence

of cancer and the response to treatment interventions (29). Assessing serum from patients for

human epididymis protein 4, carbohydrate antigen-125 (CA-125) and

p53 levels is one way to detect and monitor OC progression or the

response to treatment (30).

However, these methods lacked specificity and sensitivity.

Therefore, a novel approach is required to accurately predict,

diagnose and determine the prognosis of OC (14). Exosomes are among the most

important biological components of liquid biopsy and possess a

number of advantages over tumor-educated platelets (TEPs),

circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs).

For instance, exosomes display exceptional stability within

biological fluids, including plasma and urine (31). The immune conditions of the

patient and different treatments can affect the RNA content of

TEPs. Additionally, both CTCs and ctDNA have brief half-lives and

are unstable, making sample collection challenging (32,33).

The term ‘liquid biopsy’ was first proposed in 2010

when researchers used CTCs to enhance breast cancer treatment and

prognosis (34). Initially, the

use of liquid biopsies focused on identifying CTCs and ctDNA in

patients with cancer. However, components of CTCs and ctDNA are

scarce in circulating biofluids, making them inappropriate for use

as clinical diagnostic biomarkers. Conversely, other molecules

secreted from cancer cells (such as ncRNAs) are more abundant than

CTCs or ctDNA and are relatively stable in circulating biofluids

(35). In recent decades,

exosomes have been used to develop novel biomarkers, a primary goal

of translational research (26,27). Exosomes are abundant and widely

distributed in human bodily fluids, such as serum, saliva and

urine. Exosomes carry various biomolecules, including proteins,

lipids and nucleic acids, from their parent cells, making them

accessible and potential biomarkers for tumor diagnosis, prognosis

and monitoring (36).

Additionally, exosomes are crucial for tumor development, spread

and therapy resistance, particularly chemotherapy, by transferring

their contents (37). ncRNAs are

pivotal exosome components; exosomal ncRNAs, including miRNAs,

lncRNAs and circRNAs are specific biomarkers for cancer diagnosis,

prognosis, prediction and monitoring (38). With the advancements in

transcriptomic analysis, ncRNAs have been shown to affect and

participate in various aspects of OC (39), including cancer progression,

metastasis and drug resistance (40).

In general, miRISCs induce translational inhibition

by binding to target mRNA. Then, P-body (GW182) family proteins

binding to AGO are recruited, providing a scaffold to recruit

downstream effector proteins such as poly(A)-deadenylases, PAN2/3,

and the glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase transcriptional

effector, carbon catabolite repression 4-negative on TATA-less

(52). Ultimately, the

chromatin-binding exonuclease, 5′-3′ exoribonuclease 1, degrades

the decapped mRNA (53,54). While most research has focused on

miRNAs that prevent target gene expression, other studies have

revealed that certain miRNAs can increase gene expression. For

instance, AGO2 and FMR1 autosomal homolog 1 are linked to certain

miRNAs, such as let-7, which stimulate translation during cell

cycle arrest (55).

miRNAs are divided into two main categories based on

their target genes: Tumor suppressor miRNAs and oncogenic miRNAs

(56). Tumor suppressor miRNAs

silence uncontrolled genetic proliferation, thereby preventing

cancer progression; tumorigenesis may occur when these miRNAs are

downregulated in tumor cells (57). Oncogenic miRNAs increase oncogene

expression and promote tumor development; tumorigenesis may occur

when these miRNAs are upregulated in tumor cells (58).

Various miRNAs are associated with OC progression,

diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring, which is summarized in

Table II. miR-34a, which

inhibits nearly 700 target genes, is a classical tumor suppressor

(58). miR-34a can also encode a

microprotein, termed miRPEP133, through an open reading frame (ORF)

in the pri-miRNA-34a. A study overexpressed miRPEP133 in the SKOV3

OC cell line, finding that it may increase apoptosis and limit cell

survival (59). Numerous studies

have assessed the expression of miR-1246 in various cancer cell

lines using various miRNA profiling techniques. The upregulation of

miR-1246 has been noted in lung and liver tissues. Compared with

normal colonic mucosa, the marked upregulation of miR-1246 in

colorectal cancer tissues bolsters its status as a promising

biomarker and suggests a role in the pathogenic processes of

colorectal cancer (60–62). OC exosomes show significant levels

of oncogenic miR-1246 expression (63). Based on data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas, OC cells can be sensitized to paclitaxel in patients

with OC receiving anti-miR-1246 therapy and exhibiting caveolin 1

(Cav1) upregulation. Moreover, miR-1246 inhibits Cav1 by acting on

platelet derived growth factor receptor β receptor, preventing cell

proliferation (64). miR-221

plays both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive roles in human cancer.

miR-221 is capable of suppressing the proliferation of lung cancer

cells, potentially through S phase arrest (65). miR-221 is upregulated in OC

tissues compared with matched normal tissues. Furthermore, patients

with high miR-221 expression have shorter overall survival (OS) and

disease-free survival times than those with low expression. miR-221

targets protease activating factor 1 (APAF1), which induces

apoptosis via gene inhibitors (66). Expressing higher levels of APAF1

by transfecting OC cell lines with miR-221 inhibitors prevents the

proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells in

vitro (66). According to a

previous study, miR-27b-5p expression is lower in OC cell lines and

tissues than in surrounding tissues. Furthermore, the OS rate was

lower in patients with low miRNA-27b-5p expression. This study also

verified that C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), which is

involved in OC malignancy, is a target gene of miR-27b-5p.

Additionally, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and

immunoblotting analyses showed that the CXCL1 mRNA and protein

levels were decreased in A2780 and OVCAR3 cells following

miR-27b-5p overexpression (67).

In total, four molecular subtypes of OC,

characterized by low overall survival rates, have been identified

through extensive transcriptional profiling of cancer tissues:

Immunoreactive, differentiated, proliferative and mesenchymal

(68,69). To further investigate the

different patterns of immune cell infiltration in OC, Liu et

al (70) utilized the

expression deconvolution algorithm, CIBERSORT, to confirm the

distinct infiltration of immune cells in the four subtypes.

Concentrated in plasma cells, the mesenchymal subtype of high-grade

serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) can induce the mesenchymal features

of OC by releasing exosomes. Exosomal miRNA profiling revealed that

plasma cell-derived miR-330-3p is an essential modulator of

mesenchymal identity in OC. miR-330-3p increases the transcription

of junctional adhesion molecule 2 through enhancer-induced gene

activation pathways (71).

The promoter regions of lncRNA genes are conserved,

similar to those of protein-coding genes, and the production of

lncRNAs controlled by these genes is tissue-specific (77). At present, different methods are

used to classify lncRNAs, mainly depending on their function,

interactions with protein-coding genes, structure, sequence and

metabolism (78). lncRNAs can be

categorized into four functional groups: Skeleton, guide, signal

and bait molecules. In terms of interactions with protein-coding

genes, lncRNAs fall into four categories: Overlapping,

bidirectional, intron and cis-antisense (79). lncRNAs are crucial for various

biological processes, including: i) Engaging with chromatin

complexes to support the regulation of epigenetic genes; ii) acting

as proteins or multiprotein compound modulators; iii) influencing

transcriptional expression by binding proteins linked to DNA/RNA;

iv) controlling the stability of DNA by forming triple helices and

R-loops; and v) assisting in the creation of higher-order chromatin

structures (80).

At present, RNAs are the main targets for

therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. ncRNAs, for instance, show

notable variety in nucleotide length and can form different

structures when interacting with proteins, DNA and other

substances. Notably, lncRNAs are more likely to form intricate

secondary or tertiary structures due to their long nucleotide

sequences. These structures, similar to enzymes, fulfill biological

functions through their unique domains that show reproducibility

and conservatism (81). The

function of a number of proteins is determined by their distinct

structural domains. However, current understanding of the

structural domains that determine their functionality and define

their interactome is lacking. Recently, various methods have been

developed to assess the secondary structure of lncRNAs (82). These techniques are roughly

divided into two types: Experimental and computational methods.

Experimental techniques include enzymatic footprinting, chemical

probing, nuclear magnetic resonance, small-angle scattering, atomic

force microscopy and cryo-electron microscopy (81).

Various mechanisms have demonstrated that lncRNAs

are involved in cancer progression. In the clinic, most OC cases

have abdominal cavity metastases. Thus, the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway serves a crucial

role in tumor cell dissemination. The mechanisms by which lncRNAs

mediate EMT in OC are diverse (83). For instance, through

bioinformatics analysis, a previous study identified lncRNA

pro-transition associated RNA as a lncRNA-mediated competing

endogenous RNA (ceRNA) that competitively inhibits miR-101 to

modulate the expression of zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1

(84). A number of patients with

OC develop carboplatin resistance. Chemotherapy-resistant

strategies often involve multipotent mesenchymal stem cells or an

increased EMT phenotype in cancer (85,86). In a clinical study, which included

134 primary OC cases (63 treated with carboplatin, 55 treated with

cisplatin and 16 without therapy), expression of the lncRNA HOX

transcript antisense RNA (HOTAIR) and the corresponding DNA

methylation were detected. The research showed that patients with

high HOTAIR expression receiving carboplatin had significantly

lower survival rates, whereas this effect was not observed in

patients who did not receive carboplatin (87). To reduce transcription, HOTAIR

attracts polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to certain polycomb

group target (PCGT) genes, particularly in embryonic fibroblasts

(88). During differentiation,

PCGTs essential for the identity of specialized cells are

derepressed (89,90). However, promoters of these stem

cell PCGTs are methylated and repressed in cancer (91). In several cancer types, high

HOTAIR expression levels are strongly associated with metastasis,

cancer invasiveness and poor prognosis (88,92).

The OC process is aided by ferroptosis, an

iron-dependent type of cell death. One of the predominant methods

used in cancer therapy involves triggering apoptosis to eradicate

malignant cells. lncRNAs can regulate ferroptosis, a process that

can trigger apoptosis and may therefore be beneficial in cancer

treatment (93). A recent study

found that lncRNA CACNA1G antisense RNA 1 promotes ferritin heavy

chain 1 synthesis by reducing ferroptosis through insulin like

growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 1-mediated N6-methyladenosine

(m6A) modification, which enhances the migration and division of OC

cells (94). Additionally,

another study showed that lncRNA ADAMTS9 antisense RNA 1 sponges

miR-587 in OC, preventing ferroptosis and enhancing the expression

of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (95).

Numerous studies have shown that lncRNAs can control

the expression of tumor suppressor genes to either promote or

prevent new tumor growth. Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor

antisense RNA1 (LIFR-AS1), a tumor suppressor gene in colorectal

cancer, was found to be downregulated in serous ovarian carcinoma

(SOC) in a previous study. Generally, patients with SOC and low

LIFR-AS1 expression had a poor prognosis. Low LIFR-AS1 expression

was also associated with tumor size, clinical stage, lymph node

metastasis and distant metastasis (96). LIFR-AS1 upregulation enhances the

production of cleaved caspase-3 and E-cadherin, suppressing the

malignant activities of SOC cells, including their migration,

invasion and proliferation (96).

lncRNAs can also repress tumor progression by regulating oncogene

expression. For instance, long intergenic non-protein-coding RNA

857 (LINC00857), which inactivates the Hippo signaling pathway, can

accelerate OC progression by regulating yes-associated protein 1

(YAP1), which acts as an oncogene in OC. LINC00857 competitively

binds to miR-486-5p to regulate YAP1 expression, which elevates OC

progression (97). A summary of

the oncogenic lncRNAs in critical signaling pathways in OC is

detailed in Table III.

When a tumor suppressor gene exon is spliced,

circRNAs join in a different order from their genomic sequences.

circRNAs were first described in 1976 (98). In 2015, high-throughput

technologies were used to ascertain that circRNAs were two times

more abundant in EVs than in parental cells (99). Premature mRNAs, which often do not

encode proteins, can be alternatively spliced to become circRNAs,

which are ncRNAs. circRNAs are more stable than other linear RNAs

as they form covalently closed loops without 5′- or 3′-end features

(100). This structure makes

circRNAs resistant to degradation by classical RNA pathways,

leading to their exocytosis from cells (101–103). circRNAs were initially thought

to be non-functional byproducts of splicing mistakes. However, as

high-throughput technologies and bioinformatics research progress,

there is a growing body of evidence indicating that they exist

widely in eukaryotic cells, where they regulate miRNAs and proteins

to participate in various biological processes (104,105). Moreover, these circRNAs have

been found to be stable and extremely conservative (99,106). circRNA expression in tumor

tissues differs from that in normal tissues, indicating their

involvement in tumorigenesis (107). circRNAs originate from various

genomic regions, including intergenic, intronic, antisense and

untranslated regions, and are categorized into three groups based

on the region from which they are derived: Intronic, exon-intron

and exonic (108). circRNAs have

three major biological functions (109), including: i) Controlling the

expression of target genes by competitively binding to miRNAs,

similar to lncRNAs, acting as sponges for miRNAs or ceRNAs

(110); ii) controlling the

transcription, splicing, translation and interaction of genes with

RNA-binding proteins to control the expression of genes (111); and iii) serving a role in

polysomes, initiating putative ORFs and the AUG codon, and encoding

regulatory peptides (112).

circRNAs are involved in the development, metastasis

and carcinogenesis of numerous human disorders (113,114). For instance, in

platinum-resistant OC, the expression of circPLPP4 is notably

elevated. Functionally, circPLPP4 operates as a molecular sponge

for miR-136, effectively sequestering it. By doing so, circPLPP4

competitively increases the expression of PIK3R1, thereby

contributing to resistance against cisplatin (115). Hsa_circ_0004712 exhibits

abundant regulation in both OC tissues and cellular models, and

functions by specifically targeting and reducing the expression of

miR-331-3p. FZD4 was identified as a downstream target of

miR-331-3p, experiencing repression when miR-331-3p levels were

high, yet its expression was notably enhanced in the presence of

hsa_circ_0004712, illustrating a regulatory axis between the

circular RNA, microRNA and target gene (116). A summary of the oncogenic

circRNAs in critical signaling pathways in OC is detailed in

Table IV.

The majority of the tumor mass consists of the TME,

which is mostly composed of tumor stroma (117). Stem cells, fibroblasts,

endothelial cells, immune cells and numerous other cells that

produce growth factors and cytokines are found in the TME (118). EVs are essential for

communication between stromal and tumor cells in both nearby and

distant microenvironments. EVs support tumor growth and establish a

complex microenvironment called the pre-metastatic niche (PMN). The

PMN has been primed by the primary tumor in distant organs or

regions free of tumors, anticipating metastasis spread (119). The characteristic features of

the PMN include extracellular matrix remodeling and deposition,

lymphangiogenesis, vascular permeability, angiogenesis and

immunological suppression (120).

Among the deadliest gynecological cancers, OC

frequently results in peritoneal metastases, leading to higher

recurrence rates and resistance to standard platinum-based

treatments, which can result in a poor prognosis (121,122). Metastatic cancer cells spread to

secondary sites, where they find a supportive TME owing to the

biological components of the host. For instance, OC-generated EVs

target YAP1, a key effector of the Hippo pathway. This interaction

reduces the nuclear YAP1/transcriptional co-activator with

PDZ-binding motif protein ratio and increases CXCL1 production by

stromal fibroblasts. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as CXCL1,

play a crucial role in promoting tumor development and metastasis

(123). This finding indicates

that pro-inflammatory CXCL1 is extensively expressed in the TME of

ovarian malignancies and has oncogenic-promoting properties

(123). Exosomes derived from OC

that contain activating transcription factor 2 and

metastasis-associated protein 1 may enhance angiogenesis (124). Tumor-secreted EVs (TEVs) are

taken up by macrophages and lymphocytes in animal models,

significantly decreasing the cross-presentation of tumor antigens

from dendritic cells, which in turn affects CD8+ T cell

activity (125). Another study

demonstrated that TEVs expressing programmed cell death ligand 1

reduced the number of CD8+ T cells that invaded the

lymph nodes (126).

Phosphatidylserine, which impedes T-cell activation by obstructing

intracellular signaling cascades, is present in some exosomes from

OC (127). To counteract the

immunosuppressive effects, normal cells, particularly immune cells,

also produce EVs. These findings highlight the critical role of EVs

in controlling the immune system. For instance, exosomes release

cytokines, respond to specific antigens and mitogens, stimulate or

inhibit B cell antibody production and directly kill target cells

(128). Cytotoxic EVs are also

released by natural killer (NK) cells. Fais et al (129) provided the first evidence that

NK-derived EVs are lethal to cancer cells. It was shown that NK

cells obtained from healthy donors, both in the resting and active

states, were capable of killing a range of cancer cell lines and

extending their cytotoxicity to resting immune cells but not to

activated cells. Another study has reported that NK-derived EVs

exhibit characteristic protein markers that are typical of NK

cells, showing a propensity to be selectively internalized by SKOV3

cells, and demonstrating cytotoxic effects against OC cells

(130). FasL and perforin are

expressed in NK-derived EVs. These proteins can induce target cell

demise via two pathways: i) A conventional ligand/receptor

engagement between the membrane-bound FasL of NK-derived EVs and

the Fas receptor on the surface of the target cell and; ii) an

atypical cytotoxic mechanism initiated upon the uptake of exosomes

by the target cells, potentially involving the intracellular

release of effector molecules, such as perforin (129).

EVs have become important mediators of immunological

evasion and repression of complex interactions between tumors and

normal cells. TEVs disrupt immunological functions and diminish the

effectiveness of immunotherapy. Normal cells, particularly immune

cells, release EVs to counteract these effects.

Current clinical screening methods for OC include

imaging and blood testing. Imaging techniques comprise positron

emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, computed

tomography and ultrasound screening. Serum tests primarily measure

CA-125 and cancer antigen 19-9 (131). Common diagnostic methods for OC,

such as pelvic examination, ultrasound screening and CA-125

measurement, lack sensitivity and specificity (132), and only 50–60% of individuals

diagnosed with stage I or II OC exhibit elevated CA-125 levels

(133). Therefore, the discovery

of new biomarkers is urgently needed to improve detection rates.

Patients with OC show specific miRNA expression patterns in

exosomes (134). Thus, these

patterns may serve as potential biomarkers for various cancer

types, including OC. For instance, ~95 exosomal miRNAs are

differentially expressed in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer

(EOC) and healthy donors (135).

Individuals with EOC exhibit significantly lower levels of

miR-320d, miR-4479 and miR-6763-5p than healthy donors. According

to a study that used receiver operating characteristic curves to

assess the diagnostic efficiency of exosomal miRNAs, these three

exosomal miRNAs have diagnostic potential (135). A study also reported that

exosomal miR-200b and CA-125, which are used for EOC screening, are

associated with OS. According to this study, miR-200b influences

cell proliferation and apoptosis. Furthermore, exosomal miR-200b

can distinguish patients with EOC from healthy individuals with a

64% sensitivity and 86% specificity (136). Additionally, the level of serum

exosomal miR-34a can be used to differentiate patients with

early-stage and advanced-stage OC, suggesting that miR-34 is a

potential biomarker for OC (137).

Exosomal ncRNAs show promise as potential novel

diagnostic biomarkers for OC and are currently in the preclinical

stage of development. Numerous prior studies have demonstrated that

exosomal ncRNAs can function as prognostic biomarkers for OC. For

instance, exosomal metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma

transcript 1 (MALAT1) has been linked to more malignant tendencies

and a late International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

stage of EOC. Based on nomogram modeling and multivariate survival

analysis, serum exosomal MALAT1 may be a potential predictive

biomarker for EOC (138). Zhang

et al (139) demonstrated

that OS was associated with high levels of exosomal miR-200b.

Additionally, circFoxp1 is identified as an independent factor that

can predict survival and disease recurrence in individuals with

EOC, according to the International Union of Obstetrics and

Gynecology (140). Unlike other

human cancer types, OC preferably invades the peritoneal cavity,

with a particular potency at interacting with different viscera

inside the compartment (121).

The exosomes of the primary ovarian tumor could prime the distant

TME for an expedited metastatic invasion. Within the TME, exosomes

control intercellular communication between tumor cells and the

normal stroma, cancer-associated fibroblasts and local immune

cells.

Globally, epithelial ovarian cancer leads to

>185,000 fatalities annually. HGSOC, the predominant variant,

contributes to ~60% of these deaths. Despite advancements in

surgical techniques and chemotherapy protocols, the mortality rate

for HGSOC has remained high over the past several decades (141). The primary cause is the lack of

reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis. Exosomes, which contain

numerous ncRNAs, have increasingly been recognized as key players

in intercellular communication. ncRNAs, including circRNAs, lncRNAs

and miRNAs, are crucial for tumor development. Exosomal ncRNAs can

be packaged, secreted and transported by tumor and normal cells to

influence each other and complete the establishment of OC. Exosomes

from OC could stimulate the establishment of PMNs by

immunosuppression, angiogenesis, stromal cell modification and

oncogenic reprogramming to promote tumor metastasis and growth.

Although exosomes and exosomal ncRNAs are innovative indicators for

the prognosis and diagnosis of OC, several issues hinder their use

in clinical settings. First, only a limited quantity of exosomes is

present in biological fluids. Second, there is limited knowledge

about the biological functions of ncRNAs. Despite these challenges,

exosomes and ncRNAs are promising biomarkers for the identification

and management of OC.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

XW was responsible for writing and revising the

manuscript. MY participated in the literature review and provided

feedback. JZ and YZ provided substantial contributions to

conception and design. GL was responsible for revising the

manuscript and providing financial support. Data authentication is

not applicable. All the authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Dr Gencui Li ORCID: 0009-0004-1397-3204.

|

1

|

Yang C, Kim HS, Song G and Lim W: The

potential role of exosomes derived from ovarian cancer cells for

diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. J Cell Physiol.

234:21493–21503. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Stewart C, Ralyea C and Lockwood S:

Ovarian cancer: An integrated review. Semin Oncol Nurs. 35:151–156.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Koshiyama M, Matsumura N and Konishi I:

Subtypes of ovarian cancer and ovarian cancer screening.

Diagnostics (Basel). 7:122017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lheureux S, Braunstein M and Oza AM:

Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of

precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 69:280–304. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lisio MA, Fu L, Goyeneche A, Gao ZH and

Telleria C: High-grade serous ovarian cancer: Basic sciences,

clinical and therapeutic standpoints. Int J Mol Sci. 20:9522019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sierra J, Marrugo-Ramirez J,

Rodríguez-Trujillo R, Mir M and Samitier J: Sensor-integrated

microfluidic approaches for liquid biopsies applications in early

detection of cancer. Sensors (Basel). 20:13172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bellassai N, D'Agata R, Jungbluth V and

Spoto G: Surface plasmon resonance for biomarker detection:

Advances in non-invasive cancer diagnosis. Front Chem. 7:5702019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Miao M, Miao Y, Zhu Y, Wang J and Zhou H:

Advances in exosomes as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for

gynaecological malignancies. Cancers (Basel). 14:47432022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Maurano MT, Humbert R, Rynes E, Thurman

RE, Haugen E, Wang H, Reynolds AP, Sandstrom R, Qu H, Brody J, et

al: Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation

in regulatory DNA. Science. 337:1190–1195. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Morris KV and Mattick JS: The rise of

regulatory RNA. Nat Rev Genet. 15:423–437. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hauptman N and Glavač D: Long non-coding

RNA in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 14:4655–4669. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C,

Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al:

Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature.

409:860–921. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Beg A, Parveen R, Fouad H, Yahia ME and

Hassanein AS: Role of different non-coding RNAs as ovarian cancer

biomarkers. J Ovarian Res. 15:722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fu G, Brkić J, Hayder H and Peng C:

MicroRNAs in human placental development and pregnancy

complications. Int J Mol Sci. 14:5519–5544. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, Huang DY,

Huang KH, Lee MJ, Galas DJ and Wang K: The microRNA spectrum in 12

body fluids. Clin Chem. 56:1733–1741. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Théry C: Exosomes: Secreted vesicles and

intercellular communications. F1000 Biol Rep. 3:152011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Théry C, Zitvogel L and Amigorena S:

Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol.

2:569–579. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U,

Sahu A, Hosono Y, Barrette TR, Prensner JR, Evans JR, Zhao S, et

al: The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human

transcriptome. Nat Genet. 47:199–208. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang KC and Chang HY: Molecular mechanisms

of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 43:904–914. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Guo X, Gao Y, Song Q, Wei J, Wu J, Dong J,

Chen L, Xu S, Wu D, Yang X, et al: Early assessment of circulating

exosomal lncRNA-GC1 for monitoring neoadjuvant chemotherapy

response in gastric cancer. Int J Surg. 109:1094–1104. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Obi P and Chen YG: The design and

synthesis of circular RNAs. Methods. 196:85–103. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen LL: The expanding regulatory

mechanisms and cellular functions of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 21:475–490. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Pan BT, Teng K, Wu C, Adam M and Johnstone

RM: Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the

transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J

Cell Biol. 101:942–948. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Isaac R, Reis FCG, Ying W and Olefsky JM:

Exosomes as mediators of intercellular crosstalk in metabolism.

Cell Metab. 33:1744–1762. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Qi Y, Xu R, Song C, Hao M, Gao Y, Xin M,

Liu Q, Chen H, Wu X, Sun R, et al: A comprehensive database of

exosome molecular biomarkers and disease-gene associations. Sci

Data. 11:2102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kalluri R and McAndrews KM: The role of

extracellular vesicles in cancer. Cell. 186:1610–1626. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mannelli C: Tissue vs liquid biopsies for

cancer detection: Ethical issues. J Bioeth Inq. 16:551–557. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xie H and Kim RD: The application of

circulating tumor DNA in the screening, surveillance, and treatment

monitoring of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 28:1845–1858.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yang WL, Lu Z, Guo J, Fellman BM, Ning J,

Lu KH, Menon U, Kobayashi M, Hanash SM, Celestino J, et al: Human

epididymis protein 4 antigen-autoantibody complexes complement

cancer antigen 125 for detecting early-stage ovarian cancer.

Cancer. 126:725–736. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yu W, Hurley J, Roberts D, Chakrabortty

SK, Enderle D, Noerholm M, Breakefield XO and Skog JK:

Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: Opportunities and

challenges. Ann Oncol. 32:466–477. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kalluri R: The biology and function of

exosomes in cancer. J Clin Invest. 126:1208–1215. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Spina V and Rossi D: Liquid biopsy in

tissue-born lymphomas. Swiss Med Wkly. 149:w147092019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lianidou ES, Mavroudis D, Sotiropoulou G,

Agelaki S and Pantel K: What's new on circulating tumor cells? A

meeting report. Breast Cancer Res. 12:3072010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shigeyasu K, Toden S, Zumwalt TJ, Okugawa

Y and Goel A: Emerging role of MicroRNAs as liquid biopsy

biomarkers in gastrointestinal cancers. Clin Cancer Res.

23:2391–2399. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ebrahimi N, Faghihkhorasani F, Fakhr SS,

Moghaddam PR, Yazdani E, Kheradmand Z, Rezaei-Tazangi F, Adelian S,

Mobarak H, Hamblin MR and Aref AR: Tumor-derived exosomal

non-coding RNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in cancer. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 79:5722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kalluri R and LeBleu VS: The biology,

function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science.

367:eaau69772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li C, Ni YQ, Xu H, Xiang QY, Zhao Y, Zhan

JK, He JY, Li S and Liu YS: Roles and mechanisms of exosomal

non-coding RNAs in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 6:3832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, Gentry-Maharaj

A, Burnell M, Kalsi JK, Amso NN, Apostolidou S, Benjamin E,

Cruickshank D, et al: Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the

UK collaborative trial of ovarian cancer screening (UKCTOCS): A

randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 387:945–956. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Anastasiadou E, Jacob LS and Slack FJ:

Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:5–18. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lee RC, Feinbaum RL and Ambros V: The C.

elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense

complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 75:843–854. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gareev I, Beylerli O, Yang G, Sun J,

Pavlov V, Izmailov A, Shi H and Zhao S: The current state of MiRNAs

as biomarkers and therapeutic tools. Clin Exp Med. 20:349–359.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y and Peng C:

Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and

circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9:4022018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Toden S and Goel A: Non-coding RNAs as

liquid biopsy biomarkers in cancer. Br J Cancer. 126:351–360. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang Z, Qin YW, Brewer G and Jing Q:

MicroRNA degradation and turnover: Regulating the regulators. Wiley

Interdiscip Rev RNA. 3:593–600. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ha M and Kim VN: Regulation of microRNA

biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15:509–524. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RHA, Ketting

RF and Hannon GJ: Processing of primary microRNAs by the

Microprocessor complex. Nature. 432:231–235. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H and

Kim VN: The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing.

Genes Dev. 18:3016–3027. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yoda M, Kawamata T, Paroo Z, Ye X, Iwasaki

S, Liu Q and Tomari Y: ATP-dependent human RISC assembly pathways.

Nat Struct Mol Biol. 17:17–23. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ambros V: The functions of animal

microRNAs. Nature. 431:350–355. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Broughton JP, Lovci MT, Huang JL, Yeo GW

and Pasquinelli AE: Pairing beyond the seed supports MicroRNA

targeting specificity. Mol Cell. 64:320–333. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Braun JE, Huntzinger E and Izaurralde E:

The role of GW182 proteins in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Adv

Exp Med Biol. 768:147–163. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hayder H, O'Brien J, Nadeem U and Peng C:

MicroRNAs: Crucial regulators of placental development.

Reproduction. 155:R259–R271. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Christie M, Boland A, Huntzinger E,

Weichenrieder O and Izaurralde E: Structure of the PAN3

pseudokinase reveals the basis for interactions with the PAN2

deadenylase and the GW182 proteins. Mol Cell. 51:360–373. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Vasudevan S and Steitz JA:

AU-rich-element-mediated upregulation of translation by FXR1 and

argonaute 2. Cell. 128:1105–1118. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Peng Y and Croce CM: The role of MicroRNAs

in human cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 1:150042016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP and Anderson TA:

microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 302:1–12.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chou CH, Chang NW, Shrestha S, Hsu SD, Lin

YL, Lee WH, Yang CD, Hong HC, Wei TY, Tu SJ, et al: miRTarBase

2016: Updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target

interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(D1): D239–D247. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kang M, Tang B, Li J, Zhou Z, Liu K, Wang

R, Jiang Z, Bi F, Patrick D, Kim D, et al: Identification of

miPEP133 as a novel tumor-suppressor microprotein encoded by

miR-34a pri-miRNA. Mol Cancer. 19:1432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhang WC, Chin TM, Yang H, Nga ME, Lunny

DP, Lim EK, Sun LL, Pang YH, Leow YN, Malusay SR, et al:

Tumour-initiating cell-specific miR-1246 and miR-1290 expression

converge to promote non-small cell lung cancer progression. Nat

Commun. 7:117022016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chai S, Ng KY, Tong M, Lau EY, Lee TK,

Chan KW, Yuan YF, Cheung TT, Cheung ST, Wang XQ, et al: Octamer 4/

microRNA-1246 signaling axis drives Wnt/β-catenin activation in

liver cancer stem cells. Hepatology. 64:2062–2076. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Cooks T, Pateras IS, Jenkins LM, Patel KM,

Robles AI, Morris J, Forshew T, Appella E, Gorgoulis VG and Harris

CC: Mutant p53 cancers reprogram macrophages to tumor supporting

macrophages via exosomal miR-1246. Nat Commun. 9:7712018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wang W, Jo H, Park S, Kim H, Kim SI, Han

Y, Lee J, Seol A, Kim J, Lee M, et al: Integrated analysis of

ascites and plasma extracellular vesicles identifies a miRNA-based

diagnostic signature in ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett.

542:2157352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kanlikilicer P, Bayraktar R, Denizli M,

Rashed MH, Ivan C, Aslan B, Mitra R, Karagoz K, Bayraktar E, Zhang

X, et al: Exosomal miRNA confers chemo resistance via targeting

Cav1/p-gp/M2-type macrophage axis in ovarian cancer. EBioMedicine.

38:100–112. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yamashita R, Sato M, Kakumu T, Hase T,

Yogo N, Maruyama E, Sekido Y, Kondo M and Hasegawa Y: Growth

inhibitory effects of miR-221 and miR-222 in non-small cell lung

cancer cells. Cancer Med. 4:551–564. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Li J, Li Q, Huang H, Li Y, Li L, Hou W and

You Z: Overexpression of miRNA-221 promotes cell proliferation by

targeting the apoptotic protease activating factor-1 and indicates

a poor prognosis in ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 50:1087–1096.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu CH, Jing XN, Liu XL, Qin SY, Liu MW

and Hou CH: Tumor-suppressor miRNA-27b-5p regulates the growth and

metastatic behaviors of ovarian carcinoma cells by targeting CXCL1.

J Ovarian Res. 13:922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature.

474:609–615. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Tothill RW, Tinker AV, George J, Brown R,

Fox SB, Lade S, Johnson DS, Trivett MK, Etemadmoghadam D, Locandro

B, et al: Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid

ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res.

14:5198–5208. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liu R, Hu R, Zeng Y, Zhang W and Zhou HH:

Tumour immune cell infiltration and survival after platinum-based

chemotherapy in high-grade serous ovarian cancer subtypes: A gene

expression-based computational study. EBioMedicine. 51:1026022020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Yang Z, Wang W, Zhao L, Wang X, Gimple RC,

Xu L, Wang Y, Rich JN and Zhou S: Plasma cells shape the

mesenchymal identity of ovarian cancers through transfer of

exosome-derived microRNAs. Sci Adv. 7:eabb07372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Brannan CI, Dees EC, Ingram RS and

Tilghman SM: The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA.

Mol Cell Biol. 10:28–36. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhao L, Sun W, Zheng A, Zhang Y, Fang C

and Zhang P: Ginsenoside Rg3 suppresses ovarian cancer cell

proliferation and invasion by inhibiting the expression of lncRNA

H19. Acta Biochim Pol. 68:575–582. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Hartford CCR and Lal A: When long

noncoding becomes protein coding. Mol Cell Biol. 40:e00528–19.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Quinn JJ and Chang HY: Unique features of

long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet.

17:47–62. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Ransohoff JD, Wei Y and Khavari PA: The

functions and unique features of long intergenic non-coding RNA.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19:143–157. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Carninci P,

Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen LL, Chen R, Dean C, Dinger ME,

Fitzgerald KA, et al: Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions,

challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:430–447.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

St Laurent G, Wahlestedt C and Kapranov P:

The Landscape of long noncoding RNA classification. Trends Genet.

31:239–251. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wang H, Meng Q, Qian J, Li M, Gu C and

Yang Y: Review: RNA-based diagnostic markers discovery and

therapeutic targets development in cancer. Pharmacol Ther.

234:1081232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kopp F and Mendell JT: Functional

classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs.

Cell. 172:393–407. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Graf J and Kretz M: From structure to

function: Route to understanding lncRNA mechanism. Bioessays.

42:e20000272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Seetin MG and Mathews DH: RNA structure

prediction: An overview of methods. Methods Mol Biol. 905:99–122.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Lampropoulou DI, Papadimitriou M,

Papadimitriou C, Filippou D, Kourlaba G, Aravantinos G and Gazouli

M: The role of EMT-related lncRNAs in ovarian cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:100792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liang H, Yu T, Han Y, Jiang H, Wang C, You

T, Zhao X, Shan H, Yang R, Yang L, et al: LncRNA PTAR promotes EMT

and invasion-metastasis in serous ovarian cancer by competitively

binding miR-101-3p to regulate ZEB1 expression. Mol Cancer.

17:1192018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Leung D, Price ZK, Lokman NA, Wang W,

Goonetilleke L, Kadife E, Oehler MK, Ricciardelli C, Kannourakis G

and Ahmed N: Platinum-resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer: An

interplay of epithelial-mesenchymal transition interlinked with

reprogrammed metabolism. J Transl Med. 20:5562022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Kralj J, Pernar Kovač M, Dabelić S,

Polančec DS, Wachtmeister T, Köhrer K and Brozovic A: Transcriptome

analysis of newly established carboplatin-resistant ovarian cancer

cell model reveals genes shared by drug resistance and drug-induced

EMT. Br J Cancer. 128:1344–1359. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Teschendorff AE, Lee SH, Jones A, Fiegl H,

Kalwa M, Wagner W, Chindera K, Evans I, Dubeau L, Orjalo A, et al:

HOTAIR and its surrogate DNA methylation signature indicate

carboplatin resistance in ovarian cancer. Genome Med. 7:1082015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings

HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al: Long

non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer

metastasis. Nature. 464:1071–1076. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal

M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al:

A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in

embryonic stem cells. Cell. 125:315–326. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, Guenther MG,

Levine SS, Kumar RM, Chevalier B, Johnstone SE, Cole MF, Isono K,

et al: Control of developmental regulators by polycomb in human

embryonic stem cells. Cell. 125:301–313. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Teschendorff AE, Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj

A, Ramus SJ, Weisenberger DJ, Shen H, Campan M, Noushmehr H, Bell

CG, Maxwell AP, et al: Age-dependent DNA methylation of genes that

are suppressed in stem cells is a hallmark of cancer. Genome Res.

20:440–446. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Qiu JJ, Lin YY, Ye LC, Ding JX, Feng WW,

Jin HY, Zhang Y, Li Q and Hua KQ: Overexpression of long non-coding

RNA HOTAIR predicts poor patient prognosis and promotes tumor

metastasis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

134:121–128. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Yang S, Ji J, Wang M, Nie J and Wang S:

Construction of ovarian cancer prognostic model based on the

investigation of ferroptosis-related lncRNA. Biomolecules.

13:3062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Jin Y, Qiu J, Lu X, Ma Y and Li G: LncRNA

CACNA1G-AS1 up-regulates FTH1 to inhibit ferroptosis and promote

malignant phenotypes in ovarian cancer cells. Oncol Res.

31:169–179. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Cai L, Hu X, Ye L, Bai P, Jie Y and Shu K:

Long non-coding RNA ADAMTS9-AS1 attenuates ferroptosis by Targeting

microRNA-587/solute carrier family 7 member 11 axis in epithelial

ovarian cancer. Bioengineered. 13:8226–8239. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Liu F, Cao L, Zhang Y, Xia X and Ji Y:

LncRNA LIFR-AS1 overexpression suppressed the progression of serous

ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 36:e254702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Lin X, Feng D, Li P and Lv Y: LncRNA

LINC00857 regulates the progression and glycolysis in ovarian

cancer by modulating the Hippo signaling pathway. Cancer Med.

9:8122–8132. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ

and Kleinschmidt AK: Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed

circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like

structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 73:3852–3856. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, Li S, Guo W, Zhao J,

Chen D, Gu J, He X and Huang S: Circular RNA is enriched and stable

in exosomes: A promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res.

25:981–984. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Meng X, Li X, Zhang P, Wang J, Zhou Y and

Chen M: Circular RNA: An emerging key player in RNA world. Brief

Bioinform. 18:547–557. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Patop IL, Wüst S and Kadener S: Past,

present, and future of circRNAs. EMBO J. 38:e1008362019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Yao T, Chen Q, Fu L and Guo J: Circular

RNAs: Biogenesis, properties, roles, and their relationships with

liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 47:497–504. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Lasda E and Parker R: Circular RNAs

co-precipitate with extracellular vesicles: A possible mechanism

for circRNA clearance. PLoS One. 11:e01484072016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Ngo LH, Bert AG, Dredge BK, Williams T,

Murphy V, Li W, Hamilton WB, Carey KT, Toubia J, Pillman KA, et al:

Nuclear export of circular RNA. Nature. 627:212–220. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Pisignano G, Michael DC, Visal TH, Pirlog

R, Ladomery M and Calin GA: Going circular: History, present, and

future of circRNAs in cancer. Oncogene. 42:2783–2800. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK,

Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF and Sharpless NE: Circular RNAs are

abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA.

19:141–157. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Shang Q, Yang Z, Jia R and Ge S: The novel

roles of circRNAs in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 18:62019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Ye D, Gong M, Deng Y, Fang S, Cao Y, Xiang

Y and Shen Z: Roles and clinical application of exosomal circRNAs

in the diagnosis and treatment of malignant tumors. J Transl Med.

20:1612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Su M, Xiao Y, Ma J, Tang Y, Tian B, Zhang

Y, Li X, Wu Z, Yang D, Zhou Y, et al: Circular RNAs in cancer:

Emerging functions in hallmarks, stemness, resistance and roles as

potential biomarkers. Mol Cancer. 18:902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Cortes R and Forner MJ: Circular RNAS:

Novel biomarkers of disease activity in systemic lupus

erythematosus? Clin Sci (Lond). 133:1049–1052. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Liu CX and Chen LL: Circular RNAs:

Characterization, cellular roles, and applications. Cell.

185:2016–2034. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Lei M, Zheng G, Ning Q, Zheng J and Dong

D: Translation and functional roles of circular RNAs in human

cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Zhao Q, Liu J, Deng H, Ma R, Liao JY,

Liang H, Hu J, Li J, Guo Z, Cai J, et al: Targeting

mitochondria-located circRNA SCAR alleviates NASH via reducing mROS

output. Cell. 183:76–93.e22. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Huang D, Zhu X, Ye S, Zhang J, Liao J,

Zhang N, Zeng X, Wang J, Yang B, Zhang Y, et al: Tumour circular

RNAs elicit anti-tumour immunity by encoding cryptic peptides.

Nature. 625:593–602. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Li H, Lin R, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Huang S, Lan

J, Lu N, Xie C, He S and Zhang W: N6-methyladenosine-modified

circPLPP4 sustains cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells via

PIK3R1 upregulation. Mol Cancer. 23:52024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Zhou X, Jiang J and Guo S:

Hsa_circ_0004712 downregulation attenuates ovarian cancer malignant

development by targeting the miR-331-3p/FZD4 pathway. J Ovarian

Res. 14:1182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Camuzard O, Santucci-Darmanin S, Carle GF

and Pierrefite-Carle V: Autophagy in the crosstalk between tumor

and microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 490:143–153. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Ye J, Wu D, Wu P, Chen Z and Huang J: The

cancer stem cell niche: Cross talk between cancer stem cells and

their microenvironment. Tumour Biol. 35:3945–3951. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley

AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, et

al: VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate

the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 438:820–827. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Yue M, Hu S, Sun H, Tuo B, Jia B, Chen C,

Wang W, Liu J, Liu Y, Sun Z and Hu J: Extracellular vesicles

remodel tumor environment for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer.

22:2032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Mei S, Chen X, Wang K and Chen Y: Tumor

microenvironment in ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Cancer

Cell Int. 23:112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Lorusso D, Ceni V, Daniele G, Salutari V,

Pietragalla A, Muratore M, Nero C, Ciccarone F and Scambia G: Newly

diagnosed ovarian cancer: Which first-line treatment? Cancer Treat

Rev. 91:1021112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Mo Y, Leung LL, Mak CSL, Wang X, Chan WS,

Hui LMN, Tang HWM, Siu MKY, Sharma R, Xu D, et al: Tumor-secreted

exosomal miR-141 activates tumor-stroma interactions and controls

premetastatic niche formation in ovarian cancer metastasis. Mol

Cancer. 22:42023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Yi H, Ye J, Yang XM, Zhang LW, Zhang ZG

and Chen YP: High-grade ovarian cancer secreting effective exosomes

in tumor angiogenesis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 8:5062–5070.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Leary N, Walser S, He Y, Cousin N, Pereira

P, Gallo A, Collado-Diaz V, Halin C, Garcia-Silva S, Peinado H and

Dieterich LC: Melanoma-derived extracellular vesicles mediate

lymphatic remodelling and impair tumour immunity in draining lymph

nodes. J Extracell Vesicles. 11:e121972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Chen G, Huang AC, Zhang W, Zhang G, Wu M,

Xu W, Yu Z, Yang J, Wang B, Sun H, et al: Exosomal PD-L1

contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1

response. Nature. 560:382–386. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Kelleher RJ Jr, Balu-Iyer S, Loyall J,

Sacca AJ, Shenoy GN, Peng P, Iyer V, Fathallah AM, Berenson CS,

Wallace PK, et al: Extracellular vesicles present in human ovarian

tumor microenvironments induce a phosphatidylserine-dependent

arrest in the T-cell signaling cascade. Cancer Immunol Res.

3:1269–1278. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Arenaccio C, Chiozzini C, Columba-Cabezas

S, Manfredi F, Affabris E, Baur A and Federico M: Exosomes from

human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected cells license

quiescent CD4+ T lymphocytes to replicate HIV-1 through a Nef- and

ADAM17-dependent mechanism. J Virol. 88:11529–11539. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Lugini L, Cecchetti S, Huber V, Luciani F,

Macchia G, Spadaro F, Paris L, Abalsamo L, Colone M, Molinari A, et

al: Immune surveillance properties of human NK cell-derived

exosomes. J Immunol. 189:2833–2842. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Luo H, Zhou Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Long S,

Lin X, Yang A, Duan J, Yang N, Yang Z, et al: NK cell-derived

exosomes enhance the anti-tumor effects against ovarian cancer by

delivering cisplatin and reactivating NK cell functions. Front

Immunol. 13:10876892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Shiao MS, Chang JM, Lertkhachonsuk AA,

Rermluk N and Jinawath N: Circulating exosomal miRNAs as biomarkers

in epithelial ovarian cancer. Biomedicines. 9:14332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, Johnson CC,

Lamerato L, Isaacs C, Reding DJ, Greenlee RT, Yokochi LA, Kessel B,

et al: Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: The

prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening

randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 305:2295–2303. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Moss EL, Hollingworth J and Reynolds TM:

The role of CA125 in clinical practice. J Clin Pathol. 58:308–312.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Yokoi A, Yoshioka Y, Hirakawa A, Yamamoto

Y, Ishikawa M, Ikeda SI, Kato T, Niimi K, Kajiyama H, Kikkawa F and

Ochiya T: A combination of circulating miRNAs for the early

detection of ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 8:89811–89823. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Wang S and Song X, Wang K, Zheng B, Lin Q,

Yu M, Xie L, Chen L and Song X: Plasma exosomal miR-320d, miR-4479,

and miR-6763-5p as diagnostic biomarkers in epithelial ovarian

cancer. Front Oncol. 12:9863432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Pan C, Stevic I, Müller V, Ni Q,

Oliveira-Ferrer L, Pantel K and Schwarzenbach H: Exosomal microRNAs

as tumor markers in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol.

12:1935–1948. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Maeda K, Sasaki H, Ueda S, Miyamoto S,

Terada S, Konishi H, Kogata Y, Ashihara K, Fujiwara S, Tanaka Y, et

al: Serum exosomal microRNA-34a as a potential biomarker in

epithelial ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 13:472020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Qiu JJ, Lin XJ, Tang XY, Zheng TT, Lin YY

and Hua KQ: Exosomal metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma

transcript 1 promotes angiogenesis and predicts poor prognosis in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 14:1960–1973. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Zhang W, Su X, Li S, Liu Z, Wang Q and

Zeng H: Low serum exosomal miR-484 expression predicts unfavorable

prognosis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biomark. 27:485–491. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Luo Y and Gui R: Circulating exosomal

circFoxp1 confers cisplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer

cells. J Gynecol Oncol. 31:e752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Chowdhury S, Kennedy JJ, Ivey RG, Murillo

OD, Hosseini N, Song X, Petralia F, Calinawan A, Savage SR, Berry

AB, et al: Proteogenomic analysis of chemo-refractory high-grade

serous ovarian cancer. Cell. 186:3476–3498.e35. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Martínez-Greene JA, Gómez-Chavarín M,

Ramos-Godínez MDP and Martínez-Martínez E: Isolation of hepatic and

adipose-tissue-derived extracellular vesicles using density

gradient separation and size exclusion chromatography. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:127042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Bai HH, Wang XF, Zhang BY and Liu W: A

comparison of size exclusion chromatography-based tandem strategies

for plasma exosome enrichment and proteomic analysis. Anal Methods.

15:6245–6251. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Takov K, Yellon DM and Davidson SM:

Comparison of small extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma by

ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography: Yield, purity

and functional potential. J Extracell Vesicles. 8:15608092018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Tian Y, Gong M, Hu Y, Liu H, Zhang W,

Zhang M, Hu X, Aubert D, Zhu S, Wu L and Yan X: Quality and

efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation

methods by nano-flow cytometry. J Extracell Vesicles.

9:16970282019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Aliakbari F, Stocek NB, Cole-André M,

Gomes J, Fanchini G, Pasternak SH, Christiansen G, Morshedi D,

Volkening K and Strong MJ: A methodological primer of extracellular

vesicles isolation and characterization via different techniques.

Biol Methods Protoc. 9:bpae0092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Knarr M, Avelar RA, Sekhar SC, Kwiatkowski

LJ, Dziubinski ML, McAnulty J, Skala S, Avril S, Drapkin R and

DiFeo A: miR-181a initiates and perpetuates oncogenic

transformation through the regulation of innate immune signaling.

Nat Commun. 11:32312020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Wu M, Qiu Q, Zhou Q, Li J, Yang J, Zheng

C, Luo A, Li X, Zhang H, Cheng X, et al: circFBXO7/miR-96-5p/MTSS1

axis is an important regulator in the Wnt signaling pathway in

ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer. 21:1372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Luo L, Gao YQ and Sun XF: Circular RNA

ITCH suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis in human

epithelial ovarian cancer cells by sponging miR-10a-α. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 22:8119–8126. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Ying X, Wu Q, Wu X, Zhu Q and Wang X,

Jiang L, Chen X and Wang X: Epithelial ovarian cancer-secreted

exosomal miR-222-3p induces polarization of tumor-associated

macrophages. Oncotarget. 7:43076–43087. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

151

|

Cappellesso R, Tinazzi A, Giurici T,

Simonato F, Guzzardo V, Ventura L, Crescenzi M, Chiarelli S and

Fassina A: Programmed cell death 4 and microRNA 21 inverse

expression is maintained in cells and exosomes from ovarian serous

carcinoma effusions. Cancer Cytopathol. 122:685–693. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Meng X, Müller V, Milde-Langosch K,

Trillsch F, Pantel K and Schwarzenbach H: Diagnostic and prognostic

relevance of circulating exosomal miR-373, miR-200a, miR-200b and

miR-200c in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget.

7:16923–16935. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Zavesky L, Jandakova E, Turyna R,

Langmeierova L, Weinberger V and Minar L: Supernatant versus

exosomal urinary microRNAs. Two fractions with different outcomes

in gynaecological cancers. Neoplasma. 63:121–132. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Zhou J, Gong G, Tan H, Dai F, Zhu X, Chen

Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Chen P, Wu X and Wen J: Urinary microRNA-30a-5p

is a potential biomarker for ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. Oncol

Rep. 33:2915–2923. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Hong JS, Son T, Castro CM and Im H:

CRISPR/Cas13a-based MicroRNA detection in tumor-derived

extracellular vesicles. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23017662023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

156

|

Zhang L, Zhou Q, Qiu Q, Hou L, Wu M, Li J,

Li X, Lu B, Cheng X, Liu P, et al: CircPLEKHM3 acts as a tumor

suppressor through regulation of the miR-9/BRCA1/DNAJB6/KLF4/AKT1

axis in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer. 18:1442019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

157

|

Li L, Zhang F, Zhang J, Shi X, Wu H, Chao

X, Ma S, Lang J, Wu M, Zhang D and Liang Z: Identifying serum small

extracellular vesicle MicroRNA as a noninvasive diagnostic and

prognostic biomarker for ovarian cancer. ACS Nano. 17:19197–19210.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

158

|

Yu CC, Liao YW, Hsieh PL and Chang YC:

Targeting lncRNA H19/miR-29b/COL1A1 axis impedes myofibroblast

activities of precancerous oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci.

22:22162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

159

|

Záveský L, Jandáková E, Turyna R,

Langmeierová L, Weinberger V, Záveská Drábková L, Hůlková M,

Hořínek A, Dušková D, Feyereisl J, et al: Evaluation of cell-free

urine microRNAs expression for the use in diagnosis of ovarian and

endometrial cancers. A pilot study. Pathol Oncol Res. 21:1027–1035.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Wang LL, Sun KX, Wu DD, Xiu YL, Chen X,

Chen S, Zong ZH, Sang XB, Liu Y and Zhao Y: DLEU1 contributes to

ovarian carcinoma tumourigenesis and development by interacting