Introduction

Arterial calcification is marked by abnormal calcium

deposition and increased arterial stiffness, commonly observed in

patients with atherosclerosis or chronic kidney disease (CKD); it

is strongly linked to oxidative stress, chronic inflammation and

abnormal cell death, all of which contribute to heightened

cardiovascular risk (1). A key

initiating event in vascular calcification is the phenotypic switch

of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into osteoblast-like cells.

This transformation is characterized by the loss of VSMC-specific

markers and the acquisition of osteochondrogenic markers such as

runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and bone morphogenetic

protein 2 (BMP2), along with aberrant VSMC death (2). Inflammation acts as both a trigger

and consequence of calcification, creating a potentially vicious

cycle between inflammatory processes and arterial calcification.

Calcium phosphate crystals, which function as danger-associated

molecular patterns (DAMPs), activate caspase1 and promote the

maturation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), initiating a pro-inflammatory

cascade (3). A study has shown

increased IL-1β expression in CKD models with vascular

calcification, underscoring the pivotal role of inflammation in

this pathology (4). Nonetheless,

the extent to which suppressing inflammation in VSMCs might

mitigate vascular calcification remains largely unresolved.

Pyroptosis, a form of regulated cell death, was

initially identified as pro-inflammatory cell death in

Salmonella-infected macrophages (5). This form of cell death is driven by

inflammatory caspases, primarily caspase1, which activate

inflammatory cytokines and induce cell death, largely mediated by

inflammasomes (6). The NLR

family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is composed

of NLRP3, caspase1 and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC). A priming event

stimulates the transcription of NLRP3 and precursors of caspase1

(pro-caspase1) and IL-1β (pro-IL-1β) via toll-like receptor (TLR)

and nuclear factor κB signaling. The subsequent assembly of NLRP3,

ASC and pro-caspase1 leads to the formation of the NLRP3

inflammasome, triggering auto-cleavage of pro-caspase1 and the

maturation of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 (7). Simultaneously, caspase1 cleaves

gasdermin D (GSDMD), generating an N-terminal GSDMD fragment

(GSDMD-NT) that forms pores in the plasma membrane, facilitating

pyroptotic cell death (8).

Pyroptosis has been implicated in the progression of several

diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and

neurological disorders (9). In

cardiovascular contexts, NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been

shown to regulate VSMC phenotypic switching in conditions such as

atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic aneurysms (10,11). However, its specific role in

VSMCs during arterial calcification remains unclear.

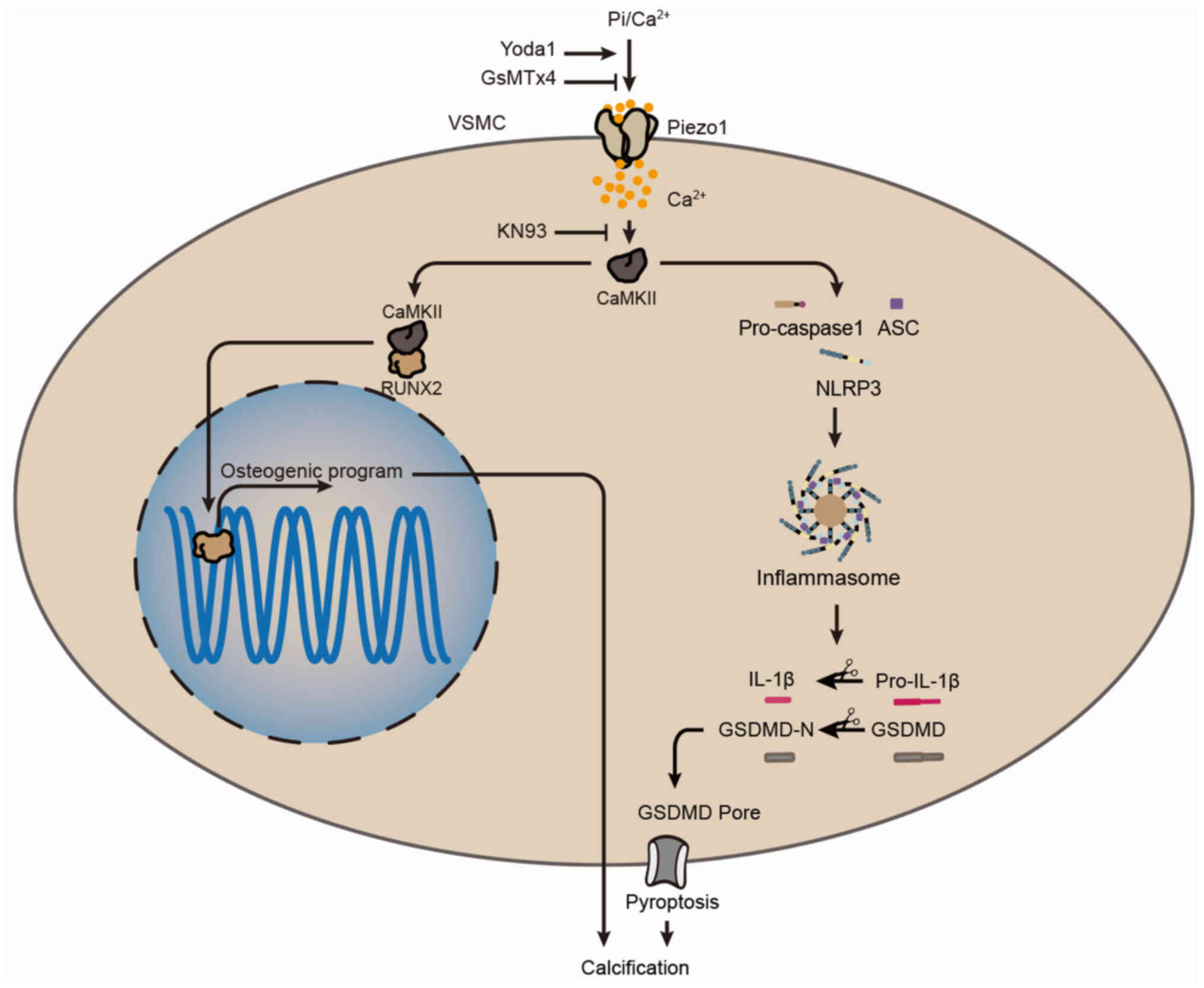

Piezo1 is a non-selective, mechanically gated cation

channel that converts mechanical stimuli into electrochemical

signals by facilitating the influx of cations such as calcium,

sodium and potassium across various cell types, including

endothelial cells, red blood cells and SMCs (12-14). This mechanotransduction is

involved in several physiological and pathological processes, such

as the development of blood and lymphatic vessels (12,13), the regulation of vascular tone

(15,16) and arterial remodeling (15). Additionally, Piezo1-induced

Ca2+ influx plays a critical role in the functions of

macrophages, particularly in inflammatory activation (17). As a key intracellular second

messenger, Ca2+ is essential for calcium/calmodulin

dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) activation. Upon binding to

the regulatory domain of CaMKII, Ca2+ triggers

autophosphorylation at threonine 286, leading to its sustained

activation. CaMKII is widely recognized as a key downstream

effector of Piezo1 signaling (18,19). Previous research has shown that

Piezo1 contributes to the pathology of aortic aneurysms and that

inhibiting Piezo1 reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice

(20). However, its involvement

in the inflammatory response and pyroptosis during arterial

calcification remains unexplored.

The present study aims to determine whether Piezo1

modulates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated VSMC pyroptosis and

contributes to arterial calcification while elucidating the

underlying mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Animal model

The procedures involving Apolipoprotein E knockout

(ApoE−/−) mice (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal

Technology Co., Ltd.) were conducted as previously described

(21). ApoE−/− mice

(8-week-old male) were housed in a controlled facility. Mice were

randomly divided into control and high-fat diet (HFD) (n=6 for each

group). The control and HFD mice were fed a regular diet and HFD

(Dyets, Inc.) for 12 weeks, respectively.

Piezo1flox/flox mice were generously provided by Jiaguo

Zhou's laboratory (Department of Pharmacology, Cardiac and Cerebral

Vascular Research Center, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-Sen

University, Guangzhou, China). For the generation of SMC-specific

Piezo1 knockout mice, the loxP-Cre system was utilized by

administering an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector expressing Cre

recombinase into Piezo1flox/flox mice (described below).

NLRP3−/− and caspase1−/− male mice, with a

C57BL/6J background, were obtained from ViewSolid Biotech Co., Ltd.

and their genotypes were validated through DNA sequencing as

previously described (22).

GSDMD−/− mice were generously provided by Xun Zhu's

laboratory (Department of Microbiology, Zhongshan School of

Medicine, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China.). All mice were

housed in a specific pathogen-free grade animal laboratory

(temperature 20±8°C, humidity 60±10%, with a 12-h light/dark cycle)

and given ad libitum access to standard rodent chow and

water.

The mice were checked daily for weight, health and

behavior. Animals were euthanized if they met the predefined

criteria, including rapid weight loss exceeding 15-20% of initial

body weight, severe weakness preventing independent access to food

or water, prolonged inability to stand (≥24 h) or clinical signs of

distress such as marked lethargy and hypothermia (core temperature

<37°C) in the absence of anesthesia. No mice in the present

study required euthanasia due to reaching these endpoints, as all

maintained stable health throughout the experimental period.

Euthanasia was conducted using CO2 at 30-70% vol/min

displacement in compliance with the AVMA guidelines: 2020 Edition

(23). The mice were confirmed

to be dead when the absence of a heartbeat, pulse, breathing and

corneal reflex was observed for >3 min. The animal experiments

adhered to ethical standards for animal research and was approved

by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun

Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China).

AAV construction and administration

The AAV vectors carrying Cre and the negative

control were constructed and packaged by HanBio Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd. Briefly, the pHBAAV-SM22a vector was selected for the present

study and the restriction enzymes, BamHI and HindIII,

were used to cleave the vector, yielding a purified linearized

construct. Mouse Cre fragments were amplified using the 2X Flash

PCR MasterMix (Dye) kit (CWbio), following the manufacturer's

protocol. The HB Infusion™ kit (Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was

then employed for the ligation of the linearized vector and mouse

Cre fragments, according to the manufacturer's instructions,

followed by the transformation of DH5α competent cells (Tiangen

Biotech Co., Ltd.). After cultivation in LB medium (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 12-16 h (selected by antibiotic

resistance selection using 100 μg/ml ampicillin), the

bacterial cultures were subjected to PCR identification using the

2X Hieff PCR Master Mix (Dye) kit (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.). The amplified sequence was verified by Sanger

sequencing to ensure consistency with Cre.

The plasmid was extracted using the TIANpure Mini

Plasmid Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.), and subsequently

co-transfected with packaging plasmids (pAAV-RC and pHelper) into

293T cells (Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) using Lipofiter™

transfection reagent (HanBio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The

transfection complex was prepared by mixing the following

components: pAAV-RC plasmid 10 μg, pHelper plasmid 20

μg, Shuttle plasmid 10 μg and Lipofiter 120

μl. The transfection complex was added to the cell culture

medium at room temperature. Following 72 h of transfection at 37°C

with 5% CO2, the 293T cells were harvested, lysed using

RIPA (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and centrifuged at 4°C

for 30 min (3,000 × g), with the supernatant collected for virus

purification using the ViraTrap™ AAV Purification Maxiprep Kit

(Biomiga, Inc.). The resulting viral titer was 1.6×1012

vg/ml. For gene delivery of Cre specifically to SMCs, the AAV was

administered via direct microinjection into the tail vein

(1×1011 vg per mouse).

Mice and cell calcification

construction

A total of 18 healthy Piezo1flox/flox

male mice were randomly divided into three experimental groups

(n=6/group): Normal diet, high-adenine diet (HAD) + AAV-vector and

HAD + AAV-SM22a-cre. The normal diet group received a standard

pellet chow diet, while the HAD + AAV-vector group was fed a HAD

(0.25% adenine and 1.2% phosphorus) after AAV-vector injection for

4 weeks. The HAD + AAV-SM22a-cre group also received HAD following

AAV-SM22a-cre injection for 4 weeks. After 12 weeks of receiving

the normal or special diet, the animals were sacrificed. Western

blot analysis was performed to validate the efficiency of

SMC-specific Piezo1 knockout.

The mice were checked daily for weight, health and

behavior. Animals were euthanized if they met the predefined

criteria, including rapid weight loss exceeding 15-20% of initial

body weight, severe weakness preventing independent access to food

or water, prolonged inability to stand (≥24 h) or clinical signs of

distress such as marked lethargy and hypothermia (core temperature

<37°C) in the absence of anesthesia. No mice in the present

study required euthanasia due to reaching these endpoints, as all

maintained stable health throughout the experimental period.

Euthanasia was conducted using CO2 at 30-70% vol/min

displacement in compliance with the AVMA guidelines: 2020 Edition

(23). The mice were confirmed

to be dead when the absence of a heartbeat, pulse, breathing and

corneal reflex was observed for >3 min, then the peripheral

venous blood and aorta tissues were harvested.

Primary VSMCs were isolated from C57BL/6J mice (8

weeks, 20-25 g, male, n=6/group; Laboratory Animal Center, Sun

Yat-sen University), as previously described (24). In brief, after sacrificing the

mice (as aforementioned), the thoracic and abdominal aortas were

dissected, minced and digested with collagenase (2 mg/ml) for 4 h.

The VSMCs were then cultured in Ham's F12 nutrient medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 7.5% FBS (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml

streptomycin and 2 mmol/l L-glutamine at 37°C with 5%

CO2. First-passage (P1) cells was used in subsequent

cell experiments. Human aortic SMCs (HASMCs) were kindly provided

by Professor Zhihan Tang's lab (Department of Pathophysiology,

Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, Key Laboratory for

Arteriosclerology of Hunan Province, University of South China,

Hengyang, China) and were cultured in Ham's F12 nutrient medium

supplemented with 7.5% FBS at 37°C under 5% CO2

(24). For the calcification

model, VSMCs at 60% confluency were incubated in a calcifying

medium (CM; containing 3.5 mM inorganic phosphate and 3 mM calcium)

for 7 days, with comparisons made to VSMCs in growth medium (GM).

SMCs at passages 3 to 8 were used for the experiments.

VSMCs were stimulated with oxidized low-density

lipoprotein (oxLDL; Guangzhou Yiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at

varying concentrations (25, 50 and 100 μg/ml), with

untreated cells serving as the blank control. After 24 h, cell

lysates were collected for subsequent analysis. To assess the

impact of NLRP3 inhibition by MCC950 (Selleck Chemicals) on

CM-induced calcification, cells were divided into four groups:

Control (GM), CM, CM + MCC950 (CM + 100 μM MCC950) and

MCC950 (GM + 100 μM MCC950). Similarly, the role of CaMKII

inhibition by KN93 (Selleck Chemicals) in CM-triggered pyroptosis

was examined using three groups: Control (GM), CM, and CM + KN93

(CM + 10 μM KN93). After 7 days, cell lysates were harvested

for further analysis.

Piezo1 differential analysis using gene

expression omnibus (GEO) data

Data of the differential expression of Piezo1 (NCBI

GEO datasets portal: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GEO accession no.

GSE43292) between macroscopically intact tissue and atheroma plaque

was analyzed. The mRNA from microarray analysis had been submitted

by Ayari and Bricca (25). Data

analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.02 (Dotmatics).

Aortic ring culture

Thoracic to iliac aortas were aseptically excised

from male wild type (n=6) and knockout mice (NLRP3−/−,

caspase1−/− or GSDMD−/−) (8 weeks, 20-25 g,

n=6/group). After meticulous removal of the adventitia and

endothelium, the vessels were segmented into 2-3 mm rings. These

segments were then cultured for 7 days at 37°C under 5%

CO2, with media refreshed every 48 h, using either the

calcification medium or standard culture medium. The organ culture

experiments were replicated three times under identical

conditions.

Antibodies and reagents

The primary antibodies employed in the experiments

included anti-Piezo1 (Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 15939-1-AP;

1:1,000), anti-α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 19245s; 1:2,000), anti-alkaline

phosphatase (ALP; Novus Biologicals, LLC; Bio-Techne; cat. no.

NBP2-67295; 1:2,000), anti-BMP2 (Novus Biologicals, LLC;

Bio-Techne; cat. no. NBP1-19751; 1:2,000), anti-RUNX2 (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 8486s; 1:2,000), anti-β-actin

(Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 3700S; 1:5,000),

anti-NLRP3 (Adipogen Life Sciences; cat. no. AG-20B-0014-C100;

1:2,000), anti-caspase1 (Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

A0964; 1:2,000), anti-caspase1 p20 (Biorbyt, Ltd.; cat. no.

orb221355; 1:2,000), anti-GSDMD (ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company;

cat. no. YT7991; 1:2,000), anti-pro-IL-1β (ImmunoWay Biotechnology

Company; cat. no. YM8498; 1:2,000), anti-IL-1β (ImmunoWay

Biotechnology Company; cat. no. YT5201; 1:2,000) and anti-CaMKIIδ

(Abcam; cat. no. ab181052; 1:2,000). Secondary antibodies used for

western blotting included HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)

(Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 7076s; 1:5,000) and

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 7074s; 1:5,000). For immunofluorescence,

Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam; cat. no.

ab150077; 1:50) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG

(Abcam; cat. no. ab150115; 1:50), GsMTx4 (Abcam; cat. no. ab141871)

and Yoda1 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. SML1558) were

used.

Mouse echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed prior to sacrifice

while the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction, 3%;

maintenance, 1.5%). Data were collected using the Vivo 2100 imaging

system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Inc.), as described previously

(26). Measurements of wall

thickness and lumen diameter were obtained using the system's

dedicated software.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

siRNA transfection was performed when cells reached

80% confluency, employing the riboFECT™ CP Transfection Kit

(Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. For Piezo1 knockdown, VSMCs were treated with siRNA

against mouse Piezo1 (siPiezo1). The sequence of siPiezo1 was as

follows: 5'-UACCGAUCUCCAGAGACCAUGAUUA-3' for the sense strand, and

5'-UAAUCAUGGUCUGUGGAGAUCGGUU-3' for the antisense strand. The

sequence of the control siRNA was as follows:

5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3' for the sense strand, and

3'-DTDTAAGAGGCUUGCACAGUGCA-5' for the antisense strand. A 10

μl aliquot of 50 μM siPIEZO1 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) or negative control was combined with 120

μl of 1X riboFECT CP buffer, followed by the addition of 12

μl riboFECT CP reagent. After brief vortexing, the solution

was maintained at 23°C for 15 min. Culture medium was then added to

the prepared complex to achieve a 2 ml final volume at room

temperature, before application to the plated cells. After 48 h of

transfection, western blot analysis was performed to validate the

efficiency of Piezo1 knockdown.

Western blotting

Protein expression was determined by western

blotting as previously described (22). In brief, total protein was

extracted from treated cells using RIPA buffer supplemented with a

protease inhibitor cocktail and quantified using the BCA Protein

Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After separating 40

μg of protein per lane by 10% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), the proteins

were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and blocked

with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h. Membranes were

incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, followed by a

2-h incubation with secondary antibodies at room temperature. Bound

proteins were visualized using ECL (MilliporeSigma) and detected on

the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+ chemiluminescent imaging system. Relative

protein levels were normalized to β-actin as a loading control and

quantified using ImageJ 1.52a software (National Institutes of

Health).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane

potential (MMP)

The MMP was assessed using JC-1 staining following

the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were incubated in fresh

culture medium containing JC-1 dye (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. After two washes

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), a confocal laser scanning

microscope (LSM780; Zeiss GmbH) was used to immediately analyze the

samples with 490 nm excitation. Green fluorescence, indicating JC-1

monomers, was recorded at 530 nm emission, while red fluorescence,

representing JC-1 aggregates, was recorded at 590 nm. The ratio of

yellow fluorescence intensity was calculated using ImageJ 1.52a

software to assess the results.

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescence staining was conducted as

previously outlined (22). In

summary, aortic rings or cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h at 4°C, sectioned into 7 μm cryostat slices or

prepared on chamber slides, followed by blocking with 10% FBS at

room temperature for 2 h and permeabilization with Triton X-100.

The slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies against Piezo1 (1:50), NLRP3 (1:50), ASC (1:50) and

α-SMA (1:50). After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies were

applied for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the slides were

mounted using a DAPI-containing solution and visualized using a

confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM780; Zeiss GmbH). Data

analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.52a software.

Alizarin Red S and von Kossa

staining

Calcium deposition in the aorta and VSMCs was

evaluated using Alizarin Red S staining. Aortic rings were fixed in

4% polyoxymethylene for 1 h at room temperature, and cells for 20

min. After two PBS washes, both aortic rings and cells were stained

with 1% Alizarin Red solution for 10 min at room temperature,

followed by three additional PBS washes before imaging under a

light microscope. For von Kossa staining, aortic sections were

dewaxed, hydrated and treated with 1% silver nitrate under

ultraviolet light for 10 min. Calcified nodules were visualized as

brown to black under a light microscope or ELISPOT analyzer (CTL

ImmunoSpot® S6 Ultimate) following multiple washes. Data

analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.52a software.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

Following a 2-h baking period at 60°C to ensure

tissue adhesion, lesion sections underwent standard H&E

staining. Deparaffinization was performed through two 5-min xylene

immersions, followed by graded rehydration in absolute ethanol and

decreasing ethanol concentrations (95, 80 and 70%, 5 min each) and

three 2-min distilled water washes. Nuclear staining was achieved

via 5-min hematoxylin incubation, followed by running water

rinsing, brief acidic ethanol differentiation and a 5-min water

wash. Cytoplasmic staining employed 2-min eosin application with

subsequent water rinsing. Dehydration involved sequential 10-sec

immersions in 70, 80 and 90% ethanol, 5 min in absolute ethanol and

two final 5-min xylene clears before neutral resin mounting. All

procedures except the initial baking were conducted at 20-25°C.

Stained sections were examined using an Olympus VS200 automated

microscope.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Cells were lysed on ice for 15 min using RIPA buffer

containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and PMSF. After

centrifugation at 14,000 × g (15 min, 4°C), the resulting 40

μg supernatant was subjected to co-immunoprecipitation with

an anti-CaMKIIδ (GeneTex, Inc.; cat. no. GTX111401; 1:100) or

anti-RUNX2 antibody (Abcam; cat. no. ab236639; 1:100) or

anti-rabbit IgG (Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. SA00001-2;

1:1,000) overnight at 4°C. Protein A-conjugated agarose beads

(MilliporeSigma; cat. no. IP05; 40 μl) were then introduced,

followed by a 1-h incubation at 4°C with rotation. The beads

underwent six washes with chilled lysis buffer before resuspension

in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by heating

at 92°C for 3 min and separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel via

SDS-PAGE. Finally, CaMKII and RUNX2 levels were detected by

immunoblotting as previously described.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining

Aortic ring sections (7 μm) were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde 1 h at room temperature and incubated with TUNEL

reaction mixture (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C for

1 h in a light-protected environment. Nuclear staining was

performed using mounting medium with DAPI (Abcam; cat. no.

ab1041395) for 10 min at room temperature, ensuring light

protection throughout the procedure. A fluorescence microscope

(Leica DM6B; Leica Microsystems GmbH) was employed to capture

images at various magnifications, and TUNEL-positive cells were

counted from three randomly selected fields for each sample.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Each in

vitro experiment was repeated at least three times. Pearson's

correlation analysis coefficient was employed for correlation

analysis. Unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare the mean of

two groups. For comparisons across multiple groups, one-way ANOVA

with the Tukey's multiple comparisons test was applied. Data

analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.02 (Dotmatics).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

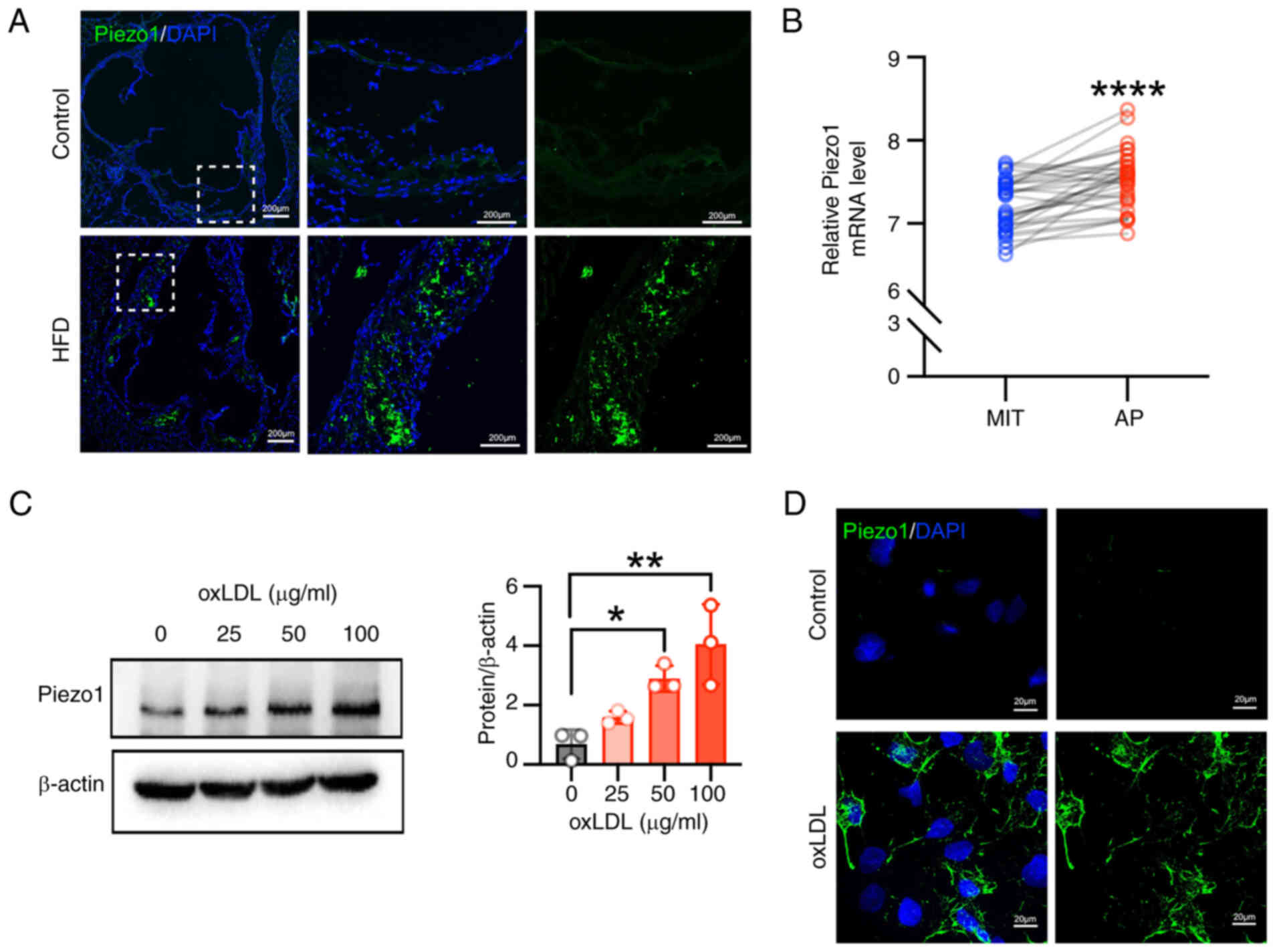

Piezo1 is upregulated in the

atherosclerotic plaques of mice and patients

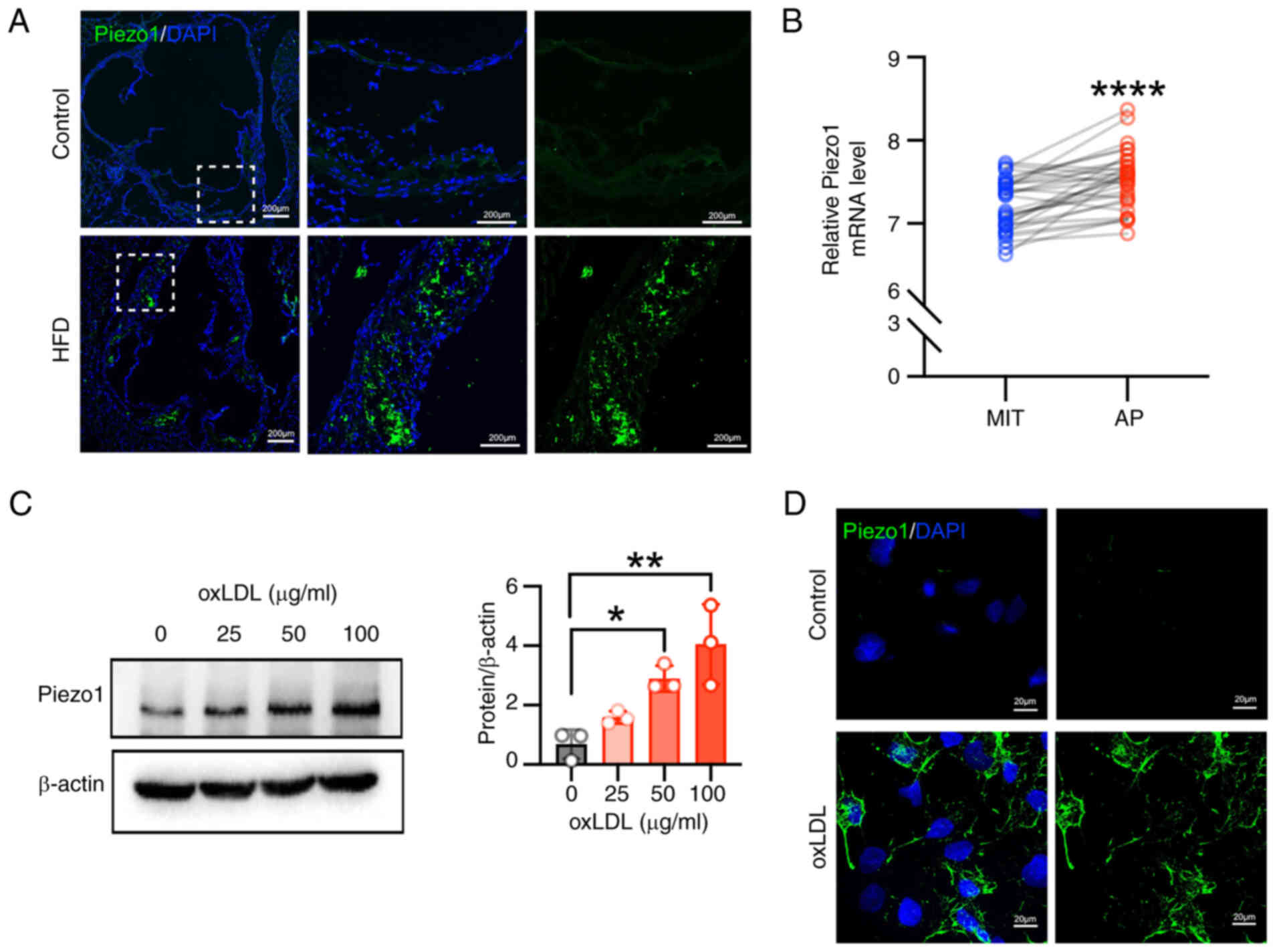

Vascular calcification frequently occurs within

atherosclerotic plaques (27).

To investigate the role of Piezo1 in this process, Piezo1

expression was examined in ApoE−/− mice subjected to a

high-fat diet, which induces atherosclerotic calcification

(28). Elevated Piezo1

expression was observed in both the necrotic core of

atherosclerotic plaques and the adjacent vascular wall (Fig. 1A). To corroborate this finding in

humans, data from the human carotid atheroma dataset (GSE43292) was

analyzed, revealing that Piezo1 expression was significantly higher

in atherosclerotic plaques compared with macroscopically intact

tissue (Fig. 1B). In addition,

primary VSMCs from mice were treated with ox-LDL at varying

concentrations, resulting in a dose-dependent increase in Piezo1

expression (Fig. 1C).

Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that Piezo1 expression was

upregulated and primarily localized on the cell membrane (Fig. 1D). These results suggest a

potential connection between Piezo1 and the progression of

atherosclerosis.

| Figure 1Piezo1 is upregulated in

atherosclerosis plaques in both patients and mice. (A)

Representative immunofluorescence stained images of aortic tissues

isolated from Apolipoprotein E−/− mice (scale bars, 200

μm). Piezo1 is shown in green and DAPI is shown in blue; n=6

rats per group. (B) Relative mRNA expression of Piezo1 in human

carotid samples (data from GEO dataset, GSE43292; paired t-test;

n=32); ****P<0.0001 vs. MIT. Statistical significance

of mRNA expression was assessed by paired Student's t-test (C)

VSMCs were treated with oxLDL for 24 h, and Piezo1 protein

expression was determined by western blot; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 vs. control. Statistical significance was

assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. (D) Representative

immunofluorescence stained images of Piezo1 (green) in VSMCs (scar

bar, 20 μm). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI

(blue). All values are presented as mean ± SD. AP, atheroma plaque;

MIT, macroscopically intact tissue; oxLDL, oxidized low-density

lipoprotein; HFD, high-fat diet; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle

cells. |

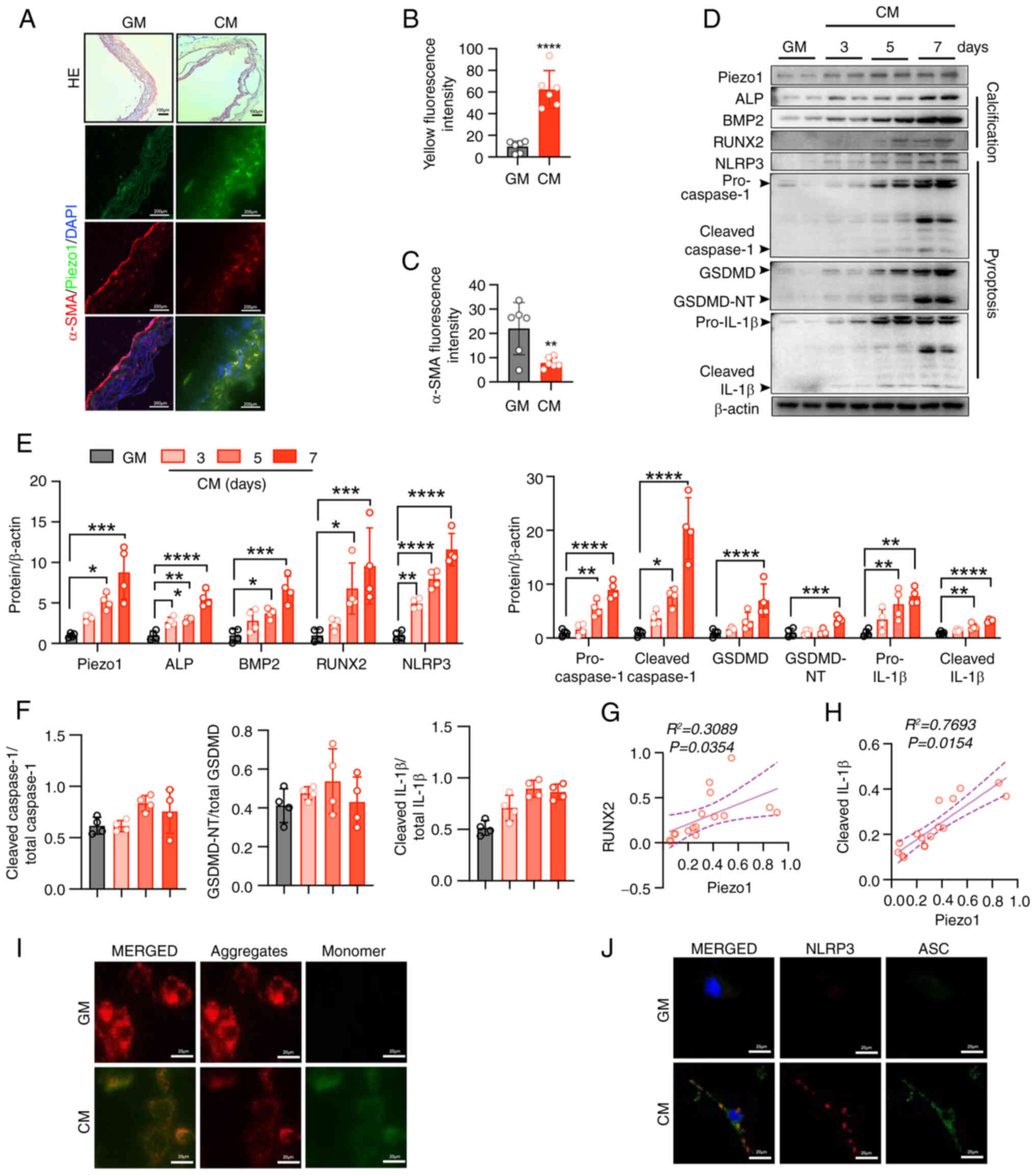

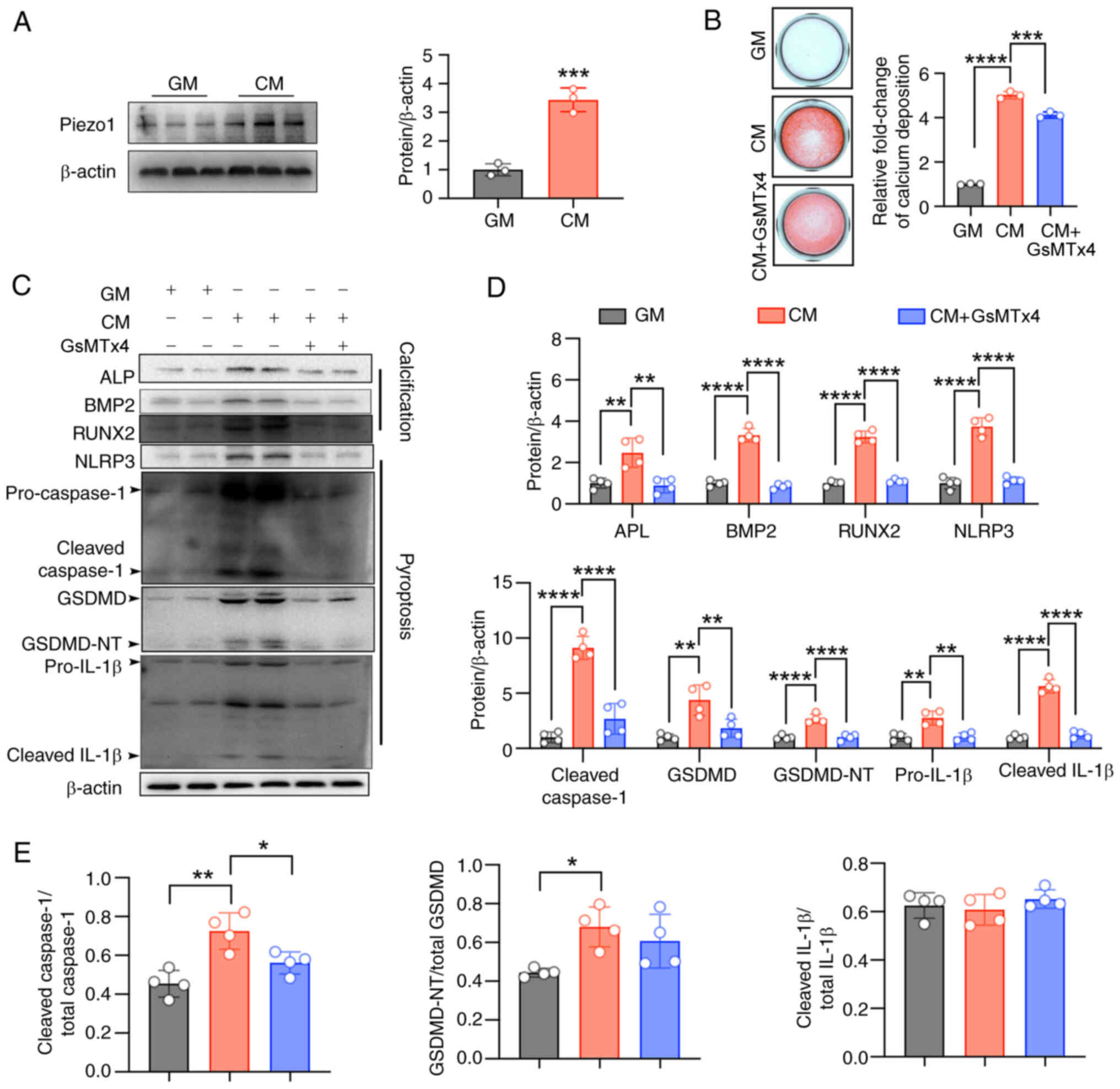

CM-induced osteogenic differentiation is

associated with Piezo1 expression, NLRP3 inflammasome activation

and pyroptosis in aortic ring and VSMCs

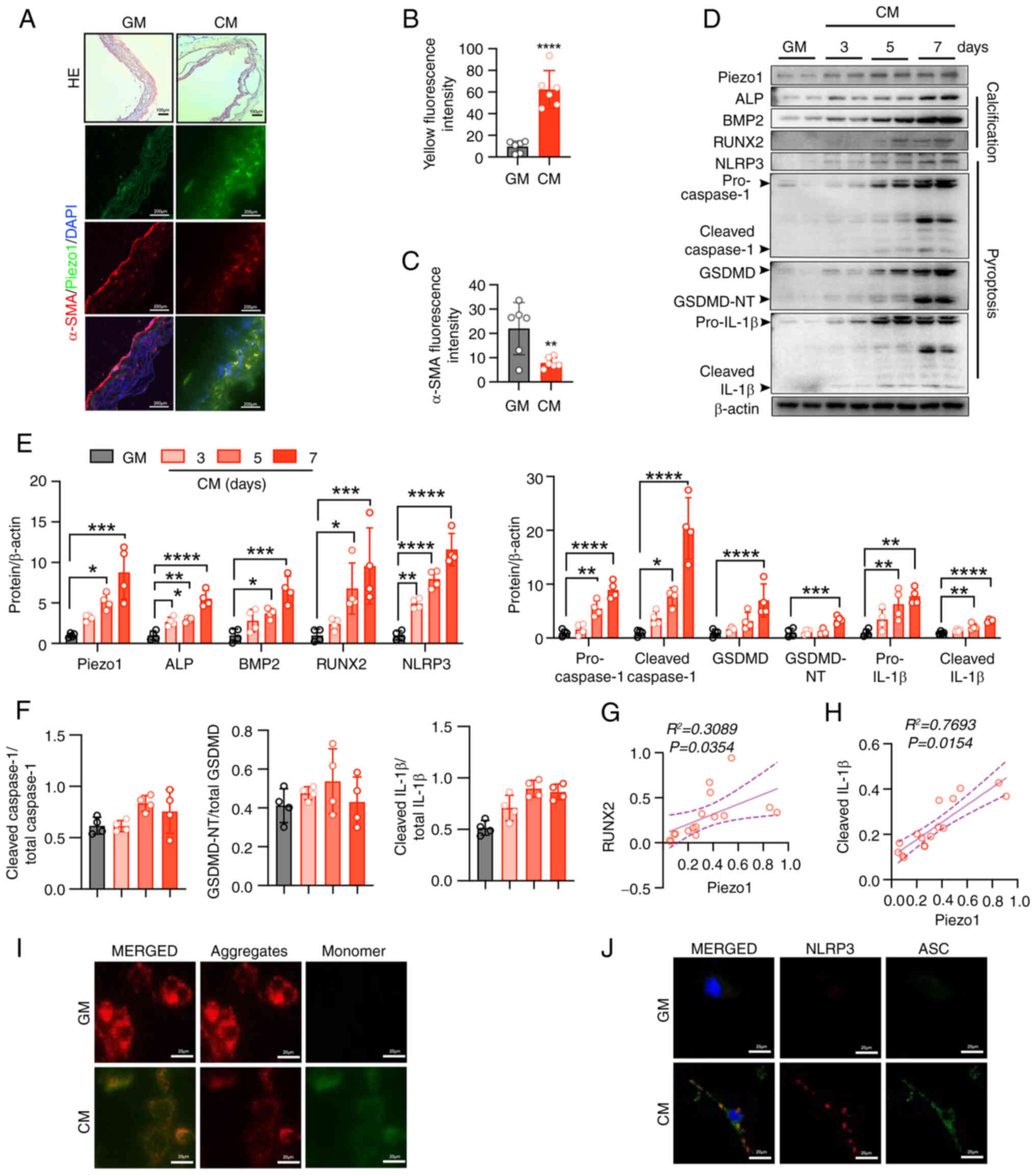

To further elucidate the role of Piezo1 in vascular

calcification, aortic rings were cultured in either GM or CM.

Exposure to CM over time compromised vascular integrity (Fig. 2A), coinciding with increased

Piezo1 expression and decreased α-SMA levels (Fig. 2A-C). Pyroptosis of plaque VSMCs,

a known contributor to plaque rupture and instability (29), was examined next. CM-induced

osteogenic differentiation in primary VSMCs was demonstrated by

increased expression of the osteogenic markers, ALP, BMP2 and

RUNX2, alongside elevated Piezo1 levels (Fig. 2D and E). Pyroptotic markers,

including cleaved caspase1, cleaved IL-1β and GSDMD-NT, were also

upregulated in CM-treated VSMCs (Fig. 2D-F). Notably, Piezo1 expression

showed a positive correlation with RUNX2 (R2= 0.3089; P=

0.0354; Fig. 2G) and IL-1β

(R2= 0.7693; P=0.0154; Fig. 2H), suggesting a potential link

between Piezo1 and both osteogenic differentiation and

inflammation. To further elucidate the mechanisms driving

calcification and pyroptosis, mitochondrial function was assessed.

CM treatment caused mitochondrial dysfunction in VSMCs, as

indicated by a disrupted MMP (Fig.

2I). Additionally, activated NLRP3 inflammasomes, marked by

NLRP3-ASC binding, were observed in VSMCs following CM exposure

(Fig. 2J). These results

indicate that CM promotes Piezo1 expression in a time-dependent

manner which may lead to pyroptosis in VSMCs, contributing to

vascular calcification.

| Figure 2CM-induced osteogenic differentiation

is associated with Piezo1 expression, NLRP3 inflammasome activation

and pyroptosis in the aortic ring and VSMCs. (A) Representative

H&E staining and immunofluorescence images alongside (B and C)

quantification of α-SMA and Piezo1 expression in the aortic

sections of mice (HE scale bars, 100 μm; immunofluorescence

scale bars, 200 μm); ****P<0.0001 vs. GM.

Statistical significance of mRNA expression was assessed by

unpaired Student's t-test (D-F) Representative immunoblot images

and semi-quantification of Piezo1, ALP, BMP2, RUNX2, NLRP3,

pro-caspase1, cleaved-caspase1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT, pro-IL-1β,

cleaved-IL-1β, cleaved caspase1/total-caspase1, GSDMD-NT/total

GSDMD and cleaved IL-1β/total IL-1β in mouse VSMC extracts. β-actin

was used as a loading control; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001 vs. GM. Statistical significance was

assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. Correlation analysis

between Piezo1 protein expression and the (G) RUNX2 and (H) IL-1β

level. Pearson's correlation analysis coefficient was employed for

correlation analysis. (I) MMP changes were monitored by

fluorescence using JC-1 staining. (J) Representative

immunofluorescence images of inflammasome marker NLRP3 and ASC

expression in the VSMCs of mice. Scale bars, 10 μm; n=3

independent experiments; ***P<0.001 vs. GM. All

values are presented as mean ± SD. CM, calcifying medium; GM,

growth medium; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein

domain-containing protein 3; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells;

α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BMP2, bone

morphogenetic protein 2; RUNX2, runt-related transcription factor

2; GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, gasdermin D N-terminal; IL-1β,

interleukin-1β; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; ASC,

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase

recruitment domain. |

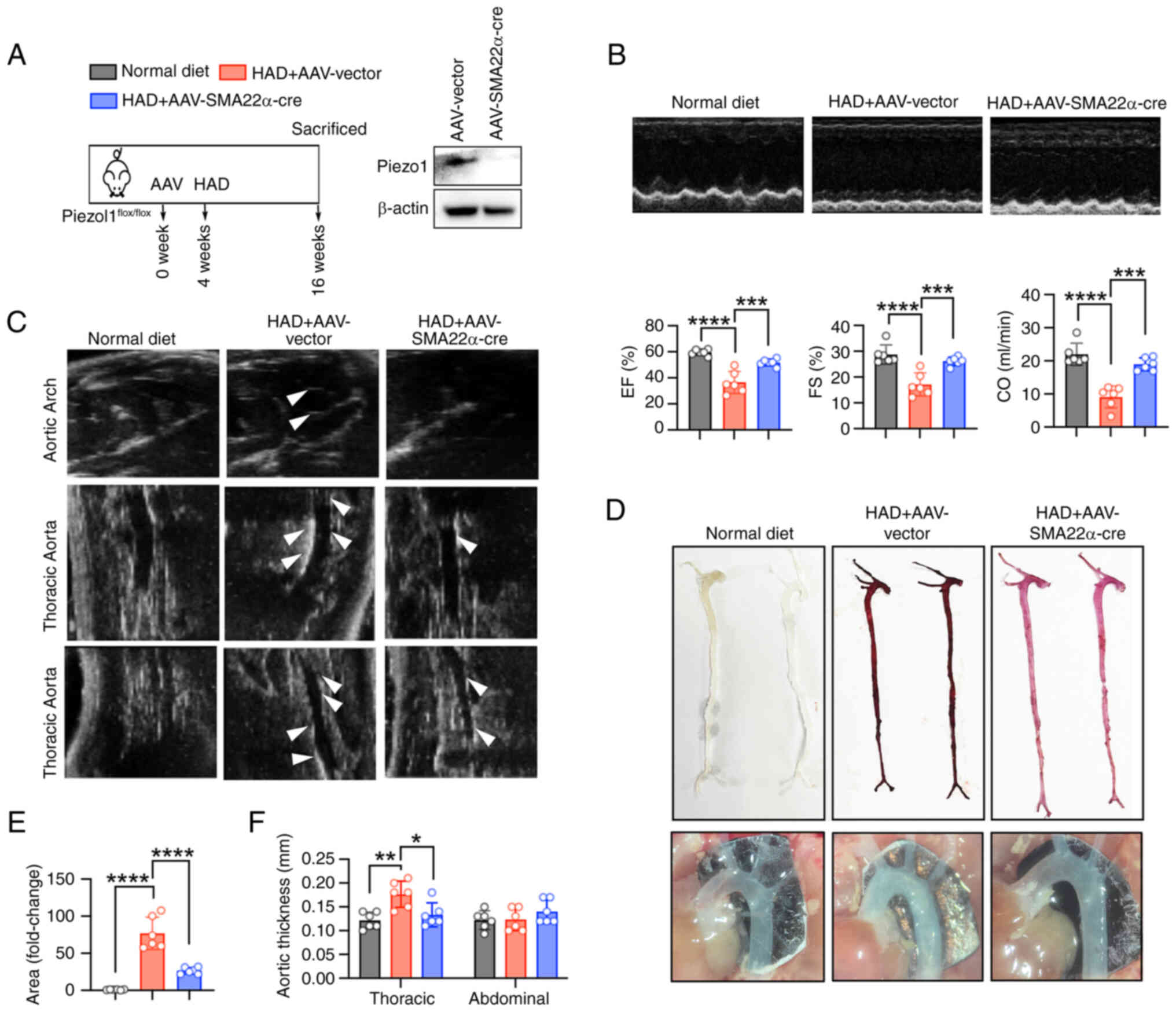

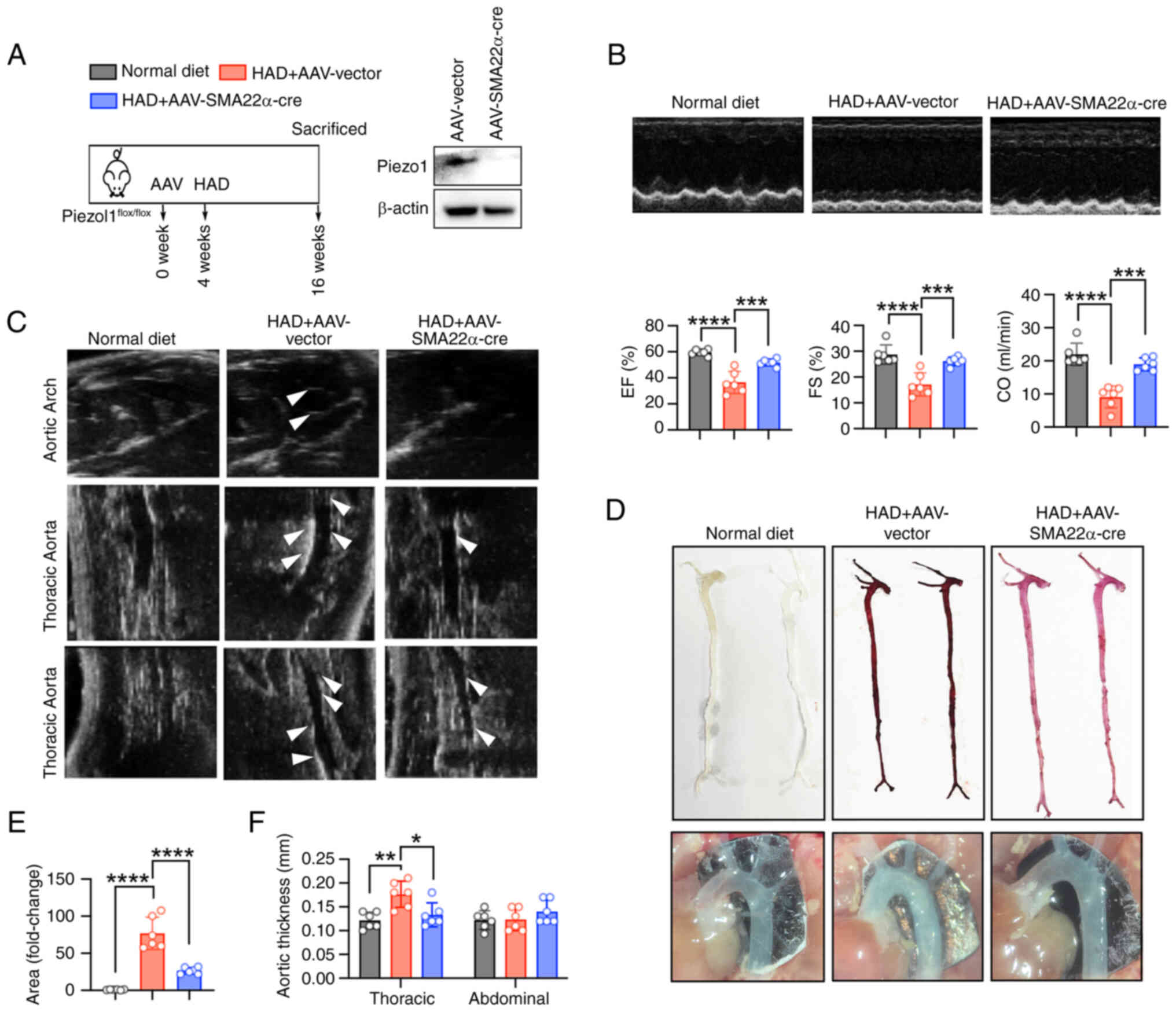

VSMC-specific knockout of Piezo1

alleviates arterial calcification in mice

To further explore the involvement of Piezo1 in

arterial calcification, VSMC-specific Piezo1 knockout mice were

generated by administering AAV-SM22α-Cre to

Piezo1flox/flox mice, followed by an HAD to induce

vascular calcification (Fig.

3A). HAD significantly impaired cardiac function, which was

mitigated in the Piezo1 knockout group (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the knockout of

Piezo1 in VSMCs attenuated HAD-induced aortic calcification, as

demonstrated by M-mode echocardiography of the thoracic and

abdominal aorta (Fig. 3C).

Alizarin Red staining further confirmed the reduction in

HAD-induced calcium deposition in the knockout mice (Fig. 3D and E). Notably, VSMC-specific

Piezo1 knockout resulted in increased aortic lumen thickness

(Fig. 3F). Collectively, these

results suggest that Piezo1 deficiency in VSMCs inhibits arterial

calcification and improves cardiac function.

| Figure 3Specific knockout of Piezo1 in VSMCs

alleviates arterial calcification in mice. (A) Schematic

representation of the arterial calcification in vivo

protocol. (B) Representative echocardiographic recordings revealed

that HAD induced cardiac dysfunction in VSMC-specific Piezo1

knockout mice (generated via AAV-SMA22α-cre). Cardiac dysfunction

was evaluated using echocardiographic parameters including EF, FS

and CO; ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. (C)

Representative 2D B-mode images from the in vivo ultrasound

scanning of the aortic arch, thoracic aorta and abdominal aorta.

White arrows indicate vascular calcifications. (D and E)

Representative images of Alizarin red staining revealed that a

HAD-induced calcium deposition in the aorta (reddish signal) of

VSMC-specific Piezo1 knockout mice. The whole-aorta analysis

further confirmed calcification extent; ****P<0.0001.

(F) Recorded aortic thickness; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01. Statistical significance was assessed by

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. All values are presented as mean

± SD. AAV, adeno-associated virus; HAD, high-adenine diet; w,

weeks; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fraction shortening; CO, cardiac

output; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells. |

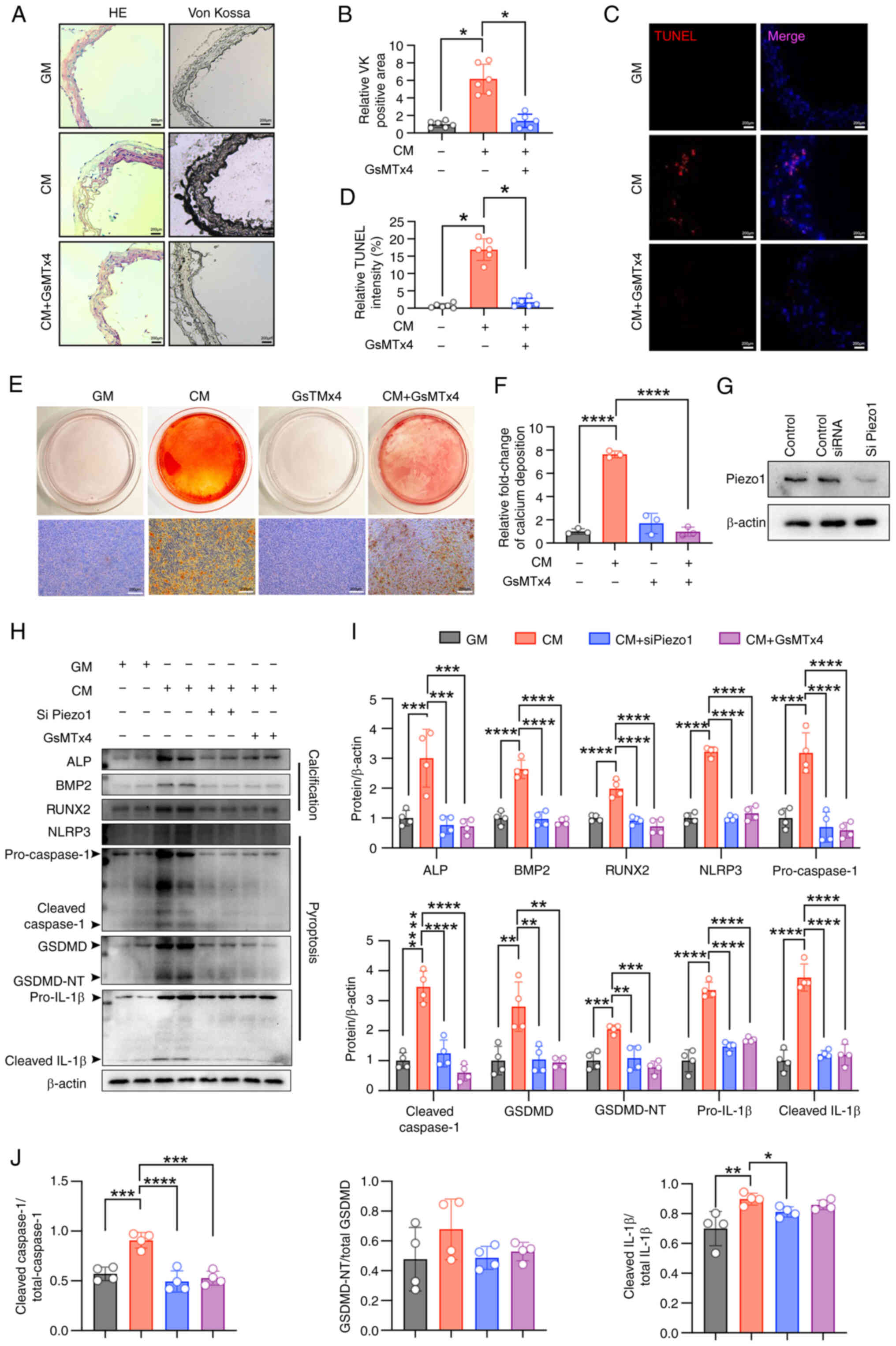

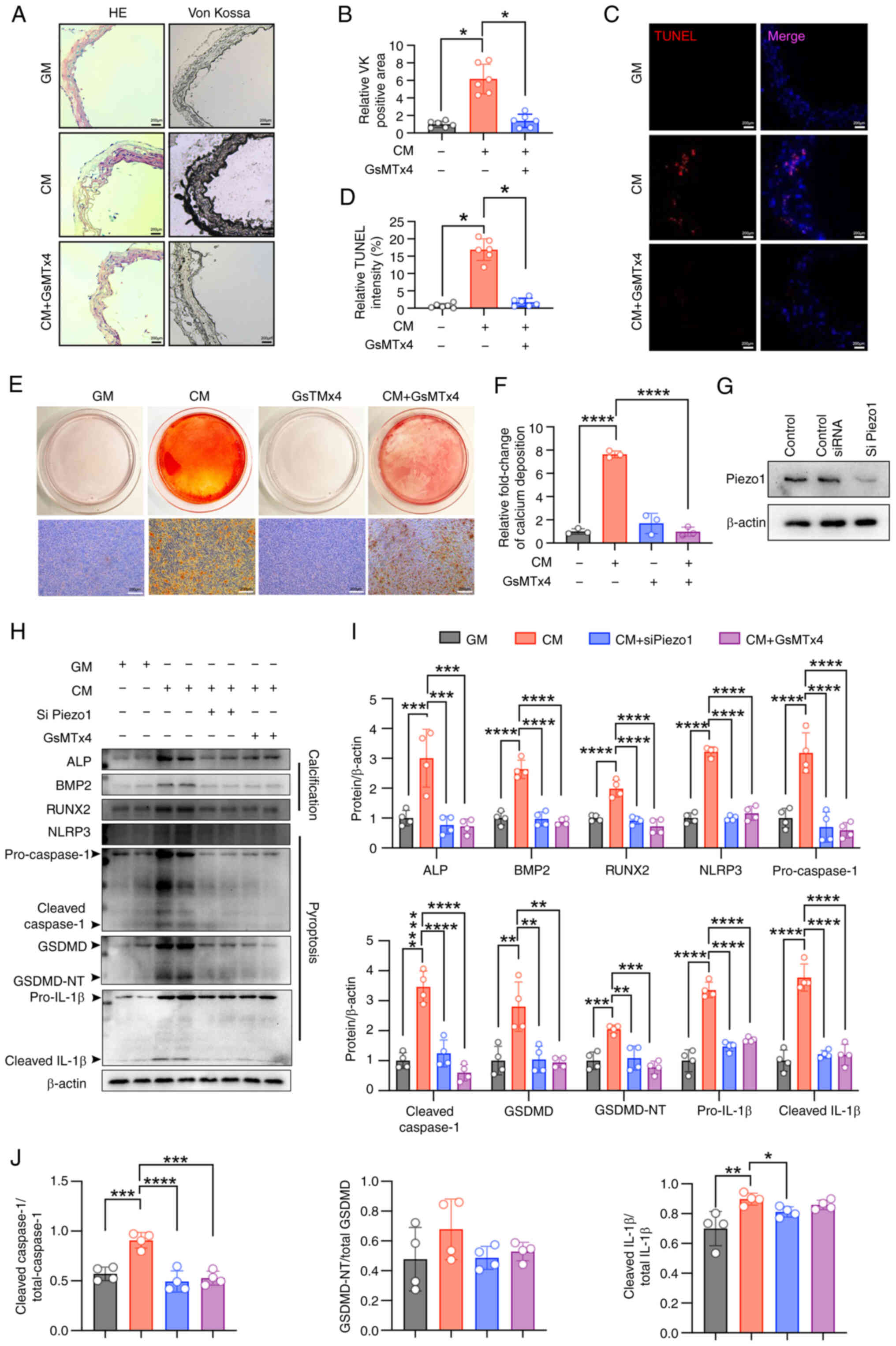

Piezo1 inhibition blocks CM-induced NLRP3

inflammasome activation and pyroptosis and alleviates

calcification

Von Kossa staining showed that CM-induced vascular

calcification and structural damage in cultured aortic rings, which

was alleviated by the Piezo1-specific inhibitor, GsMTx4 (5

μM) (Fig. 4A and B).

Given the role of VSMC death in vascular calcification (30), TUNEL staining was performed to

assess cell death in the cultured cells. Calcifying conditions

significantly increased cell death, which was reduced by GsMTx4

(Fig. 4C and D). Alizarin Red S

staining also confirmed that Piezo1 inhibition reduced calcium

deposition in VSMCs (Fig. 4E and

F). Moreover, CM treatment led to increased expression of the

osteogenic markers, ALP, BMP2 and RUNX2, which were significantly

inhibited by either Piezo1 inhibitor or Piezo1 siRNA (Fig. 4G-J). Similarly, CM-induced

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in VSMCs was

blocked by Piezo1 inhibition or knockdown (Fig. 4G-I). These results confirm that

Piezo1 plays a key role in VSMC osteogenic differentiation, with

its effects closely linked to NLRP3 inflammasome activation and

pyroptosis.

| Figure 4Piezo1 inhibition blocks CM-induced

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis and alleviates

calcification. (A and B) Representative HE staining, Von Kossa

staining and quantification of the Von Kossa positive area in the

aortic sections of mice (scale bars, 200 μm);

*P<0.05. (C and D) TUNEL staining analysis was used

to evaluate cell death (scale bars, 200 μm);

*P<0.05. (E and F) Representative images of Alizarin

red S staining showing calcium nodule formation (reddish signal) in

VSMCs cultured with GM/CM under Piezo1 inhibitor treatment (scale

bars, 200 μm); ****P<0.0001; n=3 independent

experiments. (G-J) Representative immunoblot images of Piezo1, ALP,

BMP2, RUNX2, NLRP3, pro-caspase1, cleaved-caspase1, GSDMD,

GSDMD-NT, pro-IL-1β, cleaved-IL-1β, cleaved

caspase1/total-caspase1, GSDMD-NT/total GSDMD and cleaved

IL-1β/total IL-1β in mouse VSMC extracts. β-actin was used as a

loading control. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. Statistical significance was assessed

by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. All values are presented as

mean ± SD. CM, calcifying medium; GM, growth medium; VK, von kossa;

TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end

labeling; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells; ALP, alkaline

phosphatase; BMP2, bone morphogenetic protein 2; RUNX2,

runt-related transcription factor 2; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor

thermal protein domain-containing protein 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

GSDMD-NT, gasdermin D N-terminal; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; siRNA,

small interfering RNA. |

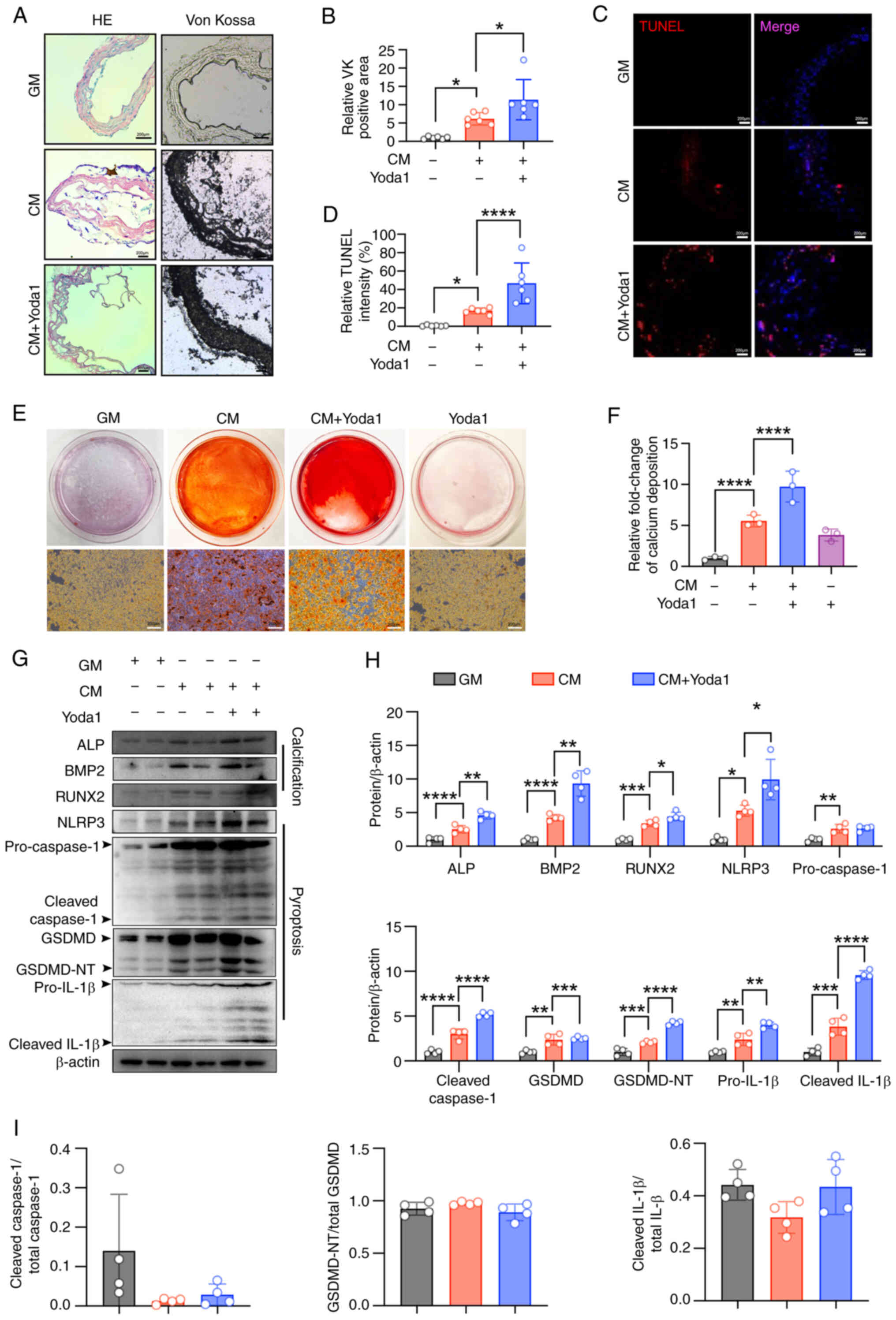

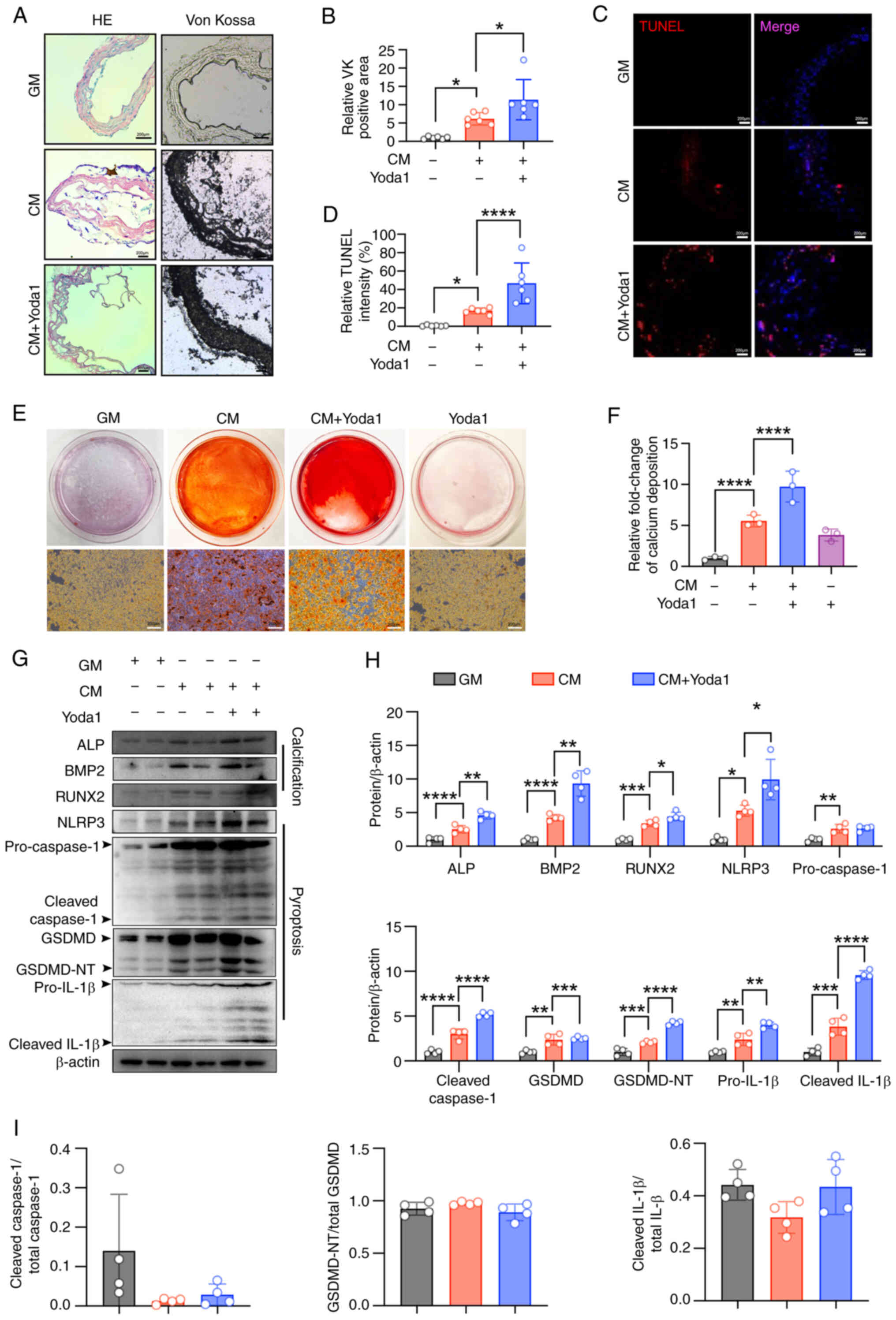

Piezo1 activator promotes CM-induced

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis and enhances

calcification

To further clarify the role of Piezo1 in the

osteogenic differentiation of VSMCs, Piezo1 was activated using

Yoda1 (30 μM), which enhanced calcium deposition. Yoda1

significantly promoted CM-induced calcium deposits in aortic rings

(Fig. 5A and B). Additionally,

calcifying conditions increased cell death, which was exacerbated

by Yoda1 (Fig. 5C and D).

Alizarin Red S staining confirmed that Yoda1 further enhanced

CM-induced calcium deposition in VSMCs (Fig. 5E and F). Consistently, Yoda1

increased the expression of the osteogenic markers, ALP and BMP2,

and promoted NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis (Fig. 5G-I). These results further

demonstrate that Piezo1 may be a critical modulator of VSMC

osteogenic differentiation and vascular calcification, with its

activity being associated with inflammasome activation and

pyroptosis.

| Figure 5Piezo1 activator promotes CM-induced

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis and enhances

calcification. (A and B) Representative HE staining, Von Kossa

staining and quantification of the Von Kossa positive area in the

aortic sections of mice (scale bars, 200 μm);

*P<0.05. (C and D) TUNEL staining analysis was used

to evaluate cell death (scale bars, 200 μm);

*P<0.05, ****P<0.0001. (E and F)

Calcium deposition was visualized by Alizarin red S staining at the

light microscopic level (scale bars, 200 μm);

****P<0.0001; n=3 independent experiments. (G-I)

Representative immunoblot images of Piezo1, ALP, BMP2, RUNX2,

NLRP3, pro-caspase1, cleaved-caspase1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT, pro-IL-1β,

cleaved-IL-1β, cleaved caspase1/total-caspase1, GSDMD-NT/total

GSDMD and cleaved IL-1β/total IL-1β in mouse VSMC extracts. β-actin

was used as a loading control. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. Statistical significance was assessed

by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. All values are presented as

mean ± SD. CM, calcifying medium; GM, growth medium; VK, von kossa;

TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end

labeling; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BMP2, bone morphogenetic

protein 2; RUNX2, runt-related transcription factor 2; NLRP3,

NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain-containing protein 3;

GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, gasdermin D N-terminal; IL-1β,

interleukin-1β; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells. |

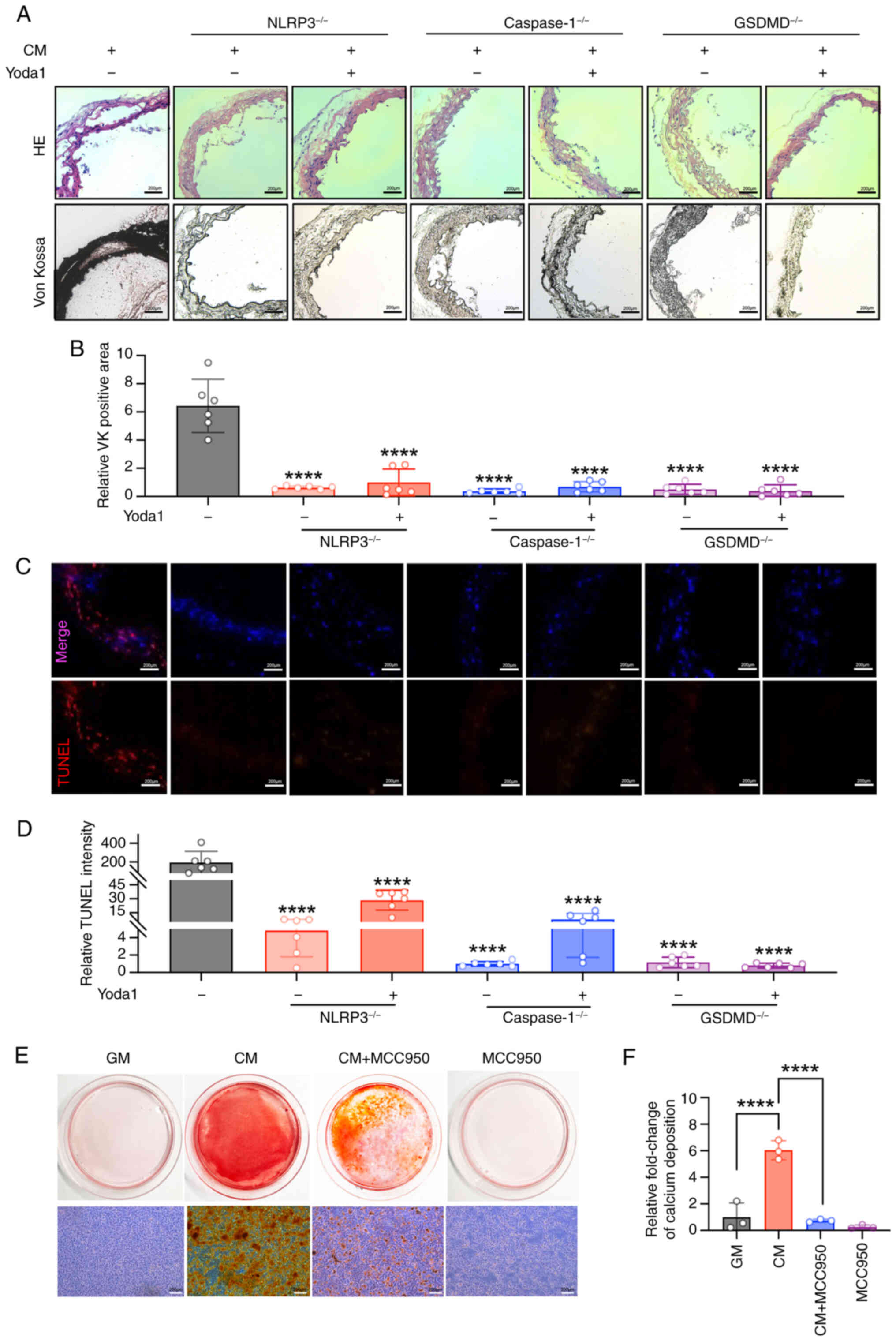

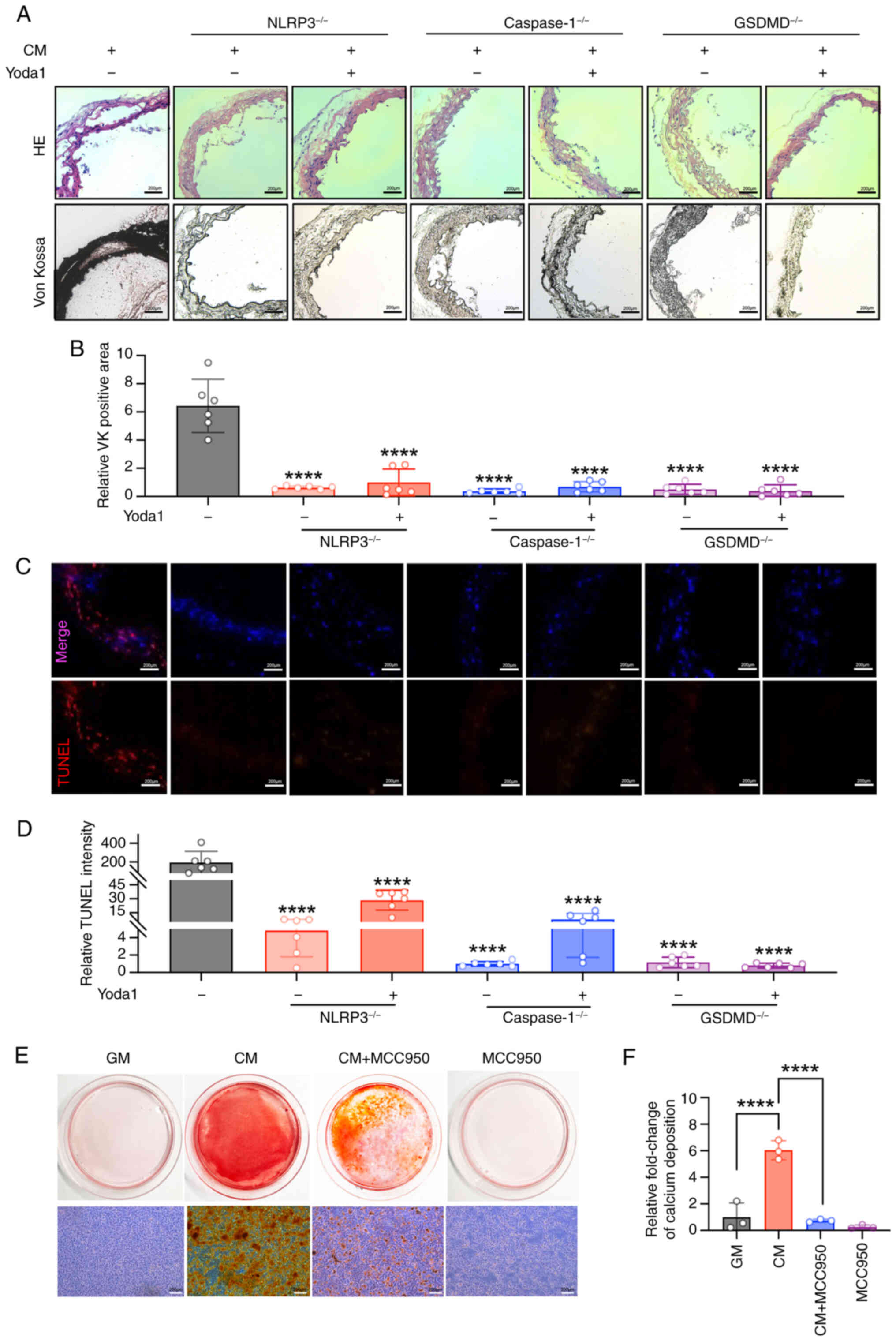

NLRP3, caspase1 or GSDMD deletion

inhibits CM-induced calcification with/without Piezo1 agonist

To investigate the specific role of NLRP3

inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in arterial calcification,

aortic rings from NLRP3−/−, caspase1−/− and

GSDMD−/− mice were treated with CM in the presence or

absence of the Piezo1 activator, Yoda1. Notably, CM-induced

arterial calcification was significantly suppressed by the deletion

of NLRP3, caspase1 or GSDMD, even when Yoda1 was present in the

medium (Fig. 6A and B). TUNEL

staining also revealed that the deletion of these genes reduced

cell death in CM-cultured aortic rings, despite Yoda1 treatment

(Fig. 6C and D). Moreover, the

NLRP3-specific inhibitor, MCC950, effectively blocked CM-induced

calcium nodule formation and calcium deposition in VSMCs (Fig. 6E and F). These results suggest

that NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis may be key

contributors to Piezo1-mediated arterial calcification.

| Figure 6NLRP3, caspase1 or GSDMD deletion

inhibits CM-induced calcification with/without Piezo1 agonist. (A

and B) Representative HE staining, Von Kossa staining and

quantification of the Von Kossa positive area in the aortic

sections of NLRP3−/−, caspase1−/− and

GSDMD−/− mice (scale bars, 200 μm);

****P<0.0001 vs. CM. (C and D) TUNEL staining

analysis was used to evaluate cell death (scale bars, 200

μm); ****P<0.0001 vs. CM. (E and F) Calcium

deposition in VSMCs was visualized by Alizarin red S staining at

the light microscopic level (scale bars, 200 μm);

****P<0.0001. Statistical significance was assessed

by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. All values are presented as

mean ± SD. CM, calcifying medium; GM, growth medium; VK, von kossa;

TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end

labeling; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein

domain-containing protein 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D; VSMC, vascular

smooth muscle cells. |

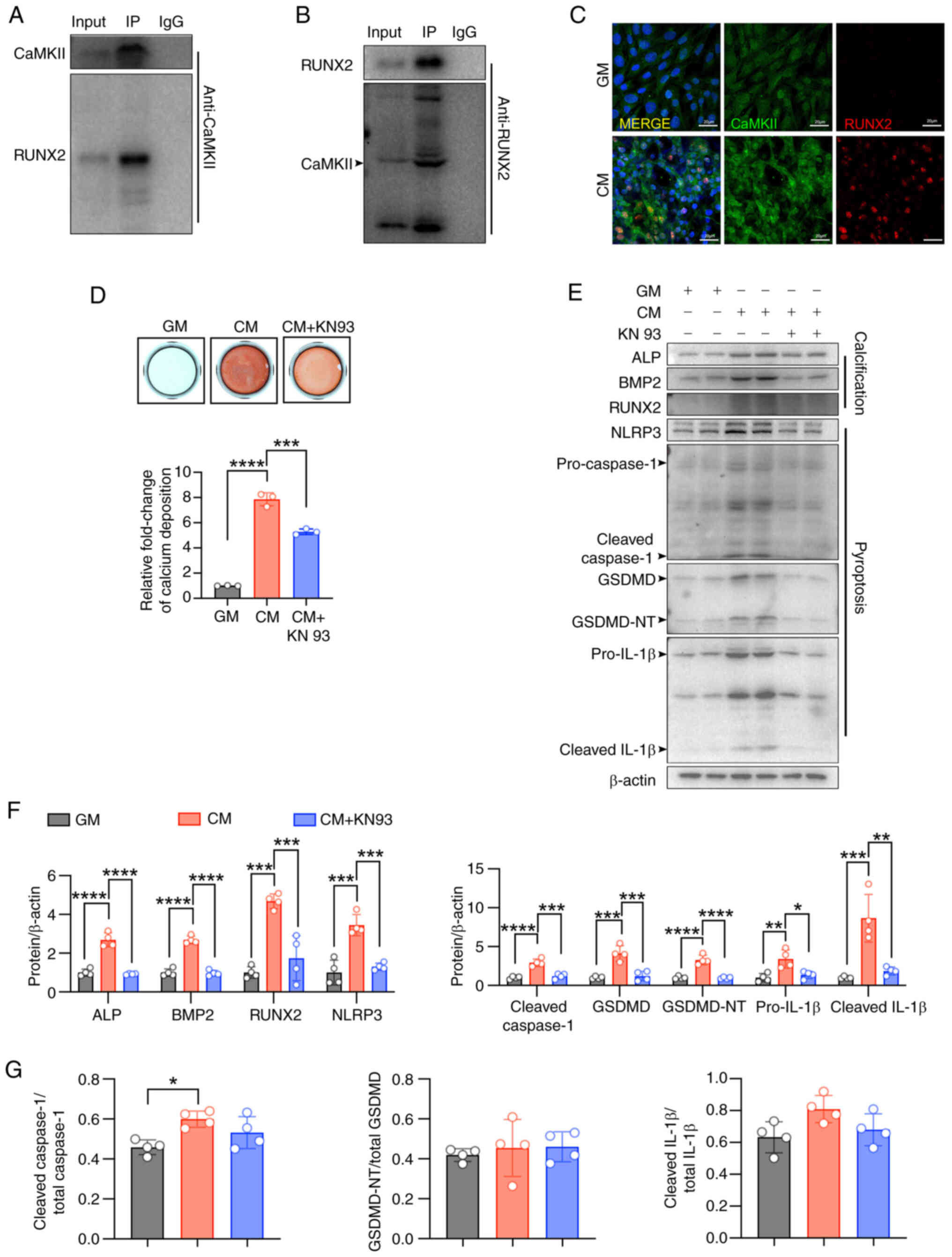

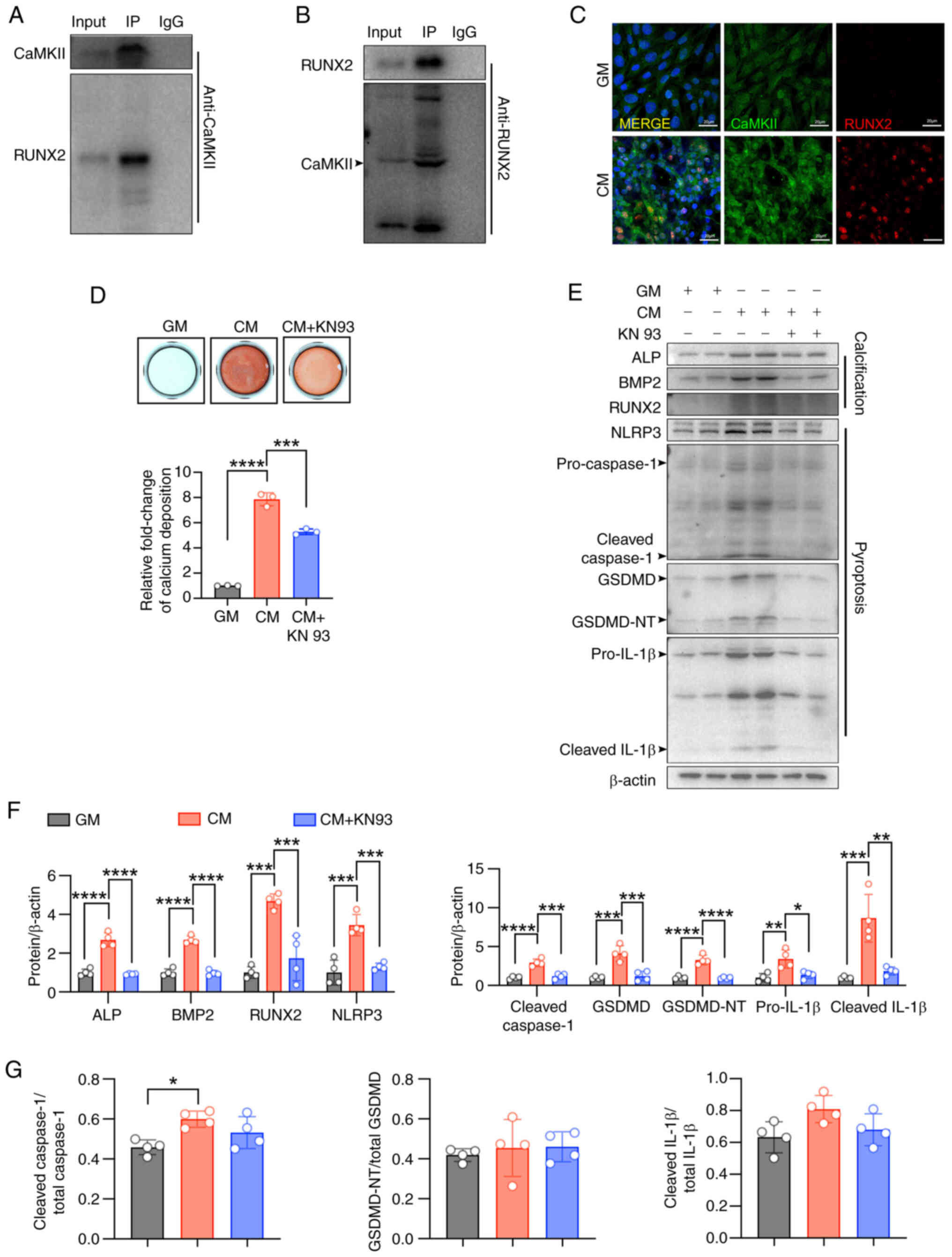

CaMKII promotes CM-induced calcium

deposits via binding to RUNX2 in VSMCs

To further explore the downstream mechanisms of

Piezo1 in arterial calcification, the interaction between Piezo1

and transcription factors involved in osteoblast mineralization was

examined. It has been reported that Ca2+/calmodulin

signaling regulates RUNX2 activity, a critical mediator in

osteoblast differentiation (31,32), suggesting a

Ca2+-dependent regulatory pathway in vascular

calcification. Hence, the interaction between CaMKII and RUNX2 in

Piezo1-mediated VSMC osteogenic transition was investigated in the

present study. Immunoprecipitation confirmed that CaMKII directly

interacts with RUNX2 (Fig. 7A and

B), and immunofluorescence demonstrated that CM treatment

promoted the co-localization of CaMKII and RUNX2 in VSMCs (Fig. 7C). Alizarin Red S staining also

showed that KN93 reduced CM-induced calcium nodule formation and

calcium deposition in VSMCs (Fig.

7D). Furthermore, inhibition of CaMKII with KN93 significantly

alleviated CM-induced pyroptosis and the expression of osteogenic

markers in VSMCs (Fig. 7E-G).

These results suggest that activated CaMKII binding to RUNX2 may

play a pivotal role in modulating VSMC differentiation into

osteoblast-like cells.

| Figure 7CaMKII promotes CM-induced calcium

deposits via binding RUNX2 in VSMCs. (A and B)

Co-immunoprecipitation of CaMKII with RUNX2 in VSMCs. (C)

Representative immunofluorescence images of CaMKII and RUNX2 in

VSMCs (scale bars, 20 μm). (D) Calcium deposition of VSMCs

was visualized in 24-well plate by Alizarin red S staining at the

light microscopic level; ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. (E-G) Representative immunoblot images

of Piezo1, ALP, BMP2, RUNX2, NLRP3, pro-caspase1, cleaved-caspase1,

GSDMD, GSDMD-NT, pro-IL-1β, cleaved-IL-1β, cleaved

caspase1/total-caspase1, GSDMD-NT/total GSDMD and cleaved

IL-1β/total IL-1β in mouse VSMC extracts. β-actin was used as a

loading control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Statistical

significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. All

values are presented as mean ± SD. CM, calcifying medium; GM,

growth medium; CaMKII, calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase

II; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells; IP, immunoprecipitation;

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BMP2, bone morphogenetic protein 2;

RUNX2, runt-related transcription factor 2; NLRP3, NOD-like

receptor thermal protein domain-containing protein 3; GSDMD,

gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, gasdermin D N-terminal; IL-1β,

interleukin-1β. |

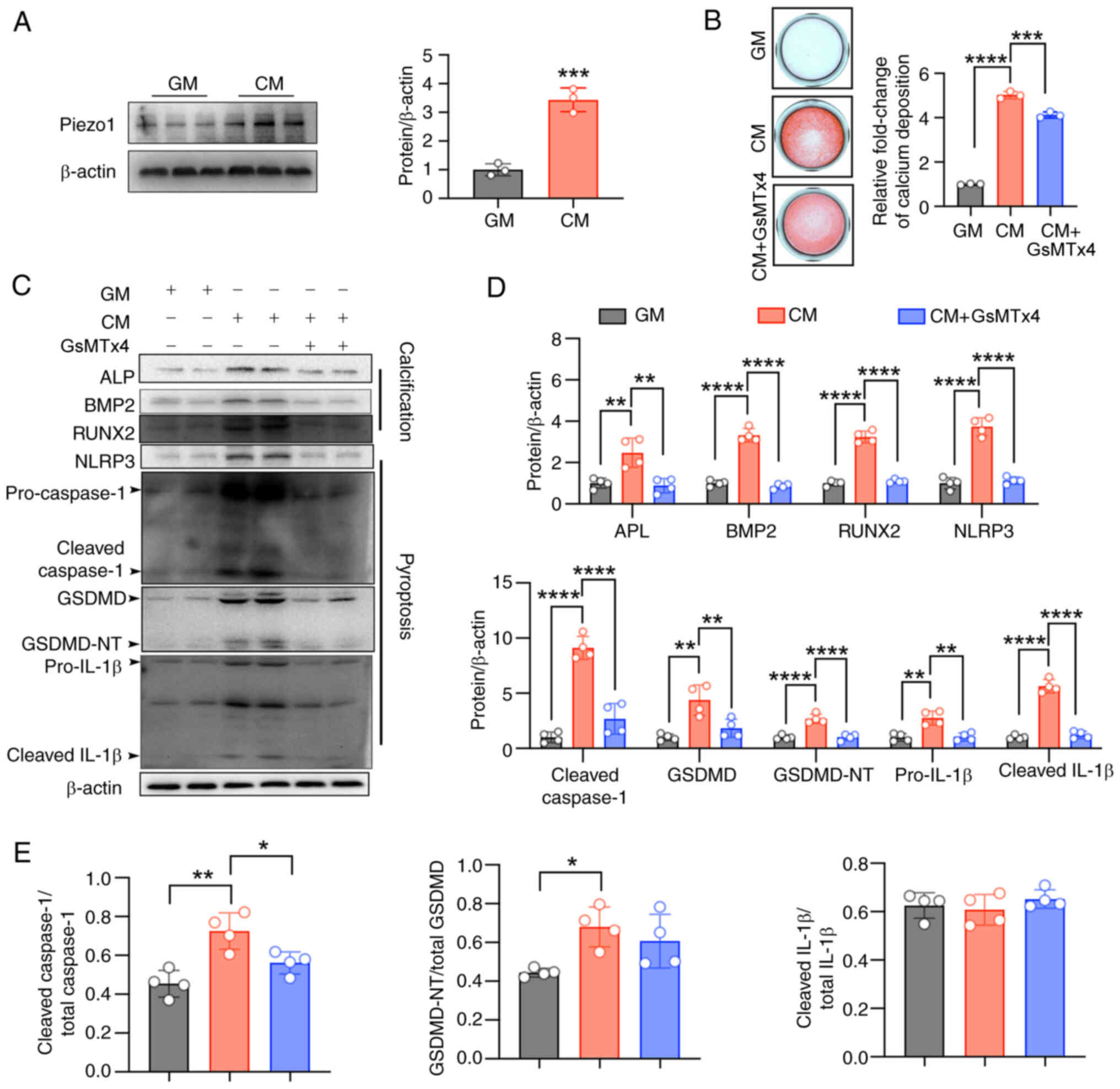

Piezo1 inhibition alleviates HASMC

differentiation into osteoblasts

Consistent with the findings in VSMCs, CM treatment

also increased Piezo1 expression, activated the NLRP3 inflammasome

and induced pyroptosis in HASMCs (Fig. 8A and C-E). In parallel,

CM-treated HASMCs exhibited significantly elevated expression of

the osteoblast differentiation markers, ALP, BMP2 and RUNX2

(Fig. 8C and D). Notably, these

effects were significantly inhibited by the Piezo1 inhibitor,

GsMTx4 (Fig. 8C-E). Alizarin Red

S staining further confirmed that Piezo1 inhibition abolished

CM-induced calcium nodule formation and calcium deposition in

HASMCs (Fig. 8B). Collectively,

these results confirm that Piezo1 activation may promote osteogenic

differentiation and calcification in HASMCs through NLRP3

inflammasome activation and pyroptosis.

| Figure 8Piezo1 inhibition alleviates HASMC

differentiation into osteoblasts. (A) Representative immunoblot

images of Piezo1 in HASMC extracts. β-actin was used as a loading

control; ***P<0.001. Statistical significance of mRNA

expression was assessed by unpaired Student's t-test (B) Calcium

deposition of HASMCs was visualized in 24-well plate by Alizarin

red S staining at the light microscopic level;

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. (C-E)

Representative immunoblot images of Piezo1, ALP, BMP2, RUNX2,

NLRP3, pro-caspase1, cleaved-caspase1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT, pro-IL-1β,

cleaved-IL-1β, cleaved caspase1/total-caspase1, GSDMD-NT/total

GSDMD and cleaved IL-1β/total IL-1β in HASMCs extracts. β-actin was

used as a loading control; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. Statistical

significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's. All

values are presented as mean ± SD. HASMC, human aortic smooth

muscle cells; CM, calcifying medium; GM, growth medium; ALP,

alkaline phosphatase; BMP2, bone morphogenetic protein 2; RUNX2,

runt-related transcription factor 2; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor

thermal protein domain-containing protein 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

GSDMD-NT, gasdermin D N-terminal; IL-1β, interleukin-1β. |

Discussion

In the present study, the detrimental role of Piezo1

in arterial calcification was identified. To the best of our

knowledge, the present study is the first to report that depletion

of Piezo1 in VSMCs effectively protected mice from developing

arterial calcification. Additionally, in vitro experiments

demonstrated that Piezo1 activation significantly contributed to

IL-1β expression and pro-inflammatory cell death (pyroptosis),

which subsequently drove VSMC calcification. Mechanistically, the

present study provided the first evidence that the downstream

effector of Piezo1, CaMKII, initiated inflammasome assembly and

pyroptosis, leading to VSMC calcification. Simultaneously, CaMKII

interacted with RUNX2, promoting the expression of osteogenic

proteins. These novel findings highlight Piezo1 as a promising

therapeutic target for arterial calcification by regulating VSMC

pyroptosis. Notably, aberrant Piezo1-induced vascular pyroptosis

and calcification were reversed by Piezo1 inhibition, whether

through pharmacological or genetic approaches.

It is well-established that shear stress and tissue

stiffness are the primary factors driving Piezo1 activation through

mechanosensation (33,34). In human fibroatheromas,

microcalcifications >5 μm have been shown to increase

peak circumferential stress by 2-7 times (35). The present study, along with

others, has reported elevated Piezo1 expression in both human and

murine atherosclerotic plaques (36) and calcified vessels (37), which leads to vascular

inflammation (38). It has been

demonstrated that VSMCs in the fibrous caps of microcalcifications

undergo calcification via Piezo1 activation in response to

mechanical stimuli such as tissue stiffness, shear stress and

extracellular pressure (39).

Notably, the results of the present study also revealed that Piezo1

could be activated independently of mechanical forces, with

elevated expression observed under high calcium/phosphate

conditions.

The findings of the present study, alongside

previous research, underscore the role of ion channels in the

osteogenic transition of VSMCs and arterial calcification (40,41). In the present study, it was

observed that CM induced Piezo1 upregulation and calcification in a

time-dependent manner, with CM-induced calcification showing a

synergistic effect with Piezo1 activation. This synergistic

interaction, supported by the increased expression of osteogenic

markers and a previous study (37), helps to explain the strong

correlation between pulse pressure, isolated systolic hypertension

and calcified atherosclerosis (42). Thus, Piezo1 activation is

essential for arterial calcification.

Previous studies have demonstrated that

Piezo1-mediated processes, such as cell death and division, play

critical roles in biological functions and disease progression

(17,43,44). To the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to reveal that Piezo1 activation induces

pyroptosis in VSMCs and drives inflammasome activation during

CM-induced cell death and osteogenic differentiation.

Piezo1-induced inflammasome assembly appears to function in

parallel with the canonical pathway, in which NLRs and AIM2-like

receptors detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns and DAMPs,

triggering the assembly of a caspase1-activating complex (45). In line with the established role

of Piezo1 as a calcium-dependent mechanotransducer (46), Piezo1-induced signaling,

particularly via CaMKII, under conditions of calcium-phosphate

dysregulation, is a significant mechanism leading to VSMC

pyroptosis.

The findings of the present study and previous

research (30) provide strong

evidence that NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis in VSMCs is a pivotal

event in arterial calcification. While previous research emphasized

VSMC apoptosis as a driver of calcification (47,48), recent consensus highlights

pyroptosis and phenotypic switching, including the transition to

osteochondrogenic cells, as central mechanisms in arterial

calcification and atherosclerotic plaque instability (10,49). Given that TUNEL staining, which

detects DNA fragmentation, cannot distinguish between apoptosis and

pyroptosis (50), additional

evidence from GSDMD, caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage in the present

study demonstrated that pyroptosis was the predominant cause and a

key upstream event in the calcification process. Notably, genetic

deletion of inflammasome components (NLRP3−/−,

caspase1−/− and GSDMD−/−) in mice prevented

CM-induced calcification and cell death of the isolated aortic

rings, while NLRP3 inhibition significantly reversed CM-induced

calcification. This supports the independent roles of NLRP3 and

caspase1 in mediating cell death, as their deletion inhibited both

cell death and arterial calcification. Furthermore, the results of

the present study support that GSDMD cleavage is critical for

pyroptotic cell death, with GSDMD deletion also blocking

calcification. Given the established link between inflammatory

cytokines and vascular calcification, it is plausible that

pyroptosis, through the release of VSMC-derived cytokines, serves

as the key upstream event mediating CM-induced calcification.

Notably, the mechanisms driving intimal calcification in

atherogenesis may differ from those underlying medial calcification

in chronic renal failure.

The findings of the present study strongly support

that Piezo1-CaMKII signaling activation is a critical upstream

event in CM-induced pyroptosis and calcification, as inhibition of

Piezo1 or CaMKII significantly reversed these processes. CaMKII, as

a downstream effector of Piezo1, plays a central role in initiating

inflammasome activation and is largely responsible for CM-induced

pyroptosis and calcification (37,51). The partial rescue effect observed

with CaMKII inhibition could be attributed to its incomplete

suppression of CaMKII activity, suggesting the possibility of NLRP3

inflammasome activation via a TLR-independent pathway (52). Furthermore, to the best of our

knowledge, the present study provides the first evidence of the

binding between CaMKII and RUNX2, reinforcing the conclusion that

CaMKII is a key upstream regulator of RUNX2-induced osteoblast

differentiation (53,54). However, further research is

needed to determine the exact effect of RUNX2-induced osteogenic

reprogramming on pyroptosis.

Two major conclusions of the present study are

proposed. First, the present study provides the first evidence that

Piezo1 activation contributes to high calcium/phosphate-induced

calcification in VSMCs. Second, NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated

pyroptosis is involved in Piezo1 activation-derived calcification

in VSMCs under calcium/phosphate disturbance (Fig. 9). While these findings advance

our understanding of vascular calcification mechanisms, several

methodological constraints should be noted. The HAD-induced CKD

vascular calcification model (55), which mimics VSMC osteogenic

transition through mechanisms shared with atherosclerosis (such as

oxidative stress and inflammation) (4), enables focused investigation of

Piezo1-mediated VSCM osteogenic differentiation. However, although

the high calcium/phosphate-induced VSMC osteogenic differentiation

model is widely adopted (55),

it cannot fully replicate the in vivo microenvironment.

Therefore, the applicability of these findings to other

calcification pathologies, such as atherosclerotic plaque formation

or age-related medial calcification, requires further validation

due to pathophysiological differences. While the present study has

characterized the role of Piezo1 in vascular calcification through

in vitro models, future studies should utilize RNA

interference approaches or Piezo1-selective inhibitors (GsMTx4 or

Dooku1) in well-established calcification animal models, such as

CKD or vitamin D3 overload models. These investigations would help

translate the mechanistic findings of the present study to

pathophysiological contexts, while simultaneously assessing

therapeutic potential.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding authors.

Authors' contributions

JT contributed to conceptualization, data curation,

formal analysis, methodology, project administration, validation,

visualization and writing. DY, ZF and HL contributed to the

conception and design of the study, project administration and data

validation. YZ, YC and KL contributed to critical intellectual

review, identifying key gaps and suggesting additional experiments,

validation and project administration. BL and SY contributed to the

conception and design of the study as well as project

administration. HT contributed to conceptualization, funding

acquisition, supervision, project administration and writing. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. JT

and HT confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiments adhered to ethical standards

for animal research and were approved by the Ethics Committee of

Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou,

China; approval no. SYSU-IACUC-2021-000877).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82170357 and 82470365) and

Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong province (grant nos.

2024A1515010663 and 2021A1515011766).

References

|

1

|

Lanzer P, Boehm M, Sorribas V, Thiriet M,

Janzen J, Zeller T, St Hilaire C and Shanahan C: Medial vascular

calcification revisited: Review and perspectives. Eur Heart J.

35:1515–1525. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ouyang L, Su X, Li W, Tang L, Zhang M, Zhu

Y, Xie C, Zhang P, Chen J and Huang H: ALKBH1-demethylated DNA

N6-methyladenine modification triggers vascular calcification via

osteogenic reprogramming in chronic kidney disease. J Clin Invest.

131:e1469852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Pazár B, Ea HK, Narayan S, Kolly L,

Bagnoud N, Chobaz V, Roger T, Lioté F, So A and Busso N: Basic

calcium phosphate crystals induce monocyte/macrophage IL-1β

secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro. J Immunol.

186:2495–2502. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Agharazii M, St-Louis R, Gautier-Bastien

A, Ung RV, Mokas S, Larivière R and Richard DE: Inflammatory

cytokines and reactive oxygen species as mediators of chronic

kidney disease-related vascular calcification. Am J Hypertens.

28:746–755. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cookson BT and Brennan MA:

Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol.

9:113–114. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Toldo S and Abbate A: The NLRP3

inflammasome in acute myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol.

15:203–214. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E and

Flavell R: Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature.

481:278–286. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y,

Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F and Shao F: Cleavage of GSDMD by

inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature.

526:660–665. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zeng C, Wang R and Tan H: Role of

pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases and its therapeutic

implications. Int J Biol Sci. 15:1345–1357. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Burger F, Baptista D, Roth A, da Silva RF,

Montecucco F, Mach F, Brandt KJ and Miteva K: NLRP3 inflammasome

activation controls vascular smooth muscle cells phenotypic switch

in atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 23:3402021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Takahashi M: NLRP3 inflammasome as a

common denominator of atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic

aneurysm. Circ J. 85:2129–2136. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ranade SS, Qiu Z, Woo SH, Hur SS, Murthy

SE, Cahalan SM, Xu J, Mathur J, Bandell M, Coste B, et al: Piezo1,

a mechanically activated ion channel, is required for vascular

development in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:10347–10352. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li J, Hou B, Tumova S, Muraki K, Bruns A,

Ludlow MJ, Sedo A, Hyman AJ, McKeown L, Young RS, et al: Piezo1

integration of vascular architecture with physiological force.

Nature. 515:279–282. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Retailleau K, Duprat F, Arhatte M, Ranade

SS, Peyronnet R, Martins JR, Jodar M, Moro C, Offermanns S, Feng Y,

et al: Piezo1 in smooth muscle cells is involved in

hypertension-dependent arterial remodeling. Cell Rep. 13:1161–1171.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rode B, Shi J, Endesh N, Drinkhill MJ,

Webster PJ, Lotteau SJ, Bailey MA, Yuldasheva NY, Ludlow MJ, Cubbon

RM, et al: Piezo1 channels sense whole body physical activity to

reset cardiovascular homeostasis and enhance performance. Nat

Commun. 8:350. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang S, Chennupati R, Kaur H, Iring A,

Wettschureck N and Offermanns S: Endothelial cation channel PIEZO1

controls blood pressure by mediating flow-induced ATP release. J

Clin Invest. 126:4527–4536. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Geng J, Shi Y, Zhang J, Yang B, Wang P,

Yuan W, Zhao H, Li J, Qin F, Hong L, et al: TLR4 signalling via

Piezo1 engages and enhances the macrophage mediated host response

during bacterial infection. Nat Commun. 12:35192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Barkai U, Prigent-Tessier A, Tessier C,

Gibori GB and Gibori G: Involvement of SOCS-1, the suppressor of

cytokine signaling, in the prevention of prolactin-responsive gene

expression in decidual cells. Mol Endocrinol. 14:554–563. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hughes K, Edin S, Antonsson A and

Grundstrom T: Calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates T cell

receptor/CD3- and phorbol ester-induced activation of IkappaB

kinase. J Biol Chem. 276:36008–36013. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Qian W, Hadi T, Silvestro M, Ma X, Rivera

CF, Bajpai A, Li R, Zhang Z, Qu H, Tellaoui RS, et al:

Microskeletal stiffness promotes aortic aneurysm by sustaining

pathological vascular smooth muscle cell mechanosensation via

Piezo1. Nat Commun. 13:5122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu S, Tao J, Duan F, Li H and Tan H: HHcy

induces pyroptosis and atherosclerosis via the lipid raft-mediated

NOX-ROS-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in apoE−/− mice.

Cells. 11:24382022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zeng C, Duan F, Hu J, Luo B, Huang B, Lou

X, Sun X, Li H, Zhang X, Yin S and Tan H: NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of

non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Redox Biol. 34:1015232020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

American Veterinary Medical Association

(AVMA): AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals: 2020

Edition. American Veterinary Medical Association; Schaumburg, IL:

2020

|

|

24

|

Guo Y, Tang Z, Yan B, Yin H, Tai S, Peng

J, Cui Y, Gui Y, Belke D, Zhou S and Zheng XL: PCSK9 (proprotein

convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) triggers vascular smooth muscle

cell senescence and apoptosis: implication of its direct role in

degenerative vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

42:67–86. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ayari H and Bricca G: Identification of

two genes potentially associated in iron-heme homeostasis in human

carotid plaque using microarray analysis. J Biosci. 38:311–315.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen YW, Pat B, Gladden JD, Zheng J,

Powell P, Wei CC, Cui X, Husain A and Dell'italia LJ: Dynamic

molecular and histopathological changes in the extracellular matrix

and inflammation in the transition to heart failure in isolated

volume overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 300:H2251–H2260.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Durham AL, Speer MY, Scatena M, Giachelli

CM and Shanahan CM: Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular

calcification: Implications in atherosclerosis and arterial

stiffness. Cardiovasc Res. 114:590–600. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zeng P, Yang J, Liu L, Yang X, Yao Z, Ma

C, Zhu H, Su J, Zhao Q, Feng K, et al: ERK1/2 inhibition reduces

vascular calcification by activating miR-126-3p-DKK1/LRP6 pathway.

Theranostics. 11:1129–1146. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhang X, Li Y, Yang P, Liu X, Lu L, Chen

Y, Zhong X, Li Z, Liu H, Ou C, et al: Trimethylamine-N-Oxide

promotes vascular calcification through activation of NLRP3

(nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin

domain-containing-3) inflammasome and NF-κB (nuclear factor κB)

signals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 40:751–765. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pang Q, Wang P, Pan Y, Dong X, Zhou T,

Song X and Zhang A: Irisin protects against vascular calcification

by activating autophagy and inhibiting NLRP3-mediated vascular

smooth muscle cell pyroptosis in chronic kidney disease. Cell Death

Dis. 13:2832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Eapen A, Kulkarni R, Ravindran S,

Ramachandran A, Sundivakkam P, Tiruppathi C and George A: Dentin

phosphophoryn activates Smad protein signaling through

Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in undifferentiated

mesenchymal cells. J Biol Chem. 288:8585–8595. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Guan Y, Chen Q, Yang X, Haines P, Pei M,

Terek R, Wei X, Zhao T and Wei L: Subcellular relocation of histone

deacetylase 4 regulates growth plate chondrocyte differentiation

through Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 303:C33–C40. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Jiang M, Zhang YX, Bu WJ, Li P, Chen JH,

Cao M, Dong YC, Sun ZJ and Dong DL: Piezo1 channel activation

stimulates ATP production through enhancing mitochondrial

respiration and glycolysis in vascular endothelial cells. Br J

Pharmacol. 180:1862–1877. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Solis AG, Bielecki P, Steach HR, Sharma L,

Harman CCD, Yun S, de Zoete MR, Warnock JN, To SDF, York AG, et al:

Mechanosensation of cyclical force by PIEZO1 is essential for

innate immunity. Nature. 573:69–74. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Maldonado N, Kelly-Arnold A, Laudier D,

Weinbaum S and Cardoso L: Imaging and analysis of

microcalcifications and lipid/necrotic core calcification in

fibrous cap atheroma. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 31:1079–1087. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yang Y, Wang D, Zhang C, Yang W, Li C, Gao

Z, Pei K and Li Y: Piezo1 mediates endothelial atherogenic

inflammatory responses via regulation of YAP/TAZ activation. Hum

Cell. 35:51–62. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Szabó L, Balogh N, Tóth A, Angyal Á,

Gönczi M, Csiki DM, Tóth C, Balatoni I, Jeney V, Csernoch L and

Dienes B: The mechanosensitive Piezo1 channels contribute to the

arterial medial calcification. Front Physiol. 13:10372302022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang YM, Chu TJ, Wan RT, Niu WP, Bian YF

and Li J: Quercetin ameliorates atherosclerosis by inhibiting

inflammation of vascular endothelial cells via Piezo1 channels.

Phytomedicine. 132:1558652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kelly-Arnold A, Maldonado N, Laudier D,

Aikawa E, Cardoso L and Weinbaum S: Revised microcalcification

hypothesis for fibrous cap rupture in human coronary arteries. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:10741–10746. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang K, Zhang Y, Feng W, Chen R, Chen J,

Touyz RM, Wang J and Huang H: Interleukin-18 enhances vascular

calcification and osteogenic differentiation of vascular smooth

muscle cells through TRPM7 activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol. 37:1933–1943. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ning FL, Tao J, Li DD, Tian LL, Wang ML,

Reilly S, Liu C, Cai H, Xin H and Zhang XM: Activating BK channels

ameliorates vascular smooth muscle calcification through Akt

signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 43:624–633. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

42

|

Jensky NE, Criqui MH, Wright MC, Wassel

CL, Brody SA and Allison MA: Blood pressure and vascular

calcification. Hypertension. 55:990–997. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gudipaty SA, Lindblom J, Loftus PD, Redd

MJ, Edes K, Davey CF, Krishnegowda V and Rosenblatt J: Mechanical

stretch triggers rapid epithelial cell division through Piezo1.

Nature. 543:118–121. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang S, Li W, Zhang P, Wang Z, Ma X, Liu

C, Vasilev K, Zhang L, Zhou X, Liu L, et al: Mechanical overloading

induces GPX4-regulated chondrocyte ferroptosis in osteoarthritis

via Piezo1 channel facilitated calcium influx. J Adv Res. 41:63–75.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Martinon F, Burns K and Tschopp J: The

inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of

inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell.

10:417–426. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Pan X, Xu H, Ding Z, Luo S, Li Z, Wan R,

Jiang J, Chen X, Liu S, Chen Z, et al: Guizhitongluo Tablet

inhibits atherosclerosis and foam cell formation through regulating

Piezo1/NLRP3 mediated macrophage pyroptosis. Phytomedicine.

132:1558272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Proudfoot D, Skepper JN, Hegyi L, Bennett

MR, Shanahan CM and Weissberg PL: Apoptosis regulates human

vascular calcification in vitro: Evidence for initiation of

vascular calcification by apoptotic bodies. Circ Res. 87:1055–1062.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Clarke MCH, Littlewood TD, Figg N, Maguire

JJ, Davenport AP, Goddard M and Bennett MR: Chronic apoptosis of

vascular smooth muscle cells accelerates atherosclerosis and

promotes calcification and medial degeneration. Circ Res.

102:1529–1538. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Di C, Ji M, Li W, Liu X, Gurung R, Qin B,

Ye S and Qi R: Pyroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells as a

potential new target for preventing vascular diseases. Cardiovasc

Drugs Ther. Jun 1–2024.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Okada K, Naito AT, Higo T, Nakagawa A,

Shibamoto M, Sakai T, Hashimoto A, Kuramoto Y, Sumida T, Nomura S,

et al: Wnt/β-catenin signaling contributes to skeletal myopathy in

heart failure via direct interaction with forkhead Box O. Circ

Heart Fail. 8:799–808. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang X, Leng S, Liu X, Hu X, Liu Y, Li X,

Feng Q, Guo W, Li N, Sheng Z, et al: Ion channel Piezo1 activation

aggravates the endothelial dysfunction under a high glucose

environment. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 23:1502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Cui S, Li Y, Zhang X, Wu B, Li M, Gao J,

Xia H and Xu L: FGF5 protects heart from sepsis injury by

attenuating cardiomyocyte pyroptosis through inhibiting CaMKII/NFκB

signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 636:104–112. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Li Y, Ahrens MJ, Wu A, Liu J and Dudley

AT: Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity

regulates the proliferative potential of growth plate chondrocytes.

Development. 138:359–370. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

54

|

Yu L, Ma X, Sun J, Tong J, Shi L, Sun L

and Zhang J: Fluid shear stress induces osteoblast differentiation

and arrests the cell cycle at the G0 phase via the ERK1/2 pathway.

Mol Med Rep. 16:8699–8708. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yang L, Dai R, Wu H, Cai Z, Xie N, Zhang

X, Shen Y, Gong Z, Jia Y, Yu F, et al: Unspliced XBP1 counteracts

β-catenin to inhibit vascular calcification. Circ Res. 130:213–229.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|