Structural birth defects (SBDs) are defined as

congenital abnormalities in physical structure that arise during

fetal development. Globally, these defects affect 3-6% of live-born

infants (1). The most prevalent

forms include congenital heart defects (CHDs) (0.33%), orofacial

clefts (OFCs) (0.14%) and neural tube defects (NTDs) (0.13%)

(2-4). These conditions are associated with

substantial perinatal mortality and long-term morbidity, imposing

notable burdens on affected families and society (5).

Current clinical screening for SBDs primarily relies

on prenatal ultrasound, maternal peripheral blood testing and

amniocentesis. While prenatal ultrasound can detect >80% of

fetal structural abnormalities (6), its diagnostic accuracy is limited

by operator expertise and equipment resolution, frequently failing

to identify subtle or complex malformations (7). Peripheral blood biochemical

analysis provides risk assessment for high-risk congenital

anomalies; however, current methodologies exhibit relatively high

rates of both false-positive and false-negative results (8-10). By contrast, genomics-based

approaches, including amniotic fluid karyotyping and conventional

non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) of peripheral blood, directly

identify chromosomal aneuploidies and

microdeletion/microduplication syndromes and address the diagnostic

limitations of ultrasound and enhance structural anomaly detection

rates (11,12). Nevertheless, these methods

currently elucidate the genetic factors in merely 19.1% of SBDs

cases, leaving 79.8% undiagnosed (13). Consequently, incorporating

advanced, comprehensive genomic technologies into both research and

clinical practice is essential for deciphering the complex genetic

architecture underlying SBDs.

Genomics, an interdisciplinary field investigating

genomic structure, function, evolution and interactions within

biological systems, seeks to elucidate fundamental biological

principles through comprehensive analysis of genetic information

(14,15). Recent advances in genomic

technologies have notably enhanced both research and clinical

applications for SBDs. These innovations facilitate not only more

precise identification of pathogenic variants and the discovery of

novel disease-associated genes, but also the refinement of prenatal

diagnostic approaches, thereby strengthening the scientific basis

for clinical decision-making and genetic counseling.

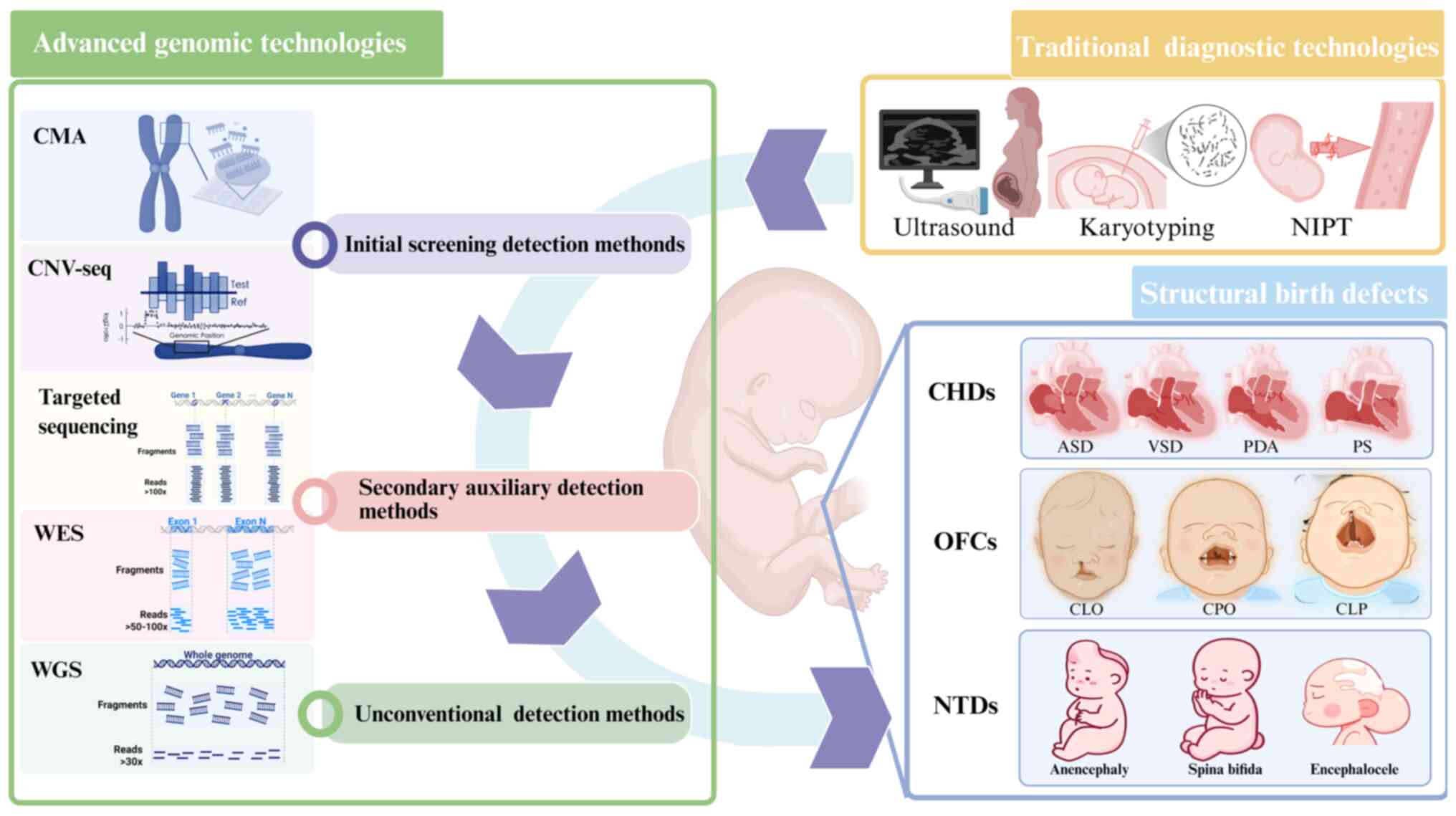

The present review discusses the genomic

technologies currently prevalent in genetic research, as well as

their application in prenatal diagnosis and candidate gene

screening for SBDs (Fig. 1),

while assessing the advantages and limitations of each method.

Furthermore, the present review explores potential future

directions within the context of reproductive health applications.

The aim of the present review was to establish a comprehensive

framework to equip clinicians with actionable technical and

analytical guidelines for evaluating the clinical translation of

these technologies as precision medicine modalities, with the

ultimate goal of improving diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic

strategies for SBDs.

In SBDs, genomic variations primarily present as

copy number variations (CNVs) and single nucleotide variations

(SNVs)/insertions-deletions (indels) (16,17). The precise detection of these

variants within the vast human genome constitutes the foundation

for elucidating the underlying genetic factors of SBDs. Advanced

genomic screening approaches primarily rely on high-throughput

technologies, including chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) and

next-generation sequencing (NGS). The NGS platform encompasses

various methodologies such as CNV-sequencing (CNV-seq), whole-exome

sequencing (WES), whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and targeted

sequencing. These technologies have markedly improved the detection

rate of pathogenic variations in SBDs, providing important evidence

support for clinical diagnosis (Table I).

CMA is a high-throughput microarray-based

technology. Through specifically designed probes that hybridize

with sample DNA, CMA detects various genomic variations including

CNVs, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), loss of

heterozygosity and uniparental disomy through fluorescence signal

intensity analysis (18). At

present, CMA is recommended as the effective genomic test for

fetuses with SBDs in clinical practice (19,20).

In fetuses with structurally abnormal findings

detected by ultrasound, CMA can effectively enable high-resolution

genomic screening to identify chromosomal abnormalities

undetectable by conventional karyotyping, including clinically

relevant microdeletions and microduplications (21-23). Besides, for fetuses with

ultrasound-detected multi-system structural abnormalities, CMA

demonstrates a notably higher detection rate of 41.2% for

chromosomal abnormalities, markedly surpassing the rates observed

in isolated system anomalies (such as 25.4% for cardiovascular

system abnormalities and 18.6% for central nervous system

abnormalities) (24).

Furthermore, CMA offers particular diagnostic value by identifying

~1.2% of clinically relevant abnormalities in low-risk pregnancies

with normal NIPT results (25).

Furthermore, CMA technology is relatively mature and easy to

operate, making it conducive to promoting prenatal genetic testing

in regions with limited medical resources (26).

However, CMA has inherent technical limitations in

clinical practice. The methodology carries detection risks for

variants <50 kb and cannot identify balanced translocations or

low-level mosaicism (26).

Furthermore, CMA lacks diagnostic capability for balanced

chromosomal rearrangements such as inversions and translocations

(27).

CNV-seq is an NGS technique that utilizes

low-coverage WGS (0.1-1x depth) to analyze fetal DNA for

chromosomal abnormalities and CNVs (28). With the development of NGS

technology, CNV-seq is emerging as a viable alternative to CMA for

the prenatal diagnosis (29).

CNV-seq demonstrates superior detection efficiency

for both CNVs and chromosomal abnormalities compared with NIPT in

SBDs (30,31). For fetuses with

ultrasound-detected abnormalities, CNV-seq exhibits a 2-4% higher

sensitivity compared with karyotyping in identifying chromosomal

aberrations (32,33). Moreover, CNV-seq provides

superior resolution compared with CMA, allowing for precise

detection of microdeletions, microduplications and low-level

mosaicism (<20%) (34,35).

Notably, CNV-seq not only detects all chromosomal aneuploidies and

large-scale genomic rearrangements identifiable by CMA but also

uncovers an additional 34.88% of clinically relevant variants

(34). In clinical practice, due

to its faster detection speed and smaller sample requirement,

CNV-seq can serve as a preliminary rapid test for early clinical

intervention. Meanwhile, its high compatibility with other NGS

platforms greatly simplifies testing workflows and reduces costs,

making the combination of CNV-seq with other NGS technologies a

preferred strategy in genetic testing for SBDs (36).

However, in clinical testing, CNV-seq cannot detect

balanced chromosomal translocations or inversions and has

restricted diagnostic utility in identifying polyploidy and

uniparental disomy associated with syndromic SBDs (37). Furthermore, CNV-seq exhibits

reduced sensitivity and undetermined specificity in CNV detection

when benchmarked against CMA (30,38).

Targeted sequencing represents a precision detection

methodology that employs NGS technology. This hypothesis-driven

approach utilizes customized probe or primer panels to selectively

capture and enrich predefined genomic regions for high-throughput

analysis, focusing primarily on functionally characterized regions

with established or putative disease associations (39). Through target enrichment,

targeted sequencing achieves notably enhance sequencing depth,

enabling sensitive detection of rare pathogenic SNVs/indels and

CNVs in known disease-related genes among fetuses with SBDs

(40,41). Therefore, in clinical practice,

specific genes or gene combinations can be selected based on fetal

phenotypes to perform targeted deep sequencing analysis and

diagnosis, while avoiding the blind use of WES or WGS (42).

In prenatal diagnosis, targeted sequencing serves as

a supplementary diagnostic tool for CMA-negative cases and is

particularly advantageous for fetuses with specific phenotypes,

detecting ~13.6% of pathogenic variants in those with SBDs

(42,43). Besides, the technology

demonstrates particular utility in diagnosing genetically

heterogeneous SBDs, allowing simultaneous analysis of multiple

candidate genes (44). Targeted

sequencing offers a cost-effective diagnostic solution for SBDs,

with core advantages of lower cost and short turnaround time. When

prenatal examinations suggest a fetus may have specific types of

structural abnormalities, this method can quickly confirm relevant

genetic subtypes and provide key evidence for genetic counseling

and clinical decision-making (41,45,46).

However, targeted sequencing has notable limitations

inherent to its design, which limits its application in certain

clinical scenarios; its diagnostic scope remains constrained by

current genomic knowledge, potentially missing novel pathogenic

genes or functionally relevant non-coding variants beyond

established disease associations (47). Furthermore, its capacity for

systematic investigation of complex structural variations is

intrinsically limited by restricted genomic coverage, which impedes

comprehensive genome-wide analyses (48).

WES employs an NGS technology coupled with

probe-based hybridization capture systems to specifically target

and enrich exonic regions and adjacent splice sites (±20 bp).

Although these regions constitute merely 1-2% of the human genome,

they harbor ~85% of known pathogenic variants. WES of these regions

enables the identification of clinical relevance for the majority

of SNVs/indels and CNVs in the human genome (49). Clinically, trio-WES is the most

effective exome testing method, as it enhances diagnostic rates,

elucidates variant origins and permits accurate recurrence risk

assessment and early prenatal diagnosis (50).

In SBDs, WES serves as a supplementary diagnostic

tool following inconclusive initial tests (such as CMA/CNV-seq) or

in special cases such as recurrent or lethal fetal abnormalities,

offering comprehensive exonic coverage that enhances the detection

of pathogenic variants compared with these methods (50,51). For fetuses with isolated SBDs

(such as CHDs or NTDs), WES offers an incremental diagnostic yield

of 10-50%, increasing to ~33% in cases with multi-system SBDs

(52-55). This approach is particularly

advantageous for disorders exhibiting high genetic and phenotypic

heterogeneity. Moreover, in fetuses with ultrasound-detected

cardiac or central nervous system abnormalities but negative CMA

and karyotyping results, WES effectively identifies recessive or

de novo dominant pathogenic mutations undetectable by

conventional methods, demonstrating superior diagnostic sensitivity

(56,57).

However, as WES relies on short-read sequencing

platforms, it may lead to inaccurate alignment in genomic regions

with high sequence homology, such as repetitive elements or

pseudogenes, potentially generating false-positive variant calls

(58,59). Additionally, emerging evidence

implicates that non-coding variations (including deep intronic

variants, long non-coding RNA regulatory elements and mitochondrial

DNA structural alterations) are also involved in the occurrence and

development of SBDs, while WES is mainly restricted to exonic

regions and adjacent splice sites, exhibiting markedly reduced

sensitivity for detecting these non-coding variants (60).

WGS shares technical principles with WES but extends

beyond WES's limitation to exonic regions. By enabling systematic

identification of SNVs/indels and CNVs across the entire genome,

WGS provides comprehensive genome-wide detection (49).

In fetuses with SBDs, WGS enables detection of

subtle structural variations (such as <10 kb) and yields more

precise genetic characterization (61,62). Beyond structural variants, WGS

identifies regulatory mechanisms underlying gene expression

dysregulation, including promoter/enhancer variants and deep

intronic splice-altering mutations. Notably, WGS precisely maps

complex genomic rearrangements such as intronic balanced

translocation breakpoints that disrupt normal mRNA splicing

(63,64). For fetuses exhibiting SBDs, WGS

demonstrates superior diagnostic capability by identifying both

variants detectable through CMA and WES, along with additional

pathogenic variants (65). This

comprehensive approach enhances diagnostic yield by 10-20% compared

with conventional methods. Currently, WGS offers the most

comprehensive diagnostic performance for SBDs, making it a

potential 'one-stop' test that reduces the need for repeated

testing (66).

Despite its superior sensitivity for structural

variation detection, WGS presents technical challenges. First,

genome-wide coverage generates extensive datasets with typically

low per-base sequencing depth, increasing the risk of

false-positive variant interpretation due to reduced confidence in

mutation calling (67,68). Second, the substantial costs

associated with per-sample sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

create economic barriers to implementation WGS in routine prenatal

screening programs (69). Thus,

the application of WGS in prenatal diagnosis is restricted to

supplementary roles in select cases such as fetuses with organ

system abnormalities, a history of recurrent adverse pregnancies

and negative CMA and WES results. However, with advancing

sequencing technology and falling costs, WGS is expected to become

a key tool in prenatal genetic diagnosis (70).

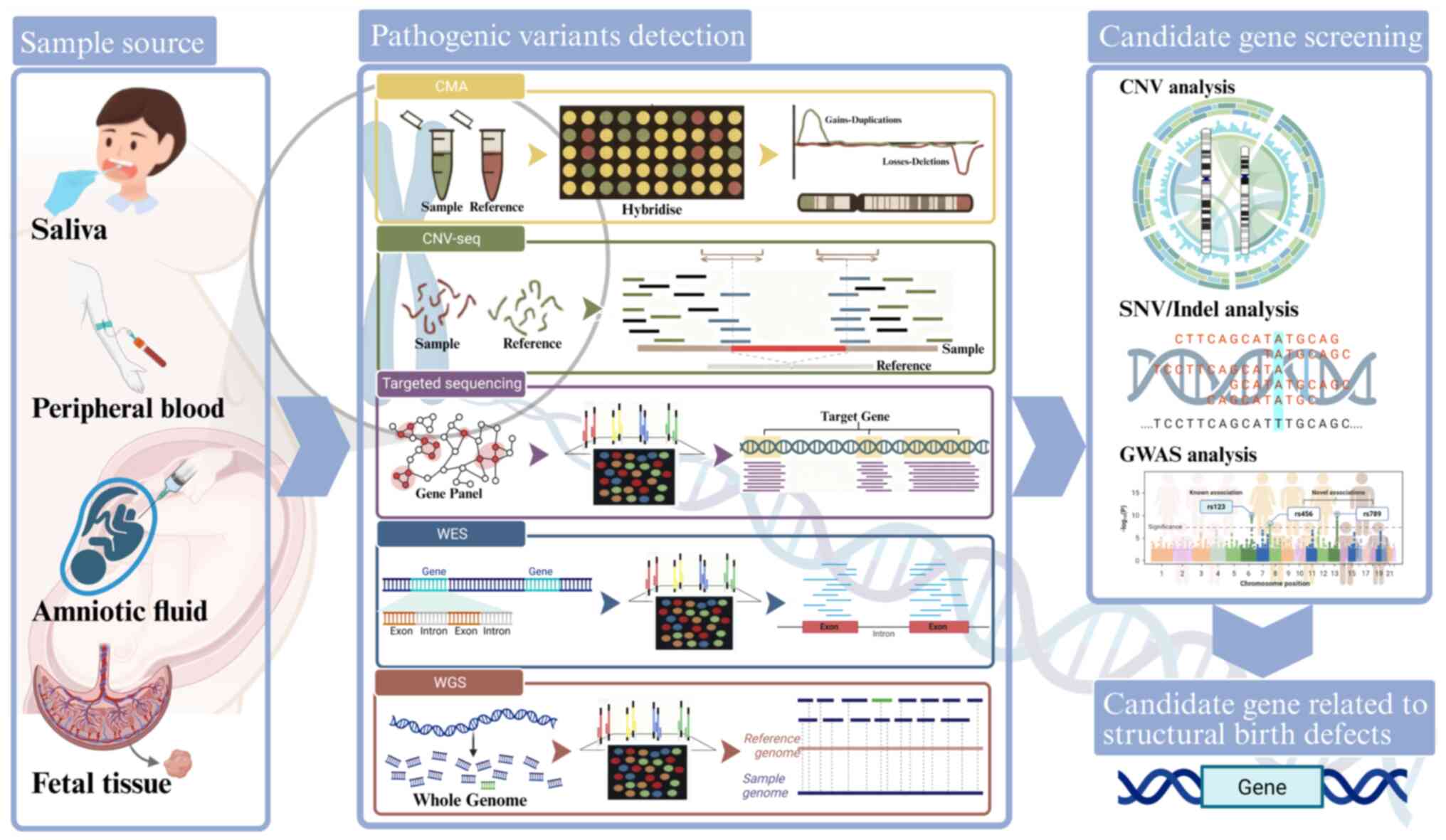

In genomic research, candidate genes are key genetic

elements identified through integrated bioinformatic analyses of

their potential associations with specific genetic disorders or

phenotypes. The CNVs and SNVs/indels identified through advanced

genomic technologies have precisely narrowed the search scope for

pathogenic variants via CNV analysis and SNVs/indels analysis,

while also advancing the development of genetic diagnostic methods.

Furthermore, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have expanded

the candidate gene spectrum by further analyzing the polygenic

inheritance effects of SBDs. These findings provide critical

insights into deciphering the genetic basis of SBDs (Fig. 2).

CNVs represent a class of genomic structural

variations involving DNA segment duplications or deletions

typically >50 kb. These variations can influence gene expression

through dosage effects, gene structure disruption or regulatory

element interference (71,72). To uncover such candidate genes

related to SBDs, comprehensive bioinformatic analysis of CNV

regions and their functionally associated gene networks provides a

crucial approach (73,74) (Table II).

CNVs contribute to 10-15% of CHD cases. Recurrent

CNVs in specific genomic regions, such as 1q21.1, 22q11.2 and

16p11.2, are frequently observed in patients with a CHD (75). These regions harbor

dosage-sensitive genes critical for cardiac development,

underscoring their role as a major genetic etiology of CHDs.

TBX1 haploinsufficiency caused by 22q11.2 microdeletions

represents one of the well-characterized core genetic mechanisms

(76). A WES study by Zhao et

al (77) further revealed

that chromatin regulatory genes within the 22q11.2 region,

including EP400, KAT6A, KMT2C, KMT2D, NST1,

CHD7 and PHF21A, exhibit markedly higher mutation

frequencies in patients with a CHD compared with controls, which

may contribute to abnormal cardiac development through epigenetic

regulatory mechanism. Additionally, a case-control study using CMA

identified SLC2A3 duplications in 5.0% (18/346) of 22q11.2

deletion syndrome patients with CHDs and aortic arch abnormalities,

a frequency markedly higher than in deletion-positive individuals

with normal cardiac anatomy. This finding implicates SLC2A3

duplication as a potential genetic modifier of cardiac phenotypes

in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (78). CNV studies of other pathogenic

regions have revealed additional candidate genes. For instance, Lin

et al (79) performed CMA

on a cohort of 1,118 Chinese fetuses with CHDs, identifying a

notable association between proximal 16p11.2 deletions (BP4-BP5

region) and CHDs; moreover, this association may be mediated

through TBX6 gene dysfunction. Another investigation of 78

non-22q11.2 deletion patients identified 15q21.1 and 2p22.3

duplications as novel pathogenic CNVs, with multiple implicated

genes (IRX4, BMPR1A, SORBS2, ID2, ROCK2, E2F6, GATA4, SOX7,

SEMAD6D, FBN1 and LTBP1) known to participate in cardiac

development (80). Mak et

al (81) performed a CMA

analysis using a large control cohort comprising 3,987 Caucasian

and 1,945 Singaporean Chinese subjects. The study identified 10

large rare CNVs, with further analysis revealing that nucleoredoxin

in the 17p13.3 region, COL4A1 and COL4A2 in 13q33.3,

and ZEB2 in the 2q22.3 region were strongly associated with

CHDs. Dasouki et al (82)

conducted CNV-seq analysis in 134 Saudi Arabian patients with CHDs,

detecting 21 copy number gains and 11 losses. The genomic variants

were primarily clustered in chromosomal regions 17q21.31, 8p11.21,

22q11.23 and 16p11.2. Functional and network analyses identified

NPHP1, PLCB1, KANSL1 and NR3C1 as potential candidate

genes associated with CHD pathogenesis.

Genetic investigations of OFCs have demonstrated the

crucial role of CNVs and their associated genes in disease

pathogenesis. Lansdon et al (83) performed CMA on cohorts from the

Philippines (n=869) and Europe (n=233) with non-syndromic cleft

lip/palate (nsCL/P), identifying recurrent 2q31.1 duplications (11

cases), 22q11.2 CNVs (4 cases) and 3q29 deletions (2 cases).

Further analyses implicated COBLL1, RIC1 and

ARHGEF38 as candidate genes, all involved in Rho/Rab GTPase

signaling pathways associated with OFCs and craniofacial anomalies.

Additionally, a separate multi-center study involving 270 orofacial

clefts cases identified a rare duplication variant at 19p13.12,

suggesting its potential as a pathogenic locus. The variant affects

SYDE1, BRD4 and AKAP8, which exhibit

spatiotemporally specific expression patterns in the branchial

arches and frontonasal processes of E10.5 mouse embryos. These

findings indicate that this gene cluster may represent a novel

susceptibility factor for nsCL/P (84). Furthermore, in a CMA analysis of

467 OFC trios (comprising 1,375 subjects) and 391 control trios

(902 subjects), Younkin et al (85) identified a genome-wide

significant 62 kb non-coding region at 7p14.1 and proposed

TARP as a candidate gene for the early prenatal diagnosis of

OFCs, suggesting a potential role of T-cell receptors in OFC

pathogenesis. A further study on this cohort identified two

deletions: A 67 kb deletion in MGAM on chromosome 7q34 and a

206 kb deletion spanning ADAM3A and ADAM5 in the 8p11

region. The frequency of these deletions was markedly higher in

affected families compared with in unaffected controls, further

supporting their potential role as candidate genes (86).

CNV analysis has been used to identify associations

among common and rare genetic variants and NTD risks and has

identified several promising candidate genes. A WES study analyzed

patients with meningomyelocele and identified 6 cases harboring a

22q11.2 deletion, which included an LCR22C-D deletion within the

low-copy repeat region. Furthermore, the study pinpointed

AIFM3, CRKL and PI4KA as key candidate genes within

this locus (87). Additionally,

a WGS-based analysis involving cohorts from the United States and

Qatar (comprising 140 patients with spina bifida and 183 controls)

expanded the gene network associated with NTD-related CNVs. Rare

coding CNVs were identified in pathways critical to NTD

pathogenesis, including cell cycle regulation (SH3GL3 and

PARD3), mitochondrial metabolism (DMGDH and

FOXRED1), transmembrane transport (SLC44A2 and

SLC44A3) and signal transduction (VAV2 and

DOCK10) (88). Tian et

al (89) performed CNV

analysis of all exonic regions in planar cell polarity (PCP)

pathway-related genes (VANGL1, VANGL2, CELSR1, SCRIB, DVL2,

DVL3 and PTK7) in 11 NTD probands, identifying 16 CNVs.

The CNVs were predominantly located in DVL2, VANGL1 and

VANGL2, suggesting these genes as strong candidates for NTD

pathogenesis. These findings not only delineate the multi-pathway

pathogenic framework of NTDs but also provide novel insights into

the genetic association between NTDs and CNVs.

In summary, CNVs are notably associated with the

incidence of SBDs. CNV analysis can elucidate the genetic effects

of large-fragment deletion mutations, holding substantial relevance

for identifying key pathogenic genes and exploring potential gene

dosage-phenotype associations.

Small variants typically encompass SNVs, short

insertions and short deletions (<50 bp) (16). These variants can impact the

function of critical genes, thereby contributing to the development

of SBDs (90,91). The detection and analysis of

SNVs/indels have notably enhanced the understanding of these subtle

genetic alterations in SBDs and have effectively expanded the

candidate gene spectrum for these conditions (Table III).

Through SNV/indel analyses have served a key role in

unraveling the complex genetic heterogeneity characteristic of

CHDs. In a landmark study, Sevim et al (92) performed a systematic WES analysis

on 559 families with CHDs, identifying 23 novel candidate

pathogenic genes. Notably, HSP90AA1, IQGAP1 and

TJP2 showed strong associations with isolated CHDs, whereas

ROCK2, APBB1, KDM5A and CHD4 were

primarily associated with non-isolated CHDs. Among these,

HSP90AA1, ROCK2, IQGAP1 and CHD4

exhibited the highest relevance in pathogenicity prediction models,

underscoring their central roles in disease pathogenesis. An

additional WES study involving 52 Qatari families (178 individuals)

identified four pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants: ROBO1,

SLC2A10, SMAD6 and CHD7. Notably, ROBO1 was found

to functionally interact with classical CHD-related genes such as

TBX1, TBX5, NOTCH1 and NKX2-5 in interaction

networks. Mechanistic studies using a chick heart development model

demonstrated that SMAD6 contributes to CHD pathogenesis

through synergistic regulation with NKX2-5 (93). Substantial progress has also been

made in subtype-specific CHD research. Shi et al (94) analyzed WES data from 100 patients

with pulmonary artery atresia and 100 healthy controls, integrating

network analysis and gene expression validation to establish

associations between DNAH10, DST, FAT1, HMCN1, HNRNPC, TEP1

and TYK2 with the pathological mechanisms of pulmonary

artery atresia for the first time. In the research of total

anomalous pulmonary venous connection, WES analysis of 78 sporadic

cases and 100 controls identified seven candidate genes: CLTCL1,

CST3, GXYLT1, HMGA2, SNAI1, VAV2 and ZDHHC8. Functional

verification and zebrafish model interaction network analysis

further validated SNAI1, HMGA2 and VAV2 as key

candidate genes driving total anomalous pulmonary venous connection

pathogenesis (95).

By examining protein-altering variations such as

missense and frameshift mutations, SNV/indel analysis has revealed

how coding sequence modifications induce functional changes

(loss/gain-of-function), thereby offering novel perspectives on OFC

candidate genes. WES of 84 affected individuals from 46 families

with nsCL/P identified rare deleterious variants in TP63,

TBX1, LRP6 and GRHL3, genes previously associated

with syndromic forms (96).

Mangold et al (24)

performed targeted sequencing in a cohort of 576 European patients

with nsCL/P and 96 non-syndromic cleft palate only cases,

identifying four novel truncating GRHL3 mutations. Notably,

all nine mutation carriers exclusively presented with non-syndromic

cleft palate only, providing compelling evidence for the notable

pathogenic contribution of GRHL3 to non-syndromic cleft

palate only. A subsequent WES study of 132 non-syndromic cleft

palate only cases and 623 multiethnic controls identified three

novel candidate genes (ACACB, PTPRS and MIB1), along

with de novo variants in GRHL3 and CREBBP,

genes associated with Van der Woude syndrome and Rubinstein-Taybi

syndrome, respectively (97). A

trio-WES analysis of 130 African nsCL/P families identified

pathogenic AFDN missense mutations (p.E485K and p.G1703R)

that may disrupt connexin binding, potentially impairing cell

polarity regulation and mesenchymal migration during facial

morphogenesis (98). A WES study

from Eastern Chinese cohorts demonstrated LAMA5 mutations in

nsCL/P cases, with further investigations revealing the crucial

role of LAMA5 in palatal development, establishing it as a

strong candidate gene (99).

Kumari et al (100)

identified variants in TGFβ3, MSX1 and MMP3 through

WES analysis of 245 Indian nsCL/P cases and validated these genes

as strong candidates for OFCs.

The application of SNV/indel analysis has

facilitated the identification of candidate genes within the

underlying pathways of NTDs. WES performed on 23 myelomeningocele

cases in France revealed that de novo variants in crucial

genes of the vitamin B12 metabolism pathway (LRP2, MMAA and

TCN2), genes related to folate metabolism (FPGS), the

core regulator of choline metabolism (BHMT) and GLI3,

a key regulatory element of the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway,

were notably linked to genetic susceptibility to NTDs (101). A WGS study involving 140

isolated spina bifida samples further identified eight rare

missense variants in the CIC gene, which were validated

through functional analysis. These CIC missense variants

found in NTD cases notably suppressed folate receptor 1 protein

expression levels and disrupted the transduction of the PCP

signaling pathway (102).

Additionally, analysis of trio-WES in 43 cases of sporadic

myelomeningocele/anencephaly and their parents identified seven

core candidate genes: SHROOM3, PAX3, GRHL3, PTPRS, WBSCR28,

MFAP1 and DDX3X. Among them, SHROOM3 is noted for

its high degree of evolutionary conservation, the knockout of its

double isoform resulted in 100% incidence of exencephaly and a 23%

penetrance rate of spina bifida phenotypes in mouse embryos. As a

key regulator of neural crest differentiation, rare variants

c.218C>A in PAX3 can potentially lead to NTD phenotypes

by disrupting neural crest cell migration during neural tube

closure (103). Building on

this understanding, Chen et al (104) employed targeted sequencing

technology to perform a comprehensive analysis of the SHROOM

gene family in a cohort of 343 individuals with NTDs and 206

control subjects in China. The findings revealed a markedly higher

frequency of damaging missense variants in the SHROOM2 gene

among the case group compared with the control group. These

mutations lead to the failure of neural tube closure by disrupting

the interaction between SHROOM2 and ROCK1 proteins, thereby

interfering with the cytoskeletal remodeling mediated by the planar

cell polarity pathway.

SNV/indel analysis systematically investigates

subtle genetic alterations overlooked in CNV analysis, precisely

mapping associated loci of SBDs and revealing the impact of

nucleotide-level modifications on gene function. This approach

notably establishes a crucial molecular foundation for optimizing

precision prevention strategies of SBDs and exploring molecular

pathways for targeted therapies.

The genetic basis of most SBDs stems from the

cumulative effects of multiple minor-effect genes rather than

single-gene mutations (105).

Consequently, identifying candidate genes involved in polygenic

synergistic pathogenesis is crucial for elucidating the genetic

factors underlying these complex disorders. GWAS analysis represent

a pivotal approach in contemporary genomics research, employing SNP

arrays or NGS technologies to systematically examine genome-wide

genetic variations. Through multivariate data analysis, GWAS

analysis elucidates associations between these variations and

phenotypic traits, thereby revealing the genetic architecture of

complex traits (106,107). Advances in GWAS applications

for SBDs have led to the discovery of numerous potential candidate

genes, representing a notable breakthrough in understanding the

molecular pathogenesis of these conditions (Table IV).

GWAS analysis has provided crucial insights into the

complex genetic architecture of CHDs. A large-scale GWAS involving

40,000 UK Biobank samples identified 130 loci notably associated

with right heart phenotypes, a number of which are located near

known regulatory genes such as NKX2-4, TBX5/TBX3, WNT9B and

GATA4. The pivotal role of these genes in cardiac

morphogenesis has been further substantiated (108). Additionally, a single-trait

GWAS analysis of 29,506 individuals with right ventricular

structural abnormalities revealed 12 candidate genes shared across

different right ventricular phenotypes, including TTN, ATXN2,

PTPN11 and ACTN4. Notably, FHOD3, MYH6,

MYL4 and TMEM43 exhibit functional overlap with

Mendelian cardiomyopathy genes, with their encoded proteins

primarily involved in myocardial contraction and cell adhesion

processes (109). Lahm et

al (110) identified

MACROD2, GOSR2, WNT3 and MSX1 as critical genes in

embryonic cardiac development, which were significantly associated

with SNPs based on CMA and GWAS analyses of 4,034 Caucasian

patients with CHDs and 8,486 healthy controls. Jin et al

(111) expanded this research

by performing WES combined with GWAS on 2,871 CHD probands. The

findings demonstrated that MYH6 mutations were notably

associated with an elevated risk of ventricular dysfunction,

whereas dominant mutations in FLT4 were specifically linked

to tetralogy of Fallot. Furthermore, rare inherited and de

novo heterozygous variants were markedly enriched in genes such

as CHD7, KMT2D, PTPN11, RBFOX2, FLT4, SMAD6 and

NOTCH1 among patients with complex CHDs, highlighting novel

candidate targets for further investigation.

GWAS analysis has identified multiple candidate

genes potentially involved in OFCs. A GWAS of a Maya population

(149 patients with nsCL/P and 303 controls) revealed notable

associations between nsCL/P and genetic variants in IRF6, as

well as loci at 8q24, 10q25 and 17q22. Single-marker analysis

further confirmed these associations, particularly for IRF6,

8q24 and 10q25 (112). A

pleiotropy-informed conditional false discovery rate analysis,

incorporating 814 nsCL/P cases, 205 nsCPO cases and 2,159 controls

from an African population GWAS, along with mouse facial

development expression data, identified 19 potential candidate

genes. Among these, MDN1, MAP3K7, KMT2A and ARCN1

emerged as top candidates, supported by evidence from mouse models

or individuals harboring pathogenic variants in these genes

(113). In a separate GWAS of

oral clefts in a Polish cohort, eight single-nucleotide

polymorphisms in PAX7 were strongly associated with nsCL/P,

with the etiological role of the gene independently validated in a

cohort of 247 patients and 445 controls (114). These findings not only expand

the repertoire of candidate genes implicated in OFCs but also

provide a molecular framework for understanding how genetic

background influences craniofacial development across diverse

populations. The application of GWAS has notably advanced the

identification of candidate genes for SBDs, with large sample sizes

enhancing result accuracy.

GWAS analyses enhance the understanding of SBDs

with polygenic inheritance patterns by analyzing genome-wide

associations between genetic variants and these defects while

quantifying the cumulative effects of multiple variants.

Furthermore, GWAS analysis provides a comprehensive assessment of

gene-gene interactions throughout the genome, filling the research

gap in the study of polygenic effects in CNV analysis or SNV/indel

analysis, and greatly expanding the potential candidate gene pool

associated with SBDs.

The clinical evaluation of SBDs has been

revolutionized by continuous innovations in genomic technologies,

establishing a tiered diagnostic pathway. For fetuses with

ultrasound anomalies, CMA or CNV-seq serves as first-tier testing.

In cases with negative results, particularly those with a complex

phenotype or adverse pregnancy history, NGS methodologies such as

WES or targeted sequencing provide a subsequent high-yield option.

This evolving diagnostic paradigm enhances variant detection,

facilitates precise genetic diagnosis and ultimately informs

prenatal counseling, prognosis and recurrence risk assessment. WGS,

through comprehensive detection of the entire genome, further

improves the detection rate of pathogenic genes; although its

clinical application is still limited due to technical constraints

and cost factors, WGS has the potential to become the 'ultimate'

prenatal diagnostic method.

Notwithstanding notable progress in genomics that

has advanced research on SBDs, numerous challenges remain in

pathogenic variant detection and candidate genes screening

strategies. Current genomic approaches exhibit technical

limitations in sensitivity and specificity when detecting specific

genetic variants (61,116,117). CMA fails to identify certain

complex structural variations, while NGS inherently misaligns

sequences in GC-rich regions, resulting in undetected mutations

within these GC-rich areas and consequent false-negative findings

(118,119). Additionally, the short-read

(<300 bp) nature of NGS presents inherent limitations,

demonstrating particularly poor mapping quality for homologous

region sequences, with frequent read misalignments from homologous

segments leading to insufficient coverage. For repetitive genomic

regions, reliable read mapping requires the presence of unique

flanking sequences adjacent to the repetitive elements (120). Single-omics-based candidate

gene screening strategies impose additional limitations on genetic

dissection of SBDs. Genomics-dependent analyses cannot

authentically validate the functional disruption and regulatory

network imbalance caused by pathogenic variants. Moreover, numerous

detected genetic variants remain classified as variants of

uncertain relevance, substantially constraining variant

interpretation and accurate classification (121,122). Furthermore, insufficient cohort

sizes and a lack of ethnic diversity in current studies not only

constrain the discovery of pathogenic variants and analysis of

candidate genes, but also compromise the generalizability of

diagnostic findings, particularly hindering the clinical

translation of candidate gene research outcomes across diverse

populations (105). Therefore,

it is necessary to utilize large-scale, multi-ethnic biobanks

established through international collaboration, which provide

statistically robust cohorts for screening and validating candidate

genes while reducing the impact of population representation

bias.

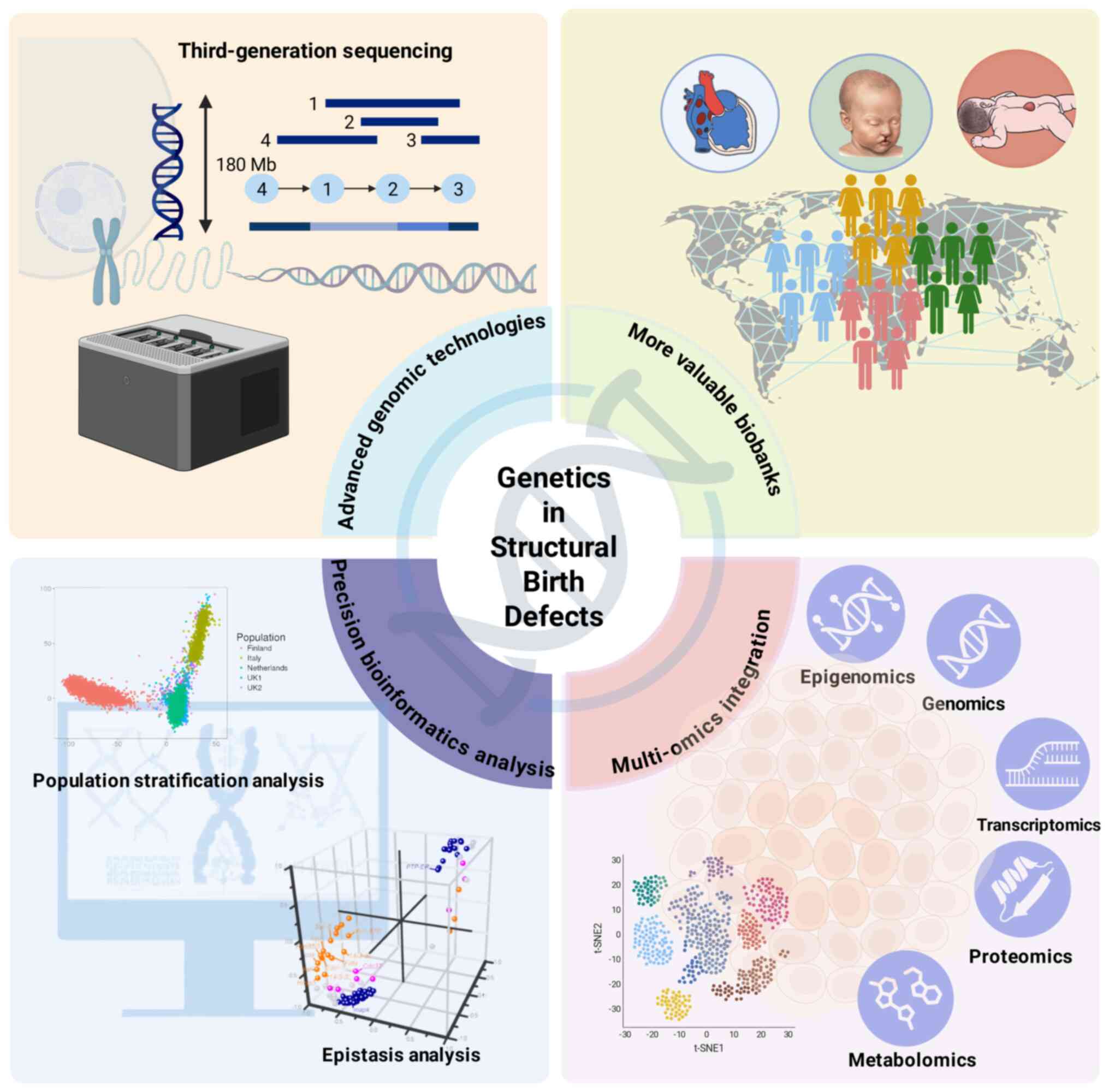

Therefore, improving the identification of

pathogenic variants and candidate gene screening strategies

represents a critical challenge for advancing the understanding of

the genetics of SBDs (Fig. 3).

In recent years, high-precision genomic technologies, particularly

third-generation sequencing (TGS) and optical genome mapping (OGM),

have emerged as powerful tools in genetic disorder exploration

(120). TGS platforms, with

their long-read (>10 kb) sequencing capabilities, effectively

address short-read sequencing limitations by enabling precise

characterization of structurally complex genomic regions, including

telomeres and centromeres (123-125). TGS has demonstrated promising

application prospects in neonatal genetic disorders but has not yet

been applied to research on SBDs (126). OGM demonstrates exceptional

capabilities in detecting cryptic structural variations through

fluorescent labeling of DNA fragments >150 kb (123,127). In the field of NTDs research,

Sahajpal et al (128)

pioneered the application of OGM technology to perform

comprehensive analysis of genome-wide structural variations in 104

patient samples with NTD. The findings not only identified notable

associations between NTDs and genes including RMND5A, HNRNPC,

FOXD4 and RBBP4, but also extended for the first time

the phenotypic spectrum of AMER1 and TGIF1 genes to

encompass NTDs. This groundbreaking study demonstrated the crucial

role of genomic structural variations in the pathogenesis of such

SBDs, providing essential molecular genetic evidence for subsequent

research in this field. Furthermore, the rapid advancement of

bioinformatics has notably optimized the genomic-based analysis

pipeline for pathogenic variants. For instance, epistasis analysis

enables the examination of joint genetic effects across multiple

loci, helping to elucidate a portion of the 'missing heritability'

that encompasses marginal genetic effects undetectable by

conventional GWAS (129,130).

Population stratification methods, such as principal component

analysis or linear mixed models with random effects, can

effectively mitigate confounding effects from population

stratification and structure in GWAS (131,132). Multi-omics approaches enable

mechanistic investigations into how candidate genes disrupt

cellular pathways, proving particularly valuable for elucidating

the functions of regulatory elements in non-coding regions that

were previously overlooked in genomic studies (133). Therefore, it has further

refined candidate gene screening strategies, providing novel

perspectives for deciphering the genetic basis of SBDs (134).

In summary, the present review delineates current

advanced genomic technologies applied in SBD research and

diagnostics, while providing a comparative analysis of their

respective advantages and limitations. The present review further

consolidates candidate genes identified through these technological

approaches, with these clinically-relevant candidates being derived

from human clinical specimens that more faithfully recapitulate

disease pathogenesis compared with animal or cellular models. The

investigation of genetic contributors to SBDs has now entered a

transformative era marked by multi-omics convergence and

technological synergy. Through the implementation of

higher-resolution platforms, expanded cohort sizes, refined

bioinformatics analyses and sophisticated multi-omics integration,

researchers are now empowered to more systematically and precisely

identify pathogenic variants associated with SBDs, thereby

uncovering clinically actionable candidate genes.

Not applicable.

RX and WH conceived the idea; RX contributed to

writing the initial draft and preparing the figures; HR designed

the tables; WH and HG contributed to the improvement of the initial

draft and revision; RX, ZY and HR helped proofread and improved the

manuscript; RX, WH, ZY and HG critically reviewed and edited the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82502070), National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82271730) and Shenyang Science and

Technology Planning Project (grant no. 22-321-33-22).

|

1

|

Hobbs CA, Chowdhury S, Cleves MA, Erickson

S, MacLeod SL, Shaw GM, Shete S, Witte JS and Tycko B: Genetic

epidemiology and nonsyndromic structural birth defects: From

candidate genes to epigenetics. Jama Pediatr. 168:371–377. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mone F, Quinlan-Jones E, Ewer AK and Kilby

MD: Exome sequencing in the assessment of congenital malformations

in the fetus and neonate. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

104:F452–F456. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kang L, Guo Z, Shang W, Cao GY, Zhang YP,

Wang QM, Shen HP, Liang WN and Liu M: Perinatal prevalence of birth

defects in the Mainland of China, 2000-2021: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. World J Pediatr. 20:669–681. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Basu M, Zhu J, LaHaye S, Majumdar U, Jiao

K, Han Z and Garg V: Epigenetic mechanisms underlying maternal

diabetes-associated risk of congenital heart disease. JCI Insight.

2:e950852017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nasreddine G, El HJ and Ghassibe-Sabbagh

M: Orofacial clefts embryology, classification, epidemiology, and

genetics. Mutat Res Rev Mutat. 787:1083732021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Buijtendijk MF, Bet BB, Leeflang MM, Shah

H, Reuvekamp T, Goring T, Docter D, Timmerman MG, Dawood Y,

Lugthart MA, et al: Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound screening for

fetal structural abnormalities during the first and second

trimester of pregnancy in low-risk and unselected populations.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5:CD147152024.

|

|

7

|

van Nisselrooij AEL, Teunissen AKK, Clur

SA, Rozendaal L, Pajkrt E, Linskens IH, Rammeloo L, van Lith JMM,

Blom NA and Haak MC: Why are congenital heart defects being missed?

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 55:747–757. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

8

|

Hematian MN, Hessami K, Torabi S and Saleh

M, Nouri B and Saleh M: A prospective cohort study on association

of first-trimester serum biomarkers and risk of isolated foetal

congenital heart defects. Biomarkers. 26:747–751. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang X, Yang X, Huang P, Meng X, Bian Z

and Meng L: Identification of maternal serum biomarkers for

prenatal diagnosis of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts. Ann NY Acad

Sci. 1510:167–179. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lupo PJ, Archer NP, Harris RD, Marengo LK,

Schraw JM, Hoyt AT, Tanksley S, Lee R, Drummond-Borg M, Freedenberg

D, et al: Newborn screening analytes and structural birth defects

among 27,000 newborns. PLoS One. 19:e3042382024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Li L, He Z, Huang X, Lin S, Wu J, Huang L,

Wan Y and Fang Q: Chromosomal abnormalities detected by karyotyping

and microarray analysis in twins with structural anomalies.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 55:502–509. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jayashankar SS, Nasaruddin ML, Hassan MF,

Dasrilsyah RA, Shafiee MN, Ismail NAS and Alias E: Non-invasive

prenatal testing (NIPT): Reliability, challenges, and future

directions. Diagnostics (Basel). 13:25702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Feldkamp ML, Carey JC, Byrne JLB, Krikov S

and Botto LD: Etiology and clinical presentation of birth defects:

Population based study. BMJ. 357:j22492017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang J: What has genomics taught an

evolutionary biologist? Genom Proteom Bioinf. 21:1–12. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Green ED, Gunter C, Biesecker LG, Di

Francesco V, Easter CL, Feingold EA, Felsenfeld AL, Kaufman DJ,

Ostrander EA, Pavan WJ, et al: Strategic vision for improving human

health at The Forefront of Genomics. Nature. 586:683–692. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kosugi S, Momozawa Y, Liu X, Terao C, Kubo

M and Kamatani Y: Comprehensive evaluation of structural variation

detection algorithms for whole genome sequencing. Genome Biol.

20:1172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Audano PA, Sulovari A, Graves-Lindsay TA,

Cantsilieris S, Sorensen M, Welch AE, Dougherty ML, Nelson BJ, Shah

A, Dutcher SK, et al: Characterizing the major structural variant

alleles of the human genome. Cell. 176:663–675. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Levy B and Wapner R: Prenatal diagnosis by

chromosomal microarray analysis. Fertil Steril. 109:201–212. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Committee Opinion No. 682 Summary:

Microarrays and Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: The use of

advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology.

Obstet Gynecol. 128:1462–1463. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hu P, Zhang Q, Cheng Q, Luo C, Zhang C,

Zhou R, Meng L, Huang M, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al: Whole genome

sequencing vs chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal

diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 229:301–302. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lan L, Luo D, Lian J, She L, Zhang B,

Zhong H, Wang H and Wu H: Chromosomal abnormalities detected by

chromosomal microarray analysis and karyotype in fetuses with

ultrasound abnormalities. Int J Gen Med. 17:4645–4658. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rodriguez-Revenga L, Madrigal I, Borrell

A, Martinez JM, Sabria J, Martin L, Jimenez W, Mira A, Badenas C

and Milà M: Chromosome microarray analysis should be offered to all

invasive prenatal diagnostic testing following a normal rapid

aneuploidy test result. Clin Genet. 98:379–383. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xia M, Yang X, Fu J, Teng Z, Lv Y and Yu

L: Application of chromosome microarray analysis in prenatal

diagnosis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20:6962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mangold E, Böhmer AC, Ishorst N, Hoebel

AK, Gültepe P, Schuenke H, Klamt J, Hofmann A, Gölz L, Raff R, et

al: Sequencing the GRHL3 coding region reveals rare truncating

mutations and a common susceptibility variant for nonsyndromic

cleft palate. AM J Hum Genet. 98:755–762. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Maya I, Salzer SL, Brabbing-Goldstein D,

Matar R, Kahana S, Agmon-Fishman I, Klein C, Gurevitch M,

Basel-Salmon L and Sagi-Dain L: Residual risk for clinically

significant copy number variants in low-risk pregnancies, following

exclusion of noninvasive prenatal screening-detectable findings. Am

J Obstet Gynecol. 226:562.e1–562.e8. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu X, Liu S, Wang H and Hu T: Potentials

and challenges of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal

diagnosis. Front Genet. 13:9381832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lee CL, Lee CH, Chuang CK, Chiu HC, Chen

YJ, Chou CL, Wu PS, Chen CP, Lin HY and Lin SP: Array-CGH increased

the diagnostic rate of developmental delay or intellectual

disability in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 60:453–460. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Xie C and Tammi MT: CNV-seq, a new method

to detect copy number variation using high-throughput sequencing.

BMC Bioinformatics. 10:802009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang J, Chen L, Zhou C, Wang L, Xie H,

Xiao Y, Zhu H, Hu T, Zhang Z, Zhu Q, et al: Prospective chromosome

analysis of 3429 amniocentesis samples in China using copy number

variation sequencing. AM J Obstet Gynecol. 219:287.e1–287.e18.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yang L, Yang J, Bu G, Han R, Rezhake J and

La X: Efficiency of Non-invasive prenatal testing in detecting

fetal copy number variation: A retrospective cohort study. Int J

Womens Health. 16:1661–1669. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang X, Sha J, Han Y, Pang M, Liu M, Liu

M, Zhang B and Zhai J: Efficiency of copy number variation

sequencing combined with karyotyping in fetuses with congenital

heart disease and the following outcomes. Mol Cytogenet. 17:122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang Y, Fu S, Shao D, Yao Y, Wu F and Yao

M: Comprehensive chromosomal abnormality detection: Integrating

CNV-Seq with traditional karyotyping in prenatal diagnostics. BMC

Med Genomics. 18:812025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Luo H, Wang Q, Fu D, Gao J and Lu D:

Additional diagnostic value of CNV-seq over conventional

karyotyping in prenatal diagnosis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 49:1641–1650. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ma N, Xi H, Chen J, Peng Y, Jia Z, Yang S,

Hu J, Pang J, Zhang Y, Hu R, et al: Integrated CNV-seq, karyotyping

and SNP-array analyses for effective prenatal diagnosis of

chromosomal mosaicism. BMC Med Genomics. 14:562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhao X and Fu L: Efficacy of copy-number

variation sequencing technology in prenatal diagnosis. J Perinat

Med. 47:651–655. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen X, Jiang Y, Chen R, Qi Q, Zhang X,

Zhao S, Liu C, Wang W, Li Y, Sun G, et al: Clinical efficiency of

simultaneous CNV-seq and whole-exome sequencing for testing fetal

structural anomalies. J Transl Med. 20:102022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen Y, Han X, Hua R, Li N, Zhang L, Hu W,

Wang Y, Qian Z and Li S: Copy number variation sequencing for the

products of conception: What is the optimal testing strategy. Clin

Chim Acta. 557:1178842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yao R, Zhang C, Yu T, Li N, Hu X, Wang X,

Wang J and Shen Y: Evaluation of three read-depth based CNV

detection tools using whole-exome sequencing data. Mol Cytogenet.

10:302017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pei XM, Yeung MHY, Wong ANN, Tsang HF, Yu

ACS, Yim AKY and Wong SCC: Targeted sequencing approach and its

clinical applications for the molecular diagnosis of human

diseases. Cells. 12:4932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hu P, Qiao F, Wang Y, Meng L, Ji X, Luo C,

Xu T, Zhou R, Zhang J, Yu B, et al: Clinical application of

targeted next-generation sequencing in fetuses with congenital

heart defect. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 52:205–211. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gong B, Li D, Łabaj PP, Pan B,

Novoradovskaya N, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Chen G, Bergstrom

Lucas A, LoCoco JS, et al: Targeted DNA-seq and RNA-seq of

reference samples with Short-read and Long-read sequencing. Sci

Data. 11:8922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Vora NL and Norton ME: Prenatal exome and

genome sequencing for fetal structural abnormalities. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 228:140–149. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

43

|

Allen VM, Schollenberg E, Aberg E and

Brock JK: Use of Clinically informed strategies and diagnostic

yields of genetic testing for fetal structural anomalies following

a non-diagnostic microarray result: A Population-based cohort

study. Prenatal Diag. 45:318–325. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Pangalos C, Hagnefelt B, Lilakos K and

Konialis C: First applications of a targeted exome sequencing

approach in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities reveals an

important fraction of cases with associated gene defects. PeerJ.

4:e19552016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li Y, Anderson LA, Ginns EI and Devlin JJ:

Cost effectiveness of karyotyping, chromosomal microarray analysis,

and targeted Next-generation sequencing of patients with

unexplained global developmental delay or intellectual disability.

Mol Diagn Ther. 22:129–138. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Li AH, Hanchard NA, Furthner D, Fernbach

S, Azamian M, Nicosia A, Rosenfeld J, Muzny D, D'Alessandro LCA,

Morris S, et al: Whole exome sequencing in 342 congenital cardiac

left sided lesion cases reveals extensive genetic heterogeneity and

complex inheritance patterns. Genome Med. 9:952017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Tarozzi M, Bartoletti-Stella A, Dall'Olio

D, Matteuzzi T, Baiardi S, Parchi P, Castellani G and Capellari S:

Identification of recurrent genetic patterns from targeted

sequencing panels with advanced data science: A case-study on

sporadic and genetic neurodegenerative diseases. BMC Med Genomics.

15:262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Iyer SV, Goodwin S and McCombie WR:

Leveraging the power of long reads for targeted sequencing. Genome

Res. 34:1701–1718. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Mandlik JS, Patil AS and Singh S:

Next-generation sequencing (NGS): Platforms and applications. J

Pharm Bioallied Sci. 16(Supp 1): S41–S45. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Flores WG and Pereira WC: A contrast

enhancement method for improving the segmentation of breast lesions

on ultrasonography. Comput Biol Med. 80:14–23. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Jelin AC and Vora N: Whole Exome

sequencing: Applications in prenatal genetics. Obstet Gyn Clin N

Am. 45:69–81. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Chen M, Chen J, Wang C, Chen F, Xie Y, Li

Y, Li N, Wang J, Zhang VW and Chen D: Clinical application of

medical exome sequencing for prenatal diagnosis of fetal structural

anomalies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 251:119–124. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Emms A, Castleman J, Allen S, Williams D,

Kinning E and Kilby M: Next generation sequencing after invasive

prenatal testing in fetuses with congenital malformations: Prenatal

or neonatal investigation. Genes (Basel). 13:15172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Qin Y, Yao Y, Liu N, Wang B, Liu L, Li H,

Gao T, Xu R, Wang X, Zhang F and Song J: Prenatal whole-exome

sequencing for fetal structural anomalies: A retrospective analysis

of 145 Chinese cases. BMC Med Genomics. 16:2622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Pauta M, Martinez-Portilla RJ and Borrell

A: Diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in fetuses with multisystem

malformations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound

Obstet Gynecol. 59:715–722. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Reches A, Hiersch L, Simchoni S, Barel D,

Greenberg R, Ben Sira L, Malinger G and Yaron Y: Whole-exome

sequencing in fetuses with central nervous system abnormalities. J

Perinatol. 38:1301–1308. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Li M, Ye B, Chen Y, Gao L, Wu Y and Cheng

W: Analysis of genetic testing in fetuses with congenital heart

disease of single atria and/or single ventricle in a Chinese

prenatal cohort. BMC Pediatr. 23:5772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Jaillard S, McElreavy K, Robevska G,

Akloul L, Ghieh F, Sreenivasan R, Beaumont M, Bashamboo A,

Bignon-Topalovic J, Neyroud AS, et al: STAG3 homozygous missense

variant causes primary ovarian insufficiency and male

non-obstructive azoospermia. Mol Hum Reprod. 26:665–677. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Chong AS, Chong G, Foulkes WD and Saskin

A: Reclassification of a frequent African-origin variant from PMS2

to the pseudogene PMS2CL. Hum Mutat. 41:749–752. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Beaman MM, Yin W, Smith AJ, Sears PR,

Leigh MW, Ferkol TW, Kearney B, Olivier KN, Kimple AJ, Clarke S, et

al: Promoter deletion leading to allele specific expression in a

genetically unsolved case of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Med

Genet A. 197:e638802025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Sarwal V, Niehus S, Ayyala R, Kim M,

Sarkar A, Chang S, Lu A, Rajkumar N, Darfci-Maher N, Littman R, et

al: A comprehensive benchmarking of WGS-based deletion structural

variant callers. Brief Bioinform. 23:bbac2212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lindstrand A, Eisfeldt J, Pettersson M,

Carvalho CMB, Kvarnung M, Grigelioniene G, Anderlid BM, Bjerin O,

Gustavsson P, Hammarsjö A, et al: From cytogenetics to

cytogenomics: Whole-genome sequencing as a first-line test

comprehensively captures the diverse spectrum of disease-causing

genetic variation underlying intellectual disability. Genome Med.

11:682019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Reurink J, Weisschuh N, Garanto A, Dockery

A, van den Born LI, Fajardy I, Haer-Wigman L, Kohl S, Wissinger B,

Farrar GJ, et al: Whole genome sequencing for USH2A-associated

disease reveals several pathogenic deep-intronic variants that are

amenable to splice correction. HGG Adv. 4:1001812023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Fadaie Z, Whelan L, Ben-Yosef T, Dockery

A, Corradi Z, Gilissen C, Haer-Wigman L, Corominas J, Astuti GDN,

de Rooij L, et al: Whole genome sequencing and in vitro splice

assays reveal genetic causes for inherited retinal diseases. NPJ

Genom Med. 6:972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Goncalves A, Fortuna A, Ariyurek Y,

Oliveira ME, Nadais G, Pinheiro J, den Dunnen JT, Sousa M, Oliveira

J and Santos R: Integrating Whole-genome sequencing in clinical

genetics: A novel disruptive structural rearrangement identified in

the dystrophin gene (DMD). Int J Mol Sci. 23:592021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Iurillo AM, Sharifi S and Jafferany M:

Artificial intelligence in dermatology: Ethical dilemmas and

diagnostic decisions. J Am Acad Dermatol. Aug 25–2025.Epub ahead of

print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Kishikawa T, Momozawa Y, Ozeki T,

Mushiroda T, Inohara H, Kamatani Y, Kubo M and Okada Y: Empirical

evaluation of variant calling accuracy using ultra-deep

whole-genome sequencing data. Sci Rep. 9:17842019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Dippenaar A, Ismail N, Heupink TH,

Grobbelaar M, Loubser J, Van Rie A and Warren RM: Droplet based

whole genome amplification for sequencing minute amounts of

purified Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA. Sci Rep. 14:99312024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Testard Q, Vanhoye X, Yauy K, Naud ME,

Vieville G, Rousseau F, Dauriat B, Marquet V, Bourthoumieu S,

Geneviève D, et al: Exome sequencing as a first-tier test for copy

number variant detection: Retrospective evaluation and prospective

screening in 2418 cases. J Med Genet. 59:1234–1240. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

International Society for Prenatal

Diagnosis; Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine; Perinatal Quality

Foundation: Joint Position Statement from the International Society

for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD), the Society for Maternal Fetal

Medicine (SMFM), and the Perinatal Quality Foundation (PQF) on the

use of genome-wide sequencing for fetal diagnosis. Prenatal Diag.

38:6–9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Haller M, Au J, O'Neill M and Lamb DJ:

16p11.2 transcription factor MAZ is a dosage-sensitive regulator of

genitourinary development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

115:E1849–E1858. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Flottmann R, Kragesteen BK, Geuer S, Socha

M, Allou L, Sowińska-Seidler A, Bosquillon de Jarcy L, Wagner J,

Jamsheer A, Oehl-Jaschkowitz B, et al: Noncoding copy-number

variations are associated with congenital limb malformation. Genet

Med. 20:599–607. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Costain G, Silversides CK and Bassett AS:

The importance of copy number variation in congenital heart

disease. NPJ Genom Med. 1:160312016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Chen X, Shen Y, Gao Y, Zhao H, Sheng X,

Zou J, Lip V, Xie H, Guo J, Shao H, et al: Detection of copy number

variants reveals association of cilia genes with neural tube

defects. PLoS One. 8:e544922013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Ehrlich L and Prakash SK: Copy-number

variation in congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev.

77:1019862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Fulcoli FG, Franzese M, Liu X, Zhang Z,

Angelini C and Baldini A: Rebalancing gene haploinsufficiency in

vivo by targeting chromatin. Nat Commun. 7:116882016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zhao Y, Wang Y, Shi L, McDonald-McGinn DM,

Crowley TB, McGinn DE, Tran OT, Miller D, Lin JR, Zackai E, et al:

Chromatin regulators in the TBX1 network confer risk for

conotruncal heart defects in 22q11.2DS. NPJ Genom Med. 8:172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Mlynarski EE, Sheridan MB, Xie M, Guo T,

Racedo SE, McDonald-McGinn DM, Gai X, Chow EW, Vorstman J, Swillen

A, et al: Copy-number variation of the glucose transporter gene

SLC2A3 and congenital heart defects in the 22q11.2 deletion

syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 96:753–764. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Lin S, Shi S, Lu J, He Z, Li D, Huang L,

Huang X, Zhou Y and Luo Y: Contribution of genetic variants to

congenital heart defects in both singleton and twin fetuses: A

Chinese cohort study. Mol Cytogenet. 17:22024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Molck MC, Simioni M, Paiva VT, Sgardioli

IC, Paoli Monteiro F, Souza J, Fett-Conte AC, Félix TM, Lopes

Monlléo I and Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL: Genomic imbalances in

syndromic congenital heart disease. J Pediatr (Rio J). 93:497–507.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Mak C, Chow PC, Liu APY, Chan KYK, Chu

YWY, Mok GTK, Leung GKC, Yeung KS, Chau AKT, Lowther C, et al: De

novo large rare copy-number variations contribute to conotruncal

heart disease in Chinese patients. NPJ Genom Med. 1:160332016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Dasouki MJ, Wakil SM, Al-Harazi O,

Alkorashy M, Muiya NP, Andres E, Hagos S, Aldusery H, Dzimiri N,

Colak D, et al: New insights into the impact of Genome-wide copy

number variations on complex congenital heart disease in Saudi

Arabia. OMICS. 24:16–28. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Lansdon LA, Dickinson A, Arlis S, Liu H,

Hlas A, Hahn A, Bonde G, Long A, Standley J, Tyryshkina A, et al:

Genome-wide analysis of copy-number variation in humans with cleft

lip and/or cleft palate identifies COBLL1, RIC1, and ARHGEF38 as

clefting genes. Am J Hum Genet. 110:71–91. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

84

|

Cao Y, Li Z, Rosenfeld JA, Pursley AN,

Patel A, Huang J, Wang H, Chen M, Sun X, Leung TY, et al:

Contribution of genomic copy-number variations in prenatal oral

clefts: A multi-center cohort study. Genet Med. 18:1052–1055. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Younkin SG, Scharpf RB, Schwender H,

Parker MM, Scott AF, Marazita ML, Beaty TH and Ruczinski I: A

genome-wide study of de novo deletions identifies a candidate locus

for non-syndromic isolated cleft lip/palate risk. BMC Genet.

15:242014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Younkin SG, Scharpf RB, Schwender H,

Parker MM, Scott AF, Marazita ML, Beaty TH and Ruczinski I: A

genome-wide study of inherited deletions identified two regions

associated with nonsyndromic isolated oral clefts. Birth Defects

Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 103:276–283. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Vong KI, Lee S, Au KS, Crowley TB, Capra

V, Martino J, Haller M, Araújo C, Machado HR, George R, et al: Risk

of meningomyelocele mediated by the common 22q11.2 deletion.

Science. 384:584–590. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Wolujewicz P, Aguiar-Pulido V, AbdelAleem

A, Nair V, Thareja G, Suhre K, Shaw GM, Finnell RH, Elemento O and

Ross ME: Genome-wide investigation identifies a rare copy-number

variant burden associated with human spina bifida. Genet Med.

23:1211–1218. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Tian T, Lei Y, Chen Y, Guo Y, Jin L,

Finnell RH, Wang L and Ren A: Rare copy number variations of planar

cell polarity genes are associated with human neural tube defects.

Neurogenetics. 21:217–225. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhai Y, Zhang Z, Shi P, Martin DM and Kong

X: Incorporation of exome-based CNV analysis makes trio-WES a more

powerful tool for clinical diagnosis in neurodevelopmental

disorders: A retrospective study. Hum Mutat. 42:990–1004. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Yang L, Wei Z, Chen X, Hu L, Peng X, Wang

J, Lu C, Kong Y, Dong X, Ni Q, et al: Use of medical exome

sequencing for identification of underlying genetic defects in

NICU: Experience in a cohort of 2303 neonates in China. Clin Genet.

101:101–109. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Sevim BC, Zhang P, Tristani-Firouzi M,

Gelb BD and Itan Y: De novo variants in exomes of congenital heart

disease patients identify risk genes and pathways. Genome Med.

12:92020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Okashah S, Vasudeva D, El Jerbi A,

Khodjet-El-Khil H, Al-Shafai M, Syed N, Kambouris M, Udassi S,

Saraiva LR, Al-Saloos H, et al: Investigation of genetic causes in

patients with congenital heart disease in Qatar: Findings from the

Sidra cardiac Registry. Genes (Basel). 13:13692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Shi X, Zhang L, Bai K, Xie H, Shi T, Zhang

R, Fu Q, Chen S, Lu Y, Yu Y and Sun K: Identification of rare

variants in novel candidate genes in pulmonary atresia patients by

next generation sequencing. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 18:381–392.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Shi X, Huang T, Wang J, Liang Y, Gu C, Xu

Y, Sun J, Lu Y, Sun K, Chen S and Yu Y: Next-generation sequencing

identifies novel genes with rare variants in total anomalous

pulmonary venous connection. EBioMedicine. 38:217–227. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Basha M, Demeer B, Revencu N, Helaers R,

Theys S, Bou Saba S, Boute O, Devauchelle B, Francois G, Bayet B

and Vikkula M: Whole exome sequencing identifies mutations in 10%

of patients with familial non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate in

genes mutated in well-known syndromes. J Med Genet. 55:449–458.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Hoebel AK, Drichel D, van de Vorst M,

Böhmer AC, Sivalingam S, Ishorst N, Klamt J, Gölz L, Alblas M,

Maaser A, et al: Candidate genes for nonsyndromic cleft palate

detected by exome sequencing. J Dent Res. 96:1314–1321. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Awotoye W, Mossey PA, Hetmanski JB, Gowans

LJJ, Eshete MA, Adeyemo WL, Alade A, Zeng E, Adamson O, James O, et

al: Damaging mutations in AFDN contribute to risk of nonsyndromic

cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J.

61:697–705. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Fu Z, Yue J, Xue L, Xu Y, Ding Q and Xiao

W: Using whole exome sequencing to identify susceptibility genes

associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft

palate. Mol Genet Genomics. 298:107–118. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Kumari P, Singh SK and Raman R: TGFβ3,

MSX1, and MMP3 as Candidates for NSCL+/-P in an Indian population.

Cleft Palate-Cran J. 56:363–372. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Renard E, Chery C, Oussalah A, Josse T,

Perrin P, Tramoy D, Voirin J, Klein O, Leheup B, Feillet F, et al:

Exome sequencing of cases with neural tube defects identifies

candidate genes involved in one-carbon/vitamin B12 metabolisms and

Sonic Hedgehog pathway. Hum Genet. 138:703–713. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Han X, Cao X, Aguiar-Pulido V, Yang W,

Karki M, Ramirez PAP, Cabrera RM, Lin YL, Wlodarczyk BJ, Shaw GM,

et al: CIC missense variants contribute to susceptibility for spina

bifida. Hum Mutat. 43:2021–2032. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Lemay P, Guyot MC, Tremblay E,

Dionne-Laporte A, Spiegelman D, Henrion É, Diallo O, De Marco P,

Merello E, Massicotte C, et al: Loss-of-function de novo mutations

play an important role in severe human neural tube defects. J Med

Genet. 52:493–497. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Chen Z, Kuang L, Finnell RH and Wang H:

Genetic and functional analysis of SHROOM1-4 in a Chinese neural

tube defect cohort. Hum Genet. 137:195–202. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Lupo PJ, Mitchell LE and Jenkins MM:

Genome-wide association studies of structural birth defects: A

review and commentary. Birth Defects Res. 111:1329–1342. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Abdellaoui A, Yengo L, Verweij KJH and

Visscher PM: 15 years of GWAS discovery: Realizing the promise. Am

J Hum Genet. 110:179–194. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Tam V, Patel N, Turcotte M, Bosse Y, Pare

G and Meyre D: Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association

studies. Nat Rev Genet. 20:467–484. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Pirruccello JP, Di Achille P, Nauffal V,

Nekoui M, Friedman SF, Klarqvist MDR, Chaffin MD, Weng LC,

Cunningham JW, Khurshid S, et al: Genetic analysis of right heart

structure and function in 40,000 people. Nat Genet. 54:792–803.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Aung N, Vargas JD, Yang C, Fung K, Sanghvi

MM, Piechnik SK, Neubauer S, Manichaikul A, Rotter JI, Taylor KD,

et al: Genome-wide association analysis reveals insights into the

genetic architecture of right ventricular structure and function.

Nat Genet. 54:783–791. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Lahm H, Jia M, Dreßen M, Wirth F, Puluca

N, Gilsbach R, Keavney BD, Cleuziou J, Beck N, Bondareva O, et al:

Congenital heart disease risk loci identified by genome-wide

association study in European patients. J Clin Invest.

131:e1418372021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

111

|

Jin SC, Homsy J, Zaidi S, Lu Q, Morton S,

DePalma SR, Zeng X, Qi H, Chang W, Sierant MC, et al: Contribution

of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart

disease probands. Nat Genet. 49:1593–1601. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Rojas-Martinez A, Reutter H,

Chacon-Camacho O, Leon-Cachon RB, Munoz-Jimenez SG, Nowak S, Becker

J, Herberz R, Ludwig KU, Paredes-Zenteno M, et al: Genetic risk

factors for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in

a Mesoamerican population: Evidence for IRF6 and variants at 8q24

and 10q25. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 88:535–537. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Alade A, Peter T, Busch T, Awotoye W,