Introduction

Glioma is the most common malignant tumor of the

nervous system, with high malignancy, fast growth, a short disease

course, ease of recurrence and a high incidence of postoperative

complications (1,2). Glioma is considered to be one of the

most challenging and drug-resistant tumors in neurosurgical

treatment (3). Thus, it is urgent

to identify novel treatments for glioblastoma (GBM).

Copper is an integrant mineral for life and an

important component of numerous vital activities, including

biological oxidation-reduction, iron metabolism, antioxidant

effects and detoxification (4).

Copper has also been reported to promote angiogenesis, which is

important for tumor progression and metastasis. Researchers have

identified a novel method of cell death, cuproptosis, that differs

from known cell death types. Direct copper binding to the fatty

acylation component of the tricarboxylic acid cycle results in

cuproptosis, causing aggregation of fatty acylated proteins and

iron loss (5). The synthesis of

sulfur cluster proteins results in proteotoxic stress, in turn

causing cell death (5). The

potential impact of copper on the development of cancer cells has

been the subject of numerous investigations (5,6).

Copper has a strong affinity for MEK1 and binds to it directly. By

activating ERK1/2 downstream, it stimulates the growth of tumors

(6). Disruption of copper

homeostasis reportedly triggers cuproptosis, thereby synergizing

with regorafenib-mediated lethal inhibition of autophagy in GBM.

Therefore, Cu2+ and regorafenib may serve a role in the

treatment of GBM by regulating autophagy and cuproptosis (7). Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1), a pivotal

determiner of cuproptosis, works by using ferredoxin reductase to

transport electrons from NADPH to cytochrome P450 (8). Unlike the majority of malignancies,

GBM multiforme, gastric adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer all

exhibit high levels of FDX1 expression (9). High FDX1 expression is inversely

related to the prognosis of patients with GBM (9). Research has reported the possibility

of reducing copper levels in patients with newly diagnosed GBM. The

safety profile is consistent with the known toxicity profile, and

primarily related to hematology, penicillamine and copper

deficiency (10). A phase II

trial of penicillamine for copper depletion and anti-angiogenic

therapy in GBM is underway (10).

Copper has also been found to induce GBM cell senescence by

downregulating B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog.

Therefore, by inducing premature senescence in GBM cells, it may

provide a useful in vitro model for the development of novel

tumor therapeutic strategies (11). Disulfiram combined with copper can

improve the efficacy of temozolomide in the treatment of GBM

(12). Cuproptosis-related genes

have also been used in tumor diagnosis. Solute carrier family 31

member 1 has been selected as a potential cuproptosis-related gene

in breast cancer because its expression was upregulated, and

exhibited the ability to predict diagnosis, prognosis and drug

response (13).

Cuproptosis-related signatures help predict prognosis and guide

treatment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (14). Cuproptosis serves an important

role in tumors, and the levels of cuproptosis, prognosis, diagnosis

and mechanisms of immune responses in different tumors warrant

further study.

EMD-1204831 was first developed and synthesized by

Merck Serono; Merck KGaA. It could highly selectively inhibit c-Met

receptor tyrosine kinase activity in both a ligand-dependent and

-independent manner (15). In

mice with ligand-dependent Hs746T and hepatocyte growth

factor-dependent U87MG cancer, EMD-1204831 treatment was associated

with potent tumor growth suppression and regression; however, to

the best of our knowledge, the specific mechanism of action is

unknown (15). Since studies of

EMD-1204831 in GBM are not precise enough, a comprehensive

mechanistic analysis of its anti-GBM action was conducted.

Materials and methods

Data collection

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and Chinese

Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA; https://www.cgga.org.cn/) were mined to collect data

of patients with GBM and clinical information, which included tumor

tissues and normal tissues from healthy controls (TCGA, TCGA-GBM;

CGGA, mRNAseq_693). The transcript information of patients with GBM

was obtained from the GSE100675 dataset in the Gene Expression

Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), including 19

control individuals and 19 patients with GBM. The transcripts per

kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads method was used for

data normalization. The CGGA dataset was used for the consensus

analysis. TCGA data were used to construct the least absolute

shrinkage and selector operator (LASSO) model. The GSE100675

dataset was used to perform differentially expressed gene (DEG)

analysis. The cuproptosis-related genes, including FDX1, LIPT1,

DLD, LIAS, dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT), PDHA1,

PDHB, MTF1, GLS and CDKN2A, were obtained from a previous study

(5).

DEG analysis

The R (R-4.2.0; https://www.r-project.org/) package limma (3.58.1;

https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html)

was used for DEG analysis. Statistically, genes were considered

significantly differentially expressed when log|fold change|≥1 and

P<0.05. Additionally, for cuproptosis-related genes in TCGA-GBM

dataset, consensus clustering was conducted using the

ConsensusClusterPlus (1.70.0; https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ConsensusClusterPlus.html)

R package, and principal component analysis was performed to

visualize the distribution of subtypes.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

After obtaining the DEGs, GSEA was performed to

assess enrichment based on Gene Ontology terms and signaling

pathways related to these genes. This process was performed using

the enrichplot (1.22.0; https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/enrichplot.html)

and clusterprofiler (4.10.0; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html)

packages in R. Enrichment results were considered statistically

significant when P<0.05.

LASSO regression analysis

A risk score model was constructed using LASSO

regression. First, univariate Cox proportional hazard regression

analysis was implemented by applying the R package survival (3.5-7;

https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html)

and genes related to overall survival (OS) were identified. Next,

to screen the most characteristic genes among them, LASSO

regression analysis was performed, where the dataset from TCGA was

selected as the training set and the dataset from CGGA was selected

as the verification set. The risk score was calculated using the

following formula: Risk score=∑(Xi x Coefi), where Xi is the

normalized expression value of the gene and Coefi is the

coefficient.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)

analysis

For scRNA-seq analysis, the Seurat package in R

(5.0.2; https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Seurat/index.html)

was used to analyze the GSM6432709 dataset from GEO (16). First, the data were preprocessed

and all batch effects were removed. The data were clustered using

the FindCluster function, and the marker genes of each cell cluster

were obtained using the Findmarkers function. The Monocle3 package

(4.1.0; https://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle3/docs/installation/)

was also used to perform pseudotemporal trajectory analysis to

explore the relationship between the prognostic genes and disease

development.

Protein level validation of central

genes

The Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/) is designed to create

human proteome-wide maps. To validate the protein expression levels

of the nine genes [AE binding protein 1 (AEBP1), NOP2/Sun RNA

methyltransferase 5 (NSUN5), MED10, CCM2 scaffold protein (CCM2),

oncostatin M receptor (OSMR), ribosomal protein L39 like (RPL39L),

EN2, collagen type XXII α1 chain (COL22A1) and DNAJC3] obtained

from the LASSO regression analysis, the protein expression levels

of target genes in the Human Protein Atlas were screened in

patients with colon, breast and lung cancer.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

To analyze immune infiltration in GBM, the dataset

was divided into high-risk and low-risk groups, and the control and

disease groups from the dataset were compared. This analysis

process was performed using the Cibersort (R script v1.04;

https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/)

algorithm. When P<0.05, the analysis results were considered

statistically significant.

DNA methylation analysis

A dataset from TCGA was used in the present study.

First, quality control and normalization analysis were performed on

the dataset (Benjamini-Hochberg correction; P<0.05).

Subsequently, differential methylation sites (Δβ values >0.1)

were obtained using the ChAMP package in R (2.36.0; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ChAMP.html).

Somatic mutation analysis

The somatic mutation data of GBM samples were

downloaded from TCGA. The mutation data were analyzed and

visualized using the maftools package in R (2.22.0; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/maftools.html).

Drug sensitivity analysis

The CellMiner tool (v2.9; https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/home.do)

was used for drug susceptibility analysis. Drugs with high

sensitivity [correlation coefficient (cor) >0.3; P<0.05] were

screened. Next, the relationship between drugs and target genes was

visualized through box plots and correlation curves.

Collection of active ingredients of

Ginseng

The Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems

Pharmacology database (TCMSP) was investigated to determine the

ingredients of Ginseng (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php). This database

includes a set of ingredients, targeted genes and pharmacokinetic

properties of natural compounds. To determine the active

ingredients of Ginseng in the database, the screening criteria

were: Oral bioavailability ≥30% and drug-likeness ≥0.18.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking tools were used to analyze the

interaction between the predicted drugs and the target genes. This

was performed using AutoDock software (v1.2.x; https://autodock.scripps.edu/), and the results were

visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer (v.19; https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download)

software.

Cell culture

The pharmacological experiments in the present study

were conducted using GBM cells. The 293T, LN229 and A172 cells

obtained from American Type Culture Collection were grown in DMEM

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

at 37°C in an incubator with 5% CO2.

Transfection

To silence COL22A1, short hairpin RNA (shRNA/sh)

specific to COL22A1 (shCOL22A1-1, 5′-GGT CTT GTT TAG AGT CTG A-3′;

shCOL22A1-2, 5′-GTC TGA GTT TGT GAG ATT A-3′) and negative control

shRNA (shNC; 5′-CAA CAA GAT GAA GAG CAC CAA-3′) were designed and

synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The 2nd generation system

was used to generate lentivirus. The shRNA was integrated into the

pLKO.1 vector (2 µg; 8453; Addgene, Inc.), and transfected

into 293T cells along with psPAX2 (1 µg; 8454; Addgene,

Inc.) and PMD2.G (1 µg; 12260; Addgene, Inc.) using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for

48 h at 37°. Viruses were collected at 48 and 72 h and filtered

using a 0.45-µm nitrocellulose filter. Polyethylene glycol

6000 was added and the viruses were concentrated by

ultracentrifugation (4°C; 1,500 × g; 30 min). Subsequently, the

virus was added to the cells for 2 days. Target cells were infected

with virus using polybrene (8 mg/ml). The multiplicity of infection

used to infect cells was 10. The next day, the cells were selected

with puromycin for 48 h (2-5 µg/ml; MilliporeSigma). The

transfection efficiencies were detected by western blotting. Next,

the cells were used for subsequent experiments. The time interval

between transduction and subsequent experimentation was ~5 days.

Puromycin (1-2 µg/ml; MilliporeSigma) was used for

maintenance.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

To study cell proliferation following drug

intervention, LN229 and A172 cells were treated with DMSO (<0.1%

v/v; HY-Y0320; MedChemExpress), kaempferol (80 µM; HY-14590;

MedChemExpress), EMD-1204831 (9 µM; HY-164394;

MedChemExpress), the combination of kaempferol (9 µM) and

EMD-1204831 (80 µM) or elesclomol (HY-12040; MedChemExpress)

for 24 h at 37°C, and CCK-8 cell viability experiments (Merck KGaA)

were conducted. First, 5,000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well

plates. Cells were collected and the CCK-8 reagent (10 µl

per well) was added at 72 h for incubation for 2 h in the dark at

37°C with 5% CO2. The VersaMax microplate reader

(Molecular Devices, LLC) was used to measure absorbance at a

wavelength of 450 nm.

Cell colony formation assay

A cell colony formation experiment was conducted to

assess cell proliferation. A total of 2×103 LN229 and

A172 cells were grown for 14 days on 6-well plates and treated with

DMSO, kaempferol (80 µM), EmdMD-1204831 (9 µM) or the

combination of both at 37°C for 24 h. When there were >50 cells

for a single cell clone, cloning was deemed complete. The cells

were then dyed with viola crystallina for 30 min at 37°C after

fixation with 10% paraformaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the clone numbers

were counted manually. The definition of colonies was >50 cells

for a single cell clone.

Transmission electron microscopy

For electron microscopy analysis, tumors were

dissected (1 mm3) in an ice-cold fixative (2.5%

glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/l PIPES buffer at pH 7.4). After 10 h of

fixation at 4°C, samples were washed with 0.1 mol/l PIPES,

post-fixed in 1% OsO4 (30 min at room temperature) and

stained in 2% uranyl acetate (1 h at room temperature). Samples

were dehydrated in an ethanol series (50, 70 and 100%) and embedded

in epoxy (37°C; overnight; 12-16 h). The tissues were divided into

~70 nm slices. The slices were observed and images were captured

with a HT-7700 transmission electron microscope.

Ki67 staining

Tumor tissues were stained using Ki67 antibody

(9027; 1:400; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and Ki67-positive

cells were counted as described previously (17). The results of Ki67 staining were

recorded as the percentage of Ki67-positive cells.

Mice

A total of 20 male BALB/c-nude mice (6 weeks;

weight, 17-21 g) from Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc. were

stochastically separated into four groups, with 5 mice in each

group. The housing conditions were as follows: Temperature,

20-26°C; humidity, 50-70%; light/dark cycle, 12 h/12 h; and feeding

food and water in the cage every day. A total of 5×106

LN229 cells were resuspended in 1 ml PBS, 8 µl

(4×104) of which were stereotactically injected into the

right hemisphere of the brain, at 0.5 mm posterior of the bregma, 2

mm to the right of the sagittal suture and 3 mm below the surface

of the skull. Deep anesthesia was used to control and treat pain

(isoflurane; induction, 4-5%; maintenance, 2%). The cells were

injected into the brain through microsyringes. When the volume of

the tumor reached 100 mm3, the four groups of mice were

treated as follows: No treatment in the control group, injection of

EMD-1204831 (10 mg/kg), injection of kaempferol (20 mg/kg) and

simultaneous injection of EMD-1204831 and kaempferol. The drugs

were injected every 2 days. The tumor cells were infected with

lentivirus generating luciferase and tumor growth was monitored by

bioluminescent imaging. Tumor volumes were measured every 4 days.

Tumors were peeled off for testing. Mice were euthanized by

intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100-200 mg/kg)

after 4 weeks. The tumors were examined by H&E staining

according to the protocol in the kit (fixation with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 6-8 h at room temperature; thickness of

sections, 5 µm; staining with haematoxylin for 4 min,

hydrochloric acid alcohol for 3 sec and eosin for 25 sec-1 min; all

staining steps were performed at room temperature; type of

microscope used, light microscope). After euthanasia, the death of

the animals was confirmed based on the disappearance of pain

response, no response when pressing the toes with hands or forceps,

and observation of cardiac and respiratory arrest. The time

interval between injection/implantation and the final tumor growth

measurement was ~28 days.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

A ROS detection kit (C10445; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to detect the levels of ROS in

LN229 and A172 glioma cell lines treated with CuCl2 and

the cuproptosis inducer elesclomol (STA-4783; MedChemExpress).

Firstly, GBM carcinoma cells in the logarithmic growth phase were

inoculated into a 12-well plate and further cultured. When the cell

density reached 40-50%, 200 nM elesclomol was added to treat the

cells for 24 h at 37°C, followed by the addition of 10 µM

ROS fluorescence probe (S0033S; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for incubation at 37°C for 20 min. Finally, flow

cytometry (BD LSRFortessa; BD Biosciences) was used to detect the

intensity of the fluorescence signals at an excitation wavelength

of 488 nm, which represented the levels of ROS (fluorescence

emission: Before lipid peroxidation, analyte detector, 581 nm,

analyte reporter, 591 nm; after lipid peroxidation, analyte

detector, 488 nm, analyte reporter, 510 nm). Lipid peroxidation was

determined by quantitating the fluorescence intensities and

calculating the ratio of intensity in the Texas Red®

channel (581/591 nm) to the intensity in the FITC channel (488/519

nm). Flowjo v9 software (BD Biosciences) was used.

Measurement of intracellular copper

A total of 2×105 LN229 and A172 GBM cells

per well in the logarithmic growth phase were inoculated into a

6-well plate and cultured for 12 h. Subsequently, cells were

incubated with different concentrations of CuCl2 (0,

0.5, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 4 and 5 µmol/l) to generate a standard

curve (data not shown) and the cuproptosis inducer elesclomol (200

nM) for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were collected and resuspended in 120

µl water. Ultrasound was used to break the cells to collect

copper ions inside the cells. Finally, copper ions inside the cells

were detected according to the instructions (E-BC-K775-M;

Elabscience Bionovation Inc.) using a microplate reader.

Western blotting

LN229 and A172 glioma cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were inoculated into a 6-well plate, and the cells

were cultured until they reached a density of 40-50%. Different

concentrations of CuCl2 (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 4 and 5

µmol/l) and the cuproptosis inducer elesclomol (200 nM) were

added to treat the cells at 37°C overnight. The cells were washed

with PBS once. Total protein was extracted from the cells with an

appropriate amount of RIPA lysis buffer (P0013C; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) and the protein concentration was measured using

a BCA kit (23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The mass of

protein loaded per lane was ~100 µg. The percentage of the

SDS-PAGE gel was 10%. The expression of proteins was detected

through western blotting. Proteins were transferred to

nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% milk

containing 2% BSA (A8020; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were incubated at

4°C overnight (12-16 h) with the primary antibodies, including

COL22A1 (1:2,000; PA5-70816; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), DLAT (1:3,000; cat. no. 13426-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase (1:10,000; cat. no.

ab177934; Abcam), FDX1 (1:2,000; cat. no. 12592-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), ACTB (1:3,000; ab8226; Abcam) and GAPDH (1:50,000;

cat. no. 60004-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) antibodies, then

washed with PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 three times, and an appropriate

amount of the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was added for

incubation at room temperature for 1 h (anti-mouse IgG; 1:5,000;

ab7068; Abcam; anti-rabbit IgG; 1:5,000; ab288151; Abcam). An ECL

kit was used for visualization (322209; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Images were captured using the BIO-RAD ChemiDoc MP

multifunctional chemical imaging instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier plots were plotted and the log-rank

test was performed to estimate and compare the OS between the two

risk groups in the training set. The Renyi test was performed to

estimate and compare the OS between the two risk groups in the

verification set. The hazard ratio and Cox P-values were generated

using Cox analysis. The correlations between different factors were

analyzed using Spearman's statistical methods. Statistical analysis

was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (Dotmatics). Data

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three

experimental repeats. An unpaired Student's t-test was used for

comparisons between two groups. Differences among multiple groups

were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Differences among multiple groups containing two variables were

analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc

analysis. The tumor volumes of mice in different drug groups were

analyzed using two-way mixed ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc

test. The immune cell infiltration based on Cibersort was analyzed

using the Wilcox rank-sum test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

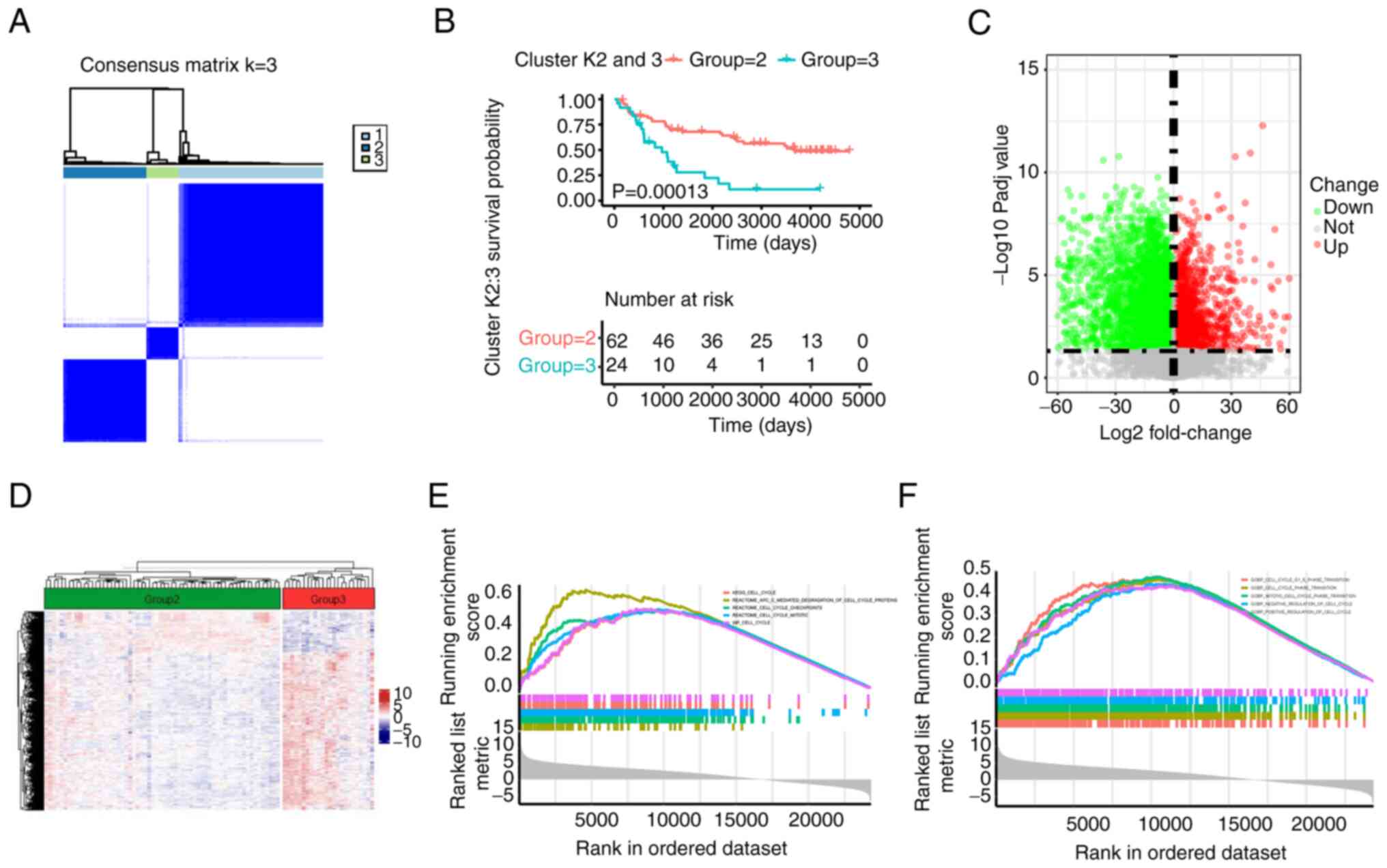

Consensus clustering of

cuproptosis-related genes in patients with GBM

Although cuproptosis has been shown to serve an

important role in GBM (9), to the

best of our knowledge, the precise mechanism of its action remains

unknown. First, the present study grouped the GBM cohort (k=3) by

consensus clustering analysis according to cuproptosis-related

genes, which means there were three cuproptosis levels (high,

middle and low; Figs. 1A, and

S1A and B). Next, different

cuproptosis levels of patients will be associated with different

outcomes. For example, high cuproptosis levels of patients are

associated with a longer OS than low cuproptosis levels (18). Therefore, to identify the high and

low groups of cuproptosis levels in patients, survival analysis for

the three groups was performed and the results revealed that the

prognosis of cluster 2 and 3 was significantly better than that of

cluster 1, and cluster 2 had a longer OS than cluster 3, thus

cluster 2 was considered as relative high level of cuproptosis and

cluster 3 as cuproptosis low level because the OS in cluster 2 was

longer than that in cluster 3 (18) (data not shown). Therefore, groups

2 and 3 were selected for comparison. The survival performance of

the former was improved according to the Kaplan-Meier analysis

(P=0.00013; Fig. 1B).

Subsequently, DEGs were compared between the two groups. As shown

in Figs. 1C and D, and S1C, a total of 6,935 DEGs were

identified, including 1,885 upregulated genes and 5,050

downregulated genes. GSEA verified that the DEGs were primarily

gathered in 'cell cycle' pathways (Figs. 1E and F, and S1D). These results suggested that the

cuproptosis-related DEGs were associated with malignant progression

of GBM.

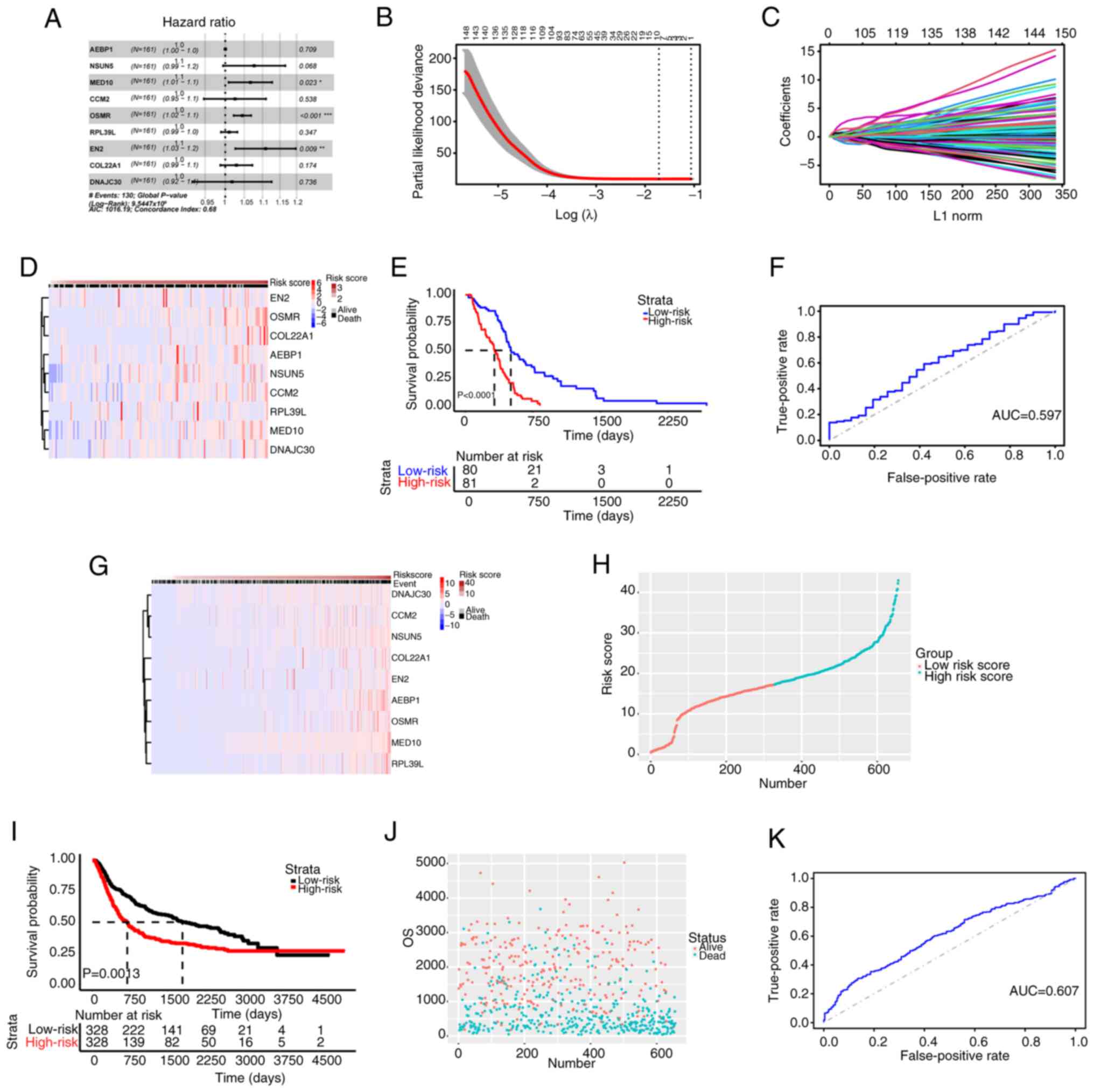

LASSO regression analysis for patients

with GBM

To ascertain the characteristic genes associated

with GBM prognosis, univariate Cox and LASSO regression analyses

were conducted for an in-depth analysis of the identified DEGs. The

candidate genes were screened by univariate Cox analysis (Fig. 2A). To eliminate analysis errors,

the dataset from TCGA was used as the training set and

characteristic prognostic genes were screened by LASSO analysis. As

shown in Fig. 2B-D, nine

prognostic genes were screened out. The risk score was calculated

as follows: Risk score=A EBP1 × 0.007204771 + NSUN5 × 0.200917630 +

MED10 × 0.257867168 + CCM2 × 0.017182529 + OSMR × 0.15343 0963 +

RPL39L × 0.019123077 + EN2 × 0.038036644 + C OL22A1 × 0.048587190 +

DNAJC30 × 0.001146385. Based on the riskscore values in the

patients with GBM from CGGA, the median value was calculated and

the patients were divided into high and low risk groups according

to the median value (Fig.

S2A-C). Furthermore, the low-risk group exhibited improved

survival performance compared with the high-risk group (Fig. 2E), and the 1-year area under the

curve (AUC) value was 0.597 (Fig.

2F). The aforementioned results were confirmed in the

validation set (Fig. 2G-K). The

aforementioned findings showed that the prognostic model in the

present study was closely associated with the prognosis of GBM and

could predict the risk score of GBM based on the assessment of the

risk score gene value of each patient.

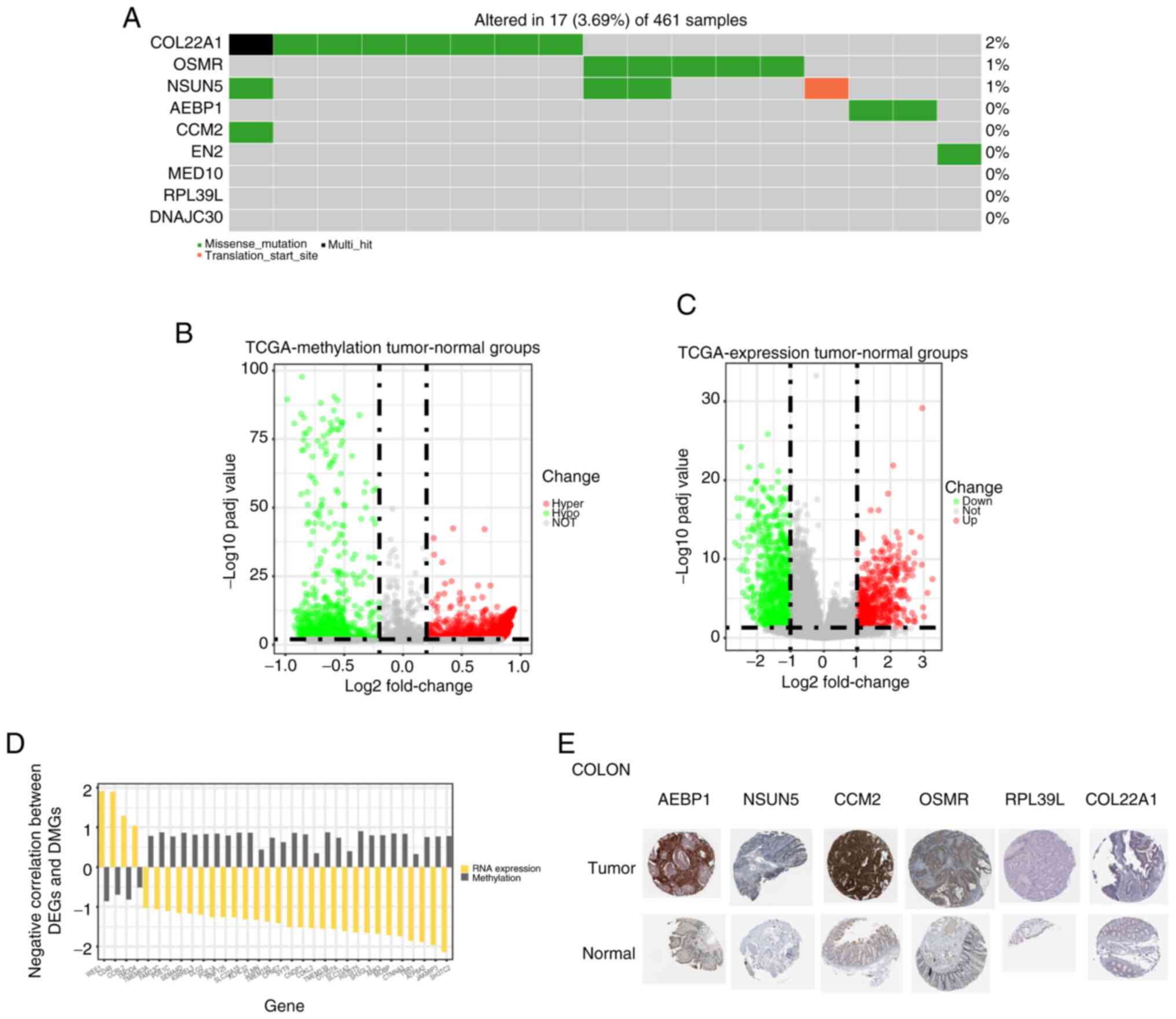

Expression profiles of risk score-related

genes

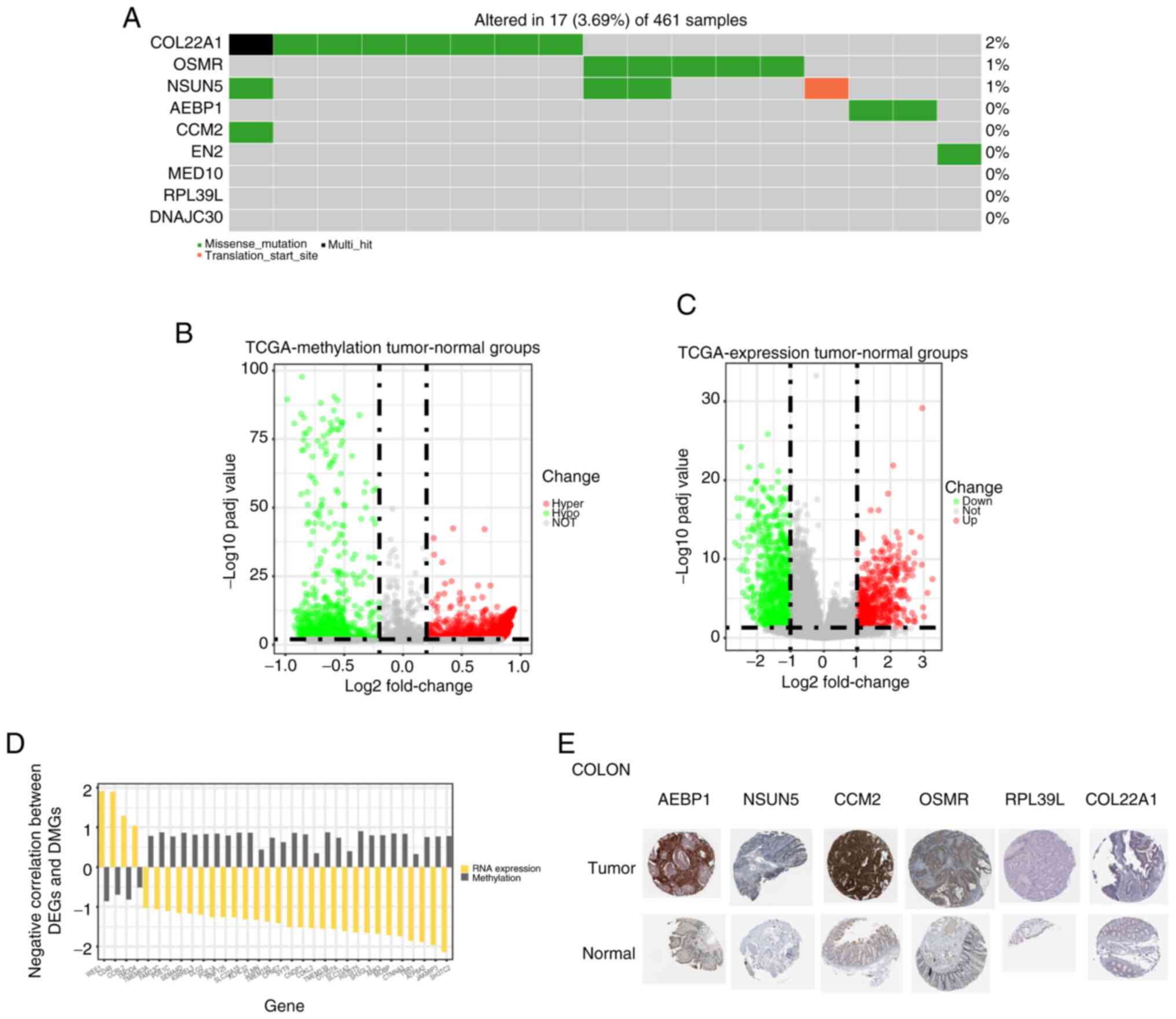

The DNA, mRNA and protein levels of these nine genes

were assessed to examine the risk score-related genes in GBM. The

DNA of COL22A1, OSMR, NSUN5, AEBP1,

CCM2 and EN2 was mutated in GBM (Fig. 3A). Additionally,

post-translational modification of DNA serves an important role in

tumor regulation, and DNA methylation is one of the most common

modification methods (19). Thus,

the differentially expressed methylated genes were compared between

the GBM group and the paracancerous group, and the methylation

levels of numerous genes were significantly different between the

two groups (Fig. 3B and D), which

caused changes in their RNA levels (Figs. 3C and S3A). Next, the Human Protein Atlas

database was queried and the protein expression levels of AEBP1,

NSUN5, CCM2, OSMR, RPL39L and COL22A1 were found to be increased to

varying degrees in tumor tissues of the colon (Fig. 3E). The result was validated in

other cancer tissues (Fig. S3B).

These results indicated that the status of most risk score-related

genes was different at the multiomics level in GBM and normal

tissues.

| Figure 3Expression profiles of risk

score-related genes. (A) Somatic mutation of nine risk

score-related genes in the dataset from TCGA. (B) Volcano plot of

differential methylation sites in the tumor and normal groups. (C)

Volcano plot of DEGs in the tumor and normal groups. (D) DEGs and

DMGs with a negative correlation in the tumor and normal groups.

(E) Representative immunohistochemistry images of six prognostic

proteins in tumor and normal tissues of the colon. Magnification,

×200. AEBP1, AE binding protein 1; CCM2, CCM2 scaffold protein;

COL22A1, collagen type XXII α1 chain; DEG, differentially expressed

gene; DMG, differentially methylated gene; NSUN5, NOP2/Sun RNA

methyltransferase 5; OSMR, oncostatin M receptor; Padj value,

adjusted P-value; RPL39L, ribosomal protein L39 like; TCGA, The

Cancer Genome Atlas. |

Somatic mutation analysis in GBM

Tumor occurrence is highly associated with DNA

mutation (9). Mutation analysis

was performed to examine DNA mutations in GBM. As shown in Fig. S4A, in the GBM group, the mutation

frequencies of PTEN, TP53, EGFR and TTN were the highest. The

mutation frequencies of the high-risk group and low-risk group were

different (Fig. S4B and C).

Therefore, the prognostic model in the present study was closely

related to DNA mutation.

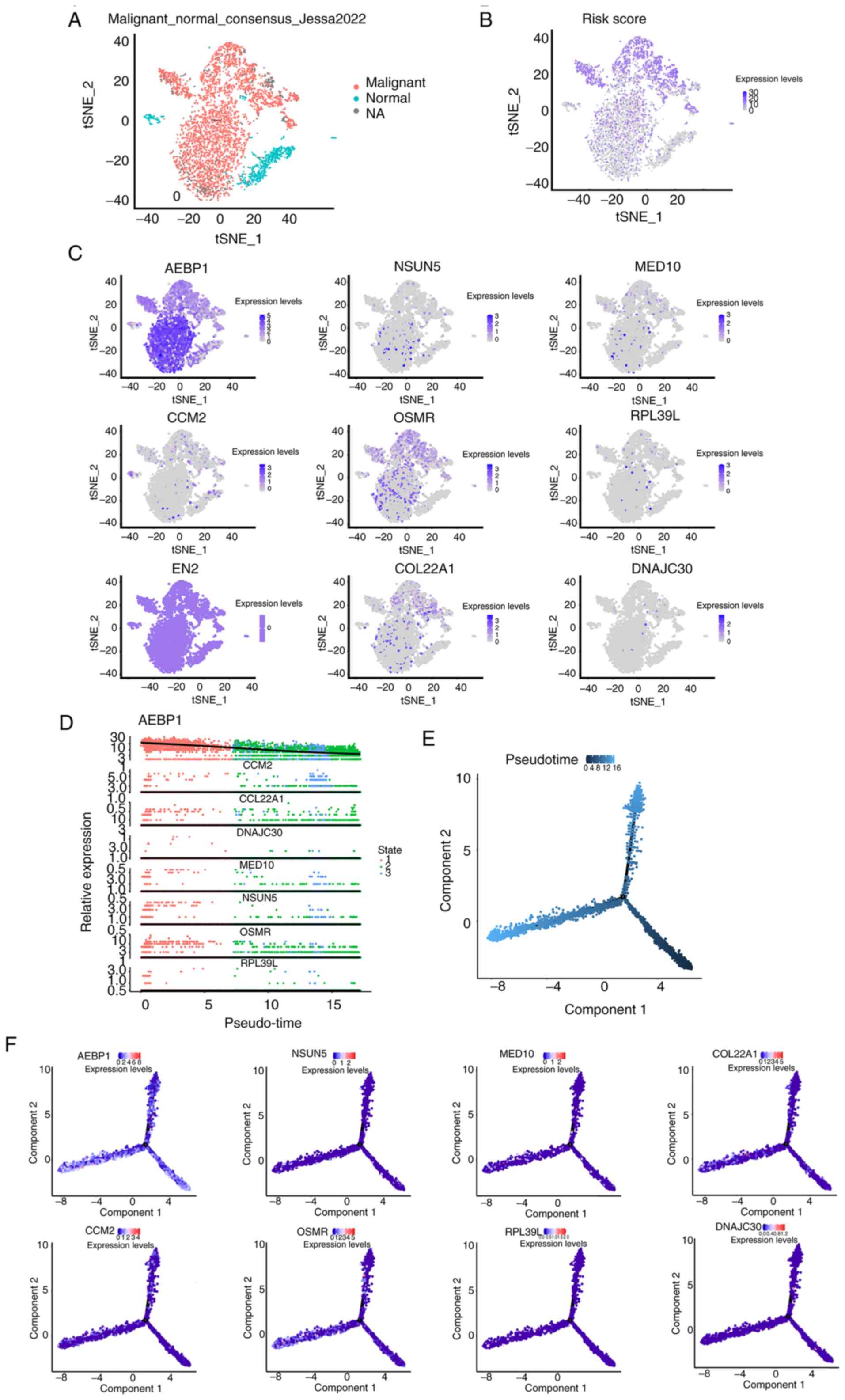

Biofunction analysis of risk

score-related genes via scRNA-seq

Subsequently, to visualize the expression of risk

score-related genes more accurately in different types of cells in

GBM tissues, scRNA-seq was performed to analyze these genes. First,

three cell populations that made up the GBM tissue were identified

(Fig. 4A). Subsequently, risk

scores of these cell populations were evaluated and risk

score-related genes were highly expressed in malignant cells, which

means that these risk score genes may exert their function mainly

by influencing tumor cells (Fig. 4B

and C). To further examine the dynamic changes in these genes

during tumor development, a pseudo-timeline analysis was performed.

As shown in Fig. 4D-F, the

expression of these genes increased with tumor development.

Simultaneously, the biomarkers based on a previous study (16) in each cell type were displayed

using a heatmap (Fig. S5). The

aforementioned findings of the scRNA-seq analysis further

demonstrated the reliability of the prognostic model.

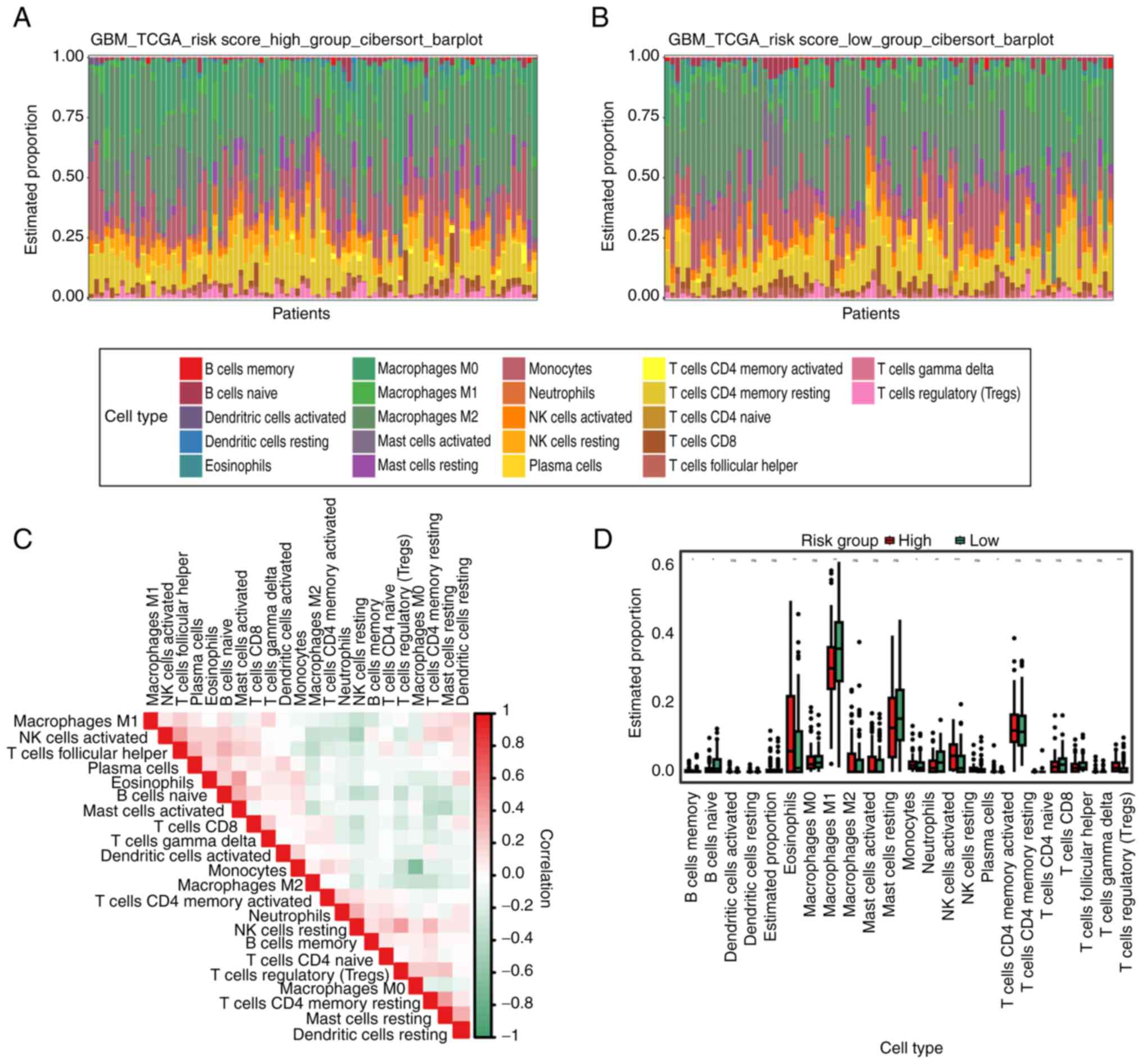

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Understanding the tumor-related immune

microenvironment is crucial for understanding the occurrence and

development of malignancies, since immune infiltration serves an

important role in their formation (13). The present study used the

Cibersort algorithm to examine the immune microenvironment in the

high-risk group, low-risk group, GBM tumor group and paracancerous

group. First, the proportions of different immune cell types in

each group were examined. The proportion of different immune cell

types in each group was analyzed, and there were significant

differences in the degree of immune invasion of some B cells,

macrophages and T cells not only in glioma and normal cells, but

also in the high-risk group and the low-risk group (Figs. 5A-D and S6A-F). Based on the aforementioned

results, it was concluded that the immune microenvironment changed

during the development of GBM, and this change was closely related

to the risk score.

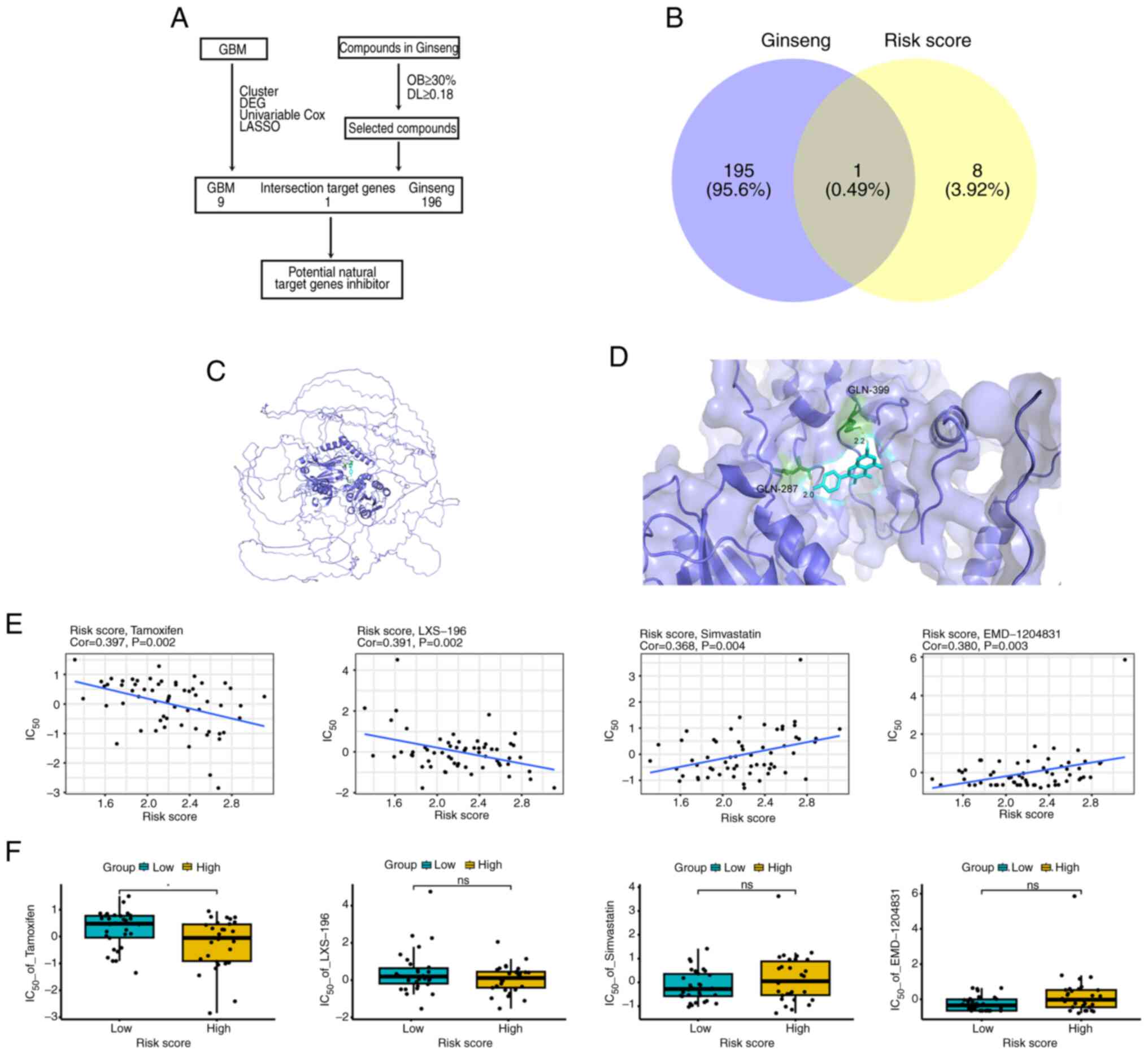

Exploration of compounds and sensitive

drugs targeting risk score-related genes

Integrative traditional Chinese and Western medicine

is a current research hotspot in tumor treatment (20-22). First, traditional Chinese medicine

(TCM) compounds targeting GBM were explored (Fig. 6A). Querying the TCMSP database

showed that the Ginseng drug could only target the COL22A1 gene in

the prognostic model (the other genes in the model could not be

targeted by Ginseng), and the active ingredient was kaempferol

(Fig. 6B). Fig. 6C shows the simulated binding

sites. Further molecular docking analysis helped calculate the

combining ability of the active ingredient and the targeted gene.

The results were as follows: Kaempferol and COL22A1 score, -6.5

kcal/mol (Fig. 6D). To explore

the therapeutic implications of the prognostic model, the risk

score-related genes were subjected to a CellMiner drug sensitivity

examination. The outcomes demonstrated that 386 medications were

related to the prediction model risk score (P<0.05;

|cor|>0.3). The drug tamoxifen exhibited a significant

correlation and effect, while other drugs had no significant effect

(Figs. 6E and F, and S7A and B). The results indicated that

the COL22A1 gene in the prognostic model could be targeted by

several drugs, suggesting that it possessed potential therapeutic

significance.

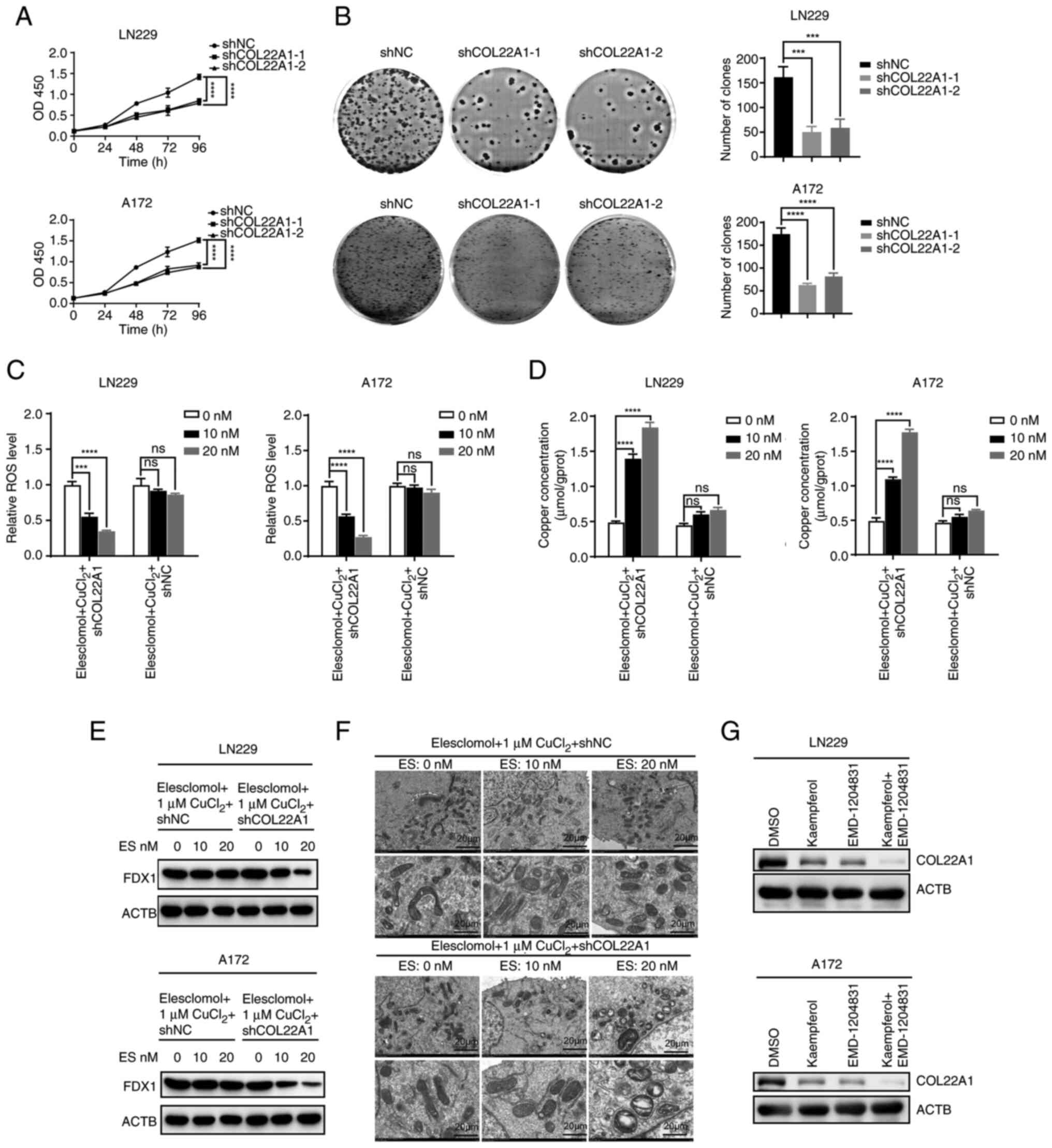

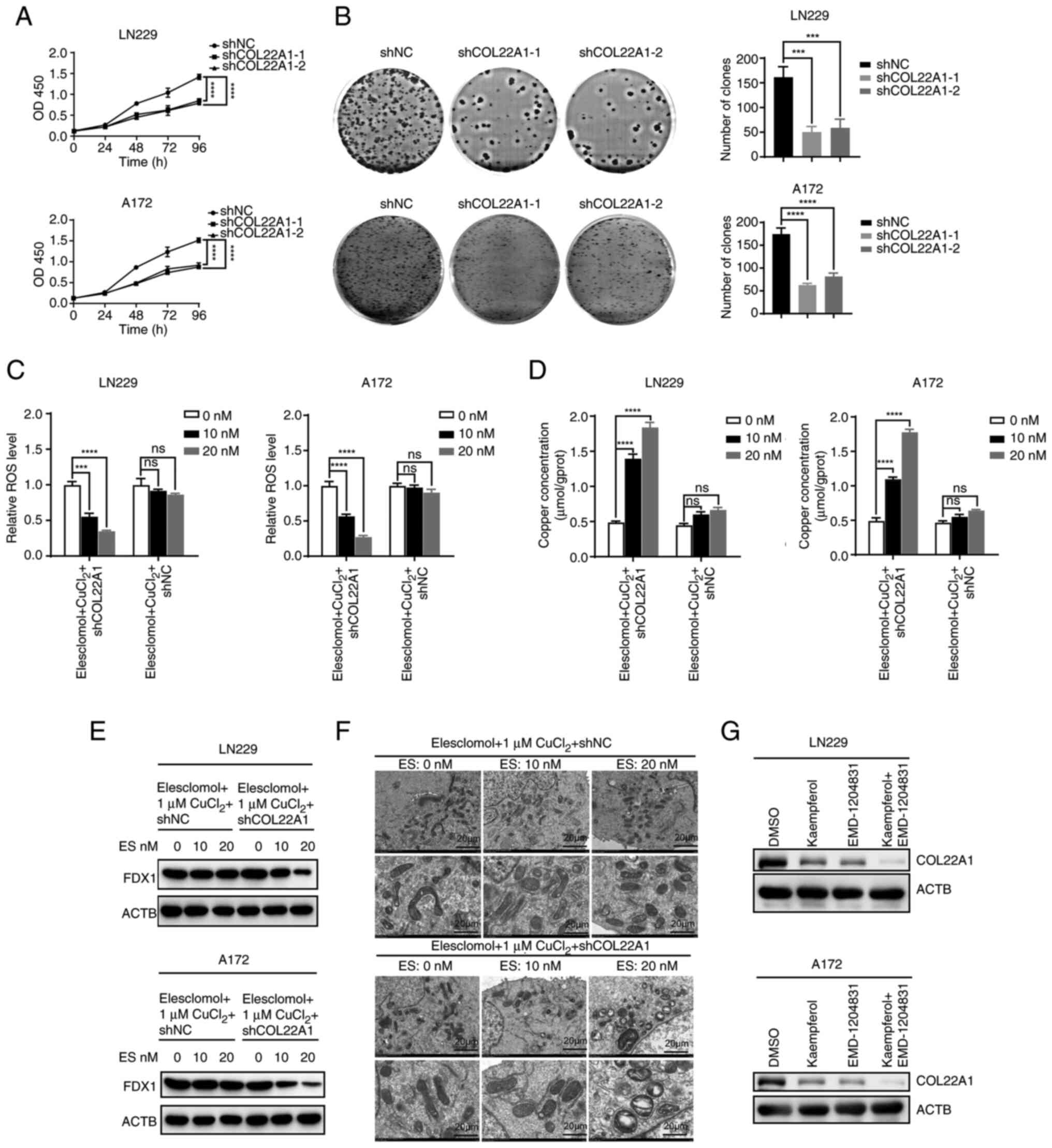

Silencing COL22A1 enhances GBM

cuproptosis

To verify the role of COL22A1 in the development of

GBM, proliferation was detected using CCK-8 and colony formation

assays, and the results demonstrated that inhibiting COL22A1

significantly decreased the proliferation and colony formation of

GBM (Figs. 7A and B, and S8C and D). To further investigate the

effect of COL22A1 on GBM cuproptosis, ROS levels were detected by

flow cytometry. Low concentrations of elesclomol reduced ROS levels

in the COL22A1 knockdown group, while this was not observed in the

shNC group (Figs. 7C, and

S8E and F). Copper

concentrations were measured in the same groups, and the results

were consistent with the aforementioned results; low concentrations

of elesclomol significantly increased copper concentrations in the

COL22A1 knockdown group, while this was not observed in the shNC

group (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, the

protein levels of the representative marker (FDX1) of cuproptosis

were detected after knocking down COL22A1. The results showed that

the levels of the downstream proteins of cuproptosis were decreased

in shCOL22A1 cells treated with low concentrations of elesclomol

compared with the shNC group (Fig.

7E). Similarly, transmission electron microscopy showed that

low concentrations of elesclomol caused mitochondrial shrinkage in

the shCOL22A1 group, which was not observed in shNC group (Fig. 7F). In conclusion, knockdown of

COL22A1 promoted cuproptosis in GBM. Notably, EMD-1204831 and

kaempferol inhibited COL22A1 expression, and the effect was greater

when used in combination (Fig.

7G). Therefore, future studies should focus on the effect of

the combination of EMD-1204831 and kaempferol on GBM development

and cuproptosis.

| Figure 7Silencing of COL22A1 enhances

glioblastoma cuproptosis. (A) Cell Counting Kit-8 assays were

performed in shNC and shCOL22A1 LN229 and A172 cell lines. (B)

Colony formation assays were performed in shNC and shCOL22A1 LN229

and A172 cell lines. (C) ROS levels of shNC and shCOL22A1 LN229 and

A172 cells exposed to increasing doses of elesclomol for 24 h. (D)

Concentration of copper following exposure to increasing doses of

elesclomol for 24 h in shNC and shCOL22A1 LN229 and A172 cell

lines. (E) Western blotting detecting the representative marker

(FDX1) of cuproptosis in shNC or shCOL22A1 LN229 and A172 cells

following exposure to increasing doses of elesclomol for 24 h. (F)

Transmission electron microscopy images were captured following

exposure to increasing doses of elesclomol for 24 h in shNC or

shCOL22A1 LN229 cells. Scale bar, 20 µm. (G) Protein levels

of COL22A1 in LN229 and A172 cells treated with DMSO or kaempferol

combined with EMD-1204831 examined by western blotting. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD of three experiments.

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. controls.

ACTB, actin β; COL22A1, collagen type XXII α1 chain; ES,

elesclomol; FDX1, ferredoxin 1; NC, negative control; ns, not

significant; OD, optical density; ROS, reactive oxygen species; sh,

short hairpin RNA. |

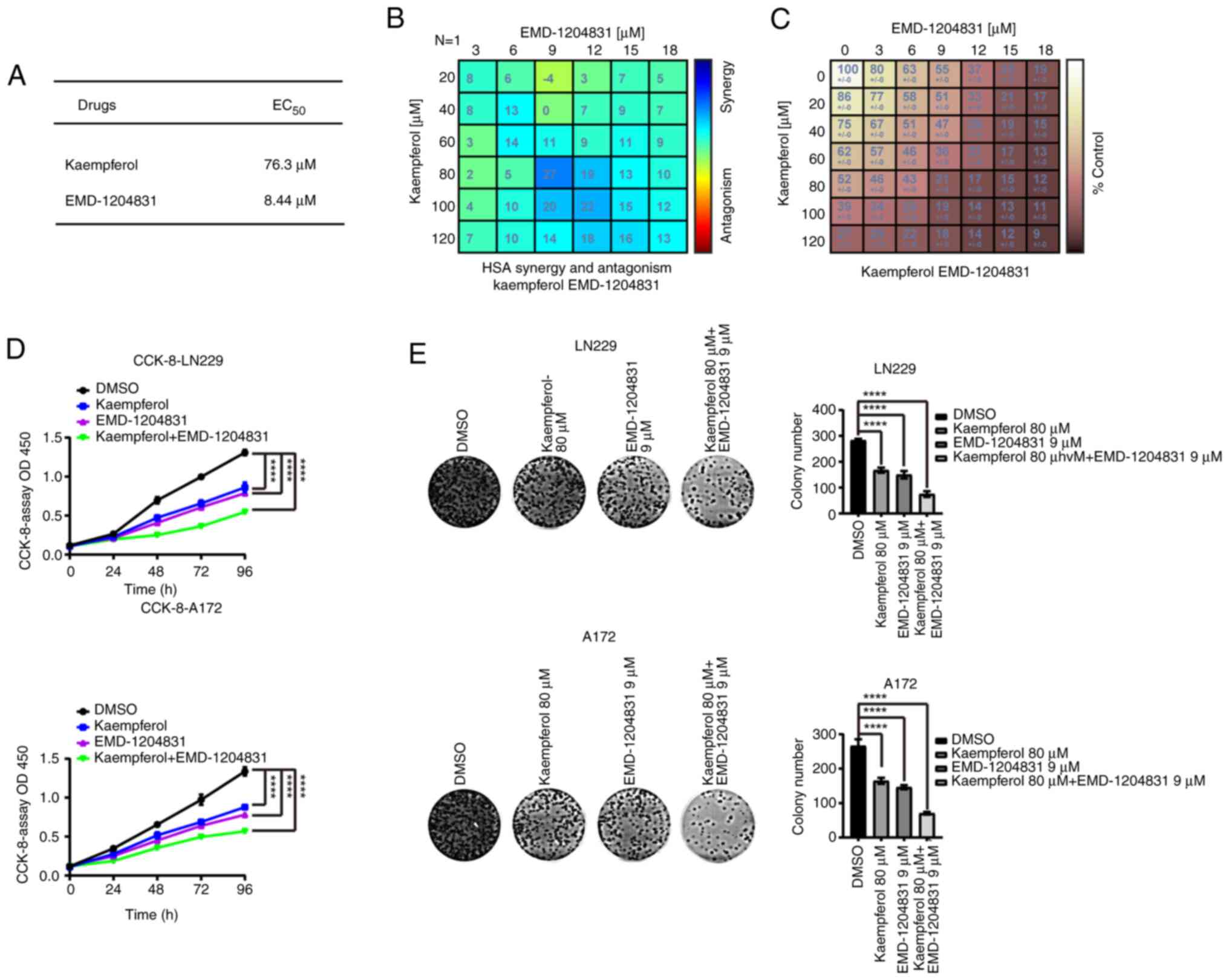

EMD-1204831 and kaempferol

synergistically treat GBM

The median effect concentration values of the two

drugs were obtained through CCK-8 experiments in LN229 cells

(Figs. 8A, and S8A and B). Subsequently, EMD-1204831

and kaempferol were used for treatment intervention in LN229 and

A172 cells. The cell viability assay showed that the combined drugs

reduced the cell activity more effectively than either drug alone,

and their best concentrations of combination were determined

(kaempferol, 80 µM; EMD-1204831, 9 µM) (Fig. 8B-D). Furthermore, the same results

were obtained in colony formation assays (Fig. 8E). In order to further explore the

combination effect of EMD-1204831 and kaempferol, LN229 cells were

first injected into nude mice to prepare xenograft tumor models.

The nude mice were divided into four groups, namely the vehicle,

EMD-1204831, kaempferol and combination treatment groups. Compared

with the vehicle group, the tumor volume and mass of the two groups

of mice treated with either kaempferol or EMD-1204831 alone were

reduced, while the tumor inhibition effect of the combined

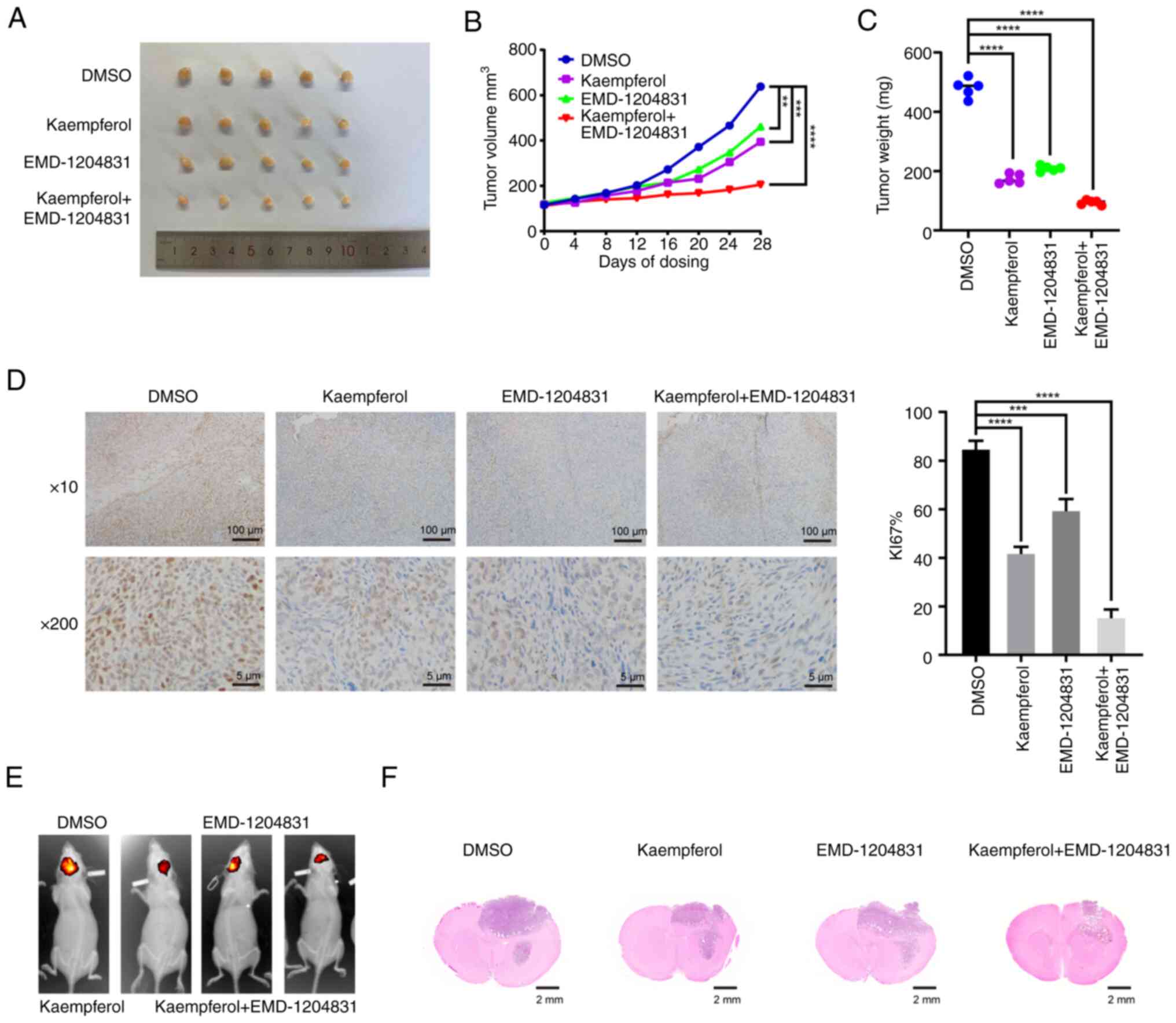

treatment group was the most obvious (Fig. 9A-C). After 4 weeks of treatment,

tumor tissues were collected and Ki67 was examined. The proportion

of positive tumor cells in the single drug groups was lower than

that in the vehicle group, while the inhibitory effect in the

combined drug group was greater (Fig.

9D). The results of the intracranial tumorigenesis experiment

in mice were consistent with the results of the present in

vitro experiments; the tumor size was smaller in the combined

drug group than in the control and single drug groups (Fig. 9E and F). The aforementioned

results indicated that the combination of EMD-1204831 and

kaempferol had therapeutic effects on GBM both in vivo and

in vitro.

Combination of EMD-1204831 and kaempferol

sensitizes GBM to cuproptosis inducers

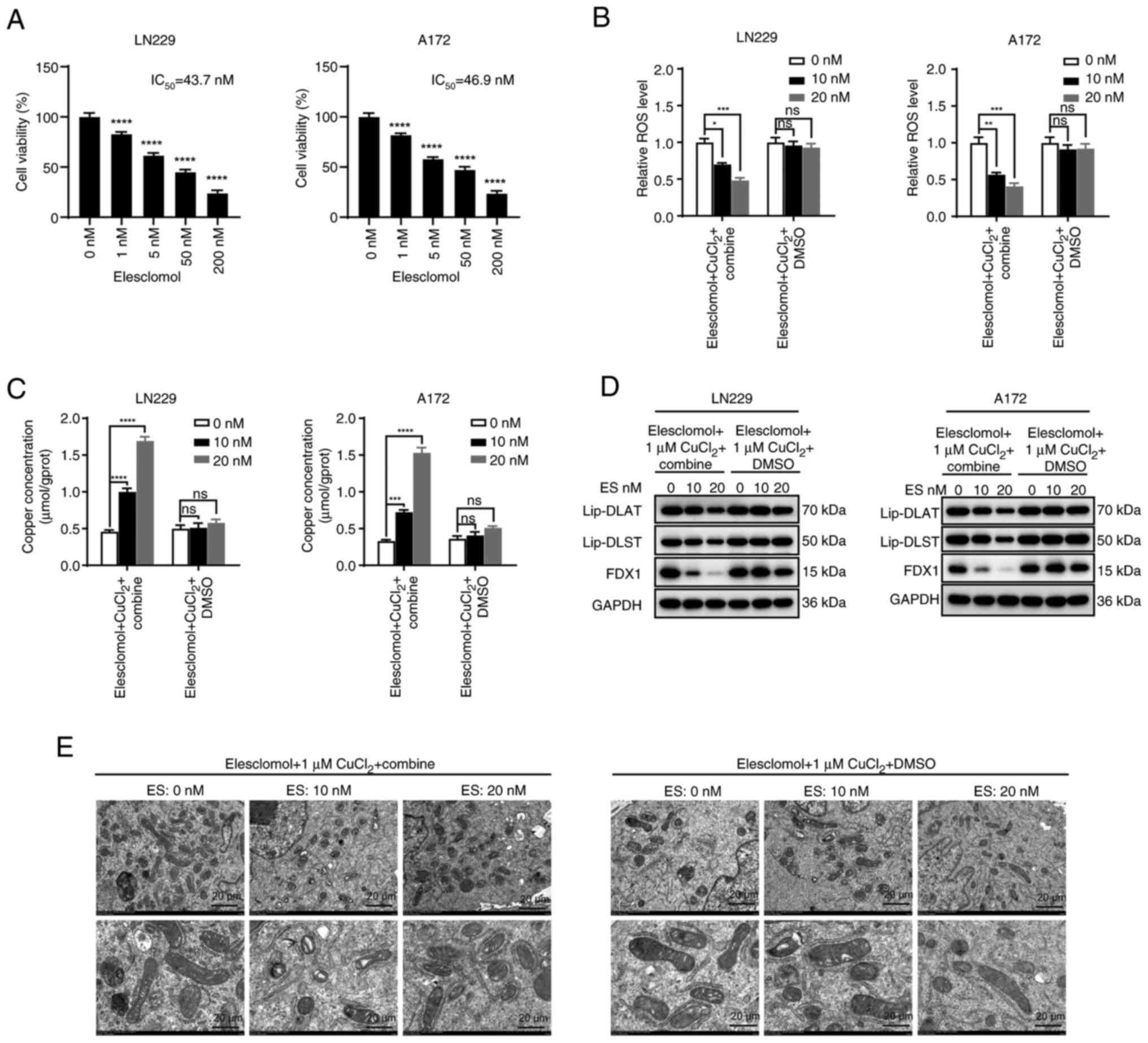

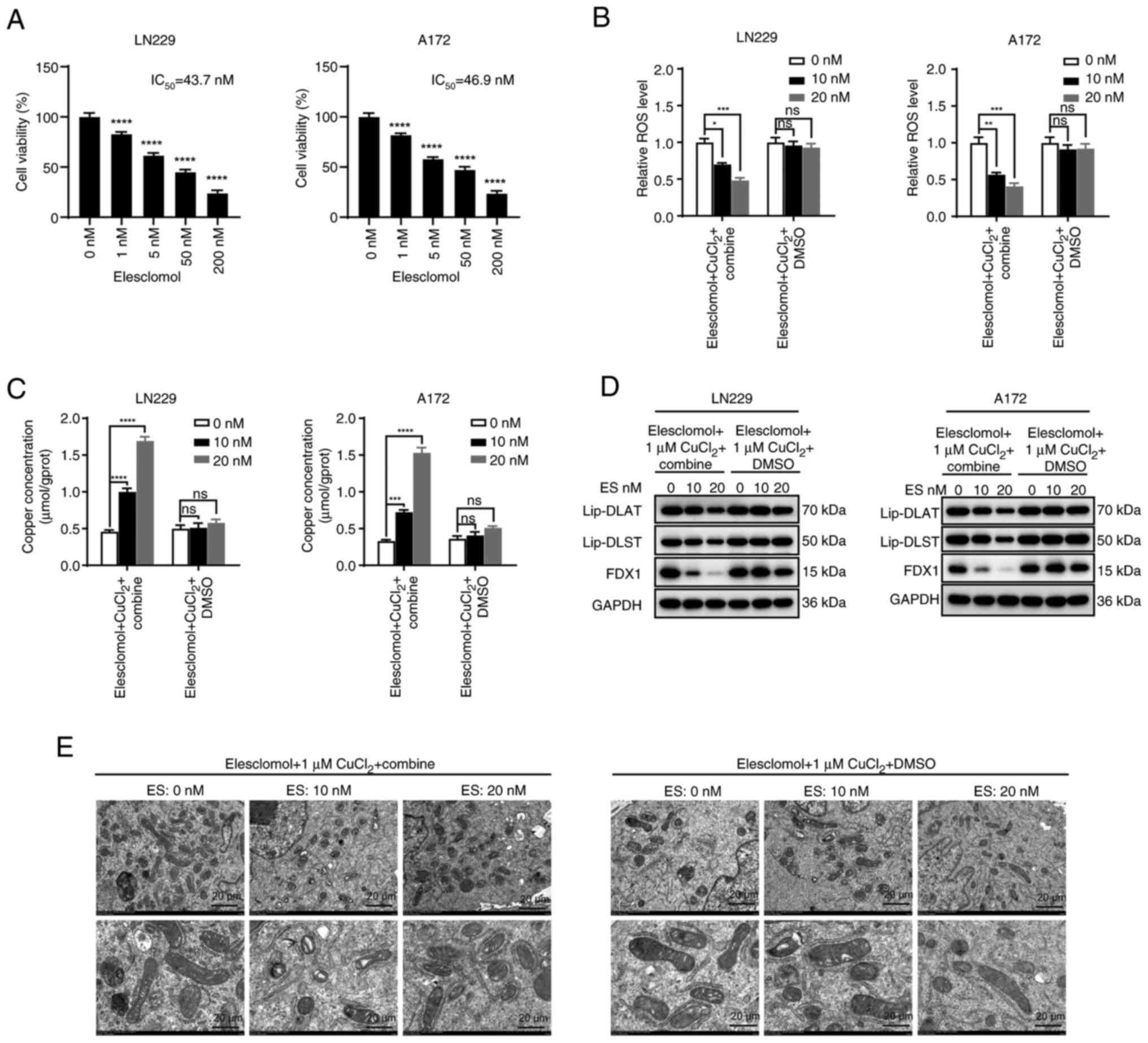

To clarify the effect of the combination of the two

drugs on cuproptosis, the IC50 of the

cuproptosis-inducer elesclomol was determined in GBM cell lines

using a CCK-8 assay (Fig. 10A).

Then, low concentrations of elesclomol (10 and 20 nM) were added in

the control group and the combination group. The results of flow

cytometry showed that the changes in ROS levels were not

significant in the control group induced by low concentrations of

elesclomol. Conversely, low concentrations of elesclomol in the

combination group (EMD-1204831 and kaempferol) significantly

reduced ROS levels (Figs. 10B,

and S8G and H). To further

verify that the changes in ROS levels were related to cuproptosis,

copper concentrations and cuproptosis checkpoint proteins were

examined in both groups, and the results were consistent with the

aforementioned results; compared with the DMSO group, the

combination group exhibited increased copper concentrations and

cuproptosis (the expression levels of FDX1 could reflect the levels

of cuproptosis) (Fig. 10C and

D). Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy showed that

low concentrations of elesclomol caused mitochondrial shrinkage in

the combination group, which was not observed in the DMSO group

(Fig. 10E). In conclusion, the

combination of EMD-1204831 and kaempferol increased the sensitivity

of GBM to cuproptosis inducers.

| Figure 10Combination of EMD-1204831 and

kaempferol sensitizes glioblastoma to cuproptosis inducers. (A)

Cell viability of LN229 and A172 cells following exposure to

increasing doses of elesclomol for 24 h. (B) ROS level of LN229 and

A172 cells treated with DMSO or kaempferol combined with

EMD-1204831 while exposed to increasing doses of elesclomol for 24

h. (C) Concentration of copper following exposure to increasing

doses of elesclomol for 24 h in LN229 and A172 cells treated with

DMSO or kaempferol combined with EMD-1204831. (D) Representative

markers of cuproptosis in LN229 and A172 cells treated with DMSO or

kaempferol combined with EMD-1204831 while exposed to increasing

doses of elesclomol for 24 h examined by western blotting. (E)

Transmission electron microscopy images captured following exposure

to increasing doses of elesclomol for 24 h in LN229 cells treated

with DMSO or kaempferol combined with EMD-1204831. Scale bar, 20

µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three

experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. control.

DLAT, dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase; DLST, dihydrolipoamide

S-succinyltransferase; ES, elesclomol; FDX1, ferredoxin 1; Lip,

lipoylation; ns, not significant; ROS, reactive oxygen species. |

Discussion

More than half of all gliomas are GBM, the most

common primary malignant central nervous system tumor and the most

aggressive, with the worst clinical prognosis (1). The standard treatment for GBM is

based on surgery, combined with comprehensive treatments, including

radiotherapy and chemotherapy; however, their efficacy is limited,

with a median survival of 14-16 months (23,24). Cuproptosis is a recently reported

novel form of death caused by excessive copper levels; however, the

specific molecular mechanism of copper ion-induced cell death has

not been elucidated (25).

Cuproptosis can induce tumor cell death, including GBM cell death;

however, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown and

warrant investigation (4).

Exploring the molecular mechanisms by which copper toxicity leads

to cell death is expected to provide a deeper understanding of

copper imbalance in human diseases and the development of treatment

strategies. Using LASSO regression analysis, a prediction model of

genes linked to cuproptosis in GBM was created. In parallel, the

relationship between the GBM risk score and methylation, DNA

mutation or scRNA-seq data was investigated. The results of the

multiomics analysis showed that the prognostic pattern was

associated with the immune microenvironment, and kaempferol and

EMD-1204831 had a collaborative inhibitory effect on GBM cells. The

present findings provide a novel predictive model for the diagnosis

of GBM based on cuproptosis-related genes, and novel targets and

potential therapeutic options for its treatment.

Cluster analysis was adopted according to the

expression levels of cuproptosis genes in GBM to obtain different

cuproptosis expression level groups. Subsequently, DEG analysis and

Cox proportional hazards model analysis between the two groups of

patients were performed, the acquired genes were examined by LASSO

regression, and the risk score genes were used to establish a

prognostic model related to cuproptosis in GBM. A total of nine

genes, including AEBP1, NSUN5, MED10,

CCM2, OSMR, RPL39L, EN2, COL22A1

and DNAJC30, were related to GBM. The fibril-associated

collagens with interrupted triple-helices protein family is

represented structurally by the collagen encoded by the COL22A1

gene on human chromosome 8q24.2. The extracellular matrix protein

known as collagen XXII, a unique gene product, is exclusively found

at tissue junctions in the skin, muscle, articular cartilage, heart

and tendon. At the tendon junction, collagen XXII is deposited in

the basement membrane region (26). Transcriptional regulation of

COL22A1 suppresses nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell senescence through

G1/S arrest (27).

High proliferation and recurrence rates of squamous cell carcinoma

of the head and neck are positively associated with high COL22A1

expression, which can be used as a prognostic indicator for this

tumor, and COL22A1 is also closely related to the prognosis of

osteosarcoma (28,29). A pooled analysis or Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis was performed for these nine genes in the

training and validation sets to calculate AUC values and it was

verified that the risk scores of the predictive models were

consistent with the condition of patients, which means this

prognostic model could predict the survival status of patients.

Overall, different approaches were taken in both the training set

and validation set to check the usefulness and reliability of the

model.

scRNA-seq technology refers to high-throughput

sequencing of genetic information such as the genome, transcriptome

and epigenome at the single-cell level. scRNA-seq reflects the

heterogeneity and genetic information of rare cells that cannot be

obtained by sequencing mixed samples. It reveals the gene structure

and gene expression status of individual cells and provides more

detailed information on individual cells (30). The status of immune cell

heterogeneity was investigated by scRNA-seq (31). The application and development of

scRNA-seq technology is a novel method to develop treatments for

neurodegenerative diseases and identify targets and biomarkers

(32). GBM samples were sorted

into malignant, normal and no classification groups based on

scRNA-seq data. Among the three groups, the highest risk score was

observed in the malignant group, whereby the risk score could

assess tumor development and progression. Next, a timeline analysis

of risk scores and associated genes was performed, which showed

that risk scores and associated genes gradually increased with

tumor progression. The aforementioned results demonstrated that the

present prognostic model could predict tumor occurrence to some

extent.

Chemosensitivity analysis revealed a strong

association between risk score-related genes and the drug

susceptibility of several widely used chemotherapeutic medications.

The present study also revealed that the risk score exhibited an

obvious correlation with EMD-1204831 indicating that this drug may

be useful in treating GBM based on the prognostic model.

Furthermore, the present experiments also verified this

association. EMD-1204831 treatment is associated with potent tumor

growth suppression and regression; however, to the best of our

knowledge, the specific mechanism of action is unknown (15,33). The present study attempted to

investigate combination therapy based on integrative traditional

Chinese and Western medicine. Therefore, drug sensitivity, network

pharmacology and molecular docking analyses were performed, and

only COL22A1 could be targeted by EMD-1204831 and kaempferol

simultaneously, according to the overlap between the prognostic

genes and the genes targeted by Ginseng. Although COL22A1 was not

the most markedly altered protein compared with in normal tissues

based on immunohistochemistry data, it was selected for further

study. Kaempferol was found to target the COL22A1 protein in

prognostic models based on molecular docking and network

pharmacology analyses. Kaempferol is a natural compound and the

most common flavonoid found widely in vegetables and fruits

(34,35). Kaempferol and its glycosylated

derivatives have been shown to have numerous functions, including

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer,

cardioprotective, neuroprotective, antidiabetic, anti-osteoporotic,

estrogenic/antiestrogenic, anxiolytic, analgesic and antiallergic

activities (36). Several

anticancer effects of kaempferol have been reported, including in

breast cancer, gastric cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer,

cervical cancer, colon cancer, liver cancer, lung cancer, ovarian

cancer and leukemia (37-39). Kaempferol can also inhibit the

invasion/migration of GBM cells by inhibiting

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced protein kinase

Cα/ERK/NF-κB activation, migration and MMP-9 activation (40). Since the studies of kaempferol and

EMD-1204831 in GBM are not precise enough, a comprehensive

mechanistic analysis of their anti-GBM action was conducted. The

two drugs synergistically inhibited the proliferation of GBM cells.

Through cluster analysis and LASSO regression analysis, the

prognostic cuproptosis-related genes in GBM were identified.

Furthermore, the drugs EMD-1214063 and kaempferol could target one

of the aforementioned genes, COL22A1, simultaneously based on the

drug sensitivity analysis and network pharmacology. Therefore, we

hypothesized that these two drugs exert their function through the

same target and validated their synergistic effect in subsequent

experiments. EMD-1204831 is a c-Met inhibitor that has been

reported to inhibit cancer cell proliferation (14); however, to the best of our

knowledge, its mechanism of action has not been studied. As one of

the natural flavonoids, kaempferol is often considered to inhibit

tumors (36,41). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the application of kaempferol in GBM has not yet been

reported. Kaempferol, the main ingredient in natural medicine, has

no clearly-defined purpose (36,37). In summary, the present study has

found a reliable method for the potential treatment of GBM and a

theoretical basis for the treatment of GBM based on integrated

traditional Chinese and Western medicine.

In conclusion, the purpose of the present study was

to investigate the important role of cuproptosis in the diagnosis

and treatment of GBM. First, a cuproptosis-related prediction model

was constructed using bioinformatics analysis. The results of

single-cell sequencing analysis showed that the risk score

calculated by the prognostic model was higher in malignant GBM cell

clusters and increased with the progression of malignant tumors.

The multiomics analysis revealed that the prognostic pattern was

strongly associated with immune system infiltration, DNA

methylation and mutations. The combination of kaempferol and

EMD-1204831 exhibited improved treatment efficiency in inhibiting

GBM progression.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC was involved in conceptualization, performed

experiments and wrote the original draft. HX and HP confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. YZ was involved in

conceptualization and funding acquisition. HY, QL, RS, JS, HL and

JL performed experiments. HX performed experiments, revised and

edited the manuscript, and acquired funding. HP performed

experiments, acquired funding and supervised the study. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was carried out in strict

accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and

Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All

procedures that involved animals were approved by the Experimental

Animal Ethics Committee: China Medical University (approval no.

CMUXN2023010; approval date, March 9, 2023; Shenyang, China). All

surgery was performed under isoflurane anesthesia, and all efforts

were made to minimize suffering.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma

|

|

FDX1

|

ferredoxin 1

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

GSEA

|

gene set enrichment analysis

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Key Research and

Development Project of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2018225040),

the Science and Technology Planning Project of Shenyang (grant no.

22-321-33-50), the Special Fund for Clinical Research of Wu Jieping

Medical Foundation (grant no. 320.6750.2023-17-13) and the Natural

Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (grant no.

2023-BS-046).

References

|

1

|

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Rouse C,

Chen Y, Dowling J, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan J:

CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system

tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007-2011. Neuro Oncol.

16(Suppl 4): iv1–iv63. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Salcman M: Glioblastoma multiforme. Am J

Med Sci. 279:84–94. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE and

Kruchko C: CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central

nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009.

Neuro Oncol. 14(Suppl 5): v1–v49. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, Dooley JS and

Schilsky ML: Wilson's disease. Lancet. 369:397–408. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kahlson MA and Dixon SJ: Copper-induced

cell death. Science. 375:1231–1232. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Grasso M, Bond GJ, Kim YJ, Boyd S, Matson

Dzebo M, Valenzuela S, Tsang T, Schibrowsky NA, Alwan KB, Blackburn

NJ, et al: The copper chaperone CCS facilitates copper binding to

MEK1/2 to promote kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 297:1013142021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jia W, Tian H, Jiang J, Zhou L, Li L, Luo

M, Ding N, Nice EC, Huang C and Zhang H: Brain-targeted HFn-Cu-REGO

nanoplatform for site-specific delivery and manipulation of

autophagy and cuproptosis in glioblastoma. Small. 19:e22053542023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tsvetkov P, Detappe A, Cai K, Keys HR,

Brune Z, Ying W, Thiru P, Reidy M, Kugener G, Rossen J, et al:

Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress.

Nat Chem Biol. 15:681–689. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yang L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Jiang P, Liu F

and Feng N: Ferredoxin 1 is a cuproptosis-key gene responsible for

tumor immunity and drug sensitivity: A pan-cancer analysis. Front

Pharmacol. 13:9381342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Brem S, Grossman SA, Carson KA, New P,

Phuphanich S, Alavi JB, Mikkelsen T and Fisher JD; New Approaches

to Brain Tumor Therapy CNS Consortium: Phase 2 trial of copper

depletion and penicillamine as antiangiogenesis therapy of

glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 7:246–253. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li Y, Hu J, Guan F, Song L, Fan R, Zhu H,

Hu X, Shen E and Yang B: Copper induces cellular senescence in

human glioblastoma multiforme cells through downregulation of

Bmi-1. Oncol Rep. 29:1805–1810. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lun X, Wells JC, Grinshtein N, King JC,

Hao X, Dang NH, Wang X, Aman A, Uehling D, Datti A, et al:

Disulfiram when combined with copper enhances the therapeutic

effects of temozolomide for the treatment of glioblastoma. Clin

Cancer Res. 22:3860–3875. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li X, Ma Z and Mei L: Cuproptosis-related

gene SLC31A1 is a potential predictor for diagnosis, prognosis and

therapeutic response of breast cancer. Am J Cancer Res.

12:3561–3580. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang Z, Zeng X, Wu Y, Liu Y, Zhang X and

Song Z: Cuproptosis-related risk score predicts prognosis and

characterizes the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Front Immunol. 13:9256182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bladt F, Faden B, Friese-Hamim M, Knuehl

C, Wilm C, Fittschen C, Grädler U, Meyring M, Dorsch D, Jaehrling

F, et al: EMD 1214063 and EMD 1204831 constitute a new class of

potent and highly selective c-Met inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res.

19:2941–2951. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jessa S, Mohammadnia A, Harutyunyan AS,

Hulswit M, Varadharajan S, Lakkis H, Kabir N, Bashardanesh Z,

Hébert S, Faury D, et al: K27M in canonical and noncanonical H3

variants occurs in distinct oligodendroglial cell lineages in brain

midline gliomas. Nat Genet. 54:1865–1880. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Arnone AA, Tsai YT, Cline JM, Wilson AS,

Westwood B, Seger ME, Chiba A, Howard-McNatt M, Levine EA, Thomas

A, et al: Endocrine-targeting therapies shift the breast microbiome

to reduce estrogen receptor-α breast cancer risk. Cell Rep Med.

6:1018802025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wu Z, Li W, Zhu H, Li X, Zhou Y, Chen Q,

Huang H, Zhang W, Jiang X and Ren C: Identification of

cuproptosis-related subtypes and the development of a prognostic

model in glioma. Front Genet. 14:11244392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nishiyama A and Nakanishi M: Navigating

the DNA methylation landscape of cancer. Trends Genet.

37:1012–1027. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jiang H and Bu L: Progress in the

treatment of lung adenocarcinoma by integrated traditional Chinese

and Western medicine. Front Med (Lausanne). 10:13233442024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen L, Xu YX, Wang YS, Ren YY, Chen YM,

Zheng C, Xie T, Jia YJ and Zhou JL: Integrative Chinese-Western

medicine strategy to overcome docetaxel resistance in prostate

cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 331:1182652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lin J, Sun L, Chen H, Chen W, Zhang Z, Cao

Y and Lin L: Chinese and Western integrative medicine for stage

IIIb-IVb non-small cell lung cancer: Design and rationale of a

multi-center, prospective registry (NSCLC-Chinese and Western

integrative medicine cohort). Integr Cancer Ther.

22:153473542311851092023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Komori T: The 2016 WHO classification of

tumours of the central nervous system: The major points of

revision. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 57:301–311. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wu W, Klockow JL, Zhang M, Lafortune F,

Chang E, Jin L, Wu Y and Daldrup-Link HE: Glioblastoma multiforme

(GBM): An overview of current therapies and mechanisms of

resistance. Pharmacol Res. 171:1057802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Koch M, Schulze J, Hansen U, Ashwodt T,

Keene DR, Brunken WJ, Burgeson RE, Bruckner P and Bruckner-Tuderman

L: A novel marker of tissue junctions, collagen XXII. J Biol Chem.

279:22514–22521. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Huang ML and Luo WL: Engrailed homeobox 1

transcriptional regulation of COL22A1 inhibits nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cell senescence through the G1/S phase arrest. J Cell Mol

Med. 26:5473–5485. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Misawa K, Kanazawa T, Imai A, Endo S,

Mochizuki D, Fukushima H, Misawa Y and Mineta H: Prognostic value

of type XXII and XXIV collagen mRNA expression in head and neck

cancer patients. Mol Clin Oncol. 2:285–291. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pan R, Pan F, Zeng Z, Lei S, Yang Y, Yang

Y, Hu C, Chen H and Tian X: A novel immune cell signature for

predicting osteosarcoma prognosis and guiding therapy. Front

Immunol. 13:10171202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lei Y, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu

J, Yu X and Shi S: Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer

research: Progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 14:912021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Papalexi E and Satija R: Single-cell RNA

sequencing to explore immune cell heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol.

18:35–45. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ofengeim D, Giagtzoglou N, Huh D, Zou C

and Yuan J: Single-Cell RNA sequencing: Unraveling the brain one

cell at a time. Trends Mol Med. 23:563–576. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Walker K and Padhiar M:

AACR-NCI-EORTC--21st international symposium. Molecular targets and

cancer therapeutics-Part 2. IDrugs. 13:10–12. 2010.

|

|

34

|

Devi KP, Malar DS, Nabavi SF, Sureda A,

Xiao J, Nabavi SM and Daglia M: Kaempferol and inflammation: From

chemistry to medicine. Pharmacol Res. 99:1–10. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yang RY, Lin S and Kuo G: Content and

distribution of flavonoids among 91 edible plant species. Asia Pac

J Clin Nutr. 17(Suppl 1): S275–S279. 2008.

|

|

36

|

Calderón-Montaño JM, Burgos-Morón E,

Pérez-Guerrero C and López-Lázaro M: A review on the dietary

flavonoid kaempferol. Mini Rev Med Chem. 11:298–344. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kim TW, Lee SY, Kim M, Cheon C and Ko SG:

Kaempferol induces autophagic cell death via IRE1-JNK-CHOP pathway

and inhibition of G9a in gastric cancer cells. Cell Death Dis.

9:8752018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang X, Yang Y, An Y and Fang G: The

mechanism of anticancer action and potential clinical use of

kaempferol in the treatment of breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother.

117:1090862019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tie F, Ding J, Hu N, Dong Q, Chen Z and

Wang H: Kaempferol and kaempferide attenuate oleic acid-induced

lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. Int J Mol

Sci. 22:88472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lin CW, Shen SC, Chien CC, Yang LY, Shia

LT and Chen YC: 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced

invasion/migration of glioblastoma cells through activating

PKCalpha/ERK/NF-kappaB-dependent MMP-9 expression. J Cell Physiol.

225:472–481. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Imran M, Salehi B, Sharifi-Rad J, Aslam

Gondal T, Saeed F, Imran A, Shahbaz M, Tsouh Fokou PV, Umair Arshad

M, Khan H, et al: Kaempferol: A key emphasis to its anticancer

potential. Molecules. 24:22772019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|