Introduction

Castleman's disease (CD), first described by

Castleman in 1954 (1), is commonly

encountered in the chest and neck, but is less common in the

abdomen and rare in the liver. Primary hepatic CD is very rare,

with <20 cases reported in the literature to date (2). Furthermore, description of computed

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

characteristics of hepatic CD is rarely found in the radiological

literature, particularly from diffusion-restricted on

diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and CD may be misdiagnosed as a

malignant lesion (3). Therefore, the

radiological diagnosis of hepatic CD remains difficult. We herein

describe a case of hepatic CD detected by CT and MRI, along with a

review of the previous cases reported in the literature, with the

aim to help improve our understanding and radiological diagnosis of

hepatic CD.

Case report

An asymptomatic 70-year-old woman underwent a

routine physical examination in a local hospital, during which a

focal lesion was identified in the right lobe of the liver via

ultrasound. The patient received no immediate treatment and was

referred for further evaluation to the First Affiliated Hospital of

Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Hangzhou, China). The findings

on physical examination and the results of the laboratory tests,

including complete blood count and basic metabolic panels, were

normal. Subsequently, the patient underwent CT (Somatom, Sensation

64; Siemens, Waltershausen, Germany) and MRI (3.0T Discovery 750;

GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) scans of the abdomen for further

evaluation and, finally, the focal lesion was surgically

resected.

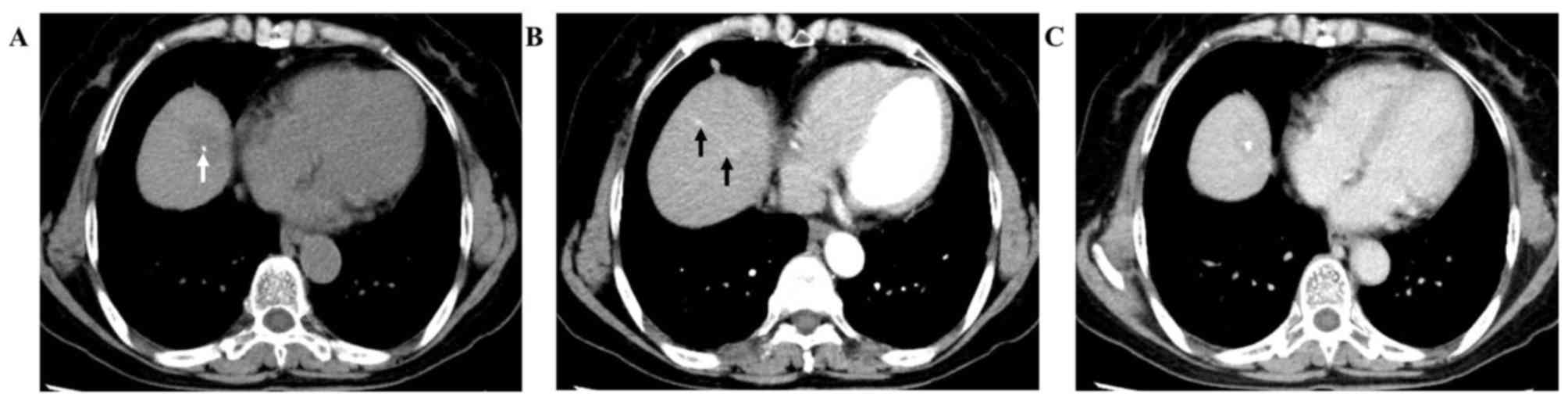

A non-enhanced abdominal CT was first conducted and

revealed well-defined nodular hypoattenuation with punctate

hyperattenuation (Fig. 1A, arrow)

within a lesion in the eighth segment of the liver. On enhanced CT

imaging, the lesion exhibited nodular enhancement (2.3×1.9 cm), and

a strip-like enhanced area was found to extend from the nodule in

the arterial phase 30 sec after injection of iodine contrast agent

(Fig. 1B, arrows), with persistent

enhancement in the portal venous phase 65 sec after injection of

iodine contrast agent (Fig. 1C).

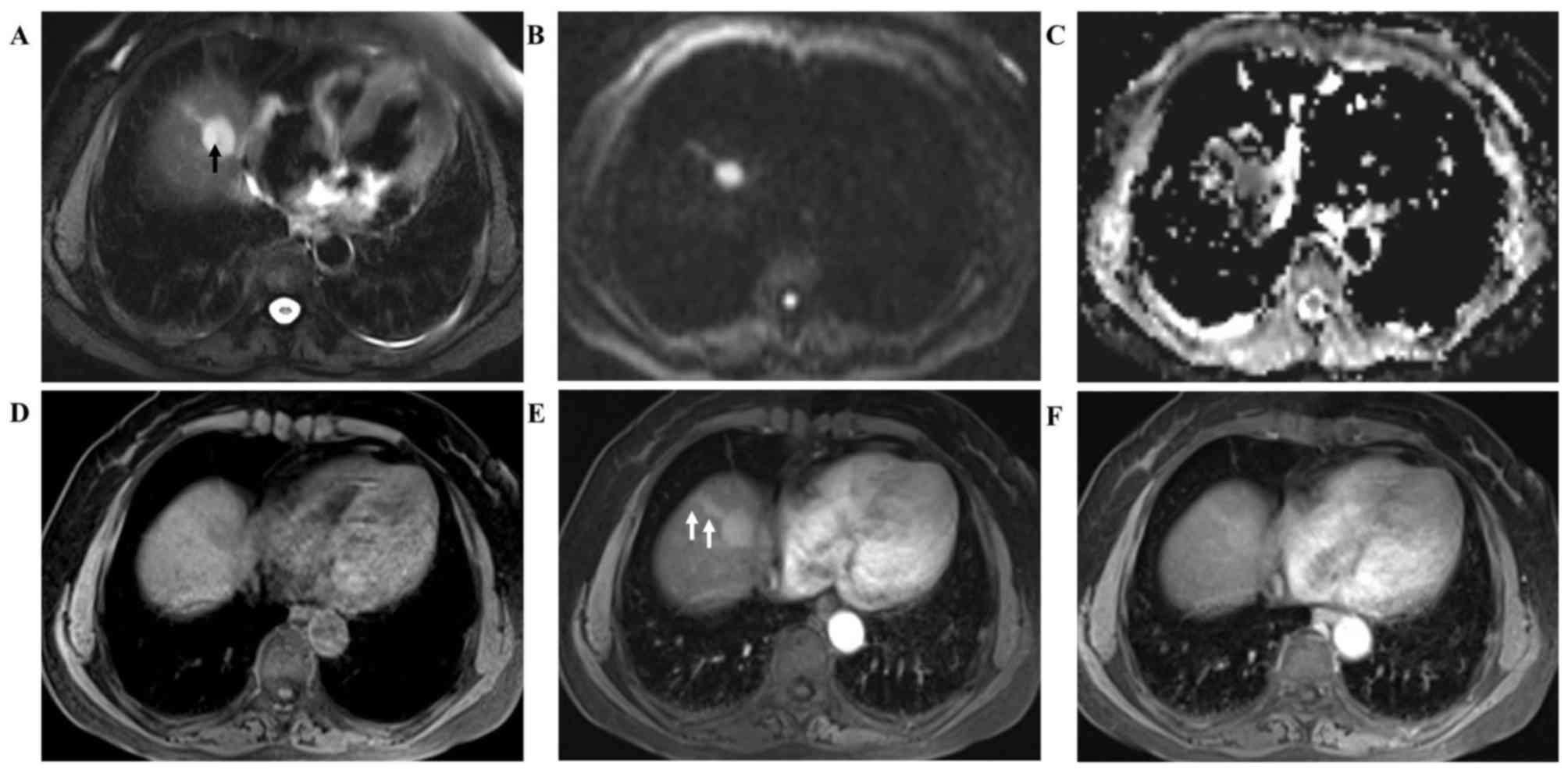

A follow-up MRI was performed 10 days later and

revealed a well-defined nodule (2.6×2.0 cm) with an extended strip

in the eighth segment of the liver on T2-weighted imaging. Punctate

hypointensity was also observed in the center of the nodule

(Fig. 2A, arrow). Both the nodule

and the strip displayed hyperintensity on DWI (b=800

sec/mm2, Fig. 2B) with a

low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value

(0.622×10−3 and 0.693×10−3

mm2/sec, respectively; Fig.

2C). Compared with non-enhanced T1-weighted MR images (Fig. 2D), post-contrast MRI revealed

significant enhancement of the nodule and the strip in the arterial

phase 30 sec after gadolinium injection (Fig. 2E, arrows), and persistent enhancement

in the parenchymal phase 120 sec after gadolinium injection

(Fig. 2F).

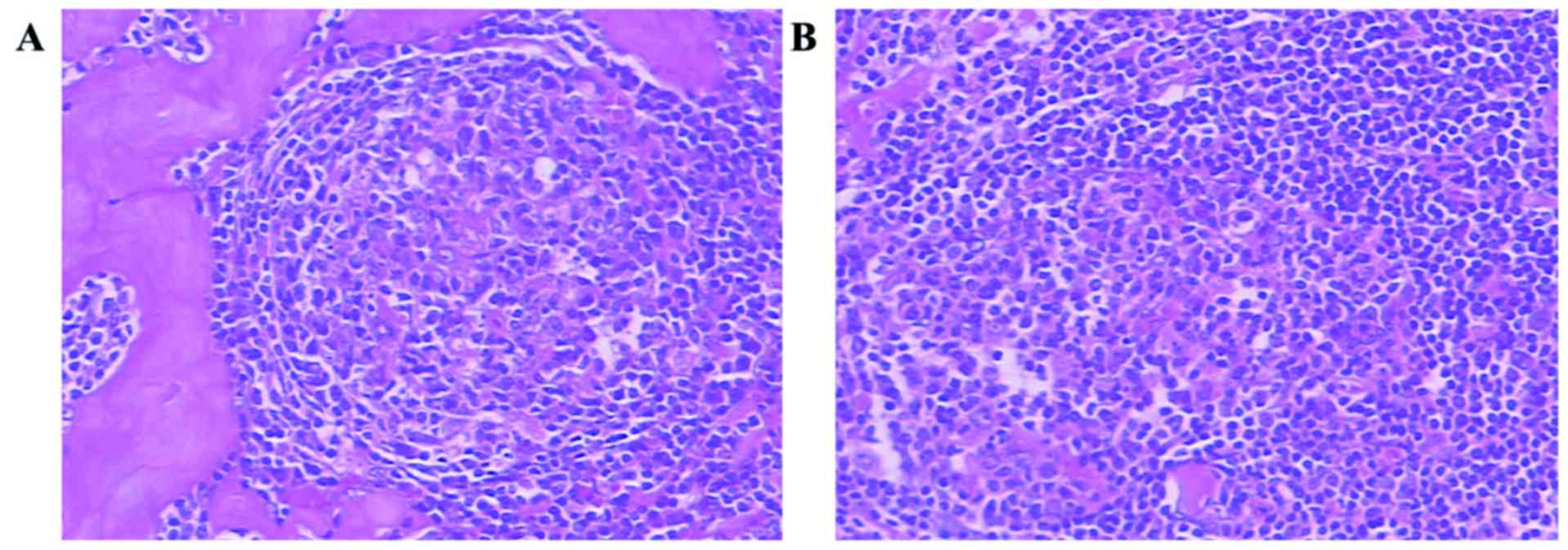

The lesion in the right liver was resected by

surgical laparoscopy under general anesthesia. Postoperative

pathological examination demonstrated that the pathological

components of the nodular mass were lymphocytes and hyalinized

vessels (Fig. 3A), with the

strip-like area being composed mainly of lymphocytes (Fig. 3B).

Postoperative treatment of the patient was

administration with Saimeijie (an atypical β-lactams antibiotic,

2.0 g bid) and Ornidazole (0.5 g bid) to prevent infection, and

support treatment with hemostasis and rehydration within 2 weeks.

Postoperative recovery was good and there has been no recurrence on

the last follow-up before the present study was submitted.

Discussion

Castleman's disease (CD) (4) may be histologically divided into

hyaline vascular (HV), plasma cell (PC) and mixed variants. The HV

variant (5), which is composed of

follicles and follicular lymph tissue, is commonly found in women

aged 30–40 years and accounts for 90% of diagnosed cases.

Phenotypically, this variant is defined by the presence of abundant

hyperplastic hyaline capillaries between follicles and lymph

sinuses. Furthermore, small lymphocytes in the mantle zone are

arranged in concentric rings around the germinal center. The

prognosis of the HV variant is mostly favorable following surgical

resection. The PC variant (6) is a

systemic disease that is more common among patients aged 50–60

years, and accounts for ~10% of diagnosed cases. This variant is

defined by enlargement of follicular cells and an abundance of

mature plasma cells, but a lower degree of angiogenesis. Treatment

is administered systemically using hormone or immunosuppressive

agents, but the prognosis of the PC variant is poor. Two clinical

subtypes are classified as unicentric CD (UCD) and multicentric CD

(MCD) (7–9). UCD occurs most frequently as a focal

lesion of the HV variant that is not associated with obvious

clinical symptoms and is often incidentally found during routine

physical examination. MCD is a systemic disease, with the majority

of the cases being of the PC variant, accompanied by systemic

symptoms including fatigue, fever, night sweats, weight loss, joint

pain and hepatosplenomegaly.

The imaging findings of UCD (10) often present as a single, well-defined

soft tissue lesion, with rare cystic degeneration and focal

necrosis. This finding may be associated with substantial

angiogenesis and development of an extensive collateral

circulation, so the lymph follicle tissue is not prone to necrosis

(11). Non-enhanced CT images

revealed homogeneous mild hypoattenuation within the lesion.

Non-enhanced MR T1WI revealed a slightly hyperintensity compared

with muscle. Furthermore, T2WI and DWI displayed high signals,

suggesting diffusion restriction and supporting abundant cell

proliferation (12).

Contrast-enhanced CT/MRI of CD lesions often displays mild to

moderate enhancement during the arterial phase, and persistent

enhancement during the venous phase (13). This finding may be associated with

the small arterial lumen and the subsequent reduction in blood

velocity. Polymorphic calcification is commonly found in the

lesions (14), which may be

attributed to capillary proliferation with wall thickening and

accompanied by glassy degeneration, fibrotic degeneration and the

formation of calcareous deposits along the vessel wall. Imaging

findings in MCD (15) include

multiple enlarged lymph nodes with homogeneous density and mild to

moderate enhancement on a contrast-enhanced scan, which

pathologically reflects enlarged follicles and follicular plasma

cell infiltration. In MCD is of the HV variant, the degree of

enhancement is similar to that of UCD.

The reported imaging findings of hepatic CD

(16–23) (Table

I) are commonly consistent with UCD. These findings and the

calcification of the lesion may be helpful for radiological

diagnosis of CD in the liver. Moreover, we observed that the

signal, density, and pathological components of the strip-like area

were consistent with those of the nodule. To the best of our

knowledge, this finding has not been previously reported in the

literature on hepatic CD to date. We hypothesized that the

strip-like area may be attributed to lymphoid tissue, and

lymphoproliferative disease may develop anywhere where lymphoid

tissue is present (20). This

strip-like area extending from the nodule may help with the

differential diagnosis of hepatic CD from other diseases. However,

pathological examination is required for a definitive

diagnosis.

| Table I.Imaging characteristics of hepatic

Castleman's disease. |

Table I.

Imaging characteristics of hepatic

Castleman's disease.

|

|

|

|

| Imaging

characteristics |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Authors | Sex/age (years) | Symptoms | Size (cm) | Margins | Ultrasound | CT/MRI | Pathology | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Rahmouni et

al | Female/48 | Abdominal pain | 5 | Well-defined | Hypoechoic | Hypervascular,

calcifications | HV | (16) |

|

| Male/28 | Asymptomatic | 3 | Lobulated | Hypoechoic | Hypervascular | HV |

|

| Cirillo et

al | Female/43 | Abdominal pain | 13 | Well-defined | NA | Nonvascular,

calcifications | HV | (17) |

| Uzunlar et

al | Female/56 | Vague abdominal

pain | 3.5 | Well-defined | Hypoechoic | Hypervascular | HV | (18) |

| Karami et

al | Female/5 | Abdominal pain | 3.7 | Lobulated | Solid mass | Hypervascular | HV | (19) |

| Jang et

al | Female/40 | Abdominal pain, fever

and chills | 2.2 | Well-defined | NA | Hypervascular | HV | (20) |

| Miyoshi et

al | Female/70 | Asymptomatic | 1.5 | Well-demarcated | Hypoechoic | Hypovascular | HV | (21) |

| Dong et

al | Female/57 | Asymptomatic | 3.3 | Well-defined | NA | Hypervascular,

diffusion restricted | HV | (22) |

| Maundura et

al | Female/64 | Asymptomatic | 1.4 | Well-defined | Hypoechoic | Hypervascular,

diffusion restricted | HV | (23) |

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This article does not contain any studies with human

participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to this paper and approved

the final version. LK wrote the case report. ZCL offered the

assistance for the pathologic diagnosis of this case. XMS and LK

revised and edited the final version.

Consent for publication

The patient and/or her family consented to the

publication of the case details and associated images.

References

|

1

|

Castleman B and Towne VW: Case records of

the massachusetts general hospital; weekly clinicopathological

exercises; founded by Richard C. Cabot. N Engl J Med. 251:396–400.

1954.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Talat N, Belgaumkar AP and Schulte KM:

Surgery in Castleman's disease: A systematic review of 404

published cases. Ann Surg. 255:677–684. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Malayeri AA, El Khouli RH, Zaheer A,

Jacobs MA, Corona-Villalobos CP, Kamel IR and Macura KJ: Principles

and applications of diffusion-weighted imaging in cancer detection,

staging, and treatment follow-up. Radiographics. 31:1773–1791.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Soumerai JD, Sohani AR and Abramson JS:

Diagnosis and management of Castleman disease. Cancer Control.

21:266–278. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Keller AR, Hochholzer L and Castleman B:

Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node

hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer.

29:670–683. 1972. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ferry JA and Harris NL: Atlas of lymphoid

hyperplasia and lymphoma. WB. Saunders Company; pp. 1–1042.

1997

|

|

7

|

Gaba AR, Stein RS, Sweet DL and Variakojis

D: Multicentric giant lymph node hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol.

69:86–90. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Casper C: The aetiology and management of

Castleman disease at 50 years: Translating pathophysiology to

patient care. Br J Haematol. 129:3–17. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

van Rhee F, Stone K, Szmania S, Barlogie B

and Singh Z: Castleman disease in the 21st century: An update on

diagnosis, assessment, and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol.

8:486–498. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhou LP, Zhang B, Peng WJ, Yang WT, Guan

YB and Zhou KR: Imaging findings of Castleman disease of the

abdomen and pelvis. Abdom Imaging. 33:482–488. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

McAdams HP, Rosado-de-Christenson M,

Fishback NF and Templeton PA: Castleman disease of the thorax:

Radiologic features with clinical and histopathologic correlation.

Radiology. 209:221–228. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

White NS, McDonald C, Farid N, Kuperman J,

Karow D, Schenker-Ahmed NM, Bartsch H, Rakow-Penner R, Holland D,

Shabaik A, et al: Diffusion-weighted imaging in cancer: Physical

foundation and application of restriction spectrum imaging. Cancer

Res. 74:4638–4652. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jiang XH, Song HM, Liu QY, Cao Y, Li GH

and Zhang WD: Castleman disease of the neck: CT and MR imaging

findings. Eur J Radiol. 83:2041–2050. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bonekamp D, Horton KM, Hruban RH and

Fishman EK: Castleman disease: The great mimic. Radiographics.

31:1793–1807. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Johkoh T, Müller NL, Ichikado K, Nishimoto

N, Yoshizaki K, Honda O, Tomiyama N, Naitoh H, Nakamura H and

Yamamoto S: Intrathoracic multicentric Castleman disease: CT

findings in 12 patients. Radiology. 209:477–481. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rahmouni A, Golli M, Mathieu D, Anglade

MC, Charlotte F and Vasile N: Castleman disease mimicking liver

tumor: CT and MR features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 16:699–703.

1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cirillo RL Jr, Vitellas KM, Deyoung BR and

Bennett WF: Castleman disease mimicking a hepatic neoplasm. Clin

Imaging. 22:124–129. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Uzunlar AK, Ozateş M, Yaldiz M,

Büyükbayram H and Ozaydin M: Castleman's disease in the porta

hepatis. Eur Radiol. 10:1913–1915. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Karami H, Sahebpour AA, Ghasemi M, Karami

H, Dabirian M, Vahidshahi K, Masiha F and Shahmohammadi S: Hyaline

vascular-type Castleman's disease in the hilum of liver: A case

report. Cases J. 3:742010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jang SY, Kim BH, Kim JH, Ha SH, Hwang JA,

Yeon JW, Kim KH and Paik SY: A case of Castleman's disease

mimicking a hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and review of

literature. Korean J Gastroenterol. 59:53–57. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Miyoshi H, Mimura S, Nomura T, Tani J,

Morishita A, Kobara H, Mori H, Yoneyama H, Deguchi A, Himoto T, et

al: A rare case of hyaline-type Castleman disease in the liver.

World J Hepatol. 5:404–408. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dong A, Dong H and Zuo C: Castleman

disease of the porta hepatis mimicking exophytic hepatocellular

carcinoma on CT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 39:e69–e72.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Maundura M, Hayward G, McKee C and Koea

JB: Primary Castleman's disease of the liver. J Gastrointest Surg.

21:417–419. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|