Introduction

Primary brain tumors comprise a heterogeneous group

of neoplasms, with different outcomes, with patients requiring

different management strategies. These tumors can range from

pilocytic astrocytomas, a very uncommon, non-invasive curable

tumor, to glioblastoma (GBM), which is associated with more

invasive and aggressive behaviors (1).

GBM is the most common primary brain tumor among

adults. It is associated with a median survival rate of 16-21

months and a 10-year survival of <1% (1-5).

GBM accounts for 45.6% of all primary brain malignancies. The

incidence rate of GBM is 3.19 among 100,000 individuals from

different age groups with a median age of 64 years; however, it can

occur at any age (6).

In general, GBM is associated with a very poor

prognosis. However, several parameters associated with improved

outcomes include an age <50 years, a non-eloquent tumor

location, a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score ≥70 and the

maximal extent of tumor resection (7,8).

The treatment of patients with GBM includes maximal

surgical resection with adjuvant radiotherapy. The inclusion of

nitrosoureas has exhibited benefits in addition to the standard

treatment; however, this has only been demonstrated in multivariant

and randomized comparison studies (7,9). The use

of adjuvant temozolomide was previously investigated in a

randomized phase III, EORTCNCIC trials along with standard surgical

resection and radiotherapy; its use was found to be associated with

an improved overall survival rate of 14.6 compared to 12.1 months

with standard treatment with radiotherapy (10,11).

Temozolomide was approved in 2005, and since then, it has been the

standard chemotherapeutic treatment for GBM for six 6 cycles

following radiotherapy (12).

GBMs have a high recurrence rate even in cases in

which they have been discovered at an early stage and treated

completely. The median recurrence time is 9.5 months, with an

overall survival rate of 30 months (13). The treatment of recurrent or

progressive GBMs can include supportive care, as decided by the

treating physician. On the other hand, tumor-specific

multidisciplinary boards are another approach for treating patients

with GBM; the use of these has been shown to be associated with a

12-month survival rate of 32.5% compared to 11.3% in the group with

supportive treatment (14).

A previous meta-analysis investigated palliative

care intervention in adults with terminal illnesses and diseases,

including oncology. The quality of life (QOL) of patients was

assessed in 24 studies, including 4,576 patients; 12 (50%) studies

evaluated the association between QOL and palliative care

intervention and reported a statistically significant improvement

in QOL and symptoms burden (15).

When assessing the end-of-life in a patient with

GBM, a decreased level of consciousness, a change in mental status,

fever, seizures and dysphagia have been shown to have the most

marked clinical burden as the disease progresses. Moreover, this

provides the basis for care in these terminal care cases to include

anticonvulsants, steroids and gastric protection, such as

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (16,17).

Other modalities of palliative care are short-course

radiotherapy, which has been shown to be beneficial in patients

with a KPS score <50, along with the optimal supportive and

palliative care, including the use of corticosteroids (18). The use of mifepristone, a

progesterone receptor antagonist, has also been suggested for

palliative care therapy in patients with advanced-stage brain

tumors, including GBM, as it exhibits good penetration through the

blood-brain barrier (19).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)

Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend the addition of palliative

care in patients with advanced-stage cancer (20). Specifically, patients with GBM suffer

from progressive neurological diseases that affect their QOL along

with their decision-making capacity; of note, ~50% of patients with

primary malignant brain tumors have compromised medical

decision-making at the time of diagnosis due to cognitive

impairment, behavioral changes and poor communication abilities

(21). Therefore, advanced care

planning (ACP) has evolved to facilitate the communication of goals

and preferences regarding future medical care, and it is considered

crucial in patients with GBM. It not only includes the treatment

design and a proxy decision maker, but also extends to involve open

communications between the patient, proxy, decision-makers and care

providers to discuss the preferences for future medical care,

including palliative care options (22).

ACP can be utilized to improve the quality of

communications between patients and healthcare providers and may

reduce unwanted interventions and admissions. In addition, it

enhances the use of palliative care, which increases the

satisfaction and QOL of both patients and relatives (22,23).

Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically

review and analyze the available literature on patients with GBM

receiving palliative care.

Data and methods

Literature search strategy

The present study aimed to systematically review and

analyze the available literature on patients with GBM receiving

palliative care. The PubMed, Scopus, Wiley and Web of Science

databases were searched by three authors (AMAG, SAB and AMAA) to

gather the available literature using the following key words:

‘Glioblastoma’, ‘GBM’, ‘Grade 4 glioma’, ‘Palliative care’,

‘Conservative’, ‘Non-surgical’, ‘Comfort care’, ‘Management’,

‘Palliative Radiotherapy’, ‘Palliative Chemotherapy’ and ‘End of

life’.

Study selection, inclusion and

exclusion criteria

Studies were selected using a systematic review

following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. All articles relevant to the

topic of the review were included, covering patients of all age

groups, and all types of palliative care used, in all settings and

there was no time limit; however, articles that were not published

in the English language were excluded from the systematic

review.

Data extraction and analysis

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria,

AMAG, SAB and AMAA screened the titles and abstracts of possible

eligible studies. Moreover, the three authors examined the key

features from the eligible studies, extracting the aims, treatments

and palliative care applied, as well as the outcomes, place of

mortality (either at a health institute or at home), and the

recommendation from the authors of that study. In addition, the

three authors examined the year of publication, and the country

where the study was conducted.

Results

Study selection, including and

exclusion criteria

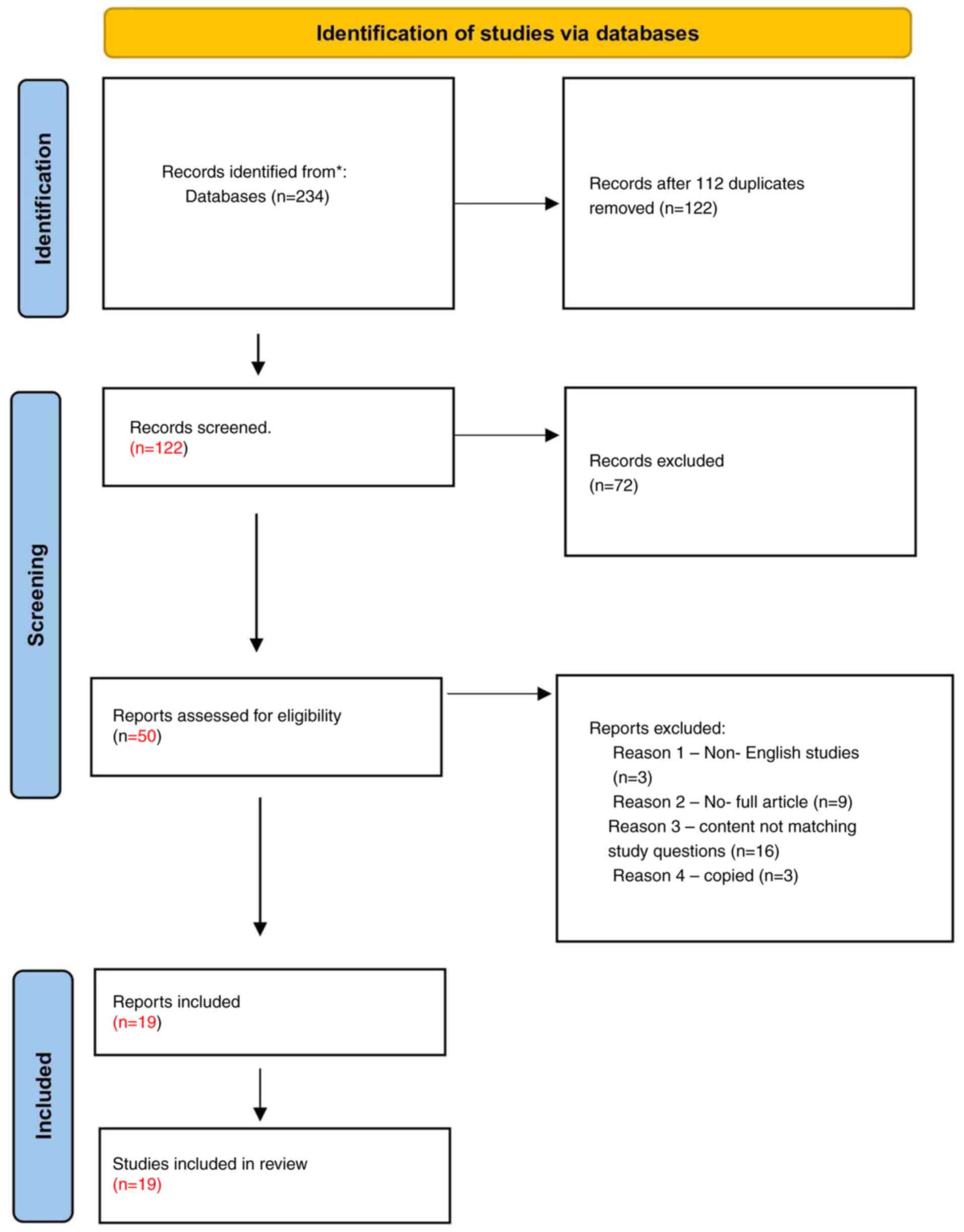

In the present systematic review, the three authors

were allocated to investigate four databases, obtaining a total of

234 studies that matched the objectives of the review. Moreover,

112 studies were excluded as they were duplicates. After reviewing

these articles, 72 studies were removed as they did not match the

aim of the review. After applying the inclusion and exclusion

criteria, a total of 50 articles were included; however, of these,

three articles were excluded as they were non-English studies, the

full article could not be accessed in nine articles and 16 articles

were not relevant to the study question. In addition, three studies

were identified as copies or duplicates, having been retrieved from

the searches conducted independently by the three different authors

and were removed. Eventually, a total of 19 articles were included

in the present systematic review (Fig.

1).

Quality assessment and geographical

distribution

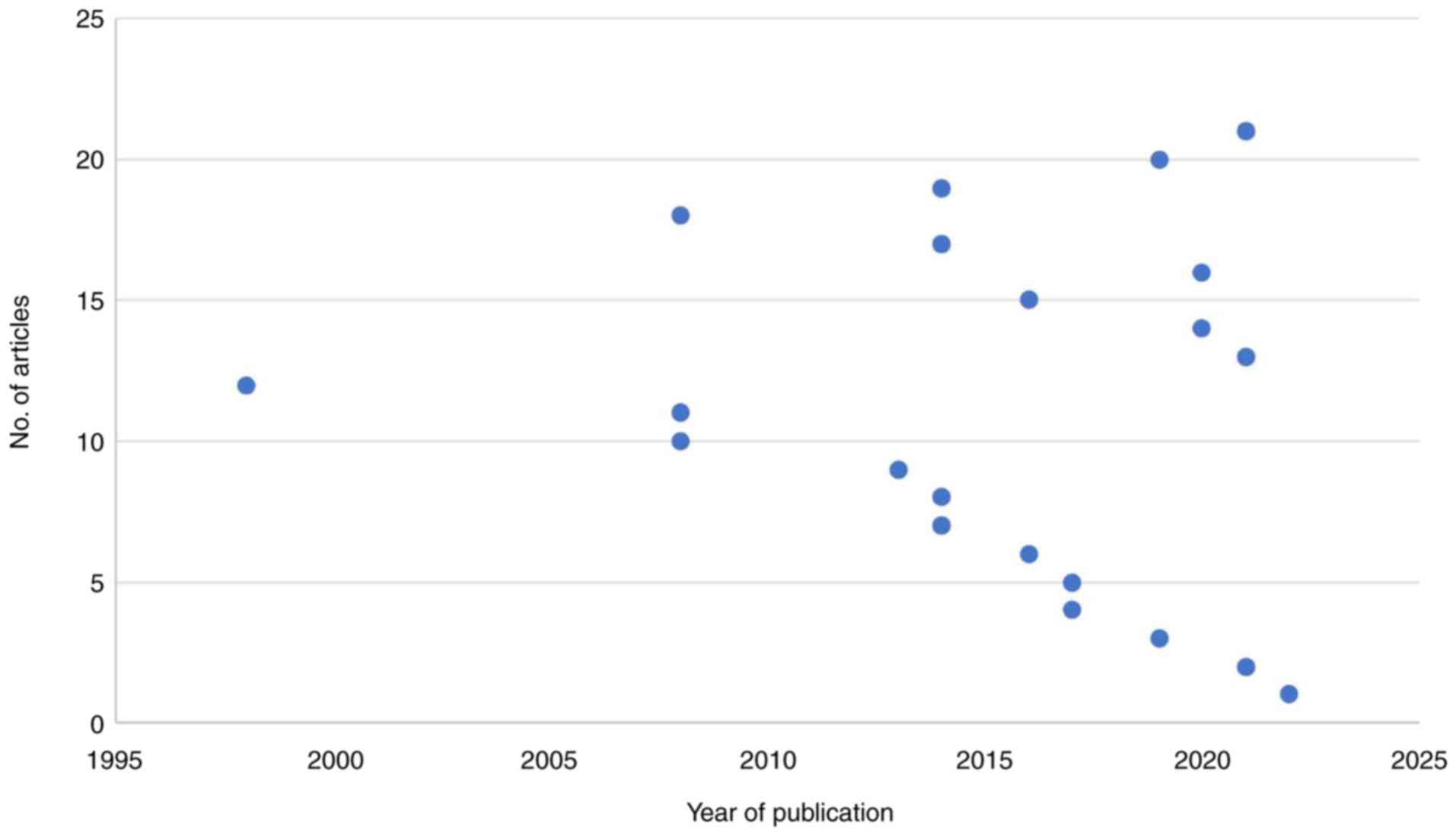

In the present systematic review, 19 articles were

included, with publication years ranging between 1998 and 2022,

with a total of 7,392 patients (Fig.

2). Of note, two of these articles were case reports (19,24). The

majority of the included articles were retrospective analyses (10

articles out of 19 articles) (14,18,25-32).

A total of four articles were prospective studies (16,33-35),

two articles were systematic reviews (17,36) and

one article was a randomized clinical trial (37) (Table

I).

| Table IQuality assessment of the included

studies. |

Table I

Quality assessment of the included

studies.

| Article no. | Authors, year of

publication | Type of study | Level of

evidence | Sample | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 1 | Senderovich et

al, 2022 | Case report | 4 | n=1,

phenobarbital | (24) |

| 2 | Witteler et

al, 2021 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=31,

radiotherapy | (18) |

| 3 | Wu et al,

2021 | Systematic

review | 1a | NA | (36) |

| 4 | Harrison et

al, 2021 | Retrospective

cohort study | 3b | n=132, NA | (25) |

| 5 | Lin et al,

2020 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=50, medications:

Steroids, anti-epileptic drugs, Benzodiazepines….. Allied health

involvement: Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work,

speech pathology, pastoral care | (26) |

| 6 | Kim et al,

2020 | Prospective

study | 2b | n=294, NA | (35) |

| 7 | Golla et al,

2020 | Randomized clinical

trial | 1b | n=214,

Interventional group [proactive early integration of palliative

care (EPIC) on a monthly basis], control group (receiving treatment

according to international standards and additional, regular

assessment of quality of life) | (37) |

| 8 | Glynn et al,

2019 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=104 radiotherapy

(hypofractionated palliative radiotherapy) | (27) |

| 9 | Stavrinou e et

al, 2018 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=259, glioblastoma

was treated with maximal safe resection followed by adjuvant

radiotherapy + post-operative chemotherapy (6 cycles of

temozolomide), then palliative care with supportive treatment | (14) |

| 10 | Hemminger et

al, 2017 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=117,

chemotherapy | (28) |

| 11 | Kuchinad et

al, 2017 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=100,

chemotherapy | (29) |

| 12 | Thier et al,

2016 | Prospective

study | 2b | n=57, non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs, anticonvulsants and steroids | (16) |

| 13 | Check et al,

2014 | Case report | 4 | n=1,

mifepristone | (19) |

| 14 | Sundararajan et

al, 2014 | Retrospective

cohort study | 3b | n=678, palliative

care consult, palliative care bed, social work, physiotherapy,

occupational therapy, speech pathology, psychology, rehabilitation

bed | (30) |

| 15 | Pompili et

al, 2014 | Prospective

study | 2b | n=197, 122 of which

with GBM, sedation with midazolam, intramuscular phenobarbital for

seizure, hydration, tube feeding | (34) |

| 16 | Walbert and Khan,

2014 | Systematic

literature review | 1a | NA, interventions

include hydration, urinary catheterization, steroids, antiepileptic

drugs, oxygen insufflation, tube feeding and palliative

sedation | (17) |

| 17 | Ziobro et

al, 2008 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=5,124 palliative

treatment with temozolomide | (31) |

| 18 | Oberndorfer et

al, 2008 | Retrospective

analysis | 3b | n=29, the majority

of patients were on antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), steroids, and

analgesics. | (32) |

| 19 | Reimer et

al, 1998 | Prospective

study | 2b | n=4, laser-induced

thermotherapy | (33) |

The present systematic review included articles

conducted in a variety of countries (Table II); the majority of articles were

from the USA (17,19,25,28,29,35,36), and

the remaining articles were from Germany (14,18,33,37),

Austria (16,32), Australia (26,30),

Poland (31), Italy (34), Ireland (27), and one study published by authors

from different nationalities (24).

| Table IIGeographical distribution of

the included studies. |

Table II

Geographical distribution of

the included studies.

| Article no. | Authors: Study

title | Country | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 1 | Senderovich et

al: Evading Seizures: Phenobarbital Reintroduced as a

Multifunctional Approach to End-of-Life Care. | Published online

(Author nationalities: Canada, Ireland, Anguilla) | (24) |

| 2 | Witteler et

al: Palliative radiotherapy of primary glioblastoma. | Germany | (18) |

| 3 | Stavrinou et

al: Survival effects of a strategy favoring second-line

multimodal treatment compared to supportive care in glioblastoma

patients at first progression. | Germany | (14) |

| 4 | Hemminger et

al: Palliative and end-of-life care in glioblastoma: Defining

and measuring opportunities to improve care. | USA | (28) |

| 5 | Kuchinad et

al: End of life care for glioblastoma patients at a large

academic cancer center. | USA | (29) |

| 6 | Thier et al:

The Last 10 Days of Patients With Glioblastoma: Assessment of

Clinical Signs and Symptoms as well as Treatment. | Austria | (16) |

| 7 | Check et al:

Evidence that mifepristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, can

cross the blood brain barrier and provide palliative benefits for

glioblastoma multiforme grade IV. | USA | (19) |

| 8 | Sundararajan et

al: Mapping the patterns of care, the receipt of palliative

care and the site of death for patients with malignant glioma. | Australia | (30) |

| 9 | Lin et al:

Inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with

glioblastoma in a tertiary hospital. | Australia | (26) |

| 10 | Ziobro et

al: Effects of palliative treatment with temozolomide in

patients with high-grade gliomas. | Poland | (31) |

| 11 | Oberndorfer et

al: The end-of-life hospital setting in patients with

glioblastoma. | Austria | (32) |

| 12 | Reimer et

al: MR-monitored LITT as a palliative concept in patients with

high grade gliomas: Preliminary clinical experience. | Germany | (33) |

| 13 | Wu et al:

Palliative Care Service Utilization and Advance Care Planning for

Adult Glioblastoma Patients: A Systematic Review. | USA | (36) |

| 14 | Kim et al:

Utilizing a Palliative Care Screening Tool in Patients With

Glioblastoma. | USA | (35) |

| 15 | Golla et al:

Effect of early palliative care for patients with glioblastoma

(EPCOG): a randomised phase III clinical trial protocol. | Germany | (37) |

| 16 | Pompili et

al: Home palliative care and end of life issues in glioblastoma

multiforme: results and comments from a homogeneous cohort of

patients. | Italy | (34) |

| 17 | Walbert and Khan:

End-of-life symptoms and care in patients with primary malignant

brain tumors: A systematic literature review. | USA | (17) |

| 18 | Glynn et al:

Glioblastoma Multiforme in the over 70's: ‘To treat or not to treat

with radiotherapy?’. | Ireland | (27) |

| 19 | Harrison et

al: Aggressiveness of care at end of life in patients with

high-grade glioma. | USA | (25) |

Palliative care

From each included study, different aspects were

evaluated, including the primary treatment administered if

applicable, the palliative care treatment introduced, whether the

study examined inpatients, outpatients, or both, and the outcomes

derived from each intervention. The median survival rate was

evaluated, and the recommendation was provided by the authors. In

the included studies, different palliative care therapies were used

as adjuvants with the primary treatment, targeting various aspects

of palliative care (Table

III).

| Table IIISummary of the included studies. |

Table III

Summary of the included studies.

| First author | Aim of study | Total no. of

patients | GBM diagnosis

duration | Patients KPS score

or ECOG score (if mentioned) | Treatment of the

GBM (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, no treatment or others) | Palliative care

treatment type | PC inpatient vs.

outpatient | Palliative care

treatment | Study outcomes | Median survival

rate of patients |

Recommendations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pompili | Identify home

palliative care and end of life issues in GBM | 197: Brain tumors,

122 of them GBM | NM | KPS score

>70 | NM | Supportive

treatment | Outpatient | Sedation with

midazolam + Intramuscular phenobarbital for seizure + hydration +

tube feeding | 1-End of life

palliative sedation with midazolam was necessary in 11% of cases to

obtain good control of symptoms such as uncontrolled delirium,

agitation, death rattle, or refractory seizures. 2-Intramuscular

phenobarbital is the authors' drug of choice for the severe

seizures that occurred in 30% of cases. | 13.34 months | 1-Future clinical

research strategies should include new models of care for patients

with brain tumors, with special attention given to palliative home

care models. | (34) |

| Oberndorfer | To evaluate the

end-of-life phase in a hospital setting in patients with GBM. | 29 | NM | Mean KPS phase 1=

70%/Phase 2= 50%/Phase 3= 20% | Surgery +

radiotherapy + subsequent chemotherapy/7-Surgery only (n=4), or

biopsy (n=3) | Symptoms drug +

physiotherapy + occupational therapy + logopedia + psychologic

assessment-directed to mobilize the patient and to strengthen his

remaining function, was only marginal in all three phases |

Inpatient/outpatient | Antiepileptic drugs

(AED) + steroids + analgesics | 1-End of life in

patients with glioblastoma has several periods with different

clinical aspects with respect to symptoms and treatment/2-Drug

treatment generally showed a continuous increase from phase 1 to 3

except steroids, which declined in phase 3. | The last 10 weeks

before death were divided into three periods. Phase 1, from 10 to 6

weeks before death; phase 2, 6 to 2 weeks before death; and phase

3, the last 2 weeks before death | 1-In Phase 3-All

medication should be promptly available and possibly given by a

nonoral route because dysphagia is present in the majority of

patients. 2-Practice of sedation in terminal ill patients has a

wide divergence among palliative care specialists and no clear

guidelines are available. 3-The requirement of further clinical

research to develop evidence-based guidelines. | (32) |

| Kuchinad | Retrospectively

analyze end-of-life care for GBM patients at academic center and

compare utilization of these services to national quality of care

guide, lines, Identifying opportunities to improve end-of-life

care. | 100 | NM | NM | Chemotherapy | NM |

Inpatient/outpatient | chemotherapy | 1-Documentation of

palliative care and end-of-life measures could improve quality of

care for GBM patients, especially in the use of ADs, symptom,

spiritual, and psychosocial assessments, with earlier use of

hospice to prevent end-of-life hospitalizations. 2-Hospice referral

and enrollment at Johns Hopkins exceeded national standards while

documentation of advance directives, and psychosocial assessments

demonstrated room for improvement. | 22 days | 1-More research is

needed to further define appropriate symptom management and

end-of-life care for this population. 2-Collaboration amongst

providers including neuro-oncologists, medical oncologists,

radiation oncologists, neuro-surgeons, social workers, chaplains

and other members of the care team can help optimize utilization of

palliative care measures at the end-of-life and identify and

establish necessary palliative care measures specific to the GBM

population. | (29) |

| Walbert | Review the

literature on end-of-life symptoms and end-of-life care of adult

patients with high-grade glioma (HGG). | NA | NM | NM | NM | Palliative care

interventions | Inpatients =3

studies/outpatients =2 studies/both =2 studies | Hydration + urinary

catheterization+ steroids + antiepileptic drugs + oxygen

insufflation + tube feeding + palliative sedation | 1-Patients with HGG

have a significant symptom load that worsens markedly at the end of

their lives (Poor communication, speech impairments, and cognitive

decline are common at the end-of-life period). | NM | 1-More prospective

studies are needed to better understand the end-of-life phase of

brain tumor patients. 2-Interventions should be evaluated to reduce

symptom burden and improve quality of life for patients and carers

without compromising the hope paradigm. | (17) |

| Reimer | Evaluate the

clinical utility of laser-induced thermotherapy (LITT] as a

palliative treatment for patients with high-grade glioma | 4 | NM | NM | Surgery +

radiotherapy | Laser-induced

thermotherapy | Inpatient | Laser-induced

thermotherapy | 1-Interventional

MRI-controlled LITT offers a number of potential treatment

benefits/2-MRI provides excellent topographic accuracy because of

its capability for soft tissue contrast, high spatial resolution,

and functional aspects. | NM | 1-The results have

yet to be verified in a larger clinical trial and then to be

compared with those of various other minimally invasive techniques.

2-Radiofrequency ablation, focused ultrasound, or cryosurgery are

alternative methods for tissue coagulation/ablation and have been

described for the ablation of brain tumors. | (33) |

| Lin | Examining the

symptoms, reasons for referral and outcomes of patients with GBM

referred to inpatient palliative care service. | 50 | The median time

from diagnosis of GBM to the palliative care consultation service

referral was 111 days (range 3-1,677). | NM |

94%-Surgery/54%-Radiotherapy/48%-chemotherapy | NM | Inpatient | Medication -

Steroids + Anti-epileptic drugs + Benzodiazepines/Allied health

involvement-Physiotherapy + Occupational therapy + Social work +

Speech pathology + Pastoral care | 1-Early palliative

care review of cancer patients can result in significant

improvements in pain, somnolence, and symptom distress scores as

well as overall well-being/2-The improvements were observed within

the first few days of consultation/3-Allied health services,

rehabilitation and psychosocial support are crucial components of

patient management. | The median time

from referral to date of death was 33 days (range 0-256), The

median length of inpatient stay was 9 days (range 2-35). The median

time from diagnosis of GBM to the palliative care consultation

service referral was 111 days (range 3-1677). | 1-Allied health

services, rehabilitation and psychosocial support are crucial

components of patient management | (26) |

| Check | Determine if

mifepristone could provide palliative benefits to patient with

end-stage stage IV glioblastoma multiforme | 1 | NM | NM | radiation +

chemotherapy | progesterone

receptor antagonist | NM |

mifepristone | 1-mifepristone

cross the blood-brain barrier and could be considered for

palliative therapy of other patients with chemotherapy-resistant

brain cancer/Within two weeks of taking mifepristone, patient

became more alert and able to carry-out intelligent. | NM | 1-Mifepristone does

cross the blood-brain barrier and could be considered for

palliative therapy of other patients with chemotherapy-resistant

brain cancer. Further studies are required to determine if the

35-kDa isoform of PIBF described by Lachman et al. in the cytoplasm

of cancer cells is identical to the 34-kDa form that rises. | (19) |

| Hemminger | Evaluate adherence

to 5 palliative care quality measures and explore associations with

patient outcomes in GBM | 117 | Diagnosis between

January 1, 2010 and May 1, 2015 | NM | Chemotherapy | Hospice care | Inpatient=

31/outpatient= 12 | NM | Early PC help with:

1-Reduce symptom burden. 2-Decrease rates of depression in patients

and caregivers. 3-Reduce costs of care. 4-Minimize hospitalizations

and in-hospital deaths. 5-Decrease aggressive end-of-life care.

6-Improve a patient's survival./but the study results are

consistent with the literature in illustrating that early

involvement of palliative care services is rare in

neuro-oncology. | 12.9 months | 1-Quality measures

in glioblastoma should focus on defining early advance directive

documentation, suggesting appropriate timing for hospice

enrollment, and determining which patients may benefit from early

palliative care interventions (GUIDELINES ARE NEEDED). | (28) |

| Wu | Exploring published

literature on the prevalence of ACP, end-of-life (EOL) services

utilization (including PC services), and experiences among adults

with GBM | NA | Median time from

diagnosis to PC consult measured in one study, found to be 111

days | NM | NM | NM |

Inpatient/outpatient | NM | 1-Proactive advance

care planning and appropriate use of palliative care resources are

critical aspects of high-quality care for these patients and their

caregivers/2-our findings suggest relatively low prevalence of both

of these components among GBM patients. | NM | 1-The field would

benefit from rigorous studies, particularly involving prospective

cohorts, to inform future improvements in ACP and EOL care for

adult GBM patients as well as to explore other pertinent

topics. | (36) |

| Kim | Investigate the

feasibility, value, and effectiveness of using an adapted

palliative care screening tool to improve out-patient palliative

care screening and referral of glioblastoma patients | 294 | NM | 90-100% 70-80%

50-60% 30-40% 10-20% 133 (45%) 123 (42%), 35 (12%), 3 (1%) | NM | NM | Outpatient | NM | 1-Utilizing a

palliative care screening tool may facilitate early referral to

palliative care and lead to improved patient outcomes in symptom

management and quality of life. | NM | 1-In future

studies, a query about patient acceptance regarding palliative care

is required to identify the most effective and efficient model of

early palliative care integrated with oncology care. | (35) |

| Sundararajan | Quantify the

association between symptoms, receipt of supportive and palliative

care and site of death. | 678 | NM | NM | NM | Palliative care

consult + Palliative care bed + Social work + Occupational therapy

+ Physiotherapy | inpatient | Palliative care

consult + Palliative care bed + Social work + Physiotherapy +

Occupational therapy + Speech pathology + Psychology +

Rehabilitation bed | Malignant glioma

patients with a high burden of symptoms more likely to receive

palliative care/Patients who receive palliative care more likely to

die at home | 10.4 months, and

14.3 months for all other patients with grade three tumors. 821

(41%) did not die by the end of follow up (30-June-2009), leaving

678 (34%) patients who survived longer than 120 days from diagnosis

and died within the follow-up period. | 1-Model of care for

this population should incorporate an earlier routine palliative

care referral, heralded by the onset of symptoms. The response of

treating clinicians to a relapse may include further anti-cancer

therapies, but should also routinely offer referral to palliative

care. For patients whose survival may be measured in months, this

should ensure receipt of palliative care involvement prior to their

last days of life. | (30) |

| Senderovich | Evaluate the role

of phenobarbital as a drug of choice in end-of-life (EOL)

settings. | 1 | NM | NM | NM | Subcutaneous

drug | NM | Phenobarbital | 1-Phenobarbital

reduced complications associated with EOL care + improve quality of

remaining life. | NM | 1-Information

regarding phenobarbital use for EOL care is underwhelming and

clearly should be further explored. | (24) |

| Witteler | Identify predictors

of survival after palliative radiotherapy | 31 | NM/select patients

diagnosed with GBM between (2006-2019) | Patients with (KPS

>= 60) showed improved survival compared to those with

(KPS=<50) | Surgery (Subtotal

resection or biopsy) + radiotherapy | Radiotherapy | inpatient | radiotherapy | 1-Palliative

radiotherapy increase in survival + reasonable option for patients

with limited survival prognoses. | NM | 1-Results need to

be confirmed in a larger prospective trial. | (18) |

| Glynn | Analyze survival

data and determine predictors of survival in patients aged ≥70

years treated with radiotherapy (RT) and/or Temozolomide. | 104 | NM | NM | Radiotherapy +/-

chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | NM | Radiotherapy

(hypofractionated palliative RT) | 1-Patients aged

70-75 years had survival rates similar to younger age groups.

2-Patients undergoing palliative RT had worse results. 3-Increasing

age was associated with poorer outcomes and decreased survival.

4-Age, surgical debulking, and good performance status were

independent predictors of improved survival. | 6.0 months | 1-Maximal surgical

resection if feasible for all ages. 2-For patients aged 70-75

years, if they have Debulked and good performance status, standard

approach radical RT/TMZ, 3-If they have biopsy only and good

performance status they recommend a standard approach radical

RT/TMZ versus short course RT (±TMZ), 4-If they have Poor

performance status they reccomaned to discuss short course RT

(±TMZ) versus best supportive care (BSC). 5-for patient aged more

than 76 years and they have good performance status and Debulked

they recommended to discuss short course RT (±TMZ) versus BSC, 6-If

they have Biopsy only and poor performance status they reccomanded

to have BSC. | (27) |

| Stavrinou | Examine whether a

strategy favoring active treatment of GBM at progression offers an

advantage in OS compared to supportive care alone. | 259 (center

A=103/center B=156) | June 2010-June

2015 | Center A= 91/center

B=146 | Surgery + adjuvant

radiotherapy + postoporative chemotherapy (6 cycles of

temozolomide) | Supportive

care | NM | supportive | 1-Treatment

favoring second-line treatment GBM recurrence or progression is

associated with significantly better survival after

progression. | Center A= 4.5

months/Center B= 7 months | NM | (14) |

| Ziobro | Assess the results

of treatment with temozolomide in patients with high-grade gliomas

who no longer benefit from surgical treatment and

radiotherapy. | 51,24 | NM | NM | Surgery +

Radiotherapy + Chemotherapy (lomustine) | Speech pathology +

Psychology + Pharmacy + Rehabilitation bed | NM | Temozolomide | 1-Objective benefit

from treatment with temozolomide was noted in 49% of patients in

the study group/2-Tolerability of temozolomide in patients with

malignant gliomas is good. | 32 weeks | NM | (31) |

Supportive treatment was one approach to palliative

and end-of-life care in patients with GBM, as Pompili et al

(34) aimed to identify home

palliative care and end-of-life issues in patients with GBM. They

found that midazolam was necessary in 11% of cases to achieve good

control of symptoms, such as delirium, agitation and refractory

seizures. In addition, phenobarbital was the drug of choice for

severe seizures, which occurred in 30% of cases (34).

Moreover, the use of phenobarbital was assessed by

Senderovich et al (24), in

an end-of-life setting; its use was found to reduce complications

associated with end-of-life care and improve the quality of

remaining life (24).

Kuchinad et al (29) conducted a retrospective analysis on

the management of patients with GBM, focusing on end-of-life care

practices at an academic center. Their study primarily evaluated

the use of chemotherapy as the main treatment approach for patients

with GBM, without exploring palliative interventions. By comparing

service utilization to national quality care guidelines, the

researchers identified gaps in documentation related to palliative

care and end-of-life planning. Their findings suggested that

improving these aspects could enhance the overall quality of care

provided to patients with GBM (29).

In patients receiving the full course of treatment,

including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, multiple

palliative care interventions were used to improve the quality of

life of these patients. Among such studies, Oberndorfer et

al (32) focused on symptomatic

management, including antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), steroids and

analgesia, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy in end-of-life

patients. They classified the end-of-life into phases, from phase 1

to 3. These interventions were associated with symptomatic

improvement in end-of-life patients, particularly when introduced

via the non-oral route, given that the majority of patients

developed dysphagia at this stage (32).

Lin et al (26) investigated steroids, AEDs,

benzodiazepines and allied health involvement. They found that

early palliative care resulted in a significant improvement in

pain, somnolence, symptoms and distress score; they recommended the

initiation of palliative care not only with medication treatment,

but also with rehabilitation, along with psychosocial support

(26).

Stavrinou et al (14) compared supportive care and

second-line, tumor-focused treatment at first progression in two

different groups. They found that second-line treatment, which is

tumor-focused, is more effective in terms of outcomes and in terms

of overall survival (14).

Apart from supportive care, Ziobro et al

(31) examined the effects of

palliative treatment with temozolomide in patients with high-grade

gliomas. They found this treatment to be beneficial in 49% of

patients in the study group (31).

Overall, standardizing guidelines for end-of-life

care in patients with GBM was suggested by Thier et al

(16), when they studied the

symptoms and signs in the last 10 days prior to mortality, and how

these could affect the health and care of patients (16).

In studies using radiotherapy and surgery as the

primary treatment for GBM, Witteler et al (18) used radiotherapy as a palliative care

treatment and found that it increased the survival rate, and that

it was a reasonable option for patients with a limited prognosis.

On the other hand, Reimer et al (33) used laser-induced thermotherapy (LITT)

and found that interventional MRI controlled LITT and that it

provided potential treatment benefits; MRI provides excellent

topographic accuracy due to its capability for soft tissue contrast

with high specific resolution and functional aspects (33).

Location of mortality

The location of mortality of patients with GBM

differs between hospitals and health institutes, homes and hospice

care. Out of the 19 studies included in the present systematic

review, 10 studies reported hospitals as the place of mortality

(Table IV) (16,17,24,26,28-30,32,34,36).

| Table IVLocation of mortality reported in the

included studies. |

Table IV

Location of mortality reported in the

included studies.

| Location of

mortality | Percentage of

mortality | No. of studies |

|---|

| Home | 33.33 | 7 |

| Hospital | 57.14 | 10 |

| Hospice | 19.05 | 4 |

| NM | 42.86 | 9 |

Wu et al (36)

performed a systematic review of palliative care service

utilization and advance care planning. They demonstrated that the

location of mortality was mentioned in only six out of the 16

studies included, and they similarly found that mortality in health

care institutes was the most common compared to other locations,

reaching up to 78% (36).

Mortality at home was reported in seven studies,

with the numbers of patients varying from 12 to 53% (17,19,28-30,34,36).

On the other hand, hospice care was the least mentioned among the

included studies as the site of mortality (28,29,34,38). Wu

et al (36) found that the

mortality rate in this setting ranged from 12to 64%. However,

Sundararajan et al (30)

found that this rate was 49%.

Discussion

The present study reviewed and systematically

analyzed the available literature on patients with GBM receiving

palliative care. GBM is considered to be the most common type of

brain tumor in adults. It accounts for 45.6% of all brain tumors

(1-5).

It is generally associated with a very poor prognosis, as well as

with a high recurrence rate (7,8,13). The treatment of patients with GBM

includes maximal surgical resection with adjuvant radiotherapy

(7,9).

Other modalities of treatment include supportive

care as decided upon by the treating physician; however, other

researchers advocate for tumor-specific multidisciplinary

approaches to plan the treatment (14). Palliative care is currently

recommended by the ASCO Clinical Practice Guidelines to be

considered when treating patients with GBM (20).

A variety of studies investigating the management

and palliative care of patients with GBM have been published. The

present systematic review included publications over a wide range

of years, from 1998 to 2022. It was found that 2014 accounted for

the highest number of publications, which included four

publications, followed by 2021 (Fig.

2). However, Wu et al (36) demonstrated that 2014, 2017 and 2018

were the years with the highest number of publications. Moreover,

Ironside et al (38) found

that 2012 was the year with the highest number of publications.

Mean survival age

As GBM is a disease that is associated with a poor

prognosis, improving the QOL and prolonging the life expectancy of

patients is the main aim of palliative care, not only for patients

but also for their families (39).

The total number of patients who were diagnosed with grade 4 GBM

between 2004 and 2017 and received palliative care was

2,803(40). Compared to the results

of the present study, the total number of patients who received

palliative care was 1,630, and this was expected, as some of the

selected articles did not mention the exact number of patients who

received palliative care from GBM. In terms of the ability to carry

out daily activities, the studies have a KPS >50% with variable

modalities of palliative care. Specifically, patients who received

radiotherapy had a KPS score >60%, which is consistent in

comparison with other studies that reported patients who received

radiotherapy had a KPS score >60% (38).

Palliative care in GBM

In the present systematic review, the median

survival rate reached 14 months, which was consistent with a

recently published retrospective study by Mohammed et al

(41). Providing the optimal

treatment when dealing with patients who require palliative care is

critical; it is highly recommended to establish a specific and

well-structured palliative care guideline for patients with GBM

(16,32). Moreover, further research is

warranted to define appropriate symptom management for those

patients, which will be also helpful in the process of establishing

GBM palliative care guidelines (17,34,42).

Making these guidelines universal will ensure the right of patients

to receive all and appropriate methods of palliative care and

participation from multiple specialties recommended to target and

deliver the optimal options for the patient (34).

Location of mortality

The location of mortality for patients with GBM

varies across hospitals, homes and hospice care. Out of the 19

studies included in the present systematic review, 10 of these

reported the hospital as the place of mortality (16,17,24,26,28-30,32,34,36).

This may be explained by the late hospitalization, particularly in

intensive care, which has resulted in mortality in acute hospital

care (43). Wu et al

(36) performed a systematic review

of palliative care service utilization and advance care planning,

and demonstrated that the location of mortality was mentioned in

only six out of 16 studies included; they similarly found that

mortality in health care institutes was the most common compared to

other places, reaching up to 78% (36).

However, Sundararajan et al (30) performed a retrospective study and

found that 25% of the patients died in an acute hospital bed. Thus,

the majority of the patients prefer to die at home, as shown by

Barbaro et al (43).

Moreover, home deaths were reported to range from 12 to 53.1%

(17,19,28-30,34,36),

which is less than the number reported by Wu et al (36) in their review.

As regards hospice care, the analysis revealed this

to be the least common site of mortality (17,29,30,34). Wu

et al (36) found that the

mortality rate in this setting ranged from 12 to 64%. However,

Sundararajan et al (30)

found that this rate to be 49%.

Limitations and future

implications

The present systematic review was not without any

limitations. Moreover, with such a prolonged study period, limited

studies were found focusing on palliative care at the end-of-life

for patients of GBM. In addition, end-of-life care can be

challenging, and subjective measures will be limited to assess the

needs of patients, and the outcomes of such an intervention, which

will limit the study outcome.

In conclusion, patients with GBM have a poor

prognosis and a poor survival rate, even with the optimal treatment

available. Moreover, multiple signs and symptoms can have a

tremendous burden on the end of life of patients and their

families. Palliative care in these patients aims to relieve the

burden of end-of-life care and improve the quality of life for them

and their families. Different palliative care options were studied

that led to the effective relief of patient symptoms, including

symptomatic treatment, the involvement of other services, such as

physiotherapy and some medications targeting each symptom and

radiotherapy. Overall, the early planning and involvement of these

services are critical and have a notable impact on the end-of-life

of patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AMAG and SAB were involved in data collection, data

analysis and in the writing of the manuscript. AMAA was involved in

data analysis and in the writing of the manuscript. DAH was

involved in data collection. AAH was involved in data analysis, and

in the writing and editing of the manuscript. TAS conceived and

designed the study, and was involved in writing the manuscript.

AMAG, SAB, AMAA, DAH and AAH confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Nabors LB, Portnow J, Ahluwalia M,

Baehring J, Brem H, Brem S, Butowski N, Campian JL, Clark SW,

Fabiano AJ, et al: Central nervous system cancers, version 3.2020,

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc

Netw. 18:1537–1570. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Theeler BJ and Gilbert MR: Advances in the

treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma. BMC Med.

13(293)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tykocki T and Eltayeb M: Ten-year survival

in glioblastoma. A systematic review. J Clin Neurosci. 54:7–13.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, Read W,

Steinberg D, Lhermitte B, Toms S, Idbaih A, Ahluwalia MS, Fink K,

et al: Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance

temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in

patients with glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

318:2306–2316. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner AA, Kesari

S, Steinberg DM, Toms SA, Taylor LP, Lieberman F, Silvani A, Fink

KL, et al: Maintenance therapy with tumor-treating fields plus

temozolomide vs temozolomide alone for glioblastoma: A randomized

clinical trial. JAMA. 314:2535–2543. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Waite K, Kruchko C

and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain

and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United

States in 2014-2018. Neuro Oncol. 23 (12 Suppl 2):iii1–iii105.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR,

Gokaslan ZL, Shi W, DeMonte F, Lang FF, McCutcheon IE, Hassenbusch

SJ, Holland E, et al: A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with

glioblastoma multiforme: Prognosis, extent of resection, and

survival. J Neurosurg. 95:190–198. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Curran WJ Jr, Scott CB, Horton J, Nelson

JS, Weinstein AS, Fischbach AJ, Chang CH, Rotman M, Asbell SO,

Krisch RE, et al: Recursive partitioning analysis of prognostic

factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group malignant glioma

trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 85:704–710. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Walker MD, Green SB, Byar DP, Alexander E,

Batzdorf U, Brooks WH, Hunt WE, MacCarty CS, Mahaley MS Jr, Mealey

J Jr, et al: Randomized comparisons of radiotherapy and

nitrosoureas for the treatment of malignant glioma after surgery. N

Engl J Med. 303:1323–1329. 1980.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller

M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn

U, et al: Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide

for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 352:987–996. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent

MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B,

Belanger K, et al: Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and

adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in

glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of

the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 10:459–466. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ozdemir-Kaynak E, Qutub AA and

Yesil-Celiktas O: Advances in glioblastoma multiforme treatment:

New models for nanoparticle therapy. Front Physiol.

9(170)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Roy S, Lahiri D, Maji T and Biswas J:

Recurrent glioblastoma: Where we stand. South Asian J Cancer.

4:163–173. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Stavrinou P, Kalyvas A, Grau S, Hamisch C,

Galldiks N, Katsigiannis S, Kabbasch C, Timmer M, Goldbrunner R and

Stranjalis G: Survival effects of a strategy favoring second-line

multimodal treatment compared to supportive care in glioblastoma

patients at first progression. J Neurosurg. 131:1136–1141.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D,

Dionne-Odom JN, Ernecoff NC, Hanmer J, Hoydich ZP, Ikejiani DZ,

Klein-Fedyshin M, Zimmermann C, et al: Association between

palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 316:2104–2114. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Thier K, Calabek B, Tinchon A, Grisold W

and Oberndorfer S: The last 10 days of patients with glioblastoma:

Assessment of clinical signs and symptoms as well as treatment. Am

J Hosp Palliat Care. 33:985–988. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Walbert T and Khan M: End-of-life symptoms

and care in patients with primary malignant brain tumors: A

systematic literature review. J Neurooncol. 117:217–224.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Witteler J, Schild SE and Rades D:

Palliative radiotherapy of primary glioblastoma. In Vivo.

35:483–487. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Check JH, Wilson C, Cohen R and Sarumi M:

Evidence that Mifepristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, can

cross the blood brain barrier and provide palliative benefits for

glioblastoma multiforme grade IV. Anticancer Res. 34:2385–2388.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER,

Balboni TA, Basch EM, Firn JI, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Phillips T,

et al: Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care:

American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline

update. J Clin Oncol. 35:96–112. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Triebel KL, Martin RC, Nabors LB and

Marson DC: Medical decision-making capacity in patients with

malignant glioma. Neurology. 73:2086–2092. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA and

van der Heide A: The effects of advance care planning on

end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 28:1000–1025.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ,

Wouters EFM and Janssen DJA: Efficacy of advance care planning: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc.

15:477–489. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Senderovich H, Waicus S and Mokenela K:

Evading seizures: Phenobarbital reintroduced as a multifunctional

approach to end-of-life care. Case Rep Oncol. 15:218–224.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Harrison RA, Ou A, Naqvi SMAA, Naqvi SM,

Weathers SS, O'Brien BJ, de Groot JF and Bruera E: Aggressiveness

of care at end of life in patients with high-grade glioma. Cancer

Med. 10(8387)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lin E, Rosenthal MA, Eastman P and Le BH:

Inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with

glioblastoma in a tertiary hospital. Intern Med J. 43:942–945.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Glynn AM, Rangaswamy G, O'Shea J, Dunne M,

Grogan R, MacNally S, Fitzpatrick D and Faul C: Glioblastoma

Multiforme in the over 70's: ‘To treat or not to treat with

radiotherapy?’. Cancer Med. 8:4669–4677. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hemminger LE, Pittman CA, Korones DN,

Serventi JN, Ladwig S, Holloway RG and Mohile NA: Palliative and

end-of-life care in glioblastoma: Defining and measuring

opportunities to improve care. Neurooncol Pract. 4:182–188.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kuchinad KE, Strowd R, Evans A, Riley WA

and Smith TJ: End of life care for glioblastoma patients at a large

academic cancer center. J Neurooncol. 134:75–81. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sundararajan V, Bohensky MA, Moore G,

Brand CA, Lethborg C, Gold M, Murphy MA, Collins A and Philip J:

Mapping the patterns of care, the receipt of palliative care and

the site of death for patients with malignant glioma. J Neurooncol.

116:119–126. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ziobro M, Rolski J, Grela-Wojewoda A,

Zygulska A and Niemiec M: Effects of palliative treatment with

temozolomide in patients with high-grade gliomas. Neurol Neurochir

Pol. 42:210–215. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Oberndorfer S, Lindeck-Pozza E, Lahrmann

H, Struhal W, Hitzenberger P and Grisold W: The end-of-life

hospital setting in patients with glioblastoma. J Palliat Med.

11:26–30. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Reimer P, Bremer C, Horch C, Morgenroth C,

Allkemper T and Schuierer G: MR-monitored LITT as a palliative

concept in patients with high grade gliomas: Preliminary clinical

experience. J Magn Reson Imaging. 8:240–244. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Pompili A, Telera S, Villani V and Pace A:

Home palliative care and end of life issues in glioblastoma

multiforme: Results and comments from a homogeneous cohort of

patients. Neurosurg Focus. 37(E5)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kim JY, Peters KB, Herndon JE II and

Affronti ML: Utilizing a palliative care screening tool in patients

with glioblastoma. J Adv Pract Oncol. 11:684–692. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wu A, Ruiz Colón G, Aslakson R, Pollom E

and Patel CB: Palliative care service utilization and advance care

planning for adult glioblastoma patients: A systematic review.

Cancers (Basel). 13(2867)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Golla H, Nettekoven C, Bausewein C, Tonn

JC, Thon N, Feddersen B, Schnell O, Böhlke C, Becker G, Rolke R, et

al: Effect of early palliative care for patients with glioblastoma

(EPCOG): A randomised phase III clinical trial protocol. BMJ Open.

10(e034378)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ironside SA, Sahgal A, Detsky J, Das S and

Perry JR: Update on the management of elderly patients with

glioblastoma: A narrative review. Ann Palliat Med. 10:899–908.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Teoli D, Schoo C and Kalish VB: Palliative

Care. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023 Feb 6 [cited 2024 Apr 15];

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537113/.

|

|

40

|

Pando A, Patel AM, Choudhry HS, Eloy JA,

Goldstein IM and Liu JK: Palliative care effects on survival in

glioblastoma: Who receives palliative care? World Neurosurg.

170:e847–e857. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Mohammed S, Dinesan M and Ajayakumar T:

Survival and quality of life analysis in glioblastoma multiforme

with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy: A retrospective study. Rep Pract

Oncol Radiother. 27:1026–1036. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Seekatz B, Lukasczik M, Löhr M, Ehrmann K,

Schuler M, Keßler AF, Neuderth S, Ernestus RI and van Oorschot B:

Screening for symptom burden and supportive needs of patients with

glioblastoma and brain metastases and their caregivers in relation

to their use of specialized palliative care. Support Care Cancer.

25:2761–2770. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Barbaro M, Blinderman CD, Iwamoto FM,

Kreisl TN, Welch MR, Odia Y, Donovan LE, Joanta-Gomez AE, Evans KA

and Lassman AB: Causes of death and end-of-life care in patients

with intracranial high-grade gliomas: A retrospective observational

study. Neurology. 98:e260–e266. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|