Introduction

Psammoma bodies (PBs) are round, layered calcified

structures considered to form through dystrophic calcification, a

process in which calcium is deposited locally in damaged or dying

tissues, despite normal blood calcium levels and no abnormalities

in the metabolism of calcium (1).

PBs are usually associated with papillary tumors and are most often

observed in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Consequently,

microcalcifications on an ultrasound are more frequently observed

in classic papillary thyroid carcinoma than in other thyroid cancer

types, and their histological presence is a hallmark feature of

papillary thyroid carcinoma (2). PBs

are present in 40-50% of paraffin-embedded sections and in 11-35%

of fine-needle aspiration smears of papillary thyroid carcinoma

(1). They most often occur on tumor

cells located at the tips of papillary structures, likely due to

the effects of vascular thrombosis (3). When present in thyroid areas remote

from a tumor, PBs are typically found between follicles or within

the interlobular septa, regions that contain the lymphatic and

vascular structures of the gland (4). However, although rare, PBs can be found

in a benign thyroid gland, and their presence without accompanying

papillary thyroid carcinoma can pose a diagnostic challenge

(5). The present study describes a

rare case of PBs found in a benign thyroid gland and also performed

a brief review of the literature. The references cited in the

present case report have been assessed for reliability (6), and the manuscript was prepared

according to the CaReL guidelines (7).

Case report

Patient information

A 28-year-old female patient presented to Smart

Health Tower (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq) with a 3-month history of weight

loss, decreased appetite and generalized weakness, without other

associated symptoms. An analysis of her past medical and surgical

history did not reveal any notable findings, with no family history

of similar conditions and no history of radiation exposure.

Clinical findings

An examination revealed a firm, mildly enlarged

thyroid gland without palpable cervical lymphadenopathy.

Diagnostic approach

Laboratory investigations revealed that the level of

thyroid-stimulating hormone was 0.85 µIU/ml (normal range, 0.8-6.0

µIU/ml) and the level of free T4 was 20.1 pmol/l (normal range,

12.8-27 pmol/l). A neck ultrasound revealed bilateral thyroid

nodules, both classified as TI-RADS 3 according to the American

College of Radiology TI-RADS system (https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Tools-and-Reference/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/TI-RADS).

The right nodule measured 25x21x19 mm, and the left measured

17x15x13 mm. As part of the pre-operative assessment for total

thyroidectomy, vocal cord function was evaluated and was normal

bilaterally. Additional investigations revealed a thyroglobulin

level of 6.15 ng/ml (normal range, 3.5-77 ng/ml) and a serum

calcium level of 9.27 mg/dl (normal range, 8.6-10.0 mg/dl).

Therapeutic intervention

Under general anesthesia, a total thyroidectomy was

performed through a collar incision, with the careful preservation

of both recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

Hemostasis was successfully achieved, and the wound was closed in

layers, with a drain placed on the left side. The excised tissue

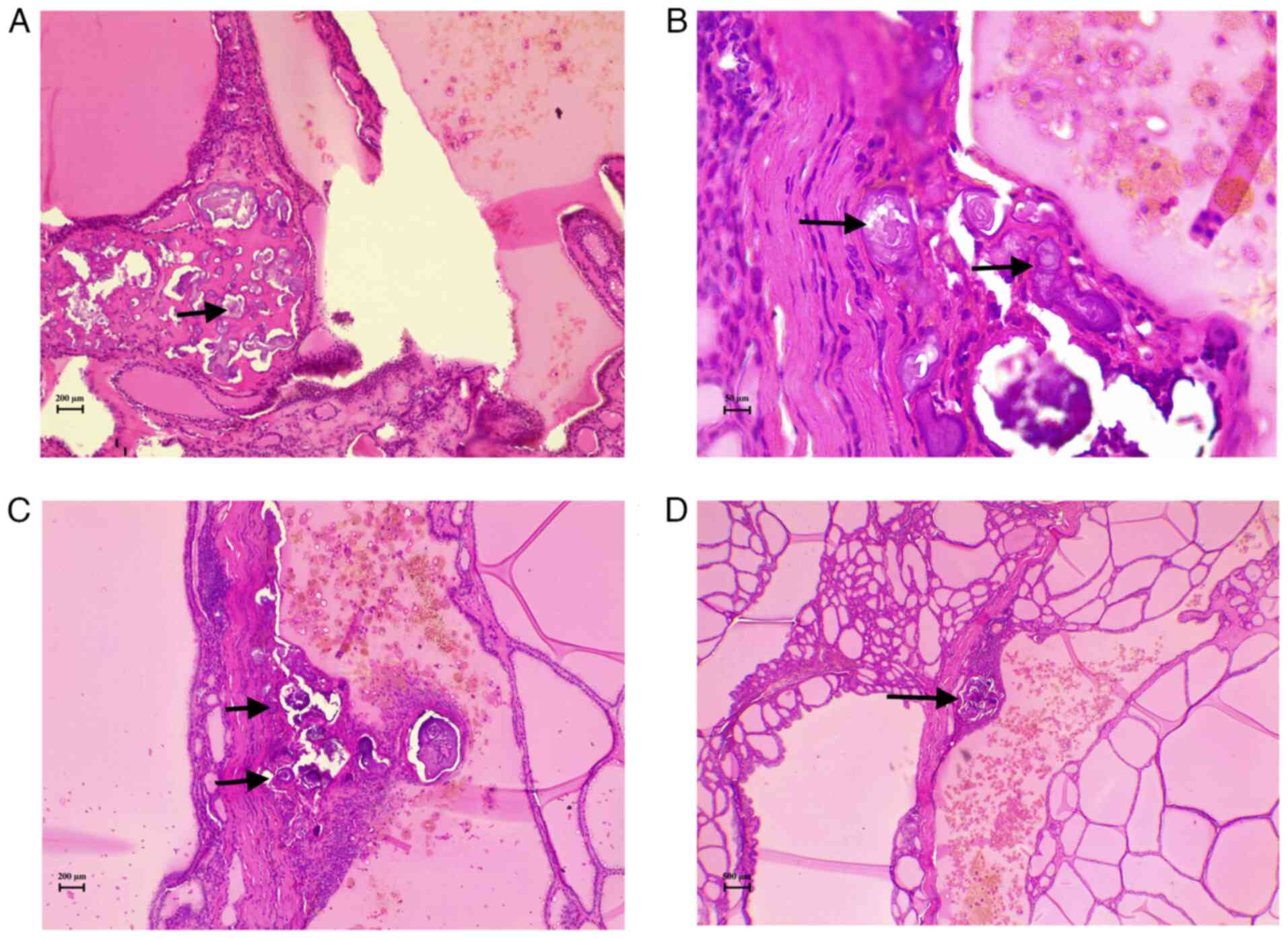

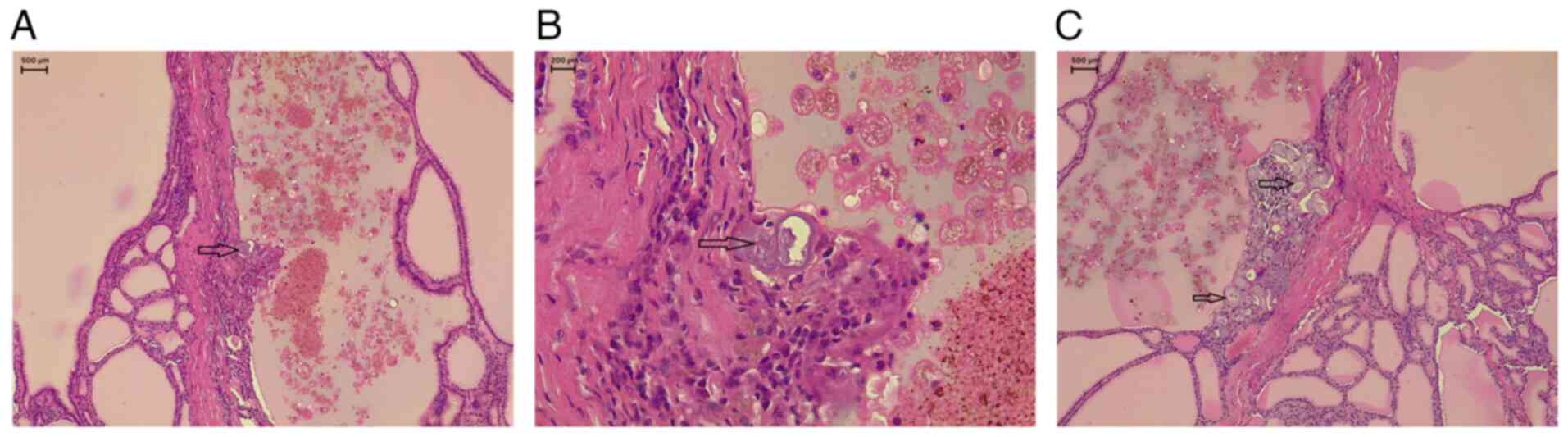

was sent for a histopathological examination. The sections

(5-µm-thick) were paraffin-embedded and fixed in 10% neutral

buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h. They were then

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Bio Optica Co.) for

1-2 min at room temperature. The sections were then examined under

a light microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). Post-operatively, the

patient remained stable with no complications, and serum calcium

levels were within the normal range (9.3 mg/dl). The

histopathological examination revealed thyroid follicular nodular

disease (TFND) with focal lymphocytic thyroiditis, and PBs were

identified without any evidence of suspicious epithelial cell

components (Figs. 1 and 2). To ensure a comprehensive evaluation,

the entire thyroid was submitted for additional sectioning to

exclude microscopic carcinoma, no malignancy was identified.

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient recovered well without complications and

was discharged 2 weeks following admission, and was prescribed

levothyroxine 100 µg once daily,, with a follow-up appointment

scheduled. A multidisciplinary team evaluated her and decided that

she would undergo regular follow-ups to monitor for any signs of

recurrence.

Discussion

It is well-established that PBs are commonly

associated with carcinomas in different organs, such as papillary

thyroid carcinoma, ovarian serous tumors, meningioma and others,

and this association is considered diagnostically critical

(8). However, PBs may be found in

benign conditions, such as TFND with papillary hyperplasia,

follicular adenomas, including the oncocytic variant, Hashimoto's

thyroiditis and other less common condition (3). A total of 4 cases of PBs and

psammomatous calcifications associated with benign conditions were

identified in the literature and were reviewed herein; 2 cases were

male and 2 cases were female (Table

I) (5,9-11).

Half of the cases involved thyroid-region lesions and half were

pediatric patients (2/4). All 4 cases required surgical excision,

while fine-needle aspiration was only used in 1 out of the 4 cases.

Computed tomography was used in half the cases (2/4) and other

modalities in the remainder. Histopathological analysis confirmed

PBs or psammomatous calcifications in every case, and all patients

had favorable outcomes with no recurrence documented on follow-up

(100%). These findings emphasize that psammomatous calcifications

can occur in diverse benign conditions, are best identified by

histology, and are commonly managed successfully by surgical

resection.

| Table IReview of some cases of PBs and

psammomatous calcifications associated with benign conditions in

the literature. |

Table I

Review of some cases of PBs and

psammomatous calcifications associated with benign conditions in

the literature.

| First author, year of

publication | Age, years | Sex | Diagnosis | Clinical

findings | Imaging tests | Microscopic

examinations | Fine needle

aspiration | Treatment | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Cardisciani,

2022 | 74 | F | Pseudonodular

hyperplastic oncocytic metaplasia in a background of chronic

lymphocytic Hashimoto thyroiditis. | History of

multinodular goiter pressing on the trachea. | Not mentioned. | Lymphocytic Hashimoto

thyroiditis with nodular oncocytic metaplasia, and PBs. IHC: -ve

HBME-1, galectin-3 and CK-19. | Not performed. | Total

thyroidectomy. | Is in stable

condition. | (5) |

| Mohammed, 2015 | 9 | M | Leiomyoma of the

thyroid gland. | Painless thyroid

mass. | X-ray: Tracheal

deviation to the left. | PBs and foci of

calcification. HPE: +ve SMA, vimentin and desmin, -ve cytokeratin

cocktail. | Benign smooth muscle

tumor. | Right

hemi-thyroidectomy. | No recurrence after 2

years. | (9) |

| Vemavarapu, 2011 | 46 | F | Benign Brenner tumor

of the ovary. | Progressively

enlarging pelvic mass. | US: Cystic lesion in

the left adnexa with punctate calcifications. CT: solid components

and calcifications. | Dystrophic

calcifications lining the cyst wall, obscuring the epithelium,

largely replacing it, with extensive stromal PC, and no nuclear

atypia or mitosis. | Not mentioned. | Total robotic

hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. | Is in stable

condition. | (10) |

| Ayala, 2003 | 3 | M | Benign thyroglossal

duct cyst. | Asthma symptoms. | CT: Hyoid bone

mass. | Thyroglossal duct

remnant with cystic spaces, and PC, no evidents of malignancy. | Not mentioned. | Excision of the

mass. | Is in stable

condition. | (11) |

Microcalcifications are observed in <5% of

adenomas on thyroid ultrasound, and these correspond to PB clusters

when examined cytologically or histologically (12). By contrast, macrocalcifications

appear on an ultrasound as bright echogenic spots that produce

shallow posterior acoustic shadowing (<1 mm deep), and are less

strongly linked to malignancy histologically. Coarse calcifications

upon microscopy are irregular dystrophic deposits usually resulting

from tissue necrosis. Distinguishing between microcalcifications

and macrocalcifications on ultrasound can be challenging, as it

depends not only on the level of experience of the operator, but

also on the technical capabilities of the imaging equipment

(2).

Rossi et al (3) evaluated cases of PBs in benign thyroid

lesions across five centers over a period of 14 years and

identified only 26 patients, with 16 of them being female. The most

common diagnoses were TFND and adenomas (12 patients each), of

which 11 cases were oncocytic adenomas and 1 case was a follicular

adenoma, as well as 2 cases of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. The precise

origin and clinical relevance of PBs in non-cancerous conditions

are still uncertain and continue to be investigated. The presence

of PBs in non-cancerous conditions raises the dilemma of whether

PBs in benign lesions should be observed as early signs of

malignancy and treated accordingly, or regarded as incidental

findings (3).

TFND, which was identified in the current case and

was previously referred to as multinodular goiter, is a benign,

non-inflammatory condition marked by an enlarged thyroid gland and

multifocal proliferation of thyroid follicular cells, resulting in

clonal and non-clonal nodules with diverse architectures. It is

more frequently observed in women, and iodine deficiency resulting

in an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone release, which

stimulates hyperplasia of thyroid follicular epithelial cells, is

considered a primary contributing factor. TFND may present with

diverse histological features, that mimic well-differentiated

thyroid carcinomas. Distinguishing between concerning histological

changes resulting from a benign hyperplastic process and those

indicative of true neoplastic transformation is essential (13).

Ultrastructural studies of PBs of the thyroid found

in both tumor and non-tumor areas, suggests that they likely

represent the final stage of two biological processes: The first

involves the basement membrane in the vascular core of neoplastic

papillae becoming thickened, followed by vascular thrombosis,

calcification and tumor cell death. Secondly, necrosis and

calcification occur within the intralymphatic tumor thrombi, which

are located either near the tumor or in the opposite lobe of the

thyroid (1). PBs should be

differentiated from calcified colloid and dystrophic calcification

(4). There is an increased presence

of PBs and a higher frequency of lymph node metastases in tumors

with rearranged during transfection (RET) rearrangements. This

indicates a potential complex association between RET pathway

alterations, PB formation and nodal involvement (14). PBs located outside the tumor in

patients with classic type papillary thyroid carcinoma may be

linked to a greater likelihood of multifocal tumors, spread beyond

the thyroid, and lymph node metastasis compared to tumors that

contain PBs only within the tumor itself. Non-tumor PBs in patients

with lymph node involvement also exhibit a notably increased rate

of viable tumor cells present within lymphatic vessels compared to

those without such findings (14).

For the histopathological analysis of PBs, the

tissue is fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin,

sectioned into 5-µm-thick slices, and subsequently stained with

hematoxylin and eosin (3). PBs are

frequently observed to be encircled by cells and typically display

a concentric pattern, appearing either acidophilic or basophilic

when stained with Papanicolaou stain (8). PBs are less commonly detected in

fine-needle aspiration cytology, although their presence strongly

indicates carcinoma. However, they are not dependable indicators

unless accompanied by other distinct cytological features such as

nuclear grooves, nuclear pseudoinclusions and true papillary

formations (12). Ellison et

al (15) reported that PBs were

identified in only eight of 313 fine-needle aspirates, PBs alone

had a 50% positive predictive value for papillary carcinoma,

whereas combined cytological features were 100% predictive. PBs

were found in 80% of papillary thyroid cases when combined features

were present compared with 14% detection of PB alone in their study

(15).

The presence of PBs in benign lesions remains a

topic of diagnostic uncertainty. Submitting the entire thyroid

tissue for histological analysis, particularly in lobectomy

specimens, is advised to rule out microscopic papillary thyroid

carcinoma (4). Multiple and deeper

sections of thyroid parenchyma need to be examined to search for

occult carcinoma. However, some cases remain tumor-free, supporting

the occurrence of PBs in benign conditions (3). Hunt and Barnes (4) evaluated 29 patients (22 females) with

PBs not initially associated with tumors. A histological

examination, however, revealed carcinoma in the thyroid gland in 27

patients, and 12 of these were observed alongside microscopic,

incidental thyroid carcinomas, emphasizing the importance of

thoroughly sampling the entire surgical specimen. In their study,

23 patients had PBs associated with high-risk features according to

the AMES criteria, as well as the presence of the tall cell variant

as an added risk factor (4). A total

of 5 patients experienced disease recurrence, but no deaths were

attributed to thyroid cancer. In the total of 29 patients, a total

of 19 patients had a total thyroidectomy, while ten others

underwent lobectomy. The 2 patients without any carcinoma underwent

a lobectomy, and the entire surgical specimen was not sent for a

histopathological examination (4).

In the study by Rossi et al (3), 24 out of the 26 patients with PBs

underwent a total thyroidectomy.

Since the patient in the present study underwent a

simple total thyroidectomy and PBs were identified afterward,

intraoperative neuroendoscopy and magnetic resonance imaging were

not performed. It should be noted that sonographic categorization

is subject to both operator expertise and equipment variability,

which may influence nodule classification and reproducibility,

including this case.

In conclusion, PBs may occur in benign TFND and can

mimic malignancy on imaging and cytology, definitive diagnosis

relies on thorough histopathological sampling.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AMA and AMS were major contributors to the

conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for

related studies. TOS, HAA and FHK were involved in the conception

and design of the study, in hte literature review and in the

writing of the manuscript. SFA, IJH and SHH were involved in the

literature review, in the design of the study, in the critical

revision of the manuscript and in the processing of the table. RMA

and HAY were the pathologists who performed the diagnosis of the

case. FHK and AMA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for their participation in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Das DK: Psammoma body: A product of

dystrophic calcification or of a biologically active process that

aims at limiting the growth and spread of tumor? Diagn Cytopathol.

37:534–41. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

O'Connor E, Mullins M, O'Connor D, Phelan

S and Bruzzi J: The relationship between ultrasound

microcalcifications and psammoma bodies in thyroid tumours: A

single-institution retrospective study. Clin Radiol. 77:e48–e54.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rossi ED, Agarwal S, Erkilic S, Hang JF,

Jalaly JB, Khanafshar E, Ladenheim A and Baloch Z: Psammoma bodies

in thyroid: Are they always indicative of malignancy? A

multi-institutional study. Virchows Arch. 485:853–858.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hunt JL and Barnes EL:

Non-tumor-associated psammoma bodies in the thyroid. Am J Clin

Pathol. 119:90–94. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cardisciani L, Policardo F, Tralongo P,

Fiorentino V and Rossi ED: What psammoma bodies can represent in

the thyroid. What we recently learnt from a story of lack of

evidence. Pathologica. 114:373–375. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, Kakamad FH, Ahmed

JO, Baba HO, Hassan MN, Bapir R, Rahim HM, Omar DA, Kakamad SH, et

al: Predatory publishing lists: A review on the ongoing battle

against fraudulent actions. Barw Med J. 2:26–30. 2024.

|

|

7

|

Prasad S, Nassar M, Azzam AY,

García-Muro-San José F, Jamee M, Sliman RKA, Evola G, Mustafa AM,

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, et al: CaReL guidelines: A consensus-based

guideline on case reports and literature review (CaReL). Barw Med

J. 2:13–19. 2024.

|

|

8

|

Parwani AV, Chan TY and Ali SZ:

Significance of psammoma bodies in serous cavity fluid: A

cytopathologic analysis. Cancer. 102:87–91. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mohammed AZ, Edino ST and Umar AB:

Leiomyoma of the thyroid gland with psammoma bodies. Niger Med J.

56:71–73. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Vemavarapu L, Alatassi H and

Moghadamfalahi M: Unusual presentation of benign cystic Brenner

tumor with exuberant psammomatous calcifications. Int J Surg

Pathol. 19:120–122. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ayala C, Healy GB, Robson CD and Vargas

SO: Psammomatous calcification in association with a benign

thyroglossal duct cyst. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

129:241–243. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Triggiani V, Guastamacchia E, Licchelli B

and Tafaro E: Microcalcifications and psammoma bodies in thyroid

tumors. Thyroid. 18:1017–1018. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Flora R and Mukhopadhyay S: Multinodular

goitre: Pitfalls in the interpretation of thyroid follicular

nodular disease. Diagnostic Histopathology. 30:301–307. 2024.

|

|

14

|

Gubbiotti MA, Baloch Z, Montone K and

Livolsi V: Non-tumoral psammoma bodies correlate with adverse

histology in classic type papillary thyroid carcinoma. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 6(3)2022.

|

|

15

|

Ellison E, Lapuerta P and Martin SE:

Psammoma bodies in fine-needle aspirates of the thyroid: predictive

value for papillary carcinoma. Cancer. 84:169–175. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|