Introduction

Human sparganosis is a food-borne zoonosis caused by

the plerocercoid larvae (sparganum) of tapeworms belonging to the

genus Spirometra. Although human sparganosis is relatively

infrequent globally, the majority of cases occur primarily in East

and Southeast Asian countries due to dietary habits and traditional

medical practices (1). The disease

poses a critical public health concern due to its transmission

through multiple pathways, including the ingestion of contaminated

water, the consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater frogs or

snakes, and the application of raw meat poultices to treat

infections. Sparganosis is principally characterized by a slowly

migrating subcutaneous nodule(s) and can invade the brain, eyes,

breasts, spinal cord and subcutaneous tissues, often resulting in

severe illness (2). In the first

week following parasite infection, the host may develop an

inflammatory cellular infiltrate. Tunnel-like structures appear 2

weeks thereafter, and fibroblast proliferation occurs 4 weeks

following infection.

The present study reports an extremely rare case of

sparganosis found in the mons pubis of a 26-year-old female patient

who was immunocompetent. The purpose of the present case report was

to enhance the understanding of sparganosis and emphasize that

parasitic infection should be considered as a differential

diagnosis when encountering a patient presenting with durable,

wandering skin nodules.

Case report

A 26-year-old Chinese female patient presented to

People's Hospital of Xindu District, Chengdu, Sichuan, China, in

November, 2023 with a subcutaneous nodule in the mons pubis. Of

note, 2 months prior, the patient complained that subcutaneous

nodules appeared on the abdomen, which were not treated due to her

history of lipoma and normal skin temperature and color. These

nodules disappeared spontaneously in ~10 days. However, a nodule

was later found at the mons pubis that persisted for >1 month,

prompting her to return to the hospital for treatment. During the

course of the disease, there was no obvious pain in the nodule, and

the patient did not suffer from headaches or nausea. The complete

blood count from laboratory tests revealed an increased in

peripheral eosinophilia. Routine blood tests were performed,

including a complete blood count, hematocrit level and platelet

count tests, liver function tests and renal function tests, all of

which fell within the normal reference range; the results did not

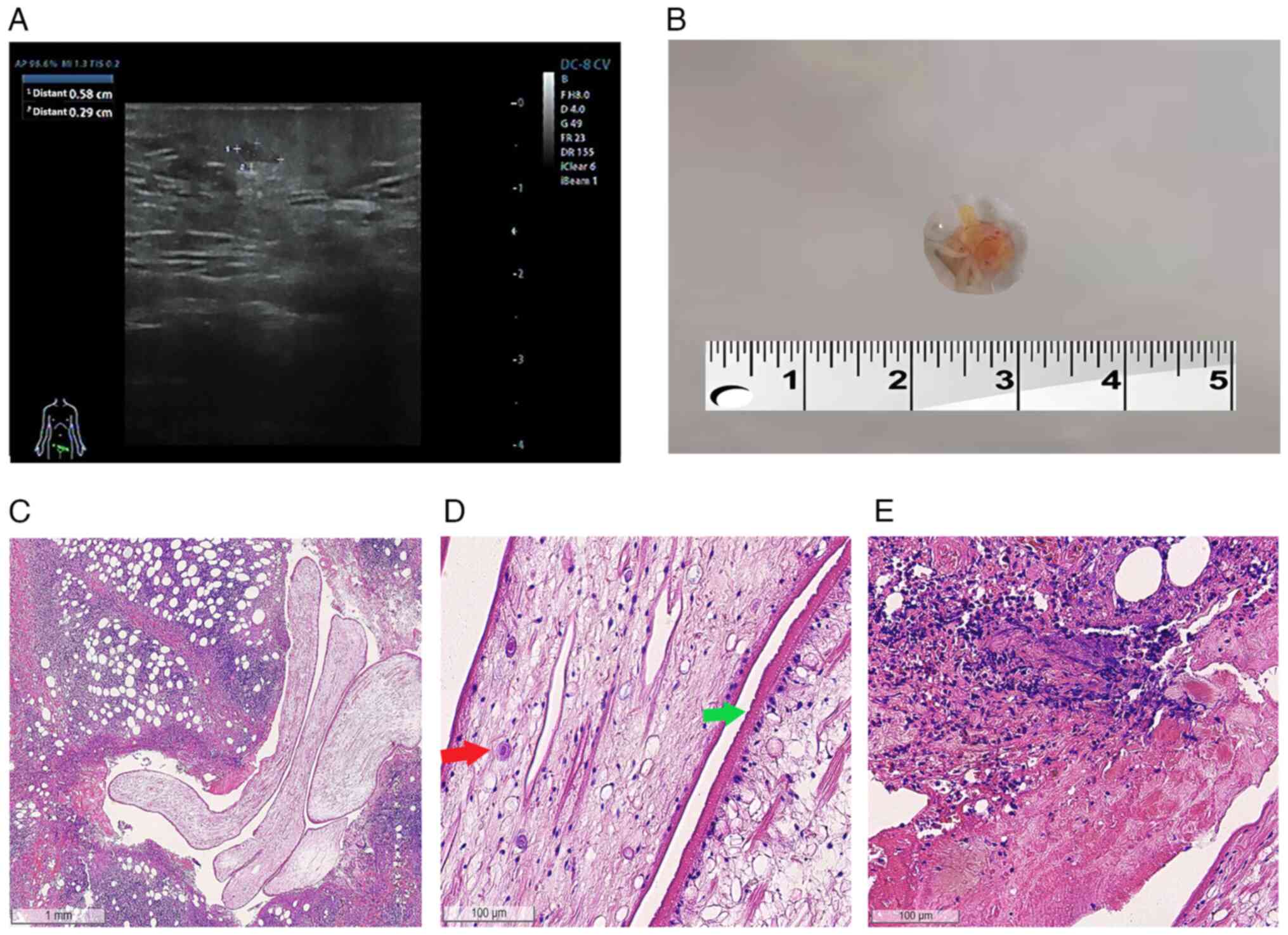

reveal anything uncommon. An ultrasonography revealed hypoechoic

nodules detectable subcutaneously at the mons pubis mass, measuring

~0.6x0.3 cm in size, with clear borders and a regular morphology

(Fig. 1A). No obvious blood flow

signal was detected in the above lesions on color Doppler flow

imaging (CDFI).

The nodule located on the mons pubis was completely

surgically resected, and filamentous wormlike objects were found

within the resected tissue. The precise length of the sample could

not be determined due to fragmentation during extraction; however,

it was >0.4 cm (Fig. 1B). A

histological examination revealed parasites characterized by a

deep-folded tegument and calcareous corpuscles, as well as

peripheral inflammatory changes in the parasite body, accompanied

by inflammatory cell infiltration. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining for all sections presented in Fig. 1C-E was independently performed by the

Department of Pathology, People's Hospital of Xindu District,

Chengdu, China. The detailed procedures were as follows: Tissues

were fixed in formalin at room temperature for 24 h, followed by

processing into paraffin blocks after sampling. Paraffin sections

were cut at a thickness of 4 µm, which were then floated and

flattened on warm water at 45˚C. The sections were retrieved onto

glass slides and baked in an oven at 65˚C. For subsequent H&E

staining, paraffin sections were first dewaxed and rehydrated. They

were then stained with hematoxylin solution (MilliporeSigma) for

3-5 min, rinsed thoroughly with running water, and blued with warm

water. Following this, the sections were stained with eosin

solution (MilliporeSigma) for 2 min. Finally, the sections

underwent dehydration, clearing, and mounting procedures before

being observed under an optical microscope (LEICA DM3000; Leica

Microsystems GmbH). In conjunction with the epidemiological history

and the pathological examination, the patient was ultimately

diagnosed with subcutaneous sparganosis (Fig. 1C). Subsequently, anti-sparganum IgG

was detected in the serum of the patient using enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (data not shown).

A pathological examination further revealed that the

walls of these parasites were multilayered with a thick

eosinophilic microvillous noncellular tegument, and numerous small

clear vesicles were noted under the tegument. Moreover, numerous

secretory canaliculi, subcutaneous cells and calcareous bodies were

observed within the cytoplasm (Fig.

1D). Scolex, suckers, a digestive tract and reproductive organs

were not present. A pathological examination of the largest lesion

surrounding the worm revealed granulomatous inflammation and

tunnel-like necrosis with eosinophilic, neutrophilic and

lymphocytic infiltration (Fig. 1E).

Sparganosis was confirmed based upon these results. The nodule was

completely surgically resected, and wound healing proceeded without

complications. No oral anthelminthic treatment was administered,

and no subsequent lesions developed. Serological tests for

anti-sparganum IgG were negative at 8 months following surgery, and

no recurrence was observed.

Discussion

Due to the constant occurrence of sparganosis in

China, measures are required to prevent and control the disease.

First, food safety and prevention measures for this disease should

be emphasized and improved. The crucial point in preventing human

sparganosis is to cease the consumption of raw or undercooked frog,

snake and contaminated water, and the application of raw frog flesh

or skin to open wounds.

Sparganosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused

by the larvae (spargana) of the genus Spirometra, which is widely

distributed globally and threatens human health (3,4). Humans

serve as accidental secondary intermediate hosts, acquiring

infection through the consumption of raw or undercooked meat from

intermediate hosts, such as frogs or snakes, or by ingesting water

contaminated with infected copepods. While cases have been

sporadically documented across the globe, the disease is more

prevalent in Asian regions, particularly in China, Korea, and

Thailand (5,6). Sparganosis infections are primarily

associated with the consumption of undercooked frogs or snakes,

which serve as key sources of transmission. Following ingestion by

humans, the larvae preferentially migrate into soft subcutaneous

tissues; however, they may occasionally migrate into vital organs,

such as the brain, spinal cord, or eyes, causing deleterious

effects.

The clinical diagnosis of sparganosis involves a

physical examination of cutaneous and other nodules, a computed

tomography (CT) assessment of the location and dimension of the

nodule, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the demonstration

of a mass lesion or vasculopathy. Despite their obvious value,

these procedures lack specificity and do not provide a definitive

diagnosis (7). Laboratory methods

for the diagnosis of sparganosis include the macro- and microscopic

identification of spargana recovered through tissue biopsy,

biochemical tests, serological assays and molecular techniques. In

rare cases, next-generation sequencing has been used to identify

some uncommon parasite species (8).

The sparganum larvae are characterized as white, wrinkled and

ribbon-shaped, varying from a few millimeters to 50 cm in length

(4). Histopathological analysis

reveals fibrous cystic tunnels containing live worms, eosinophilic

granulomas, and intact worm structures exhibiting loose stroma,

smooth muscle, secretory tegument and calcareous bodies.

Biochemical tests may reveal pronounced peripheral eosinophilia

(9). By contrast, the diagnosis of

visceral or cerebral sparganosis poses significant challenges, and

serological testing, particularly ELISA for anti-sparganum

antibodies, serves as the primary diagnostic tool due to its high

sensitivity and specificity.

In the case in the present study, the involvement of

the mons pubis was extremely rare. Precisely due to its unique

location, the initial diagnosis invariably leaned toward

gynecological conditions. Relevant differential diagnoses were

excluded through examinations, including HPV-DNA testing, ELISA and

tissue biopsy. The presence of subcutaneous mobile masses in the

medical history suggested that parasitic infection should be highly

considered.

Treatment is primarily based on the surgical removal

of the larva. No medical treatment standard has been defined for

patients with masses not suitable for surgical resection, and

high-dose praziquantel (repeated cycles of 50-75 mg/kg body

weight/day for 10 days) has been used to treat infection (10,11). To

the best of our knowledge, mons pubis sparganosis has rarely been

reported. In the case described herein, the patient underwent

successful surgical removal. Following treatment, the patient

exhibited a reduction in eosinophil levels, and serological testing

for anti-sparganum IgG yielded negative results, indicating the

efficacy of surgical intervention for mons pubis sparganosis. The

patient recovered well following the procedure.

In conclusion, the present case report, the young

female patient had a subcutaneous nodule of the mons pubis.

Sparganosis was diagnosed by ELISA and tissue biopsy. This rare

case of sparganum infection is a reminder that when patients

presenting with persistent and migratory skin nodules are

encountered, regardless of the location, parasitic infection should

be considered as a differential diagnosis. Furthermore, it is

considered that health education on avoiding the consumption of

undercooked frogs and unboiled water is of utmost importance in

preventing parasitic infections.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was financially supported by the

Chengdu Health Commission Medical Research Project (grant no.

2024040).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JZ and QL contributed equally to the design of the

study, in the collection of clinical specimens and information, and

manuscript preparation. QT contributed to the analysis of the

patient's data and data from the literature. QT and JZ were

responsible for the patient's treatment. JZ and QL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The patient provided written informed consent for

her inclusion in the present case report.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of the present case report and any related

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu Q, Li MW, Wang ZD, Zhao GH and Zhu XQ:

Human sparganosis, a neglected food borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect

Dis. 15:1226–1235. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Li MW, Song HQ, Li C, Lin HY, Xie WT, Lin

RQ and Zhu XQ: Sparganosis in mainland China. Int J Infect Dis.

15:e154–e156. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhang X, Duan JY, Shi YL, Jiang P, Zeng

DJ, Wang ZQ and Cui J: Comparative mitochondrial genomics among

Spirometra (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) and the molecular

phylogeny of related tapeworms. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 117:75–82.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kuchta R, Kołodziej-Sobocińska M, Brabec

J, Młocicki D, Sałamatin R and Scholz T: Sparganosis (spirometra)

in Europe in the molecular era. Clin Infect Dis. 72:882–890.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shin EH, Guk SM, Kim HJ, Lee SH and Chai

JY: Trends in parasitic diseases in the Republic of Korea. Trends

Parasitol. 24:143–150. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Liu W, Gong T, Chen S, Liu Q, Zhou H, He

J, Wu Y, Li F and Liu Y: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention of

sparganosis in Asia. Animals (Basel). 12(1578)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhu Y, Ye L, Ding X, Wu J and Chen Y:

Cerebral sparganosis presenting with atypical postcontrast magnetic

resonance imaging findings: A case report and literature review.

BMC Infect Dis. 19(748)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Du B, Tao Y, Ma J, Weng X, Gong Y, Lin Y,

Shen N, Mo X and Cao Q: Identification of sparganosis based on

next-generation sequencing. Infect Genet Evol. 66:256–261.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lin Q, Ouyang JS, Li JM, Yang L, Li YP and

Chen CS: Eosinophilic pleural effusion due to Spirometra mansoni

spargana: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect

Dis. 34:96–98. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhang P, Zou Y, Yu FX, Wang Z, Lv H, Liu

XH, Ding HY, Zhang TT, Zhao PF, Yin HX, et al: Follow-up study of

high-dose praziquantel therapy for cerebral sparganosis. PLoS Negl

Trop Dis. 13(e0007018)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hong D, Xie H, Wan H, An N, Xu C and Zhang

J: Efficacy comparison between long-term high-dose praziquantel and

surgical therapy for cerebral sparganosis: A multicenter

retrospective cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.

12(e0006918)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|