Introduction

A total of ~20 million people worldwide succumb

every year due to AS with the increased of the incidence rate of

atherosclerosis (AS) (1). In 2018,

the death induced by cardiovascular disease was the first cause of

death among urban and rural residents in China (2). Of note, vascular endothelial cells

are lined up in the inner surface of blood vessels, are in direct

contact with the metabolite-related endogenous danger signals in

the circulatory system. Consequently, the impairment and

dysfunction of vascular endothelial cells would impair vasodilation

and increase endothelium-dependent permeability, which is strongly

correlated with the development of AS. Reactive oxygen species

(ROS) is the key factor that contributes to the injury of vascular

endothelial cells (3). Therefore,

protecting endothelial cells from the damage of ROS is one of the

effective strategies to prevent AS. As H2O2

is a well-known ROS, it is often used as a stimulant of in

vitro model for oxidative injury in AS which presented as

ROS-intermediated destruction of lipids and proteins contributing

to damage of the membrane in a series of cells (4).

It is known that soy is the main source of

high-quality proteins (5) and the

nutritional value of soy is mainly attributed to the content of

phytochemical content, particularly the uniquely rich content of

isoflavone (6). Particularly,

Genistein (GEN), the most active soy isoflavone, is a potent

antioxidant and anti-browning agent both in vivo and in

vitro, which exhibit preventive and therapeutic effects on

cancer, post-menopausal syndrome, osteoporosis and a series of

cardiovascular diseases (7,8). GEN

pretreatment significantly attenuated

H2O2-induced peroxide formation and inhibited

ischemia-induced ROS production, including enhancement of

superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)

activity in Caco-2 cells and cerebral ischemia mouse (9,10).

Moreover, GEN can also attenuate apoptosis by reversing the ratio

of Bcl-2 to Bax and inhibiting the activity of the pro-apoptotic

caspase-9 and caspase-3 in the primary rat neurons (11).

However, the effect of GEN on endothelial cells

after oxidative damage remains obscure and the mechanism by which

GEN attenuates oxidative stress-induced endothelial cell injury

also needs further study to verify. Therefore, the present study

aimed to further determine the effect of GEN on the oxidative

damage of human vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) caused by

H2O2 and further elucidated its potential

associated signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HUVECs were provided by the Basic Medical College of

Jilin University (Changchun, China). In brief, HUVECs were cultured

in RPMI-1640 medium (P004-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (F8318, Gibco) and 1%

penicillin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. The treatment

conditions of H2O2 and GEN (cat. no.

HY-14596; MedChemExpress) were determined according to previous

studies (10,12). Subsequent experiments were divided

into four groups: control group, GEN treatment group,

H2O2 treatment group and a combined treatment

group of GEN and H2O2.

Cell viability assay

H2O2 (130 µM) was used to

induce oxidation injury in HUVECs (1×105 cells per well

was seeded) according to pre-experiments and previous studies

(10,12). GEN with different concentrations

(100 nM, 1 µM, 10 µM) were pretreated to reduce the oxidant injury

of H2O2. The CCK-8 kit (ck04, Dojindo, the

absorbance values at 450 nm were recorded) was used to detect cell

viability referring to operating instructions. A total of 10 µl

CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C with 5%

CO2 in incubator for 2 h. An optimal dose of GEN was

utilized for its antioxidant effect and for observing its

antioxidant mechanism.

Intracellular ROS assay

HUVECs were seeded in six-well plates at a density

of 1.2×105/ml per well for 24 h. Then,

Dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) Assay (cat. no.

S0033S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was implemented. A

total of 10 µmol/l GEN was added to the GEN and GEN +

H2O2 group for 1 h; 130 µmol/l

H2O2 was added to the GEN +

H2O2 group and the H2O2

group for 1 h. After the treatment was completed, the six-well

plates were taken out from the incubator and washed by adding 1 ml

of PBS to each well once, then the PBS was discarded. The DCFH-DA

probes were diluted with the serum-free RPMI-1640 culture medium at

the ratio of 1:1,000. The discarded culture medium from the

six-well plates was aspirated, and the cells were washed three

times with 1 ml of serum-free RPMI-1640 culture medium per well to

avoid eluting the cells from the wall. After aspirating the culture

medium used for washing, 1 ml of prepared DCFH-DA probe was added

to each well and the six-well plate loaded with the probe was

incubated in the incubator for 40 min to prevent degradation and

inactivation of the probe, and the HUVECs were washed with

serum-free cell RPMI-1640 culture medium for 3 times after 40 min

to wash away the DCFH-DA that had not entered into the cells. Then,

200 µl of 0.25% trypsin was added to each well, the digestion was

terminated, centrifugation followed and the supernatant was

discarded. A total of 200 µl of PBS was added to each tube and was

blown several times to make a single-cell suspension, which was

transferred to a flow tube protected from light, and put on a flow

cytometer (C6, BD, USA, 488 nm excitation light and 525 nm emission

used) for ROS detection.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected using Annexin V-FITC kit

(cat. no. C1062L; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) (13). In brief, HUVECs were seeded in

six-well plates at a density of 1.2×105/ml per well for

24 h. Then, the desired concentrations of GEN and

H2O2 were added and washed once with PBS

according to previous description. After that, cells were collected

and supplemented with Annexin V-FITC conjugate. The flow tubes were

incubated for 20 min in a dark place at room temperature and

analyzed immediately by a flow cytometer (C6 and BD Accuri™ C6

Software, version 227.4).

Determination of intracellular enzyme

activity

Cells in logarithmic growth phase were cultured in

5-mm cell culture dishes, and cell samples were collected after

adding GEN and H2O2. The cells were removed

from the incubator, placed in an ice bath, and the adherent cells

were collected in 1.5 ml EP tubes by scraping with a cell scraper.

A total of 100 µl of cell lysate was added to each tube and placed

in liquid nitrogen for 3 min, 37°C water bath for 3 min, and

repeated three times. The cells were pre-cooled at 4°C in advance

in a centrifuge and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the

supernatant was taken for the assay of enzyme activity. The

intracellular enzyme activity was detected according to the

instructions of GPx kits (cat. no. S0058; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) (14), SOD kits

(cat. no. BC0175; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) (15), and reduced

glutathione (GSH) kits (cat. no. BC1175; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), respectively (16).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

RNA [An RNA extraction kit was used (12183018A,

PureLink™ RNA; Thermo Fisher)] was extracted from HUVECs and qPCR

[The TBGreen® Premix Ex Taq (Takara) was used] was

conducted after reverse transcription according to the reagent

manufacturer's instructions (T2210, Solarbio, China). GAPDH was

used as a reference gene. Primer sequences are listed in Table I. Thermocycling conditions were as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles including denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 55°C

and extension at 72°C for 30 sec. A standard measure of mRNA

expression (2-ΔΔ cycle threshold) was calculated (17).

| Table I.Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene name | Primer sequences

(5′→3′) |

|---|

| Nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related | F:

AGTCCAGAAGCCAAACTGACAGAAG |

| factor 2 | R:

GGAGAGGATGCTGCTGAAGGAATC |

| Superoxide | F:

ATCCTCTATCCAGAAAACACGG |

| dismutase 1 | R:

GCGTTTCCTGTCTTTGTACTTT |

| Heme

oxygenase-1 | F:

CCTCCCTGTACCACATCTATGT |

|

| R:

GCTCTTCTGGGAAGTAGACAG |

| Bax | F:

CGAACTGGACAGTAACATGGAG |

|

| R:

CAGTTTGCTGGCAAAGTAGAAA |

| Bcl-2 | F:

GACTTCGCCGAGATGTCCAG |

|

| R:

GAACTCAAAGAAGGCCACAATC |

| Caspase-3 | F:

CCAAAGATCATACATGGAAGCG |

|

| R:

CTGAATGTTTCCCTGAGGTTTG |

| GAPDH | F:

AGATCCCTCCAAAATCAAGTGG |

|

| R:

GGCAGAGATGATGACCCTTTT |

Western blot analysis

A total of 50 µg of cell protein were collected from

four groups [Negative control (NC), GEN, GEN +

H2O2, H2O2] with a cell

scraper and lysed with RIPA (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and 1% PMSF (cat. no. ST506; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Electrophoresis was carried out, placing 50 µg of

protein in each well, using 10% preformed gel. After transferring

the proteins to the membrane (PVDF), it was blocked with 5% skimmed

milk powder at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, the membrane

was incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies (all diluted at 1:1,000): Nuclear factor

erythroid2-related factor 2 (Nrf2; cat. no. 12721S), heme oxygenase

(HO-1; cat. no. 43966), SOD1 (37385S), Bax (cat. no. 5023S; all

from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), Caspase-3 (cat. no. 14220S;

Abcam) and Bcl-2 (cat. no. orb10173; Biorbyt, Ltd). Following the

primary incubation, the membrane was incubated with horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3,000; cat. no.

7074S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h at room

temperature. As the same grouping (NC, GEN, GEN +

H2O2, H2O2) in western

blot detection, the same GAPDH (cat. no. AC001; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd.) was used as control in each experiment which was

repeated at least three times. ImageJ software (1.52a, National

Institutes of Health) was used to analyze the grey value of each

resulting image, and the control protein was used to normalize the

grey values of the target protein for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 8 (Dotmatics). One way ANOVA was used for multiple group

comparisons, corrected by Bonferroni's method. Two independent

samples unpaired t-test was used for comparison between two groups.

All experiments were repeated more than 3 times. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

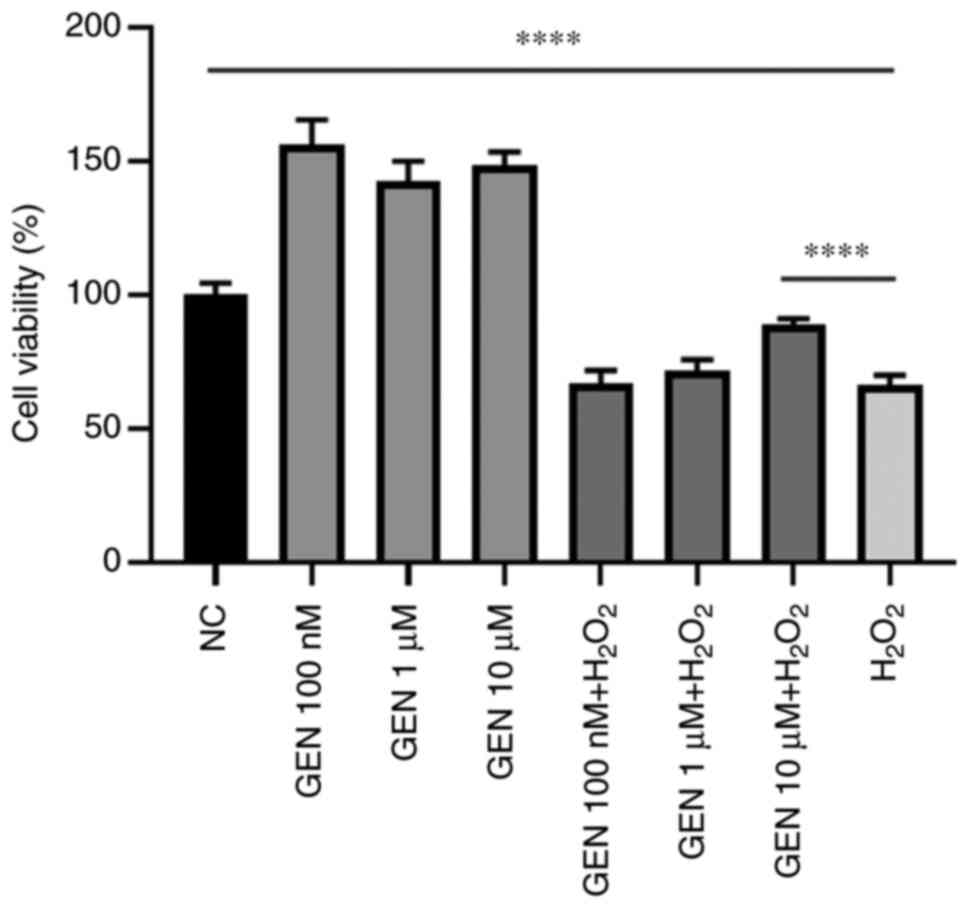

Effect of GEN on the viability of

HUVECs after H2O2 stress

To determine whether GEN could play a protective

role against H2O2-induced cell damage, in

combination with H2O2 stress for 1 h, HUVECs

were pretreated with GEN (100 nM, 1 and 10 µM) for 1 h. As

demonstrated in Fig. 1, the cell

viability increased significantly after pretreatment of GEN

compared with control group (****P<0.0001). Thus, 10 µM GEN

pretreatment for 1 h was used as the treatment condition for the

following experiments.

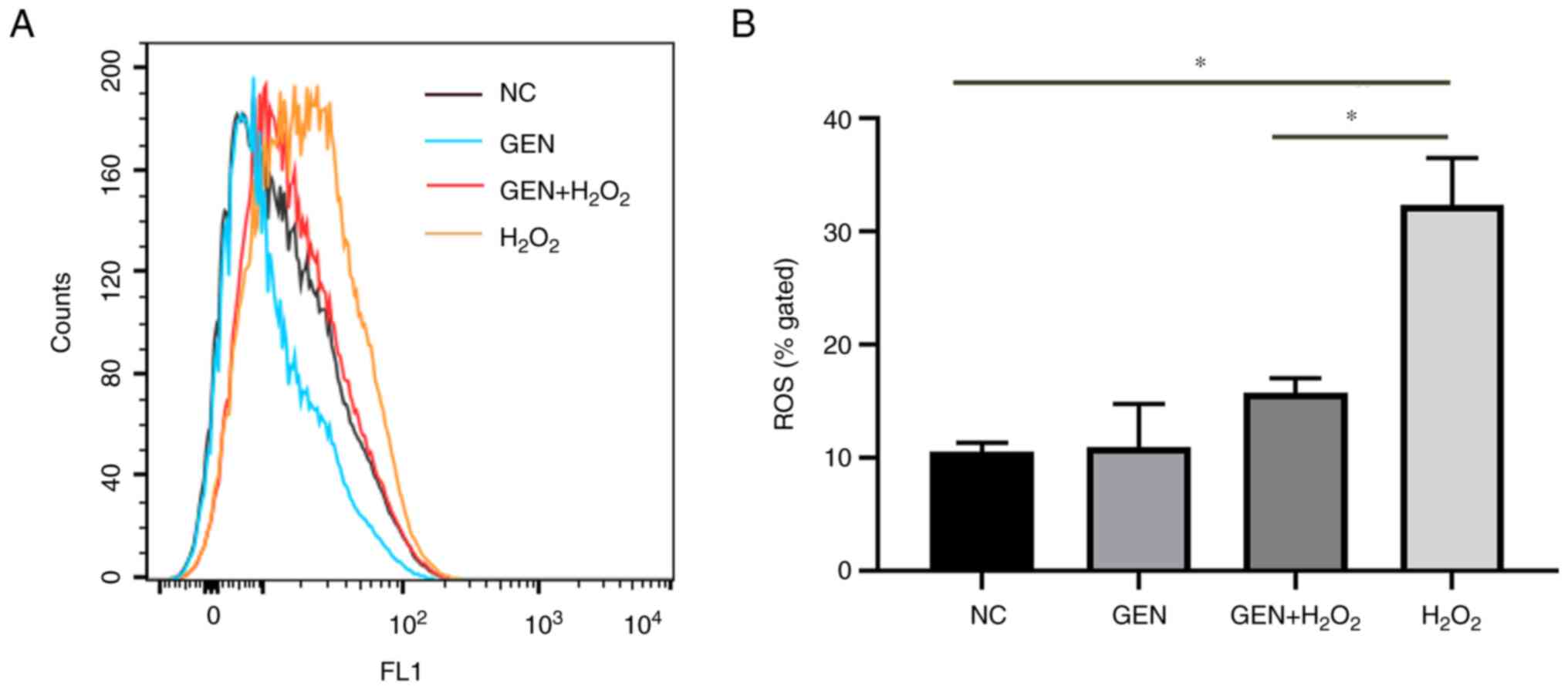

Effect of GEN on oxidative

injury-induced intracellular ROS

To investigate whether GEN could reduce the level of

intracellular ROS, DCFH-DA fluorescent probe was used to detect the

intracellular ROS in the labeled cells. As revealed in Fig. 2, intracellular ROS levels increased

significantly after H2O2 stress (*P<0.05).

By contrast, after GEN pretreatment, the intracellular ROS levels

reduced significantly (*P<0.05).

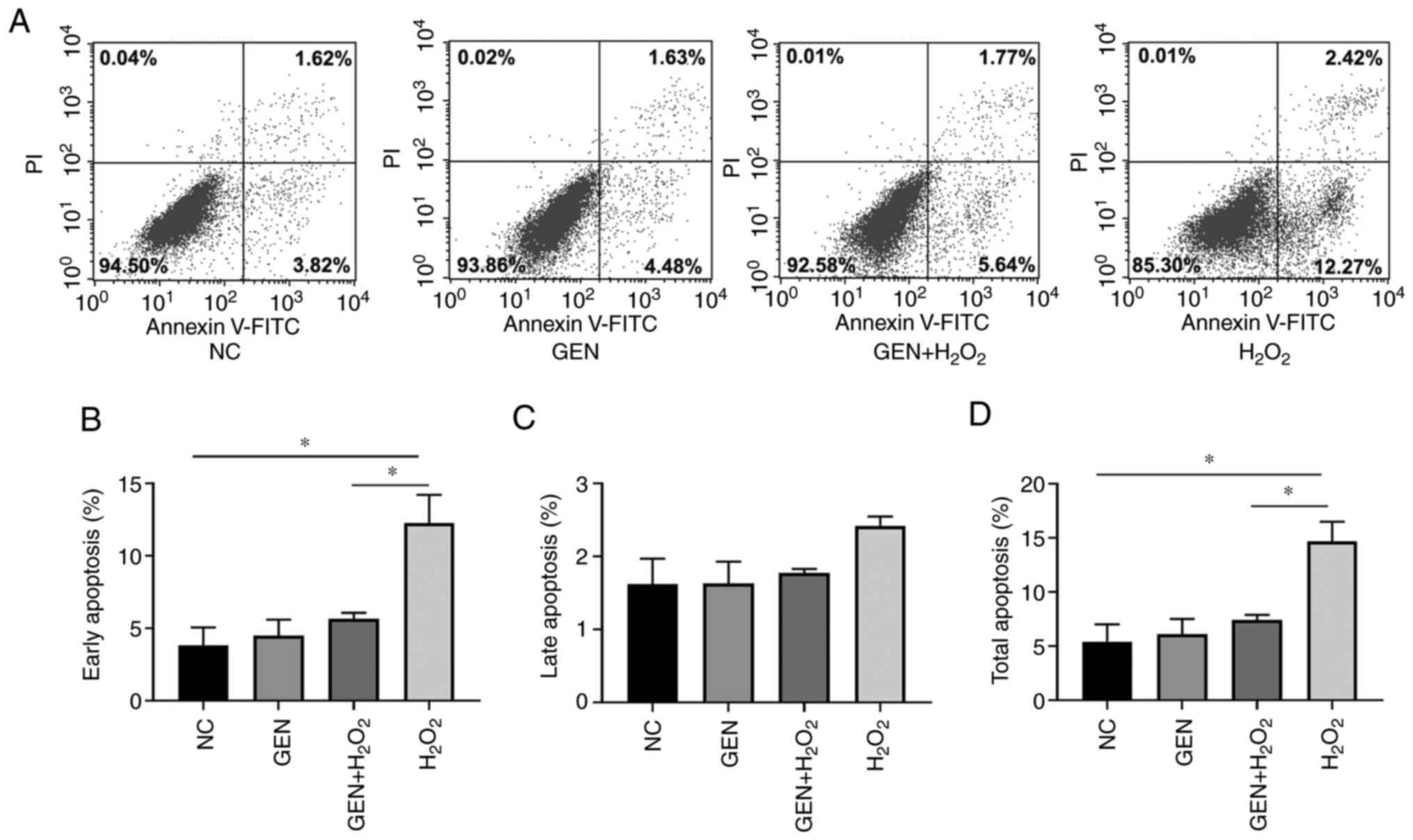

Effect of GEN on the apoptosis of

HUVECs after H2O2 stress

To verify whether GEN could further attenuate the

occurrence of apoptosis by attenuating the aggregation of ROS,

Annexin-V/FITC Assay was applied to stain cells pretreated with the

GEN. The apoptotic rates were counted separately for different

periods. As shown in Fig. 3, GEN

decreased the early apoptotic rate and the total apoptotic rate

significantly (P<0.05), while no effect was detected for the

late apoptotic rate.

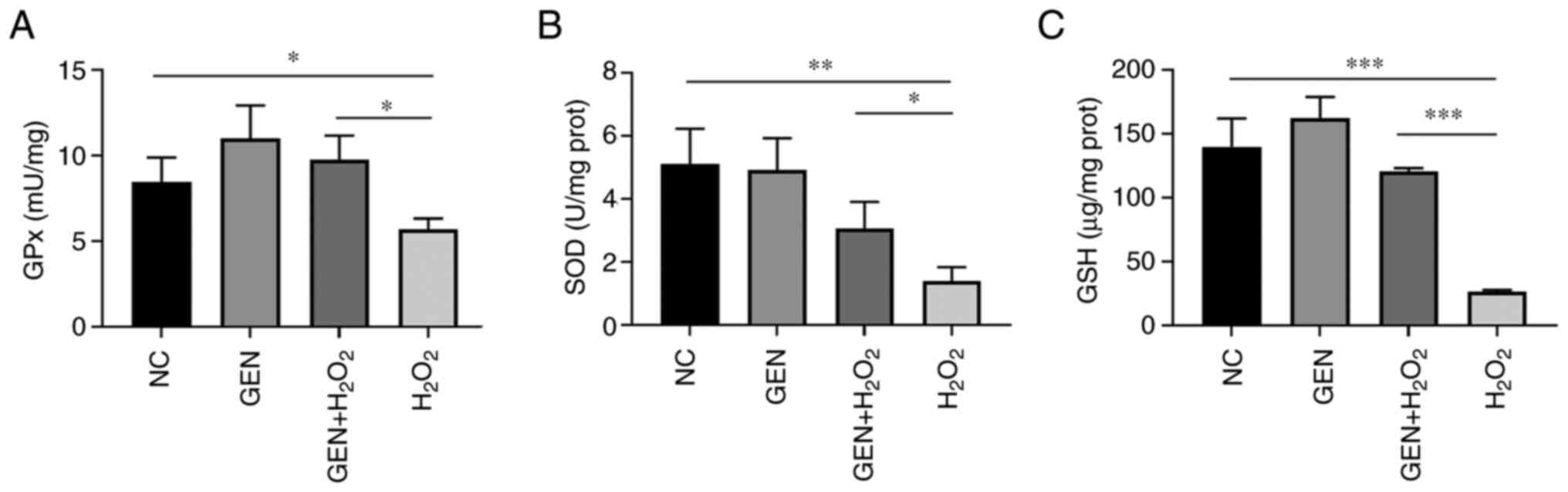

Effect of GEN on intracellular enzyme

activity of HUVECs after H2O2 stress

To further verify the mitigating effect of GEN on

the intracellular ROS, intracellular redox-responsive enzymes were

measured. As demonstrated in Fig.

4A, the enzyme activity of intracellular GPx was significantly

reduced in the H2O2 group (*P<0.05) and

increased after GEN pretreatment (*P<0.05). The intracellular

SOD activity was also significantly reduced (**P<0.01) and

increased after GEN pretreatment (*P<0.05; Fig. 4B). In addition, the activity of

intracellular GSH was significantly reduced in the

H2O2 group (***P<0.001) and increased

after GEN pretreatment (***P<0.001; Fig. 4C).

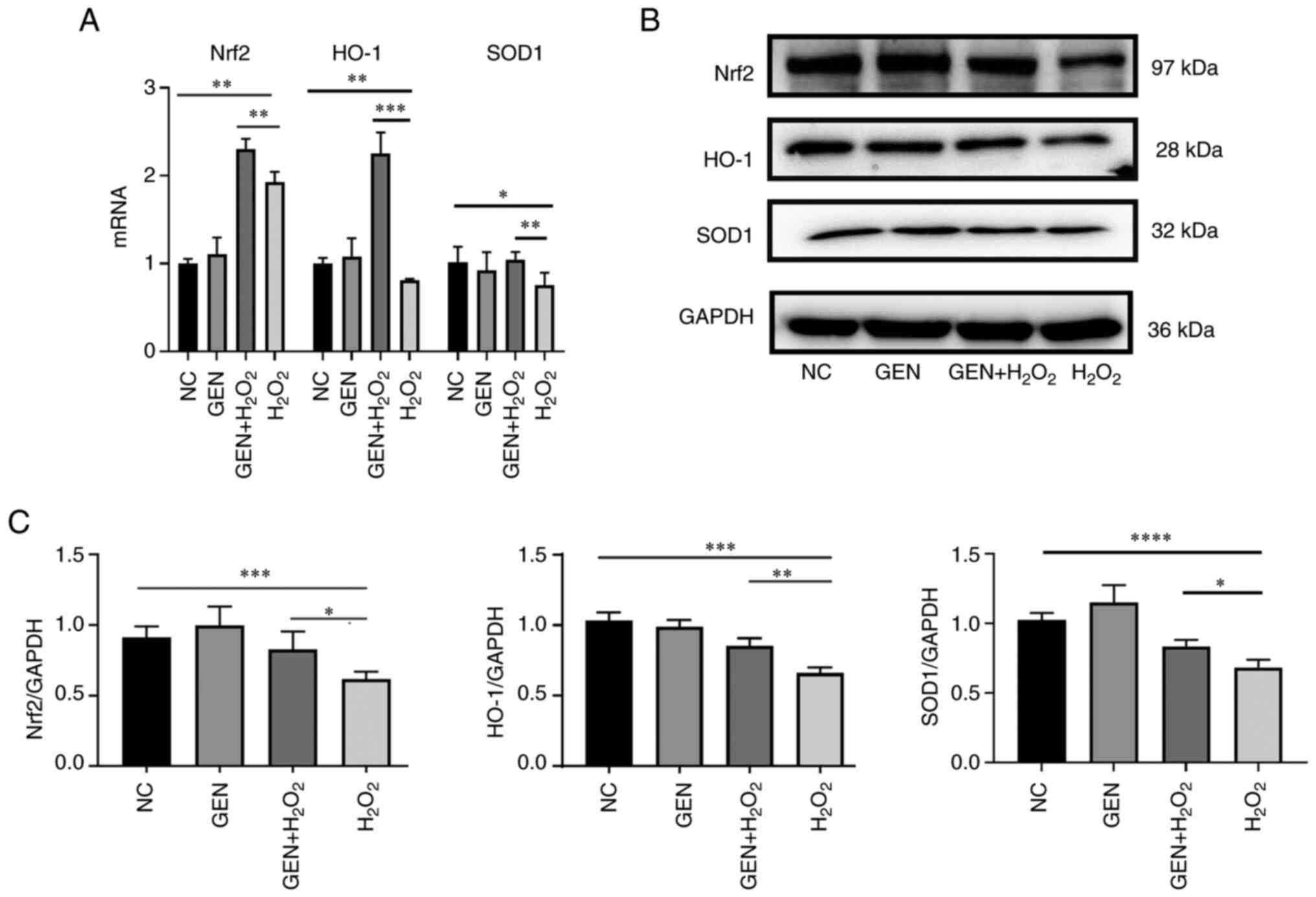

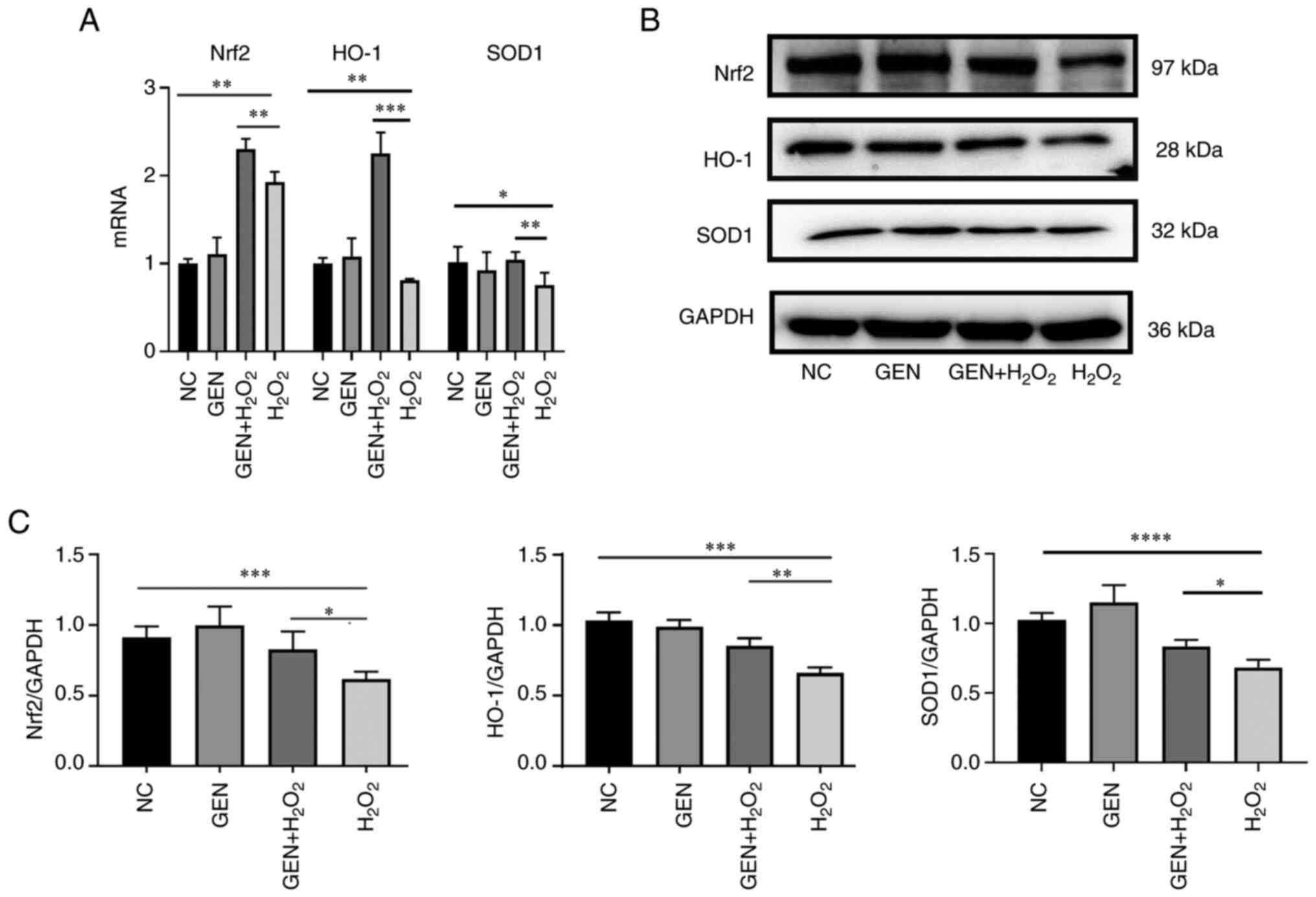

Effect of GEN on the expression of

Nrf2-related signaling pathway

To verify whether the protective effect of GEN on

oxidative damage after H2O2 stress was

mediated through the Nrf2 pathway, the expression of Nrf2

pathway-related molecules (Nrf2, HO-1 and SOD1) was detected. As

revealed in Fig. 5A, GEN

pretreatment increased the mRNA expression of Nrf2 (**P<0.01),

HO-1 (P<0.001) and SOD1 (**P<0.01) simultaneously under

H2O2 stress. As shown in Fig. 5B and C, compared with the control

group, the protein expression of Nrf2 (***P<0.001), HO-1

(***P<0.001) and SOD1 (****P<0.0001) significantly decreased

after H2O2 stress. Compared with the

H2O2 group, the protein expression of Nrf2

(*P<0.05), HO-1 (**P<0.01) and SOD1 (*P<0.05) increased

significantly after GEN pretreatment.

| Figure 5.mRNA and protein expression levels of

Nrf2, SOD1 and HO-1. (A) The mRNA transcription levels of Nrf2,

SOD1 and HO-1 in different groups. (B) Nrf2 pathway-related protein

were determined by western blotting. (C) Statistical results of

corresponding protein bands. GEN pretreatment increased the mRNA

transcription of Nrf2, HO-1 and SOD1 simultaneously under

H2O2 stress. Compared with the control group,

the protein expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and SOD1 decreased after

H2O2 stress. Compared with the

H2O2 group, the protein expression of Nrf2,

HO-1 and SOD1 increased significantly after GEN pretreatment.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. Nrf2,

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; SOD1, superoxide

dismutase 1; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; GEN, Genistein; NC, negative

control. |

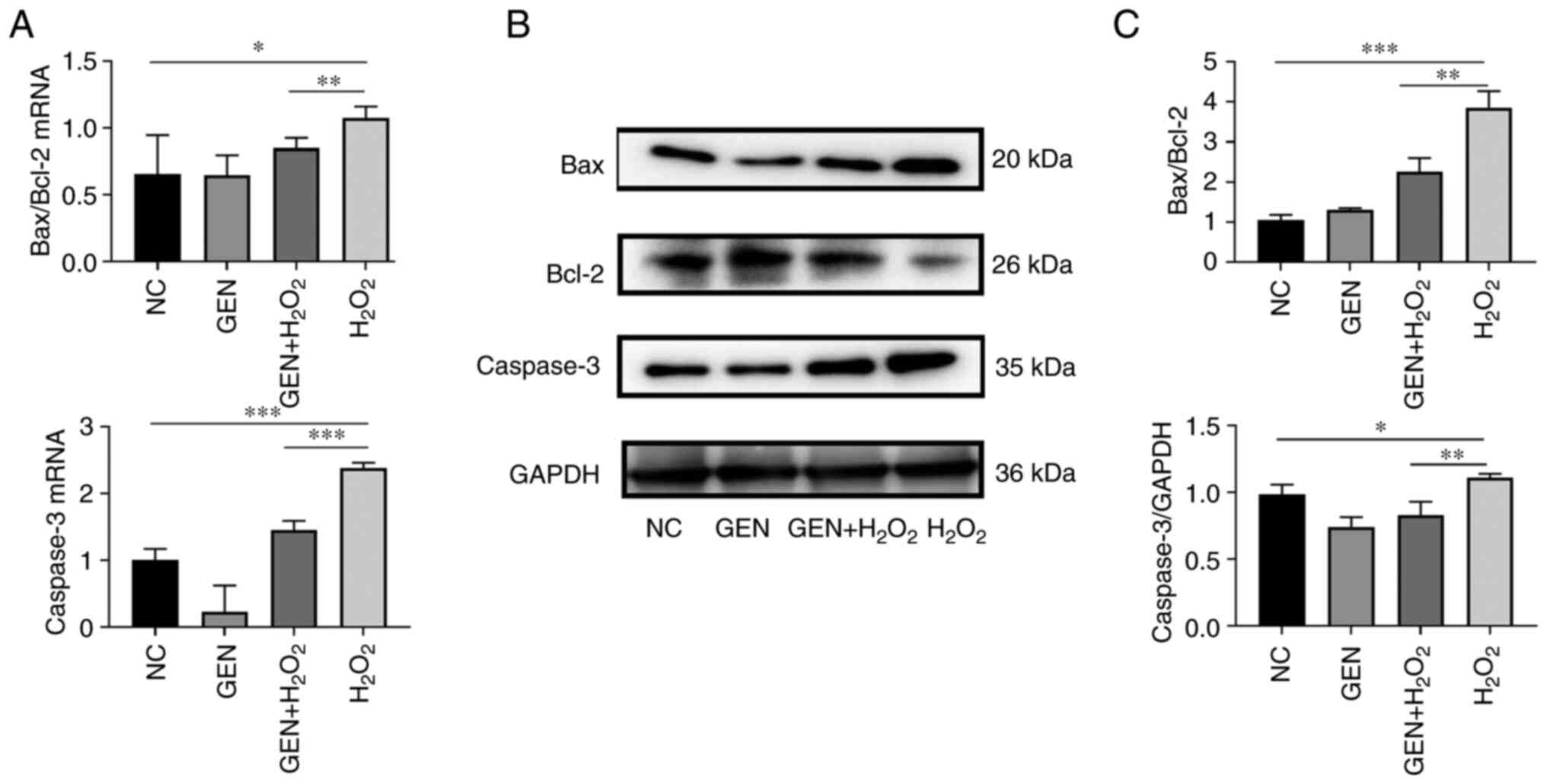

Effect of GEN on the expression of

apoptosis-related genes

To verify the expression of apoptosis-related genes

after GEN treatment, the expression of Bax, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3

were detected by RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. As

shown in Fig. 6A, compared with

the control group, the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was significantly higher

after H2O2 stress (*P<0.05), which was

decreased after GEN pretreatment (**P<0.01). The expression of

Caspase-3 was also significantly higher in the

H2O2 group (***P<0.001), and lower in the

GEN pretreatment group (***P<0.001; Fig. 6B and C. Compared with the control

group, the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 (***P<0.001) and the protein

expression of Caspase-3 were significantly higher (*P<0.05) in

the H2O2 group. However, the ratio of

Bax/Bcl-2 was decreased (P<0.01) and the expression of Caspase-3

was also decreased (**P<0.01) after GEN pretreatment.

Discussion

AS is a slowly progressive disease which is the

pathological basis of coronary heart disease (9,18).

Although the progress of clinical treatment has reduced the risk of

cardiovascular events, AS and the complications from AS remain the

leading cause of death worldwide (10). Of note, the injury of endothelial

cells is the most important inducement of AS which is always

exacerbated by endothelial dysfunction caused by oxidative stress,

inflammation and other factors. Thus, inhibiting the oxidative

damage of vascular endothelial cells is an effective way to prevent

the occurrence and development of AS. It has been verified that GEN

can exabit an antioxidant effects in cancer, post-menopausal

syndrome, osteoporosis and a series of cardiovascular diseases

(8,11). In the present study, the results

further demonstrated that GEN reduced the oxidative damage of

HUVECs significantly through the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

Cell viability can directly reflect the survival

status of cultured cells. In the present study, the results

demonstrated that the cell viability was significantly increased

after pretreatment with GEN. This result indicated that GEN inhibit

the injury induced by oxidation stress partly though the increase

of cell viability.

ROS play an important role in pathogen resistance

and cell signaling. However, ROS can also have deleterious effects

after excessive accumulation (19). Previous studies have shown that the

development of AS is closely related to oxidative stress, and

excessive ROS can accelerate the process of AS (20,21).

H2O2 is a common oxidizing agent that always

leads to an increase of intracellular ROS and a decrease in the

viability of numerous different cells (12). The present study further explored

the possible antioxidant effect of GEN. The results of the present

study revealed that GEN pretreatment could attenuate the

intracellular ROS aggregation under H2O2

treatment that is consistent with previous literature (10).

High concentrations of ROS not only cause damage to

macromolecules, including DNA (22), but also induces the opening of

mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore to release more

ROS (23), which subsequently

induce the release of cytochrome C further to cause apoptosis

(24). These apoptotic cells will

promote the development and progression of coronary artery disease

(25). To determine the protective

role of GEN after oxidative injury, Annexin-V/FITC double staining

was used to further detect apoptosis. It was found that GEN

pretreatment could reduce the early and total apoptotic rate of

HUVECs after H2O2 stress. Meanwhile, the

Bcl-2/Bax ratio was increased and the expression of Caspase-3 was

correspondingly decreased in the GEN pretreatment group. It has

been identified that Caspase-3 is the critical caspase that is also

the main effector of the apoptotic program (26). Moreover, apoptosis can be resisted

though increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (such as

Bcl-2) or downregulated expression of pro-apoptotic proteins (such

as Bax) (7). Thus, the results of

the present study further confirmed that GEN could reduce the

apoptosis of HUVECs through decreased expression of Caspase-3 and

increased ratio of Bcl-2/Bax after H2O2

stress.

Moreover, the activity of SOD, GSH and GPx enzymes

was further detected to reveal the effect of GEN on the

anti-oxidative ability of vascular endothelial cells. SOD is an

enzyme that catalyzes the removal of superoxide radicals

(−O2-) and protects the organism from oxidative damage

during physiological aging (27).

GSH also plays a key role in protecting cells from oxidative damage

and toxicity from exogenous electrophiles to maintain redox

homeostasis (28). GPx is another

major member of the antioxidant enzyme family, which catalyzes the

reduction of peroxides by GSH, scavenges free radicals in the body

and thereby reducing the level of ROS. As hypothesized, the

activity of all these three enzymes was increased to some extent

after GEN pretreatment. These results indicated that

H2O2 induces the aggregation of intracellular

ROS accompanied by decreased activity of intracellular antioxidant

system enzymes. However, pretreatment of GEN increased the content

of intracellular antioxidant enzymes, which effectively reduced the

oxidative damage caused by ROS in cells.

Notably, Nrf2 is a critical cytoprotective factor

involved in regulating the expression of antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory and detoxification protein genes (29). Nrf2 also plays an integral role as

a transcription factor in the maintenance of cellular redox

homeostasis and phase II detoxification responses (30,31).

Keap1-Nrf2 pathway regulates the expression of a number of

cytoprotective genes, including the downstream gene HO-1 (32). HO-1 not only acts as an antioxidant

stressor but also regulates a series processes including

inflammation, apoptosis, cell proliferation, fibrosis and

angiogenesis (29). The present

study also revealed that the expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and SOD1 was

reduced after H2O2 stress. However, GEN

pretreatment could reverse the decreased expression of Nrf2, HO-1

and SOD1 significantly. These observations indicated that GEN

inhibit the antioxidation injury through the Nrf2/HO-1/SOD1 related

pathway.

In summary, the data provided in the present study

function as an insight that GEN can exhibit an effective

anti-oxidation role though ameliorating the decrease in cell

viability and antioxidant ability of vascular endothelial cells

after H2O2 stress. Moreover, the involvement

of Nrf2/HO-1/SOD1 related pathway was further verified to be in

H2O2-stessed vascular endothelial cells after

GEN pretreatment which may be clinically relevant. Understanding

the contribution of this molecular network within vascular

endothelial cells may provide new therapeutic approaches for the

treatment of oxidation damage in AS. The limitations of the present

study were the usage of singular cellular model and the lack of

in vivo experiments, which will be followed up by the

authors with an experimental study of an animal model.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 81600026,82070034 and 82173572),

the Hunan Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2021JJ30898) and

the Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (grant

no B202303027804).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

KX and QQ carried out the experiments, analyzed and

interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. YY, LY, XD and KZ

performed the experiments and statistical analysis. QQ, XW and WW

analyzed and interpreted the data, provided the project funding and

revised the manuscript. CL analyzed and interpreted the data,

revised the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and

helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. KX and CL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Libby P: The changing landscape of

atherosclerosis. Nature. 592:524–533. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang W, Liu YN, Yin P, Wang LJ, Liu JM, Qi

JL, You JL, Lin L and Zhou MG: Analysis on factors associated with

the place of death among individuals with cardiovascular diseases

in China, 2018. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 42:1429–1436.

2021.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang W, Huang Q, Zeng Z, Wu J, Zhang Y

and Chen Z: Sirt1 inhibits oxidative stress in vascular endothelial

cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017:75439732017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wu Y, Wang Y and Nabi X: Protective effect

of Ziziphora clinopodioides flavonoids against

H2O2-induced oxidative stress in HUVEC cells.

Biomed Pharmacother. 117:1091562019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hughes GJ, Ryan DJ, Mukherjea R and

Schasteen CS: Protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores

(PDCAAS) for soy protein isolates and concentrate: Criteria for

evaluation. J Agric Food Chem. 59:12707–12712. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li P, Yao LY, Jiang YJ, Wang DD, Wang T,

Wu YP, Li BX and Li XT: Soybean isoflavones protect SH-SY5Y neurons

from atrazine-induced toxicity by activating mitophagy through

stimulation of the BEX2/BNIP3/NIX pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

227:1128862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M,

Wang HG, Lin HK, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B and Reed JC: Tumor

suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in

vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 9:1799–1805. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rahman Mazumder MA and Hongsprabhas P:

Genistein as antioxidant and antibrowning agents in in vivo and in

vitro: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 82:379–392. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhai X, Lin M, Zhang F, Hu Y, Xu X, Li Y,

Liu K, Ma X, Tian X and Yao J: Dietary flavonoid genistein induces

Nrf2 and phase II detoxification gene expression via ERKs and PKC

pathways and protects against oxidative stress in Caco-2 cells. Mol

Nutr Food Res. 57:249–259. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Qian Y, Guan T, Huang M, Cao L, Li Y,

Cheng H, Jin H and Yu D: Neuroprotection by the soy isoflavone,

genistein, via inhibition of mitochondria-dependent apoptosis

pathways and reactive oxygen induced-NF-κB activation in a cerebral

ischemia mouse model. Neurochem Int. 60:759–767. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Qian Y, Cao L, Guan T, Chen L, Xin H, Li

Y, Zheng R and Yu D: Protection by genistein on cortical neurons

against oxidative stress injury via inhibition of NF-kappaB, JNK

and ERK signaling pathway. Pharm Biol. 53:1124–1132. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Park WH: The effect of MAPK inhibitors and

ROS modulators on cell growth and death of

H2O2-treated HeLa cells. Mol Med Rep.

8:557–564. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Song T, Xue Z, Zhang Z, Shen X and Li X:

Pan-BH3 mimetic S1 exhibits broad-spectrum antitumour effects by

cooperation between Bax and Bak. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol.

113:145–151. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhai X, Zhang C, Zhao G, Stoll S, Ren F

and Leng X: Antioxidant capacities of the selenium nanoparticles

stabilized by chitosan. J Nanobiotechnology. 15:42017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang K, Han L, Hong H, Pan J, Liu H and

Luo Y: Purification and identification of novel antioxidant

peptides from silver carp muscle hydrolysate after simulated

gastrointestinal digestion and transepithelial transport. Food

Chem. 342:1282752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu H, Wang H, Qi F, Xia T, Xia Y, Xu JF

and Zhang X: An activatable host-guest conjugate as a nanocarrier

for effective drug release through self-inclusion. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 13:33962–33968. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Messina M: Soy foods, isoflavones, and the

health of postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 100 (Suppl

1):423S–430S. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nathan C and Cunningham-Bussel A: Beyond

oxidative stress: An immunologist's guide to reactive oxygen

species. Nat Rev Immunol. 13:349–361. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen XH, Tan Y, Yu S, Lu L and Deng Y:

Pinitol protects against ox-low-density lipoprotein-induced

endothelial inflammation and monocytes attachment. J Cardiovasc

Pharmacol. 79:368–374. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shan R, Liu N, Yan Y and Liu B: Apoptosis,

autophagy and atherosclerosis: Relationships and the role of Hsp27.

Pharmacol Res. 166:1051692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang S and Lian G: ROS and diseases: Role

in metabolism and energy supply. Mol Cell Biochem. 467:1–12. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zorov DB, Juhaszova M and Sollott SJ:

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS

release. Physiol Rev. 94:909–950. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE,

Didelot C and Kroemer G: Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from

mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 13:1423–1433. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang X, He T, Han S, Zhang X, Sun Y, Xing

Y and Shang H: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in the

regulation of oxidative stress in treating coronary heart disease.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:32314242019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sakahira H, Enari M and Nagata S: Cleavage

of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during

apoptosis. Nature. 391:96–99. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yanase S, Onodera A, Tedesco P, Johnson TE

and Ishii N: SOD-1 deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans alter the

localization of intracellular reactive oxygen species and show

molecular compensation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 64:530–539.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Forman HJ, Zhang H and Rinna A:

Glutathione: Overview of its protective roles, measurement, and

biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 30:1–12. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz

A and Dulak J: Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative

stress response and diseases: An evolutionarily conserved

mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:3221–3247. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N and Biswal S:

Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the

Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 47:89–116.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mitsuishi Y, Motohashi H and Yamamoto M:

The Keap1-Nrf2 system in cancers: Stress response and anabolic

metabolism. Front Oncol. 2:2002012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Alam J, Stewart D, Touchard C, Boinapally

S, Choi AM and Cook JL: Nrf2, a Cap'n'Collar transcription factor,

regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J Biol Chem.

274:26071–26078. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|