Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related

deaths worldwide, accounting for 18% of all cancer deaths.

According to survey data in 2020, the incidence of lung cancer was

second only to breast cancer globally and both morbidity and

mortality rates continue to rise (1,2).

Lung cancer is categorized into two main types: Small cell lung

cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). NSCLC is most

prevalent in the patient population and ~85% of lung cancer

patients have NSCLC (3). The A549

cell line is derived from a primary lung tumor and is one of the

most commonly used in the study of human NSCLC cell lines. In the

face of persistently high incidence and mortality rates, the

medical treatment of lung cancer must progress and more effective

treatment methods need to be developed (4). Traditional lung cancer treatment

methods mainly include surgery and chemotherapy (5). Current therapeutic approaches and

strategies for lung cancer treatment have made progress, such as

nanodrug delivery systems, molecularly targeted therapeutic

systems, photothermal therapeutic strategies and lung cancer

immunotherapy. These approaches have provided new perspectives and

insights into the treatment of lung cancer (6). Unlike traditional cytotoxic drugs,

targeted anti-tumor drugs mainly target components of cell

signaling pathways, such as cycle-regulating proteins, immune

regulatory factors and important proteins or factors involved in

angiogenesis, with relatively high specificity (7,8).

Compared with chemotherapy, targeted therapy is safer and more

controllable (9). For example,

following the application of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) in

EGFR-positive NSCLC, overall survival is significantly increased

(10) and TKI inhibitors exhibit

fewer side effects compared with chemotherapy (11). The development of targeted

anti-tumor drugs has become the key focus of anti-tumor drug

research (12). Therefore, seeking

active ingredients with improved efficacy and lower toxicity in

natural drugs provides novel avenues of research for tumor

treatment.

Rabdoternin E is an ent-kaurane diterpene monomer

compound and is commonly found in plants of the Isodon genus

of the Lamiaceae family. It is reported that kaurene-type

diterpenoids have significant anti-tumor activities (13), however, studies on the

pharmacological activity associated with rabdoternin E have not

been reported in the current literature. Our previous preliminary

study found that rabdoternin E effectively inhibits the

proliferation of lung cancer A549 cells (14). Therefore, the present study further

investigated the inhibitory effect and underlying mechanisms of

rabdoternin E on the proliferation of A549 cells and provide basic

data for the study of the anti-tumor activity of rabdoternin E.

Materials and methods

Preparation of drugs

Rabdoternin E with >98% purity was supplied by

Henan Engineering Research Center of Medicinal and Edible Chinese

Medicine (Zhengzhou, China). Rabdoternin E was initially dissolved

in culture medium (DMEM; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) at a concentration of 500 µM in vitro experiments

and was subsequently diluted to 5, 10 and 15 µM. Rabdoternin E was

dissolved in saline and formulated as a solution for oral

administration in in vivo experiments. The stock solution

concentrations of rabdoternin E in saline for in vivo use

were 0.034, 0.068 and 0.136 mg/ml and the dosage of rabdoternin E

was 0.1 ml/10 g.

Cell culture

The lung cancer cell line A549 was cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 environment. A549 cells were cultured at a maximum

of 10 passages to ensure the integrity of the cell line. A549 cells

and MRC-5 cells were obtained from Professor Chen Suiqing at Henan

University of Chinese Medicine (Zhengzhou, China).

Cell viability assay

The cytotoxicity of rabdoternin E on A549 cells was

measured by a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol 2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium

bromide (MTT; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

assay. In brief, A549 cells (1×104 cells/well) were

seeded into a 96-well culture plate overnight and treated with 5,

10 and 15 µM of rabdoternin E for 24, 48 and 72 h. The cells were

incubated with MTT (5 mg/ml) for 4 h and after which 150 µl DMSO

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to

each well and the cells were gently shaken for 10 min to completely

dissolve the purple crystals. Finally, the absorbance values of

each well were measured at 492 nm using a microplate reader

(Infinite F50; Tecan Group, Ltd.) (15). Cell viability was calculated as the

percentage of viable cells in the A549-treated group vs. the

untreated control.

Clonogenic assay

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates (800

cells/well) and cultured for 24 h. After which, the culture medium

was replaced with medium containing different final concentrations

(0, 5, 10 and 15 µM) of rabdoternin E and incubated (37°C) for

another 24 h. The medium containing the drug was then removed and

replaced with complete culture medium for 10 days, with regular

medium changes during the culture period. After the culture period,

the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 15 min at room temperature and then stained with 1%

crystal violet (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 5 min. Excess staining solution was removed by washing

with PBS and colonies were counted to calculate the cloning

efficiency. The cell population clones were between 0.3–1.0 mm in

size and each clone contained >50 cells.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells (3×105 cells/well) were seeded into

a 6-well culture plate overnight for attachment and treated with 0,

5 10 and 15 µM of rabdoternin E for 24 h, washed twice with cold

PBS and fixed in 70% ethanol at −4°C for 12 h. After washing the

fixed cells with 1 ml PBS and centrifuging (5 min; 85 × g; −4°C),

the supernatant was removed and 100 µl RNase A solution was added

to the cell pellet. The cells were resuspended and incubated at

37°C for 30 min. After which, 400 µl propidium iodide (PI) staining

solution was added and mixed thoroughly. The cells were incubated

in the dark at 4°C for 30 min, filtered through a 200-mesh cell

strainer and finally analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 Plus;

BD Biosciences) (16).

FITC annexin V/PI apoptosis assay

Cells (3×105 cells/well) were seeded onto

a 6-well culture plate overnight for attachment and treated with

rabdoternin E (0, 5, 10 and 15 µmol/l) for 24 h at 37°C with 5%

CO2. Apoptosis assay was performed using the FITC

Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). The cells were washed once with PBS,

trypsinized and resuspended in media. A total of 1×105

cells were centrifuged (5 min; 85 × g; −4°C) and the cell pellets

were washed with PBS, resuspended in 100 µl 1X binding buffer and

then incubated with 3 µl FITC Annexin V and 5 µl PI for 15 min in

the dark. Finally, all samples were analyzed by flow cytometry

analysis using a BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences)

(17).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

assay

Detection of intracellular ROS was performed using

DCEH-DA as a fluorescent probe. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates

at a density of 3×105 cells/well and incubated at 37°C

for 24 h. After treatment with 0, 5, 10 and 15 µM of rabdoternin E

for 24 h, all cells were collected, washed twice with PBS and

resuspended in 1 ml 10 µM DCEH-DA solution (loaded with probe) for

20 min at 37°C. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 500 µl PBS

and analyzed using flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 Plus; BD

Biosciences).

Determination of malondialdehyde (MDA)

and glutathione (GSH) levels

MDA content and GSH activity were determined using

the relevant kits (MDA; cat. no. BC0025; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.; GSH; cat. no. BC1175; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. After A549 cells were administered and treated for 24

h, cells were collected and lyzed by repeatedly placing the cells

in liquid nitrogen for 3–4 times. The lysed cells were centrifuged

(10 min; 8,497 × g; −4°C) and the supernatant was collected. The

MDA and GSH contents of the samples were then determined according

to the instructions of the two kits.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from cells and tumor

tissue, respectively. (RIPA lysate; cat. no. G2002; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). Protein concentration was

assessed using a BCA assay kit (cat. no. G2026; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis was applied to separate proteins and the proteins

were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The mass of

protein per lane was 20 µg and the percentage of gel was 5%. After

which, the membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at

37°C and incubated at 4°C overnight with the following primary

antibodies: Bax, SCL7A11, glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), Bcl-2,

Ki67, Cyclin A2, CDK2 and GAPDH (cat. nos. GB114122, 1:1,000;

DF12509, 1:1,000; DF12509, 1:1,000; GB113375, 1:1,000; GB11030,

1:1,000; GB11030, 1:1,000; GB112129, 1:1,000; GB15002, 1:2,000;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). Finally, the membranes were

incubated with a goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody

(cat. nos. GB23301 and GB23303; 1:5,000; CST Biological Reagents

Co., Ltd.) for 2 h at room temperature. All bands were visualized

by chemiluminescence. AlphaEaseFC 4.0 (Alpha Innotech) and Adobe

PhotoShop 2024 (Adobe Systems, Inc.) were used for densitometry

(18).

Lewis lung carcinoma mouse model

A total of 30 male BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old;

18–20 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal

Technology Co., Ltd. They were given free access to food and water

and kept in an SPF environment. The temperature in the environment

was 24±2°C, the relative humidity was 60%, and 12-h light/dark

cycle. All experimental procedures were accomplished complying with

the guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Henan

University of Chinese Medicine and approved by The Animal

Experiments and Experimental Animal Management Committee from The

Henan University of Chinese Medicine (Zhengzhou, China; approval

no. DWLL202207009). BALB/c mice were injected subcutaneously with a

total of 2×106 A549 cells in the left forelimb. At 4

days after A549 inoculation, the mice were randomly divided into

five groups (n=6/per group) including: i) Model group; ii) positive

group (3 mg/kg cisplatin); iii) low rabdoternin E group (0.34

mg/kg); iv) medium rabdoternin E group (0.68 mg/kg); and v) high

rabdoternin E group (1.36 mg/kg). Drug intervention groups were

administered cisplatin or rabdoternin E by gavage for 15

consecutive days and the model group received the saline

equivalent. The mice were weighed and tumor volume was measured

with calipers every 3 days to track tumor growth and calculated

according to the following formula: 0.5× length ×

width2. The mice were sacrificed under deep anesthesia

and tumor tissue was excised. No drugs were used to sacrifice the

mice in this study. At the end of the experiment, Mice were

anesthetized with 40 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium solution by

intraperitoneal injection, blood was collected under anesthesia

through heart puncture and then the mice were sacrificed by

cervical dislocation and the collected samples were subsequently

preserved at −80°C for future use.

Histological analysis

Mouse tumor tissues were dissected and removed,

washed in saline, weighed and recorded, and then fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature. Residual fixative on

the samples was rinsed with running water, and then the fixed

tissues were dehydrated in a gradient with ethanol at

concentrations of 70, 80, 90, 95 and 100% in turn, with each

concentration of ethanol solution being immersed for 2 h at room

temperature. After the tissues were dehydrated, the tissues were

placed in xylene I solution and xylene II solution and xylene II

solution, respectively, for 15 min at room temperature, in turn.

After tissue dehydration, the tissues were sequentially immersed in

xylene I solution (ethanol:xylene=1:1), xylene II solution

(ethanol:xylene=1:2) and xylene solution for 15 min at room

temperature. Then the tumor tissues were sequentially placed in

solution I (paraffin:xylene=1:1) solution II (paraffin:xylene=2:1)

and paraffin for 1.5 h at room temperature to complete the wax

infiltration. The embedded paraffin tissue was cut into sections of

3 µm thickness, transferred to slides heated at 60°C for 30 min and

stored at room temperature. Sections were placed into a staining

cylinder and stained with hematoxylin staining solution for 10 min

at room temperature. The section was removed and washed until no

further dye washed out. The cells were differentiated with 1%

hydrochloric ethanol differentiation solution for 3 sec, followed

by rinsing with water for 5 min. Then, the sections were stained

with eosin for 5 min at room temperature, followed by immersion in

water for 2 min. The sections were successively dehydrated with 85

and 95% ethanol for 2 min at room temperature. Finally, the slices

were placed in anhydrous ethanol for 5 min and placed in xylene for

5 min at room temperature. After drying the xylene, neutral resin

was added to the front side to seal the sections. The typical

histopathological changes of the tissues were observed under a

light microscope (Eclipse Ci; Nikon Corporation) following the

staining with an H&E staining kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd., China).

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Student's t-test was used to compare the differences

between two groups and one-way analysis of variance was used to

analyze differences among three or more groups, followed by Tukey's

post hoc analyses for between-group comparisons. Statistical

analysis was performed using the SPSS 26.0 statistical package (IBM

Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Rabdoternin E significantly inhibited

the proliferation of A549 cells in vitro

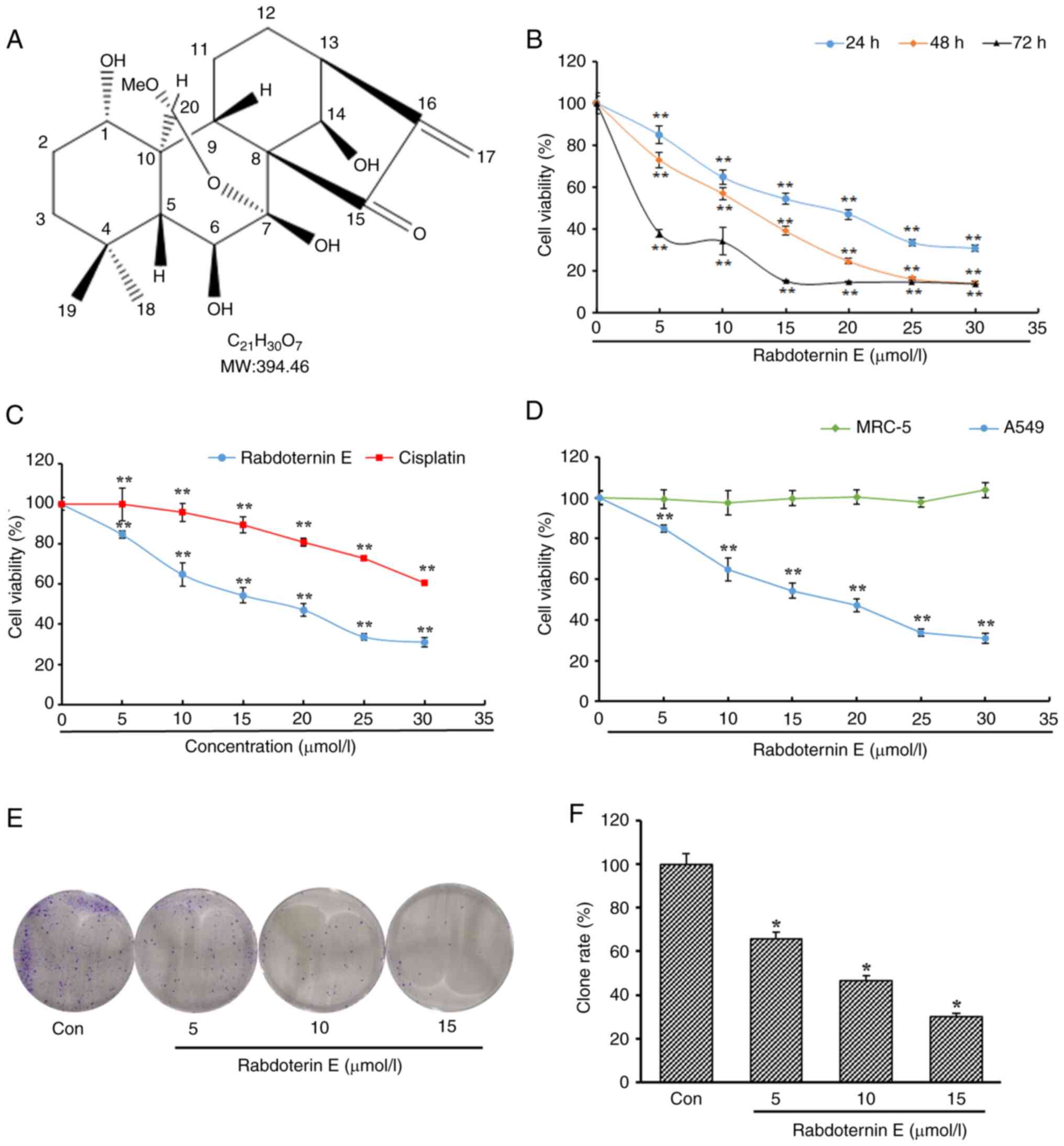

Rabdoternin E is an ent-kaurane diterpene monomer

compound (Fig. 1A). The MTT method

was used to detect the effects of rabdoternin E at different

concentrations on the proliferation of A549 cells. The

proliferation of A549 cells was significantly inhibited by

rabdoternin E intervention (Fig.

1B). Rabdoternin E inhibited A549 cell proliferation jto a

greater degree than cisplatin (positive control) during the 24-h

period with the IC50 of rabdoternin E and cisplatin

against A549 cells 16.45 and 39.52 µM, respectively (Fig. 1C). In order to verify whether

rabdoternin E has cytotoxicity on normal lung cells at tested

concentrations for 24 h, the human embryonic lung fibroblast cell

line MRC-5 was selected for cytotoxicity tests. The rabdoternin E

had no toxic effect on MRC-5 cells at the tested concentrations

(Fig. 1D). To further examine the

inhibition of rabdoternin E on the proliferation of A549 cells, a

clone formation assay was used to investigate the results. The

number of cell clones significantly declined in a dose-dependent

manner (Fig. 1E and F), which

macroscopically confirms that rabdoternin E can significantly

inhibit the proliferation of A549 cells.

Rabdoternin E can promote S phase

arrest and induce apoptosis in A549 cells

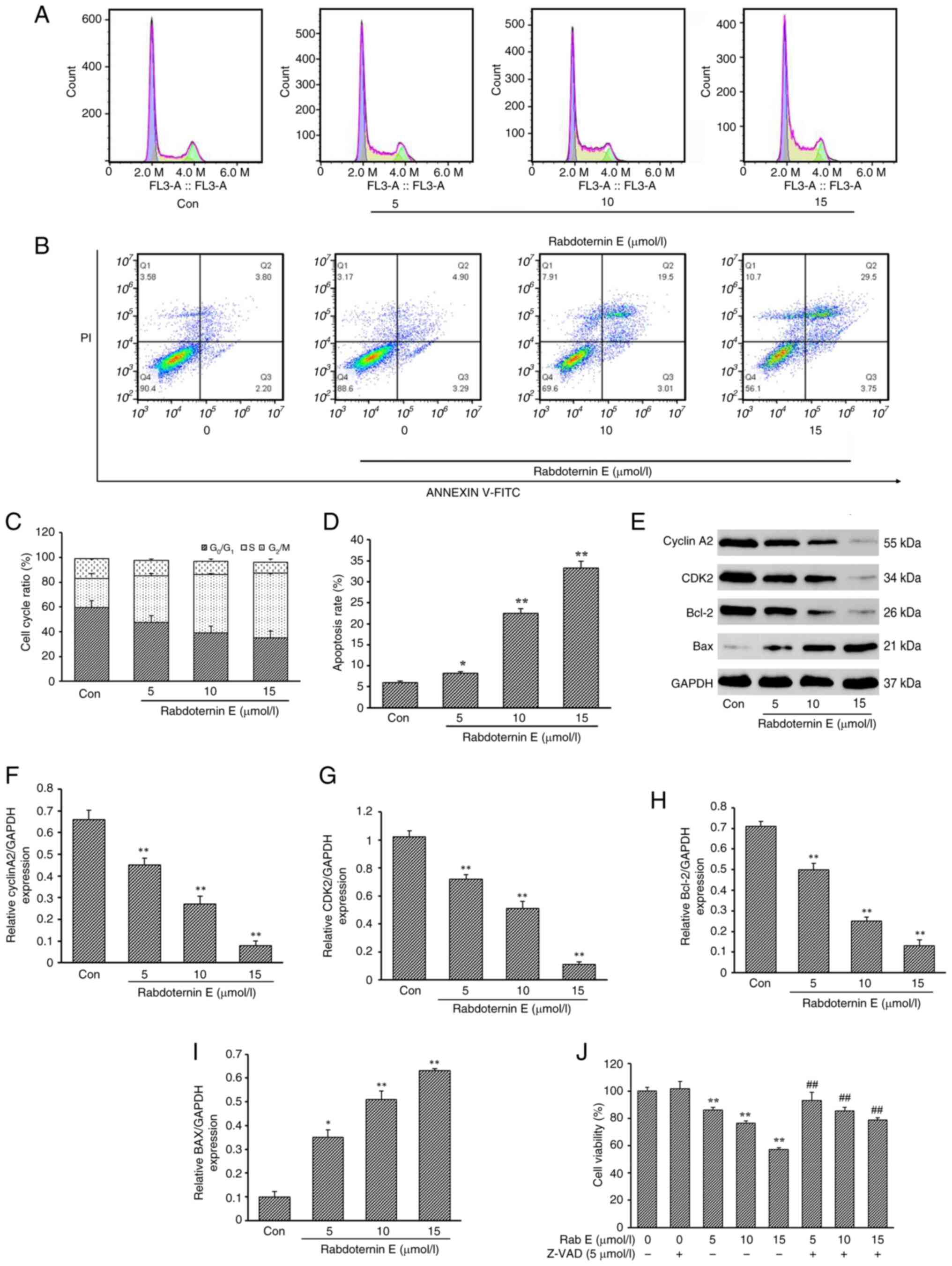

Cell cycle progression is closely related to cell

proliferation and complete and orderly cycle progression is the key

to cell growth and proliferation (19,20).

Compared with the control (Con) group, the proportion of cells in

the S-phase in the rabdoternin E group significantly increased in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and

C). When the dose of rabdoternin E reached 15 µM, the

proportion of cells in the S phase reached 52.2%. The apoptosis

rates in the Con group and rabdoternin E group at concentrations of

5, 10 and 15 µM for 24 h were 6.00, 8.19, 22.51 and 33.25%,

respectively (Fig. 2B and D). The

apoptosis rate in all tested groups was higher than that in the Con

group (P<0.05 or P<0.01). As shown in Fig. 2E-I, Bax and Bcl-2 were

dose-dependently up- and downregulated, respectively and the

Bax/Bcl-2 ratio increased. Moreover, the expression of S-phase

related proteins CDK2 and Cyclin A2 decreased significantly with

the increase of the rabdoternin E concentration. Finally,

rabdoternin E and the apoptosis inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (10 µM) were

co-cultured for 24 h. Z-VAD-FMK reversed the cytotoxicity of

rabdoternin E on A549 cells by ~10% (P<0.05 or P<0.01),

indicating that rabdoternin E induces apoptosis in A549 cells

(Fig. 2J). However, apoptosis is

not the only cause of drug-induced cell death and the effects of

rabdoternin E may be caused by other forms of cell death (21,22).

Rabdoternin E induces ferroptosis in

A549 cells

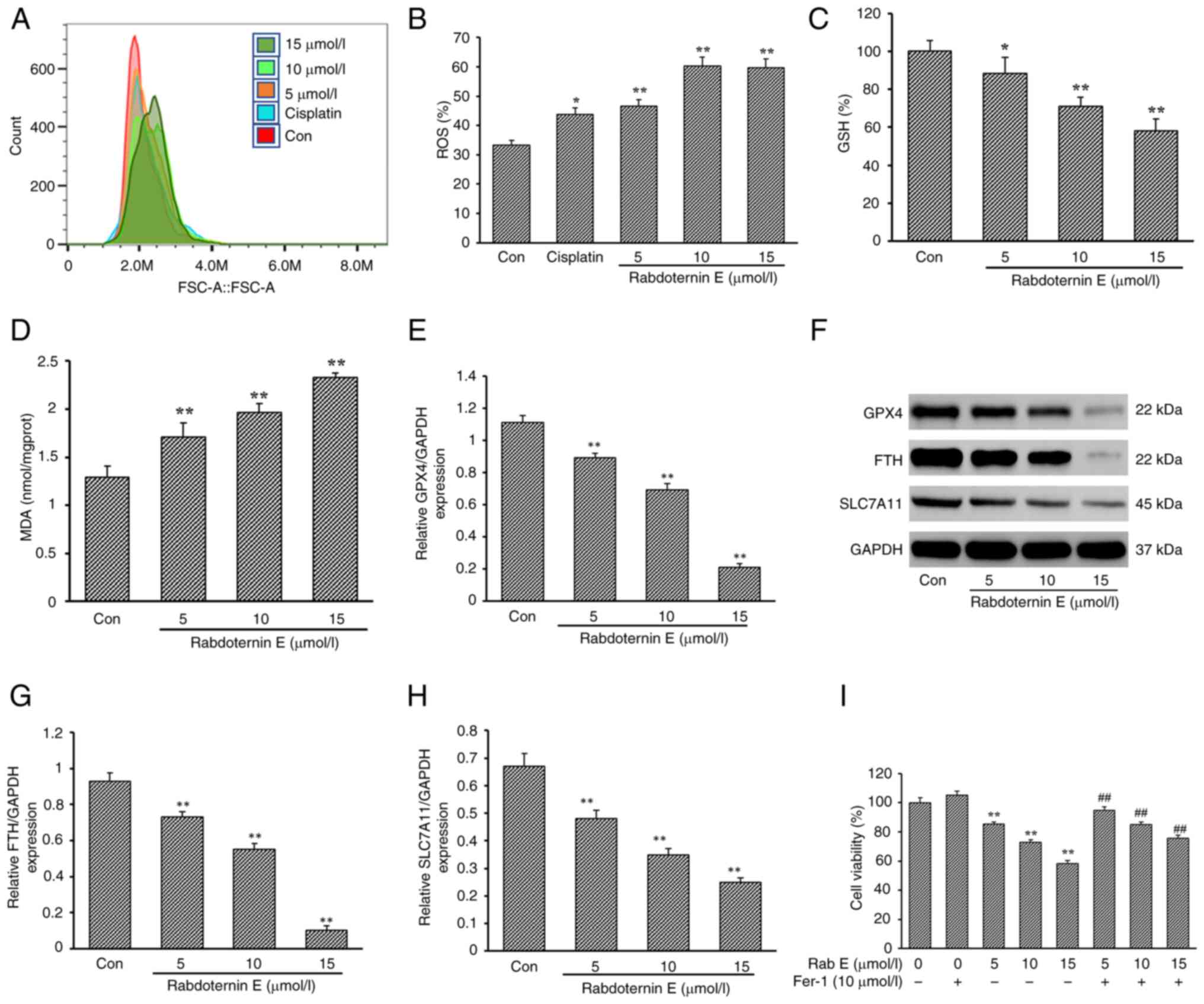

In the process of cancer treatment, drug stimulation

can increase the level of ROS expression, which in turn induces

apoptosis and serves to inhibit the proliferation and spread of

cancer cells (23,24). Meanwhile, the accumulation of ROS

can induce the occurrence of intracellular ferroptosis (25,26).

In the present study, the level of ROS following rabdoternin E

treatment significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 3A and B). A previous

studies showed that ROS accumulation disrupts GSH/GSSH homeostasis,

causing GSH depletion, inducing lipid peroxidation and leading to

the occurrence of ferroptosis (27,28).

Combined with the fact that the apoptosis inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK and

rabdoternin E co-culture did not completely reverse the

proliferation inhibitory effect of rabdoternin E on A549 cells,

changes in GSH and MDA (indicators associated with ferroptosis)

levels after 24 h of rabdoternin E treatment were examined.

Rabdoternin E caused intracellular GSH depletion and MDA

accumulation in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05 or P<0.01,

respectively; Fig. 3C and D),

indicating the occurrence of ferroptosis in cells.

| Figure 3.Effect of Rab E on ferroptosis of

A549 cells. (A) Effects of different concentrations (5, 10 and 15

µM) of Rab E on intracellular ROS levels in A549 cells and (B)

quantitative analysis. Effect of Rab E treatment for 24 h on the

expression of (C) GSH and (D) MDA as indicators associated with

ferroptosis. (E) Protein expression of GPX4, FTH and SLC7A11 in

A549 cells treated with Rab E. (F-H) Effect of Rab E on the protein

expression of (F) GPX4, (G) FTH and (H) SLC7A11 in A549 cells. (I)

Co-culture using ferroptosis-inhibiting Fer-1 and Rab E

significantly reversed cell viability in A549 cells.

(x–±s; n=6) *P<0.05, **P<0.01, vs. Con group;

##P<0.01, vs. Fer-1 group with ferroptosis inhibitor

only. ROS, reactive oxygen species; GSH, glutathione; MDA,

malondialdehyde; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase; FTH, ferritin heavy;

SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member 11; Rab E, rabdoternin E;

Fer-1, ferrostatin-1; Con, control. |

Compared with the Con group, the expression of

ferroptosis marker proteins including solute carrier family 7

member 11 (SLC7A11), GPX4 and ferritin heavy (FTH) decreased in a

dose-dependent manner after rabdoternin E treatment for 24 h

(Fig. 3E-H). Furthermore, the

co-culture of rabdoternin E and a ferroptosis inhibitor

ferrostatin-1 significantly reversed the inhibitory effect of

rabdoternin E on A549 cells, suggesting that rabdoternin E induced

ferroptosis in A549 cells (Fig.

3I).

Effect of rabdoternin E on the

ROS-dependent p38 MAPK/JNK pathway

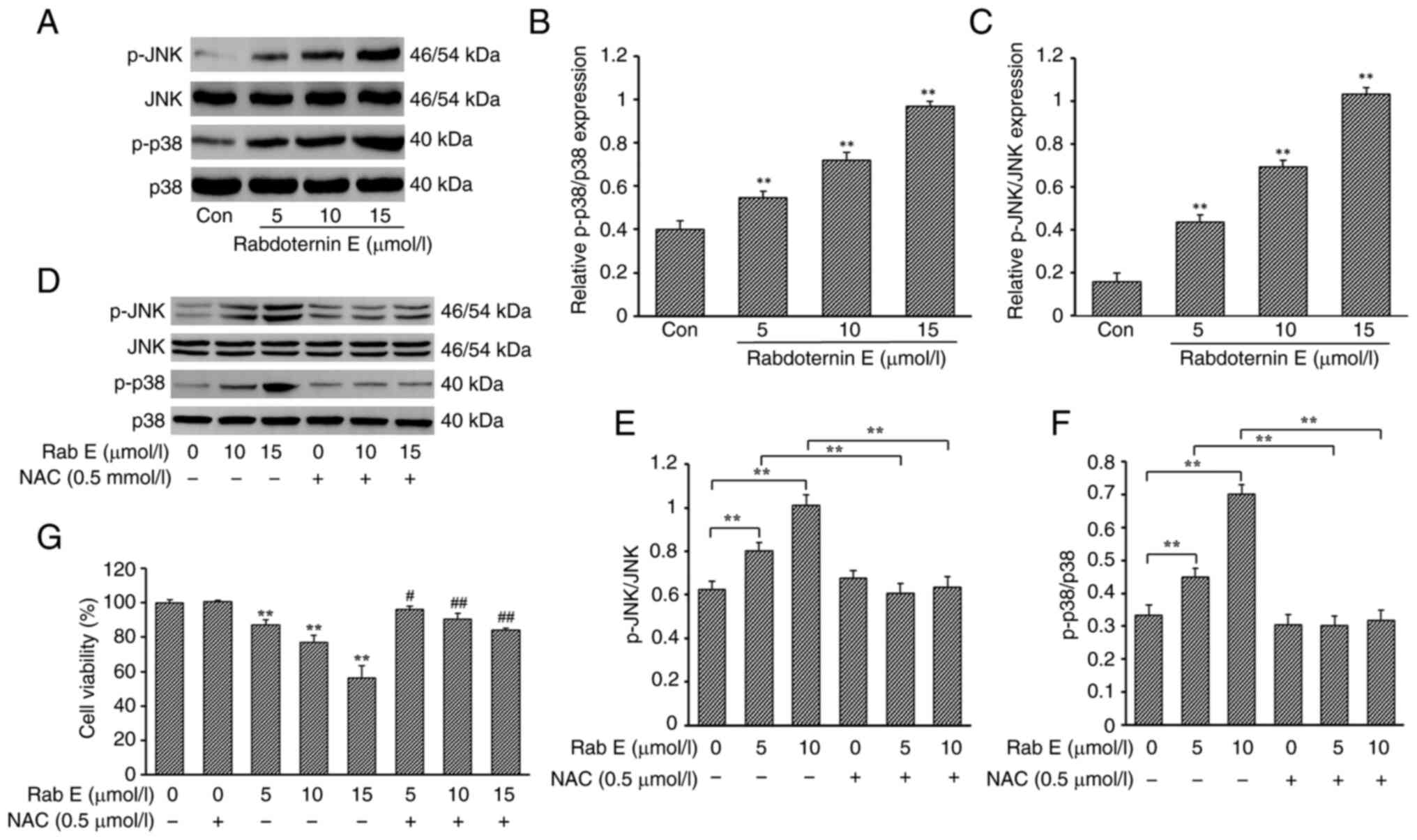

To verify whether rabdoternin E regulates apoptosis

and ferroptosis in A549 cells through the p38 MAPK/JNK pathway, the

expression of phosphorylated p38 MAPK and JNK in A549 cells

following rabdoternin E treatment was examined. The phosphorylation

levels of p38 MAPK and JNK increased in a dose-dependent manner,

indicating that rabdoternin E could effectively regulate the

transactivation of the p38 MAPK/JNK signaling pathway in A549 cells

(Fig. 4A-C). The phosphorylation

levels of p38 MAPK and JNK in cells by co-cultured experiments with

the ROS inhibitor N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and rabdoternin E were

examined. NAC treatment effectively inhibited rabdoternin

E-stimulated p38 MAPK and JNK activation (P<0.05 or P<0.01;

Fig. 4D-F). The addition of NAC

effectively reversed the cytotoxicity of rabdoternin E on A549 and

the degree of reversal was significantly stronger than the effects

of the apoptosis inhibitor or ferroptosis inhibitor (Fig. 4G). Therefore, the results indicated

that the ROS-dependent activation of the p38 MAPK/JNK pathway is

associated with rabdoternin E-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis in

A549 cells.

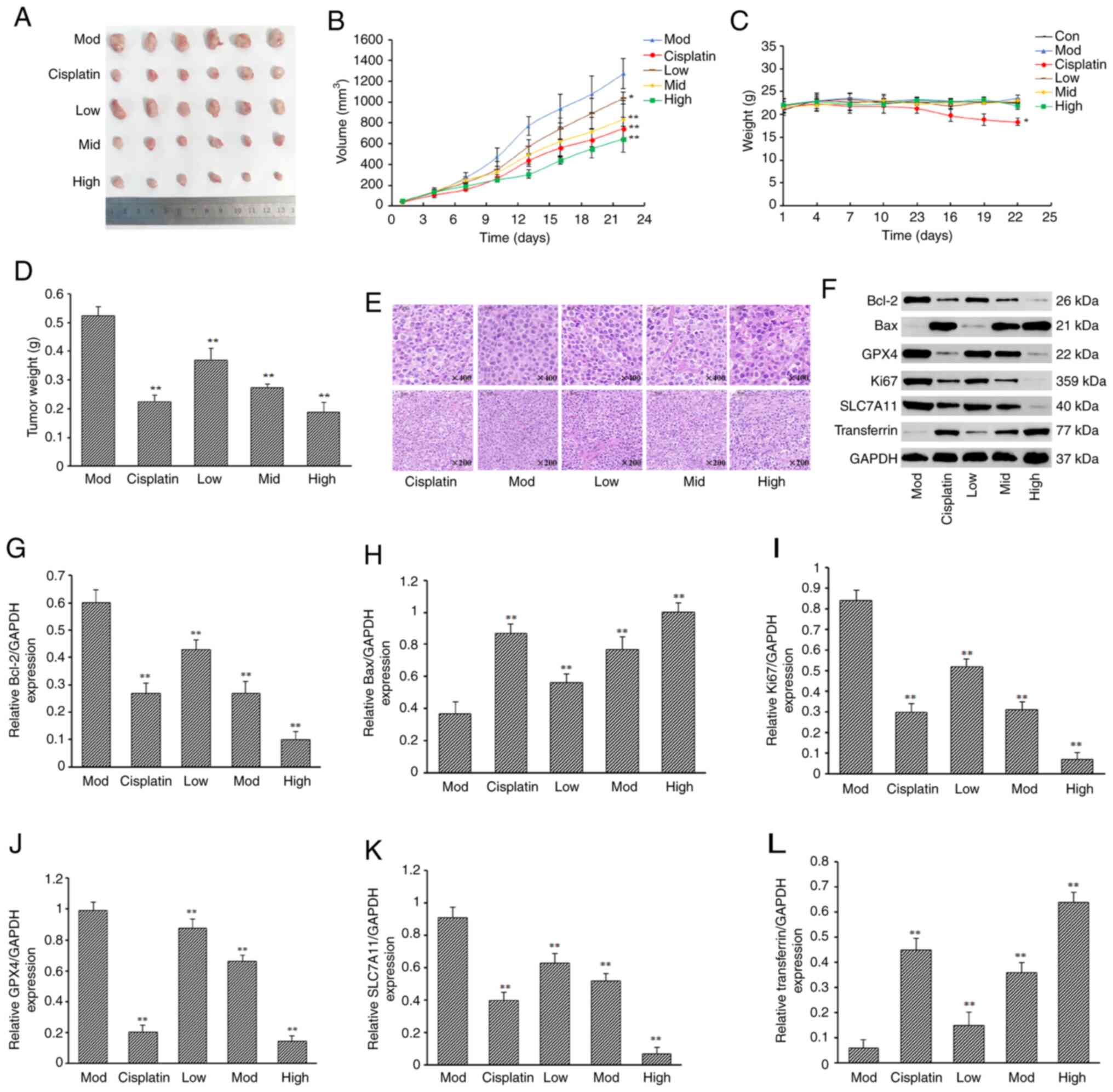

Rabdoternin E inhibits tumor growth

and induces tumor cell death in vivo

To verify the anti-tumor effect of rabdoternin E

in vivo using a Lewis lung carcinoma mouse model, BALB/c

mice were treated with rabdoternin E for 21 days (Fig. 5). The tumor volume and mass in the

rabdoternin E group at all doses was significantly reduced compared

with the model group of BALB/c nude mice and those of the high and

middle dosage rabdoternin E group were smaller compared with the

cisplatin group (Fig. 6A, B and

D). Moreover, all tested doses of rabdoternin E did not

significantly affect the body weight of BALB/c nude mice,

indicating that rabdoternin E had no significant toxic side effects

in the mice, but the positive dose group showed the greatest change

in body weight, with a 14.82% decrease in body weight from the

beginning of the experiment to the end of the experiment (Fig. 6C). H&E staining showed that the

tumor cells were regularly, neatly and tightly packed in the model

group, while those in the rabdoternin E groups were disorganized

with large cell gaps, severely vacuolated and the number

significantly reduced, suggesting rabdoternin E significantly

inhibited the proliferation of A549 cell (Fig. 6E). rabdoternin E treatment

significantly decreased the expressions of Bcl-2, Ki67, GPX4 and

SLC7A11 (P<0.01) and increased those of Bax and transferrin in

the tumor tissues (Fig. 6F-L),

indicating that rabdoternin E induces apoptosis and iron death via

ROS-dependent p38 MAPK/JNK pathway activation.

| Figure 6.Effect of rabdoternin E on the

proliferation of subcutaneous transplanted tumors in nude mice with

human lung cancer A549 cells. Plots of (A) tumor appearance, (B)

tumor size and (C) body weight of mice in each group. (D) Tumor

weight. (E) H&E staining results of tumor tissues in each

group. Magnification, ×200 and ×400. (F) Protein bands of each

experimental group. Protein expression of (G) Bcl-2, (H) Bax, (I)

Ki67, (J) GPX4, (K) SLC7A11 and (L) transferrin of each

experimental group. (x–±s; n=6) *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

vs. Mod group. GPX4, glutathione peroxidase; SLC7A11, solute

carrier family 7 member 11; Mod, model group. |

Discussion

At present, there are no literature reports on the

mechanisms of anti-tumor action of rabdoternin E. In the present

study, it was found that rabdoternin E induced apoptosis and

ferroptosis in A549 cells through the ROS/p38MAPK/JNK signaling

pathway. The MTT experiments demonstrated that rabdoternin E

significantly inhibited the proliferation of A549 cells with an

IC50 value of 16.4 µM and was not cytotoxic to normal

lung cells (MRC-5). Numerous ent-Kaurane diterpenoids have been

reported to have marked anti-lung cancer activity (14). For example, rabdoternin F and

Isorosthin O significantly inhibit A549 cell proliferation with

IC50 values of 18.1 and 18.8 µM, respectively, thus

indicating that rabdoternin E has greater inhibitory activity

against A549 cells. However, numerous ent-kaurane diterpenoids

including rabdoternin E, rabdoternin F and Isorosthin O have weak

inhibitory activity against the proliferation of SMMC7721 and SW480

cells (14).

In order to explore the mechanisms behind this

action, apoptosis and cell cycle-related analyses were conducted on

rabdoternin E-treated cells. The findings of the present study

revealed that rabdoternin E arrests the cell cycle in the S phase

and induces apoptosis. In addition, it was noted that ROS levels

increased in rabdoternin E-treated cells. It is well established

that ROS accumulation is often associated with disturbances in

cellular oxidative disorders (29,30).

Subsequent co-culture studies with rabdoternin E and Z-VAD-FMK (an

apoptosis inhibitor) showed a partial reversal of the cytotoxicity

of rabdoternin E to A549 cells. Therefore, it was hypothesized that

in addition to inducing apoptosis, rabdoternin E may contribute to

cell death through oxidative metabolic disorders. The occurrence of

ferroptosis primarily arises from intracellular GSH depletion and

reduced activity of GPX4, resulting in impaired metabolism of lipid

peroxides through GPX4-catalyzed reduction reactions (31,32).

Simultaneously, the Fenton reaction oxidizes lipids and generates a

substantial amount of ROS, thereby accelerating cell death

(33). Previous studies have

demonstrated that ferroptosis is strongly linked with the

regulation and pathophysiological processes underlying tumors,

nervous system disorders, kidney injury and hematologic diseases

(34–37).

Rabdoternin E significantly decreased the GSH

content and increased the MDA content in cells. Moreover,

ferrostatin-1 (a ferroptosis inhibitor) effectively reduced the

inhibitory effect of rabdoternin E on A549 cells. These findings

strongly suggested that rabdoternin E induced ferroptosis.

Additionally, it was found that rabdoternin E markedly

downregulated the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 in cells,

indicating it regulated ferroptosis through modulating the

SLC7A11/GPX4 axis. SLC7A11, as an important regulator of

ferroptosis sequestration, plays a crucial role in various

regulatory processes such as tumorigenesis, proliferation,

metastasis, prognosis and chemotherapy resistance (38,39).

Studies have demonstrated that ROS possess the

ability to facilitate signaling pathways in tumor cells and induce

oxidative stress, ultimately leading to cellular apoptosis.

Consequently, ROS has emerged as a promising target for potential

cancer therapies (40,41). The MAPK signal transduction pathway

plays a crucial role in various physiological processes and

oxidative stress (42) and the

activation of MAPK regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis,

invasion and metastasis in numerous tumor cells (43,44).

Among the MAPK signaling pathways, p38 MAPK and JNK are important

downstream effectors of ROS (45,46).

Excessive ROS can activate the downstream p38 MAPK/JNK pathway,

leading to increased expression levels of proapoptotic proteins and

induction of apoptosis (47).

Additionally, the MAPK signaling pathways are involved in

regulating ferroptosis (48).

The object of the present study was to investigate

the regulatory effects of rabdoternin E on apoptosis and

ferroptosis in A549 cells through the ROS-mediated p38 MAPK/JNK

pathway (Fig. 7). It was also

found that the phosphorylation levels of p38 MAPK and JNK increased

dose-dependently following rabdoternin E treatment. Notably,

co-treatment experiments with NAC and rabdoternin E demonstrated

that the phosphorylation levels of p38 MAPK and JNK in A549 cells

and the cytotoxicity induced by rabdoternin E were markedly

reduced. The present study indicated that rabdoternin E induces

intracellular accumulation of ROS, which not only activates

downstream effectors such as p38 MAPK and JNK that promote

apoptosis and ferroptosis, but also leads to lipid peroxide

accumulation in cells, further inducing iron-dependent cell

death.

In the in vivo animal experiments, a potent

inhibitory effect of rabdoternin E on tumor growth activity was

observed. Compared with the control group, rabdoternin E

significantly slowed down the growth rate of tumors in mice,

resulting in smaller tumor volume and mass. Notably, the mice in

the administered group at the medium and high doses of rabdoternin

E had a smaller tumor volume and mass than the cisplatin group,

indicating that rabdoternin E also has strong tumor growth

inhibitory activity in vivo. Moreover, the body weight of

mice in the rabdoternin E groups were not adversely affected.

However, over the course of the present study, the body weight of

the mice in the cisplatin group significantly decreased. Western

blotting results showed that the expression content of Ki67 protein

decreased with the increase of administered dose and the weakening

of Ki67 protein expression implied the decrease of tumor

proliferation ability. At the same time, it was found that the

apoptosis-related Bax/Bcl-2 protein expression ratio increased.

Ultimately, they together promote apoptosis of tumor cells.

Meanwhile, western blotting of tumor tissues

revealed that the expression levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4 were

significantly reduced in tissues after rabdoternin E administration

compared to controls. Therefore, it was concluded that rabdoternin

E-induced downregulation of SLC7A11 and GPX4 plays a critical role

in regulating ferroptosis in A549 cells.

To conclude, in the present study rabdoternin E

effectively inhibited A549 cell proliferation in vitro

through induction of the apoptosis and ferroptosis pathways.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the High-Level Talents

International Training project of Henan Province (grant no.

2021-72) and Major Science and Technology Programs in Henan

Province (grant no. 221100310400).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JJ, JN and TG designed the experiments. JJ, JN and

YS performed most of the data analysis and animal and cell

experiments. XC, HW, XW and JH collected and analyzed the data. JJ

and JN wrote the manuscript. YS revised the manuscript. TG and YS

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experiments on animals were approved by the

Subcommittee on Henan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine

Animal Experiment Center (approval no. DWLL202207009).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Li C, Lei S, Ding L, Xu Y, Wu X, Wang H,

Zhang Z, Gao T, Zhang Y and Li L: Global burden and trends of lung

cancer incidence and mortality. Chin Med J (Engl). 136:1583–1590.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Huang J, Deng Y, TinM S, Lok V, Ngai CH,

Zhang L, Lucero-Prisno DE III, Xu W, Zheng ZJ, Elcarte E, et al:

Distribution, risk factors, and temporal trends for lung cancer

incidence and mortality: A global analysis. Chest. 161:1101–1111.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tandberg DJ, Tong BC, Ackerson BG and

Kelsey CR: Surgery versus stereotactic body radiation therapy for

stage I non-small cell lung cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer.

124:667–678. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

LeeC S, Shu CC, Chen YC, Liao KM and Ho

CH: Tuberculosis treatment incompletion in patients with lung

cancer: Occurrence and predictors. Int J Infect Dis. 113:200–206.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tartour E and Zitvogel L: Lung cancer:

Potential targets for immunotherapy. Lancet Respir Med. 1:551–563.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li Y, Yan B and He S: Advances and

challenges in the treatment of lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother.

169:1158912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu S, Bishop WR and Liu M: Differential

effects of cell cycle regulatory protein p21(WAF1/Cip1) on

apoptosis and sensitivity to cancer chemotherapy. Drug Resist

Updat. 6:183–195. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chin EN, Sulpizio A and Lairson LL:

Targeting STING to promote antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol.

33:189–203. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pérez-Herrero E and Fernández-Medarde A:

Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: Drug nanocarriers, the

future of chemotherapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 93:52–79. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jurisic V, Vukovic V, Obradovic J,

Gulyaeva LF, Kushlinskii NE and Djordjević N: EGFR polymorphism and

survival of NSCLC patients treated with TKIs: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Oncol. 2020:19732412020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Obradovic J, Todosijevic J and Jurisic V:

Side effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy in patients with

non-small cell lung cancer and associations with EGFR

polymorphisms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Lett.

25:622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nishimoto A: Effective combinations of

anti-cancer and targeted drugs for pancreatic cancer treatment.

World J Gastroenterol. 28:3637–3643. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fujita E, Nagao Y, Kaneko K, Nakazawa S

and Kuroda H: The antitumor and antibacterial activity of the

Isodon diterpenoids. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 24:2118–2127. 1976.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wei WJ, Zhu B, Si Y, Guo T, Kang J and Dai

L: Cytotoxic ent-kaurane diterpenoids from rabdosia rubescens. Chem

Biodivers. 19:e2022004972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jia XB, Zhang Q, Xu L, Yao WJ and Wei L:

Lotus leaf flavonoids induce apoptosis of human lung cancer A549

cells through the ROS/p38 MAPK pathway. Biol Res. 54:72021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jin X, Sun PP, Hong Y, Yu L and Li S:

Puerarin induces apoptosis in A549 cells. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng

Li Xue Za Zhi. 33:466–469. 2017.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhao C, Qin G, Gao W, Chen J, Liu H, Xi G,

Li T, Wu S and Chen T: Potent proapoptotic actions of

dihydroartemisinin in gemcitabine-resistant A549 cells. Cell

Signal. 26:2223–2233. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhou T, Qin R, Shi S, Zhang H, Niu C, Ju G

and Miao S: DTYMK promote hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation by

regulating cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 20:1681–1691. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Oredsson SM: Polyamine dependence of

normal cell-cycle progression. Biochem Soc Trans. 31:366–370. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Guarracino MR, Xanthopoulos P, Pyrgiotakis

G, Tomaino V, Moudgil BM and Pardalos PM: Classification of cancer

cell death with spectral dimensionality reduction and generalized

eigenvalues. Artif Intell Med. 53:119–125. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Efimova I, Catanzaro E, Van der Meeren L,

Turubanova VD, Hammad H, Mishchenko TA, Vedunova MV, Fimognari C,

Bachert C, Coppieters F, et al: Vaccination with early ferroptotic

cancer cells induces efficient antitumor immunity. J Immunother

Cancer. 8:e0013692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Martinvalet D: ROS signaling during

granzyme B-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell Oncol. 2:e9926392015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Al-Khayal K, Alafeefy A, Vaali-Mohammed

MA, Mahmood A, Zubaidi A, Al-Obeed O, Khan Z, Abdulla M and Ahmad

R: Novel derivative of aminobenzenesulfonamide (3c) induces

apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through ROS generation and

inhibits cell migration. BMC Cancer. 17:42017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li Z, Xiao J, Liu M, Cui J, Lian B, Sun Y

and Li C: Notch3 regulates ferroptosis via ROS-induced lipid

peroxidation in NSCLC cells. FEBS Open Bio. 12:1197–1205. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang CX, Chen LH, Zhuang HB, Shi ZS, Chen

ZC, PanJ P and Hong ZS: Auriculasin enhances ROS generation to

regulate colorectal cancer cell apoptosis, ferroptosis, oxeiptosis,

invasion and colony formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

587:99–106. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Son Y, Kim S, Chung HT and Pae HO:

Reactive oxygen species in the activation of MAP kinases. Methods

Enzymol. 528:27–48. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, Zeller M,

Cottin Y and Vergely C: Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: Two

corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:4492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Molavinia S, Dayer D, Khodayar MJ,

Goudarzi G and Salehcheh M: Suspended particulate matter promotes

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells

via TGF-β1-mediated ROS/IL-8/SMAD3 axis. J Environ Sci (China).

141:139–150. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu T, Sun L, Zhang Y, Wang Y and Zheng J:

Imbalanced GSH/ROS and sequential cell death. J Biochem Mol

Toxicol. 36:e229422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

LiF J, Long HZ, Zhou ZW, Luo HY, Xu SG and

Gao LC: System Xc−/GSH/GPX4 axis: An important

antioxidant system for the ferroptosis in drug-resistant solid

tumor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 13:9102922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu Y, Li Y, Li J and Chen W: Ethyl

carbamate triggers ferroptosis in liver through inhibiting GSH

synthesis and suppressing Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol.

53:1023492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Miao Y, Chen Y, Xue F, Liu K, Zhu B, Gao

J, Yin J, Zhang C and Li G: Contribution of ferroptosis and GPX4′s

dual functions to osteoarthritis progression. EBioMedicine.

76:1038472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ma P, Xiao H, Yu C, Liu J, Cheng Z, Song

H, Zhang X, Li C, Wang J, Gu Z and Lin J: Enhanced cisplatin

chemotherapy by iron oxide nanocarrier-mediated generation of

highly toxic reactive oxygen species. Nano Lett. 17:928–937. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nie J, Lin B, Zhou M, Wu L and Zheng T:

Role of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin

Oncol. 144:2329–2337. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jia B, Li J, Song Y and Luo C:

ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis and its potential role in central

nervous system diseases and injuries. Int J Mol Sci. 24:100212023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hou L, Li X, Su C, Chen K and Qu M:

Current status and prospects of research on ischemia-reperfusion

injury and ferroptosis. Front Oncol. 12:9207072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li X, Zou Y, Fu YY, Xing J, Wang KY, Wan

PZ and Zhai XY: A-lipoic acid alleviates folic acid-induced renal

damage through inhibition of ferroptosis. Front Physiol.

12:6805442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li S, Lu Z, Sun R, Guo S, Gao F, Cao B and

Aa J: The role of SLC7A11 in cancer: Friend or foe? Cancers

(Basel). 14:30592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cheng X, Wang Y, Liu L, Lv C, Liu C and Xu

J: SLC7A11, a potential therapeutic target through induced

ferroptosis in colon adenocarcinoma. Front Mol Biosci.

9:8896882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Moloney JN and Cotter TG: ROS signalling

in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 80:50–64. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gerami P, Kim D, Compres EV, Zhang B, Khan

AU, Sunshine JC, Quan VL and Busam K: Clinical, morphologic, and

genomic findings in ROS1 fusion Spitz neoplasms. Mod Pathol.

34:348–357. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lv C, Fu S, Dong Q, Yu Z, Zhang G, Kong C,

Fu C and Zeng Y: PAGE4 promotes prostate cancer cells survive under

oxidative stress through modulating MAPK/JNK/ERK pathway. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 38:242019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Guimarães LM, Coura BP, Gomez RS and Gomes

CC: The molecular pathology of odontogenic tumors: Expanding the

spectrum of MAPK pathway driven tumors. Front Oral Health.

2:7407882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li H, Han G, Li X, Li B, Wu B, Jin H, Wu L

and Wang W: MAPK-RAP1A signaling enriched in hepatocellular

carcinoma is associated with favorable tumor-infiltrating immune

cells and clinical prognosis. Front Oncol. 11:6499802021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pereira L, Igea A, Canovas B, Dolado I and

Nebreda AR: Inhibition of p38 MAPK sensitizes tumour cells to

cisplatin-induced apoptosis mediated by reactive oxygen species and

JNK. EMBO Mol Med. 5:1759–1774. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lu J, Yu M and Li J: PKC-δ promotes

IL-1β-induced apoptosis of rat chondrocytes and via activating JNK

and P38 MAPK pathways. Cartilage. 194760352311814462023.(Epub ahead

of print).

|

|

47

|

Zhao Q, Yu M, Li J, Guo Y, Wang Z, Hu K,

Xu F, Liu Y, Li L, Wan D, et al: GLUD1 inhibits hepatocellular

carcinoma progression via ROS-mediated p38/JNK MAPK pathway

activation and mitochondrial apoptosis. Discov Oncol. 15:82024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang X, Tan X, Zhang J, Wu J and Shi H:

The emerging roles of MAPK-AMPK in ferroptosis regulatory network.

Cell Commun Signal. 21:2002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|