Introduction

Light, the most powerful environmental cue, or

zeitgeber, is indispensable for synchronizing the brain's

endogenous biological rhythms with the 24-h terrestrial day. This

synchronization underpins temporal organization across all levels

of physiology, profoundly influencing sleep architecture, affective

state and metabolic homeostasis (1). While the human retina has been

traditionally conceived as the exclusive domain of image-forming

vision, a paradigm shift has illuminated its central role in

mediating a suite of non-image-forming (NIF) responses to light.

These vital functions, including circadian photoentrainment,

neuroendocrine modulation and pupillary control, are primarily

orchestrated by a unique population of intrinsically photosensitive

retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) (2,3).

These neurons, expressing the blue-light-sensitive photopigment

melanopsin, form a direct conduit to key subcortical brain regions,

most notably the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus,

which serves as the master circadian pacemaker (4).

From an advanced ophthalmic and neuroscience

perspective, the retina is a highly sophisticated interface between

environmental photic information and the central nervous system's

timing machinery (5). Operating in

concert with classical photoreceptors (rods and cones), ipRGCs

detect ambient illuminance and transduce this information into

neural signals that govern the sleep-wake cycle, regulate the

secretion of the chronobiotic hormone melatonin and directly

modulate brain circuits involved in mood (6). Pathological disruption of this

pathway, arising from degenerative ophthalmic diseases, the

physiological process of aging, or the pervasive alteration of our

light environment by modern technology, can precipitate a state of

circadian desynchronization, leading to impaired sleep quality,

affective disorders and a host of other systemic health problems

(7).

A growing body of evidence from complex animal

models and human clinical studies highlights the profound

vulnerability of the NIF system in the context of retinal pathology

(8–10). Diseases such as glaucoma, which

leads to the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells, and

retinal degenerations such as retinitis pigmentosa, can selectively

or disproportionately compromise ipRGC function (11). This damage results in a cascade of

downstream consequences, including circadian arrhythmia, severely

disrupted sleep architecture and mood instability that transcends

the psychological effect of vision loss itself. Conversely, the

precise understanding of these pathways has unlocked novel

therapeutic possibilities. Targeted manipulation of light exposure,

through spectrally-tuned light therapy or advanced spectral

filtering technologies, offers the potential to strategically

modulate retinal input to circadian centers, heralding new

frontiers in both ophthalmic and behavioral medicine (12), The present review synthesized

current, in-depth knowledge of retinal light perception and its

complex implications for circadian biology, sleep and mood, with a

specific focus on the intricate mechanisms and clinical

significance in ophthalmic disorders.

The molecular and cellular mechanisms of

retinal light perception

The retina's capacity to inform the brain about the

presence and quality of environmental light is mediated by a

sophisticated and heterogeneous assembly of photoreceptive and

neuronal cells (13). While the

roles of rods and cones in image formation are well-established, a

deeper understanding of the retina's non-visual functions requires

a detailed examination of the intrinsic photosensitivity of ipRGCs,

their unique molecular machinery and their intricate integration

within the retinal network (14).

The cellular architecture for photoreception

includes not only the classical photoreceptors but also the 1–3% of

retinal ganglion cells that are ipRGCs (15). These cells express the G-protein

coupled receptor photopigment melanopsin and can function as

autonomous light detectors. This intrinsic photosensitivity is

fundamentally different from that of rods and cones (13). Melanopsin phototransduction is a

depolarizing cascade initiated by the activation of a Gq/11-class

G-protein, leading to the engagement of phospholipase Cβ4. This

enzyme hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate into

inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol. The subsequent opening

of specific transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels,

primarily TRPC6 and TRPC7, permits a sustained influx of

Na+ and Ca2+, causing a prolonged membrane

depolarization and a tonic increase in the cell's action potential

firing rate (11). This sustained

response is ideal for encoding ambient irradiance over long

timescales, a critical feature for circadian signaling. A key

feature of melanopsin is its function as a bistable pigment; its

all-trans-retinal chromophore can be photoisomerized back to the

11-cis form by long-wavelength light, allowing for regeneration

within the cell, a stark contrast to the enzymatic recycling

pathway required for rod and cone opsins (16,17).

The ipRGC population is not monolithic. In mammals,

at least six subtypes (M1-M6) have been delineated based on

distinct morphological, molecular and functional characteristics

(13). M1 ipRGCs stratify their

dendrites in the OFF sublamina of the inner plexiform layer (IPL)

and are defined by expression of the transcription factor Brn3b.

They are the principal drivers of photoentrainment, forming the

primary afferents of the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT) to the SCN

(18). M2 and M4 cells stratify in

the ON sublamina of the IPL, co-express the transcription factor

Tbr2 and contribute markedly to the pupillary light reflex via

projections to the olivary pretectal nucleus. M4 cells, in

particular, have large dendritic fields and are also implicated in

contrast sensitivity for conscious vision (4). Other subtypes, such as M5 and M6,

project to a diverse array of over 40 distinct subcortical targets,

including limbic structures such as the amygdala, bed nucleus of

the stria terminalis and lateral habenula, providing a direct

anatomical substrate for light's influence on mood, fear and

motivation. This remarkable projection diversity means that the

retina disseminates parallel streams of photic information to

functionally distinct brain circuits (8).

Crucially, ipRGCs do not operate in isolation. They

are deeply embedded within the retinal circuitry, acting as complex

integrators of both their own intrinsic photoresponse and extrinsic

signals relayed from rods and cones through specific amacrine and

bipolar cell pathways. For example, ipRGCs receive significant

input from ON-cone bipolar cells, allowing them to respond robustly

to daylight. Rod signals are conveyed primarily through AII

amacrine cells and subsequent gap junctions, conferring high

sensitivity to light at night (19). This integration allows ipRGCs to

encode light information across an astonishing 12-log-unit range of

intensities. The spectral sensitivity of this integrated system is

complex, but the intrinsic (15)

response, with its peak sensitivity to blue light ~480 nm, is the

dominant driver of NIF functions such as circadian resetting and

melatonin suppression (20) This

specific wavelength dependency is the biophysical basis for the

potent effects of blue-enriched light from modern sources on human

physiology (21).

Ophthalmic diseases profoundly alter these intricate

mechanisms. In glaucoma, the progressive apoptosis of RGCs includes

the loss of ipRGCs. Studies indicate that different ipRGC subtypes

may have differential vulnerability, potentially explaining the

specific patterns of NIF deficits observed in patients, such as

impaired pupillary responses and severe sleep disturbances. In

retinal degenerations such as retinitis pigmentosa, the loss of

rods and cones functionally ‘unmasks’ the pure melanopsin-based

photosensitivity of surviving ipRGCs (22,23)

While these surviving cells can sustain circadian entrainment, the

absence of rod and cone input severely reduces the overall

sensitivity of the system and eliminates its ability to respond to

rapid light changes, often leading to poorly entrained or

free-running rhythms. These pathologies transform the retina into a

model system for understanding how specific disruptions in photic

signaling pathways lead to systemic neurobehavioral dysfunction

(15). The main cell types and

photopigments involved in NIF light perception are summarized in

Table I.

| Table I.Key cell types and photopigments

involved in non-image-forming light perception. |

Table I.

Key cell types and photopigments

involved in non-image-forming light perception.

| Cell type |

Marker/photopigment | Main function | Projection

target(s) |

|---|

| Rods | Rhodopsin | Low-light vision,

support NIF via ipRGCs | Bipolar cells,

ipRGCs (indirect) |

| Cones | Photopsins | Color, daylight

vision, input to NIF | Bipolar cells,

ipRGCs (indirect) |

| M1 ipRGCs | Melanopsin

(OPN4) | Circadian

photoentrainment | SCN, OPN |

| M2-M6 ipRGCs | Melanopsin

(OPN4) | Pupillary reflex,

mood regulation, etc. | OPN, LHb, mPFC,

other targets |

| Amacrine/Bipolar

cells | Various | Intraretinal signal

integration | ipRGCs |

The intricate relationship between the

retina and circadian rhythms

The process of photoentrainment, the synchronization

of the endogenous circadian clock to the 24-h light/dark cycle, is

governed by a precise neuroanatomical and molecular dialogue

between the retina and the SCN. This section delves into the

detailed mechanisms of this critical interaction, from the specific

neurochemistry of the RHT to the molecular clockwork within SCN

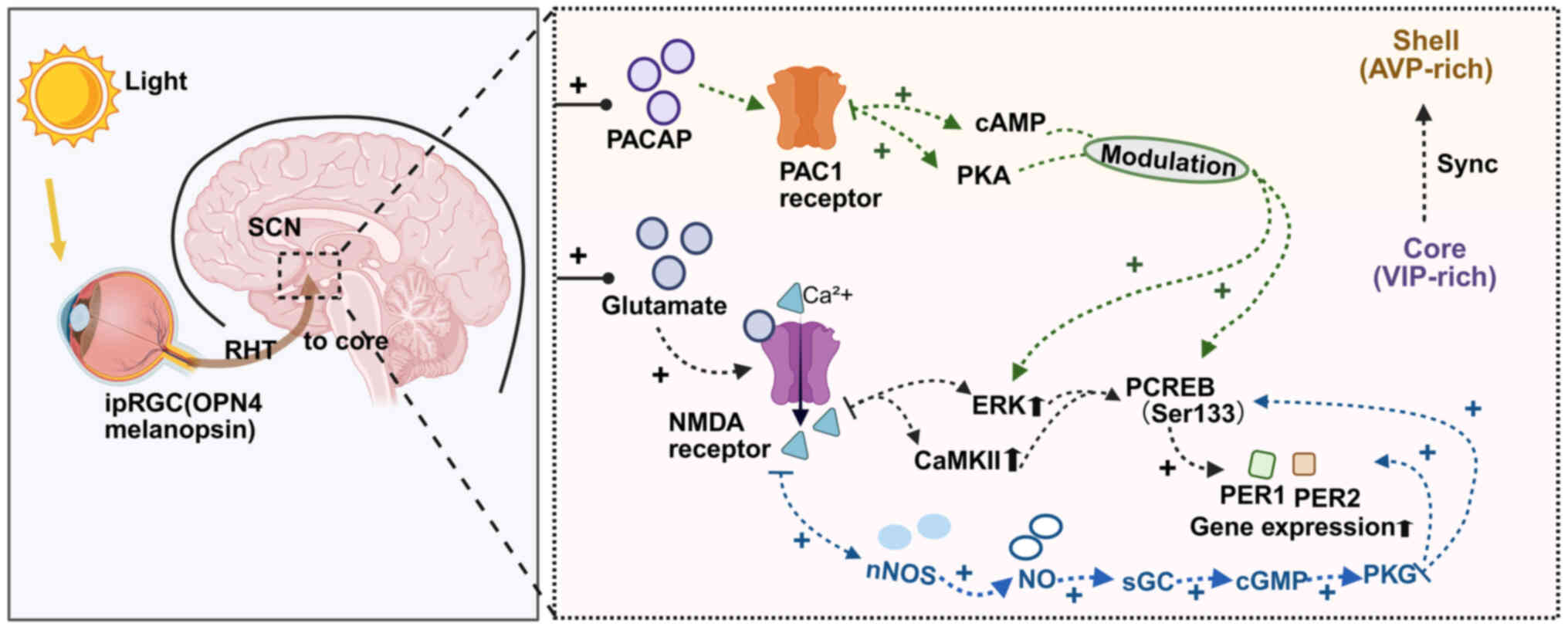

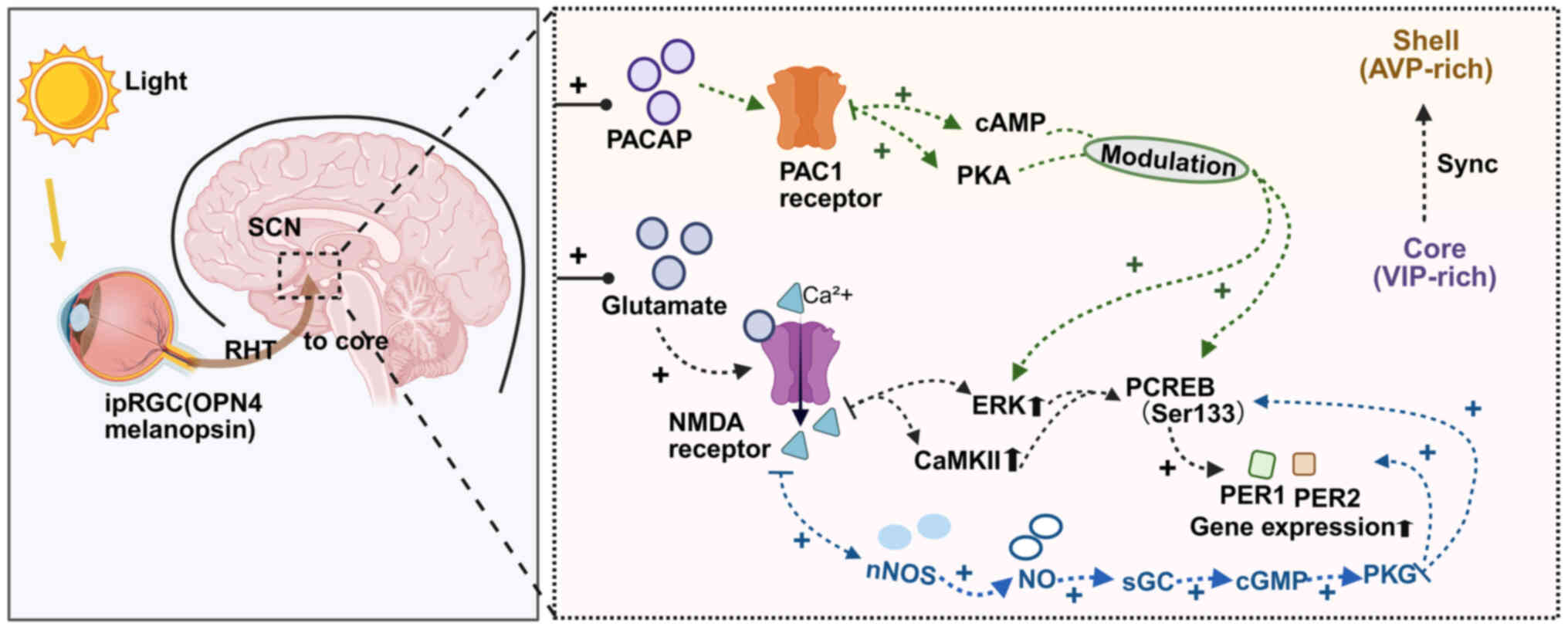

neurons that is the target of retinal input (Fig. 1) (24,25).

| Figure 1.Retinal input and intracellular

signaling underlying photic entrainment of the SCN. Light is

detected by melanopsin-expressing ipRGCs in the retina and conveyed

to the SCN via the RHT, which releases glutamate and PACAP. In SCN

neurons, glutamate activates NMDA receptors, elevating

Ca2+ and engaging CaMKII/ERK, which promotes CREB

(Ser133) phosphorylation and PER1/PER2 expression. In parallel,

Ca2+ activates nNOS and NO stimulates sGC to increase

cGMP, activating PKG that further supports CREB phosphorylation and

clock-gene induction. PACAP acting on PAC1 receptors modulates

these processes and stabilizes entrainment. SCN, suprachiasmatic

nucleus; ipRGCs, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion

cells; RHT, retinohypothalamic tract; PACAP, pituitary adenylate

cyclase-activating polypeptide; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; CaMKII,

calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; CREB, cAMP response

element-binding protein; period circadian protein homolog; nNOS,

neuronal nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; sGC, soluble

guanylyl cyclase; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; PKG,

protein kinase G; AVP, arginine vasopressin; VIP, vasoactive

intestinal polypeptide. |

The anatomical foundation of photoentrainment is the

RHT, a monosynaptic pathway originating from a subset of ipRGCs,

predominantly M1 cells, which terminates in the ventrolateral core

region of the SCN. The principal neurotransmitters released by RHT

terminals are glutamate and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating

polypeptide (PACAP) (4). These

transmitters have distinct but synergistic roles. Glutamate, acting

on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, is the primary mediator

of the acute, phase-shifting effects of light. Its release is

proportional to the light intensity and duration, triggering rapid

intracellular signaling. PACAP, acting on PAC1 receptors, plays a

more modulatory role, enhancing the SCN's sensitivity to glutamate

and being crucial for entrainment to full light-dark cycles and for

the long-term stability of the clock (26).

Upon light stimulation, the release of glutamate and

PACAP in the SCN initiates a complex intracellular signaling

cascade within postsynaptic SCN neurons (27). Glutamate-induced NMDA receptor

activation leads to a significant influx of Ca2+, which

in turn activates multiple downstream pathways, including

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and the

Ras/MAPK/ERK pathway. These kinases converge on the phosphorylation

of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein

(CREB) at its Serine-133 residue (28). Phosphorylated (p-)CREB then

translocates to the nucleus and binds to cAMP response elements in

the promoters of the core clock genes Per1 and Per2,

rapidly inducing their transcription (29). This light-driven surge in

Per expression is the molecular event that resets the phase

of the SCN clock. A light pulse in the early subjective night

advances the accumulation of PER protein, causing a phase delay,

while a pulse in the late subjective night or early morning

accelerates the declining phase of PER, leading to a phase advance

(30).

The SCN itself possesses a sophisticated internal

structure, comprising a ventrolateral ‘core’ and a dorsomedial

‘shell.’ The RHT innervates the core, which is rich in neurons

expressing vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. These core neurons

are the primary recipients of light information. They then

synchronize the much larger population of neurons in the shell,

which express arginine vasopressin and are considered the primary

output neurons of the SCN (31).

This core-shell network architecture allows the SCN to integrate

the photic signal, generate a robust, consolidated rhythm and then

broadcast this timing information to the rest of the brain and body

(32).

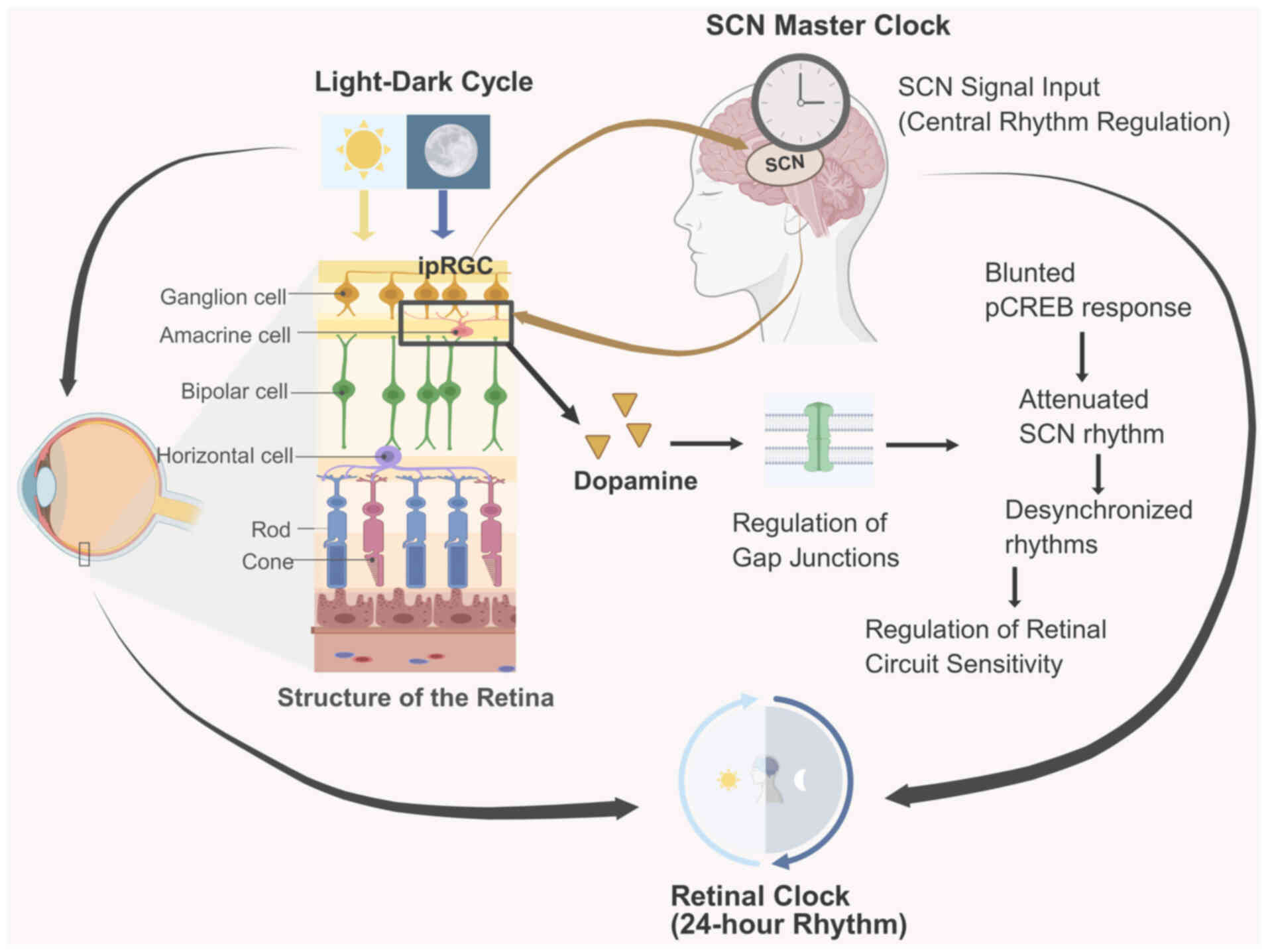

Disruptions to this system via retinal pathology

have profound consequences. In glaucoma models, the reduction in

ipRGC density leads to a quantifiable decrease in RHT input to the

SCN (33). This manifests as a

blunted pCREB response to light pulses, attenuated amplitude of the

SCN's overall electrical activity rhythm and, ultimately, the

desynchronization of behavioral and hormonal rhythms, such as

locomotor activity and melatonin secretion. In humans with advanced

glaucoma, these central deficits are correlated with clinical

reports of non-24-h sleep-wake disorder and depression (34). In cases of retinitis pigmentosa

where cone and rod function is lost but ipRGCs survive, the SCN can

still be entrained (35). However,

the system's sensitivity is markedly reduced, requiring much higher

irradiances of blue-enriched light to elicit a phase shift. This

highlights the critical contribution of the classical

photoreceptors in sensitizing the NIF system under normal

conditions (36).

Furthermore, the retina itself harbors an autonomous

circadian clock (Fig. 2). Clock

genes are rhythmically expressed in various retinal cell types,

including photoreceptors and dopaminergic amacrine cells,

regulating local physiological processes such as dopamine release,

gene expression and metabolic activity in a 24-h cycle (37). This retinal clock is synchronized

by both systemic signals from the SCN and the local light-dark

cycle. Dopamine, released rhythmically during the day, acts as a

key intraretinal signal that modulates gap junction coupling and

adjusts the sensitivity of retinal circuits. This local timekeeping

mechanism adds another layer of complexity, suggesting a

bidirectional communication system where the retina not only

signals time to the brain but also possesses its own intrinsic

temporal organization that fine-tunes its function across the

day-night cycle (38).

Light-evoked glutamatergic input from the RHT

elevates postsynaptic Ca2+ in SCN neurons via NMDA

receptors, which activates neuronal nitric oxide (NO) synthase

(nNOS) and drives NO production (39). NO stimulates soluble guanylyl

cyclase (sGC) to increase cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP),

engaging protein kinase G (PKG) pathways that facilitate

phosphorylation of CREB and the rapid induction of

Per1/Per2. Pharmacological inhibition of NOS or sGC

diminishes light-induced phase shifts and Per transcription,

whereas NO donors or membrane-permeant cGMP analogs enhance them

(40). Thus, NO functions as a

critical second-messenger amplifier that couples the initial RHT

glutamatergic signal to the transcriptional machinery that resets

the circadian clock. In parallel, intraretinal NO-produced by

amacrine and other interneurons-modulates gap junction coupling and

photoreceptor/bipolar signaling, shaping the irradiance code

ultimately delivered by ipRGCs to the SCN (41).

Retinal light input and the neurobiology of

sleep regulation

The regulation of the sleep-wake cycle is a complex

interplay between a homeostatic process, which increases sleep

pressure with time spent awake and the circadian process, which

dictates the timing of sleep and wakefulness. Retinal light

perception is the most powerful modulator of the circadian process,

influencing not only the timing of sleep but also its internal

architecture and consolidation through both acute alerting effects

and chronic entrainment of the central clock (42).

The SCN orchestrates the timing of sleep through a

network of efferent projections. One of the most critical pathways

is a multisynaptic circuit to the pineal gland. The SCN projects to

the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which in turn

sends signals down to preganglionic sympathetic neurons in the

intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord (43). These neurons drive postganglionic

fibers from the superior cervical ganglion that innervate the

pineal gland, controlling the synthesis and release of melatonin.

During the day, the SCN is active and inhibits this pathway. At

night, SCN activity wanes, disinhibiting the pathway and allowing

for robust melatonin production. Light exposure at night, detected

by retinal ipRGCs, rapidly reactivates the SCN, which clamps this

pathway shut, acutely suppressing melatonin synthesis. The spectral

sensitivity of this suppression reflex mirrors that of melanopsin,

with short-wavelength blue light being the most potent stimulus

(44).

In addition to its chronobiotic role, light exerts a

direct and immediate alerting effect on the brain. This is mediated

by ipRGC projections to key arousal centers, bypassing the SCN.

These projections innervate the lateral hypothalamic area, home to

the orexin/hypocretin neurons that are critical for maintaining

consolidated wakefulness, as well as monoaminergic arousal centers

in the brainstem, such as the noradrenergic locus coeruleus

(45). Activation of these

pathways by light can directly antagonize sleep-promoting signals.

For example, the SCN also regulates the ventrolateral preoptic

nucleus (VLPO), a key sleep-promoting center containing GABAergic

and galaninergic neurons that inhibit arousal systems (46). The SCN promotes VLPO activity

during the biological night. Light at night can therefore disrupt

this balance, both by directly stimulating arousal centers and by

suppressing the SCN's drive onto the VLPO, leading to fragmented

sleep and increased awakenings (47).

The differential effect of light spectra on sleep is

a direct consequence of the biophysics of retinal photoreceptors.

Short-wavelength blue light (~480 nm), through its potent

activation of the melanopsin system in ipRGCs, has the most

significant effects on sleep regulation (11). Evening exposure to blue-enriched

light has been demonstrated to not only suppress melatonin and

delay sleep onset but also to alter subsequent sleep architecture,

typically by reducing the amount of restorative slow-wave sleep,

characterized by high-amplitude delta (0.5-4 Hz)

electroencephalogram waves and decreasing the duration of rapid eye

movement sleep (45). By contrast,

evening exposure to long-wavelength red light, which minimally

stimulates ipRGCs, has little to no effect on melatonin or

circadian phase and preserves sleep architecture. This principle

underpins the strategy of using ‘circadian lighting’ or

blue-blocking filters to create a transition to sleep (44,48).

The clinical relevance of these mechanisms is most

evident in individuals with disrupted retinal input. Patients with

glaucoma or advanced diabetic retinopathy often suffer from severe

sleep fragmentation and insomnia, which correlate with the degree

of ipRGC damage as measured by objective tests such as the

pupillary light reflex (49). In

totally blind individuals without any light perception (that is,

with complete optic nerve destruction or bilateral enucleation),

the sleep-wake cycle often ‘free-runs’ with a period slightly

longer than 24 h, leading to a condition known as non-24-h

sleep-wake disorder (50).

However, in blind individuals who retain functional ipRGCs, timed

light administration can successfully entrain their rhythms,

highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting this residual

NIF pathway. The integrity of the retinal photic input pathway is

therefore a fundamental determinant of an individual's ability to

maintain a stable and restorative sleep-wake cycle (12).

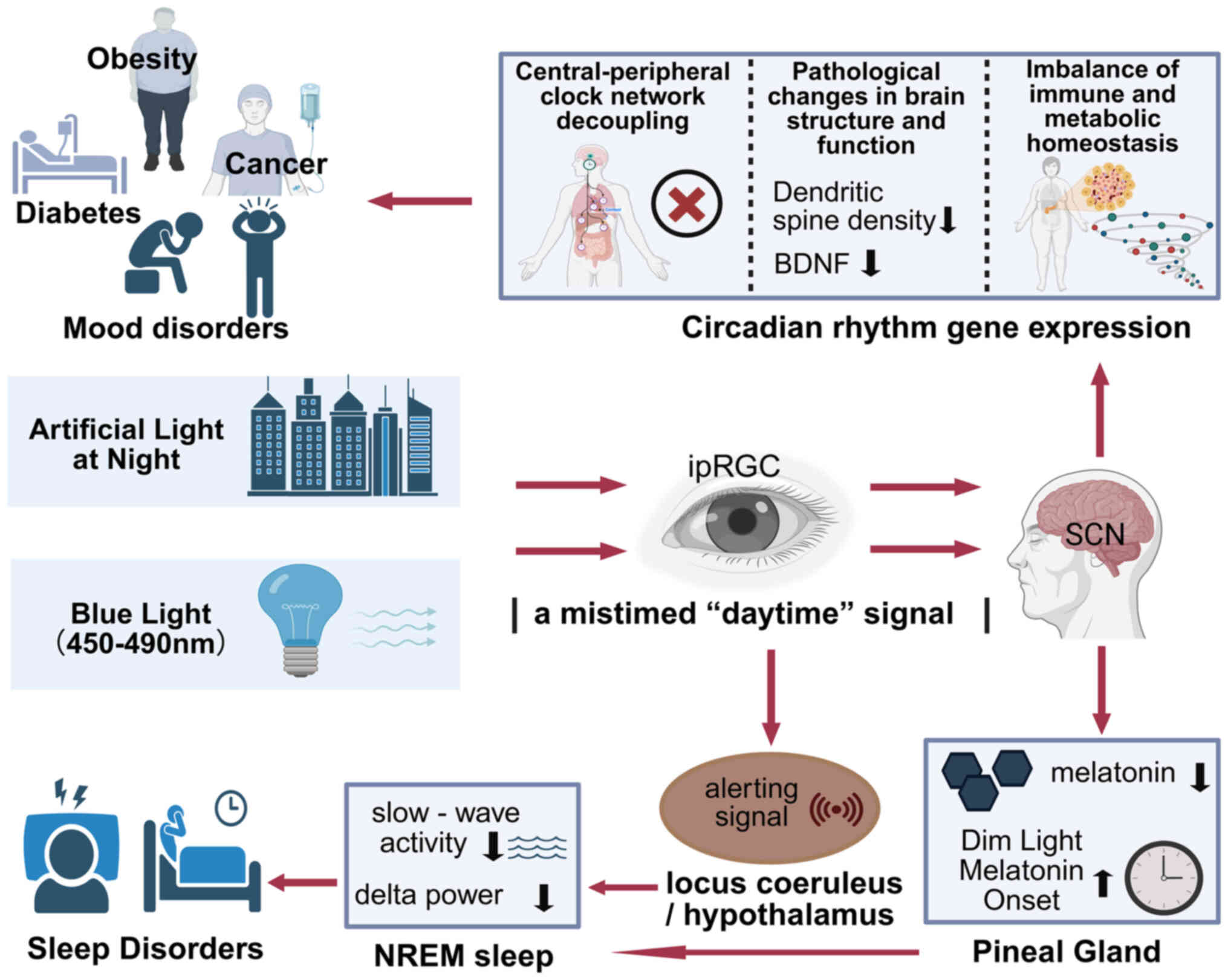

Systemic health consequences of retinal

light perception

The influence of retinal light perception extends

far beyond visual processing and sleep regulation, acting as the

primary synchronizing agent for the entire organism's physiology.

Through the RHT and other projections, photic information entrains

the central SCN pacemaker, which in turn orchestrates a hierarchy

of peripheral clocks in virtually every tissue (51). This establishes a direct and

profound link between ocular health, environmental light patterns

and systemic well-being. Consequently, circadian disruption,

initiated by aberrant retinal signaling from either pathological

conditions or unnatural light exposure, is now understood as a

fundamental pathogenic mechanism. It contributes to a spectrum of

chronic diseases by desynchronizing the tightly regulated temporal

expression of clock-controlled genes that govern metabolism, cell

cycle and immune function. Furthermore, direct retinal projections

to non-circadian brain centers inextricably link light perception

to the neurobiology of mood and mental health (Fig. 3) (12).

Metabolic dysregulation and

disease

The circadian system imposes a temporal order on

metabolism, ensuring that anabolic and catabolic processes are

aligned with feeding/fasting and activity/rest cycles. This

coordination is achieved by the SCN synchronizing peripheral clocks

within key metabolic organs. Chronic circadian disruption,

epitomized by shift work or exposure to light-at-night, severs this

synchrony, leading to internal temporal chaos with severe metabolic

consequences (52).

In the liver, the local clock, driven by rhythmic

transcription of Bmal1 and Clock, directly regulates hundreds of

genes involved in glucose and lipid homeostasis. For instance, the

clock-controlled protein REV-ERBα acts as a potent rhythmic

repressor of key gluconeogenic genes, including

glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase,

suppressing hepatic glucose output during the inactive/fasting

phase (53,54). Simultaneously, the liver clock

gates lipid metabolism by controlling the expression of sterol

regulatory element-binding protein 1c and its downstream targets

such as fatty acid synthase, restricting de novo lipogenesis

to the active/feeding phase (55)

Mistimed light exposure and consequent behavioral shifts (such as

eating at night) create a conflict between the central SCN signal

and metabolic substrate availability, uncoupling these genetic

programs and leading to pathological states such as insulin

resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease due to incessant

gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis (56,57).

In the pancreas, the clock within islet β-cells is

critical for normal insulin function. BMAL1/CLOCK heterodimers

directly regulate the transcription of genes essential for every

step of insulin secretion, from glucose transport (Slc2a2/GLUT2)

and ATP production to the function of the ATP-sensitive potassium

channels that trigger membrane depolarization. Circadian

misalignment impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and

reduces insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, creating a

direct pathway to the development of type 2 diabetes (58,59).

In adipose tissue, the local clock governs

adipogenesis and lipid storage, partly through the rhythmic control

of the master adipogenic transcription factor Pparg by BMAL1. This

clock also controls the rhythmic secretion of key adipokines. The

normal nocturnal peak of leptin, a satiety hormone, is blunted or

shifted by mistimed light and sleep, disrupting hunger signals and

contributing directly to obesity (60).

Circadian disruption and cancer

pathogenesis

The link between circadian disruption and cancer is

supported by robust epidemiological data and grounded in precise

molecular mechanisms that couple the clock to cell proliferation

and immune surveillance. The International Agency for Research on

Cancer has classified shift work involving circadian disruption as

a probable human carcinogen (3,61).

The core clock machinery is physically and

functionally integrated with the cell cycle. Key clock proteins,

such as period circadian protein homolog (PER)1 and PER2, can bind

to and inhibit critical cell cycle promoters such as Cyclin D1 and

the proto-oncogene c-Myc, acting as tumor suppressors. Conversely,

BMAL1/CLOCK rhythmically regulate the expression of the cell cycle

checkpoint kinase Wee1, which controls entry into mitosis.

Circadian disruption dismantles this temporal gating, permitting

uncontrolled cell proliferation (62).

A primary mechanistic link is the suppression of

nocturnal melatonin by light at night. Melatonin is a potent

oncostatic agent with pleiotropic anti-cancer effects. Through its

receptors, MT1 and MT2, melatonin can inhibit signaling pathways

crucial for cancer growth, such as the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt

pathways (63,64). It also has powerful

receptor-independent functions as a free radical scavenger,

protecting DNA from oxidative damage. Light-at-night exposure

effectively removes this endogenous anti-cancer brake, a mechanism

strongly implicated in the increased risk of hormone-sensitive

cancers such as estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer and

prostate cancer among night-shift workers (65).

Furthermore, the circadian clock regulates the

body's anti-tumor immune response. The trafficking and cytotoxic

function of immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells and

cytotoxic T lymphocytes, exhibit robust daily rhythms. For example,

NK cell infiltration into tumors and their lytic activity are

markedly higher during the early resting phase. Circadian

disruption flattens these rhythms, leading to impaired immune

surveillance and creating a permissive environment for tumor cells

to evade detection and elimination (66).

Direct retinal pathways and mental

health

The neurobiological connections between light and

mental health are increasingly understood to be mediated by direct

retinal projections to limbic and cortical circuits, independent of

the SCN. Specific ipRGC subtypes, project to non-circadian centers

that are fundamental to affective regulation (13). A critical pathway involves

projections to the lateral habenula (LHb), a nucleus that encodes

negative valence and aversive signals and is pathologically

hyperactive in depression (67).

The LHb exerts inhibitory control over midbrain monoaminergic

systems, including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) for dopamine

and the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) for serotonin. Preclinical

studies show that acute light exposure can rapidly suppress the

firing of LHb neurons via this retinal input, thereby disinhibiting

VTA and DRN neurons. This provides a direct, fast-acting mechanism

by which light can enhance motivation and elevate mood (5,68).

Another key target is the medial prefrontal cortex

(mPFC), essential for executive function and the cognitive

regulation of emotion. Light enhances activity and strengthens

glutamatergic synaptic plasticity in the mPFC, probably via a

multisynaptic ipRGC-thalamus-cortex pathway (69). This strengthens top-down control

over subcortical structures such as the amygdala, which is involved

in processing fear and anxiety.

The efficacy of bright light therapy for Seasonal

Affective Disorder (SAD) is a clinical manifestation of these

pathways. SAD is characterized by a phase-delayed circadian rhythm

and a hypothesized ‘retinal subsensitivity’ to light (70). High-intensity light therapy acts as

a potent retinal stimulus that both corrects the underlying

circadian misalignment and directly modulates these mood-relevant

circuits. The high comorbidity of depression in ophthalmic diseases

such as glaucoma and retinitis pigmentosa is also explained by

these mechanisms (71). The

progressive loss of ipRGCs in these conditions severs the photic

input to the SCN, LHb and mPFC, creating a state of ‘biological

darkness’ that fosters a neurochemical and network-level state

conducive to affective disorders, a pathology that transcends the

psychological burden of vision loss (72). This suggests that therapies aimed

at activating any residual ipRGC function could have significant

mental health benefits even in low-vision patients.

Compromised adaptive capacity due to

age and disease

The circadian system's ability to adapt to

environmental changes, such as trans-meridian travel, depends on

the robustness of the retinal signal relayed to the SCN. This

adaptive capacity is markedly compromised by both normal aging and

ocular disease. With aging, the crystalline lens naturally yellows,

acting as a short-pass filter that blocks a significant portion of

the blue light (460–480 nm) required to optimally stimulate

melanopsin (73). This, combined

with senile miosis (pupil constriction), dampens the photic signal

reaching the retina, contributing to the flattened circadian

amplitude, advanced sleep phase and fragmented sleep common in the

elderly (11,74). Cataract surgery, by replacing the

yellowed lens with a clear intraocular lens that transmits blue

light, has been shown to robustly improve circadian entrainment and

sleep consolidation, highlighting the clinical importance of

retinal light hygiene. In glaucoma, the apoptotic loss of ipRGCs

creates a permanent and progressive deficit in the NIF system,

impairing the gain of the system's response to light and

making it profoundly difficult for patients to entrain their

rhythms or adapt to environmental changes (8,75).

The retina and the challenge of modern light

exposure

The contemporary human light environment represents

a dramatic departure from the evolutionary conditions under which

our visual and circadian systems evolved. The transition from a

natural regimen of bright, full-spectrum sunlight during the day

and profound darkness at night to a life spent predominantly

indoors under dim, spectrally-narrow electric light, coupled with

pervasive exposure to artificial light at night (ALAN), presents a

significant physiological challenge (76). The retina, as the first point of

contact, is at the epicenter of this challenge and understanding

its response to modern lighting is critical for public health

(77).

The circadian potency of modern light

sources

The advent and ubiquity of solid-state lighting,

particularly ‘white’ light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and the back-lit

screens of electronic devices have fundamentally altered the

spectral diet of the modern eye. Unlike the smooth, black-body

radiation curve of incandescent light, numerous white LEDs operate

on a ‘blue pump-yellow phosphor’ principle (78). This creates a spectral power

distribution (SPD) with a narrow, high-energy peak in the

short-wavelength blue portion of the spectrum (typically 450–490

nm) to excite a phosphor that re-emits a broader band of

longer-wavelength light. This blue peak aligns almost perfectly

with the maximal spectral sensitivity of melanopsin in ipRGCs,

making these sources a powerful, albeit often unintended, stimulus

for the non-image-forming system (44).

When encountered in the evening, this blue-enriched

light transmits a potent, mistimed ‘daytime’ signal to the SCN and

other brain centers. The neurobiological consequences are

quantifiable and significant. Exposure to typical indoor light

levels can acutely suppress the amplitude and duration of the

nocturnal melatonin profile and markedly delay its onset (the Dim

Light Melatonin Onset, or DLMO), a key marker of circadian phase

(79). This disruption directly

affects sleep architecture by suppressing slow-wave activity and

delta power during subsequent non-rapid eye movement sleep, a

process vital for synaptic homeostasis and memory consolidation

(80,81). The direct alerting effect, which

counteracts homeostatic sleep pressure, is mediated by ipRGC

projections to the noradrenergic locus coeruleus and the

orexinergic neurons of the lateral hypothalamus. This highlights

the inadequacy of traditional photometry, based on photopic lux,

which is weighted towards cone sensitivity for vision (~555 nm) and

fails to capture the biological potency of light (82). Consequently, the concept of α-opic

lux, particularly Melanopic Equivalent Daylight Illuminance (MEDI),

has emerged. MEDI quantifies light based on its activation

potential for the melanopsin channel, providing a far more accurate

metric for predicting circadian, neuroendocrine and alerting

responses and it is becoming a critical tool for evidence-based

lighting design (83).

Urban light pollution and chronic

circadian disruption

Beyond personal devices, broad-scale urban light

pollution constitutes a chronic and pervasive source of circadian

disruption. ALAN from streetlights, buildings and advertising can

infiltrate sleeping environments, creating nocturnal light levels

that, while seemingly low (often ranging from <1 to >10 lux),

are well within the activation threshold of the highly sensitive

ipRGC system, especially when integrated over a number of hours

(84). Large-scale epidemiological

studies, leveraging satellite data to quantify outdoor ALAN, have

found strong correlations between residence in brightly lit areas

and increased odds ratios for obesity, type 2 diabetes, mood

disorders and certain cancers (85–87).

Causal mechanisms have been elucidated in controlled

animal models. Chronic exposure to dim light at night (~5 lux) is

sufficient to markedly dampen the amplitude of the SCN's rhythmic

molecular clock gene expression. This central disruption cascades

to peripheral systems and directly impacts brain structures crucial

for mood and cognition (88). For

example, in rodents, dim ALAN has been shown to reduce dendritic

spine density in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, decrease levels

of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and impair performance on

hippocampus-dependent spatial memory tasks such as the Morris water

maze (48). These structural and

functional deficits are the neurobiological underpinnings of the

depressive-such as behaviors, such as increased immobility in the

forced swim test, observed in these animals. The retina's ipRGCs

are the unequivocal mediators of this effect, transmitting a

persistent, low-level disruptive signal to the brain throughout the

biological night (44).

Ophthalmic and behavioral intervention

strategies

In response to these challenges, several

intervention strategies based on the neurophysiology of the NIF

system have been developed. Blue-light filtering lenses aim to

attenuate the evening circadian stimulus (89). These range from lenses with

blue-reflecting coatings to short-wavelength-absorbing filters

(which appear yellow or amber). Studies show that amber lenses,

which markedly block light below ~500 nm, can effectively prevent

light-induced melatonin suppression and preserve the natural timing

of the DLMO (90). However, the

clinical efficacy remains debated, as it is highly dependent on the

precise spectral characteristics and the total amount of light

being blocked. Furthermore, indiscriminate use during the day could

be counterproductive, dampening the necessary alerting and

entraining signals (91).

A more proactive approach is structured light

therapy, which uses the light Phase Response Curve as a guiding

principle. Morning bright light therapy (typically 10,000 photopic

lux, which is high in melanopic content, for 30 min upon awakening)

is a first-line treatment for SAD and delayed sleep-wake phase

disorder because it provides a powerful, timed phase-advancing

signal to the SCN (92). For

patients with retinal diseases, these protocols can be

personalized. For instance, in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa

who has lost cone function but retains ipRGCs, a therapeutic device

could use monochromatic blue light (~480 nm) to selectively and

efficiently activate the residual melanopsin system for

entrainment, a wavelength that would be useless for image formation

(43).

The future of lighting lies in dynamic,

human-centric (or integrative) lighting systems. These systems use

multi-channel LED engines (such as combining red, green, blue and

white/amber LEDs) to actively sculpt the SPD of indoor light

throughout the day (93). The goal

is to create a biomimetic light cycle: high-intensity, high-CCT

(Correlated Color Temperature) light with a high MEDI (>250

melanopic lux) in the morning and midday to maximize alertness,

performance and circadian entrainment; followed by a gradual

transition to low-intensity, low-CCT light with a markedly reduced

MEDI (<10 melanopic lux) in the evening, thereby creating a

state of ‘circadian darkness’ that protects the melatonin rhythm

and facilitates sleep (37,94).

A summary of clinical conditions, their NIF deficits and possible

interventions is provided in Table

II.

| Table II.Effect of ophthalmic diseases and

modern lighting on NIF functions and intervention strategies. |

Table II.

Effect of ophthalmic diseases and

modern lighting on NIF functions and intervention strategies.

|

Condition/Factor | NIF system

deficit | Main symptoms | Potential

intervention |

|---|

| Glaucoma | ipRGC loss, reduced

RHT signaling | Sleep disturbance,

mood disorders | IOP control,

structured light therapy, pupil response tests |

| Retinitis

pigmentosa | Loss of rods/cones,

ipRGC preserved | Poor circadian

entrainment, insomnia | Blue-light therapy,

time-restricted lighting |

| Aging/cataract | Reduced blue light

transmission | Advanced sleep

phase, fragmented sleep | Cataract surgery,

daylight exposure |

| Urban ALAN (light

pollution) | Excess blue light

at night | Circadian

misalignment, metabolic risk | Blue-blocking

filters, smart home lighting |

| Shift work | Chronic circadian

disruption | Insomnia, metabolic

disease, cancer | Scheduled

light/dark exposure, chronotherapy |

Future research directions and unanswered

questions

Despite monumental progress in understanding the

retina's role in NIF functions, numerous critical questions and

technological challenges remain. Future research must pursue a

multi-pronged approach, combining molecular genetics, systems

neuroscience and clinical investigation to further unravel the

complexities of retinal light perception and translate this

knowledge into effective clinical and public health strategies

(95).

A primary frontier is the deeper molecular and

functional characterization of ipRGC diversity. While the M1-M6

classification has provided a valuable framework, it is probably an

oversimplification. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial

transcriptomics are poised to reveal a more granular taxonomy of

ipRGC subtypes, identifying unique molecular signatures,

developmental lineages and signaling pathways for each (96). A key goal is to precisely map the

full ‘projectome’ of each subtype, that is, to identify all of its

downstream brain targets, and to functionally interrogate the role

of each specific projection in behavior and physiology using

advanced techniques such as optogenetics and chemogenetics in

animal models. Understanding the differential vulnerability of

these specific subtypes in diseases such as glaucoma is a critical

clinical question that could lead to more targeted diagnostics and

neuroprotective strategies. Furthermore, the detailed biophysical

properties of melanopsin itself, including its signaling dynamics

and regeneration cycle under various lighting conditions and in

pathological states, warrant continued investigation (97).

The development of personalized light therapy and

precision light exposure management represents a significant

translational goal (98). The

current ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to light therapy does not

account for the vast inter-individual variability in light

sensitivity, chronotype, genetics (such as polymorphisms in clock

genes), age, or the health status of the retina. Future research

should focus on developing objective biomarkers, perhaps based on

pupillometry, melatonin profiles, or electroretinography, to

quantify an individual's NIF function. These data could then be

integrated with genetic information and lifestyle monitoring from

wearable sensors into machine learning algorithms to generate truly

personalized light ‘prescriptions’ (99). This would involve specifying the

optimal dose (intensity), spectrum, timing and duration of light

needed to achieve a desired therapeutic outcome, whether it be

advancing a delayed sleep phase, alleviating depressive symptoms,

or bolstering circadian rhythms in an elderly individual or a

patient with retinal disease. The integration of such intelligent

systems with smart home and workplace lighting environments could

enable the seamless, automated delivery of optimal light exposure

throughout the 24-h day (100).

Finally, progress in this field will be critically

dependent on enhanced interdisciplinary collaboration. The study of

retinal light perception sits at the crossroads of ophthalmology,

neuroscience, sleep medicine, psychiatry and engineering.

Large-scale, longitudinal studies are needed to move beyond

correlation and establish causality between specific light exposure

patterns and long-term health outcomes, such as the incidence of

metabolic disease or cognitive decline. Collaboration between

ophthalmologists and neuroscientists is essential for elucidating

the precise circuit-level mechanisms by which retinal diseases lead

to systemic symptoms and for co-developing novel therapies that

target the NIF system (101).

Similarly, partnerships with sleep physicians and psychiatrists

will be crucial for designing and implementing rigorous clinical

trials to expand the application of light therapy to a broader

range of disorders and to optimize its combination with

pharmacological or psychological treatments (102). By integrating multi-modal data

from genomics, neuroimaging and wearable physiological sensors into

comprehensive computational models, the scientific community can

hope to build a holistic, systems-level understanding of how light,

as perceived by the eye, shapes human health and well-being

(80).

Conclusion

The retina's functional scope extends far beyond its

role as an organ of sight; it is a critical neuroendocrine gateway

that translates environmental light into the fundamental language

of biological time. Retinal dysfunction, whether caused by disease

or injury, not only leads to visual impairment but is frequently

accompanied by a debilitating constellation of non-image-forming

deficits, including circadian arrhythmia and sleep disorders, which

underscores the imperative of maintaining retinal health for

systemic physiological stability. Concurrently, the unprecedented

light exposure patterns of modern life, dominated by indoor living

and nocturnal blue-light exposure, pose a continuous challenge to

the retina's photosensory mechanisms, exacerbating the risk of

circadian misalignment. The confluence of these pathological and

environmental factors profoundly affects the retina's ability to

regulate circadian rhythms and sleep, highlighting the pressing

need for scientifically-guided strategies to manage light exposure

and preserve retinal function. A deep and mechanistic understanding

of retinal photobiology, particularly the function of the

melanopsin-ipRGC system, provides a robust foundation for designing

precise and personalized light-based interventions (103). A clearer appreciation of the

NO-cGMP pathway in the SCN, alongside melanopsin-driven

glutamatergic and PACAP signaling, may refine light-based

interventions and improve interpretation of circadian vulnerability

in ophthalmic disease. Advanced light therapies and intelligent

lighting technologies hold immense promise for improving sleep

quality, stabilizing mood and preventing a host of rhythm-related

pathologies. The continued synergy of ophthalmology, neuroscience

and sleep medicine will drive further discovery, fostering the

development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic paradigms that

leverage the power of light to optimize human health.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Open Fund of the Key

Laboratory for Hubei Province (grant no. 2023KFZZ026).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MY conceived the study, conducted the literature

search, drafted the manuscript and designed the figures. HL

contributed to literature screening, data extraction and

verification, literature review and critical manuscript revision.

RZ participated in the literature search, manuscript drafting and

data analysis. YL collected literature, prepared tables and revised

the manuscript. SS supervised the overall project, was responsible

for manuscript writing and critical revision. AY supervised the

study and revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Campbell I, Sharifpour R and Vandewalle G:

Light as a modulator of non-image-forming brain functions-positive

and negative impacts of increasing light availability. Clocks

Sleep. 5:116–140. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Abbott KS, Queener HM and Ostrin LA: The

ipRGC-driven pupil response with light exposure, refractive error

and sleep. Optom Vis Sci. 95:323–331. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lazzerini Ospri L, Prusky G and Hattar S:

Mood, the circadian system and melanopsin retinal ganglion cells.

Annu Rev Neurosci. 40:539–556. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Stinchcombe AR, Hu C, Walch OJ, Faught SD,

Wong KY and Forger DB: M1-Type, but Not M4-Type, melanopsin

ganglion cells are physiologically tuned to the central circadian

clock. Front Neurosci. 15:6529962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wagle M, Zarei M, Lovett-Barron M, Poston

KT, Xu J, Ramey V, Pollard KS, Prober DA, Schulkin J, Deisseroth K

and Guo S: Brain-wide perception of the emotional valence of light

is regulated by distinct hypothalamic neurons. Mol Psychiatry.

27:3777–3793. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gooley JJ, Ho Mien I, St Hilaire MA, Yeo

SC, Chua EC, van Reen E, Hanley CJ, Hull JT, Czeisler CA and

Lockley SW: Melanopsin and rod-cone photoreceptors play different

roles in mediating pupillary light responses during exposure to

continuous light in humans. J Neurosci. 32:14242–14253. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Schmidt TM, Chen SK and Hattar S:

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells: many subtypes,

diverse functions. Trends Neurosci. 34:572–580. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Matynia A, Recio BS, Myers Z, Parikh S,

Goit RK, Brecha NC and Perez de Sevilla Muller L: Preservation of

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) in

Late adult mice: Implications as a potential biomarker for early

onset ocular degenerative diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

65:282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ksendzovsky A, Pomeraniec IJ, Zaghloul KA,

Provencio JJ and Provencio I: Clinical implications of the

melanopsin-based non-image-forming visual system. Neurology.

88:1282–1290. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mure LS: Intrinsically photosensitive

retinal ganglion cells of the human Retina. Front Neurol.

12:6363302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang G, Liu YF, Yang Z, Yu CX, Tong Q,

Tang YL, Shao YQ, Wang LQ, Xu X, Cao H, et al: Short-term acute

bright light exposure induces a prolonged anxiogenic effect in mice

via a retinal ipRGC-CeA circuit. Sci Adv. 9:eadf46512023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Vartanian GV, Zhao X and Wong KY: Using

flickering light to enhance nonimage-forming visual stimulation in

humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 56:4680–4688. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Aranda ML and Schmidt TM: Diversity of

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells: Circuits and

functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 78:889–907. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Moore RY: The suprachiasmatic nucleus and

the circadian timing system. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 119:1–28.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Do MTH: Melanopsin and the intrinsically

photosensitive retinal ganglion cells: Biophysics to behavior.

Neuron. 104:205–226. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mure LS, Hatori M, Ruda K, Benegiamo G,

Demas J and Panda S: Sustained melanopsin photoresponse is

supported by specific roles of β-Arrestin 1 and 2 in deactivation

and regeneration of photopigment. Cell Rep. 25:2497–2509.e4. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lucas RJ: Chromophore regeneration:

Melanopsin does its own thing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:10153–10154. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lee SK, Sonoda T and Schmidt TM: M1

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells integrate rod

and melanopsin inputs to signal in low light. Cell Rep.

29:3349–3355. e22019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lazarus C, Soheilypour M and Mofrad MR:

Torsional behavior of axonal microtubule bundles. Biophys J.

109:231–239. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

St Hilaire MA, Amundadottir ML, Rahman SA,

Rajaratnam SMW, Ruger M, Brainard GC, Czeisler CA, Andersen M,

Gooley JJ and Lockley SW: The spectral sensitivity of human

circadian phase resetting and melatonin suppression to light

changes dynamically with light duration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

119:e22053011192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Melelli A, Jamme F, Beaugrand J and

Bourmaud A: Evolution of the ultrastructure and polysaccharide

composition of flax fibres over time: When history meets science.

Carbohydr Polym. 291:1195842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yoshikawa T, Obayashi K, Miyata K, Saeki K

and Ogata N: Association between postillumination pupil response

and glaucoma severity: A cross-sectional analysis of the LIGHT

study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 63:242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hatori M and Panda S: The emerging roles

of melanopsin in behavioral adaptation to light. Trends Mol Med.

16:435–446. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schmidt C, Collette F, Reichert CF, Maire

M, Vandewalle G, Peigneux P and Cajochen C: Pushing the Limits:

Chronotype and time of day modulate working memory-dependent

cerebral activity. Front Neurol. 6:1992015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Blume C and Münch M: Effects of light on

biological functions and human sleep. Handb Clin Neurol. 206:3–16.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pan D, Wang Z, Chen Y and Cao J:

Melanopsin-mediated optical entrainment regulates circadian rhythms

in vertebrates. Commun Biol. 6:10542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Purrier N, Engeland WC and Kofuji P: Mice

deficient of glutamatergic signaling from intrinsically

photosensitive retinal ganglion cells exhibit abnormal circadian

photoentrainment. PLoS One. 9:e1114492014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li Y, Wu H, Liu N, Cao X, Yang Z, Lu B, Hu

R, Wang X and Wen J: Melatonin exerts an inhibitory effect on

insulin gene transcription via MTNR1B and the downstream Raf-1/ERK

signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 41:955–961. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Brenna A, Ripperger JA, Saro G, Glauser

DA, Yang Z and Albrecht U: PER2 mediates CREB-dependent light

induction of the clock gene Per1. Sci Rep. 11:217662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lee B, Li A, Hansen KF, Cao R, Yoon JH and

Obrietan K: CREB influences timing and entrainment of the SCN

circadian clock. J Biol Rhythms. 25:410–420. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ono D, Weaver DR, Hastings MH, Honma KI,

Honma S and Silver R: The suprachiasmatic nucleus at 50: Looking

back, then looking forward. J Biol Rhythms. 39:135–165. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Blume C, Cajochen C, Schollhorn I, Slawik

HC and Spitschan M: Effects of calibrated blue-yellow changes in

light on the human circadian clock. Nat Hum Behav. 8:590–605. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gubin D and Weinert D: Melatonin,

circadian rhythms and glaucoma: current perspective. Neural Regen

Res. 17:1759–1760. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gao J, Provencio I and Liu X:

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in glaucoma.

Front Cell Neurosci. 16:9927472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang J, Wang H, Wu S, Liu Q and Wang N:

Regulation of reentrainment function is dependent on a certain

minimal number of intact functional ipRGCs in rd Mice. J

Ophthalmol. 2017:68048532017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lucas RJ: Mammalian inner retinal

photoreception. Curr Biol. 23:R125–R133. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bilu C, Einat H, Zimmet P, Vishnevskia-Dai

V and Kronfeld-Schor N: Beneficial effects of daytime

high-intensity light exposure on daily rhythms, metabolic state and

affect. Sci Rep. 10:197822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Rahman SA, Brainard GC, Czeisler CA and

Lockley SW: Spectral sensitivity of circadian phase resetting,

melatonin suppression and acute alerting effects of intermittent

light exposure. Biochem Pharmacol. 191:1145042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Starnes AN and Jones JR: Inputs and

outputs of the mammalian circadian clock. Biology (Basel).

12:5082023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Reghunandanan V and Reghunandanan R:

Neurotransmitters of the suprachiasmatic nuclei. J Circadian

Rhythms. 4:22006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ashton A, Foster RG and Jagannath A:

Photic entrainment of the circadian system. Int J Mol Sci.

23:7292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang Z, Beier C, Weil T and Hattar S: The

retinal ipRGC-preoptic circuit mediates the acute effect of light

on sleep. Nat Commun. 12:51152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Fernandez DC, Fogerson PM, Lazzerini Ospri

L, Thomsen MB, Layne RM, Severin D, Zhan J, Singer JH, Kirkwood A,

Zhao H, et al: Light affects mood and learning through distinct

retina-brain pathways. Cell. 175:71–84. e182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ostrin LA, Abbott KS and Queener HM:

Attenuation of short wavelengths alters sleep and the ipRGC pupil

response. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 37:440–450. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Rupp AC, Ren M, Altimus CM, Fernandez DC,

Richardson M, Turek F, Hattar S and Schmidt TM: Distinct ipRGC

subpopulations mediate light's acute and circadian effects on body

temperature and sleep. Elife. 8:e443582019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Peplow M: Structure: The anatomy of sleep.

Nature. 497:S2–S3. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Pilorz V, Tam SK, Hughes S, Pothecary CA,

Jagannath A, Hankins MW, Bannerman DM, Lightman SL, Vyazovskiy VV,

Nolan PM, et al: Melanopsin regulates both sleep-promoting and

arousal-promoting responses to light. PLoS Biol. 14:e10024822016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Pun TB, Phillips CL, Marshall NS, Comas M,

Hoyos CM, D'Rozario AL, Bartlett DJ, Davis W, Hu W, Naismith SL, et

al: The effect of light therapy on electroencephalographic sleep in

sleep and circadian rhythm disorders: A scoping review. Clocks

Sleep. 4:358–373. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yang C, Yang W, Chen Y, Cheng Q and Chen

W: Improving renoprotective effects by adding piperazine ferulate

and angiotensin receptor blocker in diabetic nephropathy: A

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Urol Nephrol.

54:299–307. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Atan YS, Subasi M, Guzel Ozdemir P and

Batur M: The effect of blindness on biological rhythms and the

consequences of circadian rhythm disorder. Turk J Ophthalmol.

53:111–119. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Besharse JC and McMahon DG: The retina and

other light-sensitive ocular clocks. J Biol Rhythms. 31:223–243.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Poggiogalle E, Jamshed H and Peterson CM:

Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid and energy metabolism in

humans. Metabolism. 84:11–27. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Verlande A, Chun SK, Goodson MO, Fortin

BM, Bae H, Jang C and Masri S: Glucagon regulates the stability of

REV-ERBα to modulate hepatic glucose production in a model of lung

cancer-associated cachexia. Sci Adv. 7:eabf38852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang Y, Papazyan R, Damle M, Fang B,

Jager J, Feng D, Peed LC, Guan D, Sun Z and Lazar MA: The hepatic

circadian clock fine-tunes the lipogenic response to feeding

through RORα/γ. Genes Dev. 31:1202–1211. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sengupta S, Tang SY, Devine JC, Anderson

ST, Nayak S, Zhang SL, Valenzuela A, Fisher DG, Grant GR, López CB

and FitzGerald GA: Circadian control of lung inflammation in

influenza infection. Nat Commun. 10:41072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Montanari T, Boschi F and Colitti M:

Comparison of the effects of browning-inducing capsaicin on two

murine adipocyte models. Front Physiol. 10:13802019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Reutrakul S, Crowley SJ, Park JC, Chau FY,

Priyadarshini M, Hanlon EC, Danielson KK, Gerber BS, Baynard T, Yeh

JJ and McAnany JJ: Relationship between intrinsically

photosensitive ganglion cell function and circadian regulation in

diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep. 10:15602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Lee J, Moulik M, Fang Z, Saha P, Zou F, Xu

Y, Nelson DL, Ma K, Moore DD and Yechoor VK: Bmal1 and β-cell clock

are required for adaptation to circadian disruption and their loss

of function leads to oxidative stress-induced β-cell failure in

mice. Mol Cell Biol. 33:2327–2338. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wheaton KL, Hansen KF, Aten S, Sullivan

KA, Yoon H, Hoyt KR and Obrietan K: The Phosphorylation of CREB at

serine 133 is a key event for circadian clock timing and

entrainment in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms.

33:497–514. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Figueiro MG, Plitnick B and Rea MS: Light

modulates leptin and ghrelin in sleep-restricted adults. Int J

Endocrinol. 2012:5307262012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Papantoniou K, Devore EE, Massa J,

Strohmaier S, Vetter C, Yang L, Shi Y, Giovannucci E, Speizer F and

Schernhammer ES: Rotating night shift work and colorectal cancer

risk in the nurses' health studies. Int J Cancer. 143:2709–2717.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zeng Y, Guo Z, Wu M, Chen F and Chen L:

Circadian rhythm regulates the function of immune cells and

participates in the development of tumors. Cell Death Discov.

10:1992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Mayo JC, Hevia D, Quiros-Gonzalez I,

Rodriguez-Garcia A, Gonzalez-Menendez P, Cepas V, Gonzalez-Pola I

and Sainz RM: IGFBP3 and MAPK/ERK signaling mediates

melatonin-induced antitumor activity in prostate cancer. J Pineal

Res. Nov 9–2017.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Chen K, Zhu P, Chen W, Luo K, Shi XJ and

Zhai W: Melatonin inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion by

inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis via suppression of the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in gallbladder cancer cells. Aging

(Albany NY). 13:22502–22515. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Davis S, Mirick DK and Stevens RG: Night

shift work, light at night and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer

Inst. 93:1557–1562. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Rayatdoost E, Rahmanian M, Sanie MS,

Rahmanian J, Matin S, Kalani N, Kenarkoohi A, Falahi S and Abdoli

A: Sufficient sleep, time of vaccination and vaccine efficacy: A

systematic review of the current evidence and a proposal for

COVID-19 vaccination. Yale J Biol Med. 95:221–235. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu X, Li H, Ma R, Tong X, Wu J, Huang X,

So KF, Tao Q, Huang L, Lin S and Ren C: Burst firing in

output-defined parallel habenula circuit underlies the

antidepressant effects of bright light treatment. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e24010592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Huang L, Xi Y, Peng Y, Yang Y, Huang X, Fu

Y, Tao Q, Xiao J, Yuan T, An K, et al: A visual circuit related to

habenula underlies the antidepressive effects of light therapy.

Neuron. 102:128–142. e82019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Lazzerini Ospri L, Zhan JJ, Thomsen MB,

Wang H, Komal R, Tang Q, Messanvi F, du Hoffmann J, Cravedi K,

Chudasama Y, et al: Light affects the prefrontal cortex via

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Sci Adv.

10:eadh92512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Hirakawa H, Terao T, Muronaga M and Ishii

N: Adjunctive bright light therapy for treating bipolar depression:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trials. Brain Behav. 10:e018762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Burns AC, Saxena R, Vetter C, Phillips

AJK, Lane JM and Cain SW: Time spent in outdoor light is associated

with mood, sleep and circadian rhythm-related outcomes: A

cross-sectional and longitudinal study in over 400,000 UK Biobank

participants. J Affect Disord. 295:347–352. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zangen E, Hadar S, Lawrence C, Obeid M,

Rasras H, Hanzin E, Aslan O, Zur E, Schulcz N, Cohen-Hatab D, et

al: Prefrontal cortex neurons encode ambient light intensity

differentially across regions and layers. Nat Commun. 15:55012024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Chen G, Chen P, Yang Z, Ma W, Yan H, Su T,

Zhang Y, Qi Z, Fang W, Jiang L, et al: Increased functional

connectivity between the midbrain and frontal cortex following

bright light therapy in subthreshold depression: A randomized

clinical trial. Am Psychol. 79:437–450. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Marsden WN: Synaptic plasticity in

depression: Molecular, cellular and functional correlates. Prog

Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 43:168–184. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Bedrosian TA and Nelson RJ: Timing of

light exposure affects mood and brain circuits. Transl Psychiatry.

7:e10172017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Khodasevich D, Tsui S, Keung D, Skene DJ,

Revell V and Martinez ME: Characterizing the modern light

environment and its influence on circadian rhythms. Proc Biol Sci.

288:202107212021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Lee J, Liu R, de Jesus D, Kim BS, Ma K,

Moulik M and Yechoor V: Circadian control of β-cell function and

stress responses. Diabetes Obes Metab. 17 (Suppl 1):S123–S133.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Tosini G, Ferguson I and Tsubota K:

Effects of blue light on the circadian system and eye physiology.

Mol Vis. 22:61–72. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Hanifin JP, Lockley SW, Cecil K, West K,

Jablonski M, Warfield B, James M, Ayers M, Byrne B, Gerner E, et

al: Randomized trial of polychromatic blue-enriched light for

circadian phase shifting, melatonin suppression and alerting

responses. Physiol Behav. 198:57–66. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Stefani O, Schollhorn I and Munch M:

Towards an evidence-based integrative lighting score: A proposed

multi-level approach. Ann Med. 56:23812202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

He M, Chen H, Li S, Ru T, Chen Q and Zhou

G: Evening prolonged relatively low melanopic equivalent daylight

illuminance light exposure increases arousal before and during

sleep without altering sleep structure. J Sleep Res. 33:e141132024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Vethe D, Drews HJ, Scott J, Engstrøm M,

Heglum HSA, Grønli J, Wisor JP, Sand T, Lydersen S, Kjørstad K, et

al: Evening light environments can be designed to consolidate and

increase the duration of REM-sleep. Sci Rep. 12:87192022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Russart KLG, Chbeir SA, Nelson RJ and

Magalang UJ: Light at night exacerbates metabolic dysfunction in a

polygenic mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Life Sci.

231:1165742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Lam C and Chung MH: Dose-response effects

of light therapy on sleepiness and circadian phase shift in shift

workers: A meta-analysis and moderator analysis. Sci Rep.

11:119762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Mason IC, Qian J, Adler GK and Scheer

FAJL: Impact of circadian disruption on glucose metabolism:

Implications for type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 63:462–472. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Engin A: Misalignment of circadian rhythms

in diet-induced obesity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1460:27–71. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Barber LE, VoPham T, White LF, Roy HK,

Palmer JR and Bertrand KA: Circadian disruption and colorectal

cancer incidence in black women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.

32:927–935. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Fonken LK, Aubrecht TG, Melendez-Fernandez

OH, Weil ZM and Nelson RJ: Dim light at night disrupts molecular

circadian rhythms and increases body weight. J Biol Rhythms.

28:262–271. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Liset R, Gronli J, Henriksen RE, Henriksen

TEG, Nilsen RM and Pallesen S: A randomized controlled trial on the

effect of blue-blocking glasses compared to partial blue-blockers

on melatonin profile among nulliparous women in third trimester of

the pregnancy. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 12:1000742021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Esaki Y, Kitajima T, Ito Y, Koike S, Nakao

Y, Tsuchiya A, Hirose M and Iwata N: Wearing blue light-blocking

glasses in the evening advances circadian rhythms in the patients

with delayed sleep phase disorder: An open-label trial. Chronobiol

Int. 33:1037–1044. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Arora S, Houdek P, Cajka T, Dockal T,

Sladek M and Sumova A: Chronodisruption that dampens output of the

central clock abolishes rhythms in metabolome profiles and elevates

acylcarnitine levels in the liver of female rats. Acta Physiol

(Oxf). 241:e142782025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Hester L, Dang D, Barker CJ, Heath M,

Mesiya S, Tienabeso T and Watson K: Evening wear of blue-blocking

glasses for sleep and mood disorders: A systematic review.

Chronobiol Int. 38:1375–1383. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Ru T, Kompier ME, Chen Q, Zhou G and

Smolders KC: Temporal tuning of illuminance and spectrum: Effect of

a full-day dynamic lighting pattern on well-being, performance and

sleep in simulated office environment. Building and Environment.

228:1098422023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Grant LK, Crosthwaite PC, Mayer MD, Wang

W, Stickgold R, St Hilaire MA, Lockley SW and Rahman SA:

Supplementation of ambient lighting with a task lamp improves

daytime alertness and cognitive performance in sleep-restricted

individuals. Sleep. 46:zsad0962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Oh AJ, Amore G, Sultan W, Asanad S, Park

JC, Romagnoli M, La Morgia C, Karanjia R, Harrington MG and Sadun

AA: Pupillometry evaluation of melanopsin retinal ganglion cell

function and sleep-wake activity in pre-symptomatic Alzheimer's

disease. PLoS One. 14:e02261972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Berg DJ, Kartheiser K, Leyrer M, Saali A

and Berson DM: Transcriptomic signatures of postnatal and adult

intrinsically photosensitive ganglion cells. eNeuro.

6:ENEURO.0022–19.2019. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Liberman AR, Kwon SB, Vu HT, Filipowicz A,

Ay A and Ingram KK: Circadian Clock Model Supports Molecular Link

Between PER3 and Human Anxiety. Sci Rep. 7:98932017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Chellappa SL: Individual differences in

light sensitivity affect sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep.

44:zsaa2142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Schollhorn I, Stefani O, Lucas RJ,

Spitschan M, Epple C and Cajochen C: The impact of pupil