Introduction

Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) is a peptide

hormone that is important for embryonic development and the

regulation of metabolic processes (1,2).

IGF2 expression is tightly regulated by genomic imprinting, which

ensures spatially and temporally precise activity (3,4).

Beyond its role in development, IGF2 is involved in kidney

physiology by promoting cell proliferation, metabolic activity and

tissue repair (5–7). Emerging evidence implicates IGF2

dysregulation in the pathogenesis of several kidney disorders,

including acute kidney injury (AKI) (8), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (9) and renal malignancies (10). Through interactions with receptors

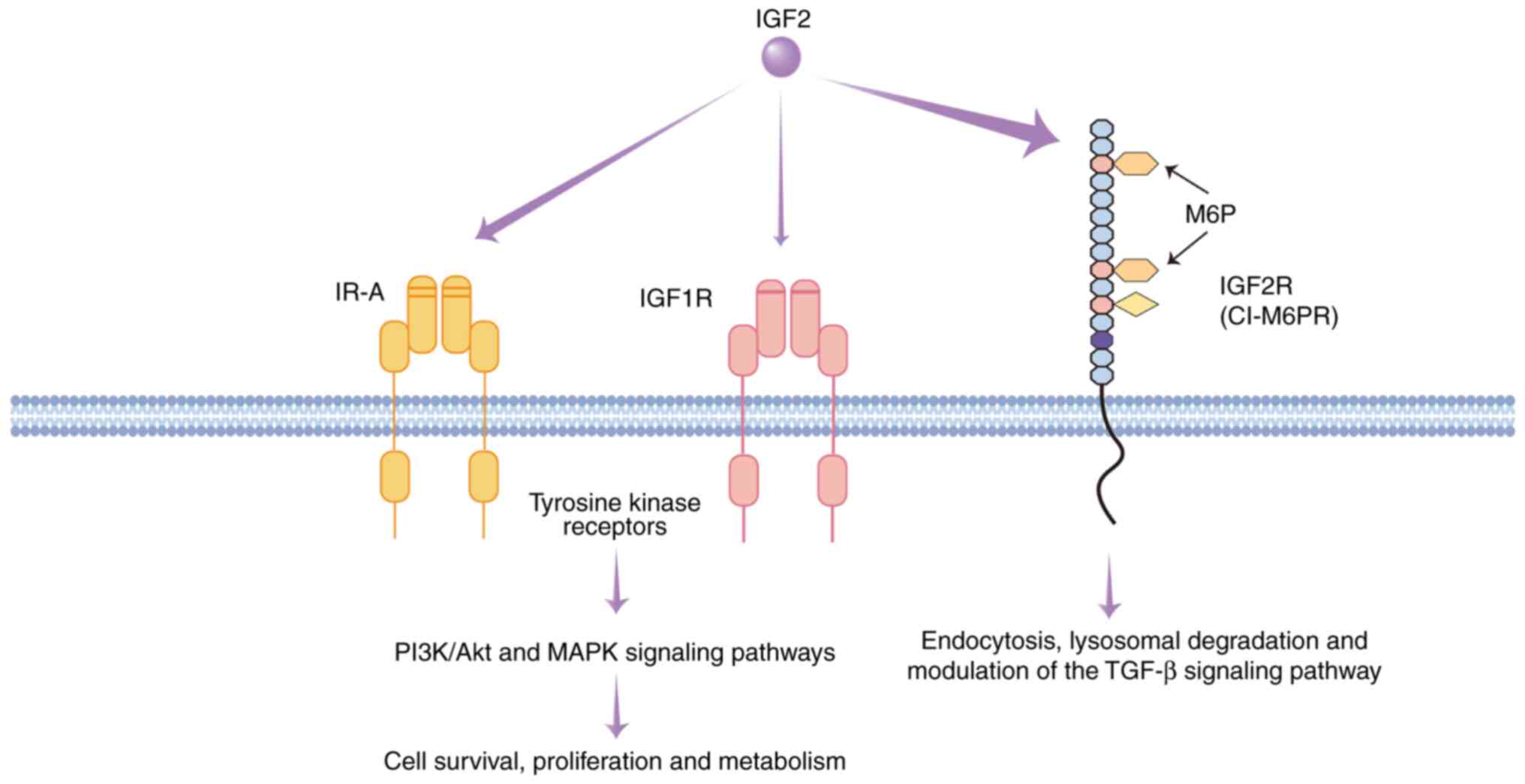

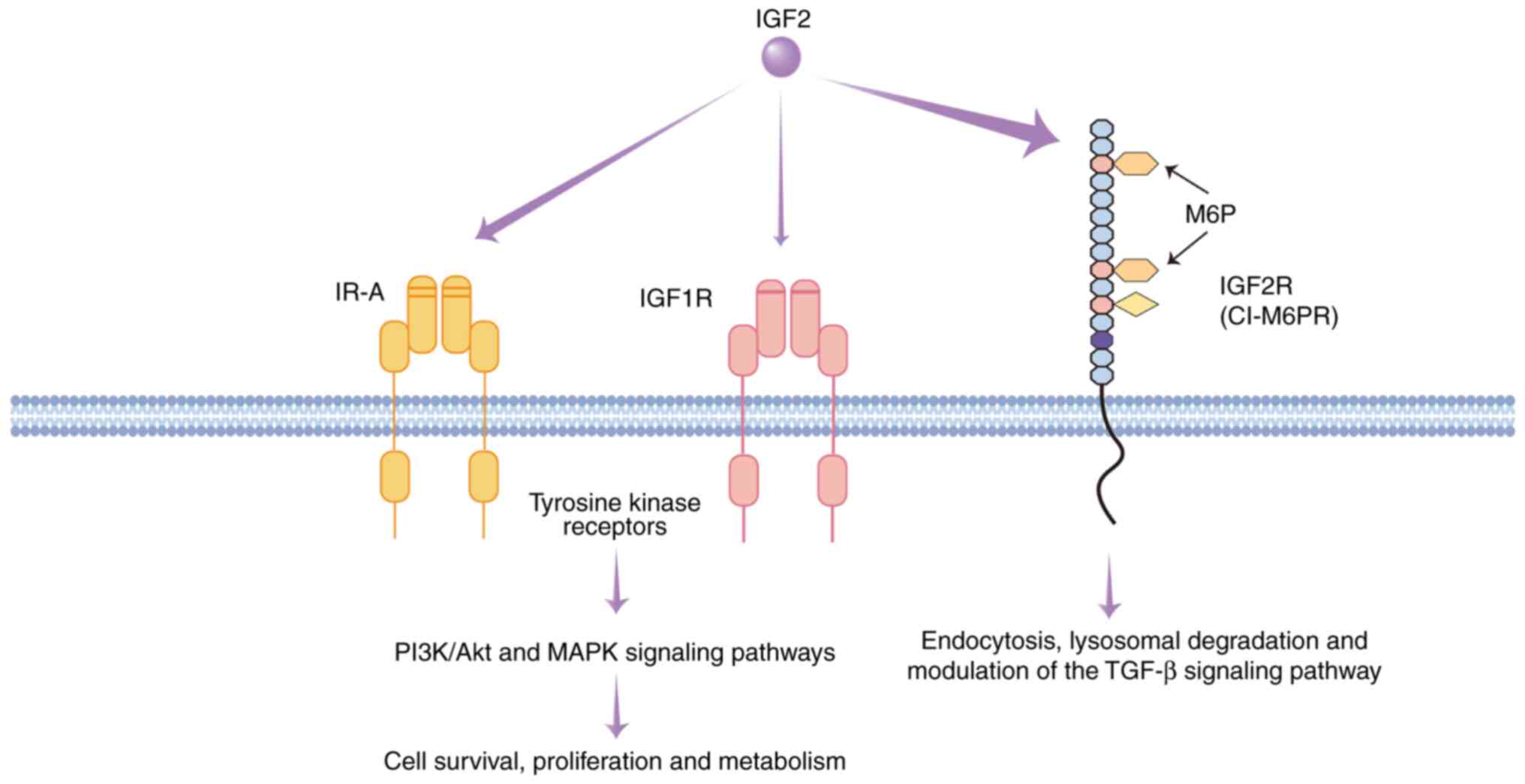

such as IGF1 receptor (IGF1R), insulin receptor isoform A (IR-A)

and IGF2 receptor (IGF2R), IGF2 activates signaling pathways,

including the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, that modulate

inflammation, fibrosis and cell survival (11,12)

(Fig. 1). The present review

summarizes the structural characteristics and biological functions

of IGF2, its regulatory mechanisms and its involvement in kidney

diseases, highlighting its potential as both a diagnostic biomarker

and a therapeutic target.

| Figure 1.IGF2-mediated signaling pathways and

the functional roles of IGF receptors. This schematic illustrates

the interactions between IGF2 and its primary receptors: IR-A,

IGF1R and IGF2R (CI-M6PR). The arrow thickness indicates the

relative binding affinity. IR-A and IGF1R are tyrosine kinase

receptors. Upon IGF2 binding, they activate the PI3K/Akt and MAPK

signaling pathways, promoting cell survival, proliferation and

metabolic regulation. By contrast, IGF2R lacks signaling capability

and primarily functions to internalize and target IGF2 for

lysosomal degradation, thus regulating its bioavailability. It also

transports M6P-tagged proteins and modulates the TGF-β pathway,

influencing extracellular matrix dynamics and tissue homeostasis.

IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGF1R/IGF2R, IGF1/2 receptor;

CI-M6PR, cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor; IR-A,

insulin receptor isoform A. |

Structure and physiological function of

IGF2

IGF2, a polypeptide hormone, has a similar action as

insulin, yet its biological activity is low (approximately 14% of

that of insulin) (13). The IGF2

gene is located on human chromosome 11p15.5 and spans ~30 kb of

genomic DNA. It encodes a 7.5-kDa peptide comprising 67 amino acid

residues and shares ~67% sequence homology with insulin-like growth

factor 1 (IGF1) (14).

IGF2 is widely expressed in embryonic and fetal

tissues, although transcript levels vary considerably across

different organs (15). The gene

is regulated by five distinct promoters (P0-P4) and consists of 10

exons, with only the final three exons encoding protein-coding

sequences (15,16). These promoters are differentially

regulated in a tissue- and developmental stage-specific manner,

giving rise to functionally distinct mRNA isoforms (16,17).

Each promoter is functionally active at specific stages of

development and in distinct tissue types. For example, the P0

promoter is predominantly active in the placenta and serves a role

in determining placental size and composition. Loss of P0 promoter

activity reduces passive diffusion across the placenta, resulting

in fetal growth retardation, although systemic levels of fetal IGF2

remain unaffected. This observation suggests that placental IGF2

expression operates independently of circulating IGF2 levels

(18).

The P1 promoter is primarily active in the adult

liver and the choroid plexus of the brain and contains an internal

ribosomal entry site (16). P2 is

mainly active in the fetal liver, whereas P3 and P4 drive

expression in non-hepatic fetal and adult tissues. Notably, P3 and

P4 are epigenetically silenced after birth but may be reactivated

in certain tumors [including Wilms' tumor (19) and rhabdomyosarcoma] (20,21).

Both P3 and P4 contain canonical TATA and CCAAT boxes recognized by

RNA polymerase II, while P2 lacks these elements (22). Transient transfection assays have

demonstrated that the activity of P2, P3 and P4 varies by cell type

and species. For example, P2 is minimally active in most cell

lines, whereas P3 exhibits the highest transcriptional activity in

hepatocyte-derived human cells (23). Overall, IGF2 transcription declines

sharply in most tissues after birth (16).

IGF2 serves an important role in tissue development

and growth, particularly during embryogenesis (24). The biological functions of IGF2 are

primarily mediated through interactions with three specific

receptors: IGF1R, IR-A and IGF2R (11,12).

IGF1R is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor structurally

related to the insulin receptor (IR) (9,19,25).

Upon binding IGF2, IGF1R activates the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling

cascades, thereby promoting cell proliferation, differentiation and

survival, which are processes that are important for embryonic

tissue and organ formation (11,26).

IGF1R signaling also serves a central role in tumor biology by

enhancing cell survival via anti-apoptotic mechanisms, particularly

in IGF1R-dependent malignancies (27).

Compared with IGF1R, IR-A has a higher binding

affinity for IGF2 and is predominantly expressed in fetal tissues

and specific cancer types, including colorectal cancer,

osteosarcoma and thyroid cancer (23,28,29).

Upon binding to IGF2, IR-A activates the PI3K/Akt and MAPK

pathways, regulating cell metabolism, proliferation and survival,

and contributing to tumor growth and adaptability (30–32).

Under specific pathological conditions, such as tumors that

excessively secrete IGF2, notably including mesenchymal tumors and

hepatocellular carcinomas, IGF2 can induce hypoglycemia by

activating the IR-A signaling pathway. The aforementioned tumor

cells commonly highly express IGF2 mRNA (33–35).

However, defective post-translational processing leads to the

production of a high molecular weight precursor (15–25 kDa),

referred to as pro-IGF2 or ‘big IGF2’, characterized by an

uncleaved E-domain extension (36–38).

Under physiological conditions, mature IGF2 circulates primarily as

part of a 150-kDa ternary complex with IGF-binding protein

(IGFBP)-3 and the acid-labile subunit (ALS). This large complex is

unable to cross the capillary endothelium, thereby limiting its

biological activity (36,38).

By contrast, pro-IGF2 binds to IGFBP-2 or IGFBP-3 to

form a smaller (~50 kDa) binary complex. Steric hindrance from the

uncleaved E-domain prevents ALS binding, thereby impeding the

formation of the ternary complex. Due to its reduced molecular

weight, the binary complex can freely diffuse across the capillary

endothelium into the interstitial fluid (37). A clinical study demonstrated that

serum concentrations of the 50-kDa complex in patients with tumors

can be elevated >10-fold compared with normal levels, enhancing

its tissue distribution (37).

Additionally, pro-IGF2 promotes vascular leakage and tissue

penetration by stimulating tumor secretion of VEGF and MMP-9. VEGF

increases vascular permeability, while MMP-9 degrades the basement

membrane and disrupts endothelial junctions (39,40).

Furthermore, tumor-associated neovasculature is often characterized

by incomplete basement membranes and loosely connected endothelial

cells, creating a ‘leaky’ vascular phenotype that facilitates the

extravasation of small molecular complexes (41).

Once within the interstitial fluid, pro-IGF2 retains

receptor-binding affinities to both IR and IGF1R similar to mature

IGF2 but exhibits 2- to 3-fold greater molar bioactivity, leading

to prolonged receptor activation (36,37).

Consequently, in patients with extra-pancreatic tumor-induced

hypoglycemia, circulating pro-IGF2 levels are markedly elevated and

typically normalize following successful tumor resection (42).

The biological effects of ligand binding are notably

influenced by receptor subtype. For instance, in 32D clone 3 murine

hematopoietic progenitor cells, IGF2 binding to IR-A induces

pro-mitotic and anti-apoptotic signaling, whereas its binding to

IR-B promotes differentiation (43). In mouse fibroblasts expressing

exclusively IR-A, insulin binding elicits metabolic responses

(44).

In contrast to IGF1R, IGF2R exhibits distinct

structural and functional characteristics and has the highest

binding affinity for IGF2. IGF2R is a single-chain transmembrane

receptor that lacks intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity and

primarily mediates IGF2 degradation via endocytosis, thereby

suppressing cellular over-proliferation and reducing tumorigenic

potential (45–47). Additionally, IGF2R facilitates

lysosomal enzyme trafficking by recognizing mannose-6-phosphate

residues and is therefore also referred to as the

cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (46). This function is evolutionarily

conserved, and mammalian IGF2R has further acquired the capacity to

bind IGF2, thereby enhancing its role in limiting cell

proliferation (48). IGF2R also

modulates the TGF-β signaling pathway, which is involved in

extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis, immune regulation, and the

control of cell proliferation, differentiation and development

(49,50). Collectively, these properties allow

IGF2R to maintain growth homeostasis under physiological

conditions, and inhibit tumorigenesis and progression under

pathological conditions (51).

Despite advances in deciphering the complex

structure and regulatory mechanisms of IGF2, such as its genomic

imprinting and the existence of multiple promoters and isoforms

(52,53), the role of IGF2, particularly in

renal physiology and pathology, remains to be fully elucidated. The

present review focuses on the expression, regulation and function

of IGF2 in the kidney, summarizing its contributions to renal

development and its involvement in kidney disease.

Role of IGF2 in the development and

functional maintenance of the kidney

IGF2 serves a notable role in renal development and

the maintenance of kidney function by regulating cellular

proliferation, differentiation and metabolic homeostasis (5). IGF2 expression exhibits a distinct

spatiotemporal pattern aligned with specific physiological

functions across developmental stages (23,54–56).

During embryogenesis, IGF2 is highly expressed and

is important for normal renal morphogenesis (57,58).

At this stage, IGF2 is primarily secreted by the placenta (6) and exhibits strong expression in renal

structures, particularly the ureteric bud and metanephric

mesenchyme (7). This elevated

expression facilitates nephron formation by promoting the

mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition of nephrogenic progenitors,

driving the development of renal tubules and glomeruli, and

directing mesodermal cell differentiation toward functionally

specialized nephron segments (7,24,59).

Animal studies have supported the important role of IGF2 during

this period: Disruption of IGF2 signaling leads to notably reduced

birth weight, whereas overexpression results in accelerated somatic

growth (45,60,61).

Furthermore, intrauterine growth restriction models have

demonstrated that aberrant DNA methylation of the IGF2 promoter

reduces its expression, lowers nephron endowment and increases the

risk of CKD later in life (7),

underscoring the importance of tightly regulated IGF2 expression

during renal development.

As renal development reaches completion, IGF2

expression is downregulated (62).

In the adult kidney, IGF2 is maintained at basal levels and is

primarily localized to vascular structures and interstitial cells

surrounding the glomeruli and renal tubules (57,63).

IGF2 mRNA exhibits a spatially restricted pattern: It is enriched

in the vascular components of the cortex, particularly within the

endothelium and adventitia of afferent arterioles, while in the

medulla, it is predominantly expressed in vascular and stromal

compartments, with negligible expression in tubular epithelial

cells (5). This distribution

suggests a specialized role for IGF2 in regulating renal

vasculature and glomerular function. Basal IGF2 also contributes to

renal homeostasis by supporting cellular repair and metabolic

balance (63–65). The transition from high embryonic

IGF2 expression to adult basal levels appears to be epigenetically

regulated, particularly via promoter methylation, ensuring

structural and functional stability post-development (8). Notably, a study using IGF1-deficient

transgenic mouse models showed that kidney-specific overexpression

of IGF2 selectively increased both absolute and relative kidney

weight, without altering body weight or the mass of other organs

(66). These findings support a

unique, organ-specific role for IGF2 in kidney growth, development

and homeostatic maintenance, spanning from embryonic morphogenesis

to adult physiological function.

The biological effects of IGF2 are primarily

mediated via its interaction with IGF1R and IR (67). IGF1R, the primary signaling

receptor for IGF2, is widely distributed in the kidney, with

prominent expression in renal tubules, glomeruli and mesangial

cells (68). The expression of

IGF1R is particularly high in proximal and distal tubular segments,

underscoring the role of IGF2 in regulating metabolic processes and

ion transport in these structures (5). IGF2 promotes the proliferation and

differentiation of renal precursor cells predominantly through

IGF1R activation, thus contributing to the formation of renal

tubules and glomeruli (69). In a

mouse model with P2 promoter deletion, resulting in reduced IGF2

expression, pronounced renal abnormalities were observed,

manifesting as proteinuria, podocyte depletion, glomerulosclerosis,

increased ECM deposition and glomerular basement membrane

thickening at 18 months of age (70). These findings emphasize the

importance of IGF2 in supporting renal architecture and maintaining

nephron functionality, primarily through its role in podocyte

health. The observed increase in ECM deposition is a secondary,

dysregulated consequence of podocyte injury and loss, manifesting

as mesangial expansion and glomerulosclerosis (70). Furthermore, IGF1R activation

promotes ECM synthesis in renal tubules, thereby supporting the

structural integrity and functionality of renal tissues (71).

IR is another important receptor for IGF2. Although

IR primarily regulates glucose metabolism, it is also widely

expressed in the kidney (72). In

renal tubules and glomerular endothelial cells, IR expression is

high and contributes to the regulation of renal blood flow and

tubular reabsorption functions (73). Compared with IGF1R, IR displays a

more uniform distribution across kidney regions, suggesting a

broader role in maintaining renal metabolic homeostasis (74). Additionally, IGF2 may influence

ionic transport and water-electrolyte balance in the kidney via IR

signaling. An in vitro study has shown that IGF2 expression

enhanced sodium uptake in proximal tubular brush border membrane

vesicles (65).

Unlike IGF1R and IR, IGF2R lacks intrinsic kinase

activity, and is traditionally regarded as a decoy receptor

involved in IGF2 internalization and degradation (75). However, a previous study has

revealed that IGF2R may serve an active signaling role. IGF2R

nuclear translocation has been linked to GSK3, which primes

macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. These findings

reveal a novel immunomodulatory role for IGF2R in macrophages and

suggest that IGF2 may influence immune responses within the kidney

via IGF2R. Notably, activation of IGF1R, by either IGF1 or IGF2,

can antagonize IGF2R signaling, thereby modulating macrophage

polarization. The balance between IGF1R and IGF2R activation is

important for maintaining macrophage-mediated immune homeostasis

and appropriately shaping the immune response to infection or

inflammation (76).

Understanding the regulatory mechanisms governing

IGF2 expression is important for elucidating its roles in renal

development and disease. IGF2 expression is controlled by genomic

imprinting, with transcription occurring exclusively from the

paternal allele while the maternal allele remains epigenetically

silenced (77,78). This monoallelic expression pattern

is maintained by DNA methylation at the H19/IGF2 imprinting control

region (ICR) and its associated epigenetic regulatory elements

(79,80). Specifically, paternal-specific

methylation of the ICR, enhancer competition and CCCTC-binding

factor-mediated boundary insulation ensure the spatial and temporal

precision of IGF2 function during renal development (81).

Loss of genomic imprinting is associated with

pathological growth abnormalities. For example, Beckwith-Wiedemann

syndrome is caused by IGF2 upregulation and is characterized by

somatic overgrowth of the body, including kidney overgrowth

(61). Conversely, Silver-Russell

syndrome involves IGF2 downregulation and presents with growth

restriction of body and the kidneys are generally small in

proportion to the overall body growth restriction (82). Experimental models further

underscore the important role of imprinting in renal development.

These include the model demonstrating that CTCF mediates

methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2

locus, where it binds the unmethylated imprinting control region

(ICR) on the maternal allele to insulate Igf2 from enhancers,

thereby silencing it (79), and

the model of aberrant establishment of paternal methylation imprint

at the H19/Igf2 ICR, which disrupts the parent-of-origin-specific

expression pattern (83,84). In both cases, enhancer deletion at

the 3′ end of the H19 gene and demethylation of ICR alter IGF2

expression and impair normal kidney development (85).

Role of IGF2 in kidney disease

Above studies suggest a potential pathogenic and

therapeutic role for IGF2 in diverse renal disorders, and highlight

the need for further investigation into IGF2 signaling pathways and

receptor interactions in the kidney to advance early diagnosis,

therapeutic strategies and targeted interventions for renal

pathologies. The following section explores the effects of IGF2

administration or overexpression in experimental models of renal

disease.

IGF2 modulates renal physiology and pathology via a

complex receptor network, including IGF2R, IGF1R and IR-A, and

downstream signaling pathways such as the PI3K/Akt, MAPK and GSK3

pathways, exhibiting a biphasic regulatory pattern (76,86).

Under physiological conditions, IGF2 predominantly interacts with

IGF2R, activating the GSK3 signaling pathway and inducing the

epigenetic reprogramming of macrophages (8,76).

This promotes a metabolic shift toward oxidative phosphorylation

(OXPHOS), fosters a macrophagic anti-inflammatory phenotype

(76,87). In parallel, IGF2 signaling supports

the proliferation of renal tubular epithelial cells, thereby

contributing to podocyte cytoskeletal integrity and renal tissue

repair (70,88).

By contrast, under pathological conditions,

including chronic inflammation, hyperglycemia or loss of genomic

imprinting, IGF2 preferentially binds IGF1R and IR-A, leading to

sustained activation of the PI3K/Akt-MAPK axis. This signaling

cascade disrupts the integrity of the podocyte-slit diaphragm

complex and, in synergy with TGF-β1, stimulates collagen deposition

and promotes irreversible renal fibrosis (70,89).

Furthermore, in contexts involving biallelic IGF2 expression,

persistent pro-proliferative signaling may ensue, contributing to

proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis and the malignant transformation of

renal tissues (90). This

receptor-dependent shift in IGF2 signaling cascades represents a

central molecular mechanism that governs renal cell fate decisions

under both homeostatic and pathological states.

Role of IGF2 in AKI

AKI is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome that is

characterized by a sudden decline in the glomerular filtration rate

(GFR), commonly indicated by elevated serum creatinine (SCr) levels

and/or oliguria (91). The

incidence of AKI among hospitalized patients is ~20% and is often

associated with complications such as fluid retention, electrolyte

imbalances, uremic symptoms and drug-induced nephrotoxicity

(91).

Traditionally, ischemia-reperfusion injury,

nephrotoxic insults and sepsis have been regarded as the primary

causes of AKI (91). However,

growing evidence suggests that modifiable lifestyle factors

influence both the onset and progression of AKI. Chronic alcohol

consumption exacerbates AKI, increases the vulnerability and

severity of kidney (92,93). Cigarette smoking impairs renal

perfusion by inducing systemic inflammation, oxidative stress and

endothelial dysfunction (94).

Diets high in sodium, saturated fats and processed foods are

strongly linked to hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular

disease, which are chronic metabolic conditions that are

established risk factors for AKI (95,96).

These findings underscore the multifactorial pathogenesis of AKI

and highlight the need for integrative prevention strategies

addressing both clinical and lifestyle-related risk factors.

At the molecular level, IGF2 may emerge as a

potential key modulator of immune response and tissue repair during

acute kidney injury (AKI). Although direct evidence elucidating the

role of IGF2 in AKI remains limited, the well-documented functions

of its related family member IGF-1 and other growth factors,

including FGF2, in renal repair processes have been established

(97,98). Mechanistically, it is proposed that

IGF2 binds to its receptor IGF2R on macrophages, activating the

GSK3β/β-catenin pathway to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines,

such as TNF-α and IL-1β, and enhance anti-inflammatory markers,

such as arginase-1 and IL-10, thereby reshaping the immune

microenvironment to attenuate renal injury (76). Furthermore, following

ischemia-reperfusion injury, IGF2 expression is transiently

upregulated and contributes to tubular epithelial cell repair

(99). Animal studies have further

demonstrated that IGF2R agonist administration reduced tubular

necrosis by 42% and macrophage infiltration by 57%, underscoring

the protective role of IGF2 in AKI (8,76).

IGF2 signaling has also shown promise as a clinical

biomarker. The combined urinary detection of IGFBP-7 and tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 exhibits high predictive accuracy

for AKI (area under the curve, 0.80), supporting the translational

potential of IGF2-related mechanisms (100). Mesenchymal stem and/or stromal

cells mediate part of their renoprotective effects via IGF2. Under

hypoxic or inflammatory conditions, MSCs exhibit a 3.5- to 5.2-fold

increase in IGF2 secretion, promoting macrophage polarization

toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (8). IGF2 also facilitates macrophage

metabolic reprogramming from glycolysis to mitochondrial OXPHOS,

enhancing ATP production and sustaining the anti-inflammatory

activity of the macrophages (8).

However, IGF2 is not the sole mediator of MSC-induced renal

protection. Knockdown of IGF2 partially attenuates, but does not

abolish, MSC-mediated protection, suggesting compensatory roles for

other factors such as hepatocyte growth factor, VEGF and exosomal

microRNAs (97,101). Furthermore, although hypoxia

preconditioning enhances MSC-derived IGF2 expression in

glycerol-induced AKI models, it does not significantly improve

therapeutic efficacy compared with unconditioned MSCs, highlighting

the importance of multifactorial synergy (8).

A specific subtype of AKI, aristolochic acid

nephropathy (AAN), results primarily from aristolochic acid I (AAI)

exposure, and is characterized by AKI, interstitial nephritis and

metabolic dysfunction (102,103). AA forms covalent adducts with DNA

or RNA, driving the progression of renal damage (104), with ischemic injury forming a

central pathophysiological basis (105). It is therefore plausible that AA

may interfere with IGF2 signaling through spatially specific

mechanisms. Histological analyses have demonstrated that AA

primarily targets the renal cortex, where it induces DNA adducts,

such as 7-(deoxyadenosine-N6-yl) aristolactam (dA-AAI), in proximal

tubular cells, leading to epigenetic silencing of IGF2 through

aberrant DNA methylation and disruption of ICRs (106,107). Spatial transcriptomics analysis

has revealed that AA exposure activates the TGF-β/SMAD pathway in

cortex-localized injured tubular clusters. This process promotes

the establishment of a pro-inflammatory microenvironment

characterized by macrophage infiltration and CCL5/CCR5 axis

activation (108) and may

potentially represses IGF2 transcription via SMAD3/NF-κB

co-regulation (107,109,110).

Although the intense oxidative stress induced by

aristolochic acid (AA) has been established as a core mechanism of

its nephrotoxicity, the upstream drivers of this process require

further investigation (107,111–114). Based on the well-documented role

of the xanthine oxidoreductase system as a key source of reactive

oxygen species (ROS) in renal injury (115,116), a plausible scientific hypothesis

may be proposed: AA may activate this pathway by triggering ‘purine

metabolic reprogramming’ in the renal cortex. Specifically, it may

be postulated that AA or its metabolites may upregulate the

expression or activity of xanthine dehydrogenase, leading to the

accumulation of its substrates (xanthine) and products (uric acid),

which in turn results in a burst of ROS production and ATP

depletion. This metabolic disruption may further suppress the

expression of critical repair signals like IGF2 through epigenetic

mechanisms, thereby forming a self-reinforcing ‘vicious cycle’ with

persistent inflammation and fibrosis (8,76).

Although this hypothesis still requires direct experimental

validation, studies have suggested the protective efficacy of

targeting this pathway, providing a theoretical foundation for

exploring its therapeutic potential in aristolochic acid

nephropathy (117,118).

Role of IGF2 in CKD

CKD is a progressive disorder that constitutes a

notable global health burden, affecting >10% of the global

population, ~800 million individuals (119). Over the past 2 decades, both its

incidence and mortality have steadily increased, positioning CKD as

one of the leading non-communicable causes of death worldwide

(119). IGF2 serves an important

role in renal development and functional maintenance, and its

dysregulation is increasingly implicated in CKD pathogenesis,

particularly in fibrotic remodeling and tubulointerstitial injury

(53,70,89)

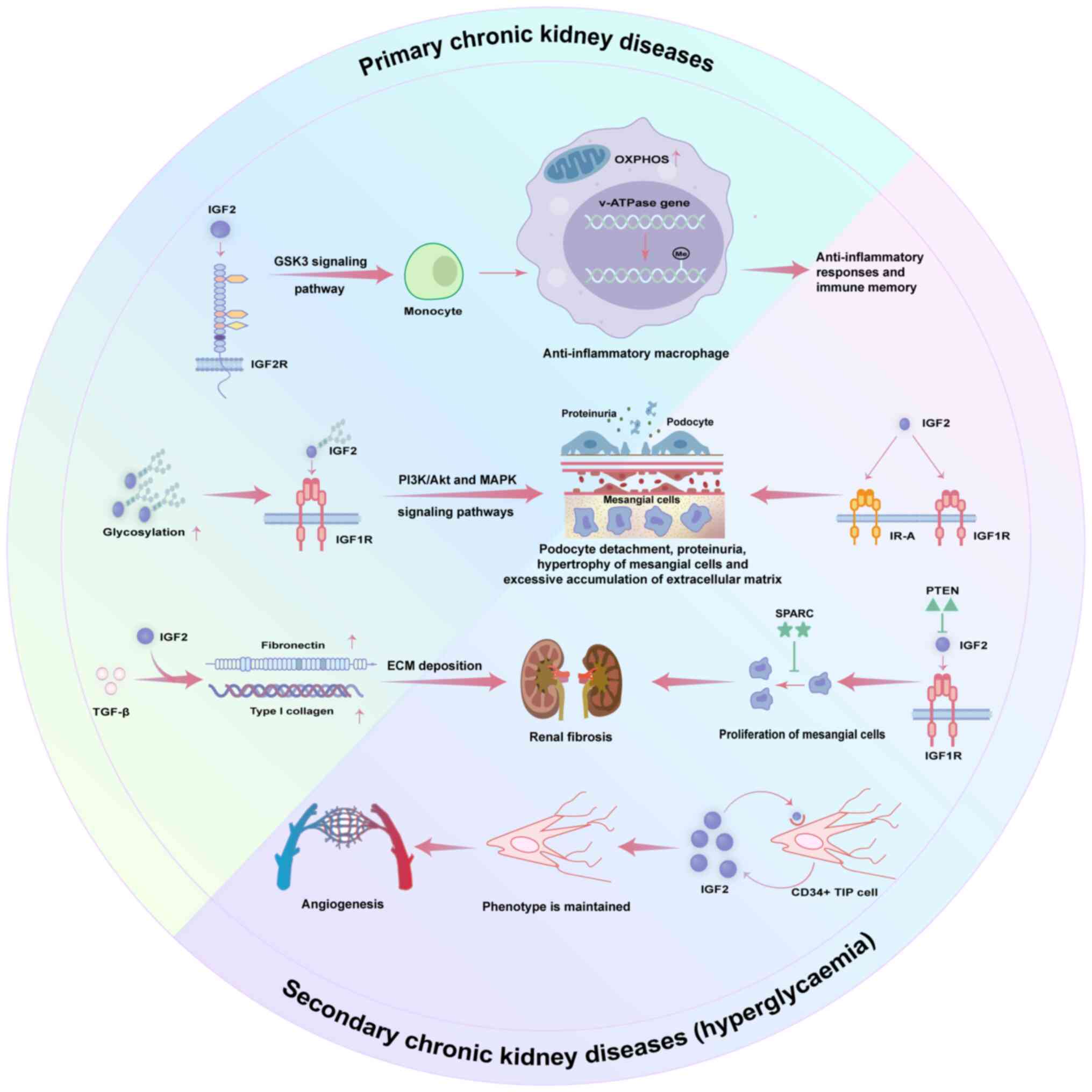

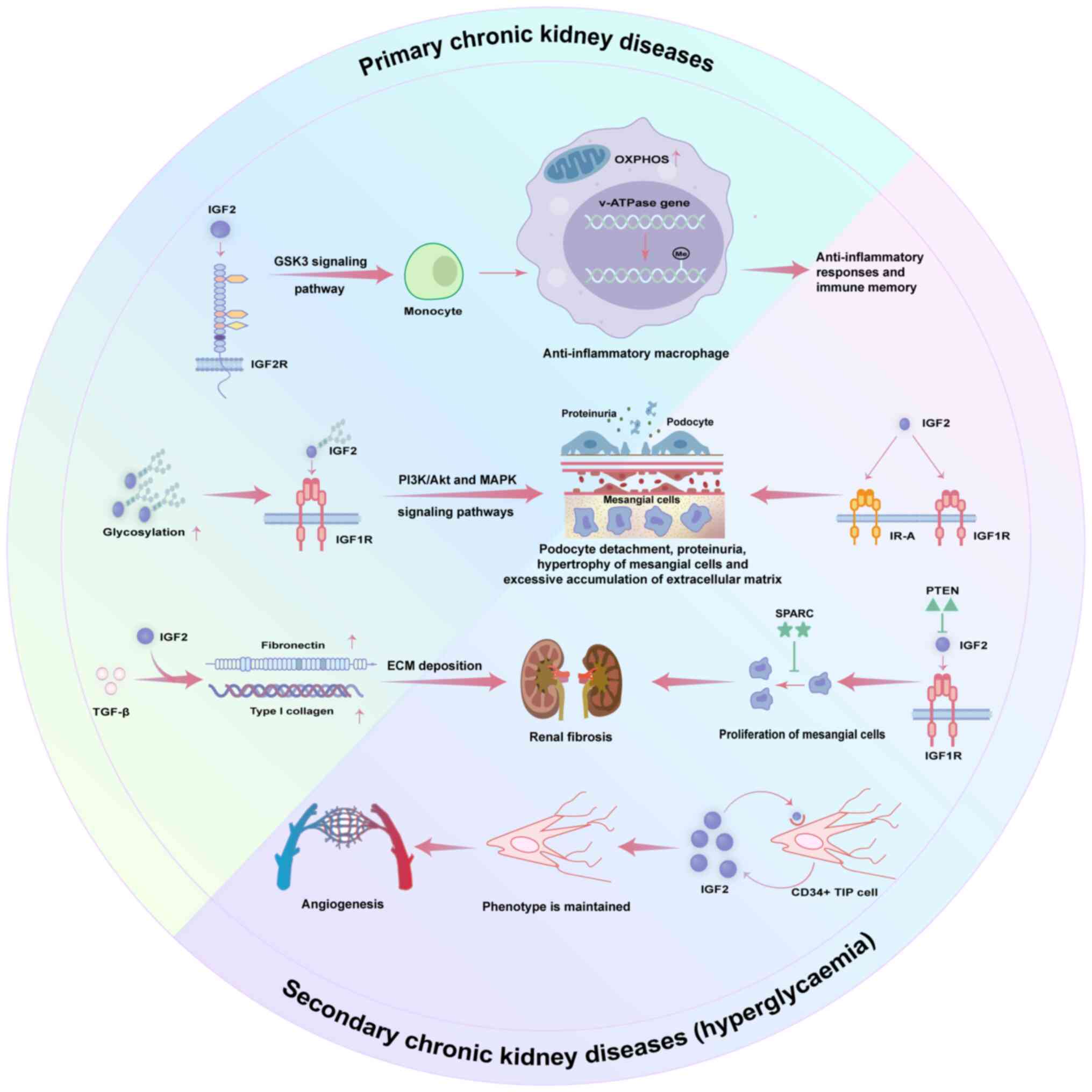

(Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Role of IGF2-mediated signaling

pathways in CKD. This figure delineates the dual roles of IGF2

signaling in CKD, encompassing both primary and

hyperglycemia-induced secondary mechanisms. In primary CKD, IGF2

binding to IGF1R activates PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, promoting

podocyte detachment, mesangial cell hypertrophy and excessive ECM

accumulation, ultimately compromising glomerular filtration barrier

integrity. Furthermore, IGF2 synergizes with TGF-β to upregulate

fibronectin and type I collagen, accelerating renal fibrosis.

Conversely, signaling through IGF2R activates the GSK3 pathway,

inducing anti-inflammatory macrophage differentiation and

modulating mitochondrial metabolism, which may confer protective

effects. In hyperglycemia-induced CKD, IGF2 binding to IGF1R and

IR-A drives pathological mesangial cell proliferation and ECM

accumulation. This process is exacerbated by loss of PTEN-mediated

negative feedback. Concurrently, SPARC is upregulated as a

compensatory repair mechanism. Additionally, hyperglycemia enhances

autocrine IGF2 secretion by CD34+ TIP cells, facilitating phenotype

maintenance and angiogenesis. These findings underscore the

multifaceted role of IGF2 in CKD pathophysiology, highlighting its

potential as a therapeutic target. IGF, insulin-like growth factor;

CKD, chronic kidney disease; IGF1R/IGF2R, IGF1/2 receptor; OXPHOS,

oxidative phosphorylation; v-ATPase, vacuolar-type ATPase; TIP

cell, tip endothelial cell; SPARC, secreted protein acidic and rich

in cysteine; IR-A, insulin receptor isoform A; ECM, extracellular

matrix; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10. |

Primary CKD

In the context of primary CKD, IGF2 acts as an

important modulator of disease progression by influencing ECM

deposition, tubular dysfunction and fibrosis via activation of the

PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways (71,89).

Clinical data reveal that serum IGF2 levels are elevated in

patients with chronic renal failure compared with healthy controls,

a finding likely attributable to impaired renal clearance. Notably,

serum IGF2 levels remain unchanged following hemodialysis, whereas

urinary excretion of IGF2 increases, suggesting a compensatory

clearance mechanism mediated by residual nephrons (120). Urinary proteomic analysis has

further identified elevated levels of glycosylated IGF2 in patients

with CKD, with this form exhibiting an inverse association with

estimated GFR, highlighting its potential utility as a biomarker

for disease progression and therapeutic monitoring (121).

Under physiological conditions, IGF2 supports

podocyte survival and cytoskeletal integrity. However, aberrant

IGF2 activation disrupts this homeostasis, leading to podocyte

detachment and glomerular filtration barrier dysfunction. Podocyte

injury thus becomes a central mechanism contributing to proteinuria

and glomerulosclerosis (71,89).

Additionally, IGF2 synergizes with TGF-β1 to enhance expression of

fibrogenic mediators such as type I collagen and fibronectin,

thereby promoting irreversible glomerular and tubulointerstitial

fibrosis (89).

IGF2 also facilitates tubular regeneration during

the early stages of CKD by promoting epithelial cell proliferation

and repair (9). This duality

underscores its context-dependent effects and highlights the

potential of IGF2 as a therapeutic target in CKD, although its

precise roles in fibrotic vs. reparative processes warrant further

exploration.

Persistent low-grade inflammation is a hallmark of

CKD, with macrophage activation and functional plasticity serving a

central role in disease progression (53). A previous study has demonstrated

that IGF2 activates GSK3 signaling through IGF2R, triggering

epigenetic reprogramming of macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory

phenotype (8,76). Specifically, IGF2 suppresses

lysosomal acidification by enhancing DNA methylation of the

vacuolar-type H-ATPase gene, thereby altering macrophage energy

metabolism. This reprogramming favors OXPHOS over glycolysis as the

dominant energy source, which contrasts with the classical Warburg

effect observed in inflammatory macrophages and tumor cells

(122–124). Additionally, this reprogramming

enables macrophages to exert anti-inflammatory responses and

develop immune memory. These findings reinforce the importance of

IGF2 as both a metabolic and immunological regulator in CKD.

Patients with CKD frequently exhibit persistent

low-grade immune activation, involving macrophage immunological

memory and phenotypic plasticity (125–127). IGF2 has been shown to enhance

this form of ‘trained immunity’, enabling macrophages to respond

more effectively to subsequent inflammatory stimuli with an

anti-inflammatory profile (8).

This process is especially relevant in CKD, where it helps

attenuate disease progression by maintaining immune homeostasis and

preventing excessive chronic inflammation (128,129).

Secondary CKD

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the most common

complications of diabetes mellitus and a notable cause of CKD

worldwide (130). Hallmark

pathological features of DN include renal hypertrophy, mesangial

expansion, excessive accumulation of ECM, tubular atrophy and

interstitial fibrosis (131). A

clinical study has demonstrated that serum levels of IGF2 are

elevated in the early stages of DN, including the microalbuminuria

phase, ~30% higher than in patients with diabetes alone, and are

positively associated with cystatin C and 24-h urinary protein

excretion (132). In advanced

stages marked by overt proteinuria, IGF2 levels further increase

≤1.5-fold compared with those of healthy controls, and show

positive associations with SCr and blood urea nitrogen levels,

indicating a potential role of IGF2 in the development of

glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis (132,133). While IGF2 serves a physiological

role in angiogenesis and tissue repair, its upregulation under

hyperglycemic conditions contributes to the pathogenesis of DN

(99,132).

IGF2 expression is markedly upregulated in diabetic

kidneys (134). Through

activation of IGF1R and IR-A, IGF2 induces abnormal glomerular cell

proliferation and promotes ECM deposition, resulting in

glomerulosclerosis and compromising glomerular filtration barrier

integrity (135). These changes

not only impair renal structure and function but also accelerate DN

progression (136,137).

In addition to its effects on glomerular cells, IGF2

regulates the balance between renal injury and repair by

interacting with key signaling pathways, notably the phosphatase

and tensin homolog on chromosome 10 (PTEN) and secreted protein

acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) pathways. PTEN functions as a

negative regulator of the insulin/IGF signaling pathway and serves

an important role in DN, particularly in the hyperglycemic

microenvironment (137,138). A study has demonstrated that

IGF2, PTEN and SPARC are all upregulated in renal biopsies from

patients with early-stage DN (137). When PTEN-mediated negative

feedback is impaired, IGF2 activity increases, exacerbating

pathological mesangial cell proliferation, ECM accumulation and

renal fibrosis (136). This

mechanism has been corroborated in streptozotocin-induced diabetic

rat models (139,140).

SPARC, a matricellular protein involved in tissue

remodeling and repair, is also modulated in DN. In DN, SPARC

inhibits mesangial cell hypertrophy. While its upregulation may

reflect a compensatory response to hyperglycemic injury, decreased

SPARC expression is associated with impaired renal repair

mechanisms, thereby worsening disease progression (141,142). Thus, in DN, IGF2 modulates renal

injury and repair via interactions with PTEN and SPARC,

highlighting a dual regulatory axis in disease pathophysiology.

IGF2 serves an important role in angiogenesis. In

a vitro study using CD34+ tip endothelial cell (TIP

cell) models has revealed a strong association between IGF2

expression and both the number and angiogenic capacity of these

cells. IGF2 knockdown reduces CD34+ TIP cell numbers and

inhibits vascular sprouting, supporting its role in angiogenic

regulation. These findings also suggest that IGF2 may sustain the

TIP cell phenotype via autocrine signaling (143). Therefore, targeted inhibition of

IGF2 signaling may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for

delaying DN progression by disrupting aberrant angiogenesis and

fibrotic remodeling.

Role of IGF2 in renal tumors

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC)

RCC is a prevalent renal malignancy characterized by

complex genetic and epigenetic alterations. One of the notable

molecular changes implicated in RCC is the upregulation of IGF2,

particularly through loss of imprinting (LOI), which results in

biallelic expression of the IGF2 gene. This aberrant expression

contributes to tumor initiation and progression by activating

multiple oncogenic signaling pathways (10).

A key regulatory mechanism involves the long

non-coding RNA HOXA transcript at the distal tip, which acts as a

competing endogenous RNA by sponging microRNA-615, thereby

relieving repression of IGF2 and leading to its upregulation. This

promotes renal cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion

(144). Within the tumor

microenvironment, IGF2 interacts with IGF1R and IR-A to activate

the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, which enhance tumor cell survival,

proliferation and motility (26,27).

The oncogenic potential of IGF2 is markedly enhanced in tumors with

high IR-A expression, underscoring the importance of receptor

context in determining tumor behavior (17).

Preclinical models further support the role of IGF2

in RCC progression. In mouse models, IGF2 overexpression has been

shown to accelerate tumor cell proliferation and metastasis,

suggesting that therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting IGF2

signaling or blocking receptor interactions may hold promise for

targeted antitumor therapy in RCC (145–148).

Wilms' tumor

Wilms' tumor, or nephroblastoma, is a pediatric

embryonal renal neoplasm arising from undifferentiated renal

precursor cells. It is associated with epigenetic dysregulation of

the IGF2 gene, particularly the loss of maternal imprinting, which

leads to biallelic IGF2 expression and abnormal cellular

proliferation (149).

During normal fetal kidney development, IGF2 is

expressed exclusively from the paternal allele. All four known IGF2

promoters (P1-P4) maintain monoallelic expression in early

development; however, imprinting at the P1 promoter begins to relax

between gestational weeks 15–17 (150). In Wilms' tumor, this relaxation

is exacerbated, ultimately resulting in LOI at all promoters and

widespread upregulation of IGF2 (150).

In addition to LOI, mutations in tripartite motif

containing 28 (TRIM28), a transcriptional co-repressor and

epigenetic regulator, have been implicated in IGF2 dysregulation.

Inactivating mutations in TRIM28 are frequently associated with

biallelic IGF2 expression, especially in tumors lacking other

common genetic alterations, suggesting that TRIM28 may drive

tumorigenesis via an independent IGF2-related mechanism (151).

Ethnic differences have been observed in the

prevalence of IGF2 imprinting abnormalities. For example, a study

has shown that LOI of IGF2 is more frequent in Wilms' tumor cases

among white children of Europe, North and South America and Oceania

compared with Japanese children, potentially reflecting

population-specific genetic or epigenetic susceptibility (152).

Collectively, the loss of IGF2 imprinting and TRIM28

mutations represent important events in the pathogenesis of Wilms'

tumor. These insights provide a compelling theoretical framework

for the development of IGF2-targeted therapies in pediatric renal

malignancies.

Therapeutic potential and treatments

targeting IGF2

As an important regulator of cell proliferation,

metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis, IGF2 has emerged as a

promising therapeutic target, with encouraging progress reported in

both preclinical and clinical studies (153–155).

In a preclinical model, the natural compound

curcumin has demonstrated potent antitumor effects in bladder

cancer by transcriptionally suppressing IGF2, blocking IGF1R/IR

substrate 1 phosphorylation and inhibiting the downstream AKT/mTOR

signaling cascade. These inhibitory effects are reversed by

exogenous IGF2 administration or IGF1R overexpression, highlighting

the notable role of IGF2 signaling in tumor progression and

validating its therapeutic relevance (156).

Clinically, monoclonal antibodies targeting IGF1R,

such as dalotuzumab, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as

linsitinib, have shown therapeutic efficacy in select sarcoma

subtypes (153). However, these

agents have shown limited benefit in breast cancer and non-small

cell lung cancer, reflecting the context-dependent nature of IGF

signaling and the heterogeneity of downstream pathway activation

(157). To overcome compensatory

mechanisms, dual-ligand neutralizing antibodies, neutralizing

antibodies with different targets have been developed. These

include dusigitumab (154), which

targets the IGF-1 receptor to block signaling from both IGF-1 and

IGF-2, and xentuzumab (155), a

dual-IGF-1/IGF-2 ligand-neutralizing antibody that directly binds

the ligands themselves. While conceptually promising, their

clinical utility has been constrained by the absence of robust

predictive biomarkers, which remains a notable barrier to broader

application (158).

In pediatric oncology, Wilms' tumor represents a

paradigm for IGF2-driven tumorigenesis (159). Using genetically engineered mouse

models harboring Wilms' tumor protein deletion and IGF2

overexpression, researchers have successfully recapitulated key

features of human WT, including impaired mesenchymal

differentiation and persistent ERK1/2 activation. These models

provide a robust platform for exploring therapeutic interventions

targeting the IGF axis (160).

With respect to angiogenesis, truncated IGF2

variants such as Des(1–6)IGF2 have been shown to promote

endothelial cell migration, tube formation and intra-ovarian

neovascularization by upregulating IL-6, urokinase plasminogen

activator surface receptor and CCL2. Notably, Des(1–6)IGF2 evades

inhibition by IGFBP-6, unlike Leu27IGF2, which preferentially binds

IGF2R and exhibits minimal angiogenic activity. These findings

implicate IGF1R and IR-A as dominant mediators of the

pro-angiogenic effects of IGF2 in pathological neovascularization

(161).

Despite these promising advances from above

experimental and mechanistic studies, several key challenges

persist. Ligand redundancy, tissue-specific pathway activation and

the lack of reliable biomarkers continue to impede precision

targeting of the IGF2 axis (76,162). Future research should focus on

developing IGF2-specific inhibitors, optimizing rational

combination therapies and identifying context-specific biomarkers,

particularly in diseases such as Wilms' tumor and

epigenetically-deregulated renal disorders, where IGF2 signaling is

pathologically upregulated.

Concluding remarks and future

perspectives

In previous years, with in-depth studies on the

biological role of IGF2 and its regulatory mechanisms, the multiple

roles of IGF2 in renal development and disease have been revealed.

Under normal physiological conditions, IGF2 serves an important

role in renal tubular and glomerular formation through precise gene

imprinting regulation (24,70).

However, under pathological conditions, aberrant expression of IGF2

accelerates the progression of renal fibrosis, DN and renal tumors

by activating specific signaling pathways (2,51,136).

Although IGF2 has been validated as a potential

biomarker and therapeutic target in renal diseases, a number of

mechanistic questions remain unresolved. Future investigations

should examine: i) The molecular interplay between IGF2 and

regulatory factors such as IGFBPs, TGF-β and VEGF; ii) the spatial

and temporal dynamics of receptor activation; and iii) the

differential roles of IGF2 in various pathological states.

Additionally, the design of IGF2-specific therapies is expected to

provide novel strategies for the treatment of kidney disease and

associated metabolic disorders.

In conclusion, IGF2 serves an increasingly

recognized role in renal biology and pathogenesis. A deeper

understanding of its regulatory mechanisms will facilitate the

development of precise diagnostic tools and targeted interventions

for renal diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82470773), Guangdong Provincial

Science and Technology Planning Project (grant no. 2023B110009),

Funding for Innovation Capacity Building Project of Guangdong

Provincial Research Institutes (grant no. KD032024001), and the

Guangdong Provincial Major Science and Technology Special Project

(grant no. KS012023323).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YS was responsible for conceptualization,

investigation, methodology, visualization, writing the original

draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. WHa acquired

funding, and contributed to the methodology, supervision, and

reviewing and editing of the manuscript. WL contributed to the

methodology and supervision, and reviewed and edited the

manuscript. WHu was responsible for conceptualization, the

acquisition of funding and resources, and contributed to

supervision, validation, writing the original draft, and reviewing

and editing the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Efstratiadis A: Genetics of mouse growth.

Int J Dev Biol. 42:955–976. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Eggenschwiler J, Ludwig T, Fisher P,

Leighton PA, Tilghman SM and Efstratiadis A: Mouse mutant embryos

overexpressing IGF-II exhibit phenotypic features of the

beckwith-wiedemann and simpson-golabi-behmel syndromes. Genes Dev.

11:3128–3142. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

St-Pierre J, Hivert MF, Perron P, Poirier

P, Guay SP, Brisson D and Bouchard L: IGF2 DNA methylation is a

modulator of newborn's fetal growth and development. Epigenetics.

7:1125–1132. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hoyo C, Fortner K, Murtha AP, Schildkraut

JM, Soubry A, Demark-Wahnefried W, Jirtle RL, Kurtzberg J, Forman

MR, Overcash F, et al: Association of cord blood methylation

fractions at imprinted insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), plasma

IGF2, and birth weight. Cancer Causes Control. 23:635–645.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chin E and Bondy C: Insulin-like growth

factor system gene expression in the human kidney. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 75:962–968. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Sandovici I,

Constancia M and Fowden AL: Placental phenotype and the

insulin-like growth factors: Resource allocation to fetal growth. J

Physiol. 595:5057–5093. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kuang X: Study of the relationship between

WT1 and IGF2 DNA methylation and kidney development and function in

intrauterine growth retardation rat. PhD dissertation (Shanghai).

Fudan University. 2012.(In Chinese).

|

|

8

|

Du L, Lin L, Li Q, Liu K, Huang Y, Wang X,

Cao K, Chen X, Cao W, Li F, et al: IGF-2 preprograms maturing

macrophages to acquire oxidative phosphorylation-dependent

anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab. 29:1363–1375.e8. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Livingstone C and Borai A: Insulin-like

growth factor-II: Its role in metabolic and endocrine disease. Clin

Endocrinol (Oxf). 80:773–781. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Matsumoto T, Kinoshita E, Maeda H, Niikawa

N, Kurosaki N, Harada N, Yun K, Sawai T, Aoki S, Kondoh T, et al:

Molecular analysis of a patient with beckwith-wiedemann syndrome,

rhabdomyosarcoma and renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Hum Genet.

39:225–234. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

LeRoith D, Werner H, Beitner-Johnson D and

Roberts CT Jr: Molecular and cellular aspects of the insulin-like

growth factor I receptor. Endocr Rev. 16:143–163. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Baserga R, Hongo A, Rubini M, Prisco M and

Valentinis B: The IGF-I receptor in cell growth, transformation and

apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1332:F105–F126. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Burvin R, LeRoith D, Harel H, Zloczower M,

Marbach M and Karnieli E: The effect of acute insulin-like growth

factor-II administration on glucose metabolism in the rat. Growth

Horm IGF Res. 8:205–210. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Salmon WD Jr and Daughaday WH: A

hormonally controlled serum factor which stimulates sulfate

incorporation by cartilage in vitro. J Lab Clin Med. 49:825–836.

1957.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Engström W, Shokrai A, Otte K, Granérus M,

Gessbo A, Bierke P, Madej A, Sjölund M and Ward A: Transcriptional

regulation and biological significance of the insulin like growth

factor II gene. Cell Prolif. 31:173–189. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Vu TH and Hoffman AR: Promoter-specific

imprinting of the human insulin-like growth factor-II gene. Nature.

371:714–717. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R, Vella V,

Lawrence MC, Sciacca L, Frasca F, Morrione A and Vigneri R: Insulin

receptor isoforms in physiology and disease: An updated view.

Endocr Rev. 38:379–431. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Constância M, Hemberger M, Hughes J, Dean

W, Ferguson-Smith A, Fundele R, Stewart F, Kelsey G, Fowden A,

Sibley C and Reik W: Placental-specific IGF-II is a major modulator

of placental and fetal growth. Nature. 417:945–948. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chao W and D'Amore PA: IGF2: Epigenetic

regulation and role in development and disease. Cytokine Growth

Factor Rev. 19:111–120. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Issa JP, Vertino PM, Boehm CD, Newsham IF

and Baylin SB: Switch from monoallelic to biallelic human IGF2

promoter methylation during aging and carcinogenesis. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 93:11757–11762. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhan S, Shapiro D, Zhan S, Zhang L,

Hirschfeld S, Elassal J and Helman LJ: Concordant loss of

imprinting of the human insulin-like growth factor II gene

promoters in cancer. J Biol Chem. 270:27983–27986. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

van Dijk MA, van Schaik FM, Bootsma HJ,

Holthuizen P and Sussenbach JS: Initial characterization of the

four promoters of the human insulin-like growth factor II gene. Mol

Cell Endocrinol. 81:81–94. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang Z, Huang S, Tian N, Xu Q, Zhan X,

Peng F, Wang X, Su N, Feng X, Tang X, et al: Association of the

remnant cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio

with mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Lipids Health Dis.

24:1072025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Morali OG, Jouneau A, McLaughlin KJ,

Thiery JP and Larue L: IGF-II promotes mesoderm formation. Dev

Biol. 227:133–145. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pardo M, Cheng Y, Sitbon YH, Lowell JA,

Grieco SF, Worthen RJ, Desse S and Barreda-Diaz A: Insulin growth

factor 2 (IGF2) as an emergent target in psychiatric and

neurological disorders. Review. Neurosci Res. 149:1–13. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Baserga R: The IGF-I receptor in cancer

research. Exp Cell Res. 253:1–6. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wojtalla A, Salm F, Christiansen DG,

Cremona T, Cwiek P, Shalaby T, Gross N, Grotzer MA and Arcaro A:

Novel agents targeting the IGF-1R/PI3K pathway impair cell

proliferation and survival in subsets of medulloblastoma and

neuroblastoma. PLoS One. 7:e471092012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Vigneri PG, Tirrò E, Pennisi MS, Massimino

M, Stella S, Romano C and Manzella L: The insulin/IGF system in

colorectal cancer development and resistance to therapy. Front

Oncol. 5:2302015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Vella V, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Mineo R,

Vigneri R, Pezzino V and Belfiore A: A novel autocrine loop

involving IGF-II and the insulin receptor isoform-A stimulates

growth of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 87:245–254.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Belfiore A, Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L

and Vigneri R: Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin

receptor/insulin-like growth factor receptor hybrids in physiology

and disease. Endocr Rev. 30:586–623. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Andersen M, Nørgaard-Pedersen D, Brandt J,

Pettersson I and Slaaby R: IGF1 and IGF2 specificities to the two

insulin receptor isoforms are determined by insulin receptor amino

acid 718. PLoS One. 12:e01788852017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Louvi A, Accili D and Efstratiadis A:

Growth-promoting interaction of IGF-II with the insulin receptor

during mouse embryonic development. Dev Biol. 189:33–48. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fukuda I, Hizuka N, Ishikawa Y, Yasumoto

K, Murakami Y, Sata A, Morita J, Kurimoto M, Okubo Y and Takano K:

Clinical features of insulin-like growth factor-II producing

non-islet-cell tumor hypoglycemia. Growth Horm IGF Res. 16:211–216.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Khowaja A, Johnson-Rabbett B, Bantle J and

Moheet A: Hypoglycemia mediated by paraneoplastic production of

insulin like growth factor-2 from a malignant renal solitary

fibrous tumor-clinical case and literature review. BMC Endocr

Disord. 14:492014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rikhof B, Van Den Berg G and Van Der Graaf

WTA: Non-islet cell tumour hypoglycaemia in a patient with a

gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Acta Oncol. 44:764–766. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zapf J: Role of insulin-like growth factor

II and IGF binding proteins in extrapancreatic tumor hypoglycemia.

Horm Res. 42:20–26. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zapf J, Futo E, Peter M and Froesch ER:

Can ‘big’ insulin-like growth factor II in serum of tumor patients

account for the development of extrapancreatic tumor hypoglycemia?

J Clin Invest. 90:2574–2584. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dynkevich Y, Rother KI, Whitford I,

Qureshi S, Galiveeti S, Szulc AL, Danoff A, Breen TL, Kaviani N,

Shanik MH, et al: Tumors, IGF-2, and hypoglycemia: insights from

the clinic, the laboratory, and the historical archive. Endocr Rev.

34:798–826. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu XH, Wang LH, Song JF, Wang WP and Shan

BE: Effect of IGF-II stimulation on the expression of matrix

metalloproteinase-9 in human ovarian cancer cell line SKOV3. Prog

Obstet Gynecol. 12:413–415. 2003.(In Chinese).

|

|

40

|

Han Y, Cui J, Tao J, Guo L, Guo P, Sun M,

Kang J, Zhang X, Yan C and Li S: CREG inhibits migration of human

vascular smooth muscle cells by mediating IGF-II endocytosis. Exp

Cell Res. 315:3301–3311. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhu M, Zhuang J, Li Z, Liu Q, Zhao R, Gao

Z, Midgley AC, Qi T, Tian J, Zhang Z, et al:

Machine-learning-assisted single-vessel analysis of nanoparticle

permeability in tumour vasculatures. Nat Nanotechnol. 18:657–666.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhou L, Liu Y, Xu T, Dong L, Yang X and

Wang C: Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney with IGF2

secretion and without hypoglycemia. World J Surg Oncol. 22:1792024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sciacca L, Prisco M, Wu A, Belfiore A,

Vigneri R and Baserga R: Signaling differences from the A and B

isoforms of the insulin receptor (IR) in 32D cells in the presence

or absence of IR substrate-1. Endocrinology. 144:2650–2658. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Escribano O, Gómez-Hernández A,

Díaz-Castroverde S, Nevado C, García G, Otero YF, Perdomo L, Beneit

N and Benito M: Insulin receptor isoform A confers a higher

proliferative capability to pancreatic beta cells enabling glucose

availability and IGF-I signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 409:82–91.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ghosh P, Dahms NM and Kornfeld S: Mannose

6-phosphate receptors: New twists in the tale. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 4:202–212. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

El-Shewy HM and Luttrell LM: Insulin-like

growth factor-2/mannose-6 phosphate receptors. Vitam Horm.

80:667–697. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Y, MacDonald RG, Thinakaran G and Kar

S: Insulin-like growth factor-II/cation-independent mannose

6-phosphate receptor in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol.

54:2636–2658. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Nadimpalli SK and Amancha PK: Evolution of

mannose 6-phosphate receptors (MPR300 and 46): Lysosomal enzyme

sorting proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 11:68–90. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Massagué J: The transforming growth

factor-beta family. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 6:597–641. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Leksa V, Godar S, Schiller HB, Fuertbauer

E, Muhammad A, Slezakova K, Horejsi V, Steinlein P, Weidle UH,

Binder BR and Stockinger H: TGF-beta-induced apoptosis in

endothelial cells mediated by M6P/IGFII-R and mini-plasminogen. J

Cell Sci. 118:4577–4586. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Livingstone C: IGF2 and cancer. Endocr

Relat Cancer. 20:R321–R339. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Sélénou C, Brioude F, Giabicani E, Sobrier

ML and Netchine I: IGF2: Development, genetic and epigenetic

abnormalities. Cells. 11:18862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhu Y, Chen L and Song B, Cui Z, Chen G,

Yu Z and Song B: Insulin-like growth factor-2 (IGF-2) in fibrosis.

Biomolecules. 12:15572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wolf E, Hoeflich A and Lahm H: What is the

function of IGF-II in postnatal life? Answers from transgenic mouse

models. Growth Horm IGF Res. 8:185–193. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Barroca V, Lewandowski D, Jaracz-Ros A and

Hardouin SN: Paternal insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) regulates

stem cell activity during adulthood. eBioMedicine. 15:150–162.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang MJ, Chen F, Liu QG, Liu CC, Yao H, Yu

B, Zhang HB, Yan HX, Ye Y, Chen T, et al: Insulin-like growth

factor 2 is a key mitogen driving liver repopulation in mice. Cell

Death Dis. 9:262018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wolf E, Kramer R, Blum WF, Föll J and Brem

G: Consequences of postnatally elevated insulin-like growth

factor-II in transgenic mice: Endocrine changes and effects on body

and organ growth. Endocrinology. 135:1877–1886. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Blackburn A, Schmitt A, Schmidt P, Wanke

R, Hermanns W, Brem G and Wolf E: Actions and interactions of

growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-II: Body and organ

growth of transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 6:213–222. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Avner ED and Sweeney WE Jr: Polypeptide

growth factors in metanephric growth and segmental nephron

differentiation. Pediatr Nephrol. 4:372–377. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Jelinic P and Shaw P: Loss of imprinting

and cancer. J Pathol. 211:261–268. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Sun FL, Dean WL, Kelsey G, Allen ND and

Reik W: Transactivation of Igf2 in a mouse model of

beckwith-wiedemann syndrome. Nature. 389:809–815. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lui JC, Finkielstain GP, Barnes KM and

Baron J: An imprinted gene network that controls mammalian somatic

growth is down-regulated during postnatal growth deceleration in

multiple organs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol.

295:R189–R196. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Hirschberg R and Adler S: Insulin-like

growth factor system and the kidney: Physiology, pathophysiology,

and therapeutic implications. Am J Kidney Dis. 31:901–919. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Svensson J, Tivesten A, Sjögren K,

Isaksson O, Bergström G, Mohan S, Mölne J, Isgaard J and Ohlsson C:

Liver-derived IGF-I regulates kidney size, sodium reabsorption, and

renal IGF-II expression. J Endocrinol. 193:359–366. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Feld S and Hirschberg R: Growth hormone,

the insulin-like growth factor system, and the kidney. Endocr Rev.

17:423–480. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Moerth C, Schneider MR, Renner-Mueller I,

Blutke A, Elmlinger MW, Erben RG, Camacho-Hübner C, Hoeflich A and

Wolf E: Postnatally elevated levels of insulin-like growth factor

(IGF)-II fail to rescue the dwarfism of IGF-I-deficient mice except

kidney weight. Endocrinology. 148:441–451. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

LeRoith D, Holly JMP and Forbes BE:

Insulin-like growth factors: Ligands, binding proteins, and

receptors. Mol Metab. 52:1012452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Rabkin R and Schaefer F: New concepts:

Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I and the kidney. Growth

Horm IGF Res. 14:270–276. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Kie JH, Kapturczak MH, Traylor A, Agarwal

A and Hill-Kapturczak N: Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency promotes

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and renal fibrosis. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 19:1681–1691. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Hale LJ, Welsh GI, Perks CM, Hurcombe JA,

Moore S, Hers I, Saleem MA, Mathieson PW, Murphy AJ, Jeansson M, et

al: Insulin-like growth factor-II is produced by, signals to and is

an important survival factor for the mature podocyte in man and

mouse. J Pathol. 230:95–106. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Grotendorst GR, Rahmanie H and Duncan MR:

Combinatorial signaling pathways determine fibroblast proliferation

and myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J. 18:469–479. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Elchebly M, Payette P, Michaliszyn E,

Cromlish W, Collins S, Loy AL, Normandin D, Cheng A, Himms-Hagen J,

Chan CC, et al: Increased insulin sensitivity and obesity

resistance in mice lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B

gene. Science. 283:1544–1548. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Daza-Arnedo R, Rico-Fontalvo J,

Aroca-Martínez G, Rodríguez-Yanez T, Martínez-Ávila MC,

Almanza-Hurtado A, Cardona-Blanco M, Henao-Velásquez C,

Fernández-Franco J, Unigarro-Palacios M, et al: Insulin and the

kidneys: A contemporary view on the molecular basis. Front Nephrol.

3:11333522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Singh S, Sharma R, Kumari M and Tiwari S:

Insulin receptors in the kidneys in health and disease. World J

Nephrol. 8:11–22. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Enguita-Germán M and Fortes P: Targeting

the insulin-like growth factor pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma.

World J Hepatol. 6:716–737. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang X, Lin L, Lan B, Wang Y, Du L, Chen

X, Li Q, Liu K, Hu M, Xue Y, et al: IGF2R-initiated proton

rechanneling dictates an anti-inflammatory property in macrophages.

Sci Adv. 6:eabb73892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Rainier S, Dobry CJ and Feinberg AP: Loss

of imprinting in hepatoblastoma. Cancer Res. 55:1836–1838.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Honda S, Arai Y, Haruta M, Sasaki F, Ohira

M, Yamaoka H, Horie H, Nakagawara A, Hiyama E, Todo S and Kaneko Y:

Loss of imprinting of IGF2 correlates with hypermethylation of the

H19 differentially methylated region in hepatoblastoma. Br J

Cancer. 99:1891–1899. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Bell AC and Felsenfeld G: Methylation of a

CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2

gene. Nature. 405:482–485. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Thorvaldsen JL, Duran KL and Bartolomei

MS: Deletion of the H19 differentially methylated domain results in

loss of imprinted expression of H19 and Igf2. Genes Dev.

12:3693–3702. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Tremblay KD, Saam JR, Ingram RS, Tilghman

SM and Bartolomei MS: A paternal-specific methylation imprint marks

the alleles of the mouse H19 gene. Nat Genet. 9:407–413. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Chang S and Bartolomei MS: Modeling human

epigenetic disorders in mice: Beckwith-wiedemann syndrome and

silver-russell syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 13:dmm0441232020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Han L, Lee DH and Szabó PE: CTCF is the

master organizer of domain-wide allele-specific chromatin at the

H19/Igf2 imprinted region. Mol Cell Biol. 28:1124–1135. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Matsuzaki H, Kuramochi D, Okamura E,

Hirakawa K, Ushiki A and Tanimoto K: Recapitulation of gametic DNA

methylation and its post-fertilization maintenance with reassembled

DNA elements at the mouse Igf2/H19 locus. Epigenetics Chromatin.

13:22020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Leighton PA, Saam JR, Ingram RS, Stewart

CL and Tilghman SM: An enhancer deletion affects both H19 and Igf2

expression. Genes Dev. 9:2079–2089. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Neirijnck Y, Papaioannou MD and Nef S: The

insulin/IGF system in mammalian sexual development and

reproduction. Int J Mol Sci. 20:44402019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Huang SCC, Smith AM, Everts B, Colonna M,

Pearce EL, Schilling JD and Pearce EJ: Metabolic reprogramming

mediated by the mTORC2-IRF4 signaling axis is essential for

macrophage alternative activation. Immunity. 45:817–830. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Bridgewater DJ, Ho J, Sauro V and Matsell

DG: Insulin-like growth factors inhibit podocyte apoptosis through

the PI3 kinase pathway. Kidney Int. 67:1308–1314. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Tziastoudi M, Theoharides TC, Nikolaou E,

Efthymiadi M, Eleftheriadis T and Stefanidis I: Key genetic

components of fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy: An updated

systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 23:153312022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Liao J, Song S, Gusscott S, Fu Z,

VanderKolk I, Busscher BM, Lau KH, Brind'Amour J and Szabó PE:

Establishment of paternal methylation imprint at the H19/Igf2

imprinting control region. Sci Adv. 9:eadi20502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Levey AS and James MT: Acute kidney

injury. Ann Intern Med. 167:ITC66–ITC80. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zhan Z, Chen J, Zhou H, Hong X, Li L, Qin

X, Fu H and Liu Y: Chronic alcohol consumption aggravates acute

kidney injury through integrin β1/JNK signaling. Redox Biol.

77:1033862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Yamamoto R, Li Q, Otsuki N, Shinzawa M,

Yamaguchi M, Wakasugi M, Nagasawa Y and Isaka Y: A dose-dependent

association between alcohol consumption and incidence of

proteinuria and low glomerular filtration rate: A systematic review

and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutrients. 15:15922023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Orth SR: Smoking and the kidney. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 13:1663–1672. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Chen Q and Ou L: Meta-analysis of the

association between the dietary inflammatory index and risk of

chronic kidney disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. 79:7–14. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Danziger J, Chen KP, Lee J, Feng M, Mark

RG, Celi LA and Mukamal KJ: Obesity, acute kidney injury, and

mortality in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 44:328–334. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Tan X, Tao Q, Yin S, Fu G, Wang C, Xiang

F, Hu H, Zhang S, Wang Z and Li D: A single administration of FGF2

after renal ischemia-reperfusion injury alleviates post-injury

interstitial fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 38:2537–2549. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Tsao T, Wang J, Fervenza FC, Vu TH, Jin

IH, Hoffman AR and Rabkin R: Renal growth hormone-insulin-like

growth factor-I system in acute renal failure. Kidney Int.

47:1658–1668. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Zhang L, Ma X and Wang JQ: Research

progress on the correlation between insulin-like growth factor II,

its binding protein 2 and diabetic nephropathy. Clin Med China.

32:954–957. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

100

|

Kashani K, Al-Khafaji A, Ardiles T,

Artigas A, Bagshaw SM, Bell M, Bihorac A, Birkhahn R, Cely CM,

Chawla LS, et al: Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest

biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 17:R252013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Livingston MJ, Shu S, Fan Y, Li Z, Jiao Q,

Yin XM, Venkatachalam MA and Dong Z: Tubular cells produce FGF2 via

autophagy after acute kidney injury leading to fibroblast

activation and renal fibrosis. Autophagy. 19:256–277. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Das S, Thakur S, Korenjak M, Sidorenko VS,

Chung FFL and Zavadil J: Aristolochic acid-associated cancers: A

public health risk in need of global action. Nat Rev Cancer.

22:576–591. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Vanherweghem JL, Depierreux M, Tielemans

C, Abramowicz D, Dratwa M, Jadoul M, Richard C, Vandervelde D,

Verbeelen D, Vanhaelen-Fastre R, et al: Rapidly progressive

interstitial renal fibrosis in young women: Association with

slimming regimen including Chinese herbs. Lancet. 341:387–391.

1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Lebeau C, Arlt VM, Schmeiser HH, Boom A,

Verroust PJ, Devuyst O and Beauwens R: Aristolochic acid impedes

endocytosis and induces DNA adducts in proximal tubule cells.

Kidney Int. 60:1332–1342. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Wen YJ, Qu L and Li XM: Ischemic injury

underlies the pathogenesis of aristolochic acid-induced acute

kidney injury. Transl Res. 152:38–46. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Komatsu M, Funakoshi T, Aki T and Unuma K:

Aristolochic acid-induced DNA adduct formation triggers acute DNA

damage response in rat kidney proximal tubular cells. Toxicol Lett.

406:1–8. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Chen J, Li H, Bai Y, Luo P, Cheng G, Ding

Z, Xu Z, Gu L, Wong L, Pang X, et al: Spatially resolved

multi-omics unravels region-specific responses, microenvironment

remodeling and metabolic reprogramming in aristolochic acid