Introduction

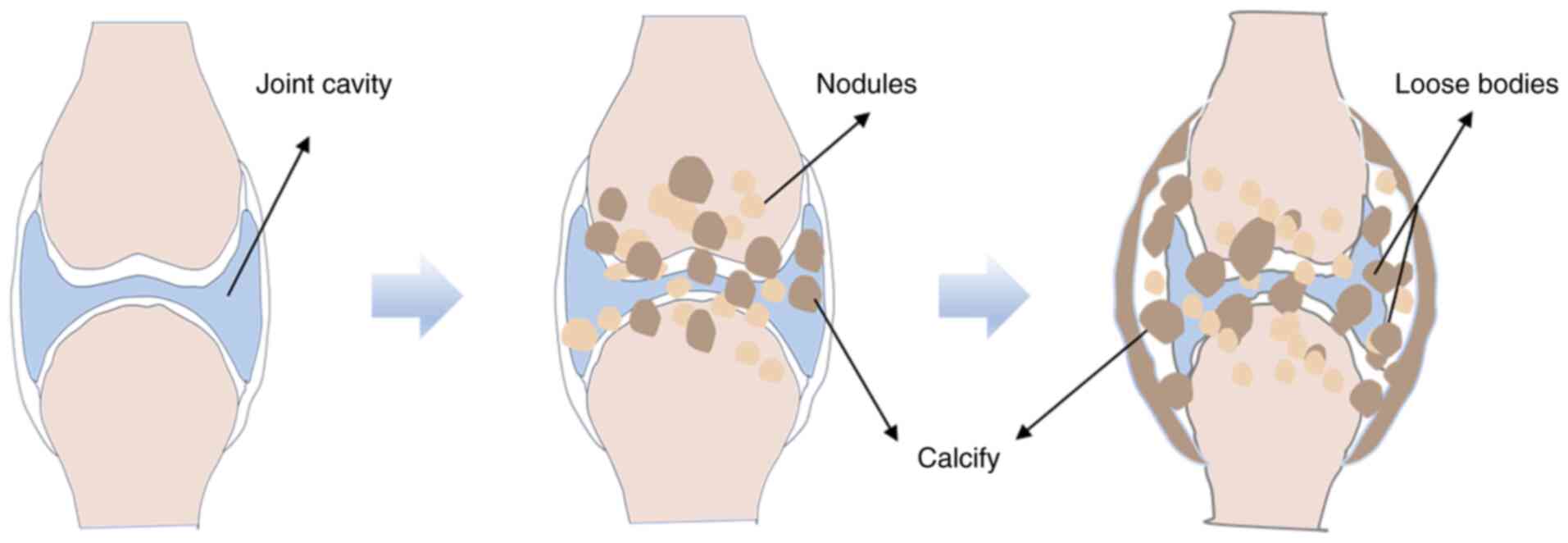

Synovial chondromatosis (SC), also known as synovial

osteochondromatosis, is a relatively rare benign synovial lesion.

The hallmark feature of SC is the formation of multiple cartilage

nodules within the synovium of joints, tendon sheaths and bursae.

Some of these nodules may detach into the joint cavity, forming

loose bodies (1,2) (Fig.

1). SC largely affects the knee joint, followed by the hip,

shoulder, elbow, ankle and wrist joints (3). It is less commonly observed in the

metacarpophalangeal, interphalangeal, acromioclavicular,

temporomandibular and intervertebral joints (4–6).

Extraglenoid SC is commonly observed in the hands, feet, wrists and

ankles, typically presenting as localized, painless masses

(7). Clinically, SC can range from

asymptomatic to symptomatic, with manifestations including joint

swelling, pain, limited range of motion, recurrent effusion,

crepitus and locking phenomena (3,8). In

certain cases, palpable masses may be detected and severe cases may

involve neurovascular compromise (3,8,9). SC

is generally classified into primary SC (PSC) or secondary SC (SSC)

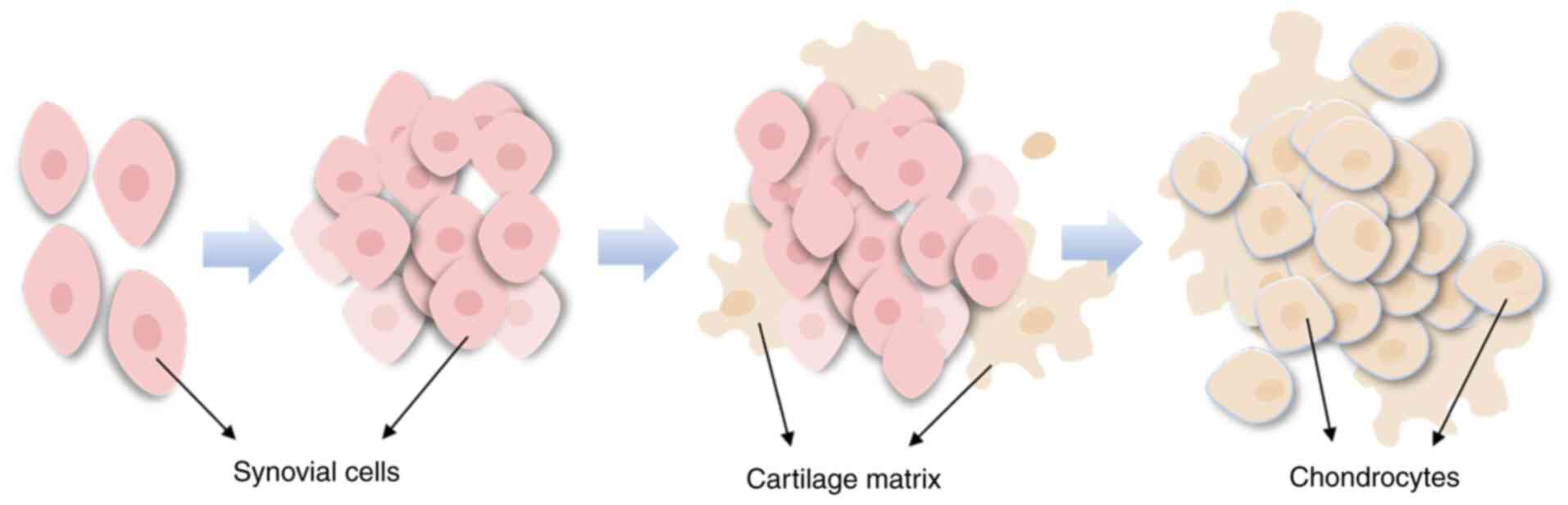

based on its etiology and histopathological features. PSC

originates from the normal synovium and is characterized by the

abnormal chondroid metaplasia of synovial cells (Fig. 2), with an increased number of loose

bodies that are widely distributed and a greater recurrence rate

(9,10). By contrast, SSC is often induced by

conditions such as osteoarthritis or joint trauma, with cartilage

fragments embedded in the synovium, triggering chondroid

metaplasia. SSC typically presents with fewer but larger loose

bodies and imaging studies often show characteristic changes

related to the underlying primary disease (10,11).

Although SC is a benign lesion, it has a high recurrence rate, and

certain cases may transform into low-grade synovial sarcoma (SS)

(9). Therefore, in-depth research

into the pathogenesis of SC is essential for optimizing clinical

diagnosis and treatment. The present review summarizes the latest

advancements in SC research, focusing on its epidemiological

trends, pathogenesis, clinical strategies and malignant potential.

The aim of the present review is to highlight avenues to improve

clinical recognition, optimize treatment plans and reduce the risk

of recurrence and malignant transformation.

Epidemiology of SC

Incidence rate

SC is a relatively rare condition with an incidence

of ~1 case per 100,000 individuals. It primarily affects adults

between the ages of 30 and 50 years, although both infants and the

elderly can also be affected (1,12,13).

Earlier studies suggested that the male-to-female ratio of SC was

1.8:1, indicating a higher prevalence in males (12,13).

However, other studies suggest that this ratio may range from 2:1

to 4:1 (14). Notably, in areas

such as the temporomandibular joint, hands and wrists, the

incidence in females may be higher compared with males (15). Furthermore, due to the

often-insidious symptoms of SC, the average time to diagnosis is ~5

years (15). However, with

advancements in imaging technology, the detection rate of SC has

markedly increased over the years (8). The higher incidence of SC in adults

may be associated with long-term joint stress and a history of

trauma, while the rarity of SC in children may be related to

protective mechanisms during skeletal development (14). Additionally, PSC and SSC exhibit

notable differences in epidemiology. PSC is generally more common

and has a higher recurrence rate, whereas SSC is primarily

associated with osteoarthritis or joint injuries, being relatively

rare and often confused with primary diseases (9–11,16).

Extraglenoid SC is rare, typically presenting as a painless mass

and there is no notable trend associated with sex or age in these

cases (14).

Recurrence rate and malignant

transformation rate

The recurrence rate of SC ranges from 0–31%, with

the recurrence rate being lower when loose body removal and

synovectomy are carried out via arthroscopy (~7.1%) (17,18).

However, if the synovectomy is incomplete, the recurrence rate may

rise to 20–30% (19). PSC has an

increased recurrence rate compared with SSC, suggesting that PSC

may exhibit more biological activity (9–11).

Multiple recurrences may increase the risk of transformation into

SS. Overall, the risk of malignant transformation in SC is low,

typically ~5% (20). However, a

study has reported a malignant transformation rate of ≤11.1% in hip

joint SC cases (21), although

this value may be lower in actual clinical practice due to limited

follow-up times. Malignant transformation in SC is typically

observed in cases with a disease duration of >5 years or in

recurrent cases. Symptoms such as pain, swelling and local

destruction may occur, and certain patients may exhibit cartilage

matrix calcification and nuclear atypia, which resemble the

features of low-grade SS (14).

Compared with SSC, PSC carries a higher risk of malignant

transformation, and gene fusions such as FN1-ACVR2A and chromosomal

abnormalities have been detected in certain cases (22). However, to the best of our

knowledge, there are currently no clear predictive markers for

malignant transformation, emphasizing the need for long-term

follow-up and biological assessments.

In summary, SC has a low incidence, delayed

diagnosis and a higher prevalence in males. The recurrence rate of

PSC is higher than that of SSC, with stronger biological activity,

which may increase the risk of malignancy. The overall malignancy

rate of SC is low, but cases with long-term recurrence may have

potential for malignant transformation. Currently, epidemiological

data on SC are limited and the mechanisms of malignancy remain

unclear, with no effective predictive indicators. Further research

is required on its pathogenesis, diagnostic methods and long-term

prognosis.

Novel advances in the pathogenesis of

SC

Although the exact pathogenesis of SC remains

incompletely understood, recent research has revealed several

potential mechanisms underlying the disease. According to the 2020

edition of the World Health Organization classification, SC has

been categorized as a neoplastic disease due to its local

invasiveness and clonal chromosomal changes (23). Milgram (24) categorized the pathological

progression of SC into three stages: Synovial hyperplasia (Stage

I), free body formation (Stage II) and stabilization (Stage III),

although this staging system does not accurately predict disease

progression. By contrast, Gerard et al (25) classified SC into four stages based

on changes in synovial activity: Early chondrification, free body

formation, cartilage nodule maturation and synovial atrophy. This

staging system is more effective for evaluating disease activity

and determining the timing of surgical intervention (25).

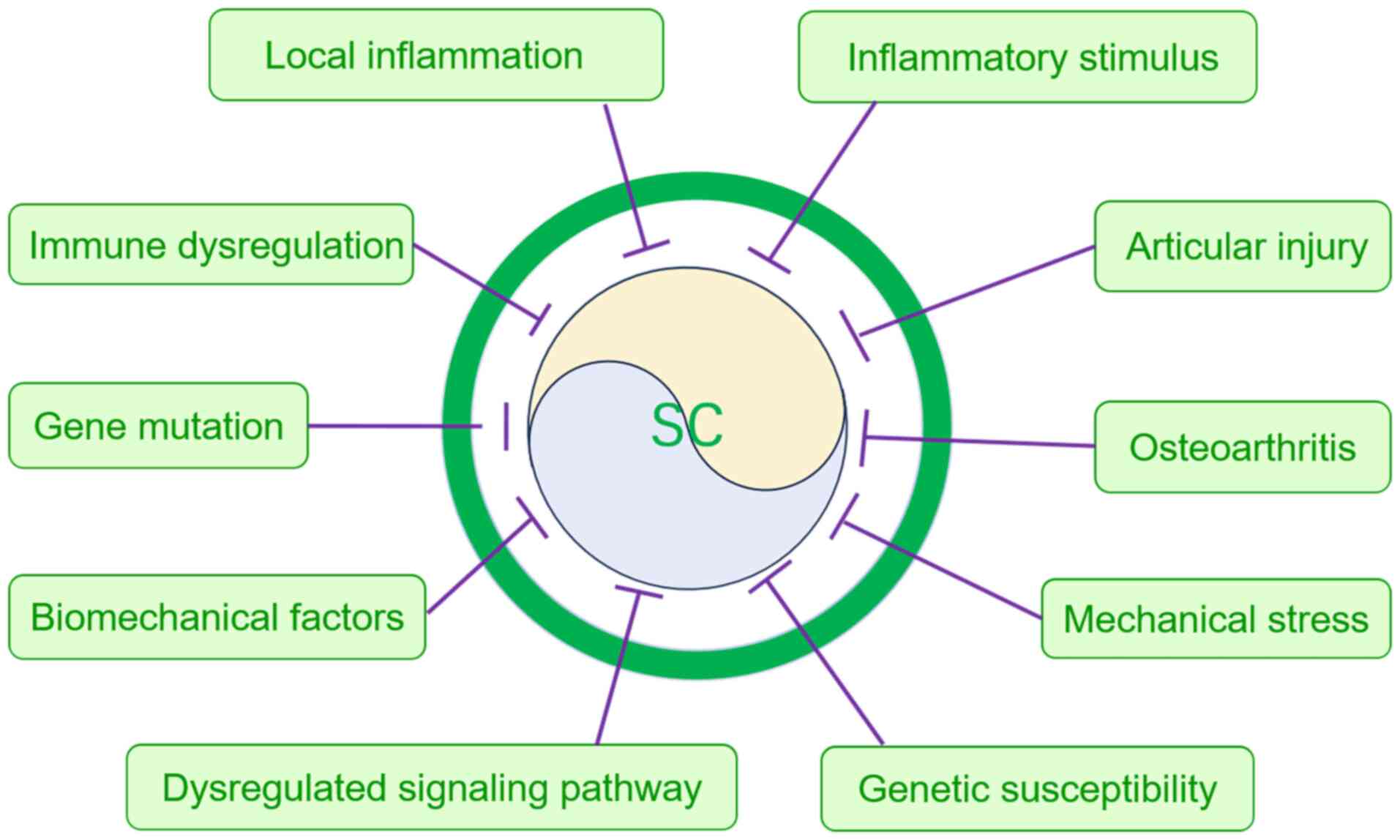

Regarding the pathogenesis of SC, current studies

primarily focus on the differential pathological origins of PSC and

SSC (7,11,26,27).

PSC is hypothesized to result from abnormal chondrification of

synovial cells, potentially associated with genetic mutations,

signaling pathway abnormalities, inflammatory stimuli and

mechanical stress (7,11,26,27).

By contrast, SSC is more commonly triggered by chronic stimuli such

as osteoarthritis or joint injury, primarily resulting from

prolonged exposure of the synovium to mechanical stress or the

embedding of cartilage fragments into the synovium (7,11).

In terms of risk factors, PSC is frequently associated with genetic

susceptibility, immune abnormalities and signaling pathway

activation, while SSC is more likely to be influenced by local

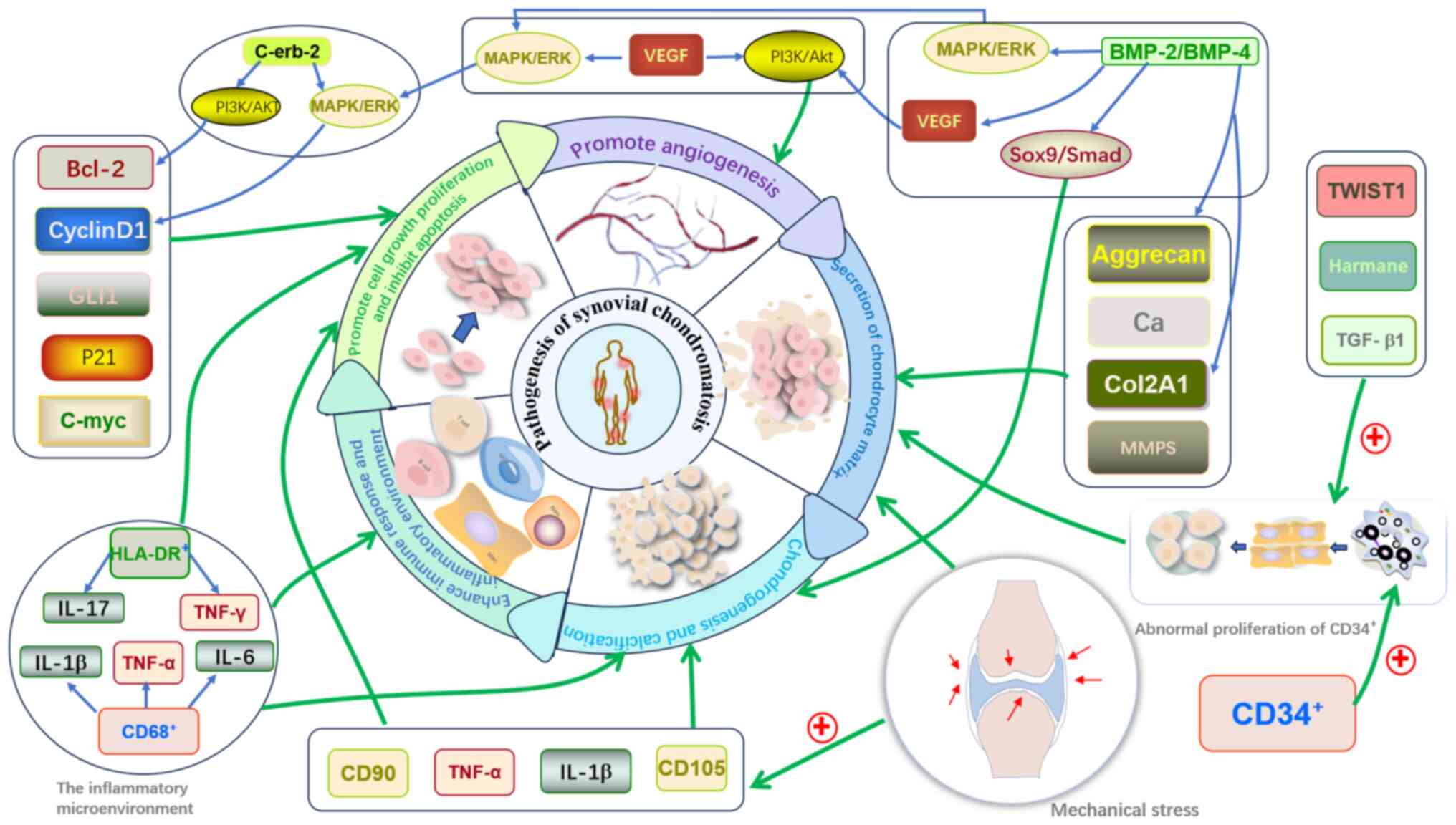

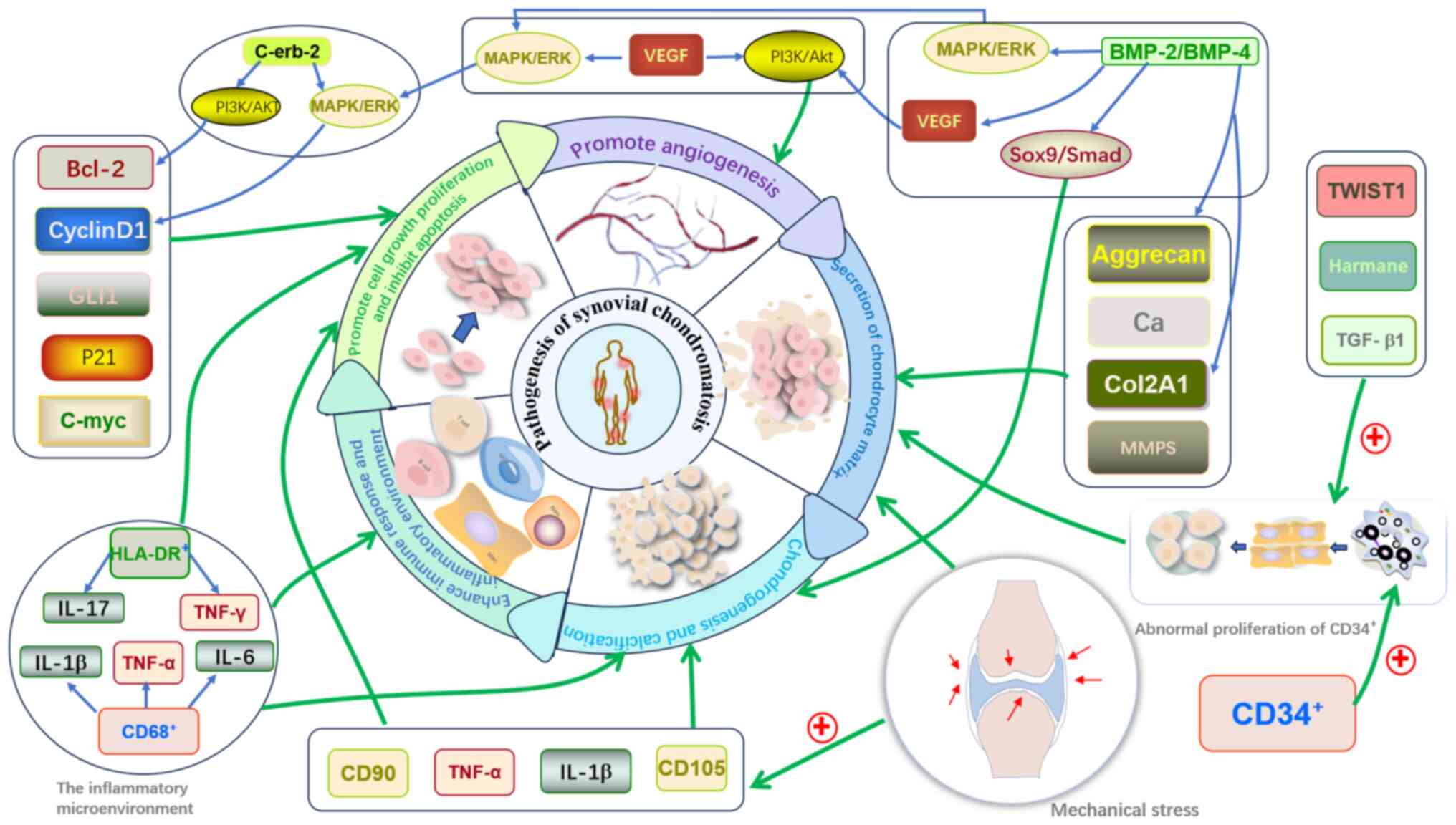

inflammation and biomechanical factors (Fig. 3) (26,27).

Recently, research on the pathogenesis of SC has shifted towards

the regulation of signaling pathways, changes in the synovial

microenvironment and genetic characteristics. Several potential

pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed in previous studies

(28–33). This section discusses the

pathogenesis of SC in terms of signaling pathway abnormalities,

inflammatory microenvironment and mechanical stress (Table I).

| Table I.Key signaling pathways and their

mechanisms in synovial chondromatosis with experimental

evidence. |

Table I.

Key signaling pathways and their

mechanisms in synovial chondromatosis with experimental

evidence.

| Signaling

pathway | Key regulators and

effectors | Biological

function | Experimental

evidence | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Hedgehog | GLI1, PTC1, Gli3,

Cyclin D1, Col2A1 | Synovial cell

proliferation, accelerated chondrogenesis | PTC1 and GLI1 gene

expression in PSC tissues increased 8-fold and 6-fold,

respectively, compared with normal synovium tissue, in

Gli3-deficient mouse models, Hedgehog pathway inhibition reduced SC

lesion incidence by 50%. | (28) |

| TGF-β | TGF-β1, Smad2/3,

Aggrecan, Sox9 | Cartilage matrix

synthesis, enhanced cell migration | Animal models

confirmed TGF-β1 overexpression directly induces synovial

fibroblast differentiation into chondrocytes (223-fold increase in

type II collagen), TGF-β1 drives chondrometaplasia via MMP-13

(300-fold) and osteopontin (130-fold) upregulation. | (30) |

| FGF9/FGFR3 | FGF9, MAPK/ERK,

c-Myc, Bcl-2 | Chondrometaplasia,

apoptosis | FGF9 levels

elevated 3-5-fold in PSC tissues, FGFR3 inhibitors reduced

cartilage nodules by 62%. | (29,32) |

| IL-6 | IL-6, STAT3,

VEGF-A, MMPs | Angiogenesis,

cartilage degradation | IL-6 concentration

in SC synovial fluid was 150-fold higher than the controls, VEGF-A

levels in the lesion group were 60-fold higher than in

controls. | (31) |

| Mechanical

stress | TNF-α, CD105,

Ca2+ | Adaptive synovial

hyperplasia, osteophyte formation | Stress stimulation

upregulates TNF-α/CD105. | (31,33) |

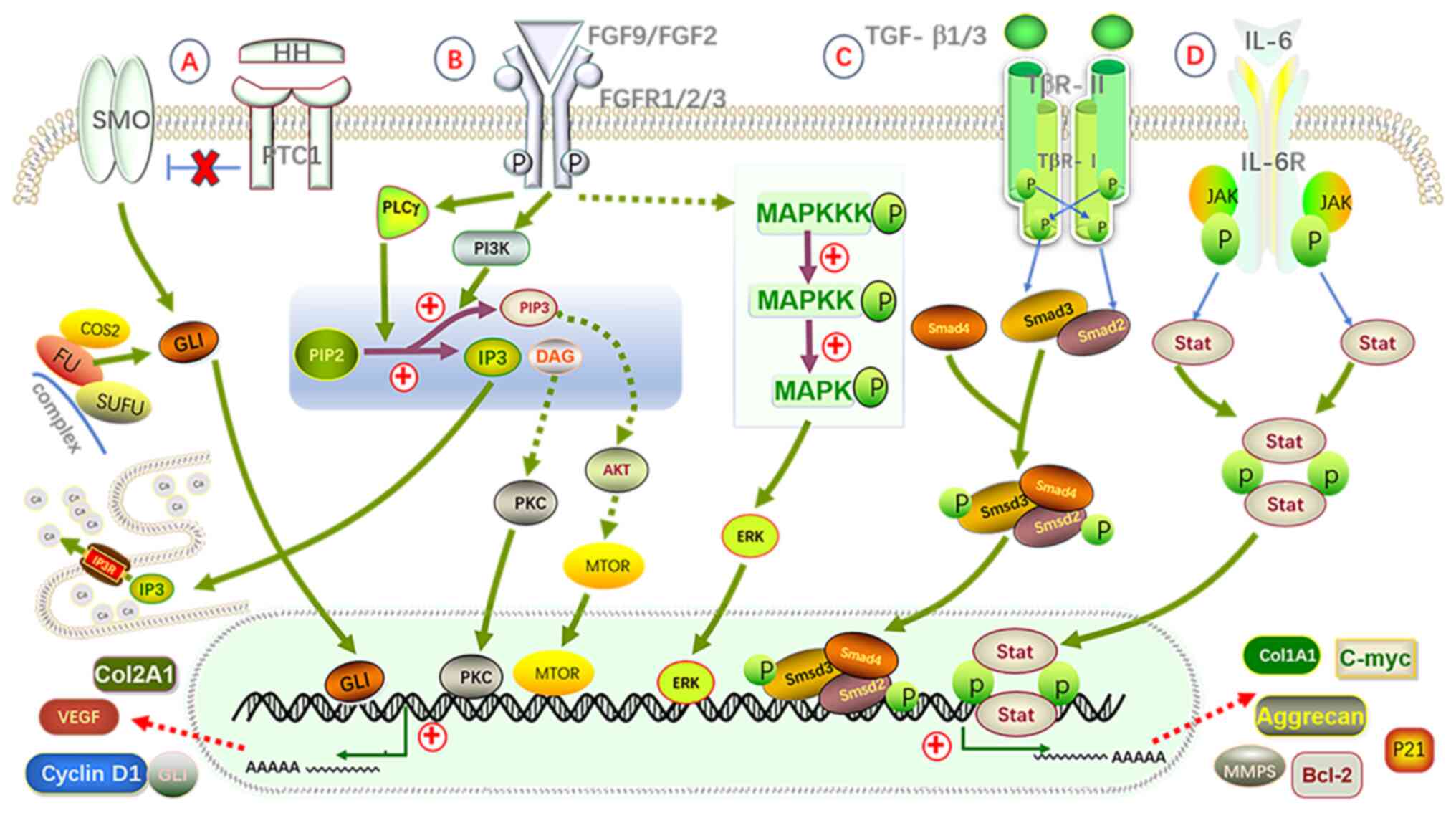

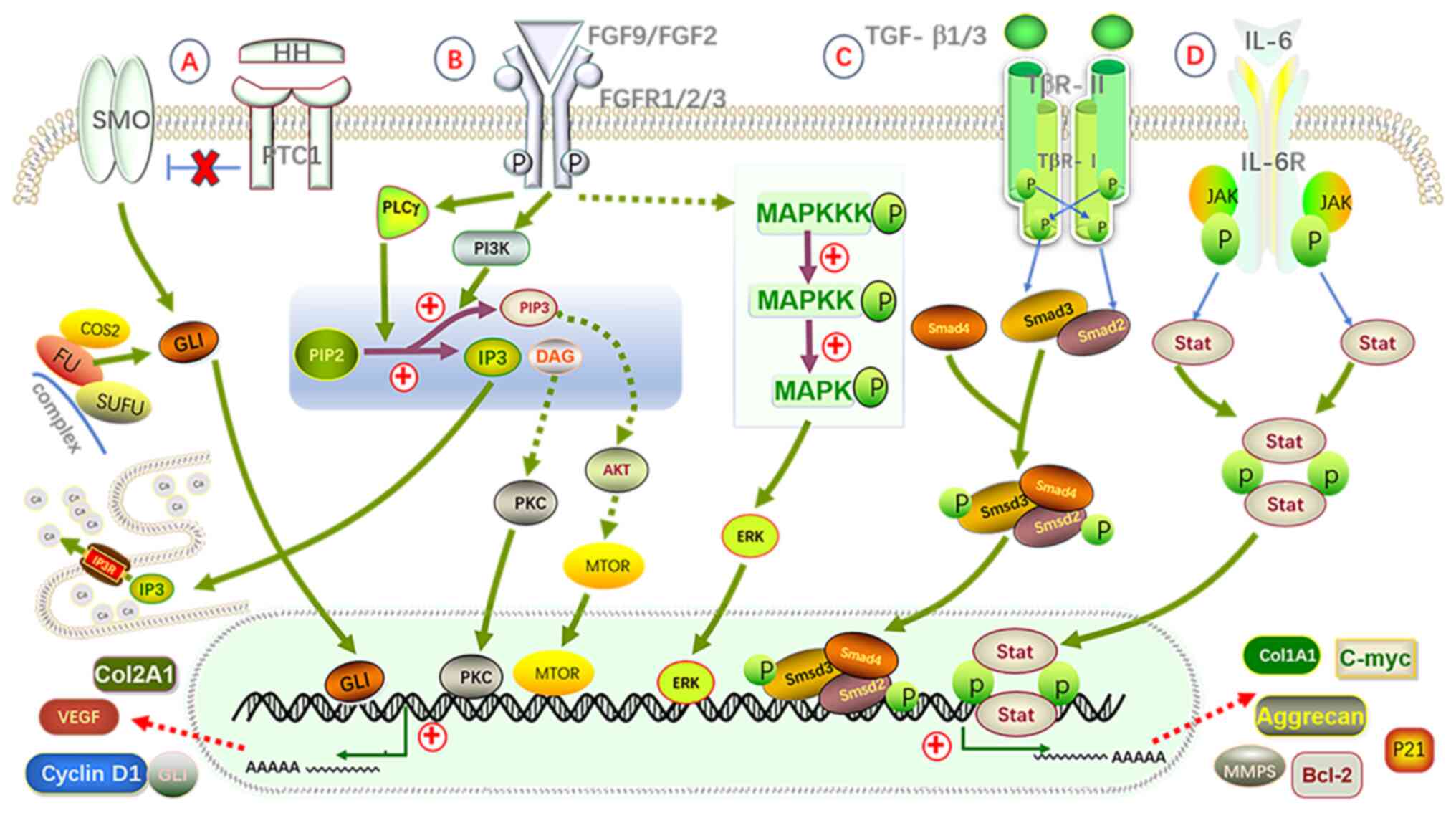

The role of signaling pathways in the

pathogenesis of SC

Occurrence of SC involves multiple signaling

pathways, with the Hedgehog, FGF9/FGFR3 and TGF-β pathways being

considered the most key (28–30)

(Fig. 4). Overactivation of the

Hedgehog signaling pathway induces abnormal proliferation of

synovial cells and promotes their differentiation into

chondrocytes. A study has shown that elevated expression of PTC1

and GLI1 genes in PSC patient tissues suggests that the Hedgehog

signaling pathway may carry out a pivotal role in SC pathogenesis

(28). Furthermore, the FGF9/FGFR3

pathway promotes chondrification of synovial cells through the

abnormal activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling axis, accelerating

disease progression. The notably elevated FGF9 levels in tissues of

patients with PSC further corroborate this mechanism (29). The abnormal activation of the TGF-β

signaling pathway also carries out a significant role in the

pathogenesis of SC, as TGF-β1 promotes synovial cell proliferation

and cartilage matrix formation via both Smad-dependent and

independent pathways, exacerbating disease progression (30). In addition to these pathways,

TGF-β3, FGF2 and IL-6 may also contribute to SC development

(31,32,34).

Although these signaling pathway abnormalities have been confirmed,

their specific roles in different stages and subtypes of SC require

further investigation (28–32,34).

| Figure 4.Schematic diagram of the roles of

four major signaling pathways (Hedgehog, FGF, TGF-β and IL-6) in

the pathogenesis of SC. (A) Hedgehog pathway: The HH ligand binds

to the PTC1 receptor, relieving the inhibition of the SMO receptor,

which activates Gli proteins and causes them to dissociate from the

complex formed by COS2, FU and SUFU. This activation subsequently

upregulates the expression of genes such as Cyclin D1, Col2A1 and

Aggrecan. (B) FGF pathway: After the FGF ligand binds to the FGFR

receptor, it activates the IP3-DAG-PKC, MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt

signaling pathways, leading to the expression of genes including

calcium ions, Cyclin D1, Bcl-2 and c-Myc. (C) TGF-β pathway: The

TGF-β ligand binds to the TGF-βRII receptor, activating the

tyrosine phosphorylation of the TGF-βRI receptor, which in turn

activates the Smad2/3 signaling pathway. The activated Smad complex

then enters the nucleus, regulating genes associated with

chondrogenesis and cell proliferation, such as Col2A1, Aggrecan,

Sox9 and Cyclin D1. (D) IL-6 pathway: IL-6 binds to its receptor

IL-6R, activating the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which promotes

the expression of Cyclin D1, c-Myc, Bcl-2 and VEGF. Ultimately, the

upregulation of these genes promotes cell proliferation, inhibits

apoptosis, accelerates synovial cell differentiation and

chondrogenesis, and thus facilitates the formation of SC. Bcl-2,

B-cell lymphoma 2; c-Myc, cellular Myc; Col2A1, collagen type IIα1;

DAG, diacylglycerol; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; FGF,

fibroblast growth factor; Gli, Glioma-associated oncogene homolog;

HH, Hedgehog; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-6R, IL-6 receptor; IP3,

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

receptor; JAK/STAT, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of

transcription; MAPK/ERK, mitogen-activated protein

kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MMPs, matrix

metalloproteinases; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin;

PI3K/Akt, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B; PIP2,

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PKC, protein kinase C; PTC1,

Patched 1; SC, synovial chondromatosis; Smad2/3/4, Smad family

proteins 2/3/4; Sox9, SRY-box 9; SMO, Smoothened; SUFU, suppressor

of FU; TGF-βRI, transforming growth factor-β receptor I; VEGF,

vascular endothelial growth factor; COS2, Costal 2; FU, Fused. |

Role of the inflammatory

microenvironment in SC pathogenesis

The development of SC is associated with its

inflammatory microenvironment (Fig.

5). A study has shown that IL-6 and VEGF-A levels are

considerably elevated in the synovial fluid of patients with SC,

where IL-6 enhances inflammation via the JAK/STAT signaling pathway

and VEGF-A promotes angiogenesis, potentially leading to chronic

inflammation and accelerating disease progression (31). In patients with PSC, an increase in

CD68+ synovial macrophages and human leukocyte antigen-DR-positive

cells indicates that immune dysregulation carries out a key role in

the pathogenesis of PSC (35). At

the molecular level, the co-expression of COL3A1 and CD90

synergistically promotes the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and

COL2A1, enhancing chondrocyte migration and proliferation. These

molecules contribute to the pathogenesis of SC through immune and

metabolic pathways and may serve as potential diagnostic markers to

distinguish PSC from SSC (36).

Additionally, the overlapping expression of biomarkers such as

PCNA, CD90, CD105, IGF-1 and TGF-β1 in PSC cartilage nodules

highlights the complex interactions between cell proliferation,

mesenchymal stem cells and cartilage formation (37). Elevated expression of BMP-2 and

BMP-4 in SC lesions further supports their key role in

chondrification (38), while

overexpression of C-erbB-2 in certain PSC tissue samples may be

associated with synovial cell proliferation and disruptions in

signaling pathways (39).

Moreover, abnormal proliferation of CD34+ progenitor cells, in

conjunction with TWIST1, TGF-β1 and Harmane, may promote osteogenic

differentiation, accelerating chondrification and calcification

processes (40). Synovial

hyperplasia, angiogenesis and proteoglycan deposition are key

pathological features of SC lesions (31). By contrast, the inflammatory

microenvironment in SSC is primarily driven by joint damage, with

its inflammatory state closely associated with the progression of

the primary disease. Furthermore, synovial macrophages, through

M1/M2 polarization, carry out a key role in cartilage degradation

and regeneration. M1 macrophages promote inflammation and cartilage

degradation, while M2 macrophages support cartilage repair and

regeneration (35).

| Figure 5.Schematic diagram of the impact of

signaling pathway regulatory products, inflammatory

microenvironment and mechanical stress on the pathogenesis of SC.

i) Impact of factors: Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, GLI1, P21 and c-Myc

primarily promote the growth and proliferation of synovial cells

and inhibit apoptosis. Aggrecan, calcium ions, Col2A1 and MMPs

promote the synthesis of cartilage matrix and cartilage repair.

VEGF-A promotes cell proliferation and angiogenesis through the

MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. ii) Impact of an inflammatory

microenvironment: CD+macrophages and

HLA-DR+cells secrete inflammatory cytokines, such as

IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17 and IFN-γ. These cytokines enhance

synovial inflammation, strengthen immune responses and accelerate

synovial cell proliferation. iii) Impact of mechanical stress:

Mechanical stress upregulates the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, CD105

and CD90, promoting synovial cell proliferation, cartilage matrix

synthesis, chondrogenesis and calcification, further driving the

formation of chondromas. iv) Impact of other factors: Other

factors, such as C-erbB-2, promote the proliferation of synovial

cells through the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways and inhibit

apoptosis. The abnormal proliferation of CD34+progenitor

cells provides a source of cells for chondrogenesis and

calcification. TWIST1, TGF-β1 and harmine act synergistically to

further promote the formation and progression of SC. These factors

and mechanisms interact through different signaling pathways,

collectively driving the occurrence and development of SC. Bcl-2,

B-cell lymphoma 2; BMP-2/4, bone morphogenetic protein 2/4; c-Myc,

cellular Myc; Col2A1, collagen type IIα1; erbB-2, receptor

tyrosine-protein kinase ErbB-2; Gli1, glioma-associated oncogene

homolog 1; HLA-DR+, human leukocyte antigen-DR;

IL-6/17/1β, interleukin 6/17/1β; MAPK/ERK, mitogen-activated

protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MMPs, matrix

metalloproteinases; PI3K/Akt, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein

kinase B; SC, synovial chondromatosis; Smad, Smad family protein;

Sox9, SRY-box 9; TGF-βRI, transforming growth factor-β receptor I;

TNF-α/γ, tumor necrosis factor-α/γ; TWIST1, twist family BHLH

transcription factor 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth

factor. |

Role of mechanical stress in the

pathogenesis of SC

Mechanical stress carries out a key role in the

pathogenesis of SSC (Fig. 5).

Prolonged mechanical stress can induce synovial cell proliferation

and promote chondrification through the regulation of CD105 and

CD90 (33,41). Moreover, mechanical stimulation may

further enhance the expression of pro-inflammatory factors such as

TNF-α and IL-1β, promoting synovial cell proliferation and

chondrification (31). Under

mechanical stress, synovial stem cells may differentiate into

chondrocytes, ultimately leading to SC lesions. Patients with SSC

often exhibit subchondral bone sclerosis, joint space narrowing and

osteophyte formation in affected areas, suggesting that SSC may be

an adaptive proliferative response of the synovium to prolonged

mechanical stress (41).

Overall, PSC is primarily driven by signaling

pathway abnormalities, while SSC is more influenced by inflammation

and mechanical stress. Factors such as IL-6 and VEGF-A may promote

disease progression, but the specific roles of these mechanisms in

the disease process require further clarification. To the best of

our knowledge, there is currently no unified pathogenic model and

future research should focus on in-depth exploration of these

mechanisms and their key regulatory factors. A deeper understanding

of the pathogenesis of SC will provide theoretical support for

clinical molecular biological diagnosis and targeted drug

therapy.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of

SC

Diagnosis

SC manifests with a range of clinical symptoms. The

most common include persistent joint pain, typically rated between

5 and 7 on the VAS scale, which intensifies as the disease

progresses (3,8,9).

With SC, 75–85% of patients experience mechanical dysfunctions,

such as joint popping, locking and a reduced range of motion, often

associated with intra-articular loose bodies. A total of 85–90% of

patients present with recurrent joint swelling and increased local

skin temperature, indicating an inflammatory response. In patients

with a disease duration >3 years, nerve compression symptoms

(such as numbness in the branches of the trigeminal nerve) and

secondary osteoarthritis may develop. These symptoms not only

reflect the severity of the disease but also provide key clues for

clinical diagnosis and management (3,8,9).

They offer clinicians essential insights to assess the severity of

the disease and progression. In practice, doctors typically devise

personalized treatment plans based on both the patient's subjective

symptoms and imaging results.

The clinical presentation of early-stage SC is

characterized by a lack of specificity, which poses considerable

difficulties for accurate diagnosis. Ultrasonography (US), x-ray,

computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and

pathological examinations form a diagnostic system that progresses

from basic to advanced methods, complementing each other. Among

these, MRI is regarded as the most optimal imaging modality,

capable of thoroughly evaluating synovial lesions and surrounding

tissue involvement. However, pathological examination remains the

definitive diagnostic tool (42).

Furthermore, other diagnostic methods have become increasingly

important in diagnosing SC.

US

US is primarily used for early screening and

postoperative monitoring. It can detect synovial thickening,

effusion and free bodies and dynamically assess the activity of the

lesions (7,42). However, US has limited sensitivity

for detecting non-calcified lesions and is inadequate in accurately

determining the size and number of cartilage nodules, particularly

in deep joints such as the hip, thus limiting its role in final

diagnosis (14).

X-ray

X-ray remains the first choice for imaging in SC,

effectively screening for lesions and providing preliminary staging

information (14). The typical

X-ray features of PSC include multiple spherical or ring-shaped

calcifications within the joint cavity, while SSC typically

involves calcification patterns that are irregular and may overlap

with osteoarthritis calcifications, complicating the diagnosis

(7,42). Additionally, x-ray is less

sensitive for detecting extra-articular SC and soft tissue

calcifications may be misdiagnosed as tendon calcifications.

Non-calcified SC or early-stage cases may appear normal on x-rays,

necessitating further evaluation with CT or MRI (43).

CT

CT carries out a key role in the early diagnosis of

SC, especially in evaluating fine calcifications and bone

destruction (7). The high

resolution of CT allows clear visualization of small calcification

points, ring-like calcifications and bone erosion, making it

suitable for complex lesions or cases involving bone destruction

(42,44). Furthermore, the multi-planar

reconstruction function of CT helps analyze the relationship

between calcified nodules, bone, synovium and soft tissues, which

is especially advantageous in areas such as the hip, shoulder and

ankle (44,45). However, CT is less effective for

assessing synovial thickening and non-calcified cartilage nodules

and MRI remains necessary for further analysis (7,45).

MRI

MRI is considered the gold standard for imaging

diagnosis of SC, as it provides a comprehensive assessment of

lesion extent, free body characteristics, soft tissue involvement

and potential malignant transformation risks (7,46).

MRI can detect non-calcified free bodies and clearly visualize

synovial proliferation and cartilage matrix structure,

demonstrating excellent diagnostic capability for both PSC, SSC and

extra-articular SC (8). Compared

with x-ray and CT, MRI offers considerable advantages in early

detection of lesions, synovial activity assessment and

postoperative follow-up (39). A

study by Kramer et al (47)

categorized the MRI presentation of SC into three patterns: Type A,

typical calcified type, high T2 signal with focal low-signal areas,

corresponding to Milgram Stage II; Type B, non-calcified type, high

T2 signal without focal low-signal areas, corresponding to Milgram

Stage I; and Type C, advanced ossification type, high signal

intensity areas resembling fat, indicating cartilage matrix

enrichment or malignant potential. This classification aids in

determining the disease stage and selecting the most appropriate

treatment (Table II).

Additionally, MRI can help distinguish SC from SS, PVNS and other

lesions, improving diagnostic accuracy (48). In early-stage SC, extra-articular

SC and suspected malignant cases, the diagnostic value of MRI is

irreplaceable. However, the high cost and longer examination time

may necessitate complementary CT or X-ray evaluations for certain

cases.

| Table II.Milgram staging of synovial

chondromatosis with corresponding Kramer MRI types and recommended

surgical strategies (24,47). |

Table II.

Milgram staging of synovial

chondromatosis with corresponding Kramer MRI types and recommended

surgical strategies (24,47).

| Stage | Stage name | Pathological

features | MRI findings

(Kramer type) | Recommended

surgical strategy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Stage I | Synovial

proliferation phase | Active

cartilaginous metaplasia of the synovium without loose body

formation. May be misdiagnosed as synovitis. | Kramer Type B: High

T2 signal without low-signal calcification. | Early arthroscopic

synovectomy is recommended to prevent disease progression and

reduce recurrence risk. | (24,25,47,66,67) |

| Stage II | Transitional phase

with loose bodies | Persistent synovial

activity with formation of intra-articular loose bodies. | Kramer Type A: High

T2 signal with focal low-signal calcifications. | Arthroscopic

removal of loose bodies. Synovectomy as needed depending on

synovial activity. |

|

| Stage III | Loose body dominant

phase | Synovial activity

has diminished. Numerous mature loose bodies are present, often

causing mechanical symptoms. | Kramer Type C:

Mixed high signals with fat-like or erosive features. | Focus on loose body

removal. Synovectomy is usually unnecessary and reserved for

specific symptoms. |

|

Histopathology

Although imaging carries out a key role in

diagnosing SC, the final diagnosis depends on pathological

analysis, which includes gross pathological and microscopic

evaluations (29). Gross pathology

in PSC typically reveals multiple translucent blue-white cartilage

nodules with smooth surfaces; by contrast, SSC presents as

localized cartilaginous metaplasia accompanied by chronic synovial

inflammation and fibrosis (49,50).

Microscopic examination of PSC reveals abundant undifferentiated

chondrocytes within the synovium, rich matrix and uniform cellular

arrangement, while SSC exhibits inflammatory cell infiltration,

cartilage fragment deposition and fibrous tissue proliferation

(49,50).

In pathological diagnosis, the gene fusion of

FN1-ACVR2A and the overexpression of C-erbB-2 protein can indicate

the clonal proliferation characteristics of PSC (22,38).

This biomarker has considerable clinical value: In terms of

diagnosis, the sensitivity of FN1-ACVR2A fusion for identifying SS

is 92%, and the specificity is 100% (22); in terms of prognosis, patients with

positive fusion have a 2.3-fold increased risk of recurrence, and

the overexpression of C-erbB-2 is negatively associated with

chemotherapy response (38). In

terms of treatment, patients with positive fusion are recommended

to undergo extensive synovectomy and extended follow-up for ≥5

years, while those with negative fusion can undergo local resection

combined with routine 3-year follow-up (22,38).

Although FN1-ACVR2A has not been included in the diagnostic

criteria for malignancy, its status should be noted in the

pathological report and integrated with imaging and clinical

manifestations for risk-stratification management (23).

Other diagnostic methods

In addition to imaging and pathological examination,

several auxiliary methods can aid in the diagnosis of SC. Electron

microscopy can be used to observe the ultrastructural features of

SC tissues, such as bone-cartilage differentiation, but its

clinical application remains limited (51). Arthroscopy allows direct assessment

of synovial proliferation and free bodies but is unable to

precisely measure synovial thickness and the extent of soft tissue

infiltration (10). Artificial

intelligence (AI)-assisted diagnosis has shown promise in SC

imaging analysis, particularly in using deep learning techniques to

identify non-calcified SC, assess recurrence risks and predict

malignant tendencies. However, this technology is still in the

research phase and requires further validation before clinical

implementation (52).

In summary, the diagnosis of SC should combine

multiple diagnostic methods. US is useful for early screening and

postoperative follow-up, while x-ray is the preferred method to

identify calcified lesions, although non-calcified cases may be

missed. CT can precisely assess calcification patterns and bone

destruction, while MRI provides a comprehensive evaluation of

synovial lesions, loose bodies and soft tissue involvement, making

it suitable for early diagnosis and the assessment of malignancy.

Definitive diagnosis still requires pathological analysis. The

diagnosis of SC relies on a comprehensive evaluation of imaging and

pathology, and AI-assisted diagnosis shows potential, but further

research is needed for validation.

Differential diagnosis

SC must be differentiated from all diseases that may

cause intra-articular free bodies or synovial proliferation,

including crystal deposition diseases (such as calcific tendinitis

and hydroxyapatite deposition), osteochondral free bodies (such as

osteochondritis dissecans), arthritis-related lesions (such as

rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative arthritis and osteoarthritis),

synovial proliferative diseases [such as pigmented villonodular

synovitis (PVNS) or synovial hemangiomas], and other conditions

(such as giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath, elbow joint

tuberculosis, tumor-induced calcification and periarticular

scleroderma) (27,53,54).

The majority of these diseases can be distinguished through

clinical presentation, imaging and pathological examination.

However, the differential diagnosis between PSC and SS is

particularly notable, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary

overtreatment, while failure to diagnose may delay treatment and

compromise the outcome (52).

Imaging differentiation

Imaging findings are the cornerstone for

differentiating SC from SS (27).

SC typically presents with cartilage nodules on the synovial

surface, multiple free bodies in the joint and mild synovial

thickening (2). By contrast, SS

appears as an irregular soft tissue mass around the joint, with

fewer free bodies (47). The

calcification patterns in SC are typically ring-like, clustered or

lobulated, which are characteristic of cartilage calcification

(7,42). Conversely, SS presents as diffuse,

patchy or punctate calcification with uneven distribution (52). SC lesions are generally confined to

the synovium and rarely infiltrate deep tissues, whereas SS is more

prone to invasion of muscles, nerves and blood vessels, with

widespread edema and soft tissue infiltration visible on MRI

(21,52). The degree of local tissue

destruction also differs. SC shows mild bone erosion on the joint

surface, with localized bone defects visible on CT and preserved

bone cortex, while SS tends to cause bone destruction, periosteal

reaction and marrow infiltration, indicating a higher degree of

aggressiveness (7,21,52).

Histopathological differentiation

Histopathological examination further aids in

distinguishing SC from SS. Microscopically, PSC shows translucent

cartilage nodules with a regular arrangement of chondrocytes and

few signs of atypia, necrosis or abnormal mitosis. By contrast, SS

is characterized by high cellular density, disorganized arrangement

of small round cells, active mitotic figures and may exhibit a

biphasic pattern (epithelial-like and spindle cells) (42,55,56).

Molecular markers can provide more definitive diagnostic evidence.

In PSC, Bcl-2 protein expression is low, whereas SS shows high

Bcl-2 expression. Additionally, SYT-SSX gene fusion [t

(X;18)(p11.2; q11.2)] is a specific marker for SS, which is not

present in SC (Table III)

(55).

| Table III.Comparative analysis of SC and

SS. |

Table III.

Comparative analysis of SC and

SS.

| Category | SC | SS | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Clinical

features | Benign lesion, rare

malignant transformation (5%), predominantly affects large joints

(knees/hips), presenting with joint pain, crepitus and limited

mobility, peak incidence: Middle-aged adults (30–50 years). | Malignant tumor

with aggressive behavior, typically occurs in deep soft tissues

near joints, presenting as a rapidly growing mass with neuropathic

pain/numbness, peak incidence: Young adults (15–40 years; median 25

years). | (1,12–14,20) |

| Imaging

findings | MRI: Joint space

expansion with homogeneous T2-hyperintense nodules/target sign of

loose bodies, CT: Multiple calcified/ossified loose bodies. | MRI:

Heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass with

hemorrhage/necrosis, CT: Minimal calcification, frequent bone

invasion. | (7,21,42,46,47,52) |

| Histopathology | Synovial

chondrometaplasia forming hyaline cartilage nodules, no cellular

atypia, low proliferative activity, IHC: Strong VEGF-A

expression. | Biphasic

(epithelioid + spindle) or monophasic spindle patterns, Marked

cellular atypia with frequent mitoses, IHC: EMA/CK/BCL-2 positive,

SS18-SSX fusion+. | (29,42,49,50,55,56) |

| Molecular

markers | No specific

mutations, potential Hedgehog/TGF-β pathway involvement. | Pathognomonic

t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) translocation with SS18-SSX fusion (>95%

cases). | (28,29,30,55) |

| Management and

prognosis | Surgical excision

of loose bodies + synovectomy, low recurrence (<10%), excellent

prognosis. | Wide resection +

chemo/radiotherapy, high local recurrence, 5-year survival 50–80%,

metastatic risk (lungs/bones). | (1,17,21,55) |

In summary, the typical imaging features of SC

include loose bodies, multiple calcifications and localized

synovial thickening, which are indicative of a benign mass, while

SS is characterized by aggressive growth, soft tissue infiltration,

bone destruction and specific gene fusions, suggesting malignancy.

A combined approach of imaging, pathology and molecular testing can

help improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce misdiagnosis and optimize

clinical management. Although SC and SS show notable differences in

imaging and molecular features, diagnosis remains challenging due

to overlapping imaging characteristics with other diseases and the

need for improved sensitivity and specificity of molecular markers.

Future research should focus on optimizing the combined use of

imaging diagnostics and molecular testing, as well as exploring the

potential of AI-assisted diagnosis to enhance early diagnostic

accuracy and efficiency.

Treatment of SC

The treatment of SC should be individualized based

on the extent of the lesion, symptom severity, and the functional

requirements of the patient. Although SC has a certain degree of

self-limitation, the mechanical irritation from free bodies and

secondary joint damage can exacerbate symptoms, necessitating

active intervention. Current treatment options include conservative

and surgical approaches, with surgery remaining the primary

treatment modality (57). However,

the necessity of synovectomy continues to be debated (58).

Non-surgical treatment is appropriate for patients

with mild or no symptoms, primarily involving non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs, activity modification and physical therapy

to alleviate pain and delay disease progression (59,60).

Additionally, biological agents such as FGF9 signaling pathway

inhibitors and TNF inhibitors may provide novel strategies for

non-surgical management of SC, although large-scale clinical

validation is lacking (61,62).

Currently, chemotherapy and radiotherapy lack clear evidence of

efficacy in SC and are rarely used clinically, showing no

significant advantages pre- or postoperatively. By contrast,

radioactive synovectomy, especially with 188 rhenium-sulfide

colloids, has shown potential in lesion removal and may reduce

postoperative recurrence risk (63,64).

Surgical treatment remains the first-line option for

patients with notable symptoms, impaired joint function or

secondary joint damage (58).

Arthroscopic surgery is widely used in cases with localized lesions

and small joint cavities due to its minimally invasive nature,

rapid recovery and preservation of post-operative function

(65). Open surgery is suitable

for patients with extensive synovial hyperplasia or involvement

both inside and outside the joint, as it allows for more complete

lesion removal and reduces the risk of recurrence, particularly in

severe cases of knee SC (57,58).

The necessity of synovectomy in surgical treatment

remains contested. Certain studies suggest that removing only the

free cartilage bodies may suffice to control the condition, while

others argue that combining synovectomy can reduce the recurrence

rate (64,66,67).

The Milgram staging system (24)

may help explain this controversy: Stage I, where there is no free

body, may necessitate synovectomy; Stage II, with free body

formation, allows for arthroscopic removal of cartilage bodies

while preserving the synovium; Stage III, with multiple free bodies

that are no longer forming, prioritizes free body removal with less

emphasis on synovectomy (66,67).

Furthermore, while synovectomy can reduce recurrence rates, it may

increase postoperative complications and decisions should be based

on the stage of the lesion and individual risk of recurrence. Joint

replacement surgery is indicated for patients with severe joint

destruction and widespread osteoarthritis (68). As SC may continue to form free

bodies, the long-term stability of joint replacements remains an

area for further research (69).

In summary, the treatment of SC primarily involves

surgery, with arthroscopy as the preferred method; open surgery is

considered for extensive or recurrent cases. The necessity of

synovectomy depends on the assessment of the stage of the disease

and the risk of recurrence. In the future, SC treatment may move

towards precision medicine, including molecular targeted therapy,

imaging-assisted decision-making and novel surgical strategies, to

optimize clinical management and improve long-term prognosis.

Conclusion

Despite pronounced progress in understanding the

pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies of SC, challenges remain in

elucidating the mechanisms of pathological transformation and in

the pursuit of precision medicine for this condition. The

pathogenesis of PSC is primarily driven by abnormalities in the

Hedgehog, FGF9/FGFR3 and TGF-β signaling pathways, while SSC is

more influenced by inflammatory microenvironments and mechanical

stress. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these

processes are not yet fully understood and the risk of malignancy

and the biological basis of SC remain inconclusive. Although MRI is

considered the gold standard for diagnostic imaging, and

AI-assisted diagnosis shows promising potential, further clinical

validation is required for widespread implementation. Surgical

intervention remains the cornerstone of treatment, with arthroscopy

being suitable for localized lesions, while open surgery is

preferred for extensive or recurrent cases. The necessity of

synovectomy varies depending on the stage of the disease, and no

unified standard currently exists. Current research is primarily

focused on the molecular mechanisms of SC, predictive models for

recurrence and risk of malignancy, exploration of molecular

diagnostic techniques and the application of AI in early diagnosis

and personalized treatment. Future research should continue to

concentrate on the hierarchical regulation of signaling pathways,

the role of the inflammatory microenvironment in disease

progression and the optimization of precision treatment strategies

to enhance early diagnosis, reduce the risk of recurrence and

improve long-term patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was supported by the Technology Innovation

Leading Program of Shaanxi (grant no. 2023KXJ-095), the Shaanxi

Provincial People's Hospital Science and Technology Talent Support

Program for Elite Talents (grant no. 2021JY-50) and the Shaanxi

Provincial People's Hospital Science and Technology Development

Incubation Foundation (grant no. 2023YJY-39).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

HL conceived the topic of study. XD made a

substantial contribution to data interpretation and analysis and

wrote and prepared the draft of the manuscript. HL supervised the

present review and provided key revisions. XD, SL and HL

contributed to manuscript revision and have read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, ChatGPT-4.0 by

OpenAI and DeepSeek-R1 were used for native language editing and

proofreading for improving readability. AI tools were not used for

any other purposes. The manuscript was subsequently revised and

edited by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the

final content of this manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

Bcl-2

|

B-cell lymphoma 2

|

|

BMP-2/4

|

bone morphogenetic protein 2/4

|

|

C-erbB-2

|

receptor tyrosine-protein kinase

ErbB-2

|

|

Col2A1

|

collagen type IIα1

|

|

Col3A1

|

collagen type IIIα1

|

|

C-Myc

|

cellular Myc

|

|

FGF2/9

|

fibroblast growth factor 2/9

|

|

FGFR1/2/3

|

fibroblast growth factor receptor

1/2/3

|

|

GLI1

|

GLI family zinc finger 1

|

|

HLA-DR+

|

human leukocyte antigen-DR

|

|

IFN-γ

|

interferon γ

|

|

IGF-1

|

insulin-like growth factor 1

|

|

IL-6/17/1β

|

interleukin 6/17/1β

|

|

IL-6R

|

IL-6 receptor

|

|

JAK/STAT

|

Janus kinase/signal transducer and

activator of transcription

|

|

MAPK/ERK

|

mitogen-activated protein

kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase

|

|

MMPs

|

matrix metalloproteinases

|

|

MTOR

|

mechanistic target of rapamycin

|

|

PI3K/Akt

|

phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein

kinase B

|

|

PTC1

|

Patched 1

|

|

Smad2/3/4

|

Smad family proteins 2/3/4

|

|

Sox9

|

SRY-box 9

|

|

TGF

|

transforming growth factor

|

|

TNF

|

tumor necrosis factor

|

|

TWIST1

|

twist family BHLH transcription

factor 1

|

|

VEGF-A

|

vascular endothelial growth factor

A

|

|

SC

|

synovial chondromatosis

|

|

PSC

|

primary SC

|

|

SSC

|

secondary SC

|

|

US

|

ultrasonography

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

AI

|

artificial intelligence

|

References

|

1

|

Etemad-Rezaie A, Tarchala M and Howard A:

Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the shoulder in pediatric

patient: Case report and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt

Surg. 10:1060–1064. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Braun S, Flevas DA, Sokrab R, Ricotti RG,

Rojas Marcos C, Pearle AD and Sculco PK: De novo synovial

chondromatosis following primary total knee arthroplasty: A case

report. Life (Basel). 13:13662023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wei JN, Ghislain NA, Li YG and Wu XT:

Disseminated knee synovial chondromatosis treated by arthroscopy

and combined anterior and posterior approaches. J Clin Exp Orthop.

1:12015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Fajardo M: Recurrent synovial

chondromatosis of the finger. Orthopedics. 44:e454–e457. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mirza FA and Vasquez RA: Surgical

management of multi-level cervical spine synovial chondromatosis.

Asian J Neurosurg. 16:367–371. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pirmorad S, Pirmorad S, Rab KZ and Komath

D: 69Incidental intra-operative finding of synovial chondromatosis

of the temporomandibular joint observed through an arthroscope. Br

J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 62:e792024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC and

Gajewski DA: Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with

radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 27:1465–1488.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wengle LJ, Hauer TM, Chang JS and

Theodoropoulos J: Systematic arthroscopic treatment of synovial

chondromatosis of the knee. Arthrosc Tech. 10:e2265–e2270. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Neumann JA, Garrigues GE, Brigman BE and

Eward WC: Synovial chondromatosis. JBJS Rev. 4:e22016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Afzal S, Kazemian G, Baroutkoub M,

Amouzadeh Omrani F, Ahmadi A and Tavakoli Darestani R: Arthroscopic

management of ankle primary synovial chondromatosis (Reichel's

syndrome): A case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case

Rep. 111:1088322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jang BG, Huh KH, Kang JH, Kim JE, Yi WJ,

Heo MS and Lee SS: Imaging features of synovial chondromatosis of

the temporomandibular joint: A report of 34 cases. Clin Radiol.

76:627.e1–627.e11. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tripathy SR, Parida MK, Thatoi PK, Mishra

A and Das BK: Primary synovial chondromatosis (Reichel syndrome).

Lancet Rheumatol. 2:e5762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Alamiri N, Alfayez SM, Marwan Y, Groszman

L, Al Farii H and Burman M: Arthroscopic management of knee

synovial chondromatosis: A systematic review of outcomes and

recurrence. Int Orthop. 49:1037–1045. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ko E, Mortimer E and Fraire AE:

Extraarticular synovial chondromatosis: Review of epidemiology,

imaging studies, microscopy and pathogenesis, with a report of an

additional case in a child. Int J Surg Pathol. 12:273–280. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee LM, Zhu YM, Zhang DD, Deng YQ and Gu

Y: Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: A

clinical and arthroscopic study of 16 cases. J Craniomaxillofac

Surg. 47:607–610. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Evans S, Boffano M, Chaudhry S, Jeys L and

Grimer R: Synovial chondrosarcoma arising in synovial

chondromatosis. Sarcoma. 2014:6479392014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Memon F, Pawar ED, Gupta D and Yadav AK:

Diagnosis arthroscopic treatment of synovial chondromatosis of

glenohumeral joint: A case report. J Orthop Case Rep. 11:59–62.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gatt T and Portelli M: Recurrence of

primary synovial chondromatosis (Reichel's Syndrome) in the ankle

joint following surgical excision. Case Rep Orthop.

2021:99226842021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

de Sa D, Horner NS, MacDonald A, Simunovic

N, Ghert MA, Philippon MJ and Ayeni OR: Arthroscopic surgery for

synovial chondromatosis of the hip: A systematic review of rates

and predisposing factors for recurrence. Arthroscopy.

30:1499–1504.e2. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Davis RI, Hamilton A and Biggart JD:

Primary synovial chondromatosis: A clinicopathologic review and

assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 29:683–688. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

McCarthy C, Anderson WJ, Vlychou M,

Inagaki Y, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL and Athanasou NA: Primary

synovial chondromatosis: A reassessment of malignant potential in

155 cases. Skeletal Radiol. 45:755–762. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Amary F, Perez-Casanova L, Ye H, Cottone

L, Strobl AC, Cool P, Miranda E, Berisha F, Aston W, Rocha M, et

al: Synovial chondromatosis, soft tissue chondroma: Extraosseous

cartilaginous tumor defined by FN1 gene rearrangement. Mod Pathol.

32:1762–1771. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Choi JH and Ro JY: The 2020 WHO

classification of tumors of soft tissue: Selected changes and new

entities. Adv Anat Pathol. 28:44–58. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Milgram JW: Synovial osteochondromatosis:

A histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am.

59:792–801. 1977. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gerard Y, Shall A and Ameil M: Synovial

osteochondromatosis. Therapeutic indications based on a

histological classification. Chirurgie. 119:190–194. 1993.(In

French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Villacin AB, Brigham LN and Bullough PG:

Primary, secondary synovial chondrometaplasia: Histopathologic and

clinicoradiologic differences. Hum Pathol. 10:439–451. 1979.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Habusta SF, Mabrouk A and Tuck JA:

Synovial chondromatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls

Publishing; Treasure Island, FL: 2017

|

|

28

|

Hopyan S, Nadesan P, Yu C, Wunder J and

Alman BA: Dysregulation of hedgehog signalling predisposes to

synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 206:143–150. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ichikawa J, Imada H, Kawasaki T and Haro

H: Opinion: The nature of primary and secondary synovial

chondromatosis: Importance of pathological findings. Front Oncol.

13:12818902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Alcaraz MJ, Megías J, García-Arnandis I,

Clérigues V and Guillén MI: New molecular targets for the treatment

of osteoarthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 80:13–21. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wake M, Hamada Y, Kumagai K, Tanaka N,

Ikeda Y, Nakatani Y, Suzuki R and Fukui N: Up-regulation of

interleukin-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor-A in the

synovial fluid of temporomandibular joints affected by synovial

chondromatosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 51:164–169. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li Y, Cai H, Fang W, Meng Q, Li J, Deng M

and Long X: Fibroblast growth factor 2 involved in the pathogenesis

of synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular joint. J Oral

Pathol Med. 43:388–394. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mansor Y, Perets I, Close MR, Mu BH and

Domb BG: In search of the spherical femoroplasty: Cam overresection

leads to inferior functional scores before and after revision hip

arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 46:2061–2071. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li Y, El Mozen LA, Cai H, Fang W, Meng Q,

Li J, Deng M and Long X: Transforming growth factor beta 3 involved

in the pathogenesis of synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular

joint. Sci Rep. 5:88432015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Crawford R and Xiao

Y: Synovial macrophages in cartilage destruction and

regeneration-lessons learnt from osteoarthritis and synovial

chondromatosis. Biomed Mater. 17:0120012022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Chen WK, Zhang HJ, Liu J, Dai Z and Zhan

XL: COL3A1 is a potential diagnostic biomarker for synovial

chondromatosis and affects the cell cycle and migration of

chondrocytes. Int Immunopharmacol. 127:1114162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yoshitake H, Kayamori K, Wake S, Sugiyama

K and Yoda T: Biomarker expression related to chondromatosis in the

temporomandibular joint. Cranio. 39:362–366. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Nakanishi S, Sakamoto K, Yoshitake H, Kino

K, Amagasa T and Yamaguchi A: Bone morphogenetic proteins are

involved in the pathobiology of synovial chondromatosis. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 379:914–919. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Davis RI, Foster H and Biggart DJ: C-erb

B-2 staining in primary synovial chondromatosis: A comparison with

other cartilaginous tumours. J Pathol. 179:392–395. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li X, Sun H, Li D, Cai Z, Xu J and Ma R:

CD34+ synovial fibroblasts exhibit high osteogenic potential in

synovial chondromatosis. Cell Tissue Res. 397:37–50. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sink J, Bell B and Mesa H: Synovial

chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: Clinical, cytologic,

histologic, radiologic, therapeutic aspects, and differential

diagnosis of an uncommon lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol. 117:e269–e274. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Vasudevan R, Jayakaran H, Ashraf M and

Balasubramanian N: Synovial chondromatosis of the knee joint:

Management with arthroscopy-assisted ‘sac of pebbles’ extraction

and synovectomy. Cureus. 16:e693782024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tekaya AB, Hamdi O, Bellil M, Saidane O,

Rouached L, Bouden S, Tekaya R, Salah MB, Mahmoud I and Abdelmoula

L: Synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder in rheumatoid arthritis:

A case report and brief review of the literature. Curr Rheumatol

Rev. 19:362–366. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lee HJ, Han W and Kim K: Secondary

synovial chondromatosis of the subacromial subdeltoid bursa with

coexisting glenohumeral osteoarthritis: Case report. Medicine

(Baltimore). 100:e277962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhu Y, Gao G, Luan S, Wu K, Wang H, Zhang

Y, Zhang X, Wang J and Xu Y: Longitudinal assessment of clinical

outcomes after arthroscopic treatment for hip synovial

chondromatosis, the effect of residual loose bodies: Minimum 4-year

and 8-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 52:2306–2313. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Terra BB, Moraes EW, de Souza AC, Cavatte

JM, Teixeira JC and De Nadai A: Arthroscopic treatment of synovial

osteochondromatosis of the elbow. Case report and literature

review. Rev Bras Ortop. 50:607–612. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kramer J, Recht M, Deely DM, Schweitzer M,

Pathria MN, Gentili A, Greenway G and Resnick D: MR appearance of

idiopathic synovial osteochondromatosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr.

17:772–776. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Poutoglidou F, Metaxiotis D and

Mpeletsiotis A: Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee joint

in a 10-year-old patient treated with an all-arthroscopic

synovectomy: A case report. Cureus. 12:e119292020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yadav SK, Rajnish RK, Kumar D, Khera S,

Elhence A and Choudhary A: Primary synovial chondromatosis of the

ankle in a child: A rare case presentation and review of

literature. J Orthop Case Rep. 13:5–10. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Han W, Luo H, Zhao Y, He Z, Guo C and Meng

J: Retrospective study of synovial chondromatosis of the

temporomandibular joint: Clinical and histopathologic analysis and

the early-stage imaging features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol. 137:215–223. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Beger AW, Millard JA, Bresnehan A, Dudzik

B and Kunigelis S: Primary synovial chondromatosis: An elemental

investigation of a rare skeletal pathology. Folia Morphol (Warsz).

81:685–693. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Huang S, Yang J, Fong S and Zhao Q:

Artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis, prognosis:

Opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 471:61–71. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhou N, Fang K, Arthur VDT, Yi R, Xiang F,

Wen J and Xiao S: Synovial chondromatosis combined with synovial

tuberculosis of knee joint: A case report. BMC Pediatr. 22:82022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chraibi O, Rajaallah A, Lamris MA, El

Kassimi CE, Rafaoui A and Rafai M: Concurrent arboreal lipoma,

synovial chondromatosis in an osteoarthritic knee: Insights from a

rare case study-A surgical case report. Int J Surg Case Rep.

119:1097862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sperling BL, Angel S, Stoneham G, Chow V,

McFadden A and Chibbar R: Synovial chondromatosis, chondrosarcoma:

A diagnostic dilemma. Sarcoma. 7:69–73. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Furtado C, Zeitoun R, Remedios ID, Wilkes

J, Sumathi V and Tony G: Secondary chondrosarcoma arising in

synovial chondromatosis of wrist joint. J Orthop Case Rep.

13:30–36. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Park JH, Noh HK, Bada LP, Wang JH and Park

JW: Arthroscopic treatment for synovial chondromatosis of the

subacromial bursa: A case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol

Arthrosc. 15:1258–1260. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Rai AK, Bansal D, Bandebuche AR, Rahman

SH, Prabhu RM and Hadole BS: Extensive synovial chondromatosis of

the knee managed by open radical synovectomy: A case report with

review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep. 12:19–22. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Jung KA, Kim SJ and Jeong JH: Arthroscopic

treatment of synovial chondromatosis that possibly developed after

open capsular shift for shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports

Traumatol Arthrosc. 15:1499–1503. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Goyal S, Shrivastav S, Ambade R, Pundkar

A, Lohiya A and Naseri S: Unveiling the dance of crystals: A

surgical odyssey in the open excision of synovial chondromatosis in

the right knee. Cureus. 16:e569012024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Robinson D, Hasharoni A, Evron Z, Segal M

and Nevo Z: Synovial chondromatosis: The possible role of FGF 9 and

FGF receptor 3 in its pathology. Int J Exp Pathol. 81:183–189.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yu S, Wu M, Zhou G, Ishikawa T, Liang J,

Nallapothula D, Singh RR, Wang Q and Wang M: Potential utility of

anti-TNF drugs in synovial chondromatosis associated with

ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheum Dis. 22:2073–2079. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Vadi SK, Chouhan DK, Gorla AKR, Shukla J,

Sood A and Mittal BR: Potential adjunctive role of radiosynovectomy

in primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the knee: A case report.

Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 51:252–255. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Dheer S, Sullivan PE, Schick F, Karanjia

H, Taweel N, Abraham J and Jiang W: Extra-articular synovial

chondromatosis of the ankle: Unusual case with

radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiol Case Rep. 15:445–449.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Odluyurt M, Orhan Ö, Sezgin EA and Kanatli

U: Synovial chondromatosis in unusual locations treated with

arthroscopy: A report of three cases. Joint Dis Relat Surg Case

Rep. 1:063–066. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Fuerst M, Zustin J, Lohmann C and Rüther

W: Synovial chondromatosis. Orthopade. 38:511–519. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Reddivari AKR and Mehta P: Gastroparesis.

StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL:

2024

|

|

68

|

Houdek MT, Wyles CC, Rose PS, Stuart MJ,

Sim FH and Taunton MJ: High rate of local recurrence and

complications following total knee arthroplasty in the setting of

synovial chondromatosis. J Arthroplasty. 32:2147–2150. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Deinum J and Nolte PA: Total knee

arthroplasty in severe synovial osteochondromatosis in an

osteoarthritic knee. Clin Orthop Surg. 8:218–222. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|