Recently, it has been suggested that >90% of

human genes undergo alternative splicing (10). Different transcripts from the same

gene have the same or different expression pattern and functions

(11–14). Rosa et al (11) reported that six transcript variants

of ZNF695 are co-expressed in cancer cell lines, and transcript

variant one and three were predominantly expressed in leukemia.

Handschuh et al (12)

demonstrated that all three NPM1 transcripts are upregulated in

leukemia compared with control samples. However, Zeilstra et

al (13) reported that CD44

variant isoforms (CD44v), but not CD44s, have unique functions in

promoting adenoma initiation in Apc (Min/+) mice. In addition, the

H2AFY gene encodes H2A histone variant MacroH2A1, including two

isoforms (MacroH2A1.1 and MacroH2A1.2) (15). MacroH2A1.1 is predominantly expressed

in differentiated cells, while MacroH2A1.2 is preferentially

expressed over 1.1 in proliferative cells (14). The MacroH2A1.1 isoform presents as

pleiotropic tumor suppressor, by repressing cellular processes,

including cell proliferation, migration and invasion, whereas the

function of MacroH2A1.2 is mainly cancer-type dependent (14).

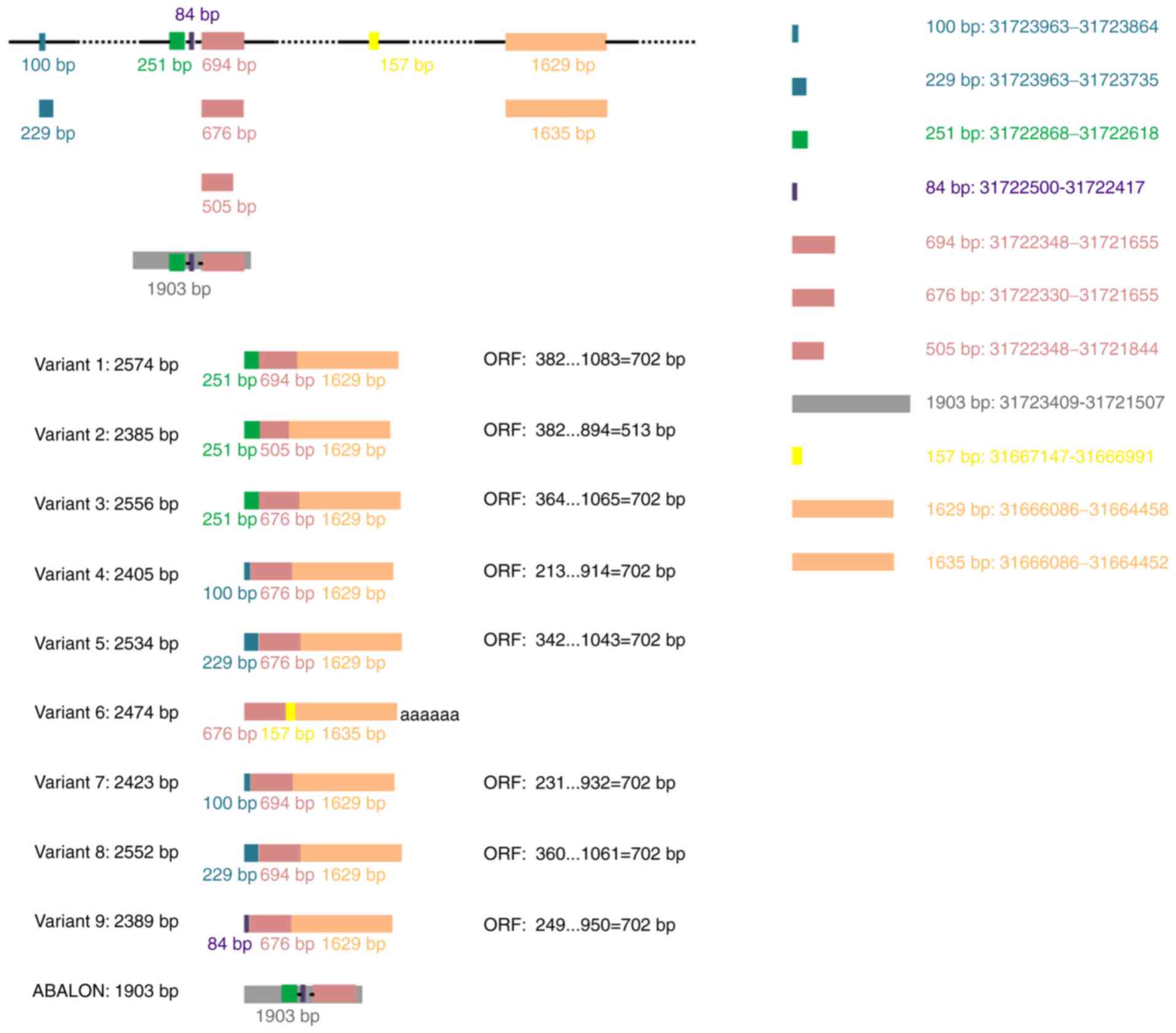

Variant 1 (GenBank: NM_138578.3) represents the

longest transcript, with 2,574 base pairs (bp) and contains an open

reading frame (ORF, 702 bp) (Table

I). It encodes a protein with 233 amino acids that displays 44%

amino acid identity with human BCL-2 (1). Thus, this splicing variant encodes the

longer isoform BCL-XL (B cell lymphoma-extra-large;

Bcl2l1), also known as BCL-xL. Variants 3 (NM_001317919.2), 4

(NM_001317920.2), 5 (NM_001317921.2), 7 (NM_001322239.2), 8

(NM_001322240.2) and 9 (NM_001322242.2) differ from variant 1 in

the 5′untranslated region, whereas their ORFs are the same as that

of variant 1. Therefore, they encode the same isoform as transcript

variant 1 (Table I). The ORFs and

amino acid sequence of BCL-XL are presented in Table II.

Variant 6 (NR_134257.1) contains a different

internal exon from variant 1 and is considered a non-coding RNA as

use of the same 5′-most supported translational start codon found

in variant 1 generates the potential for nonsense-mediated mRNA

decay. Another long non-coding RNA generated by alternative

splicing of the primary BCL-X RNA transcript is INXS (also

named ABALON, NR_131907.1), which is 1,903 bp in length (Table I).

The BH3 mimetics, such as ABT-199 (venetoclax),

ABT-737 and ABT-263 (navitoclax), are small molecules that mimic

the BH3 domains of BCL-2 family proapoptotic proteins (60,62).

They have been used to bind and antagonize the functions of BCL-2

and/or BCL-XL to promote cell death in hematological

malignancies (64–69).

Not applicable.

The present review was sponsored by Fujian

Provincial Health Technology Project of China (grant no.

2019-2-45), the Middle-aged and Young Teachers Foundation of Fujian

Educational Committee in China (grant no. JAT190835), the National

Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of

China (grant no. 201912631003) and the Fujian Provincial

Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of

China (grant no. 202012631031).

Not applicable.

WC conceived the present study. WC prepared the

original draft and the figure. JL performed the literature

analysis. WC revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Boise LH, González-García M, Postema CE,

Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nuñez G and Thompson CB:

Bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator

of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 74:597–608. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Opferman JT: Attacking cancer's Achilles

heel: Antagonism of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members. FEBS J.

283:2661–275. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Delbridge AR and Strasser A: The BCL-2

protein family, BH3-mimetics and cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ.

22:1071–1080. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang E and Korsmeyer SJ: Molecular

thanatopsis: A discourse on the BCL2 family and cell death. Blood.

88:386–401. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Motoyama N, Kimura T, Takahashi T,

Watanabe T and Nakano T: Bcl-x prevents apoptotic cell death of

both primitive and definitive erythrocytes at the end of

maturation. J Exp Med. 189:1691–1698. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Motoyama N, Wang F, Roth KA, Sawa H,

Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Negishi I, Senju S, Zhang Q, Fujii S, et

al: Massive cell death of immature hematopoietic cells and neurons

in Bcl-x-deficient mice. Science. 267:1506–1510. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shearn AI, Deswaerte V, Gautier EL,

Saint-Charles F, Pirault J, Bouchareychas L, Rucker EB III, Beliard

S, Chapman J, Jessup W, et al: Bcl-x inactivation in macrophages

accelerates progression of advanced atherosclerotic lesions in

Apoe(−/-) mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 32:1142–1149. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wagner KU, Claudio E, Rucker EB,

Riedlinger G, Broussard C, Schwartzberg PL, Siebenlist U and

Hennighausen L: Conditional deletion of the Bcl-x gene from

erythroid cells results in hemolytic anemia and profound

splenomegaly. Development. 127:4949–4958. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Silva M, Richard C, Benito A, Sanz C,

Olalla I and Fernández-Luna JL: Expression of Bcl-x in erythroid

precursors from patients with polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med.

338:564–571. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Johnson JM, Castle J, Garrett-Engele P,

Kan Z, Loerch PM, Armour CD, Santos R, Schadt EE, Stoughton R and

Shoemaker DD: Genome-wide survey of human alternative pre-mRNA

splicing with exon junction microarrays. Science. 302:2141–2144.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rosa R, Villegas-Ruíz V,

Caballero-Palacios MC, Pérez-López EI, Murata C, Zapata-Tarres M,

Cárdenas-Cardos R, Paredes-Aguilera R, Rivera-Luna R and

Juárez-Méndez S: Expression of ZNF695 transcript variants in

childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes (Basel).

10:7162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Handschuh L, Wojciechowski P, Kazmierczak

M, Marcinkowska-Swojak M, Luczak M, Lewandowski K, Komarnicki M,

Blazewicz J, Figlerowicz M and Kozlowski P: NPM1 alternative

transcripts are upregulated in acute myeloid and lymphoblastic

leukemia and their expression level affects patient outcome. J

Transl Med. 16:2322018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zeilstra J, Joosten SP, van Andel H, Tolg

C, Berns A, Snoek M, van de Wetering M, Spaargaren M, Clevers H and

Pals ST: Stem cell CD44v isoforms promote intestinal cancer

formation in Apc(min) mice downstream of Wnt signaling. Oncogene.

33:665–670. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Corujo D and Buschbeck M:

Post-translational modifications of H2A histone variants and their

role in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 10:592018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee Y, Hong M, Kim JW, Hong YM, Choe YK,

Chang SY, Lee KS and Choe IS: Isolation of cDNA clones encoding

human histone macroH2A1 subtypes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1399:73–77.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Harder JM, Ding Q, Fernandes KA, Cherry

JD, Gan L and Libby RT: BCL2L1 (BCL-X) promotes survival of adult

and developing retinal ganglion cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 51:53–59.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

International Stem Cell Initiative, ; Amps

K, Andrews PW, Anyfantis G, Armstrong L, Avery S, Baharvand H,

Baker J, Baker D, Munoz MB, et al: Screening ethnically diverse

human embryonic stem cells identifies a chromosome 20 minimal

amplicon conferring growth advantage. Nat Biotechnol. 29:1132–1144.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Willis SN, Chen L, Dewson G, Wei A, Naik

E, Fletcher JI, Adams JM and Huang DC: Proapoptotic Bak is

sequestered by Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL, but not Bcl-2, until displaced by

BH3-only proteins. Genes Dev. 19:1294–1305. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR and

Newmeyer DD: The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: A

primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science.

275:1132–1136. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kim CN, Wang X, Huang Y, Ibrado AM, Liu L,

Fang G and Bhalla K: Overexpression of Bcl-X(L) inhibits

Ara-C-induced mitochondrial loss of cytochrome c and other

perturbations that activate the molecular cascade of apoptosis.

Cancer Res. 57:3115–3120. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado

AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP and Wang X: Prevention of apoptosis by

Bcl-2: Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science.

275:1129–1132. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gottschalk AR, Boise LH, Thompson CB and

Quintáns J: Identification of immunosuppressant-induced apoptosis

in a murine B-cell line and its prevention by bcl-x but not bcl-2.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91:7350–7354. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Minn AJ, Rudin CM, Boise LH and Thompson

CB: Expression of bcl-xL can confer a multidrug resistance

phenotype. Blood. 86:1903–1910. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kamesaki S, Kamesaki H, Jorgensen TJ,

Tanizawa A, Pommier Y and Cossman J: Bcl-2 protein inhibits

etoposide-induced apoptosis through its effects on events

subsequent to topoisomerase II-induced DNA strand breaks and their

repair. Cancer Res. 53:4251–4256. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Walton MI, Whysong D, O'Connor PM,

Hockenbery D, Korsmeyer SJ and Kohn KW: Constitutive expression of

human Bcl-2 modulates nitrogen mustard and camptothecin induced

apoptosis. Cancer Res. 53:1853–1861. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Josefsson EC, James C, Henley KJ,

Debrincat MA, Rogers KL, Dowling MR, White MJ, Kruse EA, Lane RM,

Ellis S, et al: Megakaryocytes possess a functional intrinsic

apoptosis pathway that must be restrained to survive and produce

platelets. J Exp Med. 208:2017–2031. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kaluzhny Y, Yu G, Sun S, Toselli PA,

Nieswandt B, Jackson CW and Ravid K: Bcl-xL overexpression in

megakaryocytes leads to impaired platelet fragmentation. Blood.

100:1670–1678. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Delbridge AR, Aubrey BJ, Hyland C,

Bernardini JP, Di Rago L, Garnier JM, Lessene G, Strasser A,

Alexander WS and Grabow S: The BH3-only proteins BIM and PUMA are

not critical for the reticulocyte apoptosis caused by loss of the

pro-survival protein BCL-XL. Cell Death Dis. 8:e29142017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Afreen S, Bohler S, Müller A, Demmerath

EM, Weiss JM, Jutzi JS, Schachtrup K, Kunze M and Erlacher M:

BCL-XL expression is essential for human erythropoiesis and

engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 11:82020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hafid-Medheb K, Augery-Bourget Y, Minatchy

MN, Hanania N and Robert-Lézénès J: Bcl-XL is required for heme

synthesis during the chemical induction of erythroid

differentiation of murine erythroleukemia cells independently of

its antiapoptotic function. Blood. 101:2575–2583. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mason KD, Carpinelli MR, Fletcher JI,

Collinge JE, Hilton AA, Ellis S, Kelly PN, Ekert PG, Metcalf D,

Roberts AW, et al: Programmed anuclear cell death delimits platelet

life span. Cell. 128:1173–1186. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dolznig H, Habermann B, Stangl K, Deiner

EM, Moriggl R, Beug H and Müllner EW: Apoptosis protection by the

Epo target Bcl-X(L) allows factor-independent differentiation of

primary erythroblasts. Curr Biol. 12:1076–1085. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Garçon L, Rivat C, James C, Lacout C,

Camara-Clayette V, Ugo V, Lecluse Y, Bennaceur-Griscelli A and

Vainchenker W: Constitutive activation of STAT5 and Bcl-xL

overexpression can induce endogenous erythroid colony formation in

human primary cells. Blood. 108:1551–154. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Harb JG, Chyla BI and Huettner CS: Loss of

Bcl-x in Ph+ B-ALL increases cellular proliferation and does not

inhibit leukemogenesis. Blood. 111:3760–3769. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sato T, Hanada M, Bodrug S, Irie S, Iwama

N, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Golemis E, Fong L, Wang HG, et al:

Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 protein family analyzed

with a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

91:9238–9242. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Minn AJ, Boise LH and Thompson CB:

Bcl-x(S) anatagonizes the protective effects of Bcl-x(L). J Biol

Chem. 271:6306–6312. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ohta K, Iwai K, Kasahara Y, Taniguchi N,

Krajewski S, Reed JC and Miyawaki T: Immunoblot analysis of

cellular expression of Bcl-2 family proteins, Bcl-2, Bax, Bcl-X and

Mcl-1, in human peripheral blood and lymphoid tissues. Int Immunol.

7:1817–1825. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Shabaik A, Wang

HG, Irie S, Fong L and Reed JC: Immunohistochemical analysis of in

vivo patterns of Bcl-X expression. Cancer Res. 54:5501–5507.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liles WC and Klebanoff SJ: Regulation of

apoptosis in neutrophils-Fas track to death. J Immunol.

155:3289–3291. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sanz C, Benito A, Silva M, Albella B,

Richard C, Segovia JC, Insunza A, Bueren JA and Fernández-Luna JL:

The expression of Bcl-x is downregulated during differentiation of

human hematopoietic progenitor cells along the granulocyte but not

the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Blood. 89:3199–3204. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang L, Zhao H, Sun A, Lu S, Liu B, Tang

F, Feng Y, Zhao L, Yang R and Han ZC: Early down-regulation of

Bcl-xL expression during megakaryocytic differentiation of

thrombopoietin-induced CD34+ bone marrow cells in essential

thrombocythemia. Haematologica. 89:1199–1206. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gregoli PA and Bondurant MC: The roles of

Bcl-X(L) and apopain in the control of erythropoiesis by

erythropoietin. Blood. 90:630–640. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Moulding DA, Quayle JA, Hart CA and

Edwards SW: Mcl-1 expression in human neutrophils: Regulation by

cytokines and correlation with cell survival. Blood. 92:2495–2502.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Park JR, Bernstein ID and Hockenbery DM:

Primitive human hematopoietic precursors express Bcl-x but not

Bcl-2. Blood. 86:868–876. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Andreeff M, Jiang S, Zhang X, Konopleva M,

Estrov Z, Snell VE, Xie Z, Okcu MF, Sanchez-Williams G, Dong J, et

al: Expression of Bcl-2-related genes in normal and AML

progenitors: Changes induced by chemotherapy and retinoic acid.

Leukemia. 13:1881–1892. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kaufmann SH, Karp JE, Svingen PA,

Krajewski S, Burke PJ, Gore SD and Reed JC: Elevated expression of

the apoptotic regulator Mcl-1 at the time of leukemic relapse.

Blood. 91:991–1000. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lotem J and Sachs L: Regulation of bcl-2,

bcl-XL and bax in the control of apoptosis by hematopoietic

cytokines and dexamethasone. Cell Growth Differ. 6:647–653.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Campos L, Sabido O, Viallet A, Vasselon C

and Guyotat D: Expression of apoptosis-controlling proteins in

acute leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 33:499–509. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tsushima H, Urata Y, Miyazaki Y, Fuchigami

K, Kuriyama K, Kondo T and Tomonaga M: Human erythropoietin

receptor increases GATA-2 and Bcl-xL by a protein kinase

C-dependent pathway in human erythropoietin-dependent cell line

AS-E2. Cell Growth Differ. 8:1317–1328. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Findley HW, Gu L, Yeager AM and Zhou M:

Expression and regulation of Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and Bax correlate with

p53 status and sensitivity to apoptosis in childhood acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 89:2986–2993. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bogenberger JM, Kornblau SM, Pierceall WE,

Lena R, Chow D, Shi CX, Mantei J, Ahmann G, Gonzales IM, Choudhary

A, et al: BCL-2 family proteins as 5-Azacytidine-sensitizing

targets and determinants of response in myeloid malignancies.

Leukemia. 28:1657–1665. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gottardi D, Alfarano A, De Leo AM,

Stacchini A, Aragno M, Rigo A, Veneri D, Zanotti R, Pizzolo G and

Caligaris-Cappio F: In leukaemic CD5+ B cells the expression of

BCL-2 gene family is shifted toward protection from apoptosis. Br J

Haematol. 94:612–618. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Brousset P, Benharroch D, Krajewski S,

Laurent G, Meggetto F, Rigal-Huguet F, Gopas J, Prinsloo I, Pris J,

Delsol G, et al: Frequent expression of the cell death-inducing

gene Bax in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin's disease. Blood.

87:2470–2475. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wojtuszkiewicz A, Schuurhuis GJ, Kessler

FL, Piersma SR, Knol JC, Pham TV, Jansen G, Musters RJ, van Meerloo

J, Assaraf YG, et al: Exosomes secreted by apoptosis-resistant

acute myeloid leukemia (AML) blasts harbor regulatory network

proteins potentially involved in antagonism of apoptosis. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 15:1281–1298. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Datta R, Manome Y, Taneja N, Boise LH,

Weichselbaum R, Thompson CB, Slapak CA and Kufe D: Overexpression

of Bcl-XL by cytotoxic drug exposure confers resistance to ionizing

radiation-induced internucleosomal DNA fragmentation. Cell Growth

Differ. 6:363–370. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ibrado AM, Huang Y, Fang G and Bhalla K:

Bcl-xL overexpression inhibits taxol-induced Yama protease activity

and apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ. 7:1087–1094. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ibrado AM, Huang Y, Fang G, Liu L and

Bhalla K: Overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL inhibits Ara-C-induced

CPP32/Yama protease activity and apoptosis of human acute

myelogenous leukemia HL-60 cells. Cancer Res. 56:4743–4748.

1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Xie C, Edwards H, Caldwell JT, Wang G,

Taub JW and Ge Y: Obatoclax potentiates the cytotoxic effect of

cytarabine on acute myeloid leukemia cells by enhancing DNA damage.

Mol Oncol. 9:409–421. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Huang Y, Ibrado AM, Reed JC, Bullock G,

Ray S, Tang C and Bhalla K: Co-expression of several molecular

mechanisms of multidrug resistance and their significance for

paclitaxel cytotoxicity in human AML HL-60 cells. Leukemia.

11:253–257. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Salomons GS, Smets LA, Verwijs-Janssen M,

Hart AA, Haarman EG, Kaspers GJ, Wering EV, Der Does-Van Den Berg

AV and Kamps WA: Bcl-2 family members in childhood acute

lymphoblastic leukemia: Relationships with features at

presentation, in vitro and in vivo drug response and long-term

clinical outcome. Leukemia. 13:1574–1580. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Dole MG, Clarke MF, Holman P, Benedict M,

Lu J, Jasty R, Eipers P, Thompson CB, Rode C, Bloch C, et al:

Bcl-xS enhances adenoviral vector-induced apoptosis in

neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 56:5734–5740. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Sumantran VN, Ealovega MW, Nuñez G, Clarke

MF and Wicha MS: Overexpression of Bcl-XS sensitizes MCF-7 cells to

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 55:2507–2510.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Deng G, Lane C, Kornblau S, Goodacre A,

Snell V, Andreeff M and Deisseroth AB: Ratio of bcl-xshort to

bcl-xlong is different in good- and poor-prognosis subsets of acute

myeloid leukemia. Mol Med. 4:158–164. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER,

Ackler SL, Catron ND, Chen J, Dayton BD, Ding H, Enschede SH,

Fairbrother WJ, et al: ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2

inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat

Med. 19:202–208. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR,

Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges

J, Hajduk PJ, et al: An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces

regression of solid tumours. Nature. 435:677–681. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Tse C, Shoemaker AR, Adickes J, Anderson

MG, Chen J, Jin S, Johnson EF, Marsh KC, Mitten MJ, Nimmer P, et

al: ABT-263: A potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family

inhibitor. Cancer Res. 68:3421–3428. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Jilg S, Reidel V, Müller-Thomas C, König

J, Schauwecker J, Höckendorf U, Huberle C, Gorka O, Schmidt B,

Burgkart R, et al: Blockade of BCL-2 proteins efficiently induces

apoptosis in progenitor cells of high-risk myelodysplastic

syndromes patients. Leukemia. 30:112–123. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Lessene G, Czabotar PE, Sleebs BE, Zobel

K, Lowes KN, Adams JM, Baell JB, Colman PM, Deshayes K, Fairbrother

WJ, et al: Structure-guided design of a selective BCL-X(L)

inhibitor. Nat Chem Biol. 9:390–397. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Sleebs BE, Kersten WJ, Kulasegaram S,

Nikolakopoulos G, Hatzis E, Moss RM, Parisot JP, Yang H, Czabotar

PE, Fairlie WD, et al: Discovery of potent and selective

benzothiazole hydrazone inhibitors of Bcl-XL. J Med Chem.

56:5514–5540. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Konopleva M, Pollyea DA, Potluri J, Chyla

B, Hogdal L, Busman T, McKeegan E, Salem AH, Zhu M, Ricker JL, et

al: Efficacy and biological correlates of response in a phase II

study of venetoclax monotherapy in patients with acute myelogenous

leukemia. Cancer Discov. 6:1106–1117. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, Kahl BS,

Puvvada SD, Gerecitano JF, Kipps TJ, Anderson MA, Brown JR,

Gressick L, et al: Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed

chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 374:311–322. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J,

Coutre S, Seymour JF, Munir T, Puvvada SD, Wendtner CM, Roberts AW,

Jurczak W, et al: Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic

lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: A multicentre, open-label,

phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 17:768–778. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Lin KH, Winter PS, Xie A, Roth C, Martz

CA, Stein EM, Anderson GR, Tingley JP and Wood KC: Targeting

MCL-1/BCL-XL forestalls the acquisition of resistance to ABT-199 in

acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Rep. 6:276962016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Punnoose EA, Leverson JD, Peale F,

Boghaert ER, Belmont LD, Tan N, Young A, Mitten M, Ingalla E,

Darbonne WC, et al: Expression profile of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1

predicts pharmacological response to the BCL-2 selective antagonist

venetoclax in multiple myeloma models. Mol Cancer Ther.

15:1132–1144. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Schoenwaelder SM, Jarman KE, Gardiner EE,

Hua M, Qiao J, White MJ, Josefsson EC, Alwis I, Ono A, Willcox A,

et al: Bcl-xL-inhibitory BH3 mimetics can induce a transient

thrombocytopathy that undermines the hemostatic function of

platelets. Blood. 118:1663–1674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kile BT: The role of apoptosis in

megakaryocytes and platelets. Br J Haematol. 165:217–226. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Roberts AW, Seymour JF, Brown JR, Wierda

WG, Kipps TJ, Khaw SL, Carney DA, He SZ, Huang DC, Xiong H, et al:

Substantial susceptibility of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to BCL2

inhibition: Results of a phase I study of navitoclax in patients

with relapsed or refractory disease. J Clin Oncol. 30:488–496.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Khan S, Zhang X, Lv D, Zhang Q, He Y,

Zhang P, Liu X, Thummuri D, Yuan Y, Wiegand JS, et al: A selective

BCL-XL PROTAC degrader achieves safe and potent

antitumor activity. Nat Med. 25:1938–1947. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

He Y, Zhang X, Chang J, Kim HN, Zhang P,

Wang Y, Khan S, Liu X, Zhang X, Lv D, et al: Using

proteolysis-targeting chimera technology to reduce navitoclax

platelet toxicity and improve its senolytic activity. Nat Commun.

11:19962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Tao ZF, Hasvold L, Wang L, Wang X, Petros

AM, Park CH, Boghaert ER, Catron ND, Chen J, Colman PM, Czabotar

PE, et al: Discovery of a potent and selective BCL-XL inhibitor

with in vivo activity. ACS Med Chem Lett. 5:1088–1093. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wang Q, Wan J, Zhang W and Hao S: MCL-1 or

BCL-xL-dependent resistance to the BCL-2 antagonist (ABT-199) can

be overcome by specific inhibitor as single agents and in

combination with ABT-199 in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk

Lymphoma. 60:2170–2180. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Zhu Y, Doornebal EJ, Pirtskhalava T,

Giorgadze N, Wentworth M, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Niedernhofer LJ,

Robbins PD, Tchkonia T and Kirkland JL: New agents that target

senescent cells: The flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-XL

inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging (Albany NY). 9:955–963.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Wang L, Doherty GA, Judd AS, Tao ZF,

Hansen TM, Frey RR, Song X, Bruncko M, Kunzer AR, Wang X, et al:

Discovery of A-1331852, a First-in-Class, potent, and

orally-bioavailable BCL-XL inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett.

11:1829–1836. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kirkland JL and Tchkonia T: Cellular

senescence: A translational perspective. EBioMedicine. 21:21–28.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Perri M, Yap JL, Yu J, Cione E, Fletcher S

and Kane MA: BCL-xL/MCL-1 inhibition and RARγ antagonism work

cooperatively in human HL60 leukemia cells. Exp Cell Res.

327:183–191. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|