Introduction

Gliomas are the most common type of primary

intracranial tumors in adults, accounting for ~81% of malignant

brain tumors in the United States between 2014–2018 (1). According to the 2021 World Health

Organization (WHO) classification of central nervous system (CNS)

tumors, gliomas are divided into grades 1–4, with grades 1 and 2

classed as low-grade gliomas and grades 3 and 4 classed as

high-grade gliomas (2). Currently,

treatment methods for gliomas include maximal safe resection,

chemoradiotherapy (3) and emerging

therapies, such as immunotherapy (4) and tumor-treating field therapy

(5). Treatment outcomes for gliomas

are influenced by several factors, including the tumor size,

location, type, pathological grade and genetic characteristics.

Some gliomas are challenging to resect and may respond poorly to

radiation and chemotherapy, often resulting in suboptimal treatment

outcomes (6).

Gliomas account for ~81% of all malignant brain

tumors and 30% of all brain and CNS tumors (7). The global incidence is estimated at

5–6 cases per 100,000 individuals annually, with glioblastoma (GBM)

being the most aggressive subtype, representing 45–50% of all

gliomas (2). Patients typically

present with neurological symptoms such as persistent headaches,

seizures, cognitive impairment and focal deficits, which vary

according to tumor location and progression (8,9).

High-grade gliomas, particularly GBM, are associated with a poor

prognosis, with a median survival of ~15 months despite standard

therapies (10). Diagnosis is

primarily based on MRI, but definitive confirmation requires

histopathological and molecular assessment, including isocitrate

dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status and O6-methylguanine DNA

methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation (11,12).

Given the aggressive nature of gliomas and the challenges in

treatment, ongoing research aims to identify novel biomarkers and

therapeutic targets to improve patient outcomes.

As a newly discovered tumor-related gene, DEP domain

containing 1 (DEPDC1) was first identified in bladder cancer by

Kanehira et al (13) in

2007. More recently, the overexpression of DEPDC1 has been widely

reported in malignant tumors originating from several organs,

including the liver (14), lung

(15), colon (16), breast (17), bone (18) and prostate (19). Previous research has demonstrated

that DEPDC1 serves a key role in tumorigenesis by contributing to

cellular functions, such as promoting cell proliferation and cell

cycle progression, while suppressing apoptosis (20–22).

However, few studies have investigated the role of DEPDC1 in the

development and prognosis of gliomas.

In the present study, the relationship between

DEPDC1 expression levels and the clinical characteristics of

gliomas was explored by analyzing online databases and further

examining the functional role of DEPDC1 through Gene ontology (GO)

and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). The present study aimed to

investigate the potential role of DEPDC1 in gliomas, with a focus

on its association with tumor progression and patient prognosis.

Understanding the implications of DEPDC1 expression could

potentially contribute to the development of targeted therapeutic

strategies for glioma management in the future.

Materials and methods

Data source

The present study utilized publicly available

datasets from the China Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA), including

Cohort 1 (accession no. CGGA_325) and Cohort 2 (accession no.

CGGA_693), to analyze the expression of DEPDC1 in gliomas. The raw

Fastq data for these datasets are available under the BIGD

accession numbers PRJCA001746 (Cohort 1) and PRJCA001747 (Cohort

2). Cohort 1 and 2 consist of gene expression data and clinical

profiles of patients with glioma, providing valuable insights into

tumor biology and disease progression. The original studies

detailing these datasets can be obtained from previous CGGA

publications (23,24). Glioma gene expression and clinical

data were downloaded from the CGGA database (https://www.cgga.org.cn/download.jsp), which includes

variables such as the sex, age, WHO grade (2), IDH mutation status, 1p/19q co-deletion

status, MGMT promoter methylation status and survival information.

Additionally, the Glioma Longitudinal Analysis (GLASS) dataset

(http://synapse.org/glass) was used as

the validation cohort. To elucidate the relationship between DEPDC1

expression and glioma prognosis, the present study analyzed its

association with key clinical features using data from the CGGA

database. Specifically, two RNA sequencing datasets were used, CGGA

Cohort 1 and CGGA Cohort 2, comprising 325 and 693 glioma samples,

respectively.

In the CGGA Cohort 1 dataset, patients were divided

into a high expression level group (≥0.56) and a low expression

group (<0.56), using the median DEPDC1 expression as the cut-off

value. Similarly, for CGGA Cohort 2, the median DEPDC1 expression

value of 0.21 was used to stratify patients into high and low

expression groups. These thresholds were applied to assess the

prognostic significance of DEPDC1 expression in glioma

patients.

Relationship between DEPDC1 and

clinical features

The association between the expression of DEPDC1 and

common prognostic features was analyzed. The key features,

including WHO classification (grades 1–4), IDH mutation status

(wild type/mutant), primary vs. recurrent tumor status, 1p/19q

deletion status (coding/non-coding deletion), age, sex, MGMT

promoter methylation and DEPDC1 expression, were compared. Patients

with glioma were divided into two groups based on high or low

DEPDC1 expression levels, and survival curves were generated using

Kaplan-Meier analysis. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed

using overall survival (OS) as the survival metric, with time

measured in months from the initial diagnosis to either the last

follow-up or death.

Gene enrichment analysis

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between high

and low DEPDC1 expression groups was identified using the ‘samr’

package (version 3.0; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/samr/) in R

(log2 FC>2 and P<0.05 were the criteria for screening DEGs).

GSEA (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) was

performed to identify signaling pathways significantly associated

with the DEPDC1 expression levels. GSEA methods evaluate gene

expression patterns across gene sets rather than focusing on

individual genes, which can provide a more comprehensive view of

enrichment pathways.

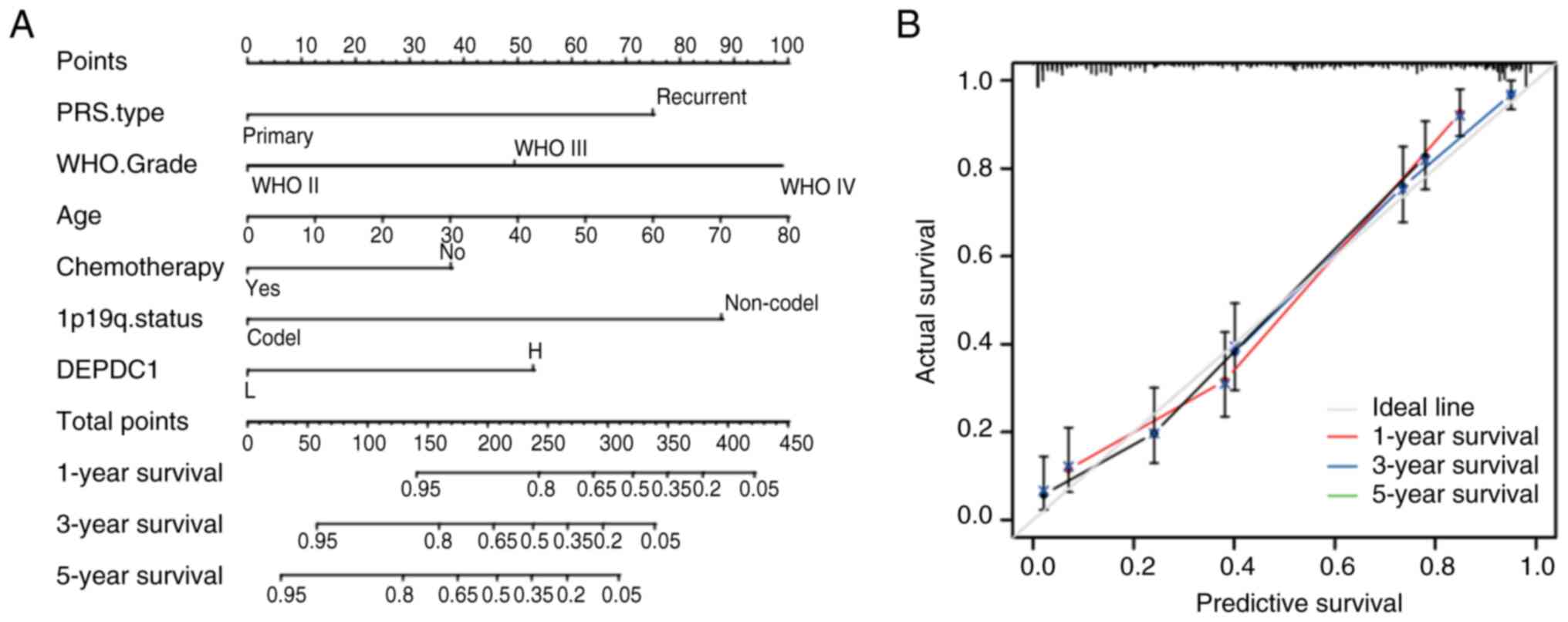

Construction of prediction model

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship

between variables and OS in CGGA and GLASS datasets. Variables with

P<0.05 in the multivariate Cox regression analysis were selected

to construct a prognostic risk model.

Build a nomogram

A nomogram was constructed in the training cohort

using the ‘rms’ package (version 6.7–0; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms) in R.

The upper portion of the nomogram represents the scoring system,

whereas the lower portion represents the prediction system. Based

on the scores for each factor and the total score, this tool

accurately predicts the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of

patients with glioma. Calibration curves and C-index values were

used to evaluate the accuracy of the survival predictions.

Cell lines and agents

The human glioma U87 and LN229 cell lines were

obtained from the Chinese Academy of Medical Science (Beijing,

China). The U87 cell line is a glioblastoma of unknown origin that

has been identified as an ATCC type using short tandem repeat

profiling. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and incubated

in a humidified, CO2-rich environment (5%

CO2) at 37°C. The β-actin antibody (cat. no.

20536-1-AP), MMP-2 (cat. no. 10373-2-AP), MMP-9 (cat. no.

10375-2-AP) and secondary antibody (cat. nos. SA00001-1 and

SA00001-2) were obtained from Proteintech Group, Inc., while the

DEPDC1 antibody (cat. no. ab197246) was purchased from Abcam.

Cell transfection

The lentiviral transduction in the present study was

performed using a 2nd generation lentiviral system. The 293T cell

line was used as the packaging cell line, obtained from American

Type Culture Collection. For transfection, 10 µg of lentiviral

plasmid, 5 µg of packaging plasmid (psPAX2) and 2.5 µg of envelope

plasmid (pMD2.G) were used in a 4:2:1 ratio. Transfection was

carried out at 37°C for 6 h, after which the medium was replaced

with fresh culture medium. Lentiviral particles were collected 48 h

post-transfection by harvesting the supernatant and filtering it

through a 0.45-µm filter. The multiplicity of infection used for

infecting target cells was 10. Transduction was carried out by

incubating the target cells with viral particles at 37°C for 24 h,

followed by a medium change. After 72 h, cells were subjected to

subsequent experiments.

To establish stable cell lines, puromycin selection

was performed using a concentration of 2 µg/ml for 7 days. Once the

selection was complete, cells were maintained in 1 µg/ml puromycin

for continued culture. U87 and LN229 cells were seeded at a density

of 2×105 cells per well in 6-well plates and the DEPDC1

gene was silenced using pLKO.1 lentiviral transduction containing

DEPDC1-targeting shRNA in both cell lines. The DEPDC1-shRNA and

negative control shRNA were designed by Suzhou GenePharma Co.,

Ltd., using the following sequences: shDEPDC1 sense,

5′-GAACTATCAAGAGTAGTTCGT-3′ and antisense,

5′-UUGUUCUGAAUACAUCUCGTT-3′; and shCtrl sense,

5′-GUACCGCACGUCAUUCGUAUC-3′ and antisense,

5′-UACGAAUGACGUGCGGUACGU-3′.

Reverse transcription quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the transfected cells

using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse

transcription was performed using the GoScript Reverse

Transcription System (Promega Corporation) and RT-qPCR was

performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio, Inc.), following

the manufacturers' instructions. Relative mRNA levels of DEPDC1

were normalized against GAPDH using the 2−ΔΔCq formula

(25). The primer sequences were as

follows: DEPDC1 forward, 5′-TTCTAGATCTCCCTGAACCTCT-3′; and reverse,

5′-TGATGTAGCCACAAACAACCAAA-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3′; and reverse,

5′-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3′. The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 30

sec and 72°C for 30 sec. To ensure consistency and reliability,

each experiment included three technical replicates.

Western blotting

After transfection, cells were harvested for western

blot analysis. Total cellular protein was extracted using RIPA

buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), quantified using a

BCA assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Subsequently, 20

µg of each protein sample was loaded per lane and separated on a

10% SDS-PAGE gel. Following electrophoresis, proteins were

transferred onto PVDF membranes (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for

further analysis. Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum

albumin for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the primary

antibodies anti-DEPDC1 (cat. no. ab197246; 1:1,000; Abcam),

anti-MMP-2 (cat. no. 10373-2-AP; 1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

anti-MMP-9 (cat. no. 10375-2-AP; 1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

and anti-β-actin (cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; 1:2,000; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated

with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. SA00001-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG

(cat. no. SA00001-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.) antibodies at a

dilution of 1:5,000 at room temperature for 1.5 h, followed by

three 15-min washes with TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1%

Tween-20; cat. no. P9416; Sigma-Aldrich). Protein expression levels

were detected using Image Lab software (version 6.1; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) and visualized using the ECL Prime Western

Blotting Detection Reagent (cat. no. GERPN2232; MilliporeSigma).

The optical density of each strip was analyzed using ImageJ

software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of Health). All the

experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

experiment

The CCK-8 assay was performed to evaluate the

proliferation of U87 and LN229 cells following transfection.

Briefly, 1×103 normal and transfected cells were seeded

into 96-well plates and cultured for 24, 48 or 72 h. Cell

proliferation was assessed using a CCK-8 kit (GLPBIO Technology

LLC) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and the absorbance

was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm after incubation with the

CCK-8 reagent for 2 h at 37°C.

Wound healing assay

A wound healing assay was performed to evaluate the

migration capacity of U87 and LN229 cells following transfection.

Briefly, 1×106 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and

cultured for 24 h. A cross-shaped scratch was made on the monolayer

of cells using a sterile 10-µl pipette tip. The scratched area was

washed three times with PBS to remove the cell debris. The cells

were then cultured in a serum-free medium for an additional 24 h

and images of the wound area were captured. The wound area,

distance between wound edges and cell confluence were measured

using ImageJ software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of

Health). Scratch closed rate=(initial scratch width-scratch width

after 24 h)/initial scratch width ×100%. The assay was repeated

three times, and images were captured using an Olympus IX73

inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Transwell experiment

The invasive potential of U87 and LN229 cells after

transfection was assessed using a Transwell assay. Prior to

seeding, Matrigel was thawed on ice overnight at 4°C, diluted to a

final concentration of 2 mg/ml with cold serum-free medium and

50–100 µl was added to the upper chamber of each Transwell insert.

The plate was incubated at 37°C for 30–60 minto allow the Matrigel

to polymerize. Serum-free cells (1×105 cells/well) were

seeded in the upper chambers, whereas the lower chambers contained

10% FBS, which served as a chemoattractant. The cells were cultured

at 37°C for 12 h and subsequently washed three times with PBS.

Cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min and subsequently

stained with crystal violet at room temperature for 30 min.

Subsequently, the stained cells were imaged using an Olympus IX73

inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation) and counted using ImageJ

software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of Health). This assay

was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the R

software (version 3.6.2; Institute for Statistical Computing,

Vienna, Austria), GraphPad Prism 9.0 (Dotmatics) or SPSS 18.0

(SPSS, Inc.). Kaplan-Meier analyses were performed using log-rank

tests to assess survival differences between the groups, and the

analyses were conducted using the ‘survival’ and ‘survminer’ R

software packages. c2 tests were used to evaluate the

differences in clinical and molecular characteristics between the

different DEPDC1 expression groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analyses were performed to identify the prognostic

factors. Unpaired t-tests were performed to test the significance

of differences between the two groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Expression of DEPDC1 and its

association with clinical characteristics and prognosis of

gliomas

With advancing research on gliomas, several

molecular markers have been identified as pivotal for understanding

the pathogenesis and diagnosis of gliomas, including IDH and 1p19q

status (26,27). To elucidate the relationship between

DEPDC1 expression and glioma prognosis, the association between

DEPDC1 expression and key clinical features of glioma was examined

in the present study using data from the CGGA Cohort 1 and 2

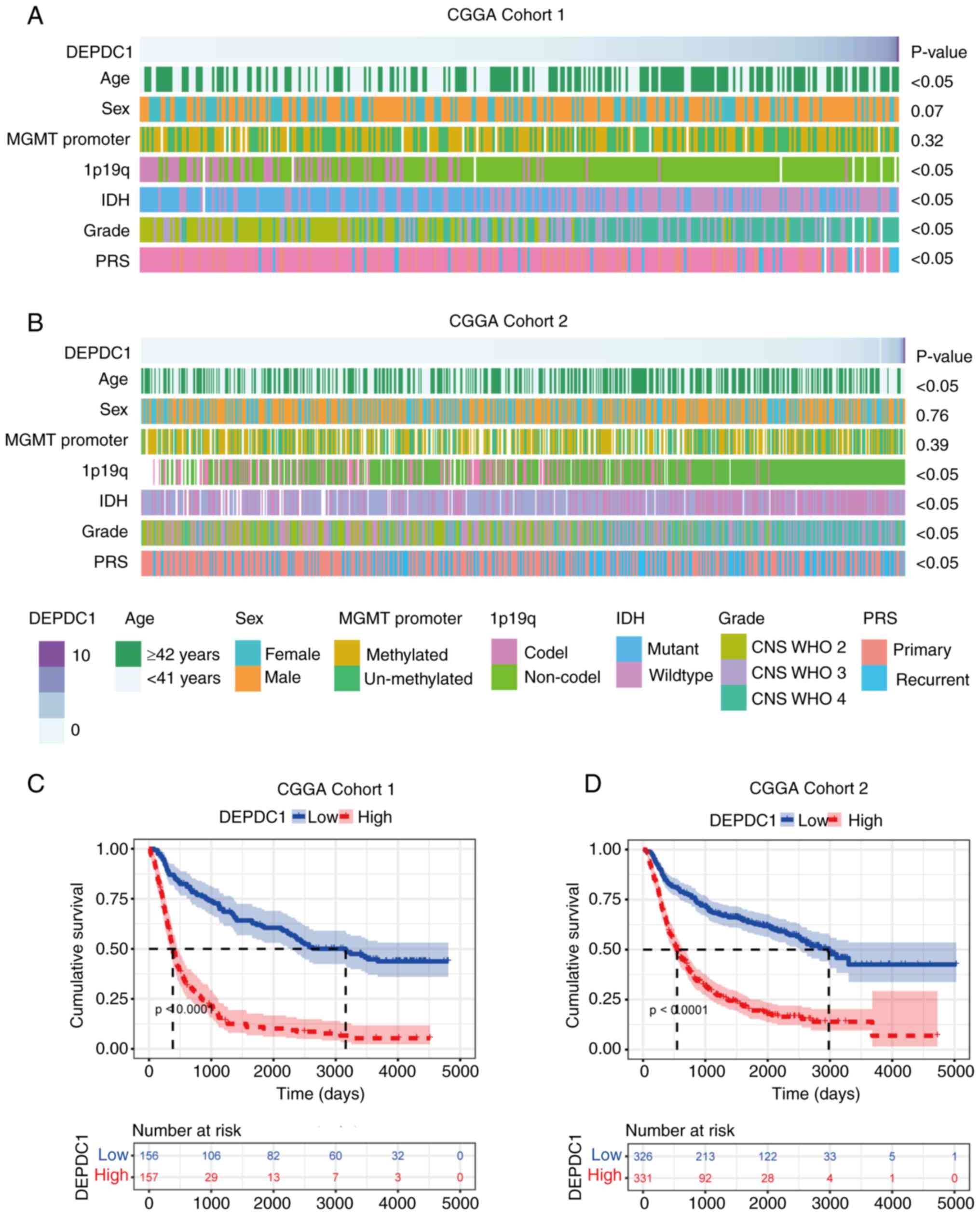

datasets. As shown in Fig. 1A and

B, the expression of DEPDC1 was significantly elevated in older

patients (≥42 years), patients with a high histological grade (CNS

WHO grades 3 and 4), those with IDH wild-type gliomas, patients

with 1p19q non-codel gliomas and those with recurrent tumors.

Although similar trends were observed in the GLASS dataset

(Fig. S1A), the association

between DEPDC1 and tumor recurrence was not statistically

significant. These findings suggest that expression of DEPDC1 is

enriched in patients with glioma with high malignancy.

To further investigate the prognostic implications

of DEPDC1 expression differences, a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

was performed. As illustrated in Fig.

1C and D, patients from both the CGGA Cohort 1 and 2 datasets

were stratified into high and low DEPDC1 expression groups. The

analysis revealed that patients with low DEPDC1 expression had a

significantly improved prognosis compared with those patients with

high DEPDC1 expression (P<0.0001). These results were validated

using a GLASS cohort (Fig. S1B)

(P<0.0001), with outcomes consistent with those observed in CGGA

cohort 325 (Cohort 1) and CGGA cohort 693 (Cohort 2). Collectively,

these findings indicate that high expression of DEPDC1 is

associated with shorter survival times, suggesting it has potential

as a prognostic marker in gliomas.

GO analysis of DEGs and GSEA

enrichment analysis

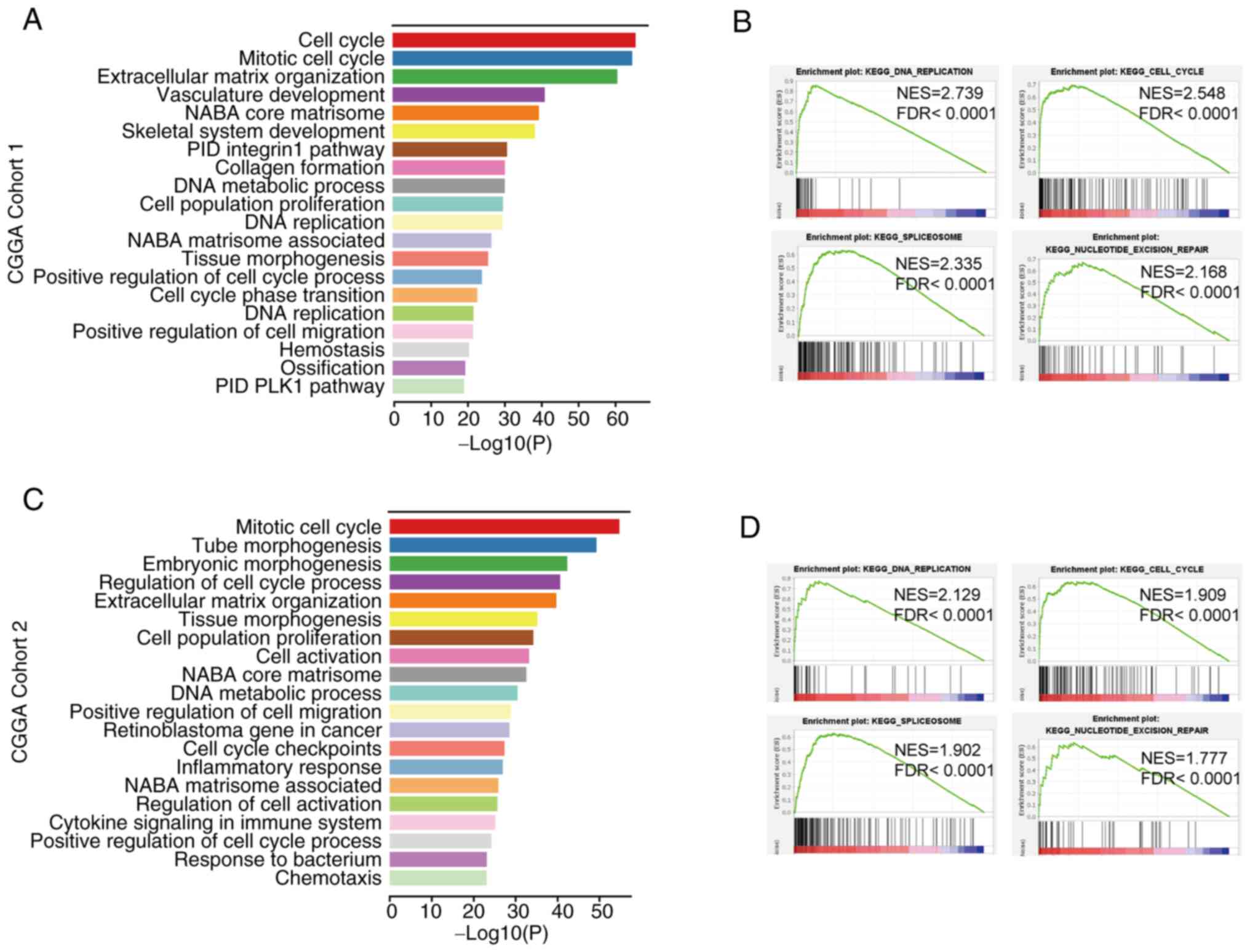

To further investigate the potential mechanisms by

which DEPDC1 contributes to the deterioration of prognosis in

patients with glioma, the pathways that DEPDC1 modulates were

examined. Patients were divided into two groups based on the median

expression of DEPDC1, with the low expression group serving as the

control. In CGGA Cohort 1, 957 genes were upregulated (log2 FC

>2; P<0.05). GO analysis was performed on the DEGs. GO

analysis revealed the top enriched pathways associated with DEPDC1

expression, with the top five pathways including ‘cell cycle’,

‘mitotic cell cycle’, ‘extracellular matrix organization’,

‘vasculature development’ and ‘NABA core matrisome’ (Fig. 2A). In CGGA Cohort 2, 324 genes were

upregulated in the high expression group (Log2 FC >2;

P<0.05). GO analysis identified DEPDC1-related pathways among

the significantly enriched terms, with the top five being ‘mitotic

cell cycle’, ‘tube morphogenesis’, ‘embryonic morphogenesis’,

‘regulation of cell cycle process’ and ‘extracellular matrix

organization’ (Fig. 2C). These

findings were consistent with the data shown in Fig. 2A. While ‘inflammatory response’ and

‘cytokine signaling in the immune system’ were not the

highest-ranked pathways by statistical significance, they were

highlighted due to their potential involvement in the glioma

microenvironment and immune regulation. Therefore, both datasets

predominantly showed enrichment in the cell cycle, vascular

development and immune-related pathways. GSEA was performed to

confirm these findings. As shown in Fig. 2B and D, the main enriched pathways

identified using GSEA included ‘cell cycle’, ‘DNA replication’,

‘spliceosome’ and ‘nucleotide excision repair’. These results

confirmed that DEPDC1 is closely associated with the glioma cell

cycle, immune response and vascular development. Similar results

were obtained for the GLASS dataset (Fig. S2).

Expression of DEPDC1 is closely

associated with the cell cycle

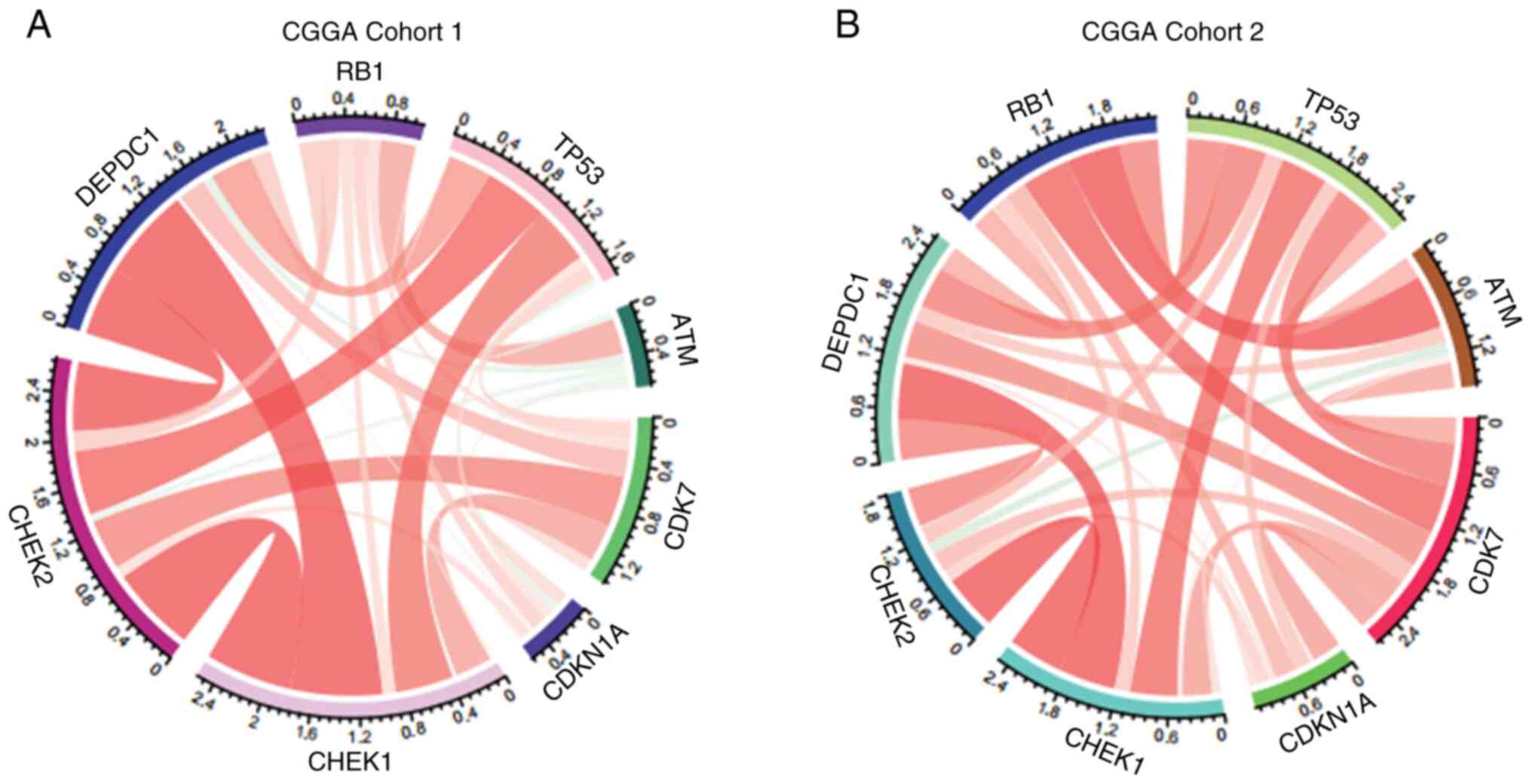

To further explore the mechanism through which

DEPDC1 regulates glioma cell proliferation, its relationship with

established cell cycle checkpoints was examined. The analysis

revealed that checkpoint kinase 1 (CHEK1), cyclin-dependent kinase

7 (CDK7) and tumor protein 53 (TP53) were positively associated

with the expression of DEPDC1 in both CGGA Cohorts 1 and 2

(Fig. 3A and B). A similar trend

was observed in the GLASS cohort (Fig.

S3B), although the correlation between DEPDC1 and CDK7 appears

less pronounced compared with other cell cycle-related genes. These

results indicate that the expression of DEPDC1 may serve a role in

the regulation of glioma cell cycle progression.

DEPDC1 is an independent prognostic

factor in patients with glioma

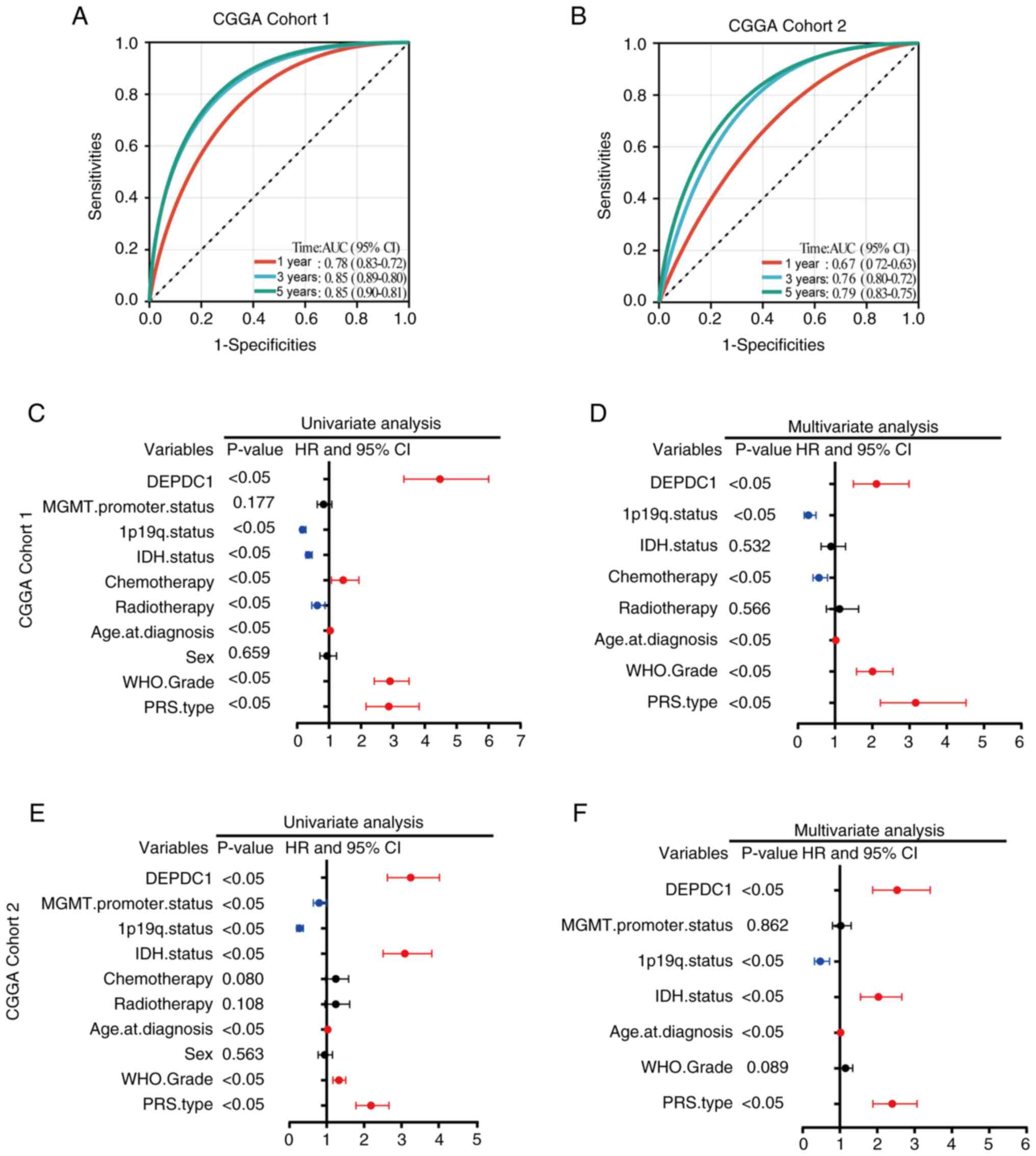

To further evaluate the role of DEPDC1 in the

prognosis of patients with glioma, receiver operating

characteristic analysis was used to assess the ability of DEPDC1

expression to predict patient outcomes. As shown in Fig. 4A, in CGGA Cohort 1, the area under

the curve (AUC) was 0.78 at 1 year, 0.85 at 3 years and 0.85 at 5

years. As shown in Fig. 4B, in CGGA

Cohort 2, the AUC reached 0.67 at 1 year, 0.76 at 3 years and 0.79

at 5 years, respectively. Similarly, in the GLASS dataset (Fig. S3A), the AUC values were 0.61 at 1

year, 0.75 at 3 years, and 0.85 at 5 years. In CGGA Cohort 1

(CGGA_325), the AUC values were 0.78 at 1 year, 0.85 at 3 years and

0.85 at 5 years (Fig. 4A), while in

the CGGA Cohort 2, the AUC values were 0.67 at 1 year, 0.76 at 3

years and 0.79 at 5 years (Fig.

4B). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of

CGGA Cohorts 1 and 2 indicated that DEPDC1 is an independent

prognostic factor for patients with glioma (Fig. 4C-F). Similar results were observed

for the GLASS dataset (Fig. S3C and

D). These results suggested that expression of DEPDC1 is an

independent prognostic factor for OS.

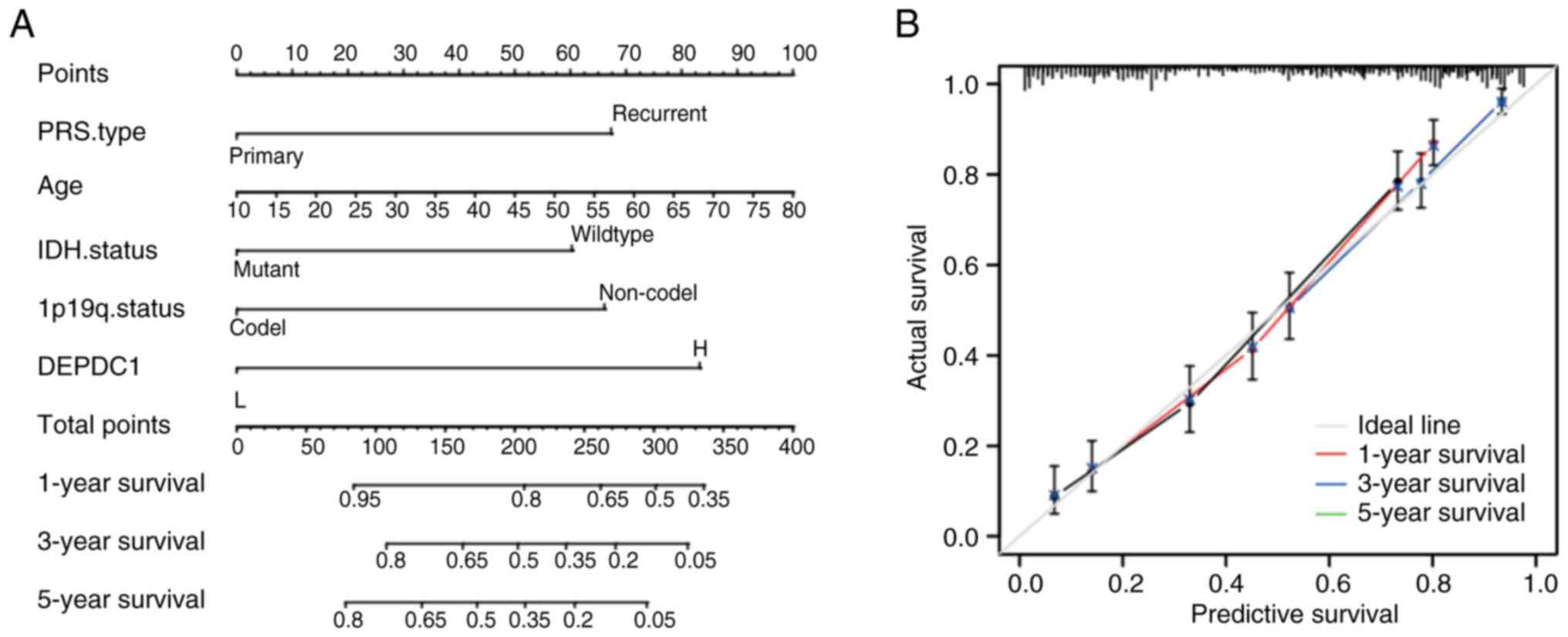

Individualized prediction model shows

high accuracy

Independent prognostic indicators of OS were

selected and integrated into multivariate regression analysis to

construct a prediction model. In the CGGA Cohort 1 dataset,

patients were divided into a high expression group (≥0.56) and low

expression group (<0.56), with the median DEPDC1 expression as

the cut-off value. High and low expression of DEPDC1 contributed to

risk scores from 0 to 100 (Fig.

5A). In CGGA Cohort 1, the C-index of the nomogram was 0.810.

The calibration plot demonstrated a good agreement between the

predicted and observed 1-, 3- and 5-year OS probabilities (Fig. 5B). Similar results were validated in

the CGGA Cohort 2 (Fig. 6) and

GLASS datasets (Fig. S4), with

C-indices of 0.771 and 0.763, respectively, indicating the high

accuracy of the DEPDC1 score.

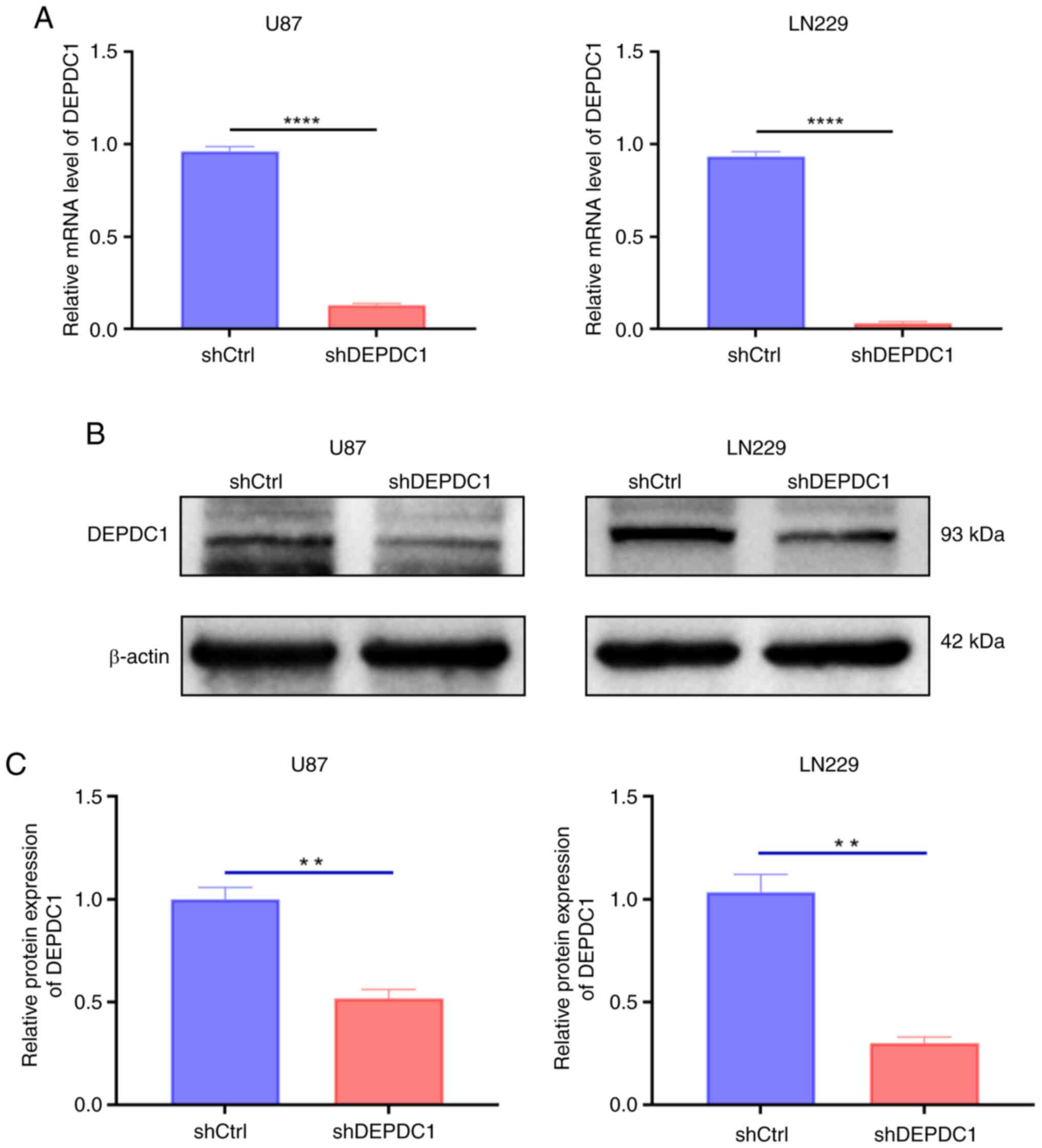

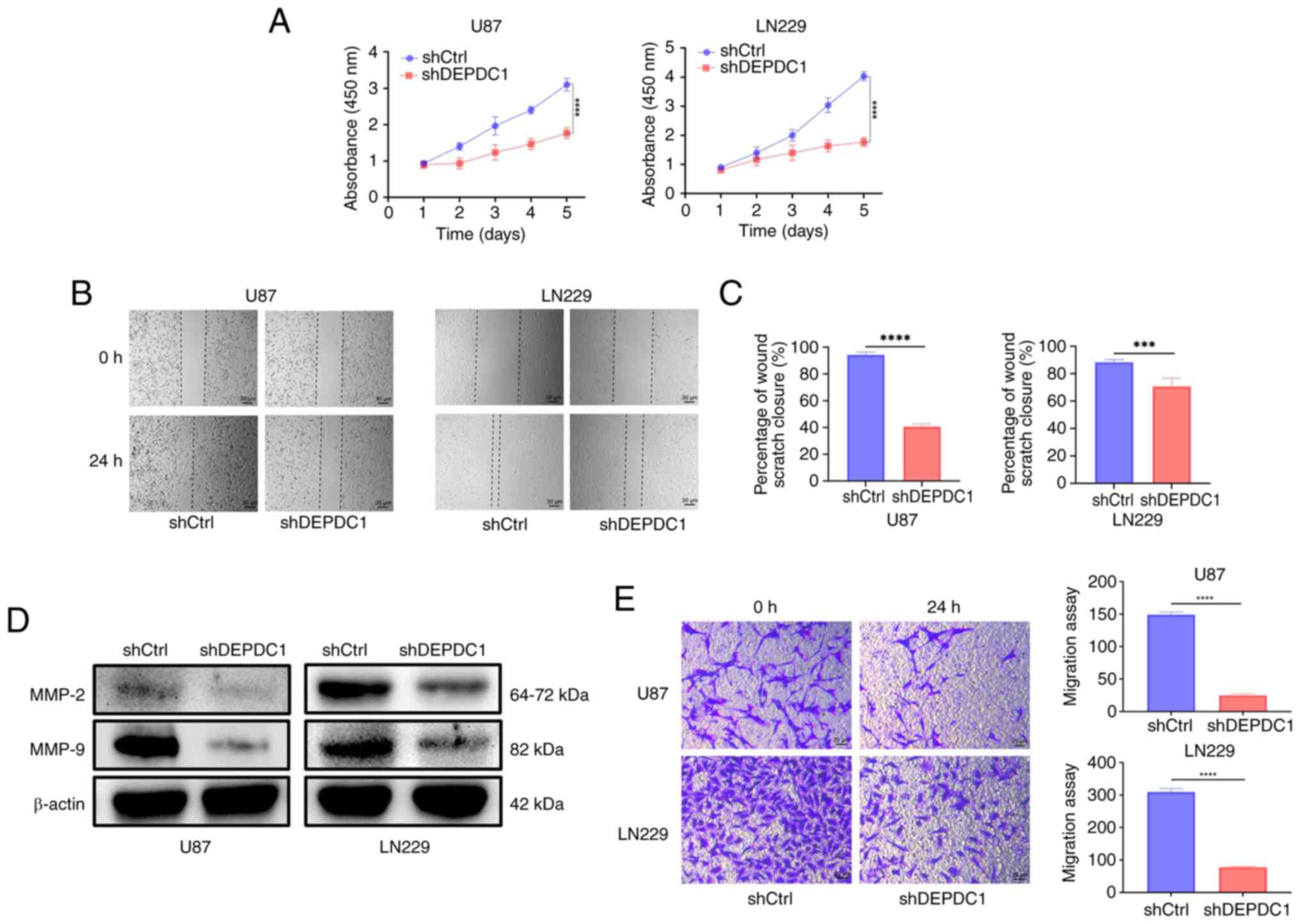

Expression of DEPDC1 is associated

with the proliferation and invasion of gliomas

To investigate the expression levels of DEPDC1 in

U87 and LN229 cells, shRNA was used to interfere with DEPDC1

expression in both cell lines. As shown in Fig. 7A, RT-qPCR analysis indicated that

DEPDC1 mRNA levels decreased significantly after silencing with

shDEPDC1 compared with the control shRNA. Correspondingly, western

blot analysis demonstrated that the protein expression levels also

showed qualitative and semi-quantitative reductions, as shown in

Fig. 7B and C. To further examine

the impact of DEPDC1 expression on glioma cell proliferation and

invasion, CCK-8, wound healing and Transwell invasion assays were

performed. As shown in Fig. 8A, the

proliferation rate of glioma cells was significantly reduced over

the first 5 days following DEPDC1 silencing compared with the

control shRNA. In addition, Fig. 8B

shows wound healing assay results for U87 and LN229 cells,

comparing cell migration over a 24 h period. At 0 h, the wound

areas were similar in all groups. After 24 h, the shCtrl cells

migrated more compared with the shDEPDC1 cells, indicating that

DEPDC1 knockdown reduced migration. Furthermore, Fig. 8C shows the invasion assay results

for U87 and LN229 cells. At 0 h, the number of invading cells was

similar between groups. After 24 h, fewer cells had invaded in the

shDEPDC1 group compared with the shCtrl group, indicating that

DEPDC1 knockdown reduces invasion. Additionally, migration-related

proteins MMP-2 and MMP-9 were markedly decreased after DEPDC1

silencing, as shown in Fig 8D.

Fig. 8E demonstrates that the

invasive ability of glioma cells in both cell lines was

significantly impaired by DEPDC1 silencing compared with the

control shRNA, as observed in the Transwell assay.

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated that DEPDC1

upregulation is closely associated with a poor prognosis in several

malignant tumors, including hepatocellular carcinoma (28–31),

lung adenocarcinoma (15,32), colorectal cancer (33,34),

breast cancer (35) and

osteosarcoma (36). A notable study

further demonstrated that DEPDC1 is markedly upregulated in 29 out

of 33 human cancer types and is associated with OS,

disease-specific survival and progression-free survival in multiple

tumor types (37). In the present

study, expression levels of DEPDC1 were assessed in gliomas with

several typical prognostic characteristics by performing

association analysis based on data from patients with glioma from

the CGGA and GLASS databases. The results demonstrated that DEPDC1

is highly expressed in more aggressive gliomas, particularly in

patients of older age (≥42 years), those with high histological

grades (CNS WHO 3,4), those with IDH wild-type gliomas, patients

with 1p/19q codeletion and cases with tumor recurrence.

Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to examine the relationship

between the expression of DEPDC1 and patient prognosis, further

confirming that high DEPDC1 expression significantly affects

survival time. Furthermore, DEPDC1 expression was observed in human

glioma U87 and LN229 cell lines. Additionally, DEPDC1 knockdown

inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of glioma

cells. This suggested that DEPDC1 serves a role in promoting glioma

progression. The reduced cell motility and invasion observed after

DEPDC1 knockdown were consistent with previous studies on

DEPDC1-related tumor genes (17,38,39).

These findings indicate that DEPDC1 may contribute to glioma

malignancy and could be a potential target for further

investigation.

To further investigate the potential mechanisms by

which DEPDC1 contributes to glioma progression, its relationship

with cell cycle regulation, immune response and vascular

development was examined through GO and GSEA enrichment analyses of

DEGs from two CGGA database cohorts, with results corroborated in

the GLASS dataset. The findings suggest that DEPDC1 influences

glioma cell proliferation and apoptosis through the expression of

several specific RNAs or proteins, such as cyclin dependent kinase

1, CHEK1 and RB transcriptional corepressor 1, were affected by

DEPDC1 knockdown. These findings suggest that DEPDC1 may regulate

glioma progression through pathways involving cell cycle control

and DNA damage response (40).

Additionally, DEPDC1 may induce generation of specific T

lymphocytes, potentially affecting immune system function (41) and promoting the overexpression of

angiogenic factors, leading to increased glioma proliferation and

blood vessel density (42).

In view of the relationship between DEPDC1

expression and the cell cycle, its association with several

recognized cell cycle checkpoints was investigated. The results

demonstrate expression of DEPDC1 was positively associated with

CHEK1, CDK7 and TP53 expression. CHEK1 is a key signal transduction

factor in the genome integrity checkpoint, and its mutations have

been implicated in various cancer types, including colon, stomach

and endometrial carcinomas (43).

Similarly, abnormal CDK7 expression or function (44) and TP53 mutations (45) are associated with the occurrence and

progression of multiple cancer types, including breast, colorectal,

ovarian, head and neck and lung cancers. Thus, DEPDC1 may influence

glioma progression by modulating the expression of these genes,

contributing to cell cycle regulation and affecting tumor

proliferation, malignancy and potential prognosis. As demonstrated

in previous studies, DEPDC1 serves an important role in regulating

the cell cycle and tumor progression across different cancer types

via various signaling pathways. For instance, Huang et al

(19) showed that in prostate

cancer, DEPDC1 enhances E2F1 transcriptional activity, thereby

upregulating cyclin D1 and CDK2, leading to a more frequent

G1-S phase cell cycle transition. Similarly, Wang et

al (16) reported that DEPDC1

promotes SUZ12 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit expression to

drive proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

of colorectal cancer. These findings suggest a potential mechanism

through which DEPDC1 regulates cell cycle progression. However,

further investigations are needed to elucidate the specific

mechanism of action of DEPDC1 in glioma cell cycle regulation.

In the present study, univariate and multivariate

Cox regression analyses were performed and demonstrated that DEPDC1

serves as an independent prognostic factor in patients with glioma.

To evaluate the accuracy of DEPDC1 as a prognostic marker, a

prediction model was constructed based on 1-, 3- and 5-year

survival rates using a nomogram calibrated against the CGGA

database observations. These results indicate that high DEPDC1

expression adversely affects patient prognosis. If this prediction

model is highly accurate, it may support clinical decision making,

potentially improving patient outcomes.

The present study has certain limitations. The

results demonstrated that DEPDC1 is closely associated with key

genes in multiple cell cycle signaling pathways. However, the

molecular interaction mechanisms have not been further elucidated

in animal experiments and patient-derived glioma samples.

Additionally, as patients with high-grade glioma generally have a

worse prognosis, the functional role of DEPDC1 was only evaluated

in two high-grade glioma cell lines. Therefore, the functions of

DEPDC1 observed in the present study may not apply to low-grade

gliomas. These limitations should be addressed in animal models and

glioma cell lines of various grades.

In summary, the expression of DEPDC1 is closely

associated with glioma cell cycle regulation and serves as an

independent prognostic indicator, with higher expression levels

linked to worse outcomes. DEPDC1 knockdown reduces glioma cell

proliferation and migration, suggesting it has potential as a

target for individualized tumor treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HL and YL contributed to conceptualization, formal

analysis, investigation, data curation and writing of the original

draft. HZ contributed to methodology, formal analysis and reviewing

of the original draft. HZ, HL and YL confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. XW contributed to conceptualization, reviewing

the draft, supervision, project administration and funding

acquisition. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Waite K, Kruchko C

and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain

and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United

States in 2014–2018. Neuro Oncol. 23:iii1–iii105. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nicholson JG and Fine HA: Diffuse glioma

heterogeneity and its therapeutic implications. Cancer Discov.

11:575–590. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zeng J, Li X, Sander M, Zhang H, Yan G and

Lin Y: Oncolytic Viro-Immunotherapy: An emerging option in the

treatment of gliomas. Front Immunol. 12:7218302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, Read W,

Steinberg D, Lhermitte B, Toms S, Idbaih A, Ahluwalia MS, Fink K,

et al: Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance

temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in

patients with glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

318:2306–2316. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Brown CE, Hibbard JC, Alizadeh D,

Blanchard MS, Natri HM, Wang D, Ostberg JR, Aguilar B, Wagner JR,

Paul JA, et al: Locoregional delivery of IL-13Rα2-targeting CAR-T

cells in recurrent high-grade glioma: A phase 1 trial. Nat Med.

30:1001–1012. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Waite K, Kruchko C

and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain

and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United

States in 2014–2018. Neuro Oncol. 23:iii1–iii105. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rees JH: Diagnosis and treatment in

neuro-oncology: An oncological perspective. Br J Radiol. 84(Spec No

2): S82–S89. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huse JT and Holland EC: Targeting brain

cancer: Advances in the molecular pathology of malignant glioma and

medulloblastoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 10:319–331. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller

M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn

U, et al: Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide

for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 352:987–996. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Weller M, Stupp R, Reifenberger G, Brandes

AA, van den Bent MJ, Wick W and Hegi ME: MGMT promoter methylation

in malignant gliomas: Ready for personalized medicine? Nat Rev

Neurol. 6:39–51. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ellingson BM, Wen PY and Cloughesy TF:

Modified criteria for radiographic response assessment in

glioblastoma clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 14:307–320. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kanehira M, Harada Y, Takata R, Shuin T,

Miki T, Fujioka T, Nakamura Y and Katagiri T: Involvement of

upregulation of DEPDC1 (DEP domain containing 1) in bladder

carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 26:6448–6455. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li Y, Tian Y, Zhong W, Wang N, Wang Y,

Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Li J, Ma F, Zhao Z and Peng Y: Artemisia argyi

essential oil inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis via

suppression of DEPDC1 dependent Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6647912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang W, Li A, Han X, Wang Q, Guo J, Wu Y,

Wang C and Huang G: DEPDC1 up-regulates RAS expression to inhibit

autophagy in lung adenocarcinoma cells. J Cell Mol Med.

24:13303–13313. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang Q, Jiang S, Liu J, Ma G, Zheng J and

Zhang Y: DEP domain containing 1 promotes proliferation, invasion,

and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer by

enhancing expression of suppressor of zest 12. Cancer Biother

Radiopharm. 36:36–44. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang L, Du Y, Xu S, Jiang Y, Yuan C, Zhou

L, Ma X, Bai Y, Lu J and Ma J: DEPDC1, negatively regulated by

miR-26b, facilitates cell proliferation via the up-regulation of

FOXM1 expression in TNBC. Cancer Lett. 442:242–251. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shen L, Li H, Liu R, Zhou C, Bretches M,

Gong X, Lu L, Zhang Y, Zhao K, Ning B, et al: DEPDC1 as a crucial

factor in the progression of human osteosarcoma. Cancer Med.

12:5798–5808. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang L, Chen K, Cai ZP, Chen FC, Shen HY,

Zhao WH, Yang SJ, Chen XB, Tang GX and Lin X: DEPDC1 promotes cell

proliferation and tumor growth via activation of E2F signaling in

prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 490:707–712. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang Y, Jiang Y, Jiang M, Zhang J, Yang B,

She Y, Wang W, Deng Y and Ye Y: Protocadherin 10 inhibits cell

proliferation and induces apoptosis via regulation of DEP domain

containing 1 in endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol.

100:344–352. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mi Y, Zhang C, Bu Y, Zhang Y, He L, Li H,

Zhu H, Li Y, Lei Y and Zhu J: DEPDC1 is a novel cell cycle related

gene that regulates mitotic progression. BMB Rep. 48:413–418. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sendoel A, Maida S, Zheng X, Teo Y,

Stergiou L, Rossi CA, Subasic D, Pinto SM, Kinchen JM, Shi M, et

al: DEPDC1/LET-99 participates in an evolutionarily conserved

pathway for anti-tubulin drug-induced apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol.

16:812–820. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhao Z, Zhang KN, Wang Q, Li G, Zeng F,

Zhang Y, Wu F, Chai R, Wang Z, Zhang C, et al: Chinese glioma

genome atlas (CGGA): A comprehensive resource with functional

genomic data from chinese glioma patients. Genomics Proteomics

Bioinformatics. 19:1–12. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang K, Liu X, Li G, Chang X, Li S, Chen

J, Zhao Z, Wang J, Jiang T and Chai R: Clinical management and

survival outcomes of patients with different molecular subtypes of

diffuse gliomas in China (2011–2017): A multicenter retrospective

study from CGGA. Cancer Biol Med. 19:1460–1476. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chakrabarty S, LaMontagne P, Shimony J,

Marcus DS and Sotiras A: MRI-based classification of IDH mutation

and 1p/19q codeletion status of gliomas using a 2.5D hybrid

multi-task convolutional neural network. Neurooncol Adv.

5:vdad0232023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wesseling P, van den Bent M and Perry A:

Oligodendroglioma: Pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers.

Acta Neuropathol. 129:809–827. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Amisaki M, Yagyu T, Uchinaka EI, Morimoto

M, Hanaki T, Watanabe J, Tokuyasu N, Sakamoto T, Honjo S and

Fujiwara Y: Prognostic value of DEPDC1 expression in tumor and

non-tumor tissue of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Anticancer Res. 39:4423–4430. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yuan SG, Liao WJ, Yang JJ, Huang GJ and

Huang ZQ: DEP domain containing 1 is a novel diagnostic marker and

prognostic predictor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 15:10917–10922. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bin X, Luo Z, Wang J and Zhou S:

Identification of a five immune term signature for prognosis and

therapy options (Immunotherapy versus Targeted Therapy) for

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Comput Math Methods Med.

2023:89589622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang L, Li Y, Dai Y, Wang D, Wang X, Cao

Y, Liu W and Tao Z: Glycolysis-related gene expression profiling

serves as a novel prognosis risk predictor for human hepatocellular

carcinoma. Sci Rep. 11:188752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Shao F, Ling L, Li C, Huang X, Ye Y, Zhang

M, Huang K, Pan J, Chen J and Wang Y: Establishing a

metastasis-related diagnosis and prognosis model for lung

adenocarcinoma through CRISPR library and TCGA database. J Cancer

Res Clin Oncol. 149:885–899. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhu Y, Sun L, Yu J, Xiang Y, Shen M, Wasan

HS, Ruan S and Qiu S: Identification of biomarkers in colon cancer

based on bioinformatic analysis. Transl Cancer Res. 9:4879–4895.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shen X and Han J: Overexpression of gene

DEP domain containing 1 and its clinical prognostic significance in

colorectal cancer. J Clin Lab Anal. 34:e236342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kim J: In silico analysis of

differentially expressed genesets in metastatic breast cancer

identifies potential prognostic biomarkers. World J Surg Oncol.

19:1882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yang M, Zhang H, Gao S and Huang W: DEPDC1

and KIF4A synergistically inhibit the malignant biological behavior

of osteosarcoma cells through Hippo signaling pathway. J Orthop

Surg Res. 18:1452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jia B, Liu J, Hu X, Xia L and Han Y:

Pan-cancer analysis of DEPDC1 as a candidate prognostic biomarker

and associated with immune infiltration. Ann Transl Med.

10:13552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Harada Y, Kanehira M, Fujisawa Y, Takata

R, Shuin T, Miki T, Fujioka T, Nakamura Y and Katagiri T:

Cell-permeable peptide DEPDC1-ZNF224 interferes with

transcriptional repression and oncogenicity in bladder cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 70:5829–5839. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhou C, Wang P, Tu M, Huang Y, Xiong F and

Wu Y: DEPDC1 promotes cell proliferation and suppresses sensitivity

to chemotherapy in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Rep.

39:BSR201909462019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Feng X, Zhang C, Zhu L, Zhang L, Li H, He

L, Mi Y, Wang Y, Zhu J and Bu Y: DEPDC1 is required for cell cycle

progression and motility in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget.

8:63605–63619. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Obara W, Ohsawa R, Kanehira M, Takata R,

Tsunoda T, Yoshida K, Takeda K, Katagiri T, Nakamura Y and Fujioka

T: Cancer peptide vaccine therapy developed from oncoantigens

identified through genome-wide expression profile analysis for

bladder cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 42:591–600. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Guo W, Li H, Liu H, Ma X, Yang S and Wang

Z: DEPDC1 drives hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation,

invasion and angiogenesis by regulating the CCL20/CCR6 signaling

pathway. Oncol Rep. 42:1075–1089. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Alorjani M, Aburub M, Al-Trad B, Hamad MA,

AbuAlarja M, Bashir SA, Al-Batayneh K and Zoubi MA: The prevalence

of CHEK1 and CHEK2 mutations in prostate cancer: A retrospective

cohort Study. Med Arch. 77:8–12. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chen Y, Zhang S, Li Z, Yin B, Liu Y and

Zhang L: Discovery of a dual-target inhibitor of CDK7 and HDAC1

that induces apoptosis and inhibits migration in colorectal cancer.

ChemMedChem. 18:e2023002812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Landsburg DJ, Morrissette JJ, Nasta SD,

Barta SK, Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA and Bagg A: TP53

mutations predict for poor outcomes in patients with newly

diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas in the current era. Blood

Adv. 7:7243–7253. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|