Introduction

Nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) is a rare epithelial

carcinoma with an extremely uneven geographical distribution. As

represented by GLOBOCAN data for 2020, NPC contributes to only 0.7%

of the total number of new cancer cases worldwide, and 70% of these

cases are diagnosed in Eastern and Southeastern Asia (1). According to the 4th edition of the

World Health Organization classification, these carcinomas are

divided into three types: non-keratinizing (subdivided into

differentiated and undifferentiated), keratinizing and basaloid

squamous cell types (2).

Non-keratinizing NPC (NK-NPC) has distinct features such as ethnic

disparities, radio- and chemosensitivity, metastatic potential and

well-proven role of Epstein Barr virus in its pathogenesis

(3). Due to its sensitivity to

anti-neoplastic treatment, a large proportion of patients, even in

advanced stages of disease, could be cured or achieve long-term

remission (3).

Late presentation of NK-NPC requires multimodality

treatment. Radiotherapy (RT) is a mainstay of the curative-intent

approach, with high doses (70 Gy) needed for the eradication of the

gross tumor and doses of 50–60 Gy required for regions of

microscopic infiltration risk (4).

Chemotherapy, in different schemes of application (induction,

concomitant and adjuvant) is added. Cisplatin-based concomitant

chemotherapy has become a treatment standard when considering data

from randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses, which has

indicated that combined treatment improves overall survival, local

recurrence-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival rates

(5–7).

This intensive combined therapeutic approach

inevitably leads to numerous toxicities, both acute and late. In

contrast to acute toxicities, late sequelae are in general

unrecognized, underestimated and often lacking adequate therapy.

Nevertheless, their paramount importance comes from a tendency to

progress over time, affecting patients' quality of life (QoL),

increasing morbidity and even causing mortality. Published

literature reporting late morbidity in NK-NPC survivors is scarce,

often inconsistent and, following uneven geographical distribution,

predominantly driven from the Asian population of patients with

endemic NK-NPC (8–11). Therefore, the present study aimed to

analyze the occurrence and severity of late toxicities following

CRT in patients with strictly non-endemic NK-NPC.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present clinical retrospective study was

conducted at the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia

(Belgrade, Serbia) between January 2015 and December 2020. The

Multidisciplinary Tumor Board made treatment decisions for every

patient based on current recommendations. Written informed consent

was obtained from all subjects, who were fully aware of the planned

combined treatment and its potential acute and late toxicities.

Information on data publication was included in the consent.

Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study with the

protection of subjects' personal information. Anonymity was

carefully maintained and no disclosure of any personal identifiers

was allowed.

Patient characteristics

A total of 36 adult patients were included from our

non-endemic region (state of Serbia), all with histologically

confirmed, non-metastatic, NK-NPC. Since the Institute for Oncology

and Radiology of Serbia is a referral center for Serbia, patients

not only from Belgrade but from other regions were also included.

Patients treated with palliative intent or previously treated for

another malignancy, those with refractory disease or patients with

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score (ECOG PS) ≥2

were excluded (12). Based on local

findings upon an ear, nose and throat examination with

fiber-endoscopy, a full blood count with biochemical analysis and

radiological imaging [multi-slice computed tomography (CT)/magnetic

resonance imaging of splanchnocranium/head and neck, lung X-rays

and ultrasound of the abdomen], patients were staged according to

the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union

for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) staging system up till

2018 and according to the eight edition of the AJCC/UICC staging

system onwards (13,14).

RT

Radical RT was planned for every patient with a

tumor dose of 70 Gy in 35 fractions, with a standardized

fractionation regimen (2 Gy per fraction) and conformal technique.

After patient immobilization in a supine position with a

thermoplastic immobilization mask, a CT simulation of the head and

neck from the vertex to the fifth thoracic vertebra was performed

obtaining 2.5-mm thick slices with intravenous iodine contrast.

According to the institutional treatment protocol

for the Institute of Oncology and Radiology of Serbia and the

International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements

Reports 50, 62 and 83, target volumes were delineated on each slide

of the CT simulation (15–17). The gross tumor volume (GTV) was

defined by the primary tumor and macroscopic metastatic lymph

nodes.

The high-risk clinical target volume (CTV) included

the GTV with 5-mm margins, and a tumor dose (TD) of 70 Gy in 35

fractions was prescribed to that volume. Intermediate-risk CTV

covered the entire nasopharynx, parapharyngeal space, clivus, base

of the skull, pterygoid fossa, posterior half of ethmoidal sinus,

inferior sphenoid sinus or the whole sphenoid sinus if the tumor

invaded its inferior parts, the posterior edge of the nasal cavity

and the maxillary sinuses. A TD of 60–64 Gy in 30–32 fractions was

prescribed to this volume. Low-risk CTV encompassed

intermediate-risk CTV with prophylactic neck node level I–V and

VIIa bilaterally, with a TD of 50 Gy in 25 fractions prescribed.

This standardized dose configuration was planned for every patient,

respecting the dose constraints on the organs at risk.

To account for the patient motion and set-up error,

each CTV was expanded by 3–5 mm, thus obtaining the planning tumor

volume. More narrow margins (1–3 mm) were used in situations when

the primary tumor was adjacent to a critical neurological

structure.

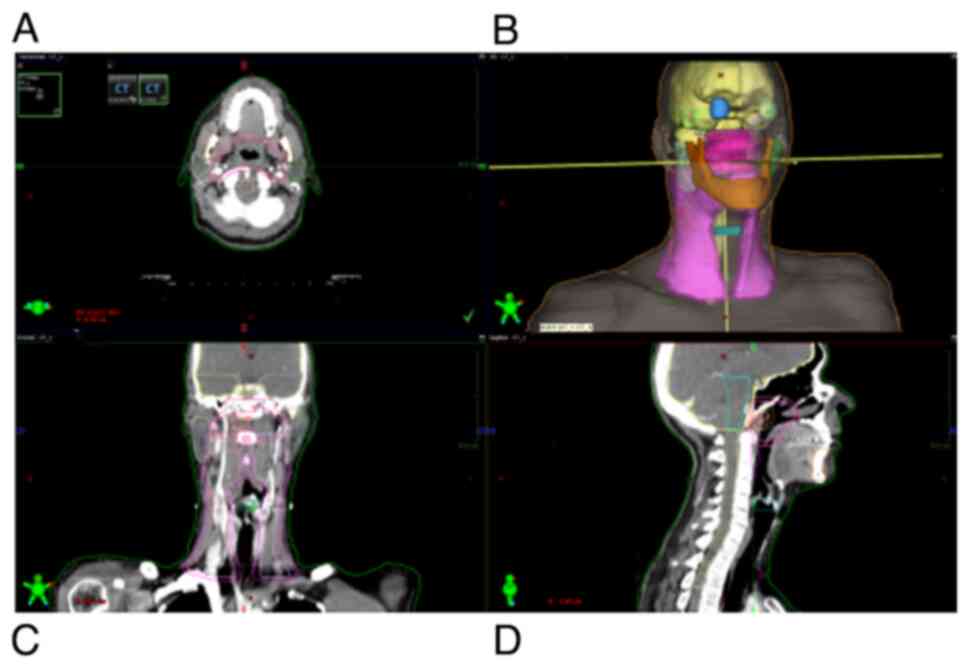

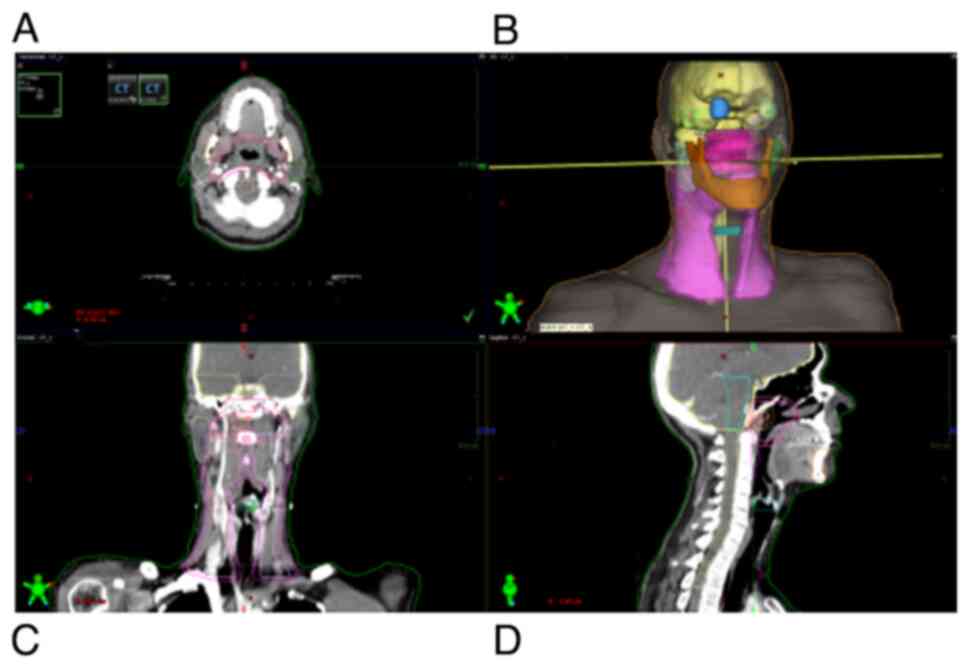

On each slice, organs at risk, including the brain

stem, spinal cord, temporal lobes, brain optic nerves, optic

chiasm, lens, parotid glands, mandible and temporomandibular

joints, were also outlined (Fig.

1). Irradiation was delivered on linear accelerators with

integrated multi-leaf collimators and high-energy photons. Adequate

patient positioning on the RT machine underwent regular everyday

verifications with kV or MV portals and/or cone beam CT.

| Figure 1.Organs at risk and tumor volume

delineation in three planes and in three-dimensional reconstruction

on treatment planning CT simulation taken from the vertex to the

fifth thoracic vertebra. (A) Axial plane, (B) three-dimensional

reconstruction, (C) coronal plane and (D) sagittal plane. Colors

representing OAR: Brain, yellow; brainstem, cyan; optic chiasm,

light orange; spinal cord, light yellow; temporal lobe left,

purple; temporal lobe right, light green; eye globe right, blue;

eye globe left, translucent green; mandible, dark orange; parotid

gland left, dark green; parotid gland right, mint; glottis, dark

cyan. Colors representing tumor volumes: GTVprimary, red; GTVnodal,

dark red; CTV50, magenta; PTV50, pink; CTV60, dark magenta; PTV60,

dark pink; CTV70, light pink; PTV70, light orange. GTV, gross tumor

volume; CTV, clinical target volume; PTV, planning target

volume. |

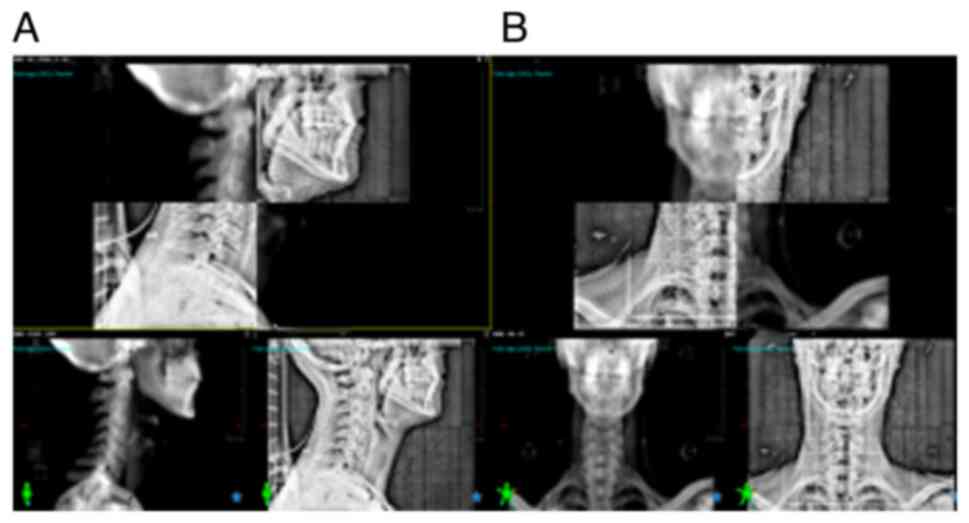

Everyday patient's positioning on the RT machine

demanded a high level of precision, as shown in Fig. 2. Over the study period, RT for

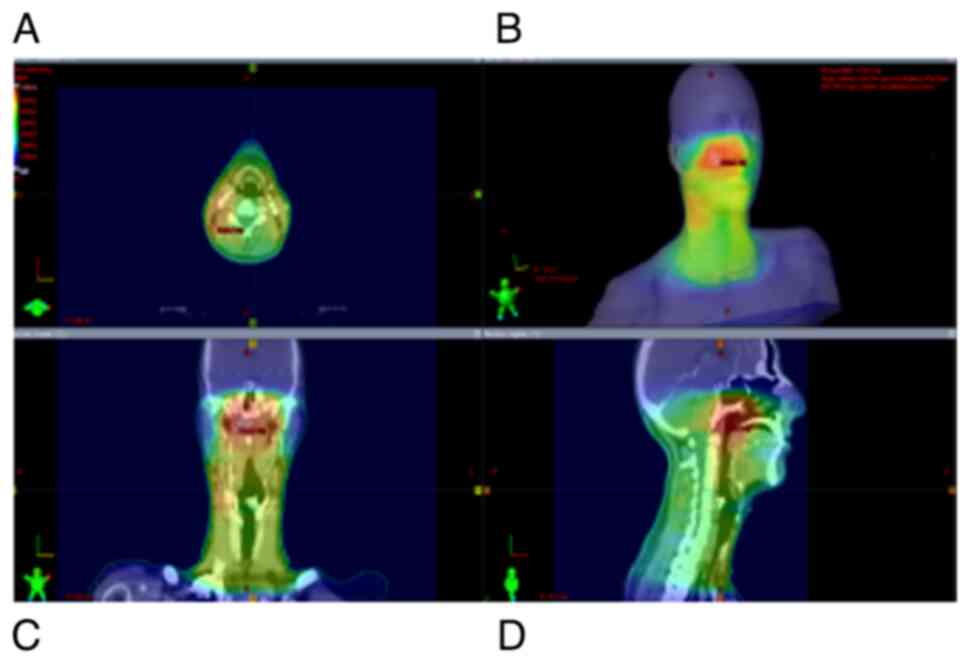

treating NPC patients was delivered with the 3D conformal technique

up until 2018, and with the intensity-modulated radiation therapy

(IMRT) technique afterward, following its implementation in the

Institute of Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (Fig. 3).

Faces shown in the top right panel of Figs. 1 and 3 are digital 3D reconstructions obtained

from three planes (axial, coronal and sagittal) of RT treatment

planning CT, which represents a virtual patient, i.e. a 3D model of

a particular patient which is the concept of 3D-conformal RT.

Figs. 1 and 3 are presented to depict the extreme

proximity of tumor volumes and healthy structures (organs at risk)

in patients' radiation plans, as well as localization and volume of

skin and subcutaneous tissues included in the irradiated

volume.

Chemotherapy

All patients received concurrent cisplatin weekly,

with a dose of 40 mg/m2. The aim was to administer at

least 5 or 6 cycles of mono cisplatin a 40 mg/m2

concurrent with radiation. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was

administered in high-risk patients with locoregional extended

disease. In a subgroup of patients who did not start treatment with

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, yet were assessed as high risk for local

recurrence or distant dissemination upon the completion of CRT, an

adjuvant chemotherapy was applied. Neoadjuvant, as well as an

adjuvant chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin (80 mg/m2)

with 5-fluorouracil (800 mg/m2) continuous infusion for

5 days, recycled every 3 weeks for three cycles.

Follow-up and statistical

analysis

After combined CRT treatment, patients were followed

up every 3 months during the first 2 years, every 6 months from

year 2 to year 5, and once a year thereafter. The late toxicities

were clinician-reported and graded according to the the Radiation

Therapy Oncology Group/European Organization for Research and

Treatment of Cancer ‘Late Radiation Morbidity Scoring Schema’

(18).

Measurements of descriptive statistics are used for

interpretation of the parameters of importance. Categorical

variables are described using frequencies (percentages), while

mean, median, standard deviation and range are used for numeric

variables. For testing normal data distribution, the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. To

compare disease characteristics, treatment details and toxicities,

statistical tests were selected based on data type and

distribution: The Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables,

and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The statistical

analysis was performed with the program R [version 4.3.1

(2023-06-16 ucrt) - ‘Beagle Scouts’; Copyright© 2023 The

R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Platform:

×86_64-w64-mingw32/x64 (64-bit)] (www.r-project.org; downloaded: August 21, 2023).

Results

All patients were >18 years old, with a median

age of 49.5 years (range, 18–71 years) and with good performance

status (ECOG PS≤1). Of the 36 patients included, 27 were men and 9

were women, with a male/female ratio of 3:1. The majority of

patients presented in the advanced stage of disease. Specifically,

47.2% (17 patients) were in clinical stage III and 27.8% (10

patients) were in stage IVA. A total of 25% of the cohort (9

patients) was diagnosed in stage II (Table I).

| Table I.Patients and tumor

characteristics. |

Table I.

Patients and tumor

characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

Median | 49.5 |

|

Range | 18-71 |

| Sex |

|

|

Men | 27 (75.0) |

|

Women | 9 (25.0) |

| ECOG PS |

|

| 0 | 26 (72.2) |

| 1 | 10 (27.8) |

| Comorbidity |

|

|

HTA | 6 (16.7) |

| Heart

disease | 2 (5.6) |

|

Diabetes mellitus | 3 (8.3) |

|

Lung | 1 (2.8) |

|

Depression | 1 (2.8) |

|

Hepatitis | 1 (2.8) |

| Stage |

|

| II | 9 (25.0) |

|

III | 17 (47.2) |

|

IVA | 10 (27.8) |

| T stage |

|

| T1 | 6 (16.7) |

| T2 | 10 (27.8) |

| T3 | 12 (33.33) |

| T4 | 8 (22.2) |

| N stage |

|

| N0 | 4 (11.1) |

| N1 | 12 (33.3) |

| N2 | 17 (47.2) |

| N3 | 3 (8.3) |

In 29 patients (80.6%), treatment commenced with

induction chemotherapy, and all patients completed three cycles. In

the adjuvant setting, 6 patients (16.7%) received chemotherapy,

with a median of two cycles. Whether chemotherapy was administered

in the induction or adjuvant approach, all patients were scheduled

for CRT according to the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board decision

based on current treatment protocols.

Over the study period, RT was delivered with IMRT in

just over one-third of patients (14 patients; 38.9%). The rest of

the patients were treated with 3D conformal RT. The median TD

reached was 68.64 Gy, with a range of 44–70 Gy. Out of the 36

patients, 32 (88.9%) received a TD of 70 Gy in 35 fractions. Only 4

patients did not reach the prescribed dose. In 2 of these patients,

therapy was terminated earlier due to Covid infection (one after a

TD of 62 Gy and the other after a TD of 64 Gy), while 1 patient

refused to continue with CRT after manifestation of an acute

toxicity of severe grade [mucositis grade III according to CTCAE

vs. 4.3 (19)] and reached a TD of

40 Gy. In the fourth patient, the reason for failure to receive the

planned TD was the development of neurological symptomatology

unrelated to primary disease after a TD of 60 Gy.

In the absence of contraindications, from the start

of RT, chemopotentiation was applied with mono cisplatin in the

weekly regimen, with a dose of 40 mg/m2. Six cycles were

realized in 3 patients (8.3%). Most of the patients (11 patients;

30.6%) received five cycles. Four cycles of weekly cisplatin were

applied in 7 patients (19.4%) and three cycles in another 7

patients (19.4%). Five patients (13.9%) received two cycles of

concurrent chemotherapy. The predominant reasons for chemotherapy

withdrawal were hematological and non-hematological acute

toxicities, namely mucositis grade III, dermatitis grade III,

febrile neutropenia, neutropenia grade III and thrombopenia grade

III.

The median number of concomitant cycles was four. In

total, 3 patients (8.3%) received only one cycle. Of these, 1

patient withdrew from further therapy after one cycle of cisplatin

and a TD of 40 Gy due to severe acute toxicity, namely mucositis

grade III, as aforementioned. In another patient, also previously

mentioned, CRT was interrupted after one cycle of mono cisplatin

and a TD of 60 Gy due to central nervous symptomatology

development. In the third patient, further application of

concomitant CT was interrupted due to HCV infection activation, but

RT was completed to a TD of 70 Gy/35 fractions.

After the completion of CRT, during regular

follow-up, late sequelae of any sort were registered in 30 out of

the 36 patients (83.3%). No late sequelae of any type were found in

6 patients (16.7%) (Table II).

| Table II.Distribution of the late

toxicities. |

Table II.

Distribution of the late

toxicities.

| Late toxicity | n (%) |

|---|

| Overall

toxicity | 30 (83.3) |

| Neck fibrosis | 25 (69.4) |

| Late

xerostomia | 21 (58.3) |

| Late dysphagia | 2 (5.6) |

| Secondary

hypothyroidism | 4 (11.1) |

| Secondary

neuropathy | 3 (8.3) |

The most common treatment-related late complication

was neck fibrosis, experienced by 25 patients (69.4%) in the form

of skin thickening and induration, muscle atrophy and loss of

subcutaneous fat. Late xerostomia developed in 21 patients (58.3%).

Only xerostomia grade ≤2 with no notable impact on the dietary

habits was recorded as follows: Grade 1 in 41.67% of the cases and

grade 2 in 16.67%. Only 2 patients (5.6%) developed late dysphagia.

As the most serious and potentially life-threatening outcomes of

this sequela, no instance of aspiration pneumonia or the need for a

feeding tube was recorded. Secondary hypothyroidism as a

post-irradiation consequence developed in 4 patients (11.1%) and

was easily corrected with synthetic thyroid hormone. Neuropathy was

noted in 3 patients (8.3%) in the form of facial numbness,

paresthesia and dysesthesia, and palsy of the VII cranial

nerve.

All registered late adverse events were

statistically analyzed. Due to the sporadic occurrence of late

dysphagia, secondary hypothyroidism and secondary neuropathy, no

significant associations to patient, tumor or treatment

characteristics were found, so the late toxicities that are most

likely to affect the majority of patients treated with CRT were

focused upon.

Exploring the associations between patient

characteristics, no statistically significant difference was found

in the frequency of overall late toxicity (P=0.14), neck fibrosis

(P=0.37) and late xerostomia (P>0.999) between men and women. In

the present study, tumor (T) stage, node (N) stage and clinical

stage of disease did not have a significant impact on late toxicity

prevalence (Table III).

| Table III.Overall toxicity, late neck fibrosis

and late xerostomia associations with tumor and treatment

characteristics analyzed by Fisher's exact test. |

Table III.

Overall toxicity, late neck fibrosis

and late xerostomia associations with tumor and treatment

characteristics analyzed by Fisher's exact test.

| Characteristic | Overall

toxicity | Late neck

fibrosis | Late

xerostomia |

|---|

| Male/female | P=0.14 | P=0.37 | P>0.999 |

| T stage (1–4) | P=0.48 | P=0.90 | P=0.72 |

| N stage (0–3) | P=0.80 | P=0.91 | P=0.43 |

| Clinical stage

(2–4) | P=0.61 | P=0.87 | P=0.51 |

| Neoadj.chemo/no

neoadj.chemo | P=0.58 | P>0.999 | P=0.69 |

| 3D conformal

RT/IMRT | P=0.18 | P>0.999 | P=0.09 |

| Adj.chemo/no

ajd.chemo | P=0.52 | P=0.29 | P=0.65 |

The results imply that the administration of

chemotherapy in different settings, neoadjuvant, concomitant or

adjuvant, has no significant effect on the occurrence of

post-therapy overall toxicity and late neck fibrosis (Table III). However, late xerostomia

occurred significantly more often in patients who received five

cycles compared with that in patients who received less than five

cycles of weekly cisplatin concomitant with RT (P=0.02).

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy applications had no

statistically significant influence on its development.

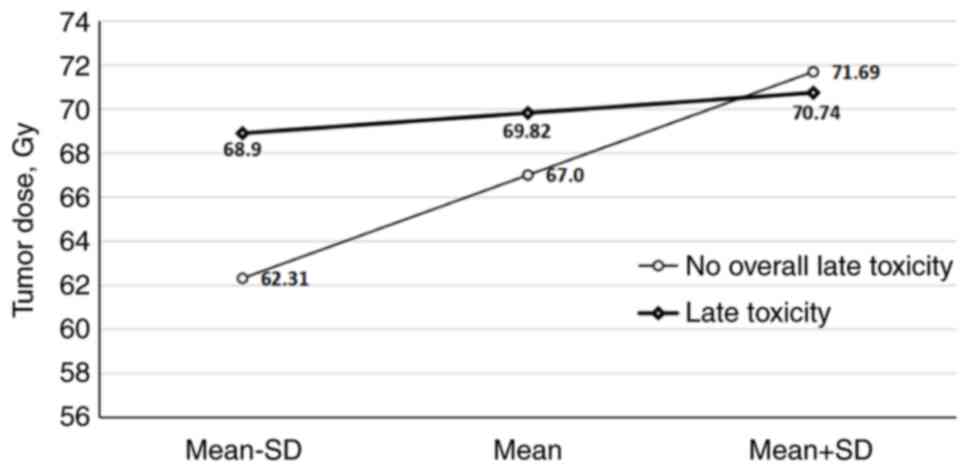

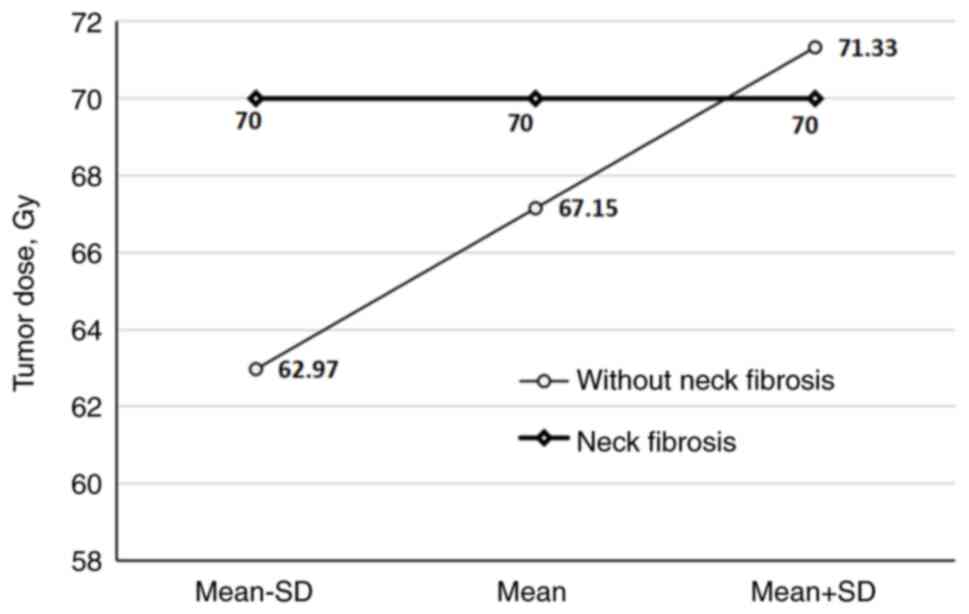

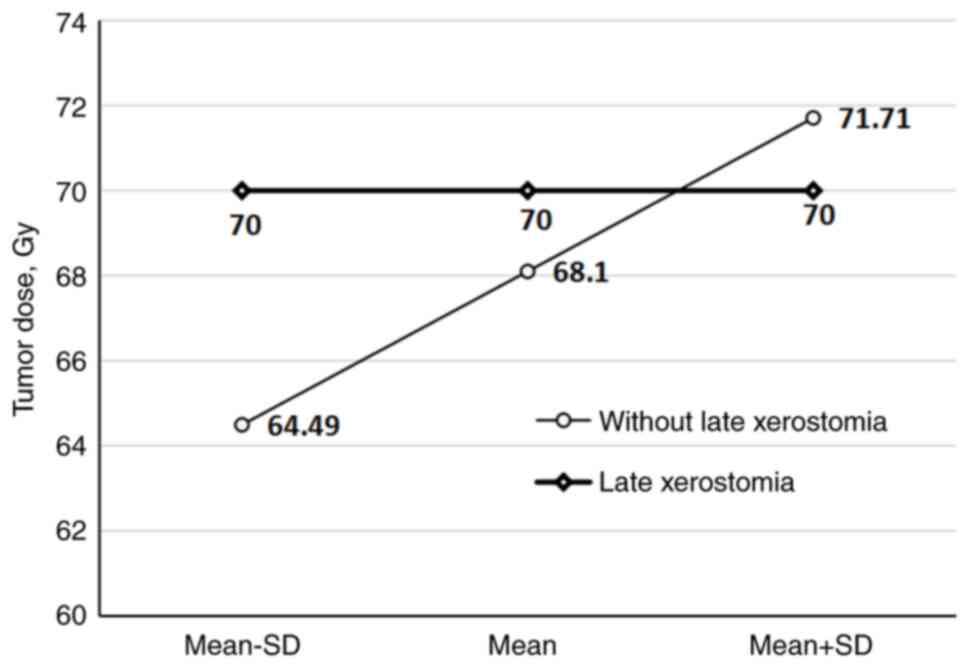

The delivered TD had a substantial impact on the

overall late toxicity, neck fibrosis and late xerostomia frequency

in the patients (P=0.02, P=0.002 and P=0.02, respectively) when a

mean TD of 67.0, 67.15 and 68.1 Gy was reached (Fig. 4, Fig.

5, 6).

Although in the subgroup of 22 patients treated with

3D conformal RT, a type of late post-therapy effect manifested in

66.7% of patients, late fibrosis in 60.0% and secondary xerostomia

in 71.4%, when compared with patients treated with IMRT,

statistical significance with regard to late toxicity incidence was

not reached (P=0.18, P>0.999 and P=0.09, respectively).

Discussion

The last few decades have witnessed immense and

accelerated advances in RT techniques and planning systems, as well

as the appliance of chemotherapy in various sequencing schemes,

along with RT in the management of NPC, thus providing promising

outcomes for treated patients (3,6,20). As

a result of this, survivorship issues emerge. Treatment-induced

late consequences can cause significant morbidity in cancer

survivors, diminish their QoL and even, in rare cases, lead to

death (9). Specific localization of

NK-NPC and notoriously narrow therapeutic margins indicate the

possibility of morphological, functional and esthetic damage.

Unlike acute toxicities, late sequelae are globally more likely to

be unrecognized, underestimated and left without adequate

treatment, even though the majority of patients can suffer from one

or several toxicities. Published data on this topic tend to be

scarce and inconsistent, but also follow the extremely unequal

geographical and ethnic distributions of NK-NPC, dominantly

obtained from the Asian population of patients (8–11). In

such circumstances, results gained from the present retrospective

study of patients with non-endemic NK-NPC have to be discussed and

compared mainly with results registered in Asian-based studies.

In the present study, a male predominance was found

regarding sex distribution, with 75% of patients being men. This is

in strong concordance with data from a meta-analysis by Blanchard

et al (3), which reported

74% of patients being male, and with GLOBOCAN data (1), which imply a male to female ratio of

2–3:1. The median age of 49.5 years is in line with the median age

of <50 years reported in some previous studies (3,21). The

majority of patients in the current study presented in the

locoregional advanced stage of disease, with 72% in stages III and

IVA, due to the aggressive biological behavior of NPC-NK, as shown

across the literature (3,8,9,21,22).

Given their immense potential to negatively

influence the QoL of NPC survivors, late sequelae are gaining

importance within the contemporary scientific community. Much of

our knowledge of this relationship is based on clinician-reported

records. As it has been accepted that clinicians may inadvertently

underestimate symptoms and their severity, oncological interest is

shifting to patient-reported outcomes (PROs) (23,24).

However, the paucity of data from NPC survivors also affects this

aspect of investigation, and only a limited number of clinical

trials have included PROs when performing QoL assessments (22). One of the more recent and important

investigations was performed by McDowell et al (22) in a non-endemic medical center. The

study showed that the five highest-scoring items of PROs were

problems with dry mouth, mucus, swallowing or chewing, memory, and

teeth or gums. Moderate associations between physician-reported

adverse events and PROs were seen for dysphagia, xerostomia,

dysarthria, voice/speech and aspiration. To overcome short-comings

of reporting late post-treatment events, trials dealing with QoL

are suggested to incorporated both PROs and clinician-reported

adverse events.

In the present clinician-reported study, more than

three-quarters of patients developed some form of late toxicity

after completion of combined therapy. To the best of our knowledge,

there is a paucity of data regarding overall post-treatment

toxicities in this particular type of cancer after CRT. Several

reasons can be provided in the explanation of this such as

heterogeneity of baseline patients characteristics, different study

designs, heterogeneity of therapy approaches, rarity of tumor and

insufficient reporting. In a study conducted by Lee et al

(8), in 422 patients treated with

3D conformal RT with a conventional or accelerated fractionation

regimen, with or without chemotherapy, the overall toxicity rate

was 27%, with a markedly greater rate of 37% in the

chemotherapy-based group (16). In

another study performed by Zeng et al (9), higher overall incidence of one or more

late toxicities was registered in 55.8% of patients. Also, the

study emphasized that a notably greater frequency of late sequelae

was found in patients treated with CRT compared to those treated

with RT alone (63.2 vs. 42.0%). Although it is hard to make a

comparison among heterogeneous groups of patients and those with

different treatments, it could be argued that, among the other

aforementioned reasons, differences in ethnicity may play a role in

the greater incidence of overall toxicities in the present study

compared with the incidence of general toxicities in these studies

on the endemic population. No significant impacts of patient and

tumor characteristics on overall post-therapy consequences were

found in the study, in contrast to findings from the study by Zeng

et al (9), which found that

T and N stage categories were significant factors for late

toxicities in general. Previously, Lee et al (8) determined that only patient age was a

strong significant factor in overall late toxicities, but not T and

N tumor stage.

Nearly 70% of patients in the present group

developed subcutaneous neck fibrosis as the most frequent late

toxicity after CRT treatment. In the study conducted by Huang et

al (10), secondary neck

fibrosis was registered in 71.1% of cases in the group of patients

with NPC irradiated using a non-IMRT planning technique; however,

in the group of patients irradiated with IMRT, the frequency of

this late sequela was considerably lower at 34% (18). It should be underlined no

chemotherapy was administered in the study by Huang et al

(10). Zeng et al (9) recorded a neck fibrosis incidence rate

of 34.3% in patients treated with IMRT, and a considerably higher

rate of 45.1% in the group of patients who underwent combined CRT.

In one of the most comprehensive studies coming from a center

outside an endemic region, the study conducted by McDowell et

al (22) reported subcutaneous

neck fibrosis in 55% of patients. Again, RT doses were delivered

with IMRT in all patients. Although this study informs on

physician-reported late toxicities and PROs in patients with NPC

treated with IMRT in a non-endemic center, it should be highlighted

that the majority of the investigated cohort was comprised of

patients born in endemic regions. In addition, 7% of patients in

this study did not receive chemopotentiation. More recently, in

2019, Zhao et al published 10-year results of a phase 2

prospective study where subcutaneous neck fibrosis was present in

91% patients, predominantly of a lesser grade (11). As can be seen from these data, a

wide range of cumulative incidences of this late side effect span

across different clinical studies, even though they were all

conducted on patients from endemic regions, which brings us back to

the pressing issue of inhomogeneity of study designs. It seems that

the present group of non-endemic patients may be more prone to the

neck fibrosis, when keeping in mind that IMRT was applied in just

over one-third of patients and that all of them received one or

more cycles of cisplatin.

According to the previously published studies on

head and neck tumors of various subsites treated with RT, the

frequency of late xerostomia ranged from 64 to 95% depending on

tumor localization, RT planning technique and delivered TD, but

also depending on patient-orientated factors (10,25).

Several studies have strongly supported IMRT in terms of decreasing

permanent xerostomia (20,26,27).

In the present study, late xerostomia was recorded in almost

two-thirds of patients (58.3%), with grade 2 found in 16.7% of

patients. This result aligns closely with that from a study

performed by Lee et al (8),

where only 14% of patients reported grade 2 ×erostomia and 35% of

the patients did not develop xerostomia. In a study by Zeng et

al (9) conducted in 2014 on NPC

survivors irradiated with IMRT with or without chemotherapy,

xerostomia was observed in 78.1% of patients. However, a notably

higher incidence of this long-term consequence was registered in

the study by McDowell et al (22) performed in a non-endemic RT center.

Overall, 95% of the patients treated with IMRT suffered from

low-grade late xerostomia according to physician-reported outcomes

(22). Several reasons for this

discrepancy compared with the present results could be offered,

from the different study designs (cross-sectional cohort study vs.

retrospective study), the longer time to event (subjects enrolled

were disease-free ≥4 years after treatment), the influence of

sample size and differences in adverse events reporting, to the

impact of ethnicity on toxicity manifestation (majority of patients

were of Asian descent). In the study by Huang et al

(10), female survivors were

observed to have a 2.6-fold higher probability of secondary

xerostomia, but a significant association could not be confirmed

between patient and tumor demographics and the later development of

xerostomia (10). While it is well

established that the development and degree of xerostomia is

largely dependent on the dose and volume of the salivary gland in

the radiation field, the role of chemotherapy is less clear and

literature data are somewhat contrasting. Zeng et al

(9) concluded that chemotherapy was

not a relevant factor affecting xerostomia, which agrees with

studies by Miah et al (28)

and Chao et al (29), where

the research was performed on patients with head and neck cancer.

By contrast, the study by Ou et al (30) demonstrated that concurrent

chemotherapy significantly increased xerostomia compared to RT

alone (46.4 vs. 36.3%), as well as total cisplatin dose increasing

overall late toxicities. That being said, the present result is

comparable with the findings from previously mentioned studies

regarding the cumulative prevalence rate of xerostomia even though

the patients were irradiated both with non-IMRT and IMRT planning

techniques. Also, in alignment with the results by Ou et al

(30), the present study

demonstrated a statically significant impact of cisplatin

chemopotentiation on late xerostomia prevalence, with a median of 5

cycles (P=0.02).

The only common significant factor for overall late

sequela and the most prevalent ones (subcutaneous neck fibrosis and

late xerostomia) that could be identified in the present study was

the delivered TD (P=0.02, P=0.002 and P=0.02, respectively). The

difference became statistically significant when the mean TDs of

67.0, 67.15 and 68.1 Gy were reached. The cumulative incidences of

these three chronic toxicities were numerically notably lower in

the subgroup of patients irradiated with IMRT in comparison to

patients irradiated with 3D conformal RT, but the differences did

not reach statistical significance, possibly due to the small

sample size.

On the matter of cranial neuropathy, which presented

with numbness, faint pain and cranial nerve palsy in the current

patients, the record of 8.3% in this population of patients is

comparable with published data. For example, in a study performed

by Huang et al (10), in the

group of patients irradiated with non-IMRT, neuropathy was found in

19.1% of cases, while notably less, only 5.0% of cases, exhibited

neuropathy in the group of patients irradiated with IMRT. Also,

Zeng et al (9) reported a

frequency of 2.2% for cranial neuropathy in patients treated with

CRT, and Zhao et al (11)

reported a frequency of 6.5% in patients irradiated with the IMRT

technique only. These numbers are in close alignment with the

results of the present study. Notably, during the study period, no

case of temporal lobe necrosis, as the most severe scenario of

neuropathy, was registered in the present patient cohort.

One of the most troublesome late sequela is late

dysphagia due to its potential to cause aspiration and a decrease

in body mass index. Across the literature, data are scarce and

heterogeneous. Huang et al (10) found 53.5% of cases with late

dysphagia in a non-IMRT group of patients and 22% of cases in the

IMRT group. By contrast, only 1.3% of this sequela was reported in

the study by Ou et al (30).

The present finding of 5.6% late dysphagia of lesser grade is

closer to that of the latter study.

Secondary hypothyroidism was registered in 11.1% of

cases in the present study, which is slightly higher than the rate

in the study by Lee et al (8), where 6.6% patients developed this

hormonal dysfunction.

As already mentioned, NK-NPC is a malignant disease

with prominent ethnic and geographical disparities, so the vast

majority of studies considered regarding this topic are conducted

in the endemic population, with practically no studies performed in

non-endemic regions (8–11,29,30).

It is particularly relevant to contrast and compare results driven

from both regions, since treatment protocol is still based on a

‘one size fits all’ approach, and the ultimate goal in modern

oncology tends to be individualization and optimization of

therapy.

Novel promising therapeutical approaches are,

however, changing the landscape of NPC therapy. In the aspect of RT

options, intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) is proven to

have dosimetry advantages over IMRT, thus facilitating the delivery

of markedly reduced radiation doses to surrounding normal tissues.

However, according to the study conducted by Li et al

(31) on 77 patients with

non-metastatic NPC, differences in the incidence of grade 3 or

higher late toxicities between groups of patients treated with IMPT

and IMRT were not significant. The median follow-up in this study

was 2 years and it could be a potential factor impacting such

results.

Current perspectives on immunotherapy and targeted

therapy application in NK-NPC are established in recurrent and

metastatic settings. There are numerous ongoing prospective

clinical trials at phases II and III exploring the role of

treatments in a locoregional advanced stage of NPC (clinical trial

numbers: NCT06019130, NCT04833257, NCT02421640, NCT05628922 and

NCT06781112). Efficacy and safety results are highly

anticipated.

The present study, inevitably, has several

limitations. The study included subjects treated in the Department

of Radiotherapy for Solid Tumors and Hematological Malignancies,

Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (Belgrade, Serbia)

within a 5-year period, between January 2015 and December 2020. The

study was closed in 2022, so there was a minimum 2-year period of

follow-up, making it enough time for late sequelae to manifest and

to be recorded, as these occur as early as 6 months after

completion of RT. However, this was a shorter follow-up period for

those patients treated in 2020, compared with those treated in

2015, which should be considered as a limitation of the study, as

it could lead to underestimation of late toxicity occurrence in

that subgroup of patients due to the long latency. It has been

proposed by several studies that time-to-event analyses could

address this issue (32,33). The retrospective nature of the study

should be taken as a major limitation factor that could underpower

the conclusions. A relatively small sample number could also be

perceived as a limitation to the results. Further investigations

with pooled data from another non-endemic centers would be of a

tremendous importance.

In conclusion, according to the results of the

present study, the majority of patients with non-endemic NK-NPC who

underwent CRT will experience some form of late toxicities, but

predominantly of lesser grade. The most frequent registered late

toxicity is neck fibrosis, followed by xerostomia. In the constant

attempt to improve treatment, aiming for remission or prolongation

of a patient's lifetime, the importance of late morbidities is

increasingly being recognized and should be justified by further

research, especially in the challenging field of NK-NPC. The impact

of ethnic differences on the manifestation of post-treatment

complications is quite undetermined, and possibly, underestimated,

therefore investigations in the non-endemic population of patients

are warranted.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JJR, TA and MN were responsible for study

conceptualization. JJR, TA and NJK were responsible for the design

of the study methodology. Data acquisition was performed by JJR, VV

and NJK. Statistical analysis was performed by JJR. Data

interpretation was performed by JJR, TA, MN and VV. Original draft

preparation was the responsibility of JJR. TA and MN critically

reviewed and edited the manuscript. Final approval was granted by

TA and MN. JJR, TA and VV confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines

of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were

waived in this study, since no experiments or novel treatments were

conducted on humans. The methodology represents a standard

treatment modality that does not need ethical approval. The

decision to treat the patients in the manner described in the study

was made by the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board of the Institute for

Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (Belgrade, Serbia) according to

the current treatment protocols. Written informed consent was

obtained for all subjects involved in the study.

The manuscript is a part of the academic

sub-specialistic thesis of JJR approved by the Faculty of Medicine,

University of Belgrade (Belgrade, Serbia) on May 30, 2022 (protocol

number: 04 BR:20-UON-10). The Institute for Oncology and Radiology

of Serbia serves as a scientific teaching base for the Faculty of

Medicine of University of Belgrade.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained for all

subjects involved in the study. Before obtaining the consent,

patients were thoroughly informed about all aspects of the planned

combined treatment, its effects, possible acute and late

toxicities. All subjects were fully aware that the data would be

published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata

T and Slootweg PJ: WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. WHO

Classification of Tumours. 9. 4th edition. IARC Publications; Lyon:

pp. 65–69. 2017

|

|

3

|

Blanchard P, Lee A, Marguet S, Leclercq J,

Ng WT, Ma J, Chan AT, Huang PY, Benhamou E, Zhu G, et al:

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An

update of the MAC-NPC meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 16:645–655.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lee AW, Ng WT, Pan JJ, Poh SS, Ahn YC,

AlHussain H, Corry J, Grau C, Grégoire V Harrington KJ, et al:

International guideline for the delineation of the clinical target

volumes (CTV) for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol.

126:25–36. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri PG, Fu KK,

Cooper J, Vuong T, Forastiere AA, Adams G, Sakr WA, Schuller DE and

Ensley JF: Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with

advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: Phase III randomized Intergroup

study 0099. J Clin Oncol. 16:1310–1317. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen QY, Wen YF, Guo L, Liu H, Huang PY,

Mo HY, Li NW, Xiang YQ, Luo DH, Qiu F, et al: Concurrent

chemoradiotherapy vs radiotherapy alone in stage II nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: Phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst.

103:1761–1770. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chan AT, Leung SF, Ngan RK, Teo PM, Lau

WH, Kwan WH, Hui EP, Yiu HY, Yeo W, Cheung FY, et al: Overall

survival after concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy compared with

radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 97:536–539. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee AW, Ng WT, Hung WM, Choi CW, Tung R,

Ling YH, Cheng PT, Yau TK, Chang AT, Leung SK, et al: Major late

toxicities after conformal radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal

carcinoma-patient- and treatment-related risk factors. Int J Radiat

Oncol Biol Phys. 73:1121–1128. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zeng L, Tian YM, Sun XM, Chen CY, Han F,

Xiao WW, Deng XW and Lu TX: Late toxicities after

intensity-modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma:

Patient and treatment-related risk factors. Br J Cancer. 110:49–54.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Huang TL, Chien CY, Tsai WL, Liao KC, Chou

SY, Lin HC, Dean Luo S, Lee TF, Lee CH and Fang FM: Long-term late

toxicities and quality of life for survivors of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus

non-intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Head Neck. 38 (Suppl

1):E1026–E1032. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao C, Miao JJ, Hua YJ, Wang L, Han F, Lu

LX, Xiao WW, Wu HJ, Zhu MY, Huang SM, et al: Locoregional control

and mild late toxicity after reducing target volumes and radiation

doses in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal

carcinoma treated with induction chemotherapy (IC) followed by

concurrent chemoradiotherapy: 10-year results of a phase 2 study.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 104:836–844. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG,

Greene FL and Trotti A: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edition.

Springer; Paris: 2010, Available from. http://www.springer.com/medicine/surgery/book/978-0-387-88440-0

|

|

14

|

Head and Neck Cancer Study Group (HNCSG),

. Monden N, Asakage T, Kiyota N, Homma A, Matsuura K, Hanai N,

Kodaira T, Zenda S, Fujii H, et al: A review of head and neck

cancer staging system in the TNM classification of malignant tumors

(eight edition). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 49:589–595. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

ICRU Report 50, . Prescribing, Recording,

and Reporting Photon Beam Therapy. International Commission on

Radiation Units and Measurements; Bethesda, MD: 1993

|

|

16

|

ICRU Report 62, . Prescribing, Recording,

and Reporting Photon Beam Therapy (Supplement to ICRU Report 50).

International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements;

Bethesda, MD: 1999

|

|

17

|

Hodapp N: The ICRU Report 83: Prescribing,

recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation

therapy (IMRT). Strahlenther Onkol. 188:97–99. 2012.(In German).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Late effects consensus conference, .

RTOG/EORTC. Radiother Oncol. 35:5–7. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0

(CTCAE). https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/ctcae_4.03_2010-06-14_quickreference_5×7.pdfMay

31–2023

|

|

20

|

Lee AW, Ng WT, Chan LL, Hung WM, Chan CC,

Sze HC, Chan OS, Chang AT and Yeung RM: Evolution of treatment for

nasopharyngeal cancer-success and setback in the

intensity-modulated radiotherapy era. Radiother Oncol. 110:377–384.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ozdemir S, Akin M, Coban Y, Yildirim C and

Uzel O: Acute toxicity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated

with IMRT/VMAT. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 16:1897–1900. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

McDowell LJ, Rock K, Xu W, Chan B, Waldron

J, Lu L, Ezzat S, Pothier D, Bernstein LJ, So N, et al: Long-term

late toxicity, quality of life, and emotional distress in patients

with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity modulated

radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 102:340–352. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, Hsieh YC and

Beer TM: How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy

adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from

the quality-of-life questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 22:3485–3490.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, Harris

JJ, Hendricks CB, Levin B, Link MP, Lustig C, McLaughlin J, Ried

LD, et al: National institutes of health state-of-the-science

conference statement: Symptom management in cancer: Pain,

depression, and fatigue, july 15–17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst.

95:1110–1117. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jasmer KJ, Gilman KE, Muñoz Forti K,

Weisman GA and Limesand KH: Radiation-induced salivary gland

dysfunction: Mechanisms, therapeutics and future directions. J Clin

Med. 9:40952020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Alterio D, Gugliandolo SG, Augugliaro M,

Marvaso G, Gandini S, Bellerba F, Russell-Edu SW, De Simone I,

Cinquini M, Starzyńska A, et al: IMRT versus 2D/3D conformal RT in

oropharyngeal cancer: A review of the literature and meta-analysis.

Oral Dis. 27:1644–1653. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ,

Urbano TG, Bhide SA, Clark C, Miles EA, Miah AB, Newbold K, Tanay

M, et al: Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional

radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): A phase 3

multicentre randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 12:127–136.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Miah AB, Gulliford SL, Bhide SA, Zaidi SH,

Newbold KL, Harrington KJ and Nutting CM: The effect of concomitant

chemotherapy on parotid gland function following head and neck

IMRT. Radiother Oncol. 106:346–351. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chao KS, Deasy JO, Markman J, Haynie J,

Perez CA, Purdy JA and Low DA: A prospective study of salivary

function sparing in patients with head-and-neck cancers receiving

intensity-modulated or three-dimensional radiation therapy: Initial

results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 49:907–916. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ou X, Zhou X, Shi Q, Xing X, Yang Y, Xu T,

Shen C, Wang X, He X, Kong L, et al: Treatment outcomes and late

toxicities of 869 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated

with definitive intensity modulated radiation therapy: new insight

into the value of total dose of cisplatin and radiation boost.

Oncotarget. 6:38381–38397. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li X, Kitpanit S, Lee A, Mah D, Sine K,

Sherman EJ, Dunn LA, Michel LS, Fetten J, Zakeri K, et al: Toxicity

profiles and survival outcomes among patients with nonmetastatic

nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated proton

therapy vs intensity-modulated radiation therapy. JAMA Netw Open.

4:e21132052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bentzen SM, Dorr W, Anscher MS, Denham JW,

Hauer-Jensen M, Marks LB and Williams J: Normal tissue effects:

Reporting and analysis. Semin Radiat Oncol. 13:189–202. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Vittrup AS, Kirchheiner K, Fokdal LU,

Bentze SM, Nout RA, Pötter R and Tanderup K: Reporting of late

morbidity after radiation therapy in large prospective studies: A

descriptive review of the current status. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 105:957–967. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|