Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of

cancer-related morbidity and mortality globally; it accounts for ~2

million new cases and 1.76 million deaths per year, with rates

continuing to increase (1).

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for >85% of all lung

cancer cases (2). A notable

proportion of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages of the

disease, and the treatment for these patients typically involves

radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy

(3,4). However, despite these comprehensive

approaches, outcomes for patients with advanced lung cancer are

often poor, with such cases classified as advanced refractory lung

cancer (5). Currently, there is no

established optimal clinical treatment for advanced refractory

NSCLC, with most patients receiving primarily palliative and

symptomatic supportive care (6).

This highlights the urgent need for developing more effective and

targeted therapeutic strategies to improve the prognosis of these

patients.

Advancements in precision medicine have highlighted

the clinical potential of localized therapies, such as bronchial

artery chemoembolization (BACE) and iodine-125 seed implantation,

which are increasingly recognized as important therapeutic options.

Iodine-125 seed implantation, a type of brachytherapy, involves

placing iodine-125 seeds directly into tumor tissues. These seeds

emit low-dose γ-rays continuously, selectively targeting and

destroying cancer cells whilst minimizing radiation exposure to

surrounding healthy tissues and reducing collateral damage

(7). BACE delivers chemotherapeutic

agents and embolic materials directly into tumor-feeding arteries

using a catheter, ensuring high localized drug concentrations. This

approach not only enhances the effects of the drugs but also

decreases the blood supply to the tumor, inducing ischemia, which

ultimately result in necrosis (8).

Compared with systemic chemotherapy, BACE markedly improves the

local efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs whilst reducing systemic

side effects (9). However,

conventional embolization materials, such as gelatin sponge and

polyvinyl alcohol particles, have notable limitations, including

incomplete embolization and a higher risk of complications

(10).

8Spheres microspheres, a novel embolic material

comprising a polyvinyl alcohol skeleton with covalent bonding and

cross-linking agents, exhibit excellent elasticity and compliance.

These characteristics enable more uniform embolization of

tumor-feeding arteries, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes, and

their potential as a localized therapy has attracted considerable

attention (11).

Building on these advancements, the present study

aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combining 8Spheres

microsphere embolization with iodine-125 seed implantation for

treating advanced refractory NSCLC. Using retrospective clinical

data, the study compared outcomes between the combined treatment

group and the iodine-125 seed implantation group. Furthermore, the

analysis assessed the potential of the combined regimen to enhance

therapeutic effectiveness, extend patient survival, minimize

treatment-related side effects and provide a scientific foundation

for the broader adoption of this innovative therapeutic

approach.

Materials and methods

Patient population

The present study retrospectively reviewed 45

patients with advanced refractory NSCLC who were treated at The

First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University

(Chongqing, China) between January 2020 and December 2022. The

study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the First

Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. As a

retrospective analysis, the need for patient consent was waived,

and all data were anonymized. The inclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Histopathologically-confirmed diagnosis of NSCLC; ii)

tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage (12) IIIB or IVA with manageable distant

metastatic tumors; iii) prior treatment failure, including

radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy; iv)

at least one measurable tumor focus as defined by Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (13); v) expected survival of >6 months

based on clinical assessment at the start of treatment; and vi) an

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score

(14) of 0–2. The exclusion

criteria included the following: i) History of iodine allergy or

allergy to the chemotherapeutic drugs used; ii) comorbid severe

cardiovascular disease (New York Heart Association class III–IV)

(15), severe psychiatric disorder

or other severe physical illness; iii) immune dysfunction or

coagulation dysfunction; and iv) cognitive dysfunction.

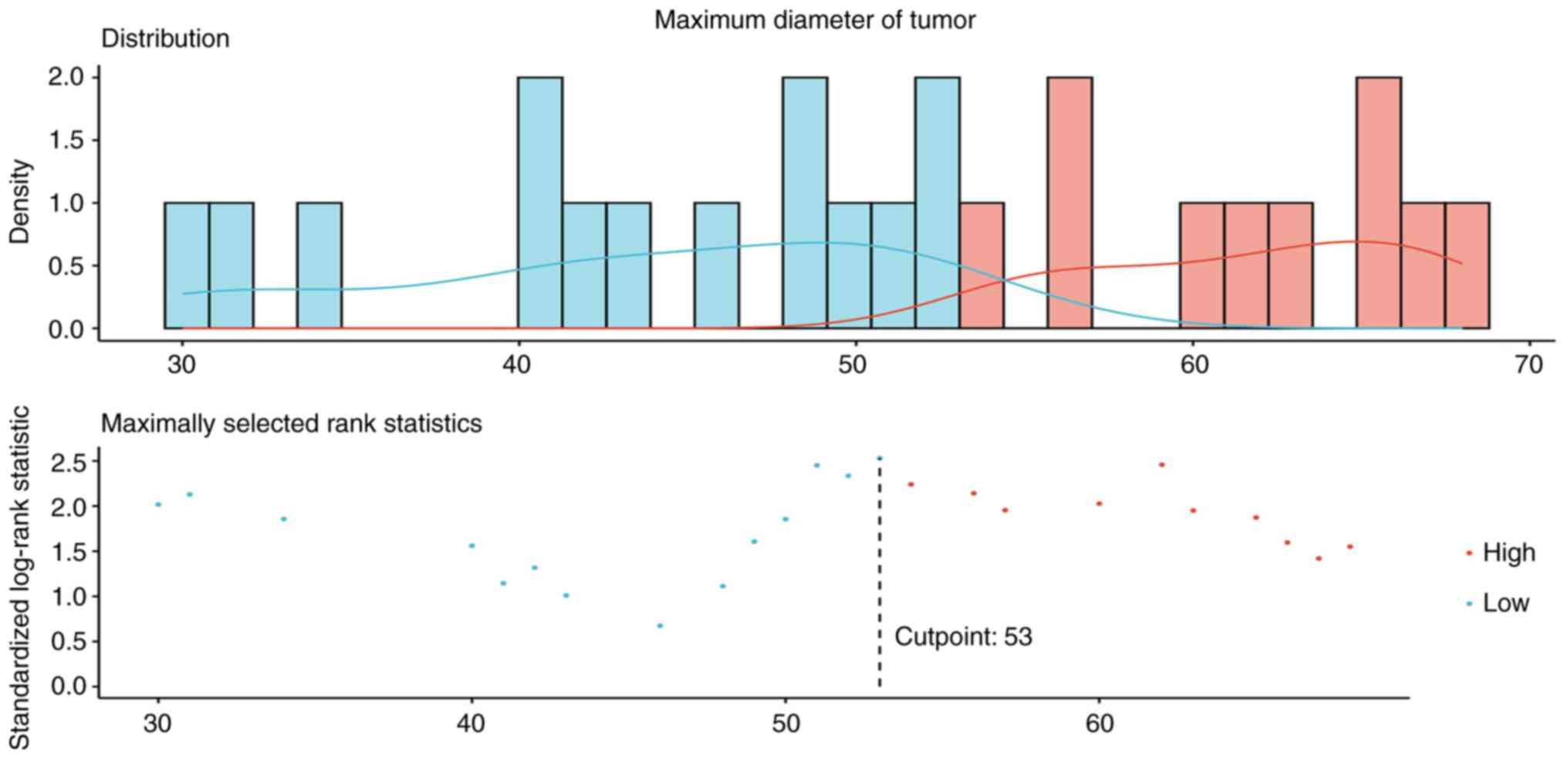

The patients were categorized into a test group and

a control group (Table I). The test

group comprised 23 patients who received 8Spheres microsphere

embolization combined with bronchial artery perfusion chemotherapy

and iodine-125 seed implantation. This group included 13 men and 10

women, with 8 patients aged ≤60 years and 15 aged >60 years. A

total of 14 patients had adenocarcinoma, and nine had squamous

carcinoma. Tumor diameters were ≤53 mm in 12 cases and >53 mm in

11 cases. TNM staging indicated stage IIIB in 13 patients and stage

IVA in 10 patients. The control group consisted of 22 patients

treated with iodine-125 seed implantation alone. This group

included 12 men and 10 women, with 4 patients aged ≤60 years and 18

aged >60 years. Adenocarcinoma was observed in 13 cases, and

squamous carcinoma in 9 cases. Tumor diameters were ≤53 mm in 13

cases and >53 mm in 9 cases (Fig.

1). TNM staging indicated stage IIIB in 10 patients and stage

IVA in 12 patients. All patients were last followed up in June

2024.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of the

patients in each treatment group. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of the

patients in each treatment group.

| Characteristic | Test group

(n=23) | Control group

(n=22) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age |

|

| 1.585 | 0.208 |

| ≤60

years | 8 (34.8) | 4 (18.2) |

|

|

| >60

years | 15 (65.2) | 18 (81.8) |

|

|

| Sex |

|

| 0.018 | 0.894 |

|

Male | 13 (56.5) | 12 (54.5) |

|

|

|

Female | 10 (43.5) | 10 (45.5) |

|

|

| ECOG

PSa |

|

| N/A | 0.999 |

| 0 | 1 (4.4) | 1 (4.6) |

|

|

| 1 | 15 (65.2) | 14 (63.6) |

|

|

| 2 | 7 (30.4) | 7 (31.8) |

|

|

| Pathological

type |

|

| 0.015 | 0.903 |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 14 (60.9) | 13 (59.1) |

|

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma | 9 (39.1) | 9 (40.9) |

|

|

| TNM stage |

|

| 0.551 | 0.458 |

|

IIIB | 13 (56.5) | 10 (45.5) |

|

|

|

IVA | 10 (43.5) | 12 (54.5) |

|

|

| Maximum tumor

diameter |

|

| 0.218 | 0.641 |

| ≤53

mm | 12 (52.2) | 13 (59.1) |

|

|

| >53

mm | 11 (47.8) | 9 (40.9) |

|

|

| PFS | 12 (10–19) | 10 (6–12) | 2.769 | 0.006 |

| OS | 19 (13–24) | 12 (10–21) | 2.140 | 0.032 |

Treatment methods

Standard preoperative evaluations were performed on

all patients, which included screenings for infectious disorders

(human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome,

syphilis and hepatitis), coagulation function evaluations, liver

and kidney function testing and comprehensive blood and urine

tests. Additional evaluations included electrocardiograms, cardiac

enzyme tests and contrast-enhanced chest CT scans. Informed consent

was obtained from all patients for iodine-125 seed implantation,

bronchial artery chemoembolization and other related

procedures.

Patients in the control group received only

iodine-125 seed implantation. Treatment plans were created using

the Therapy Planning System (Beijing Astro Technology Co., Ltd.),

which outlined the needle insertion route and angle, the number of

needles to be implanted and the arrangement of the particles. The

iodine-125 seeds, purchased from Beijing Atom High-Tech Co., Ltd.,

had a diameter of 0.8 mm and a length of 4.5 mm, with a titanium

shell, an activity of 0.6–0.8 mCi, a half-life of 59.6 days, and a

prescribed dose of 120–140 Gy. The procedure was performed under

local anesthesia using a Revolution™ HD CT scanner (GE

Healthcare). CT-guided implantation was performed using a layer

thickness of 5 mm, following the planned protocol.

Patients in the test group underwent BACE 4–6 days

after iodine-125 seed implantation (using the same protocol as in

the control group). The procedure involved the following steps: The

right femoral artery was punctured and a 5F RLG catheter (Terumo

Corporation) was selectively inserted into the bronchial artery for

angiography. Other arteries, such as the phrenic and internal

thoracic arteries, were also assessed to identify the blood supply

of the tumor if needed. A 2.7F microcatheter (APT Medical Inc.) was

then super-selectively inserted into the target tumor vessel.

Chemotherapy drugs were administered first, following oncological

guidelines (National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for

Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer) (16).

For patients with adenocarcinoma, 500 mg/m2 pemetrexed

disodium + 75 mg/m2cisplatin was administered, whilst

for patients with squamous carcinoma, 135 mg/m2

paclitaxel + area under the curve 5 carboplatin was administered.

After chemotherapy, embolization was performed using 8Spheres

microspheres (Suzhou Hengrui Medical Devices Co., Ltd.) with a

diameter of 300–500 µm. The microspheres were injected into the

target vessel at a rate of 1 ml/min. The embolization effect was

evaluated using digital subtraction angiography (DSA). If needed,

additional embolization was performed based on DSA findings.

Efficacy evaluation

Efficacy was evaluated using the RECIST 1.1

guidelines (13). Efficacy

categories included complete remission (CR), defined as the total

disappearance of all target lesions; partial remission (PR),

defined as a ≥30% reduction in the maximum diameter of target

lesions; stable disease (SD), defined as insufficient change in

lesion size to meet the criteria for PR or progressive disease

(PD); and PD, defined as a ≥20% increase in the maximum diameter of

target lesions. The efficacy metrics were calculated using the

following formulae: Objective response rate (ORR)=CR + PR; and

disease control rate (DCR)=CR + PR + SD. Patients were evaluated

for efficacy at 2, 4, and 6 months after treatment.

Adverse reactions and

complications

All adverse reactions and complications occurring

during and after treatment were recorded, including pneumothorax,

chest pain, fever, gastrointestinal symptoms and hemoptysis. The

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events was used to

categorize adverse reactions (17)

and promptly addressed to ensure patient safety.

Follow-up

All patients were regularly followed up after

treatment until June 2024, death or loss to follow-up. Follow-up

visits were scheduled every 2 months during the first 6 months and

every 3 months thereafter. These visits included physical

examinations, assessments of lesion progression, blood tests,

evaluations of liver and kidney function, and chest imaging.

Follow-ups focused on evaluating progression-free survival (PFS)

and overall survival (OS).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 29.0 (IBM Corp.) and R

(version 4.3.1; The R Foundation). The normality of continuous

variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Based on the

distribution, continuous data are presented as mean ± standard

deviation if normally distributed, or as median (interquartile

range) if not. Baseline characteristics between the groups were

compared using either a two-sample t-test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum

test, depending on the data distribution. For categorical data

analysis, the χ2 test was applied for variables with

expected frequencies ≥5 in all cells, whereas the Fisher's exact

test was used to analyze variables with small sample sizes or

expected frequencies <5. Survival analyses included all patients

and were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with group

comparisons made using the log-rank test. The optimal cutoff value

for the maximum tumor diameter, as a treatment-related continuous

variable, was calculated using the surv_cutpoint function in the R

package ‘survminer’ (version 0.5.0) (18). The effect sizes of several factors

were assessed using Cox proportional hazards analysis. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Analysis of treatment response

At 2 months, the ORR for patients in the test and

control groups was 82.6 and 40.9%, respectively

(χ2=8.318; P<0.05), whilst the DCR was 100% for both

groups. At 4 months, the ORR was 87.0 and 59.1%, respectively

(χ2=4.465; P<0.05), and the DCR was 95.7 and 86.4%,

respectively (χ2=0.325; P>0.05). At 6 months, the ORR

was 82.6 and 50.0%, respectively (χ2=5.380; P<0.05),

whilst the DCR was 91.3 and 77.3%, respectively

(χ2=0.786; P>0.05). These findings are summarized in

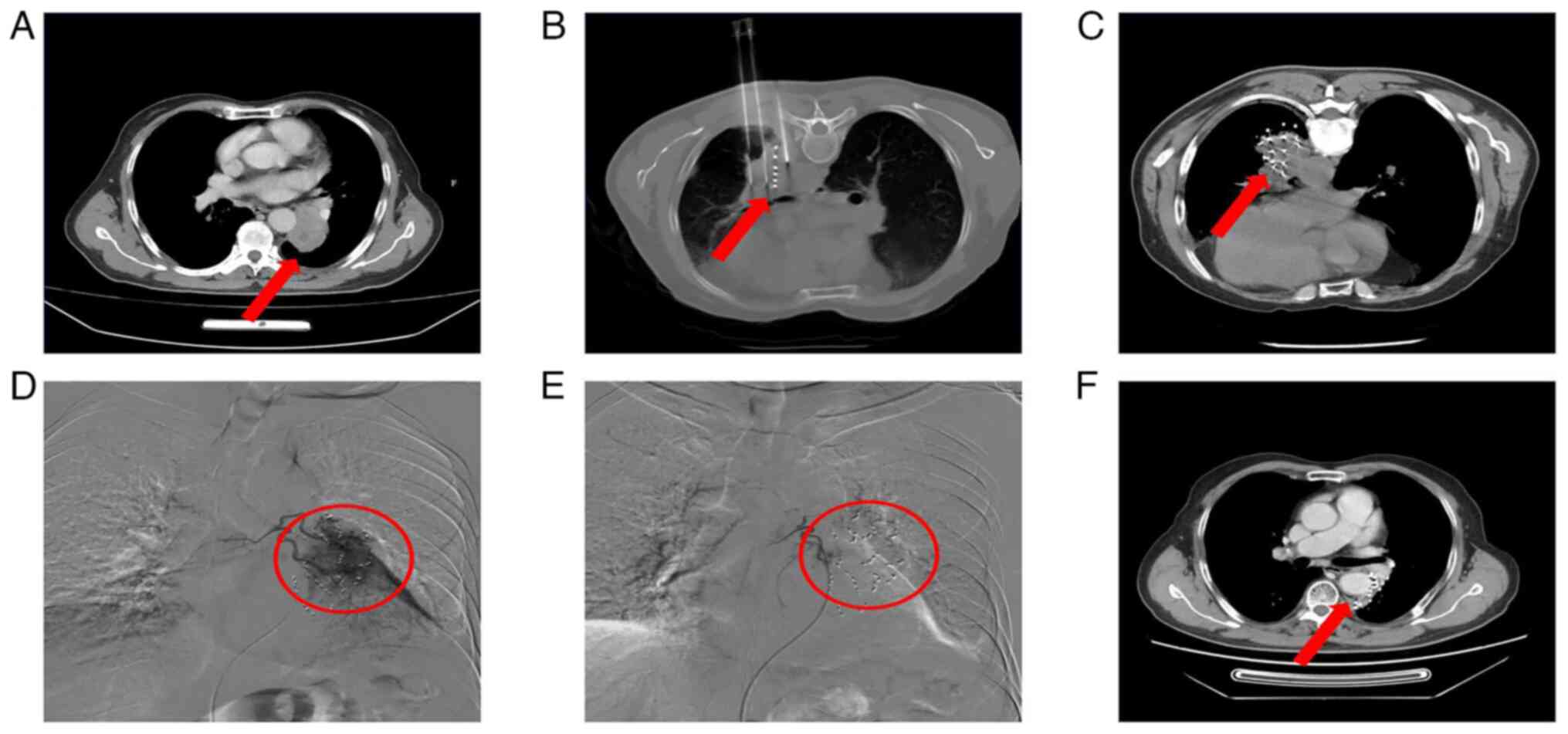

Table II. A comparison between the

imaging results for patients in the experimental group before and

after treatment is presented in Fig.

2.

| Table II.Comparison of outcomes in patients

with different treatments. |

Table II.

Comparison of outcomes in patients

with different treatments.

| A, 2 months |

|---|

|

|---|

| Outcome | Test group

(n=23) | Control group

(n=22) |

|---|

| CR | 2 | 0 |

| PR | 17 | 9 |

| SD | 4 | 13 |

| PD | 0 | 0 |

| ORR, % | 82.6 | 40.9 |

| DCR, % | 100.0 | 100.0 |

|

| B, 4

months |

|

| Outcome | Test group

(n=23) | Control group

(n=22) |

|

| CR | 5 | 3 |

| PR | 15 | 10 |

| SD | 2 | 6 |

| PD | 1 | 3 |

| ORR, % | 87.0 | 59.1 |

| DCR, % | 95.7 | 86.4 |

|

| C, 6

months |

|

| Outcome | Test group

(n=23) | Control group

(n=22) |

|

| CR | 7 | 3 |

| PR | 12 | 8 |

| SD | 2 | 6 |

| PD | 2 | 5 |

| ORR, % | 82.6 | 50.0 |

| DCR, % | 91.3 | 77.3 |

Analysis of survival probability

The baseline characteristics of patients selecting

different treatment regimens were comparable between the two groups

(P>0.05); however, statistically significant differences were

demonstrated for the median PFS and OS between the groups (Table I). Among the patients in the test

group, 12/23 (52.2%) had previously received chemotherapy with the

aforementioned regimens, whilst 11/23 (47.8%) had not. In the

control group, 10/22 (45.5%) had previously received chemotherapy

with the aforementioned regimens, and 12/22 (54.5%) had not. The

results revealed no significant difference in ORR (P=0.213) or DCR

(P=0.456) between subgroups, suggesting that prior chemotherapeutic

agents use did not significantly influence the observed treatment

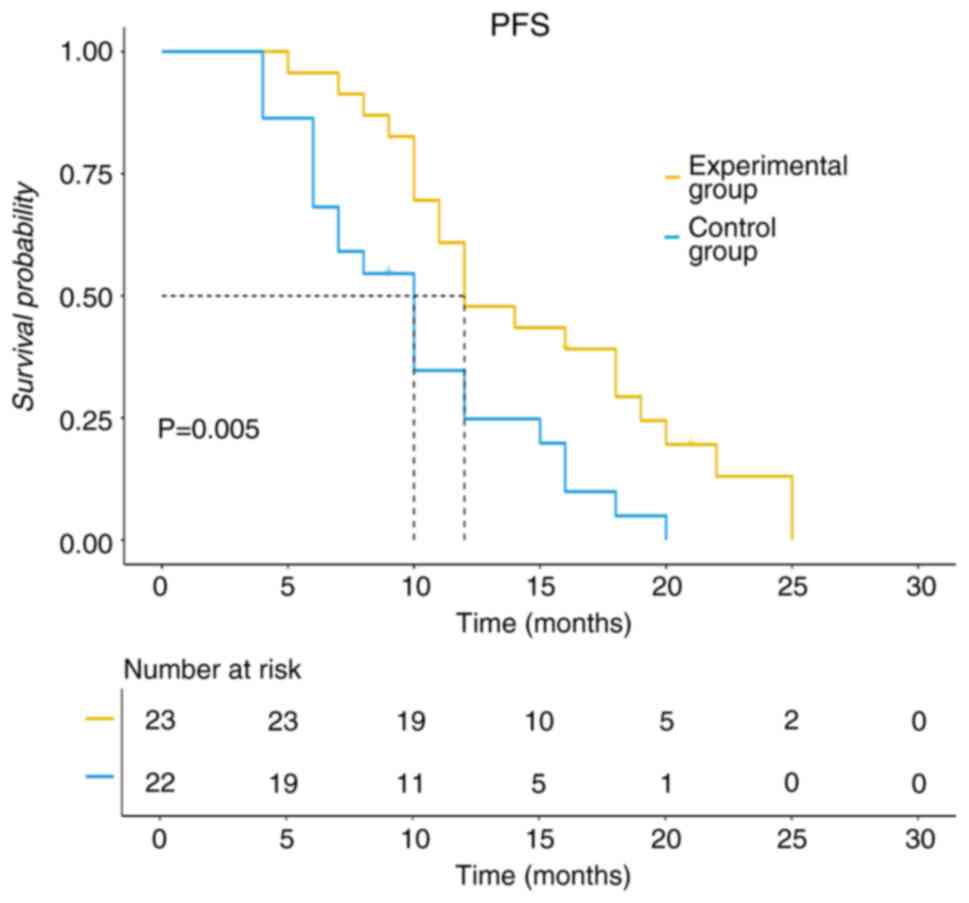

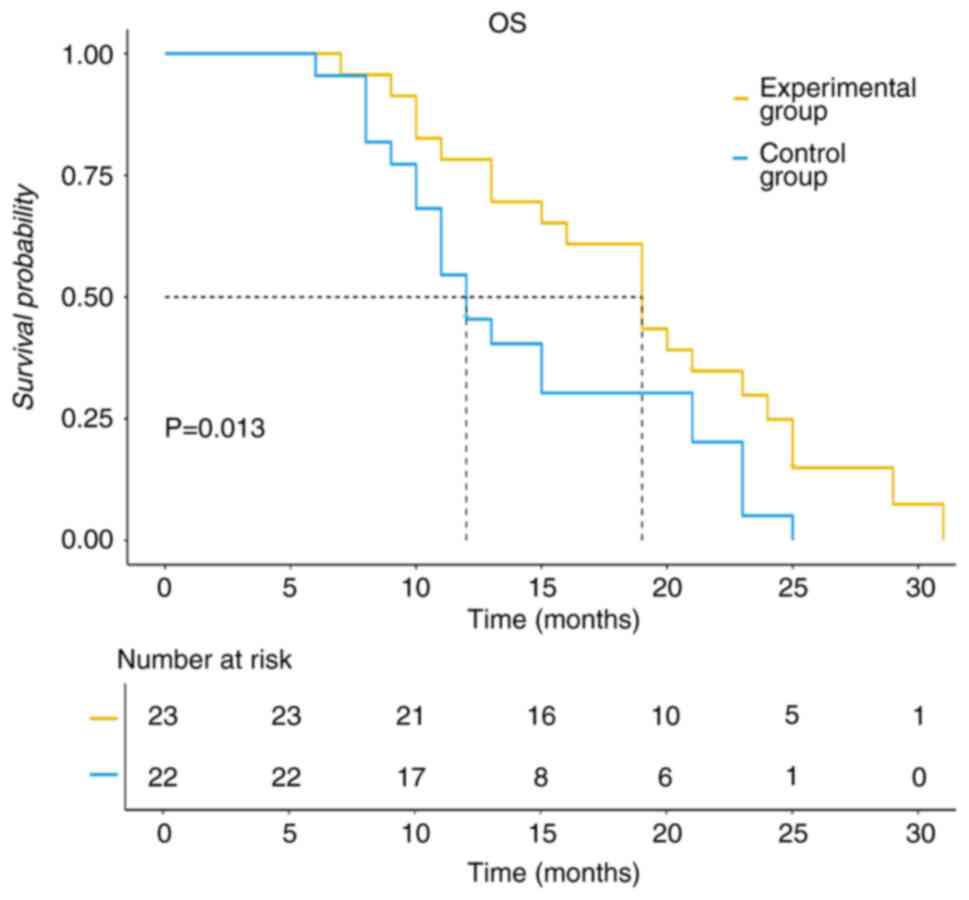

efficacy (Table SI). The median

PFS for the experimental group was 12 months, whilst for the

control group, it was 10 months (P<0.05; Fig. 3). The median OS for the experimental

group was 19 months, compared with 12 months for the control group

(P<0.05; Fig. 4). The cutoff

value for the maximum tumor diameter was determined to be 53 mm

using the surv_cutpoint function in R. Univariate analysis of OS

and PFS demonstrated that both the treatment regimen and maximum

tumor diameter had a significant impact on patient outcomes.

According to the results of the univariate Cox regression analysis,

the factors influencing OS included the treatment regimen and the

maximum tumor diameter (Table

III). Furthermore, multivariable Cox regression analysis with

forward stepwise selection (Forward LR) indicated that, after

controlling for tumor size, patients receiving the control regimen

had a 2.291-fold higher risk of death than those in the test group

[95% confidence interval (CI), 1.194–4.396]. Similarly, patients

with tumors of >53 mm had a 2.723-fold higher risk of death than

those with tumors of ≤53 mm (95% CI, 1.416–5.238) (Table IV). Moreover, univariate Cox

regression analysis revealed that both the treatment regimen and

tumor size were significant factors influencing PFS (Table V). Multivariable analysis confirmed

these findings, demonstrating that after adjusting for tumor size,

patients in the control group had a 2.567-fold higher recurrence

risk compared with those in the test group (95% CI, 1.332–4.949).

Additionally, patients with tumors of >53 mm had a 2.440-fold

higher recurrence risk than those with smaller tumors (95% CI,

1.276–4.665) (Table VI). In

summary, the combined univariate and multivariable analyses

indicate that the experimental therapy achieved superior PFS and OS

outcomes compared with the control regimen, and it was more

effective in delaying disease recurrence [HR (PFS)=2.567 and HR

(OS)=2.291].

| Table III.Univariate Cox analysis of different

characteristics based on overall survival. |

Table III.

Univariate Cox analysis of different

characteristics based on overall survival.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 95.0% CI for

HR |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Age (>60 vs. ≤60

years) | 0.298 | 0.358 | 0.692 | 0.405 | 1.347 | 0.668 | 2.716 |

| Sex (Female vs.

male) | 0.191 | 0.316 | 0.364 | 0.546 | 1.210 | 0.651 | 2.249 |

| Group (Control vs.

test) | 0.654 | 0.324 | 4.081 | 0.043 | 1.924 | 1.020 | 3.631 |

| ECOG

PSa |

|

| 0.375 | 0.829 |

|

|

|

| 0 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 0.294 | 0.736 | 0.159 | 0.690 | 1.341 | 0.317 | 5.672 |

| 2 | 0.110 | 0.774 | 0.020 | 0.887 | 1.117 | 0.245 | 5.089 |

| Pathological type

(SCC vs. AC) | 0.255 | 0.322 | 0.629 | 0.428 | 1.291 | 0.687 | 2.427 |

| TNM stage (IVA vs.

IIIB) | 0.161 | 0.314 | 0.263 | 0.608 | 1.175 | 0.635 | 2.175 |

| Maximum tumor

diameter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (>53 vs. ≤53

mm) | 0.849 | 0.324 | 6.853 | 0.009 | 2.336 | 1.238 | 4.410 |

| Table IV.Multivariate Cox analysis of

different characteristics based on overall survival. |

Table IV.

Multivariate Cox analysis of

different characteristics based on overall survival.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 95.0% CI for

HR |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Group (Control vs.

test) | 0.829 | 0.333 | 6.212 | 0.013 | 2.291 | 1.194 | 4.396 |

| Maximum tumor

diameter | 1.002 | 0.334 | 9.011 | 0.003 | 2.723 | 1.416 | 5.238 |

| (>53 vs. ≤53

mm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table V.Univariate Cox analysis of different

characteristics based on progression-free survival. |

Table V.

Univariate Cox analysis of different

characteristics based on progression-free survival.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 95.0% CI for

HR |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Age (>60 vs. ≤60

years) | 0.228 | 0.355 | 0.410 | 0.522 | 1.256 | 0.626 | 2.519 |

| Sex (Female vs.

male) | 0.276 | 0.314 | 0.775 | 0.379 | 1.318 | 0.712 | 2.439 |

| Group (Control vs.

test) | 0.819 | 0.329 | 6.206 | 0.013 | 2.269 | 1.191 | 4.322 |

| ECOG

PSa |

|

| 0.129 | 0.938 |

|

|

|

| 0 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 0.247 | 0.736 | 0.113 | 0.737 | 1.281 | 0.303 | 5.420 |

| 2 | 0.188 | 0.770 | 0.060 | 0.807 | 1.207 | 0.267 | 5.455 |

| Pathological type

(SCC vs. AC) | 0.403 | 0.323 | 1.562 | 0.211 | 1.497 | 0.795 | 2.818 |

| TNM stage (IVA vs.

IIIB) | 0.222 | 0.312 | 0.508 | 0.476 | 1.249 | 0.678 | 2.302 |

| Maximum tumor

diameter | 0.763 | 0.325 | 5.511 | 0.019 | 2.146 | 1.134 | 4.059 |

| (>53 vs. ≤53

mm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table VI.Multivariate Cox analysis of

different characteristics based on progression-free survival. |

Table VI.

Multivariate Cox analysis of

different characteristics based on progression-free survival.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 95.0% CI for

HR |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Group (Control vs.

test) | 0.943 | 0.335 | 7.929 | 0.005 | 2.567 | 1.332 | 4.949 |

| Maximum tumor

diameter | 0.892 | 0.331 | 7.273 | 0.007 | 2.440 | 1.276 | 4.665 |

| (>53 vs. ≤53

mm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adverse events

No severe adverse events, such as treatment-related

death, unintended embolism or grade ≥3 hematologic toxicity,

occurred in either group. Common adverse events, including

pneumothorax, hemoptysis, fever, chest pain and nausea, all

resolved with symptomatic treatment. Furthermore, the incidence of

adverse events did not significantly differ between the two groups

(Table VII).

| Table VII.Adverse events. |

Table VII.

Adverse events.

| Adverse event | Test group

(n=23) | Control group

(n=22) | P-value |

|---|

| Pneumothorax | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13.6) | 0.647 |

| Hemoptysis | 3 (13.0) | 3 (13.7) | 1.000 |

| Chest pain | 6 (26.1) | 5 (22.7) | 0.756 |

| Fever | 5 (21.7) | 3 (13.6) | 0.594 |

| Nausea | 2 (8.7) | 2 (9.1) | 1.000 |

Discussion

Treating advanced refractory NSCLC is challenging.

Local therapies such as BACE and iodine-125 seed implantation have

received considerable attention and are increasingly applied in

clinical practice and research (19). Therefore, the present study aimed to

evaluate the efficacy and safety of 8Spheres microsphere

embolization combined with iodine-125 seed implantation for

advanced refractory lung cancer, and compare it with iodine-125

seed implantation alone. The results indicate that the combination

therapy outperformed iodine-125 seed implantation alone in terms of

local tumor control, OS and PFS, suggesting the potential benefits

of this combined approach for patients with advanced refractory

lung cancer.

In the present study, the ORR, DCR, median PFS and

median OS were significantly higher in the test group compared with

that in the control group (P<0.05). Furthermore, the test group

demonstrated improved efficacy in delaying disease recurrence [HR

(PFS)=2.567 and HR (OS)=2.291].

Whilst certain patients experienced mild adverse

effects, such as chest pain and fever, these were managed

effectively with symptomatic treatment, and no serious

complications occurred. This highlights the therapeutic advantage

of 8Spheres microspheres, which are considered to be effective due

to their role as a vascular embolic agent. The optimal cutoff value

for the maximum tumor diameter, determined using the surv_cutpoint

function in R, was revealed to be 53 mm. Patients with tumors

exceeding this size had a worse survival prognosis than those with

tumors less than this size. Therefore, this cutoff value may aid in

stratifying prognostic risk and guide treatment planning in

clinical practice. In summary, tumor size in advanced refractory

lung cancer appears to significantly influence patient

prognosis.

The efficacy of iodine-125 seed therapy has been

well-established in prostate cancer and spinal metastases (20,21).

In a study by Cheng et al (22), six patients with NSCLC received

iodine-125 seed implantation. A total of five patients achieved CR,

and one achieved PR 1 month after implantation, with an ORR of

100%, a median OS of 26 months, and a median PFS of 12 months. In

another study by Sui et al (23), three patients with advanced NSCLC

treated with iodine-125 seed brachytherapy and anti-programmed cell

death protein-1 antibodies achieved CR or PR. Moreover, compared

with conventional whole-body radiotherapy, iodine-125 seed

implantation reduces radiation exposure to surrounding tissues,

minimizes treatment-related side effects, and is suitable for

inoperable patients or those unable to tolerate systemic

chemotherapy (24). However,

iodine-125 seed therapy has limitations, particularly in addressing

the complex tumor-blood supply system.

BACE has also been assessed for treating advanced

lung cancer (25). In a study by

Zhu et al (26), BACE

combined with apatinib improved outcomes in patients with lung

cancer. Among the 47 patients who underwent the BACE procedure, the

observation group had a median PFS of 322 days, compared with 209

days in the control group (P<0.05), with 1-year survival rates

of 76.19 and 46.15%, respectively (P<0.05). However, traditional

embolization materials such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles

and gelatin sponge particles have limitations. PVA particles may

cause incomplete embolization due to uneven size distribution,

whilst gelatin sponge particles, being short-acting embolic agents,

may result in tumor recurrence or complications (27,28).

8Sphere microspheres are a novel type of embolic

material made from a macromolecular cross-linked polymer, with PVA

as the main chain. These microspheres have a regular spherical

shape and the ability to compress, which allows them to travel

further within blood vessels. These properties enable precise

distribution in the blood supply artery of a tumor during

embolization, resulting in terminal embolization with a stable and

predictable effect (11). In a

study by Zhang et al (29),

15 patients with uterine fibroids underwent uterine artery

embolization using 8Spheres microspheres, with no serious adverse

effects. At 6 months post-surgery, the volumes of the uterus and

dominant smooth muscle tumors notably decreased from 340.0±35.8 and

100.6±24.3 cm3, respectively (baseline) to 266.6±30.9

and 56.1±17.3 cm3. These results indicate the efficacy

and safety of 8Spheres microspheres in solid tumor embolization.

Furthermore, 8Spheres microsphere embolization is also associated

with minimal adverse effects. In a study by Zhou et al

(30), partial splenic artery

embolization using 8Spheres microspheres in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma and hypersplenism not only achieved

permanent vascular embolization but also markedly reduced

inflammatory responses, resulting in a lower incidence of fever and

pain. The enhanced therapeutic efficacy of the combined treatment

is likely due to multiple biological mechanisms. Vascular

embolization with 8Spheres microspheres induces tumor hypoxia and

the simultaneous inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and

invasion (29). In a study by Chao

et al (31), TACE was

reported to be associated with the modulation of serum angiogenic,

inflammatory and cell growth cytokines in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Additionally, the ischemic and

hypoxic environment created by embolization may alter the immune

microenvironment of the tumor, potentially enhancing the immune

response against the tumor (32).

In a previous study, hepatic artery embolization (HAE) was reported

to enhance intratumoral and peritumoral programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) expression in a rat HCC model. The hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α pathway is a possible mechanism underlying increased

intratumoral PD-L1 expression after HAE (32). Moreover, in a study by Kang et

al (33), the iodine-125 seed

promoted the apoptosis of cholangiocarcinoma cells and induced the

activation of the ROS/p53 pathway in a dose-dependent manner. The

combination of 8Spheres microsphere vascular embolization of the

tumor blood supply and induction of tumor hypoxia, and iodine-125

seed implantation for radiation damage to the tumor, enhanced the

therapeutic effect on the tumor. However, further studies are

required to elucidate these mechanisms in more detail. In a

single-arm pilot study by Chen et al (34), embosphere microsphere embolization

combined with iodine-125 seeds was used to treat patients with

locally advanced stage III NSCLC after radiotherapy failure. Among

the 28 patients, the 6-month ORR and DCR were 71.42 and 92.86%,

respectively, with no serious complications observed during

follow-up. The median PFS was 8 months (95% CI, 7.3–8.8 months). In

the present study, the ORR, DCR and median PFS in the combination

therapy group were higher than those reported by Chen et al.

We hypothesize that the improved treatment efficacy in the present

study was associated with the superior size distribution, enhanced

spherical stability and improved retention characteristics of the

8Spheres microspheres.

Compared with standard-of-care treatments, such as

immunotherapy-based regimens and radiation therapy, the combined

treatment of 8Spheres microsphere embolization and iodine-125 seed

implantation offers several advantages. The minimally invasive

nature of the procedure and the enhanced therapeutic effect due to

the synergistic action of the two modalities make it a promising

option for patients with advanced refractory NSCLC. However, the

combined treatment may not be suitable for all patients, and

further studies are needed to determine the optimal indications and

patient selection criteria.

The present study has several limitations. First, it

was a retrospective analysis with a small sample size and a

relatively short follow-up period, which could introduce selection

bias. To more comprehensively evaluate the long-term efficacy and

safety of the treatment regimen, larger-scale prospective

randomized controlled trials are warranted. In future prospective

studies, it is recommended that propensity score matching be

incorporated. This approach can help adjust for potential

confounders and further validate the findings obtained in the

current study, thereby providing more robust and reliable evidence

for clinical practice. Moreover, despite all patients receiving the

same treatment, individual variations in response could affect

efficacy and safety. Whilst the present study reports follow-up

data up to June 2024, long-term survival outcomes (such as 3–5

years follow-up) are crucial for evaluating the true efficacy of

the treatment. Future studies should aim to provide long-term data

on survival trends, late-onset adverse events and patterns of

disease recurrence. This will further validate the clinical

benefits of the combined treatment. In addition, future research

should focus on more precise patient stratification and

individualized treatment regimens so as to offer improved options

for patients with refractory NSCLC. The current study used the

sequence of seed implantation followed by embolization; however,

future studies should evaluate the clinical outcomes of pre-seed

implantation embolization. This modification may enhance tumor

hypoxia and improve the efficacy of iodine-125 radiotherapy.

Furthermore, genetic alterations (such as EGFR, ALK and KRAS

mutations) were not systematically recorded in patient medical

records, limiting the ability to stratify outcomes by molecular

profiles. Future prospective studies should integrate comprehensive

genomic profiling to refine prognostic models and identify

biomarkers predictive of treatment response. Finally, although

histological subtypes (adenocarcinoma vs. squamous carcinoma) and

baseline ECOG performance status were balanced between groups,

subgroup analyses stratified by these factors were not performed

due to the small sample size. More extensive studies should explore

whether treatment efficacy differs across histological subtypes or

patient functional status.

In conclusion, the combination of 8Spheres

microsphere embolization and iodine-125 seed implantation presents

a promising treatment option for patients with advanced refractory

NSCLC. The procedure is straightforward, minimally invasive and

safe, making it a promising option for clinical application.

Furthermore, this approach significantly enhances therapeutic

efficacy, extends survival and is minimally invasive, meaning that

it well-suited for clinical use. However, further research is

required to evaluate its long-term effects and explore optimized

treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LR and HP conceived and designed this study. LR, LJ

and YL participated in data collection and data curation

(organizing and maintaining data). LJ, YL and HP analyzed the data.

LR, LJ and HP drafted the manuscript and all authors reviewed it.

YL and HP confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing

Medical University (approval no. K2023-470). The requirement for

informed consent for participation was waived due to the

retrospective nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CR

|

complete remission

|

|

DCR

|

disease control rate

|

|

DSA

|

digital subtraction angiography

|

|

ECOG

|

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PD

|

progressive disease

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

PR

|

partial remission

|

|

RECIST

|

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid

Tumors

|

|

SD

|

stable disease

|

References

|

1

|

Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF

and Heist RS: Lung cancer. Lancet. 398:535–554. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Miller M and Hanna N: Advances in systemic

therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ. 9:n23632021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Meyer ML, Fitzgerald BG, Paz-Ares L,

Cappuzzo F, Jänne PA, Peters S and Hirsch FR: New promises and

challenges in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.

Lancet. 404:803–822. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Remon J, Soria JC and Peters S; ESMO

Guidelines Committee. Electronic address, : simpleclinicalguidelines@esmo.org:

Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: An update of

the ESMO clinical practice guidelines focusing on diagnosis,

staging, systemic and local therapy. Ann Oncol. 32:1637–1642. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhao YW, Liu S, Qin H, Sun JB, Su M, Yu

GJ, Zhou J, Gao F, Wang RY, Zhao T and Zhao GS: Efficacy and safety

of CalliSpheres drug-eluting beads for bronchial arterial

chemoembolization for refractory non-small-cell lung cancer and its

impact on quality of life: A multicenter prospective study. Front

Oncol. 13:11109172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zha B, Zhang Y, Yang R and Kamili M:

Efficacy and safety of anlotinib as a third-line treatment of

advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Oncol Lett. 24:2292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kou F, Gao S, Liu S, Wang X, Chen H, Zhu

X, Guo J, Zhang X, Feng A and Liu B: Preliminary clinical efficacy

of iodine-125 seed implantation for the treatment of advanced

malignant lung tumors. J Cancer Res Ther. 15:1567–1573. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

He G, Yang K, Zhang X, Pan J, Han A, Gao

Z, Li Y and Wang W: Bronchial artery chemoembolization with

drug-eluting beads versus bronchial artery infusion followed by

polyvinyl alcohol particles embolization for advanced squamous cell

lung cancer: A retrospective study. Eur J Radiol. 161:1107472023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Du L and Morgensztern D: Chemotherapy for

advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer J. 21:366–370.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Komada T, Suzuki K, Mizuno T, Ebata T,

Matsushima M, Naganawa S and Nagino M: Efficacy of percutaneous

transhepatic portal vein embolization using gelatin sponge

particles and metal coils. Acta Radiol Open.

7:20584601187696872018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lu H, Zheng C, Liang B and Xiong B:

Quantitative splenic embolization possible: Application of 8Spheres

conformal microspheres in partial splenic embolization (PSE). BMC

Gastroenterol. 21:4072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Detterbeck FC, Chansky K, Groome P,

Bolejack V, Crowley J, Shemanski L, Kennedy C, Krasnik M, Peake M,

Rami-Porta R, et al: The IASLC lung cancer staging project:

Methodology and validation used in the development of proposals for

revision of the stage classification of NSCLC in the forthcoming

(eighth) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac

Oncol. 11:1433–1446. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Asano R, Kajimoto K, Oka T, Sugiura R,

Okada H, Kamishima K, Hirata T and Sato N; investigators of the

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Syndromes (ATTEND) registry, :

Association of New York Heart Association functional class IV

symptoms at admission and clinical features with outcomes in

patients hospitalized for acute heart failure syndromes. Int J

Cardiol. 230:585–591. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley

W, Bauman J, Chirieac LR, D'Amico TA, DeCamp MM, Dilling TJ,

Dobelbower M, et al: Non-small cell lung cancer, version 5.2017,

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc

Netw. 15:504–535. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Atkinson TM, Ryan SJ, Bennett AV, Stover

AM, Saracino RM, Rogak LJ, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, Li Y and Basch

E: The association between clinician-based common terminology

criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) and patient-reported outcomes

(PRO): A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 24:3669–3676.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Fan Z, Yang LC, Chen YQ, Wan WQ, Zhou DH,

Mai HR, Li WL, Yang LH, Lan HK, Chen HQ, et al: Prognostic

significance of MRD and its correlation with arsenic concentration

in pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia: A retrospective study by

SCCLG-APL group. Ther Adv Hematol. 16:204062072413117742025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chaft JE, Shyr Y, Sepesi B and Forde PM:

Preoperative and postoperative systemic therapy for operable

non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 40:546–555. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chin J, Rumble RB, Kollmeier M, Heath E,

Efstathiou J, Dorff T, Berman B, Feifer A, Jacques A and Loblaw DA:

Brachytherapy for patients with prostate cancer: American society

of clinical oncology/cancer care ontario joint guideline update. J

Clin Oncol. 35:1737–1743. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sharma R, Sagoo NS, Haider AS, Sharma N,

Haider M, Sharma IK, Igbinigie M, Aya KL, Aoun SG and Vira S:

Iodine-125 radioactive seed brachytherapy as a treatment for spine

and bone metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg

Oncol. 38:1016182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cheng G, Wang Y, Dong D, Zhang W, Wang L

and Wan Z: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of 125I seed

implantation in SCLC as second line therapy. Medicine (Baltimore).

101:e292512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sui A, Song H, Yu H, Zhang H, Hu Q, Lei Y,

Zhang L and Wang J: Clinical application of iodine-125 seed

brachytherapy combined with anti-PD-1 antibodies in the treatment

of lung cancer. Clin Ther. 42:1612–1616. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li Z, Hu Z, Xiong X and Song X: A review

of the efficacy and safety of iodine-125 seed implantation for lung

cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 41:1008442024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ma X, Zheng D, Zhang J, Dong Y, Li L, Jie

B and Jiang S: Clinical outcomes of vinorelbine loading

CalliSpheres beads in the treatment of previously treated advanced

lung cancer with progressive refractory obstructive atelectasis.

Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 10:10882742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhu J, Xu X, Chen Y, Wang Q, Yue Q, Lei K,

Jia Y, Xiao G and Xu G: Bronchial artery chemoembolization with

apatinib for treatment of central lung squamous cell carcinoma. J

Cancer Res Ther. 18:1432–1435. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Luz JHM, Gomes FV, Coimbra E, Costa NV and

Bilhim T: Preoperative portal vein embolization in hepatic surgery:

A review about the embolic materials and their effects on liver

regeneration and outcome. Radiol Res Pract.

2020:92958522020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu J, Shi D, Li L, Cao L, Liu J, He J and

Liang Z: Clinical study on the treatment of benign prostatic

hyperplasia by embolization of prostate artery based on embosphere

microspheres and gelatin sponge granules. J Healthc Eng.

2022:14240212022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhang Y, Xu Y, Zhang X, Zheng B, Hu W,

Yuan G and Si G: 8Spheres conformal microspheres as embolic agents

for symptomatic uterine leiomyoma therapy in uterine artery

embolization (UAE): A prospective clinical trial. Medicine

(Baltimore). 102:e330992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhou J, Feng Z, Liu S, Li X, Liu Y, Gao F,

Shen J, Zhang YW, Zhao GS and Zhang M: Simultaneous CSM-TACE with

CalliSpheres® and partial splenic embolization using

8spheres® for hepatocellular carcinoma with

hypersplenism: Early prospective multicenter clinical outcome.

Front Oncol. 12:9985002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chao Y, Wu CY, Kuo CY, Wang JP, Luo JC,

Kao CH, Lee RC, Lee WP and Li CP: Cytokines are associated with

postembolization fever and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma

patients receiving transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Hepatol Int. 7:883–892. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Takaki H, Hirata Y, Ueshima E, Kodama H,

Matsumoto S, Wada R, Suzuki H, Nakasho K and Yamakado K: Hepatic

artery embolization enhances expression of programmed cell death 1

ligand 1 in an orthotopic rat hepatocellular carcinoma model: In

vivo and in vitro experimentation. J Vasc Interv Radiol.

31:1475–1482.e2. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kang F, Wu J, Hong L, Zhang P and Song J:

Iodine-125 seed inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of

cholangiocarcinoma cells by inducing the ROS/p53 axis. Funct Integr

Genomics. 24:1142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen C, Wang W, Yu Z, Tian S, Li Y and

Wang Y: Combination of computed tomography-guided iodine-125

brachytherapy and bronchial arterial chemoembolization for locally

advanced stage III non-small cell lung cancer after failure of

concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Lung Cancer. 146:290–296. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|