Introduction

Lung cancer is a globally prevalent malignant tumor

and one of the most common causes of cancer-associated mortality.

Lung cancer is classified into two main types: Non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer, with NSCLC comprising

~85% of all cases (1). Among the

different subtypes of NSCLC, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) has the

highest incidence and prevalence. However, despite significant

advances in surgery, chemotherapy and targeted therapy, the

prognosis for patients with LUAD remains poor (2). Therefore, it is particularly urgent to

develop reasonable treatment strategies to improve the therapeutic

effect of lung adenocarcinoma. The invasion and metastasis of

tumors is a complex regulatory process influenced by multiple

factors, such as the activation of oncogenes, the inactivation of

tumor suppressor genes and mutations in signaling pathways

(3,4). Discovering molecular biological

markers associated with lung adenocarcinoma not only helps to

deepen the understanding of the disease, but also may provide

guidance for the future diagnosis and treatment of lung

adenocarcinoma.

The coagulation system is an inherent defense

mechanism of the human body, which can be activated through the

tissue factor pathway (extrinsic pathway) or the intrinsic pathway.

Tumor cells express procoagulant factors, including tissue factor,

which triggers the coagulation cascade and ultimately leads to the

generation of thrombin (5). The

activation of this coagulation and fibrinolysis system promotes the

invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of malignant tumor cells

(6). Patients with malignant tumors

often exhibit a hypercoagulable state, and have a higher risk of

cancer-related thrombosis than healthy individuals (7), including deep vein thrombosis and

pulmonary thromboembolism, which significantly reduces the survival

rate and prognosis of patients (8).

A large amount of experimental evidence supports that patients with

malignant tumors often remain in a state of chronic

hypercoagulability and hyperfibrinolysis, which is the main cause

of the increased risk of thrombosis and bleeding (6). In particular, the prognosis of

patients with cancer is closely related to the effectiveness of

anticoagulant therapy. Specifically, patients with a better

prognosis have an extended survival period after receiving

anticoagulant treatment (9). The

association between biomarkers related to coagulation disorders and

the prognosis of various cancer types has previously been reported

(10). The role of the coagulation

cascade in the formation of the tumor microenvironment (TME) has

also been emphasized in research (11). Although the associations between the

coagulation system and multiple types of tumors, such as cutaneous

melanoma (12), gastric cancer

(13) and hepatocellular carcinoma

(14), have been confirmed, the

precise role of the coagulation system in LUAD has yet to be

elucidated.

The present study aimed to develop a specific

coagulation-related gene (CRG) prognostic model for LUAD, and to

offer novel insights and approaches for the prognostic assessment,

immune analysis and therapy of this disease. This model is intended

to facilitate the investigation of tumor prognosis, immune cell

infiltration, genetic mutations, tumor mutation burden (TMB) and

drug responses.

Materials and methods

Data collection

LUAD transcriptome data and associated clinical

information were sourced from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

official data portal (https://gdc portal.nci.nih.gov/). The dataset included

582 samples, comprising 524 tumor samples and 58 normal tissue

samples. Following initial data screening, samples with missing or

zero prognostic information were excluded, resulting in the

selection of 507 tumor samples and 58 normal tissue samples for

detailed analysis.

Acquisition of CRGs in LUAD

A total of 138 CRGs were extracted from the

Molecular Signatures database (MsigDB; http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) (Table SI). Differentially expressed genes

(DEGs) were identified using the limma package (version 3.54.2) in

R (https://cran.r-project.org) with gene

set normalization applied. The screening criteria were set to an

absolute value of the log2 fold change

(|log2FC|)>1.5 and adjusted P<0.05. The DEGs were

identified by comparing normal lung tissue samples with LUAD tissue

samples from TCGA database. The DEGs were visualized using the

ggplot2 package (version 3.4.2) and plotted as volcano plots.

Comparative analysis was performed to identify coagulation-related

DEGs specific to LUAD.

Enrichment analysis

Following the identification of differentially

expressed CRGs, enrichment analysis was performed using the

clusterProfiler package (version 4.6.2). The analyses included

three Gene Ontology (GO) categories, namely biological process

(BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF), as well

as Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis.

The aim of performing these analyses was to elucidate the molecular

mechanisms associated with CRGs. The criteria for statistical

significance were P<0.05 and q<0.05 in both the GO and KEGG

analyses. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was

conducted to assess model genes in high- and low-risk groups based

on risk scores, with statistical significance defined as P<0.05

and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05.

Establishment and validation of the

CRG risk model

The survival package (version 3.5.5) was used to

identify CRGs significantly associated with overall survival (OS;

P<0.05). Univariate Cox regression analyses were performed to

calculate the hazard ratio (HR). The data from TCGA were randomly

divided into two essentially equal-sized groups: Training set

(n=254) and test set (n=253). Least absolute shrinkage and

selection operator (LASSO) regression analyses were then conducted

using the glmnet package (version 4.1.7) to refine the gene

selection. A risk model was developed using the training set data

and validated using the overall and test set data. The risk score

formula constructed was as follows:

The coefficient Coefi and expression

level Expri represent the Cox regression coefficient and

normalized expression level for each mRNA, respectively. Based on

the risk score, samples were divided into high- and low-risk

groups, with this stratification applied to the overall, test and

training sets. To compare OS rates, Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were

generated using the survival package and survminer package (version

0.4.9). An analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) was also

performed. In addition, gene expression differences between the

high- and low-risk groups were visualized using the pheatmap

package (version 1.0.12) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curves were constructed using the survival package, survminer

package (version 0.4.9) and timeROC package (version 0.4) to

evaluate the accuracy of the prognostic model and the 1-, 3- and

5-year survival rates. The protein expression of the four genes

included in the prognostic model was assessed in normal and LUAD

tissues using immunohistochemistry (IHC) data from the Human

Protein Atlas (HPA; http://www.proteinatlas.org/). Finally, principal

component analysis (PCA) was performed using the ggplot2 package in

R to analyze the distribution differences between high- and

low-risk groups, thereby assessing the accuracy and applicability

of the model.

Construction of nomogram

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were performed using the survival package (version 3.5.5),

incorporating age, sex, tumor stage and TNM staging to compute risk

scores as independent risk factors. Subsequently, a nomogram was

constructed using the rms package (version 6.7.0), survcomp package

(version 1.48.0), regplot package (version 1.1) and survival

package. The accuracy of the model was further validated using

calibration curves.

Immune and TMB analyses

Initially, immune, ESTIMATE and stromal scoring was

conducted for high- and low-risk groups of LUAD using the limma

package and estimate package (version 1.0.13). CIBERSORT analysis

was then performed using the limma package, with immune cell

differences between the two groups visualized using the limma,

reshape2 package (version 1.4.4) and ggpubr package (version

0.6.0). To assess immune function differences between the two

groups, the limma GSVA package (version 1.46.0) and GSEABase

package (version 1.60.0) were used, with results visualized using

the reshape2 and ggpubr packages. Additionally, gene mutation

information was obtained from TCGA, and the mutation frequencies of

the most prevalent genes in the high- and low-risk groups were

visualized using the maftools package (version 2.14.0). TMB was

then compared between the two groups using the ggpubr and limma

packages. The analysis was performed using ‘futime’ as the time

variable and ‘fustat’ as the event variable. The variable TMB was

used to determine the cut off value; patients with a TMB value

lower than the cut off were assigned to the low TMB group, while

those with a TMB value higher than the cut off were assigned to the

high TMB group. The survival rates of these two groups are compared

to evaluate their association with risk scores. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate statistical significance.

Tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion

(TIDE) score and drug sensitivity analysis

The limma and ggpubr packages were used to visualize

differences in TIDE scores between the high- and low-risk groups.

Subsequently, drug sensitivity analysis was performed on the two

groups using the limma package, oncoPredict package (version 0.2)

and parallel package (version 4.2.2). The results of the drug

sensitivity analysis were then visualized as half-maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50) values using the ggpubr

and ggplot2 packages.

Patients and specimens

Three pairs of LUAD samples and adjacent

non-cancerous tissues were collected from patients who underwent

curative resection between November 2024 and January 2025 at Jinan

Central Hospital (Jinan, China), including 2 female and 1 male

patient, aged between 50–70 years. All tissue samples were verified

by histopathological examination and stored in liquid nitrogen for

subsequent reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Diagnosed with

LUAD through pathological examination; ii) had not undergone any

form of tumor treatment prior to surgery; and iii) had a complete

clinicopathological record. The study excluded patients meeting the

following criteria: i) Age <18 or >80 years; ii) pregnant or

breastfeeding; iii) had autoimmune diseases or other types of

malignancies; or iv) had received any antitumor therapy. The study

protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinan Central

Hospital (20241120026). All procedures were conducted in accordance

with applicable guidelines and regulations. All patients signed the

informed consent form.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

The A549 human LUAD and BEAS-2B normal human lung

epithelial cell lines were obtained from Wuhan Pricella

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin, and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. The

medium was changed every 2 to 3 days. Total RNA was extracted from

the cells and tissues using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and reverse transcribed into cDNA

using a reverse transcription kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

The mRNA expression was quantified using RT-qPCR analysis using

10.0 µl SYBR™ Green (Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co.,

Ltd.), 0.5 µl primer, 2 µl cDNA and 7.0 µl

diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. The thermocycling conditions

were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed

by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30

sec. β-actin was used as an internal control. The mRNA expression

levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method and

normalized against the expression levels of β-actin (15). Each experiment was repeated three

times. The sequences of the primers used are listed in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences used for

quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used for

quantitative PCR.

| Genes | Forward

(5′-3′) | (5′-3′) |

|---|

| β-actin |

CCTTCCTGGGCATGGAGTC |

TGATCTTCATTGTGCTGGGTG |

| MMP10 |

GAGTTTGACCCCAATGCCAG |

TCTTCCCCCTATCTCGCCTA |

| CTSV |

TCAGGCAGATGATGGGTTGC |

GCCCAACAAGAACCACACTG |

| F2 |

CACGGCTACGGATGTGTTCT |

AGTTCGTACCCAGACCCTCAG |

| MMP1 |

TTGCCGACAGAGATGAAGTCC |

CGTGTAGCACATTCTGTCCCT |

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R

software (version 4.2.2) and GraphPad_Prism (version 8.0.2;

Dotmatics). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess whether the

data in the high- and low-risk groups followed a normal

distribution. The Mann-Whitney U test (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) was

used when comparing the two risk groups, as well as unpaired LUAD

and normal tissue from TCGA. Wilcoxon signed-rank analysis was used

to compare paired LUAD and normal tissues from TCGA. Differences

between paired primary tissues and between cell lines were analyzed

using paired and unpaired t-tests, respectively. The log-rank test

was employed to identify differences between KM curves. Univariate

and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to identify

prognostic risk factors associated with LUAD. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Identification of CRGs in patients

with LUAD

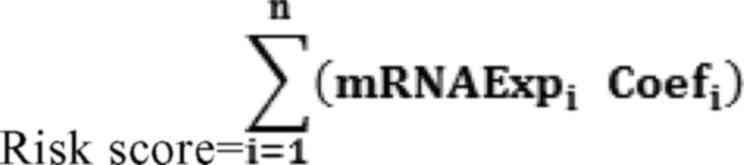

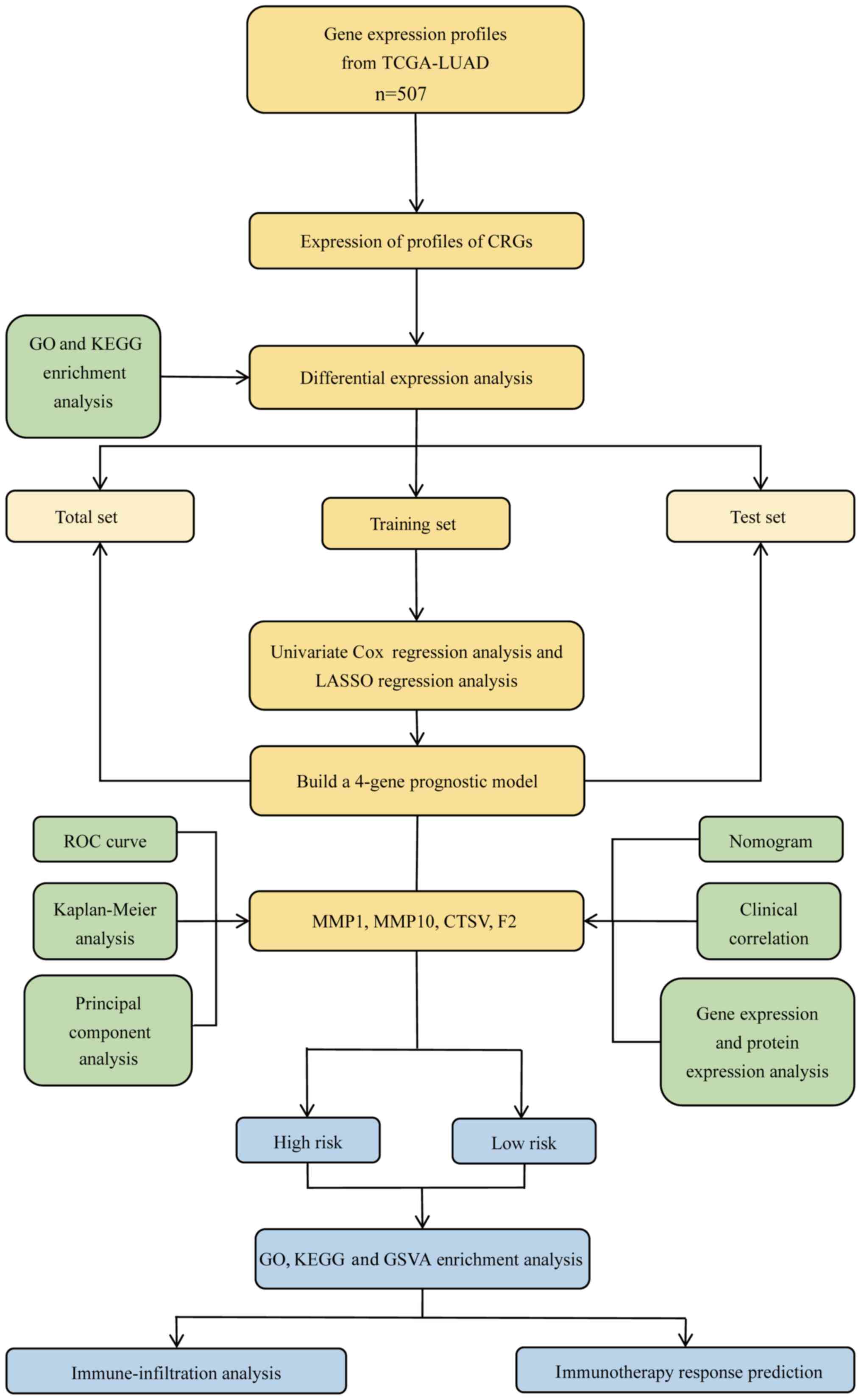

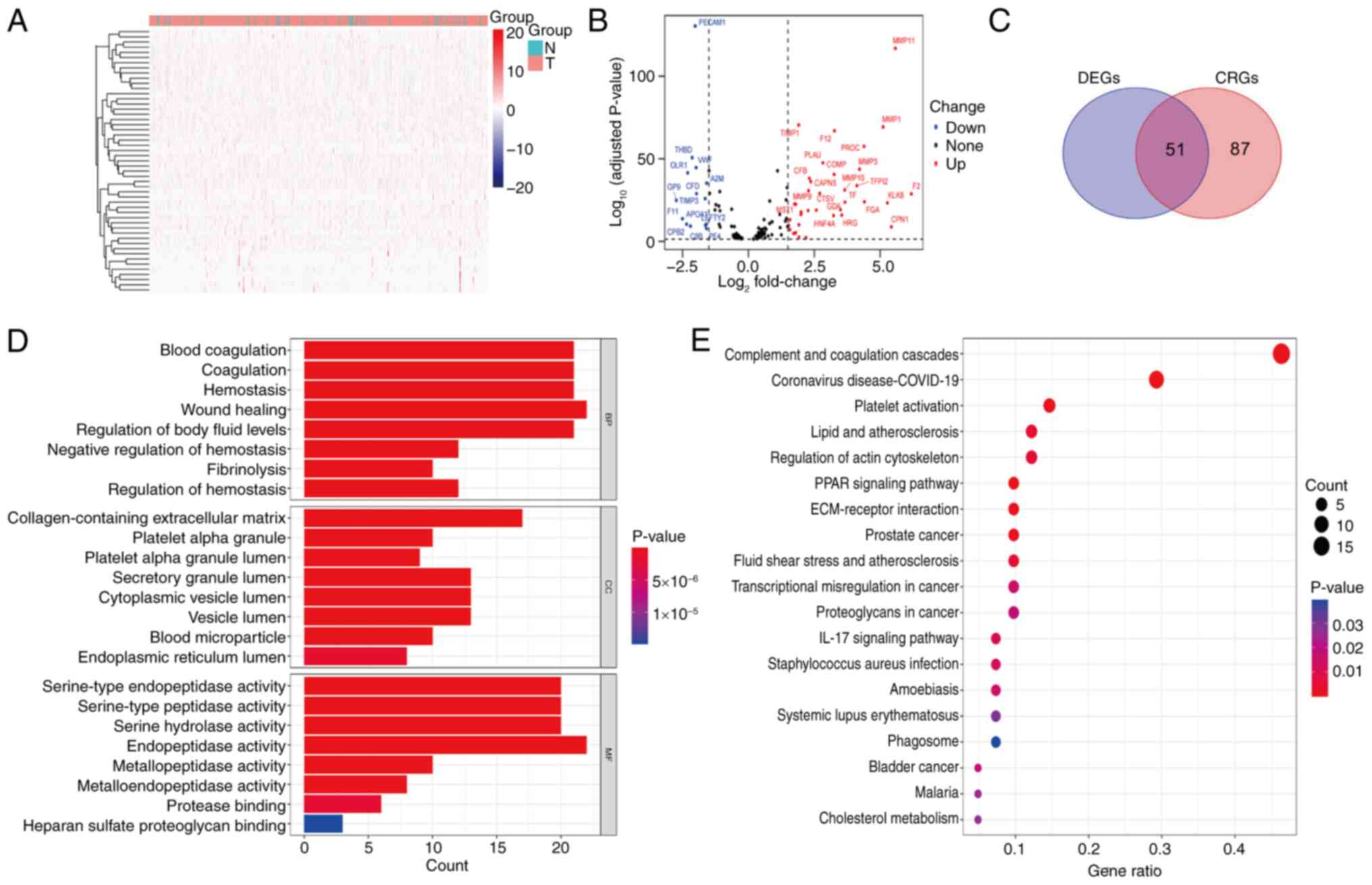

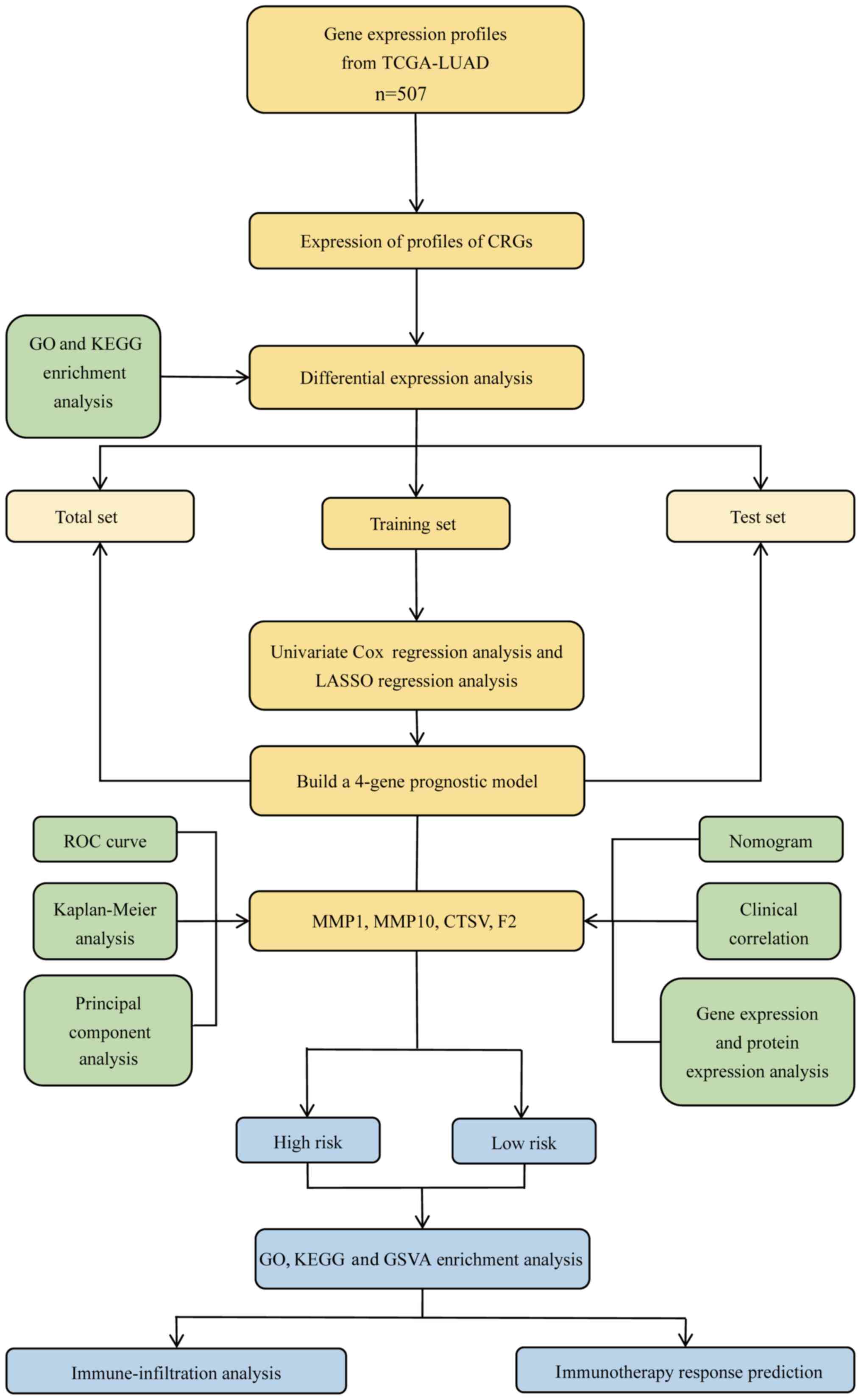

Fig. 1 provides an

overview of the workflow for the present study. Gene expression

data, clinical information and mutation data for patients with LUAD

were collected from TCGA. By comparing the expression of 138 known

CRGs between LUAD samples and adjacent normal tissue, 51

differentially expressed CRGs were identified (FDR <0.05, |log2

FC|>1.5), including 37 upregulated genes and 14 downregulated

genes. Heatmaps and volcano plots were subsequently generated to

visualize the expression patterns of these genes in normal and LUAD

tissues (Fig. 2A and B). Further

analysis verified that all 51 DEGs were associated with the

coagulation process (Fig. 2C).

| Figure 1.Methodology flow chart. TCGA, The

Cancer Genome Atlas; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; CRGs,

coagulation-related genes; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage

and selection operator; ROC, receiver operating characteristic;

MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; CTSV, cathepsin V; F2,

thrombin/coagulation factor II; GSVA, gene set variation

analysis. |

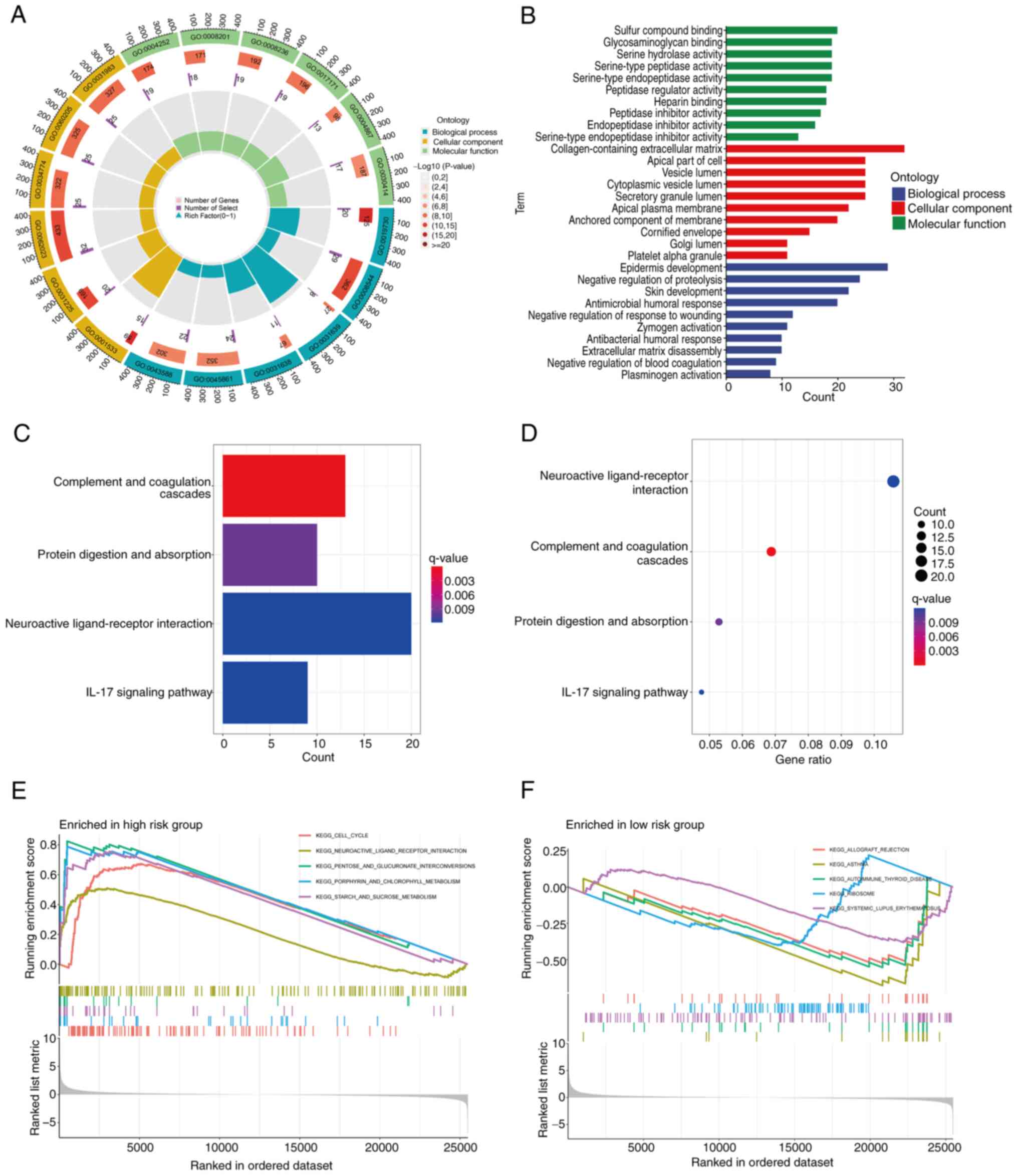

Enrichment analysis of CRGs

To explore the functions and potential mechanisms of

the 51 DEGs, GO analysis was performed. The results reveal a

significant enrichment of these CRGs in certain BPs, including

‘blood coagulation’, ‘coagulation’, ‘hemostasis’, ‘wound healing’

and ‘regulation of body fluid levels’. At the CC level, these genes

are predominantly enriched in ‘collagen-containing extracellular

matrix’, ‘secretory granule lumen’, ‘cytoplasmic vesicle lumen’ and

‘vesicle lumen’. In addition, MF analysis demonstrated that these

genes are closely associated with ‘serine-type endopeptidase

activity’, ‘serine-type peptidase activity’, ‘serine hydrolase

activity’ and ‘endopeptidase activity’ (Fig. 2D). KEGG analysis revealed that these

genes are significantly enriched in the ‘complement and coagulation

cascades’ pathway (Fig. 2E). These

findings reinforce the close association between coagulation

processes and the development and progression of LUAD.

Subsequently, a risk model based on the coagulation genes was

created, to further confirm the association between LUAD and

coagulation pathways.

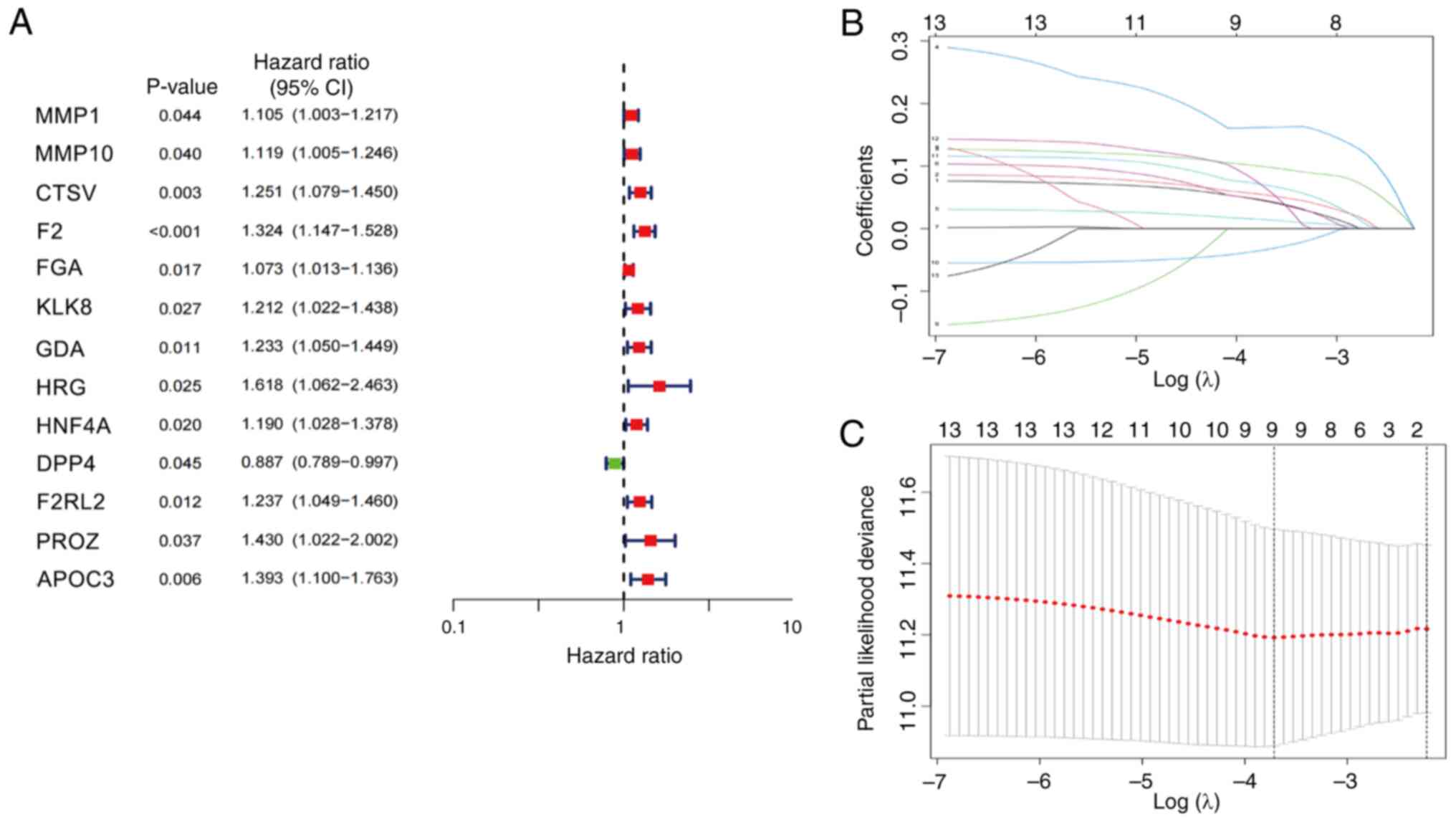

Construction of a four-gene risk model

associated with coagulation metabolism

As noted above, 51 DEGs were identified through

differential expression analysis. Subsequently, univariate Cox

regression analysis was performed, which revealed that 13 genes

were significantly associated with OS. Of these, matrix

metalloproteinase (MMP) 1 (HR, 1.105; P=0.044), MMP10 (HR, 1.119;

P=0.040), cathepsin V (CTSV; HR=1.251; P=0.003),

thrombin/coagulation factor II (F2; HR=1.324; P<0.001), FGA (HR,

1.073; P=0.017), KLK8 (HR, 1.212; P=0.027), GDA (HR, 1.233;

P=0.011), HRG (HR, 1.618; P=0.025), HNF4A (HR, 1.190; P=0.020),

F2RL2 (HR, 1.237; P=0.012), PROZ (HR, 1.430; P=0.037) and APOC3

(HR, 1.393; P=0.006) were classified as high-risk genes, while DPP4

(HR, 0.887; P=0.045) was classified as a low-risk gene (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, 507 eligible LUAD

samples from TCGA were randomly divided into training (n=254) and

test (n=253) sets in a 1:1 ratio (Table II). Based on analyses of age, sex,

tumor stage and TNM staging, no significant differences between the

training and test sets were identified. Within the training set,

LASSO regression analysis was employed to identify the most

prognostically relevant genes, which led to the construction of a

four-gene prognostic model comprising the MMP1, MMP10, CTSV and F2

genes (Fig. 3B and C). The risk

score formula for this model was as follows: Total risk

score=(0.0837569167784308 × MMP1) + (0.0878985239886888 × MMP10) +

(0.159310542027166 × CTSV + (0.258137401792528 × F2).

| Table II.Clinical characteristics of the three

sets of data randomly generated from The Cancer Genome Atlas

database. |

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of the three

sets of data randomly generated from The Cancer Genome Atlas

database.

| Clinical

features | Total set,

n=507a | Training set,

n=254 | Test set,

n=253 |

P-valueb |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

| 1 |

|

≤65 | 239 (47.14) | 120 (47.24) | 119 (47.04) |

|

|

>65 | 258 (50.89) | 130 (51.18) | 128 (50.59) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.8912 |

|

Female | 272 (53.65) | 135 (53.15) | 137 (54.15) |

|

|

Male | 235 (46.35) | 119 (46.85) | 116 (45.85) |

|

| Stage |

|

|

| 0.3882 |

| I | 272 (53.65) | 127 (50) | 145 (57.31) |

|

| II | 120 (23.67) | 65 (25.59) | 55 (21.74) |

|

|

III | 81 (15.98) | 45 (17.72) | 36 (14.23) |

|

| IV | 26 (5.13) | 13 (5.12) | 13 (5.14) |

|

| T stage |

|

|

| 0.6613 |

| T1 | 169 (33.33) | 80 (31.5) | 89 (35.18) |

|

| T2 | 271 (53.45) | 141 (55.51) | 130 (51.38) |

|

| T3 | 45 (8.88) | 21 (8.27) | 24 (9.49) |

|

| T4 | 19 (3.75) | 11 (4.33) | 8 (3.16) |

|

| N stage |

|

|

| 0.2544 |

| N0 | 327 (64.5) | 155 (61.02) | 172 (67.98) |

|

| N1 | 95 (18.74) | 52 (20.47) | 43 (17) |

|

| N2 | 71 (14) | 42 (16.54) | 29 (11.46) |

|

| N3 | 2 (0.39) | 1 (0.39) | 1 (0.4) |

|

| M stage |

|

|

| 0.9886 |

| M0 | 338 (66.67) | 170 (66.93) | 168 (66.4) |

|

| M1 | 25 (4.93) | 12 (4.72) | 13 (5.14) |

|

Individuals were classified on the basis of the risk

score calculated using this formula, with the average score as the

cutoff. Individuals with scores above the average were categorized

into the high-risk group, whereas those below the average were

placed in the low-risk group. In the total set, 253 individuals

were placed in the high-risk group, and 254 were categorized in the

low-risk group. In the training set, the high- and low-risk groups

each comprised 127 cases, whereas the test set contained 126

high-risk and 127 low-risk cases.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to evaluate the

normality of the data in the high- and low-risk groups. This test

indicated that both datasets deviate significantly from the normal

distribution (high risk, W=0.6951, P<2.2×10−16; low

risk, W=0.96479, P=6.825×10−6). Since the data did not

meet the prerequisite of a normal distribution required for ANOVA,

a non-parametric test method was used, namely Wilcoxon's rank-sum

test. The Wilcoxon test result (W=64,262,

P<2.2×10−16) indicated that there was a significant

difference in the distribution of risk scores between the high- and

low-risk groups.

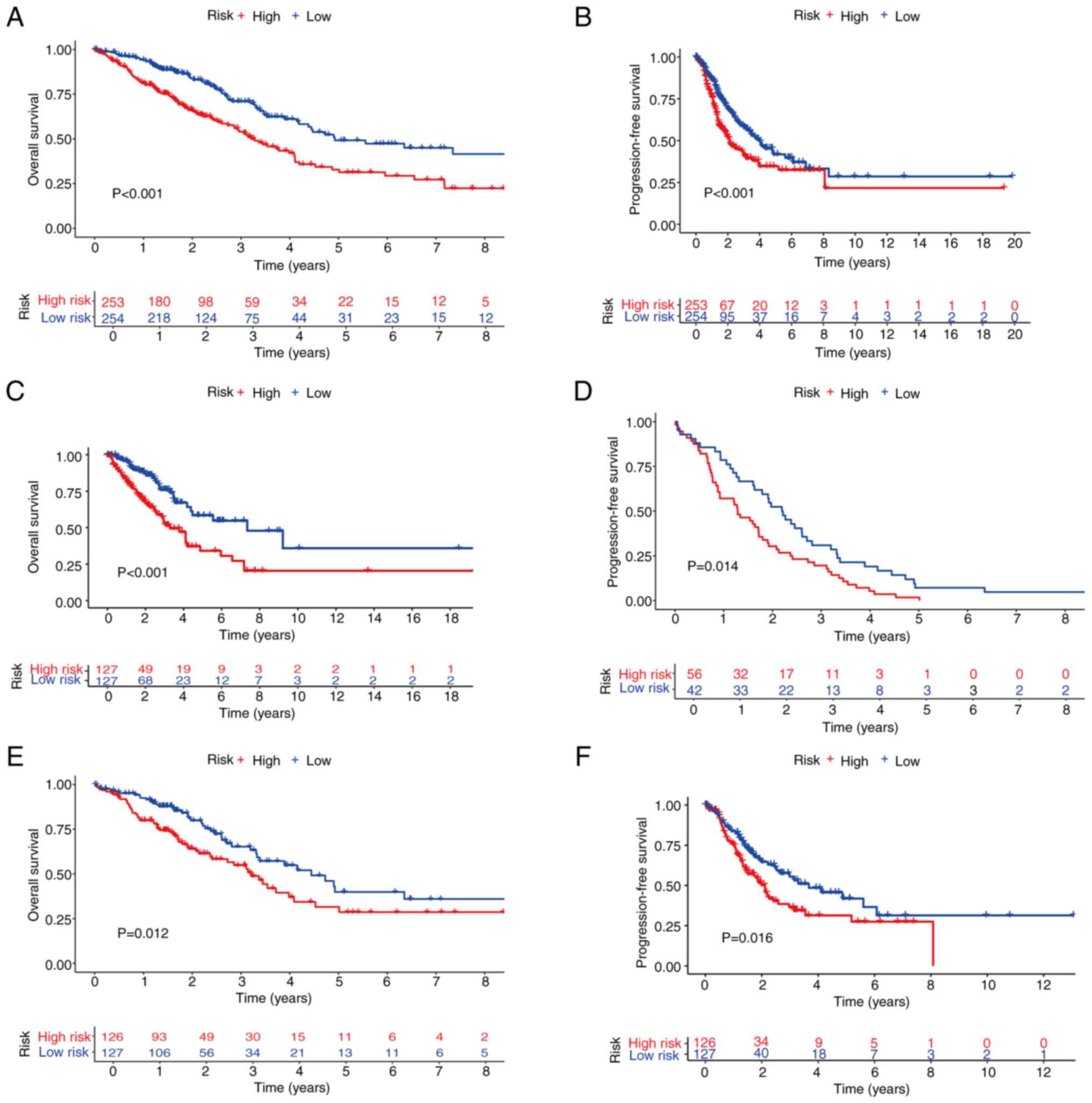

KM curves were subsequently generated to compare the

OS and PFS between the high- and low-risk groups in the total,

training and test sets. This analysis revealed that the OS of the

high-risk group was significantly lower compared with that of the

low-risk group in the total, training and test sets (Fig. 4A, C and E). Similarly, the PFS rates

were significantly shorter in the high-risk group compared with the

low-risk group in all three sets (Fig.

4B, D and F). There were significant statistical differences

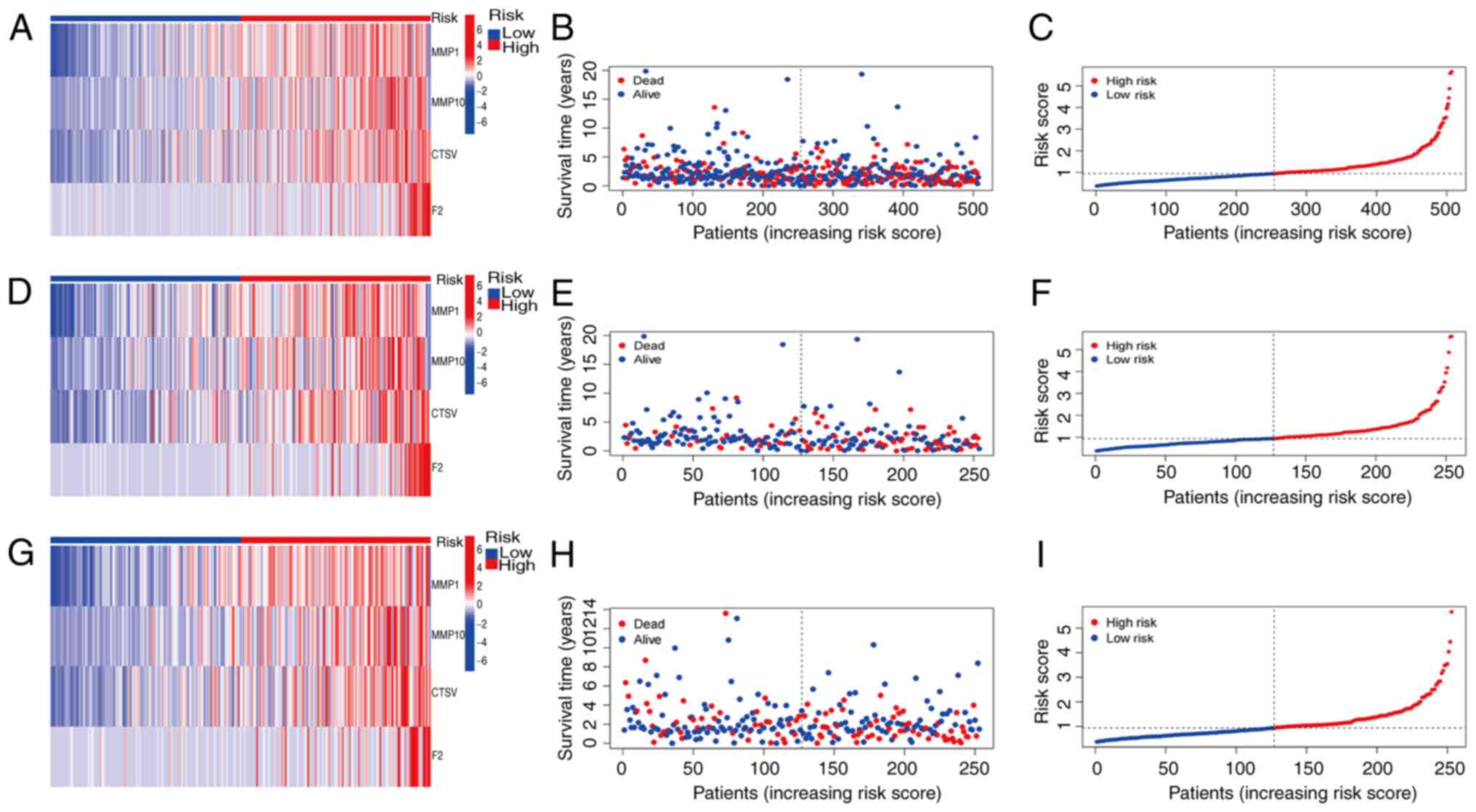

(P<0.05). Prognostic validation using heatmaps identified MMP1,

MMP10, CTSV and F2 as consistently high-risk genes across the total

set (Fig. 5A). Additionally, the

associations between risk scores and survival times between the

high- and low-risk groups in the total set were examined, which

revealed a significant reduction in survival time for patients with

high risk scores (Fig. 5B). Further

analysis of the OS risk score distribution in the total set

corroborated the accuracy of this model (Fig. 5C). Similar results were observed for

validation of the training and test sets (Fig. 5D-I).

Independent analysis of prognostic

factors according to the prognostic model

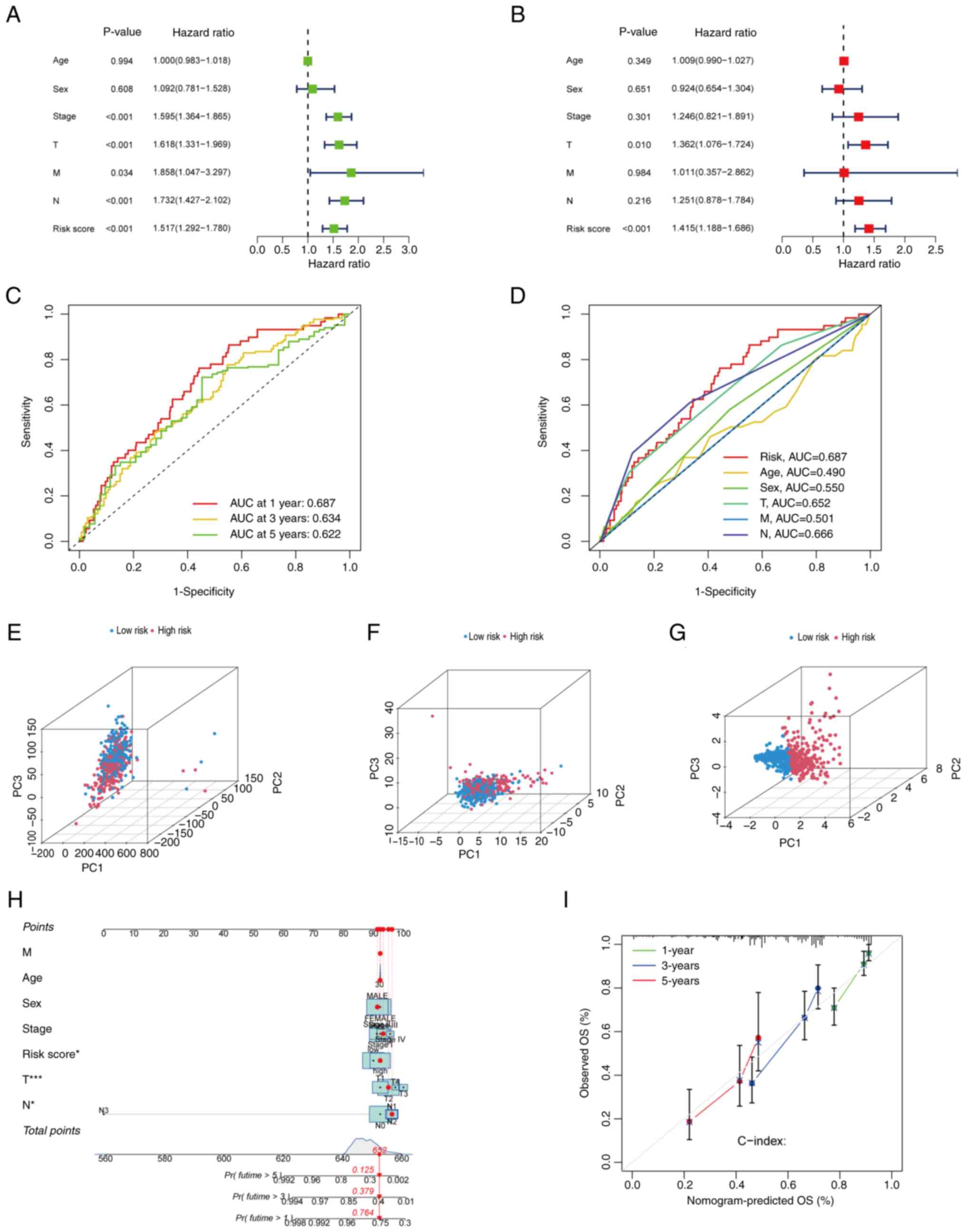

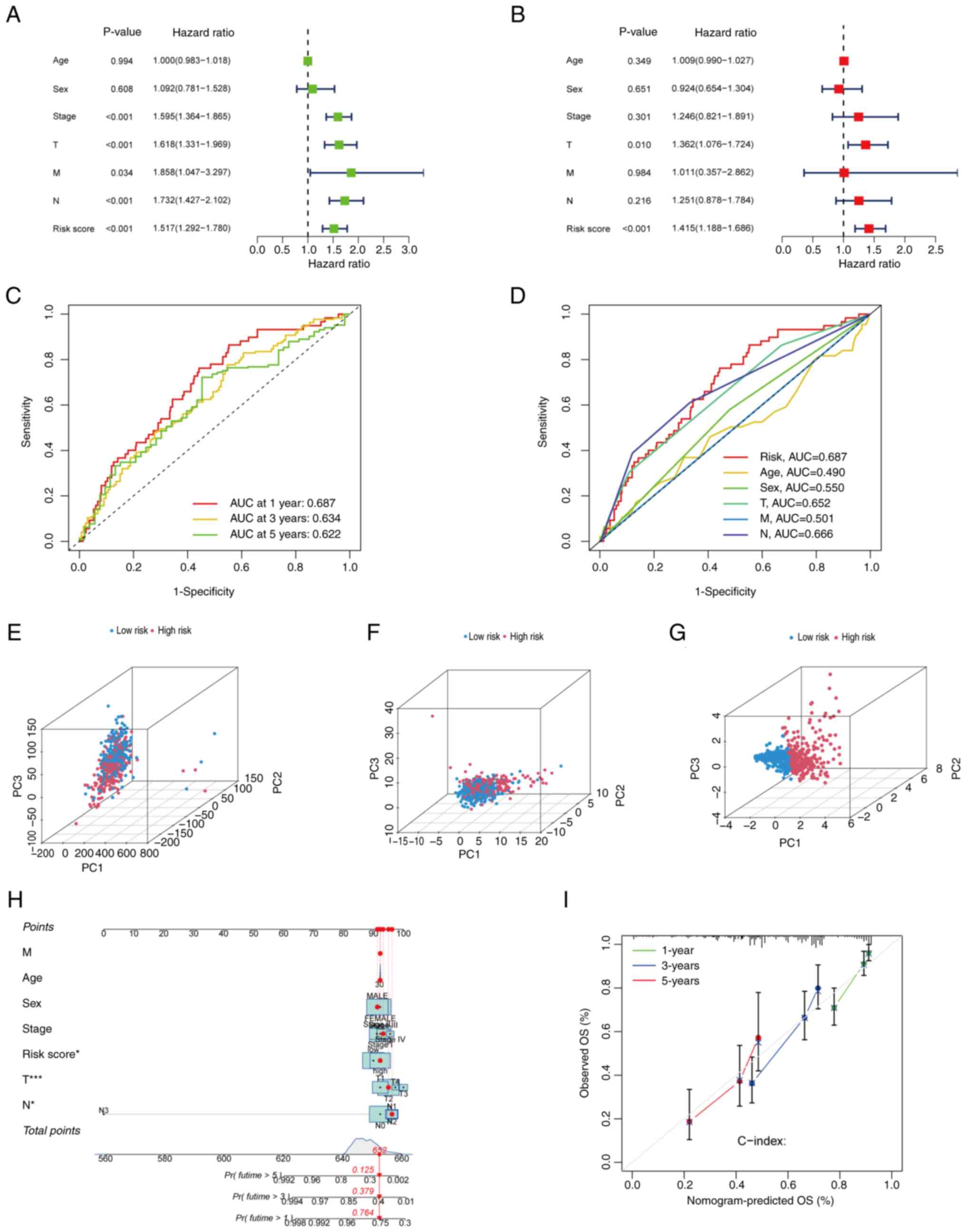

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were performed to determine whether each risk factor functioned as

an independent prognostic indicator, distinct from other clinical

characteristics. Initially, univariate Cox regression analysis was

performed on the total set. The results revealed that age, sex,

tumor stage, T stage, M stage, N stage and the risk score were

significantly associated with prognosis. Specifically, tumor stage

(HR, 1.595; P<0.001), T stage (HR, 1.618; P<0.001), N stage

(HR, 1.732; P<0.001) and risk score (HR, 1.517; P<0.001) were

significantly associated with prognosis, and M stage (HR, 1.858;

P=0.034) was marginally significant (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, multivariate Cox

regression analysis was performed on the total set to assess the

independence of these factors. The results indicated that T stage

(HR, 1.362; P=0.010) and risk score (HR, 1.415; P<0.001) were

independent prognostic indicators. By contrast, tumor stage (HR,

1.246; P=0.301), sex (HR, 0.924; P=0.651), M stage (HR, 1.011;

P=0.984) and N stage (HR, 1.251; P=0.216) did not have significant

independent prognostic value (Fig.

6B). To evaluate the accuracy of the risk model, validation

analysis was subsequently performed using ROC curves. The area

under the ROC curve (AUC) values for 1-, 3- and 5-year survival

were 0.687, 0.634 and 0.622 respectively, demonstrating the

predictive capability of the model (Fig. 6C). In addition, ROC curve analysis

for different clinical characteristics revealed that the predictive

performance of the risk score (AUC, 0.687) was greater than that of

age (AUC, 0.490), sex (AUC, 0.550), T stage (AUC, 0.652), M stage

(AUC, 0.501) and N stage (AUC, 0.666) (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these findings

confirm that the risk score model was capable of outperforming

other clinical characteristics in terms of prognostic accuracy.

| Figure 6.Evaluation of the predictive ability

of the prognostic model. (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate Cox

regression analyses of clinical information and risk scores. (C)

ROC curves for the prediction of 1-, 3- and 5-year OS. (D) ROC

curves comparing the predictive performance of the risk score with

that of various clinical characteristics. Principal component

analysis showing the distribution of individual patients in the

high- and low-risk groups based on (E) genome-wide gene expression

profiles, (F) CRGs and (G) CRGs included in the prognostic model.

(H) Nomogram for prediction of the 1-, 3- and 5-year OS of patients

with LUAD from TCGA. (I) Calibration curve of the nomogram for

predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year OS in patients with LUAD from TCGA.

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; OS, overall survival; LUAD,

lung adenocarcinoma; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; AUC, area under

the curve; Pr(futime), probability of future time. |

PCA and nomogram construction

The present study employed PCA to further assess the

accuracy of the prognostic model. The distribution of samples from

patients with LUAD between the high- and low-risk groups was

compared at the genome-wide level (Fig.

6E), in CRGs (Fig. 6F) and in

genes included in the prognostic model (Fig. 6G). The results revealed significant

differences in the genome-wide distributions, with the genes

involved in the prognostic model exhibiting the highest level of

discrimination. Additionally, a nomogram for patients with LUAD was

constructed (Fig. 6H), which

incorporated variables including age, sex, the TNM, T, N and M

stages, and risk score. This nomogram was used to predict the 1-,

3- and 5-year survival rates of the patients. Calibration curves

were then constructed (Fig. 6I),

which demonstrated that the nomogram possessed high predictive

accuracy.

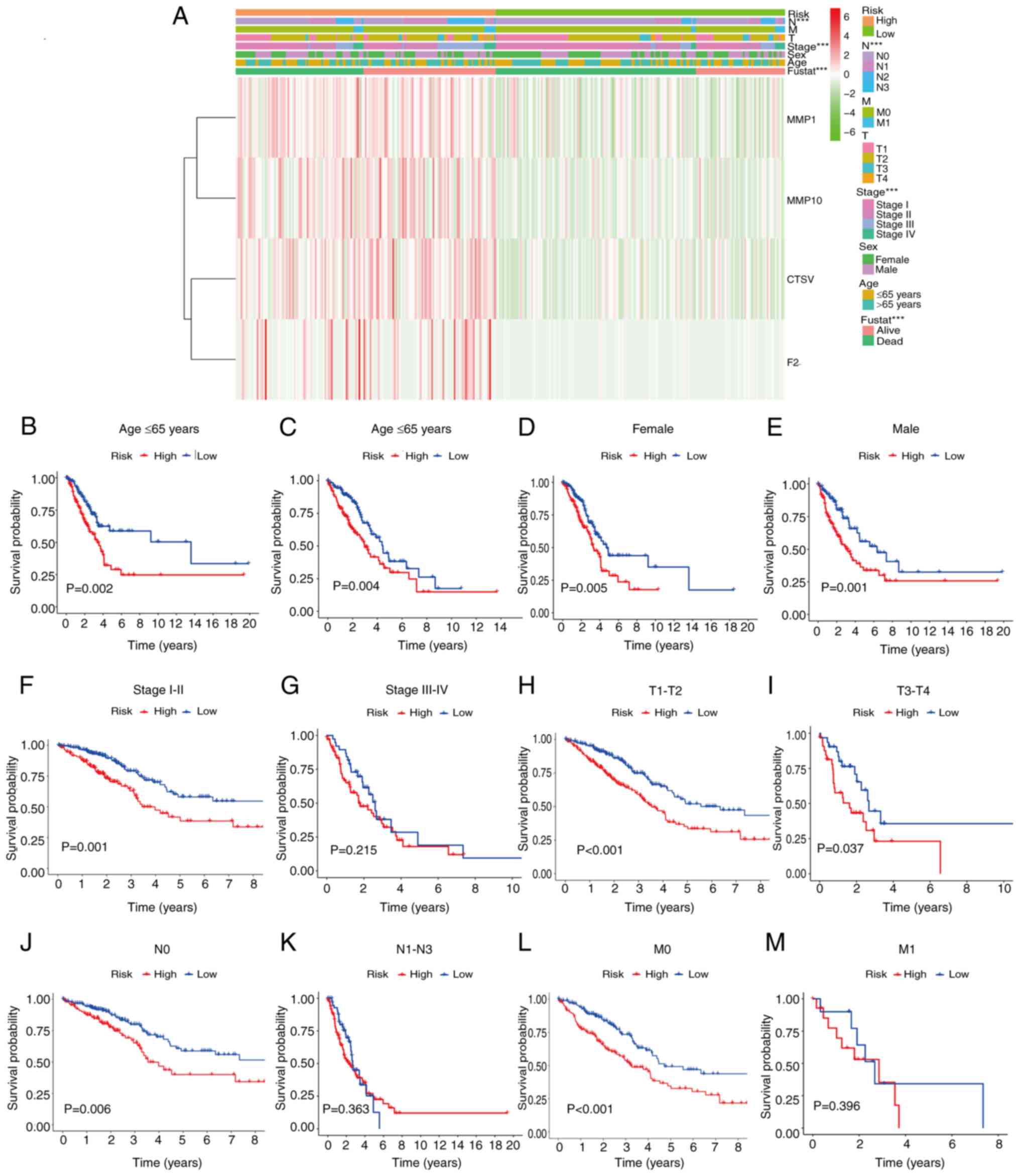

Associations between clinical

characteristics and risk scores

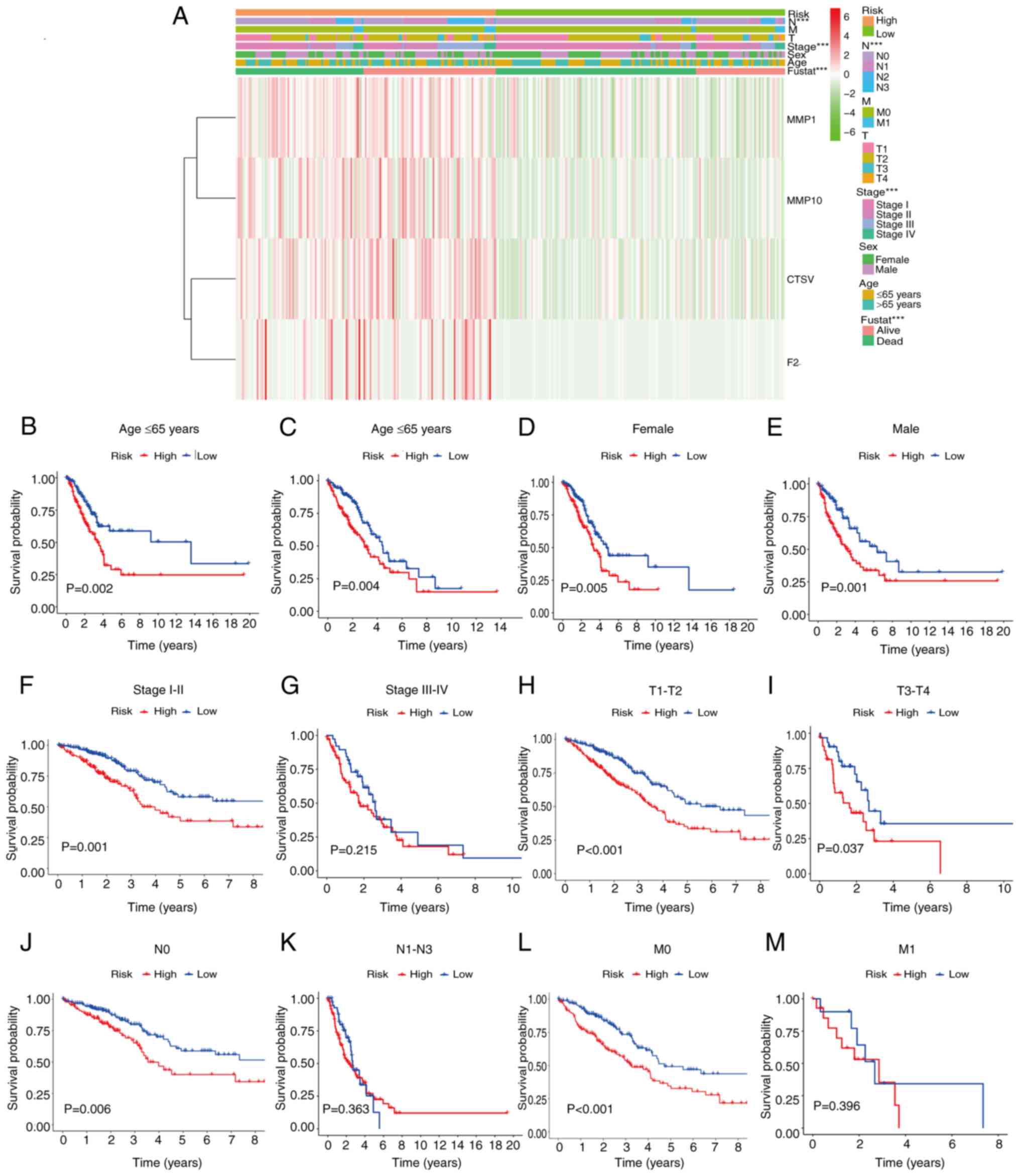

To investigate the associations between various

patient characteristics and risk scores in greater depth, heat maps

were constructed to assess the associations between gene expression

data derived from the model and various clinical and pathological

characteristics (Fig. 7A). This

analysis reaffirmed MMP1, MMP10, CTSV and F2 as high-risk genes,

and highlighted significant correlations between the risk score and

various clinical characteristics, particularly N stage (P<0.01),

tumor stage (P<0.01) and survival time (P<0.01). Furthermore,

KM analyses were performed between the high- and low-risk groups

within clinical characteristic sub-groups. In patients aged <65

or ≥65 years, of either sex, or with tumor stage I–II, T1-T2,

T3-T4, N0 or M0, the prognostic accuracy of the risk model in terms

of distinguishing between the high- and low-risk groups was

significant (Fig. 7B-M).

| Figure 7.Relationships between risk patterns

and clinical characteristics. (A) Associations between prognosis

and clinical characteristics based on data from TCGA. (B-M)

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis of the overall survival rates

in the high- and low-risk groups of patients from TCGA with

different clinical pathological characteristics: (B) Age ≤65 years,

(C) age >65 years, (D) female patients, (E) male patients, (F)

stage I–II, (G) stage III–IV, (H) T1-T2, (I) T3-T4, (J) N0, (K)

N1-N3, (L) M0 and (M) M1. ***P<0.001. TCGA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; CTSV, cathepsin V; F2,

thrombin/coagulation factor II; fustat, follow-up status. |

GO, KEGG and enrichment analyses

Based on the results obtained, the prognostic model

constructed from the genes MMP1, MMP10, CTSV and F2 demonstrated

high accuracy in terms of distinguishing between high- and low-risk

groups for patients with LUAD. GO enrichment analysis revealed that

these genes are primarily associated with ‘sulfur compound

binding’, ‘glycosaminoglycan binding’, ‘serine hydrolase activity’,

‘serine-type peptidase activity’ and ‘serine-type endopeptidase

activity’ at the BP level. At the CC level, these genes were found

to be significantly enriched in ‘collagen-containing extracellular

matrix’, ‘apical part of cell’, ‘vesicle lumen’, ‘cytoplasmic

vesicle lumen’ and ‘secretory granule lumen’. The analysis of MF

identified associations with ‘epidermis development’, ‘negative

regulation of proteolysis’, ‘skin development’ and ‘antimicrobial

humoral response’ Fig. 8A and B).

Furthermore, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that these

genes are primarily associated with ‘neuroactive ligand-receptor

interaction’ (Fig. 8C and D). To

further differentiate between the high- and low-risk groups, GSEA

was performed. This led to the identification of five significant

pathways based on P-value ranking. The GSEA analysis revealed that

the high-risk group was significantly enriched in the pathways

‘cell cycle’, ‘neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction’, ‘pentose

and gluconate interconversion’, ‘porphyrin and chlorophyll

metabolism’ and ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’. By contrast, the

low-risk group was enriched in the pathways ‘allograft rejection’,

‘asthma’, ‘autoimmune thyroid disease’, ‘ribosome’ and ‘systemic

lupus erythematosus’ (Fig. 8E and

F).

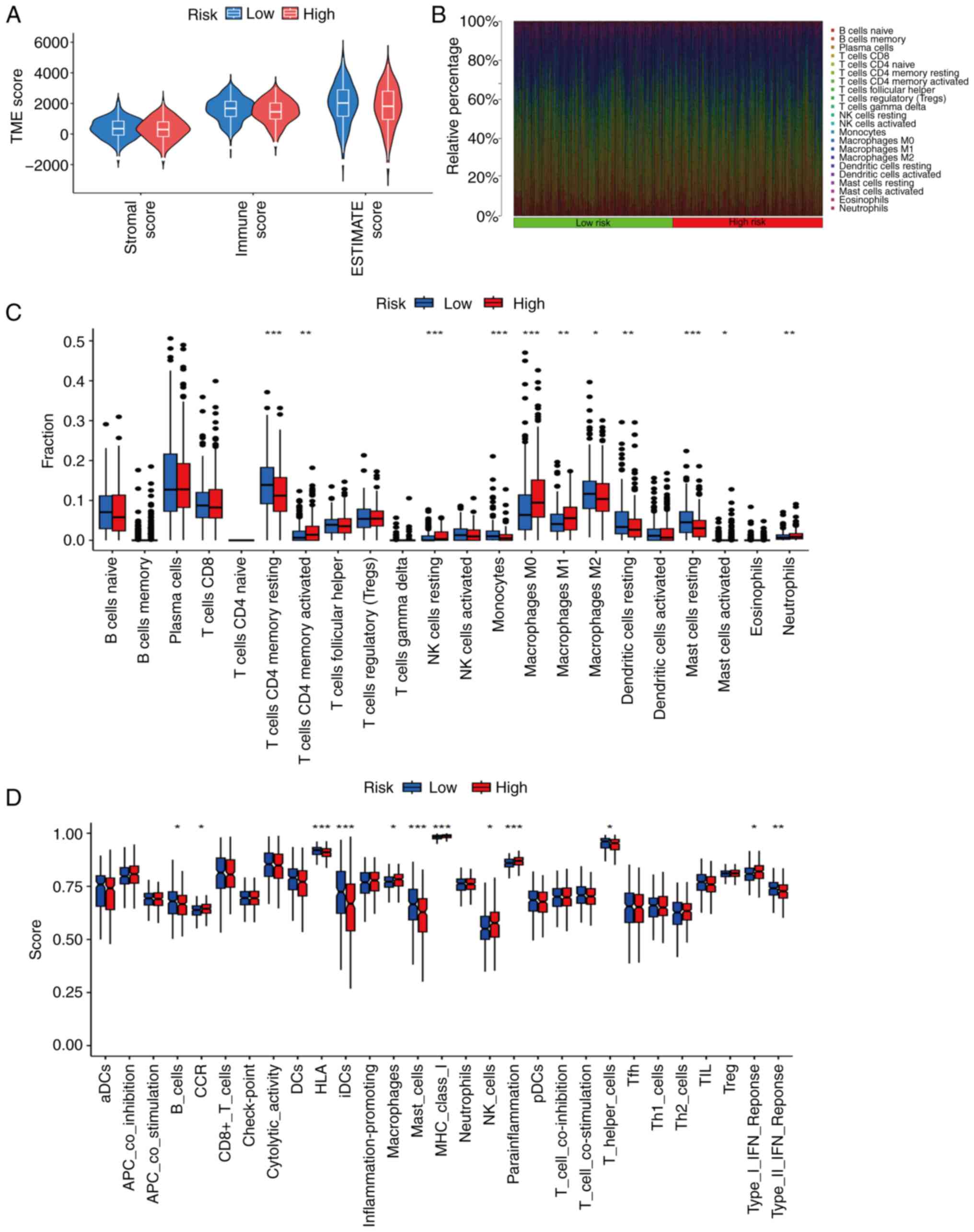

Immunological investigations

In terms of the TME, immune, ESTIMATE and stromal

scores were analyzed. The results revealed no significant

differences in TME scores between the high- and low-risk groups

(Fig. 9A). However, further

analysis detected significant differences in immune cell

infiltration between the two groups. The low-risk group exhibited

significantly higher proportions of resting CD4+ memory

T cells, monocytes, M2 macrophages, resting dendritic cells and

resting mast cells. By contrast, the high-risk group exhibited

significantly higher proportions of activated CD4+

memory T cells, resting natural killer (NK) cells, M0 macrophages,

M1 macrophages, activated mast cells and neutrophils (Fig. 9B and C). In addition, an analysis of

immune function revealed significant differences in the expression

of immune checkpoint molecules: The low-risk group was found to

have higher proportions of B cells, human leukocyte antigens,

interstitial dendritic cells, mast cells, helper T cells and type

II interferon (IFN) responses. By contrast, the high-risk group had

higher proportions of chemokine receptors, macrophages, MHC I

molecules, NK cells, parainflammatory cells and type I IFN

responses (Fig. 9D).

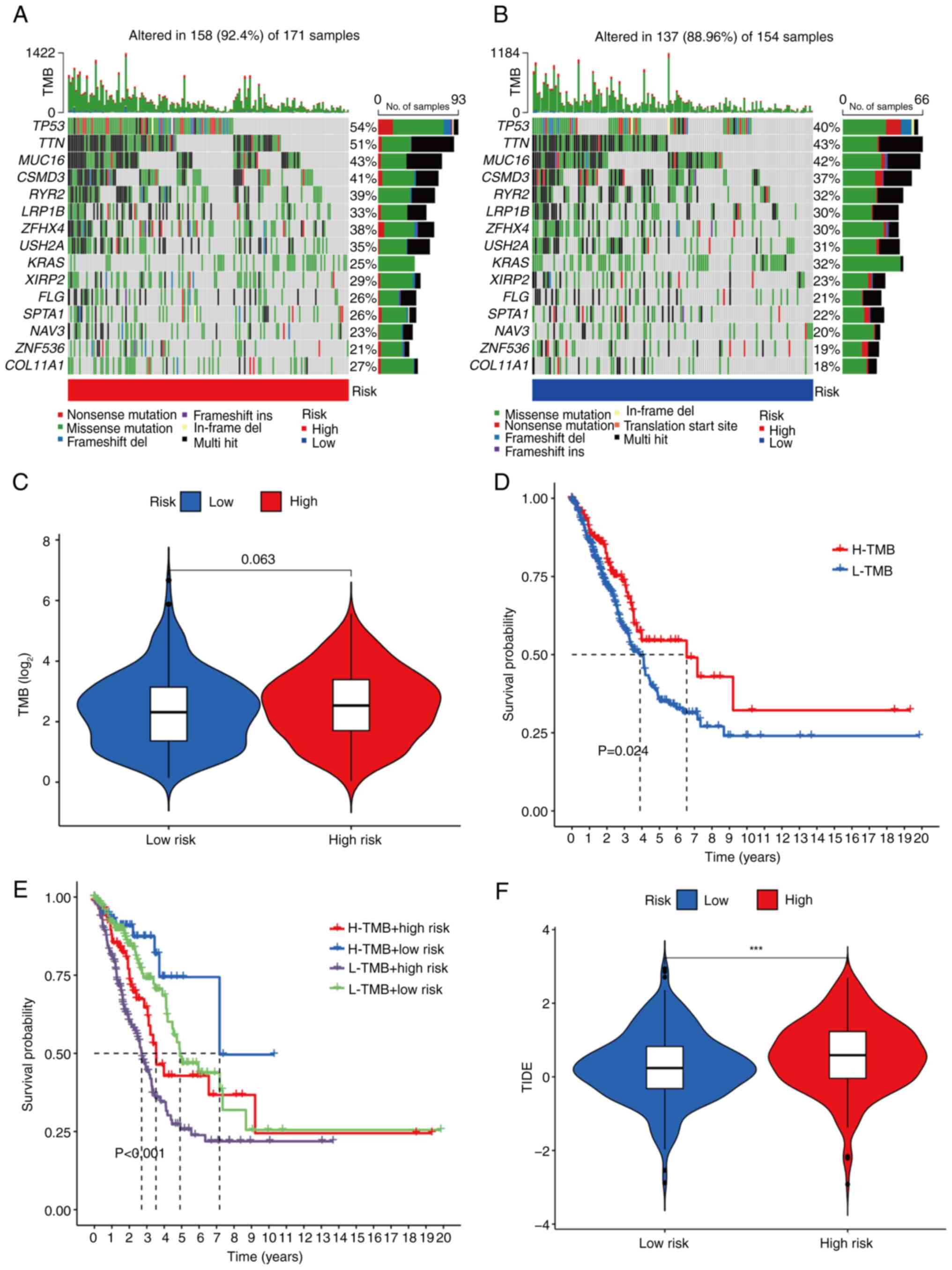

TMB and immune escape

Somatic mutation data were initially collected from

TCGA database for patients with LUAD. Among the 171 samples in the

high-risk group, 158 samples (92.4%) exhibited somatic mutations,

whereas 137 of 154 samples (88.96%) in the low-risk group had

somatic mutations. Further analysis revealed that the incidence of

gene mutations in the high-risk group was higher compared with that

in the low-risk group. The top 15 genes with the highest mutation

rates were tumor protein P53 (TP53), titin (TTN), mucin 16 (MUC16),

CSMD3, RYR2, LRP1B, ZFHX4, USH2A, KRAS, XIRP2, FLG, SPTA1, NAV3,

ZNF536 and COL11A1 (Fig. 10A and

B). TMB analysis further showed that the TMB was higher in the

high-risk group compared with the low-risk group (Fig. 10C). According to the TMB value (cut

off, 7.63), patients were divided into low- and high-TMB groups. KM

survival analysis demonstrated that the OS rate of the high-TMB

group was significantly higher compared with that of the low-TMB

group (Fig. 10D). Comparative

analysis for different combinations of risk and TMB levels revealed

that the high risk + low TMB group had the poorest prognosis,

whereas the low risk + high TMB group had the best prognosis, with

statistically significant differences observed among the groups

(Fig. 10E). To assess immune

escape, TIDE scores were calculated, where a higher TIDE score is

indicative of a greater likelihood of immune escape. The results

obtained showed that the TIDE score of the high-risk group was

significantly higher compared with that of the low-risk group

(Fig. 10F). Further research,

however, is necessary to understand the differences in drug

treatment responses between the high- and low-risk groups.

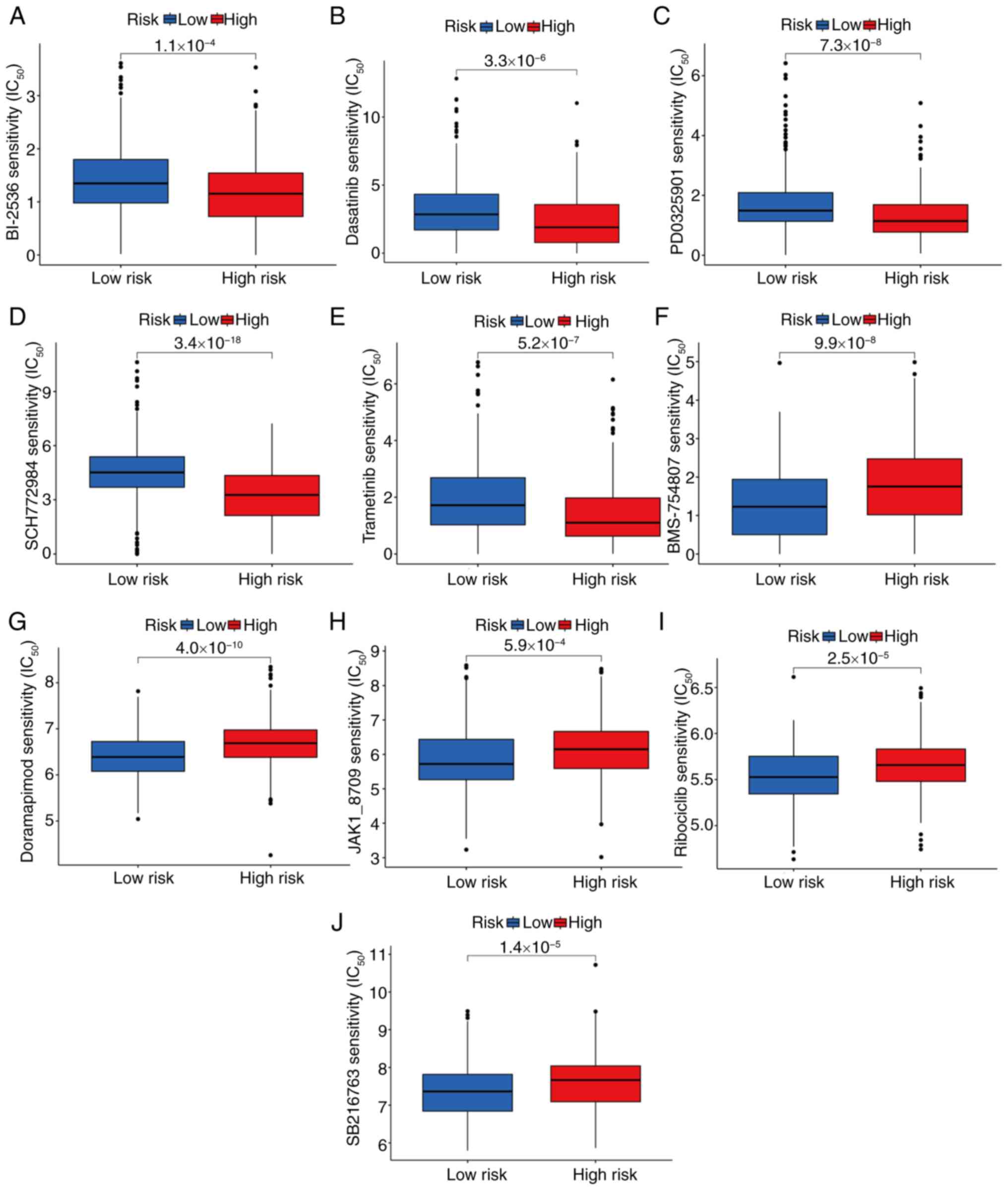

Drug-sensitivity analysis

Differences in drug sensitivity between the high-

and low-risk patient groups were investigated. Analysis of the

drug-sensitivity data revealed significant differences in

IC50 values between the two groups. Specifically, the

high-risk group demonstrated greater sensitivity to the following

drugs: BI-2536 (P=1.1×10−4; Fig. 11A), dasatinib

(P=3.3×10−6; Fig. 11B),

PD0325901 (P=7.3×10−8; Fig.

11C), SCH772984 (P=3.4×10−16; Fig. 11D) and trametinib

(P=5.2×10−7; Fig. 11E).

By contrast, the low-risk group exhibited higher sensitivity to

BMS-754807 (P=9.99×10−8; Fig. 11F), doramapimod

(P=4.0×10−10; Fig.

11G), JAK1-8709 (P=5.9×10−4; Fig. 11H), ribociclib

(P=2.5×10−5; Fig. 11I)

and SB216763 (P=1.4×10−5; Fig. 11J).

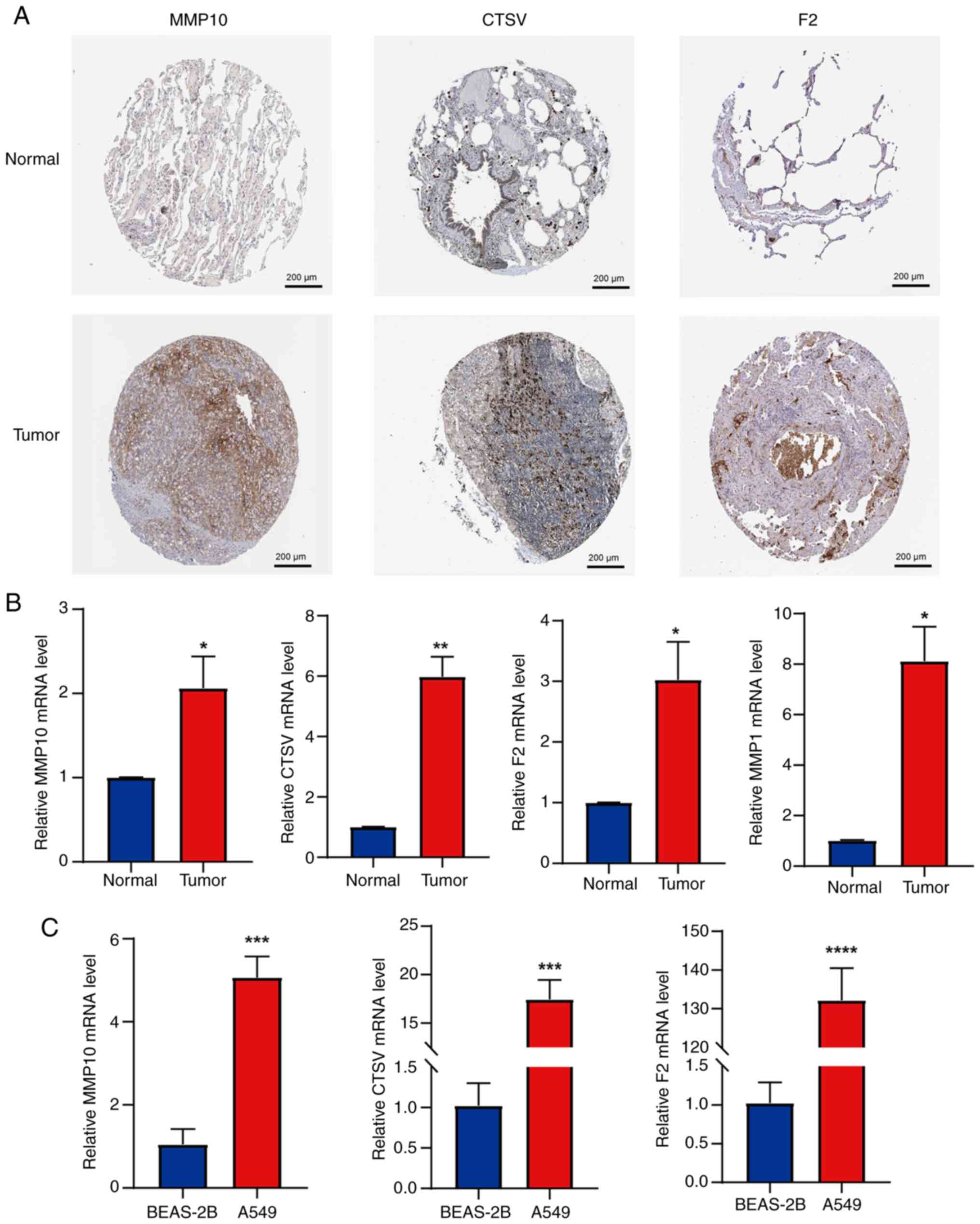

Verification of the CRG expression

levels

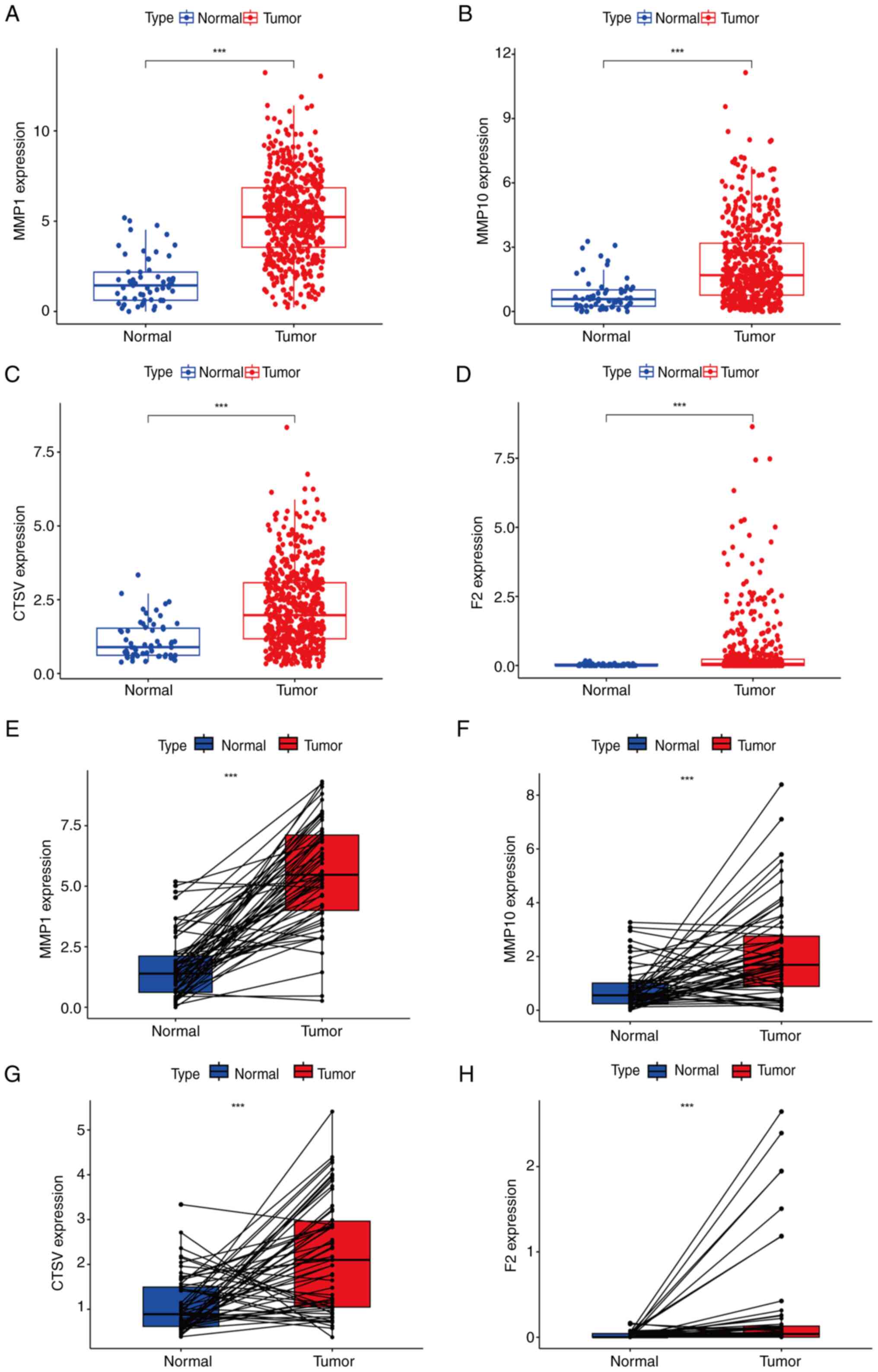

Subsequently, samples from TCGA database were

utilized to assess the expression levels of MMP1, MMP10, CTSV and

F2 in normal and LUAD tissues. Analysis using the Mann-Whitney U

test revealed that the expression of these genes in LUAD tissue was

significantly higher compared with that in normal lung tissue

(Fig. 12A-D). Wilcoxon signed-rank

analysis further confirmed significant differences in the

expression of these genes between the two types of tissues

(Fig. 12E-H), supporting the

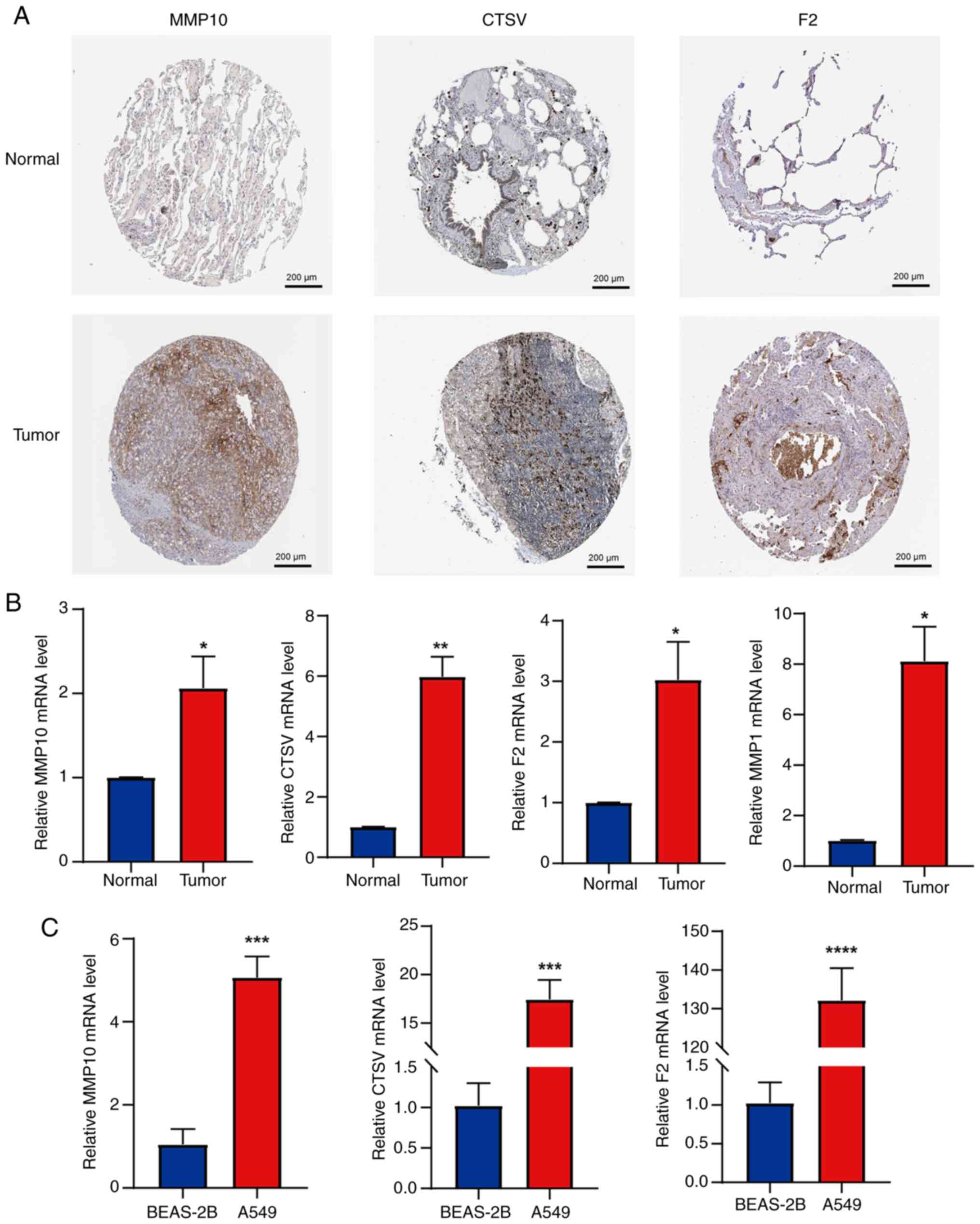

high-risk status of these genes. To validate these findings, IHC

results from the HPA database were compared between LUAD and normal

lung tissues. The protein expression levels of MMP10, CTSV and F2

were observed to be markedly higher in LUAD tissues compared with

normal tissues (Fig. 13A). The HPA

database did not include IHC data for MMP1, so its protein

expression level could not be assessed. Additionally, RT-qPCR

experiments were performed to further verify the accuracy of the

CRG diagnostic model. The mRNA expression levels of MMP10, CTSV,

MMP1 and F2 were found to be upregulated in primary tumor tissues

compared with normal tissue (Fig.

13B). Furthermore, the mRNA levels of MMP10, CTSV and F2 were

found to be significantly higher in the LUAD cell line A549

compared with the BEAS-2B cell line (Fig. 13C). Taken together, these findings

corroborate the bioinformatics analysis results from TCGA

database.

| Figure 13.Validation of the expression levels

of genes in the prognostic model using images from the HPA database

and RT-qPCR analysis. (A) Immunohistochemical staining images of

MMP10, CTSV and F2 in LUAD and normal lung tissue from the HPA

database; magnification, ×100. (B) mRNA expression levels of MMP10,

CTSV, F2 and MMP1 in primary LUAD and peritumoral lung tissues,

measured by RT-qPCR. (C) mRNA expression levels of MMP10, CTSV and

F2 in LUAD and normal bronchial epithelial cell lines, assessed

using RT-qPCR. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs.

normal or BEAS-2B. HPA, Human Protein Atlas; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase;

CTSV, cathepsin V; F2, thrombin/coagulation factor II. |

Discussion

The coagulation system maintains a delicate balance

between clotting and bleeding under physiological conditions,

although this balance is disrupted in disease states (16). The systemic activation of hemostasis

and thrombosis in patients with malignancies has been shown to be

closely associated with tumor occurrence, progression and

metastasis (17,18). A review of numerous studies revealed

that approximately half of patients with malignancies exhibit

coagulation abnormalities, and this proportion rises to as high as

90% in patients with metastasis (19). There is a close interplay between

tumor activation and the coagulation system, which is crucial for

advancing our understanding of cancer biology and cancer-associated

thrombosis, particularly the role of tissue factor. The coagulation

system plays an important role in tumor formation, cell migration,

vascular invasion, extravasation and distant metastasis in LUAD

(20). Therefore,

coagulation-associated biomarkers hold great potential for

prognostication.

In the present study, four key prognostic CRGs,

namely MMP1, MMP10, CTSV and F2, were identified and used to

construct a prognostic signature for patients with LUAD. This

predictive model may serve as a valuable tool in the differential

diagnosis of lung cancer and its mimickers, such as those reported

by Neacşu et al (21).

However, only a handful of studies have highlighted the roles

played by these four genes during the progression of LUAD. MMP1,

which was recognized as a high-risk gene in the present study, is

mainly located in the mitochondria, where it suppresses

mitochondrial respiration, increases hypoxia-inducible factor-1

expression, and reduces the production of reactive oxygen species

(22). MMP1 has been shown to

promote the progression of several types of tumors, including

cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and

colorectal cancer (23–25). In addition, Guo et al

(26) found that wogonin inhibits

lung cancer progression by regulating MMP1 and the PI3K/Akt

signaling pathway. MMP10 (27),

another high-risk gene, is involved in various pathological and

physiological processes, including colitis-associated cancer,

hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer (28–30).

In addition, previous evidence has shown that MMP10 regulates NSCLC

radiosensitivity via the DNA damage repair pathway (31). Therefore, MMP10 may play an

important role in NSCLC and could help determine indications for

radiotherapy. The third high-risk gene, CTSV, is a cysteine

protease, with an active form present in the cytoplasm, nucleus and

plasma membrane. It contributes to the degradation of specific

components of the extracellular matrix, and has been implicated in

the progression of various types of cancer (32–34).

In addition, Zhu et al (35)

found that CSTV promotes the development of lung cancer by

modulating the immunosuppressive microenvironment and cleaving

adhesion molecules. The fourth high-risk gene, F2, encodes the

serine protease thrombin. Elevated levels of thrombin not only

promote blood coagulation but also facilitate tumor growth and

metastasis. Therefore, thrombin and its precursor factors have

emerged as potential targets for the treatment of malignant tumors

and tumor-associated thrombosis (36). Furthermore, F2 has also been found

to be associated with immune infiltration and poor prognosis in

various types of tumors, including LUAD and breast cancer (37). The present study indicates that the

four genes are all upregulated in LUAD tissues and function as

tumor oncogenes, which is consistent with previous findings.

Furthermore, an innovative predictive model incorporating these

four genes has been developed in the present study to assess the

prognosis of LUAD. This model provides valuable insights for the

prognosis assessment and treatment of LUAD, and potentially other

tumor types.

Alterations in the TME are critical in LUAD

progression (38). The quantity and

characteristics of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes serve as

important predictors of prognosis and treatment response in cancers

such as oral squamous cell carcinoma and epithelial ovarian cancer

(39–41). In the present study, significant

differences in immune cell composition were observed between the

high- and low-risk groups. Specifically, the low-risk group

exhibited higher proportions of resting CD4+ memory T

cells, monocytes, M2 macrophages, resting dendritic cells and

resting mast cells. By contrast, the high-risk group exhibited

higher proportions of activated CD4+ memory T cells,

resting NK cells, M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, activated mast

cells and neutrophils. A number of studies have investigated the

antitumor functions of CD4+ T memory cells (42–44),

and their presence has been significantly associated with an

improved prognosis in various types of cancer (45–47).

The role of NK cells in antitumor activity, exerted through their

cytotoxic effects, has been established (48). However, M0 macrophages have been

identified as independent predictive factors of poor outcomes in

patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (49). Previous studies have reported

similar findings to those of the present study, supporting the

accuracy of the current model (50,51).

In the present study, the low-risk group exhibited enhanced immune

cell infiltration and immune function activation, indicative of a

more responsive and active antitumor immune system. By contrast,

the high-risk group was indicated to have a more immunosuppressive

TME, leading to a weaker immune response and potential resistance

to immunotherapy. These differences in immune profiles and TME

characteristics highlight the greater potential of the low-risk

group for improved treatment outcomes, particularly with

immunotherapy. These insights into the associations between risk

groups, TME and immune function are valuable for understanding LUAD

immunology and may assist in the development of personalized

treatment strategies.

In the present study, the mutation rate in the

high-risk group was significantly higher compared with that in the

low-risk group. Notably, the mutation frequencies of TP53, TTN and

MUC16 were significantly different between the two groups.

Mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene are the most common in

human malignancies, particularly in NSCLC (52). In the present study, the analysis of

227 patients with LUAD revealed that differences in mutation rates

between the high- and low-risk groups were primarily attributable

to TP53 gene mutations. These mutations are typically associated

with extensive tumor invasion and poor prognosis (53). Notably, several drugs have been

confirmed to treat malignancies by inhibiting the TP53 signaling

pathway (54). Similarly, TTN plays

a crucial role in the development and progression of various

tumors. In LUAD, the long non-coding RNA TTN-AS1 has been shown to

promote cell invasion and migration (55). In the present study, the mutation

rate of MUC16 was significantly higher in the low-risk group than

in the high-risk group, suggesting that MUC16 may serve as a

protective mutation in LUAD, a conclusion supported by findings in

other tumor types. For example, in ovarian cancer, high expression

of MUC16 has been demonstrated to have a significant antitumor

effect (56). In addition, MUC16 is

considered a potential therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer

(57). An observational study of

patients with LUAD revealed that MUC16 is significantly associated

with a higher TMB and improved clinical prognosis (58), findings that are consistent with

those of the present study. However, the specific mechanism of

action of MUC16 requires further investigation. Genetic mutations

serve as critical targets for the treatment of malignancies. In the

present study, mutations in TP53, TTN and MUC16 were particularly

important when comparing the high- and low-risk LUAD groups.

Specifically, TP53 and TTN mutations play important roles in tumor

progression and invasion in LUAD, whereas MUC16 may act as a

protective mutation, although this warrants further investigation.

Collectively, these findings offer novel insights for targeted

therapies in patients with LUAD, and potential strategies for

improving patient prognosis.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have emerged as

efficacious immunotherapies for different types of cancer. By

targeting molecules such as programmed death 1 (PD-1)/PD-ligand 1

(PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4, they boost

antitumor responses and counteract tumor immune evasion (59,60).

TMB is a key predictive factor of ICI response (61–63),

with higher TMB being associated with improved efficacy of

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (64). An

association between high TMB and improved ICI treatment outcomes

has also been observed (65). In

addition, the TIDE score has been shown to be useful for assessing

the response to immunotherapy and the immune evasion capacity of

tumors (66). In the present study,

the TIDE score in the high-risk group was significantly higher

compared with that in the low-risk group, suggesting a stronger

tendency for immune evasion in high-risk patients, which may affect

treatment outcomes. In addition, the patients with LUAD and high

TMB exhibited longer OS times. However, the cross-validation of TMB

with risk scores revealed that patients in the high-risk group with

low TMB had significantly poorer OS outcomes. These findings

underscore the importance of considering TMB and its interaction

with risk scores when evaluating the immune response and predicting

treatment outcomes in LUAD. This information is vital for guiding

personalized treatment decisions, and for optimizing patient

prognosis in the context of immunotherapy.

In the analysis of drug sensitivity, the response of

patients with LUAD in different risk groups to anticancer agents

was evaluated, which provides insights into personalized treatment

strategies. The results demonstrated that the IC50

values of BI-2536 (67), dasatinib

(68), PD0325901 (69), SCH772984 (70) and trametinib (71) were significantly lower in the

high-risk group than in the low-risk group, suggesting that

patients in the high-risk group may exhibit more favorable

therapeutic responses to these agents. By contrast, BMS-754807

(72), doramapimod (73), JAK1_8709 (74), ribociclib (75) and SB216763 (76) exhibited superior efficacy in the

low-risk group. These findings provide novel insights into the

pharmacotherapy for patients with high- and low-risk LUAD. By

matching the most suitable anticancer drugs with different patient

types, the present study has the potential to facilitate more

precise and effective treatment strategies. Although these drugs

are suggested to have considerable therapeutic potential, the

specific mechanisms underlying their action and actual efficacy in

LUAD require further investigation.

The present study had certain limitations. The data

were mainly derived from TCGA and lacked validation with external

datasets, which may introduce some bias. In addition, the data did

not follow a normal distribution. In subsequent research, a more

detailed analysis of data distribution characteristics will be

conducted, to enhance the scientific rigor of the research methods

and the reliability of the results. Furthermore, although RT-qPCR

analysis confirmed that MMP1, MMP10, F2 and CTSV are highly

expressed in LUAD tissues, the sample size was limited. In future

studies, it is planned to increase the sample size, conduct more

comprehensive clinical validations, and perform in vivo and

in vitro experiments to further evaluate the performance of

the present model as an independent predictor of survival in

real-world clinical settings.

In summary, the present study developed a new

CRG-based model, by integrating bioinformatics analyses of

immune-related indicators and tumor mutations to predict potential

drug sensitivities across different patient subgroups. This model

serves as a novel index for predicting treatment efficacy and

prognosis in patients with LUAD. Future validation of the model

using primary data is essential to confirm its reliability,

accuracy and practicality in a clinical setting. This will involve

conducting large-scale, multi-center clinical trials to test the

performance of the model in diverse patient populations and

real-world scenarios, and indicate its potential to guide

individualized treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Shandong Province

Medical and Health Development Plan (grant no. 202304020860) and

Jinan Municipal Health Commission Science and Technology

Development Plan Project (grant no. 2024302003).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contribution

LZ and XS conceived and designed the research. JL

and XG prepared the manuscript and figures. LL performed the

acquisition and analysis of bioinformatic data. XG, JL, YH and HZ

performed experiments, LZ and XS revised the manuscript. LZ and XS

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Human lung cancer tissues and paired adjacent

noncancerous lung tissues were obtained from three patients

undergoing lung resection. The study was approved by the

Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jinan Central Hospital

(approval no. 20241120026). All subjects signed an IRB-approved

informed consent form prior to enrollment in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL,

Kwon R, Curran WJ Jr, Wu YL and Paz-Ares L: Lung cancer: Current

therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 389:299–311. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang M, Yang C, Dong W, Zhao Y, Chen N

and Gao C: Expression patterns and prognostic role of m6A RNA

methylation regulators in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Cell Mol Biol

(Noisy-le-grand). 70:67–72. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zheng X, Qiu L, Huang Y, Cheng R, Huang S,

Xu K, Cai W, Deng Y, Wang W, Zhong X, et al: Exploring the

molecular and Immune-landscape of lung cancer associated with

cystic airspaces. Mol Immunol. 168:75–88. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hamza MS and Mousa SA: Cancer-Associated

Thrombosis: Risk factors, molecular mechanisms, future management.

Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 26:10760296209542822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Korte W: Changes of the coagulation and

fibrinolysis system in malignancy: Their possible impact on future

diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Clin Chem Lab Med.

38:679–692. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mulder FI, Horváth-Puhó E, van Es N, van

Laarhoven HWM, Pedersen L, Moik F, Ay C, Büller HR and Sørensen HT:

Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: A Population-based

cohort study. Blood. 137:1959–1969. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tatsumi K: The pathogenesis of

Cancer-associated thrombosis. Int J Hematol. 119:495–504. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tieken C and Versteeg HH: Anticoagulants

versus cancer. Thromb Res. 140 (Suppl 1):S148–S153. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kawai K and Watanabe T: Colorectal cancer

and hypercoagulability. Surg Today. 44:797–803. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Saidak Z, Soudet S, Lottin M, Salle V,

Sevestre MA, Clatot F and Galmiche A: A pan-cancer analysis of the

human tumor coagulome and its link to the tumor immune

microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 70:923–933. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Song B, Chi H, Peng G, Song Y, Cui Z, Zhu

Y, Chen G, Wu J, Liu W, Dong C, et al: Characterization of

coagulation-related gene signature to predict prognosis and tumor

immune microenvironment in skin cutaneous melanoma. Front Oncol.

12:9752552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang B, Zou D, Wang N, Wang H, Zhang T,

Gao L, Ma C, Zheng P, Gu B, Li X, et al: Construction and

validation of a novel Coagulation-related 7-gene prognostic

signature for gastric cancer. Front Genet. 13:9576552022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang WX, Gao HW, Cui JB, Zhang AA, Wang

FF, Xie JQ, Lu MH and You CG: Development and validation of a

coagulation-related genes prognostic model for hepatocellular

carcinoma. BMC Bioinformatics. 24:892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Palta S, Saroa R and Palta A: Overview of

the coagulation system. Indian J Anaesth. 58:515–523. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Langer F and Bokemeyer C: Crosstalk

between cancer and haemostasis. Implications for cancer biology and

cancer-associated thrombosis with focus on tissue factor.

Hamostaseologie. 32:95–104. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lima LG and Monteiro RQ: Activation of

blood coagulation in cancer: Implications for tumour progression.

Biosci Rep. 33:2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li Y and Wei S: Advances on mechanisms of

coagulation with non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za

Zhi. 16:676–680. 2013.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Du H and Chen J: Occurrence of venous

thromboembolism in patients with lung cancer and its anticoagulant

therapy. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 21:784–789. 2018.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Neacşu F, Vârban A, Simion G, Şurghie R,

Pătraşcu OM, Sajin M, Dumitru M and Vrînceanu D: Lung cancer

mimickers-a case series of seven patients and review of the

literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 62:697–704. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Herrera I, Cisneros J, Maldonado M,

Ramírez R, Ortiz-Quintero B, Anso E, Chandel NS, Selman M and Pardo

A: Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 induces lung alveolar

epithelial cell migration and proliferation, protects from

apoptosis, and represses mitochondrial oxygen consumption. J Biol

Chem. 288:25964–25975. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jiang S, Liu H, Zhang J, Zhang F, Fan J

and Liu Y: MMP1 regulated by NEAT1/miR-361-5p axis facilitates the

proliferation and migration of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

via the activation of Wnt pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 22:381–391.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu H, Lan T, Li H, Xu L, Chen X, Liao H,

Chen X, Du J, Cai Y, Wang J, et al: Circular RNA circDLC1 inhibits

MMP1-mediated liver cancer progression via interaction with HuR.

Theranostics. 11:1396–1411. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang K, Zheng J, Yu J, Wu Y, Guo J, Xu Z

and Sun X: Knockdown of MMP-1 inhibits the progression of

colorectal cancer by suppressing the PI3K/Akt/c-myc signaling

pathway and EMT. Oncol Rep. 43:1103–1112. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guo J, Jin G, Hu Y, Zhao Z, Nan F, Hu X,

Hu Y and Han Q: Wogonin restrains the malignant progression of lung

cancer through modulating MMP1 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

Protein Pept Lett. 30:25–34. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rempe RG, Hartz AMS and Bauer B: Matrix

metalloproteinases in the brain and Blood-brain barrier: Versatile

breakers and makers. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 36:1481–1507. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen Y, Zhou Y, Chen J, Yang J, Yuan Y and

Wu W: Exosomal lncRNA SNHG12 promotes angiogenesis and breast

cancer progression. Breast Cancer. 31:607–620. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Faraj Shaglouf LH, Ranjpour M, Wajid S and

Jain SK: Elevated expression of cellular SYNE1, MMP10, and GTPase1

and their regulatory role in hepatocellular carcinoma progression.

Protoplasma. 257:157–167. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

He L, Kang Q, Chan KI, Zhang Y, Zhong Z

and Tan W: The immunomodulatory role of matrix metalloproteinases

in colitis-associated cancer. Front Immunol. 13:10939902022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bi Y, Cao K, Wang Y, Yang W, Ma N, Lei X

and Chen Y: Radiosensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer by MMP10

through the DNA damage repair pathway. J Oncol. 2023:56368522023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin CL, Hung TW, Ying TH, Lin CJ, Hsieh YH

and Chen CM: Praeruptorin B mitigates the metastatic ability of

human renal carcinoma cells through targeting CTSC and CTSV

Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 21:29192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu J, Zhang W, Wang Z, Wang Y, Li T, Wang

Y, Ding J and Ning B: Cathepsin V is correlated with the prognosis

and tumor microenvironment in liver cancer. Mol Carcinog.

63:400–416. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sereesongsaeng N, Burrows JF, Scott CJ,

Brix K and Burden RE: Cathepsin V regulates cell cycle progression

and histone stability in the nucleus of breast cancer cells. Front

Pharmacol. 14:12714352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhu L, Zeng Q, Wang J, Deng F and Jin S:

Cathepsin V drives lung cancer progression by shaping the

immunosuppressive environment and adhesion molecules cleavage.

Aging (Albany NY). 15:13961–13979. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu L, Li J, Fan C, Wen M, Li C, Sun W and

Wang W: Construction of a new Immune-related competing endogenous

rna network with prognostic value in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol

Biotechnol. 66:300–310. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Xu S, Tuo QZ, Meng J, Wu XL, Li CL and Lei

P: Thrombin induces ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer

through the cPLA2α/ACSL4 signaling pathway. Transl Oncol.

39:1018172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wu J, Li L, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Wu S

and Xu B: A risk model developed based on tumor microenvironment

predicts overall survival and associates with tumor immunity of

patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 40:4413–4424. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hwang C, Lee SJ, Lee JH, Kim KH, Suh DS,

Kwon BS and Choi KU: Stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

evaluated on H&E-stained slides are an independent prognostic

factor in epithelial ovarian cancer and ovarian serous carcinoma.

Oncol Lett. 17:4557–4565. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Paijens ST, Vledder A, de Bruyn M and

Nijman HW: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era.

Cell Mol Immunol. 18:842–859. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shaban M, Khurram SA, Fraz MM, Alsubaie N,

Masood I, Mushtaq S, Hassan M, Loya A and Rajpoot NM: A Novel

digital score for abundance of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes

predicts disease free survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci

Rep. 9:133412019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Choi A, Jung YW and Choi H: The extrinsic

factors important to the homeostasis of Allergen-specific memory

CD4 T cells. Front Immunol. 13:10808552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kawabe T and Sher A: Memory-phenotype CD4+

T cells: A naturally arising T lymphocyte population possessing

innate immune function. Int Immunol. 34:189–196. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Krueger PD, Osum KC and Jenkins MK: CD4+

memory T-cell formation during type 1 immune responses. Cold Spring

Harb Perspect Biol. 13:a0381412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Okła K, Farber DL and Zou W:

Tissue-resident memory T cells in tumor immunity and immunotherapy.

J Exp Med. 218:e202016052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Park SL, Gebhardt T and Mackay LK:

Tissue-resident memory T cells in cancer immunosurveillance. Trends

Immunol. 40:735–747. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang H, Zhu Z, Modrak S and Little A:

Tissue-resident memory CD4+ T cells play a dominant role

in the initiation of antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 208:2837–2846.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Parrish-Novak J, Dillon SR, Nelson A,

Hammond A, Sprecher C, Gross JA, Johnston J, Madden K, Xu W, West

J, et al: Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell

expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature. 408:57–63.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Xu C, Sui S, Shang Y, Yu Z, Han J, Zhang

G, Ntim M, Hu M, Gong P, Chen H and Zhang X: The landscape of

immune cell infiltration and its clinical implications of

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Adv Res. 24:139–148. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chang J, Wu H, Wu J, Liu M, Zhang W, Hu Y,

Zhang X, Xu J, Li L, Yu P and Zhu J: Constructing a novel

mitochondrial-related gene signature for evaluating the tumor

immune microenvironment and predicting survival in stomach

adenocarcinoma. J Transl Med. 21:1912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Sun X, Li J, Gao X, Huang Y, Pang Z, Lv L,

Li H, Liu H and Zhu L: Disulfidptosis-related lncRNA prognosis

model to predict survival therapeutic response prediction in lung

adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 28:3422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mogi A and Kuwano H: TP53 mutations in

nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol.

2011:5839292011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Perez-Rivas LG, Simon J, Albani A, Tang S,

Roeber S, Assié G, Deutschbein T, Fassnacht M, Gadelha MR, Hermus

AR, et al: TP53 mutations in functional corticotroph tumors are

linked to invasion and worse clinical outcome. Acta Neuropathol

Commun. 10:1392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen H, Deng J, Hou TW and Shan YQ:

Villosol reverses 5-FU resistance in colorectal cancer by

inhibiting the CDKN2A gene regulated TP53-PI3K/Akt signaling axis.

J Ethnopharmacol. 325:1179072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhong Y, Wang J, Lv W, Xu J, Mei S and

Shan A: LncRNA TTN-AS1 drives invasion and migration of lung

adenocarcinoma cells via modulation of miR-4677-3p/ZEB1 axis. J

Cell Biochem. 120:17131–17141. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Mack KN, Samuels ZV, Carter LM, Viray TD,

Mandleywala K, Brooks CL, Hollingsworth MA, Radhakrishnan P and

Lewis JS: Interrogating the theranostic capacity of a

MUC16-Targeted antibody for ovarian cancer. J Nucl Med. 65:580–585.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Aguilar EN, Sagar S, Murray BR, Rajesh C,

Lei EK, Michaud SA, Goodlett DR, Caffrey TC, Grandgenett PM,

Swanson B, et al: Structural basis for multivalent MUC16

recognition and robust Anti-pancreatic cancer activity of humanized

antibody AR9.6. Mol Cancer Ther. 23:836–853. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liu T, Wu L, Liu J, Chen H, Zhu B, Qiao D,

Zhu Y, Liu T, Chen Q and Hu A: Comprehensive characterization of

MUC16 mutations in lung adenocarcinoma for immunotherapies and

prognosis: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore).

102:e354812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liu C, Zheng S, Wang Z, Wang S, Wang X,

Yang L, Xu H, Cao Z, Feng X, Xue Q, et al: KRAS-G12D mutation

drives immune suppression and the primary resistance of

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 42:828–847. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wen Y, Tang F, Tu C, Hornicek F, Duan Z

and Min L: Immune checkpoints in osteosarcoma: Recent advances and

therapeutic potential. Cancer Lett. 547:2158872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Jardim DL, Goodman A, de Melo Gagliato D

and Kurzrock R: The challenges of tumor mutational burden as an

immunotherapy biomarker. Cancer Cell. 39:154–173. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Liu L, Bai X, Wang J, Tang XR, Wu DH, Du

SS, Du XJ, Zhang YW, Zhu HB, Fang Y, et al: Combination of TMB and

CNA stratifies prognostic and predictive responses to immunotherapy

across metastatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 25:7413–7423. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN,

Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, Barron DA, Zehir A, Jordan EJ,

Omuro A, et al: Tumor mutational load predicts survival after

immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 51:202–206.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ricciuti B, Wang X, Alessi JV, Rizvi H,

Mahadevan NR, Li YY, Polio A, Lindsay J, Umeton R, Sinha R, et al:

Association of high tumor mutation burden in Non-small cell lung

cancers with increased immune infiltration and improved clinical

outcomes of PD-L1 blockade across PD-L1 expression levels. JAMA

Oncol. 8:1160–1168. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Cao D, Xu H, Xu X, Guo T and Ge W: High

tumor mutation burden predicts better efficacy of immunotherapy: A

pooled analysis of 103078 cancer patients. Oncoimmunology.

8:e16292582019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ding D, Wang L, Zhang Y, Shi K and Shen Y:

Machine learning developed a programmed cell death signature for

predicting prognosis and immunotherapy benefits in lung

adenocarcinoma. Transl Oncol. 38:1017842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Müller-Tidow C, Bug G, Lübbert M, Krämer

A, Krauter J, Valent P, Nachbaur D, Berdel WE, Ottmann OG, Fritsch

H, et al: A randomized, open-label, phase I/II trial to investigate

the maximum tolerated dose of the Polo-like kinase inhibitor BI

2536 in elderly patients with refractory/relapsed acute myeloid

leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 163:214–222. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Liu L, Zhang B, Wu X, Cheng G, Han X, Xin

X, Qin C, Yang L, Huo M and Yin L: Bioresponsive nanocomplex

integrating cancer-associated fibroblast deactivation and

immunogenic chemotherapy for rebuilding immune-excluded tumors.

Nanomedicine. 58:1027432024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhang X, Yu T, Gao G, Xu J, Lin R, Pan Z,

Liu J and Feng W: Cell division cycle 42 effector protein 4

inhibits prostate cancer progression by suppressing ERK signaling

pathway. Biomol Biomed. 24:840–847. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mi K, Zeng L, Chen Y, Ning J, Zhang S,

Zhao P and Yang S: DHX38 enhances proliferation, metastasis, and

EMT progression in NSCLC through the G3BP1-mediated MAPK pathway.

Cell Signal. 113:1109622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jeon Y, Park S, Lee SH, Kim TH, Kim SW,

Ahn MJ, Jung HA and Chung JH: Combination of dabrafenib and

trametinib in patients with metastatic BRAFV600E-Mutated thyroid

cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 56:1270–1276. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zeng B, Liao X, Liu L, Zhang C, Ruan H and

Yang B: Thyroid hormone mediates cardioprotection against

postinfarction remodeling and dysfunction through the

IGF-1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Life Sci. 267:1189772021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Shi X, Han X and Cao Y, Li C and Cao Y:

ZCCHC14 regulates proliferation and invasion of non-small cell lung

cancer through the MAPK-P38 signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med.

25:1406–1414. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Ling Y, Li J and Zhou L: Smoking-related

epigenetic modifications are associated with the prognosis and

chemotherapeutics of patients with bladder cancer. Int J

Immunopathol Pharmacol. 37:39463202311667742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Prahallad A, Weiss A, Voshol H, Kerr G,

Sprouffske K, Yuan T, Ruddy D, Meistertzheim M, Kazic-Legueux M,

Kottarathil T, et al: CRISPR screening identifies mechanisms of

resistance to KRASG12C and SHP2 inhibitor combinations in Non-Small

cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 83:4130–4141. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Phyu SM, Tseng CC and Smith TAD:

CDP-choline accumulation in breast and colorectal cancer cells

treated with a GSK-3-targeting inhibitor. Magma. 32:227–235. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|