Introduction

Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma (PPMS) is a rare

malignant tumor arising within the lung, originally described by

Nicholson et al (1) in 1999.

In 2011, Thway et al (2)

introduced the term based on its distinctive genetic profile. A

characteristic feature of PPMS is the EWSR1-CREB1 gene fusion,

which aids in its identification and differentiation from other

sarcomas. The World Health Organization formally recognized PPMS as

a distinct interlobar tumor entity in 2015, marking its

classification among rare pulmonary neoplasms (3). To date, fewer than 40 cases have been

reported to the best of our knowledge (4).

Due to its scarcity, the understanding of PPMS

clinical presentation, biological behavior and optimal management

strategies remains limited. Histologically, PPMS is characterized

by a unique myxoid stroma and spindle-shaped cells, which can

resemble other soft tissue sarcomas and contribute to potential

diagnostic challenges (5). The

clinical presentation of PPMS is typically non-specific, and the

lack of clear symptoms often results in incidental detection

(5). Additionally, the pathogenesis

of PPMS remains poorly understood, with few molecular studies

exploring its underlying genetic alterations (2,6).

However, recent advances, such as the identification of EWSR1 gene

rearrangement through fluorescence in situ hybridization

(FISH) testing, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) or sequencing,

have begun to shed light on the molecular characteristics of this

tumor.

The current study presents the case of a 41-year-old

male diagnosed with PPMS that was initially suspected to be

pleomorphic adenoma based on frozen section analysis. The diagnosis

was confirmed through histological examination and

immunohistochemical staining, along with FISH analysis revealing

EWSR1 rearrangement. This case highlights the importance of

increasing awareness and advancing diagnostic precision to better

understand and manage this rare tumor.

Case report

A 41-year-old male was admitted to Jeonbuk National

University Hospital (Jeonju, South Korea) in April 2024, following

the incidental discovery of a mass in the left lower lobe during a

routine health check-up. The patient had no significant past

medical history, and his physical examination was otherwise

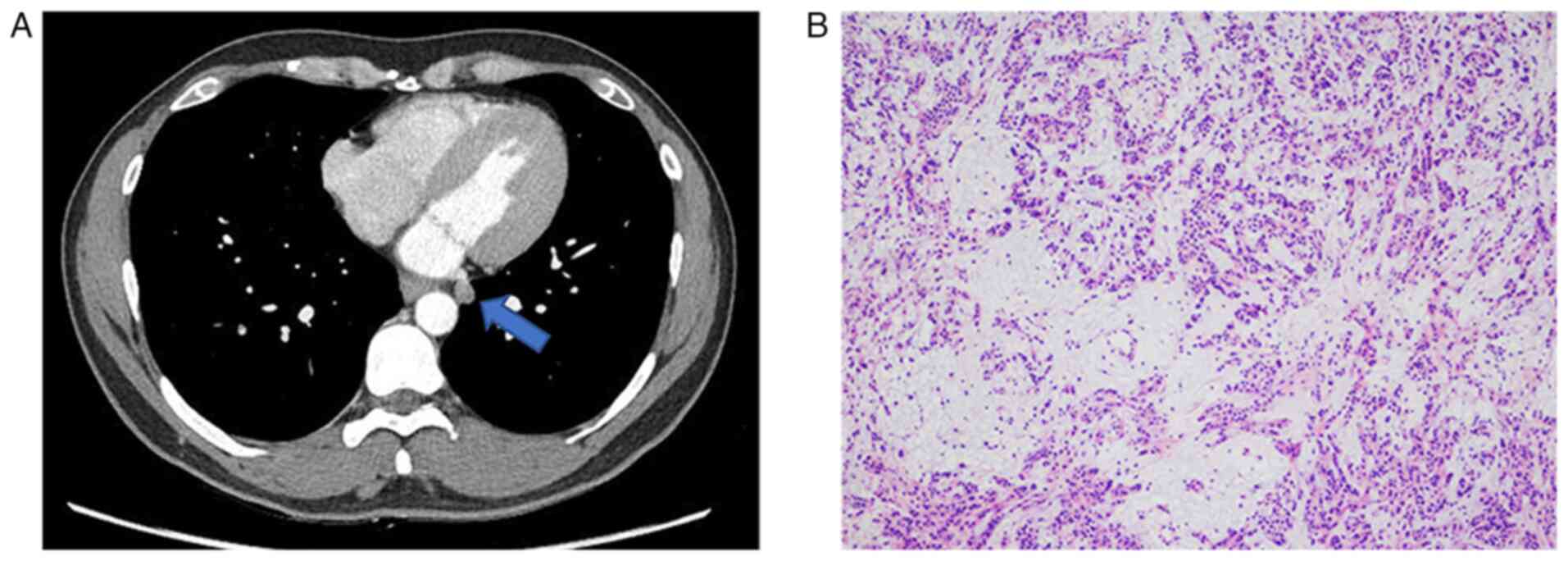

unremarkable. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan

performed at Jeonbuk National University Hospital revealed a small

pulmonary nodule, ~1 cm in size, located in the mediobasal segment

of the left lower lobe (Fig. 1A).

The nodule had relatively well-defined margins, though some areas

appeared irregular, raising suspicion for a potentially malignant

lesion.

Due to its deep-seated location, a percutaneous

transthoracic needle biopsy was considered challenging. Therefore,

to obtain a definitive diagnosis, the patient underwent a wedge

resection of the left lower lobe mass. Intraoperative frozen

section analysis was performed using standard intraoperative

pathological procedures. Tissue samples were rapidly frozen at

−20°C using a cryostat. Sections were cut at a thickness of 5 µm

and mounted on glass slides. Staining was performed with

haematoxylin and eosin (H&E); slides were stained in

haematoxylin at room temperature for 5 min, rinsed in water and

counterstained with eosin at room temperature for 1 min. All

sections were imaged using a light microscope. Frozen section

analysis suggested a high likelihood of pleomorphic adenoma;

however, the final diagnosis was deferred pending permanent

histopathological analysis (Fig.

1B). For permanent histopathological analysis, tissue specimens

were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for

24 h. After fixation, samples were processed and embedded in

paraffin. Sections were cut at a thickness of 4 µm using a

microtome and mounted on glass slides.

H&E staining was performed with haematoxylin

staining for 3 minutes at room temperature, followed by eosin

staining for 7 min utes at room temperature. All stained sections

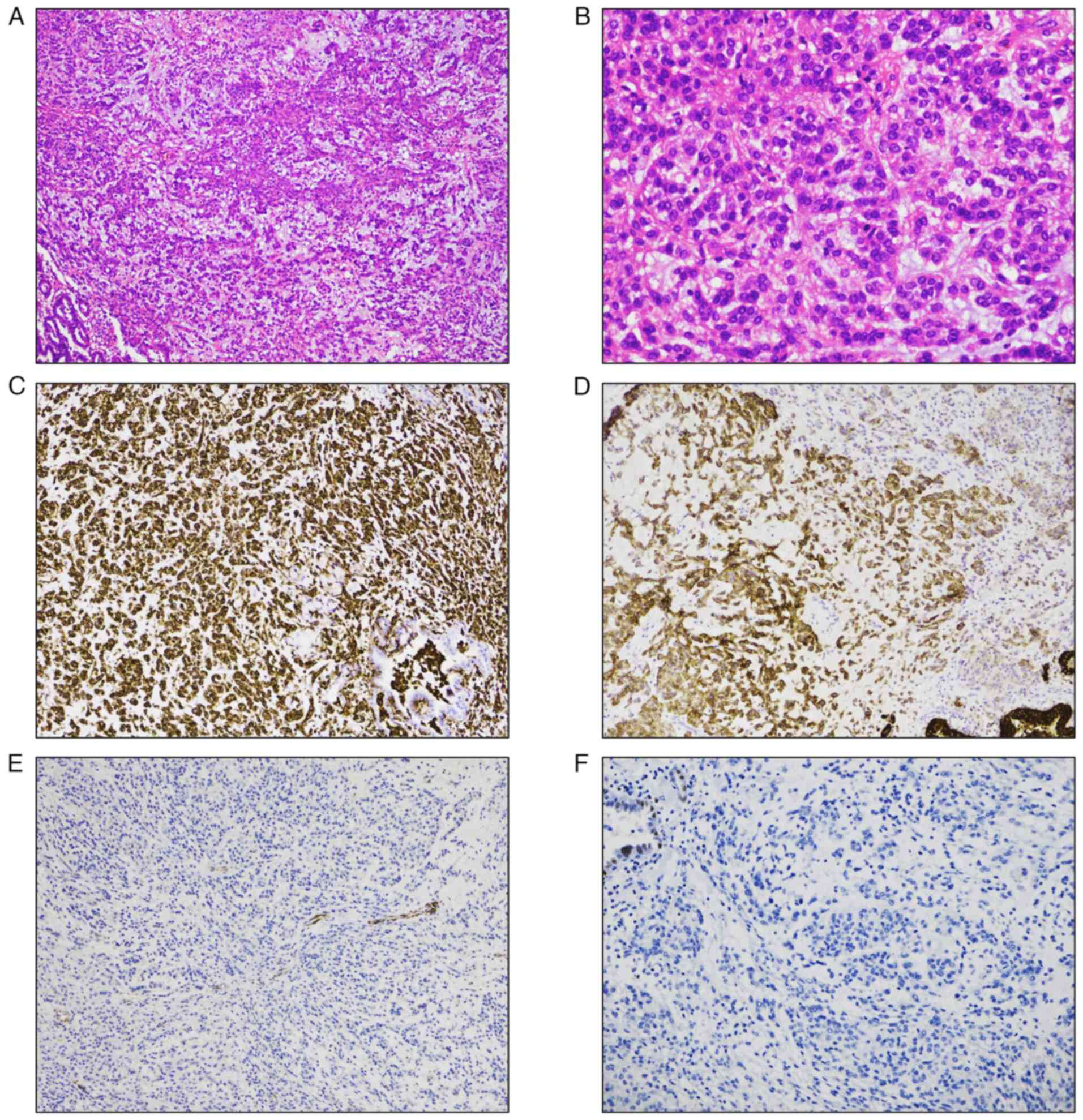

were examined usingnder a light microscope. Examination of the

permanent sections revealed distinctive features, including an

abundant myxoid matrix with embedded spindle, stellate and

rounded/epithelioid cells arranged in a reticular pattern,

exhibiting mild cellular atypia and rare mitotic figures. Notably,

giant or bizarre tumor cells, which have been reported in some

previous cases, were not observed in the present case (Fig. 2A and B).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed to

further aid in diagnosis. Staining was performed using an automated

immunostainer (BenchMark ULTRA; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Tissue sections were

fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 24

h, processed routinely, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut

at a thickness of 4 µm and mounted on glass slides. All primary

antibodies used were ready-to-use products provided by the

manufacturer (Roche); therefore, no dilution was required. All

staining steps, including deparaffinization, antigen retrieval,

blocking, antibody incubation, and detection, were carried out

automatically under pre-optimized and standardized conditions

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Hematoxylin was applied as a counterstain for 5

minutes at room temperature. All stained slides were examined using

a light microscope. The tumor cells were positive for vimentin and

epithelial membrane antigen but negative for myoepithelial cell

markers, including calponin, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin and

p63 (Fig. 2C-F). This pattern

effectively ruled out pleomorphic adenoma and other myoepithelial

tumors. Other markers, such as CD68, anaplastic lymphoma kinase

(ALK), insulinoma-associated 1 (INSM1) and synaptophysin were

negative. Given these histological and immunohistochemical

findings, which aligned with characteristics of PPMS, the

possibility of PPMS was considered.

To further confirm the diagnosis, fluorescence in

situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed on formalin-fixed,

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections. A commercially available

break-apart probe targeting the EWSR1 gene (Vysis LSI

EWSR1 Break Apart Rearrangement Probe; Abbott

Pharmaceutical) was used in accordance with the manufacturer's

protocol. This probe is specifically designed to detect

EWSR1 gene rearrangement but does not identify the specific

fusion partner. All procedures, including hybridization and washing

steps, were carried out in accordance with the manufacturer's

instructions. Fluorescent signals were evaluated using a

fluorescence microscope, and at ≥100 nuclei were assessed by a

trained cytogeneticist. A result was considered positive when

>15% of the examined nuclei demonstrated a split signal pattern,

consistent with EWSR1 rearrangement. In this case, the FISH

analysis demonstrated the presence of an EWSR1 gene

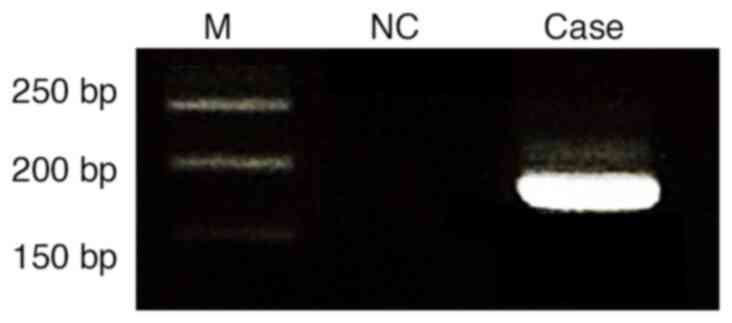

rearrangement. Following this, RNA was extracted from the specimen

to specifically verify the presence of the EWSR1-CREB1 fusion.

Total RNA was extracted from FFPE tumor tissue using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse

transcription was performed using the SuperScript™ IV First-Strand

Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's standard protocol. PCR amplification was carried out

using primers designed to target exon 7 of EWSR1

(5′-TCCTACAGCCAAGCTCCAAGTC-3′) and exon 7 of CREB1

(5′-GTACCCCATCGGTACCATTGT-3′). The PCR thermocycling conditions

were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed

by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 60°C

for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 30 sec, with a final extension

at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on

a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under

UV illumination. A distinct band corresponding to the

EWSR1-CREB1 fusion transcript was observed (Fig. 3). Based on the histopathological

findings, immunohistochemical profile and molecular analysis, a

final diagnosis of primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma was

established. The patient did not receive adjuvant therapy

postoperatively and has been monitored with imaging studies every 3

months. As of 10 months after surgery, there is no evidence of

recurrence or metastasis. Due to the rarity of PPMS and its

potential for misdiagnosis, further studies are needed to improve

our understanding of its biological behavior, treatment responses,

and prognostic factors.

Discussion

PPMS is a rare neoplasm, and as such, comprehensive

epidemiological data are limited (5). The tumor most commonly affects

middle-aged adults, with a median age of 49 years (range, 26–80

years) and a slight female predominance (5). Due to its rarity, precise incidence

rates have not been established in population-based studies

(5). The etiology of PPMS remains

unclear, with no definitive causative factors identified. Unlike a

number of other malignancies, PPMS has not been associated with

smoking or linked to known inherited cancer predisposition

syndromes (5). From a prognostic

standpoint, surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment,

with ~90% of patients remaining disease-free following surgery

(5). Nonetheless, a small subset of

cases demonstrates metastatic progression, with documented spread

to the lung, kidney or brain, and rare instances of lethal outcomes

have been reported (5).

PPMS is a challenging tumor to diagnose, given its

histological overlap with other soft tissue sarcomas and

myoepithelial tumors. The present case exemplifies the diagnostic

complexities associated with PPMS, which often lead to its initial

misidentification. In the present patient, the intraoperative

frozen section analysis suggested pleomorphic adenoma, a

differential diagnosis often considered due to the myxoid nature of

the lesion. However, definitive histopathology,

immunohistochemistry and molecular testing ultimately confirmed the

diagnosis of PPMS. The current case highlights the critical role of

an integrated approach that combines histological,

immunohistochemical and molecular analyses to achieve an accurate

diagnosis.

The diagnostic process in the present case

illustrates the challenges involved in diagnosing PPMS. The initial

frozen section suggested pleomorphic adenoma, a diagnosis that was

ultimately excluded based on the permanent histopathological and

immunohistochemical findings. Histologically, PPMS is characterized

by an abundant myxoid matrix with embedded tumor cells exhibiting

spindle, stellate or rounded/epithelioid morphology, typically

arranged in a reticular or cord-like pattern (5). The tumor cells display mild to

moderate atypia, with low mitotic activity, though variability

exists among cases (5). These

features can closely resemble those of other soft tissue tumors,

making accurate differentiation essential (5). Immunohistochemistry plays a crucial

role in differentiating PPMS from other myoepithelial tumors

(7). In the present case, the tumor

cells stained positive for vimentin, a mesenchymal marker, but were

negative for markers of myoepithelial differentiation, such as

calponin, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin and p63, which helped

rule out pleomorphic adenoma and similar entities.

A key diagnostic feature of PPMS is the EWSR1-CREB1

gene fusion, detectable by FISH or molecular techniques such as

RT-PCR and sequencing (7). In the

current case, the diagnosis was confirmed by identifying the EWSR1

rearrangement through FISH analysis, along with supportive

immunohistochemical staining. Additionally, RT-PCR was conducted

using primers designed to target exon 7 of EWSR1 and exon 7 of

CREB1, and the amplification results confirmed the presence of the

EWSR1-CREB1 fusion, further supporting the diagnosis. This

highlights the crucial role of molecular testing in distinguishing

PPMS from other sarcomas. The EWSR1-CREB1 fusion, although not

entirely specific to PPMS, is highly characteristic and has been

instrumental in defining this rare entity (8). A limitation of the present case report

is the inability to confirm the EWSR1-CREB1 fusion using RNA

sequencing. While the diagnosis was established through FISH and

RT-PCR, RNA-sequencing would have provided a more definitive and

comprehensive molecular validation of the fusion event.

However, several other tumors with similar

histological characteristics also show EWSR1 rearrangements, which

can complicate the diagnosis of PPMS (9,10).

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is one tumor with

overlapping features, as it is characterized by multinodular growth

and a rich myxoid matrix, similar to PPMS (11). It contains spindle-shaped to ovoid

cells embedded in cords within the matrix. EMC is characterized by

the presence of an EWSR1-NR4A3 fusion (11). Therefore, testing solely for EWSR1

rearrangement may not reliably distinguish EMC from PPMS.

Immunohistochemical staining can aid in differentiating these two

entities. EMC may show positive staining for neuroendocrine markers

such as INSM1 and synaptophysin, reflecting a neural

differentiation profile not typically seen in PPMS. By contrast,

PPMS generally does not express INSM1 or synaptophysin, which

serves as an important clue in distinguishing it from EMC (12). Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma

(AFH) is another tumor with overlapping histological features,

including a myxoid stroma and spindle cell morphology (13). Similar to PPMS, AFH can harbor EWSR1

rearrangements, most commonly resulting in EWSR1-CREB1 or

EWSR1-ATF1 fusions, which can complicate the differential diagnosis

(13). Immunohistochemistry offers

additional diagnostic insight, as AFH often shows positive staining

for markers such as CD68 and ALK, which are typically absent in

PPMS (14). These

immunohistochemical differences provide important clues for

distinguishing AFH from PPMS. In the present case,

immunohistochemical staining demonstrated negative results for

synaptophysin, INSM1, CD68 and ALK. These findings further support

the diagnosis of PPMS.

The treatment of PPMS poses significant challenges

due to its rarity and limited clinical data. Due to the lack of

established treatment guidelines, management is largely based on

case reports and small case series. Surgical resection is generally

considered the primary treatment for PPMS, especially for localized

tumors, as complete resection offers the best chance for prolonged

survival (6). In cases where the

tumor is confined to the lung, lobectomy or wedge resection with

negative margins is often pursued to achieve local control and

reduce the risk of recurrence (4,15). For

patients with inoperable or metastatic PPMS, systemic therapies,

such as chemotherapy, may be considered, although the response

rates in PPMS are not well documented (7). Sarcoma-oriented chemotherapy regimens,

including agents such as doxorubicin and ifosfamide, have been used

in some cases, but their efficacy remains uncertain (2,16). Due

to the slow growth of PPMS in some patients, close surveillance may

be preferred in select cases where aggressive treatment may not

provide significant benefit (6).

Emerging molecular insights into PPMS, particularly the

identification of EWSR1-CREB1 fusions, may pave the way for

targeted therapies in the future (6). While no targeted therapies specific to

PPMS are available, identifying molecular characteristics could

open possibilities for the development of novel therapies aimed at

these fusion proteins. Future research and collaboration among

institutions will be essential to improve understanding of the

biology of PPMS and to establish more standardized treatment

protocols for this rare tumor.

In conclusion, the present case highlights the

critical role of comprehensive diagnostic techniques, including

histological, immunohistochemical and molecular approaches, in

identifying PPMS. Increased awareness of PPMS among clinicians and

pathologists is essential for avoiding misdiagnosis, given its

resemblance to other myxoid neoplasms. Further research and

accumulation of case data are necessary to enhance our

understanding of PPMS and establish standardized treatment

protocols, improving patient outcomes for this rare malignancy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JHK and KMK conceptualized the study and wrote the

original manuscript. KMK searched the literature and obtained

case-related data. KMK and JHK analyzed data and relevant

literature. KMK reviewed and edited the final draft. KMK and JHK

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (IRB no. 2024-09-008)

and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provide written informed consent for the

publication of his images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Nicholson AG, Baandrup U, Florio R,

Sheppard MN and Fisher C: Malignant myxoid endobronchial tumour: A

report of two cases with a unique histological pattern.

Histopathology. 35:313–318. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Thway K, Nicholson AG, Lawson K, Gonzalez

D, Rice A, Balzer B, Swansbury J, Min T, Thompson L, Adu-Poku K, et

al: Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma with EWSR1-CREB1 fusion: A new

tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 35:1722–1732. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A

and Nicholson AG: Introduction to the 2015 World Health

Organization classification of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus,

and heart. J Thorac Oncol. 10:1240–1242. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Xu T, Wu L, Ye H, Luo S and Wang J:

Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma in the interlobar fissure of the

left lung lobe: A case report. BMC Pulm Med. 24:3132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

World Health Organization (WHO), . WHO

Classification of Tumours Editorial Board Thoracic Tumours.

International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2021

|

|

6

|

Chen Z, Yang Y, Chen R, Ng CS and Shi H:

Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma with EWSR1-CREB1 fusion: A case

report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 15:1–10. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Miao X, Chen J, Yang L and Lu H: Primary

pulmonary myxoid sarcoma with EWSR1:: CREB1 fusion: A literature

review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 150:1082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Koelsche C, Tavernar L, Neumann O, Heußel

CP, Eberhardt R, Winter H, Stenzinger A and Mechtersheimer G:

Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma with an unusual gene fusion

between exon 7 of EWSR1 and exon 5 of CREB1. Virchows Arch.

476:787–791. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Thway K and Fisher C: Mesenchymal tumors

with EWSR1 gene rearrangements. Surg Pathol Clin. 12:165–190. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Flucke U, van Noesel MM, Siozopoulou V,

Creytens D, Tops BBJ, van Gorp JM and Hiemcke–Jiwa LS: EWSR1-the

most common rearranged gene in soft tissue lesions, which also

occurs in different bone lesions: an updated review. Diagnostics

(Basel). 11:10932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Finos L, Righi A, Frisoni T, Gambarotti M,

Ghinelli C, Benini S, Vanel D and Picci P: Primary extraskeletal

myxoid chondrosarcoma of bone: Report of three cases and review of

the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 213:461–466. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Giner F, López-Guerrero JA, Machado I,

Rubio–Martínez LA, Espino M, Navarro S, Agra–Pujol C, Ferrández A

and Llombart–Bosch A: Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: p53 and

Ki-67 offer prognostic value for clinical outcome-an

immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 31 cases. Virchows

Arch. 482:407–417. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rossi S, Szuhai K, Ijszenga M, Tanke HJ,

Zanatta L, Sciot R, Fletcher CDM, Tos APD and Hogendoorn PCW:

EWSR1-CREB1 and EWSR1-ATF1 fusion genes in angiomatoid fibrous

histiocytoma. Clin Cancer Res. 13:7322–7328. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ponmar M, Badrinath T, Ramachandran A,

Kurian JJ, Gaikwad P, Thomas BP, Kandagaddala M and Prabhu AJ: Case

series of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma (AFH)-A

clinico-radiological and pathological conundrum. Indian J Surg

Oncol. 16:1–12. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hutchings H, Schwarze E, Ahsan B, Cox J

and Okereke I: Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma: A case report and

review of the literature. Glob J Perioper Med. 7:1–3. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Niu SY, Sun L, Hsu ST, Hwang SF, Liu CK,

Shih YH, Lu TF, Chen YF, Lai LC, Chang PL and Lu CH: Efficacy and

toxicities of doxorubicin plus ifosfamide in the second-line

treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Front Oncol. 13:12825962023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|