Introduction

Breast cancer is globally the most common cancer

among women (1), and existing

treatments mainly include surgery, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy,

targeted therapy and radiotherapy. Radiotherapy is typically

administered to patients who have undergone breast conserving

surgery, those with lymph node metastasis and those who possess

large (≥5 cm) masses (2).

Radiotherapy induces double-stranded DNA breaks through ionizing

radiation, and as healthy cells have a stronger DNA repair ability,

radiotherapy typically targets and kills tumor cells (3). Although radiotherapy significantly

improves the prognosis of patients with malignant tumors, exposure

to radiation damages the skin. Radiation-induced skin injury (RSI)

is divided into two types: i) Acute RSI with skin desquamation,

necrosis, ulceration and hemorrhage; and ii) chronic RSI with

chronic ulceration, radiation-induced keratosis pilaris, capillary

dilatation, fibrosis and skin cancer (4). Radiation-induced non-melanoma skin

cancer (NMSC) occurs more frequently in patients undergoing

radiotherapy on the face, neck and head, while skin cancer induced

by postoperative radiotherapy for related breast cancers is rare

(5). In addition, RSI is described

as latent, progressive and persistent, and usually causes

irreversible damage to the microvessels and vascular endothelial

cells in the skin. Specifically, radiation-associated fibrosis

damages the lymphatic vessels and blood vessels in the irradiated

area, which can lead to skin ulcers and difficulties in wound

healing. It has been reported that 30% of patients who receive

radiotherapy to the breast or chest wall will develop severe skin

fibrosis (6). Patients with breast

cancer who undergo breast conserving surgery typically require

postoperative radiotherapy, which often results in side effects

that also affect the postoperative aesthetics of the patient. The

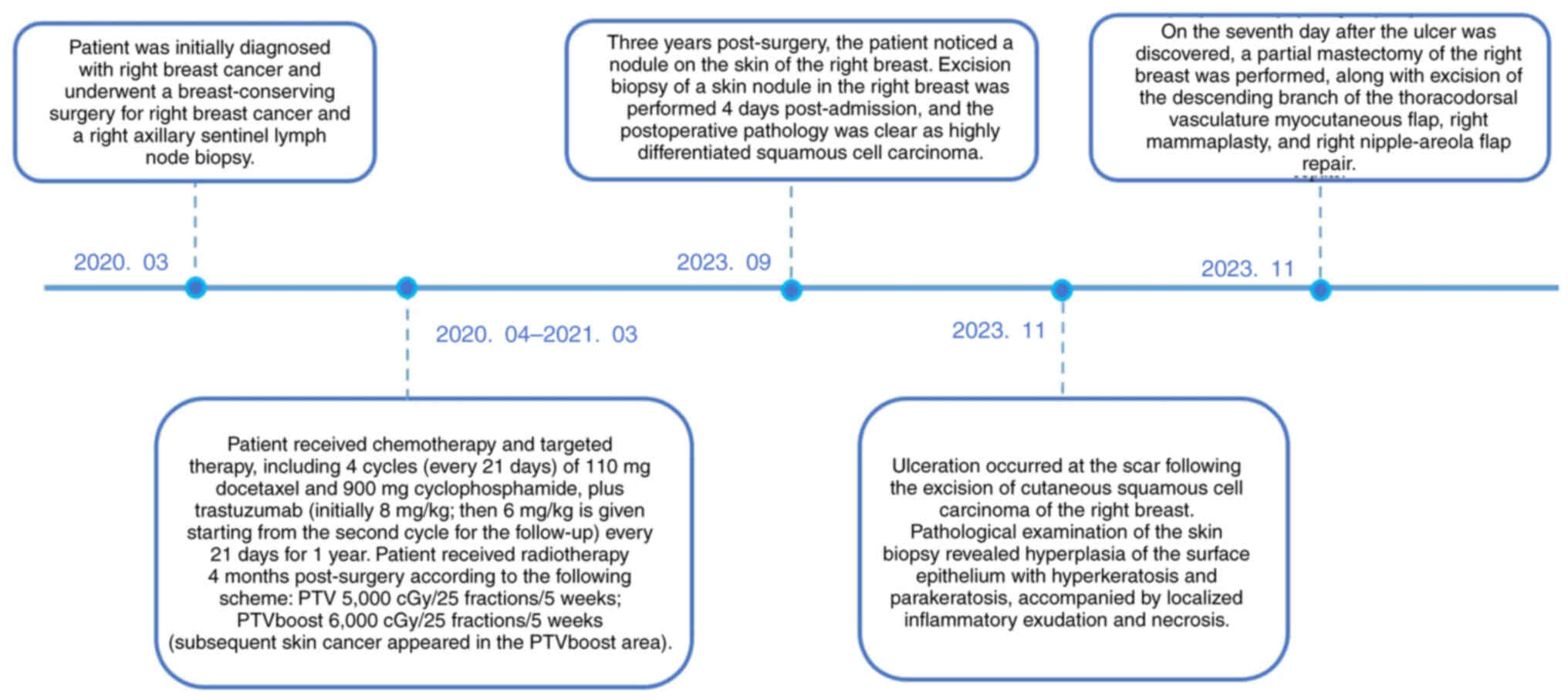

present case report describes the case of a patient with squamous

cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin induced after postoperative

radiotherapy for breast cancer (Fig.

1), and discusses the causes and solutions to the postoperative

wound healing difficulties for skin cancer.

Case report

Patient

A 43-year-old woman noticed a palpable nodule at the

9 o'clock position on the right breast in January 2020. In March

2020, the patient sought medical attention at the Affiliated

Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Zhanjiang, Guangdong,

China), where a breast core needle biopsy was performed, revealing

ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the right breast (the

pathological findings revealed cells with irregular nuclear size

and shape, increased chromatin, and the presence of cancer cells

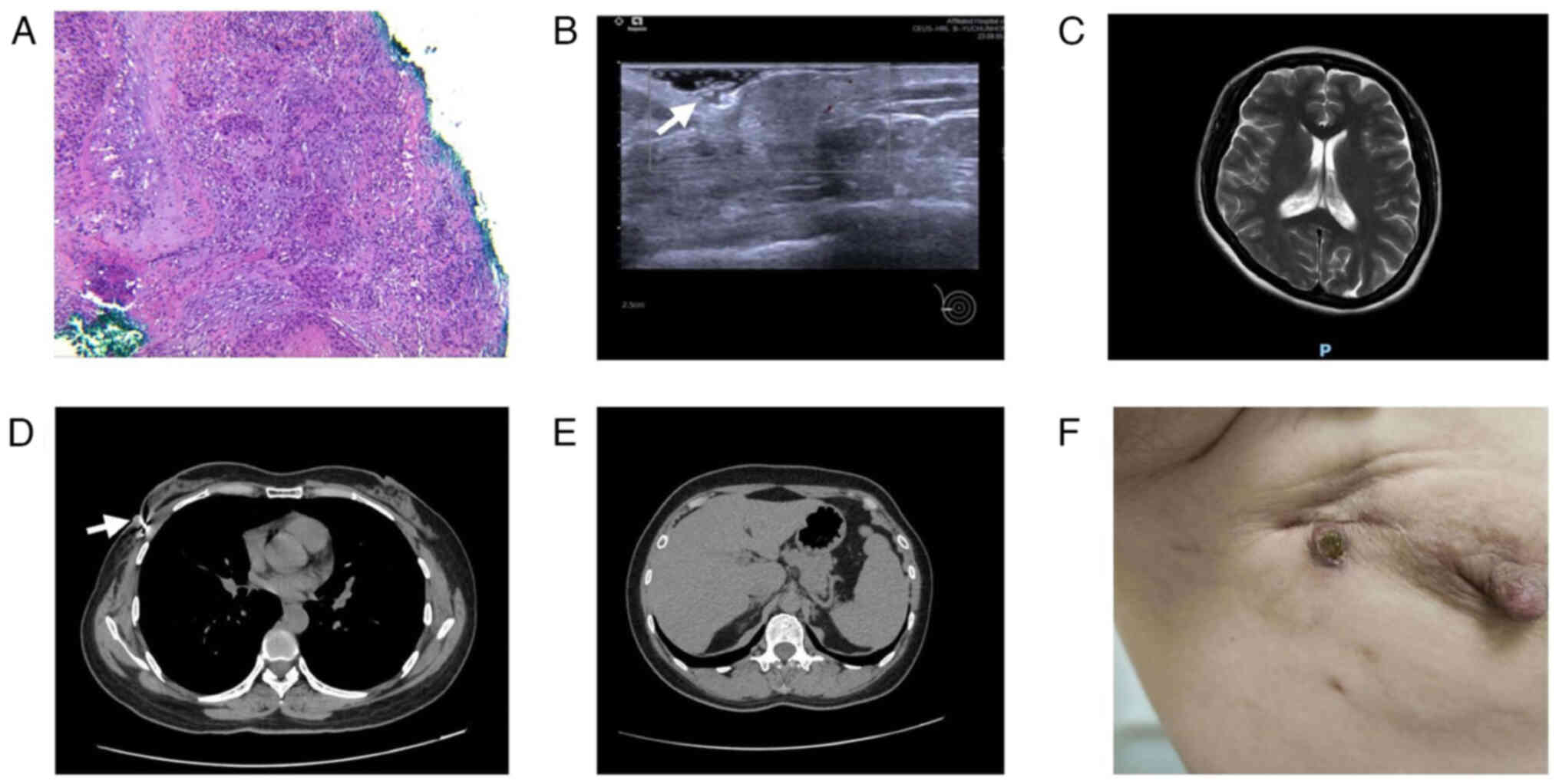

within the mammary ducts; Fig. 2A),

with focal invasion suspected. After 5 days, the patient underwent

simultaneous breast-conserving surgery for right-sided breast

cancer and a right axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy.

The results of the postoperative pathology led to a

diagnosis of invasive carcinoma of the right breast with ductal

carcinoma in situ, with the diameter of the invasive lesion

being 0.5 cm and no metastasis present in the sentinel lymph nodes

(0/6). The immunohistochemistry (IHC) results were as follows:

Estrogen receptor (ER) (no expression in the invasive carcinoma and

carcinoma in situ), progesterone receptor (PR) (no

expression in the invasive carcinoma and carcinoma in situ),

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (3+) and Ki-67 (50%

in the carcinoma in situ and 60% in the invasive carcinoma).

The patient was diagnosed with right breast invasive carcinoma with

ductal carcinoma in situ [pT1N0M0 stage IA with HER2

overexpression, according to the Eighth Edition of the AJCC Cancer

Staging Manual: Breast Cancer (7)]

at 6 days post-surgery. Based on the postoperative pathology, the

patient had indications for both chemotherapy and targeted therapy.

After surgery, the patient received chemotherapy and targeted

therapy, including 4 cycles of 110 mg docetaxel and 900 mg

cyclophosphamide, plus trastuzumab (initially 8 mg/kg, then 6 mg/kg

from the second cycle for the follow-up) every 21 days for 1

year.

According to the Chinese Society of Clinical

Oncology Breast Cancer diagnosis and treatment guidelines (2), patients who undergo breast-conserving

surgery require postoperative radiotherapy. The radiotherapy

modality for this patient was volumetric modulated arc therapy. The

patient received radiotherapy in July 2020 according to the

following scheme: Planning target volume (PTV), 5,000 cGy/25

fractions/5 weeks; PTVboost, 6,000 cGy/25 fractions/5 weeks

(subsequent skin cancer appeared in the PTVboost area). The patient

presented with erythema, dry flaky skin and a small amount of wet

flaking skin [grade 2; in accordance with the grading system

developed by The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group and The European

Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (8)] after radiotherapy, and was instructed

to keep their skin dry, protect it from light and prevent friction.

At 3 months post-radiotherapy, the skin erythema had resolved, and

the skin was only slightly dry, with no dry or wet flaking

observed. All treatments for the patient were completed at the

Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University. After the

completion of treatment, the patient did not require any additional

special treatment and only needed regular follow-up examinations.

Follow-ups were conducted every 3 months in the first and second

years, and every 6 months from the third year onward. No

abnormalities were detected during the follow-up period from March

2020 to July 2023.

At a total of 3 years post-surgery, the patient

complained of a skin nodule at the right breast scar, which was

noticed while taking a shower in July 2023, with no obvious

triggers. This condition persisted for 2 months. The surface of the

skin nodule was initially ulcerated and then gradually crusted

over. During this period, the patient did not visit the hospital

for medical care, nor was any treatment administered. In September

2023, breast ultrasonography at the Affiliated Hospital of

Guangdong Medical University showed an isoechoic nodule in the

right breast at the 9 o'clock direction of the surgical scar,

measuring ~1.1×0.9 cm in size [breast imaging-reporting and data

system class 4B, according to the second edition of the American

College of Radiology BI-RADS US (9); Fig.

2B]. There were no signs of local or distant metastases in the

head magnetic resonance imaging scans (Fig. 2C), or the chest (Fig. 2D) and upper abdomen (Fig. 2E) enhanced computed tomography

scans.

Physical examination results

A round raised nodule was observed at the scar in

the right breast, measuring ~1.1×0.9 cm in size with a hard texture

and unclear boundary. The nodule presented as a central black scab

with a dark red periphery, with no breakage or bleeding. There was

a hard texture to the surrounding skin and soft tissues, poor

mobility and no sense of tenderness. No obvious enlarged lymph

nodes were detected in the right axilla and the upper and lower

fossae of the clavicle (Fig.

2F).

Course of treatment and postoperative

pathology

In September 2023, the patient underwent excision

and biopsy of the right breast skin nodule due to the possibility

of breast cancer recurrence, which could not be ruled out. During

the operation, the nodule and surrounding 1 cm of skin tissue were

removed. The intraoperative frozen-section examination showed that

the right breast skin had focal ulcer formation, squamous

epithelial hyperplasia and inflammatory cell infiltration. The

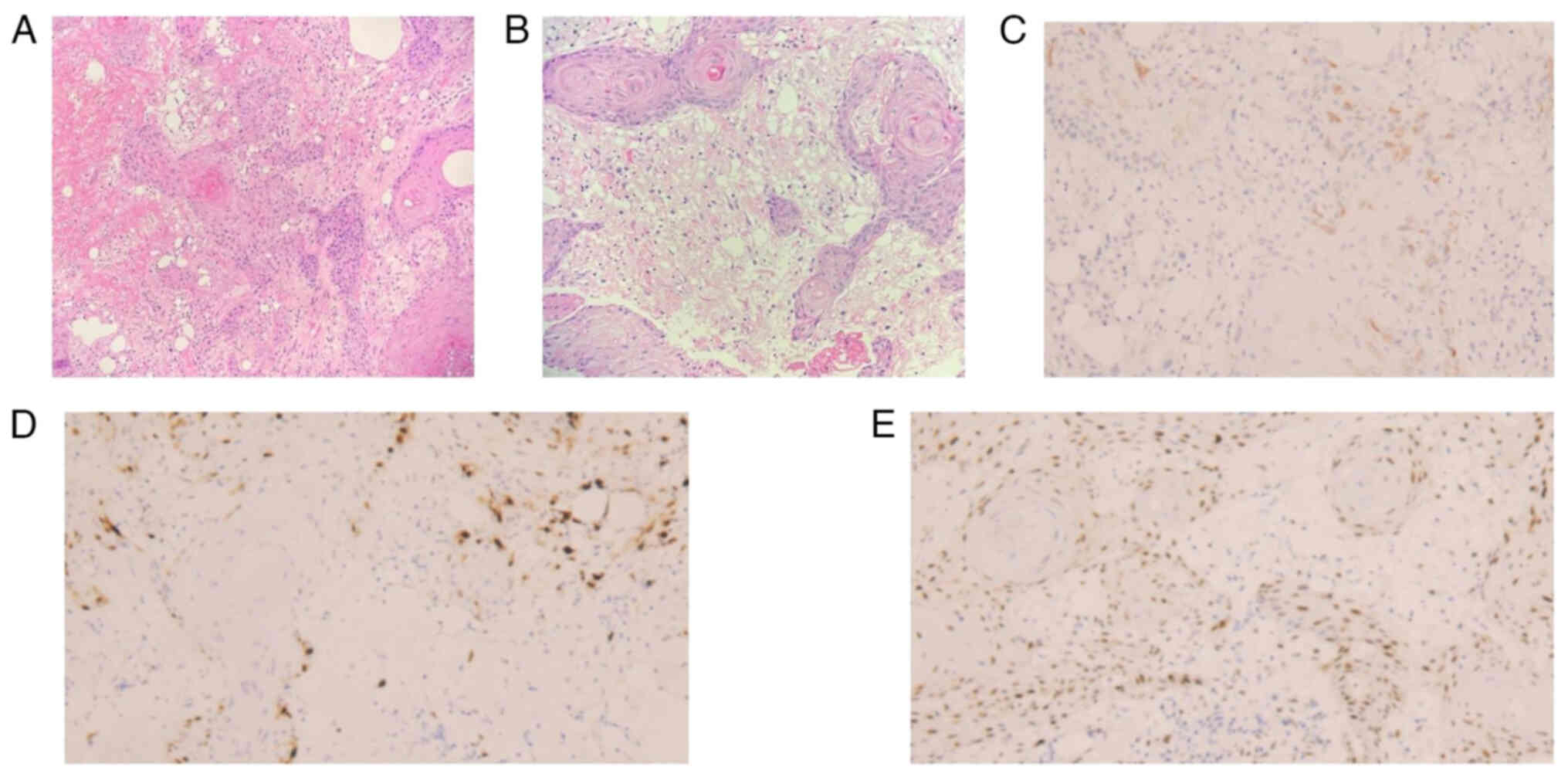

results of the postoperative routine pathology were as follows

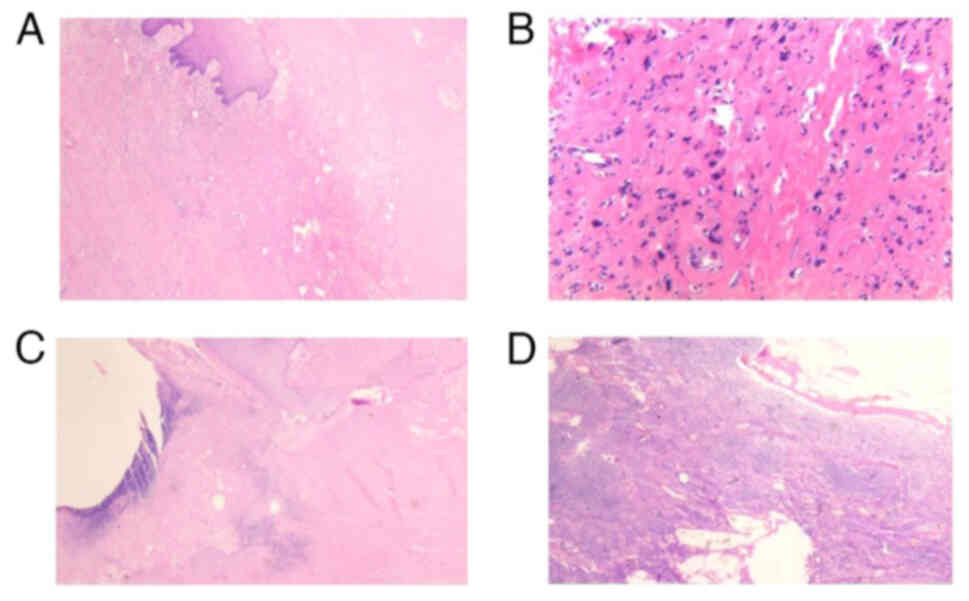

(Fig. 3A and B): The right breast

nodule was formed of skin tissue and the formation of a necrotic

ulcer was observed locally; the peripheral squamous epithelium had

significant hyperplasia with keratinization, and some of the

epithelium was scattered within the stroma. The results of the IHC

were as follows (Figs. 3 and

4): Insulin-like growth factor 2

mRNA-binding protein 3 IMP3(partial+), Ki-67(~30%), tumor protein

p53 (wild-type expression), tumor protein p63(+), cytokeratin

(CK)(+), CK5/6(+) and HER2(−). The combination of these results

were consistent with highly differentiated SCC, the surgical

horizontal resection margins and basal margins are negative. The

postoperative diagnosis was a follows: i) Skin SCC of the right

breast (pT1N0M0 stage I); and ii) after breast conserving surgery

for right breast cancer (pT1N0M0 stage IA HER2 overexpression

type).

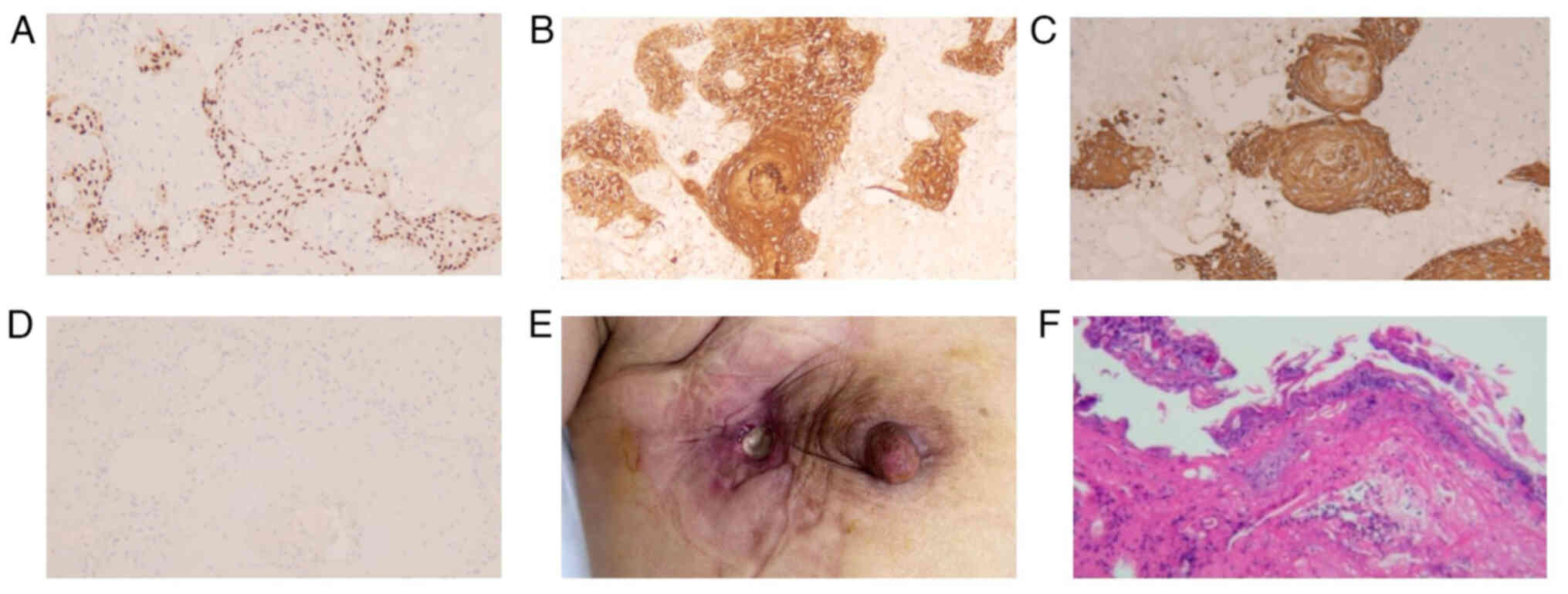

In November 2023, the patient identified an ulcer

located at the scar after the excision of the right breast skin

nodule (Fig. 4E), measuring ~2×1 cm

in size, that secreted a foul-smelling purulent fluid, with red,

swollen and painful surrounding skin. A skin biopsy (H&E

staining) indicated that the surface epithelium of the submitted

skin tissue was hyperplastic with hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis,

and local inflammatory exudation and necrosis (Fig. 4F). Considering that conservative

treatment of this ulcer is not effective, a partial mastectomy of

the right breast, an excision of the descending branch of the

thoracodorsal vasculature myocutaneous flap, a right mammaplasty

and a right nipple areola flap repair were performed 6 days after

the patient was admitted. The postoperative pathology demonstrated

that: i) The right breast skin ulcer had formed accompanied by

local tissue necrosis of the skin, hyaline degeneration and

inflammatory cell infiltration of the surrounding stroma, and that

large hyperchromatic deformed cells were observed in local areas

(Fig. 5A and B); ii) no tumor was

found in the upper, lower, inner, basal or incisional margin

tissues of the right breast submitted for examination during the

operation (Fig. 5C); and iii)

reactive hyperplasia was observed in one lymph node that was sent

for examination (Fig. 5D).

Surgical methods

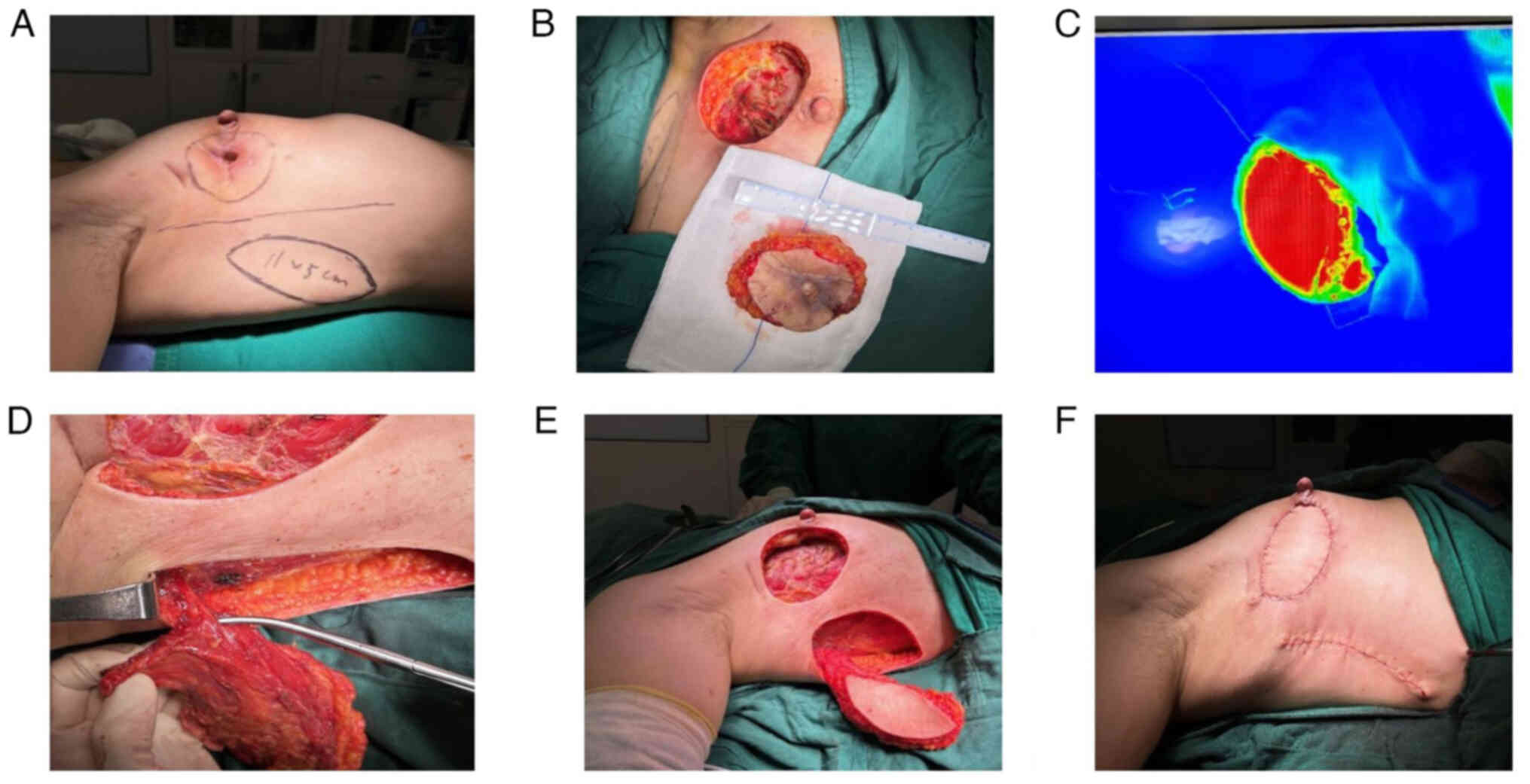

Prior to the operation, the size of the skin ulcer

surface at the 9 o'clock position on the right chest wall, the scar

tissue area around it and the fibrotic tissue after radiotherapy

were measured. A color Doppler ultrasound was used to locate the

position of the thoracodorsal vessels, and the location of the

descending branch flap of the thoracodorsal vessels was used as a

horizontal axis. A section ~10 cm below the axillary fold on the

right chest wall area was used as a fusiform flap with a length of

~11 cm and a width of ~5 cm (Fig.

6A). After demarcation, attention was paid to the tension of

the flaps on both sides to avoid the occurrence of skin flap

necrosis due to excessive tension.

Before the operation, gentian violet was used to

demarcate the incision range on the skin, that is, an oval incision

centered on the ulceration. The extent of the excision included

breast tissue and scar tissue in the outer quadrant of the breast,

including part of the chest muscle, measuring 5×8 cm. After the

incision, the remaining necrotic tissue and deep surface underwent

debridement, and the bleeding tissue was exposed without

abnormality (Fig. 6B).

Subsequently, the thoracodorsal vascular muscle flap

was separated as follows: i) The skin and subcutaneous tissues were

incised sequentially along the preoperative right lateral thoracic

wall to the surface of the latissimus dorsi muscle. ii) the main

trunk of the thoracodorsal vessels was exposed after exploration,

and then the descending branches of the thoracodorsal vessels were

found along its course. The surrounding tissues and small branch

vessels were separated, paying attention to the position of the

thoracodorsal nerves during the process to avoid injury. iii) The

flap of the descending branch of the thoracodorsal vessels and a

small portion of the latissimus dorsi muscle were separated

together, and after separation, indocyanine green was injected

intravenously to clarify the flap blood flow (Indocyanine Green

Fluorescence Imaging System; Fig. 6C

and D). A suitable subcutaneous tunnel was made between the

breast remnant cavity and the lateral descending thoracodorsal

vascular muscle flap. The size of this tunnel was large enough to

avoid vascular distortion and compression (Fig. 6E). The free descending thoracodorsal

vascular flap was transferred to the breast remnant cavity and then

the flap was plasticized and cut according to the trauma. The flap

was fixed on the right side of the breast defect by absorptive

suture and the retained flap was sutured with the skin to reshape

the breast (Fig. 6F).

Post-operative follow-up

At the 6-month postoperative follow-up in May 2024,

the patient exhibited successful wound healing of the flap and did

not complain of discomfort. The flap showed no signs of

hyperpigmentation or edema (Fig.

7). The patient's last follow-up was in December 2024, and no

new tumors were found during the examination.

H&E staining and

immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin

at room temperature for 12 h. After tissue dehydration and

clearing, the samples were immersed in melted paraffin at 60°C

twice, each for 1 h. Sections were cut to 5 µm, dewaxed and

subjected to H&E staining. H&E staining were performed at

room temperature for 5 min, and the slides were observed under an

optical microscope.

For IHC, the following primary antibodies were

applied: Anti-ER (ready-to-use antibody; catalog no.: 790-4324;

incubation for 32 min; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), anti-PR

(ready-to-use antibody; catalog no. 790-2223; incubation for 24

min; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), anti-HER2 (ready-to-use antibody;

catalog no. 790-2991; incubation for 8 min; Roche Diagnostics

GmbH), anti-IMP3 (dilution, 1:100; catalog no. MAB-0725; incubation

for 40 min; Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.),

anti-Ki-67 (ready-to-use antibody; catalog no. 790-4286; incubation

for 16 min; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), anti-p53 (ready-to-use

antibody; catalog no. 790-2912; incubation for 32 min; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), anti-p63 (dilution, 1:150; catalog no. MAB-0674;

incubation for 32 min; Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co.,

Ltd.), CK (dilution, 1:100; catalog no. A1901; incubation for 30

min; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science & Technology Co.,Ltd.) and

CK5/6 (dilution, 1:150; catalog no. MAB-0692; incubation for 36

min; Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.). The

incubations were performed on the Roche Ventana automated IHC

platform at 36°C. Subsequently, the secondary antibody from the

UltraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (ready-to-use; catalog no.

760-500; Roche Diagnostics GmbH) was automatically incubated using

the Ventana platform for 8 min. Streptavidin-HRP (ready-to-use;

catalog no. 760-500; Roche Diagnostics GmbH) was added and

automatically incubated on the Ventana platform for 10 min.

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (ready-to-use; catalog no. 760-700; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH) was used as the chromogenic substrate and

automatically developed on the Ventana platform for 8 min. Finally,

the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin for 30 sec, and the

slides were observed under an optical microscope (Olympus

Corporation).

Discussion

The pathogenesis of cutaneous SCC (cSCC) mainly

includes ultraviolet radiation, human papilloma infection, TP53

gene mutation, chronic scarring, transplantation-related immunity,

ionizing radiation and low-dose arsenic exposure. Among them,

prolonged ultraviolet radiation is the most common pathogenesis of

cSCC, which is mainly found in exposed areas such as the scalp,

face and backs of the hands (10).

In the present case, the diagnosis of the patient

needed to be differentiated from other diseases. Firstly, the

patient did not have a history of long-term ultraviolet (UV)

radiation exposure on the chest wall, an area that is less exposed

to UV radiation compared with other parts of the body. Therefore,

the likelihood of primary cSCC occurring at this location was low.

Additionally, the patient had a clear history of radiotherapy and

presented with post-radiation skin fibrosis, which further

supported the exclusion of primary cSCC. Secondly, the patient had

a previous history of breast cancer. When the skin nodule was first

detected, the possibility of breast cancer recurrence or metastasis

could not initially be ruled out. However, based on the

postoperative pathological findings, the tumor cells were arranged

in nests or sheets with the presence of keratin pearls. IHC showed

positive expression of CK5/6 and p63, indicating a squamous cell

origin, which is inconsistent with the pathological features of

breast cancer. Additionally, breast cancer recurrence or metastasis

is often accompanied by other metastatic lesions, but no other

abnormalities were found in the patient's examination results.

Therefore, the possibility of breast cancer recurrence or

metastasis was ruled out. Thirdly, the patient developed SCC of the

skin in the irradiated area 3 years after radiotherapy, and it is

noteworthy that this nodule was located in a scar. Cases of

malignant transformation of scar tissue have been previously

reported (11) and this condition

is termed a Marjolin ulcer (MU) (12). In patients with MU, the primary

cause of skin SCC is due to recurrent ulceration and persistent

irritation of a non-healing wound. MU therefore often occurs in

post-burn scarring and is often more aggressive, with research

results showing that 20–36% of patients have lymph node metastasis

at the time of initial diagnosis (13). The clinical presentation of the

present study patient was similar to that of MU. However, the

patient did not present with ulceration or poor healing of the scar

after postoperative radiotherapy. The patient's skin cancer was a

well-differentiated cSCC without regional lymph node metastasis,

which differs from the pathological characteristics of MU. In

addition, the skin nodule initially found in this case was only

ulcerated for a short period of time and gradually scabbed over.

Therefore, it was hypothesized that the cSCC of the patient was not

as a result of malignant transformation of the scar tissue.

There have been multiple previous reports on

radiation-induced skin cancer. In 1995, Landthaler et al

(14) retrospectively analyzed 612

radiation sites from 522 patients and observed 12 cases of basal

cell carcinoma (2.0%) and 9 cases of SCC (1.5%). Subsequently, a

prospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort,

which included 13,132 childhood cancer survivors, identified NMSC

in 213 patients. Among these, 90% had received radiotherapy, and

90% of the tumors developed within the irradiated field (15). Basal cell carcinoma and SCC are the

two main types of post-radiotherapy cutaneous malignancy, with a

long latency period reported and being described as a late

complication of ionizing radiation. Radiation-induced skin cancers

can develop at any time from 2–65 years after radiation exposure

(16). Although the probability of

malignancy induced by radiation therapy is low, a study found a

positive correlation between radiotherapy for breast cancer and

cutaneous melanoma (17). A

subsequent analysis by Rezaei et al (18), that included 875,880 patients with

breast cancer (50.3% of whom received radiotherapy), found that

patients who were treated with radiotherapy were more likely to

develop skin cancer than those who did not receive radiotherapy (8%

increase). Although this study did not include SCC or basal cell

carcinoma of the skin, statistical analysis revealed that melanoma

and angiosarcoma were the most common types of non-keratinocytic

skin cancer among patients with breast cancer following

radiotherapy or other treatments. In addition, a review of relevant

literature also identified case reports of NMSC induced by

postoperative radiotherapy for breast cancer, with pathological

results consistently showing SCC (19–21).

In the case reported by Loveland-Jones et al (19), the patient had undergone lumpectomy

and whole breast radiation therapy. At 9 years after surgery, a

non-healing ulcer of the right nipple was detected. The patient

underwent a wide excision of the nipple-areolar complex, and

pathological examination revealed a moderately to poorly

differentiated invasive SCC. IHC showed positive expression results

for CK5/6, p63 and CK, and negative expression results for ER, PR

and HER2. The surgical approach in this case was consistent with

that of the present patient, and the SCC also developed within the

radiation field. Similarly, IHC in this case showed positive

expression of CK5/6 and p63, which are associated with SCC, and

lack of expression of HER-2, which is associated with breast

cancer. Therefore, based on the aforementioned reasons, we consider

that the cSCC in the present patient was induced by radiation

therapy.

With regard to the mechanism of radiation-induced

skin cancer, firstly, radiation causes skin cancer mainly due to

direct and indirect DNA damage, reactive oxygen species (ROS)

production and local immune dysregulation. Cellular damage due to

excessive ROS production is the result of interference with cell

membranes, proteins and DNA, which alters the overall biological

activity. As a result of these effects, oxidative products are

formed that have mutagenic properties, which initiates the

oncogenic process within the epidermal cells (4). Secondly, chronic stimulation is also a

recognized theory, as research has found that inflammation is

involved in the development of skin cancer (22). For example, chronic inflammatory

stimulation due to radiation dermatitis and radioactive ulcers

after radiotherapy is both a carcinogenic and a cancer-promoting

factor. van Vloten et al (23) followed up 360 patients who had

received radiotherapy for benign diseases of the head and neck, and

found skin tumors in 21 of them. In 8 out of the 21 patients, 10

skin carcinomas were detected at recall. The study also concluded

that the severity of radiation dermatitis was associated with a

higher incidence of skin cancer. Furthermore, the dry contracture

of the skin in the radiation area and the small amount of

pigmentation observed in this area, as described in the present

case report 3 years after radiotherapy, is in line with the

clinical manifestations of chronic radiation dermatitis. Therefore,

it was concluded that the patient described in the present case

report developed SCC of the skin after radiotherapy, which may also

be related to long-term stimulation of chronic radiation

dermatitis. The diagnostic criteria for radiotherapy-induced skin

cancer and malignant tumors induced by radiotherapy converge can be

summarized as follows: i) A definite history of radiation exposure;

ii) tumors occurring at the irradiated site; iii) a long latent

period; and iv) pathological and histological confirmation or

histological types different from the primary tumor (24).

Surgery is the primary treatment for skin SCC. For

patients with early stage skin cancer, the radical cure rate of

surgical resection can reach up to 95%; this consists of standard

excision, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) and curettage and

electrocautery, with standard excision being the most commonly used

(25). For low- and high-risk

cSCCs, radial resection margins of 4 and 6 mm, respectively,

demonstrated 95% oncological clearance (25). For low-risk cSCC, National

Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that excision

margins are 4–6 mm of the normal skin and that the margins are

pathologically negative (10). For

high-risk cSCC with multiple risk factors, there is insufficient

clinical data and no definitive criteria for peripheral margins,

but relevant studies have found that MMS is more effective than

standard excision for high-risk cSCC (26). The main non-surgical treatment

modalities for cSCC are radiotherapy, chemotherapy, photodynamic

therapy (PDT) and cryotherapy (27). Among them, cryotherapy or PDT are

only suitable for low-risk skin cancers without a clear

histological diagnosis and proof of tumor clearance, while

radiotherapy and chemotherapy are mostly used for patients with

advanced cancers.

In the present case report, the skin nodule of the

patient appeared on the right side of the postoperative scar from

breast cancer surgery. The possibility of recurrence of breast

cancer could not be excluded; however, combined with the wishes of

the patient and the circumstances, surgical excision and

intraoperative frozen section pathology were performed. In

addition, the results of intraoperative frozen pathology only

described squamous epithelial hyperplasia, and did not diagnose SCC

of the skin clearly. Therefore, considering the limitations of the

intraoperative frozen pathology and the fact that the patient had a

history of radiotherapy, a standard excision of skin cancer was

performed, and ~1 cm of normal skin around the skin nodule was

excised. This was confirmed to be cSCC by postoperative routine

pathology, and there was no tumor residue on the margins of the

incision.

A total of 20 days after the excision of the skin

SCC, the patient developed a wound ulcer. Therefore, the

possibility of tumor remnants could not be excluded, and a biopsy

of the skin tissue was performed. The results of the biopsy

indicated that only skin ulcer formation had occurred, and it was

hypothesized that the main cause of the ulcers was RSI after

radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy-induced dermatofibrosis is a chronic

and irreversible disease that occurs weeks to years after radiation

exposure and is characterized by changes in skin appearance, loss

of skin elasticity and contractures, and hardness of the skin that

is difficult to pinch and crease, accompanied by capillary

dilatation, pain and itching. Radiation-associated dermatofibrosis

is also accompanied by damage to the vascular system, which is

characterized by a decrease in the density of the microvascular

network and vascular morphological changes (28). Therefore, it was considered that

there were two main reasons for the poor wound healing in the

patient described in the present case report. Firstly, the

radiation damage destroyed the blood vessels and thus led to poor

blood flow in the flap in this area, thus making it difficult to

heal. Secondly, the radiation-related fibrosis led to high tension

at the flap on both sides after the tumor resection, which

ultimately led to the poor healing outcome. A previous study showed

that early aggressive management of chronic non-healing wounds and

peripheral flap grafting after excision of unstable scar tissue can

improve the prognosis of patients with cSCC (29). Therefore, in the present study, part

of the right breast where the ulcer had formed was excised and a

free flap repair was performed.

The common flaps for this type of chest wall

reconstruction are the latissimus dorsi muscle flap, localized

arbitrary flap and rectus abdominis muscle flap (30). However, in the present study, due

the condition of the patient and the extent of the right

mastectomy, the descending thoracodorsal vascular flap was selected

for the repair of the chest wall. The thoracodorsal vascular flap

is also often used for reconstruction after breast-conserving

surgery for breast cancer (31),

and it must be noted that its use in the repair in a variety of

soft-tissue defects has improved results (32). Furthermore, as the patient in the

present study had undergone breast-conserving surgery in the past,

and the amount of subcutaneous fat was insufficient, the descending

branches of the thoracodorsal vascular musculocutaneous flap were

selected to repair the defect. The advantages of this type of

musculocutaneous flap were firstly that the location of the

incision, namely the lateral chest wall, was relatively hidden, and

there was no need to change the position of the patient during the

operation. Secondly, most of the latissimus dorsi muscle was

preserved in our case, which reduced the likelihood of hematoma in

the back and shoulder joint dysfunction, and there were fewer

complications in the donor area. It must be noted that the

thoracodorsal vascular flap has limitations, including the

possibility of mutation of the branches emanating from the

thoracodorsal vascular, the limited width of the flap and the

time-consuming intraoperative fine separation (33,34),

However, this type of repair is simpler than other flaps, has fewer

postoperative complications, and can be used in other patients with

chest wall skin cancer or localized chest wall ulcers after

radiotherapy. In the present case report, the breast shape of the

patient was improved while the patient underwent flap repair using

the descending branches of the thoracodorsal vascular

musculocutaneous flap. Radiotherapy has become a key part of

postoperative treatment for breast cancer, and although SCC of the

skin is rare after radiotherapy for breast cancer, physicians

should remain vigilant. The area receiving the radiotherapy will

have a postoperative scar and the side effects of radiotherapy can

induce skin cancer. Therefore, a biopsy should be performed as

early as possible to clarify the pathology and any follow-up

treatment. In addition, in view of the poor wound healing described

in the present case, radiotherapy may lead to the occurrence of

skin fibrosis. As there is no effective prevention and treatment

method for radiation fibrosis, immediate flap transfer repair

should be considered at the time of surgery, especially for those

patients who need surgical excision for skin cancer after

breast-conserving surgery, in order to reduce the risk of adverse

events and to improve the appearance of the breasts while obtaining

improved therapeutic effects.

Finally, RSI has a long latency period and therefore

should be prevented early. With the development of radiotherapy

technology, intensity modulated radiation therapy, volumetric

modulated arc therapy, helical tomotherapy, fixed field tomotherapy

and other treatment modalities in clinical practice, research has

found that the correct choice of radiotherapy modality can

effectively reduce the side effects associated with radiotherapy

(35,36). As radiotherapy-related skin damage

can lead to skin cancer, and despite certain treatments delaying or

reducing the risk of radiation-induced fibrosis (RIF), the key to

preventing RIF is to reduce the radiation dose to exposed healthy

skin areas. Future advancements in radiotherapy should focus on

improving targeting precision and minimizing radiation exposure to

healthy tissues, thereby enhancing patient quality of life.

Radiotherapy is a primary cancer treatment; however,

relevant measures must be taken to prevent RSI and reduce the

incidence of adverse reactions. Drugs that can aid this must be

further researched and applied clinically. In addition, rational

selection of radiotherapy techniques, individualized design, and

early use of relevant drugs to treat and prevent chronic

radioactive skin injury must be implemented, regardless of the

severity of the RSI. Finally, patients should be followed up for a

long period of time after radiotherapy. If skin nodules, ulcers or

other chronic suspected wounds develop, biopsies should be

performed early to exclude the possibility of malignant lesions.

Any required follow-up treatment should be carried out as soon as

possible, and the feasibility of surgical excision of the patient

should be considered comprehensively based on the condition of the

skin condition. In the future, in addition to the more commonly

used surgical interventions, improved treatment options should be

further explored.

In conclusion, radiotherapy can lead to the

development of skin cancer, and its related skin injury may bring

difficulties to the treatment of skin cancer induced after

radiotherapy. Therefore, during radiotherapy, more attention should

be paid to the treatment of RSI. In addition, following

radiotherapy, more attention should be paid to the skin condition

of the area where radiotherapy was received, in addition to the

postoperative recurrence and wound recovery. If skin cancer has

developed after radiotherapy, a comprehensive evaluation should be

performed, and if surgical resection of the tumor is feasible, a

simple flap repair or reconstruction surgery should be considered

immediately after the skin cancer is resected, as described in the

present study, to avoid the occurrence of adverse events.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Guangdong General Colleges and

Universities Characteristic and Innovative Projects (grant no.

2021KTSCX037).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YQZ contributed to conception and design of the case

report. JWL and PQ contributed to data collection and analysis. SCH

and ZMY advised on patient treatment and performed the surgery. ZZL

and MY obtained medical images (e.g. MRI, CT and ultrasound), YYT,

CYC and ZZL contributed to data analysis and interpretation. YYT,

SCH, PQ, ZMY, CYC, MY, ZZL, JWL and YQZ contributed to manuscript

writing and final approval of the manuscript. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. SCH and YQZ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Zhanjiang,

China; (approval no. PJKT2024-116).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

accompanying identifiable images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li J, Hao C, Wang K, Zhang J, Chen J, Liu

Y, Nie J, Yan M, Liu Q, Geng C, et al: Chinese society of clinical

oncology (CSCO) breast cancer guidelines 2024. Transl Breast Cancer

Res. 5:182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ramseier JY, Ferreira MN and Leventhal JS:

Dermatologic toxicities associated with radiation therapy in women

with breast cancer. Int J Womens Dermatol. 6:349–356. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu C, Wei J, Wang X, Zhao Q, Lv J, Tan Z,

Xin Y and Jiang X: Radiation-induced skin reactions: Oxidative

damage mechanism and antioxidant protection. Front Cell Dev Biol.

12:14805712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cuperus E, Leguit R, Albregts M and

Toonstra J: Post radiation skin tumors: Basal cell carcinomas,

squamous cell carcinomas and angiosarcomas. A review of this late

effect of radiotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 23:749–757. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, Momeni A,

Longaker MT and Wan DC: Radiation-induced skin fibrosis:

Pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics.

Ann Plast Surg. 83 (4S Suppl 1):S59–S64. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Giuliano AE, Edge SB and Hortobagyi GN:

Eighth edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: Breast cancer.

Ann Surg Oncol. 25:1783–1785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cox JD, Stetz J and Pajak TF: Toxicity

criteria of the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) and the

European organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC).

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 31:1341–1346. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Spak DA, Plaxco JS, Santiago L, Dryden MJ

and Dogan BE: BI-RADS® fifth edition: A summary of

changes. Diagn Interv Imaging. 98:179–190. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Work Group and Invited Reviewers, . Kim

JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, Moyer J, Olenecki T and Rodgers P:

Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell

carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 78:560–578. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chiriac AE, Betiu M, Brzezinski P, Di

Martino Ortiz B, Chiriac A, Foia L and Azoicai D: Malignant

degeneration of scars. Cancer Manag Res. 12:10297–10302. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Da Costa JC III: Carcinomatous changes in

an area of chronic ulceration, or Marjolin's ulcer. Ann Surg.

37:496–502. 1903.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Saaiq M and Ashraf B: Marjolin's ulcers in

the post-burned lesions and scars. World J Clin Cases. 2:507–514.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Landthaler M, Hagspiel HJ and Braun-Falco

O: Late irradiation damage to the skin caused by soft X-ray

radiation therapy of cutaneous tumors. Arch Dermatol. 131:182–186.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Perkins JL, Liu Y, Mitby PA, Neglia JP,

Hammond S, Stovall M, Meadows AT, Hutchinson R, Dreyer ZE, Robison

LL and Mertens AC: Nonmelanoma skin cancer in survivors of

childhood and adolescent cancer: A report from the childhood cancer

survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 23:3733–3741. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Meibodi NT, Maleki M, Javidi Z and Nahidi

Y: Clinicopathological evaluation of radiation induced basal cell

carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 53:137–139. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Goggins W, Gao W and Tsao H: Association

between female breast cancer and cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer.

111:792–794. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Rezaei SJ, Eid E, Tang JY, Kurian AW,

Kwong BY and Linos E: Incidence of nonkeratinocyte skin cancer

after breast cancer radiation therapy. JAMA Netw Open.

7:e2416322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Loveland-Jones CE, Wang F, Bankhead RR,

Huang Y and Reilly KJ: Squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple

following radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ: A case

report. J Med Case Rep. 4:1862010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yokota T, Roppongi T, Kanno K, Tsutsumi H,

Sakamoto I and Fujii T: Radiation-induced squamous cell carcinoma

of the chest wall seven years after adjuvant radiotherapy following

the surgery of breast cancer: A case report. Kyobu Geka.

53:1133–1136. 2000.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kodama K, Doi O, Higashiyama M, Yokouchi

H, Noguchi S and Koyama H: Chemo-thermotherapy of radiation-induced

squamous cell carcinoma in anterior chest wall. Kyobu Geka.

45:917–920. 1992.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Voiculescu V, Calenic B, Ghita M, Lupu M,

Caruntu A, Moraru L, Voiculescu S, Ion A, Greabu M, Ishkitiev N and

Caruntu C: From normal skin to squamous cell carcinoma: A quest for

novel biomarkers. Dis Markers. 2016:45174922016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

van Vloten WA, Hermans J and van Daal WA:

Radiation-induced skin cancer and radiodermatitis of the head and

neck. Cancer. 59:411–414. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cahan WG, Woodard HQ, Higinbotham NL,

Stewart FW and Coley BL: Sarcoma arising in irradiated bone: Report

of eleven cases. 1948. Cancer. 82:8–34. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Skulsky SL, O'Sullivan B, McArdle O,

Leader M, Roche M, Conlon PJ and O'Neill JP: Review of high-risk

features of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and discrepancies

between the American joint committee on cancer and NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. Head Neck. 39:578–594. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Hill D,

Richards S and Paver R: Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated

with Mohs micrographic surgery in Australia I. Experience over 10

years. J Am Acad Dermatol. 53:253–260. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W,

Stanton W and Leonardi-Bee J: Interventions for non-metastatic

squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Systematic review and pooled

analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 347:f61532013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang X, Ren H, Guo X, Hu C and Fu J:

Radiation-induced skin injury: Pathogenesis, treatment, and

management. Aging (Albany NY). 12:23379–23393. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Iqbal FM, Sinha Y and Jaffe W: Marjolin's

ulcer: A rare entity with a call for early diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep.

2015:bcr20142081762015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fujioka M: Surgical Reconstruction of

radiation injuries. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 3:25–37. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li SQ, Zheng ZF, Li H, Zhang JF, Zheng Y

and Lin LS: Clinical study on the thoracodorsal artery perforator

flap in breast-conserving reconstruction of T2 breast cancer. Surg

Innov. 31:16–25. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sui X, Qing L, Yu F, Wu P and Tang J: The

versatile thoracodorsal artery perforator flap for extremity

reconstruction: From simple to five types of advanced applications

and clinical outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res. 18:9732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yang LC, Wang XC, Bentz ML, Fang BR, Xiong

X, Li XF, Lu Q, Wu Q, Wang RF, Feng W, et al: Clinical application

of the thoracodorsal artery perforator flaps. J Plast Reconstr

Aesthet Surg. 66:193–200. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Homsy C, Theunissen T and Sadeghi A: The

thoracodorsal artery perforator flap: A powerful tool in breast

reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 150:755–761. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chan TY, Tan PW, Tan CW and Tang JI:

Assessing radiation exposure of the left anterior descending

artery, heart and lung in patients with left breast cancer: A

dosimetric comparison between multicatheter accelerated partial

breast irradiation and whole breast external beam radiotherapy.

Radiother Oncol. 117:459–466. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang Q, Liu J, Ao N, Yu H, Peng Y, Ou L

and Zhang S: Secondary cancer risk after radiation therapy for

breast cancer with different radiotherapy techniques. Sci Rep.

10:12202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|