Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO),

colorectal cancer (CRC) is a malignant neoplasm that develops when

normal epithelial cells lining the large intestine undergo

malignant transformation and give rise to adenocarcinoma (1). CRC is the third leading cause of

cancer-related mortality (1) and

accounted for 576,858 deaths and 1.15 million new cases in 2020,

based on the report of GLOBOCAN 2020 database for 185 countries and

36 cancer types (2). The number of

new cases of CRC is projected to rise to 1.92 million by 2040

(3).

According to previous statistics, CRC has a

mortality rate of 10.5% in men and 9% in women, making it the

second leading cause of cancer-related death in both sexes in

Jordan (4), and the 5-year survival

rate is 22.6% (5). Thus, to improve

survival in patients with advanced-stage disease, a further

understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying CRC

pathogenesis and the application of targeted therapies in clinical

practice is required.

The pathophysiology of CRC is complex and

multifaceted, leading to the widespread acceptance that the causes

are heterogeneous (6). Changes at

the genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic and metabolomic levels all

serve key roles in the etiology and progression of CRC, and our

understanding of this disease remains limited (7). Different molecular subtypes have

distinct clinical and pathological characteristics, and varying

responses to cytotoxic and targeted therapies. In metastatic CRC

(mCRC), it is currently advised that thorough RAS and v-Raf Murine

Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog B (BRAF) mutation testing should be

performed before treatment (8). RAS

proteins are GTPases and there are three subtypes: Kirsten rat

sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) and Harvey rat sarcoma viral

oncogene homolog were discovered in 1982 (9), whereas neuroblastoma RAS viral

oncogene homolog (NRAS) was not discovered until 1983 (10). NRAS mutations are infrequent,

occurring in ~4% of CRC cases (11). NRAS mutant tumors are predominantly

situated in the proximal colon and are more prevalent among older

patients (11). KRAS mutations are

linked to right-sided primary CRC, whereas NRAS mutations are more

prevalent in left-sided CRC, particularly in women (12). The prognosis for patients with RAS

mutations is worse compared with that of patients with a wild-type

RAS genotype. KRAS and NRAS mutations exert differing effects on

survival in mCRC; the prognosis for the aggressive NRAS mutant

molecular subgroup is unfavorable (13).

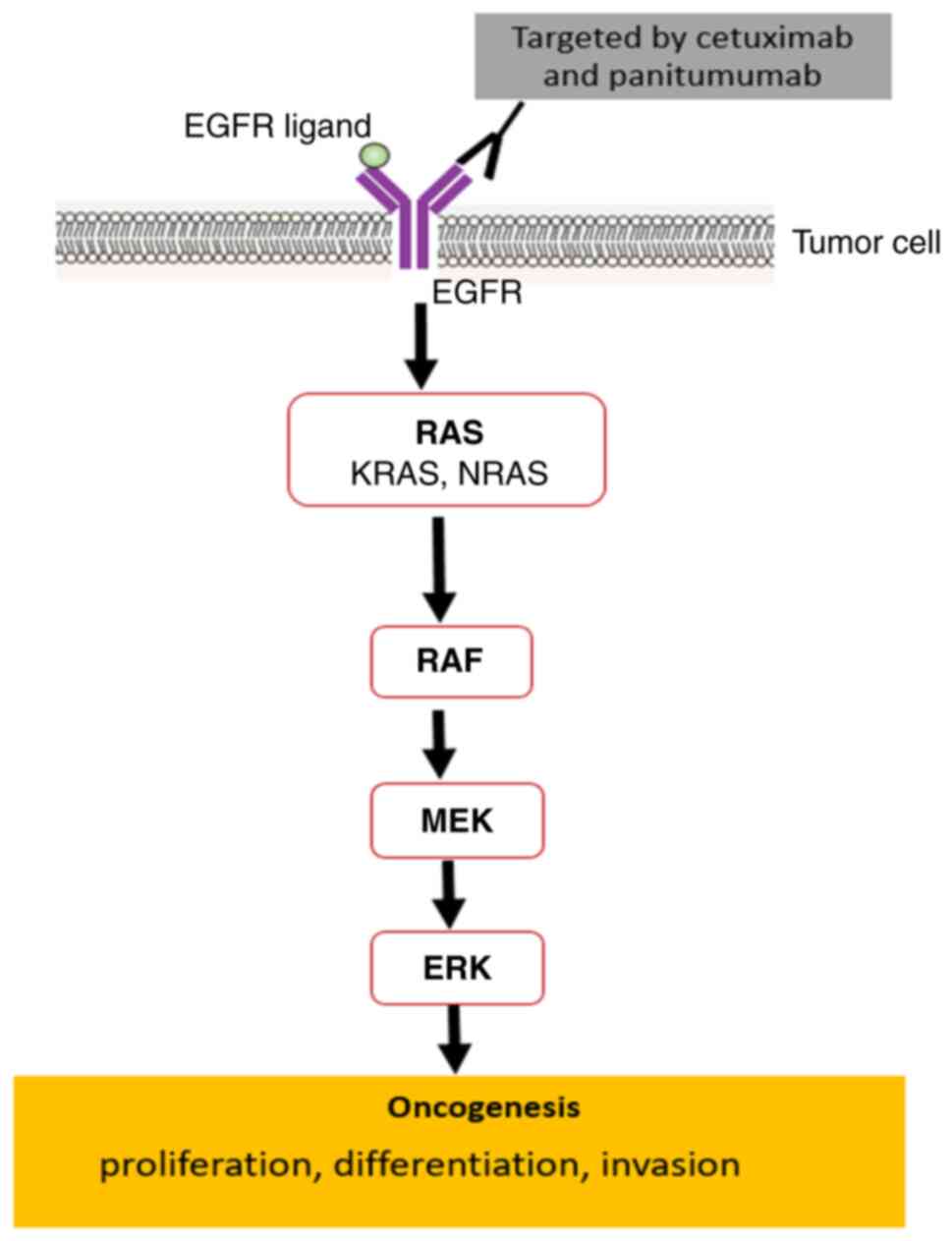

KRAS is a component located downstream of the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway. KRAS

operates as an intracellular signal transducer by linking signals

from cell surface receptors to intracellular targets that control

important functions for tumor progression, including proliferation,

differentiation and apoptosis (Fig.

1) (14).

The development of CRC is associated with the

presence of activating mutations in oncogenes; mutant RAS proteins

elicit downstream oncogenic signaling, resulting in tumor cells

acquiring aggressive characteristics such as increased cell mitosis

(15). Activating mutations in the

KRAS gene are associated with ~45% of colorectal malignancies, and

a large proportion of mutations are found in codons 12 (30%) and 13

(8%) of exon 2 (16). The presence

of these somatic mutations leads to continuous activation of the

EGFR pathway, resulting in the acquisition of resistance to

anti-EGFR therapies, including panitumumab or cetuximab (17). Previous research has demonstrated

that in mCRC, KRAS mutations in exon 2 were not associated with any

therapeutic benefit when using anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies

(18). Consequently, the use of

cetuximab and panitumumab as anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies is

restricted to patients with wild-type RAS mCRC and therefore, this

mandates that RAS mutation screening should be conducted to

determine whether anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies should be

recommended. It has been demonstrated that KRAS mutations predict a

worse prognosis for patients with CRC (19). The FOCUS trial reported that the

presence of activating mutations in the KRAS and BRAF oncogenes is

associated with shorter overall survival. Patients with a KRAS

mutation had significantly worse overall survival compared with

patients with KRAS wild-type tumors [hazard ratio (HR), 1.24; 95%

confidence interval (CI), 1.06–1.46; P=0.008]. However, these KRAS

mutations did not significantly affect progression-free survival

(HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.98–1.33; P=0.09) (20). The Raf protein has also been

extensively studied and shown to be involved in signal

transduction, cellular proliferation and carcinogenesis (Fig. 1); ~8% of CRC tumors exhibit

activating mutations in BRAF, which predominantly impacts codon 600

(21). The presence of BRAF

mutations in mCRC is widely recognized to have a notable negative

prognostic effect (22). These

mutations require an alternative therapeutic strategy since

conventional anti-EGFR treatments are frequently ineffective

(23). However, numerous targeted

methods are now being investigated for various types of cancer with

BRAF mutations, owing to the potential significance of BRAF

mutations as a driving signal in tumor growth (24). Previous studies have shown that KRAS

mutations, as well as BRAF mutations, have distinguished

pathological and clinical characteristics (25,26).

For example, CRC with KRAS exon 2 mutations are more common in

elderly individuals, particularly males, and are commonly seen in

the proximal colon when compared with the wild-type exon (27). Mutations in the BRAF gene are

strongly associated with females, the elderly, mucinous

differentiation, low histological grade and tumors located in the

proximal region of the colon (28).

Thus, the molecular variations emphasize the significance of

tailored treatment strategies in mCRC.

Although routine testing for RAS and BRAF mutations

is conducted on patients with mCRC in Jordan before recommending

anti-EGFR therapy, to the best of our knowledge, no previous

studies have reported on the possible association between

clinicopathological features and complete RAS and BRAF status,

which could help researchers identify other factors that influence

therapeutic response to anti-EGFR antibodies. Therefore, the aim of

the present study was to identify mutations in the RAS and BRAF

genes in patients with sporadic CRC and investigate their

associations with clinicopathological characteristics.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present study retrospectively analyzed patients'

electronic medical records from a single center, the Jordanian

Military Cancer Center-Royal Medical Services (Amman, Jordan). The

present study included 262 patients diagnosed with mCRC between

January 2020 and January 2022. Data regarding age, sex, RAS and

BRAF status, primary tumor site, histological subtypes and grade

were acquired. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows:

Age ≥18 years old and diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the colon or

rectum shown histologically. The exclusion criteria were as

follows: Patients with tumor types other than CRC, patients in

which RAS and BRAF mutations could not be determined (wild-type or

mutant), and cases where data was missing from the patients'

electronic medical records. The primary tumor sites were

categorized as follows: Tumors on the left side of the body, which

are more likely to develop in the distal one-third transverse

colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum,

and tumors on the right side of the body, which are more likely to

develop in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and proximal

two-thirds of the transverse colon (29). Transverse colon cancer is

characterized by tumors situated between the hepatic and splenic

flexures, and is extremely uncommon, comprising 10% of all colon

malignancies (30).

Histological subtypes were classified as classical

adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, tubuvillous adenoma,

invasive adenocarcinoma, medullary adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous

carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma. Additionally, the

histological grade was categorized as well-differentiated,

moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated.

Tumor molecular analysis

The KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutation status of patients

with CRC were extracted retrospectively from the electronic medical

records of patients at the Jordanian Military Cancer Center-Royal

Medical Services. However, all patients underwent tumor tissue

biopsies to ascertain RAS and BRAF mutation status using

quantitative polymerase chain reaction and reverse hybridization in

an accredited diagnostic laboratory at Jordan University Hospital

(Amman, Jordan) and only the final results were sent to the Royal

Medical Services.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

(version 23.0; IBM Corp.). Categorical variables are presented as

the frequency (n) and percentage. A χ2 test or Fisher's

exact test was used to determine the associations between

variables. The φ factor was used to examine the strength of

association (as a measure of effect size) as follows: 0, no

association; 0.1, small association; 0.3, medium association; 0.5,

strong association; and 1, complete association. Univariate

analysis was used to assess these associations, utilizing

statistical tests such as the χ2 or Fisher's exact test

when appropriate. In addition, a multivariate hierarchical

regression analysis was performed to examine the impact of

covariates on gene mutations. The regression analysis consisted of

three models, the first model included mutant or wild-type as

predictors, the second model included mutant or wild-type status,

age and sex as predictors, and the third model included

histological subtypes and tumor grade as predictors alongside

mutant or wild-type status, age and sex. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 262 patient records of mCRC were analyzed

(Table I). The cohort's mean age

was 55.91±12.81 years, with an age range of 19–85 years, and

patients >50 years old accounted for 64.9% of the cases (n=170).

Of the 262 patients, 153 (58.4%) were male and 109 (41.6%) were

female. Regarding the tumor site, 224 (85.5%) samples were

left-site tumors, which was more frequent compared with right-site

tumors (n=30; 11.5%) or transverse site tumors (n=6; 2.3%). More

than one-half of tumor cases (n=139; 53%) had a mutation in the RAS

gene and BRAF, whereas 46.9% (n=123) of the cases had wild-type RAS

gene and BRAF. In terms of histological subtypes, a large

proportion of cases were adenocarcinoma (not specified; n=246;

93.9%), followed by mucinous adenocarcinoma (n=11; 4.2%), then

tubular adenocarcinoma (n=3; 1.1%) and signet adenocarcinoma (n=2;

0.8%).

| Table I.Characteristics of patients with

metastatic CRC (n=262). |

Table I.

Characteristics of patients with

metastatic CRC (n=262).

|

Characteristics | Patients, n

(%) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

Female | 109 (41.6) |

|

Male | 153 (58.4) |

| Agea, years |

|

|

≤50 | 92 (35.1) |

|

>50 | 170 (64.9) |

| CRC site |

|

|

Right | 30 (11.5) |

|

Left | 224 (85.5) |

|

Transverse | 6 (2.3) |

|

Unknown | 2 (0.8) |

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 11 (4.2) |

| Tubular

adenocarcinoma | 3 (1.1) |

| Signet

adenocarcinoma | 2 (0.8) |

|

Adenocarcinoma (not

specified) | 246 (93.9) |

| Tumor grade |

|

| Poorly

differentiated | 23 (8.8) |

|

Moderately differentiated | 193 (73.7) |

|

Well-differentiated | 11 (4.2) |

| Not

determined | 35 (13.4) |

| Mutation

status |

|

|

Wild-type | 123 (46.9) |

|

Mutated | 139 (53.1) |

The characteristics of patients with mCRC are shown

in Table I. According to the WHO

criteria (31), tumor histology was

graded as poorly differentiated, moderately differentiated and

well-differentiated at 8.8 (n=23), 73.7 (n=193) and 4.2% (n=11),

respectively; the histological grade was not determined in 13.4%

(n=35) of patients.

Mutational status and detailed

mutation

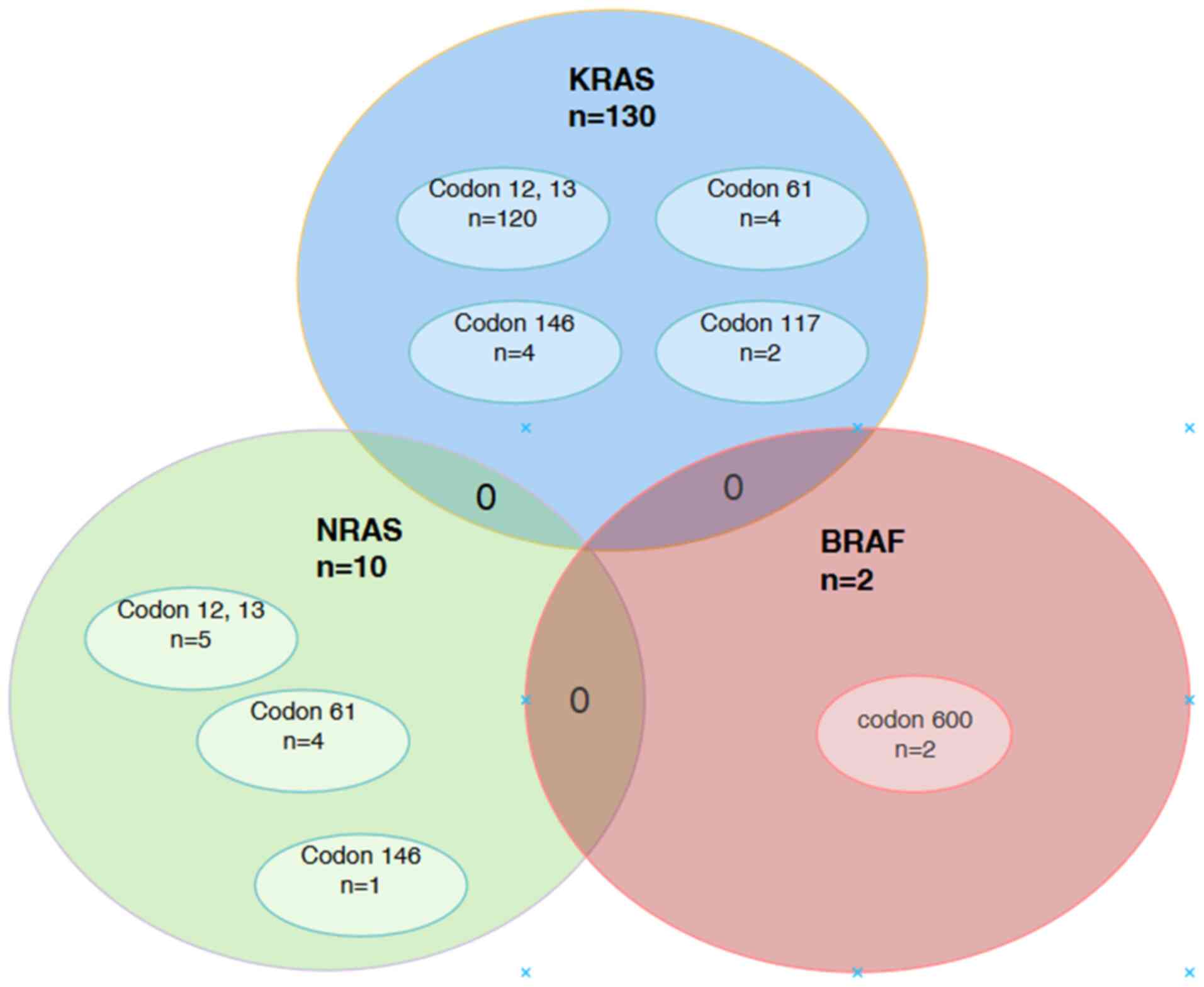

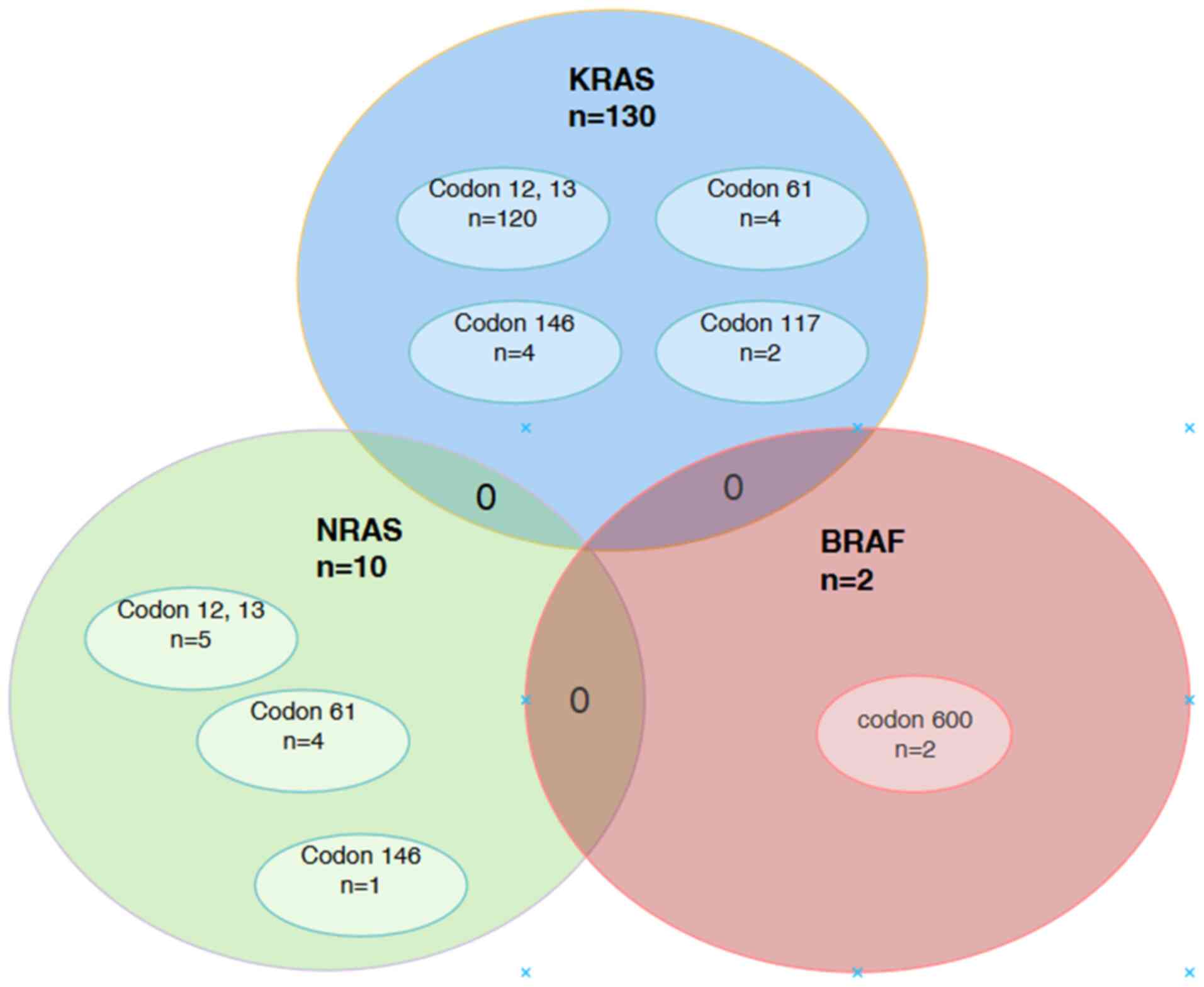

Out of 139 patients with mCRC carrying a mutation,

127 patients (48.5%) had KRAS mutations and 120 mutations (45.8%)

were detected in exon 2, with 10 mutations occurring outside of

exon 2 (exon 3 or exon 4). The most prevalent KRAS exon 2 mutations

were G12V (n=40; 15.3%), followed by G12D (n=32; 12.2%), while KRAS

K117× was the least common KRAS mutation (n=2; 0.8%). Notably, 4

patients with KRAS mutation exhibited 2 mutations each: 2 with G12C

and G12V mutations, 1 with G12V and G12A mutations, and 1 with G13D

and KRAS G12S mutations. Moreover, there is missing data regarding

detailed mutation for one patient thus, the total KRAS mutation

count was 130 (49.6%).

Regarding NRAS, 10 patients possessed a mutation of

this gene. Half of the cases demonstrated a substitution of glycine

to any amino acid mutation (G12×-G13×) accounting for 1.9% (n=5) of

mutated cases. Moreover, Q61K and Q61L mutations were present at

the same frequency and percentage (both n=2; 0.8%), and the A164×

mutation was the least common among all RAS mutations accounting

for 0.4% (n=1). For BRAF mutations, 2 cases of V600E were observed

(0.8%). Table II illustrates all

the mutations and the detailed classes. Moreover, none of the

patients carrying a mutation with the KRAS or NRAS genotype had a

simultaneous BRAF mutation (Fig.

2).

| Figure 2.Distribution of single and

concomitant mutations in the KRAS, NRAS and BRAF genes. In the

present study, 120 KRAS mutations were distributed across codons 12

and 13, codons 61 and 146, and codon 117. There were 10 NRAS

mutations distributed across codons 12 and 13, codon 61 and codon

146. There were 2 BRAF mutations in codon 600. Although overlapping

mutations between KRAS, NRAS and BRAF were not detected, 4 patients

did possess two KRAS mutations each, which made the total number of

KRAS mutations detected 130. KRAS, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral

oncogene homolog; NRAS, neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog;

BRAF, v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B. |

| Table II.Mutational status and detailed

mutation classes found in patients (n=262). |

Table II.

Mutational status and detailed

mutation classes found in patients (n=262).

| Mutational

status | Mutations, n

(%) | Exon | Codon |

|---|

| A, KRAS | 130a (49.6) |

|

|

| KRAS

G12A | 20 (7.6) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

G12D | 32 (12.2) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

G12V | 40 (15.3) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

G12S | 5 (1.9) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

G12C | 4 (1.5) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

G13A | 8 (3.1) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

G13D | 11 (4.2) | 2 | 12,13 |

| KRAS

Q61× | 4 (1.5) | 3 | 61 |

| KRAS

K117× | 2 (0.8) | 4 | 117 |

| KRAS

A146× | 4 (1.5) | 4 | 146 |

| B, NRAS | 10 (3.8) |

|

|

| NRAS

G12×-G13× | 5 (1.9) | 2 | 12,13 |

| NRAS

Q61K | 2 (0.8) | 3 | 61 |

| NRAS

Q61L | 2 (0.8) | 3 | 61 |

| NRAS

A146× | 1 (0.4) | 4 | 146 |

| C, BRAF | 2 (0.76) |

|

|

| BRAF

V600E | 2 (0.76) | 15 | 600 |

| Total

number of KRAS/NRAS/BRAF mutations | 142 (54.2) | - | - |

Association between RAS mutations,

wild-type status and the patients' clinicopathological

features

The associations between the mutational status of

the RAS gene and various clinicopathological characteristics were

assessed using univariate analyses, such as the χ2 or

Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. RAS mutations were more

prevalent in males (n=78; 56.9%), in patients >50 years old

(n=94; 68.6%) and in tumors located in the left side of the colon

(n=115; 83.9%). Additionally, RAS mutations were more frequently

observed, albeit not significantly, with the adenocarcinoma (not

specified) histological subtype (n=129; 94.2%) and moderately

differentiated tumor grade (n=102; 74.5%). No other

clinicopathological features had notable associations with RAS

mutations (Table III).

| Table III.Univariate analysis of the

association between RAS mutation, wild-type status and

clinicopathological features. |

Table III.

Univariate analysis of the

association between RAS mutation, wild-type status and

clinicopathological features.

|

| RAS status |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | Mutated, n (%) | Wild-type, n

(%) | P-value | Association

strength (φ) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 59 (43.1) | 50 (40) | 0.615 | −0.031 |

|

Male | 78 (56.9) | 75 (60) |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

≤50 | 43 (31.4) | 49 (39.2) | 0.186 | 0.082 |

|

>50 | 94 (68.6) | 76 (60.8) |

|

|

| CRC site |

|

|

|

|

|

Right | 17 (12.4) | 13 (10.4) | 0.687a | 0.091 |

|

Left | 115 (83.9) | 109 (87.2) |

|

|

|

Transverse | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.4) |

|

|

|

Unknown | 2 (1.5) | - |

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 5 (3.6) | 6 (4.8) | 0.953a | 0.042 |

| Tubular

adenocarcinoma | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) |

|

|

| Signet

adenocarcinoma | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) |

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma (not

specified) | 129 (94.2) | 117 (93.6) |

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

|

| Poorly

differentiated | 17 (12.4) | 6 (4.8) | 0.056 | 0.170 |

|

Moderately differentiated | 102 (74.5) | 91 (72.8) |

|

|

|

Well-differentiated | 4 (2.9) | 7 (5.6) |

|

|

| Not

determined | 14 (10.2) | 21 (16.8) |

|

|

Association between KRAS, NRAS, BRAF

mutations and wild-type status with the patients'

clinicopathological features

Univariate analysis was performed to investigate the

association between different subtypes of RAS mutations (KRAS and

NRAS) and BRAF mutations with various clinicopathological

characteristics (Table IV). Both

KRAS (n=86; 67.7%) and NRAS n=8; 80%) mutations were more frequent

in patients >50 years old and in tumors located in the left side

of the colon (KRAS n=106; 83.5%), (NRAS n=9; 90%) frequently, as

well as both mutations (KRAS n=120; 94.5%, and NRAS n=9; 90%) were

more prevalent in patients with adenocarcinoma (not specified);

however, these findings were not statistically significant. By

contrast, NRAS mutations were significantly associated with

moderately differentiated tumors (n=6; 60%, P<0.05). Similar to

KRAS mutations, BRAF mutations were more common in patients >50

years old (n=2; 100%) and in tumors located in the left side of the

colon (n=2; 0.9%), although the association was not significant

(Table IV).

| Table IV.Univariate analysis of the

association between KRAS, NRAS, BRAF mutations, wild-type status

and clinicopathological features. |

Table IV.

Univariate analysis of the

association between KRAS, NRAS, BRAF mutations, wild-type status

and clinicopathological features.

| A, KRAS status |

|---|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | Mutated, n (%) | Wild-type, n

(%) | P-value | Association

strength (φ) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 54 (42.5) | 55 (40.7) | 0.868a | −0.018 |

|

Male | 73 (57.5) | 80 (59.3) |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

≤50 | 41 (32.3) | 51 (37.8) | 0.352 | 0.058 |

|

>50 | 86 (67.7) | 84 (62.2) |

|

|

| CRC site |

|

|

|

|

|

Right | 17 (13.4) | 13 (9.6) | 0.354b | 0.117 |

|

Left | 106 (83.5) | 118 (87.4) |

|

|

|

Transverse | 2 (1.6) | 4 (3.0) |

|

|

|

Unknown | 2 (1.6) | - |

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 5 (3.9) | 6 (4.4) | 0.682b | 0.094 |

| Tubular

adenocarcinoma | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) |

|

|

| Signet

adenocarcinoma | - | 2 (1.5) |

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma (not

specified) | 120 (94.5) | 126 (93.3) |

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

|

| Poorly

differentiated | 13 (10.2) | 10 (7.4) | 0.499 | 0.095 |

|

Moderately differentiated | 96 (75.6) | 97 (71.9) |

|

|

|

Well-differentiated | 4 (3.1) | 7 (5.2) |

|

|

| Not

determined | 14 (11.0) | 21 (15.6) |

|

|

|

| B, NRAS

status |

|

|

Characteristics | Mutated, n

(%) | Wild-type, n

(%) | P-value | Association

strength (φ) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 5 (50) | 104 (41.3) | 0.746b | −0.034 |

|

Male | 5 (50.0) | 148 (58.7) |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

≤50 | 2 (20.0) | 90 (35.7) | 0.307 | 0.063 |

|

>50 | 8 (80.0) | 162 (64.3) |

|

|

| CRC site |

|

|

|

|

|

Right | - | 30 (11.9) | 0.215b | 0.123 |

|

Left | 9 (90.0) | 215 (85.3) |

|

|

|

Transverse | 1 (10.0) | 5 (2.0) |

|

|

|

Unknown | - | 2 (0.8) |

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | - | 11 (4.4) | 0.116b | 0.216 |

| Tubular

adenocarcinoma | - | 3 (1.2) |

|

|

| Signet

adenocarcinoma | 1 (10.0) | 1 (0.4) |

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma (not

specified) | 9 (90.0) | 237 (94.0) |

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

|

| Poorly

differentiated | 4 (40.0) | 19 (7.5) | 0.02b,c | 0.228 |

|

Moderately differentiated | 6 (60.0) | 187 (74.2) |

|

|

|

Well-differentiated | - | 11 (4.4) |

|

|

| Not

determined | - | 35 (13.9) |

|

|

|

| C, BRAF

status |

|

|

Characteristics | Mutated, n

(%) | Wild-type, n

(%) | P-value | Association

strength (φ) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 1 (50.0) | 108 (41.5) |

>0.999b | −0.015 |

|

Male | 1 (50.0) | 152 (58.5) |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

≤50 | - | 92 (35.4) | 0.543b | 0.065 |

|

>50 | 2 (100.0) | 168 (64.6) |

|

|

| CRC site |

|

|

|

|

|

Right | - | 30 (11.5) |

>0.999b | 0.036 |

|

Left | 2 (0.9) | 222 (85.4) |

|

|

|

Transverse | - | 6 (2.3) |

|

|

|

Unknown | - | 2 (0.8) |

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1 (50) | 10 (3.8) | 0.119b | 0.20 |

| Tubular

adenocarcinoma | - | 3 (1.2) |

|

|

| Signet

adenocarcinoma | - | 2 (0.8) |

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma (not

specified) | 1 (50) | 245 (94.2) |

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

|

| Poorly

differentiated | - | 23 (8.8) | 0.458b | 0.097 |

|

Moderately differentiated | 1 (50) | 192 (73.8) |

|

|

|

Well-differentiated | - | 11 (4.2) |

|

|

| Not

determined | 1 (50) | 34 (13.1) |

|

|

A multivariate hierarchical regression analysis was

performed to examine the impact of covariates on gene mutations.

For the KRAS gene, in the first model the predictor was the mutant

or wild-type. The result showed that the mutant or wild-type is a

significant predictor (B=0.914; β=0.912; P<0.001). The model

accounted for 83.2% of the variance in KRAS (R2=0.832;

adjusted R2=0.832), with a model significance

(F=1,291.813; P<0.001) (Table

V).

| Table V.A multivariate hierarchical

regression analysis of the KRAS gene. |

Table V.

A multivariate hierarchical

regression analysis of the KRAS gene.

| A, Model 1 |

|---|

|

|---|

| Variable | B | SE.B | β |

|---|

| Mutant or

wild-type | 0.914 | 0.025 | 0.912a |

| Age |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

| R2 | 0.832 |

|

|

| Adjusted

R2 |

| 0.832 |

|

| F change in

R2 |

|

|

1,291.813a |

|

| B, Model

2 |

|

|

Variable | B | SE.B | β |

|

| Mutant or

wild-type | 0.917 | 0.026 | 0.916a |

| Age | −0.031 | 0.027 | −0.030 |

| Sex | −0.017 | 0.026 | −0.017 |

| Histological

subtypes |

|

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

| R2 | 0.832 |

|

|

| Adjusted

R2 |

| 0.832 |

|

| F change in

R2 |

|

| 0.795 |

|

| C, Model

3 |

|

|

Variable | B | SE.B | β |

|

| Mutant or

wild-type | 0.915 | 0.025 | 0.914a |

| Age | −0.037 | −0.037 | −0.037 |

| Sex | −0.013 | 0.026 | −0.013 |

| Histological

subtypes | −0.074 | 0.033 | −0.057a |

| Tumor grade | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.022 |

| R2 | 0.836 |

|

|

| Adjusted

R2 |

| 0.836 |

|

| F change in

R2 |

|

| 3.251b |

The second model included mutant or wild-type

status, age and sex as predictors. Mutant or wild-type status

remained a significant predictor (B=0.917; β=0.916; P<0.001),

with only a slight increase in its effect size compared to model 1.

Age (B=−0.031; β=−0.030; P>0.05) and sex (B=−0.017; β=−0.017;

P>0.05) were not significant predictors. Model 2 accounted for

83.2% of the variance in KRAS, as seen in model 1

(R2=0.832; adjusted R2=0.832), but there was

no significant increase in R2 compared to model 1

(F-change=0.795; P>0.05).

The third model included histological subtypes and

tumor grade as predictors alongside mutant or wild-type status, age

and sex. Mutant or wild-type status remained a significant

predictor (B=0.915; β=0.914; P<0.001). Age (B=−0.037; β=−0.037;

P>0.05) and sex (B=−0.013; β=−0.013; P>0.05) were not

statistically significant predictors. Histological subtype was a

significant predictor (B=−0.074; β=−0.057; P<0.001); however,

the tumor grade was not significant (B=0.014; β=0.022; P>0.05).

The model accounted for 83.6% of the variance in KRAS

(R2=0.836; adjusted R2=0.836), with a small

but significant increase in explanatory power compared with model 2

(F-change=3.251; P<0.05). One-way ANOVA as the out-put from

multivariate hierarchical regression confirmed the statistical

significance of all three models: Model 1, F(1,

261)=1,291.813, P<0.001; model 2, F(3,

259)=430.455, P<0.001; and model 3, F(6,

256)=222.487, P<0.001 (numbers in brackets represent

degree of freedom and sample number) (Table VI).

| Table VI.ANOVA results for predictive models

of KRAS mutation variance based on genetic, demographic and

histological factors. |

Table VI.

ANOVA results for predictive models

of KRAS mutation variance based on genetic, demographic and

histological factors.

| Model | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | P-value |

|---|

| 1 | 54.475 | 1 | 54.475 | 1,291.813 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 54.542 | 3 | 18.181 | 430.455 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 54.943 | 6 | 9.157 | 222.487 | <0.001 |

For the NRAS gene, in the first model, the mutant or

wild-type status was a significant predictor (B=0.72; β=0.187;

P<0.05). The model accounted for 3.5% of the variance in NRAS

(R2=0.035; adjusted R2=0.031; F=9.462;

P<0.05), which indicated a significant contribution of mutant or

wild-type (Table VII).

| Table VII.A multivariate hierarchical

regression analysis of the NRAS gene. |

Table VII.

A multivariate hierarchical

regression analysis of the NRAS gene.

| A, Model 1 |

|---|

|

|---|

| Variable | B | SE.B | β |

|---|

| Mutant or

wild-type | 0.72 | 0.023 | 0.187a |

| Age |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

| Histological

subtypes |

|

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

| R2 | 0.035 |

|

|

| Adjusted

R2 |

| 0.031 |

|

| F change in

R2 |

|

| 9.462a |

|

| B, Model

2 |

|

|

Variable | B | SE.B | β |

|

| Mutant or

wild-type | 0.07 | 0.024 | 0.182a |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.025 | 0.05 |

| Sex | 0.013 | 0.024 | 0.034 |

| Histological

subtypes |

|

|

|

| Tumor grade |

|

|

|

| R2 | 0.038 |

|

|

| Adjusted

R2 |

| 0.027 |

|

| F change in

R2 |

|

| 0.435 |

|

| C, Model

3 |

|

|

Variable | B | SE.B | β |

|

| Mutant or

wild-type | 0.072 | 0.023 | 0.186a |

| Age | 0.023 | 0.025 | 0.057 |

| Sex | 0.010 | 0.024 | 0.026 |

| Histological

subtypes | 0.054 | 0.030 | 0.112 |

| Tumor grade | 0.053 | 0.030 | 0.107 |

| R2 | 0.063 |

|

|

| Adjusted

R2 |

| 0.031 |

|

| F change in

R2 |

|

| 2.253a |

The second model incorporated age and sex as

predictors alongside the mutant or wild-type variable. Mutant or

wild-type status was a significant predictor of NRAS (B=0.07;

β=0.182; P<0.05), with only a slight decrease in its effect size

compared with model 1. Age (B=0.02; β=0.05; P>0.05) and sex

(B=0.013; β=0.034; P>0.05) were not significant predictors of

NRAS. Model 2 accounted for 3.8% of the variance in NRAS

(R2=0.038; adjusted R2=0.027), with a

non-significant overall F-statistic (F=0.435; P>0.05).

The third model included histological subtypes and

tumor grade as additional predictors. Mutant or wild-type status

remained a significant predictor of NRAS (B=0.072; β=0.186;

P<0.05). Age (B=0.023; β=0.057; P>0.05) and sex (B=0.010;

β=0.026; P>0.05) were not significant predictors. Similarly,

histological subtypes (B=0.054; β=0.112; P>0.05) and tumor grade

(B=0.053; β=0.107; P>0.05) were not significantly associated

with NRAS. Model 3 accounted for 6.3% of the variance in NRAS

(R2=0.063; adjusted R2=0.031), with a

significant F-statistic (F=2.253; P<0.05). However, the increase

in variance accounted for model 3 compared with the model 2 was a

modest increase (∆R2=0.025).

ANOVA confirmed that the three models were

statistically significant: Model 1, F(1, 261)=9.462;

P<0.05; model 2, F(3, 259)=3.431, P<0.05; model 3,

F(6, 256)=2.867; P<0.05. These results demonstrate

that each model represented a statistically significant improvement

over the null model (Table

VIII).

| Table VIII.ANOVA results for predictive models

of NRAS mutation variance using genetic, demographic and

histological predictors. |

Table VIII.

ANOVA results for predictive models

of NRAS mutation variance using genetic, demographic and

histological predictors.

| Model | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom

(df) | Mean square | F | P-value |

|---|

| 1 | 0.338 | 1 | 0.338 | 9.462 | <0.05 |

| 2 | 0.369 | 3 | 0.123 | 3.431 | <0.05 |

| 3 | 0.608 | 6 | 0.101 | 2.867 | <0.05 |

Discussion

CRC is a highly prevalent malignancy with highly

variable occurrence and fatality rates globally (2). In 2023, an estimated 153,020

individuals received a diagnosis of CRC, with 52,550 fatalities

attributed to the disease, encompassing 19,550 cases and 3,750

deaths among those <50 years of age (32).

The impact of the RAS mutation pattern on anticancer

therapy orientation has been extensively documented (33). Patients with CRC tumors mutations in

exon 2 of the KRAS gene (specifically in codons 12 and 13) do not

experience a clinical response from anti-EGFR-based therapies

(34). Notably, some patients with

CRC with wild-type KRAS exon 2 do not exhibit a favorable response

to anti-EGFR therapy, indicating that the presence of other RAS

mutations (namely, KRAS exons 3 and 4 or NRAS exons 2, 3 and 4) and

BRAF or PIK3CA mutations can serve as a negative indicator for the

effectiveness of anti-EGFR treatment (23). A case study on brain metastasis in a

patient with KRAS wild-type CRC treated with cetuximab alongside

chemotherapy (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) demonstrated a

substantial reduction in brain metastases with the cetuximab and

chemotherapy regimen before any radiation intervention (35). However, to the best of our

knowledge, no real-world data has been published for patients with

CRC receiving anti-EGFR treatment and cetuximab.

In the present retrospective study, the RAS and BRAF

gene mutation rates in patients with mCRC were investigated. In

addition, the associations between these genetic alterations and

clinicopathological characteristics were examined. Results from the

present study were consistent with previous studies where >50%

of cases had CRC mutations (36).

The prevalence of KRAS mutations in patients with mutations was

48.5%, close to a results of a previous study conducted in Jordan

(44%) (37). For comparison,

Western Europe has a KRAS mutation rate of 44.7% (38), Indonesia has a rate of 41% (39) and China has a rate of 36.1%

(40).

In contrast to KRAS, NRAS changes are infrequent and

there is currently limited evidence on the incidence of these

mutations (41). In the present

study, the NRAS mutation rate was 3.82%. Zhang et al

(42) reported a rate of 3.69% in a

Chinese study, and studies on Italian and Indian patients indicated

frequencies of 6 and 6.3%, respectively (43). By contrast, Greek and Romanian

patients had a higher incidence rate of 9.57% (44). According to the present study, BRAF

mutations were detected in 0.76% of Jordanian patients, which is

lower compared with the percentage for Western countries (9.2%) and

Asian countries (4.9%) (45). The

KRAS, NRAS and BRAF frequency variations between studies are likely

due to several factors, including ethnicity, geographical

dispersion and utilization of distinct methods/assays to evaluate

the presence of these mutations.

The present study examined KRAS mutations in

patients with mCRC, namely those located in exon 2 and those

outside of exon 2. The prevalence of KRAS mutations was ~45.8%,

consistent with findings from a prior study in Jordan (37). Another previous study reported

mutational frequencies in this exon ranging from 15–46% based on

country (46). According to the

present study, among the KRAS mutations, G12V has the highest

prevalence, followed by G12D, G12A, G13D, G13A, G12S and G12C. The

findings indicate minor variations compared with research conducted

on Western populations, implying that ethnicity may influence the

patterns of KRAS mutations (47).

In the present study, among the NRAS mutations (3.9%), 1.9% of the

samples had a mutation in exon 2 (codon 12 or 13), which is

comparable to the Chinese population (32). The prevalence of BRAF mutations

ranges from 1.1 to 25% globally (41). Notably, the frequency of the V600E

mutation in the present study (0.76%) was detected in exon 15,

which is lower than the frequency seen in previous Asian studies

(48,49). The clinical significance of the KRAS

mutations, except those of codons 12 and 13, remains unclear.

Loupakis et al (50)

reported that a patient with mCRC and KRAS A146 mutation was

resistant to cetuximab. In another study, it was found that NRAS

mutation carriers showed a significantly lower response rate

compared with patients with wild-type KRAS when treated with

cetuximab (23). Nevertheless,

there is an ongoing debate over the association between BRAF

mutations and the effectiveness of anti-EGFR treatment (51). For example, a previous study

reported that RAS status was fully determined and a thorough

analysis of the association between clinicopathological and

molecular features indicated no statistically significant

association (52). Secondly, the

association between RAS subtypes and BRAF with patients'

clinicopathologicalfeatures was analyzed and the findings were

contradictory. Previous findings have indicated that KRAS mutations

are associated with different clinicopathological criteria,

although this association is not universally observed in all

studies (36,41,53).

In the present study, a multivariate analysis

demonstrated a significant association between KRAS mutations and

histological subtypes (41).

Additionally, there are numerous discrepancies and variations

regarding KRAS mutations and tumor locations or histological

subtypes (45). For example,

correlations were found between KRAS mutation and tumors in the

right colon (54) or rectal tumors

(28), whereas other studies

reported an association between KRAS mutations and a patient's age

(55), tumor site and

differentiation (55). The

association between NRAS mutations and clinicopathological features

was investigated in the present study. The results showed an

association with tumor grades. NRAS mutations were more frequent in

moderately differentiated tumors compared with poorly

differentiated tumors. However, a previous study established a

significant association between NRAS mutations and a patient's age

(56). Another study found an

association between NRAS mutations and the initial phases of cancer

and the lack of lymph node metastases (55). While other study found that NRAS

mutations are more commonly found in left-sided malignancies and

women (57), whereas Chang et

al (58) identified a link

between NRAS mutations and men. In addition, Shen et al

(59) reported that these mutations

occurred more frequently in distant metastatic tumors and their

occurrence varied depending on the different phases of the tumor.

Another study did not identify any associations (60). Notably, previous research conducted

on Western populations reported an association between BRAF-mutant

CRC and the female sex (61).

However, the present study did not find a statistically significant

association between BRAF mutations and sex. In contrast to the

study by Zhang et al (41),

which demonstrated a significant correlation between BRAF mutations

and right-sided colon cancer, the present study did not demonstrate

any significant association between BRAF mutations and tumor site

or any other clinicopathological features. However, it is important

to note that the findings of the present study are constrained by

the limited number of patients with a BRAF mutation, which amounted

to only 2 patients.

The present study has certain limitations, including

the limited sample size and single-centered nature of the present

study, which made it difficult to draw broader conclusions. The

association between KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations and the

clinicopathological features of patients with CRC may be further

understood in future investigations with larger patient groups.

The retrospective nature of the present study was

designed to demonstrate the association between RAS mutations and

clinicopathological variables regardless of the possible survival

benefits, and may help improve the life expectancy of patients

receiving anti-EGFR treatment with a wild-type RAS genotype. It can

be considered that the samples being studied inherently exhibit

variability in response to treatment. The therapeutic regimens

differed across the patients, which led to heterogeneity and may

have impacted the median overall survival, particularly in patients

with wild-type KRAS. This is because not all patients received

cetuximab and panitumumab as their initial treatment due to limited

availability and were thus treated with other chemotherapeutic

regimens. However, future work will focus on treatment efficacy and

overall patient survival, with predictive significance in selecting

patients for anti-EGFR therapy.

In conclusion, the present study examined the

association between clinicopathological characteristics and the

mutational landscape of mCRC in a cohort of patients. The results

emphasize the diversity of CRC and the need for individualized

treatment approaches, and highlight novel research opportunities,

particularly in comprehending the distinctive characteristics of

CRC in particular communities. Studies such as these serve a key

role in influencing clinical practice, determining future research

paths, and developing improved and personalized treatments for CRC

based on individual patient characteristics as a key objective in

the field of oncology. Furthermore, multicenter studies are

currently in the design phase to validate the generalizability in a

wide range of patients. These studies will additionally determine

the validity on patients of differing demographics, improving

reliability and accuracy in clinical settings worldwide. The

research may then be linked with clinical decision-making to help

drive personalized medicine and evidence-based therapeutics. Future

research is warranted to define the predictive significance of the

RAS and BRAF mutation status, and to discover any variations that

may benefit from different treatments based on patients' prognostic

values.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RawA and RazA conceptualized the present study,

contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, and revised it

critically for important intellectual content. RoaA conducted the

formal analysis, contributed substantially to the acquisition and

interpretation of data, wrote parts of the manuscript, and

participated in revising the manuscript critically for important

intellectual content. AAl was involved in the design of the study,

validated the experimental procedures, contributed to the drafting

of the manuscript, and revised it critically for important

intellectual content. EQ used the SPSS software, entered the data

for analysis, and assisted in interpreting the data outcomes as

part of the manuscript's drafting and critical revision process.

RawA validated the study, curated the data, wrote the original

draft, and revised the manuscript critically. MO and AAb were

involved in the conceptualization and design of the study,

critically evaluated and interpreted the experimental data,

contributed to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript

for important intellectual content, ensured the integrity and

accuracy of the work, and wrote, reviewed and edited the

manuscript, ensuring the interpretation and application of data

were appropriately conducted. AAb and RazA confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present investigation is characterized as an

observational retrospective study. All patients were treated

according to standard clinical protocols. The present study

received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The

Hashemite University (Zarqa, Jordan; approval no. 13/9/2021/2022)

and Jordanian Royal Medical Services (Amman, Jordan). The

requirement for informed consent was waived by the Jordanian Royal

Medical Services (Amman, Jordan; IRB approval no. 2/2024, dated

12/2/2024).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

mCRC

|

metastatic CRC

|

|

EGFR

|

epidermal growth factor receptor

|

|

KRAS

|

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene

homolog

|

|

NRAS

|

neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene

homolog

|

|

BRAF

|

v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene

homolog B

|

References

|

1

|

Bonnot PE and Passot G: RAS mutation: Site

of disease and recurrence pattern in colorectal cancer. Chin Clin

Oncol. 8:55. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xi Y and Xu P: Global colorectal cancer

burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol.

14:1011742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jordan Cancer Registry, . Cancer Incidence

in Jordan. Minist Heal Jordan. 11:15–17. 2018.

|

|

5

|

Sharkas GF, Arqoub KH, Khader YS, Tarawneh

MR, Nimri OF, Al-Zaghal MJ and Subih HS: Colorectal cancer in

Jordan: Survival rate and its related factors. J Oncol.

2017:31807622017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Saoudi González N, Salvà F, Ros J,

Baraibar I, Rodríguez-Castells M, García A, Alcaráz A, Vega S,

Bueno S, Tabernero J and Elez E: Unravelling the complexity of

colorectal cancer: Heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and clinical

implications. Cancers (Basel). 15:40202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dienstmann R, Connor K and Byrne AT:

Precision therapy in RAS mutant colorectal cancer.

Gastroenterology. 158:806–811. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gong J, Cho M and Fakih M: RAS and BRAF in

metastatic colorectal cancer management. J Gastrointest Oncol.

7:6872016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tsuchida N, Murugan AK and Grieco M:

Kirsten ras oncogene: Significance of its discovery in human cancer

research. Oncotarget. 7:467172016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lakatos G, Köhne CH and Bodoky G: Current

therapy of advanced colorectal cancer according to RAS/RAF

mutational status. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 39:1143–1157. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Takane K, Akagi K, Fukuyo M, Yagi K,

Takayama T and Kaneda A: DNA methylation epigenotype and clinical

features of NRAS-mutation(+) colorectal cancer. Cancer Med.

6:1023–1035. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cercek A, Braghiroli MI, Chou JF, Hechtman

JF, Kemeny N, Saltz L, Capanu M and Yaeger R: Clinical features and

outcomes of patients with colorectal cancers harboring NRAS

mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 23:4753–4760. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang Y, Loree JM, Yu C, Tschautscher M,

Overman MJ, Broaddus R and Grothey A: Distinct impacts of KRAS,

NRAS and BRAF mutations on survival of patients with metastatic

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 36:3513. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Vigil D, Cherfils J, Rossman KL and Der

CJ: Ras superfamily GEFs and GAPs: Validated and tractable targets

for cancer therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 10:842–857. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Khan AQ, Kuttikrishnan S, Siveen KS,

Prabhu KS, Shanmugakonar M, Al-Naemi HA, Haris M, Dermime S and

Uddin S: RAS-mediated oncogenic signaling pathways in human

malignancies. Semin Cancer Biol. 54:1–13. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Colussi D, Brandi G, Bazzoli F and

Ricciardiello L: Molecular pathways involved in colorectal cancer:

Implications for disease behavior and prevention. Int J Mol Sci.

14:16365–16385. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Newhall K, Price T, Peeters M, Kim TW, Li

J, Cascinu S, Ruff P, Suresh AS, Thomas A, Tjulandin S, et al:

Frequency of S492R mutations in the epidermal growth factor

receptor: Analysis of plasma dna from metastatic colorectal cancer

patients treated with panitumumab or cetuximab monotherapy. Ann

Oncol. 25:II1092014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ,

O'Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, Simes RJ, Chalchal H, Shapiro JD,

Robitaille S, et al: K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in

advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 359:1757–1765. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Meng M, Zhong K, Jiang T, Liu Z, Kwan HY

and Su T: The current understanding on the impact of KRAS on

colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 140:1117172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P,

Elliott F, Daly CL, Meade AM, Taylor G, Barrett JH and Quirke P:

KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are

associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from

oxaliplatin or irinotecan: Results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin

Oncol. 27:5931–5937. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P,

Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W,

et al: Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nat.

417:949–954. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li ZN, Zhao L, Yu LF and Wei MJ: BRAF and

KRAS mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer: Future perspectives

for personalized therapy. Gastroenterol Rep. 8:192–205. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, De

Schutter J, Biesmans B, Fountzilas G, Kalogeras KT, Kotoula V,

Papamichael D, Laurent-Puig P, et al: Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS,

and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy

in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A

retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 11:753–762. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kopetz S, Desai J, Chan E, Hecht JR,

O'Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, Nolop KB and Saltz L: PLX4032 in metastatic

colorectal cancer patients with mutant BRAF tumors. J Clin Oncol.

28 (Suppl 15):S3534. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Avădănei ER, Căruntu ID, Nucă I, Balan RA,

Lozneanu L, Giusca SE, Pricope DL, Dascalu CG and Amalinei C: KRAS

mutation status in relation to clinicopathological characteristics

of romanian colorectal cancer patients. Curr Issues Mol Biol.

47:1202025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li WQ, Kawakami K, Ruszkiewicz A, Bennett

G, Moore J and Iacopetta B: BRAF mutations are associated with

distinctive clinical, pathological and molecular features of

colorectal cancer independently of microsatellite instability

status. Mol Cancer. 5:22006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Koochak A, Rakhshani N, Karbalaie Niya MH,

Tameshkel FS, Sohrabi MR, Babaee MR, Rezvani H, Bahar B, Imanzade

F, Zamani F, et al: Mutation analysis of KRAS and BRAF genes in

metastatic colorectal cancer: A First large scale study from iran.

Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 17:603–608. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kawazoe A, Shitara K, Fukuoka S, Kuboki Y,

Bando H, Okamoto W, Kojima T, Fuse N, Yamanaka T, Doi T, et al: A

retrospective observational study of clinicopathological features

of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in Japanese patients with

metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 15:2582015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Stintzing S, Tejpar S, Gibbs P, Thiebach L

and Lenz HJ: Understanding the role of primary tumour localisation

in colorectal cancer treatment and outcomes. Eur J Cancer.

84:69–80. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li C, Wang Q and Jiang KW: What is the

best surgical procedure of transverse colon cancer? An evidence map

and minireview. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 13:3912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA;

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, : The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA

and Jemal A: Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin.

73:233–254. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pirvu EE, Severin E, Niţă I and Toma

Ștefania A: The impact of RAS mutation on the treatment strategy of

colorectal cancer. Med Pharm Rep. 96:5–15. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dempke WC and Heinemann V: Ras mutational

status is a biomarker for resistance to EGFR inhibitors in

colorectal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 30:4673–4677. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ibrahimi AKH, Al-Hussaini M, Laban DA,

Ammarin R, Wehbeh L and Al-Mousa A: Cetuximab plus XELOX show

efficacy against brain metastasis from colorectal cancer: A case

report. CNS Oncol. 12:CNS972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Rimbert J, Tachon G, Junca A, Villalva C,

Karayan-Tapon L and Tougeron D: Association between

clinicopathological characteristics and RAS mutation in colorectal

cancer. Mod Pathol. 31:517–526. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sughayer WM and Sughayer MA: KRAS

mutations and subtyping in colorectal cancer in Jordanian patients.

Oncol Lett. 4:705–710. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Afrǎsânie VA, Marinca MV, Alexa-Stratulat

T, Gafton B, Păduraru M, Adavidoaiei AM, Miron L and Rusu C: KRAS,

NRAS, BRAF, HER2 and microsatellite instability in metastatic

colorectal cancer-practical implications for the clinician. Radiol

Oncol. 53:265–274. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Levi M, Prayogi G, Sastranagara F,

Sudianto E, Widjajahakim G, Gani W, Mahanadi A, Agnes J, Khairunisa

BH and Utomo AR: Clinicopathological associations of K-RAS and

N-RAS mutations in indonesian colorectal cancer cohort. J

Gastrointest Cancer. 49:124–131. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ye ZL, Qiu MZ, Tang T, Wang F, Zhou YX,

Lei MJ, Guan WL and He CY: Gene mutation profiling in Chinese

colorectal cancer patients and its association with

clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis. Cancer Med.

9:745–756. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang J, Zheng J, Yang Y, Lu J, Gao J, Lu

T, Sun J, Jiang H, Zhu Y, Zheng Y, et al: Molecular spectrum of

KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in Chinese colorectal cancer

patients: Analysis of 1,110 cases. Sci Rep. 5:186782015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang X, Ran W, Wu J, Li H, Liu H, Wang L,

Xiao Y, Wang X, Li Y and Xing X: Deficient mismatch repair and RAS

mutation in colorectal carcinoma patients: A retrospective study in

Eastern China. PeerJ. 6:e43412018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Jauhri M, Bhatnagar A, Gupta S, Manasa BP,

Minhas S, Shokeen Y and Aggarwal S: Prevalence and coexistence of

KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS, TP53, and APC mutations in Indian

colorectal cancer patients: Next-generation sequencing-based cohort

study. Tumor Biol. 39:10104283176922652017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Negru S, Papadopoulou E, Apessos A,

Stanculeanu DL, Ciuleanu E, Volovat C, Croitoru A, Kakolyris S,

Aravantinos G, Ziras N, et al: KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations in

Greek and Romanian patients with colorectal cancer: A cohort study.

BMJ Open. 4:e0046522014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Al-Shamsi HO, Jones J, Fahmawi Y, Dahbour

I, Tabash A, Abdel-Wahab R, Abousamra AO, Shaw KR, Xiao L, Hassan

MM, et al: Molecular spectrum of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, TP53,

and APC somatic gene mutations in Arab patients with colorectal

cancer: Determination of frequency and distribution pattern. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 7:882–902. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ouerhani S, Bougatef K, Soltani I,

Elgaaied ABA, Abbes S and Menif S: The prevalence and prognostic

significance of KRAS mutation in bladder cancer, chronic myeloid

leukemia and colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 40:4109–4114. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Neumann J, Zeindl-Eberhart E, Kirchner T

and Jung A: Frequency and type of KRAS mutations in routine

diagnostic analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer. Pathol Res

Pract. 205:858–862. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Baldus SE, Schaefer KL, Engers R, Hartleb

D, Stoecklein NH and Gabbert HE: Prevalence and heterogeneity of

KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations in primary colorectal

adenocarcinomas and their corresponding metastases. Clin Cancer

Res. 16:790–799. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK,

Henrichsen-Schnack T, Ladelund S and Nilbert M: The predictive

value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment

in metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Acta Oncol (Madr). 53:852–864. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Cremolini C, Vincenzi

B, Salvatore L, Santini D, Masi G, Stasi I, Canestrari E, Rulli E,

et al: KRAS codon 61, 146 and BRAF mutations predict resistance to

cetuximab plus irinotecan in KRAS codon 12 and 13 wild-type

metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 101:715–721. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Karapetis CS, Jonker D, Daneshmand M,

Hanson JE, O'Callaghan CJ, Marginean C, Zalcberg JR, Simes J, Moore

MJ, Tebbutt NC, et al: PIK3CA, BRAF, and PTEN status and benefit

from cetuximab in the treatment of advanced colorectal

cancer-results from NCIC CTG/AGITG CO.17. Clin Cancer Res.

20:744–753. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mounjid C, El Agouri H, Mahdi Y, Laraqui

A, Chtati E, Ech-charif S, Khmou M, Bakri Y, Souadka A and Souadka

BE: Assessment of KRAS and NRAS status in metastatic colorectal

cancer: Experience of the national institute of oncology in rabat

morocco. Ann Cancer Res Ther. 30:80–84. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zanatto RM, Santos G, Oliveira JC,

Pracucho EM, Nunes AJF, Lopes-Filho GJ and Saad SS: Impact of kras

mutations in clinical features in colorectal cancer. Arq Bras Cir

Dig. 33:e15242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Taïeb J, Emile JF, Malicot K, Zaanan A,

Tabernero J, Mini E, Rougier P, Van Laethem JL, Bridgewater JA,

Folprecht G, et al: Prognostic value of KRAS exon 2 gene mutations

in stage III colon cancer: Post hoc analyses of the PETACC8 trial.

J Clin Oncol. 32:3549. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Ounissi D, Weslati M, Boughriba R, Hazgui

M and Bouraoui S: Clinicopathological characteristics and

mutational profile of KRAS and NRAS inTunisian patients with

sporadic colorectal cancer. Turkish J Med Sci. 51:148–158.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Mahdi Y, Khmou M, Souadka A, Agouri H El,

Ech-charif S, Mounjid C and Khannoussi B El: Correlation between

KRAS and NRAS mutational status and clinicopathological features in

414 cases of metastatic colorectal cancer in Morocco: The largest

North African case series. BMC Gastroenterol. 23:1932023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Irahara N, Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, Yan

L, Dias-Santagata D, Iafrate AJ, Fuchs CS, Haigis KM and Ogino S:

NRAS mutations are rare in colorectal cancer. Diagnostic Mol

Pathol. 19:157–163. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chang YY, Lin PC, Lin HH, Lin JK, Chen WS,

Jiang JK, Yang SH, Liang WY and Chang SC: Mutation spectra of RAS

gene family in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 212:537–544.e3. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Shen Y, Wang J, Han X, Yang H, Wang S, Lin

D and Shi Y: Effectors of epidermal growth factor receptor pathway:

The genetic profiling of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS mutations in

colorectal cancer characteristics and personalized medicine. PLoS

One. 8:e816282013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Jouini R, Ferchichi M, BenBrahim E, Ayari

I, Khanchel F, Koubaa W, Saidi O, Allani R and Chadli-Debbiche A:

KRAS and NRAS pyrosequencing screening in Tunisian colorectal

cancer patients in 2015. Heliyon. 5:e013302019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, Gibbs P, Jiang

ZQ, Lieu CH, Agarwal A, Maru DM, Sieber O and Desai J: Impact of

BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of

metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer.

Cancer. 117:4623–4632. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|