Introduction

Although cancer treatment has made great progress,

it is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1,2).

According to data from the Global Cancer Report, ~19.3 million new

cancer cases and ~10 million cancer death cases occurred worldwide

in 2020, including ~4.57 million new cancer cases and ~3 million

cancer deaths in China alone (3).

With improvements in medical treatments, traditional

cancer therapies, such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy,

have evolved. Although these treatments can inhibit the growth of

tumor cells, there are certain harmful effects on normal cells

(4–7). Due to the heterogeneity of cancer,

gene mutations of different cancer cells in patients with the same

type of tumor are not necessarily the same, resulting in increased

difficulties in cancer treatment (8). Drugs that improve cancer treatment

effects and reverse drug resistance have become the focal point in

the current research on drug-resistant tumors (9–14).

However, due to the interactions between different drugs, the

efficacy of combination therapy remains suboptimal in clinical

practice (15) and there are still

adverse reactions caused by chemotherapy (16). Therefore, it is necessary to perform

further research to develop safe and effective cancer

treatments.

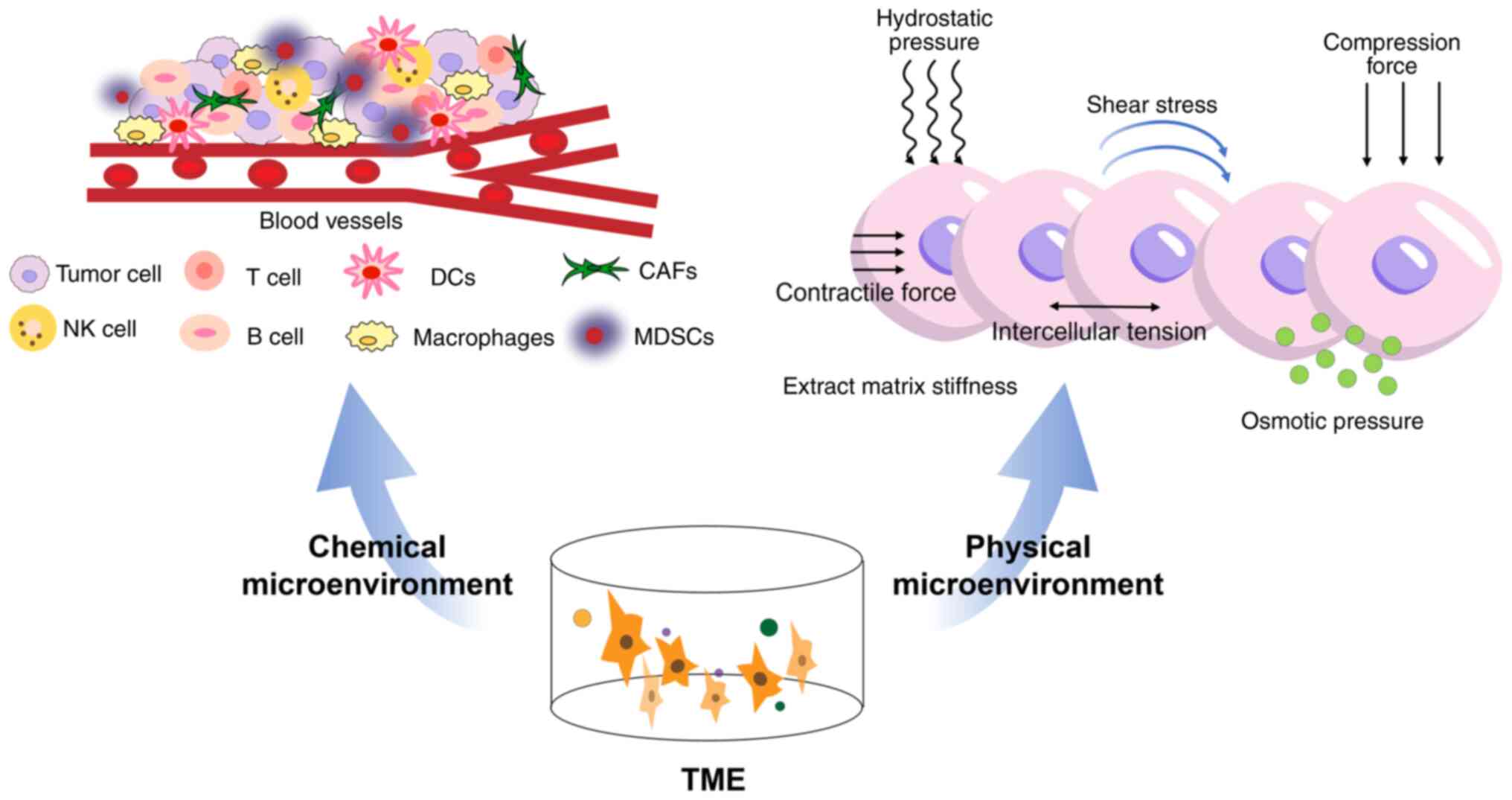

The tumor microenvironment (TME) refers to the

surrounding microenvironment in which tumor cells exist, including

surrounding blood vessels, immune cells, cancer-associated

fibroblasts, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, signaling molecules

and the extracellular matrix (Fig.

1) (17). The interaction

between tumor cells and the microenvironment can be a molecular

target for tumor therapy. The cellular and molecular composition

corresponding to the TME and the chemical and physical factors

involved in tumor growth have attracted increased research

interest. Multiple studies have confirmed that the TME's cellular

and molecular composition affects tumor cell growth, invasion and

metastasis (18–21).

| Figure 1.Composition of the TME. The TME is

composed of the chemical microenvironment and the physical

microenvironment. The chemical microenvironment is populated by

numerous diverse cell types, including blood vessels, and immune

cells, e.g., T and B cells, DCs, NK cells, MDSCs, CAFs and

macrophages. The physical microenvironment includes osmotic

pressure, intercellular tension, contractile force, shear stress,

hydrostatic pressure, compression force and extract matrix

stiffness. TME, tumor microenvironment; DCs, dendritic cells; NK,

natural killer; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; CAF,

cancer-associated fibroblasts. |

Immunotherapy is a novel cancer therapy method

(22). Immune cells in the immune

system, such as natural killer (NK) cells, serve an important role

in tumor immunotherapy and interact with the TME to inhibit the

growth of tumor cells (Fig. 1)

(23). A number of studies have

focused on genetic and biochemical factors as the causes of

malignant tumors (20,21). However, physical factors in the TME

have not been widely studied (24).

Tumor cells are typically confined to specific microenvironments

and changes in physical factors in the TME will also affect the

behavior of tumor cells, such as solid stresses generated by tumor

growth (25). Therefore, the

changing characteristics of physical factors in the

microenvironment also serve a key role in tumor development.

Physical therapy for tumors, by changing the living

environment of tumor cells through physical means, may become a new

and effective treatment strategy that can be used to treat most

types of tumor diseases. The present review aimed to summarize the

mechanisms of application of physical stimuli such as pressure,

temperature, light, sound and other therapies, in tumor treatment,

to provide a basis for new treatments and research on tumors.

Pressure

Over the past decades, studies have reported the

critical role of mechanics in the TME (26,27).

Cells in tissues such as the heart, lung and skeleton encounter

nanoscale to macroscale forces that are integral to their function,

such as the shear stress induced by blood flow on a vessel wall

(Fig. 1) (28). Cancer cells have been reported to be

fibrosis of normal cells; the cellular architecture in tumors is

severely altered and is typically characterized by a stiffened

extracellular matrix (29). Cells

can sense exogenous forces through mechanical transduction and

transform them into biological signals (30). The TME affects the growth of tumor

cells through physical and chemical stimulation (31) and responds to changes the tumor

cells in the TME. Mechanical factors include contractile force,

shear stress, hydrostatic pressure, intercellular tension and

extracellular matrix stiffness. Changes in mechanical factors in

the TME can affect tumor transformation, invasion and metastasis

(32). Therefore, the study of

tumor mechanics may be a future direction for developing

tumor-targeted drugs. When analyzing the force on cells from a

microscopic perspective, the cells are affected by two sets of

balancing forces: Gravity and supporting force; the swelling

pushing force of osmotic pressure on the cell membrane and the

pulling force of the cytoskeleton pulling the cell membrane inward

(Fig. 1). Gravity and support are

weak and negligible. The balance between the swelling force of

osmotic pressure and the pulling force of the cytoskeleton is a

basis for cell survival. If this mechanical balance is destroyed,

changes in the cellular microenvironment occur, affecting the

biological function of the cell, including tumor cells. Pressure

therapy can be divided into high-pressure therapy (HHP) and

negative-pressure therapy (NP). HHP induces immunogenic cell death

(ICD) in tumor cells and shows broad prospects in developing tumor

vaccines and enhancing tumor cell sensitivity. NP uses the defects

in the osmotic pressure regulation ability of tumor cells to

rupture the cell membrane by reducing the external pressure

environment, thereby selectively killing tumor cells without

damaging normal cells.

HHP

HHP was first used to inactivate microorganisms in

milk (33). It can damage microbial

cell membranes and cell walls, change the cell morphology, affect

intracellular enzyme activity and transport intracellular nutrients

and waste, thereby killing spoilage and pathogenic bacteria in food

(34). HHP technology is widely

used in numerous industries, including food preservation and

sterilization and also biotechnology fields, such as

pharmaceuticals.

In recent years, research on the effect of HHP on

tumor cells has been increasing. HHP can induce the ICD of tumor

cells. Immunogenic cell death is a type of regulatory cell death

that can activate the host to generate adaptive immune responses.

The ability to reshape the TME through multiple mechanisms may

increase the success of immunotherapy (35). HHP-induced immunogenic cell death is

driven by excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which

triggers a rapid integrated stress response, protein kinase R-like

endoplasmic reticulum kinase-mediated eukaryotic translation

initiation factor 2 subunit-α (eIF2α) phosphorylation and the

sequential activation of caspases-2, −8 and −3 (36). Fucikova et al (37) reported that HHP rapidly induced the

surface expression of heat shock protein (HSP)70, HSP90 and

calreticulin, while also promoting the release of high-mobility

group box 1 and ATP. In addition, HHP treatment activated key

features of the endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptotic

pathway, including ROS production, eIF2α phosphorylation and

caspase-8 activation. HHP has also been reported as a production

technology for tumor vaccines. HHP-treated cells can be

cryopreserved and retain their immunogenicity. In addition,

clinical trials have reported that HHP-treated tumor vaccines

induce specific immune responses to tumor cells (Fig. 2) (38).

Although HHP has shown potential in cancer

treatment, it faces several limitations. HHP is mainly used in

vitro, while precise in vivo methods are yet to be

developed. HHP remains experimental, lacking established treatment

guidelines. Further research is needed to optimize pressure

control, improve application techniques and explore combination

therapies to enhance safety and effectiveness.

NP

The cell membrane is a semi-permeable lipid bilayer,

and the cytoskeleton and sodium and potassium pump of tumor cells

are abnormal, which may lead to a decrease in the osmotic pressure

regulation ability of tumor cells. Atmospheric pressure is one of

the environmental factors necessary for the survival of life. The

different types of tissues and cells in the body have different

levels of adaptability to the living environment. Compared with

normal cells, the cytoskeleton and sodium and potassium pump of

malignant tumor cells are abnormal. Malignant tumor cells have a

decreased ability to control their intracellular osmotic pressure

compared with normal cells and are less tolerant of hypotonic

stress. As atmospheric pressure and intracellular osmotic pressure

exert opposite effects, the osmotic pressure regulation function of

tumor cells is impaired. If the cells are in an environment with

low atmospheric pressure, tumor cells rupture and die before normal

cells (39). It has been reported

that NP inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of pancreatic

cancer cells (40). Furthermore,

applying NP after injecting synthetic severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 DNA vaccine in rats improved the immune

effect of the vaccine (Fig. 2)

(41). Although there is currently

a scarcity of research on the effects of NP on tumor cells, the

hypothesis that NP kill tumor cells without affecting normal cells

appears feasible. This may potentially be a new research direction

for tumor treatment.

Temperature

Environmental temperature is a critical factor that

influences the viability of organisms. When the environmental

temperature of tumor cells reaches ~50°C, cells experience thermal

damage. When the temperature reaches 55°C, collagen denatures,

whereas when the temperature is >60°C, cellular structures such

as mitochondria change and tumor cells begin to undergo necrosis.

On the contrary, when the temperature drops from −4 to −21°C, ice

crystals form outside the tumor cells and the cells begin to

dehydrate. When the temperature drops to −40°C, homogeneous ice

crystals form inside the cells, which is critical for cell death.

Therefore, temperature changes have an impact on the viability of

tumor cells. According to the different modes of temperature

action, temperature therapy is divided into hyperthermia and

cryotherapy. Hyperthermia changes tumor cell membrane permeability,

protein denaturation and DNA synthesis, thereby inducing cell

apoptosis or necrosis. Cryotherapy results in mechanical damage to

the cell membrane, thereby inducing tumor cell necrosis and

apoptosis. The subsequent review sections will introduce the

mechanism of action, research progress and clinical application of

thermotherapy and cryotherapy to provide a theoretical and

experimental basis for further exploring the potential of

temperature therapy in tumor treatment.

Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia, a treatment that increases the

temperature to 39–45°C to induce cell death through apoptosis or

necrosis (42), is a low-toxic

tumor treatment, which is currently used clinically. According to

different heating techniques and heating locations, hyperthermia

techniques are divided into whole-body hyperthermia (43), local hyperthermia and local-regional

hyperthermia (44). Whole-body

hyperthermia is a widely explored approach in oncology, where the

body temperature is elevated to 38.5–41.5°C and maintained for a

certain period. This is typically achieved using non-invasive

surface heating methods, such as infrared electromagnetic waves,

which penetrate the subcutaneous layer and directly heat the blood

in the capillaries, thereby raising the overall body temperature.

Various techniques have been developed for local hyperthermia to

target tumor tissues more precisely while minimizing harm to normal

tissues. These include infrared water window heating, intracavitary

hyperthermia and high-intensity focused ultrasound (45).

Hyperthermia indirectly kills tumor cells. Heating

causes reactive expansion of blood vessels in normal tissue around

the tumor, which causes further reduction of blood flow in the

tumor tissue, leading to hypoxia in the tumor tissue. This induces

a state of hypoxia, hyponutrition and low blood flow for an

extended period of time, causing the accumulation of lactic acid

and inducing TME changes. The pH drops, inducing tumor acidosis

(46). Hyperthermia can also

upregulate the expression levels of HSP70, thereby increasing the

immune antigenicity of tumor cells, inhibiting their proliferation

and migration and inducing tumor cell death (47). In mouse models of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma, hyperthermia can upregulate the expression levels of

HSPA5, downregulate CD55 expression levels through HSPA5/NF-κB

signal transduction and activation of the complement cascade and

inhibit tumor development (Fig. 3)

(48).

Hyperthermia can also directly kill tumor cells, as

it can inhibit the synthesis of RNA, DNA and protein, preventing

the proliferation of tumor cells (46). When the temperature of the body is

maintained at >40°C for a certain period of time, the

cytoskeleton of tumor cells is destroyed, causing their protein to

denature and cell complex enzymes to be affected, thus inhibiting

the DNA synthesis process until the cells die. It has also been

shown that hyperthermia can induce apoptosis of tumor cells by

activating the caspase family of proteins (Fig. 3) (49).

Hyperthermia increases the efficacy of chemotherapy

and radiotherapy. Hyperthermia and radiotherapy have different

sites of action in the cell proliferation cycle. Hyperthermia

mainly affects S-phase cells (46),

whereas radiotherapy mainly affects G1 and

G2/M phase cells (50).

The combination of the two has synergistic effects on the cell

cycle. A study on breast cancer cells showed that radiofrequency

heating at 13.56 MHz and 43°C for 20 min significantly reduced the

S-phase cell population, while at the same time significantly

increasing the G2/M-phase cell population, enhancing the

efficacy of radiotherapy (51). Of

all types of DNA damage, DNA double-strand breaks are considered

the most harmful (52). Heating can

cause double-stranded DNA breaks or reduce DNA damage repair

(53). The ionization effect of

radiation in organisms exerts its killing effect on tumor cells by

directly or indirectly causing cell DNA strand breaks. DNA is the

main target of ionizing radiation and ionizing radiation has a

cytotoxic effect, causing single- and double-strand DNA breaks

(54). Although radiation causes a

certain degree of direct killing effect on tumor vascular

endothelial cells, it also induces the expression of vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF), making tumor vessels more

resistant to radiation. Hyperthermia can inhibit the expression of

tumor-derived VEGF and its products, thereby hindering the

proliferation of tumor vascular endothelium and reshaping of

extracellular matrix, inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis. Liang

et al (55) reported that

hyperthermia can inhibit VEGF gene expression and protein synthesis

levels, indicating that heating can inhibit the proliferation of

endothelial cells and the formation of tumor neovascularization,

thereby enhancing the radiation effect on tumors. Heating changes

the permeability of cell membranes, making it easier for drugs to

enter tumor cells and improving the penetration and absorption of

chemotherapeutic drugs. Therefore, hyperthermia and

chemotherapeutic drugs serve a synergistic role in increasing the

cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs and exerting antitumor

effects. In addition, hypoxia in tumor cells is an important factor

leading to drug resistance. Therefore, adding hyperthermia

treatment alongside chemotherapy can also eliminate chemotherapy

resistance and improve the efficacy of drugs (Fig. 3) (56).

As a supplement to existing tumor treatment plans,

thermotherapy has a promising prospect in the clinical treatment of

advanced relapsed tumors. A meta-analysis analyzed the efficacy of

thermal radiation therapy and showed that the overall complete

response rate in the thermal radiation therapy group was 54.9%,

which was significantly higher compared with that of the single

radiation therapy group, at 39.8% (57). Although hyperthermia is a promising

cancer treatment, it has several limitations and side effects, such

as maintaining an optimal therapeutic temperature while avoiding

damage to surrounding tissues, burns, pain and thermal damage to

healthy tissues. Further studies are required to determine the

future of thermal therapy, such as expanding the application of

thermal therapy in cancer treatment, combining thermal therapy with

other treatment methods to obtain more accurate data and provide a

basis for clinical treatment.

Cold therapy

Cryoablation technology is increasingly being

utilized in the minimally invasive treatment of tumors. At present,

cryoablation technology mainly includes liquid or gas as a medium

to quickly drop the local temperature of the tumor to <-140°C to

generate ice crystals. This causes the cell membrane to rupture and

occlude the microvessels in the ablation area, resulting in

ischemia and necrosis of tumor cells. Cryoablation induces tumor

cell death through multiple mechanisms. Cryoablation can induce

cell membrane damage to tumor cells, activate the immune response,

induce apoptosis and cause vascular embolisms.

After cryoablation forms ice crystals, the cell

membrane undergoes mechanical damage and activates a series of

antitumor immune reactions, causing tumor necrosis (58). Cells that are not directly killed by

cryoablation may induce apoptosis through a pathway mediated by

mitochondria that activates the caspases family (59). Cryoablation can also cause vascular

embolism, leading to diminished blood flow to the tumor and

amplifying its cytotoxic effect on the tumor. When the temperature

drops, the tissue's extracellular fluid freezes and the development

of extracellular ice elevates the osmotic pressure external to the

cell, causing the fluid to transfer from the inside to the outside

of the cell. In this hypertonic environment, alterations in the

intracellular pH and cellular constituents may result in cellular

injury (60). Cryoablation can also

cause changes in the immune function of tumors. Cells that die due

to osmotic shock or mechanical damage from ice crystals release

their intracellular contents into the extracellular space. Numerous

types of content are immunostimulatory, such as pro-inflammatory

cytokines, HSPs and other related factors. Their receptors can

activate the immune response (61).

Studies have shown that after cryoablation, tumor antigens are

released and the activation of lysosome-related pathways leads to

the overexpression of the synaptosome-associated protein 23 and

syntaxin binding protein 2, thereby promoting the activation of

immune effector cells and suppressing the release of

immunosuppressive factors, ultimately leading to enhanced antitumor

immunity (62). In addition, Seki

et al (63) reported that

the glucose catabolic ability of brown adipose tissue is enhanced

under low-temperature environments, resulting in decreased blood

sugar and insulin tolerance. This reduces the metabolism of the

body, thereby decreasing the catabolic ability of glucose in the

tumor, inhibiting tumor growth and providing a potential new

treatment method for cancer therapy (Fig. 3).

There are numerous reports on the application of

cryoablation in numerous organs, but the effect of cryoablation

treatment using cryoablation is not identical and is closely

associated with the heterogeneity of the tumor. Guo et al

(64) summarized the clinical

application status of cryoablation, indicating that cryoablation

technology has advantages such as minimal invasiveness and fewer

complications. The cooling rate, target temperature, time at target

temperature, thaw rate and number of cycles are the main parameters

that directly affect the therapeutic effect of cryoablation

technology. In the future, auxiliary treatment of cryoablation may

rely on the optimization of these parameters to maximize the

surgical efficacy and minimize surgical complications, reducing the

tumor burden.

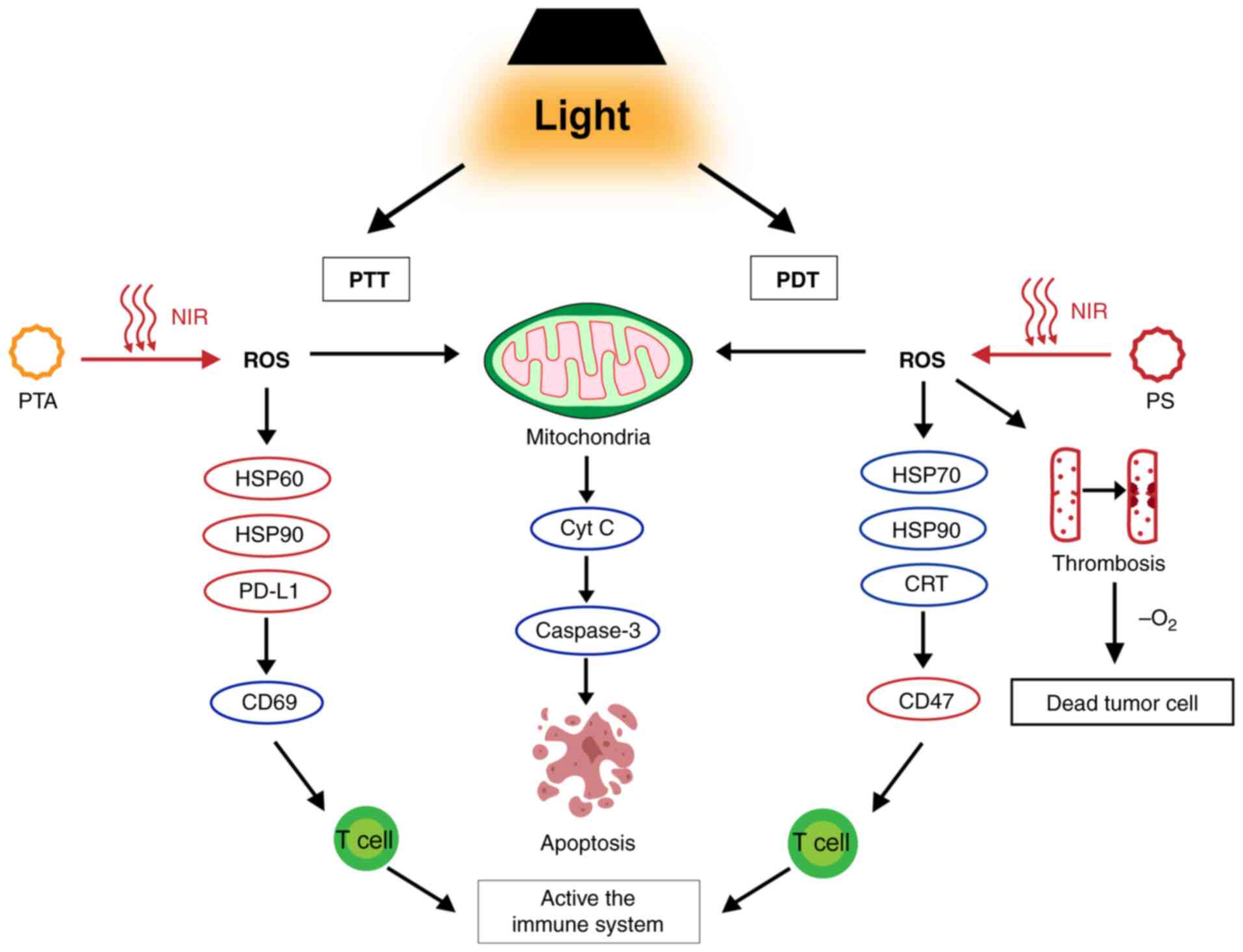

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is a method of exposing a patient to

light to treat disease. Phototherapy has been reported to be a safe

tumor treatment in a number of previous studies, mainly focusing on

photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) (65). PTT irradiates the photothermal agent

(PTA) with light at a specific wavelength, which heats the PTA and

kills tumor cells, whereas PDT produces a large number of ROS under

the specific wavelength to kill tumor cells (66). Photosensitizers are key to PDT and

PTT can improve treatment efficiency and efficacy without the

requirement of any external photothermal contrast agents (66). During clinical treatment, PTA and

photosensitizers are typically administered through intravenous or

local applications. Through active or passive targeted delivery,

they accumulate in tumor tissue and light of a specific wavelength

is used to irradiate the tumor tissue locally. The following

sections in this review will introduce the mechanism of action,

research progress and clinical application of PTT and PDT,

providing a theoretical basis and practical reference for the

further development of phototherapy in tumor treatment.

PTT

PTT uses photothermal conversion nanomaterials

targeted to tumor sites to absorb and convert light energy into

heat under near-infrared irradiation, thereby inducing tumor cell

death (67). It has become a highly

efficient and minimally invasive method for the treatment of

primary tumors (68) and has few

side effects, a high specificity and can be repeated. In PTT, PTA

enhances the heating of local cells and tissues. Through the local

use of photosensitizers and minimally invasive near-infrared

radiation, PTT-induced hyperthermia can be controlled to minimize

damage to non-targeted tissues.

As aforementioned, hyperthermia can induce tumor

cells to release antigens, pro-inflammatory cytokines and

immunogenic intracellular substrates, promoting immune activation

and causing apoptosis. PTT treatment causes effects akin to those

of hyperthermia. Ali et al (69) irradiated MCF-7 human breast cancer

cells with PTT and showed that subsequent to 2 min of laser

irradiation, the cells primarily underwent apoptosis. Further

research on biomarkers of the apoptosis pathway showed that the

mitochondrial pathway mediates PTT-induced apoptosis through

activation of Bid (70). HSPs are a

category of proteins synthesized by cells in response to stress

sources and are involved in the mechanism of PTT-induced cell

death. Wang et al (71)

synthesized indocyanine green-loaded vanadium oxide nanoparticles

(VO2NPs) for pH-activated near-infrared luminescent

imaging-guided enhanced photothermal tumor ablation. In the acidic

TME, VO2NPs decompose and release VO2+, which

inhibits the function of HSP60. PTT can also induce the activation

of immune function. Deng et al (72) loaded SNX-2112, an HSP90 inhibitor,

on a graphene oxide carrier for near-infrared (NIR) irradiation.

The results showed that NIR can induce downregulation of the

expression levels of HSP90 and programmed cell death ligand 1 in

tumor cells, whilst upregulating the expression of CD69, an

activation marker of T cells. In addition, the increase in tumor

blood flow caused by PTT also leads to an increase in microvascular

permeability and improves drug accumulation in tumors (Fig. 4) (73).

| Figure 4.Mechanism of phototherapy.

Phototherapy is categorized into PTT and PDT. PTT involves NIR

irradiation of the PTA, increases the temperature, activates

caspase-3 via the mitochondrial pathway, inhibits HSP60 and induces

cell death. It inhibits HSP90 and PD-L1, upregulates CD69 and

activates immune function. PDT involves NIR irradiation of the PS

and produces ROS, which kills cells by inducing apoptosis and

necrosis. It can form a thrombus and eventually lead to cell death.

It also upregulates HSP70, HSP90 and CRT, activating the immune

system. PTT, photothermal therapy; PDT, photodynamic therapy; NIR,

near-infrared; PTA, photothermal agent; HSP, heat shock protein;

PS, photosensitizer; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PD-L1,

programmed cell death ligand 1; Cyt C, cytochrome C; CRT,

calreticulin. |

To solve the limitations of PTT monotherapy, a

series of PTT-based combination therapies have been studied. Nam

et al (74) reported that

PTT in combination with chemotherapy can trigger effective

antitumor immunity against disseminated tumors. A

polydopamine-coated spiked gold nanoparticle, SGNP@PDA, combined

with the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, has been developed for the

chemotherapy combined with PTT. This combination therapy enhances

the antitumor effect of the drug and eliminates local and untreated

distant tumors, achieving survival rates >85% in a bilateral

mouse tumor model of CT26 colon cancer.

In clinical trials, PTT combined with immunotherapy

can produce synergistic effects, reduce primary tumors, control

untreated metastasis and prolong patient survival. It can be used

to treat various types of tumor, such as lung, breast, esophageal,

colon and bladder cancers (75).

PTT shows promise for antitumor therapy but faces certain

difficulties in the clinical application of the treatment. For

instance, in clinical practice, it is difficult to master the light

conditions required for the conversion of photosensitizers.

However, with the continuous development of nanotechnology, the

clinical progress of PTT for tumor treatments will likely improve

over time.

PDT

PDT is a relatively new minimally invasive treatment

method that relies on the selective accumulation of

photosensitizers in cancer cells to generate cytotoxic ROS when

excited by light of certain wavelengths to ultimately kill cancer

cells (76). PDT is based on three

main components: Light, photosensitizer and oxygen. There are three

mechanisms of action by which PDT destroys tumor cells: i) ROS

produced by the photochemical reaction of PDT can directly kill

cells by inducing apoptosis and necrosis; ii) PDT damages

tumor-related blood vessels, resulting in interruption of the

oxygen and nutrient supply, which leads to indirect cell death

caused by hypoxia; and iii) PDT can induce an inflammatory response

and activate the immune response against tumor cells (77).

Light activates the photosensitizer from the ground

state to the excited state and energy transfers to molecular oxygen

to form ROS. In addition to causing oxidative damage to

macromolecules in tumor cells (78), ROS can also directly kill tumor

cells by inducing necrosis or apoptosis. During PDT, most

photosensitizers destroy mitochondrial function, cause cells to

release cytochrome c and activate the caspase pathway to

induce apoptosis of tumor cells. Liu et al (79) used photosensitizer aloe-emodin

(AE)-mediated PDT to inhibit human oral squamous cell carcinoma

both in vitro and in vivo. AE-PDT can kill tumor

cells and inhibit their migration. In the PDT-treated group, the

protein expression levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-2/Bax were significantly

decreased, while the protein expression levels of Bax and Caspase-3

were significantly increased. De Miguel et al (80) studied the effect of PDT on skull and

spinal osteosarcoma in Balb/c nude mice and reported that the

volume of bone matrix increased after PDT treatment and the size of

the tumor decreased, which may be related to increased necrosis

(Fig. 4).

During PDT, when activated by light, the endothelial

cells of the tumor vascular system produce ROS, destroying the

tumor vascular endothelial cells and causing thrombosis. This

results in a series of corresponding physiological reactions, such

as the release of vasoactive molecules and increased vascular

permeability (81), leading to the

interruption of the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the tumor and

death of tumor cells. Dolmans et al (82) used the photosensitizer MV640, which

targets blood vessels, to study the mechanism of PDT damage of

tumor blood vessels. The tumor tissue showed dose-dependent effects

of this treatment, such as blood stasis, ischemia, internal tumor

hemorrhage, disappearance of blood vessels and thrombosis, and

inhibited tumor growth due to ischemia and hypoxia. Other studies

have shown that PDT can reduce the expression levels of NF-κB

through a ROS-mediated mechanism and activation of NF-κB serves an

important role in the tumor mechanism induced by blood vessel

photosensitivity (Fig. 4) (83,84).

In addition, PDT can also disrupt immune homeostasis

within tumors, activate corresponding immune and inflammatory

reactions and produce anti-tumor effects. Zheng et al

(85) performed a study of PDT in

the treatment of Lewis lung cancer in mice and showed that a large

number of damage-related proteins were released after the tumor

cells were damaged, which in turn mediated the body's antitumor

immune response (Fig. 4).

PDT has been reported to achieve clinical efficacy

in the treatment of skin, esophageal and bladder cancers. A

preliminary study demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of PDT

in patients with bladder cancer who had complete transurethral

resection and were confirmed without serious adverse reactions

(86). PDT is an effective and safe

alternative to traditional treatments with a low incidence rate of

tumors, but its widespread use is currently limited due to the high

cost of photosensitizers and light source equipment required by

PDT. Photosensitizers may also cause skin light allergies and the

tissue penetration of light is limited; therefore, PDT is

restricted in its application for certain types of deep tumor such

as glioma. With the development of new photosensitizers, light

source technologies and combined treatment strategies, PDT may have

broad future application prospects (87).

Sonodynamic therapy (SDT)

As a new non-invasive therapy derived from PDT, SDT

has been previously researched and explored. The principle of SDT

is similar to that of PDT. SDT uses low-intensity ultrasound to

stimulate disease sites, activate sonosensitizers and generate ROS,

inducing tumor cell death. Different types of sonosensitizers,

including organic molecules and inorganic nanomaterials, such as

piezoelectric materials, semiconductors and metallic materials,

have been explored over the past few years. Due to the rapid

development of nanotechnology, a variety of nanomaterials have been

prepared into sonosensitizers or nanocarriers for sonosensitizers,

markedly improving the targeting, stability and biological safety

of sonosensitizers. Chen et al (88) used stanene-based nanosheets as

nano-sound sensitizers to enhance the antitumor efficacy of SDT.

The antitumor mechanism of SDT occurs under low-intensity

ultrasound irradiation as the caspase pathway is activated and

apoptosis of tumor cells is induced. Li et al (89) reported that sinoporphyrin

sodium-mediated SDT significantly increased intracellular ROS. The

elevated production of ROS increases the expression levels of p53

and Bax while suppressing Bcl-2 expression, resulting in the

activation of caspase-3 and ultimately triggering cellular

apoptosis. Yang et al (90)

reported that SDT mediates and induces apoptosis, which is related

to the formation of cell membrane pores caused by the destruction

and cavitation effect of microbubbles (Fig. 5).

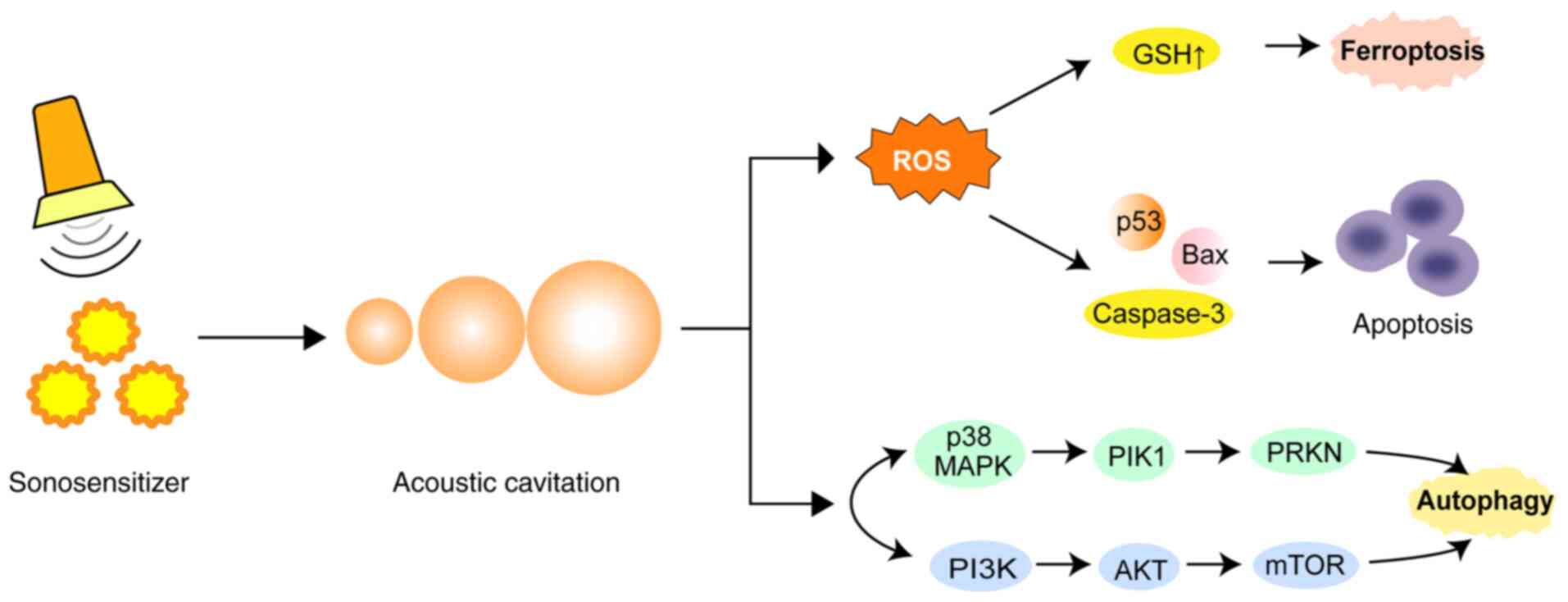

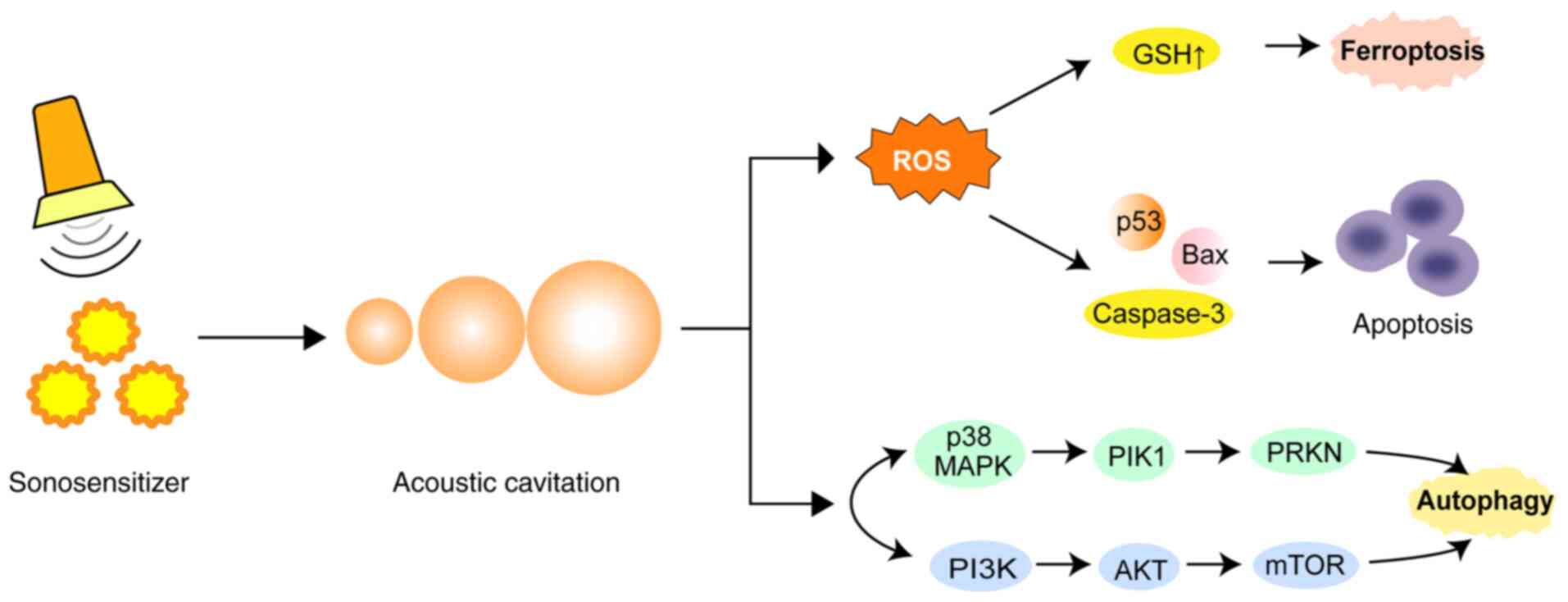

| Figure 5.Mechanism of sonosensitizers. SDT can

mediate the antitumor response, activates sonosensitizers and

generates ROS through apoptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy, thereby

inducing tumor cell death. SDT, sonodynamic therapy; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; GSH, glutathione;

p53, tumor protein p53; Bax, bcl-2-associated × protein; p38, tumor

protein p38; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PIK1,

PTEN-induced kinase 1; PRKN, parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein

ligase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B;

mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin. |

Autophagy is the process of degradation of proteins

or organelles within cells and is an important defensive and

protective mechanism of cells (91). Autophagy starts from the endoplasmic

reticulum and regulates the formation of autophagy bodies under the

collaborative action of the UNC51-like kinase-1 kinase, PI3K and

autophagy-related protein 9 complexes (92,93).

It has been shown that SDT can induce autophagy through the

MAPK/p38-PTEN-induced putative kinase 1-parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin

protein ligase mitochondrial autophagy and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways

(94). Ferroptosis is a

non-apoptotic regulated cell death caused by iron accumulation and

subsequent lipid peroxidation (95). Sun et al (96) prepared a metal-organic framework

biomimetic nanosystem, mFeP@si, as a

sonosensitizer, mediating the rupture of lysosomal membranes to

achieve lysosomal escape, accelerating ROS production and

glutathione depletion and further triggering iron death (Fig. 5).

As an emerging technology, SDT is still in the

exploration stage. Research on SDT in brain tumors, such as

glioblastoma, is underway and preliminary results show that SDT can

penetrate the blood-brain barrier and has potential therapeutic

value (97). Despite facing

challenges, such as sound sensitizer development and ultrasound

parameter optimization, SDT may potentially become an important

supplementary therapy for the treatment of tumors as research

progresses. In the future, the scale of clinical trials needs to be

further expanded to verify their safety and efficacy.

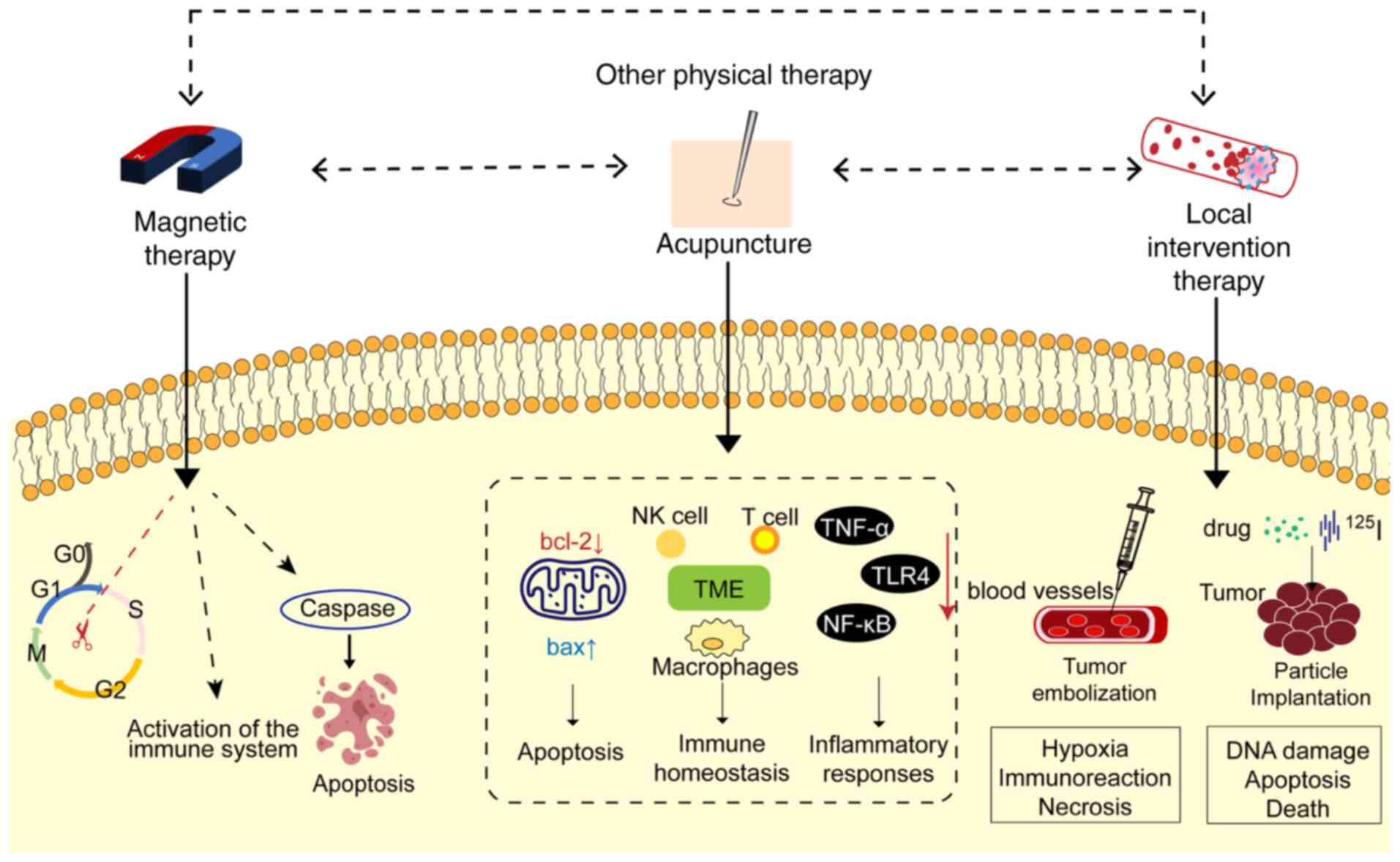

Other new therapies

With continuous tumor treatment research, other

types of new physical therapies have also attracted attention.

These include magnetic therapy, acupuncture and local

interventional therapy, which impact the growth, invasion and

metastasis of tumor cells through different biophysical mechanisms.

The following sections will introduce the mechanisms of action of

these novel therapies and their potential applications in tumor

therapy.

Magnetic therapy

Magnetic therapy involves an external physical

stimulus and produces complex biological effects. It has been shown

that appropriate magnetic field stimulation can prevent

inflammation and oxidative stress and alleviate or repair

neurological damage, and magnetic fields may have protective

effects in various diseases. Magnetic therapy for cancer includes

pulsed electric field (PEF) and pulsed electromagnetic field

(PEMF).

The PEF is generated by applying a voltage to two

electrodes. Under the action of PEF, the permeability of the cell

membrane increases, causing mitochondrial vacuoles to produce and

release cytochrome c. When acting on the nucleus, DNA double

strand breakage may occur. PEF can block the transfer of cells from

G0/G1 phase to S+G2/M phase.

Kulbacka et al (98)

reported that nanosecond PEF reverses drug resistance in gastric

cancer cells by inducing oxidative stress and apoptosis. PEF can

also regulate immune function and induce antitumor effects. Pastori

et al (99) showed that PEF

has an immunomodulatory effect on a breast cancer model of mice,

inhibiting tumor growth and improving the survival rate of mice

(Fig. 6).

PEMF is used to treat various diseases, including

osteoarthritis (100) and

Parkinson's disease (101). Both

in vitro and in vivo research on PEMF-related tumors

is becoming more widespread. PEMF can inhibit cell proliferation,

block tumor angiogenesis, alter the cell cycle, directly kill or

induce tumor cell apoptosis and exert antitumor effects. Filipovic

et al (102) studied the

effect of a 50-Hz magnetic field on different cancer cell systems,

indicating that PEMF therapy has an antiproliferative effect, which

inhibits cell division by destroying the mitotic spindle structure,

leading to chromosome separation errors and inducing apoptosis. Guo

et al (103) reported that

the cell cycle of cancer cells is affected under low-frequency

magnetic fields. PEMF also increases doxorubicin-induced DNA damage

by inhibiting DNA topoisomerase II alpha. In another study, 8 Hz

PEMF was used to irradiate MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer

epithelial cells and FF95 normal fibroblasts. It was found that the

proliferation rate and activity of breast cancer cells were

reduced, whilst the death and aging of breast cancer cells were

induced (Fig. 6) (104).

Currently, the clinical application of PEMF is

limited and Barbault et al (105) published the first report using

PEMF therapy and magnetic fields of specific frequencies to show

the therapeutic effect of PEMF in local tumor treatment. Clinical

research has also revealed that PEMF relieves pain associated with

cancer (106). Although the

biological effects of PEMF have been verified in certain studies,

its specific mechanism still needs to be explored in depth. PEMF

therapy provides a safe and well-tolerated approach for tumor

treatment.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture involves the stimulation of certain

acupoints, activating peripheral nerves, sending sensory

information from the spinal cord to the brain, engaging peripheral

autonomic nerve pathways and modulating the body's physiological

state (107). According to the

concepts of Traditional Chinese Medicine, acupuncture has the

functions of strengthening the body, dredging the meridians,

promoting the movement of qi and blood and harmonizing the visceral

organs. Clinical studies on the treatment of tumor complications

with acupuncture have shown that acupuncture can effectively

improve the symptoms of tumor complications and delay the growth of

tumors to a certain extent, acting as a safe and efficient physical

therapy method (108). Acupuncture

primarily exerts an antitumor effect by enhancing and optimizing

the tumor immune microenvironment, improving the local angiogenesis

of the tumor and promoting tumor cell apoptosis. In the immune

microenvironment, NK cells, CD8+ T cells,

CD4+ T cells, macrophages and related cytokines are

associated with the treatment of tumors by acupuncture and

moxibustion (109). A study using

Lewis lung cancer model mice showed that acupuncture and

moxibustion can promote the production of NK cells by regulating

adrenergic signals, restoring the immune homeostasis of the body

and improving its antitumor capabilities (110). Electroacupuncture at ‘Zusanli’ can

alleviate renal injury in mice with colorectal cancer after

5-fluorouracil chemotherapy, and its mechanism of action may be

related to regulating renal oxidative stress, reducing the

inflammatory response and inhibiting apoptosis (111). Acupuncture may also reduce the

overexpression of NF-κB and the excessive release of inflammatory

factors by inhibiting the overexpression of TNF-α and Toll-like

receptor 4, thereby reducing the occurrence of liver inflammation

in cis-diaminodichloroplatinum (DDP) mice, reducing the side

effects of DDP on the liver and serving an effective role in liver

protection (112). Acupuncture can

significantly reduce the protein expression levels of Bcl-2 in

tumor cells of tumor-bearing mice, increase the protein expression

levels of Bax, reduce the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax and promote tumor cell

apoptosis (113). Previous

clinical studies have reported that acupuncture and moxibustion

have an effect on the symptoms associated with tumors, including

gastrointestinal adverse reactions (114), cancerous pain (115), insomnia (116) and anxiety (117). Therefore, the use of acupuncture

and moxibustion to treat tumors may provide new ideas for clinical

practice, providing a basis for further study (Fig. 6).

Local intervention therapy

As a type of tumor physical therapy, local

interventional therapy relies on imaging guidance to accurately

deliver the therapeutic device to the tumor site, achieving direct

effects on the lesions, including tumor embolization and granule

implantation.

Tumor embolization is an imaging-guided local

interventional treatment method. This involves injecting

embolization materials or drugs directly into the tumor blood

supply artery, blocking the tumor blood supply and inducing hypoxic

necrosis. The tumor blood supply artery is selectively blocked by

embolizers and forms a thrombus to induce tumor hypoxia and

nutritional deficiency (118).

Cancer cells in a stressed state can affect cell migration,

angiogenesis and metastasis by activating the antitumor immune

response. It has been reported that in a rat model of liver cancer,

hepatocellular carcinoma cells develop hypoxia stress due to

embolisms (119). Avritscher et

al (120) reported that after

embolization treatment, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and IL-17

expression levels in type 17 T-helper cells increased, activating

the antitumor immune response and reducing cell migration. Tumor

embolization has important clinical value in a variety of solid

tumors. Maclean et al (121) used a novel absorbable gel

microsphere to embolize 23 patients undergoing uterine fibroid

embolization. These results showed that tumor necrosis occurred in

83% of the patients (Fig. 6).

Particle implantation treatment achieves precise

local treatment by implanting radioisotope or antitumor drug

carrier microparticles directly into the tumor. Granule

implantation treatment depends on the role of radioactive or drug

particles in the tumor. The implanted particles act directly on

tumor cells, causing DNA damage and further inducing apoptosis.

Zhang et al (122) showed that implanting

125I radioactive particles in a mouse model of liver

cancer upregulated the expression levels of proinflammatory

cytokines in cancer cells and enhanced cytokine-induced killer

cell-mediated apoptosis by activating caspase-3. In a retrospective

study, 27 patients with bone metastatic tumors were treated with

125I particles to treat pain relief after surgery

without any serious complications (Fig.

6). Local interventional treatment has few complications.

Through precise positioning, it provides minimally invasive and

individualized treatment plans for patients with solid tumors, but

it also has limitations (123). In

the future, through strategies such as the combination of drugs,

immunotherapy and improving drug delivery, this treatment may

improve the efficacy of tumors, reduce adverse reactions and

provide more accurate and efficient individualized treatment plans

for patients with refractory tumors.

Conclusion and perspectives

Tumors cause a multi-factor, long-term type of

disease. In certain cases, it is impossible to completely kill all

tumor cells, which can lead to excessive medical treatments

administered to patients. Compared with other diseases, the

currently existing measures such as surgery, radiotherapy,

chemotherapy and biotherapy do not have high efficacy rates.

Therefore, finding new types of effective treatments is of high

priority. With the advancement of the social economy, science and

technology, modern mechanized manufacturing provides material

guarantee and infinite possibilities for physiotherapy. Instruments

and equipment can be used repeatedly and their applications in

healthcare are more promising compared with chemotherapy.

Physiotherapies may potentially be used in palliative therapy for

advanced tumors, due to their decreased side effects and the low

cost of treatment (124).

Physical therapy, as an emerging cancer treatment

method, has become a research hotspot. Compared with application

bottlenecks associated with treatments such as chemotherapy and

biotherapy, physical therapy can achieve precise localized

treatment with minimal systemic toxicity and side effects. The

present review summarized the antitumor mechanisms of physical

therapy methods such as pressure, temperature, light, sound and

magnetism, demonstrating the broad research potential and

applicability of physical therapy for tumors. Although physical

therapy has made significant progress in experimental research,

there are relatively few clinical trials for these treatment types.

First, clinical trials are limited to the current level of

understanding and technology. Second, within a certain range, the

degree of influence of physical factors is insufficient. Since

physical therapy often relies on instruments and materials that

alter the internal physical factors of tumors, further basic and

clinical research is required to determine the mechanism of action

of physical therapy in tumor treatment and its potential for

clinical applications. Future research on the physical therapy of

tumors may provide a strong scientific basis for the use of these

therapeutic methods in the treatment of tumors.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Project of Technology

Department of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2021C03087), Project of

Medical and Health Research Program of Zhejiang Province (grant no.

2022PY084), Project of Science and Technology on Traditional

Chinese Medicine of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2021ZB185) and the

National Training Program of Innovation and Entrepreneurship for

Undergraduates (grant no. 202310346078X).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JX, CJ and GC were involved in the conception and

design of the study, drafting and revision of the manuscript and

preparation of the figures. HS, YW, CS, ShaL, TY, YS, YL and YF

drafted and revised the manuscript. QZ, ShuL and TX revised the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhai B, Chen P, Wang W, Liu S, Feng J,

Duan T, Xiang Y, Zhang R, Zhang M, Han X, et al: An

ATF24 peptide-functionalized β-elemene-nanostructured

lipid carrier combined with cisplatin for bladder cancer treatment.

Cancer Biol Med. 17:676–692. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhou J, Kang Y, Gao Y, Ye XY, Zhang H and

Xie T: β-Elemene inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in

non-small cell lung cancer by targeting ALDH3B2/RPSA axis. Biochem

Pharmacol. 232:1167092025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zraik IM and Heß-Busch Y: Management of

chemotherapy side effects and their long-term sequelae. Urologe A.

60:862–871. 2021.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chaudary N, Hill RP and Milosevic M:

Targeting the CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway to reduce radiation treatment

side effects. Radiother Oncol. 194:1101942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen P, Wu Q, Feng J, Yan L, Sun Y, Liu S,

Xiang Y, Zhang M, Pan T, Chen X, et al: Erianin, a novel dibenzyl

compound in Dendrobium extract, inhibits lung cancer cell growth

and migration via calcium/calmodulin-dependent ferroptosis. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 5:512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bai R, Zhu J, Bai Z, Mao Q, Zhang Y, Hui

Z, Luo X, Ye XY and Xie T: Second generation β-elemene nitric oxide

derivatives with reasonable linkers: Potential hybrids against

malignant brain glioma. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 37:379–385. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yu SX, Liang ZM, Wu QB, Shou L, Huang XX,

Zhu QR, Xie H, Mei RY, Zhang RN, Zhai XY, et al: A novel diagnostic

and therapeutic strategy for cancer patients by integrating Chinese

medicine syndrome differentiation and precision medicine. Chin J

Integr Med. 28:867–871. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tan T, Feng Y, Wang W, Wang R, Yin L, Zeng

Y, Zeng Z and Xie T: Cabazitaxel-loaded human serum albumin

nanoparticles combined with TGFβ-1 siRNA lipid nanoparticles for

the treatment of paclitaxel-resistant non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancer Nanotechnol. 14:702023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Xu YX, Chen YM, Zhang MJ, Ren YY, Wu P,

Chen L, Zhang HM, Zhou JL and Xie T: Screening of anti-cancer

compounds from Vaccariae Semen by lung cancer A549 cell fishing and

UHPLC-LTQ Orbitrap MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life

Sci. 1228:1238512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sui X, Zhang M, Han X, Zhang R, Chen L,

Liu Y, Xiang Y and Xie T: Combination of traditional Chinese

medicine and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase

inhibitors in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore).

99:e206832020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li J, Zeng H, You Y, Wang R, Tan T, Wang

W, Yin L, Zeng Z, Zeng Y and Xie T: Active targeting of orthotopic

glioma using biomimetic liposomes co-loaded elemene and cabazitaxel

modified by transferritin. J Nanobiotechnology. 19:2892021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu S, Li Q, Li G, Zhang Q, Zhuo L, Han X,

Zhang M, Chen X, Pan T, Yan L, et al: The mechanism of

m6A methyltransferase METTL3-mediated autophagy in

reversing gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cells by β-elemene. Cell

Death Dis. 11:9692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen P, Li X, Zhang R, Liu S, Xiang Y,

Zhang M, Chen X, Pan T, Yan L, Feng J, et al: Combinative treatment

of β-elemene and cetuximab is sensitive to KRAS mutant colorectal

cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting

epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Theranostics. 10:5107–5119.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gao Q, Feng J, Liu W, Wen C, Wu Y, Liao Q,

Zou L, Sui X, Xie T, Zhang J and Hu Y: Opportunities and challenges

for co-delivery nanomedicines based on combination of

phytochemicals with chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer treatment. Adv

Drug Deliv Rev. 188:1144452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Guo X, Wen T and Qu X: Research progress

of adverse events related to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors based

combination therapy. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 24:513–518. 2021.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sung SY, Hsieh CL, Wu D, Chung LWK and

Johnstone PAS: Tumor microenvironment promotes cancer progression,

metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Curr Probl Cancer.

31:36–100. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tung JC, Barnes JM, Desai SR, Sistrunk C,

Conklin MW, Schedin P, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ, Seewaldt VL and

Weaver VM: Tumor mechanics and metabolic dysfunction. Free Radic

Biol Med. 79:269–280. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xian J, Xiao F, Zou J, Luo W, Han S, Liu

Z, Chen Y, Zhu Q, Li M, Yu C, et al: Elemene hydrogel modulates the

tumor immune microenvironment for enhanced treatment of

postoperative cancer recurrence and metastases. J Am Chem Soc.

146:35252–35263. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kang N, Gao H, He L, Liu Y, Fan H, Xu Q

and Yang S: Ginsenoside Rb1 is an immune-stimulatory agent with

antiviral activity against enterovirus 71. J Ethnopharmacol.

266:1134012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang W, Jia M, Lian J, Lu S, Zhou J, Fan

Z, Zhu Z, He Y, Huang C, Zhu M, et al: Inhibition of TANK-binding

kinase1 attenuates the astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammatory

response through YAP signaling after spinal cord injury. CNS

Neurosci Ther. 29:2206–2222. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen L, He Y, Zhu J, Zhao S, Qi S, Chen X,

Zhang H, Ni Z, Zhou Y, Chen G, et al: The roles and mechanism of

m6A RNA methylation regulators in cancer immunity.

Biomed Pharmacother. 163:1148392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hu J, Yang Q, Yue Z, Liao B, Cheng H, Li

W, Zhang H, Wang S and Tian Q: Emerging advances in engineered

macrophages for tumor immunotherapy. Cytotherapy. 25:235–244. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu Q, Luo Q, Ju Y and Song G: Role of the

mechanical microenvironment in cancer development and progression.

Cancer Biol Med. 17:282–292. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shieh AC: Biomechanical forces shape the

tumor microenvironment. Ann Biomed Eng. 39:1379–1389. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mbeunkui F and Johann DJ Jr: Cancer and

the tumor microenvironment: A review of an essential relationship.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 63:571–582. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Raudenská M, Navrátil J, Gumulec J and

Masařík M: Mechanobiology of cancerogenesis. Klin Onkol.

34:202–210. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Butcher DT, Alliston T and Weaver VM: A

tense situation: Forcing tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:108–122. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Egeblad M, Rasch MG and Weaver VM: Dynamic

interplay between the collagen scaffold and tumor evolution. Curr

Opin Cell Biol. 22:697–706. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hamill OP and Martinac B: Molecular basis

of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol Rev. 81:685–740.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ghosh D and Dawson MR: Microenvironment

influences cancer cell mechanics from tumor growth to metastasis.

Adv Exp Med Biol. 1092:69–90. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kumar S and Weaver VM: Mechanics,

malignancy, and metastasis: The force journey of a tumor cell.

Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28:113–127. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Frey B, Janko C, Ebel N, Meister S,

Schlücker E, Meyer-Pittroff R, Fietkau R, Herrmann M and Gaipl US:

Cells under pressure-treatment of eukaryotic cells with high

hydrostatic pressure, from physiologic aspects to pressure induced

cell death. Curr Med Chem. 15:2329–2336. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Patterson MF: Microbiology of

pressure-treated foods. J Appl Microbiol. 98:1400–1409. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhao LP, Hu JH, Hu D, Wang HJ, Huang CG,

Luo RH, Zhou ZH, Huang XY, Xie T and Lou JS: Hyperprogression, a

challenge of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors treatments: potential mechanisms

and coping strategies. Biomed Pharmacother. 150:1129492022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Moserova I, Truxova I, Garg AD, Tomala J,

Agostinis P, Cartron PF, Vosahlikova S, Kovar M, Spisek R and

Fucikova J: Caspase-2 and oxidative stress underlie the immunogenic

potential of high hydrostatic pressure-induced cancer cell death.

Oncoimmunology. 6:e12585052017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fucikova J, Moserova I, Truxova I,

Hermanova I, Vancurova I, Partlova S, Fialova A, Sojka L, Cartron

PF, Houska M, et al: High hydrostatic pressure induces immunogenic

cell death in human tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 135:1165–1177. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Rozková D, Tiserová H, Fucíková J,

Last'ovicka J, Podrazil M, Ulcová H, Budínský V, Prausová J, Linke

Z, Minárik I, et al: FOCUS on FOCIS: Combined chemo-immunotherapy

for the treatment of hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer.

Clin Immunol. 131:1–10. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang F and Jiang RM: Negative pressure

may become a new method for treatment of malignancies. J Air Force

Med Univ. 43:120–122. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

40

|

Yang X, Sun B, Zhu H and Jiang Z:

Suppression effects of negative pressure on the proliferation and

metastasis in human pancreatic cancer cells. J Cancer Res Ther.

11:195–198. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lallow EO, Jhumur NC, Ahmed I, Kudchodkar

SB, Roberts CC, Jeong M, Melnik JM, Park SH, Muthumani K, Shan JW,

et al: Novel suction-based in vivo cutaneous DNA transfection

platform. Sci Adv. 7:eabj06112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Szelényi Z and Komoly S: Thermoregulation:

From basic neuroscience to clinical neurology, part 2. Temperature

(Austin). 6:7–10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Vertree RA, Leeth A, Girouard M, Roach JD

and Zwischenberger JB: Whole-body hyperthermia: A review of theory,

design and application. Perfusion. 17:279–290. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chia BSH, Ho SZ, Tan HQ, Chua MLK and Tuan

JKL: A review of the current clinical evidence for loco-regional

moderate hyperthermia in the adjunct management of cancers. Cancers

(Basel). 15:3462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kok HP, Cressman ENK, Ceelen W, Brace CL,

Ivkov R, Grüll H, Ter Haar G, Wust P and Crezee J: Heating

technology for malignant tumors: A review. Int J Hyperthermia.

37:711–741. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hildebrandt B, Wust P, Ahlers O, Dieing A,

Sreenivasa G, Kerner T, Felix R and Riess H: The cellular and

molecular basis of hyperthermia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 43:33–56.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ito A, Shinkai M, Honda H, Wakabayashi T,

Yoshida J and Kobayashi T: Augmentation of MHC class I antigen

presentation via heat shock protein expression by hyperthermia.

Cancer Immunol Immunother. 50:515–522. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen C, Ren A, Yi Q, Cai J, Khan M, Lin Y,

Huang Z, Lin J, Zhang J, Liu W, et al: Therapeutic hyperthermia

regulates complement C3 activation and suppresses tumor development

through HSPA5/NFκB/CD55 pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin

Exp Immunol. 213:221–234. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Paulson JR, Luedtke RL, Suydam S, Obi D

and Xie L: ABT-263, an inhibitor of Bcl-2 family antiapoptotic

proteins, sensitizes prometaphase-arrested HeLa cells to apoptosis

induced by mild hyperthermia. Int J Biochem Res Rev. 31:23–34.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Dillon MT, Good JS and Harrington KJ:

Selective targeting of the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint to improve

the therapeutic index of radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol).

26:257–265. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hatamian M, Hashemi B, Mahdavi SR,

Soleimani M and Khalafi L: Effect of 13.56 MHz radiofrequency

hyperthermia on mitotic cell cycle arrest in MCF7 breast cancer

cell line and suggest a time interval for radiotherapy. J Cancer

Res Ther. 19:447–451. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hu S, Hui Z, Lirussi F, Garrido C, Ye XY

and Xie T: Small molecule DNA-PK inhibitors as potential cancer

therapy: A patent review (2010-present). Expert Opin Ther Pat.

31:435–452. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

van Oorschot B, Granata G, Di Franco S,

Ten Cate R, Rodermond HM, Todaro M, Medema JP and Franken NA:

Targeting DNA double strand break repair with hyperthermia and

DNA-PKcs inhibition to enhance the effect of radiation treatment.

Oncotarget. 7:65504–65513. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Goldstein M and Kastan MB: The DNA damage

response: Implications for tumor responses to radiation and

chemotherapy. Annu Rev Med. 66:129–143. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Liang X, Zhou H, Liu X, He Y, Tang Y, Zhu

G, Zheng M and Yang J: Effect of local hyperthermia on

lymphangiogenic factors VEGF-C and -D in a nude mouse xenograft

model of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 46:111–115.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Razavi R and Harrison LE: Thermal

sensitization using induced oxidative stress decreases tumor growth

in an in vivo model of hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion. Ann

Surg Oncol. 17:304–311. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Datta NR, Ordóñez SG, Gaipl US, Paulides

MM, Crezee H, Gellermann J, Marder D, Puric E and Bodis S: Local

hyperthermia combined with radiotherapy and-/or chemotherapy:

Recent advances and promises for the future. Cancer Treat Rev.

41:742–753. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Baust JG, Snyder KK, Santucci KL,

Robilotto AT, Van Buskirk RG and Baust JM: Cryoablation: Physical

and molecular basis with putative immunological consequences. Int J

Hyperthermia. 36 (Suppl 1):S10–S16. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Wen J, Duan Y, Zou Y, Nie Z, Feng H,

Lugnani F and Baust JG: Cryoablation induces necrosis and apoptosis

in lung adenocarcinoma in mice. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

6:635–640. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chen Z, Meng L, Zhang J and Zhang X:

Progress in the cryoablation and cryoimmunotherapy for tumor. Front

Immunol. 14:10940092023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Shao Q, O'Flanagan S, Lam T, Roy P, Pelaez

F, Burbach BJ, Azarin SM, Shimizu Y and Bischof JC: Engineering T

cell response to cancer antigens by choice of focal therapeutic

conditions. Int J Hyperthermia. 36:130–138. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wu Y, Cao F, Zhou D, Chen S, Qi H, Huang

T, Tan H, Shen L and Fan W: Cryoablation reshapes the immune

microenvironment in the distal tumor and enhances the anti-tumor

immunity. Front Immunol. 13:9304612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Seki T, Yang Y, Sun X, Lim S, Xie S, Guo

Z, Xiong W, Kuroda M, Sakaue H, Hosaka K, et al: Brown-fat-mediated

tumour suppression by cold-altered global metabolism. Nature.

608:421–428. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Guo RQ, Guo XX, Li YM, Bie ZX, Li B and Li

XG: Cryoablation, high-intensity focused ultrasound, irreversible

electroporation, and vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy for

prostate cancer: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin

Oncol. 26:461–484. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kurz B, Berneburg M, Bäumler W and Karrer

S: Phototherapy: Theory and practice. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges.

21:882–897. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Li X, Lovell JF, Yoon J and Chen X:

Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic

therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 17:657–674. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Yang X, Zhang H, Wu Z, Chen Q, Zheng W,

Shen Q, Wei Q, Shen JW and Guo Y: Tumor therapy utilizing

dual-responsive nanoparticles: A multifaceted approach integrating

calcium-overload and PTT/CDT/chemotherapy. J Control Release.

376:646–658. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Vankayala R and Hwang KC:

Near-infrared-light-activatable nanomaterial-mediated

phototheranostic nanomedicines: An emerging paradigm for cancer

treatment. Adv Mater. 30:e17063202018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ali MRK, Ibrahim IM, Ali HR, Selim SA and

El-Sayed MA: Treatment of natural mammary gland tumors in canines

and felines using gold nanorods-assisted plasmonic photothermal

therapy to induce tumor apoptosis. Int J Nanomedicine.

11:4849–4863. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Pérez-Hernández M, Del Pino P, Mitchell

SG, Moros M, Stepien G, Pelaz B, Parak WJ, Gálvez EM, Pardo J and

de la Fuente JM: Dissecting the molecular mechanism of apoptosis

during photothermal therapy using gold nanoprisms. ACS Nano.

9:52–61. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wang S, Li L, Ning X, Xue P and Liu Y:

pH-activated heat shock protein inhibition and radical generation

enhanced NIR luminescence imaging-guided photothermal tumour

ablation. Int J Pharm. 566:40–45. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Deng X, Guan W, Qing X, Yang W, Que Y, Tan

L, Liang H, Zhang Z, Wang B, Liu X, et al: Ultrafast

low-temperature photothermal therapy activates autophagy and

recovers immunity for efficient antitumor treatment. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 12:4265–4275. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhao P, Zheng M, Yue C, Luo Z, Gong P, Gao

G, Sheng Z, Zheng C and Cai L: Improving drug accumulation and

photothermal efficacy in tumor depending on size of ICG loaded

lipid-polymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 35:6037–6046. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Nam J, Son S, Ochyl LJ, Kuai R,

Schwendeman A and Moon JJ: Chemo-photothermal therapy combination

elicits anti-tumor immunity against advanced metastatic cancer. Nat

Commun. 9:10742018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Li T, Ashrafizadeh M, Shang Y, Nuri Ertas

Y and Orive G: Chitosan-functionalized bioplatforms and hydrogels

in breast cancer: Immunotherapy, phototherapy and clinical

perspectives. Drug Discov Today. 29:1038512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH,

Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, Hahn SM, Hamblin MR, Juzeniene A, Kessel

D, et al: Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA Cancer J

Clin. 61:250–281. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Castano AP, Mroz P and Hamblin MR:

Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer.

6:535–545. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Tian R, Sun W, Li M, Long S, Li M, Fan J,

Guo L and Peng X: Development of a novel anti-tumor theranostic

platform: A near-infrared molecular upconversion sensitizer for

deep-seated cancer photodynamic therapy. Chem Sci. 10:10106–10112.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Liu YQ, Meng PS, Zhang HC, Liu X, Wang MX,

Cao WW, Hu Z and Zhang ZG: Inhibitory effect of aloe emodin

mediated photodynamic therapy on human oral mucosa carcinoma in

vitro and in vivo. Biomed Pharmacother. 97:697–707. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

de Miguel GC, Abrantes AM, Laranjo M,

Grizotto AYK, Camporeze B, Pereira JA, Brites G, Serra A, Pineiro

M, Rocha-Gonsalves A, et al: A new therapeutic proposal for

inoperable osteosarcoma: Photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis

Photodyn Ther. 21:79–85. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Krupka M, Bartusik-Aebisher D, Strzelczyk

N, Latos M, Sieroń A, Cieślar G, Aebisher D, Czarnecka M,

Kawczyk-Krupka A and Latos W: The role of autofluorescence,

photodynamic diagnosis and Photodynamic therapy in malignant tumors

of the duodenum. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 32:1019812020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Dolmans DEGJ, Kadambi A, Hill JS, Waters

CA, Robinson BC, Walker JP, Fukumura D and Jain RK: Vascular

accumulation of a novel photosensitizer, MV6401, causes selective

thrombosis in tumor vessels after photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res.

62:2151–2156. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Ma Q, Zhang H, Liu Y, Hong

J, Ding Z, Liu M and Han J: Novel carrier-free nanoparticles

composed of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin and chlorin e6:

Self-assembly mechanism investigation and in vitro/in vivo

evaluation. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 188:1107222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liu C, Sun S, Feng Q, Wu G, Wu Y, Kong N,

Yu Z, Yao J, Zhang X, Chen W, et al: Arsenene nanodots with

selective killing effects and their low-dose combination with

ß-elemene for cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 33:e21020542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Zheng Y, Yin G, Le V, Zhang A, Chen S,

Liang X and Liu J: Photodynamic-therapy activates immune response

by disrupting immunity homeostasis of tumor cells, which generates

vaccine for cancer therapy. Int J Biol Sci. 12:120–132. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lee JY, Diaz RR, Cho KS, Lim MS, Chung JS,

Kim WT, Ham WS and Choi YD: Efficacy and safety of photodynamic

therapy for recurrent, high grade nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer

refractory or intolerant to bacille Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy.

J Urol. 190:1192–1199. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Correia JH, Rodrigues JA, Pimenta S, Dong

T and Yang Z: Photodynamic therapy review: Principles,

photosensitizers, applications, and future directions.

Pharmaceutics. 13:13322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Chen W, Liu C, Ji X, Joseph J, Tang Z,

Ouyang J, Xiao Y, Kong N, Joshi N, Farokhzad OC, et al:

Stanene-based nanosheets for β-elemene delivery and

ultrasound-mediated combination cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed

Engl. 60:7155–7164. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Li E, Sun Y, Lv G, Li Y, Zhang Z, Hu Z and

Cao W: Sinoporphyrin sodium based sonodynamic therapy induces

anti-tumor effects in hepatocellular carcinoma and activates

p53/caspase 3 axis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 113:104–114. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Yang W, Xu H, Liu Q, Liu C, Hu J, Liu P,

Fang T, Bai Y, Zhu J and Xie R: 5-Aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride

loaded microbubbles-mediated sonodynamic therapy in pancreatic

cancer cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 48:1178–1188. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Hong X, Huang S, Jiang H, Ma Q, Qiu J, Luo

Q, Cao C, Xu Y, Chen F, Chen Y, et al: Alcohol-related liver

disease (ALD): Current perspectives on pathogenesis, therapeutic

strategies, and animal models. Front Pharmacol. 15:14324802024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zhang R, Pan T, Xiang Y, Zhang M, Feng J,

Liu S, Duan T, Chen P, Zhai B, Chen X, et al: β-Elemene reverses

the resistance of p53-deficient colorectal cancer cells to

5-fluorouracil by inducing pro-death autophagy and cyclin

D3-dependent cycle arrest. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 8:3782020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zhang R, Zheng Y, Zhu Q, Gu X, Xiang B, Gu

X, Xie T and Sui X: β-Elemene reverses gefitinib resistance in

NSCLC cells by inhibiting lncRNA H19-mediated autophagy.