Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a highly

heterogeneous hematological malignancy that poses significant

treatment challenges. Despite considerable advancements in

induction and consolidation therapies for AML in recent years, the

risk of relapse after achieving complete remission (CR) remains

high (1). Specifically, among

patients aged <60 years, >50% experienced relapse, whereas

relapse rates reached 90% in those aged ≥60 years. This high

disease recurrence rate contributes to an aggregated 5-year overall

survival (OS) of 30.5% across all cases (2). This underscores the urgent need for

effective and safe post-remission treatment strategies to enhance

disease-free survival and ultimately OS survival. While

consolidation therapy has been established to improve survival

outcomes in low-risk patients with AML, maintenance therapy, a

standard treatment component for certain hematological

malignancies, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute

promyelocytic leukemia (3,4), remains a contentious issue in AML. For

patients with AML harboring high-risk factors for recurrence and

who have undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation, maintenance therapy is deemed necessary to

mitigate the risk of recurrence (5,6).

However, for those with intermediate-to-low-risk disease,

maintenance therapy is not yet part of the standard treatment

regimen due to insufficient evidence of its benefits. Thus, the

exploration of maintenance therapy for patients with intermediate

and low-risk AML is of importance.

The combination of azacitidine (AZA) and venetoclax

(VEN) has demonstrated synergistic effects, enhancing the

anti-leukemic efficacy while potentially reducing drug dosages and

associated toxicities (7,8). This VEN and hypomethylating agent

regimen has emerged as the standard treatment for elderly or unfit

patients with AML who are not suitable for intensive chemotherapy,

where unfitness is defined as meeting ≥1 of the following: Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≥2; Hematopoietic

Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index ≥3; organ dysfunction; or

active infection requiring intravenous antimicrobial therapy

(9–11). Although studies have explored the

use of AZA or VEN individually for maintenance therapy in AML

(12), there is a paucity of

research on the application of the combined VEN plus AZA (VEN-AZA)

regimen for maintenance therapy in patients with

low-to-intermediate-risk AML.

In the present study, a retrospective analysis of 43

patients newly diagnosed with intermediate-to-low-risk AML who

underwent maintenance therapy at Beijing Luhe Hospital Affiliated

to Capital Medical University (Beijing, China) was conducted to

evaluate the efficacy and safety of the combination regimen of

VEN-AZA in maintenance therapy for patients with this disease.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and data

collection

A retrospective analysis of patients with primary

intermediate-to-low-risk AML admitted to Beijing Luhe Hospital

Affiliated to Capital Medical University between March 2018 and

June 2024 was conducted. Prognostic risk stratification was

conducted according to the 2022 European Leukemia Net AML criteria

(13). The inclusion criteria were

as follows: i) Patients who remained in CR following induction and

consolidation therapy, with blasts of <5% and no evidence of

extramedullary tumor infiltration and received either VEN-AZA

treatment regimen or no treatment; ii) patients who were not

eligible for or unwilling to undergo allogeneic or autologous

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; iii) patients who had not

received other targeted drugs; and iv) patients with complete

clinical data. The study variables including the patient's age,

sex, prognosis stratification, white blood cell (WBC) count,

platelet count, lactate dehydrogenase levels, bone marrow blast

percentage, chromosomal analysis, fusion genes, gene mutations and

minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring prior to maintenance

therapy were retrospectively extracted from electronic medical

records.

Diagnostic data collection Bone marrow

morphological examination was performed using Wright's staining,

with 200 nucleated cells counted under an oil-immersion lens. All

molecular analyses, including reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR (RT-qPCR) for AML1-ETO, CBFβ-MYH11 and HOX11 expression

quantification, as well as next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based

mutation profiling of 248 genes, were performed by Hightrust

Diagnostics Medical Laboratory (Beijing, China). The RT-qPCR primer

sequence information for various genes is shown in Table I. For NGS, libraries were

constructed using the Hemaseq™ Myeloid 248 Gene Mutation Detection

Kit (Healthy Biotechnology Co., Ltd; cat. no. S0918-S), a

hybridization capture-based panel targeting exons and flanking ±20

bp intronic regions of 248 genes, including core driver genes [such

as fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), nucleophosmin 1

(NPM1) and CCAAT enhancer binding protein α (CEBPA)], epigenetic

regulators [(such as DNA methyltransferase 3α (DNMT3A), tet

methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2), isocitrate dehydrogenase

[NADP(+)] 1/2 (IDH1/2)], signaling pathway genes (such as Janus

kinase 2 and calreticulin) and spliceosome complex genes (such as

splicing factor 3b subunit 1 and serine and arginine rich splicing

factor 2).

| Table I.PCR primer sequence information. |

Table I.

PCR primer sequence information.

| Gene name | Forward primer

sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse primer

sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|

| AML1-ETO |

CACCTACCACAGAGCCATCAAA |

ATCCACAGGTGAGTCTGGCATT |

| CBFβ-MYH11 |

CATTAGCACAACAGGCCTTTGA |

AGGGCCCGCTTGGACTT |

| HOX11 |

TGGATGGAGAGTAACCGCAGAT |

GGGCGTCCGGTTCTGATA |

For bone marrow MRD detection, a Canto II flow

cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company) with Diva software was

used to acquire and analyze the data. Antibody reagents from

Becton, Dickinson and Company and Beckman Coulter, Inc. were used

to label CD34, CD117, CD38, HLA-DR, CD33, CD13, CD15, CD14, CD4,

CD7, CD19 and CD56. After collecting 500,000 CD45+ cells, abnormal

cell populations were identified by combining leukemia-associated

immunophenotype and ‘different from normal’ approaches. The

threshold was set at 0.1% as per the European LeukemiaNet

recommendations to distinguish negative and positive results

(14). Additionally, RT-qPCR

targeting AML1-ETO and CBFβ-MYH11 fusion-gene transcripts was used

for MRD detection.

Maintenance therapy and efficacy

endpoint

Patients in the maintenance therapy group received

VEN-AZA maintenance therapy 1 month after consolidation therapy.

The specific VEN-AZA dosing regimen was as follows: Subcutaneous

injection of 75 mg/m2 AZA for 7 consecutive days and the

dose of VEN was reduced from the standard 400 mg daily to 200 mg on

days 1–21. If grade 4 myelosuppression (based on the Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0) occurred

during treatment (15), the VEN

treatment was paused and supportive treatments such as leukocyte

elevation, anti-infection measures or component blood transfusions

were provided. One treatment cycle lasted 2–3 months. During the

maintenance treatment period, an assessment was conducted per

treatment cycle. The methods for detecting MRD included qPCR for

detecting fusion genes and flow cytometry to identify

leukemia-associated abnormal phenotypes in the bone marrow cells of

patients. The primary efficacy endpoint was progression-free

survival (PFS), defined as the time from the onset of the disease

to recurrence, death or end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the median and

range (minimum to maximum). Intergroup comparisons were conducted

using the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test. For categorical variables,

proportional differences were analyzed via Fisher's exact test when

any expected cell count was <10; otherwise, the χ2

test was applied (Table II). The

impact of maintenance therapy on PFS was evaluated using

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests. Differences in PFS

were assessed using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional

hazards regression analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was

performed using Empower(R) (www.empowerstats.com; X&Y solutions, Inc.) and R

version 3.6.1 (http://www.R-project.org).

| Table II.Clinical and biological

characteristics of patients with AML at diagnosis. |

Table II.

Clinical and biological

characteristics of patients with AML at diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Off maintenance

therapy, n=21 | On maintenance

therapy, n=22 | P-value |

|---|

| Median age at

diagnosis, years (range) | 59.00

(24.00–81.00) | 49.00

(21.00–75.00) | 0.165 |

| Median white blood

cells, ×109/l (range) | 8.59

(0.84–362.06) | 7.46

(0.88–76.20) | 0.078 |

| Median hemoglobin,

g/l (range) | 85.00

(51.00–150.00) | 86.50

(34.00–127.00) | 0.560 |

| Median platelets,

×109/l (range) | 43.00

(8.00–265.00) | 51.50

(2.00–333.00) | 0.806 |

| Median bone marrow

blast count, % (range) | 62.00

(1.00–91.00) | 44.75

(13.00–78.00) | 0.521 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

| 0.432 |

|

Female | 8 (38.10) | 11 (50.00) |

|

| Male | 13 (61.90) | 11 (50.00) |

|

| Gene fusion, n

(%) |

|

| 0.956 |

|

Negative | 9 (42.86) | 11 (50.00) |

|

|

AML1-ETO | 7 (33.33) | 7 (31.82) |

|

|

HOX11 | 4 (19.05) | 3 (13.64) |

|

|

CBFβ-MYH11 | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.55) |

|

| NPM1 status n

(%) |

|

| 0.280 |

| Wild

type | 13 (61.90) | 10 (45.45) |

|

|

Mutant | 8 (38.10) | 12 (54.55) |

|

| CEBPA status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.021 |

| Wild

type | 14 (66.67) | 21 (95.45) |

|

|

Mutant | 7 (33.33) | 1 (4.55) |

|

| FLT3 status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.252 |

| Wild

type | 15 (71.43) | 12 (54.55) |

|

|

Mutant | 6 (28.57) | 10 (45.45) |

|

| DNMT3A status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.069 |

| Wild

type | 14 (66.67) | 20 (90.91) |

|

|

Mutant | 7 (33.33) | 2 (9.09) |

|

| KIT status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.475 |

| Wild

type | 16 (76.19) | 19 (86.36) |

|

|

Mutant | 5 (23.81) | 3 (13.64) |

|

| ASXL1 status, n

(%) |

|

| >0.999 |

| Wild

type | 20 (95.24) | 20 (90.91) |

|

|

Mutant | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.09) |

|

| ASXL2 status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.607 |

| Wild

type | 19 (90.48) | 21 (95.45) |

|

|

Mutant | 2 (9.52) | 1 (4.55) |

|

| NRAS status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.664 |

| Wild

type | 19 (90.48) | 18 (81.82) |

|

|

Mutant | 2 (9.52) | 4 (18.18) |

|

| IDH2 status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.664 |

| Wild

type | 19 (90.48) | 18 (81.82) |

|

|

Mutant | 2 (9.52) | 4 (18.18) |

|

| IDH1 status, n

(%) |

|

| >0.999 |

| Wild

type | 20 (95.24) | 20 (90.91) |

|

|

Mutant | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.09) |

|

| TET2 status, n

(%) |

|

| 0.412 |

| Wild

type | 17 (80.95) | 20 (90.91) |

|

|

Mutant | 4 (19.05) | 2 (9.09) |

|

| Karyotype, n

(%) |

|

| >0.999 |

|

Normal | 12 (57.14) | 12 (54.55) |

|

|

Favorable | 2 (9.52) | 3 (13.64) |

|

|

Other | 7 (33.33) | 7 (31.82) |

|

| Prognostic

stratification, n (%) |

|

| 0.048 |

|

Favorable group | 13 (61.90) | 7 (31.82) |

|

|

Intermediate group | 8 (38.10) | 15 (68.18) |

|

| Minimal residual

disease, n (%) |

|

| 0.607 |

|

Negative | 14 (66.67) | 13 (59.09) |

|

|

Positive | 7 (33.33) | 9 (40.91) |

|

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

The present study retrospectively analyzed 43 cases

of newly diagnosed patients with intermediate-to-low-risk AML who

remained in CR following the completion of induction and

consolidation therapy Among them, there were 10 patients in the

maintenance therapy group who received intensive treatment during

the induction phase and 11 patients who received low-intensity

treatment [based on hypomethylating agents (HMAs) or low-dose

cytarabine]. Thus, there were 22 patients who received maintenance

therapy. The median number of maintenance treatment cycles was 8

(range, 2–18). Among these patients, 59.09% (n=13) achieved

MRD-negative (MRDneg) status following induction and consolidation

therapy. There were 21 patients who did not receive maintenance

therapy, with 66.67% (n=14) achieving MRDneg status following the

induction and consolidation therapy. There was no significant

difference in the MRDneg status between the off-maintenance therapy

group and the maintenance therapy group at enrollment. The gene

mutations with the highest frequency in the 43 patients were NPM1,

CEBPA, FLT3, DNMT3A, KIT, ASXL transcriptional regulator 1 (ASXL1),

ASXL2, NRAS, IDH1, IDH2 and TET2. The comparison of basic clinical

characteristics between the two groups is shown in Table II. The proportion of patients with

CEBPA mutations was higher in the off-maintenance therapy group

(33.33% vs. 4.55%; P=0.021), and the proportion of patients in the

favorable group was also higher in the off-maintenance therapy

group (61.90 vs. 31.82%; P=0.048). During the study period, the

most common grade 3–4 hematological adverse events in the

maintenance treatment group were neutropenia (n=2) and

thrombocytopenia (n=4), and the most common non-hematological

adverse event was respiratory infection (Table III). Grade 3–4 adverse events were

experienced by 9 patients during cycles 1–2 of treatment. No deaths

occurred during the maintenance treatment period.

| Table III.Adverse events of maintenance

treatment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. |

Table III.

Adverse events of maintenance

treatment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

| Adverse event | Grade 3–4, n

(%) |

|---|

| Neutropenia | 2 (9) |

| Anemia | 0 (0) |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 4 (19) |

| Digestive tract

symptom | 1 (4) |

| Fatigue | 0 (0) |

| Respiratory

infection | 2 (9) |

| Pain | 0 (0) |

| Heart disease | 1 (4) |

| Liver damage | 0 (0) |

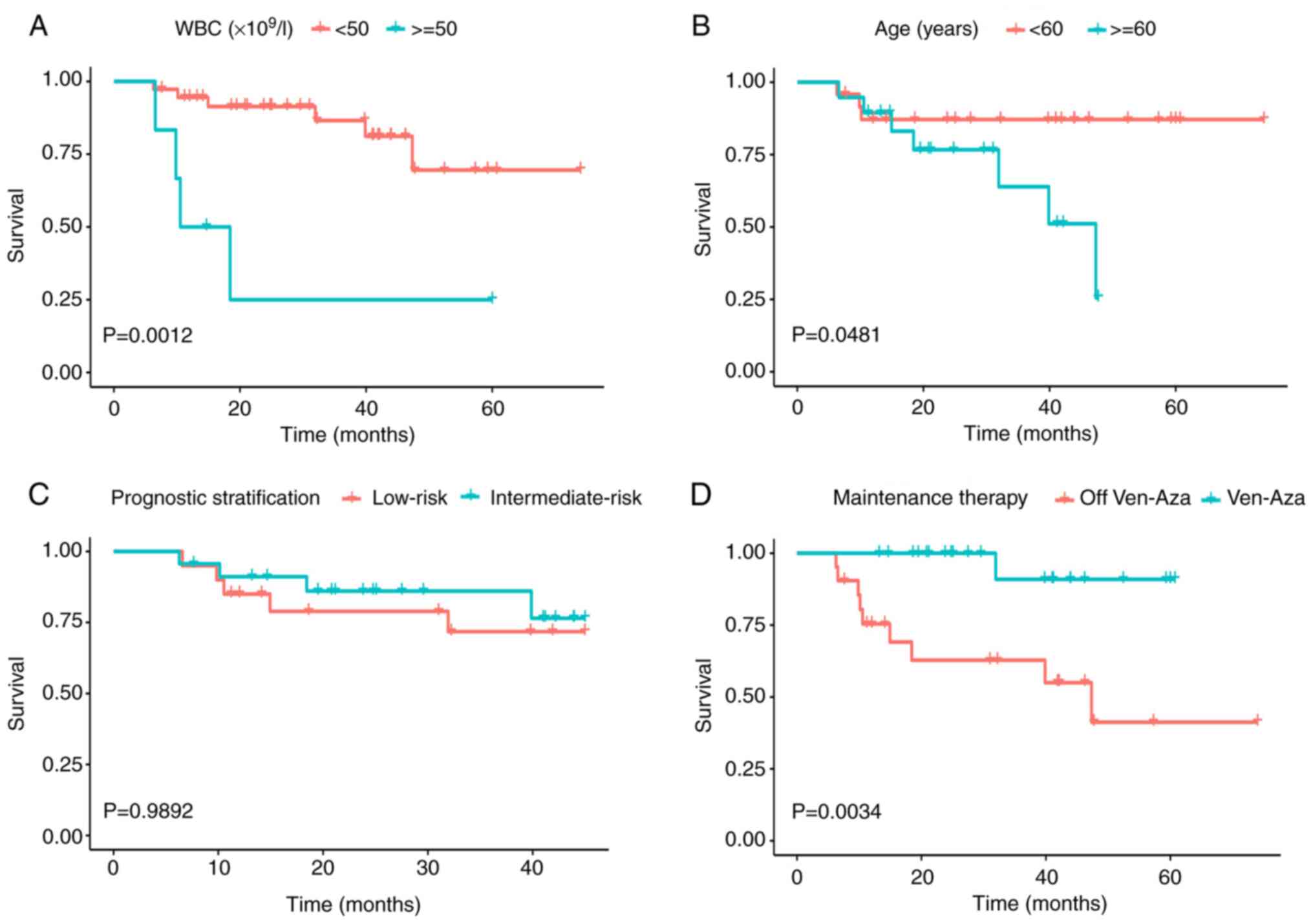

Prognostic value

Clinical and pathological parameters predictive of

PFS were further investigated through univariate and multivariate

Cox regression models. In the univariate analysis, maintenance

therapy selection, WBC and age were significantly associated with

PFS (Table IV). Patients with AML

who did not accept maintenance therapy showed a significantly

unfavorable PFS. With a median follow-up of 29.6 months (7–74), the

median PFS was not reached in patients with AML receiving

maintenance therapy, while the median PFS time for those not

receiving maintenance therapy was 47.3 months (P=0.0034; Fig. 1D). The PFS time decreased in

patients with WBC ≥50×109/l and those aged ≥60 (P=0.0012

and P=0.0481, respectively; Fig. 1A and

B). No difference in PFS was observed between the

intermediate-risk and low-risk patients (P=0.9892; Fig. 1C).

| Table IV.Univariate analysis of

progression-free survival. |

Table IV.

Univariate analysis of

progression-free survival.

|

| Progression-free

survival |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

Male | 1.0 |

|

|

Female | 1.6 (0.4–6.2) | 0.495 |

| Age | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.027 |

| White blood cells

count | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin

count | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.487 |

| Platelets

count | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.575 |

| Prognostic

stratification |

| 0.989 |

|

Favorable group | 1.0 |

|

|

Intermediate group | 1.0 (0.3–3.5) |

|

| Maintenance

therapy |

| 0.021 |

| Off

VEN-AZA | 1.0 |

|

|

VEN-AZA | 0.1 (0.0–0.7) |

|

| Minimal residual

disease |

| 0.107 |

|

Negative | 1.0 |

|

|

Positive | 2.8 (0.8–10.1) |

|

Study end points

The multivariate Cox regression model was employed

to examine the association between VEN-AZA maintenance therapy and

PFS, with adjustments made for potential confounding factors

(Table V). In both the unadjusted

and adjusted models, it was observed that patients with AML who

underwent VEN-AZA maintenance treatment exhibited a decreased risk

of the primary endpoint event, compared with those not receiving

maintenance treatment. In the unadjusted model, the hazard ratio

(HR) was determined to be 0.09, with a 95% confidence interval (CI)

of 0.01–0.69. In the Adjusted I model, the adjustment factors

included the age of the patients at the time of diagnosis, which

was categorized as either ≥60 years old or <60 years old, and

the WBC count was specified as ≥50×109/l or

<50×109/l. The corresponding HR was found to be 0.1,

with a 95% CI of 0.01–0.85. In the Adjusted II model, the

adjustment factors comprised the age of the patients at diagnosis

(≥60 years old or <60 years old), the WBC count

(≥50×109/l or <50×109/l), prognostic

stratification and mutations in the DNMT3A, NRAS, IDH2, IDH1, TET2,

ASXL1 and ASXL2 genes, as well as MRD prior to maintenance

treatment. The HR was calculated to be 0.06, with a 95% CI of

0.00–0.77.

| Table V.Association between VEN-AZA

maintenance therapy and the endpoint of acute myeloid leukemia

recurrence in multivariate Cox proportional-hazards analysis. |

Table V.

Association between VEN-AZA

maintenance therapy and the endpoint of acute myeloid leukemia

recurrence in multivariate Cox proportional-hazards analysis.

|

| Non-adjusted | Adjust

Ia | Adjust

IIb |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Therapy | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Off VEN-AZA | 1.0 | 0.0205 | 1.0 | 0.0354 | 1.0 | 0.0309 |

| VEN-AZA | 0.09

(0.01–0.69) |

| 0.10

(0.01–0.85) |

| 0.06

(0.00–0.77) |

|

Discussion

Maintenance therapy for AML plays a pivotal role in

reducing the recurrence risk and enhancing patient survival rates.

The VIALE-A study (16)

demonstrated that combination treatment with VEN-AZA can

significantly improve treatment outcomes. The VEN-AZA regimen is

typically designed as a long-term treatment, which persists until

disease progression or the emergence of unacceptable toxicity

(17). In the present study,

patients with intermediate-to-low-risk AML attained CR following

consolidation therapy. Among those continuing VEN-AZA maintenance

therapy, only 1 case experienced disease progression, with PFS not

reached, showing a significantly longer PFS compared with the

non-maintenance group (median PFS of 47.3 months). Even after

adjusting for age, WBC count, prognostic stratification and

prognosis-related gene mutations, the relapse risk of

maintenance-treated patients remained significantly lower. Pratz

et al (18) demonstrated the

importance of MRD in a cohort of patients with a longer follow-up

(median >20 months). Those who achieved CR without measurable

residual disease also showed a longer duration of remission, OS and

event-free survival compared with patients with MRD positivity. The

VIALE-A study (16) demonstrated

that patients responsive to VEN-AZA who achieved CR with MRD

negativity had a median OS time of ~3 years. The study by Chua

et al (19) confirmed that

patients receiving VEN-based treatment for 12 months and achieving

MRD negativity at the end of treatment had the potential for

durable treatment-free remission (TFR). Deep remission is a key

determinant of long-term survival in patients with AML. During

continuous VEN-AZA treatment in the present study, the MRD of 8

patients turned negative, achieving molecular remission, with no

relapses. By contrast, 7 patients had persistent positive MRD

following consolidation and 6 exhibited relapse. This is consistent

with previously reported results that indicated that late-stage

MRDneg responses were associated with an improved prognosis

(20). This suggested that

intermediate- or low-risk patients may benefit from VEN-AZA

maintenance, likely due to deep remission induced by continuous

treatment, effectively preventing relapse.

The maintenance treatment regimen for AML should

effectively prevent recurrence while avoiding severe

chemotherapy-related adverse reactions. A previous study reported

that the incidence of any-grade infections was 84% in the

combination therapy group and 67% in the single-agent AZA group.

The incidence of severe adverse events was 83% in the combination

therapy group, higher than the 73% in the single-agent AZA group

(21). Of note, in the present

study, no deaths or severe adverse events occurred during the

maintenance treatment of patients. The most common grade 3–4

adverse events were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and respiratory

tract infections. Most adverse reactions occurred in the first two

cycles of maintenance treatment, and then the frequency gradually

decreased, which may have been associated with the dose reduction

of VEN or the adjustment of the administration time. As

demonstrated in the retrospective analysis by Xin et al

(22), in patients who responded to

the combination therapy of HMAs and VEN, the incidence of

infectious complications was relatively high, and the

infection-related mortality was also at a high level. The

infection-related mortality has an adverse impact on the OS of this

vulnerable patient population with AML. Elderly patients with AML

or those unfit for intensive chemotherapy are more likely to be

affected by treatment-related toxicities during long-term treatment

(23). Therefore, for patients with

intermediate- or low-risk AML who achieve deep (MRD ≤0.01%) and

sustained CR, attempting to discontinue treatment and obtaining the

benefits of treatment-free survival (TFS) could be a feasible

strategy.

However, whether discontinuing treatment is the best

strategy for achieving an improvement in quality of life and TFR

remains controversial (24). In the

present study, the median number of maintenance treatment cycles

was 8 (range, 2–18), yet we were unable to determine the minimum

number of VEN-AZA treatment cycles associated with a longer TFR. As

reported in the study by Garciaz et al (25), patients who had received >10

previous cycles of treatment had the longest TFS, and a minimum of

5 cycles were associated with an acceptable TFR. Therefore, further

exploration to determine the optimal number of cycles and dosage

for maintenance therapy is needed.

Although the present study demonstrated the

advantages of VEN-AZA maintenance therapy in reducing the

recurrence risk and prolonging survival in patients with

intermediate- or low-risk AML, it should be noted that the study

has limitations. The small sample size increases the likelihood of

failing to detect true treatment effects. As a retrospective study,

a number of confounding factors, including prior consolidation

chemotherapy regimens and prophylactic antibiotic choices, were not

included, which may have inflated the observed treatment benefits.

Additionally, the limited follow-up duration might have led to an

underestimation of late toxicities. Future research should focus on

conducting large-scale, long-term and strictly controlled clinical

trials to accurately determine the minimum number of VEN-AZA

maintenance treatment cycles required to achieve durable TFR

without compromising treatment efficacy. Additionally, given that

existing studies have shown that molecular changes, such as NPM1

and IDH mutations, are associated with a higher benefit from

VEN-AZA treatment (26),

identifying predictive biomarkers to accurately screen out patients

who are most likely to benefit from VEN-AZA maintenance therapy

will lay the foundation for developing truly individualized

treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by Youth Support Project of Luhe

Hospital (grant no. LHYH2024-LC07).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DZ and XD conceptualized the study, designed the

methodology and interpreted data. DZ and HZ conducted the

statistical analyses and validated the analytical models. XD

drafted the manuscript and coordinated revisions. YZ, XC and JQ

completed the acquisition and preliminary interpretation of

clinical data. TC participated in the study design. HZ adjudicated

clinical endpoints, resolved discrepancies in adverse event

attribution and critically revised the manuscript for scientific

accuracy. HZ and XC confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Affiliated Beijing Luhe Hospital of Capital Medical University

(Beijing, China; approval no. 2024-KY-108). Given the retrospective

nature of the study and the use of de-identified patient data, the

requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional

Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the

ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later

amendments.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Yuan XL, Lai XY, Wu YB, Yang L, Shi J, Liu

L, Zhao Y, Yu J, Huang H and Luo Y: Risk factors and prediction

model of early relapse in acute myeloid leukemia after allogeneic

hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 140:12915. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

DiNardo CD, Erba HP, Freeman SD and Wei

AH: Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 401:2073–2086. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Toksvang LN, Lee SHR, Yang JJ and

Schmiegelow K: Maintenance therapy for acute lymphoblastic

leukemia: Basic science and clinical translations. Leukemia.

36:1749–1758. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sanz MA, Fenaux P, Tallman MS, Estey EH,

Löwenberg B, Naoe T, Lengfelder E, Döhner H, Burnett AK, Chen SJ,

et al: Management of acute promyelocytic leukemia: Updated

recommendations from an expert panel of the European LeukemiaNet.

Blood. 133:1630–1643. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kinsella FAM, Maroto MAL, Loke J and

Craddock C: Strategies to reduce relapse risk in patients

undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid

leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 204:2173–2183. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Molica M, Breccia M, Foa R, Jabbour E and

Kadia TM: Maintenance therapy in AML: The past, the present and the

future. Am J Hematol. 94:1254–1265. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tsao T, Shi Y, Kornblau S, Lu H, Konoplev

S, Antony A, Ruvolo V, Qiu YH, Zhang N, Coombes KR, et al:

Concomitant inhibition of DNA methyltransferase and BCL-2 protein

function synergistically induce mitochondrial apoptosis in acute

myelogenous leukemia cells. Ann Hematol. 91:1861–1870. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Garciaz S, Hospital MA, Alary AS, Saillard

C, Hicheri Y, Mohty B, Rey J, D'Incan E, Charbonnier A, Villetard

F, et al: Azacitidine plus venetoclax for the treatment of relapsed

and newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia patients. Cancers.

14:20252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

DiNardo CD, Pratz K, Pullarkat V, Jonas

BA, Arellano M, Becker PS, Frankfurt O, Konopleva M, Wei AH,

Kantarjian HM, et al: Venetoclax combined with decitabine or

azacitidine in treatment-naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid

leukemia. Blood. 133:7–17. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jonas BA and Pollyea DA: How we use

venetoclax with hypomethylating agents for the treatment of newly

diagnosed patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia.

33:2795–2804. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Klepin HD: Definition of unfit for

standard acute myeloid leukemia therapy. Curr Hematol Malig Rep.

11:537–544. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Senapati J, Kadia TM and Ravandi F:

Maintenance therapy in acute myeloid leukemia: Advances and

controversies. Haematologica. 108:2289–2304. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock

C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, Ebert BL, Fenaux P, Godley LA, Hasserjian

RP, et al: Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022

recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the

ELN. Blood. 140:1345–1377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Schuurhuis GJ, Heuser M, Freeman S, Béné

MC, Buccisano F, Cloos J, Grimwade D, Haferlach T, Hills RK,

Hourigan CS, et al: Minimal/measurable residual disease in AML: A

consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party.

Blood. 131:1275–1291. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Freites-Martinez A, Santana N,

Arias-Santiago S and Viera A: Using the common terminology criteria

for adverse events (CTCAE-Version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of

adverse events of anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl

Ed). 112:90–92. 2021.(In English, Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman

MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, Konopleva M, Döhner H, Letai A, Fenaux P, et

al: Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute

myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 383:617–629. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wei AH, Montesinos P, Ivanov V, DiNardo

CD, Novak J, Laribi K, Kim I, Stevens DA, Fiedler W, Pagoni M, et

al: Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for

intensive chemotherapy: A phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled

trial. Blood. 135:2137–2145. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pratz KW, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Recher C,

Schuh AC, Thirman MJ, Garcia JS, DiNardo CD, Vorobyev V,

Fracchiolla NS, et al: Measurable residual disease response and

prognosis in Treatment-Naïve acute myeloid leukemia with venetoclax

and azacitidine. J Clin Oncol. 40:855–865. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chua CC, Hammond D, Kent A, Tiong IS,

Konopleva MY, Pollyea DA, DiNardo CD and Wei AH: Treatment-free

remission after ceasing venetoclax-based therapy in patients with

acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 6:3879–3883. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bernardi M, Ferrara F, Carrabba MG,

Mastaglio S, Lorentino F, Vago L and Ciceri F: MRD in

Venetoclax-based treatment for AML: Does it really matter? Front

Oncol. 12:8908712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Alsouqi A, Geramita E and Im A: Treatment

of acute myeloid leukemia in older adults. Cancers (Basel).

5:54092023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Xin F, Yu YH, Shen XL and Zhang GX: The

efficacy of the combination of venetoclax and hypomethylating

agents versus HAG agents in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: A

retrospective study. Hematology. 29:23503192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rosko AE, Cordoba R, Abel G, Artz A, Loh

KP and Klepin HD: Advances in management for older adults with

hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 39:2102–2114. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Patel KK, Zeidan AM, Shallis RM, Prebet T,

Podoltsev N and Huntington SF: Cost-effectiveness of azacitidine

and venetoclax in unfit patients with previously untreated acute

myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 5:994–1002. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Garciaz S, Dumas PY, Bertoli S, Sallman

DA, Decroocq J, Belhabri A, Orvain C, Aspas Requena G, Simand C,

Laribi K, et al: Outcomes of acute myeloid leukemia patients who

responded to venetoclax and azacitidine and stopped treatment. Am J

Hematol. 99:1870–1876. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pollyea DA, DiNardo CD, Arellano ML,

Pigneux A, Fiedler W, Konopleva M, Rizzieri DA, Smith BD, Shinagawa

A, Lemoli RM, et al: Impact of venetoclax and azacitidine in

Treatment-Naïve patients with acute myeloid leukemia and IDH1/2

mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 28:2753–2761. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|