Introduction

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC) is a

highly aggressive malignancy. Although it most commonly arises in

the lungs, its occurrence in the gynaecological tract is rare

(1). When SCNEC does affect

gynaecological organs, the uterine cervix is the most frequently

involved site (1). Cervical SCNEC

accounts for <1% of all gynaecological malignancies and <5%

of all cervical cancers (2,3). Compared to cervical squamous cell

carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma, cervical SCNEC has a

significantly worse prognosis (1–4).

Therefore, early detection and multimodal therapy are crucial for

improving patient outcomes.

Cytological examination is one of the gold standards

for detecting cervical lesions because it is convenient, minimally

invasive, and cost-effective (5).

Thus, cytological diagnosis plays a crucial role in the early

detection of cervical SCNEC. However, due to its rarity, diagnosing

SCNEC cytologically can be challenging. In one study, only one out

of 13 patients was suspected of having cervical SCNEC based on

cytological findings (6). In

another cytological series, none of the patients were accurately

diagnosed with cervical SCNEC (7).

Instead, patients were often misdiagnosed with squamous lesions,

which are far more common (6,7). The

cytological features of cervical SCNEC are similar to those of

other organs, such as the lungs. These features include loose

cohesive clusters and/or single small, round neoplastic cells with

a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, oval-to-round nuclei with

finely granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli, nuclear

moulding in a necrotic background (6–10).

Moreover, cervical SCNEC may coexist with other histological types

of non-neuroendocrine neoplasms, including squamous intraepithelial

lesions (SIL), SCC, and adenocarcinoma (11–15).

The presence of these additional components may lead to a

misdiagnosis of SCNEC components in cytological specimens, as SIL,

SCC, or adenocarcinoma components can overshadow the SCNEC features

(16–19).

This study retrospectively analysed the cytological

features of cervical SCNEC, including combined SCNEC, and discussed

the clinicocytological features of this rare tumour, with a focus

on identifying coexisting carcinoma components.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Patients diagnosed with cervical SCNEC based on

pathological examination of biopsy and/or surgically resected

specimens at Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital

(Osaka, Japan) between January 2016 and December 2024 were included

in this study.

This retrospective, single-institution study was

conducted in accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki

guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University

Hospital (approval no. 2023-073). All data were anonymised.

Informed consent was obtained from the patients using an opt-out

methodology, as this retrospective study involved the use of

medical records and archived samples with no risk to participants.

This study did not include children. Information regarding study

inclusion criteria and opt-out options was provided on the

institutional website (https://www.ompu.ac.jp/u-deps/path/img/file19.pdf).

Cytological analysis

Cervical smear specimens were conventionally stained

with Papanicolaou stain. No liquid-based cytology was applied in

the present study. Cytological characteristics, including

background features (presence of necrotic material or inflammation)

and nuclear and cytoplasmic features of neoplastic cells, were

evaluated. The cytological features were re-evaluated by at least

two researchers in a blind manner. The cytological diagnosis was

performed according to the criteria of the Bethesda System for

Reporting Cervical Cytology (5). No

statistical analysis was performed in the present study.

Histopathological analysis

Surgically resected or biopsied uterine specimens

were fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin, dehydrated, embedded

in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

The histopathological features of all specimens were independently

assessed by at least two researchers. Histopathological features,

such as nuclear and cytoplasmic features, were evaluated and

compared with the cytological features observed in cervical smear

specimens.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using an

autostainer (Discovery Ultra System; Roche Diagnostics,

Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions;

4-micrometre sections were incubated with the following antibodies:

rabbit monoclonal antibody against CD56 (MRQ-42, pre-diluted

Roche), mouse monoclonal antibody against chromogranin A (LK2H10,

pre-diluted, Roche), mouse monoclonal antibody against p16 (E6H4,

pre-diluted, Roche), and rabbit monoclonal antibody against

synaptophysin (MRQ-40, pre-diluted, Roche). Secondary antibodies

were prediluted and incubated at room temperature using the

Optiview DAB Universal Kit (cat. no. 518-11427; Roche).

Results

Patient characteristics

Table I summarises

the clinicocytological features of the study cohort, which included

six female patients (median age, 55 years; range, 39–70 years).

Three patients had pure SCNEC, while two had combined SCNEC (in

both cases, the other carcinoma component was adenocarcinoma). The

remaining patient had carcinosarcoma, in which the carcinoma

component was SCNEC, and the sarcomatous component was homologous

sarcoma. Patient 6 (carcinosarcoma) received neoadjuvant

chemotherapy, followed by radical hysterectomy. Additionally, for

Patient 3 (pure SCNEC), only biopsy specimens were available. Human

papillomavirus (HPV) testing was not performed on any of the

patients.

| Table I.Clinicocytological features of small

neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. |

Table I.

Clinicocytological features of small

neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix.

|

|

|

|

|

| Cytological

features |

|---|

|

|

| Histological

features |

|

|---|

| Patient no. | Age, years |

| Initial

diagnosis | Background | Clusters | Nuclear moulding | Other components |

|---|

| Histology | Other component

(%) | Stage |

|---|

| 1 | 59 | Combined SCNEC | Adenocarcinoma in

situ (10%) | pT1b1 | SCNEC | Inflammatory | Small and

large | + | Adenocarcinoma |

| 2 | 41 | Pure SCNEC | - | pT1b1 | SCNEC | Inflammatory | Small | + | - |

| 3 | 70 | Pure SCNEC | - | NA | SCNEC | Inflammatory | Small and

large | + | - |

| 4 | 39 | Pure SCNEC | - | pT1b1 | SCNEC | Necrotic | Small and

large | + | - |

| 5 | 52 | Combined SCNEC | Adenocarcinoma

(30%) | pT1b2 | SCC | Necrotic | Small and

large | + | - |

| 6 | 58 | Carcinosarcoma | SCNEC and

homologous sarcoma components (10%) | ypT1b1 | SCNEC | Necrotic | Small and

large | + | Sarcoma |

Cytological features

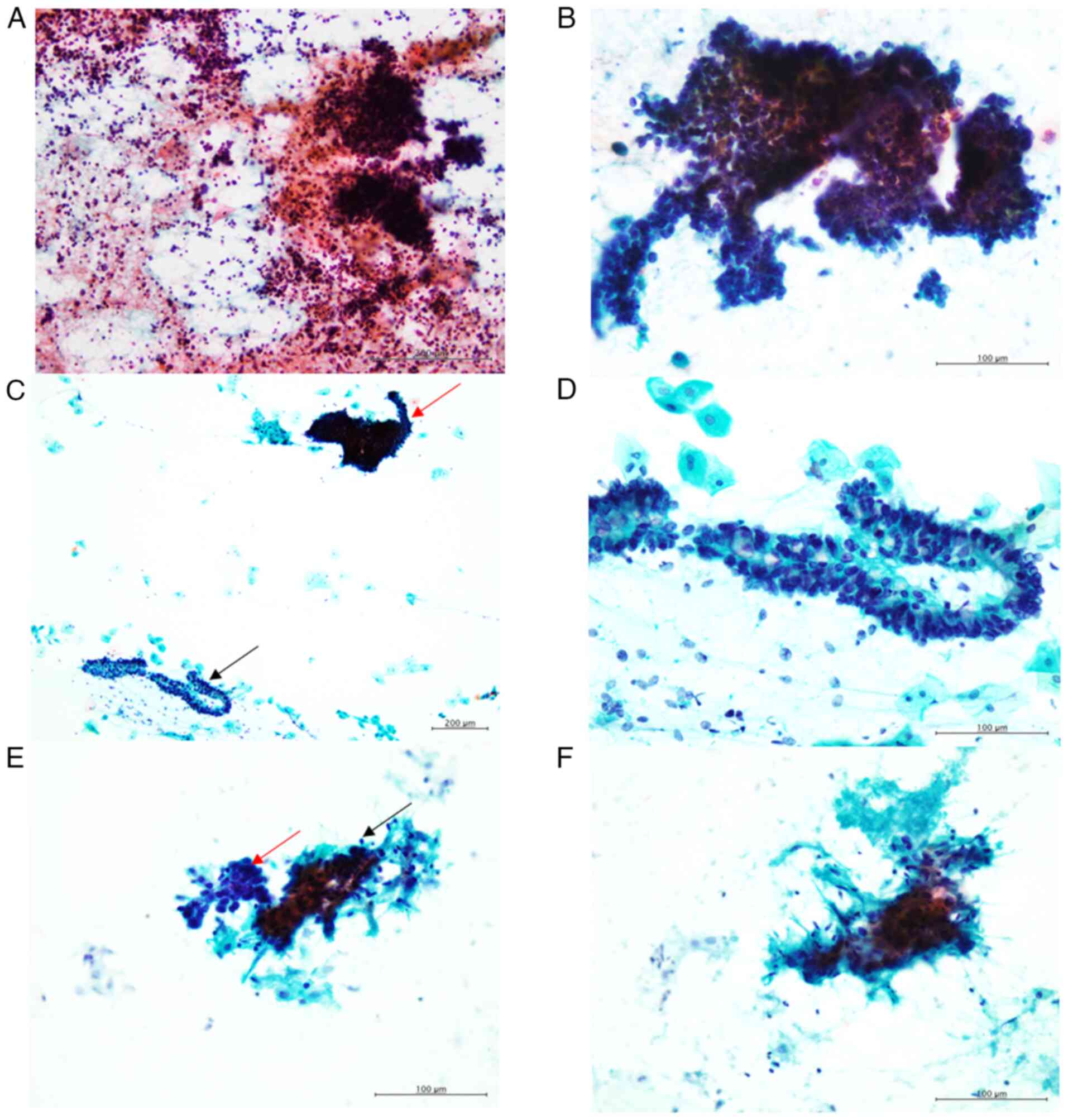

The characteristic cytological features of cervical

SCNEC include the presence of small and/or large clusters of small,

round neoplastic cells with round-to-oval nuclei, exhibiting a

granular chromatin pattern without conspicuous nucleoli in an

inflammatory or necrotic background (Fig. 1A and B). These neoplastic cells also

displayed nuclear moulding (Fig.

1B).

In this study, all cytological specimens contained

SCNEC components. In patients with pure SCNEC, only SCNEC

components were present in the cytological specimens. Among the two

patients with combined SCNEC, adenocarcinoma was identified in the

cytological specimen of one patient, while the other patient's

specimen showed no adenocarcinoma component upon retrospective

evaluation. In Patient 1, an adenocarcinoma component was observed,

characterised by clusters of columnar cells with peripherally

located round-to-oval nuclei and intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 1C and D).

For Patient 6 (carcinosarcoma), besides the SCNEC

component, small clusters of spindle-shaped cells were observed.

These cells had large, oval-to-short spindle nuclei with

hyperchromasia and small nucleoli (Fig.

1E and F), suggesting a sarcomatous component.

The initial cytological diagnosis is presented in

Table I. According to the Bethesda

System for Reporting Cervical Cytology (5), five of the six patients were

categorised as having ‘other malignant neoplasms (SCNEC)’. The

remaining patient (Patient 5) was cytodiagnosed with SCC.

Retrospective review revealed that nuclear moulding was present but

not apparent in the cytological specimens of Patient 5 compared to

the other five patients. The adenocarcinoma component (Patient 1)

and the sarcoma component (Patient 6) were not initially detected

cytologically. However, in Patient 6, the presence of atypical

spindle cells was noted in the cytological report.

Histopathological and

immunohistochemical results

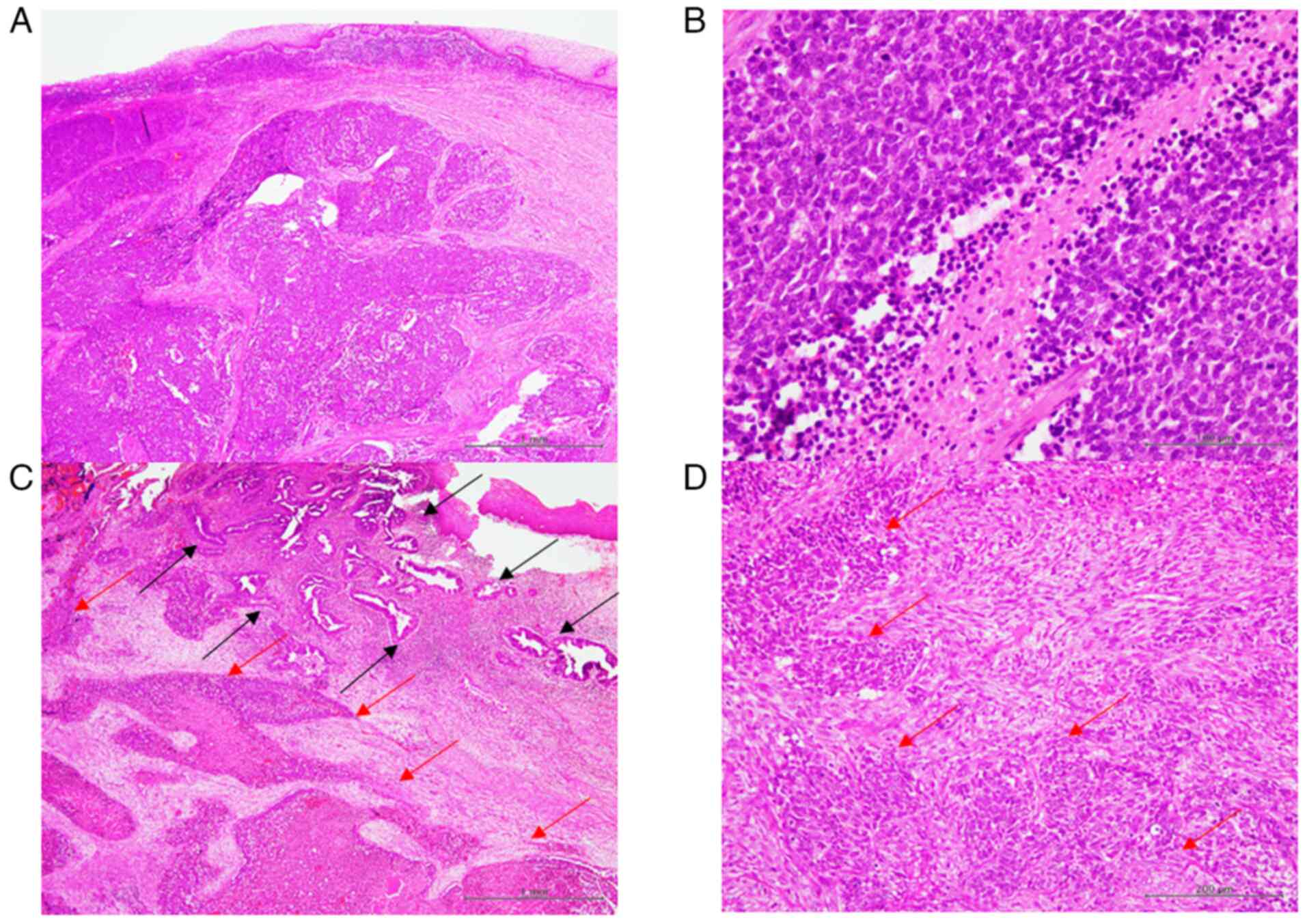

Fig. 2 illustrates

the typical histopathological features of cervical SCNEC. The

proliferation of small, round neoplastic cells with scant cytoplasm

and a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio without conspicuous

nucleoli were characteristic of SCNEC (Fig. 2A). These neoplastic cells exhibited

nuclear moulding, while mitotic figures and necrosis were also

readily observed (Fig. 2B). In

patients with combined SCNEC (Patients 1 and 5), an adenocarcinoma

component was identified. The adenocarcinoma exhibited glandular

formation by neoplastic columnar cells with large, round-to-oval

nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Fig.

2C). In Patient 1, no invasive growth was noted (adenocarcinoma

in situ), whereas infiltrative growth was observed in

Patient 5 (Fig. 2C). Proliferation

of neoplastic spindle-shaped cells around the SCNEC component was

noted in Patient 6 (carcinosarcoma). These spindle-shaped cells had

large, oval-to-short spindle nuclei with nucleoli, which were

considered to the sarcomatous component (Fig. 2D).

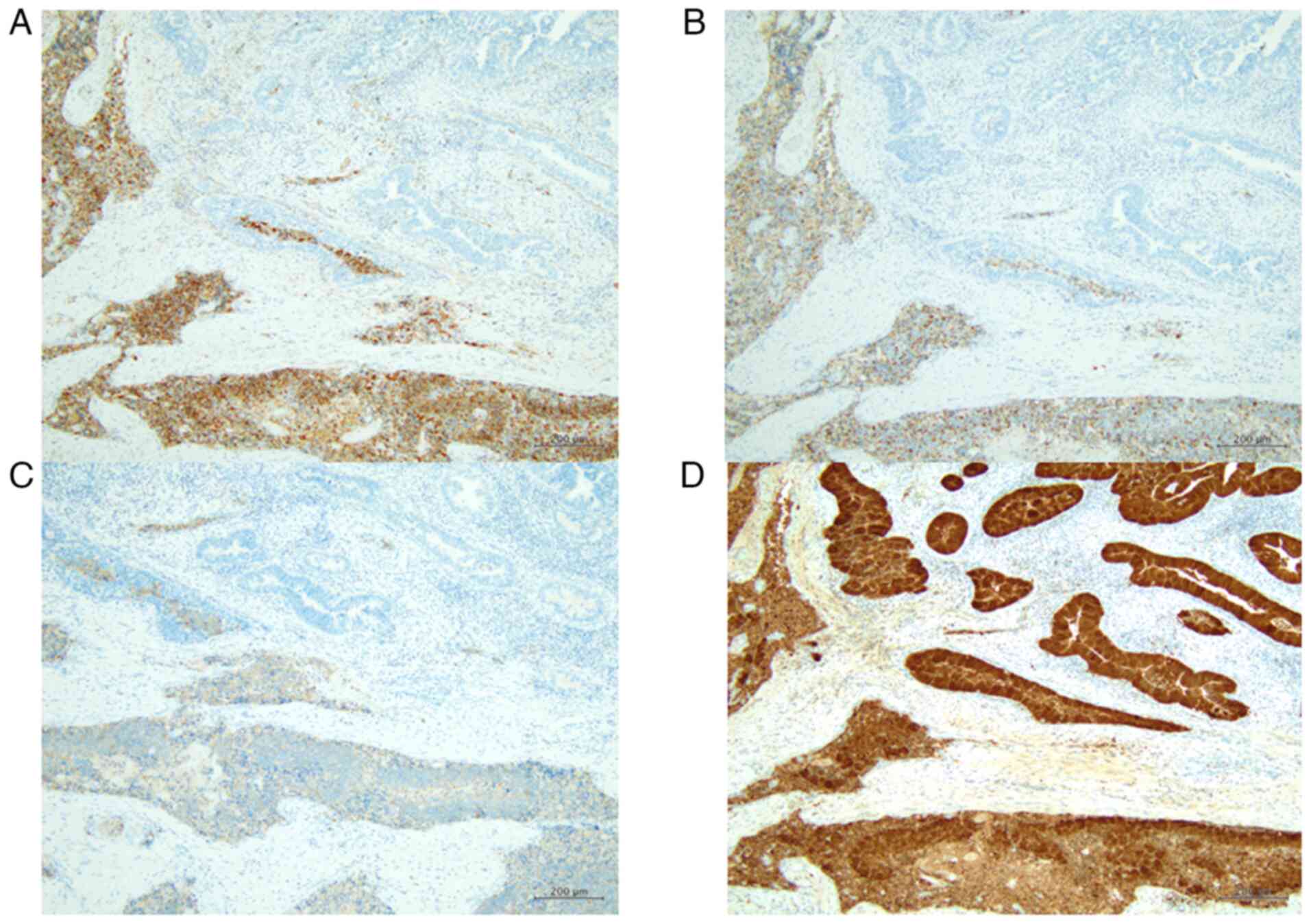

Immunohistochemically, CD56 was diffusely expressed

in the SCNEC of all six patients (Fig.

3A). Chromogranin A and synaptophysin were also expressed in

the SCNEC component of five patients, except Patient 4 (Fig. 3B and C). Additionally, p16 was

diffusely expressed in the SCNEC component of all six patients

(100% of SCNEC cells) (Fig. 3D).

The adenocarcinoma component did not express CD56, chromogranin A,

or synaptophysin; however, p16 was diffusely expressed in the

adenocarcinoma components of Patients 1 and 5 (100% of

adenocarcinoma cells).

Discussion

This study described the cytological features of six

patients with cervical SCNEC. To our knowledge, this is the second

cytological series on cervical SCNEC to include combined SCNEC. The

cytological features of SCNEC are consistent across various organs,

including the lungs, bile duct, uterine cervix, endometrium, and

urinary bladder (6–10). Thus, the cytological diagnosis of

SCNEC using cervical smears should not be particularly challenging.

However, due to the rarity of cervical SCNEC, the rate of accurate

cytodiagnosis remains low (6,7). For

instance, Liu et al (7)

retrospectively analysed cytological cases of cervical SCNEC,

including combined SCNEC. Their study comprised seven pure SCNEC

cases and four combined SCNEC, and none of the patients were

correctly diagnosed with SCNEC based on the initial cytological

examination. Instead, three cases were suspected to have high-grade

SIL, while two were misdiagnosed as atypical glandular cells.

Additionally, only one cytological specimen contained high-grade

SIL, but no adenocarcinoma and SCC components were present by

retrospective review of combined SCNEC (7). Cervical SCNEC is mainly missed or

misdiagnosed as SIL or SCC (6,7,20–22).

In the present series, five of six patients were initially

diagnosed with SCNEC, and the remaining patients were diagnosed

with SCC. Liu et al summarised the causes of misdiagnosis of

SCNEC by the cervical cytological examination as follows: i) the

rarity of this type of carcinoma, ii) SCNEC can be overlooked in

the presence of squamous and/or glandular lesions, iii) SCNEC can

be mimicked by the other neoplasms, such as SIL and SCC

(cytological differential diagnostic considerations are discussed

later), iv) SCNEC is not present in the cytological specimens

because this carcinoma component can be present in the submucosal

region or necrosis and/or heavy inflammatory may result in

insufficient sampling (7).

Interestingly, the present series included two patients with

combined SCNEC and one patient with carcinosarcoma. Retrospective

cytological analysis revealed that the adenocarcinoma component was

present in the cytological specimen of one of the two patients with

combined SCNEC, and both the sarcomatous component and SCNEC were

present in the cytological specimen of the carcinosarcoma. Previous

reports have suggested that SCNEC, as well as combined

adenocarcinoma and/or SIL components, can be detected in cervical

cytological specimens (16,17). According to these results, careful

observation of cervical cytological specimens may lead to the

correct diagnosis of SCNEC as well as combined tumour lesions.

Carcinosarcomas are rare biphasic malignant tumours

composed of carcinomatous and sarcomatous components. Although

rare, SCNEC can serve as the carcinomatous component in cervical

carcinoma (23), as seen in our

study (Patient 6). The sarcomatous component is often homologous

(e.g., fibrosarcoma, endometrioid stromal sarcoma) but can also

exhibit heterologous differentiation (e.g., osteosarcoma and

rhabdomyosarcoma) (23). The

accuracy of initial cytological diagnosis for cervical

carcinosarcoma is generally low. A previous study reported that

only two of 23 cases (21 endometrial and two cervical

carcinosarcomas) were correctly identified as carcinosarcoma

through cytological examination, while 14 cases were misdiagnosed

as carcinoma (24). The detection

of sarcomatous components in endometrial and cervical cytological

specimens is notably more challenging (24,25).

In Patient 6 (carcinosarcoma), the SCNEC component was identified

by initial cytological examination. However, retrospective

cytological analysis was able to detect both SCNEC and sarcomatous

components. These findings emphasise the importance of meticulous

cytological evaluation for achieving an accurate diagnosis.

It is well-recognised that HPV is associated with

the development of a large proportion of cervical neoplasms,

including SIL, SCC, and adenocarcinoma (5). Infection with HPV, particularly HPV18,

a common high-risk strain, is correlated with cervical SCNEC

(1,7). Consequently, cervical SCNEC may

contain SIL, SCC, and/or adenocarcinoma components, although their

precise incidence remains unknown. Immunohistochemical staining for

p16 is widely used as a surrogate marker for detecting high-risk

HPV, and most cervical SCNECs exhibit positive immunoreactivity for

this marker (1,7). Additionally, it has been reported that

combined SIL, SCC, and adenocarcinoma components exhibit positive

immunoreactivity for p16 (11,16,17).

In the present study, all SCNEC showed positive immunoreactivity

for p16. Although HPV testing results were not available for all

patients in the present cohort, all likely had a high-risk HPV

infection, particularly HPV18 (1,7).

The primary differential cytological diagnoses for

cervical SCNEC are SIL and SCC. A small proportion of patients with

cervical SCNEC are misdiagnosed with SIL and SCC (6,7,20–22),

and one of the six patients in the present cohort was initially

diagnosed with SCC. Key distinguishing features of SCNEC include

finely granular (salt-and-pepper) chromatin, inconspicuous

nucleoli, and nuclear moulding (6,7,20–22).

In contrast, SIL and SCC typically exhibit richer and denser

cytoplasm, clearer cell boundaries, and a lack of definitive

nuclear moulding (6,7,20–22).

These cytological features may help in differential diagnosis. In

one patient initially diagnosed with SCC in the present study,

nuclear moulding was not apparent; therefore, SCC was initially

considered. Positive immunocytochemical staining for CD56 may aid

in the cytodiagnosis of SCNEC (20); however, immunocytochemical staining

for neuroendocrine markers was not performed in the present

study.

The present study had some limitations. First, this

study included relatively few patients with SCNEC, although this

type of carcinoma is relatively rare. Second, HPV testing results

were not available for all patients in the present cohort. Further

studies are needed to clarify the clinicocytological and molecular

features of cervical SCNEC.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

demonstrated that most SCNEC could be detected in cervical

cytological specimens. Moreover, other combined carcinoma

components, as well as sarcomatous components, could be identified

in cervical cytological specimens. Thus, cervical cytological

examination may be helpful in SCNEC diagnosis. The detection of

SCNEC in cervical cytological specimens is crucial for accurate and

early diagnosis and timely treatment of this aggressive

carcinoma.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MO and MI conceived the study. MO, MI, HO, MT, KA,

IK, MU, CD, NK, SO, RT, YT, TT, and YH analysed the cytological

and/or clinicopathological data, and MO and MI prepared the

figures. MO and MI wrote the original draft and edited the

manuscript. MO and MI confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the

tenets of The Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was

approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka Medical and

Pharmaceutical University (approval no. 2023-073; Takatsuki, Osaka,

Japan). All data were anonymised. Informed consent was obtained

from the patients using an opt-out methodology because of the

retrospective study design, with no risk of patient identity

exposure. In addition, this study did not include children.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HPV

|

human papillomavirus

|

|

SCC

|

squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

SCNEC

|

small cell neuroendocrine

carcinoma

|

|

SIL

|

squamous intraepithelial lesion

|

References

|

1

|

Alvarado-Cabrero I, Euscher ED, Ganesan R

and Howitt BE: Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. WHO

Classification of Tumours. Female Genital Tumours. 5th Edition.

Volume 4. IARC Publications; Lyon, France: pp. 455–456. 2020

|

|

2

|

Rouzbahman M and Clarke B: Neuroendocrine

tumors of the gynecologic tract: Select topics. Semin Diagn Pathol.

30:224–233. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tempfer CB, Tischoff I, Dogan A, Hilal Z,

Schultheis B, Kern P and Rezniczek GA: Neuroendocrine carcinoma of

the cervix: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Cancer.

18:5302018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chu T, Meng Y, Wu P, Li Z, Wen H, Ren F,

Zou D, Lu H, Wu L, Zhou S, et al: The prognosis of patients with

small cell carcinoma of the cervix: A retrospective study of the

SEER database and a Chinese multicentre registry. Lancet Oncol.

24:701–708. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nayar R and Wilbur DC: The Bethesda system

for reporting cervical cytology. 3rd Edition. Springer;

Switzerland: 2015, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhou C, Hayes MM, Clement PB and Thomson

TA: Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: Cytologic findings

in 13 cases. Cancer. 84:281–288. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu Y, Li M, Liu Y, Wan Y, Yang B, Li D

and Wang S: Liquid-based cytology of small cell carcinoma of the

cervix: A multicenter retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther.

17:557–565. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ebisu Y, Ishida M, Okano K, Sandoh K,

Mizokami T, Kita M, Okada H and Tsuta K: Small-cell neuroendocrine

carcinoma in directly sampled endometrial cytology: A monocentric

retrospective study of six cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 47:1297–1301.

2019. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ishida M, Okano K, Sandoh K, Ito H, Ikeura

T, Mitsuyama T, Miyoshi H, Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Okazaki K and

Tsuta K: Neuroendocrine carcinoma diagnosis from bile duct

cytological specimens: A retrospective single-center study. Diagn

Cytopathol. 48:154–158. 2020. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yoshida K, Ishida M, Kagotani A, Iwamoto

N, Iwai M and Okabe H: Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder

and prostate: Cytological analyses of four cases with emphasis on

the usefulness of cytological examination. Oncol Lett. 7:369–372.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Alvarado-Cabrero I, Euscher ED, Ganesan R

and Howitt BE: Carcinoma admixed with neuroendocrine carcinoma. WHO

Classification of Tumours, Female Genital Tumours. 5th Edition.

Volume 4. IARC Press; Lyon, France: pp. 4592020

|

|

12

|

Masuda M, Iida K, Iwabuchi S, Tanaka M,

Kubota S, Uematsu H, Onuma K, Kukita Y, Kato K, Kamiura S, et al:

Clonal origin and lineage ambiguity in mixed neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Am J Pathol. 194:415–429. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pei X, Xiang L, Chen W, Jiang W, Yin L,

Shen X, Zhou X and Yang H: The next generation sequencing of

cancer-related genes in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the

cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 161:779–786. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li S and Zhu H: Twelve cases of

neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix: Cytology,

histopathology and discussion of their histogenesis. Acta Cytol.

57:54–60. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Giordano G, D'Adda T, Pizzi S, Campanini

N, Gambino G and Berretta R: Neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of

the cervix: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 14:922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Okabe A, Ishida M, Noda Y, Okano K, Sandoh

K, Fukuda H, Kita M, Okada H and Tsuta K: Small-cell neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the cervix accompanied by adenocarcinoma and

high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Diagn Cytopathol.

50:E285–E288. 2022. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nishiumi Y, Nishimura T, Kashu I, Aoki T,

Itoh R, Tsuta K and Ishida M: Adenocarcinoma in situ admixed with

small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: A case report

with cytological features. Diagn Cytopathol. 46:752–755. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shimojo N, Hirokawa YS, Kanayama K, Yoneda

M, Hashizume R, Hayashi A, Uchida K, Imai H, Kozuka Y and Shiraishi

T: Cytological features of adenocarcinoma admixed with small cell

neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cytojournal.

14:122017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Alphandery C, Dagrada G, Frattini M,

Perrone F and Pilotti S: Neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the

cervix associated with endocervical adenocarcinoma: A case report.

Acta Cytol. 51:589–593. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gupta P, Gupta N, Suri V, Rai B and

Rajwanshi A: Cytomorphological features of cervical small cell

neuroendocrine carcinoma in SurePath™ liquid-based cervical

samples. Cytopathology. 32:813–818. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kim MJ, Kim NR, Cho HY, Lee SP and Ha SY:

Differential diagnostic features of small cell carcinoma in the

uterine cervix. Diagn Cytopathol. 36:618–623. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim Y, Ha HJ, Kim JS, Chung JH, Koh JS,

Park S and Lee SS: Significance of cytologic smears in the

diagnosis of small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Acta

Cytol. 46:637–644. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yemelyanova A, Kong CS and Srinivasan R:

Carcinosarcoma. WHO Classification of Tumours. Female Genital

Tumours. 5th Edition. Volume 4; IARC Press; Lyon, France: pp.

3822020

|

|

24

|

Costa MJ, Tidd C and Willis D:

Cervicovaginal cytology in carcinosarcoma [malignant mixed

Mullerian (mesodermal) tumor] of the uterus. Diagn Cytopathol.

8:33–40. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Okano K, Ishida M, Sandoh K, Mizokami T,

Kita M, Okada H and Tsuta K: Cytological features of uterine

carcinosarcoma: A retrospective study of 20 cases with an emphasis

on the usefulness of endometrial cytology. Diagn Cytopathol.

47:547–552. 2019. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|